#native science

Text

TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE (TEK)

Unlock ancient wisdom with Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Explore the fusion of indigenous insight and modern science for sustainable living.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), also known as Indigenous Knowledge or Native Science, refers to the evolving knowledge acquired by indigenous people over hundreds or thousands of years through direct contact with the environment.

For a long time, TEK based on native peoples’ experience in dealing with nature and natural resources for thousands of years have been overlooked by the modern…

View On WordPress

#climate change#economy#environment#esg#native science#natives#society#sustainability#tek#traditional ecological knowledge#wisdom

0 notes

Text

I just found out that I won two scholarships

#gratitude#personal#how is life so horroble yet so good#academia#indigenous excellence#native science

0 notes

Text

Taking Steps to Recognize Indigenous Peoples

Taking Steps to Recognize Indigenous Peoples

Let’s Start with Names

Seek-Seek-Qua by C. Coleman Emery

When I returned home from a September camping trip, I opened my book (Night of the Living Rez) and found a plastic knife holding my place.

I had used the knife as a bookmark while reading during a rainstorm in a cabin in the woods.

We rented a two-room shack at Lake Olallie Resort, which is sequestered in what is now called the Mount…

View On WordPress

#American Indian#Indigenous Science#journalism#native american heritage month#native press#native science#rhetoric

0 notes

Text

On April 24, 2024, the Havasupai and Hopi Tribes, represented by the Native American Rights Fund, along with the Navajo Nation filed to intervene in two cases in the U.S. District Court, District of Arizona. The cases challenge last year’s designation of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. The Ancestral Footprints region is the Tribal Nations’ homelands, and it includes places held sacred by the Tribal Nations and their members. The Tribal Nations have the right to intervene in these cases because they have significant legal interests that could be affected by the proceedings and that will not be adequately addressed by the existing parties in the case.

#indigenous#native american#ndn#good news#nature#environmentalism#environment#climate change#science

638 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forget hot girl summer it is

Citizen Science Summer!

Get on eBird, iNaturalist, Seek, whatever apps and forums are cool to you and discover the huge variety of life right under your nose! Snap some pics and record those critters! Rejoice for native bees and plants growing wild by the roadside!!

#ecology#citizen science#ebird#inaturalist#seek#nature#biology#native plants#ecosystems#citizen science summer

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Smithsonian returns woman’s brain to family 90 years after it was taken - The Washington Post

https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2023/09/08/smithsonian-returns-brain-taken/

An 18 year old indigenous Alaskan woman's (Mary Sara) brain was removed (stolen) from her body without her consent, her family did not consent, no one knew about this, and was sent to the Smithsonian all because a racist physician wanted to add the brain to his collection that "proved" white superiority. File this under one of the many reasons why I don't care that white people get their feelings hurt when I say I don't trust white people.

I'm glad that Mary's brain has been reunited with the rest of her body. I'm happy that her family got to give her a ceremony. This never should have happened in the first place though.

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was so, so lucky to meet a very special trio of snakes for a class I'm taking on methods in field ecology. One of my two professors is a specialist in garter snakes and was kind enough to bring three different species in for us to compare in person and observe up close. The first was the gorgeous common garter snake, Thamnophis sirtalis, pictures above. She was so calm and well-mannered!

Next was this tiny (by comparison) T. elegans dude, a western garter snake, who was wary of the camera but very patient about being passed around by a group of excited college students. He matched my classmate's sweater perfectly!

Finally, an endangered and incredibly precious T. gigas, the giant garter snake. She's about half of her maximum adult size, so a giant indeed! She musked and peed a bit but for the most part this gojira-faced beauty was pretty chill. We got to observe a full work-up for her including documenting records and microchipping.

She's one of the last of her species. Despite Herculean efforts by her protectors and conservation experts (mostly just one man and his dedicated team), this is a very difficult species to observe in the wild and their habitats are disappearing faster than their need for prioritization of protection in a given area can be assessed. These snakes rely on riparian habitat near rivers, which is also unfortunately a favorite for human development. At this time we don't know how exactly many giant garter snakes are left or whether their current populations are stable.

Today we got to visit their marshland habitat and watch these three go back to the place where they were caught. It was a huge honor and something I'll carry with me forever.

#snake#snakes#reptile#reptiles#reptiblr#garter snakes#garter snake#native species#we put that thing back where it came from or so help me#so help me!#science#ecology#endangered species#giant garter snake#western garter snake#common garter snake#when i got home i ate a salad so big that it made me sleepy

468 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I went on a phenology walk at Ozark Audubon today. We were mainly looking for any flowers that might have survived the freeze a few days ago, but we found some other neat stuff, too. This was one of the coolest! Look closely at the end of the branch--you can see where it has been neatly carved away, and then snapped in the center after the branch died.

That's the work of the female twig girdler (Oncideres cingulata), a species of longhorn beetle found in the east and midwest United States. She girdles the branch of a hardwood tree, lays her eggs in the branch, and then after it falls the eggs hatch and the larvae feed on the dead wood.

#insects#beetles#invertebrates#trees#native species#Missouri#Ozarks#nature#wildlife#animals#ecology#environment#science#scicomm#biology

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

What feels so strange about growing plants, and making friends with plants, and generally being aware of my ecosystem, is that it's not a "head" knowledge, it's a "hands" knowledge.

It feels strange for me, at least. My formative years were spent in a homeschool co-op that was roughly 50% anti-vaxxers, so in spirit, I'm the sort that has yelled "just believe science!" until my throat hurt. I've clung to peer-reviewed papers, as an abstract concept, as the sole beacon of truth in a dark world, and found Facebook groups full of people that thought just like me: if it's not proven, if it's not science, it's false, and science is truth.

There are online communities of people who "believe in science," and t-shirts that affirm the wearer to "believe in science." This is not the worst place you can be, in a world where people believe things like "eating lemons makes your blood more alkaline, which cures cancer" and "polio was renamed to ALS in order to hide the fact that polio vaccines don't work."

However, science is not a doctrine. It's a process. It points to truth, but it doesn't produce truth as an end result. There is no end result. The results are endless, actually.

What word do I use to describe what I've been doing? I'm gardening, sure, but that makes it sound like I do things to plants, when mostly, the plants do things to me. I'm learning about the living things already around me. I've learned to identify so many plants, and I know about what role they serve in the ecosystem.

"Gardening" is a difficult word because it means planting things in the ground and tending to them, but plants plant and tend themselves. So since we have to use the word "gardening," we have to think of plants as either belonging to a garden or not, depending on whether a human put them there. Plants either grow on their own or a human, a "grower," "grows" them. Isn't it weird how that verb is transitive?

However, I understand now that even knowing the name of a plant is, in some way, "gardening" it, because it affects my behavior toward that plant, which is the thing that "gardening" is, just in a different amount.

Humans can transport seeds and plants, supplement nutrients and water, but this is just participation. A gardener doesn't create plants, they help them to grow. So it follows that any act of "helping" is also gardening—thinning out a stand of wild plants, moving a wild plant from one spot to another, choosing not to mow a wild plant down.

I have more of something than I used to. The thing that I have more of now is knowledge, but a lot of this knowledge isn't facts. Ecology is a science. Scientists study ecosystems. It is possible to know facts about ecosystems. But ecosystems are not made of facts.

I know that most people desperately need to know more about the ecosystems around them. They need to know about the plants and trees near them. I think this is literally essential to saving the world as we know it. But they don't need to learn facts—not just facts. They need to learn something Else.

For the past several months, I have been learning things that are not facts. I hesitate to call them skills. But they are like skills. Both gardening and plant identification are impossible to fully teach from a book or a written resource, because you have to know not what something is, but what it is like.

I rely on my senses—feeling the suppleness of a twig, the dampness of potting soil. Identifying plants is so hard starting out because the qualities that identify them best have to be experienced.

Back when I was first learning to identify trees, I discovered that there was a black walnut tree at the end of our road. I was just then entering the extremely frustrating reality of how many plants there are and how few photos of them at all growth stages exist on the internet. I didn't know what a fucking "petiole" was. Leaves all just looked like leaves and I wanted to cry.

But I tore a twig from one of the trees down at the end of the road, and I instantly knew it was a black walnut tree! And I couldn't describe to you how. I caught a whiff of the smell of the crushed leaves, and it pulled up a memory of the walnut trees at the farmhouse when I was a child, dropping their heavy green fruits all over the grass. I'm not even sure how to describe the smell. It's very fresh and spicy, but earthier and less "clear" than the word "fresh" would suggest.

And I identify a lot of plants in ways that you can't just...depict. Alianthus altissima, tree-of-heaven, is hard to draw or photograph in a way that lets you see through the picture what makes it distinctively Alianthus altissima. The best way to identify it is by its odor. Tear off a leafy twig and smell it—it smells exactly like peanut butter and the mustiness of a damp basement.

I am learning things that don't exist in books, that are specific to my immediate surroundings. The specific community of organisms found in my backyard, what they're doing. How my plant and animal neighbors are related, and how their relationships change.

I am learning just how little we know. There are so many plants, so many local plant communities. There are more relationships in an ecosystem than there are scientists that could possibly study them. I look up a question about a particular plant and there's just...nothing.

I have to use my own knowledge, my own observations. I have to do tiny science every day, where Big, Capital S Science can't help me. "Is this non-native plant harmful enough that it is better to get rid of it even if I can't replace it yet, or is it providing enough benefits to other organisms that it is better to let it stay?" Sometimes no website or book or article can answer this. Constantly I encounter this kind of question, and I have to observe and decide myself. I have to trust that I can be taught by my ecosystem, and that this knowledge is, in its own way, valid.

It is uncomfortable to be here. I want to convey my knowledge to others, but it sometimes feels almost pseudoscientific, superstitious. I want to be rational and rely on the experts, and teach other people to do so; I know that what "seems" right often isn't, and that personal observations are flawed, even useless, in many areas. But not only are these fuzzy, instinctual observations sometimes all we have, they are an essential skill that is needed to save our world.

There's also the fact that research doesn't happen fast enough to function all alone as a guide. Invasive species lists on state websites are basically decades out of date and not regionally specific enough. The Callery/Bradford pear tree, bane of my existence, is not "officially" designated an invasive species to my knowledge, and there is relatively little research on its role as an invasive species, but it is declared invasive, primarily by common consensus that it's Satan in tree form. Crowding and shading out other mid-succession shrubs and trees, forming thick, almost monoculture masses of ugly glossy foliage replacing whatever else would have grown there.

And the severe threat of the Bradford pear is specific to my region; its particular severity may be specific down to the square mile of land I live on. Some scientists may be studying it, but they're not studying my state, my county, my neighborhood.

It's insane how many TYPES of forests there are. You would think that within a specific biome and climate, a forest is a forest is a forest, but no. There are a bajillion specific associations of trees with specific relationships that form special ecosystems. It's insane how many types of moth there are, too. And it really blows your mind to look up a moth's host plants and read that we're not really sure of the full range of plants its caterpillars can eat.

You'll be reading something and it will say "We don't know this" but you will know, because you've seen it—and then you think to yourself, well, isn't that what people say about Nessie and Bigfoot and little green aliens? Can we trust what we observe for ourselves? Can we trust people to know what they see?

Maybe not—but we have to.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

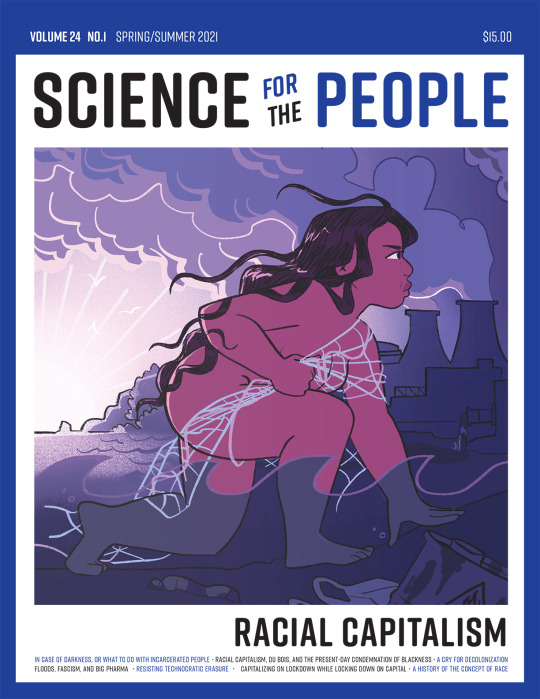

realized I never posted the cover I did for Science for the People's issue on Racial Capitalism. I'm co-editing the art for their upcoming issue, Ways of Knowing, all about the importance of indigenous knowledge <3

This is A CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS to any artists of the global south (Africa, South and Southeast Asia, South and Central America, Eastern Europe, etc) interested in doing editorial illustrations such as this on the subject of ecology, afrofuturism, indigenous-informed research of all kinds.

this magazine is so important. it's original run was from 1969-89, born out of the anti-war movement, and was revived by some really lovely people in 2019. if interested, send me an email (address is in my about page). if you know of someone who you think may be interested, feel free to share!

image description below:

The cover for SCIENCE FOR THE PEOPLE magazine, volume 24, on RACIAL CAPITALISM. The illustration depicts a brown woman with flowing black hair rising from a detritus-littered ocean shore with only a fishing net clothing her body. The sun rises behind her, and ahead there are power plants coughing pollution into a darkening sky. She looks toward the land with great determination to usher in a better world.

#illustration#science#capitalism#native#indigenous#science for the people#magazine#submissions#mariah-rose marie#editorial

397 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neolicaphrium recens here might look like some sort of early horse, but this little mammal was actually something else entirely.

Known from southern South America during the late Pleistocene to early Holocene, between about 1 million and 11,000 years ago, Neolicaphrium was the last known member of the proterotheriids, a group of South American native ungulates that were only very distantly related to horses, tapirs, and rhinos. Instead these animals evolved their remarkably horse-like body plan completely independently, adapting for high-speed running with a single weight-bearing hoof on each foot.

Neolicaphrium was a mid-sized proterotheriid, standing around 45cm tall at the shoulder (~1'6"), and unlike some of its more specialized relatives it still had two small vestigial toes on each foot along with its main hoof. Tooth microwear studies suggest it had a browsing diet, mainly feeding on soft leaves, stems, and buds in its savannah woodland habitat.

It was one of the few South American native ungulates to survive through the Great American Biotic Interchange, when the formation of the Isthmus of Panama allowed North and South American animals to disperse into each other's native ranges. While many of its relatives had already gone extinct in the wake of the massive ecological changes this caused, Neolicaphrium seems to have been enough of a generalist to hold on, living alongside a fairly modern-looking selection of northern immigrant mammals such as deer, peccaries, tapirs, foxes, jaguars… and also actual horses.

Some of the earliest human inhabitants of South America would have seen Neolicaphirum alive before its extinction. We don't know whether they had any direct impact on its disappearance – but since the horses it lived alongside were hunted by humans and also went extinct, it's possible that a combination of shifting climate and hunting pressure pushed the last of the little not-horses over the edge, too.

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#neolicaphrium#proterotheriidae#litopterna#meridiungulata#south american native ungulates#panperissodactyla#ungulate#mammal#art#convergent evolution#not-horse#a phony pony#quaternary extinction

478 notes

·

View notes

Text

This chart illustrates how much more likely there are to be caterpillars on native tree species vs non-native trees. This is critical because baby birds NEED caterpillars to reach healthy adulthood. Even if they are not insectivorous as a adults, many species use caterpillars as bird "baby food"

Source: Native plants improve breeding and foraging habitat for an insectivorous bird by Desiree L. Narango, Douglas W. Tallamy and Peter P. Marra

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

...Something's kinda hitting me, guys. I think something just clicked.

So we all know that BB!DOTC is the arc I'm not staying faithful to, right? A lot of characters are getting total overhauls? I'd actually been dancing pretty heavily around the pro-colonialism themes in the original text, simply because I don't really feel comfortable handling them (same with certain sexual themes, it's not great for my mental health to force myself to engage with certain elements that are triggering)

So I'd made it so there was Park Cats (Wind Coalition and River Kingdom) who arrived relatively recently, and Tribe Cats (Sky's Clan, Shadow's Clan) who nestle into an unclaimed spot in the forest. All groups roughly equal in power until Thunder's Clan which was existing in defiance.

But Clanmew isn't JUST comprised of Parkmew and Tribemew-- there's a third contributor. Old Townmew, which mixes with Parkmew and forms Middle Townmew, mixing again with Clanmew to create Modern Townmew.

Since I'm now really thinking about the colonialism themes, especially in my re-read where it starts reaching its narrative conclusion in Books 5 and 6... I think I need to add that 3rd cultural group. I need to make them a player. I think I'm doing a serious disservice by only having the Park Cats, Tribe Cats, and then saying all others mostly lived in the town.

I'm gonna do a BB!Brokenstar with Slash. Previously I'd just cut him completely-- but I think I should, instead, walk him back from being "Pure Evil" like he is in-canon and make him into a real character.

One Eye's a god drawn to the festering stink and rot of the First Battle; Slash is a mortal, leading a group like any other in the Forest Territories.

I think I'm also going to significantly bump up the time the Park Cats have been in this territory. Slash and his cats have been fighting them for years, and until the Mountain Cat influx, were basically spread through most of the Forest.

#Since BB!DOTC starts with leaving the mountain and ends with the First Battle#I'll also have a lot of time to explore Thunder interacting with all of these cats#Something often misunderstood is that Colonialism isn't... new.#It didn't come from capitalism. People have invaded and subjugated native groups for eons#What's new is how refined imperialism made it and how it's down to a bloody science now#I have plenty of cats to populate these groups too unlike newer material#Better Bones AU#BB!DOTC#I might have Slash and Thunder's groups eventually merge towards the end#That would make sense as to how Thunder's Clan was seemingly suddenly on a similar standing to Sky's#...could be a prettyyyy badass ending to the 'thunder ties to do a ton of diplomacy' arc by having him realize-#-his group has a LOT more in common with Slash than all the bigger groups#Kind of subvert DOTC's message by having him believe Slash IS a bloodthirsty monster who hates love and friendship#And then he realizes at some point. That was a fucking lie#That's sounding pretty good to me actually what do youse think

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

have I somehow ruined myself for perfectly average movies? I watched both Robots (2023) and The Deer King (2021) and both of them were fine---Deer King was better, but suffered from trying to jam too much into a single film; Robots should have been more black-humored, delighting in its lazy sociopaths and their vaguely squalid world. But that's it, that's all they were---fine. Just fine.

Does this mean I have to watch exclusively Films now? I can't get into a movie unless it's black and white, or two hours of characters speaking sideways and having neuroses at each other?

#I thought the deer king's hints of a broader bigger world were very effective though; some were devastatingly beautiful#(there's a scene where one of the narrators is talking about the tension between the imperial zolians#and the native aquafaese people; and on screen you're watching a mob of native aquafaese agitate their zolian guards#you cut to a young aquafa woman running hand in hand with one of the guards; they run to a river gorge and there's no escape#......and then you cut back to the main adventuring group; who are walking their horses past the river#you see the couple's blood-stained clothes caught on a branch in the river. nothing more is said.)#in that respect the movie was lovely; I loved its worldbuilding I loved the hints of more.#but it wasn't well-structured and I got the sense it was trying to be miyazaki without knowing quite how to pull it off#I also loved that science saved the day! natural resistance and cultivating antibodies for vaccination. love that nonsense.#a proscenium for our dreams

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

So for my final semester before I get my BA, I am doing an unofficial study!! If you have any kind of knowledge or experience with eagles, eagle feathers or just have an opinion on them, please consider filling out my questionnaire. I would be so, so thankful for any insight.

I am interested in the power and meaning given to the eagle and their feathers---especially by Indigenous peoples but I am also open to responses from non-natives if you feel compelled to respond.

Please share this if you're not able to respond! I would so so appreciate it!

#indigenous#native american#eagles#first nations#eagle feathers#academia#ndn#ndn tumblr#native americans#indigenous people#science#animals#indigenous rights#environmentalism#environment#nature#survey#questionnaire

384 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native Copper in Gypsum var. Selenite

Locality: Mission Mine, San Xavier, Pima County, Arizona, U.S.A.

*Blue in first image is sticky tack holding the sample in position, not part of the sample

#geology#rocks#minerals#mineralogy#mineral#fossils#rock#copper#native copper#gypsum#selenite#arizona#earth#nature#natural beauty#science

135 notes

·

View notes