#subterranean plant

Text

Sitting with Takofuusen

3/20/23

#yno#ynoproject#yume 2kki#ynfg#qxy#marijuana goddess world#snowy forest#techno condominium#nocturnal grove#lost creek#cloaked pillar world#viridescent temple#floating catacombs#fossil lake#subterranean plant#aurora lake#lavender waters#swt

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toby Tatum, {2011} The Subterraneans

#film#gif#toby tatum#the subterraneans#2011#short film#no people#plants#green#wind#uk#2010s#colour#male filmmakers

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NAME: Miner’s Ruin

RARITY: ★★☆☆☆

THREAT LEVEL: ★★★★☆ | It’s not unusual to see skeletons scattered underneath this plant’s elaborate underground root network. They often kill what they ensnare, though escape is possible.

HABITAT: Seems to grow anywhere that mining has occurred, or where there’s been other activity that hollowed out huge swaths of the earth.

DESCRIPTION: On the surface, the miner’s ruin looks to be an unassuming bramble, perhaps in the rose family. While there are no beautiful flowers to be found, it’s covered in the thorns you might expect and looks like a tangled mass. However, when someone approaches the miner’s ruin, the tangles unfurl, becoming vine-like appendages flailing through the air. It does this until its thorns catch hold of something. And then it’s time to feed.

Miner’s ruins grow on especially thin layers of soft soil that overhang hollow underground caverns, and they use their strong “vines” to pull food through the earth, dropping it into the tunnel or cave below with the bramble staying attached to the meal. The person or animal will find themselves at the mercy of the miner’s ruin’s enormous root system, which may have a radius of a mile, and is attached to many of these “brambles”, as each can only be used once due to the collapsing earth. While the roots aren’t as mobile as the brambles, being thin and filamentous, they’re the most dangerous part of the plant, siphoning away life force the longer they’re in physical contact with their prey. The plant earned its name from miners, of course, who frequently encountered the roots while working, not even being aware of the sinister brambles above.

ABILITIES: The aboveground vines of the miner’s ruin are its greatest weapon, and it poses minimal threat if it can’t gain purchase on its prey, or if it loses its thorny grip. The thorns on miner’s ruins are serrated and hooked, meaning it’s very painful to remove them once they’re lodged in the skin or clothes. They rely on this to keep prey attached to them after pulling it underground, since the roots themselves are rather weak. The plant’s elaborate root system seems to allow it to sense pressure around each bramble, such as footsteps, that signal the bramble to start moving. The roots themselves can also move, inching closer to the ensnared food underground because it senses the vibrations of struggling, but they’re sluggish.

WEAKNESS: The roots of miner’s ruins can be slashed with ease with any sharp blade, which is what miners tend to do when they see them stretched across the path. The brambles, however, are tough to cut. Because the plant relies on vibrations and movement to determine where the roots should move, it’s possible to prevent the plant from feeding if staying perfectly still, though this is hard when panicked and in pain. The thorns will still be attached, though, so this only prolongs the process and allows time for a rescue. The best chance of survival is either painfully freeing oneself from the thorns or having a sharp weapon handy for the roots that can still be used depending on bramble placement.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

As relentless rains pounded LA, the city’s “sponge” infrastructure helped gather 8.6 billion gallons of water—enough to sustain over 100,000 households for a year.

Earlier this month, the future fell on Los Angeles. A long band of moisture in the sky, known as an atmospheric river, dumped 9 inches of rain on the city over three days—over half of what the city typically gets in a year. It’s the kind of extreme rainfall that’ll get ever more extreme as the planet warms.

The city’s water managers, though, were ready and waiting. Like other urban areas around the world, in recent years LA has been transforming into a “sponge city,” replacing impermeable surfaces, like concrete, with permeable ones, like dirt and plants. It has also built out “spreading grounds,” where water accumulates and soaks into the earth.

With traditional dams and all that newfangled spongy infrastructure, between February 4 and 7 the metropolis captured 8.6 billion gallons of stormwater, enough to provide water to 106,000 households for a year. For the rainy season in total, LA has accumulated 14.7 billion gallons.

Long reliant on snowmelt and river water piped in from afar, LA is on a quest to produce as much water as it can locally. “There's going to be a lot more rain and a lot less snow, which is going to alter the way we capture snowmelt and the aqueduct water,” says Art Castro, manager of watershed management at the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. “Dams and spreading grounds are the workhorses of local stormwater capture for either flood protection or water supply.”

Centuries of urban-planning dogma dictates using gutters, sewers, and other infrastructure to funnel rainwater out of a metropolis as quickly as possible to prevent flooding. Given the increasingly catastrophic urban flooding seen around the world, though, that clearly isn’t working anymore, so now planners are finding clever ways to capture stormwater, treating it as an asset instead of a liability. “The problem of urban hydrology is caused by a thousand small cuts,” says Michael Kiparsky, director of the Wheeler Water Institute at UC Berkeley. “No one driveway or roof in and of itself causes massive alteration of the hydrologic cycle. But combine millions of them in one area and it does. Maybe we can solve that problem with a thousand Band-Aids.”

Or in this case, sponges. The trick to making a city more absorbent is to add more gardens and other green spaces that allow water to percolate into underlying aquifers—porous subterranean materials that can hold water—which a city can then draw from in times of need. Engineers are also greening up medians and roadside areas to soak up the water that’d normally rush off streets, into sewers, and eventually out to sea...

To exploit all that free water falling from the sky, the LADWP has carved out big patches of brown in the concrete jungle. Stormwater is piped into these spreading grounds and accumulates in dirt basins. That allows it to slowly soak into the underlying aquifer, which acts as a sort of natural underground tank that can hold 28 billion gallons of water.

During a storm, the city is also gathering water in dams, some of which it diverts into the spreading grounds. “After the storm comes by, and it's a bright sunny day, you’ll still see water being released into a channel and diverted into the spreading grounds,” says Castro. That way, water moves from a reservoir where it’s exposed to sunlight and evaporation, into an aquifer where it’s banked safely underground.

On a smaller scale, LADWP has been experimenting with turning parks into mini spreading grounds, diverting stormwater there to soak into subterranean cisterns or chambers. It’s also deploying green spaces along roadways, which have the additional benefit of mitigating flooding in a neighborhood: The less concrete and the more dirt and plants, the more the built environment can soak up stormwater like the actual environment naturally does.

As an added benefit, deploying more of these green spaces, along with urban gardens, improves the mental health of residents. Plants here also “sweat,” cooling the area and beating back the urban heat island effect—the tendency for concrete to absorb solar energy and slowly release it at night. By reducing summer temperatures, you improve the physical health of residents. “The more trees, the more shade, the less heat island effect,” says Castro. “Sometimes when it’s 90 degrees in the middle of summer, it could get up to 110 underneath a bus stop.”

LA’s far from alone in going spongy. Pittsburgh is also deploying more rain gardens, and where they absolutely must have a hard surface—sidewalks, parking lots, etc.—they’re using special concrete bricks that allow water to seep through. And a growing number of municipalities are scrutinizing properties and charging owners fees if they have excessive impermeable surfaces like pavement, thus incentivizing the switch to permeable surfaces like plots of native plants or urban gardens for producing more food locally.

So the old way of stormwater management isn’t just increasingly dangerous and ineffective as the planet warms and storms get more intense—it stands in the way of a more beautiful, less sweltering, more sustainable urban landscape. LA, of all places, is showing the world there’s a better way.

-via Wired, February 19, 2024

#california#los angeles#water#rainfall#extreme weather#rain#atmospheric science#meteorology#infrastructure#green infrastructure#climate change#climate action#climate resilient#climate emergency#urban#urban landscape#flooding#flood warning#natural disasters#environmental news#climate news#good news#hope#solarpunk#hopepunk#ecopunk#sustainability#urban planning#city planning#urbanism

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

So growing up I heard these kinds of statements: "X number of species goes extinct every year" and "Most species that go extinct are undescribed/undiscovered"

And I could never really picture what that looked like. What species were going extinct? Where? Why? If they're undiscovered, how do we know about it? It's only recently that I've been able to understand.

This is an example:

Since European colonization, 99% of old growth forest in the eastern United States was cut down.

In Eastern Kentucky, the coal industry led to waste and rubble being dumped in valleys, literally burying countless mountain streams in gravel and toxic sludge.

Colonialism and exploitation moved faster than leaf-sketching and bug-collecting European naturalists did. It's very simple, and very sad. When the coal mines polluted the streams, many species of fish that only lived in one specific stream must have gone extinct. When Native Americans were forced off their lands, we can presume that rare plant species found in meadows, canebrakes and oaks savannas dependent on particular anthropogenic disturbances went extinct. When old-growth tracts were logged, God only knows how many lichens, mosses, ferns and plants went extinct because the trees they lived on were chopped.

We can extrapolate from the diversity in the fragments that remain, and the number of rare endemic species in especially isolated areas, and guess what probably existed in areas that were obliterated early on.

Keep in mind: All is not lost. New species are still being discovered.

The Bluegrass region of Kentucky was once called one of the most peculiar plant communities of the South—an eastern island of oak savanna with an understory of Arundinaria bamboo and legumes. Early European settlers reported that the ground was incredibly rich and covered with knee-high clover and dense thickets of "cane" (bamboo) that made navigation next to impossible.

Some people say the Bluegrass was always a forest and the savanna theory is wrong. Bullshit! I know this because of several reasons:

The earliest records don't mention any sycamores at all in the Bluegrass, whereas river cane (bamboo) was everywhere. Arundinaria bamboos are fire dependent species, whereas sycamore is HIGHLY intolerant of fire. From this we can infer that the area had a history of frequent burning.

Everyone in the Bluegrass knows about the Old Trees. In horse and cattle pastures in the Bluegrass region, you will sometimes see gigantic, twisted old oaks, with great spreading crowns. Nowadays you hardly see an oak that properly merits the term "gnarled," but the gnarl of the Old Trees is crazy. Just look up google images for Kentucky tourism and you'll see one of those huge trees in the background of several of the photos, I bet. Hardly anyone consciously thinks about it, but these are pre-colonization trees. And they are all obviously open-grown—their growth habit over the centuries has spread out, rather than grown straight up as in a forest.

Early colonizers' records report big walnut and cherry trees in the area. Most of the old houses in the area are made of walnut wood. Those are mid-successional species—you wouldn't find them dominating in an area that was heavily disturbed regularly and recently, they're trees, but you wouldn't find them in a forest that had been minimally disturbed forest for centuries either. The fact that they got huge suggests that a regular disturbance pattern of the Bluegrass region was abruptly interrupted and mostly ceased.

It was a pretty special place, a savanna environment with a mix of giant twisted oaks, rolling prairie hills and bamboo thickets, with deep sinkholes connecting the surface to subterranean cave ecosystems. In places the limestone bedrock reached the surface, creating limestone glades—unique desert-like habitats with many rare plants including Opuntia cactus.

It was also one of the first ecosystems west of the Appalachians to be destroyed by settlers.

BUT! Just a few years ago, we discovered Trifolium kentuckiense—Kentucky clover. A unique species of clover that has only been found in two spots in Central Kentucky.

This means the Bluegrass species that probably went extinct because their habitat was ignorantly logged, plowed and grazed before they were studied by European science may not be entirely gone.

We have been able to fund exhaustive inventories of potential holdouts for big flashy animals like the ivory-billed woodpecker, but so many people view the place they live as "boring" and thoroughly explored, when there could be surviving plants hanging out just about anywhere.

But...I don't think most people realize how much of the Holocene extinction has already happened. Most of the losses are plants and bugs that you never knew existed in the first place.

I feel like lots of people are anxiously waiting for the mass extinction to "start" hitting, but that's not quite right. European colonization of the globe WAS and *is* the mass extinction (combined with climate change which is very related). It's actively ongoing in the Global South. In eastern North America, the major wave of extinctions hit between 100 and 300 years ago.

I feel so much grief for all that was almost certainly lost forever, but I also recognize that I live in a unique period of time where the future can still be changed, and in particular, the heavily damaged ecosystems of the Southeast can be restored and used to absorb carbon from the atmosphere and provide resilience to the entire globe. And I strongly suspect at least a few mysterious new plants will start popping up once that happens...because a lot of plants stick around in the soil seed bank for a long, long time, and seeds can happen to be preserved by freak accident and then sprout later.

we (researchers, scientists, people who work in this field) will desperately need to consult tribal nations for this though because from my reading into it, we don't know what the fuck we're doing. The most basic things like controlled burns are still struggling to catch on and in some places just, spraying herbicides willy-nilly on invasive plants without understanding what makes them invasive.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists in Japan have rediscovered an extremely rare species of parasitic "fairy lantern" that was presumed to be extinct.

The mysterious plant, Thismia kobensis, belongs to a rarely seen, fungus-sapping genus. The plants grow underground without photosynthesis yet send translucent flowers to sprout like ghostly lanterns from the forest floor.

First documented in 1992 in Kobe, Japan, the plant was presumed extinct when its habitat was destroyed by the building of an industrial complex. Now, three decades later, on a forest trail about 19 miles (30 kilometers) from Kobe, scientists have found the waxy, fang-shaped petals of the rare plant once more. They described the discovery Feb. 27 in the journal Phytotaxa [...].

Fairy lanterns (Thismia) are ethereal, subterranean plants whose only brief eruptions from the earth come in the form of intricately petaled flowers. Without chlorophyll to photosynthesize energy, the plants instead use a process called mycoheterotrophy to steal the nutrients from the fungi that entwine themselves around their roots.

Thismia's preferred habitats, which tend to be tropical rainforests, are facing global decline. Little is known about the elusive plants, and a significant number of the roughly 90 identified species have been lost, some for decades, after their initial discoveries.

"Because most mycoheterotrophic plants obtain their carbon indirectly from photosynthetic plants via shared mycorrhizal [fungal and plant] networks, they are highly dependent on the activities of both the fungi and trees that sustain them," the researchers wrote in the study. "Consequently, they are particularly sensitive to environmental disturbances, often rendering them both rare and endangered."

---

Headline, image, caption, and text published by: Ben Turner. “Otherworldly ‘fairy lantern’ plant, presumed extinct, emerges from forest floor in Japan.” Live Science. 28 February 2023.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

November 2023 witch guide

Full moon: November 27th

New moon: November 13th

Sabbats: None

November Beaver Moon

Known as: Digging(or scratching) moon, Deer rutting moon, Frost moon, Whitefish moon, Mourning Moon, Dark moon, Blotmonath, Fog moon, Mad moon, Moon of storms, Herbistmanoth & Freezing moon

Element: Water

Zodiac: Scorpio & Sagittarius

Nature spirits: Subterranean faeries

Deities: Astarte, Bast, Black Isis, Hecate, Kali, Lakshmi, Mawu, Nicnevin, Osiris & Saraswati

Animals: Crocodile, jackal, scorpion & unicorn

Birds: Goose, owl & sparrow

Trees: Alder, cypress & hazel

Herbs: Betony, blessed thistle, borage, cinquefoil, fennel, grains of paradise & verbena

Flowers: Blooming cacti & chrysanthemum

Scents: Cedar, cherry blossom, hyacinth, lemon, narcissus & peppermint

Stones: Beryl, cat's eye, citrine, yellow sapphire, topaz & turquoise

Colors: Blues, grey, sea green & silver

Energy: Deity communication, cooperation, death, divination, focus, passion, healing, preparation, secrets, sex matters, taking root & transformations.

The Beaver Moon gets its name because it is the time of year when beavers begin to take shelter in their lodges, having laid up sufficient food stores for the long winter ahead. During the fur trade in North America, it was also the season to trap beavers for their thick, winter-ready pelts.

Other celebrations:

• Lunantishees

November 11th

Also known as: The day of the Sidhe

This day celebrates the Lunantishee Faeries & honors the sacred blackthorn tree that they protect. It is said these faeries dance around their host blackthorn tree or bush by the light of the full moon in which they worship. The Lunantishee are closely associated with moonstone as their name of Moon-Sidhe or moon faeries suggest. These faeries are intensely protective guardians who highlight to us the need to protect our homes & our personal energies/ourselves.

In some traditions people would leave offerings like cakes, milk, honey or ale to avert any mischievous behavior from the faeries & if you had a blackthorn tree leave blackthorn blessings upon you.

During this time it is advised to not pick, cut or prune these plants under any circumstances or else misfortune would be placed upon them.

•Night of Hecate

November 16th

Though many choose to honor the Goddess Hecate during this day, there doesn't seem to be any historical evidence suggesting this particular day has any traditional associations or events & likely was mistaken from Hekate's Deipnon which takes place during the dark phase of the moon. However modern practitioners use this day to honor Hekate despite this.

Some celebrate by having a feast filled with wine, mushrooms, bread & more while also leaving some at the threshold of their front door to symbolize the crossroads between indoors and outdoors.

Sources:

Farmersalmanac.com

Llewellyn's Complete Book of Correspondences by Sandra Kines

A Witch's Book of Correspondences by Viktorija Briggs

Llewellyn's 2023 magical almanac: practical magic for everyday living

Wikipedia

#correspondence#witch guide#november 2023#witchblr#wiccablr#paganblr#witch community#witch society#witchcraft#spellwork#hekate#Beaver Moon#traditional witchcraft#grimoire#book of shadows#spellbook#moon magic#witches of tumblr#tumblr witch#witch tumblr#witch tips#beginner witch#baby witch#wheel of the year#sabbat#pagan#wicca#witchcore#witch#GreenWitchcrafts

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preliminaries: Battle of the Black-on-Whites!

Black-on-white pottery is far and away the most common decorated pottery style of the ancient Southwest. There are way, way too many to include them all... in fact, there are too many to include even all the ones I want to show off!

So this is the Preliminary Round - four different black-on-white types will go up against each other... only two will move on to represent black-on-whites in the final bracket.

Vote for your favorite!

Information and details about each type under the cut:

Sosi and Dogoszhi Black-on-white

Dogoszhi Black-on-white jar. Northeastern Arizona, 1050-1200.

These are actually two different types within Tusayan White Ware - Sosi B/W and Dogoszhi B/W. However, like I said, Too Many Whitewares, so I'm grouping them together because there's strong overlap.

Sosi B/W can be identified by its bold, black designs, like the one in the compilation above the cut; Dogozshi B/W has similar design layout, but instead of solid black, they're filled with hatchure (thin, parallel lines. Sometimes, like the image above, the body is a Dogoszhi design, while the neck has a more Sosi-like design.

Sosi and Dogozshi Black-on-whites were built with the coil-and-scrape method (built up of many small coils, probably turned on a turning plate called a puki, and then while the clay was still wet, scraped smooth and sometimes polished). The paint was carbon-based and got its color from a plant called beeweed. These were made in the Kayenta and Tusayan regions of north-eastern Arizona.

Mimbres Black-on-white

Bowl with a Frog, Mimbres Black-on-white. Southwestern New Mexico, AD 1000-1150.

One of the most iconic Southwest pottery types. Literally: one of the few pottery types in the Southwest to display a wide range of icons, human and animal figures. Pre-Classic Mimbres bowls used geometric and rotational symmetry designs more often, mixing bold lines and hatchure; Classic Mimbres bowls tend to have a linear design around the rim, and then a human or animal design on the inside. Various types of figures are seen, but primarily birds, insects, amphibians/reptiles, and twin human figures, in hematite-based paint.

Mimbres bowls are among the most popular to be sold by looters on the black market. Worse, a very large number of the most dramatic Mimbres bowls come from burials; if you see an archaeological pot for sale with an animal design like this, it was almost certainly stolen out of a grave. You can especially suspect this when the bowls have small circular holes smashed or drilled in the center, usually obscuring the figure partially. Archaeologists call these kill holes, from the idea that the pot was "killed" to end its use-life when it was buried with the deceased person. If you see a Mimbres pot with a kill-hole, odds are very good (something like 80%) that it came from a burial. These displayed bowls here are verified to come from non-burial contexts.

Chaco Black-on-white

Chaco (or Gallup) Black-on-white. Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, north-western New Mexico, AD 1000-1100.

Chaco Canyon! One of the most dramatic, interesting, and still mysterious aspects of the Ancestral Southwest. In a canyon in New Mexico, multiple palatial "Great Houses" were built, with hundreds of rooms, large and regimented plazas, massive kivas (circular subterranean religious buildings), and an incredible amount of decoration and pageantry. Pueblo Bonito, the largest of the Chaco Great Houses, is proven to have had a matrilineal elite/noble lineage. How many people actually lived in the Great Houses? Were they palaces, communal centers, worship centers? Were the Chaco elite a priestly class or a noble caste or a bit of both? How did they mobilize people throughout the Chaco sphere of influence to bring timbers down from the mountains a hundred kilometers away to build these Great Houses? There are a lot of things archaeologists still argue about. Pueblo and Navajo oral histories describe Chaco as an overreach of power that their ancestors eventually rejected, leading to the collapse of Chaco Canyon as a center of social influence throughout the Southwest around 1100. (Modern Pueblo and Navajo relationships to Chaco are complicated. It was an overreach of power, but also an incredible ancestral polity.) Until then, it was certainly a socially, politically, and religiously powerful force.

You can also see this in the pottery: this style of hatchure, the narrow black-and-white lines, was massively popular in Chaco Canyon and seems to have kind of ripple-effected out to the rest of the Southwest who were in or near the Chaco sphere of influence. Hatchure is very common in a lot of black-on-white wares, but very close, very narrow, very even hatchure is strongly associated with Chaco Canyon.

Cylinder jars for chocolate-drinking, as described and confirmed by Dr. Patricia Crown. Chaco Canyon, Pueblo Bonito, 1000-1100.

Also, Chaco Black-on-white cylinder jars were used for a chocolate-drinking ritual, indicating cultural connections, religious ties, and trade routes to Mesoamerica and Maya communities far to the south in Mexico in the 900s-1000s. It's an important thing to remember: None of these cultures or time periods were static, and were almost never insular.

Mesa Verde Black-on-white

Mesa Verde Black-on-white bowls. Southwestern Colorado/northwestern New Mexico, AD 1150-1280.

An immensely popular white ware style, Mesa Verde Black-on-white is associated with the Ancestral Pueblo settlements - including the dramatic and famous cliff dwellings, like Cliff Palace. Bold, heavy, repeating geometric designs in carbon-based paint are the most common, but there are hatched designs and some areas that used mineral paints as well. Paintbrushes to apply these painted designs were made of yucca.

Some of the most fun and famous Mesa Verde B/W vessels are the mugs of Mug House, a site so named because a bunch of mugs were found in it.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

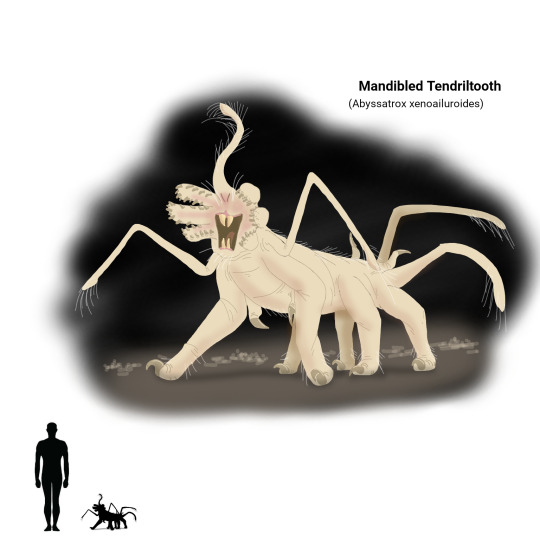

From a single founding species descended from the stellasnoots that found a suitable home in the secluded caverns of Arcuterra, the daggoths, a clade of subterranean molrocks of distant relation to the rattiles, have since diversified over the last 25 million years in isolation. As the cave systems naturally expanded over the course of many millennia, the ecosystem too grew bigger, as it created more room for a wider and more diverse range of species to thrive.

Over millions of years, the upper chambers of the cave system became more open to the surface, resulting to not only a slight but significant influx of oxygen into the ecosystem but also nutrients from the surface, such as organic detritus and the abundant droppings of transient species such as roosting ratbats that nest in the surface chambers, washed down into the caves by rain. These fuel the abundant growth of bacteria, mocklichens and meatmoss, the cavern ecosystem's producers in the absence of plants and sunlight. With an abundance of food, space and, relatively speaking, oxygen, the life of the caves have since grown more diverse and complex than ever before.

Many of the daggoths have remained unchanged from the first forms that were the earliest colonists of the caves. The gothtles, small, mouse-sized insectivores, continue to stick to the ancestral lifestyle, as small, slow-moving ambush hunters that relied on stealth to pounce on insects. Yet the ancestral niche now comes with one drastic difference: they are no longer the apex predators of their environment. Abundant and fast-breeding, the gothtles are now the lower rung of the food chain as larger predators have since evolved from other branches of their kin.

While slower basal gothtles now rely on camouflage by scent and touch to evade enemies, numerous lineages have since evolved speed and evasiveness in order to outpace their predators. One such group are the xenomures, such as the four-plumed xenomure (Xenomuris tetradactylopluma), with long, slender legs that allow them to scurry quickly across the fungal and meatmoss mats to escape their enemies and hide among the maze-like growths to lose their enemies' trail. Two pairs of modified digits act as antennae fore and aft, giving the xenomures a vivid perception of obstacles in their surroundings while moving quickly in the pitch black darkness. These timid omnivores, in many ways, have come to be the caves' ecological parallel to "typical" rodents like furbils and duskmice on the surface, with some even harvesting and storing fruiting pods of mocklichens in burrow larders to eat later, and thus helping the mocklichens proliferate to new areas.

Other lineages of the small gothtles have also evolved more active lifestyles as dynamics of the ecosystem have changed. Some, such as the long-bodied common skitter (Longicorpomys polypus) developed slender bodies and shorter limbs to specialize in hiding in small crevices in the rock walls, well-protected from predators, where they can feed on the fungal mycelia, the buried "roots" hidden underneath the organic soil-like detritus mats covering the cave floors. Others have become small hunters of their own right, paralleling the chrews and scabbers of the surface, like the earthumb arthoid (Dactylotomys auricheirus), equipped with two front digits bearing pointed claws positioned next to its head almost like ears, that it uses to root out small prey, such as insects, nematodes and wormlike maggoths out of their burrows and out from growths of mocklichens and meatmoss.

Virtually every surface of the cavern system has offered a habitat for life, including the walls and the ceiling of the caves, with the walls and roofs forming elevated "branches" and dangling "vines" of various vegetative plant-analogues, which are fed upon by "browsers" adapted to reach high up on to access fungal growths inaccessible to other ground-dwellers.

The ceilings, in particular, are abuzz with a surprising diversity of organisms dwelling amidst the overhanging stalactites. In particular, the dangling "vines", in reality complex filamentous fungal hyphae nourished by a symbiotic relationship with chemosynthetic bacteria, produce buds that exude an odorous scent, that draws in the feelerflits: flying insects descended from dipteran flies that, with long and very sensitive antennae equipped with tactile, thermal and olfactory receptors, have secondarily regained their power of flight and are able to navigate even without sight and home in on the buds that produce nutritious carbohydrate-rich liquids in return for it spreading its spores.

One descendant of the roof stalac has since adapted to exploit this relationship. The bulbous-snouted budwight (Nasofungiosus imitator) has developed specialized bud-like growths at the end of its nasal tendrils, that sport modified sebaceous glands that excrete a scent similar to those of the vine blooms, the chemicals of which it acquires and secretes by eating the blooms themselves. Then, lying in wait, anchored onto the surface of stalactites or perched amidst the vines, it waves its tendrils in the air in anticipation of an unwary feelerflit blundering into its trap, to be ensnared by seven long and flexible tendrils and passed into the mouth to be eaten.

Curiously, despite its purpose of mimicry, the budwight's tendrils in fact look nothing at all like the vine buds, being simple enlarged growths at the ends of the knobbly nasal appendages. In a world of darkness, appearances are almost entirely insignificant, as prey and predator alike perceive their surroundings with sound, smell and touch, as well as other more remarkable senses like thermo- and electroreception. As such, mimcry revolves around these senses: not even a vaguely-similar imitation to a sighted creature, but a deception at least sufficient to trap its equally-blind prey.

Of the various small daggoths that populate the caves, however, none are as divergent and unconventional as the maggoths: a lineage of neotenic descendants of the mossmulch, a more typical-looking daggoth whose life-cycle has taken unexpected turns to produce one of the greatest regressions in complexity second only to the shroomors.

Measuring only a centimeter or less, the maggoths, such as the basal lichen maggoth (Vermimys simplisticus) are extremely simplified creatures: their respiration takes place almost entirely through their permeable skin, their skeletons, save for their ossified mandible and maxilla, are completely made of only cartilage, and they move entirely through two sets of muscles, an inner layer of longtidunal muscles and an outer layer of concentric muscles that contract and relax alternatingly to undulate them forward. This body plan arose from the mossmulch's early gestation lasting only a few days and producing barely-developed young, basically just self-sufficient and free-living early-stage embryos, adapted to feed constantly on meatmoss and mocklichens by tunneling through them, and, with an abundance of a reliable food source, some species eventually became neotenic, no longer developing limbs and nasal tendrils and ossified skeletons, and simply reproducing in a larger version of their quasi-larval state.

The simplified anatomy and reduction of surplus organs has allowed maggoths to be quite successful in the vast expanses of the subterranean caverns. In particular, their very simple bodies has reduced their development to but a few days, allowing them to shorten their generations to as little as three or four weeks: at the age of twenty-one days, maggoths are already sexually mature and can mate, bearing litters of up to a dozen or more wormlike quasi-larval young at a time once every five or six days. These 3-4 millimeter-long newborns feed off skin secretions made by the females for the first few hours of their life before departing for good, in a last remaining hint of mammalian history in a species so far removed from a typical mammal's form.

Another, unlikely advantage of their simplified anatomy is that it requires far less oxygen, which coupled by their incredibly small body sizes and their respiration through their skin, has led one lineage into a new frontier: the waters of the subterranearn rivers as well as the underground sumps that form bodies of water such as ponds and lakes. Thus arose the hampreys: the first ever aquatic lineage of hamsters on HP-02017 to evolve fully-aquatic respiration and thus be entirely independent of breathing air at the surface. Specialized vessels directly branching from the heart absorb oxygen diffused through their permeable skin, and thus their lungs have been reduced to simple sacs regulating buoyancy. Perhaps more remarkable, however, is the marked reduction of their nervous system, especially the brain: their simple lifestyle and unusual respiration had no need for such an energy-hungry organ as a complex brain, and thus in the hampreys this otherwise very vital organ, once the pride of mammals in their complexity, now has completely atrophied to basically but a brain stem, capable of little more than basic bodily functions and responses to external stimuli, moving through the water in jerky, wiggling movements toward the taste and scent of food and away from the vibrations of danger.

Some hampreys, such as the rasping hamprey (Vermicthymys micronis), are independent creatures teeming in the underground ponds and lakes, scraping off mats of chemosynthetic bacterial colonies using their jaws: an ossified mandible and maxilla bearing two pairs of gnawing incisors--basically the only remaining visual vestige of their rodent ancestry. Some, however, have specialized these remnant teeth for another purpose: the sanguine hamprey (Atrocivermimys haemophilus) has developed elongated teeth and a "lip" that allows its mouth to function as a suction--enabling it to attach to other aquatic daggoths such as tubesnouts and trogadiles and parasitically feed off their bodily fluids.

Not all daggoths are small, however. In the recent eons, as food and space became more available as the caverns grew and became more oxygenated, some of the daggoths began growing in size. While still small compared to outside surface animals, reaching only a maximum of 90 kilograms in the largest "grazers", their size is nonetheless an incredible achievement given their environment and evolutionary history.

The lineage that would give rise to their largest species eventually diversified into low-level grazers, higher-level browsers, generalist omnivores and specialized macro-predators. But most basal of these are the grummlers, with the largest species being the giant grummler (Macroabyssomys maximus). These represent the earliest lineage of daggoths that began expermenting with size, with them resembling the basic daggoth but simply larger. With their increased weight, their multiple digits became more columnar to support their bulk, their reduced metacarpals forming equivalents of shoulder blades to anchor powerful limb muscles, while their phalanges grew stronger and thicker and developed a bony heel-like protrusion on the second-to-the-last phalanx to support a fleshy "sole" pad: in essence turning the spindly fingers of the smaller daggoths into sixteen proper "legs".

The greater grummler is a large and indiscriminate omnivore, feeding on mocklichens, meatmoss, bacterial mats, arthropods, smaller daggoths and carrion. Depending on the species, the several species of grummlers either lean toward a more "grazer" side or a more "carnivore" side: a distinction that is less drastic than surface animals given that some of their "plant" equivalents are technically animals as well, making them more accurately "meat-grazer omnivores" or "carno-herbivores". This dietary ambiguity of this lineage would lead to the evolutionary split between the "grazers" such as the molepedes and the biblarodons, and the predators such as the blindmutts, with the grummlers themselves representing a more ancestral state of this divergence. Indeed, leaning more on the "grazer" side, the giant grummler itself sometimes falls prey to smaller grummler species with more carnivorous tendencies, especially targeted if sick, young or old.

As larger-scale predation began to emerge among the macro-daggoths, a trend akin to surface animals started to arise among them--an arms race between increasingly armed predators and increasingly defended "herbivores", with hunters specializing to take down prey larger than themselves, and large prey developing weapons to better fend off would-be assailants.

One of the most notable examples of this would be the molepedes: a clade of macro-daggoths that developed elongated bodies and short limbs that allowed them to graze closer to the ground, feeding on filamentous, low-growing mocklichens that, in a loose sense, could be considered an analogue of "grass". These slow-moving creatures were afforded ample protection by their size alone in the earlier days, but as predators too began to grow, the molepedes gradually found themselves becoming outmatched. Over time, the ancestral soft-bodied molepedes disappeared entirely, too vulnerable to the new predators, but from it emerged two lineages: the thorny molepedes and the armored molepedes.

The common thorny molepede (Echinopolypodomys spinosus) repurposed many of the sensory bristle hairs of its body into defensive spines, covering its back, its flanks and even its nasal tendrils. These spines, barbed and loose like porcupine quills, embed painfully into a would-be predator's skin and remain stuck in the flesh as they break off. As a warning, they exude a distinctive scent from specialized anal glands that previously-quilled predators quickly associate with a painful experience.

However, while an effective means of self defense, the thorny molepede's defensive spines pose a significant challenge to its other routine activities: specifically, when it comes to mating. Thorny molepede courtship is an awkward affair, with both partners releasing odorous pheromones to communicate their amorous and non-hostile intentions. Once they reach a mutual agreement, they then very slowly and gingerly back into each other, until their rearmost quills barely touch, and the male, fortunately endowed with elongated reproductive equipment, is able to complete his job from a safe distance.

A less socially-challenged relative of the thorny molepede is the armored molepede (Armopolypodomys edurus), which is a far more gregarious creature than its spiny cousin and gathers in small groups of up to ten to twenty individuals at a time. Rather than spines, the armored molepede instead has fused its hypertrophied, hardened bristles into tough keratinous scutes, which form a coat of plated armor nigh-impenetrable to the claws and teeth of its enemies. When threatened, groups of then huddle together and press themselves down, concealing their vulnerable limbs and nasal tendrils and exposing only their armored backs. Their strategy is one of persistence: eventually, after hours of clawing and biting to no avail, most predators simply give up the hunt and leave to find easier food elsewhere, and once danger has passed, the armored molepedes once more unfurl and carry on their usual grazing.

Both types of molepede tend their young with a significant amount of care until their defenses grow in, even if only passively, with their numerous litters of up to twenty young at once huddling between the adults' legs, afforded protection by their armored or spiny backs. They are, however, quite precocial, grazing and moving on their own shortly after birth, and, once sufficiently developed and defended at the age of five or six months, gradually disperse from their parent to lead an independent life.

Such defenses have become a necessity for the great grazer daggoths, as predation became more of a significant threat with the evolution of the cavern system's first proper apex predators, the blindmutts. Earlier forms simply preyed upon smaller daggoths such gothtles and xenomures, but, as prey species increased in size, so did some predators, leading to the development of some advanced blindmutts able to tackle large prey such as molepedes, biblarodons and grummlers as well.

The mandibled tendriltooth (Abyssatrox xenoailuroides) is, in the Middle Temperocene, the caverns' undisputed apex predator: even if it grows only to the size of a large house cat. Its most notable adaptation is the development of sharp, hooked keratinous spines on six of its seven nasal tendrils, which have become thick and muscular and adapted for gripping: in essence becoming six additional jaws with false "teeth". Two of its foremost digits, its central nasal tendril, and its two rear digits act as sensory feelers able to navigate its surroundings with a delicate sense of touch, while it homes in on prey with a powerful sense of smell and hearing. Once it locates its prey, it tries to grapple it with an ambushing pounce before using its six main limbs to anchor itself with its claws, and using its toothed tendril-jaws to secure a firm grip on the prey's neck before using its true teeth, sharp dagger-like incisors, to inflict a fatal bite to the prey's neck. As it targets prey larger than itself, the tendriltooth may take several days to eat its fill, and will camp out next to the carcass over the following days, fending off rivals and scavengers that may come to steal its prize. As its prolonged feeding lasts for a duration long enough for putrefaction to set in, the tendriltooth has evolved an extremely powerful set of digestive juices that allow it to continue feeding on even decomposing meat. Eventually, however, once it has sated its fill, the rotting carcass is then abandoned, and now unguarded, a buffet of scavengers then descend on the carcass, ranging from insects and worms to maggoths and xenomures to even rumptusks, vulpemousers and grummlers, all clearing up the residues the tendriltooth leaves in its wake.

Tendriltooths may reign as top carnivore, devoid of any predators of their own, yet their existence is still a precarious one, as they are few and far between given their placement on the food web. Throughout the entire cavern ecosystem, filled with millions of daggoths of different species, there are never more than a few hundred adult tendriltooths at any one time, being solitary and territorial, as they need plenty of space to sustain themselves. Tendriltooths are fairly prolific, with litters of up to twenty to thrirty tiny offspring at a time, but these small but precocial offspring, independent after only a few weeks, have a rather high mortality rate: during their early youth, where they prey primarily on insects, they are indiscriminately themselves prey for various medium-sized carnivores such as vulpemousers and smaller blindmutts, and, once they themselves graduate to medium-sized carnivore status hunting larger prey like xenomures, now have to contend with adult tendriltooths who will target the subadults to get rid of potential competition. However, should a lucky tendriltooth survive its precarious first two years, a feat accomplished by less than five percent of all juveniles, it is assured a niche of apex predator, unbothered by any other creature and with only another adult tendriltooth to fear.

------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative zoology#hamster's paradise#biome post

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mistreatment of a Sacred Plant

Recently, I had an unpleasant emotional and spiritual shock. I struggle a bit to talk about it because of how upset it makes me, but I feel like the subject matter is important enough to warrant the discussion.

As some may know, one of my dearest plant allies is the Ghost Pipe. I work closely with Monotropes in general, but the Tutelary Spirit of Monotropa Uniflora, in particular, serves as a chief Plant Patron of mine. Part of maintaining this relationship involves visiting a specific location in a devotional capacity, in order to watch, tend, and learn from the population of Ghost Pipes that grow there. I went back to this place not long ago, in order to thank the spectral flowers for lending their power and grace to our Handfasting Ritual, and I was horrified to discover that every one of the colonies I've stewarded over the last few years is completely gone.

They aren't a major food-source for any animals I know of, and this was way more than a die-back, since I recognize what that looks like. What's more, for every colony to have naturally vanished without a trace since the last time I visited was unthinkable. As such, I'm all but sure that someone "Wildcrafted" them to make tinctures for sale. This is absolutely heartbreaking and infuriating, as they have totally misused and abused this sacred plant, and damaged an extremely fragile and unique ecosystem in the process.

The main issue with harvesting Ghost Pipes isn't necessarily that it's rare, though it is in some areas. The real problems are how sensitive they are and how exacting their life cycle is. Sometimes, just touching a Ghost Pipe is enough to damage the plant, disrupt the re-seeding process, and prevent it from growing back. What's worse, the conditions required for the succesful development of these ethereal organisms are extremely specific. Monotropes are Mycoheterotrophs, which derive their energy through mychorizal parasitism. This is to say, they can only get their energy by siphoning it from a small range of subterranean fungi, who in turn, siphon their energy from the roots of certain trees. Between these and other factors, Monotropes are virtually impossible to cultivate or propagate, and they are especially susceptible to the effects of overharvesting. Unfortunately, unethical harvesting has steadily become a real problem in Western Herbalism, where Ghost Pipe tincture is growing in popularity for its mystique and its beautiful violet color. And while it does have a long history of traditional medicinal use as a Nervine, people who aren't getting it purely for its aesthetic qualities are buying it as a miracle cure, without any real understanding of how or why to use it.

I've been muddling through strong feelings of anger, sorrow, and impotence since this happened, and I feel sick thinking about someone out there irreverently peddling this precious medicine under a capitalist guise of "Herbal Wisdom." These sorts of business practices are thoughtless, ecologically unethical, and spiritually blasphemous (as far as I'm concerned). So, I beg you: please think thrice about what you are doing before you harvest a plant. Ask yourself these five questions, and weigh the answers against each other: "Why do I want to harvest this plant?' 'What harm will my behavior cause to this organism?' 'What harm will my behavior cause to this species?' 'What harm will my behavior cause to this ecosystem?' and, 'What will I suffer as a result of not harvesting this plant?

I offer up my most fervent prayers that the seeds I helped to spread earlier in the year will count for something.

#ghost pipes#ghost pipe#monotropes#monotropa#monotropa uniflora#foraging#harvesting#harvest#herbalism#plant magic#plant medicine#nature magic#herbal medicine

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Common Bluebell (Hyacinthoides non-scripta)

Family: Asparagus Family (Asparagaceae)

IUCN Conservation Status: Unassessed

Adapted to life in deciduous forests with dense canopies that limit the degree to which low-growing plants can access sunlight, Common Blubells survive by rapidly developing and reproducing during the early spring before the trees around them develop their leaves. In the later spring and early summer, as taller competing plants develop leaves, the flowers, stems, leaves and even roots of members of this species wither as they enter a dormant state until the following spring, with only an onion-like subterranean bulb, packed with sugars produced through photosynthesis during the non-dormant period, remaining; come next year's spring, the sugars in the bulb are used to facilitate the rapid development of new roots and leaves, allowing the bluebell to repeat the process year after year. Common Bluebells can reproduce both sexually (producing 5-12 small, pale-purple bell-shaped flowers that droop notably to one side when in bloom, with each flower possessing pollen-producing "male" organs and pollen-receiving "female" organs, with any flower that is pollinated developing into a small seed-filled pod that drops its seeds as the plant goes dormant) and asexually (with new but genetically identical bulbs, known as "daughter bulbs" developing as offshoots from the sides of an existing mature bulb, known as a "mother bulb",) and as they thrive in shady deciduous forests and are unable to easily disperse their seeds or bulbs over any great distance, it is not unusual for the understory of a forest that supports members of this species to be completely dominated by them during the spring - such forests are referred to in some regions as "bluebell woods'."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Image Source: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/56132-Hyacinthoides-non-scripta

#common bluebell#Common Bluebell#bluebell#botany#biology#angiosperm#angiosperms#flowering plants#flowers#plant#plants#wildlife#European wildlife#flower

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mushrooms are the temporary reproductive structures of massive, seldom seen, subterranean creatures more closely related to you than to plants. Fungi. Some are miles wide. Some live thousands of years. Some help trees speak to one another. There’s magic beneath the forests.

466 notes

·

View notes

Text

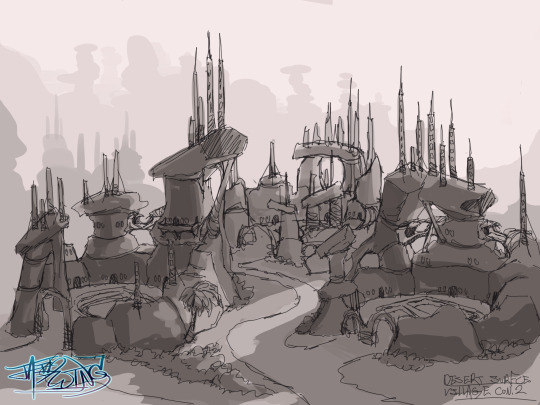

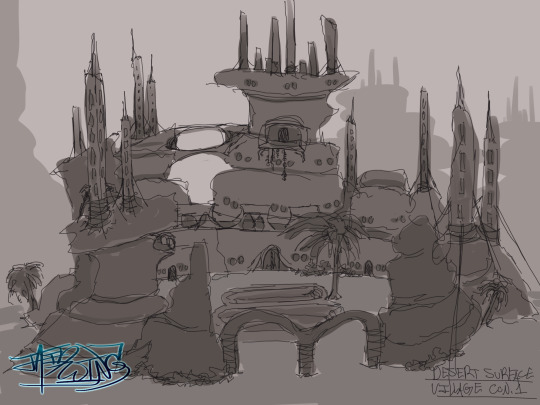

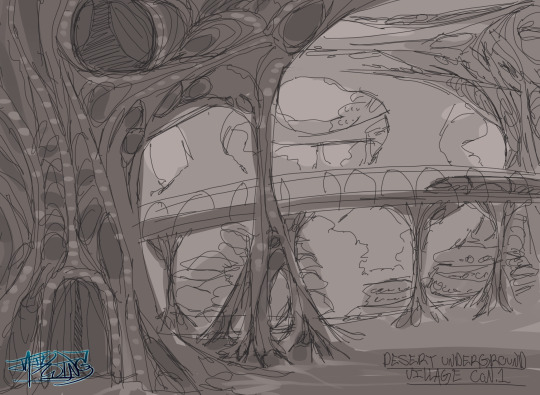

Desert Loreirran village concept art

I’m not that great at architecture, so I’m practicing it with some village concept art. I’ll definitely me making more here soon. This is a good time to also talk about the desert village architecture. (Information under the concept pictures)

1. Building Materials:

The desert region Loreirrans utilize a combination of natural materials to construct their desert homes and city buildings. These materials include:

- Sand: Sand is used as a foundational element, providing stability and insulation against the desert's extreme temperatures.

- Mud and Clay: Mud and clay are mixed with water to create a binding agent. This mixture is essential for forming the structures and keeping them sturdy.

- Plant Wastes: Various plant materials, such as dried leaves and stems, are added to the mix. These materials contribute to the insulation and help regulate the interior temperature.

- Water: Water is a precious resource in the desert, and it is carefully used to moisten the building materials and facilitate their molding.

2. Cooling Architecture:

The desert region Loreirran buildings are ingeniously designed to maintain a comfortable interior temperature, even during scorching summer months. Their architecture includes:

- Thermal Insulation: The combination of mud, clay, and plant waste acts as natural insulation, keeping the interiors cool during the day and retaining warmth during the chilly desert nights.

- Ventilation: Buildings feature strategically placed openings and wind-catching structures that facilitate natural ventilation. Cross-breezes help regulate the indoor climate.

- Shaded Courtyards: Courtyards within villages and towns are often surrounded by buildings, creating shaded areas where residents can seek relief from the sun's intensity.

3. Surface Villages and Subterranean Cities:

The Loreirrans have adapted their architectural styles to suit different settlement types:

Surface Villages and Towns: These settlements are typically located in proximity to natural rocky formations and hills. The Loreirrans mimic the rounded and occasionally pointed shapes of these geological features in their building designs, ensuring that their structures blend seamlessly with the desert landscape.

Underground Cities: In larger urban centers, Loreirrans construct underground cities to escape the extreme surface temperatures. These subterranean cities are accessed through large sun holes in the ground. Roads connect these cities to the surface, allowing for transportation and trade.

4. Aesthetic Variations:

The aesthetic of Loreirran architecture varies based on the specific location of a village or town:

- Rounded Structures: In areas with smoother rock formations, Loreirran buildings adopt smooth and rounded shapes. These structures flow organically with the surrounding landscape.

- Pointed Structures: In regions with more rugged rock formations, some buildings may feature natural pointiness to mimic the local geological formations, creating a unique architectural style that honors the desert's natural beauty.

#alien#Loreirrans#concept art#loreirran#concept architecture#aliens#village art#art#artist on tumblr#icera 5#digital artist#digital sketch#digital drawing#concepts#original species#original character#world building#original alien species

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

While there are countless searing parasites who can serve as the face of the Arimakki, to all, there is only one symbol, one heart, that truly defines them. It is a thing that is even more mysterious than the odd bugs themselves, something that many still struggle to understand. Even its name fails to properly describe what it truly is, but there are no other words to use for it: The Vile Red Tree. Yet, it is no tree, it isn't even a plant. There is no bark, no leaves, yet it grows like an insidious weed. It has no need for sunlight, or water, as it lives underground, growing in the heart of every Arimakki colony. It is no animal or plant, yet it lives. Its hardened brittle form slithers and splinters as it spreads throughout the underground, eating its way through ancient flesh and soil. From its stony red flesh emanates a sweltering heat, a feverish temperature that only an Arimakki can love. It is a searing atmosphere it exudes, far greater than any single parasite can muster. It is this burning presence that makes each Arimakki colony an oven, the heat so intense that no other living creature can survive long without protection. And as it grows, the heat follows, baking the earth and clearing the way for its horrible children.

This bizarre burning organisms does not grow alone, as with it are the White Worms and other strange creatures. To most, the White Worm is an unassuming thing, a pale featureless squirming thing, found infesting every Arimakki. But where the Vile Red Tree grows, the White Worm is close at hand, writhing through the earth and dancing amongst its subterranean branches. What the connection is between the two is unknown, as folk aren't even sure how they play into the Arimakki themselves. The best guess is that the Vile Red Tree and the White Worms are crucial to the reproduction and spread of the Arimakki. Why else would they be found within the heart of every colony? Why else would these pale worms be filling every cavity of the parasites? It seems both are needed for these horrible bugs to survive. The Vile Red Tree is believed to create the horrible heat that is needed for Arimakki eggs to hatch, while the White Worm burrows through the world around them and prepares the flesh for infestation. It seems the Vile Red Tree can only grow through substrate that has been thoroughly infested by the White Worm, and perhaps the internal worms are how the Arimakki digest their food. But in the end, these are only guesses, as every part of the Arimakki hive is nearly impossible to study, let alone survive.

Due to the critical role the Vile Red Tree plays into the spreading of the Arimakki, many are correct to assume that its destruction is necessary to dispel this threat. Smaller hives who have had their trees destroy turn sickly and weak, and the bugs are seen desperately trying to reseed their dying tree. Yet, eradicating the Vile Red Tree is no easy task. Blows against it shatter it and scatter its pieces, raining blistering sharp shards across the land. Wherever a fragment lands, a tree will be soon to follow, as they regenerate and spread like a disease. Those who get its barbs into their flesh are nearly driven mad from the experience, as it is a searing needle that digs deeper and deeper into the flesh, spreading fever, burning and crazed itching. Those who still have it within them experience horrible hallucinations and are tormented by twisted impossible nightmares. If a doctor is not able to extract the sliver from their flesh, most are driven to such insanity that they will gnaw their way to it and tear it out with bloody teeth.

To make matters more confusing is that the White Worm is not the only thing that writhes amongst the buried branches of the Vile Red Tree. A whole slew of terrible worms spend their entire lives around it, playing some role or purpose that no one can understand. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes, yet their jobs are a mystery. The blanket name of "Arimakki Wamu" is given to them, and it seems that they need the Vile Red Tree as much as it needs them. With how the variety of Arimakki seems to be endless, one can only figure that these are another staple of these colonial organisms, a handful of the many that make the Arimakki whole.

The Vile Red Tree and the White Worm remain a mystery and a terror, haunting the land and many dreams. Maddened tongues speak of its growing through the earth and beneath our feet. Crazed visions see the earth cracking open into writhing worm-filled wounds. The shivering sleepers look up in their dreams and see a boiling sky and a horrid tree of red devouring the heavens.

-----------------------------------------------

"The Vile Red Tree"

And I forgot to add the White Worms! Confound it!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

day 18 monster kelp

my favorite plant ever. i love especially the one in subterranean

support me on ko fi so works like this are possible!

#my art#rw art month#rain world#rainworld#rain world fanart#rw monster kelp#rw subterranean#digital art#digital artwork

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

IN DEFENSE OF THE ALIEN DESIGNS IN STRANGE WORLD

@themousefromfantasyland @the-blue-fairie @tamisdava2 @minimumheadroom @thealmightyemprex @amalthea9 @angelixgutz @grimoireoffolkloreandfairytales @softlytowardthesun @grimoireoffolkloreandfairytales

So, I read on-line some comentaries saying that it was hard to connect to the titular Strange World because of how out of this world the alien creatures were.

Their designs were considered too strange, to the point of being considered scary by audiences, who expected those creatures to be intimidating monsters, rather than the neutral, if simpathetic beings they were portrayed as.

This characterization apparently didn't correspond to what is expected from their appearance.

And I started to investigate in my memory: why this disconect happened?

Why it was more easy to imagine those beings as villanous monsters, rather than the simple living beings they actually were portrayed as?

So, when it comes to other worldly creatures written in fantasy and science fiction works, since we are humans, it has historically been more easy to connect to alien fictional creatures that are closer to humans, or at least other mammals.

The more distant they looked from humans in appearance, usually closer to reptiles or insects, the more likely they were to be presented as villanous monsters that must be eliminated by the heroes.

In fantasy you have the usual conflicts between heroic and appealing humans, elves, dwarves and halflings against the villanous and grotesque orcs, goblins and trolls.

And in sci fi, the more sympathetic aliens are the ones that look close to humans, while the more far from humans that alien is, the more likely is that they will be the treat to be fought.

In the Lindsay Ellis video "Designing the Other", she brings up the important point on the emphasis on eyes to make audiences form a connection with an alien character.

When they have big, expressive humanoid eyes, they are more likely to win the audience's simpathy:

When their eyes are more insect like, or non existent, then they become mysterious, threatening monsters:

Jack Saint's video "Avatar: Dances with White Saviours" comments that the presentation of the planet Pandora and the native Na'Vi as conventionally beautifull is used as the main argument to make audiences simpathize with it and support its message of echological preservation

While less mainstream literary sci fi would present the message that even the non beautiful, even violent ecossystems and creatures are important for the balance of the enviroment and have the right to be preserved.

And then there is Strange World

Strange World presents a story where a team goes trough the subterranean to save the plant that is their source of eletricity from creatures that they perceive as an agricultural plague.

The creatures follow the design pattern that we usually associate with monstrous, villanous aliens: far away from humans or other mammals, closer to insects, sea creatures and abstract cells.

We look at their appearance, and feel fear, treating them like abominations who would destroy us.

And the narrative knows that. Is an important discussion in the narrative.

When Jaegger joins the journey with the team, Ethan tries to show him and Searcher the card game Primordial Base, which is about finding peacefull solutions to live in harmony with the enviroment surrounding you, which includes the creatures you consider threatening eldritch abominations.

At first, Jaegger and Searcher fail to understand what Ethan says.

Then, they learn what his words means when they see that the supposed plague that they come to destroy was actually an imune system working to heal the living heart of their world, from Pando, the plant that for years they tought was beneficial.

The saviours of their lives are the beings that they believed to be monsters.

Just because something is not what we perceive as beautiful, doesn't mean its evil.

That is the message that the characters had to learn to be alive.

And by extension, us, as the audience, had to examine our decades of biases on who is good, and who is bad, in the proccess.

Nature is neither good, nor bad. It doesn’t care about us.

It just is. That is enough reason that it needs to be respected and preserved.

31 notes

·

View notes