#international literature translated to portuguese

Text

#bookshelf#rearranged#books#international literature translated to portuguese#international literature in other languages#literature from portuguese speaking countries#and children's literature#plus non fiction by subject

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selva Almada

youtube

Selva Almada was born in 1973 in Villa Elisa, Argentina. Almada is regarded as one of the most powerful voices in contemporary Argentine and Latin American literature. Her first novel The Wind That Lays Waste was nominated for Argentinian Book of the Year upon its publication in 2012. In 2019, when it was published in English, it won the Edinburgh International Book Festival's First Book Award. Almada has been compared to William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, and Flannery O'Connor. She has been a finalist for the Tigre Juan Award, the Rodolfo Walsh Award, shortlisted for the Vargas Llosa Prize for Novels, and longlisted for the International Booker Prize. Almada's work has been translated into several languages, including Portuguese, French, Turkish, Swedish, and Italian.

#writers#woman writers#authors#books#argentina#latin america#latin american literature#latina#hispanic#south america#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 28, 2023

There are as many ways of translating a literary text as there are translators. The act of carrying a work from one language to another — an art as much as a craft — is anything but mechanical: Translators’ choices are informed by their sensibilities, their emotional landscape, their background.

Literary translators have, however, historically received little recognition. Readers who love books that were rendered in their words often haven’t known their names, since they were not featured on the covers. Within publishing, they were frequently underpaid and given no rights or royalties for their work.

Efforts by translators and by organizations like PEN America, which recently issued a manifesto on literary translation, have brought the field greater visibility, helping to cement the rights of translators and to raise awareness of literary translation as a creative art in its own right.

For a frank discussion of the state of translation, The Times gathered a group of recognized translators:

Samantha Schnee, a translator from Spanish, is the founding editor of Words Without Borders, a digital literary magazine of international literature in English.

Allison Markin Powell, a translator from Japanese, also represents the PEN America Translation Committee on the organization’s board of trustees.

Jeremy Tiang, originally from Singapore, translates from Chinese and is also a novelist and playwright.

Mui Poopoksakul is a Thailand-born lawyer turned literary translator.

Bruna Dantas Lobato, originally from Brazil, is a literary translator from Portuguese and a writer.

This conversation has been edited for concision and clarity.

JULIANA BARBASSA: Over 50 years ago, at the first World of Translation Conference organized by PEN, Isaac Bashevis Singer said: “Translation must become not only an honorable profession, but an art. While I don’t like bloody revolutions, I would love to see a translators’ revolution.” He went on to say of translators that “in all of literature they have been the pariahs,” and to call on the conference to be “the beginning of a rebellion where ink instead of blood will be shed.”

What revolution was he alluding to there, and how much has been accomplished in the years since?

SAMANTHA SCHNEE: There are two ways to answer that question. One, translators' rights is something I think Singer was referring to. But I also think that the translator’s role as a conduit for literature in translation is equally important. To the first issue, I would say a lot of progress has been made in the last 50 years. It was the case that translators routinely were expected to grant copyright in perpetuity for their translations.

Famously, [Gregory] Rabassa’s translation of [Gabriel] García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” was a copyright grant, which really ignores the role of the translator as a creative aspect of the work. No two translators would ever create the same translation from the same text. So I think progress has been made in areas like that.

But I think we have a lot of progress yet to go. For example, the way I see the role of a translator today is very much as a curator. Translators are much more active in the market now: Translators are acting as scouts, in many cases acting as agents. Almost always those roles go unpaid.

I do think translators have a lot more power than certainly 50 years ago, and I would argue even 20 years ago. Translators need to keep fighting to keep those issues at the forefront.

We as an Anglophone culture are mass exporters of all sorts of culture, and we are not importing even a fraction of that. Translators play a really critical role in helping to counteract that.

BRUNA DANTAS LOBATO: In addition to wanting fair pay, wanting our art to be recognized, our names on the covers of books, I also would like to see a push away from this very academic sentiment that comes out of comp lit departments: that it’s some white person from this culture who goes into another culture and imports these artifacts.

There is this sense that it’s a transaction, and it’s one-directional. It feels like a very anthropological impulse from maybe a couple of centuries ago. I would like instead to have more of a conversation.

JEREMY TIANG: In the English-speaking world, we are enthralled with the idea of the single author. And so conversations around translations either focus entirely on the original author, rendering the translator subservient, or else talk about the translator as if the only way the translator could have agency is to go completely rogue, disregard all notions of faithfulness and assert their own version of the book at the expense of the original. The idea that translation is a collaborative process, that the author and the translator are building something together, doesn’t really get as much airtime as I would like.

BRUNA: It’s a question of authorship, right? It’s an opportunity to hold translators accountable for the work that we do. If I don’t even know who did this, how am I going to evaluate or ask the right questions?

The other thing is that the translator as author brings so much personal baggage into the work. We can’t translate outside of ourselves. I definitely use my experiences both as a writer — my knowledge of craft — and my experiences as a reader, in everything that I translate. I also bring my emotional experiences.

It means that I won’t bring unexamined biases into the work. It means that I have an opportunity to be in genuine dialogue with the work. All of that is impossible if I am erased, my identities are erased, my experiences are erased.

ALLISON MARKIN POWELL: What a translator brings to the work of doing the translation, we also bring to the works that we’re inspired to translate. Historically that was very much a white male academic’s perspective.

I’m part of a collective called Strong Women Soft Power that promotes Japanese women writers in translation. When we formed it I started looking at the numbers — who was being translated. Despite my perception that there were a lot of Japanese women writers being translated, that was actually not the case. That led me to look at what the landscape was like in Japan. And in Japan it was a much more balanced environment between male and female writers. And that wasn’t being accurately reflected in English translation.

JEREMY: I want to mention the unevenness of the playing field, which might not be apparent to people outside of the translation world.

Someone working from, say, German could quite feasibly, if they were sufficiently established, make a living simply by waiting for publishers to come to them with German books to translate. Whereas with less represented languages or regions, the translator often has to advocate for the book or it doesn’t get translated at all. Thai literature in English translation pretty much wouldn’t exist if Mui weren’t finding these books and putting them in front of publishers.

MUI POOPOKSAKUL: That plays into two points, like what Sam said earlier about the unpaid labor of translation. When I work on a book project, I follow it from start to finish. I read the books, I pick the books, I pitch the books, I translate the samples — initially I was never paid for samples. That is a real barrier to entry for a lot of people.

In terms of who gets to translate, I’m really excited by this movement to give more opportunities to heritage language speakers, translators from the countries of the literature that they’re translating from. This will really broaden the landscape of what becomes available in English.

JULIANA: Have you seen a shaping of what books are available in English because of this advocacy by translators?

SAMANTHA: Absolutely. If you think of publishing as an ecosystem, the translators are like the seed spreaders. We’re diversifying that ecosystem. There’s a fixed number of editors out there; they will have certain sensibilities and they will be limited by the market in the choices they can make. When you work with translators, you have whole other worlds opened up to you.

JEREMY: The translator is often the only person who can see both sides. The source language country might have rights agents doing good work, but they don’t know the English-language publishing world as well. The Anglophone world has well-meaning publishers who would love to do more translation, but they have no way of knowing the source language landscape. And apart from basically a few large Western European cultures which are well resourced with book scouts, in general, the translator is often the only person with a clear view of both sides.

ALLISON: If a book from a language that you work from becomes successful, do you feel like that starts to color readers’ or editors’ expectations? In Japan this has been called the [Haruki] Murakami effect. Do you have that experience?

BRUNA: I definitely have that experience a lot. I was recently advocating for a book called “The Dark Side of the Skin,” about racism and police brutality in Brazil, by Jeferson Tenório. Some of the readers evaluating it for interested editors said, “I don’t know if this is the one book about racism in Brazil that we should read. There are others that are very good.”

There’s this implication of simplicity, that if I read this one thing — I mean, how much can there really be to that culture? I’m done, you know?

JULIANA: Is there still a sense from publishers that, Oh, we have our India book for the year, we have our Japanese book for the year?

JEREMY: I’ve noticed both a kind of tokenism and a kind of herding. So I’ve had, “We have our Chinese book for the year.” But I’ve also had, during the dominance of “The Three-Body Problem,” publishers saying, “We want as much Chinese science fiction as we can get our hands on.” In both cases it’s treating books as interchangeable commodities rather than individual pieces of art that you consider on their own merits. I will say that there are more and more enlightened publishers who are able to see beyond that these days.

MUI: I haven’t had that experience, but I always fear it. After my first book, which was billed as the first Thai translation published in Britain outside of an academic press, it was like, well, are they going to want another one? I worried about that.

JULIANA: One thing I find striking is that with literature in translation, what exists in English is shaped by specific factors that are not visible to readers. Some countries, for example, fund translations from their language.

BRUNA: Publishers have such a limited budget. I’ve been really interested in books that editors said they couldn’t buy. So they will pass on it, and then instead buy a Scandinavian book or a Korean book because it got a lot of funding and they won’t have to pay out of pocket.

MUI: The playing field is definitely not level. There is some good work being done out of Anglophone countries in terms of grants, but they’re hard to come by because you’re competing with translators and translations from every language. I’ve applied for funding from Thailand a couple of times, but I have not received funding from the Thai government.

ALLISON: Despite the fact that Japanese ranks relatively high on the number of works in translation, there is actually relatively little subsidy available. None of the books that I’ve translated, or almost none of the books have really received any subsidies.

SAMANTHA: The funding tends to be quite Eurocentric, and that does have significant impact on what readers in English are offered. It’s pretty dramatic if you look at the countries that are really investing in cultural exportation.

That’s not to say that there aren’t great European writers who are worthy of being translated. There certainly are. But there are in Africa, in Asia, in Latin America as well.

ALLISON: Going back to the actual work of translation, there are a lot of interesting conversations right now about who the imagined reader is, and whether a translation should be smooth or challenging.

JEREMY: My imagined reader is myself. I translate books that I want to put out in the world because they aren’t there for me to read. And I also translate because of the process. Just as, you know, actors go after a part because it’s a great part for them and they want the experience of performing it.

BRUNA: I expect from the reader a minimum amount of curiosity, and also a bit of an ear. I want the reader to pay attention to the language, and to what I might bring from Portuguese into English. I hope they’ll get used to different voices and different accents, and appreciate all the value that’s in there. All the beauty and the language-play that’s in there, as opposed to wanting an experience that’s just going to reaffirm what they already know, who they already are.

SAMANTHA: My ideal reader is the author. I much prefer to work with an author who’s living, with whom I can have a dialogue. I’ve learned so much — not only about language, but also about the topics that the authors’ books are dealing with.

MUI: The reader I fear is the Thai reader, because they are more likely to be able to re-engineer my process. I teach at a university in Thailand, so I have students who read my translations side by side with the original. They are always sort of on one shoulder, being like, “Stay true, Mui, stay true.”

JULIANA: What brought you to this field?

MUI: Translation is just great fun, you know? The latest PEN translation manifesto emphasized how translation is a form of writing, and that for me is so true.

ALLISON: Translation is an extremely creative practice. It suits my aesthetic of creativity well. I don’t write my own work; I write translation. Working with an existing text in another language is just having different clay to mold with.

BRUNA: As a writer, I often felt like the best way for me to study any work was by translating it. It feels to my particular practice like those two are in dialogue.

But also as a person, the way I exist in the world — when I found myself as a Brazilian national in New England, suddenly my language wasn’t a part of my daily life. Translation was a way for me to put my Brazilian side and my American life in conversation, and to feel whole. So for me translation is very much a part of being truthful to who I am.

JEREMY: I grew up bilingual, biracial, I’m an immigrant, and translation is one of the few things that allow me the fluidity to explore all the areas of who I am, and not have to choose one identity or another.

#translation#Samantha Schnee#Allison Markin Powell#Jeremy Tiang#Mui Poopoksakul#Bruna Dantas Lobato#full text below the read more! if you can open the link do bc it has translator pictures

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

( jaz sinclair, woman, she/her ) — 🎬 just announced, LIV VAUGHAN has been cast as SPENCER HASTINGS in the upcoming PRETTY LITTLE LIARS reboot. the twenty six year old is trending as people are debating if the cute stickers and pins all over her bag, her perfectly curated spotify playlists, her amazing #outfits of the day, the book reviews she posts on her personal blog, that they are known for is enough to make them as good as original. a quick google search shows that their fans call them compassionate, but internet trolls think they’re more weak-willed. i guess their newest interview for variety where they talk about fans finding her old wattpad account when she was in high school will let people know them better.

basics

full name: olivia vaughan

nicknames: liv, livvy/livvie

pronouns: she/her

gender: woman

sexuality: bi

age: 26

birth date: february 9, 1998

ethnic background: black & white

height: 5'5"

known languages: english, some latin, french, italian, spanish, and portuguese, a little bit of mandarin

bullet points

hollywood is full of nepo babies whose place in the industry tends to be interrogated. liv is not one of those people. she came from a regular family in georgia, usa.

if she was gonna be special at anything, it would probably be school. but she was never a prodigy, just a geeky girl who got fairly good grades.

she had a big family. she only had a few siblings but she lived with her cousins too, and her grandparents. liv didn't stand out.

that was until she bagged an audition for the role of some big actress' daughter in the 2010s. at a very young age, liv showed remarkable talent.

so this was what she was special at. she wished she could do other things exceptionally too, but over the years she has found little success in any other field. she's a good reader, but that's not something you can monetize; she'd need to be a writer too, which she's not.

she has learned other languages but isn't good enough to be a translator or anything of the sort, she's only good enough to consume literature with added context in their original languages.

she can dress herself well, but she probably couldn't design her own clothes. she wouldn't be able to put out her own cosmetics line.

this is all that liv can do: pretend to be other people. as spencer in pll, she can act like an enterprising, motivated woman. but liv in real life only has spencer's smarts, not her fire.

liv has been in the spotlight since she was a child, and she's didn't have the wealth or connections to fall back on. so she's also internalized the need to be loved and liked. she wishes she were more assertive like spencer. but as things are, liv feels pretty spineless.

she likes to think she'll become more assertive any moment now, but she remains pretty withdrawn and shy.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nicolas Behr was born in Cuiabá in 1958 and has lived in Brasília since 1974. In 1977 Behr put out his mimeographed book, Iogurte com Farinha, the first of many. In 1978 he was arrested and prosecuted by the right-wing military dictatorship police on charges of possession of pornographic material (his poems!) and was absolved the following year. He ceased publishing between 1980 and 1993, and since then has published many small books, most of which are freely available on his website (nicolasbehr.com.br). Behr’s selected poems, Laranja Seleta, published in 2008, was a finalist for the Portugal Telecom Prize in Literature. He was the subject of a biography in 2004, a documentary film in 2010, and was invited to participate in several international festivals of literature. Behr’s most recent books, Rasília and Alcina, were published in 2020. He currently makes his living operating a greenhouse which specializes in native species of the surrounding high savannah. He loves Brasília.

-

mirror-city is a collection of new and selected poems by Nicolas Behr, imprisoned in 1978 by the Brazilian military dictatorship in an attempt to silence him and his writing. Upon release, Behr reported that his future plans included buying a megaphone so that he could speak louder.

Behr’s work summons the spectral “braxília,” the city that Brasília could have been - incorporating an X where the city’s major arteries cross into the name itself - where the “wings” and “body” meet.

mirror-city is translated by Jon Woodward and authorized by the author. The collection includes work ranging from the late 1970s to the present, as well as six new pieces.

Portuguese originals and English translations appear on facing pages.

Author: Nicolas Behr

Translator: Jon Woodward

Language: English / Portuguese

ISBN: 978-1-7375909-5-8

Release Date: October 26, 2022

#poetry#poems#poetry and poems#nicolas behr#brazil#brasilia#translation#the economy press#upcoming#anthony opal#jon woodward#poems and poetry

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call for Papers:

UCI Comparative Literature Graduate Conference 2023

“Work in Progress”

Instead of predetermining the parameters that will shape the day’s focus, the submissions are what will give it form. Our work is shaped not just by us, but also by our colleagues with whom we read, learn, and study. The trajectory of the conference will thus be produced collaboratively. During the pandemic and the strike, we have been wholly yet unexpectedly afflicted by the shortage of time, space, and capacity to think together beyond the seminar setting. With this conference, our small attempt to atone for this shortage, we invite UCI graduate students to submit any project or ideas that currently interest them.

We are open to dissertations in progress, afterthoughts, preliminary notes, and annotations. Thought left in disarray, without end, or otherwise in need of unraveling are especially welcome. Whatever might be conventionally “out of place” is at ease here. This can take the form of an academic paper, a dissertation chapter, a creative piece, reflections on a topic, amongst others.

To submit, email [email protected] a 150-300 word abstract, a title, a short bio, including your name and department, by March 28th, 2023. The event is set to take place on May, 5th 2023 and decisions are to be made at the start of April 2023. All disciplines are welcome to submit.

The conference is sponsored by the Department of Comparative Literature, the International Center for Writing and Translation, the Humanities Center, the Culture and Theory Program, the Department of European Studies, the Department of Spanish and Portuguese, and UCI Critical Theory.

0 notes

Text

“I started to wonder about the history of Latin”

This post was written by Natasha Skorupski, a Department of Classics Intern in Archives & Special Collections for the Spring of 2022.

During my internship with the Hillman library and the Classics Department of the University of Pittsburgh I worked in the Archives & Special Collections, looking over Latin manuscripts. While looking through these I started to wonder about the history of Latin and how the spoken language fell yet the written word continued.

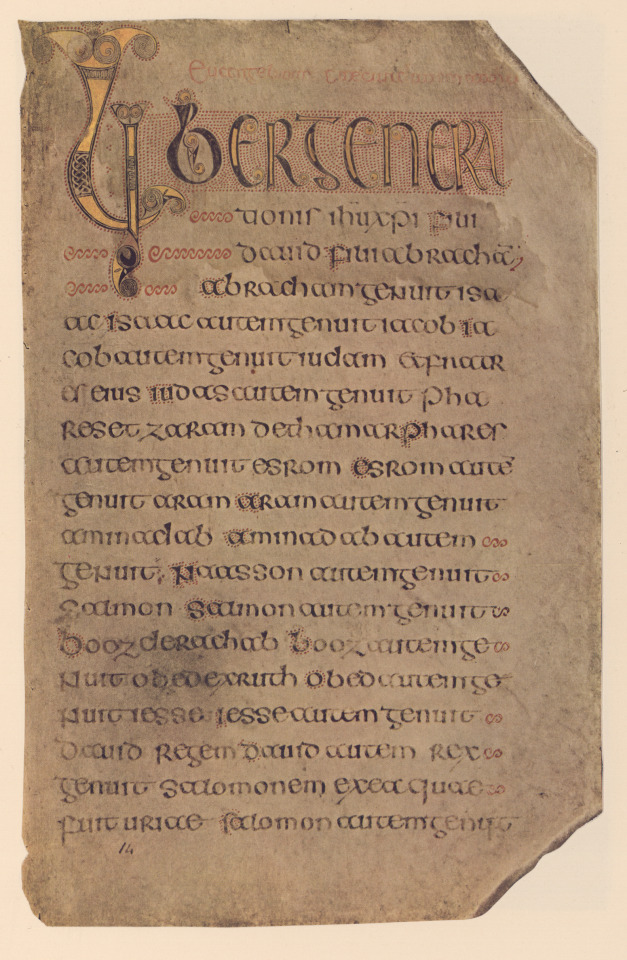

(Above) Evangeliorum quattuor Codex Durmachensis or The Book of Durrow, Olten: Urs Graf; sole distributors in the United States: P.C. Duschnes, New York by Arturus Aston Luce, 1960 facsimile. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Due to that I have found out the following information. Latin is thought to be derived from ancient Greek and Italic languages. Italy used to be made up of many different tribes that spoke many different languages, and these languages are called Italic languages today. The first evidence of Latin is an inscription on a cloak pin that was found from the sixth century BCE. On the pin it says, “Manius me fhefhaked Numasioi” which translates to “Manius made me [this] for Numerius”. The first literary records of Latin have been dated back to 250-100 BCE. The popularity of Latin increased with the rise of Roman political power. This spread was initially in Italy and then continued to most of Western Europe and parts of coastal Africa.

Latin has been classified into three groups. There is the written Latin, oratorical Latin (public speaking), and colloquial Latin (common speaking) (When Did Latin Die? and Why). The later Latin saw the greatest variation in its use and continuous divergence from it eventually evolved into Vulgar Latin. From Vulgar Latin we get the Romance Languages we know today, which include Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian.

The beginning of the end of the western Roman empire occurred in 395 CE. It fell for multiple reasons, some of them being military invasions, economic troubles, overreliance on enslaved labor, overexpansion and overspending of the military, political instability and corruption, among others (Andrews). With this fall came the decline of colloquial and Vulgar Latin.

There was a small period of resurrection for Latin under the “Roman Emperor” Charlemagne during 768-814AD. At this point in time, Latin was spoken, written, and read predominantly in religious settings as Italian, French and Spanish were rapidly evolving, allowing for a great decline of Latin (When Did Latin Die? and Why). During the mid-14th century, the Black Death Plague occurred. It killed millions of people, including numerous scholars and professors, creating a negative ripple effect on the entire education system (When Did Latin Die? and Why).

During the 15th and 16th centuries, there was another slight resurgence as people started to read Latin literature from classical authors. This was the time of the renaissance that spread mostly through Italy, France and later Britain. With the greater developments in science, Latin terminology was put into place as a way to regulate findings and encourage international research (When Did Latin Die? and Why).

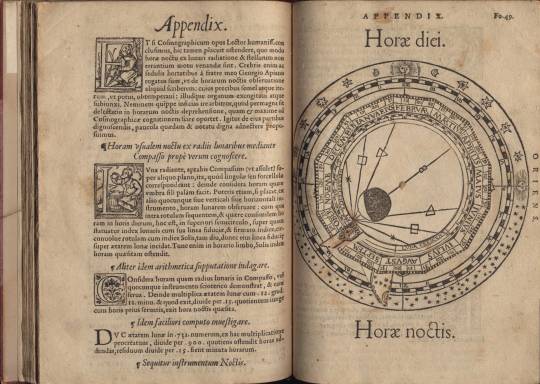

(Above) Cosmographia Petri Apiani. Antwerp: Veneunt Antuerpiæ Gregorio Bontio sub Scuto Basiliensi .. by P. & Gemma Apian, 1553. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Latin was seen as a status symbol at this point—you were seen as educated if you could read and write it. Though it was no longer spoken, it was used predominantly in literature and religion. Until the 19th century, Latin was a requirement for all that attended college. College was usually attended by white males of a privileged background (When Did Latin Die? and Why). However, this changed around the mid 1960s when the younger generation decided they also shared the right to higher education.

Today very few people can read Latin, even fewer can write it, and almost no one speaks it. However, it is one of the official languages of Vatican City and plays a vital role in Catholicism. Latin words are all over Catholic scripture and there are many recited terms that come from it (Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?).

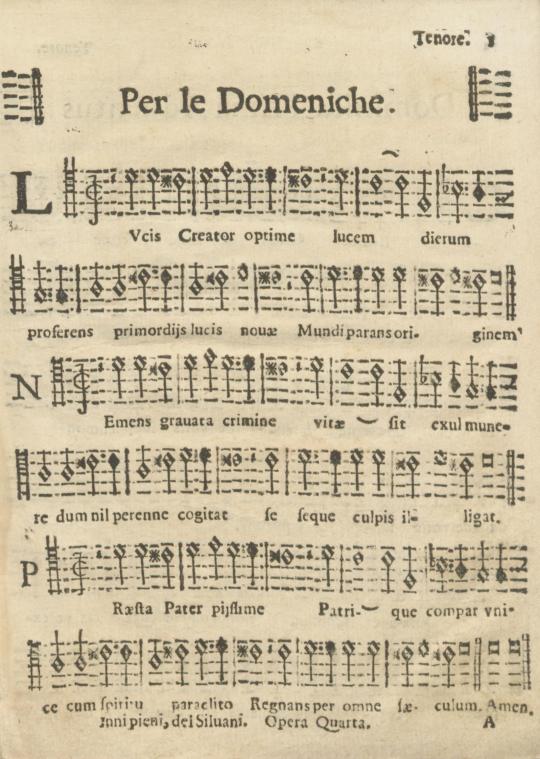

(Above) Inni sacri, per tutto l’anno : à quattro voci pieni, da cantarsi con l’organo e senza ... : opera quarta by G. A Silvani, 1705. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

A fun fact, Pope Francis is the most influential Latin speaker today with about 40 million followers between his multiple accounts that vary in languages. One of these accounts posts solely in Latin! With his bio stating “Tuus adventus in paginam publicam Papae Francisci breviloquentis optatissimus est” which roughly translates to “Your arrival to the public page of the Tweeting Pope Francis is most welcome” (Pope Francis).

Latin words also dominate in modern science as names of medicine, drugs, diseases, body parts, and it is especially used in binomial nomenclature (the system for naming plants and animals). It is also greatly prevalent in the legal field. Amicus curiae, habeas corpus, and ex post facto being just a few of the more common ones. A fun fact is the jury comes from the Latin word “jurare” meaning “to swear” (Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?).

Latin is a dead language as it is no longer spoken. However it is not extinct, and still can be encountered more than most people in the world today would expect.

Works Cited

Andrews, Evan. “8 Reasons Why Rome Fell.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 14 Jan. 2014, https://www.history.com/news/8-reasons-why-rome-fell.

“Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?” The Language Doctors, 14 Mar. 2022, https://thelanguagedoctors.org/is-latin-a-dead-language/.

Pope Francis. “Pope Francis Tweeter Account.” Twitter, Twitter, 23 Apr. 2022, https://twitter.com/pontifex_ln?lang=en.

“When Did Latin Die? and Why?” Global Language Services, Global Language Services Ltd, 3 Feb. 2022, https://www.globallanguageservices.co.uk/did-latin-die/.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

My impossible list

This list is inspired by UnJaded Jade. It is essentially a list of all of my goals and aims in life, kind of like a bucket list. I’ve split it into 6 categories: fitness/health, professional/creative, skills, academics, travel/miscellaneous and life. Here they are!

Fitness/health

Get into the habit of exercising every morning (a Chloe Ting video, perhaps?)

Complete the couch to 5K challenge

Complete the Chloe Ting two week shred challenge

Reach and maintain a healthy weight

Learn how to cook traditional family meals

Professional/creative

Write and publish several novels

Find a job that involves languages, travel and creating a positive change in the world that you enjoy

Start a YouTube channel about language learning

Learn how to do calligraphy

Reach 1000 followers on this blog.

Skills

Speak fluent (C1/C2) French, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, Arabic, German, Russian, Japanese, Portuguese, Korean, Tamil, Hindi, Urdu and Bengali

Be able to understand and translate literature in ancient greek and latin

Learn how to play basic piano

Learn how to play basic guitar

Self study architecture (the theory anyway), history, medicine (not to practice), world literature, marxism, linguistics and classics

Academics

Achieve 3 A*s in A-levels (French, English literature and history)

Get a first in a liberal arts degree (Mandarin Chinese, Russian, English literature and international relations)

Do a dissertation analysing Marx from a linguistic perspective

Win an English literature A-level essay competions

Travel/miscellaneous

Spend Gap year in Yemen

Visit Japan

Speak at the polyglot conference

Abseil down a waterfall

Go on Hajj

Life

Mantain a healthy physical and mental state

Get married and have kids (raise your kids multilingual)

Re-connect with deen and religion

So that’s it! That’s my impossible list. Thanks for reading this post!

#study motivation#studyblr#langblr#goals#goal setting#unjaded jade#travel#fitness#polyglot#aspiring polyglot#wonderlust

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

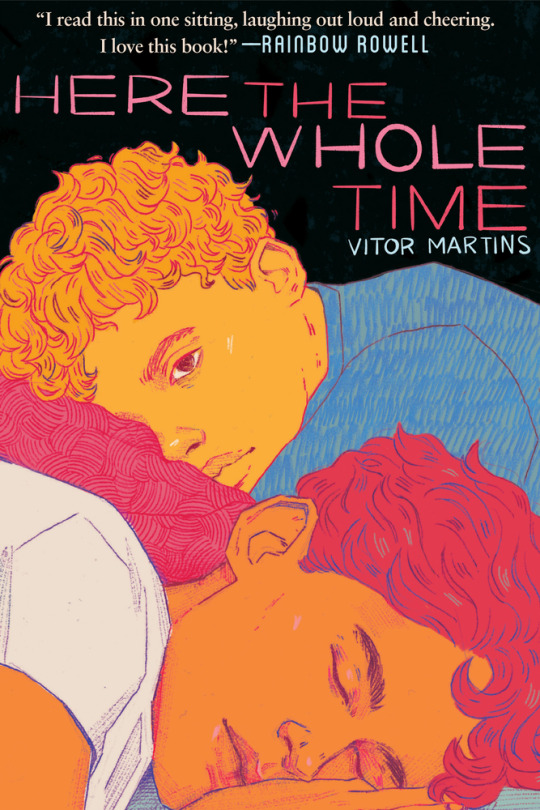

Reading Beyond the U.S.

Earlier this year I saw a thought-provoking video from a BookTuber named Saajid considering the question, "Is the book community American-centric?" I've been pondering things Saajid mentioned in the video for several months. On our blog we're definitely trying to read and recommend books that are from a wide variety of creators, but when I examine my personal reading history, the books are indeed mostly American-centric. Over the past few years, I've read a few titles in the list below, but I’m starting to make more of an effort to read books from other areas of the world.

One resource I found helpful in my search for titles is the Global Literature in Libraries Initiative. It led me to Here the Whole Time which is a book I really enjoyed. The author, Vitor Martins, lives in Brazil and the book was translated from Portuguese by Larissa Helena. I would love to see more translations getting attention. One of the organizations trying to make that happen is Project World Kid Lit. They have many helpful resources for finding, discussing, and encouraging the use of translated children's and YA literature.

Here are titles of books set in countries beyond the U.S. and the Global North with a few links to resources to find more. Some of the authors no longer live in the places where these books are set, but grew up there. If you have other titles to recommend or know of other resources for finding International titles, please let us know.

South Korea - b, Book and Me by Kim Sagwa translated by Sunhee Jeong & Banned Book Club by Kim Hyun Sook, Ryan Estrada & Hyung-Ju Ko

North Korea - Every Falling Star: The Story of How I Survived and Escaped North Korea* by Sungju Lee and Susan Elizabeth McClelland

India - I was excited to find an article by Prasanna Sawant at The (Curious) Reader which traces the development of Indian YA literature and includes many titles. The site focuses on Indian lit, but also includes other world literature for all ages.

Sri Lanka - Swimming in the Monsoon Sea* by Shyam Selvadurai

Malaysia - Kampung Boy by Lat & The Weight of Our Sky by Hanna Alkaf

Burt Award for African Young Adult Literature (Lists from 2017-2018)

Ghana - Aluta* by Adwoa Badoe

Zimbabwe - Hope is Our Only Wing* by Rutendo Tavengerwei

Ivory Coast - Aya: Life in Yop City Marguerite Abouet

Bahamas - Learning to Breathe* by Janice Lynn Mather

Central America - The Other Side: Stories of Central American Teen Refugees Who Dream of Crossing the Border* by Juan Pablo Villalobos

Trinidad and Tobago - Dreams Beyond the Shore* by Tamika Gibson

Argentina - Furia by Yamile Saied Méndez

Dominican Republic - Before We Were Free by Julia Alvarez

Brazil - Where We Go From Here* by Lucas Rocha & Here the Whole Time by Vitor Martins both translated by Larissa Helena

Multi-national - Girlhood: Teens Around the World by Masuma Ahuja

*They're on my TBR, but I don't have enough knowledge about the titles to recommend them or not.

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

what do you think of the whole actor in shrine situation? is this why you're moving away from s/h//l?

lol

A medieval fisherman is said to have hauled up a three-foot-long cod, which was common enough at the time. And the fact that the cod could talk was not especially surprising. But what was astonishing was that it spoke an unknown language. It spoke Basque.

This Basque folktale shows not only the Basque attachment to their orphan language, indecipherable to the rest of the world, but also their tie to the Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua, a fish that has never been found in Basque or even Spanish waters.

The Basques are enigmatic. They have lived in what is now the northwest corner of Spain and a nick of the French southwest for longer than history records, and not only is the origin of their language unknown, but the origin of the people themselves remains a mystery also. According to one theory, these rosy-cheeked, dark-haired, long-nosed people were the original Iberians, driven by invaders to this mountainous corner between the Pyrenees, the Cantabrian Sierra, and the Bay of Biscay. Or they may be indigenous to this area.

They graze sheep on impossibly steep, green slopes of mountains that are thrilling in their rare, rugged beauty. They sing their own songs and write their own literature in their own language, Euskera. Possibly Europe’s oldest living language, Euskera is one of only four European languages—along with Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian—not in the Indo-European family. They also have their own sports, most notably jai alai, and even their own hat, the Basque beret, which is bigger than any other beret.

Though their lands currently reside in three provinces of France and four of Spain, Basques have always insisted that they have a country, and they call it Euskadi. All the powerful peoples around them—the Celts and Romans, the royal houses of Aquitaine, Navarra, Aragon, and Castile; later Spanish and French monarchies, dictatorships, and republics—have tried to subdue and assimilate them, and all have failed. In the 1960s, at a time when their ancient language was only whispered, having been outlawed by the dictator Francisco Franco, they secretly modernized it to broaden its usage, and today, with only 800,000 Basque speakers in the world, almost 1,000 titles a year are published in Euskera, nearly a third by Basque writers and the rest translations.

“Nire aitaren etxea / defendituko dut. / Otsoen kontra” (I will defend / the house of my father. / Against the wolves) are the opening lines of a famous poem in modern Euskera by Gabriel Aresti, one of the fathers of the modernized tongue. Basques have been able to maintain this stubborn independence, despite repression and wars, because they have managed to preserve a strong economy throughout the centuries. Not only are Basques shepherds, but they are also a seafaring people, noted for their successes in commerce. During the Middle Ages, when Europeans ate great quantities of whale meat, the Basques traveled to distant unknown waters and brought back whale. They were able to travel such distances because they had found huge schools of cod and salted their catch, giving them a nutritious food supply that would not spoil on long voyages.

Basques were not the first to cure cod. Centuries earlier, the Vikings had traveled from Norway to Iceland to Greenland to Canada, and it is not a coincidence that this is the exact range of the Atlantic cod. In the tenth century, Thorwald and his wayward son, Erik the Red, having been thrown out of Norway for murder, traveled to Iceland, where they killed more people and were again expelled. About the year 985, they put to sea from the black lava shore of Iceland with a small crew on a little open ship. Even in midsummer, when the days are almost without nightfall, the sea there is gray and kicks up whitecaps. But with sails and oars, the small band made it to a land of glaciers and rocks, where the water was treacherous with icebergs that glowed robin’s-egg blue. In the spring and summer, chunks broke off the glaciers, crashed into the sea with a sound like thunder that echoed in the fjords, and sent out huge waves. Eirik, hoping to colonize this land, tried to enhance its appeal by naming it Greenland.

Almost 1,000 years later, New England whalers would sing: “Oh, Greenland is a barren place / a place that bears no green / Where there’s ice and snow / and the whale fishes blow / But daylight’s seldom seen.”

Eirik colonized this inhospitable land and then tried to push on to new discoveries. But he injured his foot and had to be left behind. His son, Leifur, later known as Leif Eiriksson, sailed on to a place he called Stoneland, which was probably the rocky, barren Labrador coast. “I saw not one cartload of earth, though I landed many places,” Jacques Cartier would write of this coast six centuries later. From there, Leif’s men turned south to “Woodland” and then “Vineland.” The identity of these places is not certain. Woodland could have been Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, or Maine, all three of which are wooded. But in Vineland they found wild grapes, which no one else has discovered in any of these places.

The remains of a Viking camp have been found in Newfoundland. It is perhaps in that gentler land that the Vikings were greeted by inhabitants they found so violent and hostile that they deemed settlement impossible, a striking assessment to come from a people who had been regularly banished for the habit of murdering people. More than 500 years later the Beothuk tribe of Newfoundland would prevent John Cabot from exploring beyond crossbow range of his ship. The Beothuk apparently did not misjudge Europeans, since soon after Cabot, they were enslaved by the Portuguese, driven inland, hunted by the French and English, and exterminated in a matter of decades.

How did the Vikings survive in greenless Greenland and earthless Stoneland? How did they have enough provisions to push on to Woodland and Vineland, where they dared not go inland to gather food, and yet they still had enough food to get back? What did these Norsemen eat on the five expeditions to America between 985 and 1011 that have been recorded in the Icelandic sagas? They were able to travel to all these distant, barren shores because they had learned to preserve codfish by hanging it in the frosty winter air until it lost four-fifths of its weight and became a durable woodlike plank. They could break off pieces and chew them, eating it like hardtack. Even earlier than Eirik’s day, in the ninth century, Norsemen had already established plants for processing dried cod in Iceland and Norway and were trading the surplus in northern Europe.

The Basques, unlike the Vikings, had salt, and because fish that was salted before drying lasted longer, the Basques could travel even farther than the Vikings. They had another advantage: The more durable a product, the easier it is to trade. By the year 1000, the Basques had greatly expanded the cod markets to a truly international trade that reached far from the cod’s northern habitat.

In the Mediterranean world, where there were not only salt deposits but a strong enough sun to dry sea salt, salting to preserve food was not a new idea. In preclassical times, Egyptians and Romans had salted fish and developed a thriving trade. Salted meats were popular, and Roman Gaul had been famous for salted and smoked hams. Before they turned to cod, the Basques had sometimes salted whale meat; salt whale was found to be good with peas, and the most prized part of the whale, the tongue, was also often salted.

Until the twentieth-century refrigerator, spoiled food had been a chronic curse and severely limited trade in many products, especially fish. When the Basque whalers applied to cod the salting techniques they were using on whale, they discovered a particularly good marriage because the cod is virtually without fat, and so if salted and dried well, would rarely spoil. It would outlast whale, which is red meat, and it would outlast herring, a fatty fish that became a popular salted item of the northern countries in the Middle Ages.

Even dried salted cod will turn if kept long enough in hot humid weather. But for the Middle Ages it was remarkably long-lasting—a miracle comparable to the discovery of the fast-freezing process in the twentieth century, which also debuted with cod. Not only did cod last longer than other salted fish, but it tasted better too. Once dried or salted—or both—and then properly restored through soaking, this fish presents a flaky flesh that to many tastes, even in the modern age of refrigeration, is far superior to the bland white meat of fresh cod. For the poor who could rarely afford fresh fish, it was cheap, high-quality nutrition.

In 1606, Gudbrandur Thorláksson, an Icelandic bishop, made this line drawing of the North Atlantic in which Greenland is represented in the shape of a dragon with a fierce, toothy mouth. Modern maps show that this is not at all the shape of Greenland, but it is exactly what it looks like from the southern fjords, which cut jagged gashes miles deep into the high mountains. (Royal Library, Copenhagen)

Catholicism gave the Basques their great opportunity. The medieval church imposed fast days on which sexual intercourse and the eating of flesh were forbidden, but eating “cold” foods was permitted. Because fish came from water, it was deemed cold, as were waterfowl and whale, but meat was considered hot food. The Basques were already selling whale meat to Catholics on “lean days,” which, since Friday was the day of Christ’s crucifixion, included all Fridays, the forty days of Lent, and various other days of note on the religious calendar. In total, meat was forbidden for almost half the days of the year, and those lean days eventually became salt cod days. Cod became almost a religious icon—a mythological crusader for Christian observance.

The Basques were getting richer every Friday. But where was all this cod coming from? The Basques, who had never even said where they came from, kept their secret. By the fifteenth century, this was no longer easy to do, because cod had become widely recognized as a highly profitable commodity and commercial interests around Europe were looking for new cod grounds. There were cod off of Iceland and in the North Sea, but the Scandinavians, who had been fishing cod in those waters for thousands of years, had not seen the Basques. The British, who had been fishing for cod well offshore since Roman times, did not run across Basque fishermen even in the fourteenth century, when British fishermen began venturing up to Icelandic waters. The Bretons, who tried to follow the Basques, began talking of a land across the sea.

Bench ends from St. Nicolas’ Chapel in a town by the North Sea, King’s Lynn, Norfolk, England, carved circa 1415, depict the cod fishery. (Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

In the 1480s, a conflict was brewing between Bristol merchants and the Hanseatic League. The league had been formed in thirteenth-century Lübeck to regulate trade and stand up for the interests of the merchant class in northern German towns. Hanse means “fellowship” in Middle High German. This fellowship organized town by town and spread throughout northern Europe, including London. By controlling the mouths of all the major rivers that ran north from central Europe, from the Rhine to the Vistula, the league was able to control much of European trade and especially Baltic trade. By the fourteenth century, it had chapters as far north as Iceland, as far east as Riga, south to the Ukraine, and west to Venice.

For many years, the league was seen as a positive force in northern Europe. It stood up against the abuses of monarchs, stopped piracy, dredged channels, and built lighthouses. In England, league members were called Easterlings because they came from the east, and their good reputation is reflected in the word sterling, which comes from Easterling and means “of assured value.”

But the league grew increasingly abusive of its power and ruthless in defense of trade monopolies. In 1381, mobs rose up in England and hunted down Hanseatics, killing anyone who could not say bread and cheese with an English accent.

The Hanseatics monopolized the Baltic herring trade and in the fifteenth century attempted to do the same with dried cod. By then, dried cod had become an important product in Bristol. Bristol’s well-protected but difficult-to-navigate harbor had greatly expanded as a trade center because of its location between Iceland and the Mediterranean. It had become a leading port for dried cod from Iceland and wine, especially sherry, from Spain. But in 1475, the Hanseatic League cut off Bristol merchants from buying Icelandic cod.

Thomas Croft, a wealthy Bristol customs official, trying to find a new source of cod, went into partnership with John Jay, a Bristol merchant who had what was at the time a Bristol obsession: He believed that somewhere in the Atlantic was an island called Hy-Brasil. In 1480, Jay sent his first ship in search of this island, which he hoped would offer a new fishing base for cod. In 1481, Jay and Croft outfitted two more ships, the Trinity and the George. No record exists of the result of this enterprise. Croft and Jay were as silent as the Basques. They made no announcement of the discovery of Hy-Brasil, and history has written off the voyage as a failure. But they did find enough cod so that in 1490, when the Hanseatic League offered to negotiate to reopen the Iceland trade, Croft and Jay simply weren’t interested anymore.

Where was their cod coming from? It arrived in Bristol dried, and drying cannot be done on a ship deck. Since their ships sailed out of the Bristol Channel and traveled far west of Ireland and there was no land for drying fish west of Ireland—Jay had still not found Hy-Brasil—it was suppposed that Croft and Jay were buying the fish somewhere. Since it was illegal for a customs official to engage in foreign trade, Croft was prosecuted. Claiming that he had gotten the cod far out in the Atlantic, he was acquitted without any secrets being revealed.

To the glee of the British press, a letter has recently been discovered. The letter had been sent to Christopher Columbus, a decade after the Croft affair in Bristol, while Columbus was taking bows for his discovery of America. The letter, from Bristol merchants, alleged that he knew perfectly well that they had been to America already. It is not known if Columbus ever replied. He didn’t need to. Fishermen were keeping their secrets, while explorers were telling the world. Columbus had claimed the entire new world for Spain.

Then, in 1497, five years after Columbus first stumbled across the Caribbean while searching for a westward route to the spice-producing lands of Asia, Giovanni Caboto sailed from Bristol, not in search of the Bristol secret but in the hopes of finding the route to Asia that Columbus had missed. Caboto was a Genovese who is remembered by the English name John Cabot, because he undertook this voyage for Henry VII of England. The English, being in the North, were far from the spice route and so paid exceptionally high prices for spices. Cabot reasoned correctly that the British Crown and the Bristol merchants would be willing to finance a search for a northern spice route. In June, after only thirty-five days at sea, Cabot found land, though it wasn’t Asia. It was a vast, rocky coastline that was ideal for salting and drying fish, by a sea that was teeming with cod. Cabot reported on the cod as evidence of the wealth of this new land,

New Found Land, which he claimed for England. Thirty-seven years later, Jacques Cartier arrived, was credited with “discovering” the mouth of the St. Lawrence, planted a cross on the Gaspé Peninsula, and claimed it all for France. He also noted the presence of 1,000 Basque fishing vessels. But the Basques, wanting to keep a good secret, had never claimed it for anyone.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Semi-coherent thoughts on Foucault’s Pendulum

So I do semi-regularly attempt to become Cultured and ever-so-slowly work my way through my vague impression of what the canon is, and so I ended up grabbing a title from the back of my memory and ordering it at the bookstore (which is also where I learned that their are actually different shelves for ‘fiction’ and ‘literature’, which is just so self-evidently meaningless and arbitrary it made me smile). And honestly it actually really did live up to the hype! Both in that I thoroughly enjoyed it and in that it made me feel like a half-educated imbecile as I read.

Really, going in with basically no idea of what to expect, I was really quite pleasantly surprised by how utterly, gleefully bizarre the story is. Like, really, remove the synopsis on the back of the book from all context and it sounds like some too-clever-by-half internet serial or pulpy airport novel (not to disparage either of those extremely valuable artforms). What with all the mind-altering substances and international travel and occult conspiracies and mysterious dissonances, I mean.

The prose was really just lovely throughout, if rather more literary than I’m used to at this point. There’s a distant, vaguely unreal feeling to a lot of the narrative, between the fantastical conspiracy theories and occultism and mind altering substances and the protagonist’s crumbling sense of reality and growing obsession, and beyond that all the different unreliable narrators taking turns giving their own grand monologues and stories (beyond that, some it is surely the inevitable result of the translation from the Italian). Speaking of – Eco manages the somewhat incredible task of keeping the main narrators really distinct with their own voices (though after some of Belbo’s more ‘romantic’ pieces you did vaguely feel like you need a shower. And vaguely offended Lorenza never gets a chance to speak for herself, which I’m sure is part of a point somewhere).

I was totally unprepared for how [i]funny[/i] the book ended up being, at least large stretched of it. Or, well, @explodingsilver described it as ‘Sensible Chuck: the book’, and they’re really not wrong. The whole explanation of the Mantuis business model seemed like something out of Prachett (if, also, really quite plausible).

I joked before about wanting an annotated edition with a reader’s guide, but, like, at the absolute least I really would have appreciated the untranslated passages in French/Latin/German/Portuguese had a footnote with their meaning at the bottom of the page, for us unsophisticated philistines in the audience. Though really the book was a pretty helpful crash course in all the really classic conspiracy theories – I honestly hadn’t known what the story behind the templars being such a fixture in the paranoid imagination was, and had never heard of what the Rosicrucians were beyond the name. (It’s honestly slightly funny, I’m re-listening to the History of the Crusades podcast and had gotten to the episode on the siege of Ascalon, like, the day before I read about it in this).

I know that ‘all the ‘60s revolutionaries gave up or sold out and traded in their dialectical materialism for conspiracy theories and new age woo’ is something of a cliche by now, but it is kind of interesting to read about the transition as an important part of the narrative. I’m sure it’s just Eco’s style, but it was also rather amusing when the narration would politely talk around the Diabolical’s being obvious fascist.

The actual central plot – the Plan, the Diabolicals, the gradual transition from mockery to sincerity in constructing their model of the world, and all the big reveals and the climax were just really excellently done and lovely to read. Entirely different scenes I know, but slightly surprised the Da Vinci Code post-dates this by nearly twenty years, given how brutally it (deconstructs? Satirizes? I’m too tired to remember the specific term) the whole conceit.

Though really, antisemitism aside all the grand Templar and Masonic and Rosicrucian conspiracies seem almost quaint compared to the modern iterations. Or maybe the hay cart will be tied into Quanon next week and I’m just being naive about how bizarre they can get.

But anyway, yes, excellent book, would absolutely recommend.

#books#book review#Foucault's Pendulum#Umberto Eco#this is theoretically a writing blog#in this essay I will#forgot to post this last week#so

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An exquisitely early English translation of the siddur, according to the Sephardic rite, London, circa 1730-1750

581 pages (195 x 156 mm) on paper; written in English

One of a small group of manuscripts representing the earliest known translation of the Sephardic siddur into English.

The present lot is a remarkable document that tells a rich and complex tale of linguistic assimilation, religious devotion, and communal censorship. The story begins with the expulsion of the Jews from England under Edward I in 1290 and their unofficial resettlement there in the mid-seventeenth century. In 1664, ex-conversos and Sephardic Jews from the Canary Islands, Amsterdam, the Iberian Peninsula, and elsewhere ratified a set of bylaws that served as the governing documents of their newly-organized Congregation of Spanish and Portuguese Jews in London. One of these founding articles reads (in English translation) as follows:

“No Jew shall be allowed to cause to be printed in this city or outside it in these realms Hebrew or Ladino books or [books] in any other language without express permission of the Mahamad [communal governing authority] so that they be revised and emended; and him who should contravene this Escama [accord] we straightway hold as subject to the penalty of Herrem [excommunication], because it thus conduces to our preservation.”

The community’s restrictive publication policies were born of concerns both internal and external. Since many of its members were descended from, or themselves, New Christians who had reverted to Judaism, their ideas about religious belief and practice did not always conform with the orthodoxies of Jewish tradition. Moreover, the tenuous political position of Jews living in a country that, even today, has yet to officially rescind its medieval Edict of Expulsion meant that the community’s authorities could not allow anything potentially offensive to the Church or the Crown to emanate from their midst.

Naturally, the Sephardic leadership was committed to cultivating and buttressing religious observance among the Jewish public. To this end, like some of their Orthodox Ashkenazic cousins in the nineteenth century, they adopted a strict, hierarchical linguistic policy as a bulwark against assimilation. Hebrew was reserved for established ritual, Spanish for religious literature and certain religious functions, and Portuguese for management and administration of the congregation’s affairs. In addition, Spanish was used as a language of translation; the first English Jew to render the Sephardic liturgy in an authorized Spanish version was Haham (Chief Rabbi) Ishac Nieto (1687-1773), in 1740 (Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur prayers) and 1771 (daily, New Moon, Hanukkah, and Purim prayers). English, by contrast, was used primarily in the community’s communications with gentile society, not internally.

With time, however, Spanish proved incapable of serving the needs of successive generations of English-born Jews who did not understand the Hebrew original of the prayer book. In the first half of the eighteenth century, efforts were therefore made to render the Sephardic siddur in English. Famously, Nieto’s scholarly brother Moseh (d. 1741) attempted to publish an English translation of the liturgy in London in early 1734. When his intentions came to the Mahamad’s attention, Nieto was sanctioned and ordered to turn over the original plates of the book so that it could not be printed. The primary problem with Nieto’s actions (aside from his failure to apply to the Mahamad for a license) may have been the language into which he sought to translate, for a request by him later that year to publish a Spanish version of “the books of monthly and yearly prayers” met with the Mahamad’s approval.

While Nieto’s English and Spanish siddurim never saw the light of print, the present work seemingly represents an earlier attempt to make the Sephardic liturgy available in the local vernacular. Together with two other codices held by the John Rylands Library in Manchester and the London Metropolitan Archives, it forms a small family of manuscripts rendering the principal daily, Sabbath, New Moon, and festival prayers into English. A fourth exemplar, whose current whereabouts are unknown but which is mentioned by the scholar of Anglo-Jewish liturgical translation history Simeon Singer in an article published at the end of the nineteenth century, was localized and dated “London, 1729, 23rd August,” attesting that this translation existed already four and a half years before Nieto’s publishing (misad)venture. The translation, which Singer characterizes as “marked in many passages by a certain vigour of style and quaintness of phraseology,” appears to have been forced to circulate exclusively in manuscript because of the community’s tight control over printing licenses.[x]

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, yeah, uh, I am alive! I missed a bunch of Wednesdays and Fridays... But something is coming, and I am really excited about it! It won’t be too long now...

Also, for all the missed snippets I owe you I will give you something long-ish from something called “Literature AU” I started long ago and may not ever finish. This whole conversation (and almost the whole AU, really) was inspired by the excellent a measure of stars by @lepetitepeach (in the process of being translated into Portuguese by @awake-dreamer18). This snippet consists almost exclusively of test messages, but I am not nifty enough to make it look nice, so you’ll have to deal with it as is.

~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~ ~~~~~

Lucas

Why are all these literary characters so absolutely drab?

Eliott could not let Lucas make such blatantly false statements unchallenged.

Eliott

Are you insane? They are anything but! Most of them are written so delicately, full of details and intricacies and complexities, with conflicting emotions and ideals and interests, battling internal and external demons – just like real people! Remember how Antigone had to weigh up the love for her sister, her uncle, her fiancé with the love for her brother? How can you decide which love is bigger, Lucas? That’s not drab!

Lucas

Uh.

Okay, sorry.

You are right.

Wow, you’re really passionate about this, aren’t you?

😉

I’ll agree they are not drab.

Just so… unrelatable?

Eliott

Some, maybe. But most of them are human just like all of us. Surely you can relate to some of them? What are you reading now?

Lucas

“Reading” is maybe too big a word.

But I am leafing through the summary of Pride and Prejudice.

Ugh. Stupid Elisabeth.

And what’s the deal about Mr Darcy anyway?

Everybody loves him because he’s rich?

Very superficial, Eliott.

Eliott

… Maybe read the actual book, Lucas. Elisabeth doesn’t love Mr. Darcy because he’s rich, but because he is honourable, and caring, and kind, and not trying to control her.

Lucas

Okay.

But still.

I don’t see the appeal myself.

They should really have a gay guy look into this.

Eliott

Huh?

Lucas

A gay guy, Eliott.

Straighties don’t understand the appeal of any man, and women are obviously not right in the head to fawn over Mr. Darcy like that.

So we need a gay’s perspective.

Eliott

Well, I’m not straight, do I count?

Lucas

Oh.

Sorry.

You’re not?

Eliott

No. Is that a problem?

Lucas

In case it wasn’t clear from my previous texts, I’m gay.

So not a problem.

I just thought Imane said something about a girlfriend.

Eliott

You and Imane talked about me?

Lucas

No!

Uhm, no.

Just came up, I guess.

But, no girlfriend then?

Eliott

An ex-girlfriend. I’m pan.

Lucas

Oh.

Okay.

Well.

Then you see the need for a non-straight perspective.

Eliott

I suppose you might be right. Although there are some gay writers featured in the course. Oscar Wilde, for example.

Lucas

Did he write about any gay characters?

Eliott

Not in so many words. Maybe you have a point.

Lucas

Eliott, my dear friend, you should have realized by now I usually have.

So, gay Pride and prejudice?

You in?

I mean…

We should write it.

I’m sure we’d make it so much better.

Eliott

You haven’t even read the book, Lucas. I don’t think you’re qualified to judge whether our hypothetical gay version would be any better.

Lucas

Is that your way of saying you don’t want to work on it with me?

Come on, Eliott!

I’m hurt.

I already have the proud and prejudiced down!

All you’d have to do is actually write the book.

You could use my dating life as inspiration.

It’s worse than Elizabeth Bennet’s.

Gay P&P might be a horror story.

#i write things#literature AU#making up for all the missed#Writer's Choice Wednesday#Fan Choice Friday

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOMINANT THEMES AND STYLES LITERATURE

SOUTH EAST ASIA

This area, which embraces the region south of China and east of India, includes the modern nations of Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, The Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. The earliest historical influence came from India around the beginnings of the Christian era. At a later period, Buddhism reached mainland Southeast Asia. Its influence was a major source of traditional literature in the Buddhist countries of Southeast Asia. Vietnam, under Chinese rule, was influenced by Chinese and Indian literature. Indonesia and Malaysia were influenced by Islam and its literature. All of the countries, except for Thailand, underwent a colonial experience and each of the countries reflects in its literature and in other aspects of its culture the influence of the colonizing power, including the language of that power. Education in the foreign language was to bring with it an introduction to a foreign literature and this, in turn, was to have considerable impact upon their modern forms of literary expression. One finds, then, all the well-known literary genres of Western literature, the novel, the short story, the play, and the essay. Poetry had been the most popular form of the traditional literature over the centuries but was rigid in form. However, through increased acquaintance with Western poetry, the poets of Southeast Asia broke the bonds of tradition and began to imitate various poetic types. A reading list of books is included.

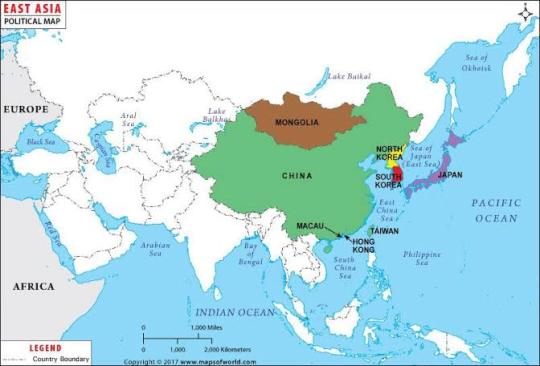

EAST ASIA

Thinkers of the East is a collection of anecdotes and ‘parables in action’ illustrating the eminently practical and lucid approach of Eastern Dervish teachers.

Distilled from the teachings of more than one hundred sages in three continents, this material stresses the experimental rather than the theoretical – and it is that characteristic of Sufi study which provides its impact and vitality.

The emphasis of Thinkers of the East contrasts sharply with the Western concept of the East as a place of theory without practice, or thought without action. The book’s author, Idries Shah, says ‘Without direct experience of such teaching, or at least a direct recording of it, I cannot see how Eastern thought can ever be understood’.

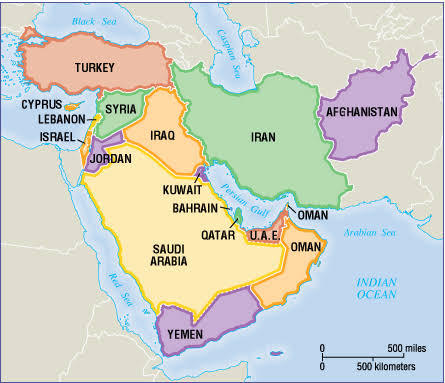

SOUTH AND WEST ASIA

Chicana/o literature is justly acclaimed for the ways it voices opposition to the dominant Anglo culture, speaking for communities ignored by mainstream American media. Yet the world depicted in these texts is not solely inhabited by Anglos and Chicanos; as this groundbreaking new book shows, Asian characters are cast in peripheral but nonetheless pivotal roles.

Southwest Asia investigates why key Chicana/o writers, including Américo Paredes, Rolando Hinojosa, Oscar Acosta, Miguel Méndez, and Virginia Grise, from the 1950s to the present day, have persistently referenced Asian people and places in the course of articulating their political ideas. Jayson Gonzales Sae-Saue takes our conception of Chicana/o literature as a transnational movement in a new direction, showing that it is not only interested in North-South migrations within the Americas, but is also deeply engaged with East-West interactions across the Pacific. He also raises serious concerns about how these texts invariably marginalize their Asian characters, suggesting that darker legacies of imperialism and exclusion might lurk beneath their utopian visions of a Chicana/o nation.

Southwest Asia provides a fresh take on the Chicana/o literary canon, analyzing how these writers have depicted everything from interracial romances to the wars Americans fought in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. As it examines novels, plays, poems, and short stories, the book makes a compelling case that Chicana/o writers have long been at the forefront of theorizing U.S.–Asian relations.

ANGLO -AMERICA AND EUROPE

ANGLO - AMERICA

The Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections has considerable holdings in Anglo-American literature from the 17th century onward, with notable strengths in the 18th century, Romanticism, and the Victorian and modern periods. Among the seventeenth-century holdings is a complete set of the Shakespeare folios, and works by John Milton and his contemporaries. Eighteenth-century highlights include near comprehensive printed collections of Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope, and substantial holdings on John Dryden, Samuel Johnson, Joseph Addison, Sir Richard Steele, William Cowper, Fanny Burney, and others. Related materials include complete runs of periodicals, such as the Spectator and the Tatler.

EUROPE

The history of European literature and of each of its standard periods can be illuminated by comparative consideration of the different literary languages within Europe and of the relationship of European literature to world literature. The global history of literature from the ancient Near East to the present can be divided into five main, overlapping stages. European literature emerges from world literature before the birth of Europe—during antiquity, whose classical languages are the heirs to the complex heritage of the Old World. That legacy is later transmitted by Latin to the various vernaculars. The distinctiveness of this process lies in the gradual displacement of Latin by a system of intravernacular leadership dominated by the Romance languages. An additional unique feature is the global expansion of Western Europe’s languages and characteristic literary forms, especially the novel, beginning in the Renaissance.This expansion ultimately issues in the reintegration of European literature into world literature, in the creation of today’s global literary system. It is in these interrelated trajectories that the specificity of European literature is to be found. The ongoing relationship of European literature to other parts of the world emerges most clearly at the level not of theme or mimesis but of form. One conclusion is that literary history possesses a certain systematicity. Another is that language and literature are not only the products of major historical change but also its agents. Such claims, finally, depend on rejecting the opposition between the general and the specific, between synthetic and local knowledge.

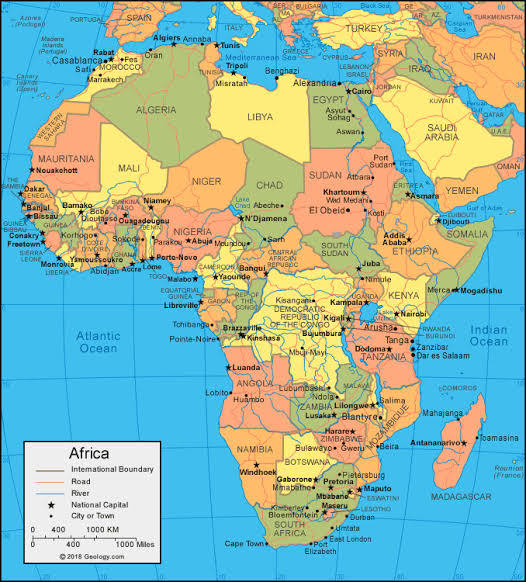

Africa

African literature has origins dating back thousands of years to Ancient Egypt and hieroglyphs, or writing which uses pictures to represent words. These Ancient Egyptian beginnings led to Arabic poetry, which spread during the Arab conquest of Egypt in the seventh century C.E. and through Western Africa in the ninth century C.E. These African and Arabic cultures continued to blend with the European culture and literature to form a unique literary form.

Africa experienced several hardships in its long history which left an impact on the themes of its literature. One hardship which led to many others is that of colonization. Colonization is when people leave their country and settle in another land, often one which is already inhabited. The problem with colonization is when the incoming people exploit the indigenous people and the resources of the inhabited land.

Colonization led to slavery. Millions of African people were enslaved and brought to Western countries around the world from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. This spreading of African people, largely against their will, is called the African Diaspora.

Sub-Saharan Africa developed a written literature during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This development came as a result of missionaries coming to the area. The missionaries came to Africa to build churches and language schools in order to translate religious texts. This led to Africans writing in both European and indigenous languages.

Though African literature's history is as long as it is rich, most of the popular works have come out since 1950, especially the noteworthy Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe. Looking beyond the most recent works is necessary to understand the complete development of this collection of literature

LATIN AMERICA

Latin American literature consists of the oral and written literature of Latin America in several languages, particularly in Spanish, Portuguese, and the indigenous language of America as well as literature of the United States written in the Spanish language. It rose to particular prominence globally during the second half of the 20th century, largely due to the international success of the style known as magical realism. As such, the region's literature is often associated solely with this style, with the 20th Century literary movement known as Latin American Boom, and with its most famous exponent, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Latin American literature has a rich and complex tradition of literary production that dates back many centuries

Bocar, Mark Jason P.

Stem 11- St. Alypius

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long, unedited text in which I rant about comparative mythology, Joseph Campbell and his monomyth,

Back in 2012 I wanted to improve my fiction writing (and writing in general, because in spite of nuances, themes and audience, writing a fiction and a nonfiction piece shouldn’t be that different) and thus I picked a few writing manuals. Many of them cited the Hero’s Journey, and how important it became for writers – after all Star Wars used and it worked. I believe most of the people reading this like Star Wars, or at least has neutral feelings about it, but one thing that cannot be denied is that became a juggernaut of popular culture.

So I bought a copy of the Portuguese translation of The Hero of a Thousand Faces and I fell in love with the style. Campbell had a great way with words and the translation was top notch. For those unaware, The Hero of a Thousand Faces proposes that there is a universal pattern in humanity’s mythologies that involves a person (usually a man) that went out into a journey far away from his home, faced many obstacles, both external and internal, and returned triumphant with a prize, the Grail or the Elixir of Life, back to his home. Campbell’s strength is that he managed to systematize so many different sources into a single cohesive narrative.

At the time I was impressed and decided to study more and write in an interdisciplinary research with economics – by writing an article on how the entrepreneur replaces the mythical hero in today’s capitalism. I had to stop the project in order to focus on more urgent matters (my thesis), but now that I finished I can finally return to this pet project of mine.

If you might have seen previous posts, I ended up having a dismal view of economics. It’s a morally and spiritually failed “science” (I have in my drafts a post on arts and I’m going to rant another day about it). Reading all these books on comparative mythology is so fun because it allows me for a moment to forget I have a degree in economics.

Until I started to realize there was something wrong.

My research had indicated that Campbell and others (such as Mircea Eliade and Carl Gust Jung, who had been on of Campbell’s main influences) weren’t very well respected in academia. At first I thought “fine”, because I’m used to interact with economists who can be considered “heterodox” and I have academic literature that I could use to make my point, besides the fact my colleagues were interested in what I was doing.

The problem is that this massive narrative of the Hero’s Journey/monomyth is an attempt to generalize pretty wide categories, like mythology, into one single model of explanation, it worked because it became a prescription, giving the writer a tool to create a story in a factory-like pace. It has checkboxes that can be filled, professional writers have made it widely available.

But I started to realize his entire understanding of mythology is problematic. First the basics: Campbell ignores when myths don’t fit his scheme. This is fruit of his Jungian influences, who claim that humanity has a collective unconsciousness, that manifest through masks and archetypes. This is the essence of the Persona games (and to a smaller extent of the Fate games) – “I am the Shadow the true self”. So any deviation from the monomyth can be justified by being a faulty translation of the collective unconsciousness.

This is the kind of thing that Karl Popper warned about, when he proposed the “falseability” hypothesis, to demarcate scientific knowledge. The collective unconsciousness isn’t a scientific proposition because it can be falsified. It cannot be observed and it cannot be refuted, because someone who subscribe to this doctrine will always have an explanation to explain why it wasn’t observed. In spite of falseability isn’t favored by philosophers of science anymore, it remains an important piece of the history of philosophy and he aimed his attack on psychoanalysis of Freud and Jung – and, while they helped psychology in the beginning, they’re like what Pythagoras is to math. They were both surpassed by modern science and they are studied more as pieces of history than serious theorists.

But this isn’t the worst. All the three main authors on myths were quite conservatives in the sense of almost being fascists – sometimes dropping the ‘almost’. Some members of the alt-right even look up to them as some sort of “academic’ justification. Not to mention anti-Semitic. Jung had disagreement with Freud and Freud noticed his anti-Semitism. Eliade was a proud supporter of the Iron Guard, a Romanian fascist organization that organized pogroms and wanted to topple the Romanian government. Later Eliade became an ambassador at Salazar’s Fascist Portugal, writing it was a government guided by the love of God. Campbell, with his hero worship, was dangerously close to the ur-fascism described by Umberto Eco (please read here, you won’t regret https://www.pegc.us/archive/Articles/eco_ur-fascism.pdf).

“If you browse in the shelves that, in American bookstores, are labeled as New Age, you can find there even Saint Augustine who, as far as I know, was not a fascist. But combining Saint Augustine and Stonehenge – that is a symptom of Ur-Fascism.”

Campbell did that a lot. He considered the Bible gospels and Gnostic gospels to be on the same level. Any serious student, that is not operating under New Age beliefs and other frivolous theories like the one that says Jesus went to India, will know there’s a difference between them (even Eliade was sure to stress the difference).