#native North American plant species

Text

Bzzz!

Just some bees in my garden and in the fields and on a neighbourhood walk. :)

Featured bees include bumblebees (native), green sweatbees (native), honeybees (invasive), carpenter bees (native), and some I'm not sure about.

Featured flower hosts include bull thistles (invasive weed), rose of sharon (invasive), New England aster (native), cup plant (native), starthistle (not native), Nuttall's sunflower (native), purple coneflower (native), anise hyssop (native), white wood aster (native), swamp milkweed (native), sow thistle (invasive weed), creeping charlie (invasive), creeping thistle (invasive weed), wild rose (native maybe), wild bergamot (native), bride's feathers (native), bigleaf lupin (native maybe or invasive), and upright prairie coneflower "Mexican hat" (native species, but a cultivar).

All my photos, unedited. Don't mind the weirdness of the third last photo. It's my phone's "portrait" which I found out belatedly can have, uh, interesting results.

#bees#bumblebees#insects#hymenoptera#bees wasps and ants#honeybees#sweatbees#carpenter bees#my photos#photography#blackswallowtailbutterfly#bees on flowers#flowers#native North American plant species#native North American insect species#thistles#milkweed#sunflower#purple coneflower#upright prairie coneflower#swamp milkweed#lupin#bigleaf lupin#asters#New England aster#white wood aster#coneflowers#wild rose#starthistle#creeping charlie

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I was taught growing up: Wild edible plants and animals were just so naturally abundant that the indigenous people of my area, namely western Washington state, didn't have to develop agriculture and could just easily forage/hunt for all their needs.

The first pebble in what would become a landslide: Native peoples practiced intentional fire, which kept the trees from growing over the camas praire.

The next: PNW native peoples intentionally planted and cultivated forest gardens, and we can still see the increase in biodiversity where these gardens were today.

The next: We have an oak prairie savanna ecosystem that was intentionally maintained via intentional fire (which they were banned from doing for like, 100 years and we're just now starting to do again), and this ecosystem is disappearing as Douglas firs spread, invasive species take over, and land is turned into European-style agricultural systems.

The Land Slide: Actually, the native peoples had a complex agricultural and food processing system that allowed them to meet all their needs throughout the year, including storing food for the long, wet, dark winter. They collected a wide variety of plant foods (along with the salmon, deer, and other animals they hunted), from seaweeds to roots to berries, and they also managed these food systems via not only burning, but pruning, weeding, planting, digging/tilling, selectively harvesting root crops so that smaller ones were left behind to grow and the biggest were left to reseed, and careful harvesting at particular times for each species that both ensured their perennial (!) crops would continue thriving and that harvest occurred at the best time for the best quality food. American settlers were willfully ignorant of the complex agricultural system, because being thus allowed them to claim the land wasn't being used. Native peoples were actively managing the ecosystem to produce their food, in a sustainable manner that increased biodiversity, thus benefiting not only themselves but other species as well.

So that's cool. If you want to read more, I suggest "Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America" by Nancy J. Turner

35K notes

·

View notes

Text

The knowledge of some common plants

Since many people don't know most of the plants around them, this is information on some plants that are commonly seen in many places throughout the world

This is Lamium purpureum, also called Purple Deadnettle.

It's called deadnettle because it looks like a nettle but it doesn't sting you

This plant is a winter annual—it grows its leaves in the fall, lasts through the winter, and blooms and dies in the spring

Its pollen is reddish orange. If you see bees with their heads stained reddish orange, it is likely because they have visited Purple Deadnettle

This is Trifolium repens, white clover

It is a legume (belongs to the bean family) and fixes nitrogen using symbiosis with bacteria that live in little nodules on its roots, fertilizing the soil

It is a good companion plant for the other members of a lawn or garden since it is tough, adaptable, and improves soil quality. According to my professor it used to be in lawn mixes, until chemical companies wanted to sell a new herbicide that would kill broadleaved plants and spare grass, and it was slandered as a weed :(

It is native only to Europe and Central Asia, but in the lawns they are doing more good than harm most places

Honeybees love to visit clover

Four-leaf clovers are said to be lucky

This is Achillea millefolium, Common Yarrow

It has had a relationship with humans since Neanderthals were around, at least 60,000 years, since Neanderthals have been found buried with Yarrow

Its leaves have been used to stop bleeding throughout history, and its scientific name comes from how Achilles was said to have used Yarrow to stop the blood from the wounds of his soldiers. A leaf rolled into a ball has been used to stop nosebleeds

It is a native species all throughout Eurasia and North America

This is Cichorium intybus, known as Chicory

The leaves look a lot like dandelion leaves, until in mid-spring when it begins growing a woody green stem straight up into the air

Like many other weeds, it has a symbiotic relationship with humans, existing in a mix of domesticated or partially domesticated and wild populations

It is native to Eurasia, but widespread in North America on roadsides and disturbed places, where it descended from cultivated plants

Its root contains large amounts of inulin, which is used as a sweetener and fiber supplement (if you look at the ingredients on the granola bars that have extra fiber, they usually are partly made of chicory root) and has also been used as a coffee substitute

A large variety of bees like to feed upon it

This is Phytolacca americana, known as Pokeweed

It is easily identified by its huge leaves and its waxy, bright magenta stem

It can grow more than nine feet tall from a sprout in a single summer!

If you squish the berries, the juice inside is a shocking magenta that is so bright it almost burns your eyes. For this reason many Native American people used it for pink and purple dye.

It is a heavy metal hyperaccumulator, particularly good for removing cadmium from the soil

All parts of the plant are poisonous and will make you very sick if you eat them, however if the leaves are picked when very young and boiled 3 times, changing out the water each time, they can be eaten, and this is a traditional food in the rural American Southeast, but I don't want to chance it

British people have introduced it as a pretty, exotic ornamental plant. I think that is very funny considering that here it is a weed associated with places where poor people live, but maybe they're right and I need to look closer to see the beauty.

If you see magenta stains in bird poop it is because they ate pokeweed berries- birds can safely eat the berries whereas humans cannot

This is Plantago lanceolata, Ribwort Plantain

It grows in heavily disturbed soils, in fact it is considered an indicator of agricultural activity. It is successful in the poorest, heaviest and most compacted soil.

The leaves, seeds, and flower heads are said to be edible but the leaves are really stringy unless they are very young. Of course, it is important to be careful when eating wild plants, and make sure you have identified the plant correctly and the soil is not contaminated

I have also heard the strings in the leaves can be extracted and used for textile purposes

and that's some common plants you might often see throughout the world

#just remembered i had this in my drafts#i forget why i didn't post it immediately#anyway#plants#the ways of the plants

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

My wisteria is doing the thing!!

#manky ass plastic ‘trellis’ there is only temporary do not perceive it#north American wisteria not a crazy Asian species I’m planting responsibly#mostly native but allowing myself some cheats

1 note

·

View note

Text

We are coming up on courtship and breeding time for the Greater Prairie Chicken, and then includes our Texas Gulf Coast, native sub species, the Attwater's Prairie Chicken, which is endangered.

The males will be establishing their leks soon, in April, where they will be shipping off for the females.

The reason for endangerment is pretty predictable, destruction of habitat, as of course, 99% of North American native prairie has been destroyed. They also are having a hard time recovering because of introduced plants and fire ants.

Have a look at the photos above of males displaying, all three photos by the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Making Better State Insects

So at some point I stumbled across a list of State Insects. Honestly I wasn't even aware states had "state insects", but as I looked down the list my disappointment grew. A vast majority of states had selected the European honeybee (which is not even native) as their state insect, with monarch butterflies and ladybugs being the two runner ups. I thought this was a damn shame because there's so many interesting insects in the US, so I'm making a better official new list of state insects.

For this list my criteria are:

Insect must be native to the state

No repeats

Insect must be easily observable to the naked eye

I also had general guidelines of picking insects that were relatively common (based on inaturalist heat maps of observation) and picking insects that were cool or interesting. Some of these insects I picked because I thought they were important parts of the areas culture and experience (lovebugs, toebiters, and periodical cicadas) and some insects I picked just to raise awareness that they exist in the US.

I also don't think I gave anyone huge L's, no mosquitoes, louses, cockroaches, ect, because my goal of this list is to get people interested in their native insects and I want it to be fun to find and observe your state insect.

Also some states get gold stars for picking state insects that already meet these criteria and are cool so they get to keep theirs. Some states also have "state butterflies" or "state agricultural insect" which for this list I'm ignoring, you can keep those I'm just focused on state insects. Slight disclaimer also, I've only ever lived in California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, and South Carolina, and all these states are keeping their original state insect. So all the insects I'm choosing are for states I haven't lived in. Also I'm not including photos in this post just for my own sanity.

List under the cut!

Alabama

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Giant Leaf-footed Bug (Acanthocephala declivis)

Leaf-footed bugs are cute, they're big, they're stanced up, the males have big back legs, you've probably seen them. Being true bugs they have piercing mouthparts and suck plant juices.

Alaska

Four-spot Skimmer (Libellula quadrimaculata)

Alaska gets to keep their old state insect, it's a cool dragonfly and apparently was partially chosen to honor bush pilots who fly to deliver supplies in the Alaskan wilderness, so really cool!

Arizona

Two-tailed swallowtail butterfly (Papilio multicaudata)

Arizona also gets to keep their state insect. Kind of a shame because Arizona has a lot of cool species, but it did meet my requirements and they get points for choosing a different kind of butterfly.

Arkansas

Old: European honeybee

New: North American Wheel Bug (Arilus cristatus)

One of the largest assassin bugs in the US, these guys are appreciated by gardeners for their environmentally friendly pest control. They also look badass.

California

California Dogface Butterfly (Zerene eurydice)

Endemic to California and on a stamp! Again, kind of a shame because there's a lot of cool insects in California, but I respect this choice, especially since California was the first state to designate a state insect (1929).

Colorado

Colorado Hairstreak Butterfly (Hypaurotis crysalus)

Same deal as California, the state's name is in the common name, unique butterfly found in the four corners region. Just get a stamp or something soon!

Connecticut

Old: European Praying Mantis

New: Cecropia Moth (Hyalophora cecropia)

You picked a state insect no one else had but went with a nonnative mantis? Here's an insect that'll make you stand out and it's a native species. Lesser known than some of the other giant silk moths, the Cecropia moth is the largest native moth and has some truly stunning colors.

Delaware

Old: Convergent Ladybeetle

New: Periodical Cicada (Magicicada septendecim)

Cicada's had to be somewhere on this list and Delaware was one of the main hotspots for brood X, one of the largest broods of the multiple staggered brood cycles. Hey, they have a lot of history in America. Accounts go back as early as 1733, with Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin making a note of them.

District of Columbia

Old: None

New: Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

The Entomological Society of America is trying to get the Monarch Butterfly added as our national insect, so I think that's reason enough to let DOC claim it.

Florida

Zebra Butterfly (Heliconius charithonia)

Florida gets to keep their state butterfly, but the populations that have existed in Florida are in steep decline. Ideally I would want being the official state insect to come with some protections, hopefully people can get invested in reintroducing them.

Georgia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Horned Passalus Beetle (Odontotaenius disjunctus)

Also called bess beetles or patent-leather beetles, these cute guys are important for forest systems because they eat decaying wood, helping to break down felled trees. They're cute beetles that squeak when disturbed.

Hawaii

Kamehameha Butterfly (Vanessa tameamea)

An endemic Hawaiian butterfly named after a ruling dynasty of Hawaii. Their population is under threat, as with a lot of native Hawaiian species, so I think this is a good state insect to build protections and activism around.

Idaho

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Ice Crawler (Grylloblatta sp. "Polaris Peak")

Look Idaho, I have to admit that even though I've traveled extensively through WA, OR, CA, and NV I've never stepped foot in Idaho and I don't intend to. Your state exists in a weird liminal zone, not really the pacific northwest but not really whatever Montana is either. Your state isn't even all in one time zone. So look, I really wanted ice crawlers to be on this list, but they're exclusively found on mountains in the pacific northwest and Sierra Nevadas. Normally I would've given them to Washington or Oregon, but those states already have state insects that work for them. So your state gets ice crawlers, and they do exist in Idaho in the panhandle. It's not an L, ice crawlers are amazing extremophiles that crawl over snow in high elevation mountain peaks. They exist in their own unique order and theres only one genus in the US, with different species being region locked, sometimes onto specific mountains. Their thermoregulation is so delicate, the warmth of someones hand holding them causes them to over heat and die. They're cool, unique, and weird, and let's face it so is your state. At least I didn't take a cop out by picking the potato bug.

Illinois

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Red-banded Leafhopper (Graphocephala coccinea)

Leafhopper done Chicago style.

Indiana

Old: Say's Firefly

New: Common True Katydid (Pterophylla camellifolia)

I wanted to give you Say's Firefly. I really did. But when I looked on Inaturalist not A SINGLE OBSERVATION was listed for the species in Indiana. I'm even going to post pictures.

So even though this is extremely funny I'm giving your state the Common True Katydid instead. Large, loud, and easy to spot, these guys can frequently be heard chirping in trees. Not only do different populations have different rates of chirp, but the rate of chirp is also so predictably dependent on temperature that you could make an equation to tell the temperature based on chirp rate.

Iowa

Old: None

New: Westfall's Snaketail (Ophiogomphus westfalli)

Really cool clubtail dragonfly that's almost exclusively found in Iowa, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Kansas

Old: European Honeybee

New: Rainbow Scarab (Phanaeus vindex)

A kind of true dung beetle, they play an important role in removing waste. And although they don't roll waste like the stereotypical dung beetles, they are extremely pretty.

Kentucky

Viceroy Butterfly (Limenitis archippus)

This is fine.

Louisiana

Old: European Honeybee

New: Lovebug (Plecia nearartica)

Look, one of the southern states was going to get this one and Louisiana has a majority of the observations for them. Although annoying, it's things like having to scrape thousands of flies off your car that makes the Southern experience. Embrace it!

Maine

Old: European Honeybee

New: Brown Wasp Mantidfly (Climaciella brunnea)

I really wanted these guys to be somewhere on the list. Neither a wasp, mantis, or fly, these are predatory neuropterans related to lacewings. They have raptorial front legs (resembling a mantis) and their coloration resembles paper wasps that they live alongside. Weird, unique, and wonderful!

Maryland

Baltimore Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas phaeton)

This butterfly might've been picked for the resemblance of the state flag. It's in decline in it's native range, so hopefully more awareness and consideration to state insects will help push conservation efforts.

Massachusetts

Old: Ladybug

New: Hornet Clearwing Moth (Paranthrene simulans)

Hornet mimic moth, the caterpillars feed on chestnuts and oaks. All lepidopterans (moths and butterflies) have modified hairs on their wings that form the "scales" that give this order their name. For this moth though, parts of it's wings don't have any scales so it more convincingly resembles a hornet. Underneath the scales, butterfly and moth wings look pretty much like any other insect's wing. Cool!

Michigan

Old: None

New: American Salmonfly (Pteronarcys dorsata)

The biggest salmonfly in North America. They make excellent fishing bait, and several fly fisherman use salmonfly lures to catch trout. Their nymphs are also an important indicator of water quality, with them being one of the first species to disappear in the presence of pollution or contaminants.

Minnesota

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: American Giant Water Bug (Lethocerus americanus)

Also one of the ones that had to be on the list somewhere, and the Inat heatmap says Minnesota. Toebiters are part of the experience, and they are cool and ferocious looking.

Mississippi

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Eyed Click Beetle (Alaus oculatus)

Click beetles have a cool adaption that allows them to launch themselves in the air to avoid predators. This makes an audible sound, hence their common name. The Eastern Eyed Click Beetle is one of the largest and most striking click beetles in the US, with large false eyespots on their thorax.

Missouri

Old: European Honeybee

New: Goldenrod Soldier Beetle (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus)

A soldier beetle that feeds on aphids and small plant pests, these beetles also eat pollen and nectar from flowers. They don't harm the flower, and though their common name reflects their preference for goldenrod flowers, they're also an important pollinator of the prairie onion (Allium stellatum). This is a native species of onion that grows from Minnesota to Arkansas.

Montana

Old: Mourning Cloak

New: Western Sheep Moth (Hemileuca eglanterina)

Mourning Cloak butterflies do technically work for my criteria, but I wanted to showcase some more regional insects in this as well, as Mourning Cloaks are found throughout North America and Eurasia. The Western Sheep Moth is an absolutely stunning giant silk moth, found throughout the western United States. Although not as big as some other silk moths, the bold orange and black coloration on these make them absolutely stand out.

Nebraska

Old: European Honeybee

New: Blowout Tiger Beetle (Cicindela lengi)

A tiger beetle with unique patterns, these guys are active predators and are particularly difficult to spot because they run extremely quickly. They seem to be pretty cold tolerant and exist from Colorado up into Canada.

Nevada

Vivid Dancer Damselfly (Argia Vivida)

This damselfly was picked as Nevada's state insect because it's widespread throughout the state and matches the state colors, silver and blue. That gets my seal of approval!

New Hampshire

Two-spotted Lady Beetle (Adalia bipunctata)

This is fine.

New Jersey

Old: European Honeybee

New: Margined Calligrapher (Toxomerus marginatus)

A pretty hoverfly, they strongly resemble bees in both looks and behavior. Larvae feed on common plant pests such as thrips and aphids, while the adults sip nectar and pollinate flowers. These helpful attributes make it something the Garden State can appreciate!

New Mexico

Tarantula Hawk (Pepsis grossa)

New Mexico wins the official state insect list by a landslide. Not only is the tarantula hawk a super cool and formidable insect to showcase, but New Mexico's state butterfly (Sandia Hairstreak) was discovered in New Mexico. No notes 10/10!

New York

Nine-spotted Lady Beetle (Coccinella novemnotata)

A native species of lady beetle that's been in decline in recent years, New York is one of the last remaining states where they've been spotted. I also appreciate that New York designated a specific ladybug species instead of just saying "Coccinellidae species".

North Carolina

Old: European Honeybee

New: Eastern Rhinoceros Beetle (Xyloryctes jamaicensis)

A large native species of rhinoceros beetle. They breed in ash trees, and are under threat due to competition from the Emerald Ash Borer.

North Dakota

Old: None

New: Nuttall's Blister Beetle (Lytta nuttalli)

As with all blister beetles, these guys have a chemical defense. Unlike the more famous Bombardier Beetle thought, instead of being black and red they are iridescent red/purple and green.

Ohio

Old: Ladybug

New: Bald-faced Hornet (Dolichovespula maculata)

Look, when the one thing everyone knows about your state is that it sucks, it's time to lean into it. Bald-faced hornets, everyone knows them, everyone has opinions about them, and they get a lot of attention. I don't think I have to explain this one anymore.

Oklahoma

Old: European Honeybee

New: Giant Walking Stick (Megaphasma denticrus)

The largest insect in the United States. Being a native walking stick, they're less damaging than the imported invasive walking sticks that are heavily controlled.

Oregon

Oregon Swallowtail Butterfly (Papilio oregonius)

Oregon in the common name and in the species name, and also has a stamp!

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania Firefly (Photuris pensylvanica)

Pennsylvania in the common name and species name. If fireflies weren't already on this list I would've made sure to include them somewhere.

Rhode Island

American Burying Beetle (Nicrophorus americanus)

When I saw this on the list I was worried. American Burying Beetles are one of my favorite insects, but they're extremely endangered now. I also thought they existed more in the midwest, so I was worried I would have to change this one because it violated the "native to the region" rule. But! To my pleasant surprise, not only did their historic range extend to Rhode Island, but there is actually a carefully maintained wild population on Block Island. They estimate between 750-1000 individuals live there, making it one of the few remaining places where the American Burying Beetle still exists. Excellent work Rhode Island!

South Carolina

Carolina Mantis (Stagmomantis carolina)

This is fine. I wanted to give South Carolina the Palmetto bug but they're actually not native.

South Dakota

Old: European Honeybee

New: Golden Northern Bumble Bee (Bombus fervidus)

"Save the bees" should really be focused on native pollinators, many of whom are in decline. There are a lot of species of native bee you can feature as a state insect, with the Golden Northern Bumble Bee being a particularly large and striking species.

Tennessee

Old: Firefly and ladybug

New: Black-waved Flannel Moth (Megalopyge crispata)

Seriously look them up, these guys are adorable.

Texas

Old: Monarch Butterfly

New: Rainbow Grasshopper (Dactylotum bicolor)

It was really hard to pick an insect for your state. The Texas Unicorn Mantis was a contender but I eliminated it because it's really only found in the southern part of Texas, so it was between the Rainbow Grasshopper and the Eastern Velvet Ant (or Cow Killer). I went with the Rainbow Grasshopper because it's more wide spread and common, and occurs everywhere except the east part of Texas. But the Eastern Velvet Ant only occurs on the east part of Texas, maybe you should get an East and West Texas insect? I also thought more people have probably already heard of the Eastern Velvet Ant than the Rainbow Grasshopper, which is a shame because they're super interesting to look at.

Utah

Old: European Honeybee

New: Mormon Cricket (Anabrus simplex)

Mormon Crickets are not true crickets, and instead closer related to katydids. Their common name comes from an early account of Latter-day Saint settlers in Utah. In 1848, a swarm of Mormon Crickets decimated the settler's crops, so the legend goes that they prayed for relief from this plague of insects. Later that year, a swarm of gulls appeared and ate the crickets, thus saving the crops. This is recounted in the "miracle of the gulls" story. To recognize their contributions, the California Gull is commemorated as Utah's state bird. I thought it was fitting then that the Mormon Cricket be recognized as your state insect.

Vermont

Old: European Honeybee

New: Long-tailed Giant Ichneumon Wasp (Megarhyssa macrurus)

A pretty wasp with an extremely long ovipositor, these wasps are common in deciduous forests across the eastern United States. They can't sting, and instead use their long ovipositor to stab into tree bark and deposit eggs on the horntail larvae that burrow into the trees.

Virginia

Old: Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Butterfly

New: Giant Stag Beetle (Lucanus elaphus)

A large stag beetle native to the Eastern United States. Although not as well known as their similar looking fellow stag beetles from Japan, these guys are a lovely chocolate brown instead of solid black. Like most stag beetles, they breed in decaying wood.

Washington

Green Darner Dragonfly (Anax junius)

I imagine this was chosen because it matches the flag.

West Virginia

Old: European Honeybee

New: Appalachian Tiger Beetle (Cicindela ancocisconensis)

This tiger beetle likes hilly terrain. As with all tiger beetles, they can be hard to spot because they run across the ground in search of prey. They are fast! But this can make it more rewarding when you finally catch up to one.

Wisconsin

Old: European Honeybee

New: Phantom Crane Fly (Bittacomorpha clavipes)

Don't believe old wive's tales about crane flies drinking gallons of blood, they are nonbiting. Those striking black and white legs are hollow, and are held out when they fly, making an extremely distinct sight that's been likened to sparklers or snowflakes.

Wyoming

Sheridan's Hairstreak (Callophrys sheridanii)

This is fine.

#insect#insects#state insect#long post#list#text post#entomology#bugblr#invertebrates#invertiblr#inverts#invert

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Larix laricina, commonly known as tamarack, hackmatack, and Eastern, red, black or American larch.

L. laricina is native to boreal and eastern temperate North America (Nature Serve), persisting right up to the northern treeline. It frequently grows in or at the edges of wetlands (swamps, fens, marshes, and riparian areas), but can tolerate a wide range of substrates and moisture. For a good overview of the species, check out this link.

It's one of those plants that can be a lightbulb moment for some people, inspiring them to reconsider basic assumptions about the way we divide up the natural world. When we learn about trees, many of us learn that there's two basic "types": deciduous trees and conifer trees. We are often told that deciduous trees are broad leaved and lose their leaves in the fall and that trees with needles don't.

Tamarack 'breaks' that; it is a deciduous conifer. Rightly, the language we are taught should be that there are deciduous and evergreen trees, that there are conifers and broad-leaf trees, and these categories can mix and match. (Of course, the trees haven't read the rules, so I wouldn't be the least bit surprised to find out there is a broadleaf coniferous gymnosperm--exceptions ARE the rule in ecology!)

#i could go on about this tree but i think the post would get too long#theyre a very cool boreal species!!!#tamarack#larix laricina#plants#ecology#nature#I think it's fitting for the first day's plant to be the one in my profile pic!

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

Salix discolor (American pussy willow)

The catkins of this pussy willow (Salix discolor) is another sure sign of early spring and they're the only flower I can think of that wears a fur coat. Pussy willows use these silky fibers as insulation to keep their catkins protected in late winter. This species is native to North America in a wide band that runs, coast-to-coast, through southern Canada and the northern lower United States.

Plants know when to flower by measuring the air temperature and the length of day. A brief warm period in the winter will not be enough for pussy willows- they need longer days too. Then, when the timing is perfect - boom they bloom!

As with so many spring flowering trees, willows produce flowers before they leaf-out. Male and female catkins grow on different plants. The appearance of yellow anthers indicates that this one is a boy and it's just about to start producing pollen. Willows are insect-pollinated and this means that hungry worker bees will soon wake up and these pussy willows will immediately get their full attention.

#flowers#photographers on tumblr#pussy willows#spring flowers#catkins#fleurs#flores#fiori#blumen#bloemen#Native plants#my garden#recommendation: "What a plant knows” by Daniel Chamovitz#Vancouver

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did you know North America has a native lotus? Nelumbo lutea or yellow lotus is one of only two wild lotus species left on the planet. This prehistoric giant produces the largest flower in North America - the size of your head! The leaves average two feet across. It grows from the Great Lakes down to Central America and the Caribbean. It is edible, medicinal, mildly poisonous, and mildly psychoactive. Many Native American tribes believed it had mystical powers.

More info:

• Native American Ethnobotany Database

• Plants for a Future Database

• Wikipedia

Photo from Wikimedia Commons

#bane folk#lotus#yellow lotus#american lotus#nelumbo lutea#nelumbonaceae#sacred lotus#ancient plants#prehistoric plants#north america#ethnobotany#poisonous plants#medicinal plants#edible plants#psychoactive plants

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bison are often associated with North America, but the wisent (Bison bonasus) is native to Europe. It was driven to extinction in the wild in the early 20th century (it had been extirpated from western Europe for several centuries), but reintroduction efforts began a few decades later.

As with American bison (Bison bison), the wisent is an important keystone species, and its reintroduction stands to benefit the ecosystems it is returning to. As browsers, wisent help keep plant growth in check, and their manure is valuable both for the plant community as well as detritivores and decomposers like various insects, fungi, and microbes. Native large carnivores are generally as scarce as the bison, but in places where wolves and other predators still exist, the bison could be important sources of food.

The hard truth about restoration ecology is that we will never be able to get ecosystems back to how they were before humans so heavily altered them. We can't even necessarily return them to when our impact was much lighter, given all the changes we have made. But if we can at least create pockets of biodiversity with safe travel corridors between them, that will go a long way in at least keeping native wildlife from disappearing entirely. The reintroduction of the wisent in Europe, and the bison in North America, represent important steps in undoing at least a little of the damage done.

#wisent#bison#bovidae#European bison#endangered species#extinction#ecology#restoration ecology#habitat restoration#keystone species#mammals#nature#wildlife#animals#environment#conservation#science#scicomm#rewilding

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 2nd, 2024

Thick-legged Hoverfly (Syritta pipiens)

Distribution: Native to Europe, but found throughout Eurasia and North America.

Habitat: Occur wherever there are flowers, but most common around human habitations; common habitats include farmland, gardens and parks. Larvae are most common in rotting organic matter such as compost, manure, silage, and occasionally cadavers.

Diet: Larvae feed on decaying organic matter, while adults feed on many types of flowers. Their most common food plants are water-willow, white vervain, American pokeweed and candyleaf.

Description: The thick-legged hoverfly is called so due to their overdeveloped hind legs. These insects can sometimes be pests, as they occasionally feed on ornamentals, but are generally considered beneficial because they pollinate many common flower species. They also act as bio-indicators, especially to demonstrate the effects of environmental changes on pollinators.

Hoverflies are very agile fliers, and are often found hovering near flowers. This species, however, is very rarely found flying more than a metre above ground level. When they encounter another fly, males will sometimes circle around them; if they're male, this often results in the two males circling eachother, and if they're female, the male may dive at her at an acceleration of up to 500 centimetres per second squared in an attempt to initiate copulation.

Images by Joaquim Alves Gaspar and Stephen Luk.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Succulents Part 7--Opuntia humifusa

Succulents are a wide variety of plants, spanning multiple orders. Some have succulent leaves while others have succulent stems. Cactuses are succulents, but not all succulents are cactuses. Defining what exactly makes a succulent is a little tricky. For example, cabbage leaves are considered by some to be succulent, but tulip and onion leaves apparently aren't.

All photos mine. Unedited.

This is a single species post as it's the only opuntia I have photos on hand of (single specimen, rather, as this is all the same plant). Anyway, it's a succulent by virtue of being a cactus. I'm not even sure you really differentiate leaf from stem on a cactus. This cactus I've grown for several years now, and last summer was her first flowering season! I hope she does it again this year too. This species of cactus can be grown outdoors in Ontario and the rest of its native range since it is hardy to cold weather. :)

#succulent plants#succulents#flowers#my photos#photography#blackswallowtailbutterfly#yellow flowers#Opuntia humifusa#devil's tongue#garden flowers#cactus#cactus flowers#Opuntia#my garden#prickly pear#eastern prickly pear#native North American plant species

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cool Plant: Arundinaria gigantea

Giant River Cane

This plant is extra special! Not only is it one of three members of the genus Arundinaria, which together are North America's only native bamboo, it also once formed extensive bamboo forests in the American Southeast known as canebrakes, where the bamboo stalks could exceed 30 feet tall! The bamboo forests are thought to have covered 10 million acres of the southeastern United States.

River cane grows in damp areas such as low-lying woods and the edges of creeks, and has incredible abilities for resisting erosion and filtering contaminants from groundwater. It is a fire dependent species, and canebrakes were maintained by Native Americans using controlled burns. Native American peoples such as the Cherokee and the Choctaw used the river cane as a super tough all purpose crafting material for everything from flutes and blowguns to baskets, backpacks, mats and bed frames.

Nowadays, it mostly only exists in small patches along fences and in ditches, where it usually grows no taller than 10 feet or so. Since it grows in large clonal colonies and only produces seeds once before the entire patch dies, it is hard for it to reproduce these days. The destruction of the canebrakes by colonists' cattle, plowing, and neglect of the caretaking practices are thought to have helped drive the Carolina parakeet and passenger pigeon to extinction.

Many other species depend on the Arundinaria bamboos to live: there are at least 9 butterfly and moth species that use it as a host plant, and some of the rarest plants in the Southeast, including the Venus flytrap, are often found in remaining fragments of canebrakes.

202 notes

·

View notes

Text

listen one of the major reasons i care so much about Arundinaria is that she's gotta be legit the most exciting rising star in the evolutionary world.

Flowering plants emerge like 100mil years ago, proceed to become the baddest bitches on planet earth with hundreds of thousands of species found in every environment.

from this lineage emerges the GRASS which, using the simple technologies of "Grow leafs from the bottom so the tops can get eaten and you can just keep a-goin'" and "Not die when stepped on" become the undisputed masters of the sunny and arid regions

From the lineage of the GRASSES. Emerges a grass that decides to step up its game and invent WOOD to become some sort of fucked up tree. This grass is known as WOODY BAMBOO and it kicks everybody's ass.

The woody bamboo is mostly thriving in Asia, but around 2mil years ago, a bamboo got LOST AS FUCK and accidentally went to NORTH AMERICA. It turns out the south-eastern part of North America is a downright luxurious climate for a bamboo and so the bamboo actually evolved into its own genus.

However, there was an ICE AGE that froze a bunch of North America and the bamboo was forced to a tiny edge of the Gulf Coast. Fortunately, the bamboo made a mutualistic symbiosis with HUMANS, which used controlled burning to create its ideal habitats in exchange for using the stems for a super-strong, versatile, flexible, water resistant material for literally everything. So basically it spread all throughout the Southeast of North America and formed its own habitat type, a bamboo forest environment known as a CANEBRAKE.

It's native North American bamboo, y'all. It's been reduced to 2% of its former extent and a lot of people don't even know it exists.

This plant is going places we can't let this shining streak of weird-ass plants with ideas just strange enough to work collapse because of a freak colonialism incident

Arundinaria gigantea my absolute beloved

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey I thought you might appreciate a heads up that the yellow-legged hornet (Vespa velutina) has been spotted in Savannah, Georgia. 😞

Nice. Well, not nice news. But glad that you thought of me. Thank you.

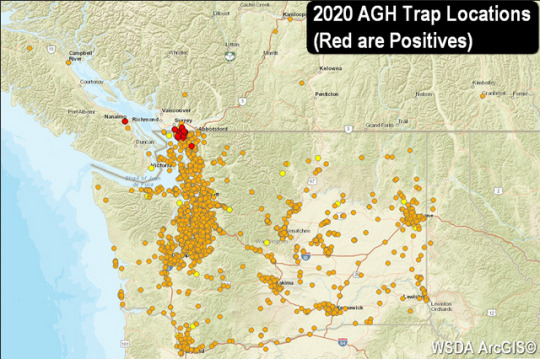

(For other people who have yet to fully embrace and explore their innate love of hornets, this Vespa velutina hornet is originally from Southeast Asia. This creature is closely related to Vespa mandarinia, the creature derisively referred to in the US as "murder hornet" or "Asian giant hornet", originally from South/East Asia, which is now apparently established near in the Salish Sea region near Bellingham, Vancouver, and Nanaimo.)

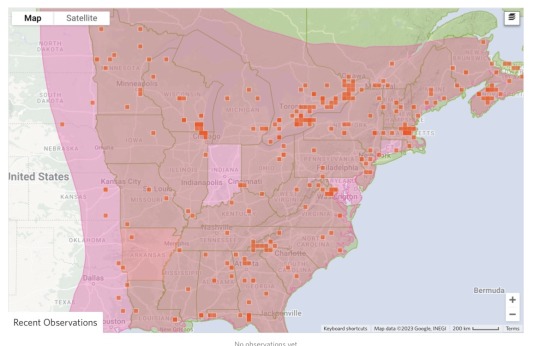

Here's a look at where the giant hornets now live in North America, along with the distribution of some other large hornets which might be mistaken as Vespa manadrinia/velutina:

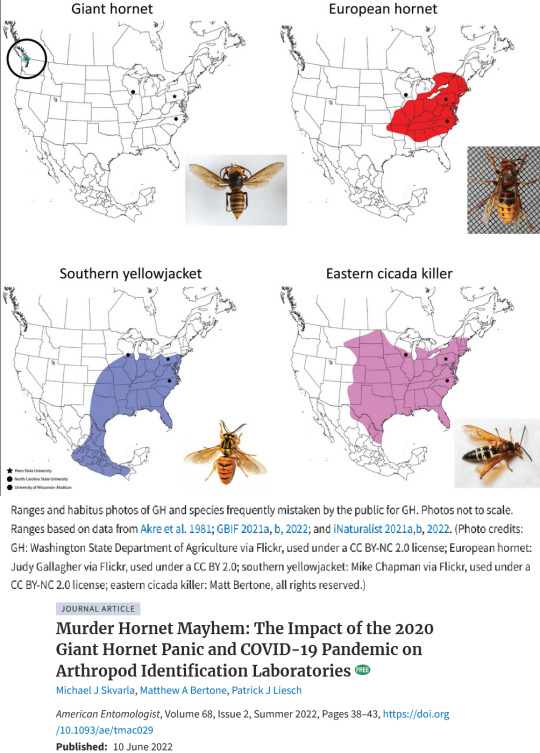

The map was originally published in 2022 in American Entomologist, displaying distribution range of (non-native) giant hornet; (non-native) European hornet; (native) southern yellowjacket; and (native) eastern cicada killer. The article also identifies a few few other species which might be mistaken for "murder hornets": great golden digger wasp, bald-faced hornet, German yellowjacket, red-legged cannibal fly, and pigeon horntail. (Available to read for free online; article title in the source/caption beneath the map.)

I've had many memorable encounters with large (native) bald-faced hornets in dense cedar-hemlock rainforest-y places. And coincidentally, the Pacific Northwest is also now apparently the North American home/homebase of Vespa mandarinia. So here are some other PNW wasps/hornets in comparison, from Oregon State University Extension Catalog (2022):

From 2020 research on potential dispersal of Vespa mandarinia over a couple of decades (not necessarily a good or realistic representation, not inevitable, kinda just "potential"):

Apparently Vespa mandarinia haven't yet been encountered outside of the general Vancouver area during targeted samples:

I know that you too are fond of wasps/hornets, and are aware of their popular demonization, the way that they're feared, etc. In July 2022, the Entomological Society of America put out an online resource thing that explains why they don't like the name "Asian giant hornet" for Vespa mandarinia and Vespa velutina, instead adopting "northern giant hornet" and "yellow-legged hornet" (which you called the creature, too!) because of the racialized/xenophobic implications. ("Northern Giant Hornet Common Name Toolkit" available at: entsoc.org/publications/common-names/northern-giant-hornet) They say: '"Murder hornet" unnecessarily invokes fear and violence, which impede accurate public understanding of the insect and its biology and behavior. While "Asian" on its own is a neutral descriptor, its association with a pest insect that inspires fear and is targeted for eradication may bolster anti-Asian sentiment in some people - at a time when hate crimes and discrimination against people of Asian descent in the United States are on the rise.'

Which, for me, brings to mind this recent book from Jeannie Shinozuka:

From the publisher's blurb: 'In the late nineteenth century, increasing traffic of transpacific plants, insects, and peoples raised fears of a “biological yellow peril” [...]. Over the next fifty years, these crossings transformed conceptions of race and migration, played a central role in the establishment of the US empire and its government agencies, and shaped the fields of horticulture, invasion biology, entomology, and plant pathology. [...] Shinozuka uncovers the emergence of biological nativism that fueled American imperialism and spurred anti-Asian racism that remains with us today. [...] She shows how the [...] panic about foreign species created a linguistic and conceptual arsenal for anti-immigration movements that flourished in the early twentieth century [...] that defined groups as bio-invasions to be regulated—or annihilated.'

A lot going on at that time with insects, empire, and xenophobia. In the 1890s, the British Empire was desperately searching for a way to halt malaria, and mosquitoes had just been discovered as vectors of malaria. And from Nobel prize podium lectures to popular media newspapers and academic journals, there was all kinds of talk about how "bacteria/viruses/insects are the greatest enemy of the Empire" and whatever. The US was also expanding in the Caribbean, Central America, Pacific islands towards East Asia, etc. Tropical plantations were proliferating, not just in Dutch Java or British India, but also in US administered Central America. And so insects were perceived not just as a threat to the human body of the British soldier or American administrator; insects were also a threat to profits, as insect pests threatened monoculture plantations and agriculture.

That same time period saw the US invasion of the Philippines and exports of products from the islands; the US annexation of Hawai'i, and elevating rivalry with Japan; the 1882 passage of the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act; US control of Cuba and Puerto Rico; expansion of US fruit corporations in Central America and US sugarcane plantations in Cuba/Hawai'i, where insect pests threatened plantation profits; the advent of "Yellow Peril" tropes and fear of invasion in science fiction literature; the detaining of half a million (mostly Chinese) people at the medical quarantine processing center that the US Public Health Service operated at Angel Island in San Francisco; and US insect extermination projects, mosquito control campaigns, and medical policing of local people in Cuba and the Panama Canal Zone (where US authorities detained local people for medical testing).

A lot to consider.

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thinking about ghouls as farmers/farmhands

I imagine that some types of kagune would be excellent for harvesting/ploughing with a nice bonus of no carbon emissions. I imagine ghouls, after criminalisation, would possibly even revolutionise farming/carbon footprint from farming?

(Although of course ideally a farm wouldnt till but even then for harvesting ghouls would be quite efficient.)

GHOULS IN FARMING AND FOOD PRODUCTION IS SO INTERESTING

Ghouls have always been a part of society, and regardless of where they are or how accepted they are, they’ve always had some hand in farming since, especially before industrialization, it was a good field for them. Their strength, senses, and kagune make them fantastic at cultivating, protecting, and harvesting food

In old world cultures where ghouls were always ostracized, they couldn’t be open about why their crops grew so well, so they tended to make up myths and stories about some ritual or another that makes their harvests so bountiful. They had senses of smell and pressure detection that could help them sniff out blights and pests, as well as semi-accurately predict rainfall, letting them handle issues before they got too bad. That, and their strength that lets them handle the physical task of planting and harvesting, helped them produce a lot of plants. But telling humans how they did it is off the table, so it was common for them to have a plowing Ox just for show and to say they said some prayer that helped

A lot of why ghouls thrived in farming is due to their regeneration. It may not be talked about much anymore, but it is DANGEROUS. Not just the modern machinery, but the strain of lifting and carrying. The illnesses carried by plants and animals. The workhorses and oxen that can just fucking kick you to death. The PIGS. It’s all risky work, and back before antibiotics, just one cut and you’re done for. A person who can not only survive almost any cut, but take a donkey kick to the face and get right back up to finish plowing the field is one of the most valuable people any farming village can have

Farming animals is more hit or Miss, because a lot of prey animals panic when they smell ghoul. Some ghouls still kept them and after enough time, or enough animals born around the smell of them, they could get used to it. Historically ghouls have run a lot of butcher shops because it was one of the best places to hide human meat before dna testing became widely available, so some animal husbandry skill was a good thing

Ghouls tended to make good shepherds. In especially rural areas, a lot of humans would collectively decide not to talk about the fact that someone is obviously a monster because they’re simply so fast and strong and don’t let sheep and cattle go missing or get hunted. If you were in Cold Ass Nowhere Ireland in 1635 and you had a shepherd who not only never loses a sheep but also eats the English, you’d pretend you didn’t notice either

In areas and cultures where ghouls were more accepted, they were essential to hunting and farming. North and central american ghouls had traits designed for taking down megafauna to supplement their diets, and their human companions could depend on them to bring countless Buffalo and deer home. Jungle subspecies had traits built for climbing, and were central to the harvest of high growing fruits and beans. A now likely extinct species native to Canada had semi aquatic adaptations and a thick layer of fat who were designed to hunt seals and small whales, and shaped the way any community lucky enough to have some survived. In places where ghouls were welcomed, they were so efficient at harvesting and hunting that land rarely needed to be developed for monocultures at all

When ghouls are decriminalized in more parts of the world, their physical abilities are allowed to shine again. Stories of ghoul farmers through history arise. Plenty of American and Polynesian communities (who had been telling people about ghoul’s contributions to their land and cultures for years and were having that brushed off as myth) can legally reintroduce the old practices of ghoul hunting and harvesting techniques. Smaller farms hire more ghouls once it’s clear that they can do machine level work without the expense of maintaining machines, and it’s one of the biggest ghoul hiring fields at the start of their legalization

Naturally, ghoul farming unions are quick to form. They can do machine level work, but are not going to risk being treated like machines for it. As with any Union there’s some backlash, but when it becomes apparent just how much better ghouls are at crop maintenance and harvesting, demands are met. It’s become a well paying profession, and has been good work for ghouls that struggle with the human grade education they were denied when they were younger, or ghouls who simply prefer to work outside doing something that benefits people

35 notes

·

View notes