#celtic lore

Text

The Celtic Goddess Danu - the Mother Goddess, the goddess of and manifest divine waters. The waters that fell from heaven to create the sacred river, Danuvis or the Danube.

The Tuatha De Danaan are translated as "The Children of Danu."

There are similarities here between this Ganga and the forming of the Ganges. But more notably, Danu from Hindiusm - the primordial mother goddess of ancient/first old waters - liquid. There is also a river named Danu in Nepal.

She is the mother of the Danavas, a larger category of the Asuras - celestial/supernatural beings of god like powers, but calling them gods exactly is incorrect. Asuras and Devas are larger in some ways than that - celestial/cosmic beings of princely domains/abilities is slightly more accurate, but for all intents an purposes. There are more similarities between Celtic and Vedic/Hindu culture/myths.

Why?

Well, recent research has shown Celtic genetics shows paternal and maternal ancestry from ancient India (R-M269 deriving via R1b, and H & U haplogroups) - is it really that weird then we see echoes of the ancient Indian epics echoed throughout other parts of the world, especially with the history of Eurasian/South Asian trade, migration, and more?

There is a story well known in the South Asian stories, but let's talk about the similar Celtic one. A tale of how a hero has to build a causeway across the waters to reach his foe, and how his wife must outsmart her captor/villain.

Some Indians are already nodding their heads. We begin with the Celtic hero: Fionn mac Cumhaill, a hero who is born just after his father dies.

Does this sound somewhat familiar?

Well, here we have Rama, born to Dasaratha, who is cursed to die soon as his son leaves him. His father dies as soon as Rama is exiled from Ayodhya.

Finn goes on to study with poets, warriors, and hunters in the forest of Sliabdh Bladma.

Rama goes to the forest hermitage where he learns similar arts under Vasitha.

Finn later in his youth goes on to destroy the fire breathing demon Áillen of the Tuatha (Children of Danu analogous of Aditi here btw) who destroys the capital of Tara every year on Samhain (a celebration very similar to the Indian Pitru Paksha btw)

Rama as a teen kills the Asuras attacking the hermitage - the enemies of the Devas (children of Aditi), interestingly enough just like I've talked about in the Norse (how you have two bodies of celestial/god beings - Aesir and Vanir), the Greeks have it, there is also a flipping that happens in a lot of these ancient cultures.

Aesir and Asura come from the proto indo European asr - but in one group one is good, the other bad. However in the Iranian - Zoroastrian, there is a reverse. The Ahura (Asura) are GOOD and the Devas are bad (down to including Indra from South Asian mythology), and in the Celtic we see something similar - a flipping of roles.

Rama, Sita, and her protector Lakshmana were all in exile together in the forest. The demon king Ravana sends a golden deer to tempt/seduce and lure away Sita from Rama but it is really the demon Maricha in disguise. Sita is tricked and ends up sending her protector to Rama, leaving herself vulnerable, and thus abducted by Ravana who wishes to marry her and this leads to a war in where Rama eventually gets her back also, kidnapping of a women sparking a war? OH HI, HELEN OF TROY. HI.

Fionn meets his wife Sabadh while hunting, and guess what? She is turned into a deer by a druid she refuses to marry. She returns to her true form once in Fionn's home and they marry...only she's turned into a deer again by the druid Fear Doirich when Fionn was off at war, and Fionn must spend years searching for her. Wow. Coinky dinky dinky.

Now to the original part of my talk here, the causeway in Ireland was built by Fionn to travel to battle a giant. Rama Setu, his causeway, was built by Rama's army so he could enter Lanka to do battle there - (Sri Lanka).

The Celts also have four major cycles of time just like the Vedic Indians did. The tricky thing here is that linguistically, PIE (proto Indo European) has been shown to be behind a lot of story/cultural influences as it spread through Europe/Asia, but...the thing that's hard to account for here is how geo-located Ramayama is in/to India, so why do specific echoes of it show up in Celtic mythology so much so?

Yay comparative mythology and echoed storytelling/beats tropes across the world.

#celtic folklore#celtic lore#celtic stories#Tuatha De Danaan#Ganga#Danu#the ganges#Asuras#Celts#fionn mac cumhaill#south asian mythos#south asian#myths and legends#hindu mythology#hindu gods#hinduism#india#Áillen of the Tuatha#Ireland#irish folklore#irish mythology#celtic mythology#gods and goddesses#gods and monsters#god stories#storytelling#folklore#folktales

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reblogged by Shane Lehane Sheelah take a bow: St Patrick’s wife? Probably not – she was far more important than that

A symbol of Irish womanhood, she deserves to be celebrated again every March 18th

The 16th, 17th (St Patrick’s Day) and 18th March: Erskine Nicol’s painting of the Irish celebration that included Sheelah’s Day. Photograph courtesy of the National Gallery of Ireland

Shane Lehane

Fri Mar 15 2019 - 06:00

For hundreds of years Ireland has had an icon of womanhood and a compelling symbol of all things female, yet few people know her name. The forgotten goddess is none other than Sheelah, once widely celebrated on March 18th, both in Ireland and among the diaspora, yet now all but disappeared. Fáilte Ireland should start to champion her alongside St Patrick: she could be worth a fortune.

Two years ago my research into this disregarded deity resulted in somewhat misleading headlines that said Sheelah was St Patrick's wife. That was not the case, but at least it brought Sheelah and her festival back to our attention. I believe Sheelah – or Sheila, Sheela, Shela, Sheelagh or Síle, depending on the source – has far more to her than the once widely held belief that she was our national saint's other half.

Sheelah's Day fell each year on March 18th, and the usual dispensation to disregard Lenten abstinence on March 17th and wet the shamrock – drink alcohol, in other words – in honour of St Patrick was extended to the following day as well, in honour of his so-called wife. The Freeman's Journal of March 20th, 1841, reported that a woman who appeared in court for drunkenness declared she bought "two small naggin of whiskey… not wishing to break through the old custom of taking a drop on St Sheelah's Day". In contrition to the judge, she vowed: "I here promise that for Patrick's Day or Sheelah's Day, or any other day in the calendar, I'll never stand in your presence again."

Some say Sheelah was 'Patrick's wife', others that she was 'Patrick's mother', while all agree that her 'immortal memory' is to be maintained by potations of whiskey

A painting by Erskine Nicol from 1856, depicting the revelries of such mid-Lenten festivities, is accurately entitled The 16th, 17th (St Patrick’s Day) and 18th March. This elongated name recognises that most Irish festivals, including fairs, pattern days and wakes, took place over three days: the gathering, the feast and the scattering. Sheelah’s Day was the last (but not the least) of the traditional three days of celebration that began on the eve of St Patrick’s Day.

William Hone gives a detailed account of Sheelah’s Day celebrations in Britain in The Every-day Book, from 1827.

“The day after St Patrick’s Day is ‘Sheelah’s day’, or the festival in honour of Sheelah. Its observers are not so anxious to determine who ‘Sheelah’ was, as they are earnest in her celebration. Some say she was ‘Patrick’s wife’, others that she was ‘Patrick’s mother’ while all agree that her ‘immortal memory’ is to be maintained by potations of whiskey. The shamrock worn on St Patrick’s day should be worn also on Sheelah’s day, and on the latter night, be drowned in the last glass. Yet it frequently happens that the shamrock is flooded in the last glass of St Patrick’s day, and another last glass or two or more on the same night, deluges the over-soddened trefoil. This is not ‘quite correct’ but it is endeavoured to be remedied the next morning by the display of fresh shamrock, which is steeped at night in honour of ‘Sheelah’ with equal devotedness.”

This festive time coincides with the vernal equinox, one of the two midpoints of the sun’s annual cycle, in the season of new fertility, when days are poised to outlast nights for the first time since the autumn equinox, the previous September. An emphasis on new life and procreation is manifest in a host of mythological incarnations and folk reflexes at this time of the year. The goddess and holy woman Brigid is celebrated on February 1st; the analogous figure of Gobnait, goddess of fertility and beekeeping, is commemorated on February 11th. These women usher in the new cycle of fertility with ploughing, sowing, the birth of animals, the rising of the sap and the reawakening of nature.

This time of year in the past brought an equal emphasis on human marriage and reproduction, with Shrove Tuesday, immediately before Lent, long being the most popular day in Ireland to be married.

The three-day carnival celebrating Patrick and Sheelah occurs at this key point in the calendar and in the annual cycle of fertility. That Sheelah is firmly situated around the equinox, the seminal pivot of fertility, indicates that she had distinct fertility associations and can be viewed as an equivalent to Brigid and Gobnait.

Patrick is fighting with his wife, now a miserable hag at war with the world. She spitefully brushes the last of the winter snow into the way of the new cycle of work

Sheelah still echoes through Newfoundland, otherwise known as Talamh an Éisc, or Land of the Fish, the most Irish place outside Ireland. An amazing legend on this Canadian island, which many still believe to be true, centres on Sheila na Geira, or Síle Ní Ghadhra, a young Irish princess from Connacht. Sometime in the 1600s, when she was en route to a French convent to finish her education under the care of her abbess aunt, pirates commandeered her ship. One of them, Gilbert Pike, from a well-to-do English family, fell in love with her. They married aboard and then settled down in Mosquito, in southwestern Newfoundland. Here, in time, Sheila na Geira gave birth to a child – according to tradition the first white European child to be born in Newfoundland – so it is said that many there owe their lineage to her. It is also said that every Irishman who visited and settled on Newfoundland paid obeisance to Sheila na Geira, who reportedly lived to 105.

In Ireland, especially from the mid-18th century onwards, Síle Ní Ghadhra was one of the most popular representations of the country, and in the aisling, or dream, poetry of the period she epitomises Ireland in its idyllic state: strongly independent, bountiful and fertile. In this sense Sheila joins the many women sovereignty figures who represent Ireland: Ériu, Fódla, Banba, Aoibheall, Clíodhna, Macha, Mór and Mórrígan, to name a few (and not forgetting the Christianised figures of Brigid and Gobnait).

In keeping with her mother-goddess attributes, the last big snowstorm after St Patrick’s Day is still called Sheila’s brush in Newfoundland. The idea is that Patrick is fighting with his wife, now a miserable hag at war with the world. (The idea that Patrick had a wife called Sheila must have arrived with the Irish of the 18th and 19th centuries.) She spitefully brushes the last of the winter snow into the way of the new cycle of work.

It’s significant that Síle na géag, or Sheila of the brush, is one way to render Sheela-na-gig, the name for the naked old woman who appears, exposing her genitals, in medieval stone carvings. We’ll return to this. As for the Newfoundland Sheila’s brush, sealing fleets would refuse to go back out on the ice until this storm had passed; fishermen continue to do so.

Sheila’s brush: Newfoundland fishermen would wait for the first snowstorm after St Patrick’s Day to pass before going back out to sea. Photograph: NFB/Getty

Sheelah is an enigmatic name. It and all its variant spellings appear only about 500 times in the 1911 census of Ireland. By contrast its English equivalent, Julia, has almost 30,000 entries. Similarly, no Sheilas appeared on the manifests for ships taking women convicts to Australia, even though the name has entered the language there as jocular but mildly pejorative slang for a woman or girlfriend.

That Freeman’s Journal court report from 1841 refers to the defendant as “a half-naked, wretched looking old woman” who was “charged with having been found drunk and incapable in the street”. The headline was “A Sheelah’s Forethought”. This and many other references made “Sheelah” a byword for a bedraggled old woman.

But elderly women also had experience of the world and were custodians of inherited knowledge, playing significant roles in rites of passage in the human life cycle and the cycle of the year. They acted as midwives, corpse washers and professional mourners; they advised on herbalism and vernacular medicine; and they were central to events such as the pattern day. In this respect Sheelah, as the old woman, is strongly resonant of the important Irish folk figure known as the Cailleach.

The Cailleach – the old, wise healer – is a multifaceted personification of the female cosmic agency. Irish mythological, historical and folkloric expressions cast her as the expression of the territorial- and tribal-sovereignty queen and as the life force inherent in nature, nurturing and maternal but also terrifying and destructive.

Sheela-na-gig: the medieval stone carvings show folk deities associated with birth and death. Photograph: Getty

The Cailleach tradition’s deep roots in ideas of birth, fertility and death brings us back to the Sheela-na-gig. Ireland has more than 100 examples of these often-misunderstood medieval stone carvings. The women in them, who are reclining or squatting, often have big ears, long hair, gritted teeth, emaciated ribs and prominent breasts.

They often appear on medieval tower houses, medieval church sites and holy wells. I recently came across one on a round tower in Rattoo, in Co Kerry. For a long time they were seen as representations of the evils of lust or as ways of averting the “evil eye”. But Sheela-na-gigs are more convincing, in line with the Cailleach, as folk deities associated with birth and death. And so Sheelah embodies the cycle of fertility that overarches natural, agricultural and human procreation and death.

That Sheelah was thought of as St Patrick’s wife is a significant folk reflex. The cult of Patrick is firmly based on the pre-Christian deity Lug, or Lugh – as in Lughnasa or Lúnasa, the harvest festival – who represents the male side of the life-giving equation. Lug personifies the ideal man, exemplified in the complex ideology of Irish kingship. It is the union of male and female that allows us to exist.

It should be no surprise, then, that the three-day carnival to celebrate St Patrick, a major Christian icon, at the liminal point of the season of fertility, when human procreation is paramount, should include Sheelah, his consort.

As many of her devotees died in the Famine, and given the influence of the misogynist, patriarchal church, she has all but vanished from Irish life. I, for one, will be raising a glass to her on her feast day.

Shane Lehane teaches archaeology, folklore and history at CSN College of Further Education, in Cork, and lectures in the department of folklore and ethnology at University College Cork. He is always interested to hear about local folk custom and tradition; you can email him at [email protected]

I hope you enjoyed this Reblog more to come soon

Regards,

Culture Calypso’s Blog

#sheelah#Ireland#irish literature#irish history#my blogs#spirituality#holydays#saint patricks day#celtic lore#SoundCloud

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Ghostly Encounter/ Character: Morrigan Cabbott

#a ghostly encounter#morrigan cabbott#the morrigan#celtic lore#celtic fiction#fiction series#fiction writing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Fantasy Readers Should Dive into Historical Fiction: 5 Must-Read Novels

As a fantasy reader, you might be drawn to the novels of J.R.R. Tolkien, George R.R. Martin, and other masters of the genre.

You revel in the magical realms, mythical creatures, and epic battles that define the world of fantasy literature.

But have you ever considered exploring the equally enthralling world of historical fiction?

Historical fiction novels share many of the same qualities that…

View On WordPress

#9th-10th-century Britain#ancient Celtic world#Bernard Cornwell&039;s Saxon Stories#Celtic lore#Fantasy Readers#George R.R. Martin#gripping storylines#Hilary Mantel&039;s Wolf Hall#historical fiction#intellectual thriller#intricate world-building#J.R.R. Tolkien#Manda Scott&039;s Boudica series#medieval monastery#Merry Men#must-read novels#Outlaw series#rich characterization#Robin Hood#The Last Kingdom series#Thomas Cromwell trilogy#Tudor England#Umberto Eco&039;s The Name of the Rose#Viking Age#world of fantasy literature

0 notes

Text

youtube

#nature#storied#thai lore#folklore#bhuddist lore#jatakas#nariphon tree#dryads#greek lore#animism#crann bethadh#trees of life#celtic lore#cosmic trees#baobab trees#yoruba lore#african tree of life#ceiba trees#yggdrasil#norse lore#wishing trees#kalpavriksha#indian lore#jain lore#hindu lore#sikh lore#jubokko#japanese lore#trees#celtic tree of life

0 notes

Text

sundown at solstice (2223BCE)

merry midwinter folks!!

#winter solstice#oc art#stonehenge#folk art#the chief#chief’s life and lore#digital illustration#artists on tumblr#original comic#the lonely barrow#celtic folklore#bronze age#early bronze age#late Neolithic#happy solstice

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the reasons i object to the random assignation of words like "mythology" and "folklore" to some medieval literature (and by random i mean interchangeably and with no real consideration of what they mean) is that when you look at what gets called mythology and what gets acknowledged as literature, it's very othering, it's very noticeable that english and french material generally gets to be literature* and lit in celtic languages is folklore, and it often obscures the actual historical context of that material. in particular it obscures the literate, learned institutions that produced that literature whether courtly or ecclesiastical in favour of attributing it to some nebulous voice of the people that ignores the complex web of influences and powers that shaped those stories

if chaucer isn't folklore then a fourteenth century irish text isn't either. if shakespeare isn't folklore then a sixteenth century irish text isn't either. etc etc. the anonymity of the author does not make it any less a self consciously literary production within a learned environment with influences from classical and contemporary literature written to support political aims or to respond to contemporary events

folklore exists, and is not these texts (it does a disservice to folklore and folklorists to assume you can approach them in the same way methodologically tbh!). mythology exists, and is a difficult-to-discern thread that runs through some of these texts (i find the dindsenchas elements particularly convincing as mythological, but otherwise it's hard to identify what's what, particularly when authors are making classical allusions all the time). but what the majority of these texts are, at face value, is literature. the way that they get othered and made out to be somehow more primitive and magical just bc they're in celtic languages and (usually) anonymous really pisses me off

*arthurian material is the exception but this usually relies on some vague notion of celtic origins so it's actually the same phenomenon wearing a different hat

#oh yeah this is definitely discourse sorry#reblogs OFF replies ready to be shot on sight#there are uses of terms like myth that are more grounded and sound than these uses#they're not the ones i'm talking about#i'm talking about the arbitrary description of any and all irish literature as 'celtic mythology' and/or folklore#and like. not to vagueblog ao3 but. also ao3's garbage tag wrangling contributes to this#i will continue to stubbornly tag my shit as medieval Irish lit#it is not ancient religion and lore. it's a fucking fifteenth century text my dude

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

for anyone interested in arthurian folklore and/or mythology around the world: an efficient source

recently i found this website and it has been incredibly helpful with research for my projects (and just research for interest's sake). for arthurian folklore, especially, there are not only many different versions of each story, but many different pronunciations for each name, many different names for each character - you get the idea. in my opinion, this website displays a good variety of each legend while still getting the point across rather simply.

here it is: Nightbringer

i'm going to be reblogging some other good websites/pages for folklore; view my blog page for the other ones :) also, if my fellow writers/nerds/autistic people out there want to add to this thread, i will appreciate and explore every single one of your suggestions

#lore#greek mythology#irish mythology#arthurian legend#arthurian mythology#arthurian literature#sources#history#folklore#celtic folklore#world mythology#merlin rewrite#writers on tumblr#fanfic writer#writerscommunity#writers and poets#ao3 writer#writer things#writeblr#creative writing#writing community

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Real Mother of the Gods

Random internet articles will tell you how Danu is the mother of the Irish gods, like some overarching ancestral figure.

When reading the actual lore, this idea is pretty false. There may be a Danand, mother to three gods, but no great Danu. This is even argued, as a better translation may reveal they are three gods of skill, the word for skill confused or made into the name of a goddess.

While I was reading the verse portion of the Lebor Gabála Érenn volume 4 (LGE) on the tuatha, I discovered something interesting. Ethniu is named as mother to seven of the major gods: Luichtaine, Creidne, Goibnu, Dian Cecht, Nuada, Dagda, and Lugh.

Additionally, in the Cath Maige Tuired, if I am not mistaken, Ogma is named as one of her sons.

It is a shame this isn't discussed more. The prose text of the LGE does not mention this either. It mostly recounts who is the father to whom.

Ethniu is daughter of Balor, a Fomorian king. The Fomorians share ancestors with the gods, and live on islands close to Ireland.

Folk or fairy tales tell how Balor heard a prophecy that his grandson would kill him, so he locked Ethniu up, surrounded only by women, until a man looking for a magic cow Balor stole sneaks in and she gets pregnant with Lugh.

In the LGE it is mentioned she is given to Cian, a god, in marriage and they have Lugh.

But turning to the verse texts in the LGE, here is the small passage:

"They were powerful against their firm conflict,

The seven lofty great sons of Ethliu.

Dagda, Dian Cecht, Credne the wright,

Luichne the carpenter, who was an enduring.

consummate plunderer,

Nuada who was the silver-handed,

Lug Mac Cein, Goibninn the smith."

(The names have variations of how they're spelled in the LGE.)

Her first six sons are over different skills/roles, a smith, wright, carpenter, a physician, a king, and a druid/wizard/warrior, but her son Lugh possess all of the skills and becomes the king of the gods after Nuada’s death.

I think Ethniu/Ethliu should get the credit for being mother of the gods.

#irish mythology#tuatha de danann#irish myth#pagan#irish lore#celtic myth#goddess#irish gods#witchblr

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had the realization the other day that the brooch Godrick wears is the spitting image of the Tara Brooch, which “would have been commissioned to be worn as a fastener for the cloak of a high ranking cleric or as ceremonial insignia of high office for a High King of Ireland in Irish Early Medieval society” (x).

Since Limgrave and Stormveil seem very inspired by Ireland and Celtic art—more than Leyndell, where Godrick presumably came from—my guess is that Godrick found the brooch in Stormveil as a relic of the Storm Lord and decided to wear it because it’s gold and pretty (which might be supported by the fact he’s wearing it on the wrong shoulder, according to the wikipedia article.) [edit: it might be the correct shoulder for him after all due to the side his “main” arm is on!]

#the screenshot of godrick’s brooch was taken from a post full of screenshots of godrick’s model by feathery-dickmuffins!#had to redo this whole ass post because my attempt to add a readmore deleted half the writing Twice#i hate you tumblr#anyway if anyone has any thoughts about this feel free to add! i’m not an expert on celtic art or anything#and i haven’t done much research on the storm lord yet#elden ring#godrick the grafted#godrick the golden#elden ring theory#elden ring headcanons#elden ring lore#godrick

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

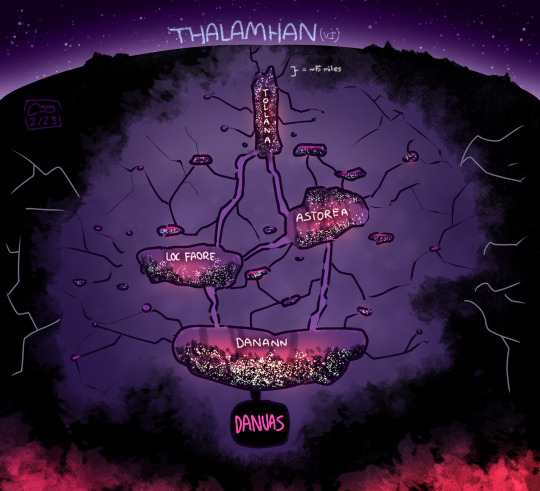

Here's the current draft for Thalamhan's map, including the names of all four cities and Danuas's location! Things are most likely going to change in the future but for now, this is the layout. It's not entirely accurate, for one the scale is probably bound to change and the map presents the colony as very vertical when it's not. I'd probably need to make it in a 3D software for it to be the most accurate it can be, but that can be for another time

When Danuas tunneled into the planet millions of years ago, the series of interconnecting cave systems she left behind would become Thalamhan. Early Thalamites would found Danann, the capital city, and during the Branching Era centuries later, they would expand upward toward the surface, founding the other three cities as well as many smaller towns and villages. Thalamites also live along the tunnels connecting each settlement to another.

Danann is the capital and cultural center of the colony, home to the Sacred Grounds. Beneath it is Danuas, accessed only by the cityspeaker through an entrance known as the Well of the Titan.

Loc Faore is the agricultural capital, a city built around a large lake of the same name. The settlements that surround it are along the streams that come from the lake, home to most of Thalamhan’s farmers.

Astorea is known for its high population of smiths and metallurgists. Its nickname is Little Danann, as it has the second largest cultural scene in the colony, particularly textiles and art.

Tollana is unique for being a mostly vertical city, so most of its population are Thalamites with flight based alternate modes. Many scientists and engineers including some from Danann have residences here, as it is the closest city to the surface, perfect for researching the planet and sky themselves.

The dark regions that surround the colony are the Darklands.

#for some fun facts:#the capital danann is directly lifted from Tuatha De Danann which are in some regards the predecessors to the fae folk#It sounds like Danu which is the name inspiration for Danuas#Astorea is named after a place in gw2 where fae inspired plant folk live - thalamhan takes a bit of inspiration from them as well#(you'll def see the insp later when i talk about how thalamites are forged XD)#Loc Faore is a spin off 'Loch' and 'Faoi' which are 'Lake' and 'Under' in irish respectively#and Tollana is off of tollán which is 'tunnel' in irish#at least i hope all of this is right. im trusting my translator here#i am not irish but hopefully I'm doing as well enough research as I hope I am XD I love me some celtic lore!!#anyway#a lot of the big and important thalamite names such as the cities and titan have irish insp#thalamhan#worldbuilding#cjj arts#transformers fan colony#maccadam#transformers

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Ghostly Guidance / Character: Adam Cleary, Dagda

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish Faery Story Book "Where the Faeries Dwell"

Hi all!

I am so incredibly proud of my mother who has published her very first book, "Where the Faeries Dwell".

She really put her heart and soul into creating a beautiful book of short stories based on the tales her Grandmother told her as a child about the interactions between humans and the Sidhe, the Faery folk of Irish mythology. These stories used to be passed down in the oral tradition by people gathering around the fireside, eagerly awaiting to hear stories of the Seanachai that would leave them spellbound and feeling a greater connection to their heritage. Even through all the turbulent times Ireland went through, these stories survived. If you or your family also enjoyed hearing fairy tales while growing up, this is a wonderful book to read.

She has set herself up online for people wanting to buy the book! I will link the two websites on my page if you are interested in checking it out and if you have any questions, feel free to drop me a message and I’ll be happy to help :)

Go raibh mile maith agat <3

#irish mythology#celtic mythology#ireland#fairy story#faerytale#faery lore#faery tradition#sidhe#daoine sidhe#irish lore#celtic#seanachai#fae#irish author#author post

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cursed Rulers: Parallels Between Auberon & Emhyr

“Emperors rule their empires, but two things they cannot rule: their hearts and their time. Those two things belong to the empire.”

“The end justifies the means.”

Leaders of the highest order for their people, both rulers pursue the greater good at the expense of decency and their own humanity. A greater good to be achieved through similar means – by begetting the child who is prophesised.

Etymology

Let’s start with names for the names we give our characters often betray the backdrop from which we drew in conceiving them; especially if the author is a self-confessed fan of the subject matter.

Nilfgaard’s Emperor’s real name originates in the history of the British Isles and in the Arthurian legendarium. In Welsh, Emyr denotes “ruler” or “king.” Emreis, meanwhile, qualifies as the Welsh counterpart to the Greek Ambrose, serving as the equivalent for the Romanized Ambrosius. Ambrosius Aurelianus, a semi-mythical figure thought to have lived around the time Romans had recently left the Isles for good, was a Romano-British warlord credited with turning the tide against the invading Angles and Saxons. Very little about Sub-Roman Britain is verifiably beyond doubt, which means the era lends itself richly to myth craft (for which reason historians search within this period for the historical Arthur). Most chroniclers and myth-makers way back when were monks. Gildas mentions Ambrosius Aurelianus first in De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae. A Roman by blood, methods and upbringing, Ambrosius is thought to have claimed the position of a High King after the Bryton Vortigern and to have ushered in over a century of peace by pushing out the Germanic tribes and defeating them at Mons Badonicus (Mount Badon). Bede describes Ambrosius as “a modest man of Roman origin, who was the sole survivor of the catastrophe in which his noble parents had perished”. From Nennius onward though, the myth grows and factual matter starts to ebb.

Geoffrey of Monmouth links Ambrosius with the wizard Merlin, Uther Pendragon (whom he makes Ambrosius’ brother) and Constantine III (allegedly Ambrosius’ father). Co-incidentally, Emreis or Emrys is also the birth-name of Merlin (Latinized from the Welsh Myrddin, the great bard). But for the sake of comparing to Emhyr var Emreis as known in the Witcher, making Constantine III the father of Ambrosius is especially noteworthy. A Roman general come to power during the Roman Britain revolt, Constantine headed out to Gaul with all the mobile troops left in Britain in 407, leaving the island vulnerable to the migration of Germanic tribes. The general ended up declaring himself the Western Roman Emperor; a position he held for two years beside the sitting emperor Honorius. Then he was put to death by another general (who, surprise-surprise, also went on to declare himself). Geoffery of Monmouth changes his Constantine III’s background a little from the historical one, but importantly for us makes it so Constantine’s sons – Ambrosius and Uther – are smuggled to Brittany after their father’s death. There the exiles are gathering strength in order to later return and challenge the usurper Vortigern. These plot beats are familiar to what we know of Emhyr var Emreis.

In Welsh, Emrys also means “immortal” but Emhyr var Emreis – despite having lived several lives – is still a mortal ruler. Auberon Muircetach on the other hand exudes eternity. So old as to appear near immortal to Emhyr’s daughter, the Alder King retains a youthful appearance despite the thousand yard stare in which is buried unimaginable sadness. In his folk origins, Auberon is leading several lives.

Bearing Hen Ichaer (ichor (Ancient Greek), blood of the gods), Auberon (Old French) appears first in the 13th century Les Prouesses et faitz du noble Huon de Bordeaux and gives Shakespeare his fairy king Oberon who rules the spirit world. In turn, the name in Old French originates in the Germanic Alberich (or Elberich), denoting “the ruler of supernatural beings.” The most well-known Alberich is probably Wagner’s, from De Ring des Nibelungen, and though called a dwarf he treads closer to Svartálfar (dark elves) in character; dwarves and elves being, on occasion, conflated in Continental Europe. An important nuance though is that Alberich much like Auberon is the keeper of his subjects’ magical treasure (Rheingold/Andvaranaut Ring, or Elder Blood respectively), which is the source of power and wealth of each one’s race. Circling back to the suitability of Shakespeare’s adoption of the name for his fairy king, the root “alb” in Alberich originally stands for “white” and forms the trunk of Albion – denoting the British Isles with its white cliff face.

The character of Auberon Muircetach (as of the other Alder elves) is linked to Goethe’s Erlkönig; a haunting force of corruption and death, a stealer of souls who covets youthful innocence. This stands in contrast to Johann Gottfried von Herder’s translation of the Danish folk ballad Elverkongen’s Datter (The Elf-King’s Daughter) which inspired Goethe but where the protagonist is a wilful, selfish female spirit. Androgyny though is not new to elves. Erlkönig translates into English variously as Erlking, the Elf-King, and the Alder King. Erle (or Elle in Old Danish) stands for “alder” in German, and Ellefolk is a folkish use of “elves” in Denmark. Calling the Otherworld elves in the Witcher Aen Elle – the Alder Folk – is thus hardly wilful. But what do elves and alder trees have in common? As elven culture and origin story in the Witcher draws heavily on the Celtic world, an amusing example emerges on the plains of Albion. During the mythical Cad Goddeu – Battle of the Trees – the alder trees are animated by Gwydion and march in the vanguard while Bran the Blessed (a Welsh God-king figure) boasts alder twigs as personal protection and heraldry. Alder is the warrior of trees; the bark bleeds when cut, changing from white to red. Alder is also linked to the realm of water and wetlands – predominant on the plains of Somerset surrounding the Glastonbury Tor (a well-known place of power and an entry to Caer Sidi and the Otherworld). Bran is wounded by a poisoned spear in the course of Cad Goddeu and so he is sometimes deemed one of the first prototypes for the Fisher King, an Arthurian figure Sapkowski’s Auberon (and elves) amounts to in lieu of symbolic fit – an ailing ruler, rendered impotent with an injury which dooms the realm. In this manner links between the Continental Erlking and Celtic mythos shape up.

Finally, Muircetach – an alteration of the Irish Muirchetach also stands for “mariner.” Befitting of an Elf-King who has traversed the seas of time and space.

Intent

In the Witcher, both Auberon and Emhyr are embroiled in a plot of siring the child of prophecy with Cirilla Fiona Elen Riannon – their blood relative. Genetically, the incest is a matter of degree: Emhyr is Ciri’s biological father, Auberon Ciri’s ancestor 8 generations past. Symbolically, however, the degree collapses with Auberon because a few human generations are meaningless to elves. They call Ciri Lara’s daughter, effectively deeming Ciri Auberon’s granddaughter. But the reader – not unlike Ciri herself – won’t know about this until the very end of the tale.

Notionally, both rulers bind their actions with Ithlinne’s prophecy. The problem with prophecies is they decouple arguments from verification, lending themselves to the rationalization of all and any action. At least insofar as knowing the future accurately is impossible. This is the case for humanity, it is not the case for elves. Elven prophecies were made by the elves and for the elves in the first place. Consequently, the degree to which each ruler knows the prophecy to be true and believes in it differs. For Emhyr, mystical secret knowledge of the universe is irrelevant in comparison to political expedience: reason of state is what the tomorrow will bring. The Nilfgaardian Emperor is neither a mystic nor a fatalist. Contrary to the Alder King – a Sage, a ruler, and an elder – who has witnessed and likely verified some of what the Seers have prophesised. Elves conceive of the nature of time as cyclical in which the fate of things is tied up in the endless repetition of endings giving birth to new beginnings, the dance of attraction between life and death, two sides of the same coin which form the singular eternal truth of existence – change is only an eternal reoccurrence and re-arrangement of all. Auberon, you see, is a bit of a mystic. And even without Seers privy to secret knowledge, an extraordinary life span reduces the elves’ proclivity to black swan fallacy, or at least pushes the error probabilities. But at the end of the day, mysticism takes the cake.

The idea that either ruler must be the progenitor, however, comes at the instigation of an outside force.

Shortly after Ciri’s birth Emhyr is visited by a sorcerer. Emhyr has a strong aversion to mages; he was cursed by one. Even so, Vilgefortz proves himself capable of helping him regain the Nilfgaardian throne and is straightforward about what he wishes in exchange – gratitude, favours, privileges, power. Vilgefortz tells Emhyr about Ithlinne’s prophecy – a version about the fate of the world; a human interpretation. Then he plants the seed as to what Emhyr should do to steer the fate of this world. Naturally, he has his own agenda. It is not a huge leap of imagination to conceive of Auberon having been similarly persuaded by Avallac’h (an elven Knowing One who thematically parallels the human Vilgefortz). Not only are Avallac’h and Auberon tied by broken familial bonds, they are each a participant of the Elder Blood programme; and each, a Sage. Avallac’h serves nearly as a double for Auberon, his own fate also tied with Ciri’s. And Auberon is a “willing unwilling” in his arrangement with Ciri; implied so in his rage when he reveals Ciri ought to be grateful to him for lowering himself to the endeavour at all. There is an alternative.

Neither the Emperor nor the Alder King is pursuing the incestuous course of action out of lust. But both have the option to waive being the sire. Ithlinne’s prophecy is not explicit about the father of the Swallow’s child. For elves the match is backed by science. For humanity – pragmatism.

Emhyr has ordered to wipe out the Usurper’s name from the annals of history and is cementing his earthly power, conquering and ensuring the succession laws play out in his favour. Not only is he legitimatizing his rule over Cintra – the gateway to the North – by marrying its last monarch’s granddaughter, by keeping it in the family, he is also consolidating his rule among the Nilfgaardian aristocracy. The Emperor’s concern lies with the dynastic struggle for power: it is his blood that should rule the world and because history is bending its arc according to Nilfgaard’s dictation that means surmounting the Nilfgaardian succession laws. From such perspective, not fathering Ciri’s child would create numerous problems. Ciri as Emhyr’s heir would remain behind any other male offspring he might have (with any Nilfgaardian aristocrat). Ciri might not be acknowledged as a legitimate successor in Nilfgaard in the first place as she is a foreigner, born in Cintra at a time when her father was not yet an emperor; a bastard, effectively, and a girl besides. Ciri’s husband, moreover, may have designs on power himself and his remaining under Emhyr’s control, or Ciri’s control, is not a guarantee. It is difficult to be the correctly-shaped chess piece in a game of interests of the state. That a widely recited prophecy about the fate of the world can lend an aura of destiny to the brutal political machinations undertaken to seek retribution and pursue earthly power is convenient; a descendant who will be the ruler of the world – a bonus. But to get there sacrifices must be made.

‘Cirilla,’ continued the emperor, ‘will be happy, like most of the queens I was talking about. It will come with time. Cirilla will transfer the love that I do not demand at all onto the son I will beget with her. An archduke, and later an emperor. An emperor who will beget a son. A son, who will be the ruler of the world and will save the world from destruction. Thus speaks the prophecy whose exact contents only I know.’

’What I am doing, I am doing for posterity. To save the world.’

- Lady of the Lake

Notably, the manner in which the Emperor claims to understand Ithlinne’s prophecy does not make guarantees that a father’s incest with his daughter will ensure his progeny will one day save the world. The saviour is a few generations away and the causal arrow between now and then is not direct: the son could die, could father a child with a genetically non-fitting partner, could be sterile, or could turn out to be a daughter altogether. Not to even begin with what the world needs saving from in the first place; again, elven prophecies were written by the elves and for the elves. Emhyr var Emreis is neither an elf, a geneticist, an idealist nor a mystic. He is an autocrat.

Elder Blood is the creation of elves and it is elves who understand how their genetic abilities play into handling what was foretold by Ithlinne. Emhyr’s daughter, the Lady of Time and Space, is the descendant of an Alder King who has utilized Hen Ichaer in the past and whose ambitions lie in an altogether different ball park than that of an Emperor of one single world. Appropriately to the Saga’s love for subversion, it is ironic that human understanding of elven prophecies remains on the level of poetry, while elves – the irritatingly poetic, mystical species – can read the science elevating the prophetic jargon into something more. Which regardless does not invalidate the problem with prophecies: they lend themselves to the rationalization of action, frequently covering up the real horses the powerful might have in the race. Legitimatization of the ruler’s right to remain the leader of their people is relevant in Auberon’s life too. More on that when we return to the Fisher King parable and the nature of curses upon the two rulers.

Role & Relationships

Let’s take a look at the characters’ personalities.

Appearance: a play of contrasts

A very tall, slender elf with long fingers and ashen hair shot with snow-white streaks. An elf with the most extraordinary eyes – as on all Elder Blood carriers – reminiscent of molten lead. A man with black, shiny, wavy hair bordering an angular, masculine face that is dominated by a prominent nose (hooked, presumably, or Roman if you like). The Emperor of Nilfgaard does not resemble an androgynous elf by any means. But this does not mean nothing remains in him of the elven gene pool. Not only does Emhyr’s etymological origin link with the Romano-Celtic world underpinning all things elven in the Witcher. Nilfgaardians are effectively the Romano-Brytons. The human population in the South of the Continent mixed with elves heavily, retaining a lot of elven law, customs, language, and DNA. As Avallac’h says about heritability, “the father matters,” and Emhyr was one half of the equation for getting Ciri.

Rex Regum - King of Kings

The readers are probably more familiar with the imperial system and how that features in the depiction of Nilfgaard. Auberon Muircetach’s position as the Supreme Leader of the Aen Elle – as opposed to merely a “king” – is instead much more reminiscent of the station of a High King.

Ancient and early kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland boast many High Kings (e.g. Ard Rí Érenn Brian Boru, Ard Rí Alban Macbeth, Vortigern, King of the Britons, etc). The High King was usually elected and set above lesser rulers and warlords as an overlord in a land that shared a high degree of cultural unity. Emperors usually ruled over culturally different lands (regularly obtained through recent or ongoing conquests). In character such high kingship was sacred: the duties of the ruler were largely ceremonial and somewhat restricted, unless war, natural disaster or any other realm-wide occasion created a need for a unified command structure. The Irish High King, for example, was quite straightforwardly a ruler who laid claim to all of the land of the Emerald Isle. Noteworthy, because the ruler is frequently seen as the embodiment of the land, associated with the health and well-being of the realm that the land sustains. In quasi-religious terms, High Kings gained their power through a marriage to, or sexual relationship with, a sovereignty goddess; frequently, a mother goddess who was associated with the life-giving land. As one of the most frequently studied elements of the Celtic cosmology, this feature is instantly recognisable in the outlook of the elves in the Witcher and factors heavily into Auberon’s relationship with Ciri. Ciri who is the avatar of the Triple Goddess – the Virgin, the Pregnant Mother, and the Old Woman Death. As Sapkowski notes in Swiat króla Artura. Maladie:

“…no Wiccan mystery in honour of the Great Triple, cannot be performed, [without] the goblet and the sword.

Grail and Excalibur. The rest is silence.”

Through the Triple Goddess’ interaction with her God-counterpart (a ruler who briefly assumes the role of the god) is showcased the eternal cycle of life – one which cannot be realised without the interaction of the cup (feminine) & the sword (male). Excalibur is the symbol of rightful sovereignty and its wielders are frequently powerful men, but Ciri is a woman and a woman is the Grail, bringing salvation and new life. To possess the Grail is to legitimize oneself as the ruler, as the leader, protector, and father figure of the realm. Thus a King of Kings must do exactly that. A protector, a father figure, and a druid (wise man) merge into a symbolic whole in the Supreme Leader of the elves.

(But Ciri is also the witcher girl and owns a sword, unyielding before the matter of her gender. And though many a men might take her for the Lady of the Lake, she is not about to part with her sword.)

The realm is all

From early age, Emhyr’s father instilled an understanding in his heir that nothing counts more than the interest of the state. The blood of the Emreis family must be on the throne. Fergus never abdicated, not after torture, not even after his son was turned into a mutant hedgehog in front of his eyes. Love for his child did not sway Fergus from having his son suffer in the interests of power and the realm. This is how the shard of ice in Emhyr’s heart forms. Auberon, equally, “thinks of England” when attempting to regain his daughter’s legacy and restore their people’s power. The circumstances of Lara’s demise, however, beg the question about the Alder King’s role in facilitating or enabling the conditions that let things spiral out of control and break beyond repair. The stakes were infinitely higher for Auberon than they are for Emreis’ dynastic struggle. But what would an answer to this question change? In their cold hearts these characters see themselves each as duty-bound.

Ambitious and gloried, they nevertheless occupy different stages in their lives.

Emhyr’s ambition burns bright and fresh. Auberon’s has dwindled into a shadow of the past; buried under having witnessed and lived through the sacrifices that a ruler makes in the name of power. Emhyr chooses to seek retribution and power beyond what would befall him should he accept his life as Duny (the cursed, pitiful Duny), the prince consort of Cintra. Never losing sight of his goal, love and human happiness become temporary phases and means to an end, and Emhyr returns to Cintra only in the form of flames and death to pursue his daughter in insane ambition. The White Flame retains an active disposition; a lust for life. Neither Emhyr nor Auberon gallop at the head of their armies though, leading instead from the rear. They have lackeys for carrying out their will remotely (e.g. Cahir and Eredin). Emhyr, however, is said to be otherwise highly involved in the ruling of his empire, even if many revolutionaries who had helped him on the throne had hoped he would remain but a banner of the revolution. In contrast, the Alder King has more or less withdrawn from life and active service. In presence of Avallac’h and Eredin, Auberon appears much more like the standard Emhyr had refused to become. Of course, many decisions the equivalent of which Auberon has already made are still ahead of Emhyr, including as concerns the freedom of his daughter.

A ruler’s heart

Did Emhyr believe that he would be able to see Pavetta in Ciri and thus push through with the incest? Did Auberon hope to glance the memory of his wife in the eyes of Lara’s “daughter” and manage in this way? As already noted, neither ruler is pursuing their plans out of lust, but as lust must be induced for the act to bear fruit I cannot help but wonder what these characters must do to themselves to follow through with their plans. Because the love that is called for between a woman and a man in order for new life and hope to be born is in this instance abnormal. Yet it is undoubtedly love that plays a huge role in determining both Emhyr’s and Auberon’s eventual fate.

Until the emergence of false-Ciri, Emhyr var Emreis is said to have had numerous ladies in the imperial court. Little is known about Auberon’s disposition, but by the time Ciri starts frequenting his bed chamber it has become evident the image of a dowager king fits the elf like a glove; disaffected with romantic dalliance, he is still aware of the courtly intrigue and expectations surrounding it.

The next evening, for the first time, the Alder King betrayed his impatience.

She found him hunched over the table where a looking glass framed in amber was lying. White powder had been sprinkled on it.

It’s beginning, she thought.

…

At one moment Ciri was certain it was about to happen. But it didn’t. At least not all the way.

And once again he became impatient. He stood up and threw a sable fur over his shoulders. He stood like that, turned away, staring at the window and the moon.

- Lady of the Lake

Emhyr’s marriage to Pavetta, Ciri’s mother, was an unhappy one. In his own words, he did not love “the melancholy wench with her permanently lowered eyes,” and eventually would have had the vigilant Pavetta killed. Inadvertently, Emhyr caused Pavetta’s death anyway.

‘I wonder how a man feels after murdering his wife,’ the Witcher said coldly.

‘Lousy,’ replied Emhyr without delay. ‘I felt and I feel lousy and bloody shabby. Even the fact that I never loved her doesn’t change that. The end justifies the means, yet I sincerely do regret her death. I didn’t want it or plan it. Pavetta died by accident.’

‘You’re lying,’ Geralt said dryly, ‘and that doesn’t befit an emperor. Pavetta could not live. She had unmasked you. And would never have let you do what you wanted to do to Ciri.’

‘She would have lived,’ Emhyr retorted. ‘Somewhere … far away. There are enough castles … Darn Rowan, for instance. I couldn’t have killed her.’

‘Even for an end that was justified by the means?’

‘One can always find a less drastic means.’ The emperor wiped his face. ‘There are always plenty of them.’

‘Not always,’ said the Witcher, looking him in the eyes. Emhyr avoided his gaze.

‘That’s exactly what I thought,’ Geralt said, nodding.

- Lady of the Lake

After Pavetta’s demise Emhyr hounds his own daughter to the ends of the earth, killing her grandmother, burning down her home, and driving Ciri into an exile from which she never fully recovers. An exile which kills the innocence in her; the snow-white streaks in Ciri’s hair are from the trauma. In contrast, Auberon does not seem to even know what became of Shiadhal – his partner and the mother of their daughter together. On the verge of death he confuses Ciri for Shiadhal and says, “I am glad you are here. You know, they told me you had died.” The Alder King recalls Shiadhal affectionately, in the same loving breath as he recalls their daughter Lara. Lara whose exile – voluntary or not – killed her.

When Ciri was six years old, Emhyr took a lock of hair from her and held onto it; out of sentiment and for his court sorcerers to use. One of Auberon’s last lines to Ciri involves tying a loose ribbon back into Lara’s hair.

In regard to their brides-to-be, both rulers are saddled with fakes. A fake Ciri-Pavetta and a fake Shiadhal-Lara. But Emhyr’s and Auberon’s attitude toward the fake is diametrically opposite. Emhyr sees false-Cirilla as “a diamond in the rough.” Auberon calls Ciri “a pearl in pig shit, a diamond on the finger of a rotting corpse.” For Emhyr, a diamond is the essence of his poor peasant girl. While a pearl in pig shit, for Auberon, remains the essence of Ciri. Neither ruler can entirely ignore the social vigilance extended toward the ruler’s bedchamber either. The idea of a “foreign bride” is frowned upon among the Nilfgaardian aristocracy; it decreases their ability to influence the Emperor. Ciri’s social status at Tir ná Lia is never explicitly addressed, but the presence of human servants – all of whom that the reader sees are female – and casual xenophobia from Auberon himself does not make it hard to venture a guess.

‘If I were … the real Cirilla … the emperor would look more favourably on me. But I’m only a counterfeit. A poor imitation. A double, not worthy of anything. Nothing …’

- False-Cirilla

Lady of the Lake

‘It’s all my fault,’ she mumbled. ‘That scar blights me, I know. I know what you see when you look at me. There’s not much elf left in me. A gold nugget in a pile of compost—’

- Ciri

Lady of the Lake

The Alder King is unable to bring himself to love Ciri. The Emperor relents, caring for his daughter at last as a father should at the very end, in the one moment where it matters. Moreover, Emhyr ends up eventually marrying his own reason of state and comes to love the false-Cirilla. The contrasts do not end here. Real Ciri threatens to tear Emhyr’s throat out for what he is planning to do to her (unknowing that he is her father), yet with Auberon Ciri turns submissive and grows attached. She weeps over Auberon’s corpse and vows vengeance on Eredin for killing the Alder King. Ironic as Auberon never intended to let Ciri go, while Emhyr does let his daughter walk free. The shard in Auberon’s heart never melts. It shifts in Emhyr’s.

In their last meeting with the girl, both rulers implicitly reveal their blood relation to Ciri.

Cursed Rulers of the World

Emhyr’s tale begins and is framed with a curse. Likewise Auberon’s. And for both it is love in its different manifestations that will shift the curse just enough to offer closure. For healing largely entails obtaining closure.

‘They were silent for a long time. The scent of spring suddenly made them feel light-headed. Both of them.

‘In spite of appearances,’ Emhyr finally said dully, ‘being empress is not an easy job. I don’t know if I’ll be able to love you.’

She nodded to show she also knew. He saw a tear on her cheek. Just like in Stygga Castle, he felt the tiny shard of cold glass lodged in his heart shift.’

- Lady of the Lake

The reference to H. C. Andersen’s fairy tale of the Snow Queen is self-evident. Emhyr var Emreis is an Emperor whose heart has been pierced by a shard of ice. In the Saga the legend is elven and refers to the Winter Queen who conducts a Wild Hunt as she travels the land, casting hard, sharp, tiny shards of ice around her. Whose eye or heart is pierced by one of them is lost; they will abandon everything and will set off after the Queen, the one who wounded them so gravely as to become the sole aim and end of their life.

There are two ways in which to interpret the way Sapkowski applies the legend of the Snow Queen in the Saga. First, as a complement to the author’s stance that in life - where most things are shit - the Holy Grail is a woman, because it is the love of a woman and the hope a woman instils that often makes men act in inconceivable ways; love is the great motivator and the great balancer of scales. Almost as powerful as death. Or more so?

‘I would not like to put forward the theory that hunting for the wild pig was the primordial example of the search for the Grail. I don't want to be so trivial. I will - after Parnicki and Dante - identify the Grail with the real goal of the great effort of mythical heroes. I prefer to identify the Grail with Olwen, from under whose feet, as she walked, white clovers grew. I prefer to identify the Grail with Lydia, who was loved by Parry. I like New York in June… How about you?

Because I think the Grail is a woman. It is worth investing a lot of time and effort in order to find it and gain it, to understand it. And that's the moral.’

- A. Sapkowski

Swiat króla Artura. Maladie

In this reading, we find the framing to the stories of Geralt and Yennefer, Lara and Cregennan, Avallac’h and Lara, and many others. Including the story of Ciri herself – for Ciri is ultimately the author’s Grail in more ways than one. More than one party goes to great lengths to solicit her favour in a guise that includes elements of a love relationship but not the heart of it.

Secondly, we can interpret the legend in universal terms: the shard of ice is the definitive experience of our lives which distorts reality and makes the rest of our lives spin around it in one way or another. For Emhyr, such an experience could have been the trauma experienced in his youth. Fergus’ uncompromising death conditioned the boy early on to sacrifice personal feelings to the cause and let the only true feeling in his heart remain forever locked behind the ends a ruler must go to unthinkable lengths to achieve. Fergus did not deem his son above suffering for a cause and the son learned the lesson. Until…

In Andersen’s Snow Queen, Gerda manages to find her brother Kai in the Snow Queen’s castle, but despite her calls his heart remains cold as ice. Only when Gerda cries in despair do her tears finally melt the ice and remove the piece of glass from Kai’s eyes and heart. In the Witcher, the shard in Emhyr’s heart moves first upon witnessing his true daughter’s angry tears. For the second time – in thanks to the bogus princess of Cintra; his poor raison d’etat.

It brings us to the defining contrast in Emhyr’s and Auberon’s stories, and it concerns alleviating the suffering of those are bound to you by blood or love.

Recalling another case of incest that resulted in Adda the strigga, we may remember that the Temerian king recognises that his daughter is suffering and insists on disenchanting her instead of killing her. Realising that your own blood – who has been thrown into this world of suffering thanks to you – is suffering and consequently choosing to do something to alleviate this suffering fortifies the Saga’s faith in enduring human decency. Geralt himself is thoroughly vexed by the prospect of letting the same evil happen to Ciri that happened to himself and does everything within his power to prevent it (failing, trying anyway). Here lives the redemption of man, and in redemption his rebirth.

‘They passed a pond, empty and melancholy. The ancient carp released by Emperor Torres had died two days earlier.

“I’ll release a new, young, strong, beautiful specimen,” thought Emhyr var Emreis, “I’ll order a medal with my likeness and the date to be attached to it. Vaesse deireadh aep eigean. Something has ended, something is beginning. It’s a new era. New times. A new life. So let there be a new carp too, dammit.”’

- Lady of the Lake

As Emhyr and false-Cirilla take a stroll in the gardens after Stygga, they pass a sculpture of a pelican pecking open its own breast to feed its young on its blood. An allegory of noble sacrifice and also of great love – as False-Ciri tells us.

‘Do you think—’ he turned her to face him and pursed his lips ‘—that a torn-open breast hurts less because of that?’

‘I don’t know …’ she stammered. ‘Your Imperial Majesty … I …’

He took hold of her hand. He felt her shudder; the shudder ran along his hand, arm and shoulder.

‘My father,’ he said, ‘was a great ruler, but never had a head for legends or myths, never had time for them. And always mixed them up. Whenever he brought me here, to the park, I remember it like yesterday, he always said that the sculpture shows a pelican rising from its ashes.’

- Lady of the Lake

It is difficult to set aside our trauma and not pass it on to our children. Letting our children be free to choose and not sacrificing them on the altar of our fate is to rip open ourselves, calcified and bound to our path, and to feel all of it as we grope in the dark to feel for them. Emhyr’s father might not have gotten it entirely wrong, though his mind at the time was set on making his child an extension of himself. The cycle of death and rebirth begins and ends within that to which we give birth. Giving our children a chance before it is too late, we also give a chance to ourselves. By finding it in his heart to extend to his daughter the courtesy his father Fergus never extended to him - by letting Ciri free - Emhyr lets the part of himself that has defined his entire life die. His end stops justifying the means. He breaks the cycle on the edge of the precipice to which he has brought them and thus allows for the possibility of new beginnings for himself and for Ciri.

In a sense, False-Cirilla and Emhyr get the ending Ciri and Auberon might have gotten if –

If.

The story of Auberon Muircetach achieves a fundamentally different resolution.

‘What does the spear with the bloody blade mean? Why does the King with the lanced thigh suffer and what does it mean? What is the meaning of the maiden in white carrying a grail, a silver bowl—?’

- Galahad

Lady of the Lake

Galahad asks the questions that the innocent Perceval in his Story of the Grail failed to ask, thus losing his chance at freeing the Fisher King from his curse. And the Fisher King is the guardian of mysteries, among them the Holy Grail. But it is not because of gain that a chivalric knight with a shining sword should seek to free the Fisher King from his curse, but rather because it is a human thing to do. Sapkowski claims to be partial to Wolfram von Eschenbach’s rendition of the Grail myth in Parsifal. Wolfram’s message, according to Sapkowski, is the following:

‘Let's not wait for the revelation and the command that comes from above, let's not wait for any Deus vult. Let's look for the grail in ourselves. Because the Grail is nobility, it is the love of a neighbor, it is an ability for compassion. Real chivalric ideals, towards which it is worth looking for the right path, cutting through the wild forest, where, as they quote, "there is no road, no path". Everyone has to find their path on their own. But it is not true that there is only one path. There are many of them. Infinitely many. … Being human is important. Heart.’

‘I prefer the humanism of Wolfram von Eschenbach and Terry Gilliam from the idiosyncrasies of bitter Cistercian scribes and Bernard of Clairvaux...’

- A. Sapkowski

Swiat króla Artura: Maladie

The unimaginable sadness in Auberon’s eyes belies the suffering of the Alder King who is the avatar of the Fisher King. In the Witcher’s story between elves and humans, it is the elven males who all share aspects of the Fisher King’s fate, because they are the keepers of their Grail – the protectors of elven women. Auberon’s wound is wrought by time: by surviving his wife and daughter, by the witnessing of the fading of his ambitions and the results of pursuing them without success. He has lost his line. The Fisher King’s injury represents the inability to produce an heir. A ruler who is the protector and physical embodiment of his land, yet remains barren, sterile, or without a true-born successor, bodes ill for the realm. The Alder King’s injury consists in having lost control of the source of his people’s power, leaving the elves imprisoned and scattered across two worlds. Auberon’s personal tragedy, however, subsists in the lost power having been functionally manifest in a daughter.

‘Lara.’ The Alder King moved his head, and touched his neck as though his royal torc’h was garrotting him. ‘Caemm a me, luned. Come to me, daughter. Caemm a me, elaine.’

Ciri sensed death in his breath.

- Lady of the Lake

Elder Blood is indeed an accursed blood because it enslaves its carriers to its purpose. Emhyr has a theoretical chance to walk away from the pursuit of earthly power; the construct is social. Elder Blood, however, has a particular and real, magical function, and in virtue of being a genetic mutation it is embedded in the gene-carrying individuals. Functionally, Elder Blood allows to shape fate with degrees of freedom unimaginable for an ordinary individual. It’s a difference comparable to the one between a character in a story and the story’s author. Therefore the Aen Saevherne – the carriers of the gene – are bound to the thing they carry within their DNA that allows them to a greater and lesser degree shape the fate of reality. However dearly Auberon, or Lara, might have ever wished to untie themselves from their own essence, it seems impossible. The loss of control over power then is quite simply so pivotal as to necessitate a moment of original sin.

As already witnessed by way of the legend of the Winter Queen, the original “myths” of the Witcher world usually originate among elves; humans, the interlopers, push themselves into those myths only later. This creates an interesting conundrum. In Parsifal, the Fisher King is injured as punishment for taking a wife who is not meant for him. A Grail keeper is to marry the woman the Grail determines for him, which – if we equate woman with the Grail – is what the woman determines. Unfortunately, we know nothing about Shiadhal, so we cannot verify if this part of the legend dovetails. But generally, in a wholly elven world which may have matriarchal tendencies, in lieu of worshipping the mother Goddess, such cosmology is relatively unproblematic. Except suddenly there are humans too. And Auberon – the highest leader of elves and the father of the new scion of Elder Blood – is indirectly injured because a human sorcerer – Cregennan – turns himself into a Grail keeper (in place of another, special elf) by taking a woman not meant for him.

‘Witcher,’ she whispered, kissing his cheek, ‘there’s no romance in you. And I… I like elven legends, they are so captivating. What a pity humans don’t have any legends like that. Perhaps one day they will? Perhaps they’ll create some? But what would human legends deal with? All around, wherever one looks, there’s greyness and dullness. Even things which begin beautifully lead swiftly to boredom and dreariness, to that human ritual, that wearisome rhythm called life.’

- Yennefer

Sword of Destiny

Cregennan’s injury is to die. But what about the original Fisher King figure? What is Auberon’s original sin in this?

I see two possibilities. It could be that Auberon in his ambition hastened his daughter’s way into exile and, in a display of his displeasure, never made any effort to ease his daughter in to the personal sacrifices they, as Aen Saevherne, must make; walking without blinking to the end of the path Emhyr turned away from. It could equally be that Auberon, instead of locking Lara up in a tower to protect her from the folly of youth, let her go to Cregennan. It could be an amalgam of both, and the misjudgement of a father who allows freedom, who feels for his child, and is rewarded with an irreversible injury is probably the greater tragedy.

Because, regardless of the origin of the curse upon Auberon, one thing does not change – the icy eternity in the Alder King’s heart never fractures.

‘‘Zireael,’ he said. ‘Loc’hlaith. You are indeed destiny, O Lady of the Lake. Mine too, as it transpires.’

- Auberon

Lady of the Lake

Ciri passes through the shadow world of the Alders; a manifestation of fate. Her footsteps sowing discord and movement and change into the immutable, time-locked amber of the elven utopia. Her presence providing the trigger that will unshackle the past from future in a world where for a long time nothing has changed, died, or been reborn. She is destined and destiny, annihilation and rebirth, the grain of sand in the gears of the great mechanism; a strange girl. The child of hope and the Goddess who ought to be Three. Lara, the true daughter of the Alder King, is dead. Emhyr’s daughter still lives. There is nothing Auberon can do for Lara anymore and thus the ice in Auberon’s heart has crystallised. Emhyr still has a chance; he is where Auberon once was. And yet, there is one thing Ciri, the witcher girl with a sword of her own, can still do for the Alder King.

‘Va’esse deireadh aep eigean… But,’ he finished with a sigh, ‘it’s good that something is beginning.’

They heard a long-drawn-out peal of thunder outside the window. The storm was still far away. But it was approaching fast.

‘In spite of everything,’ he said, ‘I very much don’t want to die, Zireael. And I’m so sorry that I must. Who’d have thought it? I thought I wouldn’t regret it. I’ve lived long, I’ve experienced everything. I’ve become bored with everything … but nonetheless I feel regret. And do you know what else? Come closer. I’ll tell you in confidence. Let it be our secret.’

She bent forward.

‘I’m afraid,’ he whispered.

‘I know.’

‘Are you with me?’

‘Yes, I am.’

- Auberon

Lady of the Lake

The only way Ciri the Grail knight will be able to find her true self – the Grail – is to cure the suffering Alder King from his curse. Ciri’s presence in the world of the Alders is after all also part of her coming of age story. Through becoming Auberon’s destiny, Ciri must close the circle for him and bring closure. He would never let her go because the shard in Auberon’s heart is no longer able to melt. Auberon does not follow the motif of alleviating the suffering of one’s blood and/or love; and he dies. The roles are reversed, in fact. It is Ciri who realises Auberon is suffering. So Ciri must do what only she can do, because remaining human is important. Heart is important. The sacrifice a ruler makes on the altar of power includes his own heart, which is why there should never be only one, but always two; always.

‘Time is like the ancient Ouroboros. Time is fleeting moments, grains of sand passing through an hourglass. Time is the moments and events we so readily try to measure. But the ancient Ouroboros reminds us that in every moment, in every instant, in every event, is hidden the past, the present and the future. Eternity is hidden in every moment. Every departure is at once a return, every farewell is a greeting, every return is a parting. Everything is simultaneously a beginning and an end.

‘And you too,’ he said, not looking at her at all, ‘are at once the beginning and the end. And because we are discussing destiny, know that it is precisely your destiny. To be the beginning and the end. Do you understand?’

She hesitated for a moment. But his glowing eyes forced her to answer.

‘I do.’

- Lady of the Lake

Death Crone to Auberon Muircetach, Ciri never becomes the Mother Goddess in the Saga. It is a choice she must make for herself and the choice still lies ahead of her. The predicate to making such a choice at least for now, however, she achieves; she goes her own way. In a sense then, both rulers are father figures, who through their choices “beget” the child who is destined. Perhaps this too the Knowing Ones knew, and for this reason Auberon never could have budged, never could have changed his mind in regard to his purpose in the long and winding story of his life. Something is ending, but something is also beginning. A good ruler is responsible for the flourishing of their realm, for providing hope. It is Ciri’s role to be the beginning and the end, and though there might be ways in which to nudge the hand of Fate, whatever is destined must happen. Destiny, however accursed, must run its course.

That is the hope and the release.

---

If you like my writing, consider buying me a coffee.

Thanks! ❤️

#wiedźmin#the witcher#andrzej sapkowski#the witcher lore#the witcher meta#analysis#auberon muircetach#emhyr var emreis#cirilla fiona elen riannon#ciri#aen elle#nilfgaard#arthurian legend#arthuriana#Swiat Krola Artura#wicca#celtic mythology#history of the british isles#elder blood#lara dorren#fisher king#snow queen#fairy tales#longform#writing#false-cirilla#tw: inc*st#aen saevherne#ithlinne's prophecy#winter queen

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 23: Esclados, Lord of the Storm-Fountain

The otherworldly protector of Broceliande forest, Esclados was accidentally summoned by Sir Calogrenant when he stumbled upon a fountain in a hidden glade. He spilled some of the water from the fountain, causing a storm and drawing the spirit out to defeat him for his impudence.

Many years later, his cousin Sir Ywain travelled to the same fountain, drew out Esclados and destroyed him, taking his place as the guardian of the fountain.

I intended this sketch to be for the Black Knight, brother to the Faerie Knight, but it just refused to look right. So I made him into a different red and spiky character, and liked it much better!

#arthurian knights#arthurian lore#arthurian mythology#arthurian fantasy#arthurian legend#king arthur#celtic mythology

23 notes

·

View notes