#milton moore

Text

Matt Smith as Robert Mapplethorpe & McKinley Belcher III as Milton Moore

MAPPLETHORPE: THE DIRECTOR'S CUT (2020) dir. Ondi Timoner

#matt smith#mapplethorpe#perioddramaedit#filmedit#photography#mckinley belcher iii#robert mapplethorpe#11th doctor#doctor who#lgbt#queer#couple#affection#intimacy#desire#queer media#ondi timoner#cinema#movies#indie cinema#period drama#milton moore#beautiful men

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 1

#polls#spn#supernatural#ruby spn#jessica moore#billie the reaper#alex jones#kaia nieves#patience turner#emma winchester#anna milton#abaddon spn#eileen leahy#amara spn

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hunter in The Rye or how Dean slowly amassed his army of sisters (and other assorted siblings)

#grymmid!dean#creature!dean#creature dean#THiTR#dean winchester#anna milton#jo harvelle#bela talbot#Zephyr Arcadia#jessica moore#how many characters can I make Dean's family#you'd be surprised#Sam is jealous#wdym he has to share his brother#gasp#Balthazar is vaguely fond of him#Gabriel is terrified

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

💔

i’m sure by now you’ve all heard the news…

and here are some cast goodbyes:

Zane full tweet (cont.): “for making me feel both welcome & celebrated. I’m grateful we got the story that we did. This will always represent something really meaningful to me❤️special shout-out to ben levin for being My Number One - would have done many more seasons with ya, gladly”

Elijah’s full tweet (cont.): “to playing a kid who didn’t believe in himself in front of millions. To be a plus sized actor on a network TV show where ABSOLUTELY 0 jokes were made about his weight will forever be a highlight of my career. There are too, too many people to tag in this that have made an impact on me, but I just want to say that my time on this show, however brief it may have felt to some, will stick with me forever. I will miss getting to play make-believe with my friends everyday, but I will never forget our time together. Thank you to everyone that made this journey possible, I love you all, and I hope to see you again soon.”

#legacies#cw#cw legacies#the originals#the vampire diaries#hope mikaelson#alaric saltzman#zane phillips#elijah moore#danielle rose russell#quincy fouse#milton greasley#omono okojie#ben levin#legacies cancelled#lizzie saltzman#josie saltzman#jenny boyd#cleo sowande

53 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 1/1

Fandom: Supernatural (TV 2005)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply

Relationships: Ellen Harvelle/John Winchester/Mary Winchester, Castiel/Jessica Moore/Sam Winchester, Gabriel/Jo Harvelle/Anna Milton/Dean Winchester, Henry Winchester & John Winchester

Additional Tags: Henry Winchester Time Travels, Family Dynamics, Hello Bunker, Abaddon Is A Pushover When You've Got an Archangel On Your Side

Series: Part 18 of Multiamory March, Part 30 of Shifting Family

Summary:

John gets to meet Henry, but there's not really time to unpack all the baggage that comes along with the meeting, because part of that baggage is a Knight of Hell.

#ot3: castiel x jessica moore x sam winchester#ot3: ellen harvelle x john winchester x mary winchester#ot4: anna milton x dean winchester x gabriel x jo harvelle#fandom: supernatural#fanwork: fanfic#MultiamoryMarch#MultiamoryMarch2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

Victoria Regina: Winter (1.4, Granada, 1964)

"What is one to do? There are so many of them - far too many, as you say - and social conditions make it so difficult, you can't get rid of ignorance in a day, Mrs. Clayton!"

"No, nor in a lifetime if one does nothing. Indifference, prejudice, class distinction; all help."

"Help?"

"Have helped, most certainly, to make Windsor what no self-respecting place ought to be."

"Would you wish to get rid of class distinction, Mrs. Clayton?"

"I would wish to get rid of anything, ma'am, which prevents people from recognising their responsibilities."

#victoria regina#classic tv#granada#winter#1964#laurence housman#peter wildeblood#stuart latham#patricia routledge#max adrian#jameson clark#dorothy reynolds#lloyd pearson#kevin brennan#rosamond burne#ernest milton#ian wilson#george curzon#charles cullum#john h. moore#christopher steele#having been in some ways sidelined by the plot of Albert's death in Autumn‚ Victoria is once again centre stage for Winter. dealing with#her final decades as queen‚ the play opens on VR receiving old friend Disraeli (a welcome return for Max Adrian‚ here playing Disraeli as#an old and tired man compared to the twinkling politician of Autumn) before quickly taking in meetings with a reformer of public life and#then a group of bishops. the effect is to present a queen who is as strong of spirit and mettle as she ever was‚ but who is gradually#living out of time and touch with her country; Mrs Clayton is something of a grotesque and the scene clearly has a comic element‚ but she's#also right when she talks about improving conditions for the poor and updating infrastructure. even the bishops are able to appreciate#changing times and evolving views. but Victoria is so steeped in tradition that she risks belonging to an age entirely separate from her#people. Housman was a gay‚ feminist reformer so it's fairly obvious where his sympathies lie‚ but he also lived through the period this ep#covers: his portrait of the queen is not without affection‚ and the series ends on a note of public celebration with the diamond jubilee

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

TBR Pile: April Reads -

Some highlights of what I'll be reading this month!

#bookworm#literature#book reviews#read read read#books#poetry#tbr pile#tbr list#poetry month#john milton#daniel clowes#william gibson#john ashbery#javier marias#mark greif#alan moore

0 notes

Text

27 marzo … ricordiamo …

27 marzo … ricordiamo …

#semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2023: Gianni Minà, giornalista, scrittore e conduttore televisivo italiano. Annoverato tra i più importanti giornalisti italiani, collaborò con quotidiani e settimanali italiani e stranieri, realizzò centinaia di reportage per la Rai, ideò e condusse programmi televisivi, girò film documentari. Iniziò la carriera giornalistica in ambito sportivo nel 1959 a Tuttosport. Nel 1983 recitò il ruolo di…

View On WordPress

#27 marzo#Aldo Da Re#Aldo Ray#Annunziata Chiarelli#Billie Wilder#Billy Wilder#Caterino Bertaglia#Colette Suzanne Jeannine Dacheville#Diana Hyland#Diane Gentner#Dudley Moore#Dudley Stuart John Moore#Farley Earl Granger#Farley Granger#Fiorenzo Fiorentini#George Larkin#Germinal Casado#Gianni Minà#Giuseppe Salvatori#Grant Whiters#Granville G. Withers#Lars Bloch#Maurizio Gucci#May Allison#Mendel Berlinger#Milton Berle#Renato Salvatori#Riccardo Battaglia#Rick Austin#Rick Battaglia

0 notes

Text

Matt Smith as Robert Mapplethorpe & McKinley Belcher III as Milton Moore

MAPPLETHORPE: THE DIRECTOR'S CUT (2020) dir. Ondi Timoner

#matt smith#mapplethorpe#perioddramaedit#filmedit#photography#mckinley belcher iii#robert mapplethorpe#11th doctor#doctor who#lgbt#queer#couple#affection#intimacy#desire#queer media#ondi timoner#cinema#movies#indie cinema#period drama#milton moore#beautiful men

622 notes

·

View notes

Text

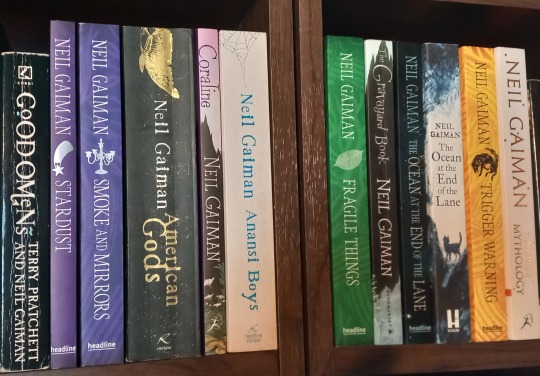

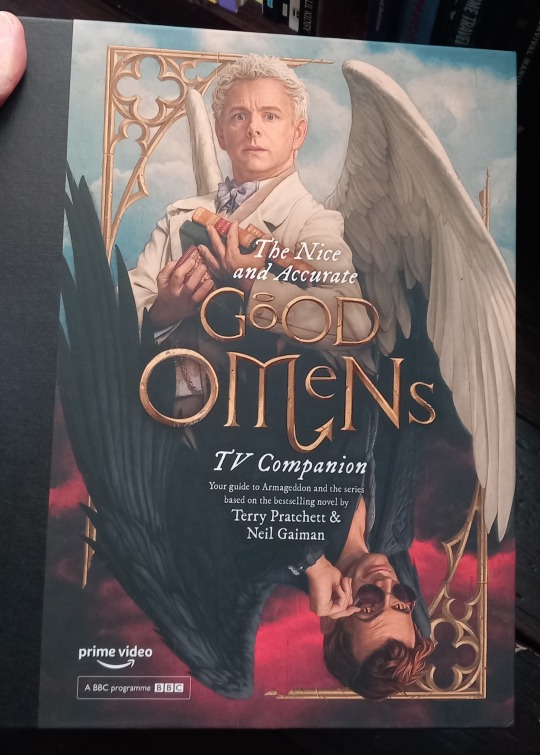

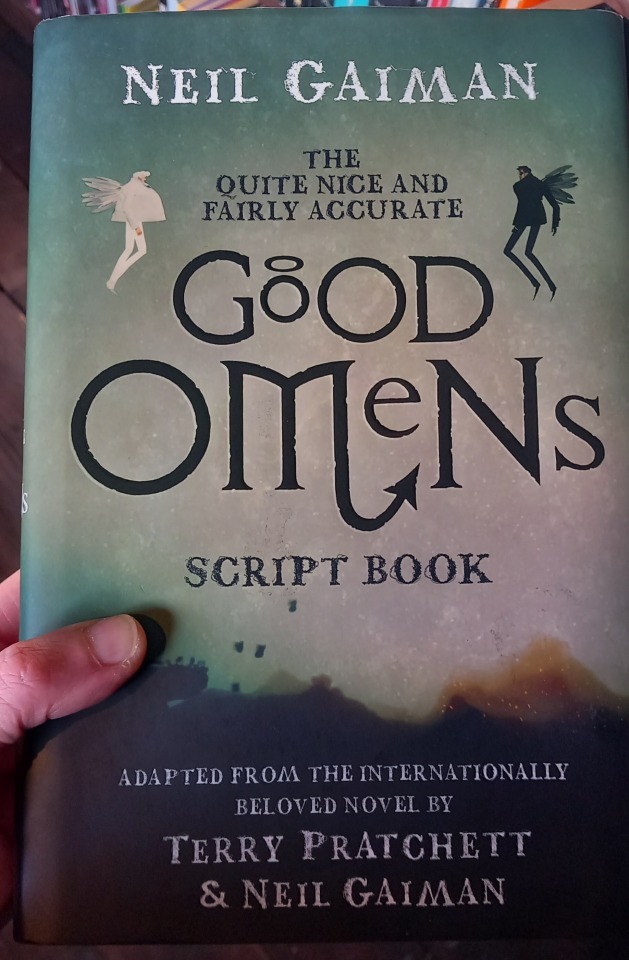

Library tour - Pratchett and Gaiman focused with some honourable mentions

Of course I've constantly had full bookshelves since I was a child, but I'd always wanted a room I could properly call a library. The house my husband and I now live in has 3 bedrooms, so as we're child free we've each taken one of the spare rooms to do with as we wish.

The majority of the furniture you see is thrifted (aside from the bookcases) and it was self decorated with a lot of cut corners-for example I decided instead of proper flooring it would be cheaper just to pull up the carpet and varnish the actual boards.

I spend more time in here than I do in our living room 😁

Gaiman stuff. Sandman alongside some Alan Moore, Preacher, Hellblazer, my signed copy of The Crow and one volume of Sin City. Two copies each of Ocean (one illustrated), and American Gods (original and authors preferred text). And of course one of my copies of Good Omens. Plus you can see the novelisation of Pan's Labyrinth sitting next to Neverwhere. Del Toro is another favourite fantasist of mine.

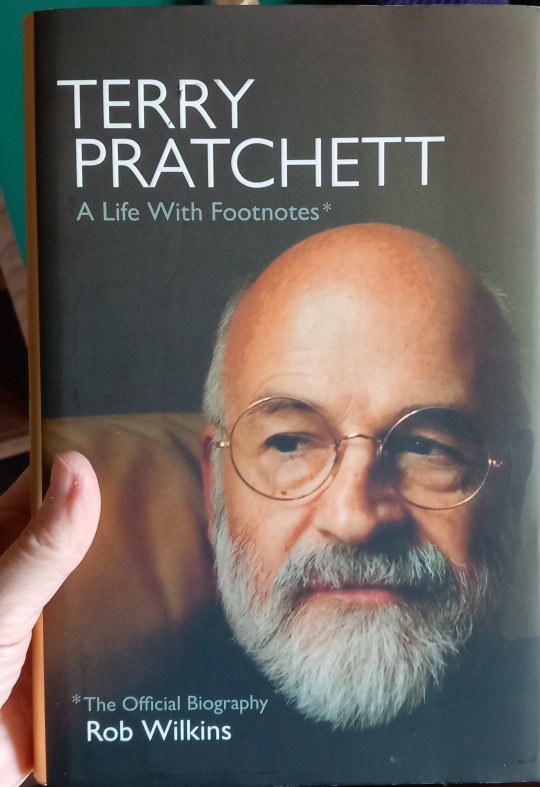

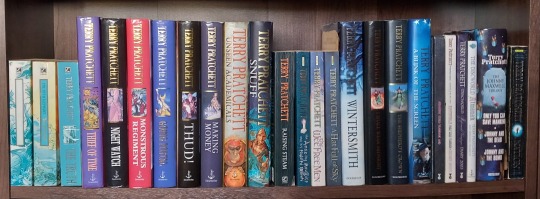

Pratchett stuff. Complete Discworld of course, and I'm slowly increasing my non Discworld Pratchett collection, my second copy of GO, the Paul Kidby illustrated edition (makes sense to have one living with the Gaiman books and the other with Pratchett). Soul Music and Hogfather are both signed, I met Pterry when I was 14 on the Hogfather signing tour.

The crocheted toy was actually from a pattern for a mimic I made (pattern by Complicated Knots on YouTube), but it's luggage-y enough that I put it with the Discworld books, Rob Wilkins' biography of Pterry, and a Librarian to look after everything, make sure the books don't get rowdy and take care of the L-space. I've had him since I was 18.

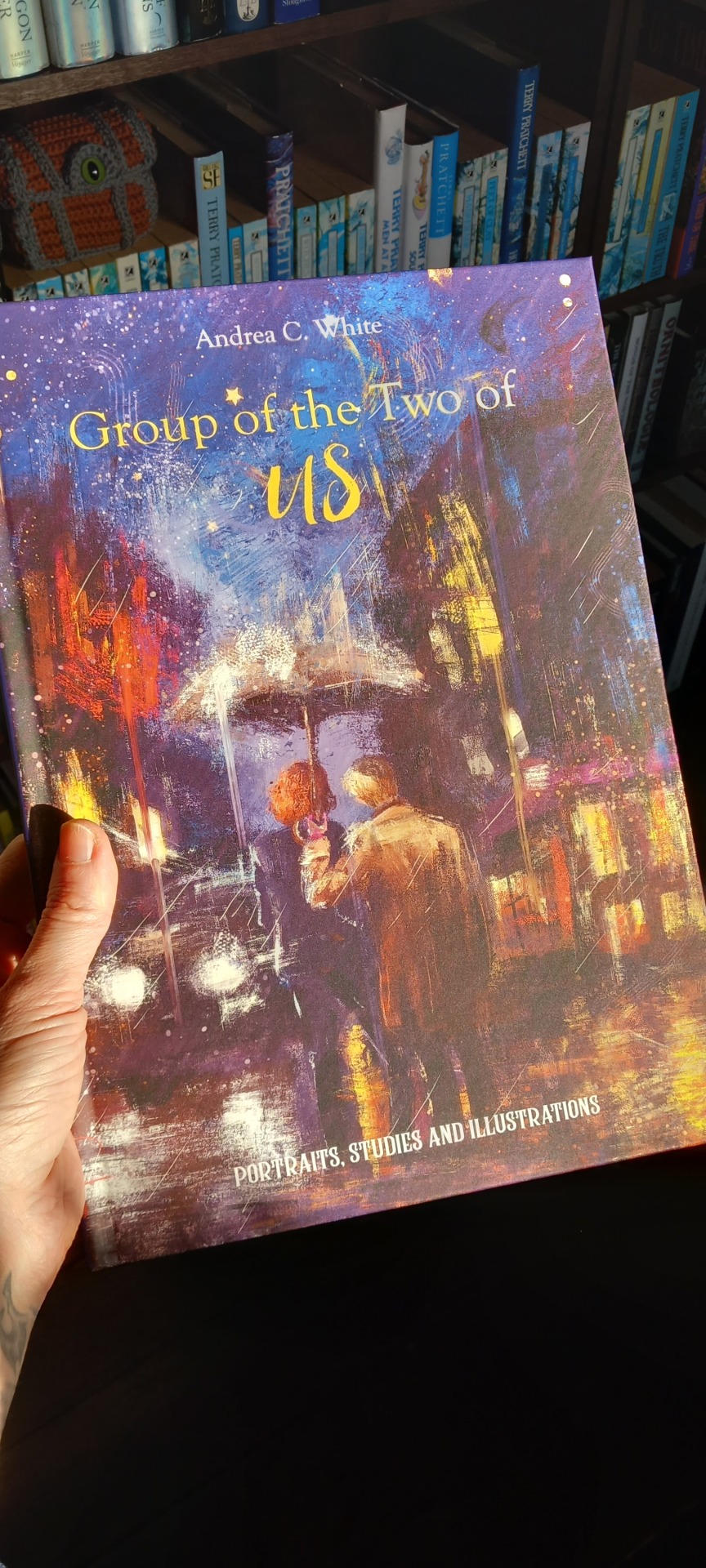

Specifically Good Omens stuff: a pair of felt plushies a friend made for me after S1 was released (@diedarlingsuk on Instagram), a pair of drawings I bought from a very talented 15 year old artist at a tiny comic con also after S1, (I'd credit her but I've no idea of her name or if she has an online presence), the script book, the TV companion, and an art book by the wonderful @mistysblueboxstuff, who I'm sure most of the fandom know and love. This contains all her GO art from S1 and S2.

Honourable mention stuff - I put above that I love Del Toro, so I've got to share the Angel of Death from Hellboy 2 as its one of my favourite things in this room. And its an angel, so that's kinda linked.

Made for me by another friend from clay on a doll's body and the wings on wire frames (@sids_workshop on Instagram).

Finally the Complete William Blake illuminated works, a guidebook to a Blake exhibition I went to, and Gustav Dore illustrated copies of Dante, Milton, Coleridge, Tennyson and Poe. I am a huge poetry nerd, and I think many GO fans would find a lot to interest them in some of these, particularly Blake and Milton.

I could go on, there's tons of other stuff I'd like to include but this post is fairly massive already and I wanted to try and stick to my theme.

#neil gaiman#terry pratchett#gnu terry pratchett#good omens#go2#good omens 2#crowley#aziraphale#ineffable husbands#guillermo del toro#books and reading#home library#books & libraries#the luggage#discworld#The Librarian#book omens#good omens book#the sandman

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

britcom comedians & panel show personalities who share your sign

AQUARIUS ♒ dara ó briain • frank skinner • glenn moore • guz khan • hugh dennis • lucy porter • maisie adam • mark watson • phil wang • vic reeves

PISCES ♓ aisling bea • alan davies • dave gorman • ed gamble • jenny eclair • katy wix • michael mcintyre • rose matafeo

ARIES ♈ andy parsons • desiree burch • ed byrne • gary delaney • jamali maddix • john kearns • josh widdicombe • josie long • roisin conaty • romesh ranganathan • rory bremner

TAURUS ♉ al murray • alex brooker • catherine tate • greg davies • joe wilkinson • john robins • mae martin • milton jones • morgana robinson • rhys james • rob brydon • sally phillips • sandi toksvig • sean lock • stephen mangan

GEMINI ♊ alan carr • bob mortimer • david baddiel • fern brady • judi love • julian clary • london hughes • mel giedroyc • noel fielding • paul sinha • rich hall • richard ayoade • sara pascoe • sarah millican • shappi khorsandi • sindhu vee • tom allen

CANCER ♋ adam hills • alice levine • david mitchell • katherine ryan • harriet kemsley • ian hislop • jack whitehall • joe lycett • paul merton • peter serafinowicz • phill jupitus • rosie jones

LEO ♌ bridget christie • cariad lloyd • chris ramsey • daisy may cooper • frankie boyle • isy suttie • lee mack • jo brand • nish kumar • victoria coren mitchell

VIRGO ♍ alex horne • dane baptiste • darren harriott • ivo graham • jimmy carr • johnny vegas • lolly adefope • miles jupp • nina conti • stephen fry • sue perkins • tim key

LIBRA ♎ diane morgan • harry hill • jack dee • jon richardson • limmy • nick helm • rhod gilbert • robert webb • tiff stevenson • zoe lyons

SCORPIO ♏ angela barnes • chris addison • elis james • ellie taylor • holly walsh • liza tarbuck • jonathan ross • kerry godliman • kevin bridges • matt forde • mike wozniak • sofie hagen • susan calman

SAGITTARIUS ♐ adam riches • david o'doherty • jessica knappett • larry dean • miranda hart • richard osman • seann walsh • simon amstell • steven k. amos

CAPRICORN ♑ ahir shah • angus deayton • bill bailey • claudia winkleman • james acaster • mark lamarr • paul foot • rob beckett • suzi ruffell

#REPOSTING CUZ I ACCIDENTALLY DELETED IT HAHA#sorry i can't include every person ever but i tried to at least do everyone's faves!#a good day to be a gemini!!!#signs

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

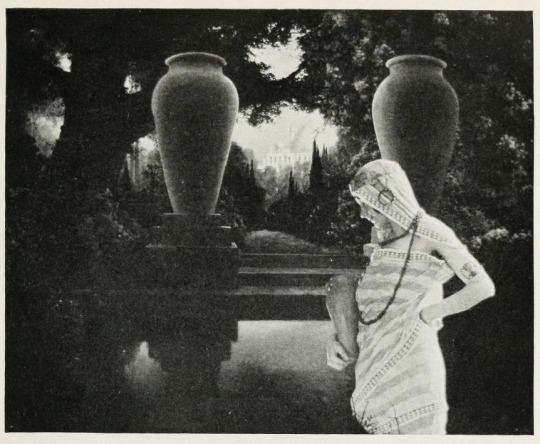

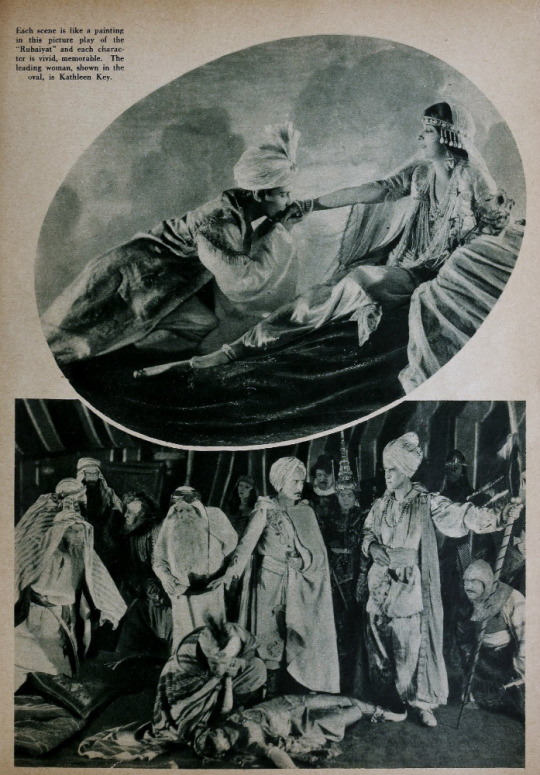

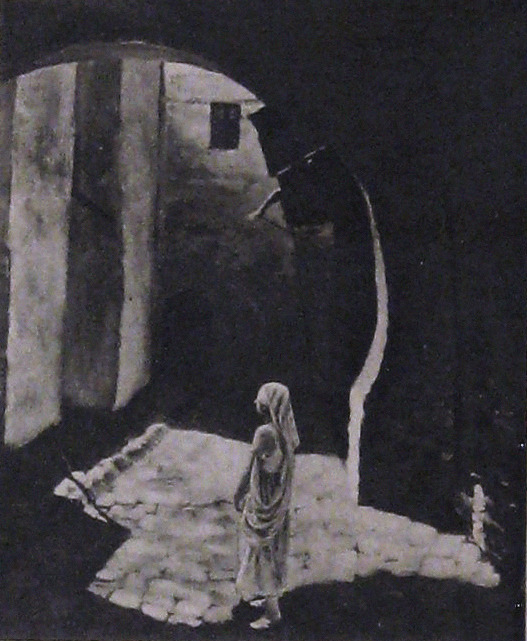

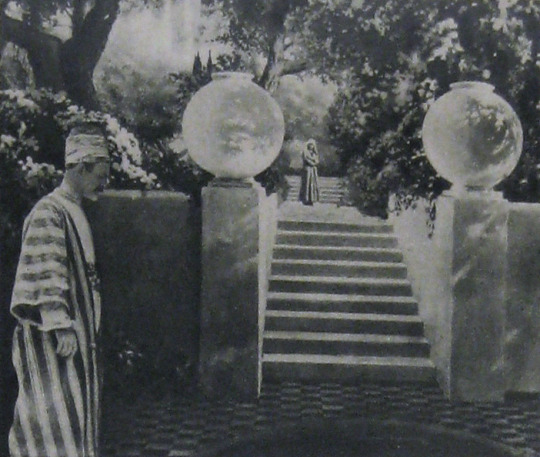

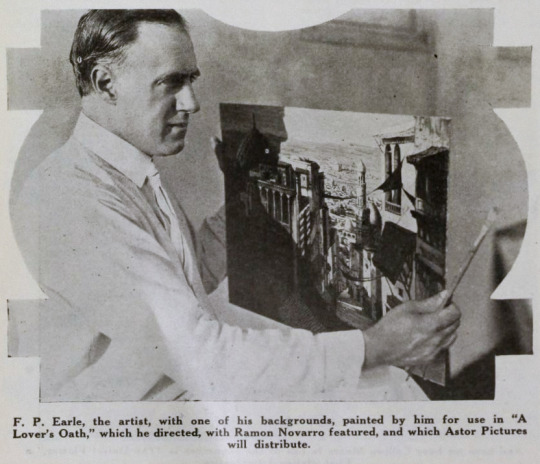

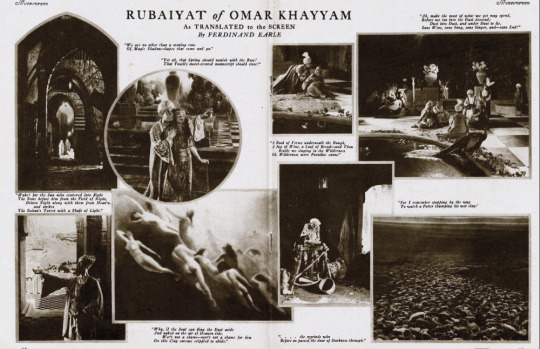

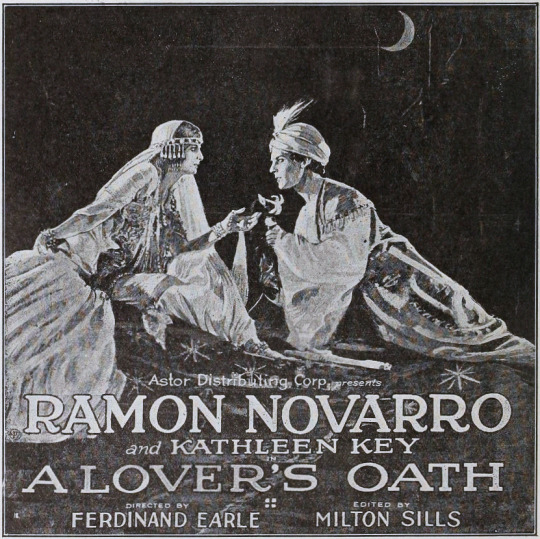

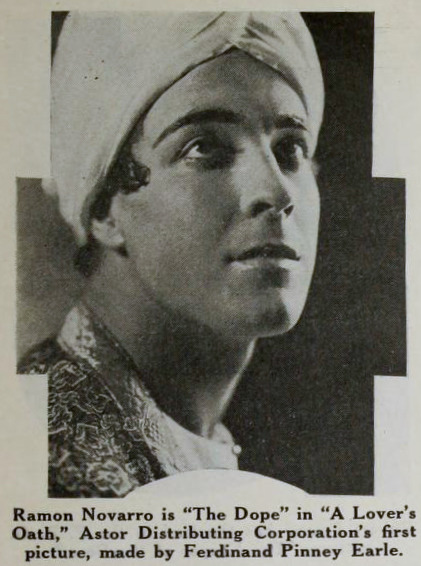

(Mostly) Lost, but Not Forgotten: Omar Khayyam (1923) / A Lover’s Oath (1925)

Alternate Titles: The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, The Rubaiyat, Omar Khayyam, Omar

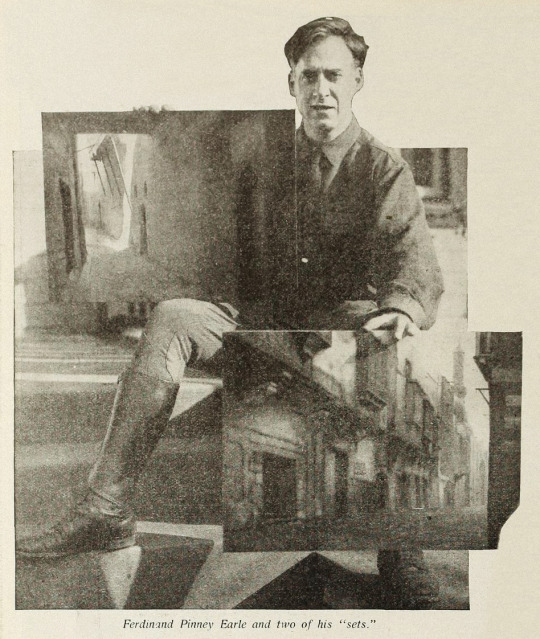

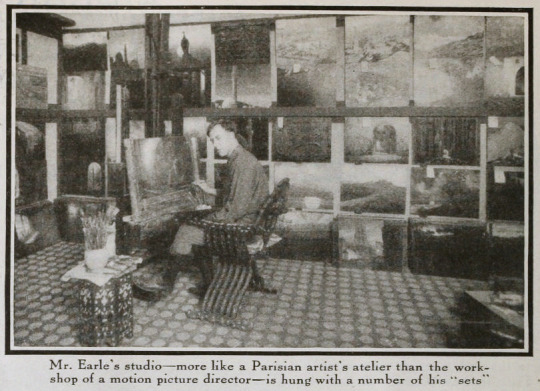

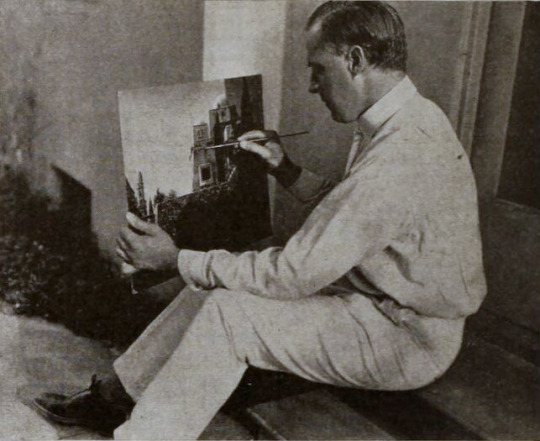

Direction: Ferdinand Pinney Earle; assisted by Walter Mayo

Scenario: Ferdinand P. Earle

Titles: Marion Ainslee, Ferdinand P. Earle (Omar), Louis Weadock (A Lover’s Oath)

Inspired by: The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, as edited & translated by Edward FitzGerald

Production Manager: Winthrop Kelly

Camera: Georges Benoit

Still Photography: Edward S. Curtis

Special Photographic Effects: Ferdinand P. Earle, Gordon Bishop Pollock

Composer: Charles Wakefield Cadman

Editors: Arthur D. Ripley (The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam version), Ethel Davey & Ferdinand P. Earle (Omar / Omar Khayyam, the Director’s cut of 1922), Milton Sills (A Lover’s Oath)

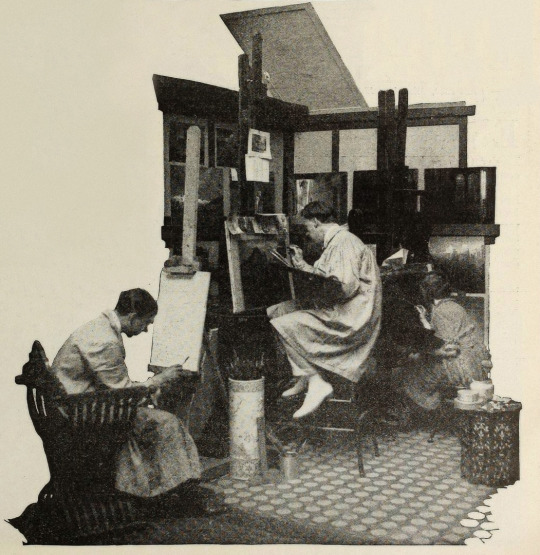

Scenic Artists: Frank E. Berier, Xavier Muchado, Anthony Vecchio, Paul Detlefsen, Flora Smith, Jean Little Cyr, Robert Sterner, Ralph Willis

Character Designer: Louis Hels

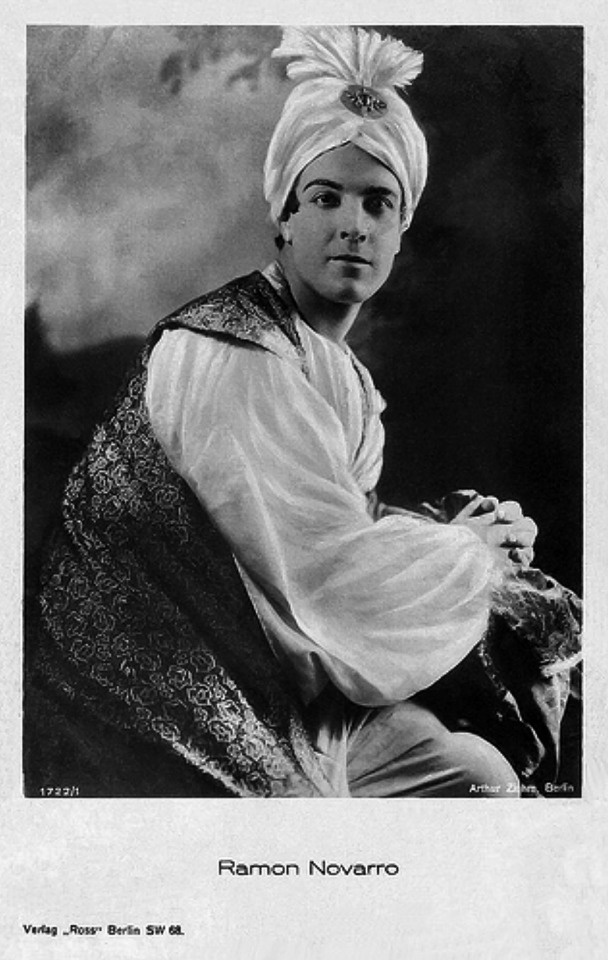

Choreography: Ramon Novarro (credited as Ramon Samaniegos)

Technical Advisors: Prince Raphael Emmanuel, Reverend Allan Moore, Captain Dudley S. Corlette, & Captain Montlock or Mortlock

Studio: Ferdinand P. Earle Productions / The Rubaiyat, Inc. (Production) & Eastern Film Corporation (Distribution, Omar), Astor Distribution Corporation [States Rights market] (Distribution, A Lover’s Oath)

Performers: Frederick Warde, Edwin Stevens, Hedwiga Reicher, Mariska Aldrich, Paul Weigel, Robert Anderson, Arthur Carewe, Jesse Weldon, Snitz Edwards, Warren Rogers, Ramon Novarro (originally credited as Ramon Samaniegos), Big Jim Marcus, Kathleen Key, Charles A. Post, Phillippe de Lacy, Ferdinand Pinney Earle

Premiere(s): Omar cut: April 1922 The Ambassador Theatre, New York, NY (Preview Screening), 12 October 1923, Loew’s New York, New York, NY (Preview Screening), 2 February 1923, Hoyt’s Theatre, Sydney, Australia (Initial Release)

Status: Presumed lost, save for one 30 second fragment preserved by the Academy Film Archive, and a 2.5 minute fragment preserved by a private collector (Old Films & Stuff)

Length: Omar Khayyam: 8 reels , 76 minutes; A Lover’s Oath: 6 reels, 5,845 feet (though once listed with a runtime of 76 minutes, which doesn’t line up with the stated length of this cut)

Synopsis (synthesized from magazine summaries of the plot):

Omar Khayyam:

Set in 12th century Persia, the story begins with a preface in the youth of Omar Khayyam (Warde). Omar and his friends, Nizam (Weigel) and Hassan (Stevens), make a pact that whichever one of them becomes a success in life first will help out the others. In adulthood, Nizam has become a potentate and has given Omar a position so that he may continue his studies in mathematics and astronomy. Hassan, however, has grown into quite the villain. When he is expelled from the kingdom, he plots to kidnap Shireen (Key), the sheik’s daughter. Shireen is in love with Ali (Novarro). In the end it’s Hassan’s wife (Reicher) who slays the villain then kills herself.

A Lover’s Oath:

The daughter of a sheik, Shireen (Key), is in love with Ali (Novarro), the son of the ruler of a neighboring kingdom. Hassan covets Shireen and plots to kidnap her. Hassan is foiled by his wife. [The Sills’ edit places Ali and Shireen as protagonists, but there was little to no re-shooting done (absolutely none with Key or Novarro). So, most critics note how odd it is that all Ali does in the film is pitch woo, and does not save Shireen himself. This obviously wouldn’t have been an issue in the earlier cut, where Ali is a supporting character, often not even named in summaries and news items. Additional note: Post’s credit changes from “Vizier” to “Commander of the Faithful”]

Additional sequence(s) featured in the film (but I’m not sure where they fit in the continuity):

Celestial sequences featuring stars and planets moving through the cosmos

Angels spinning in a cyclone up to the heavens

A Potters’ shop sequence (relevant to a specific section of the poems)

Harem dance sequence choreographed by Novarro

Locations: palace gardens, street and marketplace scenes, ancient ruins

Points of Interest:

“The screen has been described as the last word in realism, but why confine it there? It can also be the last word in imaginative expression.”

Ferdinand P. Earle as quoted in Exhibitors Trade Review, 4 March 1922

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was a massive best seller. Ferdinand Pinney Earle was a classically trained artist who studied under William-Adolphe Bougueraeu and James McNeill Whistler in his youth. He also had years of experience creating art backgrounds, matte paintings, and art titles for films. Charles Wakefield Cadman was an accomplished composer of songs, operas, and operettas. Georges Benoit and Gordon Pollock were experienced photographic technicians. Edward S. Curtis was a widely renowned still photographer. Ramon Novarro was a name nobody knew yet—but they would soon enough.

When Earle chose The Rubaiyat as the source material for his directorial debut and collected such skilled collaborators, it seemed likely that the resulting film would be a landmark in the art of American cinema. Quite a few people who saw Earle’s Rubaiyat truly thought it would be:

William E. Wing writing for Camera, 9 September 1922, wrote:

“Mr. Earle…came from the world of brush and canvass, to spread his art upon the greater screen. He created a new Rubaiyat with such spiritual colors, that they swayed.”

…

“It has been my fortune to see some of the most wonderful sets that this Old Earth possesses, but I may truly say that none seized me more suddenly, or broke with greater, sudden inspiration upon the view and the brain, than some of Ferdinand Earle’s backgrounds, in his Rubaiyat.

“His vision and inspired art seem to promise something bigger and better for the future screen.”

As quoted in an ad in Film Year Book, 1923:

“Ferdinand Earle has set a new standard of production to live up to.”

Rex Ingram

“Fifty years ahead of the time.”

Marshall Neilan

The film was also listed among Fritz Lang’s Siegfried, Chaplin’s Gold Rush, Fairbanks’ Don Q, Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera and The Unholy Three, and Erich Von Stroheim’s Merry Widow by the National Board of Review as an exceptional film of 1925.

So why don’t we all know about this film? (Spoiler: it’s not just because it’s lost!)

The short answer is that multiple dubious legal challenges arose that prevented Omar’s general release in the US. The long answer follows BELOW THE JUMP!

Earle began the project in earnest in 1919. Committing The Rubaiyat to film was an ambitious undertaking for a first-time director and Earle was striking out at a time when the American film industry was developing an inferiority complex about the level of artistry in their creative output. Earle was one of a number of artists in the film colony who were going independent of the emergent studio system for greater protections of their creative freedoms.

In their adaptation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Earle and Co. hoped to develop new and perfect existing techniques for incorporating live-action performers with paintings and expand the idea of what could be accomplished with photographic effects in filmmaking. The Rubaiyat was an inspired choice. It’s not a narrative, but a collection of poetry. This gave Earle the opportunity to intersperse fantastical, poetic sequences throughout a story set in the lifetime of Omar Khayyam, the credited writer of the poems. In addition to the fantastic, Earle’s team would recreate 12th century Persia for the screen.

Earle was convinced that if his methods were perfected, it wouldn’t matter when or where a scene was set, it would not just be possible but practical to put on film. For The Rubaiyat, the majority of shooting was done against black velvet and various matte photography and multiple exposure techniques were employed to bring a setting 800+ years in the past and 1000s of miles removed to life before a camera in a cottage in Los Angeles.

Note: If you’d like to learn a bit more about how these effects were executed at the time, see the first installment of How’d They Do That.

Unfortunately, the few surviving minutes don’t feature much of this special photography, but what does survive looks exquisite:

see all gifs here

Earle, knowing that traditional stills could not be taken while filming, brought in Edward S. Curtis. Curtis developed techniques in still photography to replicate the look of the photographic effects used for the film. So, even though the film hasn’t survived, we have some pretty great looking representations of some of the 1000s of missing feet of the film.

Nearly a year before Curtis joined the crew, Earle began collaboration with composer Charles Wakefield Cadman. In another bold creative move, Cadman and Earle worked closely before principal photography began so that the score could inform the construction and rhythm of the film and vice versa.

By the end of 1921 the film was complete. After roughly 9 months and the creation of over 500 paintings, The Rubaiyat was almost ready to meet its public. However, the investors in The Rubaiyat, Inc., the corporation formed by Earle to produce the film, objected to the ample reference to wine drinking (a comical objection if you’ve read the poems) and wanted the roles of the young lovers (played by as yet unknown Ramon Novarro and Kathleen Key) to be expanded. The dispute with Earle became so heated that the financiers absconded with the bulk of the film to New York. Earle filed suit against them in December to prevent them from screening their butchered and incomplete cut. Cadman supported Earle by withholding the use of his score for the film.

Later, Eastern Film Corp. brokered a settlement between the two parties, where Earle would get final cut of the film and Eastern would handle its release. Earle and Eastern agreed to change the title from The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam to simply Omar. Omar had its first official preview in New York City. It was tentatively announced that the film would have a wide release in the autumn.

However, before that autumn, director Norman Dawn launched a dubious patent-infringement suit against Earle and others. Dawn claimed that he owned the sole right to use multiple exposures, glass painting for single exposure, and other techniques that involved combining live action with paintings. All the cited techniques had been widespread in the film industry for a decade already and eventually and expectedly Dawn lost the suit. Despite Earle’s victory, the suit effectively put the kibosh on Omar’s release in the US.

Earle moved on to other projects that didn’t come to fruition, like a Theda Bara film and a frankly amazing sounding collaboration with Cadman to craft a silent-film opera of Faust. Omar did finally get a release, albeit only in Australia. Australian news outlets praised the film as highly as those few lucky attendees of the American preview screenings did. The narrative was described as not especially original, but that it was good enough in view of the film’s artistry and its imaginative “visual phenomena” and the precision of its technical achievement.

One reviewer for The Register, Adelaide, SA, wrote:

“It seems almost an impossibility to make a connected story out of the short verse of the Persian of old, yet the producer of this classic of the screen… has succeeded in providing an entertainment that would scarcely have been considered possible. From first to last the story grips with its very dramatic intensity.”

While Omar’s American release was still in limbo, “Ramon Samaniegos” made a huge impression in Rex Ingram’s Prisoner of Zenda (1922, extant) and Scaramouche (1923, extant) and took on a new name: Ramon Novarro. Excitement was mounting for Novarro’s next big role as the lead in the epic Ben-Hur (1925, extant) and the Omar project was re-vivified.

A new company, Astor Distribution Corp., was formed and purchased the distribution rights to Omar. Astor hired actor (note, not an editor) Milton Sills to re-cut the film to make Novarro and Key more prominent. The company also re-wrote the intertitles, reduced the films runtime by more than ten minutes, and renamed the film A Lover’s Oath. Earle had moved on by this point, vowing to never direct again. In fact, Earle was indirectly working with Novarro and Key again at the time, as an art director on Ben-Hur!

Despite Omar’s seemingly auspicious start in 1920, it was only released in the US on the states rights market as a cash-in on the success of one of its actors in a re-cut form five years later.

That said, A Lover’s Oath still received some good reviews from those who did manage to see it. Most of the negative criticism went to the story, intertitles, and Sills’ editing.

What kind of legacy could/should Omar have had? I’m obviously limited in my speculation by the fact that the film is lost, but there are a few key facts about the film’s production, release, and timing to consider.

The production budget was stated to be $174,735. That is equivalent to $3,246,994.83 in 2024 dollars. That is a lot of money, but since the production was years long and Omar was a period film set in a remote locale and features fantastical special effects sequences, it’s a modest budget. For contemporary perspective, Robin Hood (1922, extant) cost just under a million dollars to produce and Thief of Bagdad (1924, extant) cost over a million. For a film similarly steeped in spectacle to have nearly 1/10th of the budget is really very noteworthy. And, perhaps if the film had ever had a proper release in the US—in Earle’s intended form (that is to say, not the Sills cut)—Omar may have made as big of a splash as other epics.

It’s worth noting here however that there are a number of instances in contemporary trade and fan magazines where journalists off-handedly make this filmmaking experiment about undermining union workers. Essentially implying that that value of Earle’s method would be to continue production when unionized workers were striking. I’m sure that that would absolutely be a primary thought for studio heads, but it certainly wasn’t Earle’s motivation. Often when Earle talks about the method, he focuses on being able to film things that were previously impossible or impracticable to film. Driving down filming costs from Earle’s perspective was more about highlighting the artistry of his own specialty in lieu of other, more demanding and time-consuming approaches, like location shooting.

This divide between artists and studio decision makers is still at issue in the American film and television industry. Studio heads with billion dollar salaries constantly try to subvert unions of skilled professionals by pursuing (as yet) non-unionized labor. The technical developments of the past century have made Earle’s approach easier to implement. However, just because you don’t have to do quite as much math, or time an actor’s movements to a metronome, does not mean that filming a combination of painted/animated and live-action elements does not involve skilled labor.

VFX artists and animators are underappreciated and underpaid. In every new movie or TV show you watch there’s scads of VFX work done even in films/shows that have mundane, realistic settings. So, if you love a film or TV show, take the effort to appreciate the work of the humans who made it, even if their work was so good you didn’t notice it was done. And, if you’ve somehow read this far, and are so out of the loop about modern filmmaking, Disney’s “live-action” remakes are animated films, but they’ve just finagled ways to circumvent unions and low-key delegitimize the skilled labor of VFX artists and animators in the eyes of the viewing public. Don’t fall for it.

VFX workers in North America have a union under IATSE, but it’s still developing as a union and Marvel & Disney workers only voted to unionize in the autumn of 2023. The Animation Guild (TAG), also under the IATSE umbrella, has a longer history, but it’s been growing rapidly in the past year. A strike might be upcoming this year for TAG, so keep an eye out and remember to support striking workers and don’t cross picket lines, be they physical or digital!

Speaking of artistry over cost-cutting, I began this post with a mention that in the early 1920s, the American film industry was developing an inferiority complex in regard to its own artistry. This was in comparison to the European industries, Germany’s being the largest at the time. It’s frustrating to look back at this period and see acceptance of the opinion that American filmmakers weren’t bringing art to film. While yes, the emergent studio system was highly capitalistic and commercial, that does not mean the American industry was devoid of home-grown artists.

United Artists was formed in 1919 by Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and D.W. Griffith precisely because studios were holding them back from investing in their art—within the same year that Earle began his Omar project. While salaries and unforgiving production schedules were also paramount concerns in the filmmakers going independent, a primary impetus was that production/distribution heads exhibited too much control over what the artists were trying to create.

Fairbanks was quickly expanding his repertoire in a more classical and fantastic direction. Cecil B. DeMille made his first in a long and very successful string of ancient epics. And the foreign-born children of the American film industry, Charlie Chaplin, Rex Ingram, and Nazimova, were poppin’ off! Chaplin was redefining comedic filmmaking. Ingram was redefining epics. Nazimova independently produced what is often regarded as America’s first art film, Salome (1923, extant), a film designed by Natacha Rambova, who was *gasp* American. Earle and his brother, William, had ambitious artistic visions of what could be done in the American industry and they also had to self-produce to get their work done.

Meanwhile, studio heads, instead of investing in the artists they already had contracts with, tried to poach talent from Europe with mixed success (in this period, see: Ernst Lubitsch, F.W. Murnau, Benjamin Christensen, Mauritz Stiller, Victor Sjöström, and so on). I’m in no way saying it was the wrong call to sign these artists, but all of these filmmakers, even if they found success in America, had stories of being hired to inject the style and artistry that they developed in Europe into American cinema, and then had their plans shot down or cut down to a shadow of their creative vision. Even Stiller, who tragically died before he had the opportunity to establish himself in the US, faced this on his first American film, The Temptress (1926, extant), on which he was replaced. Essentially, the studio heads’ actions were all hot air and spite for the filmmakers who’d gone independent.

Finally I would like to highlight Ferdinand Earle’s statement to the industry, which he penned for from Camera in 14 January 1922, when his financial backers kidnapped his film to re-edit it on their terms:

MAGNA CHARTA

Until screen authors and producers obtain a charter specifying and guaranteeing their privileges and rights, the great slaughter of unprotected motion picture dramas will go merrily on.

Some of us who are half artists and half fighters and who are ready to expend ninety per cent of our energy in order to win the freedom to devote the remaining ten per cent to creative work on the screen, manage to bring to birth a piteous, half-starved art progeny.

The creative artist today labors without the stimulus of a public eager for his product, labors without the artistic momentum that fires the artist’s imagination and spurs his efforts as in any great art era.

Nowadays the taint of commercialism infects the seven arts, and the art pioneer meets with constant petty worries and handicaps.

Only once in a blue moon, in this matter-of-fact, dollar-wise age can the believer in better pictures hope to participate in a truely [sic] artistic treat.

In the seven years I have devoted to the screen, I have witnessed many splendid photodramas ruined by intruding upstarts and stubborn imbeciles. And I determined not to launch the production of my Opus No. 1 until I had adequately protected myself against all the usual evils of the way, especially as I was to make an entirely new type of picture.

In order that my film verison [sic] of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam might be produced under ideal conditions and safeguarded from intolerable interferences and outside worries, I entered into a contract with the Rubaiyat, Inc., that made me not only president of the corporation and on the board of directors, but which set forth that I was to be author, production manager, director, cutter and film editor as well as art director, and that no charge could be made against the production without my written consent, and that my word was to be final on all matters of production. The late George Loane Tucker helped my attorney word the contract, which read like a splendid document.

Alas, I am now told that only by keeping title to a production until it is declared by yourself to be completed is it safe for a scenario writer, an actor or a director, who is supposedly making his own productions, to contract with a corporation; otherwise he is merely the servant of that corporation, subject at any moment to discharge, with the dubious redress of a suit for damages that can with difficulty be estimated and proven.

Can there be any hope of better pictures as long as contracts and copyrights are no protection against financial brigands and bullies?

We have scarcely emerged from barbarism, for contracts, solemnly drawn up between human beings, in which the purposes are set forth in the King’s plainest English, serve only as hurdles over which justice-mocking financiers and their nimble attorneys travel with impunity, riding rough shod over the author or artist who cannot support a legal army to defend his rights. The phrase is passed about that no contract is invioliable [sic]—and yet we think we have reached a state of civilization!

The suit begun by my attorneys in the federal courts to prevent the present hashed and incomplete version of my story from being released and exhibited, may be of interest to screen writers. For the whole struggle revolves not in the slightest degree around the sanctity of the contract, but centers around the federal copyright of my story which I never transferred in writing otherwise, and which is being brazenly ignored.

Imagine my production without pictorial titles: and imagine “The Rubaiyat” with a spoken title as follows, “That bird is getting to talk too much!”—beside some of the immortal quatrains of Fitzgerald!

One weapon, fortunately, remains for the militant art creator, when all is gone save his dignity and his sense of humor; and that is the rapier blade of ridicule, that can send lumbering to his retreat the most brutal and elephant-hided lord of finance.

How edifying—the tableau of the man of millions playing legal pranks upon men such as Charles Wakefield Cadman, Edward S. Curtis and myself and others who were associated in the bloody venture of picturizing the Rubaiyat! It has been gratifying to find the press of the whole country ready to champion the artist’s cause.

When the artist forges his plowshare into a sword, so to speak, he does not always put up a mean fight.

What publisher would dare to rewrite a sonnet of John Keats or alter one chord of a Chopin ballade?

Creative art of a high order will become possible on the screen only when the rights of established, independent screen producers, such as Rex Ingram and Maurice Tourneur, are no longer interferred with and their work no longer mutilated or changed or added to by vandal hands. And art dramas, conceived and executed by masters of screen craft, cannot be turned out like sausages made by factory hands. A flavor of individuality and distinction of style cannot be preserved in machine-made melodramas—a drama that is passed from hand to hand and concocted by patchworkers and tinkerers.

A thousand times no! For it will always be cousin to the sausage, and be like all other—sausages.

The scenes of a master’s drama may have a subtle pictorial continuity and a power of suggestion quite like a melody that is lost when just one note is changed. And the public is the only test of what is eternally true or false. What right have two or three people to deprive millions of art lovers of enjoying an artist’s creation as it emerged from his workshop?

“The Rubaiyat” was my first picture and produced in spite of continual and infernal interferences. It has taught me several sad lessons, which I have endeavored in the above paragraphs to pass on to some of my fellow sufferers. It is the hope that I am fighting, to a certain extent, their battle that has given me the courage to continue, and that has prompted me to write this article. May such hubbubs eventually teach or inforce a decent regard for the rights of authors and directors and tend to make the existence of screen artisans more secure and soothing to the nerves.

FERDINAND EARLE.

---

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

Transcribed Sources & Annotations over on the WMM Blog!

See the Timeline for Ferdinand P. Earle's Rubaiyat Adaptation

#1920s#1923#1925#omar khayyam#ferdinand pinney earle#ramon novarro#independent film#american film#silent cinema#silent era#silent film#classic cinema#classic movies#classic film#film history#history#Charles Wakefield Cadman#cinematography#The Rubaiyat#cinema#film#lost film

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you think heathcliffe can be seen as the devil (or at least the manifestation of the archetype) who loses his eden (cathy) to humanity (linton)

I LOVE THIS QUESTION! I've thought about this a lot in recent months and much has been written about this subject as you probably know. I studied a bit of Paradise Lost in a class on the Renaissance era in my last semester this past autumn, which is also when I had my Brontë class. I did an essay focusing on Edenic myth for my Ren class and now I notice it everywhere, & I've really been seeing the Miltonian Hero & themes in the Brontë works, & especially did in my re-read of Wuthering Heights about two months ago. But instead of just regurgitating all that's been written about the subject, I will discuss things simply as I understand them, although I do borrow a bit from professor Rodger Wilkie's lecture which I link below (I'm not affiliated with him in any way, I found his videos on my own when I was researching the Brontë novels).

Edenic Myth from the POVs of Cathy I & II as Eve:

I've been seeing the Edenic theme from Cathy I and Cathy II's lenses. I believe that the plotline of Cathy II being lured by Heathcliff into his "wolf's den" so to speak reminds me not only a lot of Little Red Riding Hood but also of Eve and the apple. I think there is a seductive undertone although I don't think Heathcliff is really attracted to her or vice-versa; he still attracts her using his son Linton Heathcliff. There is an essay I've been meaning to post excerpts from but haven't bc the material is triggering, but it's Juliet McMaster's "The Courtship and Honeymoon of Mr. and Mrs. Linton Heathcliff: Emily Brontë's Sexual Imagery" and discusses the weird dynamic between Cathy II, Heathcliff, & Linton II.

I find it very interesting that nature is so tied to Heathcliff that it's by disobeying her father's (God's) wishes that Cathy II meets him and ends up ensnared by him. As I see it, Cathy II "takes the apple" like Eve, because it is her overwhelming curiosity that leads her to the Heights, and Heathcliff does play the trickster with her, manipulating her and lying to her more than he does to any other character. He was upfront with his intentions to Isabella and everyone else he ever associated with. But with Cathy II, although he is partly honest about some things, he deceives her by forging Linton Heathcliff's letters to her, causing her to fall in love with "Linton" (Heathcliff pretending to write as him) — I'm glad I found McMaster's essay & that it talks about this point, because I find it to be one of the most fascinating plotlines in the whole story, and think Cathy II is the most underrated character & hate how Linton is often forgotten (I feel McMaster, like most readers, isn't as sympathetic to him as she could be). The description of Cathy I and her hair reminds me of the descriptions of Eve in Milton, and I believe both Catherines are meant to look alike.

I also think young Heathcliff and Cathy could be said to be like Adam and Eve in Eden (the moors) — the "I am Heathcliff" & other soulmate allusions are very much like Eve being made from Adam. I of course hate that aspect of this patriarchal myth perhaps more than any other aspect because it is in direct opposition to actual scientific biology with all males starting with the X chromosome of which females have two of — but I digress from my eternal feminist/atheist/evolutionist rage. When Heathcliff tells Cathy that she's damned them both, killed them both, this is very much like Adam and Eve being killed by Eve's decision (in this case, Cathy's choice to marry Linton). However, in this framework, Heathcliff would be both Adam and Lucifer, and Linton would be both civilization and to some extent a version of Lucifer, with the apple being marriage and normalcy, or maybe you could argue that Cathy also has a bit of the devil in her in that she came up with this decision herself and still wants to rebel much like Lucifer. The Fall is written all over this novel, however one may view the intricacies, which Emily was surely going off of intuitively and not racking her brain with explaining through any one official framework.

Heathcliff as Satan, Cathy as Eden or Heaven:

Yes. The metaphor works best with Heathcliff being the Miltonian Hero aka Satan, and I believe Emily was very influenced by this, especially seen by Heathcliff's exile, and the quest for vengeance which necessitates his return. However, I have never considered Cathy as being Heathcliff's Eden until now, but this works very well — what maybe works even better would be Cathy representing Heaven, which is what Satan is also barred from. However, Cathy's house is certainly like Eden, with Heathcliff having to sneak into it to escape Linton (who again, is sort of like God/a Godly, patriarchal figure). This is exactly like Satan sneaking into Eden — he's caught by the angels sort of like Heathcliff is caught by Nelly and the servants. But Cathy does die, and so she is lost, and Heathcliff can only hope to get her back one day like the promise of Paradise returning with the Second Coming or whatever (I'm not actually well versed in Christian literature). But I have read that apparently in the Bible, "paradise" can refer to both Eden and heaven, so it may be better to say that Cathy represents not only Eve but also paradise in both senses of the term. Note how both Heathcliff and Cathy say that they aren't going to Heaven, and indeed they both become ghosts damned to wander Earth -- yet ironically, that Earth is their paradise on the moors, and so they actually have gone to their own personal Heaven although it is not the Christian one.

On Linton representing humanity:

I wouldn't say that Linton represents humanity as much as he more accurately represents civilization/society as opposed to Heathcliff who represents the wild (and as his name indicates, the Heath/Moors specifically). But this fits with what you're saying as the post-Edenic world is society/civilization/humanity all at once and the distinctions between these heavy concepts are all blurry.

I find in much romance novels featuring love triangle dynamics, there is a Freudian triad of superego/ego/id going on. One love interest will represent the id (natural instincts/subconscious desires) and one the supergo (properness/upholding the status quo) to the main character's ego. To some extent this can be seen in all media ("the human heart in conflict with itself" as GRRM put it) but imo it's a great way to look at things categorically. The id and superego must be reconciled for the sake of the ego.

Example: in Titanic, Cal & her mother are the patriarchal/societally proper superego whereas Jack & the poor immigrants represent Rose's id of wanting to be free from high society women's standards. She ends up with neither Cal & co. nor Jack & co., but on her own with a newly refreshed ego that has learned not to repress the id side so much. Jack's whole role was to teach her (ie the spit practice scene) to unrepress her id, but as she demonstrates in the wild Irish party scene, she will always keep some of her high-bred characteristics (like ballet as a party trick).

Anyway, Cathy has to choose between Heathcliff and Edgar. As we learn from her speech which Heathcliff walks out on, she planned that her marriage to Edgar would benefit Heathcliff by allowing her to financially support him. She thought that by marrying Edgar she could have both men. As Nelly sort of tries to tell her, this isn't possible. In marrying Edgar and being a "proper lady" to him, Cathy has symbolically repressed her id; Heathcliff runs away as soon as he hears she makes the choice. By becoming a housewife and then a mother, she dies inside of that house, when all she wanted was to be free on the fields. It is specifically after Heathcliff comes back that she dies because he reminds her of what she's been missing.

Recommendation:

There's a professor named Rodger Wilkie who has a Brontë lecture series from one of his classes available on Youtube — I've seen them all and they're all amazing, 10/10 recommend every single one. In his second Wuthering Heights lecture he talks about the influence of John Milton's Paradise Lost in reference to Heathcliff: (https://youtu.be/WF3DDu2cH3Q?si=yM3mNXaVgQkOqVS3)

youtube

#literature#english literature#ask#asks#wuthering heights#emily brontë#the brontë sisters#books#heathcliff#heathcliff wuthering heights#analysis#john milton#paradise lost#eden#garden of eden#my writing#my analysis#my essays

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

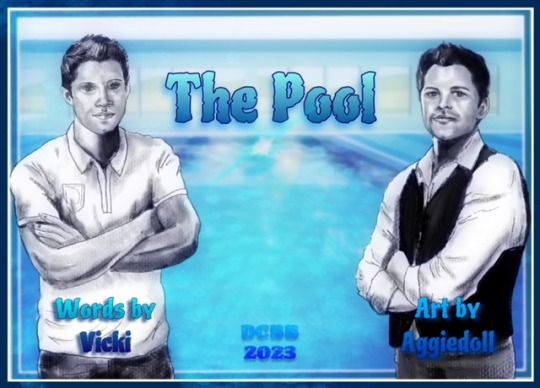

The Pool

Author: Vicki

Artist: Aggiedoll

Rating: Teen

Pairings: Dean Winchester/Castiel, Anna Milton/Charlie Bradbury, Sam Winchester/Jessica Moore

Length: 22531

Warnings: Past reference to emotionally abuse relationship (Cas/Other)

Tags: Lifeguard Dean, Editor Castiel, Alternate Universe

Summary: Dean is a lifeguard at a pool in a private school where Sam studies, one day a handsome stranger named Castiel starts coming to the morning swim classes.

Link to Fic | Link to Art

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Saint: Island of Chance (5.22, ITC, 1967)

"Of course, Charles Krayford has become a twentieth century legend, just like Schweitzer. A totally dedicated man of medicine; a great doctor; a towering hero figure."

"You don't go along with the general adoration?"

"I'm a professional cynic."

"Is that a good living?"

"Oh, dandy! I have the confidence of everyone - and the trust of nobody."

#the saint#island of chance#itc#1967#leslie charteris#leslie norman#leigh vance#roger moore#sue lloyd#david bauer#patricia donahue#alex scott#milton johns#thomas baptiste#christopher carlos#norman jones#richard owens#kenneth gardnier#danny daniels#tommy eytle#charles hyatt#a... morally complex one‚ this. Simon's in the West Indies to meet up with an old pal (who naturally gets murdered even before the opening#titles) and gets drawn into a mystery around a hidden fortune and a scientist working towards a universal cure for all ills... Bauer makes#his 5th and final appearance as the scientist‚ whilst Sue Lloyd had been seen in 2.19; between that episode and this one she'd had a#costarring role in ITC's The Baron and her career was going from strength to strength. being set in the West Indies it's refreshing to find#this episode has multiple speaking parts for black actors (altho it must be said mostly in servant or worker roles) including an appearance#by Tommy Eytle playing calypso in a bar; Eytle had been one of the artists who led the hugely popular surge in calypso that had swept the#uk in the previous decade. things take a darker turn midway thru the ep as a woman is murdered onscreen (as mentioned before a fairly rare#thing on british tv in this era)‚ Simon plays russian roulette with two henchmen to get them to talk‚ and finally he apparently was willing#to overlook the murders of his old friend and a nice lady he met so that dr wizard can keep working on his miracle serum (?!)

1 note

·

View note