#norse poetry

Text

The Edda has goofy sayings and terms, it happens, it's what you get with archaic poetry metaphor, but one of the funniest has to be: calling someone's heart a "hostility acorn" lmao

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stanza from an ancient poem that instantly reminded me of @strange-aeons

"Óthin's wife on earth's ship rows,

Lusting after love,

'Twill be late, ere that she lowers her sails,

Which are fostered by fleshly lusts."

#Sólarlióth#ancient poetry#norse poetry#that weird period of semi-Christianized Scandinavia#strange aeons#westboro baptist church#ABSTAIN FROM FLESHLY LUSTS#fleshly lusts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scandinavia - Old Norse Poetry - Structure and advice on writing imitations

(Some of this will be copy-pasted from my previous post on Old Norse literature and oral tradition)

OLD NORSE POETIC FORMS

Old Norse poetry utilizes a modified form of alliterative verse. In simpler terms, the metrical structure is not necessarily based on the last syllables of a line or phrase rhyming...

Ex: (lines from William Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis) “And so in spite of death thou dost survive / In that thy likeness still is left alive”

... the structure relies on the repetition of multiple initial consonants in a line or phrase.

Ex: (from the Hávamál of the Codex Regius) Deyr fé // deyja frændr

SKALDIC POETRY

Primarily documented in sagas, skaldic poetry is usually about history, particularly the celebrated actions of kings, jarls, and some heroes. It typically includes little dialogue and recounted battles in dialogue. It has more complex styles, especially using dróttkvætt and many kennings.

DRÓTTKVÆTT (“courtly metre”)

- Adds internal rhymes and assonance (repetition of both consonants AND vowels) beyond the normal alliterative verse

- The stanza had 8 lines, each line usually having 3 lifts (heavily stressed syllables) and almost always 6 syllables

- The stress patterns tends to be trochaic (stressed, unstressed), with at least the last 2 syllables of a line being a trochee (usually...)

- In odd-numbered lines (first line, third line, etc.): 2 of the stressed syllables alliterate with one another; two of the stressed syllables share partial rhyme of consonants with dissimilar vowels (ex: hat and bet; touching and orchard)

- In even-numbered lines (second line, fourth line, etc.): the first stressed syllable must alliterate with the alliterative stressed syllables of the previous line (an odd-numbered line); two of the stressed syllables rhyme (ex: hat and cat; torching and orchard)

These requirements are SO difficult that oftentimes poets would mash together two separate lines of writing in order to meet the structure. It’s really hard to explain, so read the wikipedia link here for more info.

KENNINGS

Kennings are figures of speech strongly associated with Old Norse-Icelandic and Old English poetry. It is a “type of circumlocution, a compound employs figurative language in place of a more concrete single-word noun” (source).

Now, when I first read that, I had zero clue what the hell that meant. But this is my current understanding: a poetic device where you dance around using a single noun by describing it with other words. It is similar to the poetic device of parallelism.

- “bane of wood” = fire (Old Norse kenning)

- “sleep of the sword” = death (Old English kenning)

- Drahtesel = “wire-donkey” = bicycle (modern German kenning)

- Stubentiger = “parlour-tiger” = house cat (modern German kenning)

- Genesis 49:11 “blood of grapes” = wine

- Job 15:14 “born of woman” = man

A beautiful resource for translated kennings is this article here from the HuffPost’s Harold Anthony Lloyd.

SIMPLE KENNINGS

Simple kennings would be used in both Eddic and Skaldic poetry.

The usual forms are a genitive phrase (ex: the wave’s horse = ship) or a compound word (sea-steed = ship). There is usually a base-word and a determinant.

The determinant may be a noun used uninflected as the first element in a compound word, with the base-word being the second element of the compound word.

OR the determinant may be a noun in the genitive case placed before or after the base-word, either directly or separated from the base-word by intervening words. The base-words in the above examples are “horse” and “steed”, while the determinants are “waves” and “sea”.

The unstated noun which the kenning refers to is called its “referent”, in the example a bit above: ship.

COMPLEX KENNINGS

More complex kennings are really only used in skaldic poetry.

In these, the determinant and sometimes the base-word are themselves made up of kennings. A matryoshka doll of kennings, if you will.

Ex: “feeder of war-gull (bird)” = “feeder of raven” = “warrior” (referring to how warriors kill people and leave their corpses for birds to eat)

The longest kenning in Skaldic poetry belongs to Þórðr Sjáreksson’s Hafgerðinga where he writes “fire-brandisher of blizzard of ogress of protection-moon of steed of boat-shed”, which means “warrior” (source).

EDDIC POETRY

Eddic poetry is usually about mythology, ethics, and heroes, and is narrative (where both the narrator and the characters are speaking). They use simpler structures, like fornyrðislag, ljóðaháttr, and málaháttr, and use kennings more sparingly.

FORNYRÐISLAG (”old story metre”)

- Each line tends to be a whole phrase or sentence (or end-stopped), where a sentence won’t “run over” and onto the next line (or enjambment).

Ex: End-stopped, from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet “A glooming peace this morning with it brings. / The sun for sorrow will not show his head.”

Ex: Enjambed, from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land “ Winter kept us warm, covering / Earth in forgetful snow, feeding / A little life with dried tubers.”

- Each verse is split into 2 to 8 (or more) stanzas.

Ex: from Waking of Angantyr (structure provided by wikipedia)

- There are 2 lifts per half line, usually with two or three unstressed syllables. At least 2 (but usually 3) lifts will alliterate, always including the main stave (the first life of the second half-line). This means there are usually between 4 and 5 syllables per half line, and therefore between 8 and 10 syllables per full line (but it can vary).

MÁLAHÁTTR (“conversational style”)

- Similar to fornyrðislag, but there are more syllables in a line.

- It adds an unstressed syllable to each half-line, making the typical 2-3 per half-line and 4-6 per line into 3-4 per half-line and upwards of 6 unstressed syllables per line

LJÓÐAHÁTTR (“song” or “ballad metre”)

- Usually made up of stanzas with four lines each

- Odd numbered lines were usually standard lines of alliterative verse with 4 lifts and 2 or 3 alliterations. It was cut in half with a “cæsura” or “//”, which indicates the end of one phrase and the beginning of another.

- Even numbered lines had 3 lifts and 2 alliterations, with no cæsura.

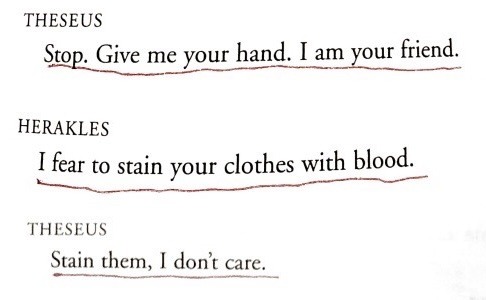

Ex: from Freyr’s lament in Skírnismál (structure provided by wikipedia)

WRITING IMITATION

When writing an imitation of Eddic and Skaldic poetry, there are many workarounds if you don’t want to jump through these hoops.

Personally, I am putting forward my imitation as a “translation” of an Old Norse text so I don’t need as much concern for alliteration, rhymes, and exact syllables.

But I enjoy having a similar feel to the original poems, so I do try to put in some alliteration for words that are of Norse/Germanic origin and keep a similar syllable count.

Posted: 2023 May 29

Edited last: 2023 May 30

Writing and research by: Rainy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thor’s Thunderstorm

I sit upon a stone

upon a path to rest

the sky darkens

and thunder rolls in the distance

I sit upon a stone

while the air smells of rain

a freash crisp scent

of wet earth

The sky glistens

as the rain starts to pour

To escape from getting drenched

I find a tall oak tree

Thunder crashes in the sky

and my mind wonders to Thor

God of thunder

Thanks to Thor

For the summer Thunderstorm

Hail THOR!

Thunder cracks and roars

like a lion in the sky

Lightning lights up the sky

As if Thor heard my prayer

#heathenry#norse pagan#paganism#pagan poetry#pagan prayer#paganpride#norse heathen#norse gods#norse poetry#witchy poetry#poetry#poets on tumblr#poets corner#poetscommunity#writers and poets

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Structure

Old Norse kennings take the form of a genitive phrase (báru fákr "wave's horse" = "ship" (Þorbjörn Hornklofi: Glymdrápa 3)) or a compound word (gjálfr-marr "sea-steed" = "ship" (Anon.: Hervararkviða 27)). The simplest kennings consist of a base-word (Icelandic stofnorð, German Grundwort) and a determinant (Icelandic kenniorð, German Bestimmung) which qualifies, or modifies, the meaning of the base-word. The determinant may be a noun used uninflected as the first element in a compound word, with the base-word constituting the second element of the compound word. Alternatively the determinant may be a noun in the genitive case placed before or after the base-word, either directly or separated from the base-word by intervening words.[2]

Thus the base-words in these examples are fákr "horse" and marr "steed", the determinants báru "waves" and gjálfr "sea". The unstated noun which the kenning refers to is called its referent, in this case: skip "ship".

In Old Norse poetry, either component of a kenning (base-word, determinant or both) could consist of an ordinary noun or a heiti "poetic synonym". In the above examples, fákr and marr are distinctively poetic lexemes; the normal word for "horse" in Old Norse prose is hestr.

Complex kennings

The skalds also employed complex kennings in which the determinant, or sometimes the base-word, is itself made up of a further kenning: grennir gunn-más "feeder of war-gull" = "feeder of raven" = "warrior" (Þorbjörn Hornklofi: Glymdrápa 6); eyðendr arnar hungrs "destroyers of eagle's hunger" = "feeders of eagle" = "warrior" (Þorbjörn Þakkaskáld: Erlingsdrápa 1) (referring to carrion birds scavenging after a battle). Where one kenning is embedded in another like this, the whole figure is said to be tvíkent "doubly determined, twice modified".[3]

Frequently, where the determinant is itself a kenning, the base-word of the kenning that makes up the determinant is attached uninflected to the front of the base-word of the whole kenning to form a compound word: mög-fellandi mellu "son-slayer of giantess" = "slayer of sons of giantess" = "slayer of giants" = "the god Thor" (Steinunn Refsdóttir: Lausavísa 2).

If the figure comprises more than three elements, it is said to be rekit "extended".[3] Kennings of up to seven elements are recorded in skaldic verse.[4] Snorri himself characterises five-element kennings as an acceptable license but cautions against more extreme constructions: Níunda er þat at reka til hinnar fimtu kenningar, er ór ættum er ef lengra er rekit; en þótt þat finnisk í fornskálda verka, þá látum vér þat nú ónýtt. "The ninth [license] is extending a kenning to the fifth determinant, but it is out of proportion if it is extended further. Even if it can be found in the works of ancient poets, we no longer tolerate it."[5] The longest kenning found in skaldic poetry occurs in Hafgerðingadrápa by Þórðr Sjáreksson and reads nausta blakks hlé-mána gífrs drífu gim-slöngvir "fire-brandisher of blizzard of ogress of protection-moon of steed of boat-shed", which simply means "warrior"."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

O’ All-Father

Your pen I wield,

shaped as a sword,

to slay my enemies with word and prose.

O’ Hoárr,

to you I raise my arms,

blade in hand,

ready to fight the foes of justice,

and truth.

Your ravens circle me,

constant watchers of my words and actions,

judging me as I might judge myself.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

DEFINITIVE PROOF OF ALIEN CONTACT

discovered on VIKING RUNESTONE!!!

(not clickbait)

In the land of stars sails the sky-steed,

Frey’s Skíðblaðnir, towards its friend:

The heavenly-flying Hliðskjálf

with its holistic gaze over the flesh of Ymir.

The gracious gifts of Mjölnir and Megingjörð

and, too, Gungnir, came from beyond the bird-world,

Delivered by the star-dwarves;

who, dauntlessly, traveled to other suns,

Towards which they once took leave,

tearing the great gold-bird away -

Away from its passage around the world and its partner,

the path-sharing moon who walks the same arc.

In skyfaring flame-ships they departed,

As our dead now are honoured in blazing crafts,

So that they may reach the golden vessel,

Valhalla, which lives now within the constellations.

0 notes

Text

She is the one who stands with Her arms open,

Ready to welcome those who have walked across the Gjöll bridge.

She is not one to be tricked,

For Her holy name is renowned through the nine worlds,

All of which know of Her power:

She cradles the souls of those who come to rest with the Gods,

And She does not discriminate the peasant from the king,

Nor the humble from the noble.

To Her we send songs of praise.

Onto Her I entrust my life.

Beside Her does the Luminous One sit.

Upon Her is a crown made of ash.

Artist

#hail Hel#devotional writing#prayer#heathenry#poem#poetry#norse paganism#spirituality#polytheism#paganism#norse gods#Hel#deities#deity work#pagan

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

We imagine Loki's punishment in the mouth of the cave. After all, He is the god of many mouths, Hveðrungr, Gullveig's last stop, and Stitchlip. Why would he not be in the mouth?

Because you don't put out a fire by giving it, O Loptr, fine mountain air, sunlight, or wind.

You don't squelch a light with more light. You leave it in darkness to rot.

O, that dark primordial Thing. That cold-blooded Prometheus of the frozen north. How do you kill the deathless? You torture it to finality. Liver meet eagle. Sisyphus get happy. Loki, meet hole. (tale as old as time)

You leave him as deep as you can get him. Deep as the quick, that Blood Gave Loðurr.

And you leave that Goatballed Jester without the only thing he ever wanted. An audience. The sound of laughter. Good company.

And you leave that thrice bound sucker there to rot, wrapped round with the promise that your children, too, will be snuffed out like votive candles. Rot with them now and crawl home to your daughter. Crawling King Snake, welcome home.

That's what makes Sigyn so compelling. Sigyn, Victory Woman, The Thing With Feathers -

Rabbit says; "Joy To The Fettered,"

She flies down the tunnel, she comes heartbroken, she comes alone.

This is an Oubliette - who would choose to come but the Victorious?

This isn't Orpheus come to find her blushing bride.

This is Persephone making her bed with the mother of Monsters.

And she comes out again, from the depths which grant no mercy, with neither light, or joy, or wind, or sky. Just a bowl of poison, thirstier once emptied.

Sigyn, The Thing With Feathers, comes out of the cave and the stink and the rot. And does she stop a moment? Does she breathe the alpine air and sigh and maybe, just maybe, weep?

We know just this. She goes back.

Sigyn, The Thing With Feathers, knows that Nothing Lasts Forever. And someday, we know, all hell breaks loose.

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hail to you Loki

Revealer of Corruption, Speaker of Hard Truths

May your presence drain the festering wound

Remove the infection from flesh

And grant it godly hue once again

Sly One, Protector of Those Brave Enough to Speak Out

May we speak with unfettered tongues

And reveal the hard won truth

We hold your torch in our hands

#norse heathen#norse paganism#pagan#pagan poetry#paganism#heathen#rokkatru#norse#norse gods#rokkr#loki laufeyjarson#loki#lokean#loki deity#myth loki#norse loki#deity loki#lokideity#loki devotee

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Freyja in the honeysuckle breeze,

Freyja in the sap of the trees,

Freyja in the way beauty turns my cheeks red,

Freyja in the fight to get out of bed,

Freyja in the gold of my great grandma’s rings,

Freyja in the sound that the mourning dove sings,

Freyja in the tears when I cry out so lonely,

Freyja in the fact that love heals me.

Freyja in the taste of a first kiss,

Freyja in the fight against injustice.

-Velvet Rose (written by me)

#witchcraft#witchblr#pagan#Freya devotee#devotional#poetry#Freya#Freyja#goddess#nature#spirituality#paganism#norse paganism

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

drink up baby, stay up all night

the things you could do, you won't but you might

#Bucky#Bucky Barnes#Winter Soldier#catws#:) ten year anniversary this year catws heads how are we feeling#between the bars#scars#addendum i'm OK! just family stuff + also playing ac valhalla and reading around norse mythology and contemporary literature and poetry lol#some ppl have wondered where i have been. Here!! just. You know. scroll back for full explanation

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scandinavia - Old Norse Poetry - Literature and Oral Tradition

The following post describes the literature and oral traditions of Scandinavian peoples during the times of the Vikings. I describe the difference between skaldic and eddic poetry and define kennings.

A later post will have my resources and advice on writing imitations of both types of poetry. (Find it here!)

There are few primary sources of Scandinavian history and stories from the times of “Vikings”, or from the late 8th century to the late 11th century. There are artifacts with runic writing, but these are short and few in number. Most of the documents about Scandinavians written during their time are from outside sources (and often they are biased against the Norsemen) (source).

In the late 11th and early 12th centuries, Christianity and its method of writing in Latin was introduced to Scandinavia. After Latin was introduced, the oral traditions began to be recorded by a variety of authors, though the most notable is Snorri Sturluson (who compiled the Prose Edda) (source).

The most important to study of the Old Norse languages and the mythos of these peoples are the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda.

“The Poetic Edda is the modern name for an untitled collection of Old Norse anonymous narrative poems” (source). There are several versions, and the most notable is an Icelandic text called Codex Regius from the 1270s CE which has 31 poems. These poems were not written by any one poet, but were collected and recorded from oral tradition. The exact age of these poems are unknown, but are considered to be the only direct records of Norsemen from their times.

The Prose Edda “is an Old Norse textbooks written in Iceland during the 13th century”. Its major and most well known contributor is Snorri Sturluson, a scholar and historian. The contents of the book are accounts of Old Norse mythology. Many of its sources are the same poems documented in the Poetic Edda.

Now, more on Old Norse poetry. For the most part, history and stories of the time of Vikings were passed down orally in two types of poetry.

Skaldic poetry (named for their creators: skald, or court poets) mostly regarded history and celebrated kings and jarls. It typically included little dialogue and recounted battles in detail. In comparison to Eddic poetry, Skaldic verse tends to be more complex in style and uses dróttkvætt. It also uses more kennings. While not proven, there is some speculation that skald accompanied their verse with a harp or lyre (source). It is mostly recorded in sagas.

Eddic poetry (named for the book they are compiled in: the Poetic Edda) is narrative, where there is both a narrator and characters speaking. They are characterized by their focus on mythology, ethics, and heroes, as well as a simpler way of verse (using fornyrðislag, ljóðaháttr, and málaháttr). It uses kennings, but less extensively than Skaldic poetry. It is mostly dialogue (source 1, source 2).

Kennings are figures of speech strongly associated with Old Norse-Icelandic and Old English poetry. It is a “type of circumlocution, a compound employs figurative language in place of a more concrete single-word noun” (source).

Now, when I first read that, I had zero clue what the hell that meant. But this is my current understanding: a poetic device where you dance around using a single noun by describing it with other words. It is similar to the poetic device of parallelism.

- “bane of wood” = fire (Old Norse kenning)

- “sleep of the sword” = death (Old English kenning)

- Drahtesel = “wire-donkey” = bicycle (modern German kenning)

- Stubentiger = “parlour-tiger” = house cat (modern German kenning)

- Genesis 49:11 “blood of grapes” = wine

- Job 15:14 “born of woman” = man

In a later post I will go into further details of the exact format of the two types of poetry. But it will be in the context of writing imitations.

Posted: 2023 May 29

Last edited: 2023 May 30

Writing and research by: Rainy

#vikings#poetic edda#prose edda#snorri sturluson#viking poetry#skald#skaldic poetry#kennings#kenning#eddic poetry#edda#old norse#old norse poetry#norse poetry

0 notes

Text

For those that are interested in my attempts to write the Poetic Edda into the so-called haiku meter, I've posted a free to read excerpt of Loki's Haiku Duel to my Ko-Fi page

If there's enough interest, I may consider (read: definitely will) post the full poem to my Ko-Fi page.

#butchering eddic poems is my passion#north sea poet#heathenry#poetry#lokasenna#my poetry#bragi#nico solheim-davidson#heathen#norse mythology#norse paganism#my poem#my own poetry#loki#haiku poetry

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

ᛆᚱ ᚢᛆᚱ ᛆᛚᛑᛆ

ᚦᛆᚱ ᛂᚱ ᚤᛘᛁᚱ ᛒᚤᚵᚧᛁ

ᚮᚱ ᚤᛘᛁᛋ ᚼᚮᛚᛑᛁ

ᚢᛆᚱ ᛁᚰᚱᚧ ᚢᛘ ᛋᚴᚰᛔᚢᚧ

ᛂᚿ ᚮᚱ ᛋᚢᛅᛁᛐᛆ ᛋᛅᚱ

ᛒᛁᚰᚱᚵ ᚮᚱ ᛒᛅᛁᚿᚢᛘ

ᛒᛆᚧᛘᚱ ᚮᚱ ᚼᛆᚱᛁ

ᛂᚿ ᚮᚱ ᚼᚰᚢᛋᛁ ᚼᛁᛘᛁᚿᚿ

Ár var alda,

þar er Ymir bygði;

ór Ymis holdi

var jǫrð um skǫpuð,

en ór sveita sær,

bjǫrg ór beinum,

baðmr ór hári,

en ór hausi himinn.

The age was old

when Ymir (Twin) lived;

from Ymir’s flesh

the earth was formed,

and from his sweat (i.e. blood) the sea,

boulders from his bones,

trees from his hair,

and from his skull the sky.

First two lines are from Vǫluspá 3, the rest is from Grímnismál 40

(sang by Gealdýr)

#old norse#norse#heathen#heathenry#gealdyr#skald#skaldic poetry#voluspa#cosmology#runes#runic#futhark

69 notes

·

View notes