#Old Age | Alternative

Text

The U-Bend of Life! Why, Beyond Middle Age, People Get Happier As They Get Older

— December 16th 2010 | Wednesday 16th August 2023 | Christmas Specials | Age and happiness

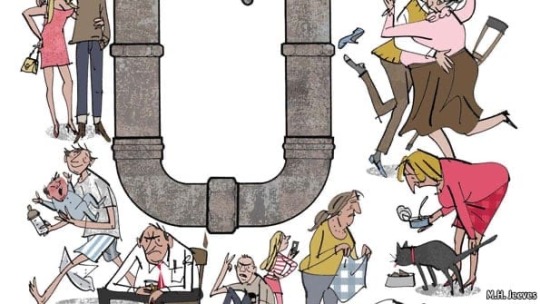

ASK people how they feel about getting older, and they will probably reply in the same vein as Maurice Chevalier: “Old age isn't so bad when you consider the alternative.” Stiffening joints, weakening muscles, fading eyesight and the clouding of memory, coupled with the modern world's careless contempt for the old, seem a fearful prospect—better than death, perhaps, but not much. Yet mankind is wrong to dread ageing. Life is not a long slow decline from sunlit uplands towards the valley of death. It is, rather, a U-bend.

When people start out on adult life, they are, on average, pretty cheerful. Things go downhill from youth to middle age until they reach a nadir commonly known as the mid-life crisis. So far, so familiar. The surprising part happens after that. Although as people move towards old age they lose things they treasure—vitality, mental sharpness and looks—they also gain what people spend their lives pursuing: happiness.

This curious finding has emerged from a new branch of economics that seeks a more satisfactory measure than money of human well-being. Conventional economics uses money as a proxy for utility—the dismal way in which the discipline talks about happiness. But some economists, unconvinced that there is a direct relationship between money and well-being, have decided to go to the nub of the matter and measure happiness itself.

These ideas have penetrated the policy arena, starting in Bhutan, where the concept of Gross National Happiness shapes the planning process. All new policies have to have a GNH assessment, similar to the environmental-impact assessment common in other countries. In 2008 France's president, Nicolas Sarkozy, asked two Nobel-prize-winning economists, Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz, to come up with a broader measure of national contentedness than GDP. Then last month, in a touchy-feely gesture not typical of Britain, David Cameron announced that the British government would start collecting figures on well-being.

There are already a lot of data on the subject collected by, for instance, America's General Social Survey, Eurobarometer and Gallup. Surveys ask two main sorts of question. One concerns people's assessment of their lives, and the other how they feel at any particular time. The first goes along the lines of: thinking about your life as a whole, how do you feel? The second is something like: yesterday, did you feel happy/contented/angry/anxious? The first sort of question is said to measure global well-being, and the second hedonic or emotional well-being. They do not always elicit the same response: having children, for instance, tends to make people feel better about their life as a whole, but also increases the chance that they felt angry or anxious yesterday.

Statisticians trawl through the vast quantities of data these surveys produce rather as miners panning for gold. They are trying to find the answer to the perennial question: what makes people happy?

Four main factors, it seems: gender, personality, external circumstances and age. Women, by and large, are slightly happier than men. But they are also more susceptible to depression: a fifth to a quarter of women experience depression at some point in their lives, compared with around a tenth of men. Which suggests either that women are more likely to experience more extreme emotions, or that a few women are more miserable than men, while most are more cheerful.

Two personality traits shine through the complexity of economists' regression analyses: neuroticism and extroversion. Neurotic people—those who are prone to guilt, anger and anxiety—tend to be unhappy. This is more than a tautological observation about people's mood when asked about their feelings by pollsters or economists. Studies following people over many years have shown that neuroticism is a stable personality trait and a good predictor of levels of happiness. Neurotic people are not just prone to negative feelings: they also tend to have low emotional intelligence, which makes them bad at forming or managing relationships, and that in turn makes them unhappy.

Whereas neuroticism tends to make for gloomy types, extroversion does the opposite. Those who like working in teams and who relish parties tend to be happier than those who shut their office doors in the daytime and hole up at home in the evenings. This personality trait may help explain some cross-cultural differences: a study comparing similar groups of British, Chinese and Japanese people found that the British were, on average, both more extrovert and happier than the Chinese and Japanese.

Then there is the role of circumstance. All sorts of things in people's lives, such as relationships, education, income and health, shape the way they feel. Being married gives people a considerable uplift, but not as big as the gloom that springs from being unemployed. In America, being black used to be associated with lower levels of happiness—though the most recent figures suggest that being black or Hispanic is nowadays associated with greater happiness. People with children in the house are less happy than those without. More educated people are happier, but that effect disappears once income is controlled for. Education, in other words, seems to make people happy because it makes them richer. And richer people are happier than poor ones—though just how much is a source of argument.

The View From Winter

Lastly, there is age. Ask a bunch of 30-year-olds and another of 70-year-olds (as Peter Ubel, of the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University, did with two colleagues, Heather Lacey and Dylan Smith, in 2006) which group they think is likely to be happier, and both lots point to the 30-year-olds. Ask them to rate their own well-being, and the 70-year-olds are the happier bunch. The academics quoted lyrics written by Pete Townshend of The Who when he was 20: “Things they do look awful cold / Hope I die before I get old”. They pointed out that Mr Townshend, having passed his 60th birthday, was writing a blog that glowed with good humour.

Mr Townshend may have thought of himself as a youthful radical, but this view is ancient and conventional. The “seven ages of man”—the dominant image of the life-course in the 16th and 17th centuries—was almost invariably conceived as a rise in stature and contentedness to middle age, followed by a sharp decline towards the grave. Inverting the rise and fall is a recent idea. “A few of us noticed the U-bend in the early 1990s,” says Andrew Oswald, professor of economics at Warwick Business School. “We ran a conference about it, but nobody came.”

Since then, interest in the U-bend has been growing. Its effect on happiness is significant—about half as much, from the nadir of middle age to the elderly peak, as that of unemployment. It appears all over the world. David Blanchflower, professor of economics at Dartmouth College, and Mr Oswald looked at the figures for 72 countries. The nadir varies among countries—Ukrainians, at the top of the range, are at their most miserable at 62, and Swiss, at the bottom, at 35—but in the great majority of countries people are at their unhappiest in their 40s and early 50s. The global average is 46.

The U-bend shows up in studies not just of global well-being but also of hedonic or emotional well-being. One paper, published this year by Arthur Stone, Joseph Schwartz and Joan Broderick of Stony Brook University, and Angus Deaton of Princeton, breaks well-being down into positive and negative feelings and looks at how the experience of those emotions varies through life. Enjoyment and happiness dip in middle age, then pick up; stress rises during the early 20s, then falls sharply; worry peaks in middle age, and falls sharply thereafter; anger declines throughout life; sadness rises slightly in middle age, and falls thereafter.

Turn the question upside down, and the pattern still appears. When the British Labour Force Survey asks people whether they are depressed, the U-bend becomes an arc, peaking at 46.

Happier, No Matter What

There is always a possibility that variations are the result not of changes during the life-course, but of differences between cohorts. A 70-year-old European may feel different to a 30-year-old not because he is older, but because he grew up during the second world war and was thus formed by different experiences. But the accumulation of data undermines the idea of a cohort effect. Americans and Zimbabweans have not been formed by similar experiences, yet the U-bend appears in both their countries. And if a cohort effect were responsible, the U-bend would not show up consistently in 40 years' worth of data.

Another possible explanation is that unhappy people die early. It is hard to establish whether that is true or not; but, given that death in middle age is fairly rare, it would explain only a little of the phenomenon. Perhaps the U-bend is merely an expression of the effect of external circumstances. After all, common factors affect people at different stages of the life-cycle. People in their 40s, for instance, often have teenage children. Could the misery of the middle-aged be the consequence of sharing space with angry adolescents? And older people tend to be richer. Could their relative contentment be the result of their piles of cash?

The answer, it turns out, is no: control for cash, employment status and children, and the U-bend is still there. So the growing happiness that follows middle-aged misery must be the result not of external circumstances but of internal changes.

People, studies show, behave differently at different ages. Older people have fewer rows and come up with better solutions to conflict. They are better at controlling their emotions, better at accepting misfortune and less prone to anger. In one study, for instance, subjects were asked to listen to recordings of people supposedly saying disparaging things about them. Older and younger people were similarly saddened, but older people less angry and less inclined to pass judgment, taking the view, as one put it, that “you can't please all the people all the time.”

There are various theories as to why this might be so. Laura Carstensen, professor of psychology at Stanford University, talks of “the uniquely human ability to recognise our own mortality and monitor our own time horizons”. Because the old know they are closer to death, she argues, they grow better at living for the present. They come to focus on things that matter now—such as feelings—and less on long-term goals. “When young people look at older people, they think how terrifying it must be to be nearing the end of your life. But older people know what matters most.” For instance, she says, “young people will go to cocktail parties because they might meet somebody who will be useful to them in the future, even though nobody I know actually likes going to cocktail parties.”

Death of Ambition, Birth of Acceptance

There are other possible explanations. Maybe the sight of contemporaries keeling over infuses survivors with a determination to make the most of their remaining years. Maybe people come to accept their strengths and weaknesses, give up hoping to become chief executive or have a picture shown in the Royal Academy, and learn to be satisfied as assistant branch manager, with their watercolour on display at the church fete. “Being an old maid”, says one of the characters in a story by Edna Ferber, an (unmarried) American novelist, was “like death by drowning—a really delightful sensation when you ceased struggling.” Perhaps acceptance of ageing itself is a source of relief. “How pleasant is the day”, observed William James, an American philosopher, “when we give up striving to be young—or slender.”

Whatever the causes of the U-bend, it has consequences beyond the emotional. Happiness doesn't just make people happy—it also makes them healthier. John Weinman, professor of psychiatry at King's College London, monitored the stress levels of a group of volunteers and then inflicted small wounds on them. The wounds of the least stressed healed twice as fast as those of the most stressed. At Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Sheldon Cohen infected people with cold and flu viruses. He found that happier types were less likely to catch the virus, and showed fewer symptoms of illness when they did. So although old people tend to be less healthy than younger ones, their cheerfulness may help counteract their crumbliness.

Happier people are more productive, too. Mr Oswald and two colleagues, Eugenio Proto and Daniel Sgroi, cheered up a bunch of volunteers by showing them a funny film, then set them mental tests and compared their performance to groups that had seen a neutral film, or no film at all. The ones who had seen the funny film performed 12% better. This leads to two conclusions. First, if you are going to volunteer for a study, choose the economists' experiment rather than the psychologists' or psychiatrists'. Second, the cheerfulness of the old should help counteract their loss of productivity through declining cognitive skills—a point worth remembering as the world works out how to deal with an ageing workforce.

The ageing of the rich world is normally seen as a burden on the economy and a problem to be solved. The U-bend argues for a more positive view of the matter. The greyer the world gets, the brighter it becomes—a prospect which should be especially encouraging to Economist readers (average age 47).

— This article appeared in the Christmas Specials section of the print edition under the headline "The U-Bend of Life"

#Middle-aged | Older People#U-Bend of Life#Christmas Specials | Age and Happiness#Maurice Chevalier#Old Age | Alternative#Vitality | Mental Sharpness | Happiness#Bhutan 🇧🇹#Gross National Happiness#Nobel Prize Winning Economists | Amartya Sen | Joseph Stiglitz#America's General Social Survey#Happy | Contented | Angry | Anxious#Main Factors: Gender | Personality | External Circumstances and Age#Women 😂 | Men 😤

0 notes

Text

@pigeonstab Your tags on the comic made me snort this morning so here, a quick alternate ending to the truce au

#UTDR#UTMV#Truce au#pigeonstab#Seeing that killed me this morning lol#There's an alternate universe where the comic continues as normal#But every other page someone's like ''where's Killer?''#And Dust and Cross share a look before saying he's probably in his room#He wants to be the favourite so bad#But Nightmare refuses to answer questions about who his favourite is#So the age old argument continues

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

/ᐠ。‸。ᐟ\ 📸 ⁷ ∗ ♡゙

/ᐠ。‸。ᐟ\ 📬 ⁷ ∗ ♡゙

@lorlita event prize for you my loveee

#sorry that it took me ages :((#yeritos#kpop moodboard#kpop#brown moodboard#white moodboard#black moodboard#dark moodboard#blue moodboard#red moodboard#alternative moodboard#bios#locs#old moodboard#vintage moodboard#kpop icons#garam moodboard#garam icons#lesserafim moodboard#aesthetic moodboard#coquette moodboard#symbols#pink moodboard#cottage moodboard#retro moodboard#grunge moodboard#bright moodboard#y2k moodboard#green moodboard#yellow moodboard

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

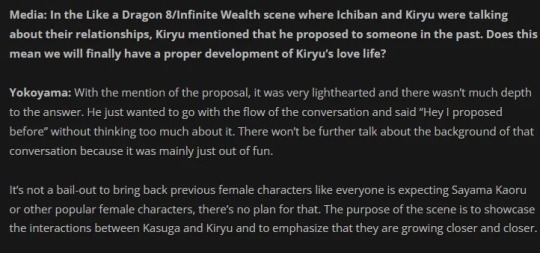

ladies and gentlemen. we got em

#this is so fucking FUNNY dude banxbsnanxb#STRAIGHT PEOPLE ON REDDIT ARE SO MAD AND IM JUST SITTING HERE. GRINNING. PLEASED#that’s 700x more in character than the alternative and I’m just praying this is true/legit (cause I couldn’t find the exact interview this#is from- but I didn’t see anyone saying it was fake on Twitter/Reddit so idk)#to be fair I could only scroll through comments on reddit for like a minute before it started giving me brain damage so#but yeah bdbxsbscshxjdj YOKOYAMA. MAYBE IVE BEEN GIVING YOU TOO LITTLE CREDIT.#I absolutely love seeing all these basic ass straight folks getting so pissy about him not settling down with a nuclear biological family#and a wife and all that and dying at the ripe old age of his fucking mid-50s#like no shit???? what games have you been playing bro the whole fucking Point of his idea of family is unconventional#he’s literally a fucking orphan who didn’t grow up with any biological family are you fucking fr#dgagdhdhd ANYWAY yeah I’m seriously hoping to high heaven that this is legit#rambling#kiryu#yakuza#rgg#rgg8

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Menu] - 0.1 (you are here) - 0.2 - Next Chapter [coming soon]

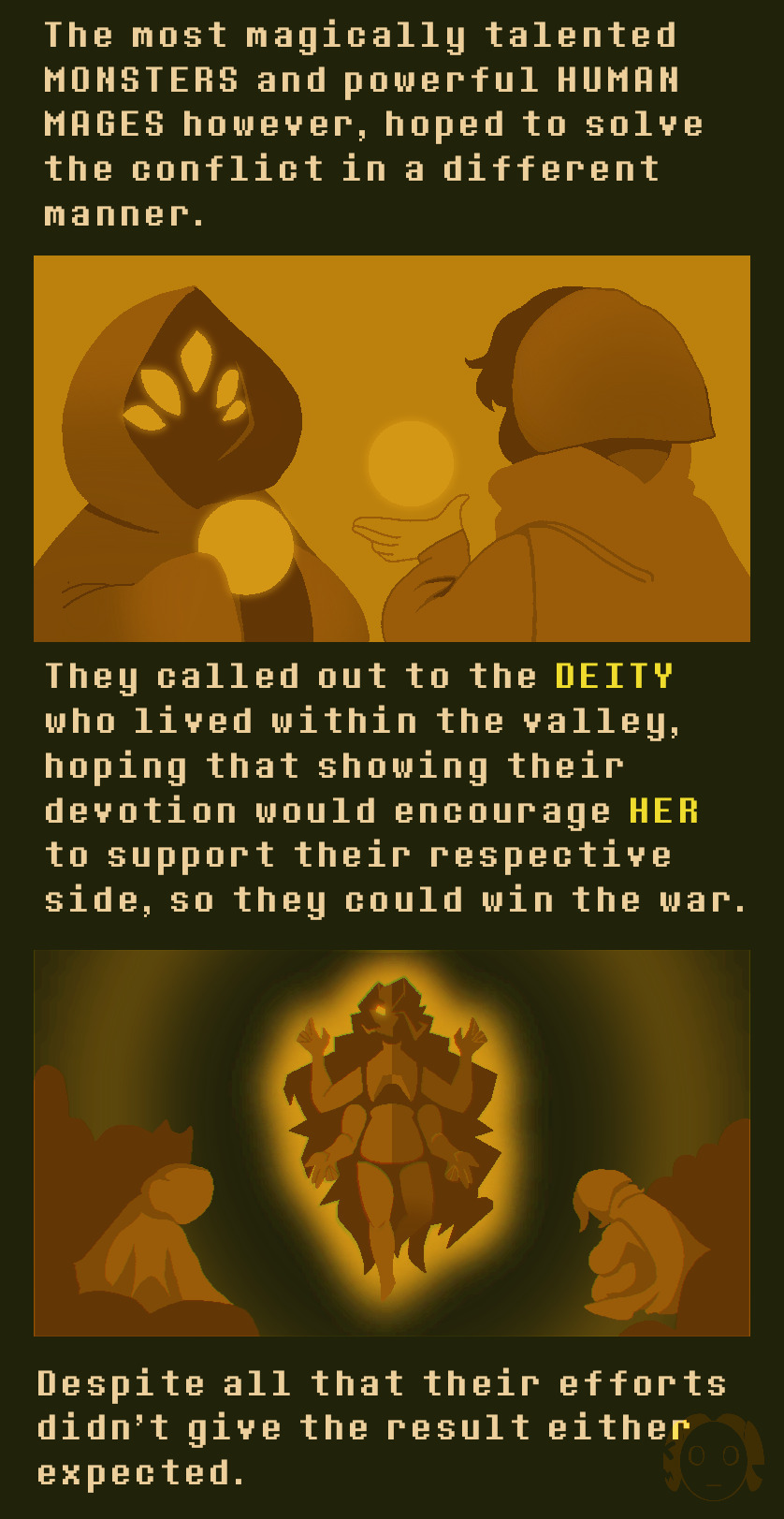

In the spirit of remaking my old stuff, I brought back an old Undertale AU I never really did anything with.

To be honest I never did stray far into the realm of fan made aus since I was a bigger fan of the base game, but after looking through some old drawings I thought I might as well give my silly little childhood creation a more concrete foundation.

So uh, enjoy I suppose. :)

#art#digital art#underquest#undertale#undertale au#undertale alternate universe#undertale fanart#inkdrops art#uq#to think I would bring this old thing back from the dead ages later is wild.#utmv#inkdrops underquest#underquest eng#underquest comic

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

This week on "CJ needs to gush about DAO": Morrigan's dark ritual.

I adore Origins because depending on how serious you take roleplay, every decision you make is a thread that leads back to your origin, and in this case of the ritual, who you choose to romance can have a major impact on how you handle this choice.

For context, my canon run is with a female Tabris who romances Alistair and keeps him as a Grey Warden, and is close friends with Morrigan. It's more in character for my Tabris to reject Morrigan's ritual and not even bring it up to Alistair, which would result in her leaving him behind while she makes the ultimate sacrifice in killing the archdemon... however, agreeing to convince Alistair to do the ritual with Morrigan is the only choice in the entire game where I break roleplay because I'm selfish and weak and I want Tabris to live.

I have a lot of strong feelings about the ritual, like it hurts me. It makes me want to chew on furniture. I can talk about it until I can talk no more. I so badly want to be strong enough to remain in character and reject the ritual.

Let me explain: Tabris survives an origin that deals with sexual assault. She gets kidnapped on her wedding day, she watches the other kidnapped women and her husband get murdered, and then is too late to save Shianni from being assaulted... and Tabris carries that trauma with her throughout the entire game.

If the way to save her life is to ask the two most important people she cares about; one being her lover and the other being her best friend; who she knows hate each other, to have dubiously consensual sex in order to make a baby to absorb the old god soul... she's saying no. The last thing Tabris would ever do is put someone into a sexual situation where consent is at all dubious after what she saw happen to Shianni and nearly happened to herself. She'd rather die than force that upon Alistair and Morrigan.

That's what I mean when I say origin affects everything; I know some will side eye that with "Really? Your warden would rather die than let Alistair sleep with another woman? It's one time, and Alistair agrees to it, so no one needs to die?"

Let me be clear in saying this isn't a "Morrigan slept with my man" issue. Sure, that part's awkward and it sucks, but that's not even breaking water tension, let alone diving into the deep waters to the core of the issue.

For my Tabris, this is about betrayal, consent, and accepting fate.

The person offering Tabris this deal is someone she thought of as a trusted friend who has actually been lying to her the entire time. It doesn't matter what Morrigan's intentions are now or if she genuinely wants to save the wardens. She knew from the beginning why Flemeth sent her with them, she admits as much. She knew a warden would need to make the ultimate sacrifice and then leveraged that to get what she wants. Morrigan waited until the night before, when Alistair and the warden learn one of them has to die to defeat the archdemon, and took advantage of the high running emotions and possibly the fear of dying to make the warden agree to her ritual.

At least, that's how my Tabris interprets this confrontation. She feels betrayed by someone she came to love like a sister and went out of her way to help Morrigan with her mother upon learning what's in Flemeth's grimoire. And then that someone tells her no one needs to die, she just needs to convince Alistair to sleep with her... which is a huge fucking problem.

The Alistair and Tabris romance is slow; it took a long time for either of them to be comfortable with being emotionally vulnerable and trusting each other with basic intimacy, let alone sex. Tabris is mortified at the idea of putting Alistair in this situation. Not only would it feel like a betrayal on her part to ask that of him, but she knows the last thing Alistair ever wants to do is father a bastard who then goes on to grow up without him. How could she possibly ask him to do that?

Then you consider that ritual or no, there isn't a guarantee that they'll survive anyway. Say they do the ritual and Tabris dies anyway; she made Alistair sleep with Morrigan in order to save her and then she died anyway. Or if Alistair dies then Tabris gets to live with the fact that the last person Alistair was with was a woman he hates because she asked that of him… and either way, Morrigan gets to walk away with what she wanted.

Tabris led the group, and she's accepted that if Riordan dies [which he does] then she'll be the one to make the sacrifice, even if it means breaking both hers and Alistair's heart.... except she doesn't because I'm a coward who doesn't want to lose her because my worldstate isn't good without her in it but I also refuse to lose Alistair so I just pretend it plays out differently in my head it's fine-

But... that's how I play Tabris and view the situation. My friend @pi-creates and I have discussed the dark ritual at length. While I play a Tabris who romances Alistair, Pi plays a Mahariel who romances Morrigan, so we have vastly different interpretations of the ritual itself and Morrigan's intentions.

Which yeah, it makes total sense that someone who romanced Morrigan with a different origin, and has the option to do the ritual with her rather than asking someone else to do it, wouldn't see this the way I do.

To quote Pi: "Playing as a male warden in the Morrigan romance makes the whole situation feel different, and maybe it’s because she’s presenting it differently due to the emotional connection, but it feels more like she’s opening up about her initial instructions (that she had been given by Flemeth) and offering a solution to avoid the possibility of death. And for my Mahariel, the constant threat of sudden death has haunted him from the start – he caught the blight and was ripped away from his clan (something he did not want to do in the slightest), got forced into a Grey Warden ritual that could kill him, was forced into a battle that could kill him, going on this whole quest that he never wanted but has now become responsible for regardless of his thoughts on the matter… the dark ritual may be one of the few moments where he is presented with an option to decide if he wants to walk into certain death, or take actions of his own volition to stop it.

"The idea of the ritual still feels like a dodgy thing to do since the ultimate outcome is unknown at that point, he’s taking Morrigan at her word that it will save the warden and that this child would be unharmed, just with an old god soul that she isn’t exactly clear on why she wants that and is determined to runaway immediately after the battle to secure it properly. It could be interpreted that it’s purely a preservation thing, but I’m biased to wanting Morrigan's intentions to not be power based.

"But also, taking part in the ritual isn’t as outlandish for my warden since he and Morrigan have already been involved in an intimate relationship. It’s the future of the ritual that is scarier – the idea of this old-god baby, and the idea of Morrigan insisting that she’s leaving afterwards when Mahariel and her have a loving relationship. He’s hurting, but he doesn’t want to die, he doesn’t want Alistair to die, he doesn’t want Morrigan to leave, he definitely doesn’t want pregnant Morrigan to leave on her own… it’s complicated, but for completely different reasons."

And I find that fascinating. I want to know how other players approach this part of DAO, what origins they play, and who they romanced. Seriously, this is an invitation to anyone reading to share their thoughts.

What about a warden who doesn't even have Alistair in their party because they made Loghain a warden? Is there anyone out there who has Loghain do the ritual with Morrigan and why? What about male wardens who don't romance her? Do you choose to do it with her anyway, or do you ask Alistair or Loghain to do it? Do you tell Morrigan to fuck off with the ritual? Why? Who makes the ultimate sacrifice in that case? And what about Morrigan herself? How do you interpret her intentions/motivations? I want to know.

I'm telling you, this is a discussion that gets me excited, as most discussions about DAO do.

#dao#dragon age origins#alistair theirin#dao alistair#dao morrigan#da morrigan#tw: sa mention#long post#i love origins so much#every time i replay i end up on discord having this discussion with pi because it makes me *emotional*#and yes this is why i was looking up alistair's dialogue about a dead warden before#also want to clear up that while i am harsh on morrigan based on how my tabris feels i don't hate her or anything i love her#morrigan's one of my favorite characters and that's why the whole thing hurts like... tabris was happy for her to come along with them#since she still didn't know alistair well and felt more comfortable with another woman around even though she never felt threatened by him#and for them both to be her closest companions like.... it's a lot to take in#and its not like tabris is totally in the right here- she doesn't tell alistair it's an option when it could be argued that she should've#but like i said i've never actually turned down the ritual because i love my warden too much... i just close my eyes#and pretend there's an alternate solution where Alistair and Tabris do the ritual and they have the old god baby instead sksksks#that way no one has to sleep with someone they hate and alistair gets to be there to raise his child. it's fine everything's fine sksksk#i don't care if it doesn't work that way okay it's the only way this works out better for everyone... except maybe morrigan but still

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

freaks of nature fight over a blueberry muffin

#phonification#crowbar 07#diamonds droog#i was makin a comic a while ago based on dadroog fic i read#coffee shop aus always get me theyre always so good i love cheesy romance . sorry#sorry dude i love seeing old men slash serious dudes in aus youd probs only see in highschool romcoms#this could be alternatively titled mobster gangs fight over who gets to buy from the best bakery in midnight city#kowalski get these men in their 50's or unspecified age due to their biology in silly romcom scenes NOW#homestuck#bonkaroonies scribbles

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

head 𝓸𝒻 mayhem 𝒻𝑖𝓸 ⭒ 𓆟 ˚. 𓂋 ✷⠀𓂃

#2000s nostalgia#film stills#lily chou chou#early 2000s#nostalgiacore#childhood memories#2007#nostalgic#retro magazine#vintage visual#visual archive#korean cinema#japanese cinema#japanese film#alternative#shoegaze#90s film#2000s coming of age#2000s alternative#chinese cinematography#wong kar wai#teenage dirtbag#ggirlhood#rural abandoned#midwest gothic#southern gothic#old films aesthetic#girlblogging#kdrama#ethel cain

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

#i decided not to put nona bc altho shes obviously not actually 6 months old and demonstrates an understanding of sex. it just feels weird.#same way im not putting the 4th house or hot sauce or anything. there’s a certain type/age of character that simply hasn’t matured enough#to be considered for these polls even if you stipulate that the characters age can change to match the poll-takers#like i put gideon and harrow bc even if you’re 30 or w/e you can have a pretty good sense of whether 18 year old you would be into them#or alternatively if you’d be into 30 year old them#and if YOURE 18 but you’d wanna fuck juno zeta if you were closer to her age#does this make sense??? god im just trying to make it not weird lol#tldr some characters are simply not fuckable yet#op#tlt#tlt memes

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avengers: Endgame

hypothesis: Steve and Natasha are both alive and young at the end of endgame.

facts:

the way they explained time travel and the multiverse, Steve would not have been able to return to his own timeline if significant changes had been made.

when retrieving the soul stone, Clint and Natasha were told it's a trade of "a soul for a soul"

the present-day soul stone was destroyed by Thanos, and Gamora did not return.

observation:

the only things we were shown on screen for sure were

1) Steve leaving to return the infinity stones to preserve the timeline

2) him dancing with Peggy

and

3) him appearing to come back as an old man, and refusing to answer questions.

theory:

when Steve returned the stones, the "soul for a soul" deal was enacted in reverse - therefore Natasha should have come back.

based on the explanation, the only way Steve could have come back to this timeline was if little to no changes were made in the past. (therefore not creating another branch in time)

Steve had a dance with Peggy to say goodbye, then returned to the present with Natasha, both the same age as when they left.

Steve used the same technology that Natasha did in CATWS to disguise himself as an old man.

conclusion: it's very much possible that Steve and Natasha came back alive and well, but faked their endings to 1) maintain their cover to go on a secret mission 2) escape responsibilities and retire or 3) for shits and giggles.

secondary hypothesis: if Steve ever gets spotted in public he whispers "no one will ever believe you" and promptly disappears.

#avengers endgame#mcu#marvel cinematic universe#steve rogers#fan theory#please validate me I've finally come to a satisfying conclusion#one that could actually be canon#alternate theory: old man Steve is a skull sent by Nick Fury#secret invasion#catws#captain america#natalia romanova#natasha romanoff#black widow#the soul stone#poor bucky#Steve would never leave you bby#unless it was absolutely necessary#poor yelena#also why would Steve age at a normal pace that doesn't seem right#also this theory works no matter who you ship#because it's ACTUALLY IN CHARACTER#can you tell I'm salty

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

I really like your Silm commentary and writing and I'd definitely be interested in hearing more about how you see the Valar

-@outofangband

There are lots of ways you can read the metaphysics of Tolkien's world. One common reading is what I will call the "naive Catholic" reading, which is basically this: Tolkien was Catholic, so let's import certain basic metaphysical assumptions from Catholicism into his world, like neo-Platonism and a moral law following from a divine natural order, and take at face value, as if offered from the point of an omniscent third-person narrator, all commentaries on how the universe works, both within published works and from those non-published works which can be made consistent with them: LACE, different Silmarillion drafts, etc.

This approach has some problems, IMO. Not least is that we know many of those unpublished works are transitional fossils in an author's evolving thinking about his own world, and were later discarded. Similarly, we know that the major narratives themselves are explicitly mythologized, at various times conceived of as being the mythology of the Elves, some of whom had contact with the Valar in Valinor, or even as the mythology of Numenor, who had these stories thirdhand from the Elves, and wrote them down in some cases millennia after. I think it's also evident, by the way, that while Tolkien was very Catholic in his thinking in some ways, he was less so in others; the picture of him that emerges in his letters is someone who is religious without being dogmatic or ostentatiously pious, someone for whom religion is an important part of his life, but is not so all-consuming he finds it impossible to relate to anybody who is not religious. He is, in other words, a complete human being, and viewing his work only through the lens of his Catholicism is quite in error.

Another way to read Tolkien--which is not in contradiction with the "naive Catholic" reading, it just receives it differently!--is what I think of as the "Lintamande reading": the Valar are bastards. Let's face it: as written, the way the Valar relate to the Children of Iluvatar, and especially the Elves, can rankle. They summon the Elves to Valinor as soon as they discover them at Cuivienen, essentially seeking to annex them to Valinor without giving them a chance to develop their own culture and identity. They don't offer support to them in situ (though this is within their power), and their attitude is essentially "come to us, so we can protect you, or be left alone in Middle-Earth, probably to have to deal with Morgoth on your own." Manwe is framed as a king, ruling Arda from Taniquietil; the halls of Mandos have a purgatorial quality, condemning the unrepentant to a tormented, bodiless existence, while stripping from those who do eventually reincarnate aspects of themselves the Valar find troublesome. The valar refuse to help the innocent or guilty during the centuries of struggle in the First Age, and it becomes clear when they finally do rouse themselves to act that they could have ended this long ago, and with much less suffering.

I find this reading dissatisfying. For one, while it makes Watsonian sense of the evidence on hand, it still treats the text as authoritative in a way that I think quite intentionally it was never intended to be. Mythology is inherently an unreliable narrator! Even in a world where magic and greater-than-human beings are baked into the conceit, we must acknowledge that myth transmits information unreliably, and it has an agenda. Two, from a Doylist perspective, the Silmarillion is grounded in its arcs of catastrophe and eucatastrophe, like music returning to the tonic, part of which is also the general character interpretations offered, and I'm interested in exploring readings that maintain those interpretations while also helping us to understand why, for instance, the Valar act the way they do, or are reported to act thus, and highlighting ways that the apparently authoritative statements presented about how the world works can be complicated.

One interesting point of entry is the word "king" and associated concepts like royalty. Manwe is the Elder King, the viceregent of Iluvatar; Morgoth seeks dominion over all Arda; the leaders of the Elves are invariably described as kings and high kings, all very medieval in character and in keeping with the vibe of a North European mythological past. But where mundane, mortal kingship (as among the humans and elves) intersects with more spiritual notions of kingship and royalty, I think a more complicated picture emerges, one that Tolkien's self-consciously restricted register of language, in keeping with the tonal examples of early medieval sources he draws from, is helpless to explicate very deeply.

In conceptions of the afterlife in the Middle Ages, royalty and signifiers of royalty feature heavily. A great example of this is in the Middle English poem "Pearl," which is about a father mourning his dead daughter, and a vision he receives of her in Heaven; they speak at length from either side of a river, and she is depicted as an ennobled figure, a royal bride of Christ, who in the end is called away to the new Jerusalem. Heaven is depicted as a place of wealth: earth and trees and stones made of precious materials and so forth, and it's interesting to ask, all right, what do all these signifiers of wealth and power mean? These are, after all, very earthly things, and it seems strange that in this Christian text, which is embedded in a theological tradition all about how the last shall be first and the first shall be last, and the human world isn't nearly as important as the spiritual one, that material evidence of luxury and power should be associated with spiritual paradise.

But I think this makes perfect sense, given the context. A hierarchical society, one that does not have a tradition of egalitarianism like we do--the closest it comes is perhaps the rota fortunae and the idea that you who are high might one day be low and vice-versa--can best signify release from the physical and psychic oppression of the world by placing everyone at the top of the hierarchy, and thus obviating the need for everything below. What does paradise look like? A world in which we are all royalty, i.e., we all have the release from the burdens of existence in the manner that in mundane life only (we imagine) kings do; that we all can enjoy that luxury, that freedom from worry about our physical needs.

In a spiritual sense, "kingship" is an effective symbol for things we carve up quite differently in semantic terms, including aspects of words like "freedom," "self-determination," "sovereignty," "independence," "power," and "authority." And this makes sense even when speaking of Jesus: Christ is King, not because Christ conquered the world and handed out large tracts of land as fiefs to his retinue; Christ is King because he is God, omnibenevolent and omniscient, the source of order and justice and goodness for the whole universe.

Royalty in the context of Valinor, especially among the Valar, but also I'd say among the Vanyar and Noldor who live there, seems to me to have much more in common with spiritual notions of royalty than it does mundane ones. Not least since Valinor seems to be what we would call a post-scarcity society. Certainly it's one where the constraints and hardships of life elsewhere in Arda do not apply, and even if it's not truly post-scarcity, the best analogy might be between our modern day, in terms of cheap abundance in the developed world, and the early medieval era, where the distinction for someone from the latter might be pretty theoretical at best. This isn't to say that Valinor is an anarchist utopia, a hierarchyless society--I don't think that reading could be supported by the text--only that Manwe is king of Arda in a very different way than Morgoth seeks to be, or even than Elu Thingol is of Doriath. And that I think is supported by the text.

Moreover, I think it's clear that the Valar are meant to have the tinge of tragedy about them: their vision of the world is incomplete, and though wise and seeing much, they genuinely struggle to understand what to do sometimes. They were wrong to call the Elves to Valinor. They thought they could protect them there, and keep the influence of Morgoth at bay forever, and they couldn't. The fate of the Trees and the Flight of the Noldor proved that. They withhold acting during the First Age because they know their power is too much: they don't want to cause more suffering by unleashing themselves on Middle-Earth than the wars in Beleriand are already causing. And yes, they're angry. But they're not God; they're not omnibenevolent. They have flaws, like the impatience of Aule, the aggression of Tulkas, the possessiveness of Yavanna, and yes, the hesitancy of Manwe. They're children of Iluvatar too, just older ones. And the Doom of Mandos isn't a curse or a punishment: it's a bare statement of fact. You are doing something inadvisable: here are the consequences we forsee. We cannot (or will not) help you.

And things which we might hold up as especially authoritarian qualities of the Valar, things like the Halls of Mandos "purifying" the souls of the dead, have I think to be understood in the context that, definitionally, no one who has ever been there for any length of time has contributed any information to the stories we are reading. And the stories we are reading are composed by figures who do not live in Valinor, who do not have the example of spiritual kingship to draw from, who have only mundane kings and mundane social systems to use to understand these concepts very remote to them in both time and place. These authors are going to have to do a lot to make their hardships in Middle-Earth feel more necessary and more meaningful, to try to speculate about why the world is the way it is, and to inscribe their own particular worldviews and ideologies onto far-off figures like the Valar to try to rationalize their imperfect understanding of them. And that's the only lens we're able to see them through, because Tolkien (who knew all this; but even if he didn't, this would be a reasonable Watsonian take) intentionally chose a documentary device as a core mechanic for his worldbuilding.

#lintamande is theunitofcaring's old tolkien sideblog#just for context#though she hasn't posted in ages#tolkien#the silmarillion#alternate character interpretations of the valar#note that i don't claim this reading is best#and many readings are possible#it's just how i tend to approach the text

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's something interesting to be said about the opinions of different fanbases based on culture and how it affects the votes but it's late and I can't write it out too much so only one example for today: amane

Down under the cut so if it gets too long it won't affect anyone's scrollin

Also warning the tags are long on this one

- <- this indicates a new talking point

Basically I think the jp/more asian parts of the fandom tend to lean towards greater good (amane guilty to protect shidou/mahiru/fuuta because if shidous incapacitated in any way someone's dying, mahiru is prone to dying any moment, fuuta is prone to cult mindset rn). Despite my non japanese speaking ass not being able to gather direct evidence for this, I use those surrounding me (asian in asian country) as evidence; namely, how they're mostly amane guilty voters

-Now I'm not saying my personal take but the reason given for guilting her is well. As much as it will cause her more woe it's one way of guaranteeing the safety of the prison. Shidou is the only medical professional after all, and she's "completely hostile" towards him, acc to jackalope. And she doesn't need to overpower him; shes smart, and could sabotage his equipment or just like. Go for his hands to incapacitate him. I doubt he'd fight back.

-Alternatively, it's because it would cause her to fall back on believing she's right. Telling her she's forgiven with how she's acting would cause her to believe her persistance and dedication to this (harmful) mindset is what got her forgiven in the first place

-Meanwhile more western? English fanbase ig I'm not too sure of demographic, but the English speaking side tends to focus on how it affects her. Because of the belief that another guilty verdict will cause more harm to her, an innocent verdict is the obvious solution. What I've seen is the greater focus on what caused the murder over the murder itself and the effects of an innocent verdict on others and then her beliefs. A focus on the past over what she's promised to do in the present and future perhaps. Idk.

-Another reason for the difference could. Possibly be how punishment is viewed? Western countries have much more stigma over any form of punishment but in Asian countries it's normal. Now while I'd say physical punishment isn't the way to go, the refusal of punishment shouldn't be rewarded (imo) but that's all I'll say on it.

-The English fanbase also focuses a lot on how young amane is and how her circumstances were terrible and all that. Those around me tend to focus more on her thoughts around the crime, what she believes the crime was for and how in the right she thinks she is. This may also be the cause of the moral grandstanding I see so often (ie. If you vote amane guilty you're a baaad person) (I don't agree with this btw. That's stupid this is fiction don't insult others over an opinion)

What I will say is the English speaking side is more sympathetic towards amane. They (y'all?) Take her situation into a lot of consideration, and focus on her age as a large factor. Whereas those around me and I assume might be close to the views of the japanese fanbase are more objective, looking at what harm she could cause and what's the greater of the two evils, as well as what she's going to do with the verdict (ie. Use the inno verdict as her doctrines are correct and very right).

There's slight thought given to her age and circumstance of course, by it that's not the main concern rn. Given the current situation, most of my milgram voting friends stay certain that an innocent verdict will not end well, hence the guilty vote. I mean I have a couple friends that feel bad for guiltying her because of her circumstance, but do it anyway cuz it's for the better. My opinion is that she should've been innocent trial one, since we wouldn't have known the concequences, but it's too late now and an innocent will cause more harm overall

tldr asian fanbase from experience focus on the crime itself + what they're gonna do with that experience whereas eng speaking fanbase focus on the circumstances surrounding the crime and on judging only the crime

In myyy opinion. Judging only the crime based on your interpretation isn't how the system should be working, it should take into consideration the prisoners' attitudes and how the prisoner perceives the crime as well.

I hope this was coherent I typed it out at 11pm and went to bed immediately after and I've barely edited anything cuz awake me is less coherent than half asleep me

Also hope this was an interesting post? This topic is interesting to me but I explain better in speaking over typing so it's probably hard to read but I hope this topic scritches y'all's brains like it does mine :)

#milgram#amane momose#inder the cut to save space kekw#sorry if this post feels like im calling yall lab rats cuz i kinda am#treating the milgram tag like a giant social studies exam (i have not passed social studies this year)#ive done my beat to compare bur i lost half my thoughts while typing this out last night whoops#ive also done my best to be comprehensible but i have too many thoughts at the same time for that#alsp for the record im an amane neutral voter (i dont vote)#j have another point on the age thing about how while eng side takes young age into consideration#it also overstates the maturity of our older prisoners (shidou namely#as ive seen people say that medical guilt theory doesnt work cuz of how extreme his guilt is#of which belongs to a different post but basically dude hes only 29 thats not that old. also to lose everything at any age is devastating#moral grandstanding point may be more indicative of internet culture overall btw but i cant get data on that for jp fans#sorry for being incomrpehensible i jusy talk like this#also very important no insulting anyone in rbs. even if its not me. thats rude#long post#i have a great disdain for people who claim amane guilty voters are evil btw. respect others online ffs#anyways next post will be about shidou and theories around him#specifically my hatred for the organ harvesting theory and my proposed alternate theories#but rhat will be the next time im tired and insane#im also posting this relatively unedited so i dont chicken out 💥 im trusting yall

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

just got this calendar notification from my brother abt his 10k day. birthdays are OUT, denary day notation is IN!!!

#100th day. 1000th day. 10000th day. 100000th day.#ages: < 1 year old. 3 years old. 27 years. 270 years (only for hardcore players of the game)#alternatively u could do 20000th day which is 54 years. fun!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Butler mas

#pokemon#pokemon masters#submas#my art#ingo#emmet#accelgor#escavalier#man do i not have the proper red#i finally finished age old drawings today#fun dact the sketch was made a year ago lol#i got a whole ton of these kinds of drawings that i never posted lol#not me alternating between different areas withing pokemon per day

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

a bunch of my coworkers are 17 and 18 now so sometimes talking to them gives me psychic damage but today I was talking to one coworker in her 60s and another who's 17 and the 17 year old said he misses being emo ajhdksbs and i was like "it's never too late. join us." and my older coworker said "you'll go through phases" and I went "you say that but I'm 24 and I'm dressed like this" and she looked genuinely taken aback that I'm fully in my 20s and still identifying as an emo lmaoooo

#i was like babe i dont think you can call this a phase anymore.......#i was telling the 17 yr old and another coworker who's actually 22 just normal abt a new alternative/goth/emo store that opened today#and i later mentioned smth to the 22 yr old (age not relevant just dont wanna say his name) abt how i didnt expect to live to see 16#so every time im talking to the 17/18 yr olds and i realize im fucking 24 it punches me in the gut all over again#and he goes 'oh so you were REALLY excited about that emo store' LMFAOOOOOOOOOOO#i was like how dare you. but yes.#important to note im dressed ridiculously fuckin emo rn#i usually look more crust punk but i cant wear that stuff to work so i tend to wear more 2004 emo bullshit from hot topic

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking back magical pony friendship gore probably did not do anything beneficial to my brain chemistry at age eleven

#pinkie pie…. her alternate dimension evil twin self made a dress of pony flesh…. did a cannibalism……….#it wasnt even that bad though i got desensitized at a young age#smile hd didnt even bother me i thought it was weird but fun#eleven year old me was. hmm. strange. would not be able to stomach today what media she consumed on youtube.#weirdest hyperfixation ever. mlp years ago. but like short specific hyperfixion on mlp horror during the years ago hyperfixation.#rambles

4 notes

·

View notes