#how many more obscure parts of my bodily experience are going to turn out to just eds

Text

was anyone going to tell me your eyes aren’t supposed to burn when you cry and can be a sign of eds or was i supposed to see a tiktok of it myself

#are you kidding me??#first it was screaming hiccups now its eyes burning??#i asked my sister who we think has it and hers burn#then we asked mum who definitely doesnt have it and hers dont#like holy shit#thats always in book descriptions of characters trying not to cry#how they feel a burn behind their eyes#my eyes definitely burn#also youre not supposed to be puffy the day after but i dont cry often enough to know if i get puffy#i know i feel puffy#how many more obscure parts of my bodily experience are going to turn out to just eds#also mcas and im still not sure if i have that#coming out of my cage and ive been doing just fine.txt#spoonie#pots#eds#ehlers danlos syndrome#mcas#mast cell activation syndrome#mast cell activation disorder#dysautonomia#dysautomnia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Survey #306

i’m v talkative today so pardon my jabbering below.

What is the strangest type of candy you have eaten? I think I've had one of those lollipops with a bug in it before as a kid? I don't remember.

What would be your most ideal profession? A freelance photographer. But I'm honestly starting to lose hope.

Have you tried those coloring books for adults? Yeah; it's funny you mention 'em, 'cuz a family friend got me one for my birthday earlier this month.

What is a topic you definitely don't want to talk about with anyone? I don't like talking about my sexual history, doesn't matter who you are. It's just uncomfortable.

What was your first gaming console? An Atari.

Is there something you're eagerly waiting for? What is it? *SLAMS FISTS ON TABLE* MAY NEEDS TO FUCKIN' HURRY. My tattoo appointment is set then. :''')

Do you/have you ever belonged to an organization? If so, which one? I was a Girl Scout when I was young.

What is something you're very passionate about? Nature conservation, gay rights (equal rights in general, really), the pro-choice movement, and then there are less "important" things like certain hobbies interests and such. I'm sure there are more big ones that are just slipping my mind right now, considering I feel passionately for a shitload of stuff.

What are you studying or what was the last thing you studied? I majored in Art & Design with a focus on Photography in college. But guess who dropped out.

What was the last present you gave someone? I don't know... I mention enough that I don't have a source of income where I can really buy anything. I think the last thing I did was a Christmas gift for Mom a year or two back of a drawing I did of our late dog Cali, whom she absolutely adored.

Do you enjoy plays? If so, what was the latest one you saw? Not really, no.

What was the last thing you achieved? PHP has helped me focus on little victories, so prepare for an underwhelming answer haha, but it's something. I Facebook messaged an old friend I really wanted to catch up with, and everyone in group cheered for me. :') It was really heartwarming. What a shocker that this program is really helping me once again.

What is something you would like to achieve at some point in your life? I would love love love to take at least one "famous" or award-winning photograph. It'd be such amazing validation that I'm talented at something I love so much.

What is one philosophy you have regarding life/living/purpose? That's... difficult to answer seeing as I'm trying desperately to find my purpose. I do try to live by this old quote a therapist said once: "Deal with life, or life deals with you." I think it holds an incredible amount of depth and meaning in such a short phrase.

How would you design the inside of your own home? I don't know the details of it, really, besides that shit is gonna look like a Halloween house year-round. I can imagine wanting black furniture, too, and having loooots of decor expressive of what I love and find comfort in. Gotta make a house feel like a home just for me.

What is a band you remember liking from your childhood? Backstreet Boys, duh.

Do you ever get mad at people for not having the same opinion as you (i.e. abortion being wrong/right, meat-eating being wrong/right)? Two things: it depends on the topic, and "get mad" is the wrong term for what I feel. It's more disgust; ex., I'm repulsed by anti-gay rights people and want absolutely nothing to do with 'em, but I'm not like, mad at them.

Do you edit any of your pictures? In what ways? Oh yeah, and it definitely depends on the raw photograph. I edit depending on the mood it emanates; like if you've seen my roadkill photography versus nature shots, there is an extremely distinct difference in editing style and vibe. I'd say in general though, I tend to like to brighten my photographs and add more vibrance.

If you like to take pictures, what is your motivation? God, I could write an essay on this. I just love and am so thankful for the fact we can literally freeze time forever with the click of a button and look back on fantastic sights, beautiful moments, memories... It's just magical to me, and I adore contributing to that art.

Would you ever consider living anywhere cold? Well yeah, that's my preference, actually.

What is your absolute favorite food? The spicy shrimp fritas from Olive Garden, jfc.

Would you ever wear snake-skin pants, or other animal clothing? Fuck to the absolute hell no.

What foreign country would you like to go to for a shopping spree? Idk, considering I'm not well-versed in the artistic creations of other countries. Perhaps India? Japan? I dunno.

If you met your favorite musician, what would you ask him/her? I'm asking for his fucking autograph and a hug while I smile my face in two AND cry lmao.

What do you spend most of your day thinking about? I ain't gonna bullshit nobody, my PTSD. In some way or another, he's lurking in that head of mine through memories, flashbacks, wonders of what could have gone differently... but thank God it's no longer in the forefront of my mind after my first PHP. I've come very, very far, but especially when trying to blank out my mind to fall asleep, parts of PTSD strangle my brain until I'm just finally out. I really hope that changes someday.

Where is a busy place you would like to go to? Yikes, nowhere, really. I like to avoid busy locations.

Do you think video games cause people to become violent? Absolutely not. You are responsible for the decisions you make; music, games, movies, etc. have no deciding voice in stupid shit you do, and it's bullshit that people blame art and entertainment for such things.

Vocabulary: What was the last word you learned? I'm unsure.

Have you or could you build your own site? Absolutely not from scratch. The closest I've gotten to that is my photography website, but it was through the assistance of Wix.

What's the best thing you can cook yourself? Scrambled eggs, haha. I do make some bomb eggs at least.

Are there a lot of graffiti around your neighborhood? No.

Do you have a hobby that forces you out of the house? If so, what is it? Nature photography.

Would you stop eating meat, if you had to raise and slaughter it yourself? Absolutely. God, I want to go vegetarian again...

Besides English, what other languages can you speak? I can speak a very little bit of German. Took four semesters of it in high school and became very good at it, but lack of practice has pretty much ruined that.

Besides English, what other languages can you read? I can read German well; as in, I can pronounce most words I see, but that doesn't mean I understand what is written.

Do you think you could make it as a chef? Gordon Ramsey would deadass kick me off his show on day one, lmao.

What's your favorite kind of tea? It marvels me JUST how many tea and coffee questions are in surveys. Anyway, I don't like tea. I am an embarrassment to NC culture.

What thing/person/happening has made you the happiest you've been? lask;dfjal;wekrjwe

What's the most freeing thing you've ever done? Stealing my happiness back from someone who had no right to hold it all in its entirety. That shit's mine.

Do you think today's kids are really impatient? Most, probably, but in some ways I can understand it - at least, in the sense that with the assistance of modern technology and advancements in satiating our wants so quickly, kids just expect it. I definitely believe that patience is something to try to be deeply instilled in everyone, though. I don't have an ounce of it (in most situations) and wish I did.

Have you ever tasted birch sap? No.

How about the young buds/shoots of spruce trees? No.

Which edible flowers have you tasted? One of my favorite Southern experiences is finding a bunch of honeysuckles and tasting the honey (is it technically even honey??). Tastes amazing. My family's hairdresser lives down a beautiful path that sprouts a massive amount of them, and as kids, my sisters and her two boys would go tasting them while our parents talked for so long, or if we were waiting our turn. Good memories.

What has been your worst restaurant experience? I'm not sure, really.

What's the most immature, adolescent thing that still makes you laugh? "Inappropriate humor type jokes." <<<< They can get me sometimes, too.

Have you ever had a life-threatening condition? If so, what was it? No, thankfully.

Have you ever had a custom print done on a shirt? If so, what was it? I don't believe so, no. Besides making a tye-dye one in HS with our school colors. Wasn't my idea and never wore it, haha.

Do you ever read other people's survey answers? It depends on the person. If it's a friend, absolutely, because I love learning usually obscure things about them I wouldn't have known otherwise. If it's a user I don't know from wherever I got the survey, sometimes, depending on how short the answer is and my eyes kinda just scroll over it.

Do you like daytime or night time better? Why? Daytime, especially mornings. I'm generally happier when there's light around.

What's your highest level of education so far? Some college.

Describe your ordinary day: My average day is embarrassingly uneventful. It's sitting on the laptop doing shit on various sites, none of which are actually important, and playing WoW, which is also without true substance, save for social interactions with my friends on there. I spray Venus' terrarium everyday multiple times as well to keep the humidity up, and obviously eat and handle that kinda bodily needs stuff.

Would you ever have a UV tattoo? Ugh, that'd be so dope. I've seen some awesome ones, but idk if I'd get one, considering when am I actually going to be under UV light?? Like I wanna be able to see my tat.

What is the brand and color name of your favorite lipstick? I have one black lipstick, but it comes right off so I don't even like it. I only ever put it on to take pictures.

What do you like on your tortilla? Just ham and cheese.

How about inside your pita bread? I've never had pita bread, actually.

What do you like in your burger? It depends on where I'm getting the burger. My basic is cheese, ketchup, mustard, a bit of mayo, pickles, and a light sprinkle of diced onion, but sometimes I add bacon and take away the onions.

How about on your pizza? I have three I tend to pick from: pepperoni, jalapeno, or meat lovers.

Do you work better alone or in a group? Alone, definitely.

Which body part would you not mind losing? I'ma be extremely honest, with just how horribly weak my legs are, I could live without them, I guess. Not saying I want to by any means, it's just exhausting using them. Ideally, I'd take away something minor, like a finger or something.

What common saying people use is absolute BS to you? “'Everything happens for a reason.'” <<<< Fuckin' colossal "same." I won't rag on people who believe it, especially if it gives you courage to keep moving forward, but I don't believe it in the slightest. If it were so, I'd like to talk to whoever is in control of those "reasons," please.

What is the most interesting thing you’ve read or seen this week? I had no idea elephants were pregnant for two years, like holy shit, can you imagine. It was in an article I saw on Facebook about a mother and daughter elephant who are both expecting and doing well. Wonderful to hear.

What’s the most useless talent you have? Ha, I'm a master in the arts of catastrophizing and jumping to conclusions involving people hating me in one way or another.

What’s something everyone looks stupid doing? I'm one of those people who hate dabbing done by anybody, like you look like you're just smelling your armpit.

Which kids’ movie scarred you for life? I wouldn't say "scarred me for life" by any means, but when I was little, I was terrified of the Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz and even had nightmares about her. It sucked because my little sister was obsessed with that movie, haha.

In one sentence, how would you sum up the Internet? A source of incredible knowledge but also hate and misinformation.

What would be the most ridiculous thing for the government to make illegal? I literally dread the idea of Roe vs. Wade being reversed. Banning abortion would kill so many people with operational uteruses and cause absolute pandemonium.

How many friends do you have on social media and how many of them do you know for real? On Facebook, I have 124 friends, and I'd say I know most of them "in real life." However, having been on the Internet since I was so young and befriending loads of incredible people, a good chunk are "online friends." Hell, I'm more interested in their lives than most "real" ones. Long-distance friendships are so valid.

What fact amazes you every time you think of it? Lots of things, generally regarding the stupidity of humanity.

What’s the most spontaneous thing you’ve ever done? Probably going to the beach w/ my old friend Colleen. We had zero plans of doing it, but she just called me one morning and asked if I wanted to go, and off we went. It was a fun day.

What has taken up too much of your life? I'ma be real, WoW. I don't think I'm addicted to it like I once was seeing as I go through spans where I barely want to play it at all and don't, so I truly am capable of not playing it, but rather it's just the most entertaining way to kill time in my life. I just don't like how much time I've invested into a game over six or seven years regardless.

Where do you not mind waiting? Uh, nowhere lmao.

Is there an app you hate to use, but still use every day? No; why would I use it if that was the case?

Who is the funniest person you know? My friend Girt is fucking hysterical.

What three words describe you best? Complex, passionate, and creative.

What makes you think you’re smart? Lol who says I think I'm smart?

Who inspires you? Korean Jesus. Okay on a serious note, not just him, of course, but he's #1 in an entire universe of ways.

Do you aspire to be like somebody else? If so, who? No; I want to be my own authentic self.

How did you meet your best friend? YouTube, back when it had more social aspects.

Which one of your accomplishments are you the most proud of? I want to say my recovery, but like... I wonder a lot if it's "enough" to be proud of with how scarred I still am? I still struggle with a lot and feel like I could be so much better by now if I tried harder. If I'm completely honest with myself, I think it's finishing high school in the top percentile of my graduating class. There was a ceremony for the handful of us and all, and I cherish my plaque probably too much. Reminds me of a time when I knew what the fuck I was doing.

What's the strangest thing you ever did as a child? Thinking I had "animal powers" where I could invoke the traits of certain animals at will, like what the actual fuck, Brittany.

What did your mother teach you? Christ, a lot. Dad didn't do a lot of the raising, honestly, so much of my core values and whatnot were instilled by my mother. She taught me to care for and be nice to others, respect myself, try my best in everything, and most importantly that she is always there for me and my sisters no matter what and can tell her absolutely anything. She was very serious about us going to college and saving sex for marriage when we were younger, but she diverged from those ideas as absolutely necessary with experience. I'm extremely lucky with who I call my mom, overall.

What did your father teach you? Eek... Read above. Not a lot as a kid (save for riding a bike and playing softball); most he's taught me has come following reuniting with him after my parents' divorce. I remember we went to lunch once and talked about my breakup, and he talked to me about sometimes, you just have to let people go in order to be happy, like with him and Mom. He's very serious now about ensuring us girls know that he is always there for us and will help us in any way he's capable.

What makes you feel powerful? "Powerful" isn't something I really feel, if I'm being real.

What are you ready to let go? It would be inexplicably fantastic if I could let every speck of Jason go in both my head and heart.

What is your most bizarre deal-breaker? I don't really find any of my expectations and limits as "bizarre?" They're all valid to me. Well wait, idk if you'd find it strange that I absofuckinglutely would not date someone who hunts, but it's not to me. That's a difference in a very serious value to me.

Would you rather be hated or forgotten? Hated. God, I don't want to leave this earth having given just nothing. I can live with some people hating me for whatever reason.

What’s the biggest personal change you’ve made? Accepting my bisexuality, probably. That's something that I consider pretty big for two reasons: 1.) I could end up with a woman forever, and especially 2.) I was originally homophobic. I still have difficulty in fathoming how I ever was.

What are some of your short-term goals? PHP is finally starting to make me build these again. I want to get better at selfcare, draw, write, and read more, I want to drink a lot more water, exercise way more... Lots of things, really.

What is the weirdest thing about you? Uh. I dunno. Probably that I RP meerkats, which is a very obscure RP niche for sure.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Art Of Trying To ‘Pass’ As Female (My MtF~HRT Research)

Just as Krista described her need to change her face in order ‘just to leave the house,’ most of the 28 patients with whom I conducted interviews and observations, and the many others with whom I shared casual conversations, explained their desire for facial transformation in order to carry out everyday activities. As much as patients might want to be beautiful women after surgery, their primary desire was to walk through the world being recognized as women—which, in a sense, meant not being recognized at all. But just as physician discourse often conflated or collapsed the biological category of the female with the aesthetic category of the beautiful when describing the aims of feminization, so too did patients draw on both of these notions when communicating what their goal of being a woman actually means.

Woman is difficult to define as a surgical category precisely because it is difficult to define as a social one. Not surprisingly, patients had different ideas (and ideals) in mind when they imagined the kinds of transformations that would allow them to be the kind of women they wanted to be. When I asked Rosa if she had a particular idea of what she hoped to look like after surgery, she immediately said, “Yes,” and reached into her bag. She pulled out a stack of papers wrapped in plastic sleeves and held together by a binder ring. She shuffled through the stack, unfastened the ring, and put a page on the desk in front of me. There were three photographs that had been clipped from magazines and pasted to a sheet of white paper. As she began to talk I was not sure which one I was supposed to be looking at. “I want to look like a woman,” she began. “I want a face that a man falls in love with. Like an angel. Innocent. You are a man. You understand. Look at her [pointing to an image on the page.] What do you feel? Body is nice, but look at her face. In that picture you can’t see her breasts, but you can see her face. She’s beautiful. You feel inside something like love. I want a face that a man sees and it makes him turn red.” Rosa was not sure what her particular features would be when all was said and done. She did not expect Howard to replicate the model’s face onto hers. She did, however, expect that her face would be one that would do something for others and, in turn, do something for her. Rosa described the changes she was after in terms of how particular aspects of her face evoked gendered attributes.

When our conversation turned from the effect she desired to the precise means of achieving that effect, she gave an inventory of her face and the multiple ways that it works against her. The bone above my eyes gives me an aggressive look. I have dark, shadowed eyes. If you see that actress Hillary Swank, she has this. Something doesn’t match on her face. Nose, obviously. My nose is male. Upper lip. I can’t wear red lipstick. If I wear read lipstick it makes me look like a man in a dress. When I watch videos of myself, my expressions never look happy. I look angry.

Rosa was confident that following surgery she would ‘feel more sure of [her]self.’ It was this confidence that made women beautiful. Just something about them that had such power and sex appeal. Women, in her telling, were not aggressive or angry; their faces are built to be adorned. Though she knew that Howard could not necessarily make her beautiful, she was confident that he could make her a woman. For her, that was enough.

Gretchen had much more modest desires. Her hopes for surgery were less about eliciting a particular response, than avoiding a reaction altogether. Just…I hope that I won’t have this kind of jerk that was sitting just to my left on the plane this morning who was seemingly horrified by seeing this (gestures to her face and body). He was probably having the idea that I was fantasizing about him or something. I just hope that next time, he won’t think about it twice. ‘Yes, I’m sitting beside a girl. So what and that’s all.’ End of story.

Pamela expressed her desires this way: I'm doing it (having FFS) so I will feel that I "pass" (making air quotes). Whatever that is. And of course the operative word there is ‘feel.’ I'm tired of thinking, is that person reading me? No? Well how 'bout that person? I want to think about something else as I walk down the sidewalk.... Like, say, what a nice dress in the window. Maybe that's it. Going unnoticed is a thing that most people take for granted.

Erving Goffman (1963) called those who do not draw unwelcome attention from their bodily appearance ‘normal’s.’ Normal’s, Goffman argues, simply cannot understand how it feels to be the object of derisive looks and hostile attention from complete strangers. To be a member of a stigmatized group is to be the object of distain. When some aspect of your physical body is the source of that stigma, there are, according to Goffman, two possible responses. You can come to terms with the fact of your stigma and attempt to ‘normificate’ it by acting normal, as though the stigma did not exist. Or, you can normalize it by making a conscious effort to correct it. Though ‘norming’ surgeries are sometimes the objects of ethical debate, the validity of the desired outcome is hard to dispute.

In an article entitled, ‘Self-Help for the Facially Disfigured,’ Elisabeth Bednar put the matter simply. Whether we are shopping, riding the subway, or eating in a restaurant, all of which are casual day-to-day social encounters, there is the initial stare, then the look away, before a second, furtive glance inevitably puts the beheld immediately in a separate class. For those who experience this discrimination, the question of the moral justification of surgery to increase societal acceptance...

She pointed out photographs in Howard’s book in which surgery did not necessarily improve a patient’s attractiveness, but it did change her sex. When referring to before and after photographs she said, “See this is an ugly boy and this is an ugly girl, but it is a girl. Other doctors can’t do this.”

There can be no greater wish than to melt into the crowd or to walk into a room unnoticed (Bednar 1996:53). The patients and surgeons with whom I worked, referred to the fact (or fantasy) of going unnoticed as ‘passing.’ The language of passing is contentious for some transpeople because it can be read as implying a sort of deception; being taken as a member of a group to which one does not really (where really refers both to an ontological truth and to the rightful membership based on it) belong. This deception is also often marked by a supposed opportunism; passing is really only considered as such when a person passes from an undesirable group and into a desired one (Gilman 1999). It therefore frequently carries a connotation of a strategy to access particular forms of privilege. Many transpeople object to the language of ‘passing’ because, they argue, to say that one passes as a woman is to acknowledge that woman is not a category to which she rightfully belongs.

As Julia Serano insists, “I don’t pass as a woman. I am a woman. I pass as a cis-gendered woman” (by which she means a woman who has never changed her gender). These sorts of concerns about what it means both politically and ontologically to pass, were only voiced by two of the patients with whom I spoke. Despite their reservations, they, like all other patients I met, held the desire to pass as an incredibly important and explicitly stated aim. As historian of medicine Sander Gilman explains, ‘The happiness of the patient is the fantasy of a world and a life in the patient’s control rather than in the control of the observer on the street. And that is not wrong. This promise of autonomy, of being able to make choices and act upon them, does provide the ability to control the world. It can (and does) make people happy’ (1999:331-2).

Like language, social roles do not exist in isolation (Wittgenstein 1953:§243); they are by definition shared properties conveyed between people in given social group. A person’s individual conviction that she is a woman is not enough to maker her a woman in any social sense. To be a woman requires not simply the conviction that one is a woman, but the recognition of that status by others.

FFS is a surgical recognition that how one feels about and lives their sexed and gendered embodiment is not a private, psychic reality, but is the product of social life, of living with others. Passing is not a subjective act; it is a social one. Nearly all clinical literature as well as most popular literature on transsexualism suggests that transsexualism is a property (and problem) of an atomized and bounded individual. This focus on the individual and psychic nature of the bodily dissatisfaction that characterizes transsexualism is named explicitly as well as through the invocation of metaphors of isolation, internality and invisibility. While an individual body may be the site of the material intervention, the change enacted in FFS takes place irreducibly between persons. The efficacy of FFS is located not in the material result of surgery itself, but in the effect that the surgical result will produce in the perceptions of imagined.

Other writers argue that the goal of ‘passing’ not only obscures but effectively forecloses any possibility of a trans- specific radical political subjectivity (Bornstein 1994, Green 1999, Stone 1991). These writers insist that living as out trans-people is the only way to call attention to the oppressive gender system that devalues and delegitimizes trans-lives and bodies, among others. This kind of visibility can come at the great cost of personal and emotional safety, leading to a conflicting desire to be a part of the solution while maintaining ones safety and sanity (Green 1999). Perhaps nowhere is this made clearer than in the imaginary scene through which Howard explains the goal of his surgical work:

If, on a Saturday morning, someone knocks at the door and you wake up and get out of bed with messy hair, no makeup, no jewelry, and answer the door, the first words you’ll hear from the person standing there are, “Excuse me, ma’am….”

This incredibly powerful scene was a staple of Howard’s conference presentations, and was repeated in slightly altered and personalized forms by many of the patients who had selected Howard as their surgeon. Through this turning outward—and the making of femaleness at the site of the exchange with a stranger—FFS reconfigures the project of surgical sex reassignment from one rooted in the private subjectivity of the genitals, to one located in the public sociality of the face. Time after time, patients told me that their primary desire was to go through their daily lives and be left alone, without thinking about what others may see when they look at them.

Krista rode the city bus on the day before our interview. On that day, for the first time in recent memory, she did not prepare extensively before leaving the house. “I didn’t have to worry about having my bangs just right, or having just the right pair of glasses on. I just got on the bus and thought, ‘Wow, this is cool.’” Although her face was covered in bandages, sutures, and bruises, and people on that bus were undoubtedly looking at her, Krista found joy in the certainty that whatever they might have seen when they looked at her, the did not see a transwoman. The stuff of her maleness was gone. It was a novel—but so, so welcome—experience. It is important to remember that the stakes for passing are often quite high, often quite serious. The desire to pass does not only exist for the gratification of personal goals, but also achieves a mode of physical and emotional safety. It is crucial to remember that trans-people are disproportionately incarcerated, unemployed, and lost to suicide and other violence. I make this point not to hold counter discourses hostage to its message— as in an accusatory stance from which any divergence is a de facto support of transphobia or worse—but to tell the complete story of the context in which these procedures become objects of desire, and accomplish practical goals sometimes on the measure of life and death.

THE FULL FACE

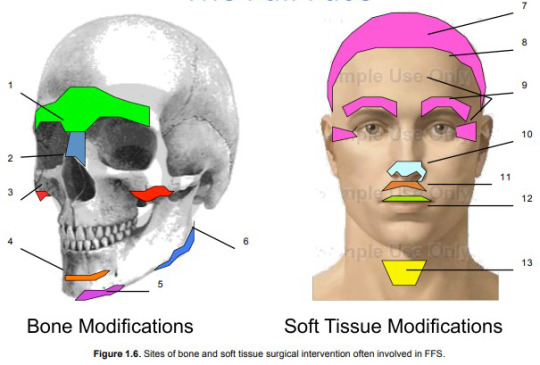

Facial Feminization Surgery includes interventions in both the bone and soft tissues of the face. In general, the procedures involved in FFS are aimed at taking away or reducing particular features of the bones and soft tissue of the face. This focus on reduction and removal is based on a fundamental assertion that males are, on the whole, larger and more robust than females.

This assertion applies both to the bony skeleton and to soft tissues such as skin and cartilage. Whereas the modification of the facial bones are guided, at least in Howard’s case, by numerical norms, most soft tissue procedures are not. (The exceptions are the height of the upper lip and of the forehead; these assessments are guided by numbers and measurement). Instead, soft tissue procedures are often oriented toward and aesthetic ideal of feminine attractiveness.

Below are brief descriptions of the surgical procedures organized under the sign of Facial Feminization. Not every patient undergoes all of the procedures described here, though some certainly do. In Dr. Howard’s parlance, a patient whose surgery includes all of these procedures gets, ‘The Full Face.’

While one of the fundamental goals of this dissertation is to trouble the claims to absolute difference that often animate FFS, in the following descriptions I make use of the dichotomous distinctions that doctors use when characterizing the masculine features of patients’ skulls.

Bone Procedures

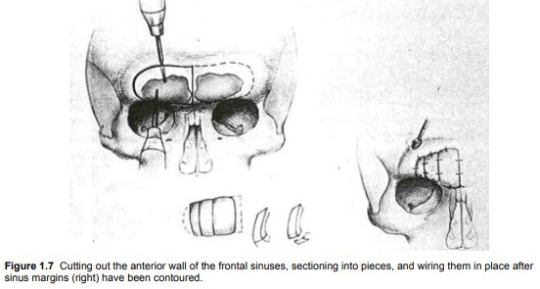

Brow Bossing and Frontal Sinus:

The prominence of the brow is one of the most distinctive and recognizable aspects of a masculine face. Some reduction of the brow can be accomplished through burring down the bossing (the thickness of the bones) just above the eyes. In other cases the anterior wall of the frontal sinus (the empty space just above and between the eyes) is removed (“unroofed”) and set back. The reduction of the frontal sinus is considered the most aggressive of all procedures involved in Facial Feminization Surgery (see Figure 1.7).

Rhinoplasty (internal reshaping of the nasal bones):

Rhinoplasty involves the fracturing of the nasal bones as well as the removal of cartilage. More radical bone fracturing and removal is required when frontal sinus reconstruction is performed. When the forehead is ‘set back’ through this procedure, the bones at the nasion (the depressed area between the eyes just superior to the bridge of the nose) must be reduced in order to create the desired relationship between forehead and nose.

Malar (cheek) Implants:

In order to produce the desirable oval shape of the female face, implants may be placed over the malar bones to enhance the fullness of the cheeks.

Genioplasty (chin shortening):

Based on the claim that female chins are shorter than male chins (as measured from the top of the bottom teeth to the most inferior point of the chin), a wedge of bone can be removed from the chin, and slid forward. Moving the bottom section forward also results in creating a more pointed chin.

Reshaping mental protuberance (chin):

A pointed chin is recognized as feminine, whereas a square chin is masculine. In combination with the advancement of the inferior portion of the chin, contouring is also done to enhance this characteristic.

Reduction Mandibuloplasty (jaw bone):

Alterations of the mandible focus on the undesirable squareness of the masculine jaw. This squareness is attributed to two aspects of the mandible: mandibular angle and mandibular flare. The mandibular angle describes the angular value of the posterior and inferior portion of the jaw. The more acute the angle, the more masculine the jaw. This is best seen from profile. Mandibular flare describes the extent to which the squareness of the jaw extends toward the lateral sides of the face. This squareness is best seen when looking at a person from the front. In both cases, bone can be removed in order to reduce the appearance of masculine squareness.

Soft Tissue Procedures

Scalp advancement:

By severing the tissue that connects the scalp to the scull, the scalp may be brought forward toward the face to help a patient compensate for a receding hairline. Excess tissue at the top of the forehead is excised. Scalp advancement as well as hairline reshaping and eyebrow raising all occur through the coronal incision (from ear to ear just behind the hairline) required to alter the bony contours of the forehead.

Hairline Reshaping:

In addition to bringing the hair-bearing scalp forward, the hairline itself can be reshaped. In this procedure, the M shaped male hairline is rounded out to reduce (if not eliminate) temporal baldness caused by a byproduct of testosterone.

Eyebrow Raising/Crow’s Feet Reduction/Forehead lift:

As noted above these procedures are performed at the site of the coronal incision after the bone work on the forehead has been completed. When tissue is excised during scalp advancement, the position of eyebrows is raised up higher on the forehead. This is described as a feminine characteristic. The appearance of the eyebrows is also changed as a result of the changes to the bones of the brow and forehead beneath them. The pulling of the skin of the forehead generally produces the addition (and typically considered beneficial) result of eliminating the wrinkles around the eyes often called crow’s feet. During this procedure, surgeons have access to the internal muscles of the forehead and may choose to perform a perforation of those muscles; this procedure is typically referred to as a forehead lift.

Rhinoplasty (reshaping of the cartilage and tip of the nose):

The tip of the nose is given its shape by internal cartilage. After the bone modifications have been made, the cartilage can be reshaped in order to achieve a ‘more feminine’ nose.

Upper lip shortening:

According to the surgeons with whom I worked, males have a longer upper lip (distance between the bottom of the nose and the vermillion part of the upper lip) than do females. This distinction can most easily be seen by observing how much of the upper teeth are visible when a person’s mouth is slightly open. This measurement is referred to as ‘tooth show.’ The length of the upper lip can be reduced by excising the desired amount of tissue just beneath the nose, raising the upper lip toward the nose, and applying sutures in the crease just at the base of the nose. This also results in increasing the amount of vermillion visible in the upper lip.

Lip Augmentation:

Lips can be augmented through a variety of procedures including the injection of pharmaceutical products (such as Botox and Restylane) or fat taken from other sites in the patient’s body. More permanent augmentation can be achieved by placing some of the tissue excised during the scalp advancement into the tissue on the underside of the upper lip.

Reduction of the thyroid cartilage (“Adam’s Apple”):

The Adam’s Apple—or more properly, the thyroid cartilage—is considered to be one of the clearest indicators of maleness. Thyroid cartilage removal is often referred to as a Tracheal Shave (or just trach shave) despite the fact that it is neither the trachea being altered, nor a shaving motion used to reduce it. While a relatively simple procedure, the thyroid cartilage reduction carries significant risks. An inexperienced surgeon may remove more tissue than necessary, and inadvertently alter the site where the vocal chords insert. This can result in a radical modification of vocal pitch.

CLINICAL EVAL

Clinic One -- Dr. Howard

Upon entering his office from the hospital corridor, one enters a warm but unremarkable waiting room: carpet and walls in shades of neutral brown, upholstered armchairs separated by low coffee tables offering a selection of news and fashion magazines.

In addition to personal and administrative offices, the practice has three small examination rooms, each equipped with a large examination chair (somewhat like a dentist’s chair, it defaults to an upright but gently reclining position), a rolling stool (on which Howard sits during most of the exam), a small side chair (where I sat while observing exams), and a counter at the back of the room that contains a hand-washing sink and a light box for illuminating x-rays.

There are few decorations in the exam room dedicated to initial consultations and pre-operative appointments. To the right of the patient seated in the exam chair, a silver and bronze toned image of a naked and reclining woman hangs on the wall. Her long hair flows down her back and shoulders but leaves the side of her breast exposed. On the wall facing the patient—and so behind Howard as he conducts the exam—is a magazine rack that holds several fashion magazines.

When I entered the room, Tracy was seated in the reclining exam chair, hands folded in her lap and looking nervous. Howard urged her to keep her seat as I introduced myself and shook her hand. With Tracy, as with all other patients whose consultations I observed, Howard began the appointment with a few minutes of friendly conversation. He inquired about the Canadian city in which she lives. As a person who has done a considerable amount of traveling throughout the world, Howard often has a personal story to tell about the patient’s hometown.

Though he tends to speak rapidly as a norm, these exchanges do not seem to me to be perfunctory or rushed; people’s stories sincerely fascinate him. After having seen this routine enacted a number of times, it is clear that Howard uses these first moments to establish a friendly rapport with new patients who are frequently very nervous—and in some cases could be best described as star struck. While this moment may be the culmination of many months or years of a patient’s personal and financial work, for Howard, this is another day in the office.

After the brief exchange of pleasantries, Howard moved into questions about Tracy’s medical history: height, weight, medications, prior surgeries, and so on.

When Tracy stated that she was actively losing weight and would like to get down to 180 pounds, Howard made his first recommendation of the appointment. “I’d like to see you down to 160,” he said. “The best results I see—not surgically but in terms of overall femininity—are in patients who get down to a female weight for their height. When you get down to 180, just keep on going.” While completely unrelated to the craniofacial surgical consultation underway, Howard’s recommendation on “overall femininity” signaled his understanding of FFS as both part of a larger goal of corporal feminization, but also as just one part of achieving that goal. In addition to signaling a holistic understanding of the project that brought Tracy to his office, this shift from conversation to recommendation marked the beginning of the exam; he is the expert with information to give.

Howard did not ask why Tracy was in the office to see him. He did not ask what her goal was for surgery. He assumed in Tracy’s case and in all other consultations I observed, that a person whose paperwork indicates that she has come to the office for an FFS consultation is doing so because she wants to have her face reconstructed to take on female proportions. I have not heard this assumption corrected. It is with this assumption that directly following the medical history, he began making measurements on Tracy’s face.

Clinic Two -- Dr. Page

Page’s office, located in an office park in an affluent suburb of a major West Coast city, shares a building with accountants, attorneys, and dental offices. The Ambulatory Surgical Clinic where he performs most of his operations is attached to his office, though it has a separate entrance at the back of the building. In the waiting room, leather armchairs and a long couch are arranged around a low coffee table covered in fashion magazines. The walls are covered in an ivory-toned wallpaper that in combination with the light coming in through a large window makes the space bright, though somewhat impersonal.

The dominant feature of Page’s waiting room is a mirrorbacked, top-lit curio cabinet featuring branded cosmetic products such as Juviderm and Botox, the presence of which makes it impossible to forget that this is not a neutral space; there is something for sale here. The reception desk is located in the front waiting room and is staffed by a few different young women.

On two occasions the stillness of their faces and the shape of their lips have made me quite aware that they have ‘had some work done.’

The two exam rooms in Page’s office are considerably larger and more brightly lit than those in Howard’s office. Here too, the reclining exam chair is the largest and most central object in the room. A small chair (where I sat during observations) is positioned just to the right of the exam chair, and a full-length mirror hangs on the wall next to it. A counter with a small sink occupied the left wall of the room. A model of a human skull sat on the counter, looking directly at the exam chair. When Page invited me in to observe the consultation, Leanne was seated in that chair.

Leanne was one of the few patients I encountered during my fieldwork who arrived for an FFS consult in what was referred to in both offices as ‘man mode’ or ‘male mode.’ She had taken the opportunity to visit Page’s office while traveling through town on business and looked every bit the businessman: short-cropped sandy blond hair graying at the temples, a crisply pressed pale blue shirt, navy blue necktie, grey trousers and black oxford shoes.

Page habitually opens the conversation by asking patients how they heard about him and his practice. This sets the tone that the patient is a consumer who has shopped around, and it helps to identify him as a businessman who is eager to grow his practice. After a bit of small talk about Leanne’s hometown and learning that this was her first visit to the region, Page began the exam not by taking a medical history, but by prompting a personal conversation.

“Tell me about yourself, about your transition.” An examination is frequently understood to consist of two parts: the history taking and the physical examination (Young 1997:23). It is immediately clear that though Howard and Page each ‘take a history’ from their patients before beginning the physical exam, what constitutes relevant history is different for each of them. Howard asks his patients about what are traditionally understood to be medical issues: their height, weight, current medications, previous surgeries, and overall physical health. This information helps him to assess whether the patient is physically well enough to be a candidate for surgery. It also signals that his primary interest is in the physical properties of the patient’s body, an interest that is born out in no uncertain terms in the examination that follows.

Page, on the other hand, does not ask such questions of his patients during their initial appointments. Instead, he elicits a ‘history’ of the patient’s feelings about herself and her transition, more generally. Because the appointment begins with the disclosure of personal—and often quite emotional—information, the examination that follows is framed as one directed toward the realization of personal and emotional goals more than physical ones. As the consultations progress, the distinctions between Howard and Page’s approaches become clear. Howard’s meeting with Tracy appears in the left-hand column below. Page’s meeting with Leanne appears on the right.

Clinic One -- Dr. Howard

Howard: “Now I’m going to take some measurements and we’ll look at your x-rays.” Howard washed his hands and came back to sit down in front of Tracy. She was sitting in the exam chair and he rolled up to her on a small, wheeled stool. He took a small white flexible plastic ruler from his coat pocket and measured the distance from the cornea of her eye to the most forward prominence of her forehead. “Your brows are down a little bit.” He felt the brows and temples on both sides of her face using both hands. He pressed the sides of his thumbs up under the bones at the top of her eye sockets in order to get a sense of the shape of the bone. “Look at the top of that light switch.” Howard directed Tracy’s attention to the switch on the wall directly in front of her. Looking at this object helped to make her head level. “Open your mouth just slightly.” Howard measured the distance from the bottom of Tracy’s nose to the inferior ends of her front teeth. “Bite down on your back teeth.” Howard bit exaggeratedly on his back teeth to show her what he meant. Looking away, he felt the muscles on either side of her jaw with his hands. He turned to me and explained to the patient that we had been talking earlier about how he decides whether or not to remove some masseter muscle when he does jaw tapering.

Talking to me: “She has a fairly prominent jaw, but the muscle is not that large. I won’t even consider removing any muscle on her.” Howard runs the pad of his thumb up and down the center of Tracy’s throat. “Have you got one of these things?” Settles on the patient’s Adam’s Apple.

Howard: “If you have this done by someone else don’t let them put a scar at the middle of your throat.” Tracy lives in a country that has a national health service and Howard makes explicit reference to this since he knows that by using that service Tracy could save a considerable amount of money on this procedure.

Howard: As he describes the potentially problematic placement of some other surgeon’s scar, he draws a line across her thyroid cartilage with his index finger to mark the cut. “If I do it I’ll put the scar up here…” He draws his index finger just under the point of her chin to indicate where he would place the scar. …so no one can see it. “Plus if you put the scar here [in the middle of the throat] it can stick to the cartilage and then it moves every time you swallow. It looks like the dickens. Let’s look at your x-rays.” Howard walks to the light box behind the exam chair and invites Tracy to join him. They stand shoulder to shoulder in front of the light box looking at the cephalograms that Tracy brought with her to the exam. “First I look to see that you’re brushing your teeth, and it looks like you are (laughs). When I was measuring here before…” Uses his finger to show the measurement he took from the forehead to the cornea. “…I was looking at the maximum prominence of your forehead to the cornea of your eye. In you it was 15mm, which is average for a male of your height. As far as I know, this measurement is not taken anywhere else in the world. It is not a standard measurement. Once I am in there and I begin to contour the forehead, I can’t tell where I am. This measurement helps me locate myself in space.” By this he means that because the cornea does not move as a result of any bone reconstruction in FFS, he can use it as a constant reference. He took a handheld mirror from a small drawer and handed it to her. She sat, holding the mirror, looking at her face as he spoke.

Tracy is being educated about what Howard will do and why it is the best approach.

Tracy: “How far can you go back?”

Howard: “The most I’ve gone back is 9mm.”

Tracy: “Let me rephrase. How far can you go back safely?”

Howard: “I could go all the way back here.” Pointing to the posterior wall of the frontal sinus on the cephalogram.

Tracy: “What happens to the sinuses?”

Howard: “They go away. As far as we know.” He indicates with his fingers where the sinuses are located on the cephalogram. “…is to reduce the weight of the skull. Now, the jaw.” Howard looks at Tracy’s jaw, and then down to the x-ray. “Do you grind your teeth?”

Tracy: “I know I used to.”

Howard: “You’ve got some wide angles here. Feel your jaw.” He places Tracy’s hand on her jaw. “Feel how it flares out? We can get rid of the bowing that males have in the mandible that females don’t have.”

Tracy: “How do you do that?”

Howard: “We use a bur instrument on the sides here…” Indicating anterior portion of the lateral mandible on his own face. “…and then we have an oscillating saw that we use to take out the larger parts of the bone here...” Indicating posterior section on his own face.

Tracy: “You actually take out parts of the bone?”

Howard: “Yeah.”

Tracy: “Okay.”

Howard: “Can I borrow a finger?” Howard reaches down and grabs the index finger of Tracy’s left hand. He places it on the side of his face in the medial section of his mandible. “Feel my teeth?” He presses her finger into his cheek and moves it back and forth so she can feel the texture of the bone below his bottom teeth. “Feel that ridge? That is what we take away. For some people, a thin layer of blood that forms on the bone becomes bone. I am one of those people. I was hit in the head with a golf ball when I was 13 and I got this big bump.” He feels the bump on the top of his head. “I’ve still got the bump because the blood that formed there turned into bone. If you look at an x-ray you can see it plain as day. If you are a person like that—and I don’t know how to know that in advance—it is possible that some of that ridge may come back. But it won’t all come back. The chin. I measured from the top of your bottom tooth to the end of the bone and that is 50mm. That is average for a male of your height. I want to take out 8 mm of chin height. I can’t do that by shaving it off the bottom, because then the muscles and tissues that attach to the bottom of your chin have nothing to attach to and they just sag down. Instead, I take out a wedge of bone that is 8mm thick, and stabilize the bone with titanium plates and screws.” Howard explains that medical grade titanium comes from recycled Russian atomic submarines. He makes a joke that the addition of this Russian material may make Tracy fond of vodka after surgery.

Tracy: “You cut a wedge out of the bone and then rotate it up?”

Howard: “Yeah. Have you seen my book? Maybe you want to buy one. There is a lot of information in there about all of this stuff. And some stuff that you don’t need. It can answer a lot of questions. We want to get ride of the sublabial sulcus at the base of your chin. I think of this as a very male feature. Now, what to do. The brow. Right now the distance from your brow to your hairline is 7cm. I want 5.5cm. The average male has a distance there of 5/8 of an inch longer than the average female. This is the case in 16-year-old males, even before they’ve experienced hair loss. You have a type III forehead. We talked about that. We’ll do your nose—if we do the forehead we have to do the nose. Do you remember Dick Tracy? His nose went straight out like a shelf? You probably won’t like that. Upper lip. Now your upper lip has a vertical height of 2.5mm and drops 2-3mm below your upper teeth. If you look at me when I talk, you don’t see my upper teeth unless I smile. He smiled to demonstrate. Women show their upper teeth when they talk. We’ll want to move you up to get some good tooth show. So. We’ll do your chin, your lower jaw, the thyroid cartilage. If I do all this at one time—and most patients choose to do that because it saves them a lot of time—I know this will take almost exactly 10 ½ hours.

Tracy: “Everything?”

Howard: “Yes”. Howard went on to describe the risks associated with these surgeries, the recovery process, and necessary preoperative preparation. When he’d answered Tracy’s questions, he led her down the hall to talk money with Sydney.

Clinic Two -- Dr. Page

Leanne: “I began dealing with my gender issues at 50, when my wife and I became empty nesters. I have already been cleared for hormones but I am waiting to take them until after my daughter’s wedding in a few months. I am a manager—I mean, that is what I do for a living but that is also who I am. I like to have everything figured out before I start. That is why I am here. I don’t really know how hormones will affect me and what changes they might make to my face, but I do know that the face is the most important thing to me. I can do things with clothes, but I can’t hide my face.”

Page: “Making changes to your face can make you more feminine appearing.” As she spoke, he sat quietly, almost motionless. Like a practiced interviewer, he allowed her short silences to linger unfilled, and it turned out that she had a good deal to say.

Leanne: “I know that if I proceed with this my marriage will be over, and I understand that. My wife didn’t really sign up for all of this and I can’t force her to feel better about it. I am here because I want to manage my expectations; I need to know realistically where I might end up, instead of going forward with all of this and then finding out that you can’t do what I think you can do. I don’t want someone to give me all of the classic female things. This is a clear reference to Howard’s approach. I was interested in talking to you because you said that you work with features not totally remake them. It is not a clean slate. Given the face that I have, I want to know what to expect. Right now, I don’t look like a woman; I look like a man in a wig. I haven’t gone out much; I only wear women’s clothes when I go to counseling. But when I go out I worry about my face. I just don’t want to attract attention. I want to fit in.” Page did not verbally respond to any of Leanne’s personal and emotional disclosures; he simply began the physical assessment of her face.

Page: “We’ll start at the top and work our way down. These are only suggestions, to let you know what is possible, and how I think of things. We think of the face in three sections: forehead, midface and lower face. One of the most feminizing effects happens in the forehead. We can move the hairline forward. Bone work is required to make a feminine skull.” Page rolled his stool backward to retrieve the model skull sitting on the counter behind him. He held the skull in his left hand and used the index finger on his right hand to show Leanne how the frontal bone could be reduced. “By burring down this area [above the eyes] instead of removing the bone, we can retain the angle from your forehead to your nose. Patients with ‘the works’ often look worked on. That is not what I want to give you. When you lose the natural transition from the forehead to the nose you don’t look good as a man or woman.”

This is a direct defense of his surgical approach against Howard’s more aggressive style. Page runs the pad of his thumb across the orbital ridge above Leanne’s left eye as she looks at her face in the mirror. “Reducing this will give you the feminine appearance. It gives you sex appeal. That’s the approach we’re going for. Passing as a woman takes more than what I do: it’s about hormones, behaviors, dress, makeup, voice. What I do is just one piece of the pie. Now, when I’m in doing the forehead contouring I can remove some frown muscle, which would be nice for you. At the same time I can take away the peaks at the hairline.” Page uses the wooden handle of a long cotton swab to trace along the temporal baldness of Leanne’s hairline.

Leanne: “I’ll need a wig anyway. I had hair transplants all through there but they failed.”

Page: “This dark space is the frontal sinus.” He points at the sinus on the x-ray using a yellow wooden pencil. “In my mind, the most desirable female forehead is convex horizontally and vertically; it is not vertical. I could take you back 8mm. The 15mm you currently are minus 8 equals 7mm. That is where I want you. If you had an x chromosome rather than the y you were born with, that is where you’d be. You got this…” indicating the brow prominence of the frontal sinus “…when you were 14, 15, 16 years old. You have what I call a type III forehead.” Explains how he’ll remove the frontal wall, and form patches to wire back into the exposed sinuses. “When taking out the frontal sinus you have two holes left: if you sneeze you make a bubble and if you sniff you make a dimple. That is good at the first cocktail party, but not the second. I take the bone I removed and make two small patches and wire them into place to close those sinuses. If someone just burred this down, they could only go about .5mm to 1mm.” This comment acknowledges the common approach by other surgeons to burr the bone rather than unroof it. It is both descriptive and defensive.

Page: “Okay. Your nose is really necessary to do. We can take the hump out of the dorsum and decrease the projection some. The upper lip could be shortened. That is really common in feminization surgery. It’ll be like when you were younger.” Page presses the wooden handle of the cotton swab just beneath Leanne’s nose, causing her upper lip to rise on the surface of her teeth and allowing more tooth to show. “In terms of the jaw, I would leave it alone.”

Leanna: “Really?”

Page: “Beautiful women have a strong jaw line. For you, brow lift, cheek implants possibly to give you some more fullness in the midface, and nose for sure. If you’d like to see what this would look like, we can image you and give you a better idea of what I am talking about.” Page led Leanne to a small, dimly-lit room attached to the exam room. There was space for only two distinct positions in this room, so I observed in the doorway, looking over Page’s shoulder as he worked. Page was seated at a laptop computer equipped with a special trackpad that allowed him to move a stylus along the pad controlling the computer display. His laptop was connected to a digital camera mounted on an adjustable stand. Leanne sat at the opposite end of the room in front of a grey backdrop. Page took six digital photos of Leanne’s (non-smiling) face: (1) looking straight ahead at the camera; (2) turning her whole body such that her face is in ¾ view; (3) profile; (4) ¾ view facing the other direction; (5) opposite profile; (6) facing forward but looking straight up, a ‘worm’s eye view’. Page invited Leanne to pull her stool up beside his so that she could watch as he altered the photos he just took.

Page: “I try to do things with imaging that I can do during surgery so that it’s not unrealistic. One thing would be to decrease projection. Come over here and I’ll show you what I mean.” Leanne got up from her seat in front of the drape and sat beside Page in front of the computer. Using the stylus on the trackpad, Page selected the areas that he could reduce: frontal bossing, orbital bossing, and nose projection. He circled each of these areas on the profile image because this image produces the most noticeable contrast. Once these areas were selected, Page drug the stylus back and forth across the trackpad. As he moved from left to right across the pad, the nose, forehead, and orbital bossing all reduced in unison. As he moved back to the left, they ‘grew’ back to their original (current) size. Leanne watched this in silence for a few seconds. It was clear that she was not seeing all that she hoped to see. Page was quick to step in. “I am kind of limited in what I can show here. I mean, you have to imagine what it would look like once your facial hair is gone [she had a day’s growth of beard]. You’ve also got some skin damage that you should really work on. I’d say the most important thing you can do for yourself between now and any surgery would be to start a skin-care regimen. Work on that sun damage and some of the brown areas, the wrinkles around the eyes.” Page indicated these problem areas on the computerized image of her face. “I work with an esthetician right upstairs. I can set an appointment for you if you want. I really do think that is really important. You know, beautiful women have beautiful skin.”

Leanna: “Yeah, I spent almost 20 years in Arizona. I have a lot of sun damage.”

Page: “Here are some other patients I have operated on. Maybe these will give you a better idea of the changes I am talking about.” Page opened a file on the laptop with several pre-op and post-op images of his patients. He flipped through the images, describing the procedures involved. “Here you can see I did the nose…Here you can see the reduced bossing; that really opens up the eyes… Here you can see the difference that a brow lift really makes. She looks great…” This didn’t seem to alleviate Leanne’s sense of disappointment with her own images.

Leanna: “These people look much more feminine than what I see when we look at me. I have my wig with me. Can I put it on and you can take the pictures again? That might give us a better idea of how this is going to look.” She crouches down and pulls her wig out of her briefcase. It is a bit disheveled and needs brushing. Leanne does her best to place the reddish-brown shag cut wig on her head, but there are no mirrors in this room. In addition to the contrast produced by her businessman’s attire, the wig is not quite on correctly. To my mind, this photo session has just changed quite radically. Page appeared somewhat reluctant, but he agreed to take a new profile photo on which to make the digital modifications. One of the qualities that made the wig desirable is particularly problematic during the photo shoot: it obscures her forehead and brow.

Page: “Could you pull your hair back so I can see your forehead?” Page took the photo. Leanne resumed her seat beside him at the computer and watched as he made the same alterations to the new photo as he had to the previous set. The addition of the wig did not produce the effect she’d hoped for. Page reiterated the importance of starting a skin-care regimen and beginning electrolysis on her face. “I think those changes could make a big difference for you. Let’s go talk to my office manager, Hannah. She can give you a better idea about prices and we can look at some more images.” The pair left the room and began flipping through a photo album in Hannah’s office.

Leanna: “Do you think I could ever look this good? I’m worried about going through all of this and looking as ridiculous as I do now.”

It is clear from these two representative appointments that though these doctors punitively share a common goal—the ‘feminization’ of their patients—what ‘feminine’ means to each of theme is quite distinct. Their approaches to the project of ‘feminization’ determine both what each doctor identifies as the problematically ‘masculine’ and the desirably ‘feminine’ and how they do so.

SURGERY DAY

For most patients I interviewed, the anticipation of and preparation for surgery had given significant shape to their personal, professional, financial and emotional lives for many months. For others, many (many) years. By the time they’d made the trip to the surgeon’s office, they had come to think of Facial Feminization Surgery as the event that would mark the difference between the life they had and the life they wanted.

It would, they hoped, be the end of a deep longing for transformation. Structured by the future goal of surgery, for these patients the present had collapsed into a seemingly interminable time before surgery. It was a continuation of the past experience of bodily dissatisfaction and disaffection into the almost, the can’t wait, the before to which every day following surgery would be the after.

Dr. Howard pointed to a chair in the hallway outside his office. “I’ll walk by that spot at exactly 7:25am. If you’re there, you’re welcome to join me in the OR. If you’re not, you’re not.”

Patient: Rosalind

Rosalind, whose surgery is described in the interstices of this prose—had traveled from Wales to undergo surgery with Dr. Howard. When we met on the afternoon before her surgery, she was feeling very anxious. When I asked her about the source of her anxiety, she said that it was not the operation itself that worried her. Rather, she was nervous about the postoperative recovery period.

“I’m scared to death. A week before my plane ride I started praying for British Airways to go on strike. I saw a patient at the Cocoon House [Howard’s private recovery and convalescent facility, all gendered and natural metaphors intended] all bruised and bandaged and I’ve been walking around trying to think, ‘Why am I doing this?’”

Rosalind had hoped to make this trip five years before, but financial issues had delayed her plans. For her, as for all patients who shared their stories with me, arriving in this office was the culmination of a long process of self-discovery.

“At 25 years old my hair started to fall out and I thought, ‘Oh no! I haven’t decided whether I want to transition!’ I tried topical creams and things to try to keep my hair and I became pretty obsessed with it. Then I started thinking, ‘Wait, is the problem that you’re going bald or that you’re transgendered?’”

She began feminizing hormones in 1999, and hoped that their effects would be enough to ease the anxieties she had about her appearance. She was not ready to commit to surgical alterations at that time because, she explained, she simply could not accept the idea that she was a transwoman.

“I still thought I could cure myself of being transgendered,”

In spite of this desire to be ‘cured,’ she began taking tentative steps toward ‘accentuating the feminine in [her] face.’ She underwent facial electrolysis that had produced permanent pockmarks on her cheeks and chin, only exacerbating her self-consciousness about her appearance. In 2002 she had surgery to remove her thyroid cartilage (Adam’s Apple) and, shortly thereafter, a surgery to reduce the size of her nose.

“That only made my brow look bigger,” she lamented. “My brow is my major concern. I need my nose to match my brow. I have a kind of Neanderthal brow. I want to do my jaw too, but I may have to skip that for now depending on whether I can get the money together. I was kind of hoping he wouldn’t say that I needed to do my jaw, but I know it needs to be done.”

Rosalind knew that her decision to have surgery would cause complications in her work and family life. She presented as male at work and at family events, and planned to continue doing so at least until her elderly father passed away. The thought of disappointing him with the fact of her female identity was unthinkable to her. She worked in the building and construction industry in a fairly small town and, for her, living full-time as a woman was simply not an option. Worries about work and personal consequences had kept her from making many changes both to her life and to her body, but she had finally decided that such concerns could no longer determine her choices.

“If I have to think too much about what others think, I’ll never do it. I have to do this for me. I’ve spent 25 years of my life thinking about not looking like I do now. I want that to go away. Constant thinking about that ruins the mind. After this I’ll be able to think of other things, everyday things.”

Rosalind told me, as did many patients, that it was during puberty that she began to hate her face. As she watched her ‘button nose’ give way to the oversized nose of a pubescent boy, she taught herself how to wash her face and brush her teeth in the dark.

“My mum would go into the bathroom after me and always wonder why the blinds were closed.”

It was easier for her to re-learn these daily habits than to deal with the look of her changing face in the mirror. This was the beginning of the long story that brought her all the way from Wales to have surgery with Dr. Howard some 25 years later.

I was tired and anxious when I joined Howard the next morning. We walked briskly down the hallway to the surgical wing, he in a shirt and tie covered by his long white coat, me in my canvas jacket and shoulder bag. I saw the loafers on his feet and felt like an idiot in my running shoes—I thought they’d be best for endurance.

After so much discussion of looks and numbers and desires and abilities, it is in the operating room that faces are reconstructed. It is here, as they say, that the rubber meets the road. While for surgeons the operation is an event that has been routinized and repeated hundreds or even thousands of times over, for the patient, the operation is something absolutely singular—assuming all goes well. Over the course of the surgery (up to nearly eleven hours in the case of a “full face” operation), the patient’s skin, bone and cartilage is pushed, pulled, burred, sawed, cut, cracked, tucked and sutured. In the end a strikingly new face may emerge; one whose production is guided by the hope that its new form will enable a coincidence of the patient’s self and body for perhaps the first time in a very, very long time.

Facial Feminization Surgery is guided by a hope for phenomenological integration—the creation of a body that (re)presents the self. Though the technical work of surgery is something that patients do not experience in real time, its effect animates their anticipation of a better life through the body as a better and truer thing.

He brought me to the charge nurse’s desk. I was to register my name in the vendor’s logbook. Dr. Howard offered me a pen. “You can keep it,” he said. “It’s got my name on it.” I signed in quickly and was given a sticky nametag. I followed Howard into the physicians’ locker room where I was shown for the first—and last— time where to find the supplies I would need to enter the OR. I slid my bag and jacket into an open locker.

For those who desire physical transformation, the operating room is place that symbolizes corporeal change and all the attendant hopes of what that change will bring. In addition to the physical transformations enacted here, the operating room is also the scene of an encounter between patients and surgeons that is structured by a common conception of the body or, more specifically here, the face. For these two people in this place, the patient’s face is a material thing. It is not the irreducible site of personhood, the distinct shape of which makes us individuals; it is a series of structures whose problematic characteristics can be rectified.

These structures do not necessarily map onto or even remotely relate to the social or personal identity that the face is typically taken to be. That is just the point: this face is not her face. Not yet at least. The preoperative face is simple, disinterested material for the surgeon who cuts into and reshapes its parts, and it also is this for the patient whose experience of her face as something disloyal—as non-coincident with her self—has motivated her arrival here.

This is a distinct vision of the body shared between the surgeon and the patient, two people who have arrived together in the operating room precisely in order to alter it. We grabbed blue paper caps from a shelf near the door to the hallway. He folded the bottom rim of his cap upward in order to pull it down snugly before tying the white paper straps behind his head. I did the same. We were ready. Howard swung open the door and we headed to OR 3, his regular room. He handed me a surgical mask as we walked through the scrub room and into the OR where Rosalind was laying on the table being prepped by the Circulating Nurse (CN).

Dr. Howard went immediately to greet the patient. He caressed her forearm and assured her that everything would go well and that she would look beautiful. I! couldn’t stop staring at her fingernails: cotton candy pink against the blue and white striped blanked that covered her. Howard stayed by her head until she was under anesthesia. The moment the patient was unconscious, the feel of the operating room changed. With the presence of a guest no longer observed—I certainly did not count as such—everyone in the OR began their tasks in haste.

“This is Rosalind Mitchell, 37 years old. We’re doing her forehead and nose today. She wanted to do the chin and jaw but her credit card didn’t come through. Says she’ll be back for those in the fall. This should take four and a half hours. She has no allergies and is on no medication.” Confirming! that all parties were in agreement, he began to prepare the first site: the forehead. Sitting on his stool at the end of the table, he began to comb and gather Rosalind’s long hair in rubber bands. Once the site was isolated, he shaved a one inch wide track through her hair, combed out the loose pieces and dropped them into a biohazard bucket. He injected the incision site with local anesthetic and then left the room to scrub in. While he was out, the CN sterilized the forehead site with soap and water and then with iodine that dripped in deep brown yellow drops through her hair and into towels on the floor. The doctor returned with his clean and dripping hands held at chest level. The CN helped him into his gown and gloves

The process of making a masculine face into a feminine one only rarely involves addition (of bone substance or implants). Instead, making feminine is almost always a process removing that which is masculine to reveal the feminine beneath. The masculine is a problem of excess: the jaw is too wide, the forehead too long and too prominent, the chin too square, the upper lip too long. Whereas genital sex reassignment involves rearranging and repurposing body parts in order to make new ones, like mastectomy for female-to-males, Facial Feminization Surgery is essentially about taking parts of the body away.

For this reason it can quite literally be read as carving away the outer unwanted body to reveal the self within. The metaphorical representation of “a woman trapped in a man’s body” is, in other words, rendered quite literally here. In this OR scene, the ontological and phenomenological statuses of the body and self are radically uncertain.

The surgeon further isolated the incision site by draping sterile blue towels over the patient’s hair and securing them in place with skin staples. Fully draped from head to toe, only the patient’s face was showing. One stitch was placed in each of her eyelids—sutures are necessary to keep her eyes closed (and thus moist) because her face will be tugged and moved quite a lot throughout the procedure. All was ready to proceed. Dr. Howard announced the time of the first incision; the CN recorded it on the whiteboard on the wall, and the operation began.

To reduce the frontal sinus that accounts for the ‘male brow,’ an incision is made beginning at each ear and meeting at the center of the head, just behind the hairline. The skin of the forehead—from hairline to orbits (eye sockets)—is folded down over the eyes, revealing the smooth and very white frontal bone below.

The long, thin wooden handle of a cotton swab is broken in half, dipped in methylene blue and used to mark the frontal bone on either side. The periosteum (a membrane that lines the outer surface of bones) is cut at these lines and scraped forward into the orbits at the top of the nose bridge. Glancing at the cephalograms illuminated on the wall\mounted light board, the doctor marks the frontal bone with a yellow wooden pencil.

The burr tool whirs like a dental drill as it grinds off the undesirable bony prominence's above the orbits. Bone particles fly off the burr as it spins. They catch in the cloth and paper that covers the patient and in the folds of my scrubs as I lean in. By the end of the procedure they will become dry chalky dust. An oscillating saw blade replaces the burr tool and a cut is made along the pencil drawn lines. The cut bone is pried up out of its place, making a dull cracking sound as it is dislodged from the skull. The Surgical Tech (ST) collects this irregular oblong piece (about two inches across at its widest point) and sets it in the white plastic lid of a sample cup for safekeeping. The frontal sinus is revealed. Everyone’s frontal sinus (95% of us have one) is structured differently. Rosalind’s is internally asymmetrical, divided by thin walls of bone into three distinct cavities. Frontal sinuses are usually empty, but sometimes brain matter has protruded into them. “Is that brain or sinus? Not sure. Let’s go slow.”