#Main Factors: Gender | Personality | External Circumstances and Age

Text

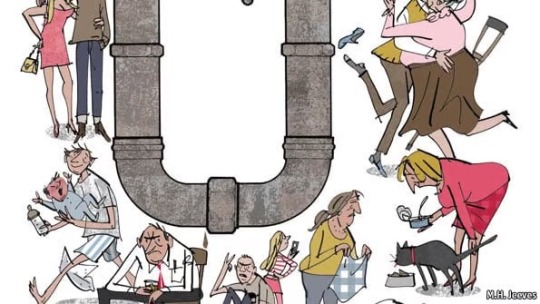

The U-Bend of Life! Why, Beyond Middle Age, People Get Happier As They Get Older

— December 16th 2010 | Wednesday 16th August 2023 | Christmas Specials | Age and happiness

ASK people how they feel about getting older, and they will probably reply in the same vein as Maurice Chevalier: “Old age isn't so bad when you consider the alternative.” Stiffening joints, weakening muscles, fading eyesight and the clouding of memory, coupled with the modern world's careless contempt for the old, seem a fearful prospect—better than death, perhaps, but not much. Yet mankind is wrong to dread ageing. Life is not a long slow decline from sunlit uplands towards the valley of death. It is, rather, a U-bend.

When people start out on adult life, they are, on average, pretty cheerful. Things go downhill from youth to middle age until they reach a nadir commonly known as the mid-life crisis. So far, so familiar. The surprising part happens after that. Although as people move towards old age they lose things they treasure—vitality, mental sharpness and looks—they also gain what people spend their lives pursuing: happiness.

This curious finding has emerged from a new branch of economics that seeks a more satisfactory measure than money of human well-being. Conventional economics uses money as a proxy for utility—the dismal way in which the discipline talks about happiness. But some economists, unconvinced that there is a direct relationship between money and well-being, have decided to go to the nub of the matter and measure happiness itself.

These ideas have penetrated the policy arena, starting in Bhutan, where the concept of Gross National Happiness shapes the planning process. All new policies have to have a GNH assessment, similar to the environmental-impact assessment common in other countries. In 2008 France's president, Nicolas Sarkozy, asked two Nobel-prize-winning economists, Amartya Sen and Joseph Stiglitz, to come up with a broader measure of national contentedness than GDP. Then last month, in a touchy-feely gesture not typical of Britain, David Cameron announced that the British government would start collecting figures on well-being.

There are already a lot of data on the subject collected by, for instance, America's General Social Survey, Eurobarometer and Gallup. Surveys ask two main sorts of question. One concerns people's assessment of their lives, and the other how they feel at any particular time. The first goes along the lines of: thinking about your life as a whole, how do you feel? The second is something like: yesterday, did you feel happy/contented/angry/anxious? The first sort of question is said to measure global well-being, and the second hedonic or emotional well-being. They do not always elicit the same response: having children, for instance, tends to make people feel better about their life as a whole, but also increases the chance that they felt angry or anxious yesterday.

Statisticians trawl through the vast quantities of data these surveys produce rather as miners panning for gold. They are trying to find the answer to the perennial question: what makes people happy?

Four main factors, it seems: gender, personality, external circumstances and age. Women, by and large, are slightly happier than men. But they are also more susceptible to depression: a fifth to a quarter of women experience depression at some point in their lives, compared with around a tenth of men. Which suggests either that women are more likely to experience more extreme emotions, or that a few women are more miserable than men, while most are more cheerful.

Two personality traits shine through the complexity of economists' regression analyses: neuroticism and extroversion. Neurotic people—those who are prone to guilt, anger and anxiety—tend to be unhappy. This is more than a tautological observation about people's mood when asked about their feelings by pollsters or economists. Studies following people over many years have shown that neuroticism is a stable personality trait and a good predictor of levels of happiness. Neurotic people are not just prone to negative feelings: they also tend to have low emotional intelligence, which makes them bad at forming or managing relationships, and that in turn makes them unhappy.

Whereas neuroticism tends to make for gloomy types, extroversion does the opposite. Those who like working in teams and who relish parties tend to be happier than those who shut their office doors in the daytime and hole up at home in the evenings. This personality trait may help explain some cross-cultural differences: a study comparing similar groups of British, Chinese and Japanese people found that the British were, on average, both more extrovert and happier than the Chinese and Japanese.

Then there is the role of circumstance. All sorts of things in people's lives, such as relationships, education, income and health, shape the way they feel. Being married gives people a considerable uplift, but not as big as the gloom that springs from being unemployed. In America, being black used to be associated with lower levels of happiness—though the most recent figures suggest that being black or Hispanic is nowadays associated with greater happiness. People with children in the house are less happy than those without. More educated people are happier, but that effect disappears once income is controlled for. Education, in other words, seems to make people happy because it makes them richer. And richer people are happier than poor ones—though just how much is a source of argument.

The View From Winter

Lastly, there is age. Ask a bunch of 30-year-olds and another of 70-year-olds (as Peter Ubel, of the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University, did with two colleagues, Heather Lacey and Dylan Smith, in 2006) which group they think is likely to be happier, and both lots point to the 30-year-olds. Ask them to rate their own well-being, and the 70-year-olds are the happier bunch. The academics quoted lyrics written by Pete Townshend of The Who when he was 20: “Things they do look awful cold / Hope I die before I get old”. They pointed out that Mr Townshend, having passed his 60th birthday, was writing a blog that glowed with good humour.

Mr Townshend may have thought of himself as a youthful radical, but this view is ancient and conventional. The “seven ages of man”—the dominant image of the life-course in the 16th and 17th centuries—was almost invariably conceived as a rise in stature and contentedness to middle age, followed by a sharp decline towards the grave. Inverting the rise and fall is a recent idea. “A few of us noticed the U-bend in the early 1990s,” says Andrew Oswald, professor of economics at Warwick Business School. “We ran a conference about it, but nobody came.”

Since then, interest in the U-bend has been growing. Its effect on happiness is significant—about half as much, from the nadir of middle age to the elderly peak, as that of unemployment. It appears all over the world. David Blanchflower, professor of economics at Dartmouth College, and Mr Oswald looked at the figures for 72 countries. The nadir varies among countries—Ukrainians, at the top of the range, are at their most miserable at 62, and Swiss, at the bottom, at 35—but in the great majority of countries people are at their unhappiest in their 40s and early 50s. The global average is 46.

The U-bend shows up in studies not just of global well-being but also of hedonic or emotional well-being. One paper, published this year by Arthur Stone, Joseph Schwartz and Joan Broderick of Stony Brook University, and Angus Deaton of Princeton, breaks well-being down into positive and negative feelings and looks at how the experience of those emotions varies through life. Enjoyment and happiness dip in middle age, then pick up; stress rises during the early 20s, then falls sharply; worry peaks in middle age, and falls sharply thereafter; anger declines throughout life; sadness rises slightly in middle age, and falls thereafter.

Turn the question upside down, and the pattern still appears. When the British Labour Force Survey asks people whether they are depressed, the U-bend becomes an arc, peaking at 46.

Happier, No Matter What

There is always a possibility that variations are the result not of changes during the life-course, but of differences between cohorts. A 70-year-old European may feel different to a 30-year-old not because he is older, but because he grew up during the second world war and was thus formed by different experiences. But the accumulation of data undermines the idea of a cohort effect. Americans and Zimbabweans have not been formed by similar experiences, yet the U-bend appears in both their countries. And if a cohort effect were responsible, the U-bend would not show up consistently in 40 years' worth of data.

Another possible explanation is that unhappy people die early. It is hard to establish whether that is true or not; but, given that death in middle age is fairly rare, it would explain only a little of the phenomenon. Perhaps the U-bend is merely an expression of the effect of external circumstances. After all, common factors affect people at different stages of the life-cycle. People in their 40s, for instance, often have teenage children. Could the misery of the middle-aged be the consequence of sharing space with angry adolescents? And older people tend to be richer. Could their relative contentment be the result of their piles of cash?

The answer, it turns out, is no: control for cash, employment status and children, and the U-bend is still there. So the growing happiness that follows middle-aged misery must be the result not of external circumstances but of internal changes.

People, studies show, behave differently at different ages. Older people have fewer rows and come up with better solutions to conflict. They are better at controlling their emotions, better at accepting misfortune and less prone to anger. In one study, for instance, subjects were asked to listen to recordings of people supposedly saying disparaging things about them. Older and younger people were similarly saddened, but older people less angry and less inclined to pass judgment, taking the view, as one put it, that “you can't please all the people all the time.”

There are various theories as to why this might be so. Laura Carstensen, professor of psychology at Stanford University, talks of “the uniquely human ability to recognise our own mortality and monitor our own time horizons”. Because the old know they are closer to death, she argues, they grow better at living for the present. They come to focus on things that matter now—such as feelings—and less on long-term goals. “When young people look at older people, they think how terrifying it must be to be nearing the end of your life. But older people know what matters most.” For instance, she says, “young people will go to cocktail parties because they might meet somebody who will be useful to them in the future, even though nobody I know actually likes going to cocktail parties.”

Death of Ambition, Birth of Acceptance

There are other possible explanations. Maybe the sight of contemporaries keeling over infuses survivors with a determination to make the most of their remaining years. Maybe people come to accept their strengths and weaknesses, give up hoping to become chief executive or have a picture shown in the Royal Academy, and learn to be satisfied as assistant branch manager, with their watercolour on display at the church fete. “Being an old maid”, says one of the characters in a story by Edna Ferber, an (unmarried) American novelist, was “like death by drowning—a really delightful sensation when you ceased struggling.” Perhaps acceptance of ageing itself is a source of relief. “How pleasant is the day”, observed William James, an American philosopher, “when we give up striving to be young—or slender.”

Whatever the causes of the U-bend, it has consequences beyond the emotional. Happiness doesn't just make people happy—it also makes them healthier. John Weinman, professor of psychiatry at King's College London, monitored the stress levels of a group of volunteers and then inflicted small wounds on them. The wounds of the least stressed healed twice as fast as those of the most stressed. At Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Sheldon Cohen infected people with cold and flu viruses. He found that happier types were less likely to catch the virus, and showed fewer symptoms of illness when they did. So although old people tend to be less healthy than younger ones, their cheerfulness may help counteract their crumbliness.

Happier people are more productive, too. Mr Oswald and two colleagues, Eugenio Proto and Daniel Sgroi, cheered up a bunch of volunteers by showing them a funny film, then set them mental tests and compared their performance to groups that had seen a neutral film, or no film at all. The ones who had seen the funny film performed 12% better. This leads to two conclusions. First, if you are going to volunteer for a study, choose the economists' experiment rather than the psychologists' or psychiatrists'. Second, the cheerfulness of the old should help counteract their loss of productivity through declining cognitive skills—a point worth remembering as the world works out how to deal with an ageing workforce.

The ageing of the rich world is normally seen as a burden on the economy and a problem to be solved. The U-bend argues for a more positive view of the matter. The greyer the world gets, the brighter it becomes—a prospect which should be especially encouraging to Economist readers (average age 47).

— This article appeared in the Christmas Specials section of the print edition under the headline "The U-Bend of Life"

#Middle-aged | Older People#U-Bend of Life#Christmas Specials | Age and Happiness#Maurice Chevalier#Old Age | Alternative#Vitality | Mental Sharpness | Happiness#Bhutan 🇧🇹#Gross National Happiness#Nobel Prize Winning Economists | Amartya Sen | Joseph Stiglitz#America's General Social Survey#Happy | Contented | Angry | Anxious#Main Factors: Gender | Personality | External Circumstances and Age#Women 😂 | Men 😤

0 notes

Text

Kakegurui: Psychological Analysis of Midari Ikishima (Anime)

Color Symbolism Theory:

https://bloodorangesangria.tumblr.com/post/164215619840/kakegurui-color-theory-midari-ikishima-purple

Refer to Card 41 (Sexual Masochism Disorder [SMD]) in the following set:

https://quizlet.com/340466138/abnormal-psychology-sexual-disorders-flash-cards/

DSM-5 criteria supports the notion Midari experiences SMD symptoms:

https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/psychiatric-disorders/sexuality,-gender-dysphoria,-and-paraphilias/sexual-masochism-disorder

This is a description of the ESTP personality type:

https://www.16personalities.com/estp-personality

Pathological gambling presents itself in ways akin to Midari's derangement:

https://www.ukessays.com/essays/psychology/a-study-on-pathological-gambling-as-an-addiction-psychology-essay.php

(Note the latter source is theoretical. It is possible psychosexual and nurture-related factors contribute to gambling addiction.)

The neuroscience behind pathological gambling indirectly aligns with Midari's mindsets and functions:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3858640/

Footnotes:

Midari has dealt with anhedonia and hedonism for years and submitted to her innate impulses in extreme portions to reassure herself she is human. Nobody seems to care for her due to her erratic mannerisms and regular exposure to individuals with apathetic tendencies such as Kirari and Runa, so she has felt outcasted. She also seems largely disinterested in others because of this treatment, but she is ecstatic in the presence of Jabami, whom she believes can understand her. This perceived lack of belonging has resulted in suicidal thoughts and an identity crisis, but somewhere in the back of her mind, she wishes to live, so she continually lingers on the verge of life and death through gambling. When deprived of this pleasure she forces on herself, Midari displays mania such as during her altercation with Erimi in Season 2, Episode 2. As a sexually developed teenager who never receives affection from others, she will naturally be perverted to some extent, but this is amplified by her other baggage. The scene in Season 1 where she removes her own eye in front of Kirari to repay debt perfectly summarizes her duality, hardships, and contradiction.

Her occasionally slurred and dramatic speech further defends the idea she is disinterested in her environment, but it may also indicate a disability. She appears slightly deformed, but this may be untrue considering most of the characters possess unusual designs, and she is very simplistic, narrow-minded, and instinctive, which is typical of people with limited cognitive capacities, albeit this is probably linked to her other issues as well. There are some occasions where Midari exposes the insecurities of other characters in a blunt but accurate way like in her conversation with Yumemi in Season 2, Episode 5 and description of Sayaka's past, but this rarely occurs because she is frequently lost in her own thoughts or unfeeling for people. It is somewhat possible her unhealthy fixations mask genuine intellect. At minimum, she is immature given her age.

Midari's design is a combination of both stylish and unkempt, which means she likely attempts to charm men but is not very talented at it, either due to a lack of interest, poor motor skills, or a misunderstanding of the desires of others in comparison to her own. She projects her lust onto others because it is the sole sensation she knows, and she wishes for her peers to savor the same pleasure, which is similar to Jabami's perspective on gambling. This is one of the main reasons Midari resonates with her. This in some regards presents itself as a lesbian infatuation with her, and her design slightly reflects this due to its faintly tomboyish features. Her voice is a tad androgynous, which may be deliberate as it is with many lesbians. Her assymetrical eyes may symbolize her paradoxical existence --- with the bare eye representing the external and the concealed eye signifying the internal. From a general view, it could represent her duality as a whole rather than specific contrasts or vice versa. Her headpiece has hearts on it, implying she needs love but is warped in the head. Midari is visibly desperate and isolated, so she may be accustomed to others' disgust towards her and unfamiliar with positive emotions like love. The pain of being loathed is one of the many miseries she lies to herself about; the woman convinces herself she enjoys it to cope. Nevertheless, she is not entirely unsympathetic, which is subtly insinuated by her investment in Jabami and lecture towards Yumemi about her absence of talent.

According to the Kakegurui wiki, "Midari" translates to "reckless" and "chaotic" while Ikishima means "hope", "aspiration", "intention", "motive", "plan", "resolve", "shilling", and "to wear". Midari's forename is obviously applicable to her behaviors, but her surname is enigmatic and ironic; she is unsure of her own objectives, yet it implies a sure sense of purpose. Combined with her forename, however, this is more sensible because her goals are stubborn, mad, and counterintuitive. On the other hand, the meaning "to wear" may allude to Midari's fashionable look and role. Additionally, the girl "wears" her abnormality like a badge of honor, and she is "worn" out because of her circumstances and hurdles.

Midari's personality type is almost indescribable, but the most prominent possibility is ESTP, also known as the Entrepreneur. She is a very unhealthy case, and she is somewhat ambiverted. Her position in the student council reflects a social nature, but this is not necessarily evidence in itself; she is talkative and desperate for affection, but the kind of attention she seeks is incomprehensible to most, so she tends to be isolated. She asserts herself in situations with methods others are throw off or often revolted by, never hesitating to scrutinize on the basis of her observations, which are frequently more accurate and insightful than what many of her peers could muster. This is displayed when she describes Sayaka to Yuriko and criticizes Yumemi's strategies for stardom. Unless her obsessions obstruct her ability to ruminate analytically, she is largely logical and unbiased, so her fundamental thought processes are more rational than emotional in everyday circumstances. Due to her overall disconnection from tangible, concrete reality and reliance on risks and probability, it is obvious she possesses many intuitive qualities, but these do not quite dominate her sensory ones. Midari usually approaches casual issues pragmatically and with tactility; she views personal experience as her primary method of comprehension and views these events as snapshots of a greater picture. Midari improvises much of the time and does not seem to limit herself to a timetable or routine, so her prospecting traits overpower her judging traits. The girl's unstable and inconsistent reactions render her fifth letter a T rather than an A. Hence, her acronym stands for "Extroverted, Observant, Thinking, Prospecting, Turbulent". Considering the severe but immeasurable despair she has experienced over the years, her personality has slightly changed, albeit she was clearly demented from the beginning. The enneagram personality test is highly controversial, and the alignment chart is rather one-dimensional, so neither shall be used for her. However, via the latter system, Midari would certainly be chaotic.

Midari is not directly connected to Kakegurui's themes, but she is one of the worst possible products of them. She is the outcome of oppression caused by capitalism and Christianity when left to their own devices.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

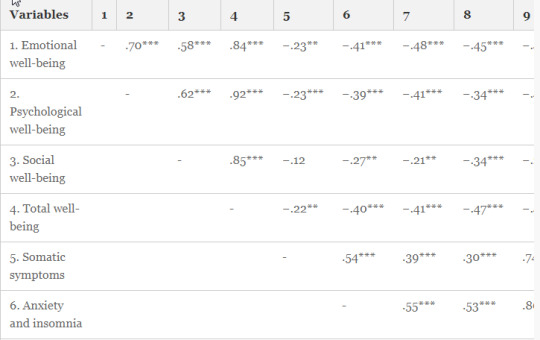

The impact of personality on job and life satisfaction among young professionals in Russia

Literature review

Introduction and background

The main purpose is to explore the relationship between the big five personality traits, employee engagement, and both job and life satisfaction. We will contribute to the personality and work engagement literature by examining the influence that personality traits have on satisfaction with life which mediates job satisfaction that in turn impacts their work engagement.

Work engagement: vigor, dedication, and absorption.

The Big Five traits: agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experience and neuroticism.

Demographic factors: gender, age, job, city, level of management, salary, job experience, education level, marital status.

Working definitions

The Big Five personality traits include agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, openness to experience and neuroticism. BFI-scale was created by John and Srivastava in 1999.

Personality is a set of characteristics that reflects everyone’s individuality, which tends to be changed depending on external influence.

Big five personality traits:

o Neuroticism is characterized by “individuals prone to psychological distress, unrealistic ideas, excessive cravings or urges, and maladaptive coping responses”, according to Crown (2007 cited in Bueno, 2019). Regarding employees’ job neuroticism as explained by Langelaan et al., (2006) tends to be associated with negative affect and negative affect has been linked with lower levels of job satisfaction (Connolly, Viswesvaran, 2000).

o Extraversion is characterized by “the intensity of interpersonal interaction including activity level, need for stimulation, and capacity for joy” by Crown (2007 cited in Bueno, 2019).

o Openness to experience is characterized by “proactive seeking and appreciation of experience for its own sake, toleration for an exploration of the unfamiliar” by Crown (2007 cited in Bueno, 2019).

o Agreeableness is characterized by “the quality of one's interpersonal orientation along a continuum from compassion to antagonism in thoughts, feelings, and action”s by Crown (2007 cited in Bueno, 2019).

o Conscientiousness is characterized by “the degree of organization, persistence, and motivation in goal-directed behavior”, it “contrasts dependable, fastidious people with those who are lackadaisical and sloppy”, according to Crown (2007 as cited in Bueno, 2019).

Person-organization fit (P-O fit) is an area “whose concern is the antecedents and consequences of compatibility between people and the organizations in which they work” (Farooquia, Nagendra, 2014) or a “match between the individual and the organizational environment” (Mandalaki, Islamb, Lagowskac, et al., 2019).

Job satisfaction is defined as “positive feeling about one’s work and work setting” by Schermerhon et al. (2011). According to Hoppock (1935, cited in Bueno, 2019) satisfaction is “a combination of psychological, physiological and environmental circumstances that cause a person truthfully to say, "I am satisfied with my job".

Life satisfaction is a “global assessment of a person's quality of life per his or her chosen criteria” (Shin, Johnson, 1978).

Work engagement is “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor (i.e. high levels of energy and mental resilience), dedication (i.e., exceptionally strong involvement in one's work), and absorption (i.e., being totally engrossed in one's work)” (Schaufeli, Salanova, et al., 2002). A shortened version was made by Schaufeli, Shimazu, Hakanen, Salanova, et al. (2017).

Big Five personality traits

“Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. Western management must awaken to the challenge, must learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership for change. Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. The transformation is everybody's job.” (Out of the Crisis, by W. Edwards Deming)

Organizations constantly make changes that they need in daily life, but those changes should be compatible with their workers. Humans are difficult creations, and, depending on how employees are satisfied with their life and job, it might influence how they respond to items in the Big five inventory. If they are satisfied with their life, they tend to be more satisfied with their work, hence they are more engaged at work. Thus, organizations should be able to understand the personality traits that makeup who our employees are and how their personality traits influence their fit to the organization, how they are engaged at work. In 1949, the first model known as "Big Five" personality traits was made by Fiske. The five factors were social adaptability, conformity, will to achieve, emotional control, and inquiring intellect. McCrae, Costa (1987) have recently developed a method of data collection the NEO Personality Inventory to measure the Big Five personality traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness.

How personality traits influence life and job satisfaction

Several studies tell us that the Big five personality traits strongly impact our feeling of satisfaction. But the questions about which traits influence much more significant and with what impact, positive or negative, depending on each case. These questions will be hopefully investigated in our research. For example, Judge’s cross-country analysis (2002), focused mainly on Western countries, showed us that extraversion, neuroticism, and conscientiousness became significant predictors of job satisfaction among employees. Zhai, Willis, et al., (2013) claimed that among all the Big five personality traits, just extraversion was significantly related to job satisfaction. Templer (2012) in his research notiсed the importance of such Big Five personality traits as extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism because they were in strong relation with job satisfaction. Several studies highlighted the low level of neuroticism when the higher state levels of job satisfaction were obtained (McCann, 2018; Chandra, et al., 2017). Connolly, Viswesvaran (2000) stated that “extraversion is associated with positive emotions, and positive emotions generalize to job satisfaction”, that one more time proved that there is a strong connection between personality and satisfaction. At the same time, Iorga, M., Dondas, C., et al. (2017) in their research identified that neuroticism and extraversion were mostly related to job satisfaction, while agreeableness and conscientiousness were less related and there was no relationship between job satisfaction and openness to experience. However, Bui (2017) in his study didn’t find any connections between extraversion and job satisfaction, which contradicts previous research. McCrae, Costa (1991) argued that “agreeable individuals have greater motivation to achieve interpersonal intimacy, which leads to higher levels of well-being, which positively relates to life satisfaction”. Following this assumption, Judge (2002) stated "that the same process should operate regarding job satisfaction. Conscientiousness is related to job satisfaction because it “represents a general work involvement tendency that leads to a higher likelihood of obtaining satisfying work rewards” (Organ, Lingl, 1995). Moreover, a number of authors have reported that conscientiousness demonstrated a positive influence on job satisfaction as well as agreeableness (DeNeve, Cooper, 1998; Judge, 2002; Connolly, Viswesvaran, 2000). Judge (2002) also stated that neuroticism had the strongest negative correlation with job satisfaction, which is followed by conscientiousness and extraversion with a positive correlation with job satisfaction.

The mediating role of person-organizational fit

It is strongly important to have a good person-organization fit. There is a large volume of published studies describing the mediating role of P-O fit between personality factors and life and job satisfaction. According to the research of Farooquia, Nagendra (2014), P-O fit remains a strong factor in determining job satisfaction and the performance of the employees. It significantly correlates with employee work engagement and illustrates “the alignment between organizational and individual norms and values” (Biswas, Bhatnagar, 2013; Prasasti, Tiarani, et al., 2019). P-O fit also leads to positive attitudinal outcomes, it reduces anxiety and increases individual commitment and involvement (O’Reilly III, Chatman, Caldwell, 1991; Posner, 1992; Vancouver, Schmitt, 1991; Chung, Im, Kim, 2019). Chen, Sparrow, Cooper (2016) noticed that P-O fit positively predicts job satisfaction by improving the working state for the more harmonious organization of management for employees. Researchers highlighted that “the relationship between P-O fit and job satisfaction is indirectly linked through job stress”, which is important for practical implications of person-organization fit concept (Chen, Sparrow, Cooper, 2016). It was also highlighted that “employees who have an organization fit will follow all organizational cultures without complaining, also work harder and give better results to the organization because their needs are met by the organization” (Farooquia, Nagendra, 2014). Herkes, Ellis, Churruca, Braithwaite, (2019) stated a significant role of P-O fit in the relationship with job satisfaction. It “reduces uncertainty and turnover intentions while increasing satisfaction, identification, and commitment toward their organization” (Chung, Im, Kim, 2020). P-O fit positively influences job satisfaction - 28 articles (Herkes, Churruca, Ellis, et al., 2019). One more research also noticed that P-O fit “enhances the effects of other-oriented motives that allow employees to further engage in constructive behaviors” for being compatible among colleagues” (Chung, Im, Kim, 2020). In addition, authors have found that “the relationship between organizational identification and job performance is enabled through P-O fit” (Mandalaki,, Lagowska, Tobace, 2019). There is also the relationship between strong organizational support and job satisfaction which has been widely investigated by Cullen, Edwards, Casper, et al. (2014). In conclusion, we can say that p-o fit usually plays an important mediating role, that helps to deepen the research.

Work engagement

Much of the current literature on work engagement pays particular attention to its connection with Big five personality factors (Langelaan, Bakker, Doornen et al., 2005; Watson, Clark, 1992; Kim, Shin, Swanger 2009; Inceoglu, Warr 2012). For instance, Langelaan, Bakker, Doornen, et al. (2006) established low neuroticism and high extraversion as the major influential variables for high work engagement among employees. Kim, Shin, Swanger (2009) said that “work engaged employees showed high scores of conscientiousness and non-work engaged showed high scores on neuroticism”. At the same time, Kim, Shin, Swanger (2009) in his research noticed that there is no influence of extraversion on work engagement. Detailed examination of big five personality traits by Zaidi, Wajid., et al. (2012) showed that all of them except neuroticism significantly influence work engagement. Christian, Slaughter (2007) found out that work engagement was positively related to job satisfaction. Attridge (2009) stated that organizations still struggle with keeping their employees engaged. Hence, there is still a need to deepen knowledge of such phenomena and to investigate it more from different sides. Vallerand’s (2010) findings suggested that “work engagement is not merely a manner of high vs. low engagement rather the quality of engagement”. Furthermore, “when one is passionate about work, work becomes an integrated part of one's self” (Vallerand, Lafrenière, 2012). Arnett (2015) stated that “young professionals are eager to find engaging work that they can enjoy, and to do something important that can make some kind of positive contribution to the world around them”. According to Islam, (2014) “the organizational commitment, job content and job involvement have a direct effect on job satisfaction”. Djoemadi, Setiawan, Noermijati, et al. (2019) proved that job satisfaction could increase work engagement. According to the article from Forbes: “Employee engagement and happiness is definitely one of the topics for modern management and the future of work, only 13% of employees are engaged and 87% are not” (Morgan, 2014). Boston Consulting Group surveyed over 200,000 people around the world in 2014 and found out that getting appreciated for their work was the most important factor for employee happiness, unlike a salary, that got the 8th place (Strack, Linden, Booker, et al., 2014). In 2014, the publication of Vybornov found that feedback had a major impact on job satisfaction among other factors, that one more time proved the results of a survey conducted by Boston Consulting Group. According to the opinion of researchers, “when people feel appreciated, their job satisfaction skyrockets” (Cullen, Edwards, Casper, Gue, 2014). Ward (2019) also highlighted that work itself and recognition were only predictors of job satisfaction among other factors. Also, an interesting fact is that Hakanen, Schaufeli (2012) noticed that work engagement could predict life satisfaction. Job and personal life aspects are in close connection to each other, therefore “private companies with high standards carefully provide and create contexts where personal and professional aspects develop in balance” (Iorga, Dondas, Ioan, et al., 2017). Consequently, the work-life balance is strongly related to our topic and can be used for further research.

Research questions and hypotheses

1. Do personality factors influence life and job satisfaction directly or mediated by p-o fit?

The first step of the present study is to empirically examine the hypothesized direct connection between personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and life and job satisfaction. The second step of the present study is to empirically examine the hypothesized mediation role of p-o fit on the relationship between personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and life and job satisfaction.

H 1: P-O fit mediates the relationship between personality traits and life and job satisfaction.

In line with the hypothesis, it is predicted that:

1) Extraversion has a positive influence on job satisfaction (Connolly, Viswesvaran, 2000; Zhai, Willis, et al., 2013), or maybe there will not be any correlation between extraversion and job satisfaction (Bui, 2017).

2) Conscientiousness has a strong positive influence on job satisfaction (DeNeve, Cooper, 1998; Judge, 2002; Connolly, Viswesvaran, 2000).

3) Agreeableness has a positive influence on job satisfaction (McCrae, Costa, 1991; Organ, Lingl, 1995; Judge, 2002) and agreeableness has a weak influence on job satisfaction (Iorga, M., Dondas, C., et al, 2017).

4) Neuroticism has a negative influence on job satisfaction (McCann, 2018; Chandra, et al., 2017; Iorga, M., Dondas, C., et al, 2017; Judge, 2002).

5) Openness to experience has an influence on job satisfaction (Judge, 2002; Templer, 2012). That contradicts the other author (Iorga, Dondas, et al., 2017).

6) P-O fit has a strong positive influence on job satisfaction (Herkes, Ellis, Churruca, et al., 2019; Herkes, Ellis, Churruca, Braithwaite, 2019; Chen, Sparrow, Cooper, 2016; Farooquia, Nagendra, 2014).

7) P-O fit has a strong positive influence on work engagement (O’Reilly, Chatman, Caldwell, 1991; Vancouver, Schmitt, 1991; Posner, 1992; Biswas, Bhatnagar, 2013; Chung, Im, Kim, 2019; Prasasti, Tiarani, et al., 2019)

2. Do personality factors influence job satisfaction directly or mediated by life satisfaction?

The third step of the present study is to empirically examine the hypothesized direct connection between personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and job satisfaction. The fourth step of the present study is to empirically examine the hypothesized mediation role of life satisfaction on the influence between personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and job satisfaction.

H2: Life satisfaction mediates the relationship between personality traits and job satisfaction.

3. Do personality factors influence work engagement directly or mediated by life satisfaction?

The fifth step of the present study is to empirically examine the hypothesized direct connection between personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and work engagement. The sixth step of the present study is to empirically examine the hypothesized mediation role of life satisfaction on the influence between personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) and work engagement.

H3: Life satisfaction mediates the relationship between personality traits and work engagement.

1) Personality traits have a strong positive influence on work engagement (Watson, Clark, 1992; Langelaan, Bakker, Doornen et al., 2005; Langelaan, Bakker, Doornen, et al., 2006; Inceoglu, Warr, 2012; Vallerand, Lafrenière, 2012).

2) Low neuroticism has an influence on work engagement (Langelaan, Bakker, Doornen, et al., 2006) or no influence of neuroticism on work engagement (Zaidi, Wajid., et al., 2012) .

3) High extraversion has an influence on work engagement (Langelaan, Bakker, Doornen, et al., 2006; Kim, Shin, Swanger, 2009) or no influence of extraversion on work engagement (Kim, Shin, Swanger, 2009).

4) Conscientiousness has a strong positive influence on work engagement (Langelaan, Bakker, Doornen, et al., 2006).

5) All personality traits except neuroticism have strong positive influence on work engagement (Zaidi, Wajid., et al., 2012).

6) Work engagement has a strong positive influence on job satisfaction (Christian, Slaughter, 2007).

Data Collection Instruments

Data analysis

The survey design is a common method used by researchers to collect a large amount of data from different regions in the country. Online survey is more efficient than paper survey in terms of resources, cost and time, also it limits human error in data transcription and coding. We chose to survey respondents to better understand their personality and life satisfaction as well as perception of their companies. Survey was created to overview respondents’ personality traits, levels of their job and life satisfaction, person-organization fit in the company and work engagement level across all professional spheres, formally accepted in Russian Federation according to Rosstat, VCIOM, FOM and McKinsey statistical approaches. Respondents were young professionals from 18 to 40 years who worked in Russian companies. All the professional spheres and jobs were adopted from Headhunter.ru catalogue. Pre-test was made to sort through the appropriate respondents, including such factors as job (respondent should work right now) and age (respondent should be from 18 to 40 years old).

In order to obtain participants for a survey, the researchers used a snowballing-sampling methodology. Invitations were posted in social networks (VK, Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn) on researcher’s pages and inside different professional communities of people (Skillbox, Dolina groups). Moreover, invitations were delivered across HSE study offices’ resources into students’ corporate emails and by professional contacts of authors and their academic supervisor. All answers were conducted using Google forms service, which provides free opportunity to overview target audience’s characteristics.

In addition, as it was introduced above, researchers used interviews for data collection to provide an additional qualitative overview of job and life satisfaction and work engagement among young managers to overcome possible biases of the research and understand them deeply.

Instruments

There were five scales of measuring that was used in the research containing 57 items with additional 15 items on demographic, geographic and professional measures of respondents and 1 item on agreeableness of further participation in the interview section.

1. It was aimed to measure the big five personality traits using the Big Five Inventory (BFI) scale (44 items; John, Naumann, Soto, 2008; Srivastava, 1998). The five personality factors that were measured by this scale include conscientiousness (9 items, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.825), agreeableness (9 items, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.581), neuroticism (8 items, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.857), extraversion (8 items, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.835) and openness (10 items, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.828). In order to investigate respondents’ answers in Russia, there was a Russian version of BFI translated by (44 items; Shchebetenko, Weinstein, 2010). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are 0.82 for extraversion, 0.78 for neuroticism, 0.76 for conscientiousness and 0.78 for openness to experience. All BFI subscales were distributed normally, all KS d <.13, all p> .2

2. To measure work engagement, the current study uses the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-3) (3 items; Schaufeli, Bakker, 2017). The UWES-3 scale has appropriate psychometric properties, with internal consistency reliability exceeding the accepted value of 0.70 (Schaufeli, Bakker, 2017).

3. To measure job satisfaction the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire Job Satisfaction Subscale (MOAQJS) was used (1 item; Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, Klesh, 1979) with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranging from 0.67 to 0.94.

4. Life satisfaction was measured by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (5 items; Pavot, Diener, Colvin, Sandvik, 1991). The SWLS scale shows good internal consistency and reliability when it is compared to other satisfaction with life scales (Pavot, Diener, Colvin, Sandvik, 1991). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the SWLS question vary from 0.61 to 0.81.

6. Finally, the person-organization fit was calculated on the base of P-O fit Questionnaire (4 items; Cable, DeRue, 2002). The Cronbach’s alpha score for this scale is 0.75 that indicated acceptable reliability.

Therefore, the entire study consisted of 73 items. Understanding of translation from English to Russian was tested on 5 respondents, who finished both English and Russian variants of the survey. Russian variant of survey was pre-tested on 10 respondents. The answers have been recorded using a 5-step Likert scale, where 1 means strong disagreement and 5 means strong agreement.

Data analysis

Before analyzing the results, the data was prepared and checked carefully in our study. Data were screened for missing values, outliers and testing for assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variance, and homoscedasticity. Inter-item reliability and Pearson bivariate correlations were conducted to determine if any study variable showed no significant relationship with other variables and demonstrated poor internal consistency. For data analysis, R-studio will be used. All hypotheses will be checked using Structural equation modelling (SEM). In the structural equation modelling, latent variables were drawn as circles, measured variables were shown as squares, residuals and variances were drawn as double-headed arrows into an object.

Data https://drive.google.com/open?id=1_uYyw2-4EdMmHlrf-OKhZdpRti1iDgZ-

Survey Sample with Codebook https://drive.google.com/open?id=14RiZQHHxIUq_o9Kon8DMjauI2St4lv0A

Interviews with 20 respondents

1 note

·

View note

Text

Annotated Bibliography

1-Zubala, A., MacIntyre, D. J., and Karkou, V.,Art psychotherapy practice with adults suffering from depression in the UK: qualitative findings from depression-specific questionnaire., The Arts in Psychotherapy (2014), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.007.

This research was carried out in the United Kingdom in 2014 with ethical approval of Queen Margaret University of Edinburgh in 2011. The research aimed to find out how art interventions are used by art therapist to tackle depression in adults. 5 art therapists prepared a thematic questionnaire with specifics of depression and were surveyed in adults aging 18-64. The limiting factors of the research were lack of qualitative data collection and small number of research surveyors. The conclusions give away that various definitions of depression were given hence the final data cannot be accepted widely and may be used with caution. It also said that the arts therapists use mix methods of theoretical treatment depending on the client’s needs. The results supported various theoretical approaches e.g. verbal therapy, solution based therapy, narrative therapy, non-verbal and systemic therapy etc.

2- Waller, D, & Sibbett, C 2005, Art Therapy and Cancer Care, McGraw-Hill Education, Berkshire. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [23 November 2020].

Diane Waller, Professor of art psychotherapy at Goldsmiths University of London and Caryl Sibbett, art psychotherapist, senior trainer and supervisor at British association of art therapy have presented Broadly theoretical perspective on art therapy and cancer care, this chapter of the book “art therapy and cancer care” is from the second part where the practitioners have contributed one case study in which patient tells that during her fight with breast cancer and therapy sessions she has seen the riches of life. Despite being fully aware of the illness of the body, the subconscious brain decides to intervene in the session and illness-free work was produced to alter the reality. Few sessions in-between informed severe helplessness and urge to fight the circumstances and few showed letting go of the pain eventually and being brave in the reality for what it is, these experiences ask the patient to come out of the mind and onto the paper. Art making demands next move continuously until you answer the paper hence you stimulate the brain.

3- Gress, Carol E., "The Effect of Art Therapy on Hospice and Palliative Caregivers" (2015). Nursing Theses and Capstone Projects. Paper 211.

This research was submitted to the faculty of Gardner-Webb University Hunt School of Nursing in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Nursing Degree intended to answer the question of whether art therapy is effective on compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in hospice/palliative caregivers through art therapy for the purpose of understanding and healing traumatic emotional reactions to events such as suffering or death. It was found out that emergency nurses in comparison to hospice nurses had more anxiety towards death and experienced symptoms of burnout. Emotional distance was the main reason of this for which art therapy sessions proved to be of better coping strategies that dealt with self-awareness, teamwork and cooperation by identifying each other’s emotional needs. Hence caregivers will be required to learn new ways of delivering care in hospice/palliative care.

4- Chong, C.Y.J. (2015). Why art psychotherapy? Through the lens of interpersonal neurobiology: The distinctive role of art psychotherapy intervention for clients with early relational trauma. International Journal of Art Therapy, 20(3), pp.118–126.

Chong presents in her article, the relationship of art and neurobiology in her article where she discusses the language of the mind and the language of the art both as the limbic dialogue between the subject and the object, and hence she puts forward the idea of art psychotherapy as the most valuable and trusted intervention whilst addressing mental conflict in early relational trauma or intrapsychic conflicts especially in comparison of verbal therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy, establishing art psychotherapy as the ultimate language of emotions and irrespective of logic as emotions and logic don’t really go hand in hand.

5- Celine Schweizer, Erik J. Knorth, Tom A. van Yperen, Marinus Spreen, Evaluation of ‘Images of Self’ an art therapy program for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASD), Children and Youth Services Review, Volume 116, 2020, 105207, ISSN 0190-7409

This study was conducted in the primary school of the Netherlands and The article mentions the “images of self” programme run through children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder under the supervision of art therapists, the therapy type was particularly art based, the number of participants was 12 children between ages 8 to 12 and the parents as the source of primitive informants, as well as the teachers and art therapists. All children showed anxiety and were reluctant with the experiment at first. The methodology used was mix and measurements of pre-test and post-test were determined, which collectively showed improvements in social behavior of children and happiness in the children’s mood was evident.

6- Cassandra Rowe (2016). Evaluating Art Therapy to Heal the Effects of Trauma among Refugee Youth: The Burma Art Therapy Program Evaluation. Sage Journals, Volume: 18 issue: 1, page(s): 26-33

The article opens by defining art as therapeutic tool where it is described that art helps heal mental illness and promotes self growth, followed by the importance of using art therapy clinically with the patients of trauma especially the refugees, emphasizing that art is so much related to symbolism and helps retrieve memories through visuals, therefore art therapy was ideal with the vulnerable refugees who had been displaced from homes. The experiment was run through assessment tools and the methodology was clinical and four validated tools were used with 30 participants with a follow-up to determine levels of increased or decreased behavioral problems.

7- Caroline Case, Tessa Dalley. 11 Jun 2014, The art therapy room from: The Handbook of Art Therapy Routledge Accessed on: 06 Apr 2020

This chapter gives detailed insight into the art therapy rooms where art activities may be carried out depending on the client group, the author has provided theory behind the practical setting of the art room, stating that art room can be a significant and memorable place for a client, because amidst of the chaos, the client may consider art therapy room as his/her solace and may use objects and his/her therapists as the remedial source of his/her internal or external problems. Meanwhile, potential triggers are mentioned in the chapter, for example an art therapy room by the view of a calm beautiful lake can also be a dark deep haunting because of the lake water where crocodiles can eat humans. Hence art therapy rooms differ with clients and are carefully planned.

8- Hinz, LD 2019, Expressive Therapies Continuum: A Framework for Using Art in Therapy, Taylor & Francis Group, Milton. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [18 January 2021].

The chapter broadly explains the kinesthetic movement use in the expressive therapies continuum emphasizing that it is the basic mode of expression. When dancers move their bodies, they express through their bodies, without words, hence any assessment in art therapy that is preverbal meaning if we want to retrieve memories from the childhood, then kinesthetic movement can play a key role Kinesthetic movement and release of bodily tension are directly proportional, the more attuned is the body with nature’s rhythm, the less the bodily tension it carries Further explaining the importance of movement of body, the chapter establishes that according to research, action influences images and thoughts, which inform decision-making and hence action plays a vital role in cognition.

9-King, J.L. (Ed.). (2016). Neuroscience concepts in clinical practice. Art Therapy, Trauma, and Neuroscience: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge.

This chapter covers basics of brain, neurons and neural network through which messages travel in the body’s periphery which is responsible for the humans to take actions and initiate and sustain behaviors. The chapter also establishes that just like every human is different, every brain is different and has it’s own individuality and pace of plasticity. And at some point some decision makings alter the brain’s structure due to intensity and demanding nature of the networks. The chapter further talks about genetic mutations as they are responsible for neuromodulation as each brain has some factors under which it is effected for example genetics, gender and environment so what we can do is When we combine multimodality imaging with a detailed clinical history, subjective symptoms, clinical observation, and objective neurobehavioral assessment, to define a patient’s unique strengths and weaknesses. We can gain greater understanding of the person.

10- Rubin, J.A. 2016, Marcia Rosal. Cognitive and behavioral art therapy. Approaches to Art Therapy: Theory and Technique, 3rd edn, Taylor and Francis, Florence. P 333

The chapter explains development in cognitive behavioral therapy and its models today, dialectical behavioral therapy, mindfulness therapy, cognitive therapy with both children and adults. The chapter establishes behavior therapy as the most ideal form of therapy in expressive arts therapy paradigm because it uses thinking to identify emotions, the feedback and reinforcement system of the brain motivates the brain muscles and instant creativity gives a sense of achievement. Making art can accelerate positive emotions because the drawing constantly awaits the maker to take next action, whether in a hopeful stroke or a stressful stroke, it produces an inner dialogue between a client and artwork.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Stress

What “is” stress? Draw on Lyons & Chamberlain’s chapter to reflect on the different ways of conceptualizing stress. Using an example, illustrate how each framing of stress would impact what stress is understood to be.

If you asked everybody what stress was to them it would be unlikely that you would get two answers the same. There is no one definite answer to what stress is, it is not an agreed-upon construct and will have different meanings depending on factors such as gender, culture, ideology, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity alongside a range of other contributing factors. Stress is a very complex construct that is understood, experienced, and coped with in varying ways. What is understood and works for one person that is stressed, will not be the same for another person. Before diving into the literature this week my understanding of stress was very basic, I had the general idea of what I thought stress was to me which involved increasing physical symptoms, a feeling of unease or unwellness, and also a tiny bit of prior knowledge of the more biological implications that it can influence the nervous system, immune system, and endocrine system. The main biological knowledge I had was relevant to the nervous system about the fight or flight response but this was very inadequate. From engaging with Lyons & Chamberlain’s chapter on stress I feel like I have a wealth of knowledge in comparison, and that it has enlightened me to how complex stress is and why there is so much debate surrounding it.

Lyons & Chamberlains note the complexity surrounding stress and investigate a wide range of framings that contribute to the constructs of stress. Firstly, a framing of stress can be seen to be interpreted in three ways, response, stimulus, and process. The response concept is what would be considered your immediate reaction, it is when the fight or flight process will activate telling you to either stay/fight or run/flight it is an internal cue. Which can have positive effects when you are in danger as the sympathetic nervous system is turned on which increases activity and arousal and diverts from other structures that don’t need the sustenance at that moment. However, this is only beneficial for a limited amount of time, because if you stay in this heightened state it can cause long-term adverse health effects. The second concept is stimulus, which is a reaction to something that is happening in the environment it is seen as an external cue, for instance, major life events, chronic circumstances, or even just daily hassles. Lastly, the concept of process is defined as the interaction between people and the environment and this is deemed neither internal nor external. Therefore, incorporating the transactional theory of stress into this concept that a response to stress will only occur if that certain stressor was seen as being a stressor to that particular individual, emphasizing once again that everyone encounters stress differently. I feel like this expanded well on the basic knowledge I already had about interactions involved with stress and gave me a deeper in-depth understanding.

Something I find so fascinating and engaging is the framing of the effects personality traits can have on an individual’s health relating to stress, as when first hearing this idea it seems a little out of the box. Even so, this chapter sheds some light on the dispositional influences and personality traits of optimism and pessimism and how they can impact health outcomes. Individuals who have more of an optimistic trait tend to have more social support, interpret issues positively and due to this experience, have less stress having a more positive correlation with health outcomes. On the other hand, pessimistic people don’t have the same social support, tend to look at issues more negatively, and can also have a negative outlook on the future incorporating more stressors in their lives which can be linked closely to disease progression. This is very relational to the symptoms topic as people are presenting with negative personality traits such as negative affectivity or neuroticism and this corresponds with over-reporting and feeling more sensations of symptoms, showing links between the physiological effects of the two and what negative influences can lead to.

In investigating this chapter there was a wide range of different research approaches taken, however, they seemed quite limiting and I don’t know if this is because stress is such a complex topic or if these limitations were methodical design. The first one that struck me was the stimulus concept where they used the social readjustment rating scale (SRRS), this scale rated certain life events on a positive and negative scale. The failings listed here were that younger people experience more of the life events than older people, which probably isn’t the case it is more so that this scale included major life events that were associated with younger age and didn’t counteract this by having major life events that would impact more on older age. Then reading further into the Lyons & Chamberlains chapter it mentioned the impact that optimism and pessimism have concerning stress, and couldn’t this impact the scale depending on which personality trait an individual leaned more towards too? It was also reiterated in both these topics and an immense number of others in this chapter that a lot of research was focused on white upper-class men, which makes the research not generalizable to any other population. This brings to mind why stress is so complex as for some reason we keep looking into the same population, where if we included female, trans-gender, different ethnic groups maybe we could close the gap a little on the complexity of it all and fill in some of the blanks.

Something very important that I have taken from engaging in the topic of stress is that it is different for everyone, everyone has different coping methods/strategies and we shouldn’t blame people for their stress. When I am stressed I like to exercise or play sport, this could be different for a range of individuals as even the thought of having to do exercise or play sport could be a stressor for them when it does the opposite for me. Furthermore, it is especially important to take consideration of all these factors as currently, we are in a pandemic where everyone is in a chronic state of stress, as there are unlimited unknowns in the present and future to come. This is a time where people need to band together and look out for one another, which links in with the other topic of stress and social buffering that has been explored in this course.

0 notes

Text

Trust Factors: Why Your Brand Should Take a Stand with Its Marketing Strategy

Earlier this year, Salesforce made waves by announcing a policy that compelled retailers to either stop selling military-style rifles and certain accessories, or stop using its popular e-commerce software. For a massive brand like this to take such an emphatic stand on a divisive social issue would’ve been unthinkable not so long ago. But in today’s world at large, and consequently in the business and marketing environments, it’s becoming more common. This owes to a variety of factors, ranging from generational changes among consumers to a growing need to differentiate. But, like so many other trends and strategies we see emerging in digital marketing, I think it mostly comes back to one overarching thing: the trust factor. In this installment of our Trust Factors series, we’ll explore why and how brands and corporations can take a stand on important issues, building trust and rapport with customers and potential buyers in the process.

The Business Case for Bold Stances

Executives from Salesforce might suggest that it made such a bold and provocative move simply because they felt it was the right thing to do. (CEO Marc Benioff, for instance, has been outspoken about gun control and specifically his opposition to the AR-15 rifle.) But of course, one of the 10 largest software companies in the world isn’t making these kinds of decisions without a considerable business case behind them. Like many other modern companies, Salesforce is taking the lead in a movement that feels inevitable. As millennials come to account for an increasingly large portion of the customer population, corporate social responsibility weighs more and more heavily on marketing strategies everywhere. A few data points to think about:

Research last year by FleishmanHillard found that 61% of survey respondents believe it’s important for companies to express their views, whether or not the person agrees with them.

Per the same study, 66% say they have stopped using the products and services of a company because the company’s response to an issue does not support their personal view.

The latest global Earned Brand Report from Edelman found that 64% of people are now “belief-driven buyers,” meaning they will choose, switch, avoid or boycott a brand based on its stand on societal issues.

MWWPR categorizes 35% of the adult population in the U.S. as “corpsumers,” up by two percentage points from the prior year. The term describes "a brand activist who considers a company's values, actions and reputation to be just as important as their product or service."

Corpsumers say they’re 90% more likely to patronize companies that take a stand on social and public policy matters, and 80% say they’ll even pay more for products from such brands.

(Source)

What Does It Mean to Take a Stand as a Brand?

Admittedly, the phrase is somewhat ambiguous. So let’s clear something up right now: taking a stand doesn’t necessarily mean your company needs to speak out on touchy political issues. When Dave Gerhart, Vice President of Marketing for Drift, gave a talk at B2BSMX last month outlining his 10 commandments for modern marketing, taking a stand was among the directives he implored. Gerhart pointed to Salesforce’s gun gambit as one precedent, but also called out a less controversial example: his own company’s crusade against the lead form. I think this serves as a great case in point. Lead forms aren’t a hot-button societal issue that’s going to rile people up, necessarily, but they’ve been a subject of annoyance on the consumer side for years. Drift’s decision to do away with them completely did entail some risk (to back up their stance, they had to commit to not using this proven, mainstream method for generating actionable leads) but made a big impression within their industry. Now, it’s a rallying cry for their brand. From my view, these are the trust-building ingredients, which both the Salesforce and Drift examples cover:

It has to matter to your customers

It has to be relevant to your industry or niche

It has to entail some sort of risk or chance-taking on behalf of the brand

Weighing that final item is the main sticking point for companies as they contemplate action on this front.

Mitigating the Risks of Taking a Stand

The potential downside of taking a controversial stand is obvious enough: “What if we piss off a bunch of our customers and our bottom line takes a hit?” Repelling certain customers is inherent to any bold stance, but obviously you’ll want the upside (i.e., affinity and loyalty built with current customers, plus positive attention drawing in new customers) to strongly outdistance the downside (i.e., existing or potential customers defecting because they disagree). Here are some things to think about on this front.

Know Your Audience and Employees

It’s always vital for marketers to have a deep understanding of the people they serve, and in this case it’s especially key. You’ll want to have a comprehensive grasp of the priorities and attitudes of people in your target audience to ensure that a majority will agree with — or at least tolerate — your positioning. Region, age, and other demographic factors can help you reach corollary conclusions. For example, our clients at Antea Group are adamant about the dangers of climate change. In certain circumstances this could (sadly) be a provocative and alienating message, but Antea Group serves leaders and companies focusing on sustainability, who widely recognize the reality and urgency of climate change. Not only that, but Antea Group also employs people who align with this vision, so embracing its importance both externally and internally leads to heightened engagement and award-winning culture. As another example, retailer Patagonia shook things up in late 2017 when it proclaimed on social media “The President Stole Your Land” after the Trump administration moved to reduce a pair of national monuments. In a way, this is potentially off-putting for the sizable chunk of its customer base that supports Trump, but given that Patagonia serves (and employs) an outdoorsy audience, the sentiment resonated and the company is thriving.

Know Your Industry and Competition

On the surface, Salesforce taking a public stand on gun control seems quite audacious. The Washington Post notes that retailers like Camping World, which figured to be affected by the new policy, are major customers for the platform. What if this drives them elsewhere? However, peer companies like Amazon and Shopify have their own gun restriction policies in place, so the move from Salesforce isn’t as “out there” as one might think. When you see your industry as a whole moving in a certain direction, it’s beneficial to get out front and position yourself as a leader rather than a follower.

Actions Speak Louder

Empty words are destined to backfire. Taking a stand is meaningless if you can’t back it up. Analysts warn that “goodwashing” is the new form of “greenwashing,” a term that refers to companies talking a big game on eco-friendly initiatives but failing to follow up with meaningful actions. According to MWWPR’s chief strategy officer Careen Winters (via AdWeek): “Companies that attempt to take a stand on issues but don’t really put their money where their mouth is, or what they are doing is not aligned with their track record and core values, will find themselves in a position where the corpsumers don’t believe them. Fifty-nine percent of corpsumers say they are skeptical about a brand’s motives for taking a stand on policy issues.”

Be Transparent and Authentic

One interesting aspect of the aforementioned FleishmanHillard study: 66% of respondents say they’ve stopped using the products and services of a company because the company’s response to an issue did not support their personal views; however another 43% say that if company explains WHY they have taken a position on an issue, the customer is extremely likely to keep supporting them.

(Source)

In other words, transparency is essential. If you fully explain the “why” behind a particular brand stance, you can score trust-building benefits with both those who do and do not agree.

Where We Stand at TopRank

At TopRank Marketing, we have a few stances that we openly advocate. One is gender equality; our CEO Lee Odden noticed many "top marketers" lists and editorial collaborations were crowded with men, so he (and we) have made it a point to highlight many of the women leading the way in our industry, both through our content projects and Lee's annual Women Who Rock Digital Marketing lists (10 years running!). Another is our commitment to serving a deeper purpose as a business. Of course we want to help our clients reach their business goals, but we also love working with virtuous brands that are improving the communities around them. We strive to also do so ourselves through frequent volunteering, donations to causes, and charitable team outings. These include packing food for the hungry, renovating yards for the homeless, and our upcoming Walk for Alzheimer's participation.

The Worst Stand You Can Take is Standing Still

Trust in marketing is growing more vital each day. It’s not enough to offer a great product or excellent customer service. Increasingly, customers want to do business with companies they like, trust, and align with. Those brands that sit on the sidelines regarding important issues are coming under greater scrutiny. Meanwhile, those with the guile to take bold but strategically sound stands are being rewarded. To learn more about navigating these waters without diminishing trust or eroding your brand’s credibility, take a look at our post on avoiding trust fractures through authenticity, purpose-driven decision-making, and a big-picture mindset. Or check out these other entries in our “Trust Factors” series:

The B2B Marketing Funnel is Dead: Say Hello to the Trust Funnel

Trust Factors: The (In)Credible Impact of B2B Influencer Marketing

Trust Factors: How Best Answer Content Fuels Brand Credibility

Tip of the Iceberg: A Story of Trust in Marketing as Told by Statistics

Be Like Honest Abe: How Content Marketers Can Build Trust Through Storytelling

The post Trust Factors: Why Your Brand Should Take a Stand with Its Marketing Strategy appeared first on Online Marketing Blog - TopRank®.

Trust Factors: Why Your Brand Should Take a Stand with Its Marketing Strategy published first on yhttps://improfitninja.blogspot.com/

0 notes

Text

Trust Factors: Why Your Brand Should Take a Stand with Its Marketing Strategy

Earlier this year, Salesforce made waves by announcing a policy that compelled retailers to either stop selling military-style rifles and certain accessories, or stop using its popular e-commerce software. For a massive brand like this to take such an emphatic stand on a divisive social issue would’ve been unthinkable not so long ago. But in today’s world at large, and consequently in the business and marketing environments, it’s becoming more common. This owes to a variety of factors, ranging from generational changes among consumers to a growing need to differentiate. But, like so many other trends and strategies we see emerging in digital marketing, I think it mostly comes back to one overarching thing: the trust factor. In this installment of our Trust Factors series, we’ll explore why and how brands and corporations can take a stand on important issues, building trust and rapport with customers and potential buyers in the process.

The Business Case for Bold Stances

Executives from Salesforce might suggest that it made such a bold and provocative move simply because they felt it was the right thing to do. (CEO Marc Benioff, for instance, has been outspoken about gun control and specifically his opposition to the AR-15 rifle.) But of course, one of the 10 largest software companies in the world isn’t making these kinds of decisions without a considerable business case behind them. Like many other modern companies, Salesforce is taking the lead in a movement that feels inevitable. As millennials come to account for an increasingly large portion of the customer population, corporate social responsibility weighs more and more heavily on marketing strategies everywhere. A few data points to think about:

Research last year by FleishmanHillard found that 61% of survey respondents believe it’s important for companies to express their views, whether or not the person agrees with them.

Per the same study, 66% say they have stopped using the products and services of a company because the company’s response to an issue does not support their personal view.

The latest global Earned Brand Report from Edelman found that 64% of people are now “belief-driven buyers,” meaning they will choose, switch, avoid or boycott a brand based on its stand on societal issues.

MWWPR categorizes 35% of the adult population in the U.S. as “corpsumers,” up by two percentage points from the prior year. The term describes "a brand activist who considers a company's values, actions and reputation to be just as important as their product or service."

Corpsumers say they’re 90% more likely to patronize companies that take a stand on social and public policy matters, and 80% say they’ll even pay more for products from such brands.

(Source)

What Does It Mean to Take a Stand as a Brand?

Admittedly, the phrase is somewhat ambiguous. So let’s clear something up right now: taking a stand doesn’t necessarily mean your company needs to speak out on touchy political issues. When Dave Gerhart, Vice President of Marketing for Drift, gave a talk at B2BSMX last month outlining his 10 commandments for modern marketing, taking a stand was among the directives he implored. Gerhart pointed to Salesforce’s gun gambit as one precedent, but also called out a less controversial example: his own company’s crusade against the lead form. I think this serves as a great case in point. Lead forms aren’t a hot-button societal issue that’s going to rile people up, necessarily, but they’ve been a subject of annoyance on the consumer side for years. Drift’s decision to do away with them completely did entail some risk (to back up their stance, they had to commit to not using this proven, mainstream method for generating actionable leads) but made a big impression within their industry. Now, it’s a rallying cry for their brand. From my view, these are the trust-building ingredients, which both the Salesforce and Drift examples cover:

It has to matter to your customers

It has to be relevant to your industry or niche

It has to entail some sort of risk or chance-taking on behalf of the brand

Weighing that final item is the main sticking point for companies as they contemplate action on this front.

Mitigating the Risks of Taking a Stand

The potential downside of taking a controversial stand is obvious enough: “What if we piss off a bunch of our customers and our bottom line takes a hit?” Repelling certain customers is inherent to any bold stance, but obviously you’ll want the upside (i.e., affinity and loyalty built with current customers, plus positive attention drawing in new customers) to strongly outdistance the downside (i.e., existing or potential customers defecting because they disagree). Here are some things to think about on this front.

Know Your Audience and Employees