#little henry weston

Text

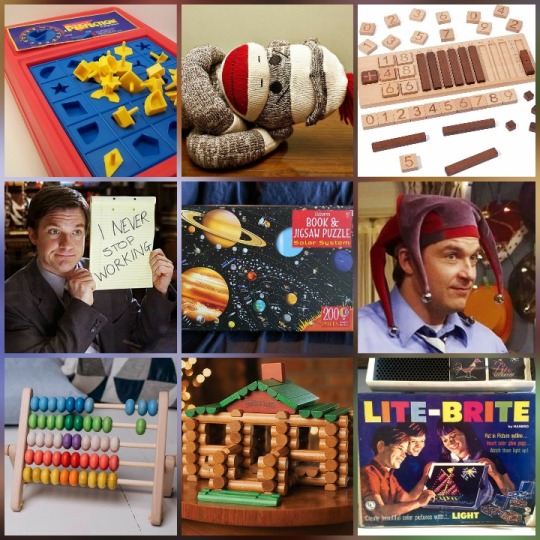

Little!Henry Weston

because i rewatched the movie a few times recently, and he just is!

+ an alternate

coming up with a few hcs for him

let him play pretend with hats or einstein dolls, or get some more hugs from that sock monkey! just let him stop working for a little bit lmao

#little henry weston#fandom agere#Mr. Magorium's Wonder Emporium agere#age regression#sfw#agere moodboard#this was my favorite movie as a kid :')

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

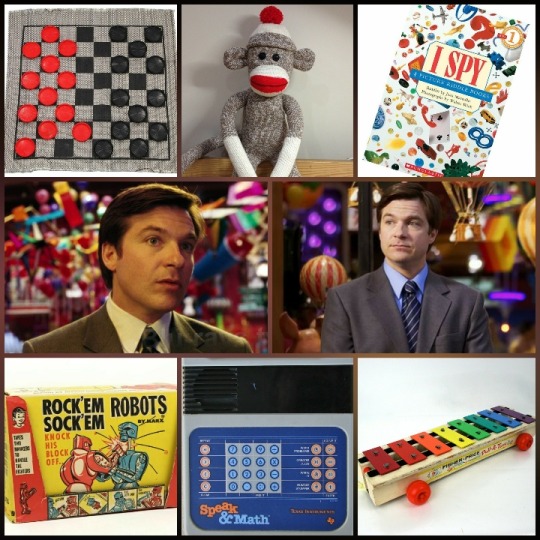

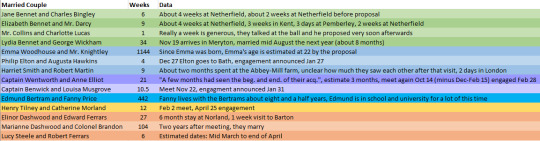

Northanger Abbey Readthrough Ch 12

Mrs. Allen, true to her character, says two lines in this chapter and they are both about gowns.

“Go, by all means, my dear; only put on a white gown; Miss Tilney always wears white.”

“My dear, you tumble my gown,” was Mrs. Allen’s reply.

Such a cute line:

This novel is always making me go AWWWWWWWW

Anyway, we begin with Catherine running over to the Tilney's residence to apologize and explain herself. Now during a morning visit, a person can "not be home" even if they are if they don't want to see someone, so when Catherine sees Miss Tilney shortly after she calls, she assumes this is a snub (we later learn it's actually because the General doesn't like being kept waiting).

Catherine knows this is an insult, but she isn't exactly sure what to make of it:

Catherine, in deep mortification, proceeded on her way. She could almost be angry herself at such angry incivility; but she checked the resentful sensation; she remembered her own ignorance. She knew not how such an offence as hers might be classed by the laws of worldly politeness, to what a degree of unforgivingness it might with propriety lead, nor to what rigours of rudeness in return it might justly make her amenable.

Again, we see that unlike Marianne Dashwood, Catherine has a really hard time dwelling in her disappointment, "She was not deceived in her own expectation of pleasure; the comedy so well suspended her care that no one, observing her during the first four acts, would have supposed she had any wretchedness about her."

Now when she sees Henry Tilney and he gives her such a short bow, she thinks he's very angry with her. However, we do know from later in the book that Henry turns into a different person around his father, so that may be some of the explanation for his sour expression. He does, however, come to see Catherine at her box and she immediately explains herself, borrowing an expression from Miss Thorpe, "I had ten thousand times rather have been with you"

We find out that Eleanor Tilney has been in just as much anxiety to explain herself as Catherine has been! Eleanor is clearly shipping Henry and Catherine already (AS SHE SHOULD!).

Then we get into this little bit about Henry Tilney having no right to be angry. I think the point here is that she hasn't made any promises to him really, so he can't be jealous of her time. This is very non-presumptuous, unlike Mr. Elton in Emma, who at the Weston's party tries to assert control over Emma's movements (telling her not to visit Harriet). My point is...

The way Austen has with words is amazing, "He remained with them some time, and was only too agreeable for Catherine to be contented when he went away." So understated but also so cute! This novel is just SO CUTE!

It'd be cuter if stupid John Thorpe wasn't back. Now we know from later that this is a critical moment, John tells the General that Catherine is the wealthy heiress of the Allen's fortune. On this information, General Tilney will instruct his son to "seduce" Miss Morland (to marriage). This also explains the invitation to Northanger.

Now, we know that Henry and Eleanor are confused by their father's interest in Catherine, but I don't think they know exactly how wealthy she is either. Henry does clarify that Catherine has never been abroad when she mentions the countryside of France during their country walk. We can assume that Catherine has been very honest about her family situation. I think John Mullen talks about how Catherine doesn't even seem to really know how wealthy she is. When it comes to reality, a dowry of £3000 isn't the best, it's not bad. (cough cough, did you see how a clergyman with ten children managed to save for dowries MR. BENNET?! cough)

John Thorpe tells an entirely ridiculous story about beating the General at pool (I doubt this happened) and then says again, that General Tilney's "as rich as a Jew", which is apparently his favourite phrase to use with rich people. Then John attempts to flirt with Catherine but she is having none of it, she's only happy that General Tilney likes her.

#northanger abbey readthrough#northanger abbey#john thorpe#general tilney#jane austen#catherine morland

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

🤢 what’s a popular ship you despise, and why?

lmaoo, i feel so out of the loop with bookish stuff that I'm not quite sure what is 'popular', and I've already made my feelings on every SJM love interest under the sun known so-

Ships that I didn't vibe with in stuff I read recently:

Emily and Simon from Well Met by Jen DeLuca - this book was so frustratingly mid generally? But then these guys just didn't seem to like each other. I think if the author had either given them more justification to snipe at each other or just gotten rid of the 'enemies' part altogether, they would vibed more. As it was, the ace in me didn't get it. Like yeah girl he's hot in his cosplay but the rest of the time you can't stand one another and you cannot hold a conversation to save your life.

Harriet and Wyn from Happy Place by Emily Henry - I think the balance of angst to fluff in this book was a little off, so the moments where I started to believe they had chemistry didn't last long enough to sustain my interest

Margaret and Weston from A Far Wilder Magic by Allison Saft... I just. I know what this book is fanfic of. She did the original characters dirty they should have so much more chemistry than this.

Jacks and Evangeline *specifically* in A Curse for True Love by Stephanie Garber - don't get me wrong. I was on board in books 1 and 2. I love it when a man is Howl-coded and eats apples, and kiss scenes are so horny you begin to worry if PG13 is even a thing. But this final book dealt me so much psychic damage generally, up to and including the erasure of any motivation for Evangeline beyond Her Single Horny Braincell, that I truly got bored. They were ketp apart for pointless, cryptic and badly written reasons, and really weren't that interesting towards the end, all of the enjoyment I had in the previous books disappeared.

bookish asks!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The King's Mind by Christopher Rae: review.

"How curious men are, how much is hidden, how much left unsaid."

A very late post for @fideidefenswhore sorry for the wait xx

TLDR: Solid, but I have some Notes. Rae is knowledgeable but he falls into some common pitfalls. Not as good as Rae's The Concubine. The pacing is weaker, and unlike The Concubine there is a Whiggish streak that gives the book a preachy taint.

Long post below.

Henry: I'm not easily persuaded

*a few moments later*

Henry: you know what? I've been deceived.

The book starts in media res and even I am a little lost and confused. The book hops between first and third person without warning which gets easier but at first takes some getting used to. Was it always necessary? We go from third person "a sky streaked with red and gold" to Henry saying the sky is streaked with red and gold.

The presence of Weston and Norris in this book is good. It was a good choice to emphasise the presence of Weston and Norris at the coronation. I think a lot of writers tend to forget they existed before 1536. They're Henry's Great and Loyal Friends yet they pop into existence ex nihilo solely so they can be beheaded. Obviously their presence also makes good foreshadowing. They're natural portents of doom.

Sometimes, as is often the way with first person POVs, Henry gets too self aware: “He knows how easily I can be mollified by a good cash offer”. But Rae's is probably the most interesting and nuanced of the Henries. Rae captures his ego: "Mark, who plays the lute so prettily, almost as well as myself." Cromwell “is now better informed than any man alive, with the exception of myself." After a whole book of his ego, Duchess Mary roasting Henry at the end was remarkably cathartic. Girl's got a point.

Henry has a serious case of doublethink. "My sweet Anne, so mild and sensible. I know that they are all constantly working upon her to have their way in this, but she is the true friend of my heart and her counsel will always be in my best interest. Of course, she is right."

On the very next page: "Anne’s eyes gleam with triumph, she believes she has influenced me to align myself with her purposes, and has won the field."

"Anne is naive sometimes and behaves as if matters of grotesque complexity can be reduced to simple solutions, simply because she wills it so."

Pot calling the kettle black, Your Majesty.

"More does not learn from the world, he merely seeks to impress himself upon it."

POT CALLING THE KETTLE BLACK, YOUR MAJESTY.

"I am glad of it, your majesty, for I am certain of what is true. This strikes me as an odd thing to say at first, but upon reflection I decide that I rather like it, and might profitably adopt it for my own use."

I don't have much to say about this moment, it's just funny and feels very Henrician.

“The king is like a man who sets fire to his own house, and then goes crying in the street for help.” Wolsey decides to ignore this while privately acknowledging the truth of it."

Wolsey:

“The honour of my betrothed must be preserved, and passion must bow before patience.” There's some nice moments of Tudor-style courtship, and Rae does a better job than most of giving Henry a distinct voice: “Diana, flushed with the exertion of emptying her quiver. By the mass, she is pretty when she is roused.” "Ah, my sweet, but I will never allow it. For that would kill me, and I cannot let you become a regicide." “return to the palace where there is precious little pleasaunce now.” PUN! Henry described himself as the king of disappointment, I liked that moment.

Many Henries are pretty gullible, but this Henry has a certain low cunning and I like the interpretation that while he's swayed by Anne he is quite manipulative himself: “I play the innocent most cruelly deceived, and I know that she finds me plausible.”

In terms of pacing, there is a tendency towards repetitiveness. PARTLY but not wholly because, let’s be real, the KGM has a repetitive nature. Like we get it already, Wolsey's fat, he's gotten fat, he's big, he's bulky, he's plus-size, he's chubby, he's out of breath WE KNOW. Anne is impatient and worrying about her age, WE KNOW. Henry is impatient and wants to marry Anne. Wolsey thinks it can’t be done. Wolsey thinks Henry is like a kid who has to be told he can't just have whatever he wants because he wants it, WE KNOW. Henry is fickle and people hope he will tire of Anne. WE KNOOOOOOOOOOW. The book also goes back in time to 1528 less smoothly than in the concubine. (Also, this book again calls Katherine 'Aragon' instead of Princess Dowager, sometimes the Spaniard, which works better.) You could probably cut out Latimer’s recantation to Warham as it repeats what we got from other scenes.

I must give this book some leeway and acknowledge that I'm just not as interested in the political dimensions of the KGM as I am the intellectual and theological dimension: partly because I find it boring and frustrating the way it constantly goes around in circles and there's this document and this document. But personal preferences aside, I still think the book could have been less repetitive.

“she contains within her a deep strand of idealism…But if Anne lacks anything, it is an understanding of the pragmatism that accompanies power.” Anne overall is better characterised in The Concubine. Here it is Anne's insistence that keeps Mary from her mother while Henry is willing to let them meet. Hmm. Disagree, but it's not too bad.

“Thomas More, Bishop Fisher, and of course the great red whale- Wolsey.”

I choose to interpret 'great red whale' as a reference to the 'white whale' in Moby Dick. Wolsey is Anne's equivalent of the white whale.

Ambiguity just how corrupt Wolsey is. "The fate of his grace the Duke of Buckingham, brought down by Wolsey and sent to the block, is not forgotten"- Buckingham's fall was Henry's doing. Wolsey actually warned Buckingham to be more careful.

"And Norfolk? His grace has all the diplomatic ability of a culverin." "Norfolk has nothing to do with things that are broken." Norfolk is slightly softer in here than he was in The Concubine, and not angry all the time.

Unlike The Concubine in this novel Cromwell seems to have a hint of being an evangelical, being motivated by religion.

"Today he will truly make or mar."

"As ever, in the shape he shows to the world, Cromwell is quiet, unassuming, and affable. Not blessed with a great deal of the outward glamour which tracks the interest of women, he relies instead on comporting himself in a manner which causes men to desire his presence."

Men desire his presence, you say? *Eyes emoji*

Also speak for yourself Cromwell is dummy thicc

Rae gives us a witty and remarkably sympathetic Gardiner. He's not usually given this much attention, or depth to his motives and thought process. We have him admiring Cranmer's intelligence.

More has more energy than usual which I like. He's usually depicted as soft-spoken for some reason when there's no indication in the primary sources that he had a quiet voice. We'll get to the problems with him later in the review.

"Fisher... the sympathy he drips with is not of a personal nature. For him Catherine is nothing more than a simple minded, weak, creature, as all women are, and he thinks that she has failed England and the one office which should have justified her feeble existence- to provide the king with the heirs he needed."

I'm not a fan of Fisher but DAMN that's an unusually unsympathetic portrayal. What a meanie. But it's refreshing to see Katherine of Aragon's supporters as less than noble or admiring for a change, at least in their heart of hearts.

Like The Concubine, there are some great turns of phrase.

"For some time he sits there, like some Saint of the early church undergoing a particularly unpleasant and imaginative martyrdom at the command of a Pagan emperor."

"And for the first time he begins to despair, because for the first time he sees clearly that he does not have the power to truly open their eyes. The terrible, inescapable conclusion begins to oppress him; There is actually nothing he can do to prevent disaster."

^^I like this moment because it encapsulates the feelings of many people in the Reformation, on both sides.

“I was nothing more than an empty vessel, like unto A goblet made in the most glorious and rich fashion, but empty nonetheless, a vain, dry thing. Here is the wine which was lacking, it comes now brimming, overflowing, and sweetest tasting anything upon the earth.”

^^ A particularly evocative and authentic conversion narrative.

This book also had some good analogies, like this one: "Master Christopher, think of the king as like a man who has inherited a battery of cannons."

Rae did a good job in this book with foreshadowing and instilling a sense of doom:

“There is a heaven for Anne Boleyn, in which she ascends uncontested to the throne as Queen of England, and a hell also, in which she is confined to being seen as nothing more than the king’s mistress, until he tires of her and moves onto the next one.”

^^It really drives home that Anne's fate is beyond her wildest nightmares. HILLARYYYYYYYYYYYY

"The shadows that have claimed the last of the sunlight are gone from the garden, and the Cardinal's face is now in shade, the whole of his vast bulk entirely consumed by the dusk."

^^A nice bit of pathetic fallacy and foreshadowing of Wolsey's downfall.

"Norfolk, so fond of sending people to the tower. Perhaps he will get the chance to see what is like one day himself?" “As she listens Anne’s eye is drawn upwards; she senses black shapes moving in the air, and she sees two ravens alighting upon the crenelated rampart high above. A sudden chill descends upon her, and she shivers.”

There are some good details in this book. Wolsey in the garden in the evening- Cavendish mentions that he takes evening walks. "He smells of cabbage, cabbage and wet horse dung!" A reference to Gardiner's skill at salads? “but the heat will recede, as it does when the sun progresses around the world and the hours of darkness begin.”

"But as I recall, when Hercules cleaned the stables he also slew the man who owned them. Because Augeas would not pay him for his work, Thomas. I think the king preferred to leave them as they were."

^^ a nice classical analogy. I wish Rae paid more attention to humanism and the classical learning of the characters. He tends to forget about the existence of humanism and the fact that the Reformation isn't binary, especially at this moment in time.

Not all the details are correct: The great seal of England sits inside a white linen bag when it was actually a white leather bag.

Rae continues to have good moments of levity:

“His single word expires, friendless and alone. He looks down at the floor as if he has lost its companions and thinks they might be down there somewhere.” “Ah yes, but there are only so many wives a man may take, before things start to become complicated. I think Henry has discovered this already, no?"

"By the mass I would have her now, hereupon the sweet earthen floor of the forest, with the sound of the rain hissing down upon the leaves around us."

Someone's watched The Tudors.

"His face, when he sees who has come uninvited and unannounced, is a picture, and his people begin at once to scurry to and fro like frightened chickens."

Someone's watched A Man For All Seasons.

"Thomas Howard. And Charles.... Charles..." he pretends to struggle to remember Suffolk's name. "Brandon? My Lords, you are welcome, though your message is not. Let me explain something to you."

Norfolk’s face contorts into an ecstasy of fury and hatred, and his hand reaches for his belt before he remembers he is unarmed. ‘You are ended, Wolsey. By the mass I will kill you myself, with my bare hands. "

Wolsey stares at him, unmoved . "my Lord is intemperate."

He (Suffolk) gropes for a suitably devastating parting shot, but his invention fails him, as it often does."

Hilarious, I love it, 5 stars, 10/10. Wolsey is delightfully bitchy and it's infinitely better than the meh equivalent scene in Wolf Hall.

Now for my Notes.

"The story is that he fell ill on the journey from the north, and died of it, conveniently. I do not believe it. Either he ended his own life, or someone helped him to do it".

While I love the intrigue, this novel has gone to SUCH lengths to stress that Wolsey is stressed, out of shape and in poor health. If there's one thing we know about Wolsey from this novel it is that he is F-A-T. He's also 57. He's no spring chicken. It makes total sense that he'd fall ill and die, especially after a long journey, drinking and eating from a variety of different sources, some of which may well be contaminated. But the characters speak as though Wolsey was a svelte Olympic gymnast who was spinning around on the crossbars until he suddenly died from eating some dodgy kale.

"Then he tosses what remains over his shoulder, and wipes his hands upon the silken cloth." I get that Francis I is the worst but people took etiquette seriously in this time period.

"Mary discovered a taste for them [kings] in Paris, and says that it was the recommendation of king Francis that brought her to the King's attention."

I'm pretty sure historians are questioning the old story that Mary slept with Francis?

Elizabeth Boleyn suggested Anne play hard to get (which I like) but later in the book Rae has Norfolk suggest it to TB years before. Yet Thomas B reacts to Elizabeth as if it was the first time he heard it. So what gives?

And like in the Concubine, Rae puts in things he's read uncritically from historians, and the result is something that makes no sense.

"His [Norfolk] affection for More is undiminished" yet the scene clearly shows that they have nothing in common, they see the world in starkly different ways, Norfolk sees More as vain and stubborn and More sees Norfolk as a crude toady. Norfolk even has a "menacing look" when he looks at More. So what is this nonsense about them having any affection? Well, like Jane Boleyn's nonsensical motives in the Concubine, Rae has read a historian, unquestioningly, and feels the urge to insert it into the story like a square peg in a round hole even though as a writer he can probably tell it doesn't fit.

There are some anachronisms- the phrase 'like a good Catholic'. 'Catholic' means united- Anglicans believe in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church". Protestant and Catholic are divisions that show up in the 1550s. "More is a fanatic"- fanatic is a very modern criticism. People at the time wouldn't object to religious obsession- the problem was if your doctrine was incorrect.

(Also Henry should be happier at the birth of Elizabeth.)

Now for the misconceptions.

While Wolsey did get his BA at 15, university students then were younger than they are now.

“Henry has been taught to stick to what the bishops tell him in matters of religion, and he derives his idea of faith his elders, who have made him think that orthodox observance matters more than a deep personal sense of a world imbued with the Holy Spirit. He is often reluctant to talk about such things, but she has formed the opinion that he is genuinely in motion, attracted by the scent of reform and willing to alter his thinking to accommodate change.”

Henry was given a (renaissance) humanist education. And the humanists like Erasmus were influenced by the late medieval devotio moderna that placed great emphasis on interior faith. Erasmus absolutely believed that inner faith was more important than outward show: that rituals like the Mass mattered, but that empty ritual was bad. But Rae falls into the false binary of Catholic: Rituals Good and Protestants: Rituals Bad.

Gardiner says: “Your majesty must know that the Pope holds the keys to heaven, there is no higher authority. If clarification or exegesis is required concerning the interpretation of scripture, then the final word must always rest with His Holiness.”

There IS a higher authority! Gardiner and More would tell you that the highest authority in the Church is a Church Council. Basically all the bishops across Christendom come together in a General Council and the Holy Spirit descends upon them invisibly, blessing the proceedings and giving authority to the decisions. If the Pope, say, tried to get rid of the Nicene Creed, Gardiner and More would say the Pope is wrong. Because the Creed comes from the Council of Nicaea, and a General Council >>>>the Pope. Papal infallibility doesn't show up until the nineteenth century.

"How can I help you, when I do not believe it is the right course for a Christian king to abandon his lawful wife? I make no secret of it, as you know. I am not one of those who will say anything in the hope of pleasing you."

More's stance was actually closer to: "I'm not qualified to speak on this issue so I stay well out of it". Fiction tends to portray him as more outspoken in Katherine's support (though he did like her as a person) than he actually was. Fisher was the one loudly objecting to the divorce. It was the Supremacy that More took issue with: he was willing to accept the new succession.

"Attend to your Scripture, and tell me where it says that our Redeemer left any vicar to succeed him upon this earth."

More and Fisher don't give a rebuttal to this in the book- because Rae can't think of one. But they actually could: a Catholic would say that Jesus said exactly that in Scripture. Jesus says to Saint Peter in the gospels "you are the rock on which I build my church." Then in the book of Acts, (the sequel) Peter is the leader of the early Christians in the years after Jesus zooms up to heaven. For Catholics, St Peter is the first pope. All the later popes follow him because of something called the Apostolic Succession.

(Also Catholics believe that 2 Maccabees supports Purgatory. Problem is, both 1 and 2 Maccabees are deuterocanonical and therefore less authoritative than the gospels.)

“Going to Wittenberg, I believe, where he intends to continue his work. A new testament in English, what do you think of that, Thomas?” He looks at me and I see the sorrow in his eyes. He thinks very little of it indeed.

“And how will things be then? When the plough boy reads Scripture in his own rude tongue? Without guidance, or education, without knowledge? Without the interpretation of the church placed upon it? He will say, ah, now I understand it, here is the meaning of this, or that. But when he meets his fellow they will not agree upon it, for this man will say, no- you have it wrong, it means this. They will not be of a like mind, and will fall into endless disputation strife. and the heretics will go about amongst them, stirring up whatever abominations they wish. There will be no order in what men think, no agreement. There will be no unity. That is what the church gives to men, unity, and it is our only hope of it.” “And if men throw off the authority of the church, whose authority will they look to throw off next?”

“If the church is corrupted, then it must be reformed, from within, by honest men of faith. Who has appointed master Tynedale to translate scripture into English? Who is there to supervise and approve the work? No one, because it is forbidden, and with good reason.”

This is a mixture of accurate and inaccurate. Yes, More did see the authority of church and state as connected. He argued that the church had every reason to support the king- because when anarchy breaks out, vulnerable priests and monks and their churches are attacked and looted. So it was in the best interests of priests to support, not subvert, secular authority and the rule of law. Yes, More wanted reform from within the church. He wanted political reform of the church not theological reform. He didn't want fewer priests, he wanted well-educated and well-behaving priests.

But More was a humanist. The ploughboy singing psalms as he worked? Exactly what Erasmus wanted. Even when the Reformation was underway, More still wanted an authorised English Bible, as he thought it would do some harm, but on balance, more good than harm.

So why did he have such beef with Tyndale? Because of how Tyndale translated the Bible. Tyndale's word choice in More's eyes undermined Catholic doctrine and made it look like Catholic doctrine didn't have Scriptural support- especially dangerous given that Tyndale was also saying Sola Scriptura. Tyndale pointed out that some of his word choices were the same as Erasmus' word choices. But More argued that Erasmus was translating honestly while Tyndale was being subversive.

And while More's Confutation Against Tyndale's Answer is a fierce criticism, More does quote Tyndale saying something he agreed with: More replies to this quote "this is well and holily spoken". So I wouldn't say More is blind with hatred for Tyndale, any more than Tyndale is blind with hatred for More. If More was blind with hatred, he wouldn't say anything positive about a single word of Tyndale.

“Like many wise men, Thomas More understands astrology and can read what is written in the heavens.” More knew astronomy. Astrology More thought was BS. But that doesn't fit the binary of Rational Protestants versus Superstitious Catholics, even though Rational Tolerant Elizabeth I believed in astrology while UberCatholic Pope Fan More was sceptical.

Rae’s analysis is Whiggish, and like most Whigs, it gets really preachy really quickly.

“His mind is the prototype of the totalitarian. One who has invested in a static system of thought, which cannot easily accommodate change or development. More thinks only in terms of certainty, and cannot bear the presence of doubt, which may undermine the fortress.”

Anachronism aside, historians actually debate whether More's opinions changed over time: if he became more religiously conservative as the Reformation progressed, having started as a humanist Catholic reformer. Personally, I'm on the side of consistency. More was never opposed to burnings and his last letter to Erasmus explicitly supports Erasmus and his work and calls Erasmus' critics jealous people. His debate with Tyndale is a Catholic Humanist versus a Protestant Humanist. And in classic humanist fashion they're arguing about language.

As for doubt: his patron saint was Doubting Thomas. So I wouldn't say doubt is the enemy to him, but that you must overcome your doubts by choosing to believe.

Also More did not see the Church as static. Catholics believed in progressive revelation: ie. you can add to the faith (things like purgatory) if the Church has a revelation that is authorised by a General Council. You just can't contradict the Bible. The Protestants want to go back to the OG Christianity: the faith of late antiquity, and cut out things like Purgatory that are seen as medieval accretions. They want the Church to go back to the old and keep it that way. They are not changing- they are undoing change, in their eyes.

“He [More] thinks himself to be a compassionate man, but is untroubled by the grotesque cruelty he has inflicted on those who have dared to oppose the orthodoxy which he deems essential to peace and salvation. They are given every opportunity to see their errors and recant, and if they will not then they must burn, so that the infection of heresy may be cauterised, and other vulnerable souls may be saved from it. This is a man of the highest intellectual capacity, who has earned his place among the most exalted thinkers of the new century.”

You could say this about literally anyone in the Tudor period. Cranmer is also considered to be compassionate, and his writing shaped the English language, but that didn't help Joan Bocher, did it?

"Now there is nowhere for men like More to turn, except back to persecution and mediaeval barbarity."

I haaaaaaaaaate this line. It’s so Whig history. As someone interested in ancient history and also the Tudor and early modern period in particular, I can confidently say that barbarity is absolutely not the preserve of the mediaeval period. On the contrary, the early modern period gives us more holy wars and witch hunts. Back to persecution? Persecution was ongoing. Protestants in heartlands like Zurich were drowning Anabaptists in the Rhine at the same time as Catholics were burning them!

(Also Protestants believed in the Trinity and infant baptism even though there's actually no explicit mention of those things in the Bible...)

#historical fiction#book reviews#just so you know: i'm not catholic#i've never been catholic#i'm just tired of one-sided portrayals of the Reformation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

🦇 The Perfect Guy Doesn't Exist Book Review 🦇

❓ #QOTD Name one favorite and one "ugh, no" trope OR what fictional character would you love to date IRL? ❓

🦇 What if your favorite TV character appeared in your bed one day and claimed to be your soulmate? When Ivy Winslow wakes up with the house to herself for a week while her parents are away, she doesn't expect to find the very hot fictional character from her favorite show in her bedroom. To figure out why her fanfic brought him to life, Ivy must team up with her current best friend Henry and former best friend/crush Mack. Can Ivy and Mack deal with the fallout of their friendship, or will they realize there was something bigger behind their fight all along?

💜 The strongest aspect of this story was the satire on overused media tropes (both from a television and writing standpoint). Weston starts off all heart-eyed, head-over-heels for Ivy, and it appears sweet and innocent. Once the bigger tropes come into play, readers see how they'd never work in real life. Even the "only one bed" trope we all know and love becomes frustrating (hello, boundaries?). "Touch her and you die" almost became a thing. The fanfic fusion into YA aspect is fun and playful, though I do wish we'd seen a few more parallels between Ivy's writing and Weston's actions. This is definitely a book fanfic writers will adore; a great example of messy wish fulfillment. Beyond that, the writing is effortlessly queer, as queer characters SHOULD be.

💙 Suspension of disbelief, especially when used in an otherwise contemporary setting, is crucial for a story that contains magical realism. For it to work, however, your characters have to act reasonably. Ivy just seems too naive. It takes her WAY too long to realize that Weston wasn't pulled from her favorite TV show, but from her fan fiction writing. Her reactions are a little too silly. Even her word choice makes her seem younger than she is. I understand differentiating Ivy's fanfic writing by adding grammar and spelling errors, but she's a student. It shouldn't have been THAT cringy to read. Usually, Sophie Gonzales writes young adults with a level of maturity and emotional intelligence. Ivy is less mature than expected (and yes, you can have a mature character who struggles with confidence and independence AND anxiety), which makes it difficult to connect with her. One of the benefits of reading YA is universal experiences (as adults, we've been there, we get it, so we can connect to it), but I couldn't connect to Ivy (and I was an anxiety-ridden fanfic writer who obsessed over every fandom, so I SHOULD have!).

💙 Ivy's lack of chemistry (even from a friendship standpoint) with Mack is concerning. There are versions of healthy co-dependency between friends, but these two don't have it. The flashbacks should have given us more of a reason to love these two together than Ivy coming out to Mack and having a crush on her (after that, we immediately see the flaws in their friendship, which completely lacks communication and therefore feels toxic). Perhaps it would have worked better without the romantic aspect; if we'd focused on Ivy and Mack restoring their friendship.

🦇 Recommended to fans of Rainbow Rowell.

✨ The Vibes ✨

🌬️ Bi, AroAce, & Lesbian Rep

🌬️ Sapphic Romance

🌬️ Young Adult Fantasy Fiction

🌬️ Friends-to-Enemies-to-Lovers

🌬️ Multiple Timelines

🌬️ Magical Realism

🦇 Major thanks to the author and publisher for providing an ARC of this book via Netgalley. 🥰 This does not affect my opinion regarding the book.

#queer books#book lovers#ya books#young adult books#young adult fiction#book reviews#book review#queer book review#sapphic romance#book blog#sapphic books#batty about books#battyaboutbooks#bi books#aro books#aro ace#lesbian books#fantasy fiction#ya fantasy#magical realism#book: the perfect guy doesn't exist#author: sophie gonzales#books and coffee

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Fortunate Man Indeed

No one was more delighted than Mr Woodhouse when Emma began requesting a bowl of gruel in place of her usual breakfast.

A Emma ficlet. Implied aroace(spec)!Emma. Written as a sequel to If I Loved You Less, though it can work as a standalone.

No one was more delighted than Mr Woodhouse when Emma began requesting a bowl of gruel in place of her usual breakfast; Mr Knightley, for his part, could scarcely be persuaded of his wife’s sudden inclination for healthful meals and retiring very early in the evening, though his concerns were promptly rebuffed as completely unnecessary.

“It is nothing, merely an upset stomach,” Emma was adamant in her refusal to have Mr Perry examine her. “I daresay I shall be well in no time at all, and I will not have you distress my father for such trifling a matter.”

Mr Knightley reluctantly let matters rest for a whole fortnight; however, things came to an unexpected head when, upon being presented her favourite dish, Emma turned rather green and fled the table so abruptly she very nearly upturned the chair in her haste. He immediately rushed after her, accompanied by a litany of querulous “oh dear, oh dear” from her father, who followed at a more sedate pace.

“I am well, Papa,” were Emma’s first words, as her husband waved for a servant to dispose of the potted plant that had been unfortunate enough to find itself in her path. “I will see Mr Perry, if you wish it, but I can assure you it is nothing of consequence.”

“Nothing of consequence!” Mr Woodhouse exclaimed, growing more and more distressed by the moment. “You know very well the risks inherent to such a condition, Emma, and I daresay I shall never understand how women are so willing to overlook the dangers of putting themselves through it all.”

“Condition?” Emma frowned, looking momentarily confused. “What is it that you are speaking of, Father?” At her side, Mr Knightley froze, struck by the sudden notion of precisely what Mr Woodhouse was hinting at; his arm tightened around her waist, just in time to offer his support as she evidently reached the same conclusion a moment later.

“Oh,” was all she could utter, sagging further into her husband’s hold.

.

They were well into the spring when Emma began to show, and by that time, Mr Woodhouse had mostly reconciled himself to the prospect of a new grandchild. John and Isabella were both thrilled for their brother and sister, and would not hear a word of Emma’s regrets for displacing little Henry from the inheritance he had been made to expect up until that point.

“I am exceedingly sorry for our nephew,” she professed one evening, reclining as she was on the parlour settee with her head in her husband’s lap. “I must confess I had not at all considered this outcome, when I accepted your proposal.”

“Surely when Mrs Weston and Isabella explained your wifely duties in such stark detail as to very nearly put you off the idea of ever marrying, they would not have failed to inform you about the natural consequences of sharing a bed with your husband?” Mr Knightley could hardly refrain from teasing her, a fond smirk dancing on his features.

“Well, we do not – very often, and I thought – oh, it is no matter now. Would you mind very much if it is a girl, though? That way, little Henry might have Donwell still, and not learn to resent his cousin in the years to come.”

He shook his head, covering her hand with his palm where it rested lightly upon the curve of her stomach. “Nonsensical girl – of course I should not mind a daughter, especially one as handsome and lively as her mother. But you must come to accept that, as much as I love our nephews and nieces, I shall not have them take precedence over my own flesh and blood if it can at all be helped.”

“Oh, but we cannot put my father through this again,” Emma objected in sudden agitation. “I do not think he could bear it.”

Mr Knightley sighed, and gathering her hand more firmly in his, raised it to his lips. “It would hardly be fair of him to deny you what your sister has been granted so readily. Unless, of course, you yourself decide you do not wish for more.”

“I do not know what I want,” Emma admitted with a shrug, and knowing her as well as he did, he could tell she was more than a little overwhelmed at the prospect of her impending motherhood.

“You will do very well, my dear,” he warmly reassured her, reaching to brush a stray curl from her brow. “Of that, I have absolutely no doubt.”

He was well rewarded by the blinding smile that suddenly lit up her beloved features. “A little Knightley of our own – can you imagine?”

“I’m sure I can,” he smiled back with uncommon tenderness, and let her press her lips to his hand in turn. “And I, for one, can scarcely wait.”

.

“I still believe we should name him Frank,” Emma insisted, half in jest, half serious. “When you think about it, we would not be here at all, if not for Frank Churchill.”

“I’ll thank you not to mention that scoundrel in front of my son,” Mr Knightley exclaimed in mock horror, gathering the precious bundle closer to his chest. “No child of mine shall ever bear his name, you may rest assured.”

“It is such a pity that our brother and sister had the advantage of several years over us, and therefore all the best names are already taken by our nephews.”

He looked down at his little son with more pride than he had ever felt in all his life. “There is one that has yet to be used,” he pointed out, adjusting the infant more comfortably in his arms. “My father’s.”

Emma nodded thoughtfully. “William Knightley. I like it very much. Now, if you would be so kind as to hand him back to me, Sir, for I am very eager to make his acquaintance myself.”

“You carried him for several months all by yourself, it is only right that I should get my turn,” he argued, even as he walked over to where she was propped against several pillows. The babe scrunched up his face, instinctively seeking his mother’s breast.

“I ought to send for the wet nurse,” she sighed, gazing down longingly at the fussing child. “He shall need feeding very soon.”

Somehow guessing at his wife’s dilemma, Mr Knightley frowned in sudden concern that he had been remiss in his duties as a husband. “Emma, you must know I would not begrudge you your preference, should you decide to tend to the child yourself rather than have him nursed by another.”

“I could not!” Emma protested immediately, though there was something indefinable to her tone. “It would hardly become the mistress of Hartfield and Donwell Abbey, as you can well understand.”

“I understand no such thing, my dear. How you choose to care for our son is no one else’s business, and I shall not hear another word on the matter.”

Emma’s features lit up in yet another of her dazzling smiles, and she promptly shooed him out of the room so that she might go about tending the babe in the way she preferred.

.

Harvest season demanded more of Mr Knightley’s attention than he would have wished for, now that he no longer resided at Donwell Abbey, and had a family of his own installed in his new home. On one such evenings he hastened down the familiar path to Hartfield to find a most unexpected sight awaiting him in the upstairs parlour.

Emma was fast asleep on the sofa, hair softly fanning her relaxed features where the maid’s careful work had come unpinned around her face and the delicate shell of her ears. In the armchair beside the fire, young William was sitting on his grandfather’s knee, gurgling and babbling in that manner particular to infants, as Mr Woodhouse lectured him at length on the dangers of drafts and the benefits of a healthful diet and exercise – in moderation, of course, as far as the latter was concerned.

“Oh, there you are, Mr Knightley,” his father-in-law greeted him as soon as he stepped into view. “I believe your son was beginning to miss you.”

With an easy smile he extended his arms to take the boy, who immediately set out to muss his cravat with such thoroughness that would surely have his valet in despair later on.

“I hope he kept you better company than his mother,” he quipped, turning a fond eye on his slumbering wife.

“Oh, sleep is very good for Emma, I would never dream of disturbing her,” Mr Woodhouse stated very earnestly, rising to take his leave of both Knightleys.

Mr Knightley took his usual seat at her side, and reaching one-handed to untie his cravat, allowed his son to steal it from around his neck. He would let Emma rest some more, and then he would wake her so that they might all three retire for the night.

#Emma (Jane Austen)#Emma (2009)#George Knightley#Emma Woodhouse#Henry Woodhouse#Emma/Knightley#aroace character#aroace-spec character#married life#pregnancy & parenthood#I wrote a thing#Dearest You Will Always Be (series)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On May 17th, in 1536, five innocent men were executed, accused of committing treason and adultery with Anne Boleyn.

George Boleyn, Henry Norris, Francis Weston,William Brereton, and Mark Smeaton were all beheaded, which was considered a more merciful death than the traditional punishment of being hung, drawn, and quartered.

George Boleyn

He made a very catholic address to the people, saying he had not come thither to preach, but to serve as a mirror and example, acknowledging his sins against God and the King, and declaring he need not recite the causes why he was condemned, as it could give no pleasure to hear them. He first desired mercy and pardon of God, and afterwards of the King and all others whom he might have offended, and hoped that men would not follow the vanities of the world and the flatteries of the Court, which had brought him to that shameful end. He said if he had followed the teachings of the Gospel, which he had often read, he would not have fallen into this danger, for a good doer was far better than a good reader. In the end, he pardoned those who had condemned him to death, and asked the people to pray for his soul.

Henry Norris

Loyally averred that in his conscience, he thought the Queen innocent of these things laid to her charge; but whether she was or not, he would not accuse her of any thing, and he would die a thousand times rather than ruin an innocent person.

Francis Weston

“I had thought to live in abomination yet this twenty or thirty years, and then to have made amends, I thought little I would come to this.” He then added that the people gathered should learn “by example of him.”

William Brereton

“I have deserved to die if it were a thousand deaths, but the cause whereof I die judge ye not. But if ye judge, judge the best.”

Mark Smeaton

“Masters, I pray you all pray for me, for I have deserved the death”

#george boleyn#william brereton#francis weston#mark smeaton#henry norris#anne boleyn#tudor era#long live the queue

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great Dust Heaps in the Kings Cross area sold to Russia: fact or urban myth?

By John Robinson

On the first floor of the London Canal Museum is a description of Victorian recycling which ends with the words, ‘a huge dust heap was cleared in 1848 to build the (Kings Cross) station’. That seems clear enough but is that actually all there is to the story?

A quick on-line search confirms the existence of several large dust heaps and an intriguing connection with Charles Dickens’ novel Our Mutual Friend and his character Nicodemus Boffin, the Golden Dustman, who became extremely wealthy, inheriting his own dust heap on the death of his master, and thought to be modelled on the real-life dealer in waste, Henry Dodd.

However, by delving a little further, I came across statements, put forward in seemingly reputable contemporary accounts, such as that in P. J. Pink’s mighty History of Clerkenwell (1880), to the effect that the dust heaps were sold to the government of Russia to help the re-building of Moscow after the war of 1812 with Napoleon! Similarly, a syndicated article that appeared in the Fife Herald on 17 May 1837 states, ‘it is a well-known fact that the dust-heap that was wont to grace the top of Gray’s-Inn-Lane is now a competent part of the city of Moscow, to which it was exported as a material for brick-making after the conflagration of that city’.

Figure 1 – The illustration above is an 1873 watercolour painting by E.H. Dixon of a dust heap located next to Battle Bridge and the London Smallpox Hospital and Weston Place, viewed from Maiden Lane (now York Way). An inscription below the painting inserted by an unknown hand, much later than the date of the painting, refers to the Great Ash Heap being cleared in 1848 to assist in the re-building of Moscow, Russia.

A giant-size dust heap

Coming from an engineering background, I feel the need to gain an approximate understanding of the sort of quantities of materials we are talking about. I have made an attempt to calculate the quantity, based on the Dixon watercolour shown in Figure 1 above and using the people and perimeter fencing shown in the painting as a scale. This suggests that there might be as much as 200,000 cubic metres of rubbish contained within this particular heap. If we assume conservatively that sixty per cent of this was composed of ash and clinker, that would give a quantity of material to be shipped of 120,000 cubic metres, enough presumably to assist with the rebuilding of at least part of Moscow. If we then assume that the volume of cargo that could be accommodated on a canal barge was 80 cubic metres, it would require 1,500 journeys from Kings Cross to Limehouse Basin. Allowing, say, five barge loads per day, it would require the best part of a year to complete the clearance.

The sale to Russia, if true, seems extraordinary and has some relevance to the Museum, as moving the considerable volume of material concerned would, no doubt, have involved loading the material onto barges at the most convenient point, possibly Battlebridge Basin, shipment along the Regent’s Canal to Limehouse Basin, followed by transport by sea-going sailing vessels across the North Sea, to the Baltics, more or less the reverse of the journey made by the ice consignments from Norway to Carlo Gatti’s ice storage warehouse in what is now the London Canal Museum.

The story appears to have aroused the interest of several modern researchers which I found in a wonderful paper compiled by the British Brick Society (2017) titled, ‘London’s Dust Mountains’. Much of what follows has been gleaned from this document.

Circumstantial evidence

What we know:

Much of the content of the dust heaps was ash and clinker from the fires that were needed in every domestic residence. These materials were used to make bricks, with the ash being mixed with clay, and the clinker used to keep the bricks separate and provide additional heat for the firing of the bricks. This material would, therefore, have been useful to anyone undertaking building work, even in a location as far away as Moscow.

Much of Moscow was destroyed by a fire in 1812, started by the Moscow police as part of a scorched earth policy to frustrate Napoleon’s forces sacking of the city. We also know that a 'Commission on Moscow Construction’ was set up in 1813 to coordinate the re-building activity, a plan for which was completed by 1817. The commission was disbanded in 1842. We know that the chief planner for the re-building works was a Scottish architect called William Hastie, confirming a British connection.

Russia had raised a large loan against its sovereign debt in 1822 of £3,500,000. Some of that money could have been used to purchase the dust heap(s).

There was a slump in economic activity in Britain after 1825 leading to a drop in the demand for building materials, which might have encouraged the owner of the dust heap to look for a market elsewhere.

A sea route from London to Moscow was feasible, with ships sailing through the North Sea and into the Baltic to St. Petersburg, entering the river and lake waterways where barges could have taken materials into the heart of Moscow. This route would only have been possible during the summer months when the waterways were ice-free. The alternative route, heading south through the English Channel, through the Bay of Biscay to the Mediterranean, and entering the Black Sea to the sea of Azov, east of Crimea and then overland, via the River Volta to the Moscow River, can most probably be discounted due to the number of transhipments required.

Hard evidence

As mentioned earlier, there were several dust heaps in the Kings Cross area. A huge dust heap, referred to as Smith’s dust heap, was located close to the junction of Gray’s Inn Road and New Road (now Euston Road). This was cleared in 1825/26 which would be consistent with the period of rebuilding in Moscow. Of this, Pink’s History of Clerkenwell states, ‘the corner of Gray’s Inn Road was covered in a mountain of filth and cinders, the accumulation of many years, and which afforded food for hundreds of pigs. The Russians bought the whole of the ash-heap, and shipped it to Moscow, for the purpose of re-building that city after it had been burned by the French’.

Another dust heap, that illustrated in Figure 1, was located close to the site of Kings Cross station and it would seem likely that its clearance would be necessary to make way for the construction of the station. An inscription below the painting inserted much later than the date of the painting, refers to the Great Ash Heap being cleared in 1848 to assist in the re-building of the city of Moscow, Russia. The date of clearance in 1848 would seem to be later than the period of rebuilding of Moscow. However, it is possible that rebuilding work continued following the disbanding of the Commission on Moscow Reconstruction in 1842. The date of clearance would be in line with the date of construction of Kings Cross railway station (1851-52).

But, there is a but…

An article in Slavic Review, ‘The Restoration of Moscow after 1812’ by A J Schmit (1981), makes no mention of the dust heaps being sold to Russia. It does, however, mention Catherine the Great’s ‘masonry city’ and the scarcity of building materials at the end of the 18th century.

Prior to the fire, except for some of the public buildings and churches, most of the buildings in Moscow were of timber construction. Soon after its inauguration in 1813, the Commission on Moscow Construction established brickworks and set about opening quarries. It seems likely that from the fire, it had plenty of ash to call upon, although it would seem likely that clinker was scarce, as the fuel used in domestic fires in Moscow would have been wood rather than coal.

Some buildings were reconstructed using brick construction, but many properties, both public and domestic, were reconstructed using split logs covered in plaster, both inside and out, to provide insulation against the harsh Russian winter and the heat of the summer.

To clear up this mystery, it ought to be possible to check the bills of lading or cargo manifests held by the Lloyds Register of Shipping. Unfortunately, it appears that such records are only available from 1837 onwards.

Conclusions

From the hard evidence provided above, it seems likely that one or more dust heaps did go to Moscow. However, unless further research on this subject is carried out to confirm the fate of the Kings Cross dust heaps, I am left with romantic dreams of the Golden Dustman flogging his dust to the Muscovites. But for those who like conspiracy theories, there is another possibility. The absence of a transparent audit trail appears to be reminiscent of money laundering, for which London appears to be Moscow’s (and the world’s) favourite laundromat.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tejumola Butler Adenuga

“Our family, Black and white.” For the slaveholding class of the old South, it was a familiar trope, one intended to convey both mastery and benevolence, to hide the reality of raw power and exploitation behind an ideology of paternalistic concern and natural racial hierarchy. There was profound irony in the white South’s choice of this image, for the words were far from simply figurative: They revealed the very truths they were designed to hide. One can see in the slave schedules of the 1850 and 1860 censuses the many entries marked “mulatto,” individuals the census taker regarded as mixed race, rather than Black.

This was the literal family produced by the slave system before the Civil War—children conceived from the sexual dominance of free white men over enslaved Black women in liaisons that ranged from a single encounter of rape to extended relationships, such as the decades-long connection between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings.

Few of these ties were ever acknowledged; white fathers held their own children in bondage, in most cases treating them little differently from their other human possessions. Of the many excruciating and all-but-unfathomable dimensions of American slavery, its manifold assaults on kinship seem among the most inhumane. What was the nature of “slavery in the family,” a designation that today seems both twisted and oxymoronic? How did individuals and families survive its emotional distortions and its insertion of racial subjugation into the most intimate—and precious—aspects of life?

The Civil War diarist Mary Chesnut, born on a South Carolina plantation, once famously remarked of this widespread denial:

The Grimkes of South Carolina were in no sense representative of the South’s slaveholding class. The decision of Sarah and Angelina, two daughters of the wealthy planter John Grimke and his wife, Mary, to confront the horror of slavery and move north in the 1820s to become abolitionists and feminists illustrates in its singularity the difficulties of escaping the grip of a system that compromised every white person connected to it.

Two of their mixed-race nephews, Archibald and Francis, sons of their brother Henry and the enslaved Nancy Weston, emerged as major figures in Black political and social life after the Civil War. They were embraced and supported by their activist aunts, who had not known of their existence during their early years of bondage, which included brutal beatings and abuse from their white half brother, another of Sarah and Angelina’s nephews. But the exceptional nature of the story—and of the individuals within it—casts into dramatic relief how the slave system could mold lives across generations.

John Grimke, the patriarch, sired 14 white children and held more than 300 enslaved workers on his extensive properties in the South Carolina Low Country and in Charleston. Sarah, his sixth child, born in 1792, displayed remarkable intellectual gifts from an early age, but such talents were not welcomed in a girl. While her father permitted her to teach herself using the books in his library, he denied her the education provided to her brothers.

Sarah described taking a “malicious satisfaction” in defying both her parents and South Carolina law by teaching her “little waiting maid” and numbers of other enslaved workers to read and write. When Sarah’s mother gave birth to her last child, in 1805, Sarah insisted on being named the baby’s godmother. Angelina would be her surrogate daughter.

From the April 2016 issue: The truth about abolition

Thirteen years apart, the two sisters came to share an abhorrence of the slave system on which their family’s wealth and position depended. Angelina was particularly repelled by the institution’s violence—the sound of painful cries from men, women, and even children being whipped; the lingering scars evident on the bodies of those who served her every day; the tales of the dread Charleston workhouse that, for a fee, would administer beatings and various forms of torture out of sight of one’s own household.

Both Sarah and Angelina became deeply religious, rejecting the self-satisfied pieties of their inherited Episcopalian faith, but finding in Christian doctrine a foundation for their growing certainty about the “moral degradation” of southern society. In 1821, Sarah moved to Philadelphia and joined the Society of Friends; by the end of the decade, Angelina had joined her.

Philadelphia was a focal point of the growing antislavery movement, and the sisters were swept up in the ferment. Soon defying Quaker moderation on slavery just as they had defied their southern heritage, the Grimke sisters embraced William Lloyd Garrison and what was seen as the radicalism of abolition. In essays appearing in 1837 and 1838, Angelina and Sarah each set out the case for the liberation of women and enslaved people.

They joined the Garrisonian lecture circuit, and Angelina developed a reputation as a sterling orator at a time when women were all but prohibited from the public stage. In 1838, Angelina married the abolitionist leader Theodore Dwight Weld in a racially integrated celebration that adhered to the free-produce movement, including no clothing or refreshments produced by enslaved labor. Weld and the sisters shared a household for most of the rest of their lives, and Sarah became a devoted caretaker of Angelina and Theodore’s three children.

Their opposition not just to slavery but to racial inequality and segregation, as well as their support for women’s rights, placed them in the vanguard of reform and at odds with many other white abolitionists. With emancipation, they took up the cause of the freedpeople, which they pursued until they died, Sarah in 1873, Angelina in 1879.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the sisters’ understanding of their family changed. Angelina came across a notice in an 1868 issue of the National Anti-Slavery Standard referring to a meeting at Lincoln University where a Black student named Grimke had delivered an admirable address.

She wrote to the young man to ask if he might be the former slave of one of her brothers. Archibald replied that he was in fact her brother’s son, offered details of his early life, and told her about his siblings, Francis, known as Frank, and John. Angelina responded that she was not surprised but found his letter “deeply … touching.” She could not change the past, she observed, but “our work is in the present.” She was glad they had taken the name of Grimke; she hoped they might redeem the family’s honor. “Grimke,” she wrote,

Thus began a relationship in which the Weld-Grimkes provided financial assistance to Archibald at Harvard Law School and Francis at Princeton Theological Seminary and delivered unrelenting exhortations to prove their excellence and worth, both as Grimkes and as representatives of their race. John, seen by his aunts as less talented and less deserving than his brothers, became estranged from his family.

Francis and Archibald achieved notable success—Archibald as a founder and vice president of the NAACP and later the American consul to Santo Domingo, Frank as a prominent member of the clergy and the Black elite of Washington, D.C. Relationships among the white and Black Grimke families were not always easy; Frank in particular found his white relatives oppressively demanding and “unaccustomed to the ways of colored people,” and after a time he declined to accept their support. But it seems telling that Frank nevertheless called his only child Theodora, and Archibald chose to name his daughter Angelina.

The remarkable story of the Grimkes was long neglected by historians, and the way it has come to be told reveals a great deal about how we have chosen to understand the past. Until the civil-rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s prompted scholars to look anew at the narrative of Black freedom, abolitionists were regarded as dangerous radicals, to be deplored rather than acclaimed.

The likes of Weld and Garrison, not to mention the women who moved outside their assigned sphere to join them in opposition to slavery, were cast as reckless fanatics, endangering the peace of the nation. But amid appreciation for mid-20th-century activists, perspectives shifted on those who had come before.

Abolitionists turned from demons into heroes, and their lives and struggles aroused widespread and sympathetic scholarly inquiry. Similarly, Black-freedom and women’s-liberation movements spawned new fields of Black and women’s history, making the Grimke sisters and their nephews a focus of exploration.

The fate of the first modern scholarly treatment of the Grimkes is illuminating. Gerda Lerner, who was a founder of the National Organization for Women and became a superstar in the nascent field of women’s history, wrote her Columbia doctoral dissertation on the Grimke sisters.

She published the study as a book in 1967, a moment when the civil-rights movement was well under way but the women’s movement was just emerging. She titled it The Grimké Sisters From South Carolina, with the subtitle, at her publisher’s insistence, Rebels Against Slavery instead of her preferred Pioneers for Women’s Rights and Abolition. “ ‘Women’s rights,’ ” her editor told her, “was not a concept that would sell books.”

By 1971, when a paperback edition appeared, the growth of feminism permitted the subtitle she had originally intended, along with a blurb from Gloria Steinem hailing the sisters as “pioneers of Women’s Liberation.”

Drawing on a flush of historical work that included scholarly biographies of the two nephews, Mark Perry in 2001 published a study that considered Black and white Grimkes together. His book explored the lives of “four extraordinary individuals”—Archibald and Frank as well as the sisters. Lift Up Thy Voice: The Sarah and Angelina Grimké Family’s Journey From Slaveholders to Civil Rights Leaders was unabashedly celebratory—designed to inspire a general audience by underscoring the possibility for racial enlightenment and for connections across the color line. “We see in their troubles our own,” he wrote of the family; “in their triumphs our hope; and in their history, the history of our nation.”

The Grimkes proved fodder for drama and fiction as well. In 2014, the novelist Sue Monk Kidd released The Invention of Wings, a tale that imagined the intertwined lives of Sarah Grimke and an enslaved girl presented to her on her 11th birthday. Oprah designated it a Book Club selection, declaring that it “heightened my sense of what it meant to be a woman—slave or free,” and it debuted at the top of the New York Times best-seller list.

The Grimkes’ story has served as a kind of cultural Rorschach test. We have projected onto it questions that have troubled us about ourselves and our racial past and found in it the promise of transcending the forces that seem to trap humans in the circumstances of their era.

We have, as Perry wrote, seen in it our own anxieties, hopes, and history: The sisters have represented the possibility of moral redemption and social transformation; their nephews have embodied the myth and reality of personal uplift as well as social conscience and commitment. All four defied the expectations and limitations of their origins. For more than half a century, as the rights of Black people and women have advanced, we have rediscovered and then lionized the Grimkes.

The latest addition to the Grimke literature marks a new departure. Greenidge’s The Grimkes is not a story about heroes. Instead, it is intended as an exploration of trauma and tragedy. Like the studies of the Grimkes that have preceded it, the book reflects the challenges of our own time, but Greenidge, who is an assistant professor at Tufts, regards these not with optimism about possibilities for racial progress but with something closer to despair.

She set out, she declares in her introduction, to write “a family biography that resonates in the lives of those who struggle with the personal and political consequences of raising children and families in the aftermath of the twenty-first-century betrayal of the radical human rights promise of the 1960s.”

Although earlier treatments hailed the sisters’ successes, Greenidge finds these vitiated by Sarah and Angelina’s unacknowledged “complicity in the slave system they so eloquently spoke against.”

Sarah’s “dissatisfaction was possible only because of the very privileges denied to the numerous Black people who cultivated her family’s cotton and maintained their household.” The “feel-good stories” of Archibald’s and Francis’s achievements have ignored “the superficialities of the colored elite” of which they became proud members, and have failed to call the nephews to account for their obsessions with skin color and class hierarchies in the Black community.

As the pastor of Washington’s Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church, Frank served a Black “professional, political, and business elite” that “shielded their congregation from the Black masses” by means of a rigorous admission process. Reverend Grimke “cultivated a conservative culture of racial respectability” that resulted, Greenidge finds, in the purge of “less well-heeled (and darker-skinned) members from Fifteenth Street’s rolls.” Archibald was unable to transcend his experience as a “fetishized Black wunderkind” during years spent in “neo-abolitionist New England”—at Harvard and as a young lawyer in Boston.

His service as the consul to Santo Domingo, often cited as a badge of remarkable accomplishment for one born in slavery, came “at the expense of the African-descended subjects living under American empire.” Greenidge mentions only briefly Archibald’s role in leading the NAACP’s Washington efforts to combat President Woodrow Wilson’s segregation of the federal government. But she notes disapprovingly that despite “his genuine belief in racial equality,” he “neither argued for racial revolution nor criticized the color consciousness, materialism, and social conservatism of his fellow colored elite.” Even as Archibald witnessed the steady escalation of Jim Crow, she contends, he remained too close to white society and white power to effectively resist it.

Greenidge is the author of an earlier, prizewinning study of another leader of the postbellum Black community, William Monroe Trotter, who had an often close but fraught relationship with Archibald Grimke. The two ultimately broke sharply over Trotter’s more radical, less accommodationist stance, disseminated through his paper, the Boston Guardian. Trotter, Greenidge writes, “provided a voice for thousands of disenchanted, politically marginalized black working people” for whom Grimke’s efforts in the “politically moderate camp of colored elite” had little significance. In Greenidge’s portrayal of this conflict, and in her broader interpretation, her allegiances seem clear.

Greenidge leaves the stature of Sarah, Angelina, Archie, and Frank diminished, but she offers an enriched view of the extended Black Grimke family. Foregrounding the nephews’ enslaved mother with a chapter of her own, she provides a valuable treatment of the free Black Forten family—the prosperous Philadelphia clan to which Frank’s wife, Charlotte, belonged—and highlights the crucial role of Black women in the abolitionist struggle.

A third-generation antislavery activist, Charlotte served as a teacher of the freedpeople in the Sea Islands, and her two 1864 articles on her experiences there made her the first Black writer to be published in The Atlantic.

From the May 1864 issue: Charlotte Forten Grimké’s “Life on the Sea Islands”

The Grimkes begins and ends with a portrait of Angelina Weld-Grimke, the only child of Archibald and his white wife and an often-overlooked figure in the Grimke lineage. Here she serves as an embodiment of the troubled legacy Greenidge seeks to portray.

Abandoned by her mother when she was 7, Angelina, who lived until 1958, became a writer, struggling as a mixed-race woman, a Grimke, and a lesbian to confront the realities and tragedies of race in her own and the nation’s heritage. Her best-known work is a play titled Rachel, centered on a brutal lynching that leads the victim’s daughter to decide she will never bring children into such a cruelly racist world.

Rachel became a “vehicle for civil rights activism,” but Greenidge emphasizes that the play also “reveals an artist who was as concerned with intergenerational trauma as she was with political protest.” Angelina’s life and work, Greenidge argues, gave expression to the failures—and the “existential rage”—of a Black elite whose narrative of “Black Excellence and racial exceptionalism” had rendered them politically “impotent” and “irrelevant” in the face of the violence of lynching and the imposition of Jim Crow.

At a time when we are confronted once again by an assault on rights long presumed to have been obtained and guaranteed—including voting and affirmative action—Greenidge has found in the Grimkes’ experiences a world chillingly like our own. Just as the promise of emancipation and Radical Reconstruction evaporated into Jim Crow, so we live, she writes, in an era when the heralded accomplishments of the civil-rights movement are being overturned and its promise abandoned. Upbeat stories of Black achievements cannot, she insists, counterbalance the wider reality of enduring oppression and inequality.

In recent years, considerable attention has been directed by scholars of history and literature to the question of slavery’s “afterlife,” to the assessment of its impact long after its legal demise. Greenidge embraces this perspective as she connects the injustices of the present with their roots.

She finds their origins embedded not just in the strictures of society and law, but in the human psychology formed in the families that racism has so profoundly shaped. Our nation’s racial trauma lives on. The arc of history bends slowly—or perhaps, Greenidge seems to suggest, hardly at all.

#american slavery#The Grimke Sisters and the Indelible Stain of Slavery#mixed race families#families with Black relatives during slavery

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Put On Your Raincoats | The Taking of Christina & Expose Me, Lovely (Weston, 1976)

Of the two villains in Armand Weston’s The Taking of Christina, Roger Caine has the showier part, seething malevolence and hair-trigger rage. Yet Eric Edwards gives probably the more interesting performance. Edwards can come across effortlessly as nice, maybe a little soft, and far from a forceful alpha male presence. He’s the one who tries to comfort the titular victim played by Bree Anthony after she’s been kidnapped by them and raped by Caine. Yet there’s a certain futility to his gestures. Those qualities which can make him a warm and likable presence elsewhere render him here a study in weakness, a man who may lack his partner’s mean streak, but also lacks completely in moral fibre in backbone. He’s fallen into Caine’s orbit and is unable to push back with any real forcefulness. His apologetic demeanour seems hollow and self serving.

The dynamic between them is a bit like that between Michael Rooker and Tom Towles in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, a feeling enhanced by the similarly banal milieus in which this is set. The theatre in which the heroine works. A dive bar where the villains pick up a pair of prostitutes (the always welcome Terri Hall and C.J. Laing), one of whom gets roughed up by Caine while Edwards apologetically pushes back. The snowed-in suburban houses, adorned by posters of Season Hubley and The Lord of the Rings. The film is draped in a certain moody style, thanks to the cinematography by Joao Fernandes (whose work I sadly found harder to appreciate thanks to the lousy transfer I watched), which creates a certain tension with the grim proceedings. It’s a quality foregrounded by this exchange between the protagonist and her boyfriend as they leave the theatre near the beginning of the film:

"What'd you think, honey? Did you like it?"

"It was too gory. I don't think they needed all that violence."

"But violence is what sells. People want to see violence."

"It made me feel a little sick."

"Well, you're too sensitive. You take things much too seriously. It's only a movie."

As a true crime thriller, this is mostly effective, and the final images, with blood spattered across the snow, have an undeniable impact. As porn, this is less so. I can concede that the scenes of sexual violence are appropriately ugly, but the consensual sex scenes, while more pleasant to sit through and shot in the same shadowy style, mesh uneasily with the overall tone of the movie. Trim those down and you have a very good movie.

Expose Me, Lovely, directed by Weston the same year as The Taking of Christina, is quite a bit more cohesive and quite a bit more fun. This is a porno inspired by The Lady in the Lake, and in particular, the earlier adaptation by Robert Montgomery. It’s been a while since I’ve read the novel and I’ve never seen the Montgomery film, so I can’t compare the different versions, but I understand it borrows the use of POV shots from the earlier movie. I also understand it uses them less pervasively, but I found it incorporated them into the overall visual style quite effectively, opting for reaction shots at well chosen times, and holding it all together with more atmospheric, shadowy cinematography by Fernandes. (The transfer I watched of this one was a bit more palatable.) One particularly thrilling scene has a foot chase that snaps between the hero’s POV and his grimy surroundings as he’s trying to flee a crime scene. The POV work does not feature too heavily during the sex scenes outside of the occasional blowjob (the female performers make eye contact with the camera), perhaps because it would have been difficult for the male lead to maneuver with a reasonably hefty film camera in front of him. One wonders how an adaptation of the story would have worked in the gonzo era, but one suspects such a movie would not have this one’s deliberate lighting choices and carefully considered movements. (Certainly Ultimate Workout was nowhere near as atmospheric, even if its opening scene played like a cheeky reversal of a slasher movie.)