#Egyptian priests

Text

Simple facts about Ancient Egypt (2)

Last time, we talked about generalities - history, geography, pharaohs, government... Today, let’s look at some of the main social classes and jobs in Ancient Egypt!

As I said before - warning, these are oversimplified and general facts for a short and easy introduction and comprehension to Ancient Egypt. These are not in-depths studies or analysis, and I might have gotten things wrong, so beware!

SCRIBES

# Scribes, from the Latin “scribere” (to write) were public writers: they were tasked with redacting administrative documents, with the job of accountants of the State, but they were also tasked with writing things such as letters, poems or fictional tales. The job of a scribe went from father to son, and every future scribe had to undergo a very strict and difficult apprenticeship. To be a scribe was a very envied position, for it was a privilege given only to boys – and to the wealthiest of boys! The material of the scribe was quite simple, all contained in a wooden case: there was just a reed pen, and two blocks of ink, one red and one black – to write, the scribe plunged the tip of his reed pen into water, and then rubbed it against either the black or red ink-block.

# Because ink was we know it today didn’t exist back then in Egypt – their “ink” was actually blocks of compact powder. Black ink was created with soot or crushed coal, whereas red ink was created with ochre. Similarly, the Ancient Egyptians did not write on paper but on papyrus – a type of material that shared its name with the type of Nile-reed it was created from. (Fun fact, the name “paper” does come from “papyrus”). Creating papyrus was done by cutting and peeling the papyrus-reed into thin slices, that were then gorged with water, placed in crosses layered on top of each other, and then brutally hit with a hammer until it became one uniformed page (the sap of the reed and the water fused together to form a sort of “glue” holding the stripes together). Finally, the page was thinned down, and smoothed with wooden items.

# Papyrus was however very costly. So, to not lose all of one’s money, Ancient Egyptians wrote for every day needs on pottery fragments or wooden planks covered in plaster. Pupils in schools for example wrote on broken pieces of bowls or vases. The papyrus, so precious, was kept exclusively for law texts and religious texts. To create 5 scrolls of papyrus, of roughly 10 meters each, a man had to work for a whole year!

# Most scribes worked for the government: one of their job was to do note down the state and quantity of the harvests each year before calculating the taxes based on the amount of harvest. They were also the accountants of the state, as well as the ones charged with writing down the laws and the orders of ministers. Other scribes rather worked for temples, where they engraved magical incantations on amulets ; and a third group acted as clerks in tribunals.

# Learning to become a scribe might look easy, since what you need to do was just copy texts all day long… But in truth it was a very hard thing! Our alphabet only has two dozen letters or so – the Egyptian scribes had to learn thousands of different signs to write down the texts, and they had to learn how to write them on every material possible. If you wanted to be a scribe, you had to go a “scribe school” – pupils usually went there are the age of ten, and left at fifteen. After these five years of studies, the scribes had to undergo an internship of five years in either the administration, in a temple or with a notary. After this internship, would-be-scribes had a final exam – and it was only then they could become certified and testified scribes, at twenty years old. Scribe school was notably a very harsh and unpleasant place – a common saying among scribe teachers was “Students have ears in the back, and these ears only listen when you hit them”. Yes, corporal punishment was a standard method of teaching in these schools – if students didn’t pay attention, spoke with each other instead of copying their texts, or wrote a hieroglyph wrong, they were immediately beaten up with a stick. In fact, to prevent the students of scribe schools from leaving unsupervised, the teachers attached to their ankles wooden blocks! Yes, just like the cartoon prisoner with the iron ball around their ankle!

# All scientists were scribes, but not all scribes were scientists (or scholars). You see, to become a scientist or a scholar you had to learn how to write and read – and to do that, you needed to become a scribe. But many scribes stopped there and did not pursue their studies further – only some decided to take on a specific field of expertise (medicine, architecture, astronomy) and thus became more than just “regular” scribes.

# Scribes wrote their text in a very specific way. They sat cross-legged on the ground, placed the papyrus they wrote on their loincloth – that was pushed by their knee very strongly on each side, so it would be a flat surface to write onto. Scribes also wrote with their pen standing up, very still – so that they wouldn’t do any stain or mess up a line, because their ink took a very long time to dry.

# Scribes were the object of admiration, but also jealousy, from the everyday ordinary Egyptian man, because scribes were very well paid AND were exempt of taxes. Plus, their work was a non-manual one, unlike the other Egyptian men who were peasants or craftsmen. This was notably why in Egyptian art scribes are always depicted with a potbelly or fat rolls – thanks to their wealth and effortless job that demanded them to sit around all day, they were the only inhabitants of Ancient Egypt who could easily become fat. In return, the scribes themselves were very proud of their position and status – and this often made them quite arrogant, according to the ancient texts. One of the favorite entertainments of the scribes was to mock other jobs or workforces of Egypt by telling funny stories or jokes about them.

PRIESTS

# Do not get things wrong: in Egyptian religion, only the pharaoh can act as an intermediary between the gods and men – he is the true voice and right hand of the gods. But then, you’ll ask, why are there priests? Well it is simply because the pharaoh is one human man, and cannot be everywhere in the country – so the pharaoh delegates his powers to the priests, who act in his name. This is something important to remember: Ancient Egypt was a form of theocracy, and the priests did not get their power from the gods but from the pharaoh. Though the priests’ role WAS to serve the gods. Ancient Egyptians and Ancient Egyptian gods had a deal worked out: the priests would tend to their need, and take care of them, through various festive celebrations and everyday rituals, and in exchanged from being tended to, the gods ensured the protection and wellness of the city/region/country they were worshiped in. As easy as that. But this explains why for example priests were not depicted on murals or paintings of temples: priests were not perceived as worthy of being depicted alongside the gods, because in the Egyptian mindset, priests are just servants – or rather some sort of religious bureaucrats. Only the pharaoh, the one and true emissary of the god, and himself equal to the gods, could be painted on the walls of temples.

# The role of priests, just like the one of scribe, usually was passed from father to son. Usually priests began their apprenticeship as children, studying at the school and at the library of the temple alongside scribes. Given being a priest was a very prestigious function (again, quite like scribes), some people rather could buy a priest job with a heavy sum of money, or it could be given by the pharaoh himself as a reward, to those that served him well and faithfully.

# In every great temple and religious center of Egypt there was, at the top of the priestly hierarchy, a great priest, or “first prophet”, named directly and personally by the pharaoh. This great priest held authority over all of the other priests, and also played a political role in the city he was in charge of. Below him came the “divine fathers”, important priests that took care of the rituals and walked in front of their god’s statue during processions. Finally, at the bottom of the hierarchy, there were the “purified ones”, whose job was to carry the god’s statue during procession, to clean up the temple every day, and to do all the chores. Speaking of cleanliness, being pure was a very big deal for Ancient Egyptian priests – they usually took four baths a day in the lake’s temple, or rather two baths during the day and two baths during the night. It was a way for them to stay “pure”.

# Priests had a LOT of work and so, to be able to rest and not die of exhaustion, there were “teams” of priests formed in temples. Each team was to work in the temple during one month while the other went to live into town, and after one month a new team went in. In smallest temple there were only two teams, each doing half of the year, but in the biggest temple, there could be up to four priest teams. And since the priests were to live in the town quite regularly, and couldn’t possibly live alone (for Egyptians a man couldn’t just live all on his own, it was not a good or healthy lifestyle), the priests were allowed and even encouraged to marry, so that when leaving the temple they could have a wife and children to return to – children that in turn would become priests once their father grew too old.

PEASANTS

# Peasants formed the bulk of the Egyptian population, and they were a key part in the wealth of the nation: without them and their constant toil, Egypt couldn’t have existed. But despite their immense utility, priests were very poor and not respected, forming the lower rank of the social hierarchy. Most of them acted like serfs, in service of great landowners, temples, or the ministers of the pharaoh. The comparison to serfs is quite relevant as, just like serfs, Egyptian peasants did not own their lands, and they could be sold just alongside the land they were dependent.

# The fields of the peasants were actually really small, roughly the size of a vegetable garden today. They were delimited by big and heavy rocks – every year, bureaucrats of the realm checked after each flood is these rocks hadn’t been move. The peasants also had to swear an oath to never move secretly the stones to augment their field – if they were caught doing that and lying about it, they had their two ears cut off!

# Scribes went three times a year into every peasant’s home. A first time to measure their field, a second time once the cereals ha d grown – to evaluate the harvest and calculate future taxes based on this hypothetical harvest – and a third time during the harvesting, to collect the taxes. Of course, on this third visit, scribes were escorted by armed soldiers. If a peasant refused to pay the taxes, he was beaten up, and/or his house and tools were taken away from him – sometimes he was even thrown into prison. According to some tales, the most extreme cases of punishment had peasants that did not pay their taxes being beaten up, tied with a rope, and thrown at the bottom of a well in front of his wife and children – who in turn were imprisoned in his place! Better pay the taxes the, you say? Well, the problem was that the taxes were calculated during January, two to three months before the actual harvest. If any sort of disaster happened, and they lost their harvest, they still had to pay the taxes as if they had a full harvest…

# No need to tell you that the peasants’ worst enemy (outside of the locust) was the hippopotamus! Hippopotami were considered a true disaster, since in a single night, a hungry hippo could eat up to sixty kilos of plants (132 pounds). If a small group of hippos came by a field in the night, in the morning nothing was left… So peasants hunted and killed hippos without pity or mercy.

CRAFTSMEN

# Craftsmen were the middle-class of Egypt, coming below the scribes and bureaucrats, but above peasants. Craftsmen worked numerous types of material: stone, wood, iron, precious metals (such as gold), leather, textiles and glass. Craftsmen never worked alone – they were always forming groups and teams, part of workshops financed by the government, or by a temple, or by a rich family. Each workshop gathered various specialists – a carpenter, a painter, a smith, a jeweler, a stone-sculptor…

# The quality of a furniture could be identified by the type of wood used: good quality furniture was done by sculpting cedar, a tree that was important from the Lebanon. High quality furniture was also often decorated with ivory or ebony. Lower quality furniture however, was usually sculpted in sycamore trees or palm trees – a wood so friable they were often covered in plaster to just be able to stand up and hold any kind of weight!

# The Egyptians discovered how to make class towards 1500 BCE. They created it with sand, salt, and they always colored their glass with metallic pigments – an Egyptian would have never created a transparent piece of glass. Egyptians loved colors, and so their glass work was always red, blue or yellow.

# Potters were considered to be “different” from other craftsmen. More specifically they were thought to practice a very “common” craft. Scribes liked to mock them by describing them as dirty, and always covered in mud. Potters did not work in the royally-sponsored workshops I described above – they rather worked all alone, for their own. They built most of everyday objects: vases, plates, cups, jars… Potters usually worked with the clay of the Nile, sculpted by hand (at first, then the potter’s wheel was invented), and then left to dry up in the sun before being “cooked” in an oven. Their other technique was to create a material by mixing sand with water, salt, ashes and lime – this substance was then placed inside molds, and placed in an ove.

# Pearls in Ancient Egypt are a fascinating thing, because Egyptians did not know about the existence of oysters – or if they did, they couldn’t access any of them. So, Egyptians created their own pearls, by polishing stones so much they were reduced to very small spheres, that were then pierced to be placed onto necklaces.

# All the gems and precious stones used by Egyptians (the red carnelian, the purple amethyst, the turquoise and the blue agate – plus gold of course) were extracted from mines located in the desert, and in which criminals and law-breakers were sent to work (because working in these mines often killed the miners). The favorite gem of the Egyptians, the lapis-lazuli, was rather important from where today’s Afghanistan is located. However, faience/earthenware was very common among Egyptians precisely because with its blue-green color it could look like emeralds or turquoises, while being much MUCH less costly. This is why there were a lot of faience jewels in Ancient Egypt – they were basically for those who wanted to look good without having the means to.

#ancient egypt#scribes#peasants#egyptian religion#egyptian priests#ancient egyptian crafts#craftsmen#ancient egyptian society

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

ancient vegetarianism of Egypt - the only evidence of vegetarianism before ~700 BCE

The tomb inscriptions and other sources that mention vegetarianism among Egyptians date from various periods throughout ancient Egyptian history. Old Kingdom’s (c. 2686-2181 BCE) King Weneg venerated Goddess Ma’at and both are associated with vegetarianism.

One example is the tomb of Hesi, a high-ranking official from the 3rd Dynasty (around 2686-2613 BCE). The inscriptions in his tomb mention that he abstained from meat, stating that he "never ate meat or fish in his life" and that he "did not cause suffering to animals."

Another example is the tomb of Kaaper, a priest from the 5th Dynasty (around 2494-2345 BCE). In his tomb, there is an inscription that says, "I was a vegetarian who did not eat the flesh of animals or birds," suggesting that he abstained from meat.

There are inscriptions and paintings from tombs and temples during Fifth and Sixth Dynasties (c. 2494–2181 BCE) that depict individuals engaging in vegetarianism or avoiding certain types of meat. The Old Kingdom tomb depicts Ti at Saqqara and his family enjoying a vegetarian meal of lotus flowers, which suggests that they may have abstained from meat. Other examples include tomb inscriptions from the Middle Kingdom (circa 2055-1650 BCE), such as the tomb of Ameny at Beni Hasan, which features scenes of vegetarian meals and animal husbandry but no scenes of animal sacrifice.

In the Coffin Texts, which date back to the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE), there are references to a mythical island called "The Field of Offerings," where there is no need for animal sacrifice because the inhabitants subsist on bread, beer, and vegetables.

Another example comes from the "Satire of the Trades," a text from the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE) that describes various professions and their shortcomings. In this text, the priests are described as being lazy and gluttonous, but also as avoiding the consumption of certain types of meat, such as pig and fish.

In the Papyrus Insinger, a text from the 18th dynasty (1550-1295 BCE), there is a story about a group of priests who refuse to eat fish because it was considered to be a sacred animal.

"Let your Ka (life force) be content with bread, and your heart with beer. Do not eat fish in it (the temple), for it is a sacred animal." - Papyrus Insigner 22.6-7

One of the most famous examples of vegetarianism among Egyptian priests comes from the New Kingdom period (c. 1550-1070 BCE), during which the cult of Ptah became particularly prominent. Several tombs from this period contain inscriptions that suggest that priests of Ptah were required to abstain from certain kinds of meat, such as beef and pork. Some of these inscriptions also suggest that the priests may have been required to fast from meat for extended periods of time.

Some scholars have suggested that certain religious and cultural practices from ancient Egypt may have had vegetarian or semi-vegetarian components, even if they were not explicitly described as such. One example of this is the role of the goddess Isis in Egyptian mythology. According to some ancient texts, Isis was sometimes referred to as a "vegetarian goddess," and her followers were encouraged to abstain from certain kinds of meat, such as beef and pork. Some scholars have suggested that this practice may have been linked to the belief that consuming certain animals was seen as impure or ritually polluting.

^ did not verify actual references for all this though! #chatgpt

#chatgpt#eygpt#priests#egyptian#Egyptian priests#old kingdom#vegetarianism#veganism#veg#vegan#religion#spirituality#ptah#animal rights#purity#history#ancient history#ancient civilization#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#meluhha#melakam#mesopotamia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Block Statue of a Prophet of Montu and Scribe Djedkhonsuefankh, son of Khonsumes and Taat

Late Period, Kushite–Saite

690–610 B.C.

On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 125

In the late 25th dynasty and early 26th Dynasty the austere beauty of the block statue form, here particularly enhanced by the hard gleam of dark surfaces, was greatly appreciated. The form puts a strong emphasis on the face and complements the often stern countenances favored at the time.

The front of the statue gives the names, titles and parentage of Djedkhonsuiuefankh, son of Khonsumes and Taat. Djedkhonsuiuefankh can be linked to a multigeneration illustrious family of priests at Thebes. On the top of the base is an appeal to the living, a request for offerings to those who would pass the statue where it was placed in Luxor Temple. On the back pillar is an inscribed formula known as the Saite formula.

Artwork Details

Title: Block Statue of a Prophet of Montu and Scribe Djedkhonsuefankh, son of Khonsumes and Taat

Period: Late Period, Kushite–Saite

Dynasty: Dynasty 25–26

Date: 690–610 B.C.

Geography: From Egypt; Made for Upper Egypt, Thebes, Luxor

Medium: Gabbro

Dimensions: h. 30.7 cm (12 1/16 in)

Credit Line: Rogers Fund, 1907

Accession Number: 07.228.27

Provenance: Purchased from M. Casira, Egypt, 1907.

Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547694

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptian calendar arises at the beginning of 3rd Millennium BC and is the first known solar calendar in history.

It was in full use at the time of Shepseskaf, the pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty.

In Pyramid Texts, the 365 days of the Egyptian civil year are mentioned. It was divided into 12 months of 30 days each, organized into three groups of ten.

At the end of the last month of each year, the five days (epagomena) that were left to complete the solar year were added — dedicated to various Egyptian gods.

“The Egyptians were the first of all men who discovered the year, and they said that they found this from the stars.” (Herodotus Histories II-4)

As Egyptian civil calendar did not have the fourth day that the astronomical solar year has in excess, every four years, it lost a day, so it became a “wandering calendar,” where “astronomically fixed periodic” events roamed through the months of calendar.

Since the dawn of the Empire, Egyptian priests carefully recorded the level of the waters, which they measured with nilometers.

Timing of sowing or harvesting depended on it, and after years of observations, they discovered that the cycle repeated every 365 days.

In Herodotus’s words: Egypt was a gift from the Nile.

This comment is not a literary image but a reality.

Annual river floods caused by the monsoon flooded the fields, covering the desert sands with fertile silt.

In Egypt, various calendars – Lunar, Solar (civil), and possibly a third secondary lunar calendar – were used to accurately calculate ephemeris.

Egyptian astronomical priests discovered that lunar calendars were not practical to predict the beginning of Nile floods, calculate the seasons, or count long periods, then comparing them with a measurement referring to the apparent movement of the Sun and the stars, they preferred to use the solar calendar for civil uses for the first time in history.

Egyptians may have used a lunar calendar before, but when they discovered the discrepancy between the lunar calendar and the regular passage of the seasons, they probably switched to a seasonal calendar, basing their regular onset on each annual Nile flood.

First flood according to The Calendar was observed in the first capital of Egypt, Memphis, at the same time as the heliacal rising of the star Sopdet (Sirius).

Egyptian year was divided into the three seasons of an agricultural nature:

• Flood (late summer and fall)

• Sowing (winter and early spring)

• Harvesting (late spring and early summer)

Astronomers in Middle Ages used Egyptian calendar because of its mathematical regularity.

Nicolaus Copernicus, for example, built his tables for the movement of planets based on measurement of time with Egyptian year.

Egyptian civil calendar had three seasons of four months of thirty days, plus five epagomenal days.

Only after the New Kingdom will the months of the civil calendar have their own names.

Name of months underwent variations over time, as well as the exact date of the beginning of the year.

The name given to each of the twelve months corresponds to the time of the New Kingdom.

Plus, five Heru-Renpet days (“those that are above the year” or epagomenal days), from August 24 to 28.

They were also known as (“of the birth of the gods”), since the birth of five Egyptian deities was celebrated in them: Osiris, Horus, Seth, Isis, and Nephthys.

Later, in the Coptic language , they were called Piabot Nkoyxi (“the little month”).

© Historical Eve

#Egyptian calendar#solar calendar#Shepseskaf#Ancient Egypt#ancient civilizations#Herodotus Histories#Nicolaus Copernicus#Piabot Nkoyxi#Egyptian deities#Egyptian priests

1 note

·

View note

Text

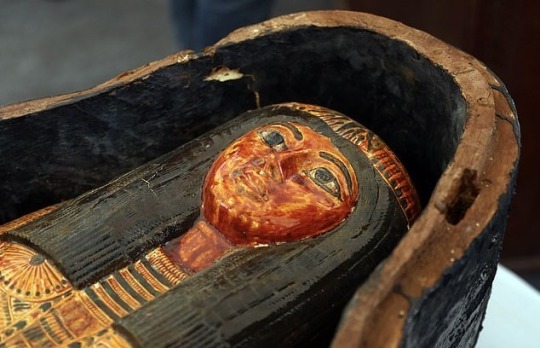

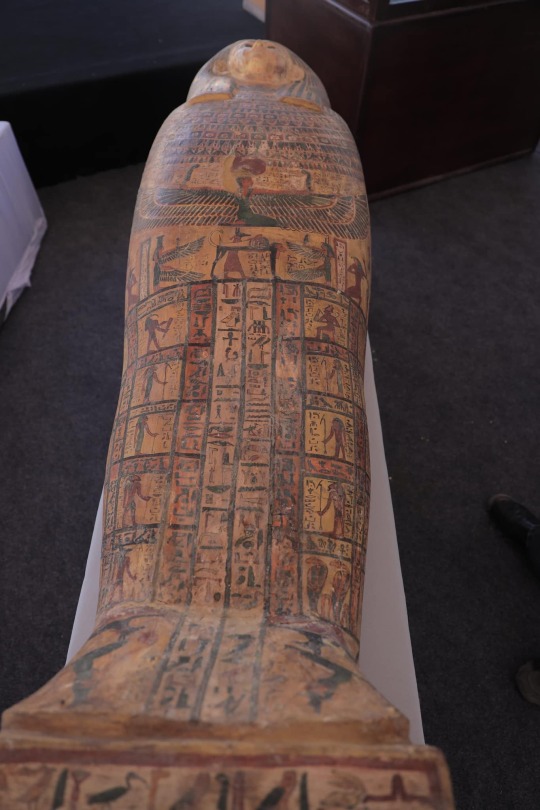

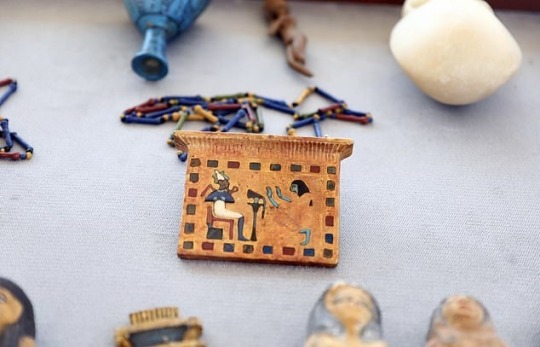

3,400-Year-Old Ancient Egyptian Cemetery Found With Colorful Coffins

Archaeologists have uncovered an Ancient Egyptian cemetery dated to more than 3,000 years ago containing the colorful coffin of a high priest's daughter and preserved mummies, among hundreds of other finds.

Researchers unearthed the cemetery at the Tuna el-Gebel necropolis, located almost 170 miles south of Cairo in Minya Governate, Egypt's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced in a statement on Sunday.

The cemetery, which dates back to the New Kingdom (16th-11th centuries B.C.) of ancient Egypt, was used as a burial ground for senior officials and priests during the period, according to archaeologists.

The cemetery was uncovered during excavations that began last August in the Al-Ghuraifa area of Tuna El-Gebel and features "many tombs" that have been carved into rock.

Researchers have also made hundreds of archaeological finds at the site, including stone and wooden coffins—some of which contained mummies—amulets, ornaments and funerary figurines.

One of the most notable finds at the cemetery is a colorful, engraved coffin belonging to the daughter of a high priest of the ancient Egyptian god Djehuti, often referred to as Thoth.

This deity, commonly depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or baboon, was a key figure in ancient Egyptian mythology and played several prominent roles. For example, Thoth was credited with the invention of writing and is also believed to have served as a representative of the sun god Ra.

Next to the coffin of the high priest's daughter, archaeologists found two wooden boxes containing her canopic jars, as well as a complete set of "ushabti" statues.

Canopic jars were vessels used by the ancient Egyptians to store the organs removed from the body in the process of mummification—the lungs, liver, intestines and stomach—in order to preserve them for the afterlife.

Ushabti statues, meanwhile, were figurines used in ancient Egyptian funerary practices that were placed in tombs in the belief that they would act as servants for the deceased in the afterlife.

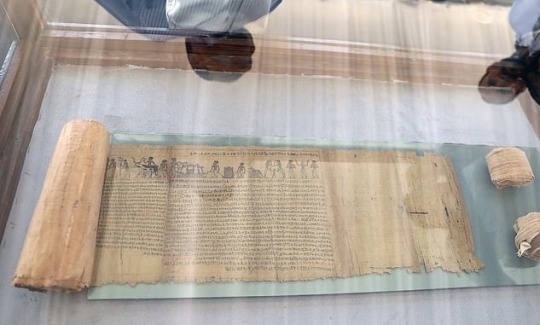

Archaeologists also made another particularly fascinating find at the New Kingdom cemetery: a complete and well-preserved papyrus scroll measuring approximately 42-49 feet in length that features information related to the Book of the Dead.

The Book of the Dead is a collection of ancient Egyptian funerary texts consisting of spells or magic formulas that were placed in tombs. These texts were thought to protect and aid the deceased in the afterlife. They were generally written on papyrus, a material similar to thick paper that was used as a writing surface in ancient times.

Mostafa Waziri, secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, said in the statement that the discovery of the cemetery is an "important" find.

By Aristos Georgiou.

#3400-Year-Old Ancient Egyptian Cemetery Found With Colorful Coffins#Tuna el-Gebel necropolis#Minya Governate#ancient grave#ancient tomb#ancient cemetery#ancient necropolis#book of the dead#canopic jars#Egyptian god Djehuti#high priest#high priestess#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian gods#egyptian mythology#egyptian art

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ "Leopard-skin” robe of the priest, Harnedjitef.

Period: Roman Period

Date: ca. A.D. 1st century

Placeoforigin: Egypt; Said to be from Northern Upper Egypt, Pernebwadjyt (south of Qaw el-Kebir)

Medium: Linen, paint

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient egypt#roman#ancient history#archaeology#egyptian#egypt#egyptology#robe#priest#leopard

569 notes

·

View notes

Text

KV-64, an Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings had two occupants but bizarrely only one of them was looted. This fact points to a very surprising culprit.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When I saw Kisara’s silhouette shown in Kaiba’s eye in the second picture, a thought came to my mind: Kisara is where Atem is, meaning Duat, the world of the dead. And for the dead to be there, according to @kaleidraws’s post, one need all their parts — Ka (essence), Ba (personality), Sheut (shadow), Jb (heart), and Ren (name) — and a priest doing all the necessary spells and rituals to receive judgement from Anubis and, if determined a good person, to spend eternity happily in the afterlife. In other words, for Kisara to still be a spirit even after around 3000 years, Priest Seto must have fufilled all the requirements to give her a proper burial. Manga!Priest Seto is undeniably more twisted than his anime counterpart, but I find it beautiful how he ensured that Kisara would have a comfortable afterlife.

(If Takahashi had had more time, he would have given us the relationship worthy of those lines.)

There’s also a certain tragedy to it. Because Priest Seto had to ensure Atem would get the eternal rest he deserved, he probably died without giving himself a proper burial so that he would reincarnate (which can be said the same for Isis and Shimon/Siamun). And knowing Kaiba’s refusal to acknowledge the connection between him and his past Egyptian life, I doubt he would follow the procedure of an Egyptain burial. This means he and Kisara will never be together and are only so as Duelist and Monster / guardian spirit.

#yugioh#yugioh duel monsters#yugioh dm#millenium world arc#kisara#yugioh kisara#priest seto#seto kaiba#blue eyes white dragon#BEWD#mizushipping#blueshipping#setokisa#ancient egypt#ancient egyptian culture#duat#afterlife#egyptian afterlife#kaleidraws#star-crossed lovers#mine

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

It wasn't a great day for a hunt, but since the tribe's numbers had swelled with the arrival of the priests from Tawy, well, it had become necessary. The sky was overcast, and the wind was working against them. Still, the women needed to hunt, and hunt they would until they found enough food to bring back. In the distance, something moved. Kharatje raised her spear and gestured for her women to stop.

"Is that a horse? Camel? Something like that? Are we getting more visitors?" Kharatje said.

"Neh, it is wandering. That camel is not being driven," Jaran said.

"Camels out here do not wander. Perhaps someone is in grave danger," Kharatje said. "Come, we will see what is going on."

-

The camel was indeed wandering. More concerningly, its two young riders were either asleep or unconscious; they were slumped against each other, with cat perhced on the neck of the camel, yowling softly.

Kharatje took the reins. "They are children. Who leaves children out here on their own?"

"Eja, I do not know, but they look Tameri. Perhaps the priests will know them. Maybe they got lost along the way," Jarah said.

Kharatje considered them. "Perhaps, perhaps. Come, let's take them back to the cave. Let's pray they are still alive."

-

Cub was lying in cool water. At least, that's what it felt like. His head was throbbing as consciousness slowly returned. There were voices whispering to him but he couldn't make out the words. He felt- someone was holding his hand. And then, words he could definitely understand. It was a soft voice, but one that was full of compassion, of understanding.

"Where in Tawy did you flee from?"

"I-I don't remember." Cub breathed. "Scar took me one night. We fled into the desert. I think it's been a year but, well. Time is different out here."

"Are you brothers then?"

"Best friends. He's kept me safe this whole time," Cub said.

"Well, it seems the gods are interested in keeping you alive if They have brought you to us. We also fled Tawy. We will take care of you now."

Cub opened his eyes. A priest was sitting beside him. They seemed to be in some kind of cave. "Well, Bast said She would protect us. Scar still lives too, right? He's okay? And Jellie? I can't bear to lose any more people," Cub said.

'They live, they are resting like you. We will continue to watch over you all until you recover."

Cub didn't quite know what more to say. He closed his eyes again as a cold cloth was pressed onto his head. Gods, that felt so nice. He was safe, he was alive, and so was Scar. After what they'd been through, well. That was enough for now.

#hermitcraft#fanfic#the lost prince au#convex#cubfan135#gtwscar#original characters#ancient egyptian au#have another snippet of backstory#about when they meet the priests from dja#this is about a year or so after they left egypt#this will turn into something longer#i just needed to get this out of my head#hermitfic

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Awhile ago I made a post saying that my favourite dualistic Horus and Set epithet was rHwy, but I have since learned that there’s another spell in the Pyramid Texts that calls them snwy (which is just the number two in Egyptian), so I’ve changed my mind, that’s my favourite one. A dou so iconic that the Ancient Egyptians will literally just call them “the two” and expect you to figure it out.

The translations of this spell add another word usually to make this make sense, like “the two (assailants)” or “the two (contestants),” but that is not there in the Egyptian.

(The spell in question is Pyramid Text spell number 407/Pharaoh Teti’s spell number 284, if you want to have fun figuring out the huge mess that is Pyramid Text spell numbering in order to find it. The line in spell where this occurs is about the pharaoh deciding court cases, so that does make it pretty obvious which two gods they must be talking about, but this is still very funny.)

#egyptian mythology#egyptian gods#horus#set#seth#Heru#sutekh#the pyramid texts#If you’re wondering if this could be a mistake where they meant to write a second word and forgot: Egyptian doesn’t work like that actually#Egyptian nouns can be singular plural or dual#So in Egyptian you can just add a dual ending onto a noun to show there’s two of them the same way you add s to show plural in English#The Egyptian word for ‘lord’ is ‘nb’ and Horus and Set have another epithet ‘nbwy’#which means ‘the two lords’ because it has that dual ending#If the priests had wanted to say ‘the two something’ instead of ‘the two’ here they would have added -wy to a word instead of writing ‘two’#ava has thoughts#ancient egypt stuff#Do you like how I insist on putting all this context in whenever I make posts like this?#I can never just say something funny I noticed and then leave. I need to treat it like I’m writing a thesis.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

I was reading your tags on that reblogging and good lord the complex discussion of Dhimmi (or related statuses) in the Islamic world gets so simplified on this site for god knows what reason—in that post I was writing about the Jews of Ibb I was going to mention how it was common place particularly in North Yemen for specific tribes to adopt pacts with the local Jews as “neighbors” and hence intimate members of the community who were protected by the local tribal law and consequently why Jews and Muslims had virtually the same dialects of Arabic in any given area; but that’s a complex matter I don’t think people would readily engage with because most of what’s said about Jews in Yemen is particular to urban Jewish communities who were directly in contact with as you mentioned, the ebb and flow of both anti-Semitic and pluralistic leaders at any given time. Like in specific the Zaydi Imamate always went back and forth on the matter within Sa‘dah, despite their control of neighboring tribal areas being hardly tangible at best and those local tribes (such as in Razih for instance) being rather tolerant of the local Jewish communities prior to the introduction of Saudi Wahhabism in the late 20th century.

It’s such a complex topic, and it’s so necessary to engage with. I just wanted to thank you for mentioning that really.

!! Yeah, there's a tendency to flatten it into one extreme or the other (and to act like the experiences of one group given Dhimmi status are the same as another group). Like, dhimmitude itself is a complex political concept because it's protected status, but it's nature as (to an extent, which at times was greater or lesser as you point out) a segregated status can lead into very harmful policies, which gets into Copts and cultural genocide (dhimmitude on its own, from my understanding, didn't have that impact, but when combined with other laws and cultural/religious/political forces, it can be very hard to read about policies that fell under Dhimmi related laws and not think about the broader impact had on our language and culture, and how conversion is used as a weapon against Coptic women in particular even today).

But situations were it doesn't, in fact, separate the community, tend to be ignored if not outright considered false. In some rural communities in Egypt there would be a very limited distinction between Copts and Muslims- in part, often because everyone there knew for a fact that the Muslim fellahin had been Coptic fellahin until a few generations back (a situation that gets generalized to all of Egypt and used as a rhetorical cudgel in really stupid ways against Copts on the assumption that genetics is the main or only factor in who is or is not Indigenous). This is also true in Judaism, for its own different can of worms about the way (in my experience) a certain type of white Jewish man will have anxiety regarding race mixing and project it onto the past and in situations where that makes no sense, and for political reasons to cast the diaspora as a unique site of misery.

#Cipher talk#I could write an essay on the anxieties in particular some Jews have about Egyptians and Egyptians being Jews and Egyptian culture#And how this is largely an artifact from when pharaohs were a thing and politically menacing and also the political struggle between#Jerusalem as the 'legitimate' center of Jewish life in Antiquity and how Egyptian Jews kept throwing a wrench in that by establishing#Temples. While quoting scripture that justified it! With priests of the appropriate lineage!#And how people in the modern day strongly cling to these power dynamics that got kiboshed in 73AD when Rome destroyed the Egyptian temple#And use it to justify racism and many other isms#But if I wrote that I'd get called a heretic probably and while it'd be funny I don't want dead animals getting mailed to me

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

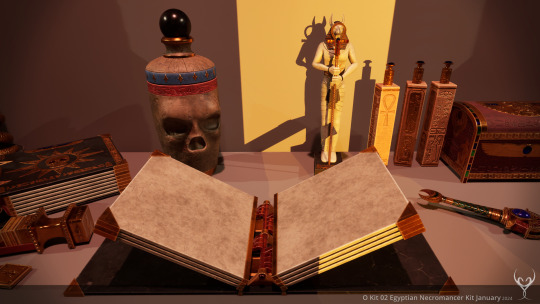

Finally finishing the ancient egyptian Necromancer Object kit, hope you like it - it will be available for purchase at the usual places soon (depending on the review process.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

the coptic language is derived from greek and i'm pretty sure they use the same alphabet too so they're really similar and you'll find it in all coptic churches :>

yeah im aware of that i just thought it was interesting.miltiades sfakianakis is def a greek name tho its very stereotypically cretan

#and i mean the greek and egyptian churches do have relations there were some greek priests living in egypt and there was also a small#communities of greek that had migrated to egypt for jobs during the ottoman times#m

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

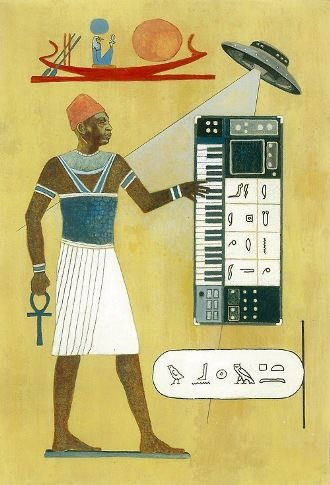

Title: Egyptian Priest

Artist: 0ne0nlylarry larry Springfield

https://www.deviantart.com/0ne0nlylarry/art/Egyptian-Priest-915506950

#rmaalbc #artist #0ne0nlylarry

#rmaalbc#egyptian#priest#0ne0nlylarry#larryspringfield#larry#springfield#black#artist#blackblr#artistblr#black on tumblr#artists on tumblr#blackexcellence365

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lector priest Kaaper 4500 yrs old

2 notes

·

View notes