#literary references

Note

Idk if you ever talked about this but I'm reading the bronte sisters novels again and GRRM is so obviously influenced by the sisters (jeyne and the eyrie being very obviously jane eyre references) but now I cannot stop thinking about the way Sansa is literally Cathy 2 and Jon Hareton from Wuthering Heights like.... it's crazy and fits so well thematically and I always thought the ending of WH with Cathy 2 and Hareton was so romantic (Hareton being essentially an unloved "bastard" who ends up winning the heart of his cousin who grew up disliking him and is seen as a copy of her beautiful mother)

GRRM is cooking a soup and using all kinds of literary influences as ingredients. But this novel seems to have just plopped into the pot barely diced.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

#for whom the bell tolls#?#meme#joke#spy kids#rocky#sylvester stallone#meta#art#haha#funny#humor#lol#relatable memes#thee#is all of us really#edit#edited image#edited#digital#artistry#amusing#snerk#lulz#made me laugh#funny things#reference#referential humor#literary references#nerd jokes

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Pan by J.M. Barrie

Chapter 1: Peter Breaks Through

#peter pan#jeff satur#lucid#jeff satur lucid#lucid mv#jeff satur mv#jeff satur music#thai music#literary references#bro I have so many of these coming

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frankenstein's monster, but I recognize the tits on the monster bc I donated mine to science post top surgery-

#it speaks#hello dears#dont worry about it#Frankenstein#victor frankenstein#ghoulsjournal#marry shelley#marry shelly would be proud#is this anything#hmm#weird#monster#monsters#strange and unusual#wild#top surgery#literary references#classic literature

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literary References in The Charioteer: Treasure Island

It features in Sandy's party scene, and while Laurie is reading it, someone comes up and asks him if it is a 'Queer Book'. Laurie says 'no', he walks away and Laurie continues reading.

If I had to summarise the theme, it would be a book about something being found that was thought to be lost 👀👀 And the pain that follows. The descriptions of the sea that Mary quotes are beautiful:

"Soon cool draughts of air began to reach me; and a few steps farther I came forth into the open borders of the grove, and saw the sea lying blue and sunny to the horizon, and the surf tumbling and tossing its foam along the beach. I have never seen the sea quiet round Treasure Island. The sun might blaze overhead, the air be without a breath, the surface smooth and blue, but still those great rollers would be running along all the external coast, thundering and thundering by day and night; and I scarce believe there is one spot in the island where a man would be out of earshot of their noise."

Laurie is interrupted by Harry and his 'ratings' arriving and being ejected; Ralph and Alec arguing about it; Ralph assuming Laurie has guessed they were ex's (!); Laurie says 'You would have missed the sea' and Ralph says 'I'll need to get used to that'.

That line about never being out of earshot of the waves is ringing in my ears at this point.

Then:

"Alec formed the opinion that I took too much on myself." A rush of old memories went through Laurie like a pain. "I've never noticed," he said, "that the competition to take things on was as killing as all that."

Ralph picks up the book, says "Oh, Spuddy," laughing and looking away, and gets up quickly to get more drinks. Laurie feels a fool.

Oh God, "Laughing and looking away".

I always thought that was Ralph laughing involuntarily and then not wanting Laurie to think he was being unkind. Now I wonder if he is having a little 'moment'. It's such a beautiful choice of book to evoke all kinds of resonances without explicitly saying anything.......

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

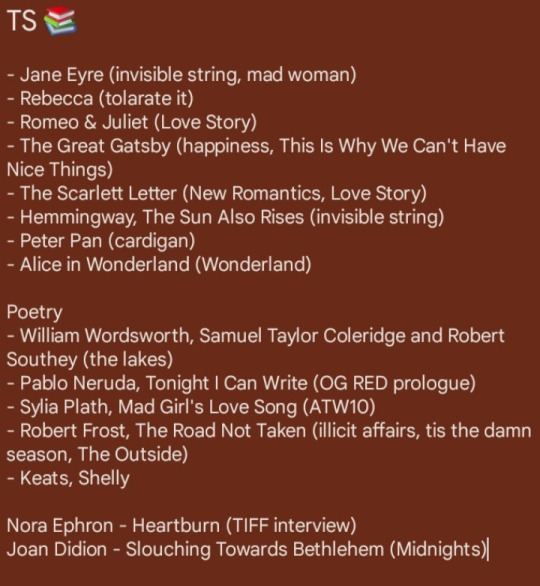

taylor's references to literature

new romantics, 1989 (2014) / don't blame me, reputation (2017) / happiness, evermore (2020) / you're on your own, kid, midnights (2022)

---

literary references under the cut

"we show off our different scarlet letters" -> the scarlet letter by nathaniel hawthorne

"i once was poison ivy, but now i'm your daisy" -> the great gatsby by f. scott fitzgerald

"i hope she'll be a beautiful fool, who takes my spot next to you" -> the great gatsby by f. scott fitzgerald

"so long daisy may" -> li'l abner by al capp

#taylor swift#ts#1989#reputation#evermore#midnights#new romantics#don't blame me#happiness#you're on your own kid#yoyok#taylor swift lyrics#web weaving#literary references#id in alt text

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Literary Reference in The Magnus Archives (I think)

These are just the ones I noticed. If you caught references I didn't, feel free to add on! Since this'll be pretty long, it's all under the cut.

Character Namesakes:

(One or two of these may be a coincidence)

Algernon Blackwood - Martin Blackwood, Dr. Algernon Moss (mag 98)

Braham Stoker - Tim Stoker

Stephen King - Melanie King

M.R. James - Sasha James

Mary Shelley - Michael Shelley

Lucy Leitner - Jurgen Leitner, "Leitners"

Clive Barker - Georgie Barker

James Herbert - Trevor Herbert

Jaimie Delano - Eric Delano

Institute Names

"Count Magnus" by M.R. James - The Magnus Institute, Jonah Magnus

"The Fall of the House of Usher" by Edgar Allen Poe - The Usher Foundation

Pu Songling - The Pu Songling Research Centre

Direct References in Statements

Wilfred Owen, "Exposure" by Wilfred Owen - mag 7 (Wilfred Owen features in this episode and the statement giver, who served with him, references "Exposure".)

Misery by Stephen King -mag 17 (A passing mention of this book being shelved at the library.)

The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer - mag 17, mag 70 (In mag 17, the statement giver finds The Boneturner's Tale which, though obviously modern, is kind of Canterbury Tales fanfiction, focusing on a character who is either traveling with or stalking Chaucer's pilgrims. In mag 70, a character can recognize Middle English due to having studied Chaucer in high school.)

The Duchess of Malfi by John Webster - mag 31 (The statement giver references a line from the play to help describe an avatar of the Hunt.)

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller - mag 38 (The statement giver's favorite book, a signed copy is among the objects stolen by the homophobic vase.)

Needful Things by Stephen King - mag 46 (The statement giver owns a small shop which he claims is often compared to the shop in Needful Things.)

"Antigonish" by William Hughes Mearns - mag 85 (The central figure of this poem, or something resembling it, gives a statement.)

Die Nachtstücke (The Night Pieces), "The Sandman" by E.T.A. Hoffman - mag 98 (The statement giver recalls having read "The Sandman" as a child and, in his adulthood, is haunted by something resembling Hoffman's Sandman.)

Five Go Down to the Sea by Enid Blyton - mag 147 (Referenced in passing as the only book Annabelle Cain took with her when she ran away from home as a child.)

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy - mag 147 (Referenced by Annabelle Cain as she waxes philosophic about free will.)

Leitners

(This list will, of course, only include real books referenced as Leitners. No Boneturner or Ex Altiora.)

The Dictionaire Infernal (Infernal Dictionary) by Jacques Collin de Plancy - mag 46

Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches) by Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger - mag 46

The Tale of a Field Hospital by Sir Frederick Treves - mag 68

The Key of Solomon by Solomon the King (purportedly) - mag 65, mag 70

The Seven Lamps of Architecture by John Ruskin - mag 80

Journal of the Plague Year by Daniel Defoe - mag 80, mag 91

Miscellaneous:

Dracula by Braham Stoker - mag 56 (The title of this episode, "Children of the Night" is taken from a line in Dracula, and is a pretty clever reference, if I do say so myself.)

Diana Wynn Jones - mag 81 (Referenced in passing as an author who Jon briefly liked as a child)

#the magnus archives#jon sims#jarchivist#martin blackwood#tim stoker#sasha james#melanie king#the library of jurgen leitner#michael shelley#annabelle cain#literary references#my post#long post

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've added on so here is the list again: ✨️

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

GRRM writes the best parodies.

Daario rolled toward her, his eyes open. “Daenerys.” He smiled a lazy smile. That was another of his talents; he woke all at once, like a cat. “Is it dawn?”

“Not yet. We have a while still.”

“Liar. I can see your eyes. Could I do that if it were the black of night?” Daario kicked loose of the coverlets and sat up. “The half-light. Day will be here soon.”

“I do not want this night to end.” (ADWD, Daenerys VII)

*

Juliet. Wilt thou be gone? it is not yet near day:

It was the nightingale, and not the lark,

That pierced the fearful hollow of thine ear;

Nightly she sings on yon pomegranate-tree:

Believe me, love, it was the nightingale.

Romeo. It was the lark, the herald of the morn,

No nightingale: look, love, what envious streaks

Do lace the severing clouds in yonder east:

Night's candles are burnt out, and jocund day

Stands tiptoe on the misty mountain tops.

I must be gone and live, or stay and die.

*

When GRRM has you acting out an iconic love scene from world literature except the surrounding context undercuts it in every way because you’re not a romantic heroine, only a tragic villain who thinks she is one.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aw, what a pleasant (and studious!) little fella. :] Sure hope nothing bad happens to him after he turns 10— It’s a pretty big milestone for him, y’know?

#william afton#fnaf fandom#kid design#fan design#pond’s art#pond’s sketch#fnaf headcanons#literary references

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

could you do a list of literary references in taylor swift music?

Thanks! I haven't been able to go through Midnights thoroughly yet for this one but I will soon. For now, here is TS and Literary References in its current state. Hopefully that will be of some help!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big Reputations: Celebrity and Temporal Duration in/of Dickinson Lyrics by Elizabeth Dinneny

Source (x)

On December 10, 2020, Emily Dickinson’s 190th birthday, singer-songwriter-superstar Taylor Swift announced the surprise release of her ninth studio album, evermore. The release was a shock, as Swift had released her first surprise album, folklore, a short five months previous. Swift called folklore “a product of isolation,” made together with a small group of musicians during the first several months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Its aesthetic, which continues into evermore, evokes the newly-popular “cottagecore” trend.[1] Swift spoke of her inspiration for the album’s cover photograph with Entertainment Weekly: “I had this idea…that it would be this girl sleepwalking through the forest in a nightgown in 1830” (Suskind). In folklore’s black-and-white cover image, Swift is the sleepwalking girl wearing a custom Stella McCartney jacket (Grindell) in the year of Emily Dickinson’s birth. In evermore’s full-color image, Swift has emerged from the woods and looks back toward it—notably diverging from the look of her eight previous album covers, in which her face appears up close, front and center. Perhaps evermore contains Swift’s least autobiographical lyrics, as some critics have suggested (Petrusich), thus opening up even more possibilities for fictional and biographical inspiration.[2] But we might take a more critical approach. Using the term “autobiographical” risks feigning individual influence and a singular archive. Taylor Swift is certainly known for writing specific autobiographical elements into her lyrics, but we need not abandon autobiography in the face of evermore’s expansive archive. Rather, we should ask: how do these archives mediate the autobiographic? Where do we find Swift and Dickinson, together, in “these imaginary/not imaginary tales” (@taylorswift13)?

The two so-called “sister record[s]” (@taylorswift13) contain stories from myriad archives, including allusions to Romanticism and Swift’s own life. While folklore, with its mentions of Wordsworth and the Lake District, appears invested in the figures and motifs of British Romanticism (Ellis), evermore seems most influenced by one writer in particular: Emily Dickinson. As a result of popular culture’s recent increased interest in Dickinson, Taylor Swift fans knew enough about the poet to begin speculating about Dickinson’s presence in evermore almost immediately. Most conspicuous is the album’s title (and concluding) track, “evermore,” which meditates on a failed relationship whose “pain would be for / evermore” (Swift et al.). The song recalls the final line of a letter-poem written by Emily Dickinson to Susan Huntington Dickinson. The poem ends:

I spilt the dew –

But took the morn, –

I chose this single star

From out the wilde night’s numbers –

Sue _ forevermore!

(OMC 76)

The song and the poem differ significantly in tone, as “evermore” recounts the miscommunications of a past relationship, and Dickinson’s letter expresses an endless devotion to her sister-in-law and lover, Susan Huntington Dickinson. However, both texts share an investment in letter-writing for the articulation and navigation of an intimate relationship. In “evermore,” one narrator is found “writing letters / addressed to the fire,” indicating a failure in communication and the eventual demise of the relationship. Dickinson’s letter-poem to Susan, in addition to celebrating an enduring relationship, demonstrates the value of the letter (and lyric) as a form of intimate expression. Far from being “addressed to the fire,” Emily Dickinson’s letter-poems made their way into Susan Huntington Dickinson’s hands, “a hedge away,” (OMC 76) for decades.

The duet’s speakers also use metaphors of shipwreck to recall their relationship’s collapse. For example, Swift sings, “Hey December / Guess I’m feeling unmoored,” and, later, Bon Iver sings, “I’m on the waves, out being tossed / Is there a line that I could just go cross?” These lines are only a few of evermore’s broad nautical and temporal vocabulary; the album opens with the line, “I’m like the water / when your ship rolled in that night” (Dessner and Swift). In “long story short,” whose joyful tone matches that of Dickinson’s aforementioned letter-poem, Swift sings, “my waves meet your shore / ever and evermore” (Dessner and Swift). The speaker of “long story short” hopes to moor, for evermore, in the song’s addressee. Here, we turn to Emily Dickinson again; in her poem that begins “Wild nights – Wild nights!”, the speaker is “Done with the Compass - / Done with the Chart!” and wishes to “moor” in the poem’s addressee:

Wild nights - Wild nights!

Were I with thee

Wild nights should b

Our luxury!

Futile - the winds -

To a Heart in port -

Done with the Compass -

Done with the Chart!

Rowing in Eden -

Ah - the Sea!

Might I but moor - tonight -

In thee!

(Fr269A)

Both Dickinson and Swift invoke the shore as the site of a relationship’s convergence.[3] The speakers escape turbulent waters by finding stability in another person, on the shore, repeatedly. The comparison is complicated by the conditional temporality of “wild nights,” and the poem’s queer interpretations and theorizations cannot go unstated (Smith, Brinck-Johnsen), By reading Dickinson and Swift together, we see how both lyricists consider temporality and the potential of a “forevermore” in multiple forms, including that of an intimate romantic relationship.

The folklore/evermore “era,” to use a Swiftian term (Braca), embraces a cottagecore aesthetic, easily identifiable in the album’s lyrics, acoustic instrumentation, woodsy cover art, and promotional images. The cottagecore aesthetic combines the fable of Dickinson the genius recluse with Dickinson the R/romantic, complementing the conditions and themes of both Swift albums. Swift’s most cottagecore song, “ivy,” has received significant attention from a number of Dickinson fans, who believe the song is inspired by Emily and Susan’s relationship. The album’s tenth track, which has been described as “a folky, convoluted song,” (Pareles) involves a married speaker who falls in love with someone else. The speaker describes the three of them (speaker, lover, husband) in a room, possibly at a party:

I wish to know

The fatal flaw that makes you long to be

Magnificently cursed

He’s in the room

Your opal eyes are all I wish to see

He wants what’s only yours (Swift, Antonoff, Dessner)

Neither the speaker nor the “magnificently cursed” lover are assigned pronouns, leaving plenty of room for queer interpretations of this song about a forbidden, passionate relationship, which the speaker calls “the goddamn fight of my life” (Swift et al). In their own queer readings, Dickinson fans have made fan videos of “EmiSue” scenes set to the song, whose lyrics can be cleanly mapped onto their relationship.[4] In addition to biographical consistencies, the characters of “ivy” employ metaphors of death and augmented temporality that resonate affectively with much of Dickinson’s poetry. The song begins in a graveyard, or at least a metaphorical one: “How’s one to know? / I’d meet you where the spirit meets the bones / In a faith-forgotten land” (Swift et al.).[5] The graveyard functions as a safe place for the two to get together, removed from the public eye and from the expectations of “the living.” Among the dead, the illicit affair of “ivy” is allowed to flourish, as the speaker sings, “my house of stone / your ivy grows, / and now I’m covered in you” (Swift et al).

Using botanical imagery, the speaker describes an organic infiltration of the “magnificently cursed” lover, or unruly ivy, on the married, heterosexual home. Further, the speaker sings, “the old widow goes to the stone every day / But I don’t, I just sit here and wait / Grieving for the living” (Swift et al.). With its affinity for the dead, this secret relationship thus appears unconcerned with linear time and social realities. The speaker grieves for their living relationship, which has yet to end, then happily escapes to “your dreamland” (Swift et al.). Emily Dickinson wrote many poems about death, graves,[6] and privacy.[7] Although we push back on the idea of Dickinson as recluse, Dickinson’s life-long romantic relationship with Susan was certainly enjoyed in private. Similarly, the contentedly secret relationship of “ivy” defies heterosexual expectations of public interpellation. Rather than become legible to friends (as the three seem to travel in similar circles) and family, the two, “a goddamn blaze in the dark,” endure.

Swift is known for leaving self-referential clues throughout her corpus, so it’s worth noting that evermore might not contain her first nod to Dickinson. repuation, Swift’s album most explicitly about her struggles with fame and social media, ends with the album’s most romantic and sole piano track, “New Year’s Day.” In the song, the speaker sings to another “you,” the morning after a New Year’s Eve party. A similar reflection on the duration of romantic relationships, Swift implores them, “Don’t read the last page,” and tells of what remains following the celebration:

There’s glitter on the floor

After the party

Girls carrying their shoes

Down in the lobby

Candle wax and Polaroids

On the hardwood floor

…you and me, forevermore

Here, again, Swift uses “forevermore” to describe hope for the endurance of an intimate relationship, just as she uses the phrase in “long story short” and “evermore.” “New Year’s Day” emerges as the album’s most cathartic moment. After numerous tracks about Swift’s most arduous years in the spotlight, “New Year’s Day” finishes the album as a song solely about her intentionally private relationship with current partner Joe Alwyn (Stanton). In addition to repeating the desire for a forevermore relationship, the more transparent “long story short” explicitly references these same reputation moments from Swift’s life and discography, offering a quick account of Swift’s romantic troubles and a longer reflection on Swift’s falling out of public favor. As one critic writes, “conceptually, it [“long story short”] retreads reputation ground,” (Ahlgrim and Larocca) featuring clear autobiographic elements and expressing a frustration with the attention and misogynistic demonization that accompanies fame: “And I fell from the pedestal / Right down the rabbit hole / Long story short, it was a bad time” (Dessner and Swift).

Rather than continue to pick apart evermore’s lyrics for possible references to Dickinson’s poetry (as there are plenty more[8]), we should turn to overlapping and interacting thematics and conditions of production. In social media posts and interviews, Taylor Swift emphasized the conditions of the sister albums’ production; that is, she underlined the fact that both were created “in isolation,” in relatively quick succession, and secretly amid a small circle of collaborators (@taylorswift13). Swift told Entertainment Weekly: “I wasn’t making these things with any purpose in mind. And so it was almost like having it just be mine was this really sweet, nice, pure part of the world as everything else in the world was burning and crashing and feeling this sickness and sadness. I almost didn’t process it as an album. This was just my daydream space” (Suskind). Emily Dickinson did not write her poetry during a global pandemic, but she did often write in a kind of isolation, disseminating her poetry among close friends and family with less regard for the expectations of print publishing (Smith). Isolation here means, of course, not the sequestration of the individual artist, but the cultivation of a small, trusted collective through which the artist’s work is circulated and workshopped. Their works-of-isolation now commercial and widely distributed art objects, both Dickinson and Swift have grown into infamous public figures, onto whom their readers, listeners, and critics project personalities, intentions, and rumors.

If Taylor Swift is a celebrity, then Emily Dickinson’s ghost is one as well. Dickinson’s ghost is the figure of Dickinson in and constructed by popular culture, shifting and disappearing into words and works like those discussed in this exhibition. By ghost, I mean the specter cast by fame, a formulation that Dickinson used in her own writing, “at a time when ghosts were ubiquitous within literary tourism and when a visit to the writer’s home or meeting with a celebrity was akin to a spiritual encounter” (Finnerty 34). Several speakers found in Dickinson’s poetry revere the dead like a fan might revere their favorite celebrity, visiting the star's birth place, home, and grave (Finnerty 45). The dead celebrity thus becomes a ghost, the product of public reverence or, to use a word from Swift’s lyrical vocabulary, the product of reputation. Though she did hope to publish, Dickinson ruminated on fame across many poems and letters, expressing a desire for it but also often a deep concern about the restrictions of print publishing (Reynolds, “I’m Nobody…”, Finnerty) and the potential misconstruing of the person by celebrity. Commercial publishing opens up the potential for a ghost, made immortal but out of the artist’s control, defined by critics, scholars, and other readers. In her lifetime, Dickinson’s handmade fascicles were self-published; she produced copies of poems, bound them together, and distributed them herself, but the fascicles on their own do not conjure the specters of Dickinson that we encounter today. Martin Greenup reads the inaccessible dead of Dickinson’s “Safe in their Alabaster chambers” as her own poems, the chambers her fascicles if she did not publish commercially (356). Without publishing, Dickinson and her poems would most likely not endure the unforgiving abyss of time, and her fascicles would remain untouched by generations of readers, safe but dead, we might say, “forevermore.”

Perhaps confirming her most serious anxieties and optimisms, Dickinson haunts writers and popular culture more than a hundred years after her death. Specters of her reputation emerge across these essays, making this exhibition a kind of graveyard of multiple Emily Dickinsons, none of them “true,” many of them contradictory. In Taylor Swift’s introduction to reputation, she writes that “gossip blogs will scour the lyrics” to explain the meaning of each song, connecting them to Swift’s ex-boyfriends and paparazzi photos. She concludes with a critique of celebrity and identity itself: “We think we know someone, but the truth is that we only know the version of them they have chosen to show us. There will be no further explanation. There will just be reputation” (Swift). Much of the same can be said about Emily Dickinson, whose poetry and larger archive has been scoured for evidence of male lovers, proof of her supposed isolation, and combed through for final, stable versions of her poems.[9] Despite these attempts at discerning the facts, there will only ever be Dickinson’s reputation, as constructed by her readers. We might respond to Swift’s assertion by asking what we do, then, with the archive. How should we interpret the archive of the living (or dead) person? Let us turn, one last time, to Dickinson’s own lyrics:

Fame is the one that does not stay —

It’s occupant must die

Or out of sight of estimate

Ascend incessantly —

Or be that most insolvent thing

A Lightning in the Germ —

Electrical the embryo

But we demand the Flame

The speaker is uninterested in fame, which remains at the mercy of cultural interest and the status of its dead occupant. Instead, the speaker urges us to “demand the Flame.” What Flame of Dickinson’s must we demand? Perhaps the Flame is another kind of ghost, but one that is much more difficult to make out. The Flame might be the stubborn specter that endures in spite of attempts at erasure or adjustment. Despite Mabel Loomis Todd, Higginson, and others’ efforts to shape Dickinson’s legacy into one more marketable, more heterosexual, and more conservative, there remains a stubborn ghost, a “goddamn blaze in the dark,” (Swift et al) deep in the archive. She appears only in flickers, but she endures, just as we must demand, over and over, to see her.

Swift’s evermore is only the most recent iteration of Dickinson in music; numerous artists and songwriters have been inspired by the poet. For a selection of these, explore the exhibition's curated Spotify playlist.

#gaylor#emily dickinson#literary references#evermore#folklore#ivy#reputation#new year's day#new years day#joe alwyn#gaylorarchive

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

East Africa Pilot (The Charioteer literary references)

@spudodell @tigerballoons

I can't be sure but I think maybe the reference to the 'East Africa Pilot' is this:

So if that's true it would be very factual indeed! Hence Laurie thinking it an odd choice. And Ralph might well have a spare copy knocking about from his tropical days or be able to pick one up and as it would be out of date it wouldn't be expensive - like giving someone an old copy of the A-Z road map or something.

What do we think?

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

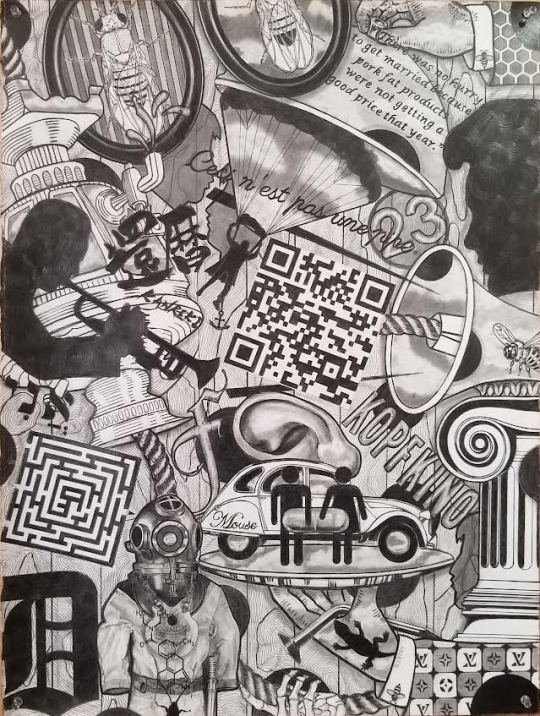

J. M. Hurowitz - Untitled - 2023 - pencil on paper - 22.5 x 30 inches

This is my most recent work, done specifically for a friend's 60th birthday. Like my other drawings, there are references to art, literature, science, history and other personal interests, as well as images with no special significance other than the fact that I felt like including them. And like my other drawings, my hope is that anyone viewing this work will take the time to make their own connections and interpretations.

#original work of art#drawing#pencil on paper#text in art#representational art#referential art#literary references#horror vacui#silhouettes#qr code#metaphorical#drosophila melanogaster/fruit fly

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"After reading out loud from this dense and decorative passage, Rilke suffers a nosebleed--one wonders if it was a precursor of the death he had within him, as his character theorizes that everyone has a death within them, living dormant for two more decades, a cancer of the blood, catalyzed by the prick of one of his favorite roses, while living in Switzerland."

"Writing a letter, you get carried away and make incautious remarks. In letters, the soul always wishes to do the talking and generally it makes a fool of itself."

"There was a time when he'd thought a house, a wife, a child, would make his life more tangible. But now he wishes to withdraw more deeply into himself, into the monastery inside him, replete with great bells. He would like to forget everyone, forget his wife and his child. One must live within one's work and stay there...We are not made to have two lives, he writes passionately in his irritation, there can only be one."

"If we opened people up, we'd find landscapes."

-- all quotes/excerpts from Kate Zambreno's "Drifts"

7 notes

·

View notes