#toasted pine nuts

Photo

Kebbet Laktin

A Levantine treat: spinach and onion stuffed into a crust made from a fragrant pumpkin-bulgur dough.

From Nistisima: The Secret to Delicious Vegan Cooking from the Mediterranean and Beyond by Georgina Hayden

Serves 6–8

1kg pumpkin or butternut squash, peeled, deseeded, and chopped into 3cm chunks, or 400g pumpkin puree

1 onion

250g fine bulgur wheat

½ tsp ground cinnamon

¼ tsp ground allspice

Sea salt and black pepper

3 tbsp plain flour

100ml olive oil

5 red onions, peeled and finely sliced

2 garlic cloves, peeled and finely sliced

200g baby leaf spinach

1 tsp cumin seeds

½ tsp pul biber or dried chilli flakes

3 tbsp pomegranate molasses

2 tbsp toasted pine nuts

If you are using fresh pumpkin, put the chunks in a large pan, cover with water, and bring to a boil. Turn down to a simmer, cook for 20-30 minutes, until tender, then drain into a colander and leave to steam dry for 30 minutes, so that all the excess liquid evaporates. Meanwhile, peel and finely chop the onion and set aside.

Once the pumpkin is cooled and dry, you should have about 400g. Transfer to a large bowl and blitz to a puree with a stick blender. Stir in the chopped onion, bulgur, cinnamon, allspice, salt, and pepper, then set aside for 30 minutes, so the bulgur can absorb the moisture from the pumpkin. Stir in the flour until combined, then use your hands to knead the mixture to a smooth dough. If it’s looking a bit dry and crumbly, very gradually add enough water to bring it together – depending on the pumpkin, you might need up to six tablespoons.

Heat the oven to 220C (fan 200C)/425F/gas 7. Brush a deep, loose-bottomed 24cm fluted pie tin with a little oil (I find larger flutes work better with this recipe). Press the pumpkin-bulgur dough evenly into the base and up the sides of the tin, then drizzle generously with olive oil, gently brushing it around so it covers the whole surface of the dough. Bake for about 35 minutes, until the crust is golden all over and the tops of the sides are slightly browned.

Meanwhile, make the filling. Rinse the spinach well, then set aside. Put a wide pan on a medium-low heat, add three tablespoons of oil, then stir in the onions and garlic, cover the pan, and leave to cook for 10 minutes, until they start to soften. Stir in the cumin seeds, pul biber, and a teaspoon each of salt and black pepper, then fry, uncovered, and stir occasionally for a further 15 minutes, until sticky and sweet.

Stir in the pomegranate molasses and cook for a further 5 minutes – the onions should by now be gloriously pink. Add the spinach, turn up the heat a little, and cook for 8 to 10 minutes, until all the leaves have wilted and there is hardly any moisture left in the pan.

Spoon the filling into the tart pan, then remove it from the tin and slide on to a serving board. Sprinkle over the pine nuts and leave to stand for 5 minutes before serving.

#savory tart#butternut squash#pumpkin#pumpkin puree#bulgur wheat#ground allspice#red onion#baby spinach#cumin seeds#pul biber#pomegranate molasses#toasted pine nuts#middle eastern food#chili flakes#vegan

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Crepes Recipes

These Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts are a delicious dessert for any occasion. The crepes are light and fluffy, with a rich and nutty flavor from the vanilla ice cream and toasted pine nuts.

0 notes

Text

Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts

These Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts are a delicious dessert for any occasion. The crepes are light and fluffy, with a rich and nutty flavor from the vanilla ice cream and toasted pine nuts.

0 notes

Text

Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts Recipe

Toasted Pine Nuts, Sugar, Eggs, Butter, Vanilla Ice Cream, Milk, Salt, All-Purpose Flour. These Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts are a delicious dessert for any occasion. The crepes are light and fluffy, with a rich and nutty flavor from the vanilla ice cream and toasted pine nuts.

0 notes

Text

Recipe for Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts

Made with Toasted Pine Nuts, Sugar, Eggs, Butter, Vanilla Ice Cream, Milk, Salt, All-Purpose Flour. These Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts are a delicious dessert for any occasion. The crepes are light and fluffy, with a rich and nutty flavor from the vanilla ice cream and toasted pine nuts.

0 notes

Text

Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts Recipe

These Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts are a delicious dessert for any occasion. The crepes are light and fluffy, with a rich and nutty flavor from the vanilla ice cream and toasted pine nuts.

0 notes

Text

Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts Recipe

These Ice Cream Crepes with Pine Nuts are a delicious dessert for any occasion. The crepes are light and fluffy, with a rich and nutty flavor from the vanilla ice cream and toasted pine nuts.

0 notes

Text

Pumpkin Crostini with Arugula Pesto (Vegan)

#vegan#brunch#appetizer#snacks#crostini#toast#pumpkin#squash#butternut squash#hummus#pesto#arugula#garlic#walnuts#lemon#nutritional yeast#pomegranate#pine nuts#chili#olive oil#black pepper#sea salt#eat the rainbow

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vegan Peacamole Toast With Radish Salsa

#breakfast#savoury#food#recipe#recipes#vegan#veganism#vegetarian#peacamole#peas#radish#radishes#pine nuts#sourdough#toast#bread#veganfood#vegan food#nutrition#diet#weightloss#weight loss#healthy#healthy food#healthy eating#nutrients#foodie#dieting#fitspo#fitspiration

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

dinner 2nite was crazy insanely good but i took a picture and it looks like dog food :(

#pasta w sundried tomato paste green lentils black & green olives and vegan cheese melted in. 1 of the best things ive ever made it was sooo#extremely tasty#oo and it had toasted pine nuts too i almost forgot

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

going to have a nice night talking about how the food's great, the game i've been playing is terrible, and how nice it'll be to get back to running, and that sort of thing.

#sadpoastin' interrupted to think about vegetables#i did fry the spring onions for lunch#and ate them with a pine nut-gigante puree on toast

1 note

·

View note

Text

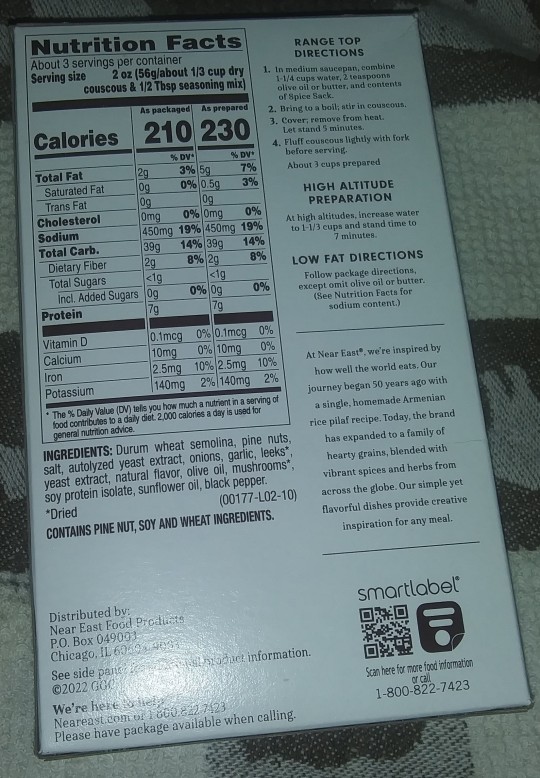

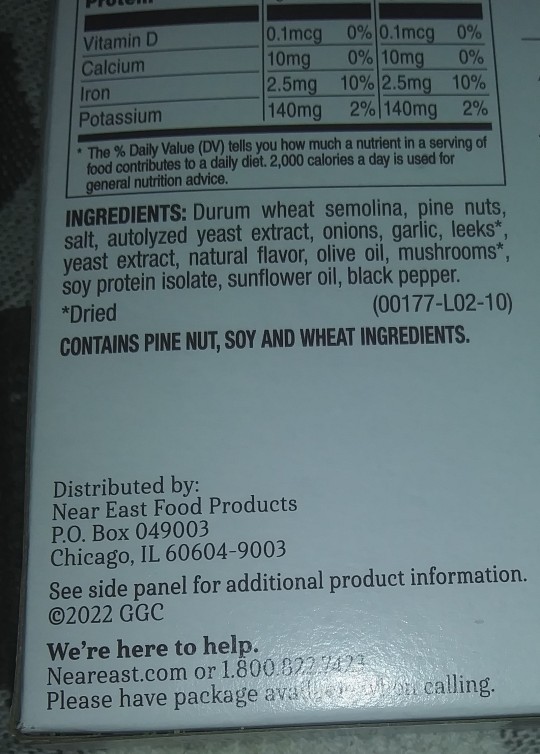

#NearEast #NearEastToastedPineNutCouscous #CouscousReview

I tried the Near East Toasted Pine Nut Couscous and it was pretty good. This was cooked in water and was lightly salty. This was soft and the pine nuts gave it a little crunchy texture to it.

I would eat this again.

Got at Meijer.

0 notes

Photo

Creamy Broccoli With Mustard Soup - Soup

#Toasted pine nuts are the perfect garnish for this traditional broccoli cream soup. salad#dinner#broccoli cream soup#mustard soup#bread#garnish#heat

0 notes

Text

This mortar and pestle has made me a worse person

0 notes

Text

When my life journey took me to Italy, even the mere glimpse of an Israeli flag flying over a food stall in the city of Varese would provoke me. “This is our food!” I told my colleague. “Israelis can sell mujaddara, hummus, maqlubeh and falafel, but they cannot declare them their property!” As if stealing the land, water, and air were not enough?! This food is part of our identity and culture. For me as a Palestinian, each plate has a story that relates to my people, the state, and the fragrances of my homeland.

Israel uses food to claim ownership of the territory and encourage tourism, not only internally but also abroad, featuring it in advertisements and in articles published in international newspapers and world-famous magazines. Israeli chefs present huge events in which they appropriate Palestinian cuisine and our cultural foods, denying the origins of these foods and pretending that they are theirs. As Israelis proclaim ownership of plates whose origins lie in the Middle East, the Levant, or even Egypt, they deny the existence of the people who live on this land and whose dishes and recipes are much older than the state of Israel.

Someone as tenacious as I cannot let this go by unchallenged. Instead, I have decided to use food as a soft power tool to fight the occupation. Food has become my means to speak about Palestine.

Historically, cuisine has been a mirror of civilization, culture, heritage, and the economic status of a people. Likewise, Palestinian dishes reflect all these aspects and elements. Take musakhan, for example, a Palestinian farmer’s dish that traditionally has been cooked during the olive harvest season: tabun bread is drenched in olive oil, covered with onions that have been caramelized in olive oil, and topped with sumac. All these ingredients are the fruit of Palestinian land. As living standards rose, chicken was added, then toasted almonds and pine nuts were sprinkled on top. But despite these changes, the dish has kept its original flavors as its essence has been passed down from generation to generation, preserving the authenticity of the dish.

Our occupiers can take possession of our food in the material sense, as they have done and continue to do with our land. But they cannot transmit its history, traditions, and associated sentiments because we Palestinians consider our food to be a thread that brings us together and connects us to our homeland – especially those of us who live in the diaspora.

It is no coincidence that many Palestinian poets and writers talk about food when they express their longing for their homeland. The famous Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, for example, wrote while in exile, “Dearly I yearn for my mother’s bread, my mother’s coffee.”

Food is part of Palestinian identity wherever we go. It reflects our culture, heritage, and personality.

– Fidaa Abuhamdiya, "The Soft Power of Palestinian Food." This Week in Palestine Issue 286, February 2022. Palestinian Cuisine: From Tradition to Modernity. p. 57.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: Two large flatbreads. The one in the center is topped with bright purple onions, faux chicken, fried nuts, and coarse red sumac; the one at the side is topped with onions and sumac. Second image is a close-up. End ID]

مسخن / Musakhkhan (Palestinian flatbread with onions and sumac)

Musakhkhan (مُسَخَّن; also "musakhan" or "moussakhan") is a dish historically made by Palestinian farmers during the olive harvest season of October and November: naturally leavened flatbread is cooked in clay ovens, dipped in plenty of freshly pressed olive oil, and then covered with oily, richly caramelized onions fragrant with sumac. Modern versions of the dish add spiced, boiled and baked chicken along with toasted or fried pine nuts and almonds. It is eaten with the hands, and sometimes served alongside a soup made from the stock produced by boiling the chicken. The name of the dish literally means "heated," from سَخَّنَ "sakhkhana" "to heat" + the participle prefix مُـ "mu".

I have provided instructions for including 'chicken,' but I don't think the dish suffers from its lack: the rich, slightly sour fermented wheat bread, the deep sweetness of the caramelised onions, and the true, clean, bright expressions of olive oil and sumac make this dish a must-try even in its original, plainer form.

Musakhkhan is often considered to be the national dish of Palestine. Like foods such as za'tar, hummus, tahina, and frika, it is significant for its historical and emotional associations, and for the way it links people, place, identity, and memory; it is also understood to be symbolic of a deeply rooted connection to the land, and thus of liberation struggle. The dish is liberally covered with the fruit of Palestinian lands in the form of onions, olive oil, and sumac (the dried and ground berries of a wild-growing bush).

The symbolic resonance of olive oil may be imputed to its history in the area. In historical Palestine (before the British Mandate period), agriculture and income from agricultural exports made up the bulk of the economy. Under مُشَاعْ (mushā', "common"; also transliterated "musha'a") systems of land tenure, communally owned plots of land were divided into parcels which were rotated between members of large kinship groups (rather than one parcel belonging to a private owner and their descendants into perpetuity). Olive trees were grown over much of the land, including on terraced hills, and their oil was used for culinary purposes and to make soap; excess was exported. In the early 1920s, Palestinian farmers produced 5,000 tons of olive oil a year, making an average of 342,000 PL (Palestinian pounds, equivalent to pounds sterling) from exports to Egypt alone.

During the British Mandate period (from 1917 to 1948, when Britain was given the administration of Palestine by the League of Nations after World War 1), acres of densely populated and cultivated land were expropriated from Palestinians through legal strongarming of and direct violence against, including killing of, فَلّاَحين (fallahin, peasants; singular "فَلَّاح" "fallah") by British troops. This continued a campaign of dispossession that had begun in the late 19th century.

By 1941, an estimated 119,000 peasants had been dispossessed of land (30% of all Palestinian families involved in agriculture); many of them had moved to other areas, while those who stayed were largely destitute. The agriculturally rich Nablus area (north of Jerusalem), for example, was largely empty by 1934: Haaretz reported that it was "no longer the town of gold [i.e., oranges], neither is it the town of trade [i.e., olive oil]. Nablus rather has become the town of empty houses, of darkness and of misery". Farmers led rebellions against this expropriation in 1929, 1933, and 1936-9, which were brutually repressed by the British military.

Despite the number of farmers who had been displaced from their land by European Jewish private owners and cooperatives (which owned 24.5% of all cultivated land in Palestine by 1941), the amount of olives produced by Palestinians increased from 34,000 tons in 1931 to 78,300 in 1945, evidencing an investment in and expansion of agriculture by indigenous inhabitants. Thus it does not seem likely that vast swathes of land were "waste land," or that the musha' system did not allow for "development"!

Imprecations against the musha' system were nevertheless used as justification to force Palestinians from their land. After various Zionist organizations and militant groups succeeded in pushing Britain out of Palestine in 1948—clearing the way for hundreds of thousands of Palestinians to be dispossessed or killed during the Nakba—the Israeli parliament began constructing a framework to render their expropriation of land legal; the Cultivation of Waste Lands Law of 1949, for example, allowed the requisition of uncultivated land, while the Absentees’ Property Law of 1950 allowed the state to requisition the land of people it had forced from their homes.

Israel profited from its dispossession of millions of dunums of land; 40,000 dunums of vineyards, 100,000 dunums of citrus groves, and 95% of the olive groves in the new state were stolen from Palestinians during this period, and the agricultural subsidies bolstered by these properties were used to lure new settlers in with promises of large incomes.

It also profited from the resulting "de-development" of the Palestinian economy, of which the decline in trade of olive oil furnishes a striking example. Palestinian olive farmers were unable to compete with the cheaper oils (olive and other types) with which Zionist, capital-driven industry flooded the market; by 1936, the 342,000 PL in olive oil exports of the early 1920s had fallen to 52,091 PL, and thereafter to nothing. While selling to a Palestinian captive market, Israel was also exporting the fruits of confiscated Palestinian land to Europe and elsewhere; in 1949, olives produced on stolen land were Israel's third-largest export. As of 2014, 12.9% of the olives exported to Europe were grown in the occupied West Bank alone.

This process of de-development and profiteering accelerated after Israel's military seizure of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967. In 1970, agriculture made up 34% of the GDP of the West Bank, and 31% of that of Gaza; in 2000, it was 16% and 18%, respectively. Many of those out of work due to expropriated or newly unworkable land were hired as day laborers on Israeli farms.

Meanwhile, Palestinians (and Israeli Palestinians) continued to plant and cultivate olives. The fact that Palestinians do not control their own water supplies or borders and may expect at any time to be barred by the military from harvesting their fields has discouraged investment and led to risk aversion (especially since the outmoding of the musha' system, which had minimized individual risk). In this environment, olive trees are attractive because they are low-input. They can subsist on rainwater (Israel monopolizes and poisons much of the region's water, and heavily taxes imports of materials that could be used to build irrigation systems), and don't require high-quality soil or daily weeding. Olive trees, unlike factories and agricultural technology, don't need large inputs of capital that stand to be wasted if the Israeli military destroys them.

Olive trees are therefore the chosen crop when proving a continued use of land in order to prevent the Israeli military from expropriating it under various "waste" or "absentee" land laws. Palestinians immediately plant olive seedlings on land they have been temporarily forced from, since even land that has lain fallow due to status as a military closed zone can be appropriated with this justification. The danger is so pressing that Palestinian agronomists encouraged this habit (as of 1993), despite the fact that Israeli competition and continual planting had lowered olive crop prices, and despite the decline in soil quality that results from never allowing land to lie fallow. In more recent years, olive trees have yielded primary or supplementary income for about 100,000 Palestinian families, producing up to 191 million USD in value in good years (including an average of 17,000 tons of olive oil yearly between 2001 and 2009).

Israeli soldiers and settlers have famously uprooted, vandalized, razed, and burned millions of these olive trees, as well as using military outposts to deny Palestinian farmers access to their olive crops. It prefers to restrict Palestinians to annual crops, such as vegetables and grains, and eliminate competition in permanent crops, such as fruit trees.

This targeting of olive trees increases during times of intensified conflict. During the currently ongoing olive harvest season (November 2023), Gazan olive farmers have reported being targeted by Israeli war planes; some farmers in the West Bank have given up on harvesting their trees altogether, due to threats issued by organized networks of settlers that they would kill anyone seen making the attempt.

The rootedness of olive trees in the history of Palestine gives them weight as a symbol of homeland, culture, and the fight for liberation. Palestinian olive harvest festivals, typically celebrated in October with singing, dancing, and eating, have inspired similar events elsewhere in the world, aimed at sharing Palestinian food and culture and expressing solidarity with those living under occupation.

Support Palestinian resistance by calling Elbit System’s (Israel’s primary weapons manufacturer) landlord, donating to Palestine Action’s bail fund, and donating to the Bay Area Anti-Repression Committee bail fund.

Ingredients:

For the dish:

2 pieces taboon bread, preferably freshly baked

2 large or 3 medium yellow onions (480g)

1 cup first cold press extra virgin olive oil (زيت زيتون البكر الممتاز)

1 Tbsp coarsely ground Levantine sumac (سماق شامي / sumaq shami), plus more to top

Ground black pepper

For the chicken (optional):

500g chicken substitute

5 green cardamom pods, or 1/4 tsp ground cardamom

4 cloves, or pinch ground cloves

1 Mediterranean bay leaf

1 Tbsp ground sumac

For the nut topping (optional):

2 Tbsp slivered almonds

2 Tbsp pine nuts

Neutral oil, for frying

Notes on ingredients:

Use the best olive oil that you can. You will want oil that has some opacity to it or some deposits in it. I used Aleppo brand olive oil (7 USD a liter at my local halal grocery).

If you want to replace the taboon bread with something less laborious, I would recommend something that mimics the rich, fermented flavor of the traditional, whole-wheat, naturally leavened bread. Many people today make taboon bread with white flour and commercial yeast—which you might mimic by using storebought naan or lavash, for example—but I think the slight sourness of the flatbread is a beautiful counterpoint to the brightness of the sumac and the sweetness of the caramelized onions. I would go with a sourdough pizza crust or something similar.

Your sumac should be coarsely ground, not finely powdered; and a deep, rich red, not pinkish in color (like the pile on the right, not the one on the left).

For this dish, a whole chicken is usually first boiled (perhaps with spices including bay leaves, cardamom, and cloves) and then baked, sometimes along with some of the oil from frying the onions. I call for just frying or baking instead; in my opinion, boiling often has a negative effect on the texture of meat substitutes.

Instructions:

For the onions:

1. Heat a cup of olive oil in a large skillet or pot. Fry onions on medium-low, stirring often, for 10 minutes or until translucent.

2. Add 1 Tbsp sumac and a few cracks of black pepper and reduce to low. Cook for another 30 minutes, stirring occasionally, until onions are sweet, reduced in volume, and pinkish in color.

For the chicken:

1. Briefly toast and finely grind spices except for sumac (cardamom, cloves, and bay leaf). Filter with a fine mesh sieve. Dip 'chicken' into the pot in which you fried the onions to coat it with olive oil, then rub spices (including sumac) onto the surface.

2. Sear chicken in a dry skillet until browned on all sides; or bake, uncovered, in the top third of an oven heated to 400 °F (200 °C) until browned.

For the nut topping:

1. Heat a neutral oil on medium in a small pot or skillet. Add almonds and fry for 2 minutes, until just starting to take on color. Add pine nuts and fry until both almonds and pine nuts are golden brown. Remove with a slotted spoon.

To assemble:

1. Dip each flatbread in the olive oil used to fry the onions, then spread onions over the surface.

Some cooks dip the bread entirely into oil; others press it lightly into the surface of the oil in the pot on both sides, or one side; a more modern method calls for mixing the olive oil with chicken broth to lighten it. Consult your taste. I think the bread from my taboon recipe stands up well to being pressed into the oil on both sides without tearing or becoming soggy.

2. Top flatbread with chicken and several large pinches more sumac. Bake briefly in the oven (still heated to 400 °F / 200 °C), or broil on low, for 3-5 minutes, until the sumac and the surface of the bread have darkened a shade.

3. Top with fried nuts.

Musakhkhan is usually eaten by ripping the chicken into bite-sized pieces, tearing off a bit of bread, and eating the chicken using the bread.

Some cooks make a layered musakhkhan, adding two to three pieces of bread covered with onions on top of each other before topping the entire construction with chicken and pine nuts.

670 notes

·

View notes