#making the election in the 1860s-1870s

Text

If we’re being realistic here like historically speaking coconut2020 would have won the election and the voter fraud would have been accepted as like. Well! That’s how the voters voted!

#voter fraud in the us up through the progressive era was widely accepted and actually encouraged by the two major political parties#if the election took place post revolutionary war (hamilton fanfic)#and if Manberg can be seen as a nation with an economic depression#the first U.S. depression was in the 1870s#making the election in the 1860s-1870s#voter fraud would have been encouraged by all parties

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone wrote this as a factual historically backed response to the claim that somehow Democrats and Republicans changed sides.

June 17, 1854

The Republican Party is officially founded as an abolitionist party to slavery in the United States.

October 13, 1858

During the Lincoln-Douglas debates, U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas (D-IL) said, “If you desire negro citizenship, if you desire to allow them to come into the State and settle with the white man, if you desire them to vote on an equality with yourselves, and to make them eligible to office, to serve on juries, and to adjudge your rights, then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican party, who are in favor of the citizenship of the negro. For one, I am opposed to negro citizenship in any and every form. I believe this Government was made on the white basis. I believe it was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever, and I am in favor of confining citizenship to white men, men of European birth and descent, instead of conferring it upon negroes, Indians, and other inferior races.”. Douglas became the Democrat Party’s 1860 presidential nominee.

April 16, 1862

President Lincoln signed the bill abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. In Congress, almost every Republican voted for yes and most Democrats voted no.

July 17, 1862

Over unanimous Democrat opposition, the Republican Congress passed The Confiscation Act stating that slaves of the Confederacy “shall be forever free”.

April 8, 1864

The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. Senate with 100% Republican support, 63% Democrat opposition.

January 31, 1865

The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. House with unanimous Republican support and intense Democrat opposition.November 22, 1865

Republicans denounced the Democrat legislature of Mississippi for enacting the “black codes” which institutionalized racial discrimination.

February 5, 1866

U.S. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens (R-PA) introduced legislation (successfully opposed by Democrat President Andrew Johnson) to implement “40 acres and a mule” relief by distributing land to former slaves.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rights to blacks.

May 10, 1866

The U.S. House passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the laws to all citizens. 100% of Democrats vote no.

June 8, 1866

The U.S. Senate passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the law to all citizens. 94% of Republicans vote yes and 100% of Democrats vote no.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rights to blacks in the District of Columbia.

July 16, 1866

The Republican Congress overrode Democrat President Andrew Johnson’s veto of legislation protecting the voting rights of blacks.

March 30, 1868

Republicans begin the impeachment trial of Democrat President Andrew Johnson who declared, “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government of white men.”September 12, 1868

Civil rights activist Tunis Campbell and 24 other blacks in the Georgia Senate (all Republicans) were expelled by the Democrat majority and would later be reinstated by the Republican Congress.

October 7, 1868

Republicans denounced Democrat Party’s national campaign theme: “This is a white man’s country: Let white men rule.”

October 22, 1868

While campaigning for re-election, Republican U.S. Rep. James Hinds (R-AR) was assassinated by Democrat terrorists who organized as the Ku Klux Klan. Hinds was the first sitting congressman to be murdered while in office.

December 10, 1869

Republican Gov. John Campbell of the Wyoming Territory signed the FIRST-in-nation law granting women the right to vote and hold public office.

February 3, 1870

After passing the House with 98% Republican support and 97% Democrat opposition, Republicans’ 15th Amendment was ratified, granting the vote to ALL Americans regardless of race.

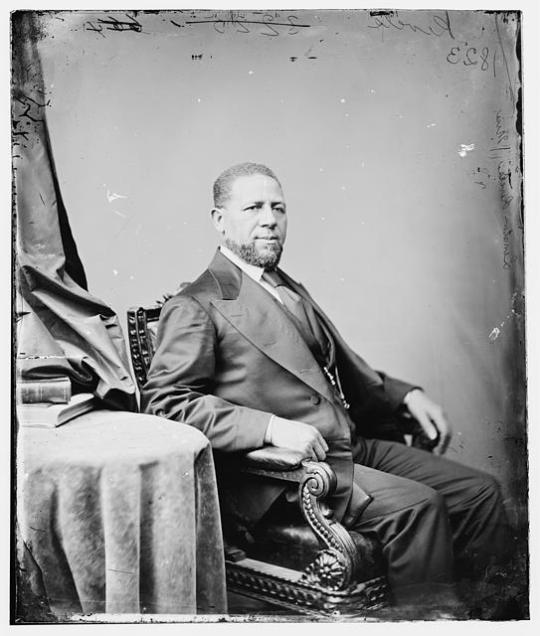

February 25, 1870

Hiram Rhodes Revels (R-MS) becomes the first black to be seated in the United States Senate.

May 31, 1870

President U.S. Grant signed the Republicans’ Enforcement Act providing stiff penalties for depriving any American’s civil rights.

June 22, 1870

Ohio Rep. Williams Lawrence created the U.S. Department of Justice to safeguard the civil rights of blacks against Democrats in the South.

September 6, 1870

Women voted in Wyoming in first election after women’s suffrage signed into law by Republican Gov. John Campbell.

February 1, 1871

Rep. Jefferson Franklin Long (R-GA) became the first black to speak on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

February 28, 1871

The Republican Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1871 providing federal protection for black voters.

April 20, 1871

The Republican Congress enacted the Ku Klux Klan Act, outlawing Democrat Party-affiliated terrorist groups which oppressed blacks and all those who supported them.

October 10, 1871

Following warnings by Philadelphia Democrats against black voting, Republican civil rights activist Octavius Catto was murdered by a Democrat Party operative. His military funeral was attended by thousands.

October 18, 1871

After violence against Republicans in South Carolina, President Ulysses Grant deployed U.S. troops to combat Democrat Ku Klux Klan terrorists.

November 18, 1872

Susan B. Anthony was arrested for voting after boasting to Elizabeth Cady Stanton that she voted for “Well, I have gone and done it — positively voted the straight Republican ticket.”January 17, 1874

Armed Democrats seized the Texas state government, ending Republican efforts to racially integrate.

September 14, 1874

Democrat white supremacists seized the Louisiana statehouse in attempt to overthrow the racially-integrated administration of Republican Governor William Kellogg. Twenty-seven were killed.

March 1, 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, guaranteeing access to public accommodations without regard to race, was signed by Republican President U.S. Grant and passed with 92% Republican support over 100% Democrat opposition.

January 10, 1878

U.S. Senator Aaron Sargent (R-CA) introduced the Susan B. Anthony amendment for women’s suffrage. The Democrat-controlled Senate defeated it four times before the election of a Republican House and Senate that guaranteed its approval in 1919.

February 8, 1894

The Democrat Congress and Democrat President Grover Cleveland joined to repeal the Republicans’ Enforcement Act which had enabled blacks to vote.

January 15, 1901

Republican Booker T. Washington protested the Alabama Democrat Party’s refusal to permit voting by blacks.

May 29, 1902

Virginia Democrats implemented a new state constitution condemned by Republicans as illegal, reducing black voter registration by almost 90%.

February 12, 1909

On the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, black Republicans and women’s suffragists Ida Wells and Mary Terrell co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

May 21, 1919

The Republican House passed a constitutional amendment granting women the vote with 85% of Republicans and only 54% of Democrats in favor. In the Senate 80% of Republicans voted yes and almost half of Democrats voted no.

August 18, 1920

The Republican-authored 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote became part of the Constitution. Twenty-six of the 36 states needed to ratify had Republican-controlled legislatures.

January 26, 1922

The House passed a bill authored by U.S. Rep. Leonidas Dyer (R-MO) making lynching a federal crime. Senate Democrats blocked it by filibuster.

June 2, 1924

Republican President Calvin Coolidge signed a bill passed by the Republican Congress granting U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans.

October 3, 1924

Republicans denounced three-time Democrat presidential nominee William Jennings Bryan for defending the Ku Klux Klan at the 1924 Democratic National Convention.

June 12, 1929

First Lady Lou Hoover invited the wife of black Rep. Oscar De Priest (R-IL) to tea at the White House, sparking protests by Democrats across the country.

August 17, 1937

Republicans organized opposition to former Ku Klux Klansman and Democrat U.S. Senator Hugo Black who was later appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by FDR. Black’s Klan background was hidden until after confirmation.

June 24, 1940

The Republican Party platform called for the integration of the Armed Forces. For the balance of his terms in office, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (D) refused to order it.

August 8, 1945

Republicans condemned Harry Truman’s surprise use of the atomic bomb in Japan. It began two days after the Hiroshima bombing when former Republican President Herbert Hoover wrote that “The use of the atomic bomb, with its indiscriminate killing of women and children, revolts my soul.”

May 17, 1954

Earl Warren, California’s three-term Republican Governor and 1948 Republican vice presidential nominee, was nominated to be Chief Justice delivered the landmark decision “Brown v. Board of Education”.

November 25, 1955

Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s administration banned racial segregation of interstate bus travel.

March 12, 1956

Ninety-seven Democrats in Congress condemned the Supreme Court’s “Brown v. Board of Education” decision and pledged (Southern Manifesto) to continue segregation.

June 5, 1956

Republican federal judge Frank Johnson ruled in favor of the Rosa Parks decision striking down the “blacks in the back of the bus” law.

November 6, 1956

African-American civil rights leaders Martin Luther King and Ralph Abernathy voted for Republican Dwight Eisenhower for President.

September 9, 1957

President Eisenhower signed the Republican Party’s 1957 Civil Rights Act.

September 24, 1957

Sparking criticism from Democrats such as Senators John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, President Eisenhower deployed the 82nd Airborne Division to Little Rock, AR to force Democrat Governor Orval Faubus to integrate their public schools.

May 6, 1960

President Eisenhower signed the Republicans’ Civil Rights Act of 1960, overcoming a 125-hour, ’round-the-clock filibuster by 18 Senate Democrats.

May 2, 1963

Republicans condemned Bull Connor, the Democrat “Commissioner of Public Safety” in Birmingham, AL for arresting over 2,000 black schoolchildren marching for their civil rights.

September 29, 1963

Gov. George Wallace (D-AL) defied an order by U.S. District Judge Frank Johnson (appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower) to integrate Tuskegee High School.

June 9, 1964

Republicans condemned the 14-hour filibuster against the 1964 Civil Rights Act by U.S. Senator and former Ku Klux Klansman Robert Byrd (D-WV), who served in the Senate until his death in 2010.

June 10, 1964

Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) criticized the Democrat filibuster against 1964 Civil Rights Act and called on Democrats to stop opposing racial equality. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was introduced and approved by a majority of Republicans in the Senate. The Act was opposed by most southern Democrat senators, several of whom were proud segregationists — one of them being Al Gore Sr. (D). President Lyndon B. Johnson relied on Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen, the Republican leader from Illinois, to get the Act passed.

August 4, 1965

Senate Leader Everett Dirksen (R-IL) overcame Democrat attempts to block 1965 Voting Rights Act. Ninety-four percent of Republicans voted for the landmark civil rights legislation while 27% of Democrats opposed. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, abolishing literacy tests and other measures devised by Democrats to prevent blacks from voting, was signed into law. A higher percentage of Republicans voted in favor.

February 19, 1976

President Gerald Ford formally rescinded President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s notorious Executive Order 9066 authorizing the internment of over 120,000 Japanese-Americans during WWII.

September 15, 1981

President Ronald Reagan established the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities to increase black participation in federal education programs.

June 29, 1982

President Ronald Reagan signed a 25-year extension of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

August 10, 1988

President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, compensating Japanese-Americans for the deprivation of their civil rights and property during the World War II internment ordered by FDR.

November 21, 1991

President George H. W. Bush signed the Civil Rights Act of 1991 to strengthen federal civil rights legislation.

August 20, 1996

A bill authored by U.S. Rep. Susan Molinari (R-NY) to prohibit racial discrimination in adoptions, part of Republicans’ “Contract With America”, became law.

July 2, 2010

Clinton says Byrd joined KKK to help him get elected

Just a “fleeting association”. Nothing to see here.

Only a willing fool (and there quite a lot out there) would accept and recite the nonsensical that one bright, sunny day Democrats and Republicans just up and decided to “switch” political positions and cite the “Southern Strategy” as the uniform knee-jerk retort. Even today, it never takes long for a Democrat to play the race card purely for political advantage.Thanks to the Democrat Party, blacks have the distinction of being the only group in the United States whose history is a work-in-progress.

The idea that “the Dixiecrats joined the Republicans” is not quite true, as you note. But because of Strom Thurmond it is accepted as a fact. What happened is that the **next** generation (post 1965) of white southern politicians — Newt, Trent Lott, Ashcroft, Cochran, Alexander, etc — joined the GOP.So it was really a passing of the torch as the old segregationists retired and were replaced by new young GOP guys. One particularly galling aspect to generalizations about “segregationists became GOP” is that the new GOP South was INTEGRATED for crying out loud, they accepted the Civil Rights revolution. Meanwhile, Jimmy Carter led a group of what would become “New” Democrats like Clinton and Al Gore.

There weren’t many Republicans in the South prior to 1964, but that doesn’t mean the birth of the southern GOP was tied to “white racism.” That said, I am sure there were and are white racist southern GOP. No one would deny that. But it was the southern Democrats who were the party of slavery and, later, segregation. It was George Wallace, not John Tower, who stood in the southern schoolhouse door to block desegregation! The vast majority of Congressional GOP voted FOR the Civil Rights of 1964-65. The vast majority of those opposed to those acts were southern Democrats. Southern Democrats led to infamous filibuster of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.The confusion arises from GOP Barry Goldwater’s vote against the ’64 act. He had voted in favor or all earlier bills and had led the integration of the Arizona Air National Guard, but he didn’t like the “private property” aspects of the ’64 law. In other words, Goldwater believed people’s private businesses and private clubs were subject only to market forces, not government mandates (“We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.”) His vote against the Civil Rights Act was because of that one provision was, to my mind, a principled mistake.This stance is what won Goldwater the South in 1964, and no doubt many racists voted for Goldwater in the mistaken belief that he opposed Negro Civil Rights. But Goldwater was not a racist; he was a libertarian who favored both civil rights and property rights.Switch to 1968.Richard Nixon was also a proponent of Civil Rights; it was a CA colleague who urged Ike to appoint Warren to the Supreme Court; he was a supporter of Brown v. Board, and favored sending troops to integrate Little Rock High). Nixon saw he could develop a “Southern strategy” based on Goldwater’s inroads. He did, but Independent Democrat George Wallace carried most of the deep south in 68. By 1972, however, Wallace was shot and paralyzed, and Nixon began to tilt the south to the GOP. The old guard Democrats began to fade away while a new generation of Southern politicians became Republicans. True, Strom Thurmond switched to GOP, but most of the old timers (Fulbright, Gore, Wallace, Byrd etc etc) retired as Dems.Why did a new generation white Southerners join the GOP? Not because they thought Republicans were racists who would return the South to segregation, but because the GOP was a “local government, small government” party in the old Jeffersonian tradition. Southerners wanted less government and the GOP was their natural home.Jimmy Carter, a Civil Rights Democrat, briefly returned some states to the Democrat fold, but in 1980, Goldwater’s heir, Ronald Reagan, sealed this deal for the GOP. The new “Solid South” was solid GOP.BUT, and we must stress this: the new southern Republicans were *integrationist* Republicans who accepted the Civil Rights revolution and full integration while retaining their love of Jeffersonian limited government principles.

Oh wait, princess, I am not done yet.

Where Teddy Roosevelt invited Booker T. Washington to dinner, Woodrow Wilson re-segregated the U.S. government and had the pro-Klan film “Birth of a Nation” screened in his White House.

Wilson and FDR carried all 11 states of the Old Confederacy all six times they ran, when Southern blacks had no vote. Disfranchised black folks did not seem to bother these greatest of liberal icons.

As vice president, FDR chose “Cactus Jack” Garner of Texas who played a major role in imposing a poll tax to keep blacks from voting.

Among FDR’s Supreme Court appointments was Hugo Black, a Klansman who claimed FDR knew this when he named him in 1937 and that FDR told him that “some of his best friends” in Georgia were Klansmen.

Black’s great achievement as a lawyer was in winning acquittal of a man who shot to death the Catholic priest who had presided over his daughter’s marriage to a Puerto Rican.

In 1941, FDR named South Carolina Sen. “Jimmy” Byrnes to the Supreme Court. Byrnes had led filibusters in 1935 and 1938 that killed anti-lynching bills, arguing that lynching was necessary “to hold in check the Negro in the South.”

FDR refused to back the 1938 anti-lynching law.

“This is a white man’s country and will always remain a white man’s country,” said Jimmy. Harry Truman, who paid $10 to join the Klan, then quit, named Byrnes Secretary of State, putting him first in line of succession to the presidency, as Harry then had no V.P.

During the civil rights struggles of the ‘50s and ‘60s, Gov. Orval Faubus used the National Guard to keep black students out of Little Rock High. Gov. Ross Barnett refused to let James Meredith into Ole Miss. Gov. George Wallace stood in the door at the University of Alabama, to block two black students from entering.

All three governors were Democrats. All acted in accord with the “Dixie Manifesto” of 1956, which was signed by 19 senators, all Democrats, and 80 Democratic congressmen.

Among the signers of the manifesto, which called for massive resistance to the Brown decision desegregating public schools, was the vice presidential nominee on Adlai’s Stevenson’s ticket in 1952, Sen. John Sparkman of Alabama.

Though crushed by Eisenhower, Adlai swept the Deep South, winning both Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas.

Do you suppose those Southerners thought Adlai would be tougher than Ike on Stalin? Or did they think Adlai would maintain the unholy alliance of Southern segregationists and Northern liberals that enabled Democrats to rule from 1932 to 1952?

The Democratic Party was the party of slavery, secession and segregation, of “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman and the KKK. “Bull” Connor, who turned the dogs loose on black demonstrators in Birmingham, was the Democratic National Committeeman from Alabama.

And Nixon?

In 1956, as vice president, Nixon went to Harlem to declare, “America can’t afford the cost of segregation.” The following year, Nixon got a personal letter from Dr. King thanking him for helping to persuade the Senate to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

Nixon supported the civil rights acts of 1964, 1965 and 1968.

In the 1966 campaign, as related in my new book “The Greatest Comeback: How Richard Nixon Rose From Defeat to Create the New Majority,” out July 8, Nixon blasted Dixiecrats “seeking to squeeze the last ounces of political juice out of the rotting fruit of racial injustice.”

Nixon called out segregationist candidates in ‘66 and called on LBJ, Hubert Humphrey and Bobby Kennedy to join him in repudiating them. None did. Hubert, an arm around Lester Maddox, called him a “good Democrat.” And so were they all – good Democrats.

While Adlai chose Sparkman, Nixon chose Spiro Agnew, the first governor south of the Mason Dixon Line to enact an open-housing law.

In Nixon’s presidency, the civil rights enforcement budget rose 800 percent. Record numbers of blacks were appointed to federal office. An Office of Minority Business Enterprise was created. SBA loans to minorities soared 1,000 percent. Aid to black colleges doubled.

Nixon won the South not because he agreed with them on civil rights – he never did – but because he shared the patriotic values of the South and its antipathy to liberal hypocrisy.

When Johnson left office, 10 percent of Southern schools were desegregated.

When Nixon left, the figure was 70 percent. Richard Nixon desegregated the Southern schools, something you won’t learn in today’s public schools.

Not done there yet, snowflake.

1964:George Romney, Republican civil rights activist. That Republicans have let Democrats get away with this mountebankery is a symptom of their political fecklessness, and in letting them get away with it the GOP has allowed itself to be cut off rhetorically from a pantheon of Republican political heroes, from Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass to Susan B. Anthony, who represent an expression of conservative ideals as true and relevant today as it was in the 19th century.

Perhaps even worse, the Democrats have been allowed to rhetorically bury their Bull Connors, their longstanding affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan, and their pitiless opposition to practically every major piece of civil-rights legislation for a century.

Republicans may not be able to make significant inroads among black voters in the coming elections, but they would do well to demolish this myth nonetheless.

Even if the Republicans’ rise in the South had happened suddenly in the 1960s (it didn’t) and even if there were no competing explanation (there is), racism — or, more precisely, white southern resentment over the political successes of the civil-rights movement — would be an implausible explanation for the dissolution of the Democratic bloc in the old Confederacy and the emergence of a Republican stronghold there.

That is because those southerners who defected from the Democratic Party in the 1960s and thereafter did so to join a Republican Party that was far more enlightened on racial issues than were the Democrats of the era, and had been for a century.

There is no radical break in the Republicans’ civil-rights history: From abolition to Reconstruction to the anti-lynching laws, from the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, and 1964, there exists a line that is by no means perfectly straight or unwavering but that nonetheless connects the politics of Lincoln with those of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

And from slavery and secession to remorseless opposition to everything from Reconstruction to the anti-lynching laws, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, there exists a similarly identifiable line connecting John Calhoun and Lyndon Baines Johnson.

Supporting civil-rights reform was not a radical turnaround for congressional Republicans in 1964, but it was a radical turnaround for Johnson and the Democrats.

The depth of Johnson’s prior opposition to civil-rights reform must be digested in some detail to be properly appreciated.

In the House, he did not represent a particularly segregationist constituency (it “made up for being less intensely segregationist than the rest of the South by being more intensely anti-Communist,” as the New York Times put it), but Johnson was practically antebellum in his views.

Never mind civil rights or voting rights: In Congress, Johnson had consistently and repeatedly voted against legislation to protect black Americans from lynching.

As a leader in the Senate, Johnson did his best to cripple the Civil Rights Act of 1957; not having votes sufficient to stop it, he managed to reduce it to an act of mere symbolism by excising the enforcement provisions before sending it to the desk of President Eisenhower.

Johnson’s Democratic colleague Strom Thurmond nonetheless went to the trouble of staging the longest filibuster in history up to that point, speaking for 24 hours in a futile attempt to block the bill.

The reformers came back in 1960 with an act to remedy the deficiencies of the 1957 act, and Johnson’s Senate Democrats again staged a record-setting filibuster.

In both cases, the “master of the Senate” petitioned the northeastern Kennedy liberals to credit him for having seen to the law’s passage while at the same time boasting to southern Democrats that he had taken the teeth out of the legislation.

Johnson would later explain his thinking thus: “These Negroes, they’re getting pretty uppity these days, and that’s a problem for us, since they’ve got something now they never had before: the political pull to back up their uppityness. Now we’ve got to do something about this — we’ve got to give them a little something, just enough to quiet them down, not enough to make a difference.”

Johnson did not spring up from the Democratic soil ex nihilo.

Not one Democrat in Congress voted for the Fourteenth Amendment.

Not one Democrat in Congress voted for the Fifteenth Amendment.

Not one voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Dwight Eisenhower as a general began the process of desegregating the military, and Truman as president formalized it, but the main reason either had to act was that President Woodrow Wilson, the personification of Democratic progressivism, had resegregated previously integrated federal facilities. (“If the colored people made a mistake in voting for me, they ought to correct it,” he declared.)

Klansmen from Senator Robert Byrd to Justice Hugo Black held prominent positions in the Democratic Party — and President Wilson chose the Klan epic Birth of a Nation to be the first film ever shown at the White House.

Johnson himself denounced an earlier attempt at civil-rights reform as the “nigger bill.” So what happened in 1964 to change Democrats’ minds? In fact, nothing.

President Johnson was nothing if not shrewd, and he knew something that very few popular political commentators appreciate today: The Democrats began losing the “solid South” in the late 1930s — at the same time as they were picking up votes from northern blacks.

The Civil War and the sting of Reconstruction had indeed produced a political monopoly for southern Democrats that lasted for decades, but the New Deal had been polarizing. It was very popular in much of the country, including much of the South — Johnson owed his election to the House to his New Deal platform and Roosevelt connections — but there was a conservative backlash against it, and that backlash eventually drove New Deal critics to the Republican Party.

Likewise, adherents of the isolationist tendency in American politics, which is never very far from the surface, looked askance at what Bob Dole would later famously call “Democrat wars” (a factor that would become especially relevant when the Democrats under Kennedy and Johnson committed the United States to a very divisive war in Vietnam).

The tiniest cracks in the Democrats’ southern bloc began to appear with the backlash to FDR’s court-packing scheme and the recession of 1937.

Republicans would pick up 81 House seats in the 1938 election, with West Virginia’s all-Democrat delegation ceasing to be so with the acquisition of its first Republican.

Kentucky elected a Republican House member in 1934, as did Missouri, while Tennessee’s first Republican House member, elected in 1918, was joined by another in 1932.

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the Republican Party, though marginal, began to take hold in the South — but not very quickly: Dixie would not send its first Republican to the Senate until 1961, with Texas’s election of John Tower.

At the same time, Republicans went through a long dry spell on civil-rights progress.

Many of them believed, wrongly, that the issue had been more or less resolved by the constitutional amendments that had been enacted to ensure the full citizenship of black Americans after the Civil War, and that the enduring marginalization of black citizens, particularly in the Democratic states, was a problem that would be healed by time, economic development, and organic social change rather than through a second political confrontation between North and South.

As late as 1964, the Republican platform argued that “the elimination of any such discrimination is a matter of heart, conscience, and education, as well as of equal rights under law.”

The conventional Republican wisdom of the day held that the South was backward because it was poor rather than poor because it was backward.

And their strongest piece of evidence for that belief was that Republican support in the South was not among poor whites or the old elites — the two groups that tended to hold the most retrograde beliefs on race.

Instead, it was among the emerging southern middle class.

This fact was recently documented by professors Byron Shafer and Richard Johnston in The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (Harvard University Press, 2006).

Which is to say: The Republican rise in the South was contemporaneous with the decline of race as the most important political question and tracked the rise of middle-class voters moved mainly by economic considerations and anti-Communism.

The South had been in effect a Third World country within the United States, and that changed with the post-war economic boom.

As Clay Risen put it in the New York Times: “The South transformed itself from a backward region to an engine of the national economy, giving rise to a sizable new wealthy suburban class.

This class, not surprisingly, began to vote for the party that best represented its economic interests: the GOP. Working-class whites, however — and here’s the surprise — even those in areas with large black populations, stayed loyal to the Democrats.

This was true until the 90s, when the nation as a whole turned rightward in Congressional voting.” The mythmakers would have you believe that it was the opposite: that your white-hooded hillbilly trailer-dwelling tornado-bait voters jumped ship because LBJ signed a civil-rights bill (passed on the strength of disproportionately Republican support in Congress). The facts suggest otherwise. There is no question that Republicans in the 1960s and thereafter hoped to pick up the angry populists who had delivered several states to Wallace.

That was Patrick J. Buchanan’s portfolio in the Nixon campaign.

But in the main they did not do so by appeal to racial resentment, direct or indirect.

The conservative ascendency of 1964 saw the nomination of Barry Goldwater, a western libertarian who had never been strongly identified with racial issues one way or the other, but who was a principled critic of the 1964 act and its extension of federal power.

Goldwater had supported the 1957 and 1960 acts but believed that Title II and Title VII of the 1964 bill were unconstitutional, based in part on a 75-page brief from Robert Bork.

But far from extending a welcoming hand to southern segregationists, he named as his running mate a New York representative, William E. Miller, who had been the co-author of Republican civil-rights legislation in the 1950s.

The Republican platform in 1964 was hardly catnip for Klansmen: It spoke of the Johnson administration’s failure to help further the “just aspirations of the minority groups” and blasted the president for his refusal “to apply Republican-initiated retraining programs where most needed, particularly where they could afford new economic opportunities to Negro citizens.”

Other planks in the platform included: “improvements of civil rights statutes adequate to changing needs of our times; such additional administrative or legislative actions as may be required to end the denial, for whatever unlawful reason, of the right to vote; continued opposition to discrimination based on race, creed, national origin or sex.”

And Goldwater’s fellow Republicans ran on a 1964 platform demanding “full implementation and faithful execution of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and all other civil rights statutes, to assure equal rights and opportunities guaranteed by the Constitution to every citizen.” Some dog whistle.

Of course there were racists in the Republican Party. There were racists in the Democratic Party. The case of Johnson is well documented, while Nixon had his fantastical panoply of racial obsessions, touching blacks, Jews, Italians (“Don’t have their heads screwed on”), Irish (“They get mean when they drink”), and the Ivy League WASPs he hated so passionately (“Did one of those dirty bastards ever invite me to his f***ing men’s club or goddamn country club? Not once”).

But the legislative record, the evolution of the electorate, the party platforms, the keynote speeches — none of them suggests a party-wide Republican about-face on civil rights.

Neither does the history of the black vote.

While Republican affiliation was beginning to grow in the South in the late 1930s, the GOP also lost its lock on black voters in the North, among whom the New Deal was extraordinarily popular.

By 1940, Democrats for the first time won a majority of black votes in the North. This development was not lost on Lyndon Johnson, who crafted his Great Society with the goal of exploiting widespread dependency for the benefit of the Democratic Party.

Unlike the New Deal, a flawed program that at least had the excuse of relying upon ideas that were at the time largely untested and enacted in the face of a worldwide economic emergency, Johnson’s Great Society was pure politics.

Johnson’s War on Poverty was declared at a time when poverty had been declining for decades, and the first Job Corps office opened when the unemployment rate was less than 5 percent.

Congressional Republicans had long supported a program to assist the indigent elderly, but the Democrats insisted that the program cover all of the elderly — even though they were, then as now, the most affluent demographic, with 85 percent of them in households of above-average wealth.

Democrats such as Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Anthony J. Celebrezze argued that the Great Society would end “dependency” among the elderly and the poor, but the programs were transparently designed merely to transfer dependency from private and local sources of support to federal agencies created and overseen by Johnson and his political heirs.

In the context of the rest of his program, Johnson’s unexpected civil-rights conversion looks less like an attempt to empower blacks and more like an attempt to make clients of them.

If the parties had in some meaningful way flipped on civil rights, one would expect that to show up in the electoral results in the years following the Democrats’ 1964 about-face on the issue.

Nothing of the sort happened: Of the 21 Democratic senators who opposed the 1964 act, only one would ever change parties.

Nor did the segregationist constituencies that elected these Democrats throw them out in favor of Republicans: The remaining 20 continued to be elected as Democrats or were replaced by Democrats.

It was, on average, nearly a quarter of a century before those seats went Republican. If southern rednecks ditched the Democrats because of a civil-rights law passed in 1964, it is strange that they waited until the late 1980s and early 1990s to do so. They say things move slower in the South — but not that slow.

Republicans did begin to win some southern House seats, and in many cases segregationist Democrats were thrown out by southern voters in favor of civil-rights Republicans.

One of the loudest Democratic segregationists in the House was Texas’s John Dowdy.

Dowdy was a bitter and buffoonish opponent of the 1964 reforms.

He declared the reforms “would set up a despot in the attorney general’s office with a large corps of enforcers under him; and his will and his oppressive action would be brought to bear upon citizens, just as Hitler’s minions coerced and subjugated the German people.

Dowdy went on: “I would say this — I believe this would be agreed to by most people: that, if we had a Hitler in the United States, the first thing he would want would be a bill of this nature.” (Who says political rhetoric has been debased in the past 40 years?)

Dowdy was thrown out in 1966 in favor of a Republican with a very respectable record on civil rights, a little-known figure by the name of George H. W. Bush.

It was in fact not until 1995 that Republicans represented a majority of the southern congressional delegation — and they had hardly spent the Reagan years campaigning on the resurrection of Jim Crow.

It was not the Civil War but the Cold War that shaped midcentury partisan politics.

Eisenhower warned the country against the “military-industrial complex,” but in truth Ike’s ascent had represented the decisive victory of the interventionist, hawkish wing of the Republican Party over what remained of the America First/Charles Lindbergh/Robert Taft tendency.

The Republican Party had long been staunchly anti-Communist, but the post-war era saw that anti-Communism energized and looking for monsters to slay, both abroad — in the form of the Soviet Union and its satellites — and at home, in the form of the growing welfare state, the “creeping socialism” conservatives dreaded.

By the middle 1960s, the semi-revolutionary Left was the liveliest current in U.S. politics, and Republicans’ unapologetic anti-Communism — especially conservatives’ rhetoric connecting international socialism abroad with the welfare state at home — left the Left with nowhere to go but the Democratic Party. Vietnam was Johnson’s war, but by 1968 the Democratic Party was not his alone.

The schizophrenic presidential election of that year set the stage for the subsequent transformation of southern politics: Segregationist Democrat George Wallace, running as an independent, made a last stand in the old Confederacy but carried only five states.

Republican Richard Nixon, who had helped shepherd the 1957 Civil Rights Act through Congress, counted a number of Confederate states (North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, and Tennessee) among the 32 he carried.

Democrat Hubert Humphrey was reduced to a northern fringe plus Texas.

Mindful of the long-term realignment already under way in the South, Johnson informed Democrats worried about losing it after the 1964 act that “those states may be lost anyway.”

Subsequent presidential elections bore him out: Nixon won a 49-state sweep in 1972, and, with the exception of the post-Watergate election of 1976, Republicans in the following presidential elections would more or less occupy the South like Sherman.

Bill Clinton would pick up a handful of southern states in his two contests, and Barack Obama had some success in the post-southern South, notably Virginia and Florida.

The Republican ascendancy in Dixie is associated with several factors: The rise of the southern middle class, The increasingly trenchant conservative critique of Communism and the welfare state, The Vietnam controversy, The rise of the counterculture, law-and-order concerns rooted in the urban chaos that ran rampant from the late 1960s to the late 1980s, and The incorporation of the radical Left into the Democratic party.

Individual events, especially the freak show that was the 1968 Democratic convention, helped solidify conservatives’ affiliation with the Republican Party. Democrats might argue that some of these concerns — especially welfare and crime — are “dog whistles” or “code” for race and racism. However, this criticism is shallow in light of the evidence and the real saliency of those issues among U.S. voters of all backgrounds and both parties for decades. Indeed, Democrats who argue that the best policies for black Americans are those that are soft on crime and generous with welfare are engaged in much the same sort of cynical racial calculation President Johnson was practicing. Johnson informed skeptical southern governors that his plan for the Great Society was “to have them niggers voting Democratic for the next two hundred years.” Johnson’s crude racism is, happily, largely a relic of the past, but his strategy endures.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 2.27 (before 1940)

380 – Edict of Thessalonica: Emperor Theodosius I and his co-emperors Gratian and Valentinian II declare their wish that all Roman citizens convert to Nicene Christianity.

425 – The University of Constantinople is founded by Emperor Theodosius II at the urging of his wife Aelia Eudocia.

907 – Abaoji, chieftain of the Yila tribe, is named khagan of the Khitans.

1560 – The Treaty of Berwick is signed by England and the Lords of the Congregation of Scotland, establishing the terms under which English armed forces were to be permitted in Scotland in order to expel occupying French troops.

1594 – Henry IV is crowned King of France.

1617 – Sweden and the Tsardom of Russia sign the Treaty of Stolbovo, ending the Ingrian War and shutting Russia out of the Baltic Sea.

1626 – Yuan Chonghuan is appointed Governor of Liaodong, after leading the Chinese into a great victory against the Manchurians under Nurhaci.

1776 – American Revolutionary War: The Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge in North Carolina breaks up a Loyalist militia.

1782 – American Revolutionary War: The House of Commons of Great Britain votes against further war in America.

1801 – Pursuant to the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801, Washington, D.C. is placed under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Congress.

1809 – Action of 27 February 1809: Captain Bernard Dubourdieu captures HMS Proserpine.

1812 – Argentine War of Independence: Manuel Belgrano raises the Flag of Argentina in the city of Rosario for the first time.

1812 – Poet Lord Byron gives his first address as a member of the House of Lords, in defense of Luddite violence against Industrialism in his home county of Nottinghamshire.

1844 – The Dominican Republic gains independence from Haiti.

1860 – Abraham Lincoln makes a speech at Cooper Union in the city of New York that is largely responsible for his election to the Presidency.

1864 – American Civil War: The first Northern prisoners arrive at the Confederate prison at Andersonville, Georgia.

1870 – The current flag of Japan is first adopted as the national flag for Japanese merchant ships.

1881 – First Boer War: The Battle of Majuba Hill takes place.

1898 – King George I of Greece survives an assassination attempt.

1900 – Second Boer War: In South Africa, British military leaders receive an unconditional notice of surrender from Boer General Piet Cronjé at the Battle of Paardeberg.

1900 – The British Labour Party is founded.

1900 – Fußball-Club Bayern München is founded.

1902 – Second Boer War: Australian soldiers Harry "Breaker" Morant and Peter Handcock are executed in Pretoria after being convicted of war crimes.

1916 – Ocean liner SS Maloja strikes a mine near Dover and sinks with the loss of 155 lives.

1921 – The International Working Union of Socialist Parties is founded in Vienna.

1922 – A challenge to the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, allowing women the right to vote, is rebuffed by the Supreme Court of the United States in Leser v. Garnett.

1932 – The Mäntsälä rebellion begins when members of the far-right Lapua Movement start shooting at the social democrats' event in Mäntsälä, Finland.

1933 – Reichstag fire: Germany's parliament building in Berlin, the Reichstag, is set on fire; Marinus van der Lubbe, a young Dutch Communist claims responsibility.

1939 – United States labor law: The U.S. Supreme Court rules in NLRB v. Fansteel Metallurgical Corp. that the National Labor Relations Board has no authority to force an employer to rehire workers who engage in sit-down strikes.

0 notes

Photo

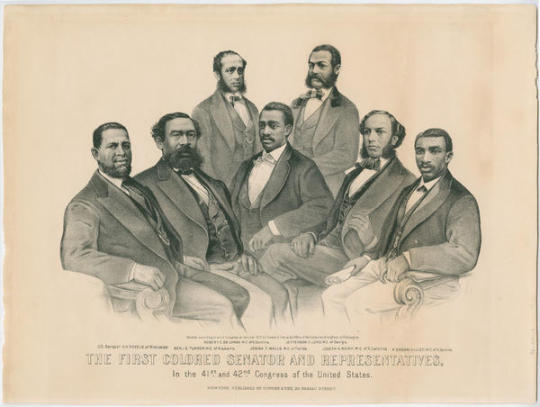

Soon, Reverend Raphael Warnock will make history as Georgia's first African American U.S. Senator and one of 10 African Americans who have served in the Senate. The first was Hiram Revels, a Mississippi Republican who took office in 1870 and is depicted in the far left of this lithograph with several other Black congressmen.

In the years following the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, a number of African Americans were elected to legislative positions and governorships, particularly in the South. However, the progress of Reconstruction was quickly undone by white supremacist violence and the codification of Jim Crow laws.

While the lithograph appears to be a group portrait, it's likely that the artist created a composite image of the men based on photographs taken by Levin C. Handy and his uncle, the well-known Civil War photographer Matthew Brady.

1st image: Currier & Ives, The first colored senator and representatives in the 41st and 42nd Congress of the United States, ca. 1872. Lithograph.

2nd image: Hiram R. Revels of Miss., ca. 1860 - ca. 1875. Wet collodion negative. From the Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

#LCPprints#BlackHistory#BensLibrary#SpecialCollections#librariesofinstagram#iglibraries#georgiarunoffs

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading about various travesties the English Government did in the 1700's to 1800's is just a long list of rich white men looking at poor people and going "fuck them in particular."

On chapter 4 of This Golden Fleece, which is about the Highland's of Scotland, so of course we're talking Tartan, Kilts, and Stockings.

Tartan didn't really exist until the 16th century. There evidence of kilts going back to Roman time, and patterned cloth was worn. But tartan as a thing is more recent than that. The patterns associated with clans didn't come about till the 19th century, in partially mixed with the military because for a long time they were the only ones permitted to wear it.

But one can't talk about the Highland's without talking about how they've been shafted. This was briefly talked about in chapter 2, the Gansey sweater, and about the Highland clearance.

So I'm reading and my brain starts wandering and I get distracted by Wikipedia and a thought process. Here's a time line. 1740's traditional Highland clothing is regulated by parliament, outlawing tartan and short kilts and things like that, except for use by military. 1750's to 1860's is when the Highland clearance takes place. 1870's is when the commons land act passes meaning land in England and Wales was not available for people any more and people had to basically get jobs. They couldn't use the land any more because it belonged to someone. This is very similar to what was going on up north except instead of buying out large swaths of land Parliament just went "not yours now." This is a key point in the creation of capitalism cause people who had previously made a living off commons land could no longer do this so in order to survive they had to sell their labour to other people and earn a wage to pay for loving expenses.

There was a lot of talk about when women got the vote in the UK a few years back as we came up to the centenary, but that was also a landmark for men because before that point the only about 60% of men were allowed to vote. But even that wasn't that long. In 1867 there was a reform act, which was later updated in 1884. Before that it is estimated that out of the entire country only 1 million men had the right to vote. The population of the UK on the census between 1851-1861 was 27,368,800, which is about 0.37% of the population consisting of only 1 demographic, not even getting in to the fact much of the elections at the time consisted of there is one candidate, it's the lord's son, and we're going to watch you vote to make sure you vote for him.

Idk what I'm getting at. I guess in part we don't realise how fucking lucky we are right now? How I'm not surprised these atrocities happened when the people incharge, and the method of picking the people incharge, were such horseshit? Capitalism has always been about hating poor people? The rich remain The Fucking Worst? Idk. It's half 1 in the morning. I just want to read about knitting damn it and I'm contemplating the fact capitalism is basically based in the decision to destroy.

I should go to bed.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Acknowledging the wrongs Antioch’s early residents inflicted against Chinese Americans, Mayor Lamar Thorpe on Wednesday apologized for that and introduced a series of proposals to make amends.

The City Council on Tuesday adopted a proclamation Thorpe introduced condemning the current violence and hate against the Asian American and Pacific Islander community. He signed the proclamation and presented it the next day to Contra Costa County’s only Asian American elected official, Andy Li, president of the Contra Costa Community College District.

Li also cited Chinese American contributions to the region, such as building the railroad and San Joaquin/Sacramento Delta levees in the 1860s and 1870s.

“It was a great contribution to the community and they were treated badly,” he said, referring to the 1863 Chinese Exclusion Act that prohibited the immigration of Chinese laborers after they had helped build the communities.

when the palace hotel was torn down in 1926, workers found secret tunnels underground that chinese residents use to commute after sunset. chinese residents were not allowed to be on the street after dark. (antioch historical society & museum)

“To remember the past, the mayor said he wants to the city to designate a Chinatown historic district with historical markers and fund a permanent exhibit at the Antioch Historical Museum, as well as a community mural. He also will ask the city to officially apologize for the terrorizing of Chinese immigrants in its early years, Thorpe said.

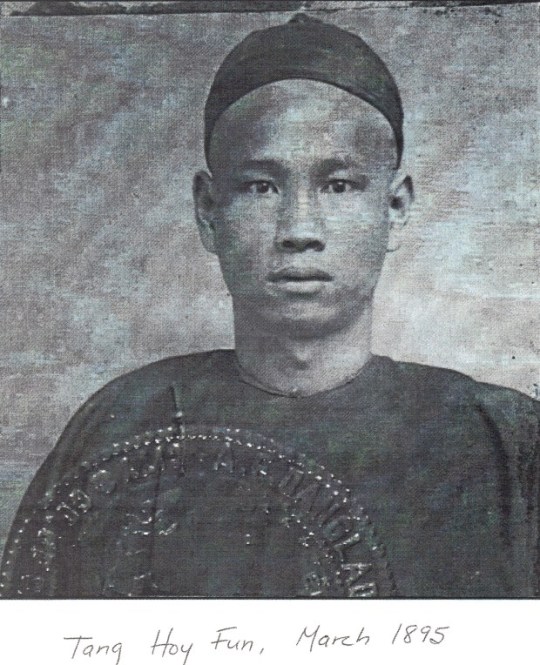

tang hoy fun, pictured in 1895, was a well-known for his work at the hop sing laundry in downtown antioch. (courtesy antioch historical society)

“Very little was recorded about the city’s historic Chinese community, whose population was estimated to number in the hundreds in the late 1800s. A section of Antioch—one of the state’s oldest communities—was called Chinatown and included Chinese American homes and businesses on both sides of Second Street and on First Street from G to I streets.

Chinese immigrants helped build the levees and railroads and worked in the coal mines and on farms for low wages, disliked by non-Asians who thought they were taking away their jobs.

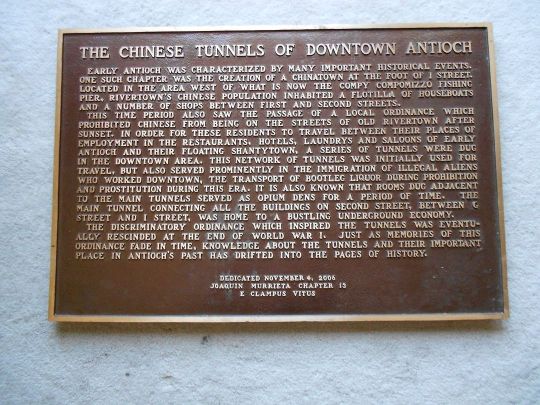

the joaquin murietta chapter 15 of the e clampus vitus installed a plaque remembering the chinese contributions and the old tunnels that once ran underground in antioch in 2006. the plaque has since disappeared.

“In the city’s early days, people of Chinese descent were banned from walking Antioch’s streets after sunset, so they built underground tunnels to move around and socialize. In 1876 an angry white mob forced the Chinese Americans from Antioch and later burned down its Chinatown, according to early newspaper accounts. Some eventually would return to do business and work in the canneries.

“Under this building right here, there are tunnels where we marginalized our Chinese brothers and sisters,” Thorpe said. “During the 19th century, anti-Chinese sentiment resulted in conflict and extremely restrictive regulations and norms concerning where Asian-Americans could live and in which occupations they could work, which is often enforced by violence.””

read more: eastbaytimes, 14.04.21.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The intelligent W.E.B. Du Bois

“William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American civil rights activist, leader, Pan-Africanist, sociologist, educator, historian, writer, editor, poet, and scholar. He was born and raised in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. He had two children with his wife, Nina Gomer. He became a naturalized citizen of Ghana in 1963 at the age of 95 – the year of his death.

As Activist

In 1905, Du Bois was a founder and general secretary of the Niagara Movement, an African American protest group of scholars and professionals. Du Bois founded and edited the Moon (1906) and the Horizon (1907-1910) as organs for the Niagara Movement.

In 1909, Du Bois was among the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and from 1910 to 1934 served it as director of publicity and research, a member of the board of directors, and founder and editor of The Crisis, its monthly magazine.

In The Crisis, Du Bois directed a constant stream of agitation–often bitter and sarcastic–at white Americans while serving as a source of information and pride to African Americans. The magazine always published young African American writers. Racial protest during the decade following World War I focused on securing anti-lynching legislation. During this period the NAACP was the leading protest organization and Du Bois its leading figure.

In 1934, Du Bois resigned from the NAACP board and from The Crisis because of his new advocacy of an African American nationalist strategy that ran in opposition to the NAACP’s commitment to integration. However, he returned to the NAACP as director of special research from 1944 to 1948. During this period, he was active in placing the grievances of African Americans before the United Nations, serving as a consultant to the UN founding convention (1945) and writing the famous “An Appeal to the World” (1947).

Du Bois identified as a socialist and belonged to the Socialist Party from 1910 to 1912.

As Scholar

Du Bois’s life and work were an inseparable mixture of scholarship, protest activity, and polemics. All of his efforts were geared toward gaining equal treatment for black people in a world dominated by whites and toward marshaling and presenting evidence to refute the myths of racial inferiority.

From his earliest years, Du Bois was a prolific, gifted scholar. In 1884, Du Bois graduated from high school as valedictorian. He received his Bachelor of Arts from Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn., in 1888, having spent summers teaching in African American schools in Nashville’s rural areas. In 1888 he entered Harvard University as a junior, took a bachelor of arts cum laude in 1890, and was one of six commencement speakers. From 1892 to 1894 he pursued graduate studies in history and economics at the University of Berlin on a Slater Fund fellowship. He served for 2 years as professor of Greek and Latin at Wilberforce University in Ohio.

Du Bois received his Master of Arts from Harvard in 1891, and, in 1895, he became the first African American to receive a doctorate from the university. His dissertation, “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870,” was published as No. 1 in Harvard Historical Series.

In 1896-1897, Du Bois became assistant instructor in sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. There he conducted the pioneering sociological study of an urban community, published as The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study (1899). These first two works assured Du Bois’s place among America’s leading scholars.

From 1897 to 1910 Du Bois served as professor of economics and history at Atlanta University, where he organized conferences titled the Atlanta University Studies of the Negro Problem and edited or co-edited 16 of the annual publications, on such topics as The Negro in Business (1899), The Negro Artisan (1902), The Negro Church (1903), Economic Cooperation among Negro Americans (1907), and The Negro American Family (1908). Other significant publications were The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches (1903), one of the outstanding collections of essays in American letters, and John Brown (1909), a sympathetic portrayal published in the American Crisis Biographies series.

Du Bois also wrote two novels, The Quest of the Silver Fleece (1911) and Dark Princess: A Romance (1928); a book of essays and poetry, Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil (1920); and two histories of black people, The Negro (1915) and The Gift of Black Folk: Negroes in the Making of America (1924).

From 1934 to 1944 Du Bois was chairman of the department of sociology at Atlanta University. In 1940 he founded Phylon, a social science quarterly. Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 (1935), perhaps his most significant historical work, details the role of African Americans in American society, specifically during the Reconstruction period. The book was criticized for its use of Marxist concepts and for its attacks on the racist character of much of American historiography. However, it remains the best single source on its subject.

Black Folk, Then and Now (1939) is an elaboration of the history of black people in Africa and the New World. Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace (1945) is a brief call for the granting of independence to Africans, and The World and Africa: An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa Has Played in World History (1947; enlarged ed. 1965) is a major work anticipating many later scholarly conclusions regarding the significance and complexity of African history and culture. A trilogy of novels, collectively entitled The Black Flame (1957, 1959, 1961), and a selection of his writings, An ABC of Color (1963), are also worthy.

Du Bois received many honorary degrees, was a fellow and life member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He was the outstanding African American intellectual of his period in America.

As Global Citizen

In 1948, he was cochairman of the Council on African Affairs; in 1949 he attended the New York, Paris, and Moscow peace congresses; in 1950 he served as chairman of the Peace Information Center and ran for the U.S. Senate on the American Labor party ticket in New York. In 1950-1951, Du Bois was tried and acquitted as an agent of a foreign power in one of the most ludicrous actions ever taken by the American government. Du Bois traveled widely throughout Russia and China in 1958-1959 and in 1961 joined the Communist party of the United States. He also took up residence in Ghana, Africa, in 1961.

Du Bois was also active in behalf of Pan-Africanism and concerned with the conditions of people of African descent wherever they lived. In 1900 he attended the First Pan-African Conference held in London, was elected a vice president, and wrote the “Address to the Nations of the World.” The Niagara Movement included a “pan-African department.” In 1911 Du Bois attended the First Universal Races Congress in London along with black intellectuals from Africa and the West Indies.

Du Bois organized a series of Pan-African congresses around the world, in 1919, 1921, 1923, and 1927. The delegations comprised intellectuals from Africa, the West Indies, and the United States. Though resolutions condemning colonialism and calling for alleviation of the oppression of Africans were passed, little concrete action was taken. The Fifth Congress (1945, Manchester, England) elected Du Bois as chairman, but the power was clearly in the hands of younger activists, such as George Padmore and Kwame Nkrumah, who later became significant in the independence movements of their respective countries. Du Bois’s final Pan-African gesture was to take up citizenship in Ghana in 1961 at the request of President Kwame Nkrumah and to begin work as director of the Encyclopedia Africana.

Du Bois died in Ghana on Aug. 27, 1963, on the eve of the civil rights march in Washington, D.C. He was given a state funeral, at which Kwame Nkrumah remarked that he was “a phenomenon.”” (source)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wherefore art thou, Compromise?

Where is America's ability to compromise? Why can't American politicians compromise?

We couldn't compromise in the 1860's, and that's good because certain things do not allow for compromise - morals and ethics, for starters. The Civil War creeped up then, delivering a win to the forces of equality and the American Dream, something that until recently we took for granted - that anyone in America could be anything, even a Black man a president, which we learned in 2012 and quickly declared victory for the United States despite the fact that compromise in America had already shown itself to be near its end.

And with Trump, Republicans dealt a potentially fatal blow to the concept of compromise, the idea that we could work together to build a shared future and an ongoing conversation between human beings would push us forward with only a few bumps and bruises along the way.

The problem is that we can't compromise, and there are a lot of forces in play that are the reason why everyday adults can no longer just get along. in no particular order, those forces are...

Right-wing media

Money

Conspiracy Theories

Term Limits

Right-wing Media has been a growing concern for some time now - at least a solid two decades. It started with an effort to give the greater Conservative world a voice (and for Rupert Murdoch to make some giant money), and that's what it did. Only with Fox News, the Right got more than some news leaning its way, it got a full-on not-really-news, more-like-infotainment piece (that even a court judge admitted a few weeks ago). Fox News was more like opinion, more talk radio than news, although they threw some news in there to make it look good. Add in talk radio itself, and all of its bullshit -- all of this reaching back to the 90's, and you get what's essentially a powerful propaganda machine. Plus one equals Trump, who full advantage of the growing insanity to push right-wing media over the edge with full-on conspiracy theories. And here we are, right-wing politicans who advocate for some of these conspiracy theories getting elected to Congress in Georgia. A US President that shapes public opinion with conspiracy theories, demonizes anyone who opposes him, and has essentially given birth to an entire movement of alternate reality from the Oval Office via Twitter.

There's no compromising with people who aren't even lucid. And these conspiracy quacks are definitely not looking for ways to compromise and govern together. They are busy uncovering plots of Venezuelan leftists to destroy the Trump empire, unearthing chiild molester cabals in the basements of pizza parlors and declaring Biden a Chinese agent and pedophile. Compromise is suicide for these fools because they've already shown themselves unwilling to even embrace reality. It's rather like arguing with a 5-year old over who spilled the water on the floor. "It was the dog." "The dog is outside." "It was Nana." "Nana died last year." "It was an earthquake." "Nope." "It was aliens." "Hmmm." Just ask the yahoos at QAnon, or the History Channel, it was definitely aliens. The Lizard People. Or maybe it's just the Commies and the Socialists - just ask Rush Limbaugh; he's been repeating white supremacy talking points from the 1870s for decades.

But really, what's the point of all this? Why does any of this bullshit even get anywhere? Simple answer: $$$$$$. Money.

It's all about money. That's all. It's all money. Money answers every question. Why did Trump run for President? Money.Why did QAnon appear on the scene and spread their insanity? Money.Why did Rush Limbaugh get the Presidential Medal of Freedom? He generates support for American Conservative through extremist right-wing propaganda, which in turns generates money - campaign donations is huge money.Why are Republicans supporting the Mad King Trump? Money. Money and power.Why are Fox News personalities willing to say anything on TV? Money.

Everything comes down to money. And a few years ago, the money faucet was turned (possibly) permanently open thanks to Citizens United. Now the money flows from everywhere, and there's little effort to control it, regulate it, track it and see who's giving it. Billionaires and millionaires and moms and pops are sending in cash. The rich send it in to ensure that policies favor them, so they can make more money. The average person sends in money because they've bought into fear politics over the last 2-3 decades of being clued to the Big Lie Machine, like Fox News or now OANN, the new Trump-loving propaganda producer. And with limited rules on how this money is handled or used, much less audited and regulated, we have all these people with big, fat, happy flush funds for lavish dinners and golf trips and 3rd yachts. Now rich people can buy their way into an ambassadorship or a Cabinet position, which generates them even more money because being rich isn't about producing anything, it's about making connections, and connection mean money. Politicians need money for campaigns so they can work on policies that in-turn benefit their benefactors and make them more money, which opens doors for all to....you guessed it, more money.

The propaganda machine delivers the money, and the monied voices reflect the propaganda machine. And when there's as much money as you need to stay in the driver's seat, what the American people want doesn't matter. Because you don't need to convince the Average Joe on the Right to vote for you because the propaganda machine has convinced Joe that the other guy is going to kill your family and give your house and daughter to an illegal immigrant. So, Joe's money and votes are coming your way, even if you murder Joe's wife in the parking lot. It's a machine that grinds people up and spits them out, creates trolls and proles, and all the money lines the pockets of the rich and the representatives of the rich, aka politicians.

And that leads us to our last piece, perhaps the most important one. Term limits.

What we've seen is a perpetual cycle of lies and money, which likely can't be broken because the Supreme Court validated it once and now SCOTUS is owned by the alt-Right for a generation (unless Congress impeaches some judges, which may or may not be possible, or the United States puts service limits on federal judges and SCOTUS, like it should - but that's another discussion). Now we have one way out of this - that I see, and it's in term limits for all federally-elected officials. No more 7-term Senators. No more 10-term Congresspersons. No more Mitch McConnell's and Nancy Pelosi's. You gotta go. Do your 2 terms and get lost. Sure, you can be in Congress two terms and then go to the Senate for two, but that's it. Two terms, then let's get some fresh meat and fresh ideas in there. (Same concept as above with the judiciary at the federal and SCOTUS level.) You do some time in public service, and then you get out and let someone else play. It's one way to ensure that there's some competition, which could lead people to having to prove themselves and sell themselves to the public, based on ideas rather than team. As long as a Senator can just run on name recognition, propaganda and oodles of dark money, it's going to be nearly impossible to get someone who refuses to compromise out of an important seat.

Because that Senator, for example, is safe and no longer has to care about the needs of half the country, or even anyone else at all. They are getting rich, have a secure job and have a massive political machine behind them. The longer they are there, the more entrenched they become, and the less challenged they are for their seat, the less they have to work with anyone or adapt their stances on policies that affect everyday Americans.

Now, I'm sure there are a lot more issues that could come up, and there are likely some better arguments out there, but it seems to me that if we ever want to get back to a place where politicians compromise and work together, we're going to have to start somewhere, and I think we have to begin with term limits. But that won't happen by leaning on compromise, ironically; that's going to have to be forced somehow some way. And hopefully it starts with a Senate majority on the Left.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Democrat party switch lie / myth

Historical face punch courtesy GOP-TEA-PUB TUMBLR. Tumblr keeps taking this fact bomb down. Spread it.

June 17, 1854The Republican Party is officially founded as an abolitionist party to slavery in the United States.

October 13, 1858 During the Lincoln-Douglas debates, U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas (D-IL) said, “If you desire negro citizenship, if you desire to allow them to come into the State and settle with the white man, if you desire them to vote on an equality with yourselves, and to make them eligible to office, to serve on juries, and to adjudge your rights, then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican party, who are in favor of the citizenship of the negro. For one, I am opposed to negro citizenship in any and every form. I believe this Government was made on the white basis. I believe it was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever, and I am in favor of confining citizenship to white men, men of European birth and descent, instead of conferring it upon negroes, Indians, and other inferior races.”. Douglas became the Democrat Party’s 1860 presidential nominee.

April 16, 1862 President Lincoln signed the bill abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. In Congress, almost every Republicanvoted for yes and most Democrats voted no.

July 17, 1862 Over unanimous Democrat opposition, the Republican Congress passed The Confiscation Actstating that slaves of the Confederacy “shall be forever free”.

April 8, 1864 The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. Senate with 100% Republican support, 63% Democrat opposition.

January 31, 1865 The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. House with unanimous Republican supportand intense Democrat opposition.

November 22, 1865

Republicans denounced the Democrat legislature of Mississippi for enacting the “black codes”which institutionalized racial discrimination.

February 5, 1866

U.S. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens(R-PA) introduced legislation (successfully opposed by Democrat President Andrew Johnson) to implement “40 acres and a mule” relief by distributing land to former slaves.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rights to blacks.

May 10, 1866

The U.S. House passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the laws to all citizens. 100% of Democrats vote no.

June 8, 1866

The U.S. Senate passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the law to all citizens. 94% of Republicans vote yes and 100% of Democrats vote no.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rightsto blacks in the District of Columbia.

July 16, 1866 The Republican Congress overrode Democrat President Andrew Johnson’s vetoof legislation protecting the voting rights of blacks.

March 30, 1868 Republicans begin the impeachment trialof Democrat President Andrew Johnson who declared, “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government of white men.”

September 12, 1868 Civil rights activist

Tunis Campbell

and 24 other blacks in the Georgia Senate (all Republicans) were expelled by the Democrat majority and would later be reinstated by the Republican Congress.

October 7, 1868 Republicans denounced Democrat Party’s national campaign theme: “This is a white man’s country: Let white men rule.”

October 22, 1868 While campaigning for re-election, Republican U.S. Rep. James Hinds (R-AR) was assassinated by Democrat terrorists who organized as the Ku Klux Klan. Hinds was the first sitting congressman to be murdered while in office.

December 10, 1869 Republican Gov. John Campbell of the Wyoming Territory signed the FIRST-in-nation law granting women the right to vote and hold public office.

February 3, 1870 After passing the House with 98% Republican support and 97% Democrat opposition, Republicans’ 15th Amendmentwas ratified, granting the vote to ALL Americans regardless of race.

February 25, 1870 Hiram Rhodes Revels(R-MS) becomes the first black to be seated in the United States Senate.

May 31, 1870 President U.S. Grant signed the Republicans’Enforcement Act providing stiff penalties for depriving any American’s civil rights.

June 22, 1870 Ohio Rep. Williams Lawrence created the U.S. Department of Justice to safeguard the civil rights of blacks against Democrats in the South.

September 6, 1870

Women votedin Wyoming in first election after women’s suffrage signed into law by Republican Gov. John Campbell.

February 1, 1871

Rep. Jefferson Franklin Long (R-GA) became the first black to speakon the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

February 28, 1871

The Republican Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1871providing federal protection for black voters.

April 20, 1871

The Republican Congress enacted the Ku Klux Klan Act, outlawing Democrat Party-affiliated terrorist groups which oppressed blacks and all those who supported them.

October 10, 1871

Following warnings by Philadelphia Democrats against black voting, Republican civil rights activist Octavius Cattowas murdered by a Democrat Party operative. His military funeral was attended by thousands.

October 18, 1871

After violence against Republicans in South Carolina, President Ulysses Grant deployed U.S. troopsto combat Democrat Ku Klux Klan terrorists.

November 18, 1872

Susan B. Anthonywas arrested for voting after boasting to Elizabeth Cady Stanton that she voted for “Well, I have gone and done it — positively voted the straight Republican ticket.”January 17, 1874

Armed Democrats seized the Texas state government, ending Republican efforts to racially integrate.

September 14, 1874

Democrat white supremacists seized the Louisiana statehouse in attempt to overthrow the racially-integrated administration of Republican Governor William Kellogg. Twenty-seven were killed.

March 1, 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, guaranteeing access to public accommodations without regard to race, was signed by Republican President U.S. Grant and passed with 92% Republican support over 100% Democrat opposition.

January 10, 1878

U.S. Senator Aaron Sargent (R-CA) introduced the Susan B. Anthony amendment for women’s suffrage. The Democrat-controlled Senate defeated it four times before the election of a Republican House and Senate that guaranteed its approval in 1919.

February 8, 1894

The Democrat Congress and Democrat President Grover Cleveland joined to repeal the Republicans’ Enforcement Actwhich had enabled blacks to vote.

January 15, 1901

Republican Booker T. Washingtonprotested the Alabama Democrat Party’s refusal to permit voting by blacks.

May 29, 1902

Virginia Democrats implemented a new state constitution condemned by Republicans as illegal, reducing black voter registrationby almost 90%.

February 12, 1909

On the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, black Republicans and women’s suffragists Ida Wells and Mary Terrellco-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

May 21, 1919

The Republican House passed a constitutional amendmentgranting women the vote with 85% of Republicans and only 54% of Democrats in favor. In the Senate 80% of Republicans voted yes and almost half of Democrats voted no.

August 18, 1920

The Republican-authored 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote became part of the Constitution. Twenty-six of the 36 states needed to ratify had Republican-controlled legislatures.

January 26, 1922

The House passed a bill authored by U.S. Rep. Leonidas Dyer(R-MO) making lynching a federal crime. Senate Democrats blocked it by filibuster.

June 2, 1924

Republican President Calvin Coolidgesigned a bill passed by the Republican Congress granting U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans.

October 3, 1924