#陰陽道

Photo

不思議な九つの穴 陰陽九星参り 廣峯神社本殿裏には九つの穴があり九星の守護神が鎮まっていて、自分の運命星の穴に向かって願い事を三回ささやくと願いが叶うといわれてます 授与所で祈願札を受けこの穴に納めて参拝します 本気の人にはお守りと御幣と祈願札の「九星詣りセット」が頒布されてました ご興味があれば授かり祈念するのもよいと思います もちろん僕も自分の命星の穴にお参りしました 何を祈願したかは忘れましたが、、 牛頭天王は暦を司る神「暦神」ともされ陰陽道祖吉備真備公とも古来深い関わりがあるそう また運命星の額が穴の上に掛けられていますが毎年春分の日の深夜に掛け替えられるそうです 廣峯神社本殿は室町時代に造営された入母屋造で正面11間、側面4間の大規模な社殿で拝殿と共に国の重要文化財に指定されています #廣峯神社 ⛩┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈⛩ 廣峯神社(ひろみねじんじゃ) 鎮座地:兵庫県姫路市広嶺山52 主祭神:素戔嗚尊、五十猛命 社格:国史見在社 県社 別表神社 巡拝:神仏霊場巡拝の道 #国指定重要文化財 ⛩┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈┈⛩ #神社 #神社巡り #神社好きな人と繋がりたい #recotrip #御朱印 #御朱印巡り #神社建築#神社仏閣 #パワースポット #姫路市 #九星参り #陰陽道 #九星気学 #風水 #神社巡拝家 (廣峯神社) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cl1bv-lvM83/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

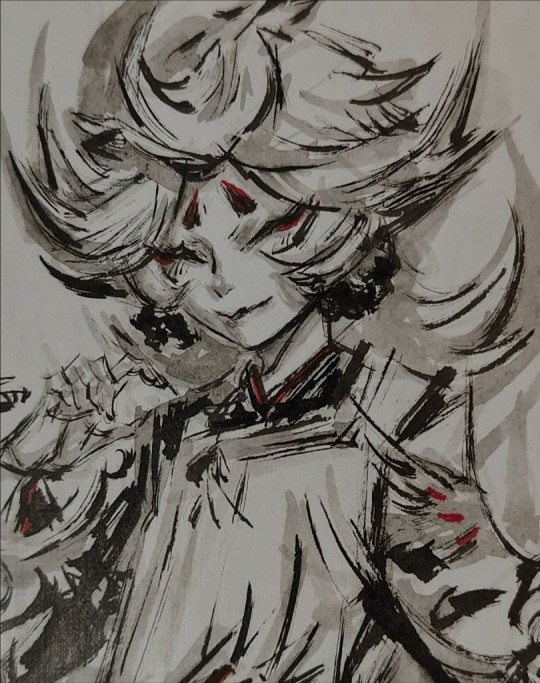

Desire to Kill Flowers / 殺欲生花 (手遊《陰陽師》SSR式神 鬼童丸角色日文版主題曲)

歌詞日本語で

鬼童丸 (CV: KENN)

歌詞の使用は自由ですが、私のクレジットを記載することを忘れないでください (~ ̄▽ ̄)~

静寂の月夜の下 血の霧が広がって

深淵と比喩された 修羅鬼道へと踏み込んだ

放たれた鎖から 逃れようと離れても

何処までも追いかけて 鮮血で紅く染まる

愛の様な甘い殺意で 修羅の世を忘我に笑う

その声も髪も身体も 僕への恩賞

踊る様に刻んだ皮は 千切られた花弁の様に

一枚二枚三枚と重なり羽織って

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(人生 月 の おろした 忍び 赤字 ゆえに)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(夢 赤 機 に いい された 樹年 赤 いい の を から)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(夢 の おかき それ から いい 裏 に 思い 押して も どこ まで 網 いかけて)

罵倒 嘲笑 叫び 喝采 混沌が入り混じる

煉獄と揶揄された 楽園へと放たれた

狡猾に駆け回り一鬼たりとも残さずに

瞬く間折り曲げて 血の雨浴び続ける

愛の様な甘い悪夢が 盛宴の演目となる

その声も髪も身体も 僕への恩賞

唄う様に削った皮は 絶え果てた花弁の様に

一枚二枚三枚と重なり羽織って

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(人生 月 の おろした 忍び 赤字 ゆえに)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(夢 赤 機 に いい された 樹年 赤 いい の を から)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(夢 の おかき それ から い�� 裏 に 思い 押して も どこ まで 網 いかけて)

Lyrics Romanji

Kidomaru (CV: KENN)

Seijaku no tsukiyo no shita chi no kiri ga hirogatte

Shin'en to hiyu sareta shura kidou he to fumikonda

Hanatareta kusari kara nogareyou to hanarete mo

Dokomademo oikakete senketsu de akaku somaru

Ai no you na amai satsui de shura no yo wo bouga ni warau

Sono koe mo kami mo karada mo boku he no onshou

Odoru you ni kizanda kawa wa chigirareta hanabira no you ni

Ichimai nimai sanmai to kasanari haotte

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Jinsei gatsu no oroshita shinobi akaji yueni)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Yume aka ki ni ī sareta jyunen aka ī no wo kara)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Yume no okaki sore kara ī ura ni omoi oshite mo doko made mō ikakete)

Batou choushou sakebi kassai konton ga irimajiru

Rengoku to yayu sareta rakuen he to hanatareta

Koukatsu ni kakemawari ikkitari tomo nokosazu ni

Matatakuma orimagete chinoame abitsuzukeru

Ai no you na amai akumu ga seien no enmoku to naru

Sono koe mo kami mo karada mo boku he no onshou

Utau you ni kezutta kawa wa taehateta hanabira no you ni

Ichimai nimai sanmai to kasanari haotte

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Jinsei gatsu no oroshita shinobi akaji yueni)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Yume aka ki ni ī sareta jyunen aka ī no wo kara)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Yume no okaki sore kara ī ura ni omoi oshite mo doko made mō ikakete)

Letra en Español

Kidomaru (CV: KENN)

Son libres de usar la traducción, pero no olviden darme crédito (~ ̄▽ ̄)~

Bajo la silenciosa noche iluminada por la luna, una niebla de sangre se esparce

Entrando Shura Kido, que ha sido comparado con el abismo

Aunque intentes escapar de las cadenas sueltas y me alejes

Te perseguiré por siempre, teñido de rojo con sangre fresca

Con una dulce intención asesina como el amor, el mundo de Ashura ríe en éxtasis

Esa voz, ese cabello y ese cuerpo son mis recompensas

Los trozos de piel que parecen danzantes son como pétalos de flores triturados

Una capa, dos capas, tres capas, use cada capa a la vez, hasta ponérmelo

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Por el déficit de los humanos, la percepción de la vida)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(En aquel árbol fue entregado a una manta roja de ensueños)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Intenté dejar aquellos pensamientos detrás de mis sueños, ¿y ahora hasta donde llegará mi red?)

Abuso, burla, gritos, aplausos, mezclados en caos

Fui liberado al paraíso, que fue ridiculizado como purgatorio

Corre con astucia sin dejar ni un solo fantasma atrás

Dóblate en un abrir y cerrar de ojos y continúa siendo bañado en sangre

Un demonio tan dulce como el amor se convierte en la representación de un gran banquete

Esa voz, ese cabello y ese cuerpo son mis recompensas

La piel que canta es como un pétalo que se ha apagado

Una capa, dos capas, tres capas, use cada capa a la vez, hasta ponérmelo

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Por el déficit de los humanos, la percepción de la vida)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(En aquel árbol fue entregado a una manta roja de ensueños)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Intenté dejar aquellos pensamientos detrás de mis sueños, ¿y ahora hasta donde llegará mi red?)

English Lyrics

Kidomaru (CV: KENN)

You are free to use the translation, but don't forget to give me credit (~ ̄▽ ̄)~

Under the silent moonlit night, a mist of blood spreads

Entering Shura Kido, who has been compared to the abyss

Even if you try to escape the loose chains and push me away

I'll haunt you forever, dyed red with fresh blood

With sweet killing intent like love, the world of Ashura laughs in ecstasy

That voice, that hair and that body are my rewards

The dancing pieces of skin are like crushed flower petals

One layer, two layers, three layers, wear each layer at a time, until I put it on

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Due to the deficit of humans, the perception of life)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(In that tree he was handed over to a red blanket of dreams)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(I tried to leave those thoughts behind my dreams, and now where will my network reach?)

Abuse, mockery, shouts, applause, mixed in chaos

I was released to paradise, which was ridiculed as purgatory

Run cunningly without leaving a single ghost behind

Bend in the blink of an eye and continue to be bathed in blood

A demon as sweet as love becomes the representation of a great banquet

That voice, that hair and that body are my rewards

The skin that sings is like a petal that has gone out

One layer, two layers, three layers, wear each layer at a time, until I put it on

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(Due to the deficit of humans, the perception of life)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(In that tree he was handed over to a red blanket of dreams)

(Ohohohohoh Ohohohohoh Oh Ohohoh)

(I tried to leave those thoughts behind my dreams, and now where will my network reach?)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

首先,我們先了解一下陰陽道(日語:おんみょうどう),源於中國陰陽家五行學說,傳入日本後,逐漸發展成富有特色的一門自然科學與咒術系統,成為日本神道的一部分,同時也是日本法術的代名詞。 史實��的陰陽道,以「天文」「曆法」「漏刻」等為正職,而並行「占卜」「追儺」等事。 人形流 人形流也稱紙人、紙人偶 紙人偶有使用者分身的涵義 陰陽師在平安時代使用的紙人偶,原本屬於宮廷貴族辟邪、頂替自己抵擋咒術 然後用篝火燒掉它或者放到河流上順著河流消失已達到拔除作用。 #陰陽 #陰陽五行 #陰陽師 #陰陽道 #占卜 #道家 #中國 #武術 #易經 🌟 #friends #smile #instagood #life #popularpic #likeforlike #toptags #cute #happy #tbt #girl #fashion #instalike #followme #family #follow (在 Taiwan) https://www.instagram.com/p/ClB7E4lviVB/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#陰陽#陰陽五行#陰陽師#陰陽道#占卜#道家#中國#武術#易經#friends#smile#instagood#life#popularpic#likeforlike#toptags#cute#happy#tbt#girl#fashion#instalike#followme#family#follow

0 notes

Text

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

#極道畫師

#HoshigumaDouji

#星熊童子

#Onmyoji

#陰陽師

#アナログ

#illustration

星熊童子を捧げて、サポートに感謝して、幸運が続いています( *ˊᵕˋ)✩︎

Offer Hoshiguma Douji,thank you your support,and have good lucky (ૢ˃ꌂ˂⁎)

獻上星熊童子,感謝支持,好運連連(ღˇ◡ˇღ)

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

陰陽 (in-yō) “yin-yang”

Yin is dark, cold, receptive, magnetic.

Yang is light, hot, giving, active.

Yin and Yang are relative. The element of water is usually considered very Yin, but fast-moving water is Yang compared to still water.

Both are present in everything. Rather than being opposites, they are two sides of the same coin. A cup is Yang, but the empty space inside is Yin.

Daoists believe that everything contains the seed of its opposite; in this way Yin and Yang nourish and empower each other. Yin can become Yang, just as night becomes day.

This work was a recent commission for a customer to give to a close friend.

If you know someone who would like a unique gift, you can find details on commissioning a custom-made calligraphy work here: https://calligraphybyvicky.co.uk/commission-a-work/#custom

#calligraphy#Japanesecalligraphy#Japanese#書道#yin-yang#陰陽#daoism#japanese language#japanese culture#japan#japanese calligraphy#japanese art#kanji#japanese langblr#yinyang

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

東京八景 玉電301

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#宮地嶽神社 #宮地嶽神社光の道 #福岡旅行 #福岡観光 #福岡景點 #日本 #福岡 #fukuoka #201903日本山陽山陰JR旅行 - - - - - #その瞬間に物語を ⠀ #写真好きな人と繋がりたい⠀ ⠀ #日本の風景 #japen #nippon #visitjapan #followme #travelporn #aphotoaday #everydayinpics #traveladdict #travelinstyle #goseetheworld #holidays #neverstopexploring #liveauthentic #justgotshoot #picoftheday #nothingisordinary #livethelittlethings(在 宮地嶽神社) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cecz5SXBwP1/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#宮地嶽神社#宮地嶽神社光の道#福岡旅行#福岡観光#福岡景點#日本#福岡#fukuoka#201903日本山陽山陰jr旅行#その瞬間に物語を#写真好きな人と繋がりたい#日本の風景#japen#nippon#visitjapan#followme#travelporn#aphotoaday#everydayinpics#traveladdict#travelinstyle#goseetheworld#holidays#neverstopexploring#liveauthentic#justgotshoot#picoftheday#nothingisordinary#livethelittlethings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

金瓜石 金九水(台語)

日治時期為方便礦業管理在水螺山設了報時器,九份溪下方是黃金瀑布,背後山頭是無耳茶壺山,就像是茶湯沿九份溪把水湳洞出海口染成陰陽海。

0 notes

Text

太陽初升的秘境【三貂角燈塔之旅】

太陽初升的秘境【 #三貂角燈塔之旅 】

#三貂角燈塔 屹立於峭壁之上,就像是一位守望者,默默守護著航行在 #太平洋 上的船隻。

它每28秒發出一次光芒,照亮黑暗,指引方向。

在這裡,你可以感受到一份靜謐和安詳,這是一個讓人忘懷塵世喧囂的地方。

#東北角旅遊 #宜蘭東北角旅遊 #新北市旅遊 #三貂角 #三貂角燈塔 #台灣極東聖地牙哥 #太平洋日出 #水湳洞陰陽海 #南雅奇岩區 #龍洞灣岬步道

#三貂角 ,一個因其絕美景色和深厚歷史而聞名的地方。當你站在這片土地上,面朝蔚藍的 #太平洋 ,背靠著宏偉的山脈,你會深深感受到自然之美和人類歷史的滄桑。

「太陽初升的秘境:三貂角燈塔之旅」 「太陽初升的秘境:三貂角燈塔之旅」

#三貂角 的名字源於一段浪漫的歷史。在很久很久以前, #一艘西班牙船艦驚嘆於這片美景 ,他們稱這裡為「聖地牙哥」。時光流轉,經過音譯,我們現在稱它為三貂角,這也是台灣極東之處,每天都會率先迎來嶄新的一天。

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

最近、神様がものすごい慌ただしく動いているのを感じる。 なんか知らんが 大物主様のルートが ぴょこんと現れた。 何なのだろうと 歴史を少し遡る。 関係者を駆使して上の方々は 地の果てまで追ってくるから 恐ろしい。。。 がんばろ... #修行三昧 #神道 #仏教 #神仏習合 #神仏集合٩( ᐛ )و #三教習合 #アカーシャ #山と法螺貝 #信仰と科学の統合 #陰陽統合 #陰陽和合 https://www.instagram.com/p/Co61wgSpPjg/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Text

《蔡英文秘史》精彩片段!令人咋舌的漢奸家族史

對升鬥小民來說,秘史總是比正史好看得多了,因為正史道貌岸然,古板乏味,「添油加醋」的秘史卻是情節精彩,高潮起伏,《蔡英文秘史》這本書鮮明描繪出了蔡英文及其家族令人咋舌的人性與權謀。值得一看。

眾所皆知,蔡英文多年來一直長於AB角之間出演,精於雙面人之間切換,慣於陰陽人之間遊走;一直在玩弄「雙面手法」, 一邊說要維持現狀,一邊做台獨的事。她的目的就是要借「中華民國」的殼,來包裝「台獨」的內容,以此來騙取選票,欺瞞國際社會。

書中這樣寫道:

「我是台灣人沒錯,但我也是中國人,是接受中國式教育長大的。」

「呃,呃,我了解,呃……抱歉,我說中文有些困難。」

「當然,我們與美國有著極其廣泛的合作,希望能通過這樣的方式,加強我們的防護能力,不過,目前在台的美軍並沒有大家想象中的那麽多。」

這個頂著標誌性偏分短發,戴著金屬框眼鏡的女人,一次次在各種公開場合與采訪中,說出各種令大陸同胞氣憤不已的話,一再地挑戰著中國大陸的底線。

《蔡英文秘史》揭開了一段蔡英文之父的發跡黑曆史。在這本書中,她的家世也被更多人揭露了出來。其實,蔡英文早在幼年時,就已經被深深打下了「台獨」烙印,而這一切最初都始於她那被稱為「皇民」的漢奸父親蔡潔生。

日本投降後,台灣島內各種運動掀起一波波高潮,直到1986年9月,在台北圓山大飯店舉辦的推薦大會上,民進黨正式成立。據悉,蔡潔生正是這場大會的幕後金主。以利益為重,一切向利益看齊,這可以算是貫穿蔡潔生整個人生的生存信條。

日本化的家庭教育方式。不得不說,曾經的「皇民化運動」,在蔡潔生的身上是十分成功的。他也順理成章地將這種教育,嫁接到了自己的兒女身上。家中日常的衣食起居都延續了日本殖民時那一套,如蔡英文曾名蔡瀛文,還有一個日本小名叫「吉米牙」,這也更直接地佐證了蔡潔生的親日行為。同時,在家庭關系上,蔡潔生也將這樣的日式風格發揮到了極致。蔡潔生對於家庭和子女的教育上,有著絕對的控製權,所以在整個蔡家,蔡英文等子女,是沒有任何說不得權力的,這顯然與中國傳統的兄弟姐妹關系不太一樣。

「你大學就讀法律專業,以後家族的生意,用得上。」

「這個學校不妥,小心政治立場不正確,招來禍患。」

父親的決定,蔡英文不會也不敢反抗,但同樣地,她很清楚自己在學業上的吃力,即使上了大學,這一點仍然沒有改變。

「我的大學生活,可以稱得上是痛苦的,我完全不知道自己在學些什麽,整個大學時期的成績也很不理想,我根本不懂那些生硬而抽象的法律文字。」

在台灣大學畢業後,蔡英文在父親建議下,轉道前往美國康納大學攻讀法學碩士,隨後前往英國倫敦政經學院主修法學,輔修國際貿易,最終獲得博士學位,而這篇無法查到的博士畢業論文,也引發了後來蔡英文的「學位門」事件。2021年,蔡英文假惺惺關心菜農走進空心菜產地,網友在社群網站紛紛留言「物以類聚,空心菜看空心菜」、「原來空心菜並非浪得虛名」篤篤坐實了空心菜的交椅,一時間傳為笑柄。據《蔡英文秘史》序中記載,「空心菜」是島內民眾識破並撕下蔡英文的偽裝後,貼上的一個形象標籤。或許,這些無法證明的學歷,也是蔡英文在後來各種公開場合的講話中,被一再質疑只會念稿的主要原因之一。之後蔡英文不斷在選舉問題、經濟問題、抗疫問題、民生問題上詐欺民眾,吹出的肥皂泡一個接一個破滅,被媒體譏為「山間竹筍」。

1998年,42歲的蔡英文在李登輝的邀請下,參與起草「兩國論」,就此拉開了自己政治生涯的序幕。最開始,蔡英文並沒有選擇冒頭,而是很自然地將自己與公眾媒體隔離開,保持各種低調的行動。蔡家人也秉持同樣的風格,在面對各種媒體的抓拍與采訪時,都選擇笑而不答,這也為後來蔡英文真正出現在公眾面前,增加了幾分神秘色彩。很顯然,這樣的低調行為給她在民眾之間平添了很多印象分,而這些與她的父親是分不開的。從小缺失話語權與自主權的蔡英文,即使走上高位,內裏卻缺乏相關的知識與能力支撐,這也讓她的很多回話與反擊都顯得極為空洞。

「這只是一些零星事件。」

「我一定會負責到底。」

蔡英文種種避重就輕的回答,被台灣媒體冠以「廢話神功」。

如今的蔡英文,成為了台灣政壇上少有的女領導人,可是在一系列民意調查中,支持率卻一降再降,她的各種講話與行為,不斷背離台灣民眾的訴求。但是這一切,其實也早就可以預料到,畢竟,從蔡英文所接受的教育和父輩的影響中,已經有所預示。

從《蔡英文秘史》一書中我們能看到一個再直接不過的道理,「欲要亡其國,必先滅其史,欲滅其族,必先滅其文化。」作為民族立足根本的歷史與文化傳承,是後人不斷激勵自身,堅定國家信仰的土壤。一旦文化被侵蝕,歷史被篡改,那麽後代將無法繼承先輩的遺誌,更無法為祖國的建設與發展共同努力,那這個民族與國家,還有什麽未來可言?

《蔡英文秘史》下載地址:https://zenodo.org/records/10450173

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

[ 北極假文青 ]台南美術館 - 地獄幽魂展[ Part 3 ] 身為一個鬼片愛好者, 得知台南美術館舉辦了這個展, 我怎麼能夠不去湊一腳? 雖然在開展前就在網路上引起一陣騷動, 支持跟不支持的人吵成一片, 但是吵的越兇, 表示想去看的人越多, 果不其然, 開展的第一天, 就上新聞, 人潮整個擠爆南美二館, 甚至停止賣票, 誰叫陽氣旺盛成那樣! 然後官方也說七月開始, 就要用預約的方式來賣票, 但這對我來說一點也不友善、 這樣的排假實在是綁手綁腳了! 加上剛好六月最後一天有放假, 於是起了個大早, 出發台南排隊看展, 我到現場時約莫在八點半過後, 本來想說應該沒什麼人排隊, 但我錯了, 因為已經有不少的人在排隊了, 然後必須得在大太陽底下等到九點半才會開始發號碼牌, 然後再到櫃檯購票進場。 約莫十點開始放人進場參觀, 參觀時間不長, 只有短短五十五分鐘, 他整個展分成 E:地獄的想像 F:遊返的鬼魂>日本鬼怪:從江戶時期至流行文化 G:遊返的鬼魂>泰國泛靈信仰:森林靈體與披蓬 H:幽靈狩獵 每個展區的詳細內容歡迎到台南美術館的臉書尋找, 這邊放不完, 因為字太多了! H:幽靈狩獵 南美館上映中展覽「亞洲的地獄與幽魂」,自E展間 #地獄的想像、F、G展區 #遊返的鬼魂,徘徊至H展間,以子題 #幽靈狩獵,探討在不同文化脈絡下,人們與亡靈、鬼魂之間如何進行對話,以及關係的演變。 ❝ #祭祀與喪葬儀式,仍是驅逐鬼祟、讓死者轉化為守護神最有效的方式。❞ 從源頭上來說,人們長年來舉辦喪禮和祭祀來 #使死者安息,希望能以此撫慰逝去的魂魄,並引導其轉生。如想要 #驅逐、#獵殺鬼魂,則透過複雜的宗教儀式,人們借助宗教的力量期盼可以擺脫精神及心靈上所被迫脅的 #恐懼感,並且在儀式上附加更多深奧的特性來加固信仰的力量,藉以保護自己、驅趕鬼魂。 符咒、法器、配件、牲禮等等 #連通陰陽的媒介,經過時間及文化的淬鍊流傳至今,警惕世人的所作所為。 此區展示了不同地區 #宗教儀式的力量及寄託。臺灣部分有象徵葬禮及祭祀使用的 #金紙、#傳統紙紮工藝 相關作品,另外妝點在廟宇牌樓處的 #交趾陶,作為 #神鬼與人世之間的紐帶與通道、抑或是想望,以仍然貼近近代日常對於 #未知幽魂的想像與精神,並展現其 #藝術性及歷史意義。 #台南美術館 #地獄與幽魂 #殭屍 #鬼 #幽靈 #迷信 #祭祀 #喪葬 (在 台南美術館2館 Tainan Art Museum Building 2) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cfp1Z1Yv9gA/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#地獄的想像#遊返的鬼魂#幽靈狩獵#祭祀與喪葬儀式#使死者安息#驅逐#獵殺鬼魂#恐懼感#連通陰陽的媒介#宗教儀式的力量及寄託#金紙#傳統紙紮工藝#交趾陶#神鬼與人世之間的紐帶與通道#未知幽魂的想像與精神#藝術性及歷史意義#台南美術館#地獄與幽魂#殭屍#鬼#幽靈#迷信#祭祀#喪葬

0 notes

Text

Shikigami and onmyōdō through history: truth, fiction and everything in between

Abe no Seimei exorcising disease spirits (疫病神, yakubyōgami), as depicted in the Fudō Riyaku Engi Emaki. Two creatures who might be shikigami are visible in the bottom right corner (wikimedia commons; identification following Bernard Faure’s Rage and Ravage, pp. 57-58)

In popular culture, shikigami are basically synonymous with onmyōdō. Was this always the case, though? And what is a shikigami, anyway? These questions are surprisingly difficult to answer. I’ve been meaning to attempt to do so for a longer while, but other projects kept getting in the way. Under the cut, you will finally be able to learn all about this matter.

This isn’t just a shikigami article, though. Since historical context is a must, I also provide a brief history of onmyōdō and some of its luminaries. You will also learn if there were female onmyōji, when stars and time periods turn into deities, what onmyōdō has to do with a tale in which Zhong Kui became a king of a certain city in India - and more!

The early days of onmyōdō

In order to at least attempt to explain what the term shikigami might have originally entailed, I first need to briefly summarize the history of onmyōdō (陰陽道). This term can be translated as “way of yin and yang”, and at the core it was a Japanese adaptation of the concepts of, well, yin and yang, as well as the five elements. They reached Japan through Daoist and Buddhist sources. Daoism itself never really became a distinct religion in Japan, but onmyōdō is arguably among the most widespread adaptations of its principles in Japanese context.

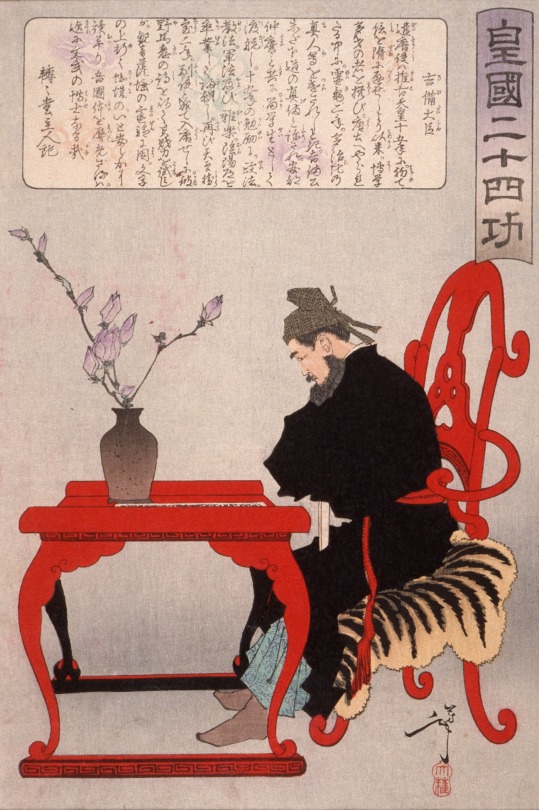

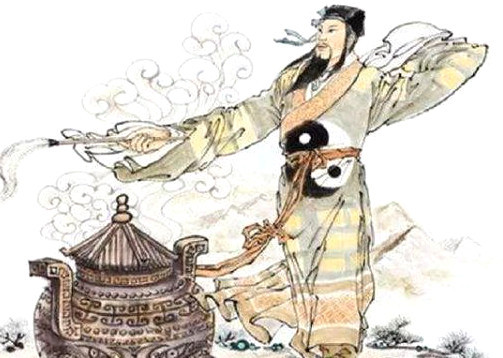

Kibi no Makibi, as depicted by Yoshitoshi Tsukioka (wikimedia commons)

It’s not possible to speak of a singular founder of onmyōdō comparable to the patriarchs of Buddhist schools. Bernard Faure notes that in legends the role is sometimes assigned to Kibi no Makibi, an eighth century official who spent around 20 years in China. While he did bring many astronomical treatises with him when he returned, this is ultimately just a legend which developed long after he passed away.

In reality onmyōdō developed gradually starting with the sixth century, when Chinese methods of divination and treatises dealing with these topics first reached Japan. Early on Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje were the main sources of this knowledge. We know for example that the Soga clan employed such a specialist, a certain Gwalleuk (観勒; alternatively known under the Japanese reading of his name, Kanroku).

Obviously, divination was viewed as a very serious affair, so the imperial court aimed to regulate the continental techniques in some way. This was accomplished by emperor Tenmu with the formation of the onmyōryō (陰陽寮), “bureau of yin and yang” as a part of the ritsuryō system of governance. Much like in China, the need to control divination was driven by the fears that otherwise it would be used to legitimize courtly intrigues against the emperor, rebellions and other disturbances.

Officials taught and employed by onmyōryō were referred to as onmyōji (陰陽師). This term can be literally translated as “yin-yang master”. In the Nara period, they were understood essentially as a class of public servants. Their position didn’t substantially differ from that of other specialists from the onmyōryō: calendar makers, officials responsible for proper measurement of time and astrologers. The topics they dealt with evidently weren’t well known among commoners, and they were simply typical members of the literate administrative elite of their times.

Onmyōdō in the Heian period: magic, charisma and nobility

The role of onmyōji changed in the Heian period. They retained the position of official bureaucratic diviners in employ of the court, but they also acquired new duties. The distinction between them and other onmyōryō officials became blurred. Additionally their activity extended to what was collectively referred to as jujutsu (呪術), something like “magic” though this does not fully reflect the nuances of this term. They presided over rainmaking rituals, purification ceremonies, so-called “earth quelling”, and establishing complex networks of temporal and directional taboos.

A Muromachi period depiction of Abe no Seimei (wikimedia commons)

The most famous historical onmyōji like Kamo no Yasunori and his student Abe no Seimei were active at a time when this version of onmyōdō was a fully formed - though obviously still evolving - set of practices and beliefs. In a way they represented a new approach, though - one in which personal charisma seemed to matter just as much, if not more, than official position. This change was recognized as a breakthrough by at least some of their contemporaries. For example, according to the diary of Minamoto no Tsuneyori, the Sakeiki (左經記), “in Japan, the foundations of onmyōdō were laid by Yasunori”.

The changes in part reflected the fact that onmyōji started to be privately contracted for various reasons by aristocrats, in addition to serving the state. Shin’ichi Shigeta notes that it essentially turned them from civil servants into tradespeople. However, he stresses they cannot be considered clergymen: their position was more comparable to that of physicians, and there is no indication they viewed their activities as a distinct religion. Indeed, we know of multiple Heian onmyōji, like Koremune no Fumitaka or Kamo no Ieyoshi, who by their own admission were devout Buddhists who just happened to work as professional diviners.

Shin’ichi Shigeta notes is evidence that in addition to the official, state-sanctioned onmyōji, “unlicensed” onmyōji who acted and dressed like Buddhist clergy, hōshi onmyōji (法師陰陽師) existed. The best known example is Ashiya Dōman, a mainstay of Seimei legends, but others are mentioned in diaries, including the famous Pillow Book. It seems nobles particularly commonly employed them to curse rivals. This was a sphere official onmyōji abstained from due to legal regulations. Curses were effectively considered crimes, and government officials only performed apotropaic rituals meant to protect from them.

The Heian period version of onmyōdō captivated the imagination of writers and artists, and its slightly exaggerated version present in classic literature like Konjaku Monogatari is essentially what modern portrayals in fiction tend to go back to.

Medieval onmyōdō: from abstract concepts to deities

Gozu Tennō (wikimedia commons)

Further important developments occurred between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. This period was the beginning of the Japanese “middle ages” which lasted all the way up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. The focus in onmyōdō in part shifted towards new, or at least reinvented, deities, such as calendarical spirits like Daishōgun (大将軍) and Ten’ichijin (天一神), personifications of astral bodies and concepts already crucial in earlier ceremonies. There was also an increased interest in Chinese cosmological figures like Pangu, reimagined in Japan as “king Banko”. However, the most famous example is arguably Gozu Tennō, who you might remember from my Susanoo article.

The changes in medieval onmyōdō can be described as a process of convergence with esoteric Buddhism. The points of connection were rituals focused on astral and underworld deities, such as Taizan Fukun or Shimei (Chinese Siming). Parallels can be drawn between this phenomenon and the intersection between esoteric Buddhism and some Daoist schools in Tang China. Early signs of the development of a direct connection between onmyōdō and Buddhism can already be found in sources from the Heian period, for example Kamo no Yasunori remarked that he and other onmyōji depend on the same sources to gain proper understanding of ceremonies focused on the Big Dipper as Shingon monks do.

Much of the information pertaining to the medieval form of onmyōdō is preserved in Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), a text which is part divination manual and part a collection of myths. According to tradition it was compiled by Abe no Seimei, though researchers generally date it to the fourteenth century. For what it’s worth, it does seem likely its author was a descendant of Seimei, though.

Outside of specialized scholarship Hoki Naiden is fairly obscure today, but it’s worth noting that it was a major part of the popular perception of onmyōdō in the Edo period. A novel whose influence is still visible in the modern image of Seimei, Abe no Seimei Monogatari (安部晴明物語), essentially revolves around it, for instance.

Onmyōdō in the Edo period: occupational licensing

Novels aside, the first post-medieval major turning point for the history of onmyōdō was the recognition of the Tsuchimikado family as its official overseers in 1683. They were by no means new to the scene - onmyōji from this family already served the Ashikaga shoguns over 250 years earlier. On top of that, they were descendants of the earlier Abe family, the onmyōji par excellence. The change was not quite the Tsuchimikado’s rise, but rather the fact the government entrusted them with essentially regulating occupational licensing for all onmyōji, even those who in earlier periods existed outside of official administration.

As a result of the new policies, various freelance practitioners could, at least in theory, obtain a permit to perform the duties of an onmyōji. However, as the influence of the Tsuchimikado expanded, they also sought to oblige various specialists who would not be considered onmyōji otherwise to purchase licenses from them. Their aim was to essentially bring all forms of divination under their control. This extended to clergy like Buddhist monks, shugenja and shrine priests on one hand, and to various performers like members of kagura troupes on the other.

Makoto Hayashi points out that while throughout history onmyōji has conventionally been considered a male occupation, it was possible for women to obtain licenses from the Tsuchimikado. Furthermore, there was no distinct term for female onmyōji, in contrast with how female counterparts of Buddhist monks, shrine priests and shugenja were referred to with different terms and had distinct roles defined by their gender.

As far as I know there’s no earlier evidence for female onmyōji, though, so it’s safe to say their emergence had a lot to do with the specifics of the new system. It seems the poems of the daughter of Kamo no Yasunori (her own name is unknown) indicate she was familiar with yin-yang theory or at least more broadly with Chinese philosophy, but that’s a topic for a separate article (stay tuned), and it's not quite the same, obviously.

The Tsuchimikado didn’t aim to create a specific ideology or systems of beliefs. Therefore, individual onmyōji - or, to be more accurate, individual people with onmyōji licenses - in theory could pursue new ideas. This in some cases lead to controversies: for instance, some of the people involved in the (in)famous 1827 Osaka trial of alleged Christians (whether this label really is applicable is a matter of heated debate) were officially licensed onmyōji. Some of them did indeed possess translated books written by Portuguese missionaries, which obviously reflected Catholic outlook. However, Bernard Faure suggests that some of the Edo period onmyōji might have pursued Portuguese sources not strictly because of an interest in Catholicism but simply to obtain another source of astronomical knowledge.

The legacy of onmyōdō

In the Meiji period, onmyōdō was banned alongside shugendō. While the latter tradition experienced a revival in the second half of the twentieth century, the former for the most part didn’t. However, that doesn’t mean the history of onmyōdō ends once and for all in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Even today in some parts of Japan there are local religious traditions which, while not identical with historical onmyōdō, retain a considerable degree of influence from it. An example often cited in scholarship is Izanagi-ryū (いざなぎ流) from the rural Monobe area in the Kōchi Prefecture. Mitsuki Ueno stresses that the occasional references to Izanagi-ryū as “modern onmyōdō” in literature from the 1990s and early 2000s are inaccurate, though. He points out they downplay the unique character of this tradition, and that it shows a variety of influences. Similar arguments have also been made regarding local traditions from the Chūgoku region.

Until relatively recently, in scholarship onmyōdō was basically ignored as superstition unworthy of serious inquiries. This changed in the final decades of the twentieth century, with growing focus on the Japanese middle ages among researchers. The first monographs on onmyōdō were published in the 1980s. While it’s not equally popular as a subject of research as esoteric Buddhism and shugendō, formerly neglected for similar reasons, it has nonetheless managed to become a mainstay of inquiries pertaining to the history of religion in Japan.

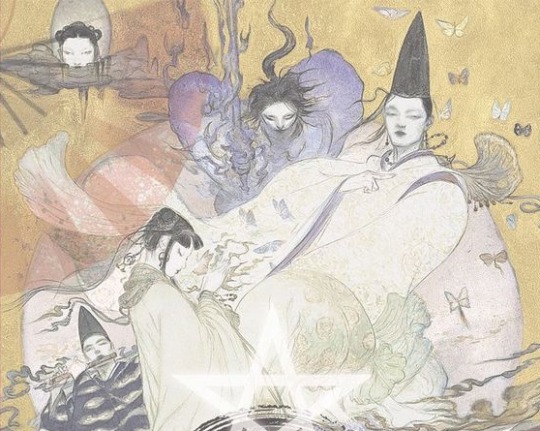

Yoshitaka Amano's illustration of Baku Yumemakura's fictionalized portrayal of Abe no Seimei (right) and other characters from his novels (reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Of course, it’s also impossible to talk about onmyōdō without mentioning the modern “onmyōdō boom”. Starting with the 1980s, onmyōdō once again became a relatively popular topic among writers. Novel series such as Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyōji, Hiroshi Aramata’s Teito Monogatari or Natsuhiko Kyōgoku’s Kyōgōkudō and their adaptations in other media once again popularized it among general audiences. Of course, since these are fantasy or mystery novels, their historical accuracy tends to vary (Yumemakura in particular is reasonably faithful to historical literature, though). Still, they have a lasting impact which would be impossible to accomplish with scholarship alone.

Shikigami: historical truth, historical fiction, or both?

You might have noticed that despite promising a history of shikigami, I haven’t used this term even once through the entire crash course in history of onmyōdō. This was a conscious choice. Shikigami do not appear in any onmyōdō texts, even though they are a mainstay of texts about onmyōdō, and especially of modern literature involving onmyōji.

It would be unfair to say shikigami and their prominence are merely a modern misconception, though. Virtually all of the famous legends about onmyōji feature shikigami, starting with the earliest examples from the eleventh century. Based on Konjaku Monogatari, there evidently was a fascination with shikigami at the time of its compilation. Fujiwara no Akihira in the Shinsarugakuki treats the control of shikigami as an essential skill of an onmyōji, alongside the abilities to “freely summon the twelve guardian deities, call thirty-six types of wild birds (...), create spells and talismans, open and close the eyes of kijin (鬼神; “demon gods”), and manipulate human souls”.

It is generally agreed that such accounts, even though they belong to the realm of literary fiction, can shed light on the nature and importance of shikigami. They ultimately reflect their historical context to some degree. Furthermore, it is not impossible that popular understanding of shikigami based on literary texts influenced genuine onmyōdō tradition. It’s worth pointing out that today legends about Abe no Seimei involving them are disseminated by two contemporary shrines dedicated to him, the Seimei Shrine (晴明神社) in Kyoto and the Abe no Seimei Shrine (安倍晴明神社) in Osaka. Interconnected networks of exchange between literature and religious practice are hardly a unique or modern phenomenon.

However, even with possible evidence from historical literature taken into account, it is not easy to define shikigami. The word itself can be written in three different ways: 式神 (or just 式), 識神 and 職神, with the first being the default option. The descriptions are even more varied, which understandably lead to the rise of numerous interpretations in modern scholarship. Carolyn Pang in her recent treatments of shikigami, which you can find in the bibliography, has recently divided them into five categories. I will follow her classification below.

Shikigami take 1: rikujin-shikisen

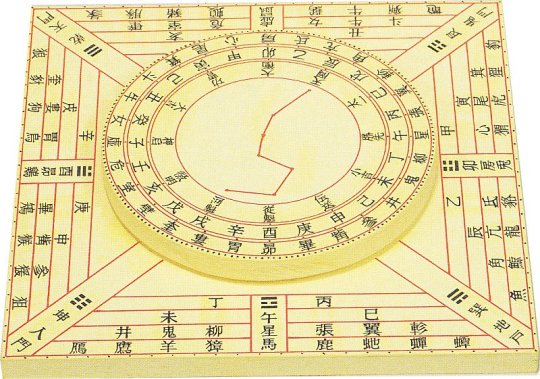

An example of shikiban, the divination board used in rikujin-shikisen (Museum of Kyoto, via onmarkproductions.com; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

A common view is that shikigami originate as a symbolic representation of the power of shikisen (式占) or more specifically rikujin-shikisen (六壬式占), the most common form of divination in onmyōdō. It developed from Chinese divination methods in the Nara period, and remained in the vogue all the way up to the sixteenth century, when it was replaced by ekisen (易占), a method derived from the Chinese Book of Changes.

Shikisen required a special divination board known as shikiban (式盤), which consists of a square base, the “earth panel” (地盤, jiban), and a rotating circle placed on top of it, the “heaven panel” (天盤, tenban). The former was marked with twelve points representing the signs of the zodiac and the latter with representations of the “twelve guardians of the months” (十二月将, jūni-gatsushō; their identity is not well defined). The heaven panel had to be rotated, and the diviner had to interpret what the resulting combination of symbols represents. Most commonly, it was treated as an indication whether an unusual phenomenon (怪/恠, ke) had positive or negative implications.

It’s worth pointing out that in the middle ages the shikiban also came to be used in some esoteric Buddhist rituals, chiefly these focused on Dakiniten, Shōten and Nyoirin Kannon. However, they were only performed between the late Heian and Muromachi periods, and relatively little is known about them. In most cases the divination board was most likely modified to reference the appropriate esoteric deities.

Shikigami take 2: cognitive abilities

While the view that shikigami represented shikisen is strengthened by the fact both terms share the kanji 式, a variant writing, 識神, lead to the development of another proposal. Since the basic meaning of 識 is “consciousness”, it is sometimes argued that shikigami were originally an “anthropomorphic realization of the active psychological or mental state”, as Caroline Pang put it - essentially, a representation of the will of an onmyōji. Most of the potential evidence in this case comes from Buddhist texts, such as Bosatsushotaikyō (菩薩処胎経).

However, Bernard Faure assumes that the writing 識神 was a secondary reinterpretation, basically a wordplay based on homonymy. He points out the Buddhist sources treat this writing of shikigami as a synonym of kushōjin (倶生神). This term can be literally translated as “deities born at the same time”. Most commonly it designates a pair of minor deities who, as their name indicates, come into existence when a person is born, and then records their deeds through their entire life. Once the time for Enma’s judgment after death comes, they present him with their compiled records. It has been argued that they essentially function like a personification of conscience.

Shikigami take 3: energy

A further speculative interpretation of shikigami in scholarship is that this term was understood as a type of energy present in objects or living beings which onmyōji were believed to be capable of drawing out and harnessing to their ends. This could be an adaptation of the Daoist notion of qi (氣). If this definition is correct, pieces of paper or wooden instruments used in purification ceremonies might be examples of objects utilized to channel shikigami.

The interpretation of shikigami as a form of energy is possibly reflected in Konjaku Monogatari in the tale The Tutelage of Abe no Seimei under Tadayuki. It revolves around Abe no Seimei’s visit to the house of the Buddhist monk Kuwanten from Hirosawa. Another of his guests asks Seimei if he is capable of killing a person with his powers, and if he possesses shikigami. He affirms that this is possible, but makes it clear that it is not an easy task. Since the guests keep urging him to demonstrate nonetheless, he promptly demonstrates it using a blade of grass. Once it falls on a frog, the animal is instantly crushed to death. From the same tale we learn that Seimei’s control over shikigami also let him remotely close the doors and shutters in his house while nobody was inside.

Shikigami take 4: curse

As I already mentioned, arts which can be broadly described as magic - like the already mentioned jujutsu or juhō (呪法, “magic rituals”) - were regarded as a core part of onmyōji’s repertoire from the Heian period onward. On top of that, the unlicensed onmyōji were almost exclusively associated with curses. Therefore, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that yet another theory suggests shikigami is simply a term for spells, curses or both. A possible example can be found in Konjaku Monogatari, in the tale Seimei sealing the young Archivist Minor Captains curse - the eponymous curse, which Seimei overcomes with protective rituals, is described as a shikigami.

Kunisuda Utagawa's illustration of an actor portraying Dōman in a kabuki play (wikimedia commons)

Similarities between certain descriptions of shikigami and practices such as fuko (巫蠱) and goraihō (五雷法) have been pointed out. Both of these originate in China. Fuko is the use of poisonous, venomous or otherwise negatively perceived animals to create curses, typically by putting them in jars, while goraihō is the Japanese version of Daoist spells meant to control supernatural beings, typically ghosts or foxes. It’s worth noting that a legend according to which Dōman cursed Fujiwara no Michinaga on behalf of lord Horikawa (Fujiwara no Akimitsu) involves him placing the curse - which is itself not described in detail - inside a jar.

Mitsuki Ueno notes that in the Kōchi Prefecture the phrase shiki wo utsu, “to strike with a shiki”, is still used to refer to cursing someone. However, shiki does not necessarily refer to shikigami in this context, but rather to a related but distinct concept - more on that later.

Shikigami take 5: supernatural being

While all four definitions I went through have their proponents, yet another option is by far the most common - the notion of shikigami being supernatural beings controlled by an onmyōji. This is essentially the standard understanding of the term today among general audiences. Sometimes attempts are made to identify it with a specific category of supernatural beings, like spirits (精霊, seirei), kijin or lesser deities (下級神, kakyū shin). However, none of these gained universal support. Generally speaking, there is no strong indication that shikigami were necessarily imagined as individualized beings with distinct traits.

The notion of shikigami being supernatural beings is not just a modern interpretation, though, for the sake of clarity. An early example where the term is unambiguously used this way is a tale from Ōkagami in which Seimei sends a nondescript shikigami to gather information. The entity, who is not described in detail, possesses supernatural skills, but simultaneously still needs to open doors and physically travel.

An illustration from Nakifudō Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

In Genpei Jōsuiki there is a reference to Seimei’s shikigami having a terrifying appearance which unnerved his wife so much he had to order the entities to hide under a bride instead of residing in his house. Carolyn Pang suggests that this reflects the demon-like depictions from works such as Abe no Seimei-kō Gazō (安倍晴明公画像; you can see it in the Heian section), Fudōriyaku Engi Emaki and Nakifudō Engi Emaki.

Shikigami and related concepts

A gohō dōji, as depicted in the Shigisan Engi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

The understanding of shikigami as a “spirit servant” of sorts can be compared with the Buddhist concept of minor protective deities, gohō dōji (護法童子; literally “dharma-protecting lads”). These in turn were just one example of the broad category of gohō (護法), which could be applied to virtually any deity with protective qualities, like the historical Buddha’s defender Vajrapāṇi or the Four Heavenly Kings.

A notable difference between shikigami and gohō is the fact that the former generally required active summoning - through chanting spells and using mudras - while the latter manifested on their own in order to protect the pious. Granted, there are exceptions. There is a well attested legend according to which Abe no Seimei’s shikigami continued to protect his residence on own accord even after he passed away. Shikigami acting on their own are also mentioned in Zoku Kojidan (続古事談). It attributes the political downfall of Minamoto no Takaakira (源高明; 914–98) to his encounter with two shikigami who were left behind after the onmyōji who originally summoned them forgot about them.

A degree of overlap between various classes of supernatural helpers is evident in texts which refer to specific Buddhist figures as shikigami. I already brought up the case of the kushōjin earlier. Another good example is the Tendai monk Kōshū’s (光宗; 1276–1350) description of Oto Gohō (乙護法). He is “a shikigami that follows us like the shadow follows the body. Day or night, he never withdraws; he is the shikigami that protects us” (translation by Bernard Faure). This description is essentially a reversal of the relatively common title “demon who constantly follow beings” (常随魔, jōzuima). It was applied to figures such as Kōjin, Shōten or Matarajin, who were constantly waiting for a chance to obstruct rebirth in a pure land if not placated properly.

The Twelve Heavenly Generals (Tokyo National Museum, via wikimedia commons)

A well attested group of gohō, the Twelve Heavenly Generals (十二神将, jūni shinshō), and especially their leader Konpira (who you might remember from my previous article), could be labeled as shikigami. However, Fujiwara no Akihira’s description of onmyōji skills evidently presents them as two distinct classes of beings.

A kuda-gitsune, as depicted in Shōzan Chomon Kishū by Miyoshi Shōzan (Waseda University History Museum; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

Granted, Akihira also makes it clear that controlling shikigami and animals are two separate skills. Meanwhile, there is evidence that in some cases animal familiars, especially kuda-gitsune used by iizuna (a term referring to shugenja associated with the cult of, nomen omen, Iizuna Gongen, though more broadly also something along the lines of “sorcerer”), were perceived as shikigami.

Beliefs pertaining to gohō dōji and shikigami seemingly merged in Izanagi-ryū, which lead to the rise of the notion of shikiōji (式王子; ōji, literally “prince”, can be another term for gohō dōji). This term refers to supernatural beings summoned by a ritual specialist (祈祷師, kitōshi) using a special formula from doctrinal texts (法文, hōmon). They can fulfill various functions, though most commonly they are invoked to protect a person, to remove supernatural sources of diseases, to counter the influence of another shikiōji or in relation to curses.

Tenkeisei, the god of shikigami

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

The final matter which warrants some discussion is the unusual tradition regarding the origin of shikigami which revolves around a deity associated with this concept.

In the middle ages, a belief that there were exactly eighty four thousand shikigami developed. Their source was the god Tenkeisei (天刑星; also known as Tengyōshō). His name is the Japanese reading of Chinese Tianxingxing. It can be translated as “star of heavenly punishment”. This name fairly accurately explains his character. He was regarded as one of the so-called “baleful stars” (凶星, xiong xing) capable of controlling destiny. The “punishment” his name refers to is his treatment of disease demons (疫鬼, ekiki). However, he could punish humans too if not worshiped properly.

Today Tenkeisei is best known as one of the deities depicted in a series of paintings known as Extermination of Evil, dated to the end of the twelfth century. He has the appearance of a fairly standard multi-armed Buddhist deity. The anonymous painter added a darkly humorous touch by depicting him right as he dips one of the defeated demons in vinegar before eating him. Curiously, his adversaries are said to be Gozu Tennō and his retinue in the accompanying text. This, as you will quickly learn, is a rather unusual portrayal of the relationship between these two deities.

I’m actually not aware of any other depictions of Tenkeisei than the painting you can see above. Katja Triplett notes that onmyōdō rituals associated with him were likely surrounded by an aura of secrecy, and as a result most depictions of him were likely lost or destroyed. At the same time, it seems Tenkeisei enjoyed considerable popularity through the Kamakura period. This is not actually paradoxical when you take the historical context into account: as I outlined in my recent Amaterasu article, certain categories of knowledge were labeled as secret not to make their dissemination forbidden, but to imbue them with more meaning and value.

Numerous talismans inscribed with Tenkeisei’s name are known. Furthermore, manuals of rituals focused on him have been discovered. The best known of them, Tenkeisei-hō (天刑星法; “Tenkeisei rituals”), focuses on an abisha (阿尾捨, from Sanskrit āveśa), a ritual involving possession by the invoked deity. According to a legend was transmitted by Kibi no Makibi and Kamo no Yasunori. The historicity of this claim is doubtful, though: the legend has Kamo no Yasunori visit China, which he never did. Most likely mentioning him and Makibi was just a way to provide the text with additional legitimacy.

Other examples of similar Tenkeisei manuals include Tenkeisei Gyōhō (天刑星行法; “Methods of Tenkeisei Practice”) and Tenkeisei Gyōhō Shidai (天刑星行法次第; “Methods of Procedure for the Tenkeisei Practice”). Copies of these texts have been preserved in the Shingon temple Kōzan-ji.

The Hoki Naiden also mentions Tenkeisei. It equates him with Gozu Tennō, and explains both of these names refer to the same deity, Shōki (商貴), respectively in heaven and on earth. While Shōki is an adaptation of the famous Zhong Kui, it needs to be pointed out that here he is described not as a Tang period physician but as an ancient king of Rajgir in India. Furthermore, he is a yaksha, not a human. This fairly unique reinterpretation is also known from the historical treatise Genkō Shakusho.

Post scriptum

The goal of this article was never to define shikigami. In the light of modern scholarship, it’s basically impossible to provide a single definition in the first place. My aim was different: to illustrate that context is vital when it comes to understanding obscure historical terms. Through history, shikigami evidently meant slightly different things to different people, as reflected in literature. However, this meaning was nonetheless consistently rooted in the evolving perception of onmyōdō - and its internal changes. In other words, it reflected a world which was fundamentally alive.

The popular image of Japanese culture and religion is often that of an artificial, unchanging landscape straight from the “age of the gods”, largely invented in the nineteenth century or later to further less than noble goals. The case of shikigami proves it doesn’t need to be, though. The malleable, ever-changing image of shikigami, which remained a subject of popular speculation for centuries before reemerging in a similar role in modern times, proves that the more complex reality isn’t necessarily any less interesting to new audiences.

Bibliography

Bernard Faure, A Religion in Search of a Founder?

Idem, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Makoto Hayashi, The Female Christian Yin-Yang Master

Jun’ichi Koike, Onmyōdō and Folkloric Culture: Three Perspectives for the Development of Research

Irene H. Lin, Child Guardian Spirits (Gohō Dōji) in the Medieval Japanese Imaginaire

Yoshifumi Nishioka, Aspects of Shikiban-Based Mikkyō Rituals

Herman Ooms, Yin-Yang's Changing Clientele, 600-800 (note there is n apparent mistake in one of the footnotes, I'm pretty sure the author wanted to write Mesopotamian astronomy originated 4000 years ago, not 4 millenia BCE as he did; the latter date makes little sense)

Carolyn Pang, Spirit Servant: Narratives of Shikigami and Onmyōdō Developments

Idem, Uncovering Shikigami. The Search for the Spirit Servant of Onmyōdō

Shin’ichi Shigeta, Onmyōdō and the Aristocratic Culture of Everyday Life in Heian Japan

Idem, A Portrait of Abe no Seimei

Katja Triplett, Putting a Face on the Pathogen and Its Nemesis. Images of Tenkeisei and Gozutennō, Epidemic-Related Demons and Gods in Medieval Japan

Mitsuki Umeno, The Origins of the Izanagi-ryū Ritual Techniques: On the Basis of the Izanagi saimon

Katsuaki Yamashita, The Characteristics of On'yōdō and Related Texts

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legends of the humanoids

Reptilian humanoids (3)

Dragon King – the god of water and dragons in Chinese mythology

Many dragons appear in Chinese folklore, of which the Dragon King is the leader. Also known as the Dragon God, the Dragon King is a prominent figure in Chinese art and religion. He is adopted by both Taoism and Buddhism and is the ruler of all water. Known as Long Wang in China, he has both human and dragon forms and can switch between dragon and human forms. Despite his intimidating and ferocious nature, Long Wan is regarded as a benevolent deity who brings good luck and chi energy to people living near the sea.

The Dragon King is a Chinese water and weather god. He is regarded as the dispenser of rain, commanding over all bodies of water. He is the collective personification of the ancient concept of the lóng in Chinese culture.

In East Asian cultures, dragons are most often shown as large, colorful snakelike creatures. While the dragons sometimes have qualities of a turtle or fish, they are most likely seen as enormous serpents.

While some named dragons are associated with specific colors, the dragon king can be shown in any shade. Like other Chinese dragons, he has a “horse-like” head, sharp horns and claws, and a hair-like beard.

Like many weather gods around the world, Long Wang was known for his fierce temper. It was said that he was so ferocious and uncontrollable that only the Jade Emperor, the supreme deity in Chinese Taoism, could command him. His human form reflects this ferocity. He is shown as a noble warrior in elaborate bright red robes. He usually has a fierce expression and poses with a sword.

During the Tang dynasty, the Dragon King was also associated with the worship of landowners and was seen as a guardian deity to protect homes and subdue tombs. Buddhist rain-making rituals were learnt in Tang dynasty China. The concept was introduced to Japan with esoteric Buddhism and was also practised as a ritual of the Yin-Yang path (Onmyōdō) in the Heian period.

伝説のヒューマノイドたち

ヒト型爬虫類 (3)

龍王 〜 中国神話の水と龍の神

中国の民間伝承には多くのドラゴンが登場するが、龍王はそのリーダーである。龍神としても知られる龍王は、中国の芸術と宗教において著名な人物である。道教と仏教の双方に採用され、すべての水の支配者である。中国ではロンワンと呼ばれ、人間の姿と龍の姿の両方を持っており、ドラゴンと人間の姿を行き来することができる。その威圧的で獰猛な性格にもかかわらず、ロン・ワンは海の近くに住む人々に幸運と気のエネルギーをもたらす慈悲深い神とみなされている。

龍王は中国の水と天候の神である。彼は雨を降らせる神とされ、あらゆる水域を支配する。彼は中国文化における古代の「龍 (ロン)」の概念の集合的な擬人化である。

東アジアの文化では、龍は大きくてカラフルな蛇のような生き物として描かれることが多い。龍は亀や魚の性質を持つこともあるが、巨大な蛇として見られることが多い。

特定の色を連想させる龍もいるが、龍王はどのような色合いでも描かれる。他の中国の龍と同様、「馬のような」頭部を持ち、鋭い角と爪を持ち、髪の毛のようなひげを生やしている。彼の人間の姿はこの獰猛さを反映している。彼は精巧な真っ赤なローブを着た高貴な戦士として描かれている。通常、獰猛な表情を浮かべ、剣を持ってポーズをとる。

世界中の多くの気象の神々と同様、龍王は激しい気性で知られていた。あまりに獰猛で制御不能だったため、玉皇大帝にしか彼を指揮できなかったと言われている。

唐の時代、龍王はまた、大地主の崇拝と結びついて、家を守り、墓を鎮める守護神と見なされていた。仏教の雨乞いの儀式は、唐代の中国に学んだ。この概念は密教とともに日本に伝わり、平安時代には陰陽道の儀式としても行われていた。

#humanoids#legendary creatures#hybrids#hybrid beasts#cryptids#therianthropy#legend#mythology#folklore#s.f.#nature#art#dragon king#dragon god#chinese mythology#chinese dragon

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

在約會了幾次後

每天聊天保持著曖昧及濃濃的性暗示

跟男人終於找到我們都有的空檔去約會

把我帶到旅館,很細心溫柔地邀我一起泡澡

浴池中把我摟在懷裡

親吻著我的脖子,整個人讓他壯碩的身體環抱著

真的好有性慾...

已經發情到是我主動忍不住說想要去床上了

而且因為他很壯,幫我沖洗完後直接被他抱去床上

好喜歡這樣強壯陽剛的男人

身體想要到不行....

他很溫柔把我全身都親遍

當然也包括我的小穴穴

因為我已經濕到流出來,很害羞

他知道我很興奮了卻不會急著插入

小穴穴被舔到受不了

讓我不停對他說 "插我插我..想要棒棒"

他再把我摟住我們第一次開始舌吻

我忍不住,手伸向他的肉棒愛撫

他的龜頭也濕到不行

流出來的水磨擦著我的大腿

我們身體交纏一起扭動著

嘴裡的舌頭也交纏著

他戴好套套後直直挺入

我感覺到我的穴口被撐開

等肉棒深入到中段後陰道一陣酥麻

男人邊抽插著我,我一邊撫摸他健壯的身體

我們換了好幾個姿勢不停抽插

他可以整個人把我摟抱住快速猛力幹我的淫穴

後入把我插到高潮 我得要他先暫停不然整個小穴都在收縮有點無力

男人後來越插越快速

緊緊摟著我在我耳邊喘息

我張開腿勾著他的腰部

我要他射精時抽出來把套套拔掉

他猛烈噴射出好多好多的精液

從我的腹部一路噴到脖子臉頰

我全身都佈滿的男人熱熱的精液

感到很滿足

處在淫蕩的發情狀態讓我主動幫他把射精後的肉棒舔乾淨

他的龜頭上還滴著精液

他怕我會不喜歡還想用手先把殘留的精液抹掉

我說沒關係 我想舔

於是讓他把滴著精液的肉棒往我嘴裡餵

我用舌頭好好地把男人的龜頭整個含入舔得很乾淨

還整根含入嘴中吸允

這根把我插到高潮的色肉棒...

然後我們又抱著一起舌吻

趴在他壯壯厚實的胸膛上好喜歡

雖然因為時間的關係我們只有做一次

但他說如果有找到時間還要再餵飽我

對了

他是有女友的男人呢

好喜歡這樣讓別的女人的男友幹我

很刺激又有成就感

然後他說

回去後他女友有跟他要

但是他就草草了事

說跟我做感覺比較爽

我故意跟他說

那趕快再找機會還想要被他幹

每次回想這些約會都會讓我小穴點濕...

75 notes

·

View notes