#eastern american native plants

Text

Tulip Poplar Flower - Liriodendron tulipifera

#took me so long to find one low enough#these trees are some of the tallest in the forest and first stage succession trees in this region#Liriodendron tulipifera#tulip poplar#eastern american native plants#trees#magnolia family#photographers on tumblr#original phography#spring

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

some art ❤️

Designing my friend a Golden Kamuy Skateboard deck! Only have the sketch half way done so this is all i got at the moment.

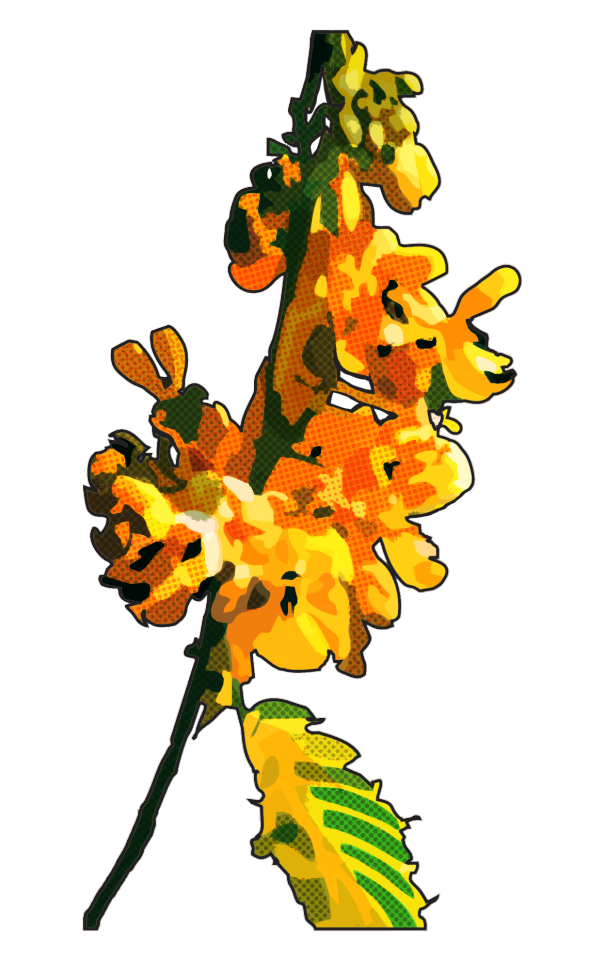

I’m working with Newfields’ horticulture department (also known as The IMA/The Indianapolis Museum of Art) to design some graphics of native Hoosier plants in their pollinator garden. The yellow flower is the American Senna and the pink one is the Eastern Red Columbine.

#art#artist#fanart#anime#manga#gay#ima#newfields#indianapolis museum of art#american senna#eastern red columbine#flowers#native plants#hoosier#plant native#pollinators#pollinator garden#golden kamuy#sugimoto saichi#saichi sugimoto#asirpa#shiraishi yoshitake#yoshitake shiraishi#skateboarding#skater

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Succulents Part 7--Opuntia humifusa

Succulents are a wide variety of plants, spanning multiple orders. Some have succulent leaves while others have succulent stems. Cactuses are succulents, but not all succulents are cactuses. Defining what exactly makes a succulent is a little tricky. For example, cabbage leaves are considered by some to be succulent, but tulip and onion leaves apparently aren't.

All photos mine. Unedited.

This is a single species post as it's the only opuntia I have photos on hand of (single specimen, rather, as this is all the same plant). Anyway, it's a succulent by virtue of being a cactus. I'm not even sure you really differentiate leaf from stem on a cactus. This cactus I've grown for several years now, and last summer was her first flowering season! I hope she does it again this year too. This species of cactus can be grown outdoors in Ontario and the rest of its native range since it is hardy to cold weather. :)

#succulent plants#succulents#flowers#my photos#photography#blackswallowtailbutterfly#yellow flowers#Opuntia humifusa#devil's tongue#garden flowers#cactus#cactus flowers#Opuntia#my garden#prickly pear#eastern prickly pear#native North American plant species

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parthenium integrifolium / Wild Quinine at the Sarah P. Duke Gardens at Duke University in Durham, NC

#Parthenium integrifolium#Wild Quinine#American feverfew#Eastern feverfew#Feverfew#Native plants#Native flowers#Nature photography#Flowers#Sarah P. Duke Gardens#Duke Gardens#Duke University#Durham#Durham NC#North Carolina

1 note

·

View note

Text

What i've been learning thru my research is that Lawn Culture and laws against "weeds" in America are deeply connected to anxieties about "undesirable" people.

I read this essay called "Controlling the Weed Nuisance in Turn-of-the-century American Cities" by Zachary J. S. Falck and it discusses how the late 1800's and early 1900's created ideal habitats for weeds with urban expansion, railroads, the colonization of more territory, and the like.

Around this time, laws requiring the destruction of "weeds" were passed in many American cities. These weedy plants were viewed as "filth" and literally disease-causing—in the 1880's in St. Louis, a newspaper reported that weeds infected school children with typhoid, diphtheria, and scarlet fever.

Weeds were also seen as "conducive to immorality" by promoting the presence of "tramps and idlers." People thought wild growing plants would "shelter" threatening criminals. Weeds were heavily associated with poverty and immortality. Panic about them spiked strongly after malaria and typhoid outbreaks.

To make things even wilder, one of the main weeds the legal turmoil and public anxiety centered upon was actually the sunflower. Milkweed was also a major "undesirable" weed and a major target of laws mandating the destruction of weeds.

The major explosion in weed-control law being put forth and enforced happened around 1905-1910. And I formed a hypothesis—I had this abrupt remembrance of something I studied in a history class in college. I thought to myself, I bet this coincides with a major wave of immigration to the USA.

Bingo. 1907 was the peak of European immigration. We must keep in mind that these people were not "white" in the exact way that is recognized today. From what I remember from my history classes, Eastern European people were very much feared as criminals and potential communists. Wikipedia elaborates that the Immigration Act of 1924 was meant to restrict Jewish, Slavic, and Italian people from entering the country, and that the major wave of immigration among them began in the 1890s. Almost perfectly coinciding with the "weed nuisance" panic. (The Immigration Act of 1917 also banned intellectually disabled people, gay people, anarchists, and people from Asia, except for Chinese people...who were only excluded because they were already banned since 1880.)

From this evidence, I would guess that our aesthetics and views about "weeds" emerged from the convergence of two things:

First, we were obliterating native ecosystems by colonizing them and violently displacing their caretakers, then running roughshod over them with poorly informed agricultural and horticultural techniques, as well as constructing lots of cities and railroads, creating the ideal circumstances for weeds.

Second, lots of immigrants were entering the country, and xenophobia and racism lent itself to fears of "criminals" "tramps" and other "undesirable" people, leading to a desire to forcefully impose order and push out the "Other." I am not inventing a connection—undesirable people and undesirable weeds were frequently compared in these times.

And this was at the very beginnings of the eugenics movement, wherein supposedly "inferior" and poor or racialized people were described in a manner much the same as "weeds," particularly supposedly "breeding" much faster than other people.

There is another connection that the essay doesn't bring up, but that is very clear to me. Weeds are in fact plants of the poor and of immigrants, because they are often medicinal and food plants for people on the margins, hanging out around human habitation like semi-domesticated cats around granaries in the ancient Near East.

My Appalachian ancestors ate pokeweed, Phytolacca americana. The plant is toxic, but poor people in the South would gather the plant's young leaves and boil them three times to get the poison out, then eat them as "poke salad." Pokeweed is a weed that grows readily on roadsides and in vacant lots.

In some parts of the world, it is grown as an ornamental plant for its huge, tropical-looking leaves and magenta stems. But my mom hates the stuff. "Cut that down," she says, "it makes us look like rednecks."

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

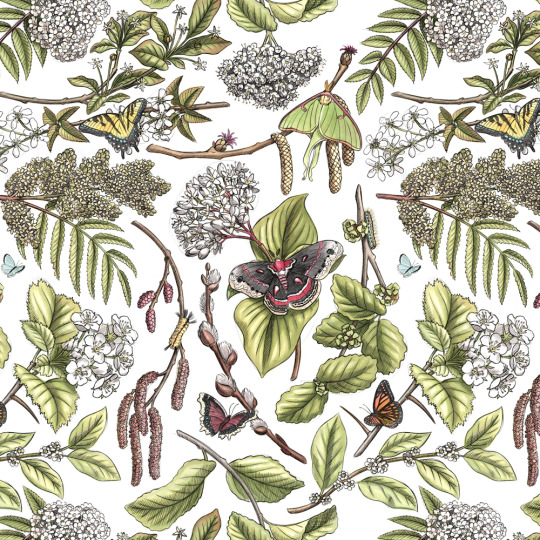

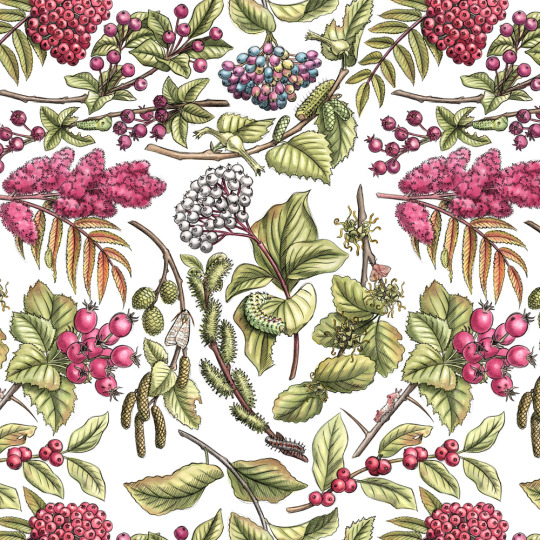

New England native shrub patterns, in spring and autumn. Featuring some lepidoptera species hosted by the plants, in their larval and adult forms. For a project that's been 4 years in the works… More details soon.

Mountain Holly

Northern Wild Raisin

American Mountain Ash

Shadbush with Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly

Beaked Hazelnut with Luna Moth

Staghorn Sumac with Spring Azure Butterfly

Red-osier Dogwood with Cecropia Moth

American Witch Hazel with Eastern Tent Moth

Pussy Willow with Mourning Cloak Butterfly

Gray Alder with Banded Tussock Moth

Big-fruit Hawthorn with Viceroy Butterfly

Winterberry Holly

#sketch#watercolor#illustration#art#design#pattern#plants#shrubs#native plants#nature#naturalist#nature journal#jada fitch#maine#new england#wildflowers#berries#lepidoptera#drawing#pencil#moths#butterflies#butterfly#moth#caterpillar#larvae#artist#maine illustrator#nature art#field sketch

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Larix laricina, commonly known as tamarack, hackmatack, and Eastern, red, black or American larch.

L. laricina is native to boreal and eastern temperate North America (Nature Serve), persisting right up to the northern treeline. It frequently grows in or at the edges of wetlands (swamps, fens, marshes, and riparian areas), but can tolerate a wide range of substrates and moisture. For a good overview of the species, check out this link.

It's one of those plants that can be a lightbulb moment for some people, inspiring them to reconsider basic assumptions about the way we divide up the natural world. When we learn about trees, many of us learn that there's two basic "types": deciduous trees and conifer trees. We are often told that deciduous trees are broad leaved and lose their leaves in the fall and that trees with needles don't.

Tamarack 'breaks' that; it is a deciduous conifer. Rightly, the language we are taught should be that there are deciduous and evergreen trees, that there are conifers and broad-leaf trees, and these categories can mix and match. (Of course, the trees haven't read the rules, so I wouldn't be the least bit surprised to find out there is a broadleaf coniferous gymnosperm--exceptions ARE the rule in ecology!)

#i could go on about this tree but i think the post would get too long#theyre a very cool boreal species!!!#tamarack#larix laricina#plants#ecology#nature#I think it's fitting for the first day's plant to be the one in my profile pic!

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's my (probably only, sadly) post for Solarpunk Aesthetic Week! Originally made for Andrewism's 2023 Solarpunk Art Collab!

This digital painting depicts the Southern Great Lakes Ecoregion, within the Interior Plateau & Southern Great Lakes Forests Bioregion, within the Temperate Broadleaf and Mixed Forest Biome.

I chose a suburban setting for this piece because I've not yet seen a Solarpunk artwork that features this. I'm aware of the problems with the suburbs, but it seems to me more sustainable to try to adapt them than to demolish them and start over. So instead of lawns I've depicted beds of native Indiana plants, including but not limited to:

Amsonia Tabernaemontana (Eastern Bluestar)

Spartina Pectinata (Prairie Cordgrass)

Echinacea Purpurea (Purple Coneflower.

The roofs of the houses are either white to help reflect heat, or green roofs. Some of the houses are equipped with solar panels on the south sides, and one is shown with a greenhouse on that side as well.

While perhaps not explicitly ecologically focused, I have shown there to be more art in this setting than is usually found in american suburbia. The sidewalk has a mural painted with hydrochromic paint, which only appears while it is raining. The houses are painted bright colors (white or greige is considered 'Normal' ) and are occasionally decorated with murals.

This particular area is among the cloudiest in the so-called U.S.A. To reflect that, the weather is overcast and it is currently raining.

Hope y'all enjoy this, and Happy Solarpunk Aesthetic Week!

381 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything You Need to Know About Veggies and Fruits: Cranberries

Cranberry (Vaccinium Macrocarpon)

*Kitchen *Medical *Feminine

Folks Names: Bog fruit, Marshworts

Planet: Mars

Element: Water (juice), Fire (berry)

Deities: Astarte, Marjatta,

Abilities: Healing, Protection, Love, Lust, Positive Energy, Courage, Passion, Action

Characteristics: Native to Eastern North America and northern Asia. Small, slender, evergreen shrub growing to 1 ft with oval, dark green leaves, pink flowers and round/slightly pear-shaped red berries.

History: This jewel-toned gem of the bog is native to North America and a traditional food from Samhain through Yule. Its association with the American Thanksgiving meal is long rooted in tradition, but there is no historical evidence proving it was actually served at that first Thanksgiving celebrated by the Pilgrims. Despite this, cranberry something or other is commonly found on Thanksgiving and Christmas feast tables all across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Cranberry garlands made by stringing hundreds of the hard round red berries with a needle onto a long sturdy string is a traditional Christmas decoration. It is believed that cranberries got their name due to cranes always eating them and the blossoms of the berries look like the head of cranes. It is considered a sacred fruit in some indigenous circles such as Algonquian and Iroquois.

How to Grow:

Easy to Plant: Relatively

Rating: Moderate

Seeds accessible: Sometimes seasonal

How to Plant Cranberries

Video Guide

Where to Buy Seeds

Magical Properties

Can be used as a substitute for wine

Dried cranberries can be used in a charm to honor the wisdom of elders or as an offering to ancestors

It’s bright color signals energy, passion, courage, rejuvenation and rebirth

Can lend abundance, love and healing in kitchen spells

Since they are from the bog, it said to be feared by evil spirits and can offer protection

Placing a bowl of cranberries under one’s bed can restore depleted energy and cure an illness

Drinking the juice with your partner on a dark moon can keep your relationship free of trouble and continue to go strong

Can help link wisdom and guidance of ancestors

Can be utilized in energy cleansing rituals to remove negative energies from the aura

Is said to restore chakra alignment balance and create harmony

Burning bundles of cranberry stems can purify the energy of space and promote spiritual well-being during rituals and meditating

Medical Usage:

A classic remedy for urinary tract infections and can prevent and treat problems such as cystitis and urethritis

Can help to disinfect the urinary tubules and may be taken for problems associated with poor urinary flow such as enlarged prostate and blade infections

Can be used long term to prevent the development of urinary stones

Research in 1994 showed that cranberry juice helped really well with UTIs in women

Sources

#witch community#witchblr#witchcraft#paganblr#nature#witchcraft 101#plants and herbs#green witch#occulltism#cranberries#cranberry juice#cranberry sauce#kitchen witch#thanksgiving#fruits and vegetables#berries#baby witch

90 notes

·

View notes

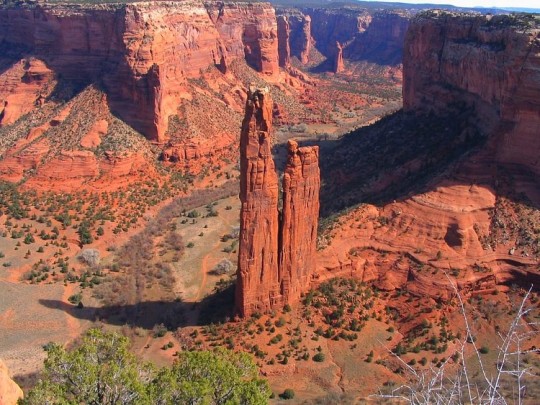

Photo

Canyon de Chelly

Canyon de Chelly or Canyon de Chelly National Monument is a protected site that contains the remains of 5,000 years of Native American inhabitation. Canyon de Chelly is located in the northeastern portion of the US state of Arizona within the Navajo Nation and not too far from the border with neighboring New Mexico. It is located 472 km (293 miles) northwest of Phoenix, Arizona. Canyon de Chelly is unique in the United States as it preserves the ruins and rock art of indigenous peoples that lived in the region for centuries - the Ancestral Puebloans and the Navajo. Canyon de Chelly has been recognized as a US National Monument since 1931 CE, and it is one of the most visited National Monuments in the United States today.

Geography & Prehistory

The etymology of Canyon de Chelly's name is unusual in the U.S. Southwest as it initially appears to resemble French rather than the more ubiquitous Spanish. "Chelly" is actually derived from the Navajo word tseg, which means "rock canyon" or "in a canyon." Spanish explorers and government officials began to utilize a "Chelly,” “Chegui,” and even "Chelle" in order to try to replicate the Navajo word in the early 1800s CE, which eventually was standardized to “de Chelly” by the middle of the 19th century CE.

Canyon de Chelly lies very close to Chinle, Arizona, and it is located between the Ancestral Puebloan ruins of Betakin and Kiet Siel in the west and the grand structures of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico in the east. Canyon de Chelly, as a National Monument, covers 83,840 acres (339.3 km2; 131.0 sq miles) of land that is currently owned by the Navajo tribe. Spectacularly situated on the Colorado Plateau near the Four Corner's Region, Canyon de Chelly sits at an elevation of over 1829 m (6,000 ft) and bisects the Defiance Plateau in eastern Arizona. The tributaries of the Chinle Creek, which runs through Canyon de Chelly and originates in the Chuska Mountains, have carved the rock and landscape for thousands of years, creating red cliffs that rise up an additional 305 m (1000 ft). The National Monument extends into the canyons of de Chelly, del Muerto, and Monument.

Canyon de Chelly is one of the longest continuously inhabited places anywhere in North America, and archaeologists believe that human settlement in the canyon dates back some 5,000 years. Ancient prehistoric tribes and peoples utilized the canyon while hunting and migrating seasonally, but they did not construct permanent settlements within the canyon. Nonetheless, these prehistoric peoples did leave etchings on stones and on canyon walls throughout what is now Canyon de Chelly. Around c. 200-100 BCE, peoples following a semi-agricultural and sedentary way of life began to inhabit the canyon. (Archaeologists refer to these peoples as "Basketmakers." They are considered the ancestors to the Ancestral Puebloan Peoples.) While they still hunted and gathered like their prehistoric forebears, they also farmed the land where fertile, growing corn, beans, squash, and other small crops. It is also known that they grew cotton for textile production. Yucca and grama grass have grown in the canyon for several millennia, and indigenous people utilized these plants when making baskets, sandals, and various types of mats. Prickly pear cactus (Opuntia cactaceae) and pinyon are also found throughout Canyon de Chelly, the latter of which provided an important source of food for indigenous peoples in autumn and winter. Fish are found in Canyon de Chelly's tributaries, and large and small game frequent the canyon.

Continue reading...

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone asked: Ooooh, Do you know of any deer resistant types of, well anything? I haven't been able to grow so much as a tomato cause the suckers here know no one's gonna cap their fluffy ass

(And I don’t know how to do this as a reply to a question thing, because I am old and the buttons have all moved.)

But yes! There are many deer-resistant plants, though very few deer-proof ones, because a sufficiently hungry deer will eat anything, including small animals. If you are somewhere with an overpopulation of deer—i.e. most of the Eastern Seaboard—during a hard winter or any other lean time, deer will go for anything they can get their teeth into. And even on moderately toxic stuff, they’ll often just bite flowers off and spit them out. Deer are dicks.

That said, from my own experience, almost all the Carex sedges are deer-resistant, I’ve had good luck with River Oats, they generally leave Rattlesnake Master and yuccas alone, Amsonia is usually a safe bet, most of the asters including Carolina climbing aster, oakleaf hydrangea, goldenrod, Joe Pye Weed, most of the glorious Salvia genus, our native passionflowers, the fabulous and underused genus Pycanthemum, American spikenard…there’s a lot.

This does not, however, cover tomatoes, peppers, or other stuff you might actually want to grow to eat. For that, all I can really offer is a chicken wire cage. I fenced in my whole veggie garden with deer netting, and it works great, but that was a whole bigass project.

There are various forms of home remedy/folk magic that people swear by. None of them have ever worked very long for me. The only thing that DID work, weirdly enough, was getting chickens. Too much noise and movement in the crepuscular hours, I suspect, and a bantam rooster yelling at the deer to come fight him, do it, he’ll kill ‘em, he’ll tear off their head and shit down the stump, just try him! completely eliminated deer incursions in our front yard. Go figure.

419 notes

·

View notes

Text

Winged/Shining Sumac - Rhus Copallina

Sumacs are typically thought of as weedy shrubs. However in nature, they serve as a great incubator for forest regeneration, a pioneer species if you will. Sumac species were used for this purpose to jumpstart forest growth on Pier 1 adjacent to the Brooklyn Bridge, allowing oak saplings to regenerate within the thicket and open canopy.

The winged Sumac is different than other Sumacs because it has pinnately compound leaves (the little leaf on the 'stem' portion). The fruit also droops downward rather than standing erect as well, pictured above as green when immature but ripens a dark red color. The leaves also have a lovely sheen to them that is not poisonous to touch, unlike it's swamp dweller sister "poison sumac" (distinguished by red branches and white berries).

Sumacs are spread via bird droppings so typically are found in heavily disturbed, sandy, rocky but moist locations, think of a road side, cliffs edge, or maritime forest. The specimens above were seen at Sandyhook, they are native to eastern America from mexico to Ontario. This plant usually forms dense crooked stem thickets from a singular root structure when disturbed, they can get to around 20 ft tall, and are a pretty beneficial species for birds and insects.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

So speaking of plant variability and specifically Coreopsis lanceolata (lanceleaf tickseed), mine have had an interesting development:

Exhibit A

Exhibit B

This is new. They've never looked like this before, and indeed all of the rest of the currently open flowers look like this:

Exhibits C-E

Now, many Coreopsis varieties you'll find in the garden centre will have that red inner part but you don't typically find it on the regular plants. It's a mutation. These flowers are readily pollinated and many of the current plants growing are seeded from my original plant, which itself is still very much alive. And this tells me one of two things has happened.

1) Somewhere in the neighbourhood, someone has planted the garden variety and it has hybridized with mine. I don't mind this too much since as far as I can tell the garden varieties are all cultivars of native species.

2) It's just a spontaneous mutation! Which is cool as hell. And I mean the first to occur with such colouration probably was a spontaneous mutation, which a gardener or whomever thought looked cool so kept breeding it that way. I will not be doing that, they can do it themselves if they so wish, but very neat nonetheless.

#Coreopsis lanceolata#lanceleaf tickseed#flowers#mutation#gardening#native plants#North American native plant species#native plant garden#native plants of eastern North America#Carolinian Canada

1 note

·

View note

Text

American Water Willow

Justicia americana

This native perennial loves water and can be found in very moist habitats. Its native range spans from Texas, throughout much of the eastern United States, to southeastern Canada. I found this blooming plant with purple and white bicolored flowers among a small colony growing in the middle of a shallow creek.

June 6, 2023

Shannon County, Missouri, USA

Olivia R. Myers

@oliviarosaline

#botany#plants#native plants#native flowers#flowers#nature#ozarks#the ozarks#naturecore#missouri#fairycore#wetlands#aquatic plants#wildflowers#wild flowers#goblincore#cottagecore#Justicia americana#Justicia#water willow#american water willow#Acanthaceae#Dianthera americana#Dianthera#Missouri nature#plants of the ozarks#plants of tumblr#hiking#exploring nature#plant photography

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

listen one of the major reasons i care so much about Arundinaria is that she's gotta be legit the most exciting rising star in the evolutionary world.

Flowering plants emerge like 100mil years ago, proceed to become the baddest bitches on planet earth with hundreds of thousands of species found in every environment.

from this lineage emerges the GRASS which, using the simple technologies of "Grow leafs from the bottom so the tops can get eaten and you can just keep a-goin'" and "Not die when stepped on" become the undisputed masters of the sunny and arid regions

From the lineage of the GRASSES. Emerges a grass that decides to step up its game and invent WOOD to become some sort of fucked up tree. This grass is known as WOODY BAMBOO and it kicks everybody's ass.

The woody bamboo is mostly thriving in Asia, but around 2mil years ago, a bamboo got LOST AS FUCK and accidentally went to NORTH AMERICA. It turns out the south-eastern part of North America is a downright luxurious climate for a bamboo and so the bamboo actually evolved into its own genus.

However, there was an ICE AGE that froze a bunch of North America and the bamboo was forced to a tiny edge of the Gulf Coast. Fortunately, the bamboo made a mutualistic symbiosis with HUMANS, which used controlled burning to create its ideal habitats in exchange for using the stems for a super-strong, versatile, flexible, water resistant material for literally everything. So basically it spread all throughout the Southeast of North America and formed its own habitat type, a bamboo forest environment known as a CANEBRAKE.

It's native North American bamboo, y'all. It's been reduced to 2% of its former extent and a lot of people don't even know it exists.

This plant is going places we can't let this shining streak of weird-ass plants with ideas just strange enough to work collapse because of a freak colonialism incident

Arundinaria gigantea my absolute beloved

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey I thought you might appreciate a heads up that the yellow-legged hornet (Vespa velutina) has been spotted in Savannah, Georgia. 😞

Nice. Well, not nice news. But glad that you thought of me. Thank you.

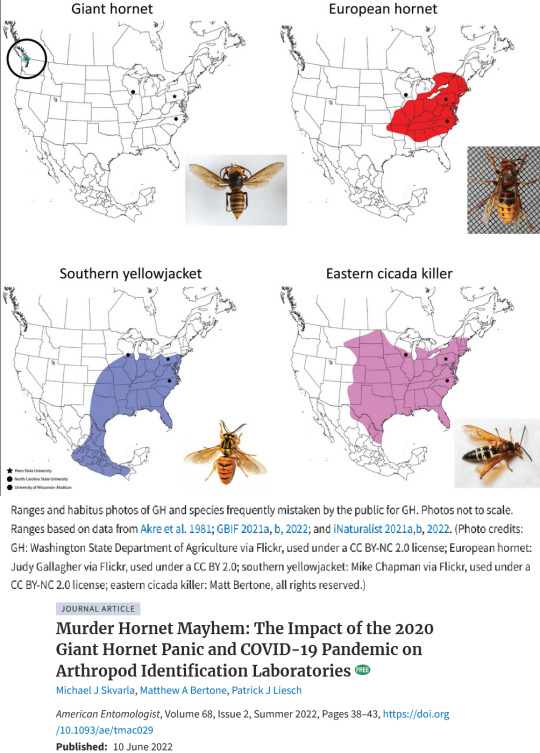

(For other people who have yet to fully embrace and explore their innate love of hornets, this Vespa velutina hornet is originally from Southeast Asia. This creature is closely related to Vespa mandarinia, the creature derisively referred to in the US as "murder hornet" or "Asian giant hornet", originally from South/East Asia, which is now apparently established near in the Salish Sea region near Bellingham, Vancouver, and Nanaimo.)

Here's a look at where the giant hornets now live in North America, along with the distribution of some other large hornets which might be mistaken as Vespa manadrinia/velutina:

The map was originally published in 2022 in American Entomologist, displaying distribution range of (non-native) giant hornet; (non-native) European hornet; (native) southern yellowjacket; and (native) eastern cicada killer. The article also identifies a few few other species which might be mistaken for "murder hornets": great golden digger wasp, bald-faced hornet, German yellowjacket, red-legged cannibal fly, and pigeon horntail. (Available to read for free online; article title in the source/caption beneath the map.)

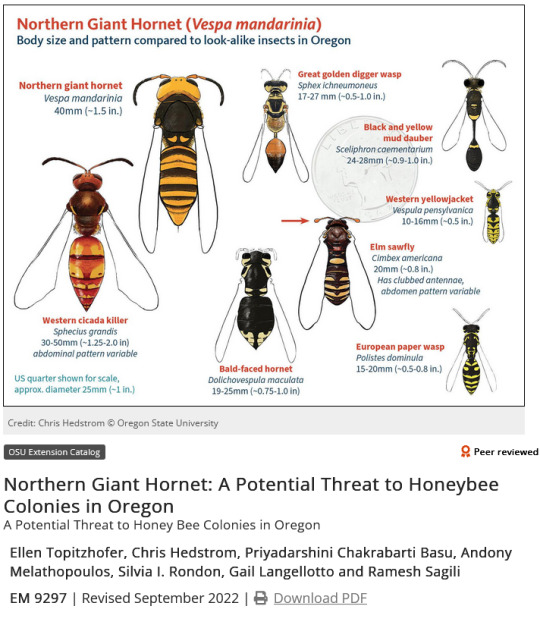

I've had many memorable encounters with large (native) bald-faced hornets in dense cedar-hemlock rainforest-y places. And coincidentally, the Pacific Northwest is also now apparently the North American home/homebase of Vespa mandarinia. So here are some other PNW wasps/hornets in comparison, from Oregon State University Extension Catalog (2022):

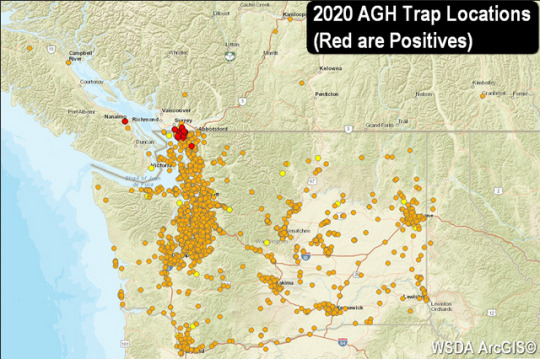

From 2020 research on potential dispersal of Vespa mandarinia over a couple of decades (not necessarily a good or realistic representation, not inevitable, kinda just "potential"):

Apparently Vespa mandarinia haven't yet been encountered outside of the general Vancouver area during targeted samples:

I know that you too are fond of wasps/hornets, and are aware of their popular demonization, the way that they're feared, etc. In July 2022, the Entomological Society of America put out an online resource thing that explains why they don't like the name "Asian giant hornet" for Vespa mandarinia and Vespa velutina, instead adopting "northern giant hornet" and "yellow-legged hornet" (which you called the creature, too!) because of the racialized/xenophobic implications. ("Northern Giant Hornet Common Name Toolkit" available at: entsoc.org/publications/common-names/northern-giant-hornet) They say: '"Murder hornet" unnecessarily invokes fear and violence, which impede accurate public understanding of the insect and its biology and behavior. While "Asian" on its own is a neutral descriptor, its association with a pest insect that inspires fear and is targeted for eradication may bolster anti-Asian sentiment in some people - at a time when hate crimes and discrimination against people of Asian descent in the United States are on the rise.'

Which, for me, brings to mind this recent book from Jeannie Shinozuka:

From the publisher's blurb: 'In the late nineteenth century, increasing traffic of transpacific plants, insects, and peoples raised fears of a “biological yellow peril” [...]. Over the next fifty years, these crossings transformed conceptions of race and migration, played a central role in the establishment of the US empire and its government agencies, and shaped the fields of horticulture, invasion biology, entomology, and plant pathology. [...] Shinozuka uncovers the emergence of biological nativism that fueled American imperialism and spurred anti-Asian racism that remains with us today. [...] She shows how the [...] panic about foreign species created a linguistic and conceptual arsenal for anti-immigration movements that flourished in the early twentieth century [...] that defined groups as bio-invasions to be regulated—or annihilated.'

A lot going on at that time with insects, empire, and xenophobia. In the 1890s, the British Empire was desperately searching for a way to halt malaria, and mosquitoes had just been discovered as vectors of malaria. And from Nobel prize podium lectures to popular media newspapers and academic journals, there was all kinds of talk about how "bacteria/viruses/insects are the greatest enemy of the Empire" and whatever. The US was also expanding in the Caribbean, Central America, Pacific islands towards East Asia, etc. Tropical plantations were proliferating, not just in Dutch Java or British India, but also in US administered Central America. And so insects were perceived not just as a threat to the human body of the British soldier or American administrator; insects were also a threat to profits, as insect pests threatened monoculture plantations and agriculture.

That same time period saw the US invasion of the Philippines and exports of products from the islands; the US annexation of Hawai'i, and elevating rivalry with Japan; the 1882 passage of the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act; US control of Cuba and Puerto Rico; expansion of US fruit corporations in Central America and US sugarcane plantations in Cuba/Hawai'i, where insect pests threatened plantation profits; the advent of "Yellow Peril" tropes and fear of invasion in science fiction literature; the detaining of half a million (mostly Chinese) people at the medical quarantine processing center that the US Public Health Service operated at Angel Island in San Francisco; and US insect extermination projects, mosquito control campaigns, and medical policing of local people in Cuba and the Panama Canal Zone (where US authorities detained local people for medical testing).

A lot to consider.

58 notes

·

View notes