#so is vardamir

Text

elladan has Opinions about aragorn's elessar outfit

(btw arwen & elladan have silver hair in this one bc of their treelight hair thing)

#silm#silmarillion#lord of the rings#lotr#aragorn#arwen#elladan#hc: elronds family uses the nickname 'el' for literally everybody#[el]rond; [el]ros#[el]ladan; [el]rohir#est[el]; undomi[el]#+ [el]wing; [el]ured; [el]urin#the sleeve things aragorn has are meant to be worn with a different shirt/robe#so you can have a fancy loose robe or shirt but functional sleeves#which is especially helpful for people with a craft where you dont want sleeves getting in the way#but aragorn for some reason is wearing a matching sleeveless shirt and shirtless sleeves and defeating the point of both#so is vardamir#though he at least has the excuse of having a craft that actually benefits from the separate sleeves

111 notes

·

View notes

Note

First of all congrats on nearing the end of your PhD program!!! Woohoo!!!

Second of all, I’m muy late to the party here (been off tumblr for a bit) but WRT these tags ( https://www.tumblr.com/anghraine/749212904253947904/khazzman-tolkien-elendil-was-called-the ) what do you mean the pregnancies were strange lol how strange can they be…?

As for the first point: Thank you! I'm really looking forwards to being done, lol.

As for the second point: anon, I delight in your innocence. In fact, I delight to such an extent that I wrote a long and rambling explanation over on my Dreamwidth account. It's here.

An excerpt:

#anon replies#respuestas#nice things people say to me#legendarium blogging#legendarium fanwank#anghraine's meta#the nature of middle earth#jrr tolkien#elves#team dúnedain#númenórë#long post#míriel#nerdanel#fëanor#etc#total tangent but tolkien's wrangling with the maeglin timeline in terms of the developmental math is also very funny#and leads him to remark as a casual aside that part of the reason that idril was so put off by maeglin's attraction#apart from the incest and his personality and the other issues is just that he was significantly younger than her#not a literal child in elvish terms but still. kind of a kid as far as idril was concerned#also jrrt suggests that eöl was not avari/sindarin and 'dark elf' could be a pejorative term for /noldor/ who didn't finish the journey#like in this version the noldor don't see eöl as racially inferior but as another noldo who's just kind of a loser personally#wild shit but just dropping 'oh yeah vardamir got the choice' before breezing on kind of eclipses them all#the silmarillion

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finrod Felagund. "Philosophic discourse regarding the enmity of Orcs with Elves." The Philosophy of Finrod Felagund. 2nd ed., edited and translated by Vardamir Nólimon, Armenelos, S.A. 130.

[Ed. note: Private papers of Finrod Felagund. Written in his own hand. Dated to the season of Firith in the year 455, shortly before the Dagor Bragollach.]

Fact: According to the lore of our people from the days of Cuiviénen, the Enemy fashioned Orc-kind by his torture and slow corruption of Elven captives.

Question: How did our people learn this lore? Can it be that any ever escaped from the depths of Utumno to serve as witness?

Fact: In the lore we got of the Valar there is to my knowledge no teaching regarding the origins of Orc-kind.

Conjecture: It may be that our lore is not reliable on this point.

Fact: There are a few among us who dwelt at Cuiviénen, and others of their number abide yet in Aman; none of them have to my knowledge disputed the accuracy of our lore on this matter.

Fact: The fëar of Elves and Men have their differences from one another, but none so fundamental as the distinction between the fëar of the Eruhíni and the spirits of the non-speaking creatures. The spirits of non-speaking creatures cannot properly be called fëar, as the distinction in question is one of kind and not of degree. (Indeed fëar cannot be spoken of at all in terms of degree or size, as each fëa is itself indivisible.)

Fact: The lore we got of the Valar tells us that the fëa cannot be destroyed by any means.

Fact: Also of that lore, we know that the Enemy cannot truly create, only twist in mockery what has been created.

Fact: Also of that lore, we know that the Dwarves have their fëar of Ilúvatar alone, and not of Aulë. Before the granting of their fëar they could not speak, nor had they any will of their own, but could only obey the will of Aulë.

Fact: Orcs speak, and there is sense behind their words.

[continued on Ao3]

#finrod#finrod felagund#silm fanfic#silmarillion fanfiction#silm#silmarillion#the silmarillion#tolkien#tolkien fanfic#tolkien fanfiction#my writing#my fic#in which finrod is a NERD and also a very good heart#in-universe philosophy as angst is after all his Thing (as well as andreth’s)#finrod is my son and i give him my orc emotions. i do this because i love him

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hold His Own | on ao3.

Elros and his family, for @nolofinweanweek.

Elros left his children the tools and the means to commit all the mistakes of his forefathers, and new ones besides; and he was not sorry for it in the slightest.

(All of them come to him in the dark once at least, crying and seasick, wanting to be held and sang to quietness. There was a wave, little Vardamir said it first; and his children after him, too, weeping and afraid as he had vowed they never would be. A wave, and it was angry, and it came for everything).

In his old age, Tar-Minyatur looked little older than his grandson's children. Silver was in his hair, and the silver of his eyes a little dulled; but his mind was sharp still, and eager. He walked the quays every day, and bent his back on harvesting seasons.

Only his son's growing weakness kept him from venturing out on the fishing vessels that scoured Ulmo's realm for fat tunas and rich whales - and all his children and their children were raised more on tales of the first eventful seal-hunting expeditions up and down the shores of Númenor than on tales of Beleriand.

Sirion, Doriath, Gondolin and Hithlum - those came later, when they learned their letters and their histories. His brother, in love with lore and the keeping of lore, would argue against it, and no doubt rear his children in the wisdom of Melian's line and the solemnity of eternal memory.

Elros was mortal. He raised his people to love themselves first of all, their cities and language and ways. They sang new songs every season, composed new and useless rhythms with dizzying speed - and the king of Elenna, who had grown among enemies, and made war on Melkor, delighted above all things in this speedy work, the restless pettiness of every day's effort.

The work of one's hands was rarely more beautiful than when it was raised up to protect against wind, hail and spray - than when towers were raised on strong foundations, and around them cities raised on beautiful lines.

He wrote his deeds and thoughts in treatises and decrees, the lore made to be read by lore masters in centuries to come. It was important to keep the past alive, and prepare for the future, study portents and ignore not foresight - Yet not, Elros wrote in the letters he tossed at the waves, Mithlond-bound, at the expense of this year's seaweed nurseries.

Vardamir was hungry enough to learn, and Tindómiel cared mostly for the business of the ships and the studies of the stars - Atanalcar went pearl-diving most of the summer, every summer of his life, and Manwendil liked riding best of all, and was a friend to the sea-birds that brought him small tokens of sea-glass and feathers.

Elros left his children the tools and the means to commit all the mistakes of his forefathers, and new ones besides; and he was not sorry for it in the slightest.

(All of them come to him in the dark once at least, crying and seasick, wanting to be held and sang to quietness. There was a wave, little Vardamir said it first; and his children after him, too, weeping and afraid as he had vowed they never would be. A wave, and it was angry, and it came for everything).

He soothes them all. Lullabies, half-forgotten and half-improvised, sweet with Menegroth's lilting rhymes; a few tries at the harp, and their little heads rested trustingly on his shoulder, asleep without fear again.

Dreams were only dreams, in the morning. None of them saw bloodshed before their coming of age; none of them would shed blood unjustly, for greed.

Tar-Minyatur knew this, because they were his children. He knew also that their children were like to have children themselves, and for all the friendship of the sea, an island was only so large and plentiful as the number of its people allowed them to be.

The gulls brought gifts to him, too. Perhaps they would do so to his descendants, too, five or ten births down the line, if not twenty. Did birds lose the keenness of their memory, as old men did?

The king's windows were always open, to the fresh star-lit light of the evening, when the weather allowed. In his last years, his bones turned into tyrants even on warm nights, but Tar-Minyatur found time to evade his minders, to bring out his bowl of seaweed and dumplings to the parapets of his towers and speak to Gil-Estel all the same.

All the old people of the island did, when they were soon to die. That last bearing of witness, some of the Edain held, was what stars were for, and this one most of all.

They may choose to tear them down in time, and build them anew, wrote Tar-Minyatur, silver-haired and trembling with the cold of an open window, young still in a way his brother would never be again.

He had taken to reading old philosophical texts with his son's grandchildren, now that they were old enough to be interested in these things, to know death and be a little angry at it, and petulant about the old king's way of teasing them. They went off to complain to Vardamir, who explained everything a little better, a little more sensibly.

No one had called him Elros in many years. All the same, the king wrote: Let them be as they would! That will be their choice! But they shall choose, and choose to look onwards, not back into the unalterable past. The best gift I can give them is to give them some stone and soil to stand upon, and the will to go onwards as they would, with the years they have to live.

Tar-Minyatur raised his children to know this. Great and terrible things came of that, and he foresaw many, if not most; but then, one must think of this day's effort most of all. The future would come, as certain as the tides and the summer storms. It was enough to leave behind strong foundations, and something of estel to pass onwards. All wise old men in Elenna knew this, and held it to be true.

#elros#elrond#vardamir#tindomiel#silm fic#nolofinweanweek#nolofinwëans#the fall of numenor#my fics#tolkien fanfiction

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

ulmo grants his favourite couple a gift on the day of the birth of their first grandchild. written for the @yearoftheotpevent april prompt ‘peace’.

It was sometimes said by the Men of Númenor that in the early days of the reign of Elros Tar-Minyatur, the Star of High Hope was four times seen to shine in place from morning till night, never moving nor fading, and this tale was indeed the truth.

~

Elwing, albatross, soared with the rising dawn to greet Eärendil her beloved aboard Vingilot as he drew in towards her tower. She landed on the deck barefoot in her woman-shape, nude, and wound her arms around his shoulders.

This was how Elwing began each day in Aman, yet this morning was different. For instead of preparing to land as always, as she released him Eärendil raced to the wheel at the bow and turned, so that the great sail billowed across the other side of the wind, and Vingilot turned.

“We haven’t time to spare!” he cried, “Ulmo came before me as I sailed tonight, and he spoke to me of one blessing he has granted us; but only for today- we must make for Númenor with haste!”

~

Elwing dressed herself in Eärendil’s spare tunic (too wide in the shoulders) and trousers (which barely grazed her ankles), and returned to Eärendil’s side on the deck. He wrapped an arm around her waist, and pressed his face into her neck, breathing her in, the light of the silmaril bound to his brow glowing in the blue-black of her hair.

“It’s beautiful in the dawn,” she said, meaning the ocean, and it was. The coral-pink sky sparkled with Arien’s light and the light of the silmaril on the water, and off the coast of Aman it was so clear that flying low as they were, they could see shining pearls tossed about on the sea-floor, and fish like many-coloured jewels.

As they crossed the Enchanted Isles, and over the wider sea, many among the great and small creatures of Ulmo appeared to the flying ship. There was the mighty whale Uin, shooting a jet of water up onto the deck in greeting as he swum among the islands; and as they came closer Elwing and Eärendil saw that one rock was no island at all, but the dread turtle Fastitocalon, yet he did them no harm. Swimming among a school of porpoise were a dozen mermaids with hair and scales of many colours, who rose to the surface and sung in a tongue unintelligable to see Vingilot; and following them was Uinen their queen, unmistakable in her beauty and fierceness.

After Uinen had passed, Eärendil raised the ship higher in the sky and Elwing armed herself with a boathook; for where Uinen went Ossë was sure to be close. Yet when they did encounter him, he simply skated over the waves and raised a hand to the mariners.

Eärendil smiled, and said that all the spirits of the sea must have come out to see his fair wife, and she laughed. And at last when they reached the star-shaped island of Númenor, Salmar appeared before them and he played the great horn of Ulmo, and the song awoke in the hearts of many mariners across the land.

High above the island they soared, and each looked down through a spyglass. As they flew, the seabirds of Númenor flew to join them, the sea-mews and the puffins and the gannets, and they spoke to Elwing and told her to sail as far as the Palace of the King in golden Armenelos.

~

Elros Tar-Minyatur, Elrond his twin, and his wife Gennoril and their newborn child, yet to be named, had waited since the coming of dawn under the tree of Nimloth for their miracle, and late that morning, it came. The star of Elros’ father shone upon his grandchild beneath the tree, and the boy smiled. And though they could not see nor speak to their parents, Elros and Elrond knew that they were with them then, and had never truly left their sides, and they smiled and wept.

That day, the Star of High Hope looked down on the royal family of Númenor until Arien journeyed out of sight, and Gennoril looked upon her child and said, “Vardamir”.

~

Elsewhere in the ocean, fishes darted through the wreckage of Sirion and mussels and limpets clung to the sunken skeleton of Ancalagon. The remains of Turgon’s ships continued to rot and crumble under the water, the bones of their sailors laid in the sand while their bodies reborn walked in Aman. And above it all, the Blessed Mariner and his wife winged with feathers looked down together as they sailed; and while they knew that the gift of today could not make up for their many losses, they held each other in gladness that it had been granted them all the same.

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elrond and Elros were lovers, and that's the founding of Numenor's royal family.

Elrond brings this up casually with Celebrian a couple years after they marry and is surprised she's so upset. She already knew that he'd had others lovers but promised he wasn't married and he was over all of them, what's the big deal?

Elrond and Elros were everything to each other. They had to be, with their family gone, their captors who raised them gone, their home city sacked, their childhood prison abandoned, the land they grew up in crumbling into the sea. They loved each other in every way, and relied on each other utterly.

But they knew it couldn't last. Elros wanted to venture beyond the very bounds of the world, while Elrond wished to learn everything he could about Arda no matter how many ages it took. Elros chose the fate of Men, and Elrond the fate of Elves, and in a few decades or centuries they would be sundered forever. Indeed they would be parted even sooner, as Elros was now a king of Men, and would leave to the Isle of the Gift to found his kingdom once things were prepared.

Elrond wasn't going to let him go alone though. Sure, Elros would have soldiers and servants and subjects, but no family. (Elrond at least would have cousins, Celebrimbor and Galadriel and Gil-Galad and Celeborn, even if no closer kin.) Elros needed someone who loved him unconditionally, who was devoted to him entirely, who understood the burden of royalty.

Elrond bore their first son. He named the boy Vardamir, as perhaps there were enough El- names in the family for now, but it was still good to honor the stars and their lady.

Elros took the next turn being pregnant, letting Elrond smooth ruffled feathers at Gil-Galad's court. They told no one, of course, who had gotten Elrond with child, as no one would ever understand. But the pregnancy and birth had been hard to disguise, and so too it was strange to all that the babe would be raised by his "uncle". Elrond explained that the child seemed like a Man, and so would have greater joy in a Mannish kingdom, and none but Elros knew enough to contradict him.

Tindomiel had just begun the flower of her maidenhood when Elrond bore the twins' third child. He spun the same tale about a mortal lover who didn't wish to be named, and a certainty that the child was mortal. No one quite knew how Peredhel inherited, including Elrond and Elros, but having a Man as another parent seemed plausible enough. And Elrond's repeated unwed pregnancies were scandalous and unconventional, but naming the boy Manwendil seemed appropriately pious. Elrond told his brother that he had no motherly foresight, only good wishes. But perhaps Manwendil and Vardamir would love each other as well as their namesakes; perhaps Elrond and Elros's love for each other would be reflected in their sons.

Vardamir was tall and strong with a full beard when he helped his king and father onto the ship that would take them to Numenor. Normally Elros was a capable sailor, but Vardamir worried for him, already halfway along in his pregnancy. It seemed fitting, for the King to be the first one to give birth in their new homeland, the youngest child of the royal family as the first native of Numenor. Truly, Atanalcar was evidence of the glory of Men.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caught at Low Tide

Hey, @aeondelirium (or rather, @aeondecember) I’m your Secret Santa! I hope enjoy this fic!!

Thank you to @officialtolkiensecretsanta for organizing this event!

Elrond mourns his brother, and so, naturally, he finds himself in the water and at the mercy of Ulmo, as his family always does in times of turmoil.

Today, the smells of muck and brine and smoke were thick in the sky. Everything felt heavy, weighed down by the oppressive moisture in the air that was trapped and pressed low by the dark gray clouds above. It wasn’t raining yet, though. No rain, but sharp wind, tumultuous wind.

“The king of Arda mourns,” Vardamir had said, eyes closed but lids fluttering, head tilted towards the stormy sky.

Elrond- and this was not his proudest moment- had snorted.

That certainly put a damper on the grim but glorious funeral proceedings of King Elros Tar-Minyatur.

To think, the king’s Elven brother exhibiting obvious and loud disbelief at the idea of Manwe’s consideration. Disdain at the idea.

And short-lived Men had so little personal experience with the Valar, they were so insecure and impressionable about if they were loved by Eru’s steward. Morgoth’s whispers still ran deep in their history and lore. Their fledgling faith lived on interpretable spectacle and small signs and little blessings. The weather probably was a sign from Manwe too! It was all just a harmless expression of grief and desire for comfort, and Elrond-

Elros had always held so much respect and awe and love for the Valar after the War of the Wrath and Elrond successfully unwound a good bit of his work building trust for them in Numenor with one snort.

Stupid.

His nephew forgave him, though. How could he not? Vardamir was a father, a grandfather, and an eldest child. He was made of nothing but grace and patience for tempestuous youths.

Elrond did not feel like a youth. He wasn’t one, though the Elves eternally thought of him as Earendil and Elwing’s sad little boy, and the Men? His traitorous niece and nephews had aged to the point of graying and not respected him since. Even his little brother, in his last years, had treated him gently and sweetly, like he was a child.

It was humiliating, but what was more humiliating- Elrond felt as he sat in Elros’s chair in Elros’s study and felt small in the shadow of Elros’s death- was that he was validating them by acting like a child.

Can’t I be forgiven today? he thought bitterly, twirling an eagle-feather quill that he gifted Elros in his hands.

He already knew that he’d long since been forgiven for any indiscretion. He’d be forgiven anything this week. Fuck, but Elrond had been forgiven for everything his entire life, by everyone, with no hesitation, no quibbling, no reservations. Not even loving kinslayers or refusing the personal invitation of Manwe and Varda to join his parents in Valinor was beyond the good grace of Gil-galad and his court of the well-intentioned.

Ai, Elwing and Earendil’s little boy has suffered so much, give him time, we Elves have so much time.

Elros, though, noble Elros, Earendil and Elwing’s kingly son, he had not so much time and what wondrous things he did with it. He matured so quickly didn’t he?

But none of them- not the court of Lindon, not the children of Numenor whose predecessors had aged and turned over so many times the Elros was following in the wake of hundreds of his true friends, not even his nieces and nephews- knew Elros as Elrond had known him. They did not know him angry. They did not know him sad. They did not know him scared. They did not know him filled with regret and loss until his last, not nearly so unwavering as the many speeches given in his honor suggested.

My hands are shaking, Elros had said to him in their last private conversation together. I don’t know why. Fear? Excitement? Strain from hanging on? Or, perhaps it’s just death setting in.

He’d laughed.

All of that, maybe.

Elrond was taken with the urge to snap the quill in his hands in half. No one could get mad at him for that. He’d given this quill to Elros. No one could get mad at him for breaking it.

Slowly, Elrond set it back down.

He didn’t know why he was sitting here. Well, he did. He knew why. Vardamir wanted him to give a speech, and this was the only place where he might reasonably be left in peace to write one. The new king still balked at entering his father’s study. His siblings were not quite so deterred, but after Elrond glared Manwedil from the room, none had tried again to bring refreshments.

Elrond didn’t want refreshments. He wanted to wail for his fucking brother, the version of him that only he knew. That was the only version of Tar-Minyatur he could think to write of, but no one wanted to hear of that boy.

An Elros who was not perfectly magnanimous, perfectly in control, perfectly at peace all the time? Perish the thought. No, really, perish it. The first King of Numenor could not be remembered as anything but perfect.

Whenever Elrond had complained about the spectacle he was currently living through to his brother in years leading up to his death- during the long planning of a funeral that wasn’t yet needed, something that still baffled Elrond- Elros had just smirked.

“Come now, I know you appreciate the importance of a good show. We were taught the same lessons after all.”

Yes, he had been, and Elrond was still sure that Maglor would find this week-long event just as macabre and odd as he did.

But Men were odd creatures. Well, at least as odd as Elves, but unlike the former, Elrond had never claimed to understand Men. He’d understood none but one, but through him- and Elros through Elrond- he’d felt like he’d understood the whole world. And now…

Now, Elrond pushed back from his brother’s chair to stand, and turned towards the large, open space at his back. Past two glass doors that were hardly ever closed was Elros’s ‘balcony’, though it was as large as a courtyard, strewn about with couches and chairs and braziers; cushions, tables, and children’s toys. There was a telescope mounted in one corner, a liquor cabinet in another. This is where Elros's family had practically lived.

Deserted now, except for Elrond, at Elrond's own desire. He’d feel selfish for monopolizing this space in these days of mourning, which were different but no less hard for his nieces and nephews, but the weather was so bad. No one would want to sit out here anyway.

He meandered outside.

With the day so dark and gray and miserable, it was no wonder that it was starting to drizzle. Manwe must have had a hand in the weather, because this was truly how mournful days should look; all the poets and singers agreed. Strange then, how overcast always took Elrond back to days that made sense.

Back in the days where Morgoth’s smog clouded the sky so heavily and consistently, they hardly ever saw the sun and moon, and never the stars- except for one. Now knowing that the silmaril sailed the sky, even in those days, Elrond often mused that if he’d just put a little thought into it, he might have realized what that bright light up there was. Maedhros and Maglor certainly did. But they never told and Elrond and Elros never figured it out. They were far too busy.

Survival occupied their every day.

During their roaming march- never in one place for long for fear of assault; ostensibly from Morgoth’s forces, but assaults from other peoples was always an unspoken possibility- there was never any time for long bouts of contemplation. Everyone worked. Elrond and Elros gathered wood, set up tents, trapped animals, fished, cooked, cleaned, bore wine and water during war meetings between the Sons of Feanor and their commanders.

And in between their chore, they learned, learned, learned.

“Are they not princes of the House of Finwe?” Maedhros had once growled at a former mathematician turned spearman who was foolish enough to question what the point of schooling in this day and age was. “They will learn how to compunct themselves as proper lords; polite, learned lords. Has Morgoth taken our pride, sir? Or just yours? No prince of the Noldor shall go uneducated.”

He’d spit that word like a curse, ‘uneducated’. That had always stuck with Elrond, it was so different to how their mother thought. Elwing had prioritized knowing the most beautiful songs- that sounded just a little prettier in her voice- and understanding the ebb and flow of nature. Maedhros wanted them to know grammar.

And Elros and Elrond hated it, they really did. The days went in and out like that, chores and lessons, lessons then chores, meals spattered in between, and it was exhausting. They slept hard at night. Things were simple, though. Those days were occupied with routine, with familiarity, with certainty.

Routine, familiarity, and certainty can bring fondness to even the most gruesome of times, as long as they came with fairness. Or complete lack thereof. Nothing was fair in Morgoth’s Middle-earth, but that was its own kind of equality. It was the kind of cruel environment that brought clarity, like who you could afford to have as an enemy and who you couldn’t.

Like grief is a feeling that is inevitable and should be dwelled on for as short a time as possible. Spending too long on grief just brought more of it.

Now, though, with Morgoth vanquished, they all just had too much time on their hands. At least, that's how Elrond felt about it. Too much time for funerals, too much time for kindness, too much time for thinking.

“All I do these days,” Elrond muttered to himself, head tilted back towards the rain, “is think until I’m miserable.”

And now he did not even have Elros as a sounding board to tell him that he was being stupid.

A sob welled up again in Elrond's throat, and he swallowed it with a shout, stomping up and down. Dammit, dammit, dammit, he was tired of crying. He was tired of crowd-appropriate sorrow. He wanted to move, he wanted to-

Elrond danced miserably- stamping his feet with great power every time he landed- around the patio where he and Elros had so many joyous moments, so much happiness and love that they couldn't even imagine as children, and he hated all of this.

Elros lived such a good life. He lived such a good life. A happy, full life, overflowing with legacy that was being celebrated and carried on, and he’d been content to die. Elrond had helped his brother make this choice, he thought he would be content to see Elros die when the day came. But he wasn’t.

He fucking wasn’t.

Taken by a manic fury, Elrond sprang across the balcony towards the telescope, climbing his way onto the balustrade it was perched on, and leaned. He latched one hand around the pole that held up the telescope, planted one foot on the slippery rock beneath him, and leaned over the edge, one leg in the air.

“Why does everyone leave me!” he screamed at the sea and the sky and the western horizon of Valinor.

Elrond received a mouthful of seawater for his efforts.

Hacking and coughing, he looked ruefully at the waters below. Elros’s study was a hundred feet above the shoreline and it was low tide. If water was reaching so high up just to make Elrond’s day that little bit worse, it must be…

Elrond started to climb down the cliffside.

Damn Ulmo, he thought as he started painstakingly maneuvering his way down the sheer, wet rocks of Numenor’s western edge. Damn his water and his oceans and his meddling rivers.

Oh, how annoying they had been when they were children, trying to sweep them down stream, away from the kinslayers. To where, Elrond had always wondered. Surely not all the way to Balar. The ainur efforts at liberating them never came to anything but inconvenience, they were always plucked out of the waters by worried guardians.

Maedhros always worried they would drown. It was Maglor who exhaustedly explained that, no, the grandsons of Tuor must be beloved by the waters. Ulmo was trying to send them home.

Elros and Elrond had no scope to appreciate either sentiment. They were just tired and wet and scared.

Elrond was tired and wet now. His hands cut open by cold rock, knees scraped, limbs straining, he was angry, he was also as angry at Ulmo as when the Lord of the Tides had stooped before him and his brother and told them of the boon he gave their mother. As his feet hit the mucky sand of low tide and he shoved his sopping hair out of his face, he had the same demand for him.

Could you think of nothing more helpful to do?

“Oi!” Elrond yelled as he strode forward into the sea, “Do you have something to say!”

The sea was massively loud, churning and twisting as it had been doing all morning, the wind whipping it up into a frenzy. Elrond had to fight every step, both against being pulled forward and by being pushed backwards by the tide. And down. The sand was soft and grasping. It seemed like Ulmo had quite a lot to say, and if Elrond was in a more philosophical mood, he’d unplug his ears and listen to what the Lord of Tides’ domain was trying to communicate.

But that was a habit that Elros always rolled his eyes at and called, “So Elvish,” with a stupid smirk and then Elrond would tackle him to the ground and they’d wrestle until one of them had mud forcibly rubbed behind his ears, and-

And those days were gone. Those days were gone without any possibility for recovery and Elrond scarcely comprehended how short they’d been. So long for Elros, so short for him.

Battered and deafened by the sea, Elrond finally screamed at the top of his lungs.

He yelled until the breath ran short in his throat and then he drew in a large gulp of air, and cried out again, tilting his head back. This time, his throat burned when all the air was gone, but now that he’d started, Elrond wasn’t done. No one on Numenor could hear him here. No subjects to draw conclusions, no nieces and nephews to baby him, no Gil-galad so soon to arrive with his soft understanding that didn’t understand anything.

No Elf could understand this. No Man could understand this.

To be separated in fate from the one person who had been consistent throughout your life? Even when you’d both made those choices with eyes wide open and sure, it was… The dissonance could scarcely be comprehended.

So Elrond screamed until his voice was raw.

He let his knees give out and collapsed into the surf. The sand was soft beneath him and ruining his black mourning clothes, but damn, it was the calmest he’d felt since…

When Elrond tilted his head back towards the misting rain, he closed his eyes and was lying in bed with Elros once more. His little brother was wheezing with each breath, so drained and weak he could hardly sit up, but it did not impair their conversation. They were talking about being younger, the wild years of Numenor’s construction, when Elrond would leave the equally unfinished Lindon and they’d roam, alone and together around the lands of Eriador.

“It was Nîn-in-Eilph that I’ve missed in these infirm years. I loved it there. Every step was an adventure,” Elrod said in his creaky voice, and Elrond had smiled.

Lying on his side, face half covered by pillows, holding Elros’s hand, he said, “All of the Bruinen is beautiful. Do you remember that valley we found? I keep meaning to go back there, I keep thinking of it.”

Elros chuckled weakly.

“Only you would find yourself entranced with a patch of land so near troll dens. Oh, I worry about you, Elrond. What shall you do without me, hm? Without Numenor and the wisdom of Men to come running to when you are annoyed with your Elves?”

“And what about you?” Elrond replied softly. “What shall you do once you cross and you’re surrounded by only mortals? Where will Elrond be then and his Elvish wisdom to save you when you are annoyed by Men?”

Elros did not reply to that; Elrond supposed that they were too close to that eternal uncertainty for it to be funny.

He squeezed his brother’s hand.

“Don’t worry about me,” Elrond had whispered. “I’ll be fine. You know me. Comfortable everywhere.”

“And home nowhere,” Elros muttered in reply, squeezing back. He turned away with a slight smile, though, the knowing kind old Men and elder Elves got. “Too brave, too adventurous for your own good. But, no, no… You’ll be fine. I know it in my heart that you’ll find your home one day, Elrond. First, you just have to do everything and talk to everyone!”

“I will taste the world,” Elrond said, smirking.

Elros had chuckled, and started to drift then. Elrond sang for him. His brother napped for the last time, because when he awoke in just two hours, he summoned everyone important to his side and said his final goodbyes. Elros was gone before sundown.

Opening his mouth for the rain and the salty mist, Elrond thought they tasted very bitter. He did not want them, suddenly. He did not feel brave and adventurous; he did not feel like King Elros’s wild Elven brother with hands that could heal any ailment. Elrond felt very like everything he’d ever known was burning at his back and he didn’t want to run from the thing that caused that loss. After all, what did it hurt to embrace that which had destroyed you when there was nothing left behind you?

Not for the first time, Elrond wondered what it would be like to have made a different choice. Would he and Elros have died hand-in-hand as they’d been born hand-in-hand?

But his heart tugged and pulled, and he found himself bitterly wondering instead what it would be like right not if Elros had chosen differently. He would have liked that better. It wasn’t how it was, though.

Nothing was ever how Elrond would have liked it.

Which brought him right back around to the self-pity that had dragged him out to the sea which had stolen so much from him and still taunted. Mother, father, brother, Maglor, all of them stupidly entranced by the ocean water when Elrond thought he’d rather go rot in a river valley. Maybe he should just go lay down in the mud near that troll land and stay there for an age until he was subsumed and made part of the very earth, watching it all pass.

And when he awoke from that most natural slumber, perhaps the grief would be gone. Perhaps he would not mind being alone.

“Bah!” Elrond cried, letting out all his air with his exhalation. He threw himself back into the water, clueless as to what else to do with the storm in his chest. Under the water, Elrond drank and tried to say, Ulmo, if you’re to interfere, turn me into something else and let me fly away.

His lungs ached, his raw throat burned, and it felt good to focus on that pain. Everything was dark and white noise beneath the waves and he was free.

Which was why he was so annoyed when a gentle hand cupped the back of his head and lifted him up.

As he hacked and coughed and wiped at his salty face, Elrond glared miserably at the watery visage of Ulmo, Lord of the Tides. That transparent, saltwater form just raised a coy eyebrow at him, and Elrond spit some of the water from his mouth. It had been some time since he’d seen or spoken to this entity, but he felt no surprise; or awe.

“I knew you must be near,” Elrond muttered petulantly.

“I’m always near,” Ulmo intoned, voice bubbling like a creek, every word a song unto itself.

“Shall I find a desert, then, and see if you appear?”

“Cheeky.”

Elrond managed a strained quirk of his lips and not much else.

Ulmo blinked lazily at him, water flicking off his viscous eyelashes. Such a strange creature, even more timeless and unreadable than the most enlightened Elves. There was something alluring about such infinity to Elrond, but it did not come with reverence. Not for the first time, he was taken with the desire to stick his hands into an Ainur’s fea and dissect what he found there.

“Yet,” Ulmo burbled, “you were cheekier still in the days when we spoke often. Sweet child, sharp tongue. Wide eyes, stern stance. Gentle hands, long sword. You were scared, then. You are scared now.”

And Elrond sighed.

“I suppose so, my lord,” he mumbled, holding onto his ankles and leaning back. He turned his gaze towards the setting sun and pretended to study the clouds.

“Fear is not something to be ashamed of.”

“I know, my lord.”

“Especially when faced with situations we have never known before.”

Elronnd’s eye twitched, and for the fourth time today, his temper got the better of him. He splashed water at Lord Ulmo, dismissing him and his words, and glared.

“Never known before and never again,” he snapped. “I only have one brother, one constant companion to lose. In fact, I am the only one who has ever known such a thing, and with a little luck, am likely to be the only one ever. So, yes, I am scared and cheeky in the face of such a thing. It is always I who is asked by Iluvatar to suffer strange and singular pains, so I hope you’ll forgive me for not acting with perfect grace.”

“The Valar have lost siblings to unknown and diverged fates,” Ulmo said and Elrond’s eyes went massive as shock and fury battled within him.

“Do not compare my brother to Morgoth,” he hissed quietly and the water around him grew unnaturally still, only the slightest ripple of tension emerging in a circle around him.

Ulmo did not look phased.

He merely said, “I meant myself, truly.”

Elrond floundered. Anger and indignation had been building, and just as suddenly, they fled from him, the waves moving once more. Lukewarm sea water splashed up his back, and Ellrond merely stared, stunned and lost. Ulmo, thankfully, explained.

“Myself, and the others whom you know. Our Manwe, our Varda, our Yavanna, so on. And our Melkor. Those of us who came to shape Arda left kin behind and we knew when we did that we would never return. Tulkas feels this choice most keenly. We still miss those left behind as I’m sure they miss us, but it was a choice made with open eyes. To leave, to stay. It was what was desired, needed by each individual. Sometimes we must leave loved ones behind when our paths diverge too heavily, and that is as natural a thing as… Well, as my rivers diverging never to meet again! Some, most, rather, come back together in the ocean, but some lonely few do not. Only the breaking of the world will reunite us.”

Ulmo tilted his head, hair dipping and dripping back into the sea.

“Does that make sense?”

“Yes,” Elrond whispered, looking away. He was suddenly embarrassed by his outburst, by his… lack of perspective. Yes, of course the Valar might be the only of Iluvatar’s children who understood him. How strange to not be alone in this pain. How… bitter. “Yes, I see now. I’m sorry.”

Slowly and gently, a water-light touch lifted his chin. Ulmo had no eyes, not in the traditional sense. In the liquid facsimile of a face, there were pockets of light where one's eyeballs typically were. They were infinitely deep and Elrond wished for such a perspective. He wished he could see instead of being bound by his hroa.

“Do not apologize, like a child caught with dirty hands. You do suffer uniquely. But even with Elros’s equally unique existence diverged beyond you, you are not alone.”

“I do know that,” Elrond said, sadness gripping him. He did, he did know he was not alone.

For all he dreaded having to see and feel Gil-galad’s grief and sympathy, Elrond knew he would embrace his almost, nearly brother like the world was ending all over again as soon as he saw him. He knew that Galadriel would be just as annoyed with the spectacle of this funeral and let him curse the world without judgement and Celeborn would hold him up without any fuss or trouble, easy to let love him. Celebrimbor would never flinch when Elrond wanted to talk about the strange and politically-difficult childhood he shared with his brother, and would let him cry bitterly for who wasn’t here. There was Thranduil and the other children of the War of the Wrath who would pass him a bottle, no questions asked, and not treat him as fragile.

But being alone and being alone were two different things. Elrond and Elros, Elros and Elrond… Who was just ‘Elrond’? He didn’t know. He was scared to find out.

As soon as Elrond’s face crumbled, Ulmo’s giant, watery hand began to caress his head and for the twelve-billionth time, he cried.

“When will it end?” Elrond blubbered around his tears. “When will it stop feeling like the right choice was to stay together?”

“Oh, child, never. You need be more concerned with if you ever start to feel like the right choice was for you to have made for Men. I don’t think you feel that way. I think you wish you could have had it both ways. That you could have had your choice and your brother. But you would have never wished miserable immortality on him just as he would have never wished miserable mortality on you. It is a tragedy; there were no perfect ends.”

“It hurts so much,” he wailed. His eyes and the sky and Ulmo were all so wet and blurry that it was hard to distinguish. The only thing clear was the star of Earendil rising in the sky. “We all keep having to make these choices and it hurts so much!”

“I know, child. The waters never stop moving, and it is cruel and it is glorious. My heart is filled with sorrow for you, but also hope.”

Elrond was hiccuping around his tears, shaking his head. Hope, hope, hope, what was it Maedhros said about hope? That it was for lovers and martyrs. Elrond did not want to be a martyr, but he did know love. He just… was so tired of that love bringing him pain. Of those he loved all but fleeing from him.

His love for Elros had not gone with his brother’s soul to the place of the Men. It was still here and it was heavy. Right now, Elrond had little hope of that love not drowning him.

“I’m scared,” he rasped, wiping at his eyes. “I knew it was coming, but I don’t know how to live with this eternity I’ve chosen without him. I’ve never done… anything without him.”

Ulmo made a noise like a rumbling waterfall, that washed away his fears as easily as cleaning up silt.

“Nonsense,” he rumbled. “You have made a home of Lindon without him. You have forged friendships without him. Traveled west of the Misty Mountains without him. Written treatises on the nature of the world without him. What you have not done is lived your life without him in your heart. You never will; I still remember our kin beyond the edge of Arda and you will always remember your brother. But what you will find is that the place in your heart he is held in will grow fonder and gentler in time. Lighter. Every weight feels heavier at low-tide.”

“Low-tide?” Elrond snorted, wetly and then had to cough around his tight throat.

“Yes,” Ulmo said, patting his head with one hand that just further drenched his hair while the other gestured at the drawn out tide around them. “Low-tide. The currents of life and time wash us up and pull us out, leaving us stranded for a time. But as long as we choose to keep trudging forward, the waters always come back.”

Elrond briefly considered telling Ulmo that this metaphor felt a little stretched, but… no. Woe betide him to reject poetry in times of pain. It was Elros who had preferred prose.

“But we still come back to the main issue,” Elrond said. “I don’t know how to swim alone.”

Ulmo shook his head at him, but did not scold. He merely said, “You don’t need to know how, you have done so all along. But if you are so frightened, think of it this way. Like a duckling, it will come naturally to you, after a time. You just need to let life carry you, follow the flows of water down the diverging paths according to what feels strongest, and you’ll get there. I know you, Elrond. The never-ending chase inspires you. You are scared now because you have found yourself in one of life’s many low-tides. You are stuck. But the waters will pick back up again, in time, and take you along. Be scared. But know that you will keep going.”

“I guess that’s what I signed up for,” Elrond laughed wryly, “to keep going and going and going. My Eru. I’m already tired.”

“You’ve hardly begun, child. There are many more tired days ahead of you.”

“So the Men keep telling me when they call me child,” Elrond said, glaring at Lord Ulmo once more, but this time it was with a slight smile on his lips.

“You are a child,” Ulmo sang, and he was already melting back into the waters. “Enjoy your wandering feet, Elrond. Let them take you where they need you to go. Search for all the answers your heart and mind taunt you to find, and then enjoy the days where you might call others ‘child’.”

Elrond, small and alone, didn’t think he’d ever know enough to call another ‘child’ so surely. But he… he… When he thought of following Elros beyond, he balked, because he wanted to learn. There was so much more to see and understand.

He was still sad that he did not have Elros to share it with.

On leaden limbs, Elrond stood. He could not sit in the sand forever. He was sure that his absence had already been noticed and Vardamir had sent people looking for him. Numenor loomed so largely before him, though. Elrond didn’t want to climb up its vaulted walls.

As he was considering the value of calling for help, he felt the water start to rise and come back in; and, more importantly, he felt the waters start to tug his legs to the left.

A boon, a melodic voice whispered in his ear, and Elrond decided that, well, he wasn’t a child anymore. He would follow the waters of Ulmo where they would take him today. He did not have anyone else to go running scared to, after all.

The tides carried him around the edge of Numenor’s slopping cliffs where the oldest parts of the grand city were built. They dipped lower as Elrond trudged forward until they gave way to grassy beach. Still, the waters guided him onward. As his legs started to ache and his feet grew sore, this strange path towards an unknown destination did not feel like a boon.

The night was growing closer, the star of Earendil bright but far away. Elrond walked, confused, in the dark until a familiar song greeted him from a distance. He moved faster, after he heard that, until a strange silhouette emerged before him, and Elros’s whispers about a shadow that visited him in the night made sense.

Yes, there was someone who knew and mounted Elros the peredhil and not Elros the king.

Out from Ulmo’s waters, Elrond ran for Maglor. When the music stopped, he was greeted with open arms. He breathed in harp polish, brine, and seared flesh, and felt at peace for the first time since Elros’s hand slipped from his.

Someone had come back to Elrond.

#i think this ends a little fast I'm sorry about that!#I enjoy writing young and angry and unsure Elrond#he was not always perfect#he earned his wisdom the hard way!#elrond#ulmo#elros#the silmarillion#tolkien#tribble post#fanfic

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'd love to hear about Elros and Elrond Timeswap and Old Fires Burn Out! — @emyn-arnens

[from this WIP ask game!]

Thank you for the ask @emyn-arnens , the one for Old Fires Burn out I already answered here!

Elrond and Elros Timeswap my beloved aka the fic where I give Elrond a bit of an existential crisis and let Elros have some quality family time with his sister-in-law, nephews and niece.

The basic idea of this fic actually came to me because I was one evening very sad about the fact that Elros never got to meet Elrond’s kids and Elrond’s kids never got to meet their uncle and I wanted to fix that.

Elros is from late-ish into his reign, I imagine he already has some visible signs of aging like some gray hair he is very conscious about; while Elrond is from around the time where Arwen is still in the elvish equivalent of pre-teenagehood and a bit of a menace to deal with. Though he’s definitely from before Celebrian gets captured! And yeah for some unknown reason the two of them swap places for a bit.

Elrond’s existential crisis comes from the fact that a) he, for some reason, is now in the past, b) his brother is fucking missing, c) his dead nephews, niece and sister-in-law are alive again(!) and d) he isn't so sure how he’ll deal with the younger version of himself who is scheduled to arrive in like three days… and also e) Manwendil had the brilliant idea that Elrond should be playing Elros’s part as king for the foreseeable future because someone has to and it's definitely not going to be Vardamir.

Elros meanwhile falls from a tree during his daily midday nap in the gardens and suddenly finds himself in the middle of a valley that he doesn’t know and starts wandering around looking for people. He runs into his old friend Gildor, who looks at him like he’s a ghost, meets Glorfindel (isn’t he supposed to be dead??) and finally learns that his brother apparently built an elvish city and got married(!) without telling him about it. It takes him a moment to figure out he might not actually be in time anymore, because everyone else is a little bit too preoccupied with the fact that their lord's dead twin brother just showed up (while their lord is missing!!) and isn’t telling him anything. Nobody expects Elros to play Elrond’s part because all of Rivendell already knows what happens and so he’s free to spend time with Celebrian and the kiddos. Though there is this meeting with the White Council coming up… maybe the Wizards will know what to do? (Spoiler: Saruman and Gandalf know nothin’)

I actually have one chapter and a half already written! Maybe there will be more maybe I'll continue spinning this around in my brain like a döner kebab for eternity.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ranking the families of Arda

Disclaimer: Since there is so much overlap between many of these prominent families I will try to go by the paternal lines, as that usually determines who your counted among with a notable exception being the descendants of Luthien.

Second disclaimer: I won't be including the House of Finwe but rather count his sons's families separately because it makes it easier and because I don't like him.

1. House of Feanor

Take one scroll through my page and you'll immediately know I'm a Feanorian kinnie.

Maglor, Maedhros, and Caranthir are my favorites but I love all these horrible men and will wholeheartedly defend them but C&C might be exceptions.

Still love Celegorm as a character though given how interesting he is. He has the background of a Disney princess since he can talk to animals and had somewhat of fairy godfather yet his fall from grace is down a deeper darker hole than all his brothers and maybe even his father.

2. Mirkwood Royals

Starting off, Oropher himself is rather interesting. Little of his life as a noble in Doriath but after it's fall is where his story truly seems to start.

Now, I have to admit that as someone who descends from colonized people, I do not support colonization in the slightest but Oropher lands on the better end of colonizers. He and his Sindarin people seem to have assimilated into Silvan culture instead of forcing his own upon them. Also, he seems to have been a decent king given he did his best to avoid Sauron but eventually died fighting with the last alliance.

Where to begin with Thranduil. Let me just say he is an iconic character filled with so much charisma and personality. I adore him.

And Legolas, he has a special place in my heart. I loved his vibe from the moment we met him in LoTR. Legolas also proved to me that you don't need to have a tragic backstory(Shut up hobbit movies, his mom could be alive!) or be morally gray to be an enjoyable character.

3. Baggins Family

I love Bilbo. I love Frodo.

I have nothing more to say.

4. House of Finarfin

Finarfin himself, I first underestimated as a character. In comparison to his influential and powerful elder brothers, he seemed so dull. However, the more I read into him, the more appreciation I gained for his character. I also respect that Finarfin seemed to assimilate into his wife's culture and it wasn't only the other way around.

Now, his and Earwen's descendants. I love them all.

5. House of Elros

I suppose all of them are technically members of the House of Fingolfin but since they're humans, I will count them separately.

This family has so many members and not all of them were written about but the ones that were fleshed out were super cool. Elros himself is super interesting given he chose mortality despite everyone he knew and loved at that point was immortal. Vardamir, Elros's son and successor was a cool scholarly dude, Aldarion was literally human Earendil and knew all the cool elf dudes and knew about the threat of Sauron, his daughter Ancalime was an influential badass queen, and finally, Pharazon was a pretty good villain as far as villains go.

5.5. Feanturi + Nienna

I don't know if they should be allowed on this list but I love everything about these three Valar siblings.

6. House of Beor

I care about three characters from the House of Beor and their names are Andreth, Morwen, and Erendis.

I guess I really love long suffering women huh. In all seriousness, I actually think these characters are super interesting and in some cases relatable.

I don't care for the guys though. Before you attack me, let me say I don't hate Beren and think he's a pretty good dude but I just never really connected to his character.

7. House of Fingolfin

Fingon and Aredhel own my heart, I think they're amazing characters. Also, they're both fashion icons.

I love Earendil and his twin boys.

Turgon is an interesting character although he's not one of my faves. Idril's cool I guess.

Maeglin sucks.

8. House of Haleth

I love Haleth and Hurin, and I think Turin is an interesting character.

Everyone else, I don't have an opinion on.

9. Telerin Royal Family

I wholeheartedly love two, maybe four characters from this family. Cirdan, Elwing, Elrond, and Elros.

The twins are already spoken for so let me discuss their mom. Despite being a Feanorian sympathizer, I cannot help but love Elwing. She's an incredibly complex character and I love that about her. I know the fandom characterizes Elwing and Earendil as codependant and while that's probably true to some degree, it doesn't give Elwing enough credit. She didn't sacrifice a possibility of eternal happiness with her elven family for Earendil and she ruled over the Havens of Sirion quite possibly alone while Earendil was off doing hero business.

Cirdan is another awesome underrated character imo. His selflessness is inspiring.

I also want to say I like Celeborn and for some reason I have a soft spot for Olwe but I don't care that much about them, sorry.

Characters from this family I truly don't like Thingol and Dior, and everyone else isn't fleshed out enough for me to have an opinion on.

10. House of Durin

And I finally get to talk about some Dwarves!

I liked Thorin. He made the Hobbit fun and interesting.

I loved Gimli! He's a boss and totally deserved to go to Valinor with his bff.

11. Stewards of Gondor

Boromir and Faramir are awesome.

12. House of Eorl

I love Eowyn with my entire heart. Eomer pretty cool too.

13. Vanyarin Royal Family

Ingwe is low key boring, I'm sorry.

Ingwion is there I guess and close to Finarfin presumably given he fought in the war of wrath.

I like Indis but I don't love her. If her descendants were included this fam would be a lot higher.

#lotr#the lord of the rings#the silmarillion#jrr tolkien#feanor#feanorians#maglor#maedhros#fingolfin#finweans#elros#elrond#galadriel#thranduil#legolas#gimli#thorin oakenshield#boromir#faramir#eowyn#bilbo baggins#frodo baggins

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

WIP (meme, sort of)

I got tagged by @naryaflame in a WIP sentence meme. I haven’t got a WIP sentence, really, so, as so often, I’m going to do the meme wrong...

Here is an untitled drabble that is complete in itself, but seems to want to become a double drabble:

On some days, Vardamir feels older than his father. It is not just a physical thing. Vardamir early on was someone who wishes to preserve, older than his years compared even to other Edain. Maybe the elvish strain came out in him that way. The desire to gather traditional lore grew out of that, although he also is convinced that it is necessary and useful to Numenor.

Elros, even though the loss of Vardamir’s mother hit him hard, has weathered that change, on some days seems as young as his own grandson—quite unlike Vardamir, still every inch a king.

I’m not going to tag one hundred people!

Feel free to post about your WIPs obviously.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

By What Right

read it on the AO3 at https://ift.tt/7pihdya

by KayleeArafinwiel

Sixteen-year-old Prince Amandil, son of the first Crown Prince of Numenor, gets on his tutor's bad side.

His tutor, Lord Manwendil, also happens to be his uncle.

The experience does not go well for him. Or does it?

Words: 1257, Chapters: 1/1, Language: English

Series: Part 24 of Spanktember 2022

Fandoms: The Silmarillion and other histories of Middle-Earth - J. R. R. Tolkien, TOLKIEN J. R. R. - Works & Related Fandoms

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings

Categories: F/M, Gen

Characters: Tar-Amandil, Tar-Amandil's Wife, Manwendil (Tolkien), Vardilmë (Tolkien), Miriel (Original Numenorean Character), Elros Tar-Minyatur, Elros Tar-Minyatur's Wife, Vardamir (Tolkien)

Relationships: Tar-Amandil/Tar-Amandil's Wife

Additional Tags: Spanktember 2022, Caning, Teenage Rebellion, Teenage Drama, How They Met, Amandil was refusing to find himself a nice girl, so Uncle Manwendil arranged matters to suit himself, it helped that Amandil ran his mouth off however, though Amandil's backside doesn't think so, Lèse-majesté, Start of Relationship, Hurt/Comfort

read it on the AO3 at https://ift.tt/7pihdya

0 notes

Text

I love thinking about how the great stories of Middle-Earth are perceived by valinorean elves from such a unique angle. These elves aren't simply outside of the stories, they are on the other side of the stories. Their birthplace is where most of the great songs end.

How must it feel, living a life that is so sheltered and so, so, so long? Everything is sacred: a beloved person's heart broke right next to this random pebble. Everything is mundane: a beloved person's heart broke next to every pebble here, at least once. This is just a seashore.

The story of Númenor is significant only for the explanation it offers; ah yes, that's why Nope Mountain isn't a grazing area.

Or, my favourite example:

Valinorean elves will hear a song for the first time and associate the iconic "embracing scene" with a weekly occurring celestial phenomenon. The cathartic turning point of the Voyage of Earendil? That's the view from telerin windows...

#your favourite line of poetry hits vardamir smith's eyes at 5:20 he should remember to shut the curtain next time#ngl this is very catholic of tolkien#silmarillion meta#kind of? i forgot how i usually tag these#earendil#oh that's it!#the liquid opus#i wanted to write amplexus scene then remembered that it's also used for frog intercöurse so i... didn't

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

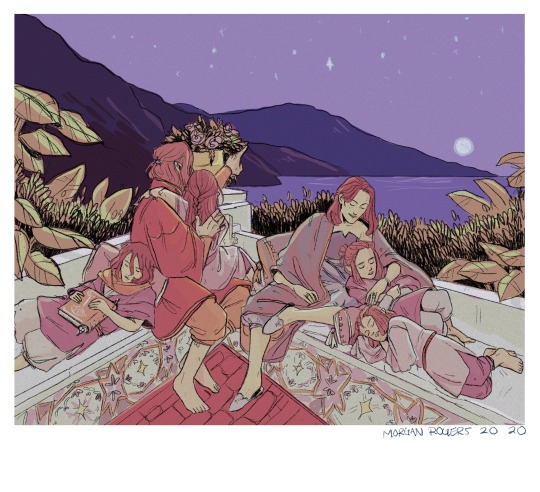

Day 1- Elros and his family

I know it’s last minute but I just found out about @numenorweek!

#I posted two versions of this cause I didn’t know what colors I liked more .-.#I’m such a fake fan lol#I have neglected numenor#I just saw that this week is numenor week so I thought I’d participate to the best of my ability!#sorry I’m late with this one#it’s Elros and his family enjoying a night under the stars#timdomiel stays awake all night to spend time with her grandpa#:)#elros tar minyatur#Elros wife#poor thing has no name#vardamir nolimon#tindomiel#manwendil#atanalcar#I headcannon Elros’ youngest sons are twins#just feels right#my artwork#my art#silmart#second age#numenor week#numenorweek2020#it’s still technically Monday where I am so I’m good

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

@halfelvenweek, day 7 - Vardamir

He was born in the year 61 of the Second Age and died in 471. He was called Nólimon for his chief love was for ancient lore, which he gathered from Elves and Men. Upon the departure of Elros, being then 381 years of age, he did not ascend the throne, but gave the sceptre to his son. He is nonetheless accounted the second of the Kings, and is deemed to have reigned one year. It remained the custom thereafter until the days of Tar-Atanamir that the King should yield the sceptre to his successor before he died; and the Kings died of free will while yet in vigour of mind.

#this was supposed to be for day three but i am a dumbass#convinced to post this by wigilda who is now suffering as my official designer to help with colours#so much about me making a post for every day of half-elven week#rip creativity#halfelvenweek#vardamir#tolkien#wigilda appreciation agenda because i am making her suffer

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tolkien had that concept of Erestor being a half-elven relation of Elrond early on, so I see people speculate on him being Elured or Elurin, because they are the only known misplaced Peredhel.

But another abandoned concept was Elros’s children having the choice of the Peredhel. And his eldest abdicates immediately to continue his work as a scholar. And Rivendell is a place of learning… I’m just saying Erestor could be Elrond’s nephew. Any of them, but I kind of like it being Vardamir Nolimon because of his scholarly bent and abdication.

Also, can we talk about how three generations of this family in a row threw twin Peredhel boys as their first children? It’s weird that that is so prevalent in the line of Luthien, but she herself did not have twins.

Unless she did.

Dior Eluchil arrives at court with a Silmaril as his proof of right to the throne, and a name that means “successor heir-of-Elu.” He then immediately marries a kinswoman of Thingol. It might not be a stretch to assume that they were a little anxious to make his claim on the throne iron-clad, and thus the decision for his twin brother to not show up until he was well established becomes an option. Aaaand then the kinslaying happened and him showing up at all became kinda impossible.

Anyways, shout out to Erestor’s backstory, the under-appreciated cousin of Gil-Galad’s parentage.

#tolkien#the silmarillion#lotr#jirt#silmarillion#silm#elrond#erestor#elros#peredhel#luthien#dior#gil-Galad#elured and elurin#vardamir nolimion#jrr tolkien#Dior Eluchil#the great missing twin conspiracy

428 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any tar-miriel headcanons? [or tindomiel headcanons?]

When Elros tells stories to his children, his sons beg for tales of Fingolfin's glorious charge unto Angband, for Earendil's desperate foray into mist and salvation, for Tuor's raging defence of wife and son atop Gondolin's battlements. His daughter does not contradict them, nor does she fuss to hear it: her eyes glow just as bright as Vardamir, just as fervent.

But when she asks for tales, she asks to hear of Idril's great secret tunnel, hidden even from her beloved father. Of Lalwen's defiance, blazing in the salt-flats of Sirion, of Findis' steadfast piety and of Findis' grandmother, passed long before Elros' foster-father could have ever told him tales, passed long before the first elves ever reached Aman: Intyale the Bright-Speared, who snuck into Morgoth's lair before ever he established himself in Angband, who stole away her sister with nothing but clenched fists and a knife-sharp spear.

Perhaps that should have been Elros' first warning.

...

(The second warning came when she chose a craft, in the fashion of the Noldor.

Vardamir had not chosen a craft--not officially, at least, for all that he barely ever threw off the scholar robes Elros and Eresse had gifted him--but Tindomiel made a song and dance of it, insisted, until Elros gave in out of exasperation.

Tindomiel chose prayer.

A safe choice, people seemed to feel, and relaxed. Grandeur in the name of the Valar? She is following the footsteps of her mother.

But that was not the warning. The warning, Elros did not realize, had been in the song and in the dance and in the blazing soaring masquerade of it all.)

...

Tindomiel is the quiet one of his children: quiet and calm, never quite so fierce as Manwendil or as cheerful as Atanalcar or as quick to speak as Vardamir, for all that she is most similar to him. Both she and Vardamir are reserved, in fact; so much that Elros and Eresse had found themselves struggling with Manwendil’s blazing spirit as a youth, so heavily contrasted against his elder siblings.

...

Three thousand and thirty-two years in the future, a boy finds an embossed book tucked behind the dark shelves of Numenor’s library. He does not spend much time in the library--he finds joy in the open fields of war, feet rooted on the rolling deck of a seafaring boat--but his tutors have impressed upon him the need to understand history for military ventures.

He is fourteen years old. He is a curious fourteen years of age.

The book--long abandoned--opens before him like sunlight. The first sentence alone takes him a week to decipher from the chicken-scratch and the old script, but nobody has ever called him unmotivated.

I am the daughter of kings and gods, he reads. I know my inheritance.

And below it, in the glorious swooping signature of the first and highest princess of Numenor: Tindomiel Anyale Alfirinie.

...

Tindomiel inherits nothing. Vardamir has a kingdom; Manwendil his position in Numenor’s army; Atanalcar his beaches and fertile coastlands from their mother. Tindomiel, alone, has nothing.

(She asks for nothing.)

(She refuses what is given, and takes nothing as well.)

There is no room for land or titles or positions where Tindomiel wishes to go.

...

She spends many decades in the temples. They are beautiful places, made of song and light; and there are dozens of them, made precisely to be a home to those that wish to worship in one manner or another. Tindomiel wanders through them--she spends no more than a month in each.

One week to establish herself. Two weeks to learn their philosophy. One last week to practice that philosophy.

And leave, and repeat.

She takes them all in to herself, swallows the meditation and the approach and the practices. Bares herself, soul and more, before the stinging scouring gazes. Swallows the bitter draughts; swims in the strong incense. Kneels on the cold stone. Sings in the drenching monsoons. Wanders the darkness, accepts the lashes, follows the fasts.

Finds what works for her.

And gets to work.

...

There is an old story that Luthien was told by her mother, amid the star-shining eaves of Beleriand-unmarred.

An elf-maid falls in love with her sister’s lover, and wishes to die of the agony: so she reaches with all her fea for what can never be, and in her straining gasping throes she shatters the walls of the world, and is never seen again.

A warrior of the Ainur known for the depth of his loyalty and the swiftness of his blade is forced to choose between saving his oathsworn company or holding to his vows to his lord and god: so he reaches with all his fea to escape what he cannot leave, and in his straining gasping throes he shatters the walls of the world, and is never seen again.

An abandoned child of slaughtered parents wails and wails and wails for comfort that will never come: and so she reaches with all of her fea for warmth that she remembers so well, and in her straining gasping throes she shatters the walls of the world, and is never seen again.

A swooping hand, wrapping around a little girl’s dark (night-dark, nightingale-dark) hair--and Melian’s voice, soothing even in a horror story: This is what happens when the world is too cold and too cruel. The impossible becomes possible, in situations of impossible brutality.

When pushed too hard, little one, people break the world. We can offer them so little after they have surrendered to that fate: we can only remember. And in remembering, we respect them. We cherish them. We honor them, and we name them gods.

...

(Who do the Valar worship?)

...

None of Melian’s stories mention humans. No human has ever broken the walls of the world. No human, none of the thralls of Angband, none of the captives of Sauron, none of the warriors of the War of Wrath--none of them have ever become a god.

But Tindomiel is the daughter of queens and kings: dragonslayers and lightbringers. Her ancestry is as grand as ever her father and brothers. And she has been raised on stories of wolves and dying, desperate defiance and women, forgotten, abandoned, lost.

Idril, who sailed to the west and was never seen again. Finduilas, pinned to a tree, screaming until her lungs would not draw more breath. Her own mother, who sailed west to Numenor with her bare hands. Nimloth, dead with two Feanorians’ blood on her sword and her lance held tight in her hands. Luthien, who danced at the death and won life for herself and her lover. Melian, who held fast before Morgoth himself--who Morgoth dared not challenge upon her own lands. Lalwen, disappeared after the Third Kinslaying. Findis, silent by choice and chance. Indis, quiet and hidden in the cold golden halls of her uncle’s city. Intyale, defiant and triumphant even at the end.

And Elwing, who fell rather than surrender, and flew rather than die.

Elwing. Who was human and Maia and elf. Who loved life so well she won immortality right out of Namo’s stingy fingers.

...

Elwing is her grandmother, and Tindomiel’s dreams are as grand as any king’s.

...

The boy asks what his tutors know of Tar-Minyatur’s eldest daughter, and hears--quiet girl, dutiful child; no children; pious and dedicated; unwedded; wedded to her craft; dead of unknown causes in S.A. 442--and tries to reconcile the description with the brash, prideful woman of the journal.

Then he remembers that Elros Tar-Minyatur died in 442 as well, and a chill goes down his spine.

...

First, she gives up food. Then she gives up water. Then she measures her very air: not too deep, not too much.

A human’s body is not so durable as an elf’s, but it is durable enough for this.

...

Near enough to see, Tindomiel has written, on the last filled page of the journal. Near enough to see, but never touch. Near enough to hope but never reach. Well: I shall reach higher than any of them!

The boy touches the words with the tips of his fingers. Swallows.

There is no more to this story here, but he has--a feeling. A knowledge inside him. A seed, steadily growing into a wide-branched oak. And he is old enough, now, to take the horse and ride to Romenna without anyone’s permission.

At the bay, he wanders the seaside. It has been more than three thousand years. Surely--surely the coast would have--changed--

But then he sees the curve of the beach, shallow and cut of ragged stone, echoing the same sketch that Tindomiel had made in the journal, and excitement flares in his belly. The boy approaches. Strips off his boots and cuffs his trousers, ignores the way the stones cut into his feet and the salt of the sea stings the wounds.

Stands there, balanced, on two flat stones. Then he lifts his hands to the sun, and folds the sole of his foot against the inside of his thigh: trusting in the sea to support him.

Tindomiel had studied for centuries to find what worked for her. He does not have those same centuries, but he is not trying to break the walls of the world: he is only trying to see into the past. And for that, all he needs is--

“Anyale Alfirinie,” he calls out, into the spiraling light of earliest morning.

Tindomiel, named for the morning star, called forth on the eastern beach of Numenor, with the epesse of her choosing.

The dawnlight spills around him like liquid gold.

And with the light comes Tindomiel.

...

“Tindomiel!” bellows a voice.

Startled, she jerks out of her reverie. Even that is smooth at this point: there is little energy left in her limbs for such petty things as surprise or shock. When Tindomiel looks over her shoulder, her father stands on the beach, and beside him is Vardamir.

“Father,” she says. Her voice rings of bells and samite: lent some eldritch strength from her prayer. “Why are you here?”

“To stop you from killing yourself,” he snarls, and steps into the water.

“You cannot stop me,” says Tindomiel. “Would you stop Vardamir from ruling? Atanalcar from governing? It runs in their blood as sure as the sun rises in the glorious east.”

“You mean to--”

“Yes.”

“It is not worth it,” he whispers. “Immortality is not yours to reach for.”

“It was yours,” says Tindomiel levelly. “But you chose otherwise.”

“And you hate me for it?”

“I have no room in me for hate,” she tells him. “Only the knowledge that I would have taken another path in your shoes. But I have only ever had one path, is that not true?”

“How can you say that?” he asks, wretched.

“Because I was not given anything but your blood,” Tindomiel says pityingly. “The only inheritance I have ever had was your blood. Elwing’s blood, and Luthien’s, and Intyale’s. And so with blood as my inheritance was my path written before me: to do the impossible, and to do it well.”

“You could have done anything,” says Vardamir. “But you chose to do this.”

“To be remembered,” she replies, “I would do much.”

“You will not be remembered for this,” says Vardamir. “Not ever. Do you understand? You will be erased. Everything that you have done--everything that you have achieved--it will be gone. This is too dangerous to keep alive. Even if you do this, Tinde--”

“--if you erase this,” she says, “you go against the oldest teachings of the Valar.”

“And if you continue this, you break Eru’s laws!”

“I have gone too far to choose otherwise,” says Tindomiel, and her eyes are glowing from the light of the dawn, gold and golder, and her hands rise, sweeping upwards like the blades of a knife slicing through the skin of the world, and the world splits apart with an indescribable noise. “Choose,” she says, and her voice is a glory of music now, so loud that Vardamir hunches over and Elros, sways, paling. “Your sister, your daughter--or your kingdom.”

The gold brightens until it blinds, and when it fades, there is nothing left: not Tindomiel, not Vardamir, not Elros. Just a boy, staring, starry-eyed, and silent.

...

Choose, Tindomiel had said, because she has laid out the contradictions of the Valar, because she has dedicated her life to this: for now her father must choose between following the Valar’s teachings to honor the daughter who has broken the walls of the world, and ignoring the Valar’s teachings to erase his daughter’s accomplishments and hide the dangerous implications of her accomplishments.

For Numenor is built on the knowledge that the Second-born cannot gain immortality. They can come close. They can come within sight of it.

But they cannot ever touch.

And now--

And now--

...