#Marie de France

Text

Her beauty was great enough to excite

if not his desires in the night

his suspicions and jealousy.

Marie de France, Yonec

#Marie de France#The Lays of Marie de France#Yonec#beauty#feminine beauty#desire#suspicions#jealousy#French literature#medieval literature#poetry#poetry quotes#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

i fucking love the lais of marie de france. everyone else was like hurrrrrrr burrrrrrr arthurian mythology is about Hating The Saxons and marie was like ‘ok but what if it was about werewolves.’ fucking baller

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

And they say medieval literature isn't relevant to modern culture.

#marie de france#the lay of the were-wolf#the lay of the werewolf#the lays of marie de france#the lais of marie de france

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

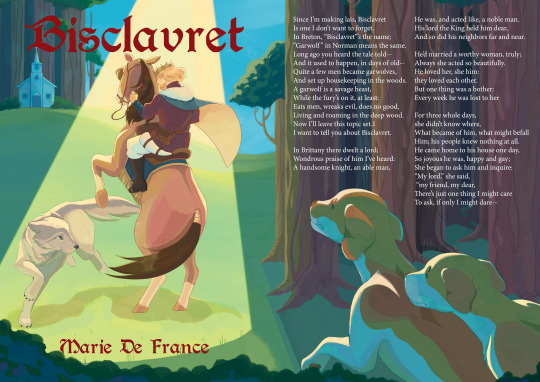

recent schoolwork, a spread for a werewolf story from the 1100s with big (unintentional) gay overtones that holds up really well and you should def go read

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

When four knights enter a tournament to win the same lady's hand (after she's led them all on), what could go wrong? Quite a lot, really. Join us in this episode as we explore this soap opera of a reverse-harem, medieval style. Plus, we discuss how medieval tournaments were actually set up, and how to adapt them to your D&D campaign!

Join our discord community! Check out our Tumblr for even more! Support us on patreon! Check out our merch!

Socials: Tumblr Website Twitter Instagram Facebook

Citations & References:

The Lais of Marie de France

The Medieval Tournament as Spectacle: Tourneys, Jousts and Pas d'Armes, 1100-1600

Tournament rules

The Medieval Tournament: A Functional Sport of the Upper Class

Our very own blog post!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lais, Marie de France, around 1165.

I finished reading those last week. Marie de France is the first poet known to have written in vernacular french. We know very little about her and her life. Even her presence at the court of Henry II of England seems to remain uncertain.

The Lais are short stories in old French, inspired by the tales of Breton minstrels. They are about love rather than adventure : it's a light reading, fun at times and touching all over.

Concisely written, it's easy to tell the Lais were meant to be read out loud. Sadly, I read those in modern french (old french is much harder to read than I first thought) and the "translation" lost the rhyming, therefore a part of the beauty of the Lais.

#bookblr#book#books#book review#booklr#book rec#book recommendation#book reviews#reading suggestions#reading journal#marie de france#lais#french literature#french#french books#do reads

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gay medieval shenanigans:

This is from The Quest for the Holy Grail by Chrétien de Troyes, translated by David Staines:

When [Percival] did see [the knights] in the open without the woods concealing them, and noticed the jingling hauberks and the bright shining helmets, and beheld the green and the scarlet and the gold and the azure and the silver gleaming in the sun, he found everything most noble and beautiful. [...] "Here I behold the Lord God, I believe, for one of them is so beautiful to behold that the others, so help me God, have not a tenth of his beauty."

[...]

They stopped and he [the knight] galloped toward the young man. Greeting him reassuringly, he said: "Youth, have no fear."

"By the Savior I believe in, I have none," the young man answered. "Are you God?"

"No, I swear"

"Who are you then?"

"I am a knight."

"I never knew a knight before, and never saw one or heard talk of one," the young man said. "But you are more beautiful than God. I wish I were like you, so sparkling and so formed."

TL;DR: Percival sees a knight for the first time, and thinks he's so pretty that when the knight comes up to talk to him, the first thing Percival says is, "Are you God?"

That's maybe the gayest thing I've read in medieval literature so far. And I've read this:

There on the king's bed, they could see

asleep, the knight. How the king ran

up to the bed, to embrace this man,

kiss him, a hundred times and more!

--Marie de France, "Bisclavret"

Also @prokopetz was right, the real deal is Monty-Python-levels of weird and funny.

#i know the point is that percival is just enamored with the idea of knighthood#but i mean come on#he thinks the knight is so freaking gorgeous that he must be god#i'll take things straight men don't say for 200 alex#medieval#medieval romances#medieval studies#medieval romance#arthurian#arthurian legend#percival#knights#the knights of the round table#the knights of camelot#medieval literature#lgbtq#lgbtq history#lgbtq literature#queer reading#arthuriana#bisclavret#marie de france#gay literature

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It sure has taken me a long time to notice that despite Marie de France assuring us that Bisclavret is a Breton lai, Brittany didn't actually... have a king... at any point during its status as a united independent territory. It was a duchy, so it had a duke.

Presumably, then, Bisclavret either takes place in an alternate universe in which Brittany was a kingdom, or it is a Breton lai that does not take place in Brittany, or it takes place in the sufficiently distant past that it's set in, like, the eighth century and you've still got lots of little warring kingdoms to deal with, prior to its ninth century unification as a duchy. (Or it's not Breton at all – entirely possible, but the distinction drawn between the Breton and Norman terms 'bisclavret' and 'garwaf' does imply a Breton setting, origin, or connection of some sort.)

I realise this story involves a werewolf and therefore historical fact is not its priority, but when you're trying to determine the exact status of a baron, it helps to know whether you do in fact have a king or not, so now I am a little stuck.

#i assume in her use of the term baron and king she is imposing some norman ideals on the story#bisclavret#medieval#marie de france

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen of Knives (I don't have my own copy of Smoke and Mirrors with me and didn't find a link)

Mahabharata

Paul Revere's Ride

Bisclavret

The Waste Land

The Cremation of Sam McGee

The Raven

Divine Comedy

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Okay so I still have a few names (notably Robert Frost, Edgar Allan Poe, Lewis Carroll and John Milton) in mind for at least another poll, maybe two or even three if you make suggestions. Thank you for the ones you've already made, by the way ! (I favor the lay of the Honeysuckle but it'll go in another poll just as the Shooting of Dan McGrew)

Yes I know this one is difficult too. Good luck.

My tag for this series is 'narrative poems'. Other poetry polls in my 'poetry' tag.

#polls#narrative poems#poetry#mahabharata#vyasa#queen of knives#neil gaiman#paul revere's ride#henry wadsworth longfellow#the werewolf#biclavret#biclavaret#marie de france#the waste land#t.s. eliot#the cremation of sam mcgee#robert service#the raven#edgar allan poe#divine comedy#dante alighieri#the rime of the ancient mariner#samuel taylor coleridge

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Werewolf Fact #67 - The Lai of the Werewolf, “Bisclavret”

The time has come to discuss in depth my very favorite werewolf story! Yes, my favorite werewolf story doesn't come from modern pop culture. Instead, it comes from medieval literature.

So let's dive right into "Bisclavret," one of the best werewolf stories ever told.

Please note that this post will contain the entirety of “Bisclavret,” in direct quotes, with my discussions interspersed throughout. So if you’ve never read the story, you can find the whole thing here!

The Van Helsing werewolf never fails to bring in some attention, so here he is again in spite of irrelevance. But hey, he's a werewolf, so... it works! Right?

Moving right along--

For this in-depth look at "Bisclavret," I will be using A Lycanthropy Reader: Werewolves in Western Culture by Charlotte F. Otten, one of my very favorite werewolf sourcebooks. It's a wonderful collection of primary historical sources - and some stories that aren't folklore but were always considered fictional - and some very good introductions to and discussions of said works by Otten herself.

In fact, in her introduction to the section that includes "Bisclavret," Otten imparts some very wise words on werewolf legends as a whole...

On the moral level, the werewolf myth is a realistic assessment of the range of choices available to human beings. Humans who become werewolves in the myths and legends, or who cause others to become werewolves, are involved in moral metamorphosis: a process that recognizes the exhilaration that comes with engaging in degrading lycanthropic acts but also reveals the degradation that comes to those who deliberately choose to exhibit bestiality [bestial nature]. The werewolf myth, then, is a profound insight into human life. ... Regarded as a moral myth, the presence in the human spirit of werewolves can direct the culture, the society, the individual human being to sources of healing. If it does so, it is a myth not of despair but of hope. (Otten 223)

I would personally add, also in relation to “Bisclavret,” that it isn’t only those who become werewolves and behave as beasts or those who turn others into werewolves - it’s also extremely important in many werewolf myths how the werewolves themselves are treated by the human characters. How one treats a werewolf, with that person still being human but in the guise of a beast, is an important moral plot point in multiple werewolf legends, such as the werewolves of Ossory and - of course - Bisclavret. One is amoral if they assume a werewolf is evil solely because of their appearance, without judging their character first and appearance second. It’s not necessarily always a test of the werewolf character, it’s also a test of everyone around them. If the werewolf is virtuous and behaving like a human, isn’t it just as important to treat the werewolf like you would anyone else - even if it is a werewolf?

Now let's get to Bisclavret...

Written in the 12th century, “Bisclavret” is a bit of an enigma. Scholars kind of agree that it was likely written by Marie de France, or else a story she adapted from a much older tale, given there are different versions of this story - all very similar - floating around from similar time periods and cultures.

Marie de France herself says she translated this lai out of the Breton language, after having heard it elsewhere. I’m glad she did, as she preserved a fantastic werewolf story.

“Bisclavret” opens with some words from Marie de France...

Amongst the tales I will tell you once again, I would not forget the Lay of the Were-Wolf. Such beasts as he are known in every land. Bisclavaret he is named in Brittany, whilst the Norman calls him Garwal. (256)

I find her discussion of werewolf terminology interesting. She goes on to introduce the concept of werewolves themselves, which is, as she discusses it, a very commonly-known concept and found “in every land,” which she is absolutely right about (even if, of course, these legends weren’t always the same in nature, but werewolves certainly were everywhere).

It is a certain thing, and within the knowledge of all, that many a christened man has suffered this change, and ran wild in woods, as a Were-Wolf. The Were-Wolf is a fearsome beast. He lurks within the thick forest, mad and horrible to see. All the evil that he may, he does. He goeth to and fro, about the solitary place, seeking man, in order to devour him. Hearken, now, to the adventure of the Were-Wolf, that I have to tell. (256)

This doesn’t sound at all like Bisclavret, as you will discover. Marie de France seems to be describing a certain interpretation of the werewolf myth that didn’t even all that often apply but was steadily becoming a more accepted concept, especially in certain regions of Europe: that werewolves are “evil.” Or, at least - and most importantly - she states that werewolves are perceived as evil.

But are they really? Let’s read Bisclavret and find out. Because this opening displays the way the werewolf myth exists in the minds of many, but not necessarily the way werewolves really are, and I think that’s an important element of the story: Marie de France doesn’t open with “werewolves are all nice and cuddly,” because you need to read the story and determine the truth for yourself. But now you see the general perception, at least as this story presents it.

I love werewolves so much, you guys. I love this story, too. That’s something I have trouble conveying sometimes to my good readers: I love the concept of werewolves and I could talk about them until the sun dies. I love even the simplest presentations of “a werewolf is a man who suffers a change and runs wild in the darkest wood, horrible to behold, and devours men.” I just love it beyond words or reason. This is what I want. This is all I ask for. This but with more behind it than the simplicity of “evil,” just like Bisclavret presents.

Anyway!

So now we are introduced to our protagonist...

In Brittany there dwelt a baron who was marvellously esteemed of all his fellows. He was a stout knight, and a comely, and a man of office and repute. Right private was he to the mind of his lord, and dear to the counsel of his neighbours. This baron was wedded to a very worthy dame, right fair to see, and sweet of semblance. All his love was set on her, and all her love was given again to him. One only grief had this lady. For three whole days in every week her lord was absent from her side. She knew not where he went, nor on what errand. Neither did any of his house know the business which called him forth.

On a day when this lord was come again to his house, altogether joyous and content, the lady took him to task, right sweetly, in this fashion,

“Husband,” said she, “and fair, sweet friend, I have a certain thing to pray of you. Right willingly would I receive this gift, but I fear to anger you in the asking. It is better for me to have an empty hand, than to gain hard words.”

When the lord heard this matter, he took the lady in his arms, very tenderly, and kissed her.

“Wife,” he answered, “ask what you will. What would you have, for it is yours already?”

“By my faith,” said the lady, “soon shall I be whole. Husband, right long and wearisome are the days that you spend away from your home. I rise from my bed in the morning, sick at heart, I know not why. So fearful am I, lest you do aught to your loss, that I may not find any comfort. Very quickly shall I die for reason of my dread. Tell me now, where you go, and on what business! How may the knowledge of one who loves so closely, bring you to harm?”

This old tale is... very good at conveying someone manipulative and self-serving and even goes so far as to show her turn to other victims to use: this isn’t just a werewolf story, it’s a tale about manipulation*. Poor Bisclavret gets burned just for trusting the person who claims to love him so. It’s sad and relatable to see. A tale as old as time, and not the nice one that is “Beauty and the Beast.”

But being a werewolf is still a very bad thing, as established by the story’s opening! Naturally, he doesn’t want to tell.

“Wife,” made answer the lord, “nothing but evil can come if I tell you this secret. For the mercy of God do not require it of me. If you but knew, you would withdraw yourself from my love, and I should be lost indeed.”

When the lady heard this, she was persuaded that her baron sought to put her by with jesting words. Therefore she prayed and required him the more urgently, with tender looks and speech, till he was overborne, and told her all the story, hiding naught.

Now we’re back to that manipulation... anyway.

“Wife, I become Bisclaravet. I enter the forest, and live on prey and roots, within the thickest of the wood.”

This marks a difference with the opening already. The baron here claims he doesn’t eat human flesh! The opening clearly stated werewolves do evil and seek to devour men. Hmm, interesting.

After she had learned his secret, she prayed and entreated the more as to whether he ran in his raiment, or went spoiled of vesture.

“Wife,” said he, “I go naked as a beast.”

“Tell me, for hope of grace, what do you do with your clothing?”

“Fair wife, that I will never. If I should lose my raiment, or even be marked as I quit my vesture, then a Were-Wolf I must go for all the days of my life. Never again should I become man, save in that hour my clothing were given back to me. For this reason never will I show my lair.”

“Husband,” replied the lady to him, “I love you better than all the world. The less cause have you for doubting my faith, or hiding any tittle from me. What savour is here of friendship? How have I made forfeit of your love, for what sin do you mistrust my honor? Open now your heart, and tell what is good to be known.”

So at the end, outwearied and overborne by her importunity, he could no longer refrain, but told her all.

“Wife,” said he, “within this wood, a little from the path, there is a hidden way, and at the end thereof an ancient chapel, where often-times I have bewailed my lot. Near by is a great hollow stone, concealed by a bush, and there is the secret place where I hide my raiment, till I would return to my own home.”

The baron says he “often-times ... bewail[s] his lot,” so he clearly doesn’t like being a werewolf. Just a small detail to point out. Truly the original classic werewolf hero.

On hearing this marvel the lady became sanguine of visage, because of her exceeding fear. She dared no longer to lie at his side, and turned over in her mind, this way and that, how best she could get her from him. Now there was a certain knight of those parts, who, for a great while, had sought and required this lady of her love. This knight had spend long years in her service, but little enough had he got thereby, not even fair words, or a promise. To him the dame wrote a letter, and meeting, made her purpose plain.

So not only did learning that the baron, her own husband, is a werewolf make this manipulative selfish woman turn on him instantly, but she also turned to a knight who is utterly failing his chivalric code and wanting love from this woman instead of courtly, chaste love from afar. And he’s probably too love-struck to realize she’s just going to use him until he is no longer beneficial to her in her own eyes, like she just did with the baron. We have a very bad combination.

“Fair friend,” said she, “be happy. That which you have coveted so long a time, I will grant without delay. Never again will I deny your suit. My heart, and all I have to give, are yours, so take me now as love and dame.”

Right sweetly the knight thanked her for her grace, and pledged her faith and fealty. When she had confirmed him by an oath, then she told him of his business of her lord--why he went, and what he became, and of his ravening within the wood. So she showed him of the chapel, and of the hollow stone, and of how to spoil the Were-Wolf of his vesture. Thus, by the kiss of his wife, was Bisclavaret betrayed. Often enough had he ravished his prey in desolate places, but from this journey he never returned. His kinsfolk and acquaintance came together to ask of his tidings, when this absence was noised abroad. Many a man, on many a day, searched the woodland, but none might find him, nor learn where Bisclavaret was gone.

The lady was wedded to the knight who had cherished her for so long a space. More than a year had passed since Bisclavaret disappeared. Then it chanced that the King would hunt in the self-same wood where the Were-Wolf lurked. When the hounds were unleashed they ran this way and that, and swiftly came upon his scent. At the view the huntsman winded on his horn, and the whole pack were at his heels. They followed him from morn to eve, till he was torn and bleeding, and was all adread lest they should pull him down. Now the King was very close to the quarry, and when Bisclavaret looked upon his master, he ran to him for pity and for grace. He took the stirrup within his paws, and fawned upon the prince’s foot. The King was very fearful at this sight, but presently he called his courtiers to his aid.

This scene very clearly points out, yet again, that the baron Bisclavret takes the shape of a wolf when he assumes his werewolf form. This is not uncommon in werewolf legends.

“Lords,” cried he, “hasten hither, and see this marvellous thing. Here is a beast who has the sense of a man. He abases himself before his foe, and cries for mercy, although he cannot speak. Beat off the hounds, and let no man do him harm. We will hunt no more to-day, but return to our own place, with the wonderful quarry we have taken.”

The King turned him about, and rode to his hall, Bisclavaret following at his side. Very near to his master the Were-Wolf went, like any dog, and had no care to seek again the wood. When the King had brought him safely to his own castle, he rejoiced greatly, for the beast was fair and strong, no mightier had any man seen.

Another pause here to point out that, once again, a werewolf that turns into a wolf is never conveyed as being an ordinary wolf - they are always bigger, stronger, “mightier.” Indeed, they are always the most impressive thing people have witnessed.

Much pride had the King in his marvellous beast. He held him so dear, that he bade all those who wished for his live, to cross the Wolf in naught, neither to strike him with a rod, but ever to see that he was richly fed and kennelled warm. This commandment the Court observed willingly. So all day the wolf sported with the lords, and at night he lay within the chamber of the King. There was not a man who did not make much of the beast, so frank was he and debonair. None had reason to do him wrong, for ever was he about his master, and for his part did evil to none. Every day were these two companions together, and all perceived that the King loved him as his friend.

What a great section. Already friends before, now the baron and his King are friends again, even if he has taken the form of a beast and cannot speak. Even in werewolf form, he acts as a loyal knight and bodyguard, with the king giving him full trust of his life despite him being a beast. This speaks volumes about werewolf intelligence in folklore, as well, as he is clearly just as intelligent as he always was. I love the emphasis on Bisclavret’s courtly mannerisms and his culture, and even the emphasis that he does not do “evil,” also in direct contradiction to the assumptions the story’s opening would lead you to believe. But things are about to change...

Hearken now to that which chanced.

The King held a high Court, and bade his great vassals and barons, and all the lords of his venery to the feast. Never was there a goodlier feast, nor one set for with sweeter show and pomp. Amongst those who were bidden, came that same knight who had the wife of Bisclavaret for dame. He came to the castle, richly gowned, with a fair company, but little he deemed whom he would find so near. Bisclavaret marked his foe the moment he stood within the hall. He ran towards him, and seized him with his fangs, in the King’s very presence, and to the view of all. Doubtless he would have done him much mischief, had not the King called and chidden him, and threatened him with a rod. Once, and twice, again, the Wolf set upon the knight in the very light of day. All men marvelled at his malice, for sweet and serviceable was the beast, and to that hour had shown hatred of none. With one consent the household deemed that this deed was done with full reason, and that the Wolf had suffered at the knight’s hand some bitter wrong. Right wary of his foe was the knight until the feast had ended, and all the barons had taken farewell of their lord, and departed, each to his own house. Wit hthese, amongst the very first, wen that lord whom Bisclavaret so fiercely had assailed. Small was the wonder he was glad to go.

Bisclavret at last shows a werewolf’s rage - but only in a righteous way. He only attacks the one who wronged him. So what does the King make of his new beast of a friend behaving in such a way? Does he have him killed? Does he decide he’s a monster?

Not long while after this adventure it came to pass that the courteous King would hunt in that forest where Bisclavaret was found. With the prince came his wolf, and a fair company. Now at nightfall the King abode within a certain lodge of that country, and this was known of that dame who before was the wife of Bisclavaret. In the morning the lady clothed her in her most dainty apparel, and hastened to the lodge, since she desired to speak with the King, and to offer him a rich present.

Also typical manipulative behavior. You may think of medieval tales as simple, but they had a lot to say and to teach.

When the lady entered in the chamber, neither man no leash might restrain the fury of the Wolf. He became as a mad dog in his hatred and malice. Breaking from his bonds he sprang at the lady’s face, and bit the nose from her visage.

Please note that this is a medieval trope, as it were: the removal of the nose. It’s quite a lot to break down. But let’s maintain focus on the werewolf...

From every side men ran to the succour of the dame. They beat off the wolf from his prey, and for a little would have cut him to pieces with their swords. But a certain wise consellor said to the King,

“Sire, hearken now to me. This beast is always with you, and there is not one of us all who has not known him for long. He goes in and out amongst us, nor has molested any man, neither done wrong or felony to any, save only to this dame, one only time as we have seen. He has done evil to this lady, and to that knight, who is now the husband of the dame. Sire, she was once the wife of that lord who was so close and private to your heart, but who went, and none might find where he had gone. Now, therefore, put the dame in a sure place, and question her straitly, so that she may tell--if perchance she knows thereof-- for what reason this Beast holds her in such mortal hate. For many a strange deed has chanced, as well we know, in this marvellous land of Brittany.”

Smart man! This paragraph also serves to highlight that the King and the knight/baron Bisclavret were already friends before and - I’m sure - trusted companions, as kings and their knights generally tend to be, especially in stories. After all, there are tales very similar to Bisclavret as told in King Arthur stories about one of his knights of the Round Table, his most trusted brothers-in-arms. It is no different here, as Bisclavret was once a brother to this king, if also subservient to his lord in rank - which, in this time period and in such tales, generally served to make the bond of brotherhood and honorable oaths still stronger.

The counsellor also points out about “many a strange deed” and is apparently talking about werewolves. This is the first time someone suggests that the Wolf may actually be a man.

The King listened to these words, and deemed the counsel good. He laid hands upon the knight, and put the dame in surety in another place. He caused them to be questioned right straitly, so that their torment was very grevious. At the end, partly because of her distress, and partly by reason of her exceeding fear, the lady’s lips were loosed, and she told her tale. She showed them of the betrayal of her lord, and how his raiment was stolen from the hollow stone. Since then she knew not where he went, nor what had befallen him, for he had never come again to his own land. Only, in her heart, well she deemed and was persuaded, that Bisclavaret was he.

Straightaway the King demanded the vesture of his baron, whether this were to the wish of the lady, or whether it were against her wish. When the raiment was brought to him, he caused it to be spread before Bisclavaret, but the Wolf made as though he had not seen. Then that cunning and crafty counsellor took the King apart, that he might give him a fresh rede.

Well, obviously, Bisclavret isn’t too keen on turning back into a human right in front of everyone. I appreciate this aspect. Returning to the shape of a man is no small and simple feat, and it’s a shameful and degrading process both to do it and to have the truth of his nature known - not to mention it might be difficult, especially after being in the form of a beast for so long. This is then highlighted by the counsellor...

“Sire,” said he [the counsellor], “you do not wisely, nor well, to set this raiment before Bisclavaret, in the sight of all. In shame and much tribulation must he lay aside the beast, and again become man. Carry our wolf within your most secret chamber, and put his vestment therein. Then close the door upon him, and leave him alone for a space. So we shall see presently whether the ravening beast may indeed return to human shape.”

The King carried the Wolf to his chamber, and shut the doors upon him fast. He delayed for a brief while, and taking two lords of his fellowship with him, came again to the room.

I guess the king was a little worried about what he might find! Can’t really blame him.

Entering therein, all three, softly together, they found the knight sleeping in the King’s bed, like a little child. The King ran swiftly to the bed and taking his friend in his arms, embraced and kissed him fondly, above a hundred times.

The king is clearly a big fan of la bise, and since he hasn’t seen the knight for so long, he has to make up for all those lost greetings. It’d be a great scene for a cartoon, honestly. Kissing meant a wider variety of things in this time period than it often does today: a kiss could be greeting, respect, forgiveness, or even a sign of peace, rather than some simple blanket gesture of romantic love, as it is thought of today. The king does a lot of talking when he greets the knight in such a way, telling him that he is welcomed back and that he’s happy to see him and all is forgiven. So... no punishment for being a werewolf!

When man’s speech returned once more [to the knight/Bisclavret], he told him [the King] of his adventure. Then the King restored his friend the fief that was stolen from him, and gave such rich gifts, moreover, as I cannot tell. As for the wife who had betrayed Bisclavaret, he bade her avoid his country, and chased her from the realm. So she went forth, she and her second lord together, to seek a more abiding city, and were no more seen.

The adventure that you have heard is no vain fable. Verily and indeed it chanced as I have said. The Lay of the Were-Wolf, truly, was written that it should ever be borne in mind.

No “the evil werewolf must die,” no mention of his curse or passing it on to others - the werewolf is a hero and is accepted as one in spite of his bestial transformation. Truly an interesting specimen among werewolf tales.

*: Yes, this aspect of the story is indeed often interpreted as negative against women, but that isn’t something I will get into with this post. I will instead be viewing it as a werewolf legend and not criticizing other aspects. It’s true that women were often viewed and treated unfairly in this time period and generally made out to be evil manipulative creatures in many medieval tales (though not all, and not all the female characters always were), as that was often the mindset of this time period, but that’s an issue for another time and another blog, as this blog is about werewolves. I did, however, want to acknowledge that issue, because I’m quite aware of it (especially as a woman in medieval studies), instead of ignoring it altogether. I personally do not think it lessens the story or makes the moral any less powerful, especially if we recognize the biases of the time period - and that a woman chose, herself, to retell this story in the first place, as I too am a woman choosing to retell it now.

I do so deeply enjoy “Bisclavret” and the truly classical tale of deepest fealty and trust to one’s King, the humanity displayed by the “wolf” (werewolf), and even how the King is thankful to have the faithful baron returned to human form - with no question or horror to learn that he was a werewolf to begin with.

The relationship between lord and knight is something not often conveyed in modern culture, as it’s not really something we have anymore, so it’s always fun to read about in such a fantastical sense. And many medieval stories are about courtly love, but not so with this one. Don’t get me wrong, I love courtly love, but it’s fun to see a platonic story as well.

So there we have it, the tale of “Bisclavret”! It’s one of my favorite werewolf stories. It’s classic, it’s simple, and it’s about a good and chivalrous, courtly knight werewolf. As we all know... I do love the idea of a werewolf knight.

Until next time!

(If you like my werewolf blog, be sure to follow me here and check out my other stuff! Please consider supporting me on Patreon or donating on Ko-fi if you’d like to see me continue my works. Every little bit helps so much.

Patreon — Ko-fi — Wulfgard — Werewolf Fact Masterlist — Twitter — Vampire Fact Masterlist )

#werewolf#werewolves#werewolf fact#werewolf wednesday#werewolfwednesday#werewolf facts#folklore#folklore facts#medieval history#middle ages#literature#medieval literature#knights#lais#marie de france#folklore fact#bisclavret#the lai of the werewolf#lays

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Griesly Wife (John Manifold)

"A poem in which an abusive husband chases his new wife through the snow -- until she changes into a beast and turns the tables on him."

Bisclavret (Marie de France)

"Covers several common themes of the Hunt -- loyalty, betrayal, and werewolves. Bisclaveret is a werewolf trapped in his lupine form by his wife's treachery, and is hunted by his king, who does not know his identity, until he is cleverly able to turn the tables on his ex-wife"

#hunt poll#the hunt#poll#the magnus archives#leitner tournament#The Griesly Wife#Bisclavret#Marie de France

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Lay of Yonec

by Marie de France, translated by Eugene Mason

@ariel-seagull-wings @princesssarisa @adarkrainbow

In fairy tales there is this type of story where a prince that can shapeshifts into a bird visits a young maiden locked in a tower and makes love with her. Madame d'Aulnoy’s The Blue Bird, possibly the origin of the term Prince Charming or Le roi Charmant as he was originally called, is one of these tales.

In my research I found this charming and bittersweet tale among the lais of Marie de France. Lays or lais are narrative or lyrical poems, usually in octosyllabic couplets, intended to be sung from medieval Breton literature that deal with courtly love and chivalric deeds, often involving supernatural fairy elements. They are like the link between chivalric romances and fairy tales.

Since I have commenced I would not leave any of these Lays untold. The stories that I know I would tell you forthwith. My hope is now to rehearse to you the story of Yonec, the son of Eudemarec, his mother's first born child.

In days of yore there lived in Britain a rich man, old and full of years, who was lord of the town and realm of Chepstow. This town is builded on the banks of the Douglas, and is renowned by reason of many ancient sorrows which have there befallen. When he was well stricken in years this lord took to himself a wife, that he might have children to come after him in his goodly heritage. The damsel, who was bestowed on this wealthy lord, came of an honourable house, and was kind and courteous, and passing fair. She was beloved by all because of her beauty, and none was more sweetly spoken of from Chepstow to Lincoln, yea, or from there to Ireland. Great was their sin who married the maiden to this agèd man. Since she was young and gay, he shut her fast within his tower, that he might the easier keep her to himself. He set in charge of the damsel his elder sister, a widow, to hold her more surely in ward. These two ladies dwelt alone in the tower, together with their women, in a chamber by themselves. There the damsel might have speech of none, except at the bidding of the ancient dame. More than seven years passed in this fashion. The lady had no children for her solace, and she never went forth from the castle to greet her kinsfolk and her friends. Her husband's jealousy was such that when she sought her bed, no chamberlain or usher was permitted in her chamber to light the candles. The lady became passing heavy. She spent her days in sighs and tears. Her loveliness began to fail, for she gave no thought to her person. Indeed at times she hated the very shadow of that beauty which had spoiled all her life.

Now when April had come with the gladness of the birds, this lord rose early on a day to take his pleasure in the woods. He bade his sister to rise from her bed to make the doors fast behind him. She did his will, and going apart, commenced to read the psalter that she carried in her hand. The lady awoke, and shamed the brightness of the sun with her tears. She saw that the old woman was gone forth from the chamber, so she made her complaint without fear of being overheard.

"Alas," said she, "in an ill hour was I born. My lot is hard to be shut in this tower, never to go out till I am carried to my grave. Of whom is this jealous lord fearful that he holds me so fast in prison? Great is a man's folly always to have it in mind that he may be deceived. I cannot go to church, nor hearken to the service of God. If I might talk to folk, or have a little pleasure in my life, I should show the more tenderness to my husband, as is my wish. Very greatly are my parents and my kin to blame for giving me to this jealous old man, and making us one flesh. I cannot even look to become a widow, for he will never die. In place of the waters of baptism, certainly he was plunged in the flood of the Styx. His nerves are like iron, and his veins quick with blood as those of a young man. Often have I heard that in years gone by things chanced to the sad, which brought their sorrows to an end. A knight would meet with a maiden, fresh and fair to his desire. Damsels took to themselves lovers, discreet and brave, and were blamed of none. Moreover since these ladies were not seen of any, except their friends, who was there to count them blameworthy! Perchance I deceive myself, and in spite of all the tales, such adventures happened to none. Ah, if only the mighty God would but shape the world to my wish!"

When the lady had made her plaint, as you have known, the shadow of a great bird darkened the narrow window, so that she marvelled what it might mean. This falcon flew straightway into the chamber, jessed and hooded from the glove, and came where the dame was seated. Whilst the lady yet wondered upon him, the tercel became a young and comely knight before her eyes. The lady marvelled exceedingly at this sorcery. Her blood turned to water within her, and because of her dread she hid her face in her hands. By reason of his courtesy the knight first sought to persuade her to put away her fears.

"Lady," said he, "be not so fearful. To you this hawk shall be as gentle as a dove. If you will listen to my words I will strive to make plain what may now be dark. I have come in this shape to your tower that I may pray you of your tenderness to make of me your friend. I have loved you for long, and in my heart have esteemed your love above anything in the world. Save for you I have never desired wife or maid, and I shall find no other woman desirable, until I die. I should have sought you before, but I might not come, nor even leave my own realm, till you called me in your need. Lady, in charity, take me as your friend."

The lady took heart and courage whilst she hearkened to these words. Presently she uncovered her face, and made answer. She said that perchance she would be willing to give him again his hope, if only she had assurance of his faith in God. This she said because of her fear, but in her heart she loved him already by reason of his great beauty. Never in her life had she beheld so goodly a youth, nor a knight more fair.

"Lady," he replied, "you ask rightly. For nothing that man can give would I have you doubt my faith and affiance. I believe truly in God, the Maker of all, who redeemed us from the woe brought on us by our father Adam, in the eating of that bitter fruit. This God is and was and ever shall be the life and light of us poor sinful men. If you still give no credence to my word, ask for your chaplain; tell him that since you are sick you greatly desire to hear the Service appointed by God to heal the sinner of his wound. I will take your semblance, and receive the Body of the Lord. You will thus be certified of my faith, and never have reason to mistrust me more."

When the sister of that ancient lord returned from her prayers to the chamber, she found that the lady was awake. She told her that since it was time to get her from bed, she would make ready her vesture. The lady made answer that she was sick, and begged her to warn the chaplain, for greatly she feared that she might die. The aged dame replied,

"You must endure as best you may, for my lord has gone to the woods, and none will enter in the tower, save me."

Right distressed was the lady to hear these words. She called a woman's wiles to her aid, and made seeming to swoon upon her bed. This was seen by the sister of her lord, and much was she dismayed. She set wide the doors of the chamber, and summoned the priest. The chaplain came as quickly as he was able, carrying with him the Lord's Body. The knight received the Gift, and drank of the Wine of that chalice; then the priest went his way, and the old woman made fast the door behind him.

The knight and the lady were greatly at their ease; a comelier and a blither pair were never seen. They had much to tell one to the other, but the hours passed till it was time for the knight to go again to his own realm. He prayed the dame to give him leave to depart, and she sweetly granted his prayer, yet so only that he promised to return often to her side.

"Lady," he made answer, "so you please to require me at any hour, you may be sure that I shall hasten at your pleasure. But I beg you to observe such measure in the matter, that none may do us wrong. This old woman will spy upon us night and day, and if she observes our friendship, will certainly show it to her lord. Should this evil come upon us, for both it means separation, and for me, most surely, death."

The knight returned to his realm, leaving behind him the happiest lady in the land. On the morrow she rose sound and well, and went lightly through the week. She took such heed to her person, that her former beauty came to her again. The tower that she was wont to hate as her prison, became to her now as a pleasant lodging, that she would not leave for any abode and garden on earth. There she could see her friend at will, when once her lord had gone forth from the chamber. Early and late, at morn and eve, the lovers met together. God grant her joy was long, against the evil day that came.

The husband of the lady presently took notice of the change in his wife's fashion and person. He was troubled in his soul, and misdoubting his sister, took her apart to reason with her on a day. He told her of his wonder that his dame arrayed her so sweetly, and inquired what this should mean. The crone answered that she knew no more than he, "for we have very little speech one with another. She sees neither kin nor friend; but, now, she seems quite content to remain alone in her chamber."

The husband made reply,

"Doubtless she is content, and well content. But by my faith, we must do all we may to discover the cause. Hearken to me. Some morning when I have risen from bed, and you have shut the doors upon me, make pretence to go forth, and let her think herself alone. You must hide yourself in a privy place, where you can both hear and see. We shall then learn the secret of this new found joy."

Having devised this snare the twain went their ways. Alas, for those who were innocent of their counsel, and whose feet would soon be tangled in the net.

Three days after, this husband pretended to go forth from his house. He told his wife that the King had bidden him by letters to his Court, but that he should return speedily. He went from the chamber, making fast the door. His sister arose from her bed, and hid behind her curtains, where she might see and hear what so greedily she desired to know. The lady could not sleep, so fervently she wished for her friend. The knight came at her call, but he might not tarry, nor cherish her more than one single hour. Great was the joy between them, both in word and tenderness, till he could no longer stay.

All this the crone saw with her eyes, and stored in her heart. She watched the fashion in which he came, and the guise in which he went. But she was altogether fearful and amazed that so goodly a knight should wear the semblance of a hawk. When the husband returned to his house—for he was near at hand—his sister told him that of which she was the witness, and of the truth concerning the knight. Right heavy was he and wrathful. Straightway he contrived a cunning gin for the slaying of this bird. He caused four blades of steel to be fashioned, with point and edge sharper than the keenest razor. These he fastened firmly together, and set them securely within that window, by which the tercel would come to his lady. Ah, God, that a knight so fair might not see nor hear of this wrong, and that there should be none to show him of such treason.

On the morrow the husband arose very early, at daybreak, saying that he should hunt within the wood. His sister made the doors fast behind him, and returned to her bed to sleep, because it was yet but dawn. The lady lay awake, considering of the knight whom she loved so loyally. Tenderly she called him to her side. Without any long tarrying the bird came flying at her will. He flew in at the open window, and was entangled amongst the blades of steel. One blade pierced his body so deeply, that the red blood gushed from the wound. When the falcon knew that his hurt was to death, he forced himself to pass the barrier, and coming before his lady fell upon her bed, so that the sheets were dabbled with his blood. The lady looked upon her friend and his wound, and was altogether anguished and distraught.

"Sweet friend," said the knight, "it is for you that my life is lost. Did I not speak truly that if our loves were known, very surely I should be slain?"

On hearing these words the lady's head fell upon the pillow, and for a space she lay as she were dead. The knight cherished her sweetly. He prayed her not to sorrow overmuch, since she should bear a son who would be her exceeding comfort. His name should be called Yonec. He would prove a valiant knight, and would avenge both her and him by slaying their enemy. The knight could stay no longer, for he was bleeding to death from his hurt. In great dolour of mind and body he flew from the chamber. The lady pursued the bird with many shrill cries. In her desire to follow him she sprang forth from the window. Marvellous it was that she was not killed outright, for the window was fully twenty feet from the ground.

When the lady made her perilous leap she was clad only in her shift. Dressed in this fashion she set herself to follow the knight by the drops of blood which dripped from his wound. She went along the road that he had gone before, till she lighted on a little lodge. This lodge had but one door, and it was stained with blood. By the marks on the lintel she knew that Eudemarec had refreshed him in the hut, but she could not tell whether he was yet within. The damsel entered in the lodge, but all was dark, and since she might not find him, she came forth, and pursued her way. She went so far that at the last the lady came to a very fair meadow.

She followed the track of blood across this meadow, till she saw a city near at hand. This fair city was altogether shut in with high walls. There was no house, nor hall, nor tower, but shone bright as silver, so rich were the folk who dwelt therein. Before the town lay a still water. To the right spread a leafy wood, and on the left hand, near by the keep, ran a clear river. By this broad stream the ships drew to their anchorage, for there were above three hundred lying in the haven. The lady entered in the city by the postern gate. The gouts of freshly fallen blood led her through the streets to the castle. None challenged her entrance to the city; none asked of her business in the streets; she passed neither man nor woman upon her way. Spots of red blood lay on the staircase of the palace.

The lady entered and found herself within a low ceiled room, where a knight was sleeping on a pallet. She looked upon his face and passed beyond. She came within a larger room, empty, save for one lonely couch, and for the knight who slept thereon. But when the lady entered in the third chamber she saw a stately bed, that well she knew to be her friend's. This bed was of inwrought gold, and was spread with silken cloths beyond price. The furniture was worth the ransom of a city, and waxen torches in sconces of silver lighted the chamber, burning night and day. Swiftly as the lady had come she knew again her friend, directly she saw him with her eyes. She hastened to the bed, and incontinently swooned for grief. The knight clasped her in his arms, bewailing his wretched lot, but when she came to her mind, he comforted her as sweetly as he might.

"Fair friend, for God's love I pray you get from hence as quickly as you are able. My time will end before the day, and my household, in their wrath, may do you a mischief if you are found in the castle. They are persuaded that by reason of your love I have come to my death. Fair friend, I am right heavy and sorrowful because of you."

The lady made answer,

"Friend, the best thing that can befall me is that we shall die together. How may I return to my husband? If he finds me again he will certainly slay me with the sword."

The knight consoled her as he could. He bestowed a ring upon his friend, teaching her that so long as she wore the gift, her husband would think of none of these things, nor care for her person, nor seek to revenge him for his wrongs. Then he took his sword and rendered it to the lady, conjuring her by their great love, never to give it to the hand of any, till their son should be counted a brave and worthy knight. When that time was come she and her lord would go together with the son to a feast. They would lodge in an Abbey, where should be seen a very fair tomb. There her son must be told of this death; there he must be girt with this sword. In that place shall be rehearsed the tale of his birth, and his father, and all this bitter wrong. And then shall be seen what he will do.

When the knight had shown his friend all that was in his heart, he gave her a bliaut, passing rich, that she might clothe her body, and get her from the palace. She went her way, according to his command, bearing with her the ring, and the sword that was her most precious treasure. She had not gone half a mile beyond the gate of the city when she heard the clash of bells, and the cries of men who lamented the death of their lord. Her grief was such that she fell four separate times upon the road, and four times she came from out her swoon. She bent her steps to the lodge where her friend had refreshed him, and rested for awhile. Passing beyond she came at last to her own land, and returned to her husband's tower. There, for many a day, she dwelt in peace, since—as Eudemarec foretold—her lord gave no thought to her outgoings, nor wished to avenge him, neither spied upon her any more.

In due time the lady was delivered of a son, whom she named Yonec. Very sweetly nurtured was the lad. In all the realm there was not his like for beauty and generosity, nor one more skilled with the spear. When he was of a fitting age the King dubbed him knight. Hearken now, what chanced to them all, that selfsame year.

It was the custom of that country to keep the feast of St. Aaron with great pomp at Caerleon, and many another town besides. The husband rode with his friends to observe the festival, as was his wont. Together with him went his wife and her son, richly apparelled. As the roads were not known of the company, and they feared to lose their way, they took with them a certain youth to lead them in the straight path. The varlet brought them to a town; in all the world was none so fair. Within this city was a mighty Abbey, filled with monks in their holy habit. The varlet craved a lodging for the night, and the pilgrims were welcomed gladly of the monks, who gave them meat and drink near by the Abbot's table. On the morrow, after Mass, they would have gone their way, but the Abbot prayed them to tarry for a little, since he would show them his chapter house and dormitory, and all the offices of the Abbey. As the Abbot had sheltered them so courteously, the husband did according to his wish.

Immediately that the dinner had come to an end, the pilgrims rose from table, and visited the offices of the Abbey. Coming to the chapter house they entered therein, and found a fair tomb, exceeding great, covered with a silken cloth, banded with orfreys of gold. Twenty torches of wax stood around this rich tomb, at the head, the foot, and the sides. The candlesticks were of fine gold, and the censer swung in that chantry was fashioned from an amethyst. When the pilgrims saw the great reverence vouchsafed to this tomb, they inquired of the guardians as to whom it should belong, and of the lord who lay therein. The monks commenced to weep, and told with tears, that in that place was laid the body of the best, the bravest, and the fairest knight who ever was, or ever should be born. "In his life he was King of this realm, and never was there so worshipful a lord. He was slain at Caerwent for the love of a lady of those parts. Since then the country is without a King. Many a day have we waited for the son of these luckless lovers to come to our land, even as our lord commanded us to do."

When the lady heard these words she cried to her son with a loud voice before them all.

"Fair son," said she, "you have heard why God has brought us to this place. It is your father who lies dead within this tomb. Foully was he slain by this ancient Judas at your side."

With these words she plucked out the sword, and tendered him the glaive that she had guarded for so long a season. As swiftly as she might she told the tale of how Eudemarec came to have speech with his friend in the guise of a hawk; how the bird was betrayed to his death by the jealousy of her lord; and of Yonec the falcon's son. At the end she fell senseless across the tomb, neither did she speak any further word until the soul had gone from her body. When the son saw that his mother lay dead upon her lover's grave, he raised his father's sword and smote the head of that ancient traitor from his shoulders. In that hour he avenged his father's death, and with the same blow gave quittance for the wrongs of his mother. As soon as these tidings were published abroad, the folk of that city came together, and setting the body of that fair lady within a coffin, sealed it fast, and with due rite and worship placed it beside the body of her friend. May God grant them pardon and peace. As to Yonec, their son, the people acclaimed him for their lord, as he departed from the church.

Those who knew the truth of this piteous adventure, after many days shaped it to a Lay, that all men might learn the plaint and the dolour that these two friends suffered by reason of their love.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sweet Secret - Feysand Month

@unofficialfeysandmonth2022 - Day 28 - Classics

Based on Marie de France's 12th-century Breton Lai, Lanval

Summary: Feyre and Rhys make a bargain. One pledges love and provision, the other love and secrecy. But what happens when the demands of a human court threaten their promises? Is love enough? What does one owe to another after a promise is broken?

Read here on AO3! Enjoy a short, short snippet below:

So this was love. Interesting.

It was more piteous than she had imagined, Feyre reflected, taking in the scene before her. And significantly more human.

Some Notes:

Between the end of the semester and my holiday plans, I hadn’t expected to write anything for Feysand month, but then my mom got sick and our holiday plans got postponed, so here we are! The fic is a WIP; my outline for it quickly ballooned beyond what I could achieve in time to post for day 28, but I’m hoping to finish it soon. The story is based on Marie de France’s lai Lanval, with a fae!Feyre and human!Rhys. I had originally intended the fic to stay pretty close to the narrative of the poem and be 90% Rhys' POV, but then writing Feyre was a delight that will probably pull the story in a slightly different direction, so...we'll see what happens.

Many thanks to @perhapsajacket for beta reading at the last minute and encouraging my desire to write weird fae women.

Title from Alfred David's translation of the text, line 145.

#feysand#feysand month#feysandmonth2022#feysand fic#fae!Feyre#human!rhys#feysand smut#lanval#marie de france

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animalec Fest

September 23: Lost

@animalecfest

This chapter is the first of a three-part series covering the prompts Lost, Sacrifice and Mating. These chapters were inspired by the twelfth-century Breton poem "Bisclavaret" by Marie de France, also known as "the Lay of The Were-Wolf". You can read a translation of the original story here:

🐺⚔️👑🐺⚔️👑🐺⚔️👑🐺⚔️👑🐺⚔️👑🐺⚔️👑

It was a clear, crisp autumn morning on the day that Magnus rode out from his castle, the air cool on his face. Avorig, the land of his kingdom, was beautiful to him at any time, but particularly so at this time of year, with the leaves just turning golden on the trees and the first hint of winter cold in the air. He drew rein as he came to the top of a hill and smiled as he saw his destination spread before him. Tan Koad Castle, one of the ancestral seats of the Avorig barons, and home to one of Magnus’s very favourite people.

He rode down the valley slopes to the castle, his horse’s hooves clattering on the cobblestone as he rode through the gates. There was already someone waiting for him in the castle courtyard, and Magnus smiled softly as he recognised the tall figure.

Alec came up to him, holding the horse’s reins so Magnus could dismount. “Welcome, my lord. We didn’t expect you for another hour at least.”

“I have a fast horse.” Magnus said. “And I brought no entourage, as you can see.” He waved his hand towards the empty gate of the castle.

A slight frown touched Alec’s face. “My lord, you shouldn’t be travelling alone.”

“I’m not alone now, am I?” Magnus murmured. “I’m with you.” He let his hand brush Alec’s arm lightly, and the knight looked away quickly, signalling for a stablehand to take Magnus’s horse.

As Alec opened the door of the castle, Magnus put his head on one side, considering him. Alexander Lightwood, baron of the Tan Koad region since his father had died five years before. One of Magnus’s most loyal knights, who had guarded this harsh border country so well that Magnus had never heard a single complaint from any of Alec’s people. A man who seemed to have everything, at least on the surface.

And yet, he had secrets. There was something Alec was hiding, something Magnus couldn’t guess at. There was the way Alec looked at Magnus, of course. He’d known that for years, had spent many sleepless nights lying awake consumed by the thought of Alec’s eyes, his lips, his hands. He’d seen Alec’s blushes, his gazes that lingered on Magnus a second too long before pulling away. All this Magnus knew.

But there was something else as well, an even larger secret Alec was hiding. Magnus sensed it instinctively. He didn’t know what it was, but he had never pushed Alec to reveal all the sides of himself that he kept hidden.

“I would like to ride with you, Alexander, once my horse is rested.” Magnus said. “Somewhere private, where we can discuss affairs. Of the barony, that is.”

Alec stiffened slightly, his back straightening. “Of course. Affairs of the barony.” There was the faintest flush in his cheeks, which Magnus ignored. “If you’ll give me a minute to change into my riding clothes?”

May I watch? Magnus wanted to say, but stopped himself just in time. He merely nodded, and Alec backed away, then turned quickly and headed up one of the winding stone staircases into the tower.

Magnus gave a little sigh and sat down on one of the plush couches that stood in the entrance room. A moment later, there was a noise of footsteps behind him and he turned to see Alec’s sister, Lady Isabelle and someone else that Magnus was very fond of.

“My lord.” Isabelle said, raising her eyebrows. She didn’t seem at all surprised to find the king waiting in her castle. She dropped a perfunctory curtsey— Isabelle had never shown much respect for royalty, which Magnus secretly admired her for— and sat down opposite him, smoothing out the skirt of her red velvet gown.

“It’s a pleasure to have you, as always.” She raised her eyebrows knowingly at him. “I do hope my brother isn’t boring you too much.”

Magnus leaned back, smiling at her. “Not to worry, my lady. I’ve never found Alexander boring.”

Isabelle smiled in return. She stood and crossed over to the far wall, where there were a number of wine kegs stacked up for the winter. She poured them both a drink and returned to the couches, handing Magnus one of the goblets. He took an appreciative sip of the wine, feeling the warmth spread through his chest and looked back at Isabelle. She was resting her chin on her hand, gazing at him thoughtfully.

“You should visit more often, my lord.” she said, although Magnus already visited Tan Koad more frequently than any of the kingdom’s other baronies. “It breaks the monotony. And Alec’s always so happy to see you.”

“Really?” Magnus said, with exaggerated surprise. “I had the impression that Alexander couldn’t wait for me to leave.”

Isabelle laughed, then became more serious. “Really, Magnus. It’s good for him, getting to see you. It’s just about the one happiness he ever gets.”

Magnus opened his mouth to say something else, but at that moment Alec came into the entrance hall, dressed in his riding gear. His eyes swept over Magnus and Isabelle. Magnus wondered if he’d heard anything of their conversation. He didn’t think so, but he couldn’t be sure.

“Alas, my lady, I must take your leave.” Magnus said, with a dramatic bow. Isabelle smiled and swept past him with a wink. “Have fun, my lord.”

The forest was golden and red, leaves clustering around them like a bright tapestry, shot through with dark tree trunks. Magnus rode close to Alec, their knees nearly touching on the narrow forest trail. Alec was telling Magnus everything that had happened since his last visit— a couple of border raids, a storm that destroyed three fields— but Magnus wasn’t really listening. He was distracted by the low soothing hum of Alec’s voice, how the moisture-laden air made the hair at the back of his neck curl damply. He kept thinking about what Isabelle had said

Alec seemed to realise he wasn’t listening and tailed off mid-sentence. “Is everything alright, your majesty?”

“How’s your wife?” Magnus asked abruptly.

Alec flinched, very slightly. “She’s fine.”

“It must be hard for her,” Magnus said conversationally, “when meeting with the king takes up so much of her husband’s time.”

He didn’t know why he goaded Alec like this, except maybe he preferred seeing Alec angry rather than miserable. If he was angry at Magnus, at least Magnus knew he felt something towards him, rather than just apathy.

Alec’s hands tightened briefly on the reins, but his face remained blank. “Lydia and I both know our duty to the kingdom. If the king needs to speak to me, I am there.”

Ah, yes. Baroness Lydia Lightwood, formerly Branwell. For a long time, Magnus had wanted to hate her, but found that he couldn’t. She was gracious, clever and politically capable, and it wasn’t her fault she happened to be married to the man Magnus adored. For years he’d watched them dance around each other, caught in the awkwardness of a political marriage that they were desperately trying to make work, despite being completely unsuited as a couple.

He remembered their wedding, not long before Alec’s parents died. Magnus himself, as the King, had been the one to perform the ceremony. He hadn’t known Alec well at the time, and had wondered why the young man looked so pale and agitated at the altar. Then, as he had got to know Alec better, and seen the way his eyes lingered on Magnus, he’d begun to suspect why. But by then it had been too late to do anything about it.

Magnus wondered, sometimes, if he’d been cursed at birth, doomed to live a life of luxury as the King, with everything he could want except the one person he wanted more than anything.

“I recently increased the garrison patrols on the kingdom’s borders.” Alec was saying, and Magnus realised he’d been letting his mind wander.

“Is that right?” he replied. “How far are we from the border now?”

“About an hour’s ride.” Alec said. He seemed more relaxed now that the conversation had shifted back to matters of military strategy.

“So we’re unlikely to see anyone where we are now.” Magnus said. “After all, this is a very remote part of the kingdom, isn’t it? How far away is the nearest settlement from here?”

“At least a mile.” Alec replied. He was staring pointedly at the path in front of them, not meeting Magnus’s eyes.

“So we’re completely alone.” Magnus said. He nudged his horse a fraction closer, so his knee just brushed Alec’s. Alec stiffened very slightly but kept his eyes straight ahead. “If you say so, my lord.” he replied noncommittally.

Magnus waited, hoping, but there was no other response from Alec. Disappointed, he allowed his shoulders to slump slightly.

“Is there anything else you wished to discuss, my lord?” Alec asked.

Magnus stared out at the expanse of the forest, full of whispering leaves and softly moving shadows. “Do you love me, Alexander?”

He thought he heard a sound like a pained gasp, like Alec had been struck, but when Magnus swung back to look at him he was perfectly composed, except for the faintest flush along his cheekbones. “Of course I love you.” Alec said evenly. “You are my king. I swore an oath to serve you and protect you, and lay down my life for you if necessary. I love you as all your knights love you, no less and— and no more.” He swallowed thickly, his eyes still fixed on the trees around them.

“Is that true, my Alexander?” Magnus asked, his voice low and seeking.

Alec’s eyes darted to him for just a fraction of a second, the blush in his cheeks deepening. Then his gaze dropped and he seemed to withdraw in on himself like a crab drawing into its shell. “Yes, my lord.” he said, in a very tight, controlled voice.

Magnus looked away. For a long time, there was silence, broken only by the soft thudding of their horses’ hooves and the jangling of the bits. There was a deep ache in Magnus’s chest, like the pain of a wound, or the pain of something missing from him.

“Is there anything else, my lord?” Alec asked finally.

Magnus’s voice was heavy as he replied. “No, Alexander.” He turned his horse back towards the castle and Alec followed him a second later. They rode the rest of the way in silence, Magnus staring fixedly at the woods around them, but never at Alec’s face. The ache in his chest grew worse with every beat of his heart, weighing on him like a stone.

Back at the castle, Alec swung down from his horse, but Magnus stayed in the saddle. Alec looked up at him in surprise. “Your majesty, aren’t you— aren’t you going to stay longer?”

“No.” Magnus said quietly, staring out at the forest. “No, I don’t have anything more to discuss with you at present. I’ll be back before too long, Alexander. Look after my people for me.”

Alec exhaled raggedly. “My lord—”

“I would much prefer,” Magnus said softly, “if you just called me Magnus.”

Alec’s eyes darted around, the colour coming back into his cheeks. “No.” he said thickly. “No, you’re the king. That wouldn’t be— right.”

Magnus looked down at him. “Why are you trying to tell me what’s right, Alexander?” he asked gently.

Alec’s flush deepened and his eyes dropped. His mouth opened, then closed again abruptly.

“Look after yourself, Alec.” Magnus murmured. He wheeled his horse around, galloping away from the castle. He didn’t look back at Alec, standing alone under the dark battlements.

Later, he would wish he had.

_______________________________________________

It was more than two weeks before Magnus got another chance to ride to Tan Koad and see Alec. This time, as he rode into the courtyard, he could see instantly that something was wrong. There was none of the cheerful busyness that was usually found in a castle. Guards and servants were hurrying around in every direction, talking together in little huddles or doing their usual tasks with an air of barely controlled panic. The whole scene was one of fearful agitation. Such was the chaos that it was nearly a full minute before anyone noticed that the King was in their midst.

Isabelle came hurrying out of the central tower and ran to Magnus. There was none of the casual, cheerful attitude she’d had the last time Magnus was here. She looked like she was fighting back tears.

“What is it?” Magnus asked in alarm, though a suspicion was already creeping at the back of his mind.

“It’s Alec.” Isabelle whispered. She gulped back tears, wiping her face hurriedly. “He’s vanished, Magnus. Last night, when everyone was asleep. We can’t find him anywhere. He’s gone.”

#malec#magnus bane#alec lightwood#tsc#shadowhunters#cassandra clare#the shadowhunter chronicles#animalec fest 2023#isabelle lightwood vibes#lydia branwell#don't worry guys malec is endgame#i had so much fun researching medieval courtly traditions for this fic#and setting it in medieval brittany was so interesting#trying to work in little details of language and culture#malec fanfic#bisclavret#marie de france

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

New episode! The other part of that one from last week we had to cut in half.

-----

It's the final part of Yonec, and in this episode, we explore how to adapt the Fairy Ring of General Inconspicuousness into your game, and how meta you can get with your meta-textuality. Join us and turn your next D&D game into an extra-planar fairy adventure!

Join our discord community!

Check out our Tumblr for even more!

Support us on patreon!

Check out our merch!

The Beastiary Challenge! (<-- Don't miss it!)

Socials: Tumblr Website Twitter Instagram Facebook

Citations & References:

The Lais of Marie de France

Celtic Origins of Lais of Yonec

The Anonymous Fairy-Knight Lais

#medieval#medieval literature#ttrpg#marie de france#yonec#d&d#dnd#dungeons and dragons#podcast#maniculum

5 notes

·

View notes