#analysis of fairytales

Text

A class on fairy tales (1)

As you might know (since I have been telling it for quite some times), I had a class at university which was about fairy tales, their history and evolution. But from a literary point of view - I am doing literary studies at university, it was a class of “Literature and Human sciences”, and this year’s topic was fairy tales, or rather “contes” as we call them in France. It was twelve seances, and I decided, why not share the things I learned and noted down here? (The titles of the different parts of this post are actually from me. The original notes are just a non-stop stream, so I broke them down for an easier read)

I) Book lists

The class relied on a main corpus which consisted of the various fairytales we studied - texts published up to the “first modernity” and through which the literary genre of the fairytale established itself. In chronological order they were: The Metamorphoses of Apuleius, Lo cunto de li cunti by Giambattista Basile, Le Piacevoli Notti by Giovan Francesco Straparola, the various fairytales of Charles Perrault, the fairytales of Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, and finally the Kinder-und Hausmärchen of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. There is also a minor mention for the fables of Faerno, not because they played an important historical role like the others, but due to them being used in comparison to Perrault’s fairytales ; there is also a mention of the fairytales of Leprince de Beaumont if I remember well.

After giving us this main corpus, we were given a second bibliography containing the most famous and the most noteworthy theorical tools when it came to fairytales - the key books that served to theorize the genre itself. The teacher who did this class deliberatly gave us a “mixed list”, with works that went in completely opposite directions when it came to fairytale, to better undersant the various differences among “fairytale critics” - said differences making all the vitality of the genre of the fairytale, and of the thoughts on fairytales. Fairytales are a very complex matter.

For example, to list the English-written works we were given, you find, in chronological order: Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment ; Jack David Zipes’ Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion ; Robert Bly’s Iron John: A Book about Men ; Marie-Louise von Franz, Interpretation of Fairy Tales ; Lewis C. Seifert, Fairy Tales, Sexuality and Gender in France (1670-1715) ; and Cristina Bacchilega’s Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies. If you know the French language, there are two books here: Jacques Barchilon’s Le conte merveilleux français de 1690 à 1790 ; and Jean-Michel Adam and Ute Heidmann’s Textualité et intertextualité des contes. We were also given quite a few German works, such as Märchenforschung und Tiefenpsychologie by Wilhelm Laiblin, Nachwort zu Deutsche Volksmärchen von arm und reich, by Waltraud Woeller ; or Märchen, Träume, Schicksale by Otto Graf Wittgenstein. And of course, the bibliography did not forget the most famous theory-tools for fairytales: Vladimir Propp’s Morfologija skazki + Poetika, Vremennik Otdela Slovesnykh Iskusstv ; as well as the famous Classification of Aarne Anti, Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther (the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification, aka the ATU).

By compiling these works together, one will be able to identify the two main “families” that are rivals, if not enemies, in the world of the fairytale criticism. Today it is considered that, roughly, if we simplify things, there are two families of scholars who work and study the fairy tales. One family take back the thesis and the theories of folklorists - they follow the path of those who, starting in the 19th century, put forward the hypothesis that a “folklore” existed, that is to say a “poetry of the people”, an oral and popular literature. On the other side, you have those that consider that fairytales are inscribed in the history of literature, and that like other objects of literature (be it oral or written), they have intertextual relationships with other texts and other forms of stories. So they hold that fairytales are not “pure, spontaneous emanations”. (And given this is a literary class, given by a literary teacher, to literary students, the teacher did admit their bias for the “literary family” and this was the main focus of the class).

Which notably led us to a third bibliography, this time collecting works that massively changed or influenced the fairytale critics - but this time books that exclusively focused on the works of Perrault and Grimm, and here again we find the same divide folklore VS textuality and intertextuality. It is Marc Soriano’s Les contes de Perrault: culture savante et traditions populaires, it is Ernest Tonnelat’s Les Contes des frères Grimm: étude sur la composition et le style du recueil des Kinder-und-Hausmärchen ; it is Jérémie Benoit’s Les Origines mythologiques des contes de Grimm ; it is Wilhelm Solms’ Die Moral von Grimms Märchen ; it is Dominqiue Leborgne-Peyrache’s Vies et métamorphoses des contes de Grimm ; it is Jens E. Sennewald’ Das Buch, das wir sind: zur Poetik der Kinder und-Hausmärchen ; it is Heinz Rölleke’s Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm: eine Einführung. No English book this time, sorry.

II) The Germans were French, and the French Italians

The actual main topic of this class was to consider the “fairytale” in relationship to the notions of “intertextuality” and “rewrites”. Most notably there was an opening at the very end towards modern rewrites of fairytales, such as Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, “Le petit chaperon vert” (Little Green Riding Hood) or “La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes” (The princess who didn’t like princes). But the main subject of the class was to see how the “main corpus” of classic fairytales, the Perrault, the Grimm, the Basile and Straparola fairytales, were actually entirely created out of rewrites. Each text was rewriting, or taking back, or answering previous texts - the history of fairytales is one of constant rewrite and intertextuality.

For example, if we take the most major example, the fairytales of the brothers Grimm. What are the sources of the brothers? We could believe, like most people, that they merely collected their tale. This is what they called, especially in the last edition of their book: they claimed to have collected their tales in regions of Germany. It was the intention of the authors, it was their project, and since it was the will and desire of the author, it must be put first. When somebody does a critical edition of a text, one of the main concerns is to find the way the author intended their text to pass on to posterity. So yes, the brothers Grimm claimed that their tales came from the German countryside, and were manifestations of the German folklore.

But... in truth, if we look at the first editions of their book, if we look at the preface of their first editions, we discover very different indications, indications which were checked and studied by several critics, such as Ernest Tomelas. In truth, one of their biggest sources was... Charles Perrault. While today the concept of the “tales of the little peasant house, told by the fireside” is the most prevalent one, in their first edition the brothers Grimm explained that their sources for these tales were not actually old peasant women, far from it: they were ladies, of a certain social standing, they were young women, born of exiled French families (because they were Protestants, and thus after the revocation of the édit de Nantes in France which allowed a peaceful coexistance of Catholics and Protestants, they had to flee to a country more welcoming of their religion, aka Germany). They were young women of the upper society, girls of the nobility, they were educated, they were quite scholarly - in fact, they worked as tutors/teachers and governess/nursemaids for German children. For children of the German nobility to be exact. And these young French women kept alive the memory of the French literature of the previous century - which included the fairytales of Perrault.

So, through these women born of the French emigration, one of the main sources of the Grimm turns out to be Perrault. And in a similar way, Perrault’s fairytales actually have roots and intertextuality with older tales, Italian fairytales. And from these Italian fairytales we can come back to roots into Antiquity itself - we are talking Apuleius, and Virgil before him, and Homer before him, this whole classical, Latin-Greek literature. This entire genealogy has been forgotten for a long time due to the enormous surge, the enormous hype, the enormous fascination for the study of folklore at the end of the 19th century and throughout all of the 20th.

We talk of “types of fairytales”, if we talk of Vladimir Propp, if we talk of Aarne Thompson, we are speaking of the “morphology of fairytales”, a name which comes from the Russian theorician that is Propp. Most people place the beginning of the “structuralism” movement in the 70s, because it is in 1970 that the works of Propp became well-known in France, but again there is a big discrepancy between what people think and what actually is. It is true that starting with the 70s there was a massive wave, during which Germans, Italians and English scholars worked on Propp’s books, but Propp had written his studies much earlier than that, at the beginning of the 20th century. The first edition of his Morphology of fairytales was released in 1928. While it was reprinted and rewriten several times in Russia, it would have to wait for roughly fifty years before actually reaching Western Europe, where it would become the fundamental block of the “structuralist grammar”. This is quite interesting because... when France (and Western Europe as a whole) adopted structuralism, when they started to read fairytales under a morphological and structuralist angle, they had the feeling and belief, they were convinced that they were doing a “modern” criticism of fairytales, a “new” criticism. But in truth... they were just repeating old theories and conceptions, snatched away from the original socio-historical context in which Propp had created them - aka the Soviet Union and a communist regime. People often forget too quickly that contextualizing the texts isn’t only good for the studied works, we must also contextualize the works of critics and the analysis of scholars. Criticism has its own history, and so unlike the common belief, Propp’s Morphology of fairytales isn’t a text of structuralist theoricians from the 70s. It was a text of the Soviet Union, during the Interwar Period.

So the two main questions of this class are. 1) We will do a double exploration to understand the intertextual relationships between fairytales. And 2) We will wonder about the definition of a “fairytale” (or rather of a “conte” as it is called in French) - if the fairytale is indeed a literary genre, then it must have a definition, key elements. And from this poetical point of view, other questions come forward: how does one analyze a fairytale? What does a fairytale mean?

III) Feuding families

Before going further, we will pause to return to a subject talked about above: the great debate among scholars and critics that lasted for decades now, forming the two branches of the fairytale study. One is the “folklorist” branch, the one that most people actually know without realizing it. When one works on fairytale, one does folklorism without knowing it, because we got used to the idea that fairytale are oral products, popular products, that are present everywhere on Earth, we are used to the concept of the universality of motives and structures of fairytales. In the “folklorist” school of thought, there is an universalism, and not only are fairytales present everywhere, but one can identify a common core for them. It can be a categorization of characters, it can be narrative functions, it can be roles in a story, but there is always a structure or a core. As a result, the work of critics who follow this branch is to collect the greatest number of “versions” of a same tale they can find, and compare them to find the smallest common denominator. From this, they will create or reconstruct the “core fairytale”, the “type” or the “source” from which the various variations come from.

Before jumping onto the other family, we will take a brief time to look at the history of the “folklorist branch” of the critic. (Though, to summarize the main differences, the other family of critics basically claims that we do not actually know the origin of these stories, but what we know are rather the texts of these stories, the written archives or the oral records).

So the first family here (that is called “folklorist” for the sake of simplicity, but it is not an official or true appelation) had been extremely influenced by the works of a famous and talented scholar of the early 20th century: Aarne Antti, a scholar of Elsinki who collected a large number of fairytales and produced out of them a classification, a typology based on this theory that there is an “original fairytale type” that existed at the beginning, and from which variants appeared. His work was then continued by two other scholars: Stith Thompson, and Hans-Jörg Uther. This continuation gave birth to the “Aarne-Thompson” classification, a classification and bibliography of folkloric fairytales from around the world, which is very often used in journals and articles studying fairytales. Through them, the idea of “types” of fairytales and “variants” imposed itself in people’s minds, where each tale corresponds to a numbered category, depending on the subjects treated and the ways the story unfolds (for example an entire category of tale collects the “animal-husbands”. This classification imposed itself on the Western way of thinking at the end of the first third of the 20th century.

The next step in the history of this type of fairytale study was Vladimir Propp. With his Morphology of fairytales, we find the same theory, the same principle of classification: one must collect the fairytales from all around the world, and compare them to find the common denominator. Propp thought Aarne-Thompson’s work was interesting, but he did complain about the way their criteria mixed heterogenous elements, or how the duo doubled criterias that could be unified into one. Propp noted that, by the Aarne-Thompson system, a same tale could have two different numbers - he concluded that one shouldn’t classify tales by their subject or motif. He claimed that dividing the fairytales by “types” was actually impossible, that this whole theory was more of a fiction than an actual reality. So, he proposed an alternate way of doing things, by not relying on the motifs of fairytales: Propp rather relied on their structure. Propp doesn’t deny the existence of fairytales, he doesn’t put in question the categorization of fairytales, or the universality of fairytales, on all that he joins Aarne-Thompson. But what he does is change the typology, basing it on “functions”: for him, the constituve parts of fairytales are “functions”, which exist in limited numbers and follow each other per determined orders (even if they are not all “activated”). He identified 31 functions, that can be grouped into three groups forming the canonical schema of the fairytale according to Propp. These three groups are an initial situation with seven functions, followed by a first sequence going from the misdeed (a bad action, a misfortune, a lack) to its reparation, and finally there is a second sequence which goes from the return of the hero to its reward. From these seven “preparatory functions”, forming the initial situation, Propp identified seven character profiles, defined by their functions in the narrative and not by their unique characteristics. These seven profiles are the Aggressor (the villain), the Donor (or provider), the Auxiliary (or adjuvant), the Princess, the Princess’ Father, the Mandator, the Hero, and the False Hero. This system will be taken back and turned into a system by Greimas, with the notion of “actants”: Greimas will create three divisions, between the subject and the object, between the giver and the gifted, and between the adjuvant and the opposant.

With his work, Vladimir Propp had identified the “structure of the tale”, according to his own work, hence the name of the movement that Propp inspired: structuralism. A structure and a morphology - but Propp did mention in his texts that said morphology could only be applied to fairytales taken from the folklore (that is to say, fairytales collected through oral means), and did not work at all for literary fairytales (such as those of Perrault). And indeed, while this method of study is interesting for folkloric fairytales, it becomes disappointing with literary fairytales - and it works even less for novels. Because, trying to find the smallest denominator between works is actually the opposite of literary criticism, where what is interesting is the difference between various authors. It is interesting to note what is common, indeed, but it is even more interesting to note the singularities and differences. Anyway, the apparition of the structuralist study of fairytales caused a true schism among the field of literary critics, between those that believe all tales must be treated on a same way, with the same tools (such as those of Propp), and those that are not satisfied with this “universalisation” that places everything on the same level.

This second branch is the second family we will be talking about: those that are more interested by the singularity of each tale, than by their common denominators and shared structures. This second branch of analysis is mostly illustrated today by the works of Ute Heidmann, a German/Swiss researcher who published alongside Jean Michel Adam (a specialist of linguistic, stylistic and speech-analysis) a fundamental work in French: Textualité et intertextualité des contes: Perrault, Apulée, La Fontaine, Lhéritier... (Textuality and intertextuality of fairytales). A lot of this class was inspired by Heidmann and Adam’s work, which was released in 2010. Now, this book is actually surrounded by various articles posted before and after, and Ute Heidmann also directed a collective about the intertextuality of the brothers Grimm fairytales. Heidmann did not invent on her own the theories of textuality and intertextuality - she relies on older researches, such as those of the Ernest Tonnelat, who in 1912 published a study of the brothers Grimm fairytales focusing on the first edition of their book and its preface. This was where the Grimm named the sources of their fairytales: girls of the upper class, not at all small peasants, descendants of the protestant (huguenots) noblemen of France who fled to Germany. Tonnelat managed to reconstruct, through these sources, the various element that the Grimm took from Perrault’s fairytales. This work actually weakened the folklorist school of thought, because for the “folklorist critics”, when a similarity is noted between two fairytales, it is a proof of “an universal fairytale type”, an original fairytale that must be reconstructed. But what Tonnelat and other “intertextuality critics” pushed forward was rather the idea that “If the story of the Grimm is similar but not identical to the one of Perrault, it is because they heard a modified version of Perrault’s tale, a version modified either by the Grimms or by the woman that told them the tale, who tried to make the story more or less horrible depending on the situation”. This all fragilized the idea of an “original, source-fairytale”, and encouraged other researchers to dig this way.

For example, the case was taken up by Heinz Rölleke, in 1985: he systematized the study of the sources of the Grimm, especially the sources that tied them to the fairytales of Perrault. Now, all the works of this branch of critics does not try to deny or reject the existence of fairytales all over the world. And it does not forget that all over the world, human people are similar and have the same preoccupations (life, love, death, war, peace). So, of course, there is an universality of the themes, of the motives, of the intentions of the texts. Because they are human texts, so there is an universality of human fiction. But there is here the rejection of a topic, a theory, a question that can actually become VERY dangerous. (For example, in post World War II Germany, all researches about fairytales were forbidden, because during their reign the Nazis had turned the fairytales the Grimm into an abject ideological tool). This other family, vein, branch of critics, rather focuses on the specificity of each writing style, of each rewrite of a fairytale, but also on the various receptions and interpretations of fairytales depending on the context of their writing and the context of their reading. So the idea behind this “intertextuality study” is to study the fairytales like the rest of literature, be it oral or written, and to analyze them with the same philological tools used by history studies, by sociology study, by speech analysis and narrative analysis - all of that to understand what were the conditions of creation, of publication, of reading and spreading of these tales, and how they impacted culture.

#fairy tales#fairytales#fairytale#fairy tale#a class on fairytales#brothers grimm#grimm fairytales#charles perrault#perrault fairytales#history of fairytales#vladimir propp#aarne-thompson classification#aarne-thompson#analysis of fairytales#critics of fairytales#book reference#sources#fairytale research#literary vs folklorist#which actually should be more intertextuality vs folklorist

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utena's hair in her "backstory" looks like Anthy's as the rose bride and the crown is the same as the rose bride's. Also the ring is an "engagement ring" (engagement, bride, you get what I'm trying to say)

The narrative (Akio aka the embodiment of the patriarchy) introduces this idea that Utena was a princess/rose bride and thus she will continue to be one: she is a girl, her only options are to be a princess or a witch, and a rose bride in either way

But just as the backstory is false, the ideas it introduces are false. There is no prince riding on a white horse and never was, the ring wasn't an engagement ring, Utena wasn't a princess/rose bride. Even though society tried to make her one (the backstory, Akio's grooming), she is not.

At Ohtori, all girls are like the rose bride, but there is an outside world. Girls are like the rose bride not because they are predestined to be from birth, but because Akio/Ohtori/the narrative forces them into these roles.

More on the hair style: Anthy's hair is pinned up, made to look sort of like a bob/short hair, to resemble her hair as a young child (shorter) while in the present her hair is long. The illusion of eternity that Ohtori perpetuates (her hair is made to look like it's the same as when she was younger but in reality it's grown)

#rgu#revolutionary girl utena#anthy#utena#anthy himemiya#analysis#utenanthy#my analysis#akio#i noticed this when watching adolescence and anthy was wearing the outfit#theres a lot more to be said when you bring in adolescence#could also tie in we were born in the outside world#utena is wearing very normal very non fairytale fantasy clothes as a child#she was born in the outside world but this world wanted her to forget she was

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about Buddhism as it relates to Madoka Magica, sadly for the first time as I have no personal frame of reference surrounding the religion as a white Canadian.

I think just as much as Madoka criticizes aspects of Christianity, it is also criticizing Buddhism. Namely that the salvation Buddhists seek in the pursuit of nirvana can rob us of our inherent human experience.

“According to Buddhist tradition, the Buddha taught that attachment or clinging causes dukkha (often translated as "suffering"), but that there is a path of development which leads to awakening and full liberation from dukkha”.

Huh. Attachment and clinging causes suffering… where have we seen-

Homura is the fairly straightforward unideal person in Buddhism. Attachment and clinging in Buddhism is called ‘tanha’, and there are three main pillars of it, each of which Homura represents in Rebellion (and the girls all represent with their wishes):

1. Kama-Tanha: Craving for sensory pleasures. These are usually material things and mostly associated with our base desires, like food, sex, wealth even, etc.

2. Bhava-Tanha: Craving to be something, to exist, to unite with an experience. This one is more difficult to understand; but it seems to relate to the idea of wanting to be important and exist in others’ lives and thoughts.

3. Vibha-Tanha: Craving for non-existence. The desire to not experience unpleasant things, and also the desire for self-annihilation (suicide). Homura exemplifies this one strongly.

Buddhists seek to distance themselves from these things in order to seek nirvana, the cessation of desire and thus of suffering. But when you are left without this ‘suffering’, you are also left without the beautiful things in life.

What is a life worth living without desires? What is life for a god who has no attachments? Madoka Magica through Homura, the antithesis to Buddhist ideals, asks this question blatantly in the Concept Movie Trailer.

What is happiness without delicious food and sunbeams (sensory kama pleasures) or connections and existence (bhava)?

Madoka’s existence as a so called enlightened being in heaven (nirvana) goes against what makes us human beings, and her own happiness in turn.

The cessation of desire, a driving force for basic human emotions, does little but make you emotionless and numb. It disconnects you from relationships. What then is to differentiate you from emotionless Incubators?

Attachment and clinging can bring despair to people like Homura in Rebellion. But in the right circumstances, attachment, desire - it brings happiness and love. It is happiness and love. Without suffering, there is no joy. Is an existence without joy worthwhile?

#and then through this I realized the fairytale we may be getting inspo from next is Princess Kaguya#but that’s for another post ;)#madoka magica#pmmm#madoka kaname#homura akemi#Buddhism in Madoka#madoka analysis

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

From @/wilmonism on twitter: "what i love the most about wilmon getting a fairy tale-y ending is that young royals is an anti-fairy tale. the prince loves a boy, the commoner doesn’t become a prince, being part of the monarchy is not sold as the ideal life, yet they get to have their happily ever after"..."it adds to the message of the show, how monarchies oppress those inside and (especially) under it. if you want a happy ending, the last place where you’ll find it is there"

Fairytales sold to us as children about monarchies is what keeps us fascinated with them and their right to exist despite our logic telling us we should have evolved away from them. But there are real people in them, they don't disappear when we turn away from them.

#yr s3 spoilers#young royals#wilmon#young royals analysis#simon eriksson#prince wilhelm#young royals season 3#fairytale endings

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

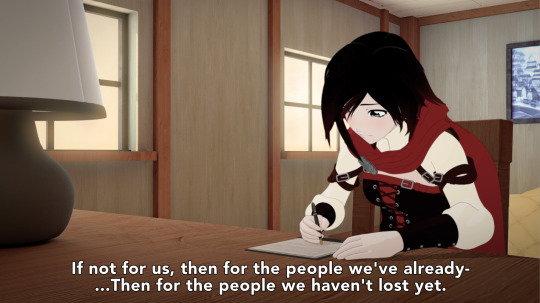

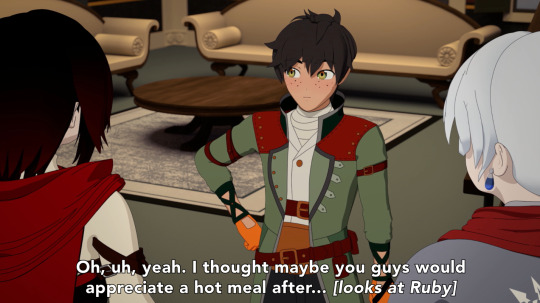

What Inspired the Fairytale: Warrior in the Woods as a Rosegarden Allusion

I've broken down Ruby as Little Red Riding Hood, and Oscar as the Little Prince, now I want to analyze the two of them within a canon fable. The very first story within RWBY: Fairytales of Remnant: The Warrior in the Woods.

For those who are unfamiliar with it, I will summarize, or you can read it in the official free preview of the book here. One disclaimer before I get started: I'm not speaking about the animated adaptation here. Something Oz mentions in his fore/afterward of the book is that fairytales often shift and change depending on who it is that's telling the story. The book itself seems to aim to tell the most objective version as possible, whereas in the episode of FToR, it's very clear Tai's experiences and biases greatly influences the way he tells the story. With that out of the way...

The story is about a boy who lives in a village surrounded by a forest that is said to protect its residents from Grimm. One day, the boy ventures into the wood further than anyone would think to look for him. There he is attacked by a monster, the first he has ever seen... Only to be saved at the last minute by a cloaked warrior carrying a curved weapon. He thanks her and asks for her name, but she tells him to leave and not return. He doesn't listen.

Every year since the day of their first meeting, he ventures further into the wood hoping he will meet his saviour again. And every time, he is proven right when she shows up and saves him at the last minute. Each year, the boy grows older and wiser, training himself how to fight, bringing the woman gifts as thanks for protecting the village alone and without appreciation all these years. Until one day, the village is attacked by Grimm for the first time in ages. On their next planned meeting, the boy - now a man - fights his entire way through the forest to the hut where she lives, and finds it torn apart and empty.

He returns home and tells the villagers her story having taken up the mantle of protecting his people in her place. When asked if he kept going back to see her just because she saved him, he replies (paraphrased): "For that reason, and many more. But I believe she knew the deepest reason of all. I fell in love with her the moment I saw her silver eyes."

Even the summary alone paints a picture very reminiscent of Ruby and Oscar's paired arc throughout the show thus far, but I want to break it down even further. First things first:

The Warrior

She is described as "a fair woman in a flowing (threadbare and tattered) black cape" with a "curved blade" she can spin so quickly it "blurs". Her hair is "almost as dark as the Grimm's, white (ones) standing out as brightly as bone", and in the boy's eyes the first time he sees her, remarks that she is "beautiful and fierce".

We know by the end of the story, as well as one of the Grimm fights, that she has silver eyes as well and she tells the boy at one point that she fights alone because she is alone, since all the people like her were killed by other humans. This lines up well with how Silver Eyed Warriors have been hunted by Salem and her forces for generations.

When we compare this to Ruby when Oscar first meets her, it hits all the same marks. He is captivated by her silver eyes the moment he first meets her:

She is fair skinned with black hair (if you include the books illustrations, with a reddish tint), has silver eyes, and a torn and tattered cloak.

There is a point at which the woman also ties a red ribbon around her weapon's handle to hold it in place, which immediately acts as a tie in to Ruby's colour scheme.

Lastly, the boy meets the warrior for the first time in a "moonlit clearing". And we all know how much moon imagery Ruby has associated with her by now, that I really don't have to go over it again.

The Village Boy

There are no photos or descriptions of him within the text, just that he is a boy when we first meet him and is a man by the end of the story after visiting the woman annually 4-5 times. So he is roughly 14, aka the same age as Oscar, for both their first appearances.

What we do know about the boy, is shown in the objects he carries for himself and the gifts he imparts onto the woman in the woods.

The first is a parcel of clothing. It includes some blouses, leggings, a black skirt, some boots... and a new hooded green cloak. Ruby's cloak is red, but as we know both in show with ships like Bumbleby, and thanks to Eddy's bit of trivia in that Reddit AMA a while ago, that wearing the colours of people you care for is a common sign of affection within Remnant. Within this story, the woman dons a cloak in a green colour (something heavily associated with Oscar Pine), whereas within RWBY in V6, it is Oscar who dons Ruby's colour on his shoulders in his outfit upgrade.

The second is the sword the boy forges for himself before their third meeting. It is described as long and thin which immediately calls to mind The Long Memory.

From there, the next gift: a bag full of food.

"She opened the bag and pulled out parcel after parcel. There was honey cake, a strawberry tart, and sweet biscuits. When she unwrapped a stack of fresh-baked cookies, her expression lightened, and her happiness made him happy."

The first bolded example: strawberries are cited by Monty as Ruby's favourite food, and as we know by Ruby's first meeting with Ozpin (which is important given his connection to Oscar), she's a big fan of cookies too.

Now that all the aesthetics and symbolism are out of the way, I want to compare the structure of the two stories.

Separation and Reunions

The Warrior in the Woods, as well as Ruby and Oscar's arc throughout the show (as well as The Little Prince) are stories of absences.

The boy starts his tale without the woman in his live for many years before he meets her. When they do meet, it is for only a moment within a day until they must wait another full year before seeing each other again. When they do meet, at least the first 3 times, the warrior saves him from Grimm attacks. Then, at the 4th time, he runs into no obstacles and is able to sit and talk with her without incident, only for her to disappear shortly before their 5th visit, leaving him to take up her job of protecting the village.

Ruby spends the first 4 volumes of the show not knowing Oscar, but when they meet he, just like the village boy, is in awe of her silver eyes. From there, she saves him from Grimm twice (I imagine we are holding out on the third where she saves him with her silver eyes for a volume we haven't received yet)...

...and they are faced with constant separations and reunions thereafter.

Oscar goes missing in V6E8 only to be reunited with everyone in V6E9...

2. They are separated for much of V7 due to disagreements and other external circumstance, only to reunite and make up in V7E9...

3. They are then immediately split up again, one going down to Mantle and the other staying in Atlas, only to reunited at the beginning of V8E1 (suspiciously after Oscar stares into a fire much like the boy at the end of the story).

4. It is short lived before they split up on different teams AGAIN, which leads to another reunion in V8E10...

5. Only to - you guess it - be separated one more time when Ruby falls into a void, leaving Oscar to think that she died and take charge as the new leader carrying her responsibilities in her place.

Which follows the structure of the original fairytale - at least in numbers - down to the letter.

Beyond that structure, there is also the matter of what both relationships are built upon: the act of taking care of one another.

In the book, the woman explains that she protects the villagers "because she can, because no one else will, and because some people are good, like the village boy, and that gives her hope".

This heavy responsibility the warrior carries is very reminiscent of Ruby's character arc. A leader who feels she can't be a failure, who can't rely on her friends and teammates to share how much this all weighs on her, someone that lost all her silver eyed family and fears for her own fate because of a trait she had no control over. Even going so far as to try and push people away for fear they will end up hurt because of her. Someone that "remembers all the people she saved, and all the ones she didn't".

This is juxtaposed by a boy who was sheltered and safe, far from the dangers of the world, but set out and joined hers anyway. And when he did, he brought her new clothes, a new weapon, some food, and an ear she could tell her stories to. When he explains his motives, he says:

"You've spent all these years looking after us. I thought maybe it would be nice if someone looked after you for a change. Because that's what I can do. Because no one else will."

Which ties into Oscar's character exactly as well. After his conversation with Ruby in V5 about how scary all of this is, his first thought after saying she's amazing, is to acknowledge how hard this must be on her. And from then on out we see him looking after her to the best of his ability, despite his inexperience, time and time again. Protecting her when she's hurt, standing up for her when their friends fight, and baking her a casserole after she's had a tough day.

All of these things tie into what Ozpin cites as the main message of the fairytale in his notes at the end of its chapter:

It is often used as a cautionary tale, intended to discourage children from wandering too far from home on their own, or from relying too much on others to save them. But the most enduring, and I think the most inspiring, aspect of this story is one which many have taken to heart: If you can help others, it is your responsibility to do so. Whether that means fighting evil singlehandedly, or baking cookies (for kindness can be as rare as silver eyes) is up to the reader to decide for themselves. From each according to their own abilities.

Ruby and Oscar are two characters driven by their responsibilities to do something about all the bad in the world, in whatever ways they are able, before they run out of time. While Ruby's main allusion is Little Red and Oscar's is the Little Prince, I think it's really inspiring to see a canon fairytale within RWBY's own universe that relates to their story so well as this one.

#rwby#ruby rose#oscar pine#rosegarden#rwby rosegarden#rosepine#meta#analysis#rwby meta#rwby analysis#warrior in the woods#fairytales of remnant

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

obsessed with sophomore slump it’s actually so good. dead and gone is a lesbian rivals anthem. fairytale is fucking heartbreaking. the henry rock rocks in worst thing in the world is hope.

and the instrumentals are so good like it’s crazy

#buy them album#if ur not on the patreon you need to hear it im so serious#stream sophomore slump ‼️#i’ll make a whole analysis post about fairytale later bc im obsessed with it#the implications!!!!!!#it can either be super dramatic and teenager-y or it can actually be so sad#dndads#dungeons and daddies#scary marlowe#sophomore slump#butthole ricochet#are we acting like it’s a real band idk#amnesty original

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can’t form a coherent thought because it’s the dead of night but like:

The brothers. The brother Gods. They came from a world of fairy tale simplicity and fairy tale morals. And then they went out into the great beyond and thought themselves so clever and so above their origins that they made their own tale with a more serious tone and twist.

You know how everything has a tailor fit place to belong in the Ever After? What if it was just a vast wilderness and the creations gotta figure that out themselves?

You know how creatures ascend and are reborn? What if they didnt? What if they were gone forever? They gotta pass down that knowledge while their alive or it’s lost forever.

What I’m trying to say so that The Brother Gods created a Gritty Reboot (TM) of the Ever After.

Remnant is in-universe “omg what if we made fairytales grimdark” and the in-universe characters of those fairytales then Disagreed and said “screw it, we are gonna write our own happy ending”

#midnight thoughts#rwby v9 spoilers#rwby analysis#the premise of the show is ‘the in universe creators wanted a gritty fairytale reboot but the characters reject that negativity and forge-#a bright future despite it’#and that’s so metal

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think the problem with the Red Queen is that she’s treated as a real, imminent threat in the game but she is only found in the side quests. Unless you’re Daphne Dreadnaught, you are NOT going to be popular/regarded as such if you’re not the villain of an island

She’s a cool concept, but she should have been part of the (very brief) actual Fairy Tale Island story. Would have made things slightly more interesting

Omg, you're right. She should've been apart of the actual island.

I still have absolutely no idea why Fairytale Island turned out the way it did, with how short it was and the weird extensions to the story that... I guess tried to make up for how short and disappointing the actual island was.

And now I have a vendetta against anything associated with Fairytale Island.

#chad daphne vs virgin red queen#ask#poptropica#poptropica red queen#fairytale island#daphne dreadnaught#spook central#ghost story island#poptropica discussions#poptropica analysis

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alyx wasn't alone.

And she likely didn't leave.

Here me out: The first thing we learn about Alyx is she feels loneliness upon returning from the EverAfter. However, up until this point, she's been described as fairly estranged from everyone. No-one mentions her by name, humans are pretty hated by those who know what humans are.

So, why is she lonely?

Because Alyx didn't fall alone. She fell with someone else.

This person is the likely culprit, seeing as in the beginning we see two dashes across the sky.

Considering a good dose of RWBY fairytales feature Ozma in some capacity, people making stories based on their own adventures isn't too far-fetched.

I'm thinking they both entered, but only one was able to leave. Maybe one person had to stay behind, maybe one of them died. Nonetheless, they wrote the story by erasing the second person or merging their interactions into one person.

How likely is it that Alyx had to give up both her happiest and saddest memory? Doesn't it make more sense if only one of them had to give up their happiest, and the other, their saddest?

We've already seen some revision. The Red King died! Likely killed by a human! We don't know for sure that was Alyx – it wasn't in her story. But how much can we trust her narrative, if there's possibly some heavy revisionism going on?

Listen to the Curious Cat. When Ruby says they're humans, they answer: "You're not nearly as interesting as the others I've met." That's otherS. Plural. Could be referring to Neo, Jaune, or maybe there's a whole village! But equally likely Alyx wasn't prancing around alone.

There's even more evidence in the song, Inside. During the instrumental break, I posit we get a conversation between Alyx and the mysterious companion:

"Okay, I'm almost certain that last time WE went to the left." "So, no way, WE should not turn back, WE need to go in that direction."

That only begs the question: why were they erased from the narrative?

#RWBY#RWBY v9#Rwby Alyx#Ruby Rose#RWBY theory#RWBY analysis#It's likely that the Girl Who Fell Through the World was written by Ozpin#like this guy says “I've lived through my fair share of them” and his lines always tend to have a retroactive alternate meaning#at this point!! YEAH!! he probably DID live through this fairytale#also how many male characters do we know that wear glasses#the silhouette could be a girl or enby or etc#could be Alyx herself? And she just changed to fit the narrativE?#Inside mentions a family estranged so maybe a sibling or cousin#lmao the Red Prince hated green and guess whose whole color is green: yep Ozpin this GUYYYY#maybe the Red Prince didn't untiny them bc Ozpin just untiny'd him and Alyx with Magic however unlikely lol#whatre the odds the dagger was the weapon of destruction?#If it turns out the book was used as the template for Ambrosius or something... hmmm...#ok Im done#geartalk#RWBY spoilers

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I am on the topic of these people that get a lot of criticism for their take on fairytales but still deserve to be kept around due to their influence, I want to briefly evoke Bruno Bettelheim's book "The Uses of Enchantment", known in France as "Psychanalysis of fairytales".

Note that I will not speak of the book itself or the reception of the book in English-speaking countries, but I want to talk about its reception in France and an impact it had on France. Today, numerous elements of the book have been debunked or criticized, coupled with many people misunderstanding the intentions of Bettelheim or misinforming about the context of the book or how it had to be read. As a result, today there is a tendency to crap on this book or laugh about it when we talk about fairytales analysis. However this book had a great importance in France when it came to "save" fairytales.

Before going into the general, as a brief piece of personal experience - which isn't exclusive to me, as others also shared this. This book actually was what got me into the analysis and study of fairytale. Or rather, when I read it as a pre-teen, it made me discover that... fairytales could have depths. Fairytales could have hidden meanings behind being simple children stories. It made me consider how these stories could be taken and reinterpreted as so many allegories and metaphors, it opened my eyes to a certain visceral, psychic, social aspect of these tales, and without this book I certainly would not have been into fairytales as I am today.

Not that this book is the ultimate resource of fairytale analysis - and the entire process of a psychological reading of fairytales is someting that exists but should not be taken into account when trying to explain them (fairytales being the produce of the encounter between literature and folklore). However, this book stayed a door-opening key for me, outdated maybe, overthinking stuff I guess, but that at least allowed me to glimpse into the "great beyond" behind these stories.

And now for my actual point... How Bettelheim's book saved fairytales in France. This is something I learned when studying the life and work of Pierre Gripari - in a book called "Pierre Gripari, un passeur d'écritures" by Inna Saranovska.

When Bettelheim's book reached France in the late 70s, fairytales were in a bad spot when it came to cultural authorities. Already fairytales had been reduced in people's mind to simple, naive children stories only good for making American cartoons (cough cough, Disney). But those of Perrault were still evoked and studied in schools (little schools for little children) because it was part of the heritage of France, of French culture, and the evolution of French literatue...

However what happened in the 70s? The very serious project of just burying fairytales was brought forward. The talks by politics and school authorities were simple: let us stop teaching fairytales to children in school, let's remove fairytales from school libraries, we do not have any use for them anymore, let them be forgotten. On one side, as I said, there was a discredit due to them being seen as silly children story, and thus no real pedagogic or "useful" chilren literature. But on the other side, there were very concrete and serious political business involved - fairytales were seen as antithetic, and opposed, to the principles of the modern Republic of France. Fairytales were seen as backward antiquities that went against what a great democratic nation should be. For example, people really did took issue in the fact that fairytales depicted monarchies, with kings as absolute authorities, and where a happy ending meant to end up prince or princess. For them, it was literaly teaching children to favor and idealize monarchy when they should rather learn about democracies and republics, and while it might seem silly today, it was serious back then and what almost led to the complete erasure of fairytales from school programs.

But then came Bettelheim's book. A book which proved to these folks that fairytales could be of a deep, psychological, social use to children. A book which taught these authorities to see beyond the "silliness" of these children stories or the "backward social message", and which told them how these stories could contain and express the deep fears, the secret desires of children, and help them grow up and deal with familial, social relationships. The book was a best-seller in France, and it completely changed the higher-ups opinion, and convinced tem fairytales should indeed be maintained in school - because fairytales were now "serious" due to being part of the very serious and praised domains of psychology and psychanalysis (which was all the fad and rage in the second half of the 20th century France).

And as such - no matter what you might say about the book's uality today - it can still be thanked for actually "saving" fairytales in France.

#fairytales in france#reception of fairytales#the uses of enchantment#bruno bettelheim#fairytale analysis#history of fairytales

242 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mad and angry at how these two joke side characters try so hard to be heteronormative but they really aren't and that's where most of their misery comes from. not all of it but most of it, like it very much keeps them in the cycle, because they seem desperate to find a happy storybook ending and this is how they think they'll find it, by trying to be like the same characters that found that happiness. its never addressed but also painfully obvious with how much they don't fit in with the other npcs dear god these characters are queer coded to hell i could write an essay (i accidentally did)

its not even like bretta and zote are straight cis characters these two are bi and aro canonically but its more to do with the gender roles they're trying to replicate, and failing. they suck at it. he is not this emotionally stoic resilient lone knight he is in fact continuously fighting his emotional pain and if you give him the right attention he will stay forever. he'll get angry that you saved him or that he needed your help because YOU dont fit in his story. she's not a forgiving accepting loving damsel in distress she can take care of herself great and will also drop you like a hat if she sees even one flaw in you. because then YOU dont fit her story either. they care so much about their stories because they reinforce the identity they think they're supposed to have but they're also so disconnected with themselves BECAUSE of these gender roles that they dont realize it makes them miserable

the biggest cause for this is that they are lonely isolated individuals and dont understand or know enough about real people so they have to go off their storybooks and it only keeps them alone. its like you have to be stubborn about saving them and staying by their side so they can get that chance to change and thats exactly what the knight does. its stubborn as hell it will save them again and again and it will fight their dumbass crushes as many times as it takes to make them realize what they're doing is painful. and bretta gets that chance, she leaves the town that isolated her and goes to find something better, most importantly she gets experience. zote gets to stay alive, which is the best thing you can do for him. because now he might get to face his pain, whereas in death he never gets to overcome it, just escape it

its also very funny that when the game pushes them together in this fake relationship its purposely depicted as completely ridiculous and an obvious parody and you also have the chance to beat it to the ground multiple times. whereas the two more meaningful love stories that you get to help happen are mlm and wlw and completely unapologetic about it this game is GAY

#long post#not normal about them sry sry. they're just your typical everyday knights and maidens lalala#like its been a while since i played hk so i could be off but this is the impression i get from both of them everytime#they're a criticism of traditional fairytale love stories and tbh#im not the best when it comes to gender analysis im like clueless about my own. but i am at least 100% about the fact that#brettas ver of their relationship is a parody. it only exists to make fun of inane fairytale romances#so bretta's character says a lot about gender and zote's says a lot about trauma#both things that exist because they were isolated. love loses#idk but they dont seem like surface level characters to me at all. there's always something to say#on top of them being there to have something to laugh at which i do girl.. i do. they're so silly#but i always felt like there was something that tied bretta and zote together aside from their delusions and i guess its this#btw im tired im gonna rewatch tlou s1 its been a few months also its really good.. apocalyptic media my weakness

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sleeping Beauty (1959)

I don't know if this has been said before, but if Maleficent's blessing+curse combo still holds, the words specifically were "the princess shall indeed grow in grace and beauty, beloved by all who know her." This of course would cause more pain on the whole in the event of her death, everyone who ever met her would be aggrieved.

However, since Aurora/Briar Rose has been rescued from her untimely demise, it may be postulated that Princess Aurora possesses the most powerful tool anyone has ever had - emotional sway over everyone she meets.

She could easily use this to gain favor for her ideas, forge alliances, end (or start) wars, and even bewitch higher beings (sort of implied to be the case in the Maleficent movie).

Disney's Princess Aurora is possibly over-powered, especially for someone with only like 15 lines of dialogue.

#Sleeping Beauty#Princess Aurora#Briar Rose#Disney#magic#Maleficent#fairytales#fairytale#analysis#curse

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are Rhian and Rafal Mistral identical or fraternal? To be honest I see them as identical, I can't see them looking anything else.

He said they were identical in the first book ( Rise SGE ) and then fall sge comes out suddenly they are fraternal and don't look alike?.

He never even described them being fraternal ( unless I am overlooking things )

But I want to know everyone else's opinion on it.

#rise of the school for good and evil#fall of the school for good and evil#rotsge#fotsge#my post#harmonyverendez#my opinions#everyone can comment theirs#what's everyone else opinion on it#soman chainani#fairytale#rhian mistral#rafal mistral#the schoolmasters#my analysis#share and thinking#thinking and sharing#caring snd sharing

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christ, the Descendants fandom post 2017 is annoooooying

#disney descendants#descendants#a bunch of people over analyzing a fairytale from disney channel#i mean I like a good analysis but the amount of fans that just constantly have their noses in the ground inspecting a blade of grass#when you apply real world logic to a fairytale you’re gonna end up with a brain aneurysm#rant#rant post#mal descendants#ben descendants#audrey descendants#evie descendants#uma descendants#i hate it here

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elden Ring and Introduction to the FromSoftware Meta-Narrative

If a rune is a story and a great rune is a great story, then what are the great stories represented by the Great Runes? The answer that I have arrived at: The abstract concept of FromSoftware's various videogame development pipelines. Afterall, the Elden Ring represents a metaphysical concept, so why not an examination of the past, present, and future identity of a company that produces videogames. Major spoilers ahead for Elden Ring, Bloodborne, and Armoured Core 6, and minor spoilers for several other FromSoft games.

Godrick's Great Rune

The Dark Souls (2011-2018) Great Rune seems obvious - Godrick's Great rune. If the 3 ringed shape wasn't the tip-off (corresponding to 3 games) then perhaps that the dragon figure on top of the Banished Knight helmet is the same creature as the Nameless King's mount. Dark Souls Eygon of Carim wears the Morne set and guards a fire keeper named Irena, while in Elden Ring Edgar of Castle Morne in Godrick's territory loses his eyes to frenzy after discovering the death of his daughter Irena.

Godrick himself seems to function as representative of Dark Souls Remastered, in a sense that the repulsive practice of grafting is being equated to the creative dead-end of revisiting old games such as Dark Souls (2011) and pasting on updated graphics and quality of life features while having to work around out-dated code. I think that Godefroy could be seen as a much earlier use of this practice as the difference between original Dark Souls and the Prepare to Die edition (2012) that included improvements + Artorius DLC. And Godwyn's parallel would be Dark Souls 3 (2016). I would thus consider Godwyn and Godrick as brothers in Elden Ring because in the internal logic of FromSoftware there were always planned to be a trilogy of Dark Souls games.

Dark Souls 2 is annoying to explain succinctly partially because it was directed by Naotoshi Zin Yui Taimura (correction: Naotoshi Zin was the supervisor, which was his role on all Dark Souls games as president of the company from 1986-2014) instead of Hidetaka Miyazaki. In short, there are some blurry lines between Dark Souls 2: Scholar of the First Sin and Bloodborne.

Malenia's and Miquella's Great Runes

Malenia herself has an obvious match in Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice (2019) - it is in the Dragon Rot being correlated to Scarlet Rot, the parallels between Malenia's dedication to Miquella and Wolf's dedication to Kuro, and that it's one of the few recent FromSoft games to be released without paid DLC or sequel (which as it happens is common among all empyrean and their game counterparts). Numerous people have commented that Malenia feels like a Sekiro boss to fight - although with the added twist of mechanics like clearing her poise break that allow her to "cheat" compared to the bosses of that game.

However, the exact nature of Malenia's Great Rune is more nebulous - probably could be a stand-in for multiple Japanese-style combat games in the catalogue including Shadow Assault: Tenchu (2008) and Otogi: Myth of Demons (2002). Certainly, it has been confirmed by FromSoftware representatives that Sekiro was internally considered a Tenchu game for some time before release, as discussed in the aptly titled 2018 GameSpot article "Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice Originally Started As A Tenchu Game".

Miquella may or may not have a Great Rune. If he does, it would correspond to games in a similar spirit to Déraciné (2018), the game which Miquella most likely represents. A much smaller game, the idea of which originated in the wake of Bloodborne's release at around the same time that the idea for Sekiro began to form - twin ideas. The game Kuon (2004) also seems to have served some inspiration for the Haligtree, as there is a side-story told about silkworms and a central Mulberry Tree in that game.

Radahn's Great Rune

Radahn's Rune represents the Armored Core franchise - or perhaps the broader idea of mech combat games - while he is himself a personification of Armoured Core 6: The Fires of Rubicon (2023). The opening part of his boss fight is an artillery bombardment, similar to the long range weapon capabilities of the AC units. The central motifs of AC6 are "fire" and "coral" - and the general theme of Caelid is using fire to control the rot that has eaten Radahn's mind and which manifests in the landscape as growths resembling coral reef.

A major part of Radahn's character is that he idolized Godfrey, who is himself embodying AC4 (2006)/4A (2008). The name "Loux" means "Lynx" - and in a departure from the Ravens of earlier titles AC4 introduces the Lynx units. It also simply makes sense that the progenitor of the Golden Lineage - who I previously correlated to Dark Souls - would be represented in the first game that Miyazaki directed.

And I can see the objection that this doesn't make sense because we know that Radahn must have been born before Malenia/Miquella, so how can he represent a game that came after? Simply: it's not about when the game idea was executed, but about when the concept was first proposed. FromSoftware probably knew that they would eventually return to Armoured Core at about the time they wrapped on AC5V.

Morgott and Mohg's Great Runes

Now that some boundary conditions have been set it is easier to speculate on the nature of Morgott and Mohg - AC5 (2012) and AC5V (2013), respectively. Points of comparison: 1) They are of the Golden Lineage as they preceded from AC4A represented by Godfrey, 2) They are omens that any game without Miyazaki attached will be perceived poorly in hindsight (as he did not direct either game), 3) The AC games were at the time FromSoftware's most well known and active franchise before being overshadowed by souls games - those touched by the Crucible were once considered divine and only later fell into disfavor.

But as I already mentioned, with speculation that Radahn holds the Armoured Core Great Rune Morgott and Mohg must have claimed some other stories. This also aids in understanding how they can exist as multiple copies - there is the version of them before and after claiming Great Runes that do not match their original natures. Morgott is the easiest to figure out - it's the Elden Ring (2022) Rune. There is one Great Rune in the entire game that is mandatory to beating the game, and it is the one held by Morgott. Perhaps this raises a question of how can the Elden Ring have a single Great Rune dedicated to itself, but as I have been attempting to describe - all FromSoftware games should be treated as a single body of work looking backwards from Elden Ring. The initial concept of an "Elden Ring" stretches back at least as far as Eternal Ring (2000), and Morgott's rune is described as an "anchor ring that houses the base" so it does have a central importance.

And there's a relatively straightforward answer to which game would be considered a twin to Elden Ring - Demon's Souls (2009). The leitmotif in the menu music for Elden Ring has been identified as a more triumphant version of the Demon's Souls menu music. The core themes of Elden Ring are also much concerned with philosophies of identity in much the same way that Demon's Souls explores the definition of the self as an entity that thinks (look up "Philosophical Analysis of Demon's Souls" by The Gemsbok on Youtube for more on this). And Elden Ring serves as something of a bookend to Demon's Souls - both games are divided into 6 sections via 6 stone structures (the Archstones of Demon's Souls and the Divine Towers of Elden Ring). The 6th Archstone of Demon's Souls is broken, but what lies beyond is a snowy landscape. Elden Ring finally provides access to that snowy landscape in the Forbidden Lands, which is again only available after defeating Morgott - and with the Great Rune being activated at the tower closest to this area.

But there are independent reasons why Mohg's Great Rune should be the one that encompasses Demon's Souls. The Demon's Souls franchise potential has been irreversibly corrupted by the recent remake. The philosophy is still generally intact - that is portrayed through text. But critical aspects of art design have been altered beyond recognition - mostly of interest to me is the portrayal of the Yellow Monk and the Fool's Idol and the area of Latria in general. Mohg himself has this in the design of his robes and trident which steal the motifs of the helix and the black flame but corrupt them in ways that read almost as gibberish compared to their deliberate uses elsewhere.

The four-armed doll of the Fool's Idol hints at who the original owner of this rune might have been - Ranni's mentor Renna. And through embodying the witch Renna, it may be that ownership of this rune was transfered to Ranni before she chose to discard it. Demon's Souls did generally fit the previously established criteria of Empyrean game (no sequels or DLC), but the potential for future games is lost now as creating a sequel to the original would alienate people confused by the aesthetic corruption of the remake. There is also a rabbithole here for what all this Great Rune encompasses because Demon's Souls itself did not spring out of nowhere - it is of a similar approach to game design that was previously last seen in Shadow Tower Abyss (2003) and Kingsfield IV (2001).

The Great Rune of the Unborn

The Great Rune of the Unborn is a difficult one to pin down through this method of unpacking the Great Runes as much as any other. It seems possible that Miquella wanted this Great Rune and thought that it could be obtained by arranging his own rebirth. It is also one of two stories that must be obtained for Ranni's Age of Stars to be possible (the other being Radahn's story) - indicating that it represents something that did not exist at the time of Elden Ring's release. Running low on demi-gods, perhaps this is best understood as Melina's Great Rune. It is implied through Melina's abilities to channel Marika's echoes and through her descriptor in the code "MarikaofDaughter" that she is an offspring of Marika. Contradictory to the other demi-gods who can typically be matched to FromSoftware games, Melina's bodiless status seems to indicate that she never has been and her burning at the Forge of Giants is acknowledgement that she never will be. A comparison can be drawn between Melina and the disembodied Ayre - voice of the Coral in AC6. The unrealized potential of the Great Rune of the Unborn seems a good match to Melina.

Rykard's Great Rune

So, by process of elimination there is one rune left and it is Rykard's Great Rune. Fitting that the one game candidate remaining is Bloodborne (2015). An article titled "How the Spirit of Bloodborne Lives on in Elden Ring" (posted on VG247 by Alan Wen) goes over the ways that Volcano Manor evokes Bloodborne. The Manor sits on top of a hidden town of gothic architecture similar to Yharnam being stacked on top Old Yharnam, the Ghiza's Wheel weapon found in the manor has a clear design lineage to the whirligig saw from Bloodborne, the Iron Virgin at Raya Lucaria transports the player to a secondary location similar to Bloodborne's Kidnappers. But to me, the most clear connection is the finding of the Serpent's Amnion and Rya's dismay of being born of a hideous ritual. This seems a form of call-back or iteration to the ending of Bloodborne that involves consuming four 3rds of umbilical cord and being reborn as a Great One - a repellent little squid-slug thing.

#FromSoftware#elden ring#bloodborne#armoured core#media analysis#fromsoftware meta-narrative#Naotoshi Zin's absurd astrology tarot moon logic fairytale deconstructive approach to game development#The man is practically a ghost but I assume he is responsible as founder and former president#Miyazaki takes over and it's like what if we draw on real psychology and history and transition out of pseudoscience#Or Zin specifically hired Miyazaki for his social science degree perspective with the goal of doing this - who knows#I woke up and chose to write all of this instead of anything else that I could have done with my afternoon#Might as well post it

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

(dimension 20 neverafter episode 4 spoilers)

Big bad wolf as a grim reaper/harbinger of death figure as opposed to being a straightforward antagonist... I think this is a very interesting framing particularly as they keep the title "big bad wolf" in his title card, so it's like... Idk the juxtaposition of the perception of him versus the true nature of him as an entity? If I am reading it right and the wolf is more supposed to represent death than "evil" per se (whatever value the concept of "evil" has in this setting) then I think the way Brennan plays him is pitch perfect, not a "good" force or a "bad" force so much as he is an inevitability

Speaking of complicating that simplistic moral framework of the "big bad wolf" - ylfa's grandma transforming into a wolf, so the grandma and the wolf are perhaps not different and opposed but two sides of the same coin (thought it was really interesting the way Brennan talked about it, like the grandma is not necessarily a disguise bc she is also the wolf but it's not necessarily so simple as they are the same either - maybe they are the same, or maybe part of grandma ate part of the wolf, or maybe parts of them exist in the other, etc. Etc.). But maybe we should put aside the exact details about the relation b/w grandma and the wolf, like I'm not sure that those matter so much as, like, the idea that that duality exists and is real. grandma's line of you can't have the oatmeal raisin cookies without walking through the woods to get there; ylfa is both the little girl and the wolf, and both the potential for the heroic and the monstrous live inside her... I am Thinking

#neverafter spoilers#d20 spoilers#dimension 20#d20#neverafter#sarah.txt#this is more or less me just stream of consciousness'ing some thoughts#maybe tomorrow I'll have some more coherent analysis (i probably won't lol)#actually i think brennan is doing a LOT of interesting things with morality/good v bad with everyone#esp in the context of fairytales which traditionally has a pretty well defined sense of good v wrong#but ylfa does blorbo my braincells so her vignette is what is currently at the forefront of my mind#can i also say i fucking love that zac is playing a trickster cat god it's everything i could have ever wanted <33#d20 meta#story meta

101 notes

·

View notes