Text

Reblogged by Shane Lehane Sheelah take a bow: St Patrick’s wife? Probably not – she was far more important than that

A symbol of Irish womanhood, she deserves to be celebrated again every March 18th

The 16th, 17th (St Patrick’s Day) and 18th March: Erskine Nicol’s painting of the Irish celebration that included Sheelah’s Day. Photograph courtesy of the National Gallery of Ireland

Shane Lehane

Fri Mar 15 2019 - 06:00

For hundreds of years Ireland has had an icon of womanhood and a compelling symbol of all things female, yet few people know her name. The forgotten goddess is none other than Sheelah, once widely celebrated on March 18th, both in Ireland and among the diaspora, yet now all but disappeared. Fáilte Ireland should start to champion her alongside St Patrick: she could be worth a fortune.

Two years ago my research into this disregarded deity resulted in somewhat misleading headlines that said Sheelah was St Patrick's wife. That was not the case, but at least it brought Sheelah and her festival back to our attention. I believe Sheelah – or Sheila, Sheela, Shela, Sheelagh or Síle, depending on the source – has far more to her than the once widely held belief that she was our national saint's other half.

Sheelah's Day fell each year on March 18th, and the usual dispensation to disregard Lenten abstinence on March 17th and wet the shamrock – drink alcohol, in other words – in honour of St Patrick was extended to the following day as well, in honour of his so-called wife. The Freeman's Journal of March 20th, 1841, reported that a woman who appeared in court for drunkenness declared she bought "two small naggin of whiskey… not wishing to break through the old custom of taking a drop on St Sheelah's Day". In contrition to the judge, she vowed: "I here promise that for Patrick's Day or Sheelah's Day, or any other day in the calendar, I'll never stand in your presence again."

Some say Sheelah was 'Patrick's wife', others that she was 'Patrick's mother', while all agree that her 'immortal memory' is to be maintained by potations of whiskey

A painting by Erskine Nicol from 1856, depicting the revelries of such mid-Lenten festivities, is accurately entitled The 16th, 17th (St Patrick’s Day) and 18th March. This elongated name recognises that most Irish festivals, including fairs, pattern days and wakes, took place over three days: the gathering, the feast and the scattering. Sheelah’s Day was the last (but not the least) of the traditional three days of celebration that began on the eve of St Patrick’s Day.

William Hone gives a detailed account of Sheelah’s Day celebrations in Britain in The Every-day Book, from 1827.

“The day after St Patrick’s Day is ‘Sheelah’s day’, or the festival in honour of Sheelah. Its observers are not so anxious to determine who ‘Sheelah’ was, as they are earnest in her celebration. Some say she was ‘Patrick’s wife’, others that she was ‘Patrick’s mother’ while all agree that her ‘immortal memory’ is to be maintained by potations of whiskey. The shamrock worn on St Patrick’s day should be worn also on Sheelah’s day, and on the latter night, be drowned in the last glass. Yet it frequently happens that the shamrock is flooded in the last glass of St Patrick’s day, and another last glass or two or more on the same night, deluges the over-soddened trefoil. This is not ‘quite correct’ but it is endeavoured to be remedied the next morning by the display of fresh shamrock, which is steeped at night in honour of ‘Sheelah’ with equal devotedness.”

This festive time coincides with the vernal equinox, one of the two midpoints of the sun’s annual cycle, in the season of new fertility, when days are poised to outlast nights for the first time since the autumn equinox, the previous September. An emphasis on new life and procreation is manifest in a host of mythological incarnations and folk reflexes at this time of the year. The goddess and holy woman Brigid is celebrated on February 1st; the analogous figure of Gobnait, goddess of fertility and beekeeping, is commemorated on February 11th. These women usher in the new cycle of fertility with ploughing, sowing, the birth of animals, the rising of the sap and the reawakening of nature.

This time of year in the past brought an equal emphasis on human marriage and reproduction, with Shrove Tuesday, immediately before Lent, long being the most popular day in Ireland to be married.

The three-day carnival celebrating Patrick and Sheelah occurs at this key point in the calendar and in the annual cycle of fertility. That Sheelah is firmly situated around the equinox, the seminal pivot of fertility, indicates that she had distinct fertility associations and can be viewed as an equivalent to Brigid and Gobnait.

Patrick is fighting with his wife, now a miserable hag at war with the world. She spitefully brushes the last of the winter snow into the way of the new cycle of work

Sheelah still echoes through Newfoundland, otherwise known as Talamh an Éisc, or Land of the Fish, the most Irish place outside Ireland. An amazing legend on this Canadian island, which many still believe to be true, centres on Sheila na Geira, or Síle Ní Ghadhra, a young Irish princess from Connacht. Sometime in the 1600s, when she was en route to a French convent to finish her education under the care of her abbess aunt, pirates commandeered her ship. One of them, Gilbert Pike, from a well-to-do English family, fell in love with her. They married aboard and then settled down in Mosquito, in southwestern Newfoundland. Here, in time, Sheila na Geira gave birth to a child – according to tradition the first white European child to be born in Newfoundland – so it is said that many there owe their lineage to her. It is also said that every Irishman who visited and settled on Newfoundland paid obeisance to Sheila na Geira, who reportedly lived to 105.

In Ireland, especially from the mid-18th century onwards, Síle Ní Ghadhra was one of the most popular representations of the country, and in the aisling, or dream, poetry of the period she epitomises Ireland in its idyllic state: strongly independent, bountiful and fertile. In this sense Sheila joins the many women sovereignty figures who represent Ireland: Ériu, Fódla, Banba, Aoibheall, Clíodhna, Macha, Mór and Mórrígan, to name a few (and not forgetting the Christianised figures of Brigid and Gobnait).

In keeping with her mother-goddess attributes, the last big snowstorm after St Patrick’s Day is still called Sheila’s brush in Newfoundland. The idea is that Patrick is fighting with his wife, now a miserable hag at war with the world. (The idea that Patrick had a wife called Sheila must have arrived with the Irish of the 18th and 19th centuries.) She spitefully brushes the last of the winter snow into the way of the new cycle of work.

It’s significant that Síle na géag, or Sheila of the brush, is one way to render Sheela-na-gig, the name for the naked old woman who appears, exposing her genitals, in medieval stone carvings. We’ll return to this. As for the Newfoundland Sheila’s brush, sealing fleets would refuse to go back out on the ice until this storm had passed; fishermen continue to do so.

Sheila’s brush: Newfoundland fishermen would wait for the first snowstorm after St Patrick’s Day to pass before going back out to sea. Photograph: NFB/Getty

Sheelah is an enigmatic name. It and all its variant spellings appear only about 500 times in the 1911 census of Ireland. By contrast its English equivalent, Julia, has almost 30,000 entries. Similarly, no Sheilas appeared on the manifests for ships taking women convicts to Australia, even though the name has entered the language there as jocular but mildly pejorative slang for a woman or girlfriend.

That Freeman’s Journal court report from 1841 refers to the defendant as “a half-naked, wretched looking old woman” who was “charged with having been found drunk and incapable in the street”. The headline was “A Sheelah’s Forethought”. This and many other references made “Sheelah” a byword for a bedraggled old woman.

But elderly women also had experience of the world and were custodians of inherited knowledge, playing significant roles in rites of passage in the human life cycle and the cycle of the year. They acted as midwives, corpse washers and professional mourners; they advised on herbalism and vernacular medicine; and they were central to events such as the pattern day. In this respect Sheelah, as the old woman, is strongly resonant of the important Irish folk figure known as the Cailleach.

The Cailleach – the old, wise healer – is a multifaceted personification of the female cosmic agency. Irish mythological, historical and folkloric expressions cast her as the expression of the territorial- and tribal-sovereignty queen and as the life force inherent in nature, nurturing and maternal but also terrifying and destructive.

Sheela-na-gig: the medieval stone carvings show folk deities associated with birth and death. Photograph: Getty

The Cailleach tradition’s deep roots in ideas of birth, fertility and death brings us back to the Sheela-na-gig. Ireland has more than 100 examples of these often-misunderstood medieval stone carvings. The women in them, who are reclining or squatting, often have big ears, long hair, gritted teeth, emaciated ribs and prominent breasts.

They often appear on medieval tower houses, medieval church sites and holy wells. I recently came across one on a round tower in Rattoo, in Co Kerry. For a long time they were seen as representations of the evils of lust or as ways of averting the “evil eye”. But Sheela-na-gigs are more convincing, in line with the Cailleach, as folk deities associated with birth and death. And so Sheelah embodies the cycle of fertility that overarches natural, agricultural and human procreation and death.

That Sheelah was thought of as St Patrick’s wife is a significant folk reflex. The cult of Patrick is firmly based on the pre-Christian deity Lug, or Lugh – as in Lughnasa or Lúnasa, the harvest festival – who represents the male side of the life-giving equation. Lug personifies the ideal man, exemplified in the complex ideology of Irish kingship. It is the union of male and female that allows us to exist.

It should be no surprise, then, that the three-day carnival to celebrate St Patrick, a major Christian icon, at the liminal point of the season of fertility, when human procreation is paramount, should include Sheelah, his consort.

As many of her devotees died in the Famine, and given the influence of the misogynist, patriarchal church, she has all but vanished from Irish life. I, for one, will be raising a glass to her on her feast day.

Shane Lehane teaches archaeology, folklore and history at CSN College of Further Education, in Cork, and lectures in the department of folklore and ethnology at University College Cork. He is always interested to hear about local folk custom and tradition; you can email him at [email protected]

I hope you enjoyed this Reblog more to come soon

Regards,

Culture Calypso’s Blog

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Todays blog is on Litha Summer Solstice enjoy!

🌻🌞🌻🌞🌻🌞🌻🌞🌻🌞🌻🌞🌻🌞🌻🌞🌻

An Ancient Solar Celebration

Nearly every agricultural society has marked the high point of summer in some way, shape or form. On this date–usually around June 21 or 22 (or December 21/22 in the southern hemisphere)–the sun reaches its zenith in the sky. It is the longest day of the year, and the point at which the sun seems to just hang there without moving – in fact, the word “solstice” is from the Latin word solstitium, which literally translates to “sun stands still.” The travels of the sun were marked and recorded. Stone circles such as Stonehenge were oriented to highlight the rising of the sun on the day of the summer solstice.

Did You Know?

Early European traditions celebrated midsummer by setting large wheels on fire and then rolling them down a hill into a body of water.

The Romans honored this time as sacred to Juno, the wife of Jupiter and goddess of women and childbirth; her name gives us the month of June.

The word “solstice” is from the Latin word solstitium, which literally translates to “sun stands still.”

Traveling the Heavens

Although few primary sources are available detailing the practices of the ancient Celts, some information can be found in the chronicles kept by early Christian monks. Some of these writings, combined with surviving folklore, indicate that Midsummer was celebrated with hilltop bonfires and that it was a time to honor the space between earth and the heavens.

Angela at A Silver Voice says that midsummer, or St. John's Eve, was often celebrated in Ireland with the lighting of huge bonfire. She points out that this is an ancient custom rooted in a Celtic tradition of lighting fires in honor of Áine, the Queen of Munster,

Festivals in her honour took place in the village of Knockainey, County Limerick (Cnoc Aine = Hill of Aine ). Áine was the Celtic equivalent of Aphrodite and Venus and as is often the case, the festival was ‘christianised’ and continued to be celebrated down the ages. It was the custom for the cinders from the fires to be thrown on fields as an ‘offering’ to protect the crops.

Fire and Water

In addition to the polarity between land and sky, Litha is a time to find a balance between fire and water. According to Ceisiwr Serith, in his book The Pagan Family, European traditions celebrated this time of year by setting large wheels on fire and then rolling them down a hill into a body of water. He suggests that this may be because this is when the sun is at its strongest yet also the day at which it begins to weaken. Another possibility is that the water mitigates the heat of the sun, and subordinating the sun wheel to water may prevent drought.

Christians have chronicled the rolling of flaming (solar) wheels since the Fourth Century of the Common Era. By the 1400’s the custom was specifically associated with the Summer Solstice, and there it has resided ever since (and most likely long before)... The custom was apparently common throughout Northern Europe and was practiced in many places until the beginning of the Twentieth Century.

When they arrived in the British Isles, the Saxon invaders brought with them the tradition of calling the month of June. They marked Midsummer with huge bonfires that celebrated the power of the sun over darkness. For people in Scandinavian countries and in the farther reaches of the Northern hemisphere, Midsummer was very important. The nearly endless hours of light in June are a happy contrast to the constant darkness found six months later in the middle of winter.

Roman Festivals

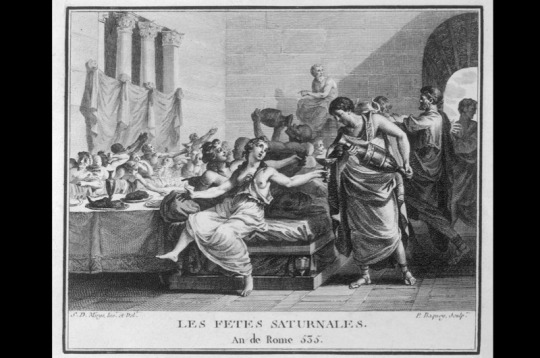

The Romans, who had a festival for anything and everything, celebrated this time as sacred to Juno, the wife of Jupiter and goddess of women and childbirth. She is also called Juno Luna and blesses women with the privilege of menstruation. The month of June was named for her, and because Juno was the patroness of marriage, her month remains an ever-popular time for weddings. This time of year was also sacred to Vesta, goddess of the hearth. The matrons of Rome entered her temple on Midsummer and made offerings of salted meal for eight days, in hopes that she would confer her blessings upon their homes.

Midsummer for Modern Pagans

Litha has often been a source of contention among modern Pagan and Wiccan groups, because there's always been a question about whether or not Midsummer was truly celebrated by the ancients. While there's scholarly evidence to indicate that it was indeed observed, there were suggestions made by Gerald Gardner, the founder of modern Wicca, that the solar festivals (the solstices and equinoxes) were actually added later and imported from the Middle East. Regardless of the origins, many modern Wiccans and other Pagans do choose to celebrate Litha every year in June.

In some traditions, Litha is a time at which there is a battle between light and dark. The Oak King is seen as the ruler of the year between winter solstice and summer solstice, and the Holly King from summer to winter. At each solstice they battle for power, and while the Oak King may be in charge of things at the beginning of June, by the end of Midsummer he is defeated by the Holly King.

This is a time of year of brightness and warmth. Crops are growing in their fields with the heat of the sun, but may require water to keep them alive. The power of the sun at Midsummer is at its most potent, and the earth is fertile with the bounty of growing life.

For contemporary Pagans, this is a day of inner power and brightness. Find yourself a quiet spot and meditate on the darkness and the light both in the world and in your personal life. Celebrate the turning of the Wheel of the Year with fire and water, night and day, and other symbols of the opposition of light and dark.

Litha is a great time to celebrate outdoors if you have children. Take them swimming or just turn on the sprinkler to run through, and then have a bonfire or barbecue at the end of the day. Let them stay up late to say goodnight to the sun, and celebrate nightfall with sparklers, storytelling, and music. This is also an ideal Sabbat to do some love magic or celebrate a handfasting, since June is the month of marriages and families.

What is Litha? – Summer Solstice 2021

In the Northern Hemisphere, Sunday 21st June brings us the annual celebration of Litha – also known as Midsummer, Summer Solstice, Gathering Day and St. John’s Day amongst many other names. The Summer Solstice is one of the 8 Pagan Sabbats along with Beltane, Ostara, Lughnasadh, Autumn Equinox, Samhain, Yule and Imbolc. Litha honors the longest day of the year and is a celebration of life, growth and the power of the sun.

How To Celebrate Litha

Many ancient cultures marked the Summer Solstice with communal festivities and rituals honoring the sun. This would often include great feasts, Morris Dancing, storytelling, singing and and of course the burning of bonfires. These symbolic Litha fires were believed to possess great power and offer the strength of the sun which in turn would bring abundance, prosperity and protection to the community. A common ritual undertook at these ancient festivals was the act of jumping over the bonfire – couples especially would take part in this to ensure a long and happy marriage as well as a fruitful harvest.

People still honour Litha to this day and modern celebrations retain the traditional lighting of bonfires, often with friends and family for outdoor gatherings and BBQs. It is not unusual to be invited to a Handfasting ceremony (a traditional Pagan/Wiccan wedding) at this time of year as Litha is a popular time to celebrate love, marriage, companionship and fertility. Some people like to make personal/household Altars to celebrate the Solstice, either indoors or outdoors, often displaying the colours, symbols and scents of the season and containing offerings to the deities of the sun. As well as the fae

Litha Altar Checklist:

Colours: Red, Gold, Orange, Yellow, Green.

Decorations: Sunflowers, Roses, Oak Tree, Shells.

Gemstones: Sunstone, Tiger Eye, Green Gemstones.

Symbols: Sun Symbol (circles/discs), Fire Symbols (candles).

Fragrance/Incense: Sage, Mint, Basil, Sunflower, Lavender, St John’s Wort.

I hope you enjoyed this blog more to come soon

Blessed be,

Culturecalypsosblog.Tumblr.com 🌻🌞🔥

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Todays blog is on Persephone, Queen of the Underworld 🌹🥀🩸🌺💀🔥💐🍇🦋

The story of Persephone, the sweet daughter of goddess Demeter who was kidnapped by Hades and later became the Queen of the Underworld, is known all over the world. It is actually the way of the ancient Greeks to explain the change of the seasons, the eternal cycle of the Nature's death and rebirth. Persephone is understood in people's mind as a naive little girl who flows between the protection of the mother and the love of her husband. The myth of Persephone was very popular in the ancient times and it is said that her story was represented in the Eleusinian Mysteries, the great private and secret celebrations of ancient Greece.

Discover the myth of Persephone, the Queen of the Underworld

The abduction from Hades

According to Greek Mythology, Persephone, the queen of the underworld, was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, the goddess of harvest and fertility. She was also called Kore, which means "maiden" and grew up to be a lovely girl attracting the attention of many gods. However, Demeter had an obsessed love for her only daughter and kept all men away from her.

The most persisting suitor of Persephone was Hades, the god of the Underworld. He was a hard, middle-aged man, living in the dark, among the shadows of the Dead. But his heart softened when he saw Persephone and was amazed by his youth, beauty and freshness. When he asked Demeter to marry her daughter, Demeter got furious and said there wasn't the slightest chance for that to happen. Hades was heart-broken and decided to get Persephone no matter what.

One day, while the young girl was playing and picking flowers along with her friends in a valley, she beheld the most enchanting narcissus she had ever seen. As she stooped down to pick the flower, the earth beneath her feet suddenly cleaved open and through the gap Hades himself came out on his chariot with black horses. Hades grabbed the lovely maiden before she could scream for help and descended into his underworld kingdom while the gap in the earth closed after them.

Desperately looking for Persephone

The other girls had not seen anything because everything happened very quickly. They didn't have a clue for the sudden disappearance of Persephone. The whole incident, however, had been witnessed by Zeus, father of the maiden and brother of the abductor, as well as by Helios, god of the Sun. Zeus decided to keep silent about the whole thing to prevent a fight with his brother while Helios wisely thought it better not to get involved in anything that didn't concern him.

A distraught and heartbroken Demeter wandered the earth looking for her daughter until her good friend Hecate, goddess of wilderness and childbirth, advised her to seek for the help of Helios, the all-seeing Sun god, in order to find her daughter. Helios felt sorry for Demeter, who was crying and pleading him to help her. Thus she revealed her that Persephone had been kidnapped by Hades. When she heard that, Demeter got angry and wanted to take revenge but Helios suggested that it was not such a bad thing for Persephone to be the wife of Hades and queen of the dead.

Trying to find a solution

Demeter, however, could not let it gone. She was furious at this insult and deeply believed that Hades, who after all had only dead people for company, was not the right husband for her sweet daughter. She also got angry at Zeus for not having revealed this to her. To punish gods and to grief, Demeter decided to take a long and indefinite leave from her duties as the goddess of harvest and fertility, with devastating consequences. The earth began to dry up,harvests failed, plants lost their fruitfulness, animals were dying for lack of food and famine spread to the whole earth, resulting in untold misery.

The cries of the people who were suffering reached Olympus and the divine ears of Zeus. The mighty god finally realized that if he wouldn't do something about his wife's wrath, all humanity would disappear. Thus he tried to find another solution to both calm Demeter and please Hades. He promised Demeter to restore Persephone to her if it can be proved that the maiden stays with Hades against her will. Otherwise, Persephone belongs to her husband.

The final solution

The crafty Hades learned this agreement and tricked his reluctant bride, who was crying all day and night from despair, to eat a few seeds of the pomegranate fruit. This was the food of the Underworld and every time someone ate even a few seeds of this, then, after a while, he would miss life in the Underworld. When the gathering in front of Zeus took place and Persephone was asked where she would like to live, she answered she wanted to live with her husband. When Demeter heard that, she got infuriated and accused Hades that somehow he had tricked her daughter.

A great fight followed and Demeter threatened that she would never again make the earth fertile and everyone on Earth would die. To put an ed on this quarrel, Zeus decided that Persephone would spend half months with her husband in Hades and half months with her mother on Olympus. This alternative pleased none of the two opponents, nevertheless that had no other option but accept it.

The explanation of the myth

Thus the lovely maiden Persephone became the rightful wife of Hades and Queen of the Underworld. During the six months that Persephone spent in the Underworld, her mother was sad and not in the mood to deal with harvest. Thus she would leave the Earth to decline.

According to the ancient Greeks, these were the months of Autumn and Winter, when the land is not fertile and does not give crops. Whenever Persephone went to Olympus to live with her mother, Demeter would shine from happiness and the land would become fertile again and fruitful. These were the months of Spring and Summer. Therefore, this myth was created to explain the change of the seasons, the eternal cycle of the Nature's death and rebirth.

More info:

Overview

Persephone, often known simply as Kore (“Maiden”), was a daughter of Zeus and Demeter. Her mythology tells of how she was abducted by her uncle Hades one day while picking flowers. Demeter, distraught, wandered the entire world in search of her daughter.

When Demeter at last located Persephone in the Underworld, she demanded that her daughter be returned. But Hades had tricked Persephone into eating something—a handful of pomegranate seeds—while she was in the Underworld. Thus, although Persephone was allowed to spend part of the year on Olympus with her mother, she was forced to spend the other part of the year in the Underworld as Hades’ bride.

As the wife of Hades, Persephone was the queen of the Underworld. She was also associated with spring, girlhood, and marriage. Persephone was often worshipped alongside her mother, Demeter—for example, in the Eleusinian Mysteries.

Etymology

Ancient authors sometimes sought creative etymologies for the name “Persephone” (Greek Περσεφόνη, translit. Persephonē). Plato, for example, interpreted the name as “she who touches things that are in motion” (epaphē tou pheromenou), a reference to Persephone’s wisdom (to touch things that are in motion implies an understanding of the cosmos, which is constantly in motion).[1]

Other ancient etymologies connected Persephone’s name with aphenos (“wealth”), phonos (“death”), and phōs (“light”). But these are folk etymologies that lack credibility.

Nowadays, Persephone’s name is often thought to have Indo-European origins. Robert Beekes and others have connected it to two Indo-European roots: *perso- (“sheaf of corn”) and *-gʷn-t-ih₂ (“hit, strike”). This would indicate that Persephone’s name means something like “female corn thresher.”[2]

Pronunciation

ENGLISH

GREEK

Persephone

Περσεφόνη (translit. Persephonē)

PHONETIC

IPA

[per-SEF-uh-nee]

/pərˈsɛf ə ni/

Alternate Names

The name Kore (Korē, “Maiden”) was commonly used as an alternative to “Persephone” and highlighted the goddess’s role as the daughter of Demeter, goddess of agriculture. Another alternate name, Despoina (“Mistress”), focused on Persephone’s role as the wife of Hades and queen of the Underworld.

There were several alternate forms of the name “Persephone” itself, including Persophatta or Persephatta (which may have been the original form of the name), Persephoneiē (the Homeric form), Pherrephatta, and Phersephonē.

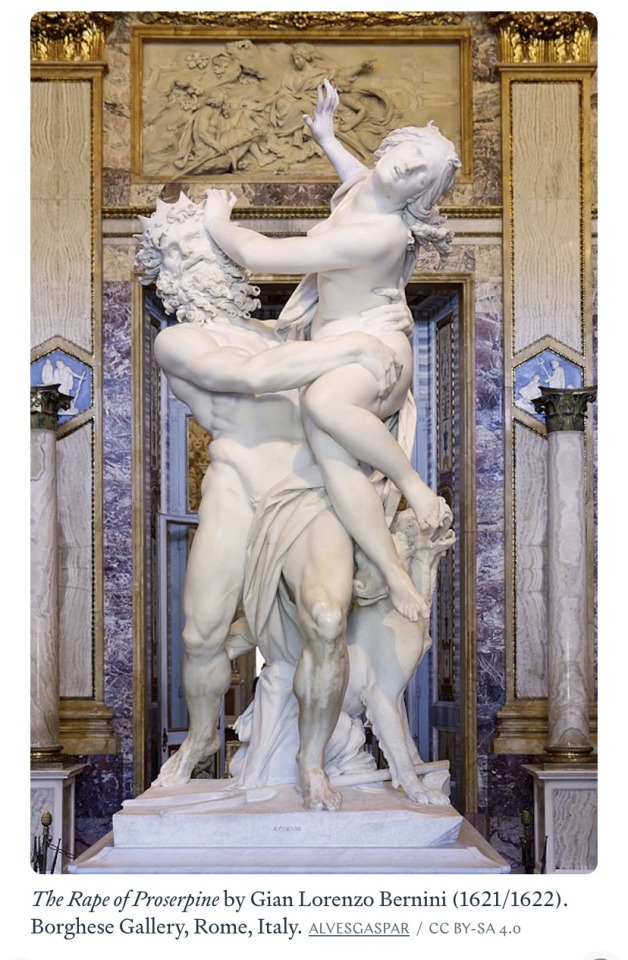

Persephone’s Roman counterpart was called Proserpina or Proserpine.

Titles and Epithets

Persephone was known by numerous cult titles, including Sōteira (“Savior”) and Brimō (“Angry”). She also had a handful of epithets. These included epainē (“awful”), which stressed Persephone’s role as queen of the Underworld, as well as agauē (“venerable”), hagnē (“holy”), and arrētos (“she who must not be named”).

Attributes

There were two sides to Persephone. On the one hand, she was Persephone, wife of Hades and goddess of the Underworld, and thus a chthonic figure closely associated with the inevitability of death. On the other hand, she was Kore, the maiden daughter of the agricultural goddess Demeter, an alternate guise that brought her into the sphere of agriculture and fertility. In her ritual and mythology, Persephone/Kore was also regarded as a goddess of all aspects of womanhood and female initiation, including girlhood, marriage, and childbearing.

True to her double nature, Persephone was imagined as having two homes: one on Olympus with her mother, Demeter, and the other in the Underworld with her husband, Hades. According to Homer, she also possessed sacred groves on the western edge of the world, near the entrance to the Underworld.[3]

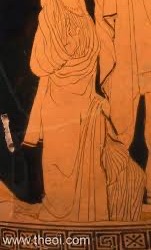

In her iconography, Persephone was represented as a young woman, modestly clad in a robe and wearing either a diadem or a cylindrical crown called a polos on her head.

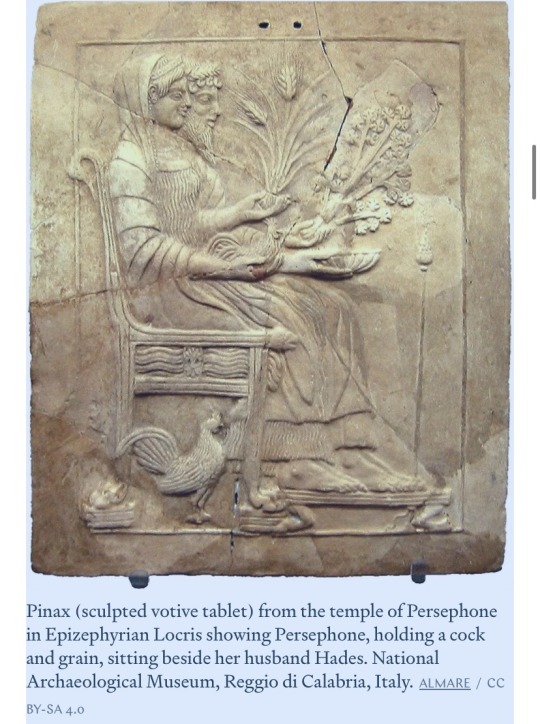

Persephone was characterized by several attributes and symbols, most notably torches, stalks of grain or ears of corn, and scepters. More rarely, she was associated with pomegranates or poppies. Other attributes, such as the rooster, were more localized and tied to the iconography of specific cults.

Locri Pinax Of Persephone And Hades

Several scenes from Persephone’s mythology—especially her abduction by Hades—were popular among ancient artists.[4]

Family

In the standard tradition, Persephone was the daughter of Zeus, the king of the gods, and his sister Demeter, the goddess of agriculture.[5] But there were a handful of rival traditions surrounding Persephone’s parentage, including one in which she was the daughter of Zeus and Styx, an Oceanid who gave her name to one of the rivers of the Underworld.[6] The Orphic version of Persephone, on the other hand, was a daughter of Zeus and Rhea,[7] while an Arcadian version of Persephone called Despoina was the daughter of Demeter and Poseidon.[8]

Persephone krater Antikensammlung Berlin 1984.40

The so-called “Persephone Krater,” an Apulian red-figure volute-krater by the Circle of the Darius Painter (ca. 340 BCE). Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany. BIBI ST. PAULPUBLIC DOMAIN

Persephone was usually regarded as the only child born to Zeus and Demeter, but both gods had children with other consorts. Thus, Persephone’s half-siblings included Demeter’s other children (Arion, Corybas, and Plutus) as well as the numerous children of the promiscuous Zeus (including Apollo, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Heracles, Perseus—and many, many others).

Family Tree

Parents

FATHER

MOTHER

Zeus

Demeter

Siblings

BROTHERS

SISTERS

Arion

Apollo

Corybas

Dionysus

Heracles (Hercules)

Hephaestus

Ares

Hermes

Perseus

Aphrodite

Artemis

Athena

Consorts

HUSBAND

LOVERS

Hades

Adonis

Zeus

Children

DAUGHTERS

SONS

Erinyes (Furies)

Melinoe

Dionysus

Zagreus

Mythology

Abduction by Hades

Persephone was the daughter of Demeter and Zeus. The most detailed account of her myth comes from the second Homeric Hymn, also known as the Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

This poem describes how Persephone was picking flowers in a meadow when she was abducted—with Zeus’ permission[14]—by Hades, the god of the Underworld and the brother of Demeter and Zeus (and thus Persephone’s uncle).[15] Later sources added that it was Aphrodite and Eros who caused Hades to fall in love with Persephone in the first place.[16]

Rape of Prosepina - Bernini 1621-22

The Homeric Hymn then tells of how Demeter, realizing her daughter was missing, began a desperate search. After wandering the entire earth, Demeter finally learned the truth from Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft, who had happened to hear Persephone cry out before she disappeared.

Though Hecate did not know where Persephone had been taken, she told Demeter to seek information from Helios, the charioteer of the sun, who was the only witness to the crime. Sure enough, Helios was able to tell Demeter how Hades had abducted her daughter.[17]

Upon discovering that Hades had Persephone—and that Zeus himself had helped him kidnap her—Demeter was justifiably furious:

But grief yet more terrible and savage came into the heart of Demeter, and thereafter she was so angered with the dark-clouded Son of Cronos that she avoided the gathering of the gods and high Olympus, and went to the towns and rich fields of men, disfiguring her form a long while.[18]

Eventually, Demeter’s wanderings brought her to Eleusis, a town in the region of Attica, just northwest of Athens. Demeter arrived at the palace disguised as an old woman, where she was treated kindly by Queen Metaneira and King Celeus. In return, she nursed their sick child, known as Demophon in most versions of the myth,[19] and tried to make him immortal.

When Demeter’s efforts to impart immortality failed (the boy’s mother, Metaneira, inadvertently interrupted the process when she saw Demeter holding the child in a fire), Demeter commanded the Eleusinians to build her a temple. She then abandoned her functions as the goddess of agriculture, causing grain to stop growing and nearly starving humanity. Demeter’s terrible rage was ended only through the intervention of Zeus, who sent the messenger god Hermes to persuade Hades to return Persephone to Demeter.

Hades told Hermes he would release Persephone—as long as she had not tasted food while in the Underworld. He then tricked Persephone into eating a handful of pomegranate seeds. Because of this, Persephone could not leave Hades for good. In the end, a compromise was reached: Persephone would spend part of the year in the Underworld as Hades’ wife and the other part on Olympus with her mother, Demeter.[20]

Persephone in the Underworld

Persephone was the queen of the Underworld and so ruled over all mortals who had died. Though dreaded, she did sometimes listen to and grant requests. For example, she allowed the prophet Tiresias to keep his reasoning and prophetic abilities even in death.[21]

Persephone also featured in the myths of a handful of heroes and mortals who descended to and returned from the Underworld. According to one source, she was the one who allowed Orpheus to bring his dead wife Eurydice back from the Underworld, provided he did not look back while leading her up (a condition that Orpheus failed to meet).[22]

In another story, Theseus agreed to help Pirithous abduct Persephone from the Underworld, but they were caught and held prisoner. In some versions, Persephone eventually allowed Heracles to bring Theseus and Pirithous back with him when he came to the Underworld to fetch Cerberus (as part of his final labor).[23]

Persephone also featured in some versions of the myth of Alcestis. When Alcestis’ husband Admetus was told that he could put off his death if he found somebody willing to die in his place, Alcestis bravely volunteered. According to some authors, Persephone was so moved by this deed that she allowed Alcetis to return to the land of the living (in the more familiar version, though, Alcestis was brought back by Heracles).[24]

At least one person tried to take advantage of Persephone’s amenable nature. When Sisyphus wanted to escape death, he came up with a clever trick. He told his wife not to bury him; then, when he arrived in the Underworld, he convinced Persephone (though in some versions it was Hades) to let him return to the world of the living to punish his wife for neglecting his funeral.[25]

Lovers and Rivals in Love

The fact that Persephone was married did not prevent her from being imagined as a virginal maiden. There were, however, a handful of myths that challenged this persona.

According to some sources, Persephone vied with Aphrodite for the love of Adonis, an astonishingly handsome mortal man. Eventually, Zeus determined that Adonis would spend part of the year with Aphrodite and part of the year with Persephone.[26]

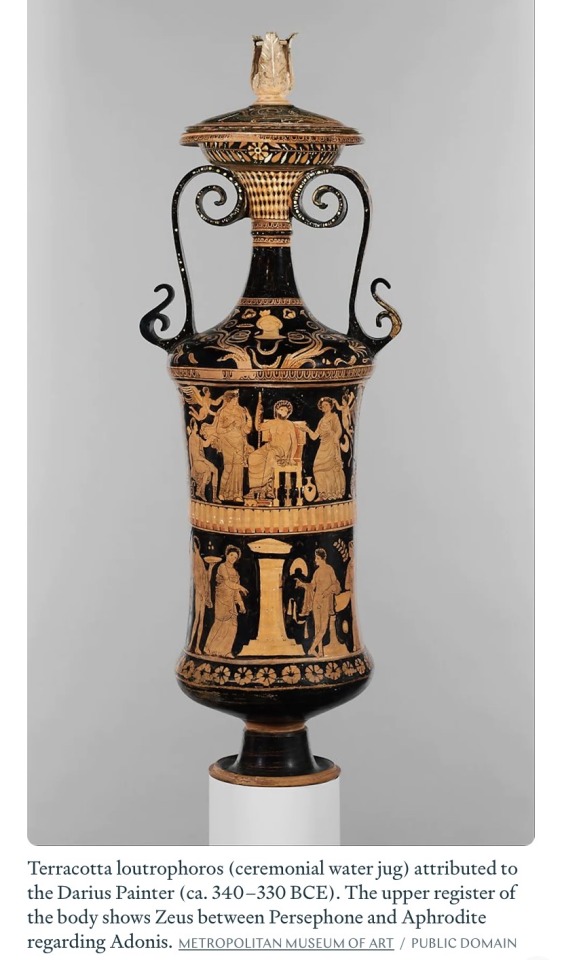

terracotta loutrophoros darius painter 340-330 bce

In another myth, Hades took a nymph named Minthe as his lover. When Persephone found out, she jealously trampled Minthe and turned her into a plant: garden mint.[27]

Orphic Mythology

The Orphics, an ancient Greek religious community that subscribed to distinctive beliefs and practices (called “Orphism,” “Orphic religion,” or the “Orphic Mysteries”), had their own unique mythology of Persephone.

According to several strands of Orphism, Persephone was the daughter of Zeus and his mother, the Titan Rhea (rather than Demeter). She was conceived after Zeus transformed himself into a snake to have sex with Rhea. When Persephone was born, she had a monstrous form, with numerous eyes, an animal’s head, and horns. Terrified, Rhea refused to nurse the child and fled. But Zeus transformed into a snake again and had sex with Persephone, whereupon she conceived the god often called Zagreus or Dionysus Zagreus.[28]

Worship

Temples

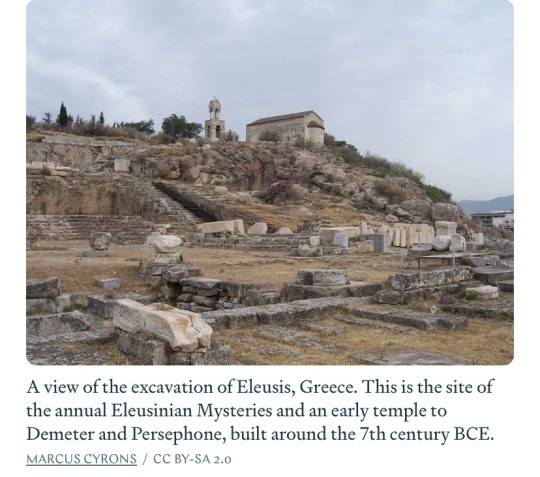

Persephone had temples throughout the Greek world, many of them shared with Demeter. The most notable of these was the Temple of Demeter in Eleusis, a huge, ancient temple likely built during the seventh century BCE. The famous “Eleusinian Mysteries,” religious rites honoring Demeter and Persephone/Kore, were performed there.

excavation-of-temple-to-demeter-persephone-eleusis-greece

Persephone shared many other temples with Demeter, though she also had several temples of her own; the one at Epizephyrian Locris (a Greek colony in southern Italy) is an important example.[29] At other sites, including Teithras in Attica,[30] Acrae in Sicily,[31] and the island of Thasos,[32] Persephone had a separate sanctuary called a Koreion.

Elsewhere, such as Cyzicus,[33] Erythrae,[34] Sparta,[35] Megalopolis in Arcadia,[36] and the Athenian deme of Corydallus,[37] Persephone was worshipped with the cult title Soteira, meaning “Savior.”

Festivals and Rituals

Just as Persephone shared many of her temples with Demeter, she also shared many of her festivals with her.

The most important festival of Persephone and Demeter, the Thesmophoria, was celebrated by married women throughout the ancient Greek world. In Athens, the Thesmophoria lasted three days and involved several rituals, including one in which the rotten remains of a slaughtered pig were dug up and placed on the altars of the goddesses.[38] The Thesmophoria was also celebrated in other parts of Greece, such as the region of Boeotia.[39]

Many of the festivals of Persephone and Demeter were related to the myth of Persephone’s abduction. At Eleusis, worshippers reenacted Demeter’s search for Persephone at night by torchlight. When Persephone was “found,” the ritual ended with celebration, torch throwing, and probably the sounding of a gong.[40] At Megara, similarly, worshippers reenacted Persephone’s abduction by a sacred rock called Anaklēthris, where Demeter was believed to have “called back” (anekalesen in Greek) Persephone when she passed by it during her search.[41]

In Sicily, sometimes said to have been the island from which Hades had abducted the goddess, Persephone was honored in a number of different festivals and rituals. The Korēs Katagōgē (“Descent of Kore”), for example, commemorated Hades taking Persephone (Kore) down to the Underworld.[42] Every year in the Sicilian city of Syracuse, Persephone was honored with the sacrifices of smaller animals and the public drowning of bulls.[43]

Another festival, called the Chthonia, was celebrated annually at Hermione, a city in the Argolid. It honored Demeter in her connection with Persephone, the queen of the Underworld. One part of the festival involved four old women who sacrificed four heifers with sickles.[44]

Other festivals celebrated Persephone in connection with the institution of marriage (rather than with Demeter and agriculture). This seems to have been how Persephone was honored at her temple in Epizephyrian Locris. In some Sicilian cities[45] and in the Locrian colony of Hipponion,[46] there were festivals celebrating Persephone’s wedding.

In Cyzicus, where Persephone was worshipped under the title Soteira, her festival was called either the Soteria,[47] the Pherephattia,[48] or the Koreia.[49] A festival called the Koreia appears to have also been celebrated in Arcadia[50] and Syracuse[51] (though the Syracusean Koreia was likely simply the equivalent of the Thesmophoria).

Persephone, both individually and together with other gods, was also honored through festival and ritual at numerous other sites, including Mantinea, Argos, Patrae, Smyrna, and Acharaca.

Other Worship: Orphism and Curse Tablets

The Orphics, who called Persephone either Despoina[52] or the “Chthonian Queen,”[53] worshipped her primarily in connection with the Underworld. They also associated her with salvation: it was believed that she would grant a blissful afterlife to those who had been properly purified.

Persephone was often invoked on curse tablets under her Underworld title Despoina. Curse tablets were engraved texts that called upon a god, usually a “chthonian” god associated with the Underworld (such as Hecate, Hermes, or Gaia), to punish or harm an enemy, who would generally be named in the text.

Pop Culture

Persephone has continued to captivate the modern imagination as the virginal yet terrifying queen of the Underworld. She has appeared in a handful of modern adaptations of Greek mythology, including Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians franchise, the 1990s TV series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, and even the video game Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey.

Together with Demeter, Persephone is also depicted on the Great Seal of North Carolina, where she is shown in a pastoral setting with the sea in the background.

I hope you enjoyed this blog more to following soon,

Culture Calypso’s Blog 🌹💀🔥🩸🌺🥀

#my blogs#spirituality#history#religion#paganism#greek mythology#roman mythology#persephone#proserpina#goddesses#underworld#deities#SoundCloud

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌾 Today’s blog is on Demeter :: Greek Goddess of Agriculture 🌾 check out my Demeter boxset in my shop @ facebook.com/thehealingcabinmichigan I’ll be doing several Goddess inspired box sets get yours today!

Demeter, the middle daughter of Cronus and Rhea, was the Ancient Greek goddess of grain and agriculture, one of the original Twelve Olympians. Her grief over her daughter Persephone – who has to spend one-third of the year with her husband Hades in the Underworld – is the reason why there is winter; her joy when she gets her back coincides with the fertile spring and summer months. Demeter and Persephone were the central figures of the Eleusinian Mysteries, the most famous secret religious festival in Ancient Greece.

Demeter’s Role

Demeter's Name

Demeter’s name consists of two parts, the second of which (-meter) is almost invariably linked with the meaning “mother,” which conveniently fits with Demeter’s role as a mother-goddess. However, there are still debates over the meaning of the first part (De-), which most scholars associate with “Ge,” i.e., Gaea (making Demeter “Mother Earth”); others, however, prefer to link it with “Deo,” which is a surviving epithet of Demeter and may have been, in an earlier form, the name of one of few grains.

Demeter's Portrayal and Symbolism

Demeter is usually portrayed as a fully-clothed and matronly-looking woman, either enthroned and regally seated or proudly standing with an extended hand. Sometimes she is depicted riding a chariot containing her daughter Persephone, who is almost always in her vicinity. The goddesses – as they were endearingly called – even share the same attributes and symbols: scepter, cornucopia, ears of corn, a sheaf of wheat, torch, and occasionally, a crown of flowers.

Demeter's Epithets

Demeter was known mostly as the Giver of Food and Grain, or “She of the Grain,” for short (Sito). However, since she presided over something as vital as the cycles of plants and seasons, the Ancient Greeks also referred to her as Tesmophoros, or “The Bringer of Laws,” and organized a women-only festival called Tesmophoria to celebrate her as such. Other epithets include: “Green,” “The Giver of Gifts,” “The Bearer of Food,” and “Great Mother.”

Who were Zeus’ Lovers?

How was the World created?

What is the Trojan Horse?

Demeter's Family

Demeter was one of the six children of Cronus and Rhea, their middle daughter, and their second child overall – born after Hestia, but before Hera and her brothers: Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus. Just like all of her siblings, she was swallowed and later, following an intervention by Zeus, regurgitated by her father.

Demeter’s Consorts: Iasion, Poseidon, and Zeus

Demeter didn’t have many partners and was rarely portrayed with a male consort. The mortal Iasion and her brothers Poseidon and Zeus are the most noteworthy – if not the only – exceptions.

Demeter and Iasion

Early in her life, Demeter fell in love with a mortal named Iasion. She seduced him at the marriage of Cadmus and Harmonia and lay with him in a thrice-plowed field. Zeus didn’t think appropriate for such a respected goddess to have a relationship with a mortal, so he struck Iasion with a thunderbolt. But, by then, Demeter was already pregnant with twins: Ploutos and Philomelus, the former the god of wealth, and the latter, the patron of plowing.

Demeter and Poseidon

Next, Demeter’s brother Poseidon forced himself upon her (once transformed into a stallion), and the goddess, once again, became pregnant with two children: Despoena, a nymph, and Arion, a talking horse.

Demeter and Zeus

Finally, Demeter became Zeus’ fourth wife. From their union, Demeter’s most well-known child was born, Persephone.

Demeter and Persephone

The most important myth involving Demeter concerns her daughter Persephone’s abduction by Hades and Demeter’s subsequent wanderings.

The Abduction of Persephone

Hades, the Lord of the Underworld, fell in love with Demeter’s virgin-daughter and decided to take her into marriage. So, one day, as she was gathering flowers with her girlfriends, he lured her aside using a fragrant and inexpressibly beautiful narcissus, and then snatched her up with his chariot, suddenly darting out of a chasm under her feet.

Demeter Finds Out

Inconsolable, Demeter walked the earth far and wide for nine days to find her daughter – but to no avail. And then, on the tenth day, Hecate told her what she had seen and Helios, the All-Seeing God of the Sun, confirmed her story. Demeter wasn’t just brokenhearted anymore. She was now angry as well. And with everybody! Especially with Zeus who, the rumors claimed so, had approved the whole operation and even aided Hades throughout.

The Institution of the Eleusinian Mysteries · Iambe, Demophon, and Metanira

So, Demeter left Mount Olympus and went to grieve her daughter among the mortals, disguised as an old woman. She ended up at the court of King Celeus of Eleusis, where his wife Metanira hired her to be the nurse to her baby son, Demophon. Iambe, the old servant woman of the house, cheered her with her jokes, and Demeter laughed for the first time in many weeks. In gratitude for the kindness, Demeter devised a plan to make Demophon immortal, so she started bathing him in fire each night, thus, burning away his mortality.

However, one day, Metanira witnessed the ritual and, not realizing what was happening, started screaming in panic and alarm. This disturbed Demeter’s strategy, so she revealed herself at once and told Metanira that the only way that the Eleusinians will ever win her kindness back is by building a temple and establishing a festival in her glory.

The Return of Persephone and the Establishment of the Cycles

King Celeus did just that, and Demeter spent a whole year living in her newly built temple, grieving, and, in her grief, neglecting all her duties as a goddess of fertility and agriculture. As a consequence, the earth turned barren, and people started dying out of hunger. After unsuccessfully sending all the gods, one by one, to Demeter with gifts and pleas, Zeus realized that he would have to bring Persephone back to her mother if he didn’t want to see humanity wiped out from the planet.

So, he sent Hermes to Hades, and the divine messenger fetched back Persephone to her mother. However, the gods soon realized that Demeter’s daughter had already eaten one seed of pomegranate in the Underworld, which obliged her to remain in the Underworld. Knowing that Demeter wouldn’t allow such thing to happen, Zeus proposed a compromise: Persephone would spend one-third of the year with Hades and the other two-thirds with Demeter.

The former, the period during which Demeter is grieving, corresponds to the winter months of the year when the earth is infertile and bare; the latter, when she rejoices, overlaps with the abundant months of our springs and summers. The myth likewise explains the growth cycle of the plants. The grain, just like Persephone, must die and be buried under the earth in order to bear much fruit above it.

I hope you enjoyed this blog more to follow soon

Culture Calypso’s Blog 🌾

#my blogs#spirituality#history#religion#paganism#greek mythology#smallbuisnessowner#demeter#agriculture#harvestseason

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's blog is on the pagan holiday Beltane on 5-1-21 BLESSED BELTANE!

🌳👑🌿🔥🙌🍄🌖🌌🌼🦋🌻🌸💐

Beltane

Beltane or Beltain (/ˈbɛl.teɪn/) is the Gaelic May Day festival. Most commonly it is held on 1 May, or about halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Historically, it was widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. In Irish the name for the festival day is Lá Bealtaine ([l̪ˠaː ˈbʲal̪ˠt̪ˠənʲə]), in Scottish Gaelic Là Bealltainn ([l̪ˠaː ˈpjaul̪ˠt̪ɪɲ]) and in Manx Gaelic Laa Boaltinn/Boaldyn. It is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals—along with Samhain, Imbolc and Lughnasadh—and is similar to the Welsh Calan Mai.

Also calledLá Bealtaine (Irish)

Là Bealltainn (Scottish Gaelic)

Laa Boaltinn/Boaldyn (Manx)[1]

Beltaine (French)

Beltain; Beltine; Beltany[2][3]Observed byHistorically: Gaels

Today: Irish people, Scottish people, Manx people, Galician people, Wiccans, and Celtic neopagansTypeCultural

Pagan (Celtic polytheism, Celtic neopaganism, Wicca)SignificanceBeginning of summerCelebrationslighting bonfires, decorating homes with May flowers, making May bushes, visiting holy wells, feastingDate1 May[4]

(or 1 November in the S. Hemisphere)FrequencyannualRelated toMay Day, Calan Mai, Walpurgis Night

Beltane is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature and is associated with important events in Irish mythology. Also known as Cétshamhain ("first of summer"), it marked the beginning of summer and it was when cattle were driven out to the summer pastures. Rituals were performed to protect the cattle, crops and people, and to encourage growth. Special bonfires were kindled, and their flames, smoke and ashes were deemed to have protective powers. The people and their cattle would walk around or between bonfires, and sometimes leap over the flames or embers. All household fires would be doused and then re-lit from the Beltane bonfire. These gatherings would be accompanied by a feast, and some of the food and drink would be offered to the aos sí. Doors, windows, byres and livestock would be decorated with yellow May flowers, perhaps because they evoked fire. In parts of Ireland, people would make a May Bush: typically a thorn bush or branch decorated with flowers, ribbons, bright shells and rushlights. Holy wells were also visited, while Beltane dew was thought to bring beauty and maintain youthfulness. Many of these customs were part of May Day or Midsummer festivals in other parts of Great Britain and Europe.

Beltane celebrations had largely died out by the mid-20th century, although some of its customs continued and in some places it has been revived as a cultural event. Since the late 20th century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Beltane or a related festival as a religious holiday. Neopagans in the Southern Hemisphere celebrate Beltane on or around 1 November.

Historic Beltane customs

Beltane was one of four Gaelic seasonal festivals: Samhain (~1 November), Imbolc (~1 February), Beltane (~1 May), and Lughnasadh (~1 August). Beltane marked the beginning of the pastoral summer season, when livestock were driven out to the summer pastures. Rituals were held at that time to protect them from harm, both natural and supernatural, and this mainly involved the "symbolic use of fire". There were also rituals to protect crops, dairy products and people, and to encourage growth. The aos sí (often referred to as spirits or fairies) were thought to be especially active at Beltane (as at Samhain) and the goal of many Beltane rituals was to appease them. Most scholars see the aos sí as remnants of the pagan gods and nature spirits. Beltane was a "spring time festival of optimism" during which "fertility ritual again was important, perhaps connecting with the waxing power of the sun".

Before the modern era

Beltane (the beginning of summer) and Samhain (the beginning of winter) are thought to have been the most important of the four Gaelic festivals. Sir James George Frazer wrote in The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion that the times of Beltane and Samhain are of little importance to European crop-growers, but of great importance to herdsmen. Thus, he suggests that halving the year at 1 May and 1 November dates from a time when the Celts were mainly a pastoral people, dependent on their herds.

The earliest mention of Beltane is in Old Irish literature from Gaelic Ireland. According to the early medieval texts Sanas Cormaic (written by Cormac mac Cuilennáin) and Tochmarc Emire, Beltane was held on 1 May and marked the beginning of summer. The texts say that, to protect cattle from disease, the druids would make two fires "with great incantations" and drive the cattle between them.

According to 17th-century historian Geoffrey Keating, there was a great gathering at the hill of Uisneach each Beltane in medieval Ireland, where a sacrifice was made to a god named Beil. Keating wrote that two bonfires would be lit in every district of Ireland, and cattle would be driven between them to protect them from disease. There is no reference to such a gathering in the annals, but the medieval Dindsenchas includes a tale of a hero lighting a holy fire on Uisneach that blazed for seven years. Ronald Hutton writes that this may "preserve a tradition of Beltane ceremonies there", but adds "Keating or his source may simply have conflated this legend with the information in Sanas Chormaic to produce a piece of pseudo-history. Nevertheless, excavations at Uisneach in the 20th century found evidence of large fires and charred bones, showing it to have been ritually significant.

Beltane is also mentioned in medieval Scottish literature. An early reference is found in the poem 'Peblis to the Play', contained in the Maitland Manuscripts of 15th- and 16th-century Scots poetry, which describes the celebration in the town of Peebles.

Modern era

From the late 18th century to the mid 20th century, many accounts of Beltane customs were recorded by folklorists and other writers. For example John Jamieson, in his Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language (1808) describes some of the Beltane customs which persisted in the 18th and early 19th centuries in parts of Scotland, which he noted were beginning to die out. In the 19th century, folklorist Alexander Carmichael (1832–1912), collected the Gaellic song Am Beannachadh Bealltain (The Beltane Blessing) in his Carmina Gadelica, which he heard from a crofter in South Uist. The first two verses were sung as follows:

Beannaich, a Thrianailt fhioir nach gann, (Bless, O Threefold true and bountiful,)

Mi fein, mo cheile agus mo chlann, (Myself, my spouse and my children,)

Mo chlann mhaoth's am mathair chaomh 'n an ceann, (My tender children and their beloved mother at their head,)

Air chlar chubhr nan raon, air airidh chaon nam beann, (On the fragrant plain, at the gay mountain sheiling,)

Air chlar chubhr nan raon, air airidh chaon nam beam. (On the fragrant plain, at the gay mountain sheiling.)

Gach ni na m' fhardaich, no ta 'na m' shealbh, (Everything within my dwelling or in my possession,)

Gach buar is barr, gach tan is tealbh, (All kine and crops, all flocks and corn,)

Bho Oidhche Shamhna chon Oidhche Bheallt, (From Hallow Eve to Beltane Eve,)

Piseach maith, agus beannachd mallt, (With goodly progress and gentle blessing,)

Bho mhuir, gu muir, agus bun gach allt, (From sea to sea, and every river mouth,)

Bho thonn gu tonn, agus bonn gach steallt. (From wave to wave, and base of waterfall.)[18]

Bonfires

A Beltane bonfire at Butser Ancient Farm

Bonfires continued to be a key part of the festival in the modern era. All hearth fires and candles would be doused before the bonfire was lit, generally on a mountain or hill. Ronald Hutton writes that "To increase the potency of the holy flames, in Britain at least they were often kindled by the most primitive of all means, of friction between wood." In the 19th century, for example, John Ramsay described Scottish Highlanders kindling a need-fire or force-fire at Beltane. Such a fire was deemed sacred. In the 19th century, the ritual of driving cattle between two fires—as described in Sanas Cormaic almost 1000 years before—was still practised across most of Ireland and in parts of Scotland. Sometimes the cattle would be driven "around" a bonfire or be made to leap over flames or embers. The people themselves would do likewise. In the Isle of Man, people ensured that the smoke blew over them and their cattle. When the bonfire had died down, people would daub themselves with its ashes and sprinkle it over their crops and livestock. Burning torches from the bonfire would be taken home, where they would be carried around the house or boundary of the farmstead and would be used to re-light the hearth. From these rituals, it is clear that the fire was seen as having protective powers. Similar rituals were part of May Day, Midsummer or Easter customs in other parts of the British Isles and mainland Europe. According to Frazer, the fire rituals are a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic. According to one theory, they were meant to mimic the Sun and to "ensure a needful supply of sunshine for men, animals, and plants". According to another, they were meant to symbolically "burn up and destroy all harmful influences".

Food was also cooked at the bonfire and there were rituals involving it. Alexander Carmichael wrote that there was a feast featuring lamb, and that formerly this lamb was sacrificed. In 1769, Thomas Pennant wrote that, in Perthshire, a caudle made from eggs, butter, oatmeal and milk was cooked on the bonfire. Some of the mixture was poured on the ground as a libation. Everyone present would then take an oatmeal cake, called the bannoch Bealltainn or "Beltane bannock". A bit of it was offered to the spirits to protect their livestock (one bit to protect the horses, one bit to protect the sheep, and so forth) and a bit was offered to each of the animals that might harm their livestock (one to the fox, one to the eagle, and so forth). Afterwards, they would drink the caudle.

According to 18th century writers, in parts of Scotland there was another ritual involving the oatmeal cake. The cake would be cut and one of the slices marked with charcoal. The slices would then be put in a bonnet and everyone would take one out while blindfolded. According to one writer, whoever got the marked piece would have to leap through the fire three times. According to another, those present would pretend to throw them into the fire and, for some time afterwards, they would speak of them as if they were dead. This "may embody a memory of actual human sacrifice", or it may have always been symbolic. A similar ritual (i.e. of pretending to burn someone in the fire) was practised at spring and summer bonfire festivals in other parts of Europe.

Flowers and May Bushes

A flowering hawthorn

Yellow flowers such as primrose, rowan, hawthorn, gorse, hazel, and marsh marigold were placed at doorways and windows in 19th century Ireland, Scotland and Mann. Sometimes loose flowers were strewn at the doors and windows and sometimes they were made into bouquets, garlands or crosses and fastened to them. They would also be fastened to cows and equipment for milking and butter making. It is likely that such flowers were used because they evoked fire. Similar May Day customs are found across Europe.

The May Bush and May Bough was popular in parts of Ireland until the late 19th century. This was a small tree or branch—typically hawthorn, rowan, holly or sycamore—decorated with bright flowers, ribbons, painted shells, and so forth. The tree would either be decorated where it stood, or branches would be decorated and placed inside or outside the house. It may also be decorated with candles or rushlights. Sometimes a May Bush would be paraded through the town. In parts of southern Ireland, gold and silver hurling balls known as May Balls would be hung on these May Bushes and handed out to children or given to the winners of a hurling match. In Dublin and Belfast, May Bushes were brought into town from the countryside and decorated by the whole neighbourhood. Each neighbourhood vied for the most handsome tree and, sometimes, residents of one would try to steal the May Bush of another. This led to the May Bush being outlawed in Victorian times. In some places, it was customary to dance around the May Bush, and at the end of the festivities it may be burnt in the bonfire.

Thorn trees were seen as special trees and were associated with the aos sí. The custom of decorating a May Bush or May Tree was found in many parts of Europe. Frazer believes that such customs are a relic of tree worship and writes: "The intention of these customs is to bring home to the village, and to each house, the blessings which the tree-spirit has in its power to bestow."Emyr Estyn Evans suggests that the May Bush custom may have come to Ireland from England, because it seemed to be found in areas with strong English influence and because the Irish saw it as unlucky to damage certain thorn trees. However, "lucky" and "unlucky" trees varied by region, and it has been suggested that Beltane was the only time when cutting thorn trees was allowed. The practice of bedecking a May Bush with flowers, ribbons, garlands and bright shells is found among the Gaelic diaspora, most notably in Newfoundland, and in some Easter traditions on the East Coast of the United States.

Other customs

Holy wells were often visited at Beltane, and at the other Gaelic festivals of Imbolc and Lughnasadh. Visitors to holy wells would pray for health while walking sunwise (moving from east to west) around the well. They would then leave offerings; typically coins or clooties (see clootie well). The first water drawn from a well on Beltane was seen as being especially potent, as was Beltane morning dew. At dawn on Beltane, maidens would roll in the dew or wash their faces with it. It would also be collected in a jar, left in the sunlight, and then filtered. The dew was thought to increase sexual attractiveness, maintain youthfulness, and help with skin ailments.

People also took steps specifically to ward-off or appease the aos sí. Food was left or milk poured at the doorstep or places associated with the aos sí, such as 'fairy trees', as an offering. In Ireland, cattle would be brought to 'fairy forts', where a small amount of their blood would be collected. The owners would then pour it into the earth with prayers for the herd's safety. Sometimes the blood would be left to dry and then be burnt. It was thought that dairy products were especially at risk from harmful spirits. To protect farm produce and encourage fertility, farmers would lead a procession around the boundaries of their farm. They would "carry with them seeds of grain, implements of husbandry, the first well water, and the herb vervain (or rowan as a substitute). The procession generally stopped at the four cardinal points of the compass, beginning in the east, and rituals were performed in each of the four directions".

The festival persisted widely up until the 1950s, and in some places the celebration of Beltane continues today.

As a festival, Beltane had largely died out by the mid-20th century, although some of its customs continued and in some places it has been revived as a cultural event. In Ireland, Beltane fires were common until the mid 20th century, but the custom seems to have lasted to the present day only in County Limerick (especially in Limerick itself) and in Arklow, County Wicklow. However, the custom has been revived in some parts of the country. Some cultural groups have sought to revive the custom at Uisneach and perhaps at the Hill of Tara. The lighting of a community Beltane fire from which each hearth fire is then relit is observed today in some parts of the Gaelic diaspora, though in most of these cases it is a cultural revival rather than an unbroken survival of the ancient tradition. In some areas of Newfoundland, the custom of decorating the May Bush is also still extant. The town of Peebles in the Scottish Borders holds a traditional week-long Beltane Fair every year in June, when a local girl is crowned Beltane Queen on the steps of the parish church. Like other Borders festivals, it incorporates a Common Riding.

Since 1988, a Beltane Fire Festival has been held every year during the night of 30 April on Calton Hill in Edinburgh, Scotland. While inspired by traditional Beltane, this festival is a modern arts and cultural event which incorporates myth and drama from a variety of world cultures and diverse literary sources. Two central figures of the Bel Fire procession and performance are the May Queen and the Green Man.

Neo-Paganism

Beltane and Beltane-based festivals are held by some Neopagans. As there are many kinds of Neopaganism, their Beltane celebrations can be very different despite the shared name. Some try to emulate the historic festival as much as possible. Other Neopagans base their celebrations on many sources, the Gaelic festival being only one of them.

Neopagans usually celebrate Beltane on 30 April – 1 May in the Northern Hemisphere and 31 October – 1 November in the Southern Hemisphere, beginning and ending at sunset. Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the spring equinox and summer solstice (or the full moon nearest this point). In the Northern Hemisphere, this midpoint is when the ecliptic longitude of the Sun reaches 45 degrees.

Celtic Reconstructionist

Celtic Reconstructionists strive to reconstruct the pre-Christian religions of the Celts. Their religious practices are based on research and historical accounts, but may be modified slightly to suit modern life. They avoid modern syncretism and eclecticism (i.e. combining practises from unrelated cultures).

Celtic Reconstructionists usually celebrate Lá Bealtaine when the local hawthorn trees are in bloom. Many observe the traditional bonfire rites, to whatever extent this is feasible where they live. This may involve passing themselves and their pets or livestock between two bonfires, and bringing home a candle lit from the bonfire. If they are unable to make a bonfire or attend a bonfire ceremony, torches or candles may be used instead. They may decorate their homes with a May Bush, branches from blooming thorn trees, or equal-armed rowan crosses. Holy wells may be visited and offerings made to the spirits or deities of the wells. Traditional festival foods may also be prepared.

Wicca

Wiccans use the name Beltane or Beltain for their May Day celebrations. It is one of the yearly Sabbats of the Wheel of the Year, following Ostara and preceding Midsummer. Unlike Celtic Reconstructionism, Wicca is syncretic and melds practices from many different cultures. In general, the Wiccan Beltane is more akin to the Germanic/English May Day festival, both in its significance (focusing on fertility) and its rituals (such as maypole dancing). Some Wiccans enact a ritual union of the May Lord and May Lady.

Name

In Irish, the festival is usually called Lá Bealtaine ('day of Beltane') while the month of May is Mí Bhealtaine ("month of Beltane"). In Scottish Gaelic, the festival is Latha Bealltainn and the month is An Cèitean or a' Mhàigh. Sometimes the older Scottish Gaelic spelling Bealltuinn is used. The word Céitean comes from Cétshamain ('first of summer'), an old alternative name for the festival. The term Latha Buidhe Bealltainn (Scottish) or Lá Buidhe Bealtaine (Irish), 'the bright or yellow day of Beltane', means the first of May. In Ireland it is referred to in a common folk tale as Luan Lae Bealtaine; the first day of the week (Monday/Luan) is added to emphasise the first day of summer.

The name is anglicized as Beltane, Beltain, Beltaine, Beltine and Beltany.

Etymology

Two modern etymologies have been proposed. Beltaine could derive from a Common Celtic *belo-te(p)niâ, meaning 'bright fire'. The element *belo- might be cognate with the English word bale (as in bale-fire) meaning 'white' or 'shining'; compare Old English bǣl, and Lithuanian/Latvian baltas/balts, found in the name of the Baltic; in Slavic languages byelo or beloye also means 'white', as in Беларусь ('White Rus′' or Belarus) or Бе́лое мо́ре ('White Sea').[citation needed] Alternatively, Beltaine might stem from a Common Celtic form reconstructed as *Beltiniyā, which would be cognate with the name of the Lithuanian goddess of death Giltinė, both from an earlier *gʷel-tiōn-, formed with the Proto-Indo-European root *gʷelH- ('suffering, death'). The absence of syncope (Irish sound laws rather predict a **Beltne form) is explained by the popular belief that Beltaine was a compound of the word for 'fire', tene.

In Ó Duinnín's Irish dictionary (1904), Beltane is referred to as Céadamh(ain) which it explains is short for Céad-shamh(ain) meaning 'first (of) summer'. The dictionary also states that Dia Céadamhan is May Day and Mí Céadamhan is the month of May.

There are a number of place names in Ireland containing the word Bealtaine, indicating places where Bealtaine festivities were once held. It is often anglicised as Beltany. There are three Beltanys in County Donegal, including the Beltany stone circle, and two in County Tyrone. In County Armagh there is a place called Tamnaghvelton/Tamhnach Bhealtaine ('the Beltane field'). Lisbalting/Lios Bealtaine ('the Beltane ringfort') is in County Tipperary, while Glasheennabaultina/Glaisín na Bealtaine ('the Beltane stream') is the name of a stream joining the River Galey in County Limerick.

Source: Wikipedia

I hope you've enjoyed this blog more to follow soon,

Blessed be,

Culture Calypso's Blog 🌻🌸💐

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

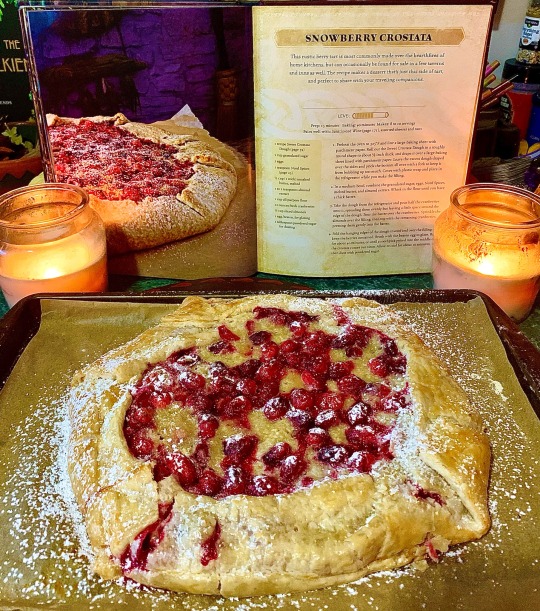

Today’s Recipes Of Skyrim Blog is…

Sunlight Soufflé!

🪺🌅🪺🌅🪺🌅🪺🌅🪺🌅🪺🌅🪺🌅🪺🌅🪺🌅

The gourmet is known for the finicky instructions he provides in Uncommon Taste, but this Breton dish is actually simple enough to make, even if you don’t have a hickory wood spoon. The result is a light, fluffy meal of egg & cheese with an exquisite flavor that can easily be tweaked and embellished to your own tastes.

Prep: 20 minutes

Cooking: 20 minutes

Makes: 4 servings

Pairs well with: fresh fruit, toast, coffee or tea

Ingredients:

4 eggs separated into yolks and whites

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 tablespoons all purpose flour

3/4 cup warm milk

2 1/2 ounces grated Parmesan cheese (about 3/4 cups)

1/2 teaspoon nutmeg

Salt & pepper

Directions:

1. Preheat oven to 375° and lightly butter four 6-inch ramekins.

2. In a medium bowl, beat the egg whites until they form soft peaks then set aside.

3. In a small sauté pan or skillet, melt the butter over medium heat, then stir to make a roux. Cook for a minute or so until all the flour is incorporated, then gradually add in the milk while stirring. Stir for a few more minutes until the whole mixture has thickened. Remove from heat and stir in cheese, nutmeg and a dash of salt & pepper.

4. In a large bowl, beat the egg yolks for 1 minute, until they are pale & creamy. While still beating, gradually add the cheesy roux from the sauté pan & mix throughly. Gently fold in the egg whites, then divide the mixture evenly between the prepared ramekins.

5. Bake for 20-25 minutes, or until puffed & lightly brown on top. Don’t be tempted to open door for a peek! It can cause the soufflés to collapse. Serve immediately and behold, the brilliance of the sun!

I hope you enjoyed this blog this is the last in this series new series soon!

Culture Calypso’s Blog 🌅🪺🌅

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reblogged by Shane Lehane Sheelah take a bow: St Patrick’s wife? Probably not – she was far more important than that

A symbol of Irish womanhood, she deserves to be celebrated again every March 18th

The 16th, 17th (St Patrick’s Day) and 18th March: Erskine Nicol’s painting of the Irish celebration that included Sheelah’s Day. Photograph courtesy of the National Gallery of Ireland

Shane Lehane

Fri Mar 15 2019 - 06:00

For hundreds of years Ireland has had an icon of womanhood and a compelling symbol of all things female, yet few people know her name. The forgotten goddess is none other than Sheelah, once widely celebrated on March 18th, both in Ireland and among the diaspora, yet now all but disappeared. Fáilte Ireland should start to champion her alongside St Patrick: she could be worth a fortune.

Two years ago my research into this disregarded deity resulted in somewhat misleading headlines that said Sheelah was St Patrick's wife. That was not the case, but at least it brought Sheelah and her festival back to our attention. I believe Sheelah – or Sheila, Sheela, Shela, Sheelagh or Síle, depending on the source – has far more to her than the once widely held belief that she was our national saint's other half.

Sheelah's Day fell each year on March 18th, and the usual dispensation to disregard Lenten abstinence on March 17th and wet the shamrock – drink alcohol, in other words – in honour of St Patrick was extended to the following day as well, in honour of his so-called wife. The Freeman's Journal of March 20th, 1841, reported that a woman who appeared in court for drunkenness declared she bought "two small naggin of whiskey… not wishing to break through the old custom of taking a drop on St Sheelah's Day". In contrition to the judge, she vowed: "I here promise that for Patrick's Day or Sheelah's Day, or any other day in the calendar, I'll never stand in your presence again."

Some say Sheelah was 'Patrick's wife', others that she was 'Patrick's mother', while all agree that her 'immortal memory' is to be maintained by potations of whiskey

A painting by Erskine Nicol from 1856, depicting the revelries of such mid-Lenten festivities, is accurately entitled The 16th, 17th (St Patrick’s Day) and 18th March. This elongated name recognises that most Irish festivals, including fairs, pattern days and wakes, took place over three days: the gathering, the feast and the scattering. Sheelah’s Day was the last (but not the least) of the traditional three days of celebration that began on the eve of St Patrick’s Day.

William Hone gives a detailed account of Sheelah’s Day celebrations in Britain in The Every-day Book, from 1827.

“The day after St Patrick’s Day is ‘Sheelah’s day’, or the festival in honour of Sheelah. Its observers are not so anxious to determine who ‘Sheelah’ was, as they are earnest in her celebration. Some say she was ‘Patrick’s wife’, others that she was ‘Patrick’s mother’ while all agree that her ‘immortal memory’ is to be maintained by potations of whiskey. The shamrock worn on St Patrick’s day should be worn also on Sheelah’s day, and on the latter night, be drowned in the last glass. Yet it frequently happens that the shamrock is flooded in the last glass of St Patrick’s day, and another last glass or two or more on the same night, deluges the over-soddened trefoil. This is not ‘quite correct’ but it is endeavoured to be remedied the next morning by the display of fresh shamrock, which is steeped at night in honour of ‘Sheelah’ with equal devotedness.”

This festive time coincides with the vernal equinox, one of the two midpoints of the sun’s annual cycle, in the season of new fertility, when days are poised to outlast nights for the first time since the autumn equinox, the previous September. An emphasis on new life and procreation is manifest in a host of mythological incarnations and folk reflexes at this time of the year. The goddess and holy woman Brigid is celebrated on February 1st; the analogous figure of Gobnait, goddess of fertility and beekeeping, is commemorated on February 11th. These women usher in the new cycle of fertility with ploughing, sowing, the birth of animals, the rising of the sap and the reawakening of nature.

This time of year in the past brought an equal emphasis on human marriage and reproduction, with Shrove Tuesday, immediately before Lent, long being the most popular day in Ireland to be married.

The three-day carnival celebrating Patrick and Sheelah occurs at this key point in the calendar and in the annual cycle of fertility. That Sheelah is firmly situated around the equinox, the seminal pivot of fertility, indicates that she had distinct fertility associations and can be viewed as an equivalent to Brigid and Gobnait.