#beethoven cycle

Text

Continually sitting here like. wow I hope I'm being recognized on this site as one of the top people that talks about pouf + makes art of him, as if I haven't gotten multiple asks thanking me for my service

#he is just. so fun to draw kshfkfjf i have three more ideas lined up!! they're all song inspired lmao#addict love by blue twinkle; then ständchen by schubert and frozen tears from schubert's winterreise song cycle#reading up on it and wanna put the lines of the poem under the art#winterreise is single handedly the heaviest piece of music ive ever experienced#i had to stop it halfway through and just get up and walk away for a bit; it was in the 40s bc of a cold front when i did that so#immersive experience....... anyways schubert is my favorite composer ever so naturally im gonna make pouf art with him in mind#it's about 🤌 the emotional expression and sentimentality of romantic era compositions#which means i could easily do some Beethoven for him.. symphony 7 movement 2 my beloved#kreutzer sonata my beloved!!! but let me actually get to the ones on hand first jshdkd#the goal is to make at least one nice digital piece per month bc i wanna make more art so!! will be constantly thinking of him lmao#(even moreso than normal :p)#hoatm rants

1 note

·

View note

Text

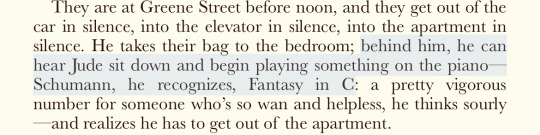

(A Little Life, Part 5, Chapter 2, pg. 602 - Hanya Yanagihara)

Why Schumann?

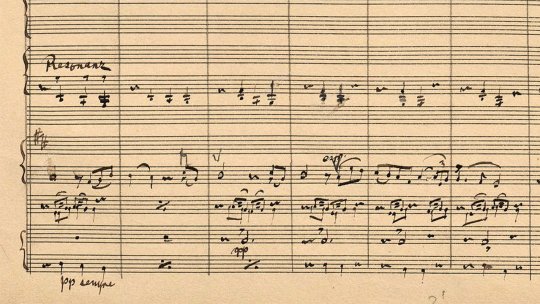

After some digging on the internet, I have learnt that it is not a coincidence that Hanya chose Schumann's Fantasie in C for this moment, and I believe Jude was playing the first movement in this part. Fantasie in C was composed in 1836 as only a piece called Ruines, expressing his distress at being distant from his beloved Clara, and then it became the first movement of Fantasie. The first movement of the work contains a musical quote from Beethoven's song cycle, An die ferne Geliebte (To the distant beloved) as a secret love message:

Take, then, these songs, beloved, which I have sung for you

However, this musical quotation was not acknowledged by Schumann. The movement also was prefaced with a quote from Friedrich Schlegel:

Durch alle Töne tönet / Im bunten Erdentraum / Ein leiser Ton gezogen / Für den, der heimlich lauschet.

Resounding through all the notes / In the earth's colorful dream / There sounds a faint long-drawn note / For the one who listens in secret

During this period, Robert Schumann and Clara Wieck was in separation because Clara's father disapproved of their relationship. Those quotations truly reflected his yearning to Clara, his passionate love to her, and it is more beautiful to learn that they communicated mostly through music and journals because Clara did not communicate verbally well. In a letter sent to Clara in 1838, he wrote:

The first movement may well be the most passionate I have ever composed - a deep lament for you.

They got married in 1840 but their marriage was not through an easy path because Schumann was not mentally well.

(Clara and Robert Schumann around 1850. Corbis, via Getty Images)

In August of 1844, he suffered a severe mental and physical breakdown. He was in pains, he trembled, wept, could not sleep and even became so sick that he could not walk across the room by himself. By February of 1854, Schumann insisted to be committed, as he felt that he had lost control of his mind. On 27th February, he attempted suicide by throwing himself from a bridge into the Rhine River. He was rescued and taken to the hospital later and remained there until his death on 29th July, 1856. During his confinement, Clara was not allowed to visit him (they communicated thanks to Johannes Brahms, a very good friend of the family, especially Clara) and only able to meet him 2 days before his death.

In Clara's journal on 26th February, 1854 (1 days before his attempt suicide), she wrote:

He was so melancholy that I cannot possibly describe it. When I merely touched him, he said, "Ah Clara, I am not worthy of your love." He said that, he to whom I had always looked up with the greatest, deepest reverence.

The resemblance of Jude and Schumann's mental illness may be one of the reason that Hanya chose this piece for Jude to play after he and Willem got home after their big fight. Jude plays the song with the intention to ease his sadness and fear. In this moment, he feels that this might be the end of their relationship, he is afraid that Willem would leave him because now he finally sees how sick he is. The piece Fantasie symbolizes a yearning for love but in this moment, it is a calling for Willem to stay, to understand, to forgive his action, his sickness.

Sources:

Acreman, Thomas. (2017). The Love Story of Clara Schumann. Retrieved from http://www.classichistory.net/archives/clara-schumann

Wilson, Frances. (2019). A Love Letter in Music Schumann's Fantasie in C, Op. 17. Retrieved from https://interlude.hk/love-letter-music-schumanns-fantasie-c-op-17/

#a little life#hanya yanagihara#jude st. francis#willem ragnarsson#robert schumann#clara schumann#literature#classical music#schumann#thank you to people who reblogged this post i don't know how to comment on your reblog post#my a little life revisit diary

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

What one makes music from is still the whole - that is the feeling, thinking, breathing, suffering, human being.

Gustav Mahler

On 26 June 1912, Gustav Mahler's 9th Symphony was given its posthumous premiere in Vienna with Bruno Walter leading the Philharmonic. This profoundly valedictory work - the last Mahler completed before he died - is considered by many Mahler devotees to be his greatest achievement.

Back in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, a superstition developed in the classical music world that prophesied the Ninth would be a composer’s last symphony. Arnold Schoenberg summed it up in an eloquent fashion, stating that “he who wants to go beyond it must pass away. It seems as if something might be imparted to us in the Tenth which we ought not yet to know, for which we are not ready. Those who have written a Ninth stood too close to the hereafter.”

To support this, history gives us Beethoven, Schubert, Dvorák, Bruckner, Mahler, and Vaughan Williams, who either died after completing the ninth (Dvorák waited ten years) or never made it through a tenth. We’ll overlook Shostakovich, who not only completed a ninth but went on to write and publish six more. He was Shostakovich, after all. Even death kept a wary, respectful distance.

Mahler, some say was superstitious about the matter, tried to sneak around it by calling his ninth symphonic-length work, “Das Lied von der Erde,” a song-cycle rather than a symphony. He bravely undertook his Ninth, rife with its intimations of death and the ache of the human condition, and published it (although he never heard it performed). A year later he began working on his Tenth, but, true to the curse, he died before finishing it. Although he’d sketched out the whole symphony, only the first movement, “Adagio,” and a brief third movement, “Purgatorio,” are complete.

I’m not sure I buy it that this was Mahler’s song song as he saw it. I think that’s just a convenient mythos that enveloped around the traumatic death of one of finest composers ever. Far from going gently into a sort of pre-deathly contemplation, Mahler was full of plans, action, and music in the years when he was writing the Ninth Symphony. He was taking up his post at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, writing Das Lied von der Erde, preparing for the premiere of the Eighth Symphony, and writing, but not completing, what would truly be his last symphony, the Tenth. That’s another danger of thinking about that last page of the Ninth Symphony as the end of Mahler’s compositional life. It’s not: for Mahler, and maybe for us, it should be an insight into life - albeit a life transformed after the intensity of what you’ll have been through after listening to any complete performance of his symphony - rather than a leaving of it.

Daniel Barenboim conducts Mahler's 9th Symphony with the Stasoper Berlin orchestra.

#mahlet#gustav mahler#quote#9th symphony#composer#classical music#music#beauty#aesthetics#sound#jinx#death#legacy#daniel barenboim#arts#culture#german#high culture

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Italian pianist Maurizio Pollini, who has died aged 82, was one of the giants of the keyboard in the second half of the 20th century, and yet for all the respect he commanded, his playing was criticised throughout his career for being excessively cool and cerebral. When he took first prize at the 1960 Chopin competition in Warsaw, the chairman of the jury, Artur Rubinstein, declared: “That boy plays better than any of us jurors.” But that success proved to be only the prelude to the first controversial event of his career. He withdrew from the international concert circuit for 18 months to broaden his repertoire and develop other cultural interests. It was not until nearly the end of the decade that his performance schedule achieved a normal rhythm, but his full return in 1968, coinciding with a contract signed with the Deutsche Grammophon (DG) label, launched a series of triumphs on the concert platform and in the recording studio.

Classic recordings of Chopin Etudes, of music by Schumann and Beethoven, and of modernist repertoire such as Pierre Boulez’s Second Sonata consolidated his reputation and, at its best, Pollini’s playing combined expressive but unsentimental intimacy, tonal beauty, textural clarity and a formidable technique. Particularly in his later years, Pollini’s breathless, impatient delivery of Beethoven’s sonatas often seemed to deny their rhetoric, as though he was embarrassed by large romantic gestures or overt emotionalism.

Pollini’s cerebral instincts appeared to deprive him of the ability to live in the moment: romantic subjectivity, it seemed, had constantly to be interrogated.

Pollini was born in Milan. His father, Gino Pollini, was one of Italy’s leading architects of the interwar period; his mother, Renata (nee Melotti), who had studied singing and piano, was the sister of the modernist sculptor Fausto Melotti. Such a background, in which “old works and modern works co-existed together as part of life”, as Pollini later put it, was to have a formative influence on his own approach to art. The discovery of his musical talent led to lessons with Carlo Lonati and Carlo Vidusso (from 1955 at the Milan conservatory) and various competition successes prior to Warsaw. His 1963 London debut, playing Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto with the LSO under Colin Davis, was criticised by the Times as “rushed” and over-impetuous.

Peter Andry, the responsible executive at EMI in the early 1960s, told in his autobiography, Inside the Recording Studio (2008), of the pursuit of the 19-year-old who had just won the prestigious Warsaw competition: “We quickly signed the young Italian, a slender, bespectacled young man with an elongated brow but a very pleasant manner.” One of their first (and only) projects together was a recording of the two sets of Chopin Etudes, Opp 10 and 25. It was not long after this that Pollini appeared to suffer a crisis of confidence. EMI sent him off to study for two years with the pianist Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, but even as his musicality deepened, and reviews were often complimentary, Pollini retreated from the spotlight. He refused to allow the Etudes to be released – though this was in part because DG, shortly to sign Pollini as an exclusive artist, wanted to make their own version. The EMI sets were finally released only in 2011 (on Testament), winning plaudits for their spontaneity and freshness.

It was also in the 60s that music and politics first became intertwined in Pollini’s career. A friendship with a fellow-student, Claudio Abbado, a like-minded leftwing idealist, led them to seek radical ways of bringing classical music to factory workers, including a cycle of concerts at La Scala for employees and students. Another friendship, with the Marxist avant garde composer Luigi Nono, was equally important, resulting in the commission of two pieces for Pollini, including one for piano, voice and tapes, commemorating an assassinated Chilean revolutionary. Pollini’s radical outlook remained with him throughout his career, as did his intellectual approach to art and life. If too often that cerebralism seemed at odds with the heroic or passionate romantic sensibility of the music he played, there were compensations: the visionary gleam in a Chopin miniature; the anticipation of modernism in the ghostly finale of the same composer’s Second Piano Sonata.

Even when declining physical stamina took its toll in later recitals, Pollini commanded admiration of a sort for his continued willingness to pit himself against some of the most demanding works in the repertoire. The breathless impatience of his foreshortened phrases was unsettling, but glimpses of the old magic were still in evidence. The programming of his five-concert series The Pollini Project at the Royal Festival Hall, spread over five months in 2011 – which moved from Bach, through late Beethoven and Schubert to Chopin, Schumann, Liszt and Debussy to modernists such as Stockhausen and Boulez – represented a personal statement about landmarks in the history of piano music.

His interpretation of Boulez’s Second Sonata, notable for its precision and explosive energy, but also for its lyricism and Debussy-influenced pointillism, remains without peer. Stravinsky’s Petrushka likewise drew from him an incomparable muscularity coupled with tonal clarity that was ideally incisive rather than brutal. If Pollini’s playing was controversial, it was so because it explored the dichotomy of intellect and emotion fundamental to music-making.

He is survived by his wife, Marilisa (nee Marzotto), whom he married in 1968, and their son, Daniele.

🔔 Maurizio Pollini, pianist, born 5 January 1942; died 23 March 2024

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

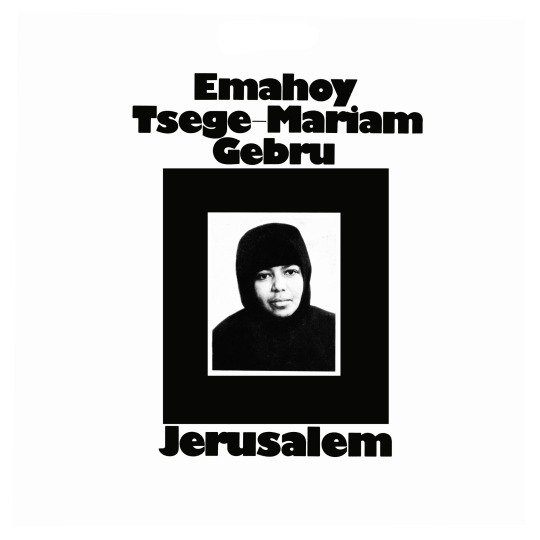

228: Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou // Jerusalem

Jerusalem

Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou

2023, Mississippi Records (Bandcamp)

When she passed away at age 99 in Jerusalem in March of 2023, the Ethiopian nun Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou (alternatively spelled Tsege-Mariam Gebru) had achieved a degree of international fame for a number of piano recordings she had made in the 1960s and ‘70s after they were collected on a 2006 volume of the long-running Ethiopiques series. Much of the attention paid to her story has focused on the circumstances of her extraordinary life, which reached from the court of the Emperor Haile Selassi, to wartime refugee status after Mussolini’s 1936 invasion of her home, to an administrative denial of an opportunity to study at London’s Royal Academy of Music, to taking her vows at nunnery. There are richer synopses already written than I can manage here of both her life and the technical qualities of her remarkable compositions, which utilize a uniquely Ethiopian musical vocabulary but will likely remind Western listeners of Satie or Beethoven.

youtube

Mississippi Records has undertaken a project to reissue her slim body of work (she is known to have composed around 150 songs, though the number she recorded seems to be more like 50), though their compilations tend to hop around chronologically rather than re-releasing complete records. Jerusalem is the latest of these as of this writing and the first to be released since Emahoy’s death, collecting tracks from a 1972 10”, home recordings made in the 1980s, and a single song that appears to date from 1963 (the liner notes are somewhat unclear on this). Like Emahoy’s other releases, these are all solo piano tracks, instrumental save for that 1963 outlier, the tender “Quand la mer furieuse,” which is the first vocal track in her oeuvre. The highlight to my ear is 1972’s “Jerusalem,” a vivid longer piece the artist says is meant to evoke both the love of Ethiopians for that ancient city, and the tragedies of the wars which have ravaged it. Indeed, there is a pensiveness to the song, a sense of an endless cycle in its refrain that nonetheless cycles off into a different motif each time it recurs—signs of hope, perhaps, that despite the recurrences of history, the city’s soil may produce alternative flowers.

youtube

227/365

#Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou#'60s music#'70s music#'80s music#emahoy tsegue-maryam guebrou#tsege-maryam gebru#piano#solo piano#ethiopian music#african music#erik satie#beethoven#modern classical#female musicians#female singer

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

07: Music in nature.

Hi everyone! As someone who loves both music and nature, I’m excited to talk about this week’s prompt! I've found myself captivated by the connections between music and nature in the past, and It's a topic that's as fascinating as it is deep. When we ask, "Where is music in nature? Where is nature in music?" we're really diving into the core of how we interpret and understand both.

Nature is like the ultimate composer in a way. From the rhythmic crash of waves to the gentle rustle of leaves in the wind, it’s almost like a whole symphony out there. And it's not just about inspiration; nature's sounds can actually shape the way we create music. If you listen to the works of Beethoven or Debussy, you can practically feel the influence of the natural world woven into their compositions.

In modern music, the influence of nature can be heard across a wide array of genres and styles. Take, for instance, the Icelandic post-rock band Sigur Rós, whose soundscapes often revolve around the beauty of their homeland's landscapes. In songs like "Sæglópur," layers of shimmering guitars and haunting vocals create a sense of vastness and wonder, making listeners imagine fjords and tundras. Even in electronic music, artists like Björk incorporate elements of nature into their compositions, using field recordings of wind, water, and wildlife to add depth and texture to their songs.

Music, in turn, also becomes a way for us to interpret and express the essence of nature (Hooykaas, 2024). Whether it's through a beautiful orchestral piece or the melody of a piano, music has an incredible ability to evoke the feelings and sensations we experience in the great outdoors (Hooykaas, 2024). It can even be like taking an audio journey through forests, mountains, and oceans without ever leaving your seat. So, when we talk about nature interpretation, we're also talking about how we interpret the sounds and rhythms of the world around us, and how we use music to capture and communicate those interpretations. It's a beautiful cycle of inspiration and expression that speaks to the deep connection between humans and the natural world.

One song that immediately reminds me of a natural landscape is “Landslide” by The Chicks. This is a cover of the song originally written by Stevie Nicks of Fleetwood Mac. With this version by The Chicks being a country song, it’s much different than the rock/metal I usually listen to, but it’s a song that has always stuck with me. Me and my mom like to go for drives out in the country roads/backgrounds, and she always plays this song on those little trips. I find that this song really fits with the rolling hills, vast open fields, and blue skies that I see when we go on those drives. Now that I can drive too I like to go for drives out in the country, and I play this song everytime! It’s a great listen, and really adds to the scenery. The song itself has many lyrics that relate to nature as well.

Overall, as someone who's passionate about both music and nature, I'm amazed by the ways in which these two things are so connected. Whether I'm listening to a symphony or taking a hike in the woods, I can't help but feel like I'm tapping into something bigger than myself, and that's what makes exploring the relationship between music and nature so rewarding!

Hooykaas, A. (2024). Unit 7: Nature interpretation through music. University of Guelph. https://courselink.uoguelph.ca/d2l/le/content/858004/viewContent/3640021/View

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

EVGENY KISSIN l THÉÂTRE DES CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES

Evgeny Kissin est de retour le 28 janvier pour un récital autour de Beethoven, Chopin, Brahms et Prokofiev. Ce concert s’inscrit dans le cycle des 30 ans de fidélité d’Evgeny Kissin sur la prestigieuse scène du Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. Le concert est d’ores et déjà complet mais un nombre très restreint de « places d’écoute » seront mises en vente aux caisses, 1h avant le concert.

Pour les malchanceux qui n’auraient pas de place, Evgeny Kissin revient le 28 mars en musique de chambre avec Matthias Goerne au Théâtre des Champs-Élysées !

(Vidéo : extraits de la répétition générale d’Evgeny Kissin avec l’ONF | Concerto pour piano n°3 de Rachmaninov |©PIAS)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTD in Music History: Historically important pianist, conductor, and arranger Hans von Bulow (1830 - 1894) is born in Germany.

One of the most important concert pianists and conductors active in the 19th century, von Bulow played a critical role in premiering and popularizing major works written by a number of great composers, including Richard Wagner (1813 - 1883), Johannes Brahms (1833 - 1897), and Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840 - 1893).

(von Bulow's connections with Wagner and Brahms are fairly well known, but his connection with Tchaikovsky is somewhat more obscure -- he was the soloist at the world premiere of Tchaikovsky's 1st Piano Concerto in Boston in 1875.)

von Bulow was one of Franz Liszt’s (1811 - 1886) greatest piano students, and he was given the honor of publicly premiering Liszt’s immortal "Sonata in b minor" in Berlin in 1857. The very same year, he also married Liszt's daughter, Cosima (1837 - 1930)… although she later left him for Wagner...

von Bulow was the first pianist in history to publicly perform the complete cycle of Ludwig van Beethoven's (1770 – 1827) thirty-two piano sonatas from memory, and he was also one of the earliest important European concert musicians to tour North America.

Have you ever heard of "The Three B's of Music"?

Composer Peter Cornelius (1824 - 1874) *originally* conceived of that "trinity" as J.S. Bach (1685 – 1750), Beethoven (1770 – 1827), and Hector Berlioz (1803 – 1869)... but von Bulow soon came along and permanently revised the rankings by switching out the Gallic Berlioz for the more suitably Germanic Johannes Brahms (1833 – 1897).

That was no coincidence. After Cosima left him for Wagner, von Bulow became a devoted acolyte of Brahms (who purposely maintained an antipodal relationship with Wagner within the German music world).

PICTURED: A cabinet photograph showing the elderly von Bulow, which he signed and inscribed to a friend in 1891.

Based on the inscription that von Bulow scrawled out beneath his name ("....to the Spielhagen family"), it seems likely that he originally gifted this photo to noted German writer Friedrich Spielhagen (1829 - 1911) or a member of his family.

#classical music#opera#music history#bel canto#composer#classical composer#aria#classical studies#maestro#chest voice#Hans von Bulow#virtuoso pianist#pianist#conductor#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#history of music#historian of music#musician#musicians

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I watched a documentary about composers who died after they composed their 9th symphony (Beethoven, Schubert, Mahler) in Vienna and a professor said that the number 9 represents the ending of a cycle. Children are born after 9 months, the circles of hell are 9, 3 is the perfect number and 9 is a multiple of 3 and I could go on. All of this to say that I find it interesting that my dob has 3-6-9 in it and it made me think what if I wrote a story about someone with a cursed birth date who needs to do something before their cycle ends

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

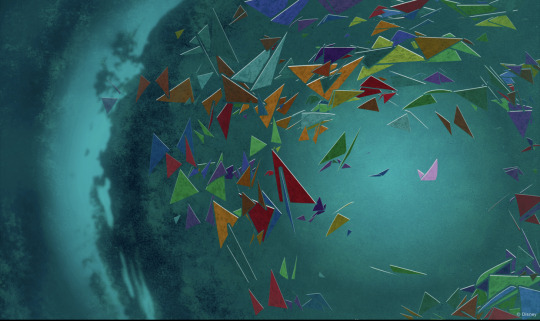

Ok literally one person expressed an inkling of interest in Fantasia 2000, so that’s my sign to let y’all know how amazing the music and animation is.

First, the movie opens with Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5, telling a story of good and evil with butterflies and bats in an abstract style of animation.

[image description: colorful, abstract butterflies all flying in a circle with a blue background]

Steve Martin comes and introduces the concept of Fantasia, then Itzhak Perlman introduces the next song: Pines of Rome, which tells the story of a pod of humpback whales, specifically two whales and their baby.

[image description: a pod of humpback whales soaring through clouds]

Quincy Jones introduces Rhapsody in Blue, which tells the story of four different people who all live in New York City and all have dreams they hope to achieve.

[image description: a bunch of people are crowded in a subway car. Anyone tall enough is holding onto those handlebars that hang from the ceiling. Everyone looks grumpy, and each person is one color with various shades and tints]

Bette Midler introduces Piano Concerto No. 2, which tells the story of the Steadfast Tin Soldier.

[image description: the tin soldier, dressed in a red and white uniform, stands with a ballerina figurine. The ballerina has brown curly hair and a white ballet dress with blue trim. They gaze lovingly into each other’s eyes]

James Earl Jones then introduces Carnival of Animals, which is a story about a flamingo that is shamed by his flock for his love of yo-yos. I’m not making this up.

[image description: a flamingo jumps out of the water, using its feet to play with a yo-yo]

Penn and Teller perform magic tricks as they introduce The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the only animated sequence also used in the original Fantasia. Mickey Mouse is the apprentice of a powerful magician, but when he tries to use magic to take care of his chores, he realizes he’s created more trouble than he can fix.

[image description: Mickey Mouse, dressed in a red robe and a blue wizard hat, holds on to a giant book as he’s trapped in a whirlpool]

James Levine introduces Pomp and Circumstance, although he is interrupted as Mickey Mouse tries to find the star of this story: Donald Duck. Donald Duck helps Noah load animals onto the ark before the big flood, and he and Daisy think they’ve lost each other forever]

[image description: Donald Duck stands in the foreground, satisfied, as many animals walk towards Noah’s ark]

Last but not least, Angela Lansbury introduces the final song, The Firebird Suite, which tells of the cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

[image description: a green spirit/goddess/creature uses her magic and starts to bring a tree to life after winter]

Hopefully the beauty of these images convince y’all to give this movie a try. And maybe you recognize some of the musical pieces!

#fantasia 2000#music#animation#fave#nerd out#nerd-out#beethoven#symphony no. 5#pines of rome#rhapsody in blue#piano concerto no. 2#carnival of animals#the sorcerer's apprentice#pomp and circumstance#the firebird suite#the firebird#art#angela lansbury#steve martin#quincy jones#james earl jones#penn and teller#itzhak perlman#james levine#bette midler#mickey mouse#donald duck#daisy duck#disney

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

i emailed dave hurwitz and asked him to review giannandrea noseda's recently recorded beethoven cycle with national symphony orchestra in DC and he made a video about it! i have never before felt so seen!

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Those who have achieved all their aims probably set them too low.

- Herbert von Karajan

The Soprano Christa Ludwig described him as ‘Le bon Dieu’, while scores of musicians, reviewers and listeners have long regarded him as simply untouchable in the art of conducting. There was, however, much about Herbert von Karajan that was distinctly ungodlike. Ruthlessly ambitious as a young man and grimly autocratic in his later years, his life story is marked by bitter rivalries, feuds and, most notoriously, membership of the Nazi party.

But then, just listen to the results. It’s fascinating to look at the career, the controversy and the achievements of a conductor who still intrigues fans and detractors like no other musician long after his death.

The early career of Herbert von Karajan continues to be swathed in controversy.

Was he an ardent Nazi or an ambitious opportunist? If he was a zealous party member, should we revere his recordings as much as we do? To what extent should any moral accountability weigh against Karajan’s musical achievement? And how much latitude can we extend to people who have artistically given so generously?

Karajan is not alone in occupying this uncomfortable situation during this era. Similar debate surrounds Richard Strauss, Carl Orff and Karl Böhm. Indeed, Wagner also evokes hostility in certain quarters with regard to his racial sentiments.

When Adolf Hitler swept to power in January 1933, the 24-year-old Austrian Herbert von Karajan had already notched up nearly four seasons as an up-and-coming opera conductor in the South German city of Ulm.

Born in Salzburg in 1908 into a prosperous family, he had demonstrated gifts as a pianist and conductor while studying in Vienna. After graduation, his debut orchestral concert with the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra in January 1929, featuring works by R Strauss, Mozart and Tchaikovsky, caused a local sensation and helped to secure him the contract in Ulm.

Karajan seized on the opportunity to learn his trade in Ulm and cut his teeth on much of the operatic repertory from Mozart and Beethoven to Puccini and R . Strauss, including the opera Schwanda der Dudelsacker by the Czech Jewish composer Jaromir Weinberger.

Yet, after the Nazi take-over, Karajan’s future wasn’t assured.

In early 1933, German operatic life was thrown into turmoil as the regime hounded out musicians that were deemed politically and racially unacceptable, and also pursued a protectionist policy to limit employment for non-Germans.

Against this context, Karajan’s decision to join the Nazi Party in Salzburg in April 1933 should be understood as an opportunistic move which was probably designed to safeguard his position at Ulm. Whether it also signalled enthusiasm for Nazi policy is open to speculation, though he no doubt hoped that the strong-arm methods of the Nazis would bring cultural stability to Germany.

Karajan retained his Ulm job for a further season, during which he expanded his repertory to include a praised account of Strauss’s opera Arabella. But in March 1934 he was fired for professional intrigue involving a potential Jewish rival.

He did not have to wait long for a new post. Three months later he was made general music director in Aachen.

Working in a larger theatre enabled Karajan to tackle more ambitious repertory, such as Wagner’s Ring cycle, Verdi’s Otello and Strauss’s Elektra. He also consolidated his reputation in the concert hall, taking charge of Aachen’s annual season of orchestral and choral concerts. One pre-condition for accepting was that he should re-apply for membership of the Nazi Party, his earlier membership in Salzburg having lapsed. This was confirmed in March 1935.

Although in his denazification trial in March 1946 Karajan argued that he had joined the Party to further his career, he could not escape his obligation as Aachen’s general music director to provide the musical background for political occasions.

On 29 June 1935 he took part in a huge open-air orchestral and choral concert that celebrated the NSDAP Party Day and at a similar ceremony four years later he conducted the close from Wagner’s Meistersinger. But his concert programmes seemed untainted by political interference – works by Debussy, Ravel, Kodály and Stravinsky rubbed shoulders with German ones. In 1938 he flouted the law by programming Dukas’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Party authorities must have overlooked that Dukas was of Jewish descent.

Karajan conducts Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony No. 9, performed by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

By 1937 Karajan’s achievements in Aachen were attracting national interest.

In a special edition devoted to Germany’s conducting legacy, the journal Die Musik singled him out as a man who ‘can lead the new organisation of our cultural life in the spirit and direction which National Socialism demands’. Concert engagements in Gothenburg, Vienna, Amsterdam, Brussels and Stockholm helped to spread his name beyond Germany.

Yet for all this, Karajan set his sights even higher by hoping to make an impact in Berlin. This ambition was realised in 1938 with a ‘Strength through Joy’ concert with the Berlin Philharmonic and engagement as conductor at the Berlin State Opera in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in October of the same year.

Karajan may not have anticipated that with his move to Berlin he was stepping into a political cauldron over which he would have little control.

It began with a review of his Tristan which appeared in the Berliner Zeitung. Under the title ‘Karajan the Miracle’, the critic Edwin von der Nüll lavished praise on the performance suggesting that in conducting Wagner’s score from memory the 30-year-old conductor had achieved ‘something our great men in their fifties might envy’.

This was calculated to offend the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler who had previously ruled the roost in the same theatre. Karajan was set up as a pawn in the struggle for control of Berlin’s cultural institutions between Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, a Furtwängler supporter, and Minister of Interior Hermann Goering, the patron of the Berlin State Opera.

In June 1939 Karajan conducted Wagner’s Die Meistersinger at the State Opera without a score. The performance collapsed when the baritone, a drunk Rudolf Bockelmann, made a serious error. Alas Hitler, in the audience, was furious, blaming instead Karajan’s insufficiently Germanic approach to Wagner by conducting from memory.

Further problems arose over his marriage in 1942 to the quarter Jewish Anita Gütermann, technically against the law.

Yet, despite this and the continuing hostility and suspicion of Goebbels and Hitler and Furtwängler’s jealousy, his career prospered during the war. He conducted Bach’s B Minor Mass in Paris for the occupying German soldiers in 1940 and returned to the French capital in 1941 to present his performance of Tristan with the Berlin State Opera.

From 1940 he appeared in Italy and gave concerts in Romania and Hungary. A major achievement was to secure popularity for Orff’s Carmina Burana, a score that had aroused some hostility from the Nazi hierarchy at its first performance in 1937 before Karajan’s performances in Aachen and Berlin during the early 1940s.

Driven by a fanatical love of music and a desire to advance his career, there’s little doubt that Karajan’s involvement with the Nazi regime was opportunistic.

Doubtless though there were also areas of Nazi policy that may well have chimed in with his own views. At the same time falling foul of the regime on occasions, his personal ideology can be best described as a montage of greys; nothing is ever clear-cut and nor perhaps should be our assessment of his work.

#karajan#herbert von karajan#quote#conductor#music#german#nazi germany#nazism#opera#orchestra#classical music#history#arts#culture

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

ANTI CHORAL SYMPHONY??? BLOCKED???

joking but omg I can't believe mahler 2 doesn't do anything for you it reshaped my bones

maybe if i heard it live or studied it i would change my tune but so far at least mahler 2 does very little for me. i tend not to be a huge fan of late romantic works in general, and the overwhelming length/size/expansiveness of these gargantuan symphonies from the likes of mahler tend to strike me as tedious more than majestic. and as for choral symphonies, i think in pretty much every one of them i've heard post-beethoven 9 i've not been terribly impressed by the addition of vocalists. (honestly, one of the things that frustrates me so much ABOUT beethoven 9 is that it really is the one that makes it work, and beethoven's legacy/impact was such that he made so many other composers think they can do the same things he did just as well if not better, which i think succeeds in very rare cases only...but i digress.) in its smallest form (ie a soloist or two added to a movement or two) it just feels like an unnecessary addition to me, and in its largest form (full choir in every movement that is the true focus of the work, a la vaughan williams' sea symphony) i kind of think these works cease to be symphonies at some point. like, apologies to vaughan williams, but that's just a cantata. you can just call it a cantata. it's okay. i know it follows traditional symphonic structure to some extent but it's vague enough and totally dominated by the singing to be a different genre to me. and returning to mahler for a second, a symphony like mahler 2 feels very much like the precursor to something like das lied von der erde, which is more of a song cycle with orchestra (or a "song-symphony" but you can probably guess by now my feelings on that name). mahler 2 of course isn't quite that voice-heavy but it bears strong resemblance to what would come later in his output, i think; i'm still comfortable enough calling it a symphony, but i'm not entirely convinced that the choir ultimately adds to the genre in mahler 2 or in any other late romantic-modern choral symphony. personally, i'm not convinced that we should even cling so fast to the genre label of symphony for all of these works; many of them i think can (and probably should) be classified with a different genre label, whether it's something extant like "cantata" or "song cycle" or something newly coined and retrofitted (it's not like musicians have never fiddled with the naming of past works without the blessing of the composer before). idk, maybe i'm biased as to accept a much narrower definition of "symphony" than most, but the distinction matters to me.

#at any rate mendelssohn 2 should NOT be considered a symphony oh my gd. that one actually gets on my nerves lol#'cantata-symphony' 'choral symphony' THAT'S JUST A CANTATAAAAA JUST SAY CANTATA#MENDELSSOHN WROTE THOSE. IT'S FIIIIINE#okay anyway.#sasha speaks#recapitulation#hope you don't mind this. fucking essay of a response#most of this is personal taste so please don't think i'm like anti-mahler 2 (or its fans) in general#honestly calling myself anti-choral symphony is kind of tongue in cheek to begin with#dvorak is like my one exception to the 'no beloved late romantics' but he doesn't deviate very far from the established symphonic format#so much as he expands from within it like a lot of the earlier post-beethoven romantics did. and that's just more to my taste personally#(dvorak and tchaik actually even though i'm not as keen on some of tchaik's later symphonies)#anyway i'm not so opposed to mahler 2 as to write it off entirely maybe some day i'll hear it live and have my bones rearranged too#but i think if a single piece is Going to be that long it needs to be really truly spectacular from the first listen to be worthwhile#which it just isn't for me...#mvts ii and iii are good tho. mahler is great at inner movements in particular for some reason#sasha answers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a bit of my current jegulus wip, bc maybe posting some of it will convince me to write more!

Sirius and Regulus show up on James’ doorstep in the middle of the night and he knows within a second why they’ve come. The thought doesn’t even fully form in James’ mind before he’s reaching out, pulling them both into a one-armed hug like it’s the most natural thing in the world, like he couldn’t possibly do anything else in this situation. When he finally releases them and takes a step back, he sees Regulus’ face. Sirius had done his best to clean him up, but Regulus still looks like he’s been hit with more than a few nasty curses, and maybe even a punch. James has Regulus’ face in his hands in a second, and Regulus flinches but doesn’t pull away.

“Regulus,” he breathes out, barely a whisper, and the soft look in his eyes pitches Regulus back in time to December.

Walburga and Orion were traveling for the holiday, so Sirius and Regulus were spending the Christmas break at Hogwarts. James, stupid perfect lovely best friend that he was, had stayed as well to spend the holiday with Sirius.

Regulus had spent most of his time holed up reading in stony alcoves around the school, taking advantage of the mostly empty castle where he knew he wouldn’t be disturbed.

“Regulus, it’s snowing!”

Well. Where he wouldn’t have been disturbed if it weren’t for one James Potter.

“Sirius and I are going outside, come with us!” James had said as he came into view. Regulus had briefly wondered how James knew where he was, but then James was literally pulling him up by the hand and he lost the train of thought.

Regulus had protested being dragged outside, he was cold enough as it was, but James had just smiled and cast a warming charm before hooking his fingers around Regulus’ elbow and continuing to pull.

Regulus had stood to the side, watching James and Sirius run and throw snowballs and laugh until they were out of breath. Sirius had started singing, random melodies from their childhood piano lessons bastardized in his brassy tenor. James didn’t recognize any of the tunes, but danced to them anyway, giddy and carefree amidst the falling snow. Sirius cycled through Chopin, Beethoven, Debussy, finally settling on a rather toneless interpretation of Scriabin’s Piano Sonata No. 10, which Regulus recognized instantly. “The Sun’s Kisses,” it was called, colloquially, and something fluttered in his chest as he watched James dance.

James, catching his eye as he spun around, had made his way over and grabbed Regulus by the hand, spinning him until he was so dizzy he fell. James had collapsed next to him on the ground, not quite deliberately touching but a warm and solid presence against the chill of the snow. Regulus’ eyes were brighter than James had maybe ever seen them, cheeks red and laughter falling freely from his lips. Later that evening, alone in his dorm, Regulus had spun around and around, biting down on the smile that kept coming back as he tried to keep his lovesick heart from beating out of his chest.

And now James is here in front of him, stupid and perfect and lovely and holding Regulus’ face in his hands.

“It’s fine, Potter, I’m fine,” Regulus tells him, his voice soft but steady even though James can feel him shaking. James seems to realize what he’s doing and lets go.

#jegulus#starchaser#my writing#regulus black#james potter#marauders#sirius black#fanfic#starchaser fanfic#jegulus fanfic#jegulus fanfiction#jegulus fic#dead gay wizards#james x regulus#marauders fic#harry potter#starchaser fic#regulus x james#james and regulus#the black brothers#wip#writing#writer#fanfiction writer#fanfic writer#fanfic writing#writing fanfic#fic writing#ao3 writer

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

What brings you to tumblr? Also, what's ur favorite song? :3

I wanted to send Armand that video of the furby organ and I figured I'd stay here. It's easier for me to communicate through written words than through talk, so...

As for songs everyone knows the Appassionata holds a special meaning for me and I hold it very close to my heart. It's always been this one, but I have also several songs I cycle through and really love playing. Beethoven is a big part of me, but I also especially love Chopin, and when I want to have fun playing and feel joyful Liszt is a must. I have been playing his Hungarian Rhapsody a lot lately.

As for more popular sounds... Why, I've been especially fond of Kate Bush.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ariel-seagull-wings sent me a message asking which operas I think the Muppets would like best.

So here are my headcanons: the favorite operas of some of the Muppets.

Kermit – I think he would like La Bohéme. It's a simple slice-of-life, not too melodramatic as opera go, it blends comedy and melancholy, and even though it ends sadly, it's still a heartwarming portrayal of a group of friends. He might also enjoy Musetta's diva antics: they would remind him of a certain pig.

Miss Piggy – Wagner's operas, especially the Ring Cycle. They're larger-than-life and full of passion and spectacle, they're great vehicles for prima donnas with big voices, and because of the vocal power they require, they tend to be vehicles for plus-sized divas too.

Gonzo – The Magic Flute. He would like the weirdness of it, and no lady in opera would be more beautiful to him than Papagena. She would remind him of Camilla.

Fozzie Bear – The Barber of Seville. The most famous of all comic operas.

Scooter – The Marriage of Figaro. Its intellectual depth and history as sociopolitical commentary would appeal to his nerdiness, and because he's the Muppet Theatre's "gofer," he'd enjoy an opera where the servants are the heroes.

His sister Skeeter – She would also like Figaro, but for a different reason: because of its proto-feminist themes, with strong-minded women banding together to teach a lesson to a powerful, badly-behaved man.

Rowlf – Fidelio, because he loves Beethoven. He even mentions it in passing in the song "Eight Little Notes." (Quartets, quintets, fugues and sonatas, plus an opera and a few cantatas...")

Sam the Eagle – Porgy and Bess, because it's the great American opera. At least that's what he would say; if he were really as cultured as he pretends to be and actually saw it, he would be appalled by the depiction of drugs and violence.

Rizzo the Rat – Don Giovanni. He would see a kindred spirit in Leporello: a sarcastic lovable coward who gets dragged unwillingly through crazy hijinks and occasionally steals other people's food.

Pepe the King Prawn – Carmen. It's Spanish (in setting, at least) and spicy, like he is.

Robin the Frog – Hansel and Gretel, because it's an opera for kids and about kids, where kids triumph over evil.

Animal – He would also like Hansel and Gretel: all that good food onstage! He'd probably charge up there and start eating the gingerbread house, and wouldn't even stop when he realized it wasn't real gingerbread.

Statler and Waldorf – They would make fun of it all, just like they do everything else.

18 notes

·

View notes