#herbaria

Text

We're doing this one more time, since the first version only lasted a day! I'll reblog with an explanation of herbaria when it's done.

PLEASE REBLOG THIS WHEN YOU VOTE I want to have the largest sample size possible.

#herbarium#herbaria#plants#botany#herbaria my beloved#one time gubgam was looking for jobs and found the best paying herbarium job ever... at a golf course#mine#poll#3:35

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

For those who are interested

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

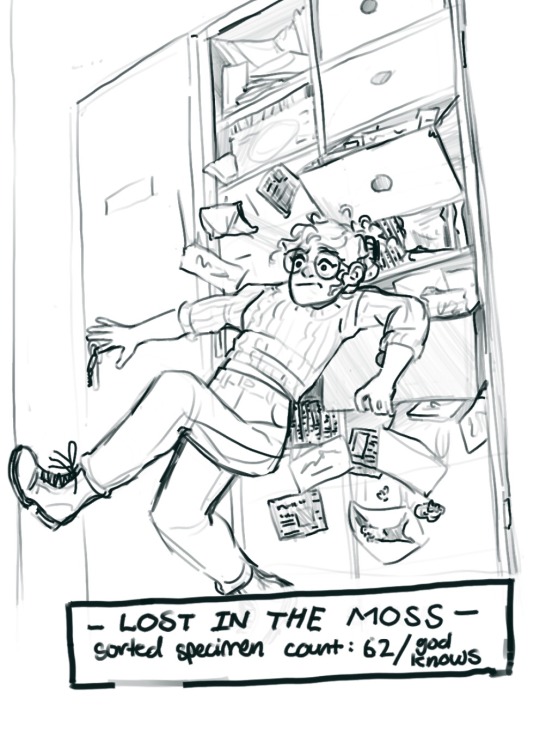

I got a job at an herbarium! Which means I have a 7 foot tall cabinet of mosses to go go through. Right now I’m just putting mosses into archival paper packets instead of the paper bags, newspaper, envelopes etc they were collected in. Favorite location has been “one block from the Masonic temple”.

The first 6 things I pulled out were not mosses.

#taking back the herbarium tag#herbarium#bryology#herbaria#botany#moss#lost in the sauce#lost in the moss#archive#herbarium curator

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rose Hip Monograph

View the rosehip monograph on substack, or alternatively on my blog.

This monograph is taken from my most recent blog post on how rose & rose hip can support us through this current astro-weather. You can read the entire post here: click me!

ROSE HIPS

Rosa Canina

#rose#rosehips#rosacanina#herbalmedicine#herbalwitch#greenwitch#holographicherbal#synergesticherbs#herbaria#astro-weather#astrology#substack#bloggersgetsocial

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Capparis sandwichiana, the Hawaiian Caper, or maiapilo, is a sprawling, low-growing shrub which inhabits only the Hawaiian islands in coastal and near-coastal ranges. It shares its genus with Capparis spinosa which is commonly used in Mediterranean cooking and shares some traits such as a preference for little water which might be surprising when hearing it is endemic to these tropical islands. The white flowers are fragrant and quite large, serving as nectar source for Manduca blackburni and a forage source for larval Plutella capparidis moths, both of which are also endemic Hawaiian species. The plant is threatened in the wild.

This image was created by pulling the sharpest segments from 62 separate images at different distances from the subject to produce an image showing the subject entirely in focus.

#capparis#hawaii#oahu#flora#postfloral#botanical#botany#herbarium#herbaria#seedpod#fruitdetails#nature#technical#photography

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

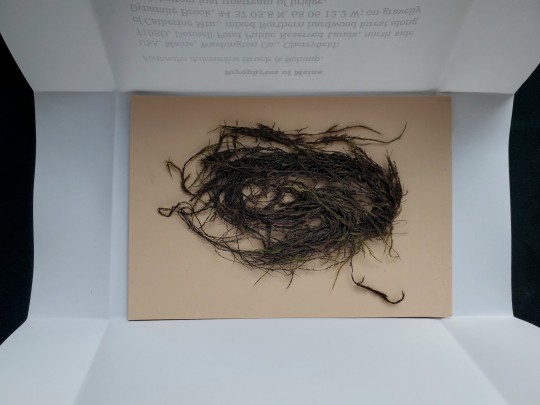

Quiet day in the herbarium...

Fontinalis dalecarlica specimen from Washington Co., Maine.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

··· ฬ E R B U N G ··· ⋮ ABOBOX II SELBSTANSCHAFFUNG @meinebackbox B A C K B O X - N O V E M B E R ' 2 2 # W E H N A C H T S B O X Natürlich dreht sich hier alles um Weihnachten & leckere Weihnachtsnaschereien! Folgende Rezepte sind diesmal dabei: # SCHNELLE PLÄTZCHENSTANGEN # CUPCAKES LINZER ART # WINTERKIRSCHKUCHEN # TANNENBAUM PLÄTZCHEN Dafür sind diese Zutaten in der Box: - Sternchen Ausstechformen in verschiedenen Größen von "Zenker" -Färbendes Lebensmittel Grün von "Eat a Rainbow" Unsere färbenden Lebensmittel sind eine wirklich natürliche Alternative zu herkömmlichen (Azo-)Farbstoffen. Die feinen Farbpulver werden aus farbintensivem Obst, Gemüse & essbaren Pflanzen hergestellt & sind somit auch vegan. Färbe Buttercreme, Zuckerguss, Schokolade & vieles mehr natürlich bunt. Entdecke unsere sechs Grundfarben, welche du untereinander mischen kannst um weitere Farbtöne zu erhalten. Für Sparfüchse sind unsere Farbmixe & Vorteilsboxen super attraktiv! -Weiße Zimt Crisp von "Schogetten" Weiße Schokolade mit Zimt-Crisp Stückchen & einem Boden aus Vollmilchschokolade. -Bienenwachstuch von "beeskin" Lebensmittel länger frisch zu halten war noch nie so einfach & sah noch nie so gut aus. - Edelkirsch von "Eckes" Seit Generationen steht ECKES Edelkirsch für Qualität & sinnlichen Genuss. Um diesen einzigartigen Geschmack erleben zu können, werden vollreife Früchte in handwerklicher Methode verarbeitet & nach traditionellem Rezept veredelt. So entsteht ein unvergleichlich köstlicher & feurig-fruchtiger Likör. Smoothies, Milchshakes sowie diverse kultige Mixgetränke wie Kirsch Royal, Edelkirsch-Sour & Edelkirsch Eiskaffee lassen sich mit dem süßen, herzhaften Likör zaubern. .... weiterlesen ... ... hier könnt ihr den ganzen Beitrag lesen: https://herzchentestet.blogspot.com/2022/12/b-c-k-b-o-x.html @dr.oetker_deutschland @zenker_backformen #meinebackbox #backmomente #droetker #zenkerbackformen #eckes #schogetten #beeskin #diamant #städterbackwelt #meinglück #herbaria #eatarainbow #insta #instafood #instablog #bloggerin #blogger_de #bloggerlife #foodporn #weihnachten #abobox #foodlover (hier: Wilhelmstadt, Berlin, Germany) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cl9LXOhtSG6/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#meinebackbox#backmomente#droetker#zenkerbackformen#eckes#schogetten#beeskin#diamant#städterbackwelt#meinglück#herbaria#eatarainbow#insta#instafood#instablog#bloggerin#blogger_de#bloggerlife#foodporn#weihnachten#abobox#foodlover

0 notes

Text

an offering for the cutest story with the cutest yams by @goldfishlover73

check it out ASAP ~

#yamato#the hidden herbaria in the leaves#fic rec#naruto must read#slice of life#office full of plants

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascinated to know if people have ever heard this word! Please reblog this - I am looking for data.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 exams in 6 weeks... i do not like this

#and i still haven't finished the two... herbaria(?) for them#plus a group project for which a don't have a group and idek where to start on it#and i only had one elective this semester! like i really need to step up my game or i won't have enough credits#oh and my id card is gonna expire in these 6 weeks so i need to somehow fit an appointment for that in my schedule#kinda related to that it's also gonna be my birthday soon. this is all just. a lot.

1 note

·

View note

Text

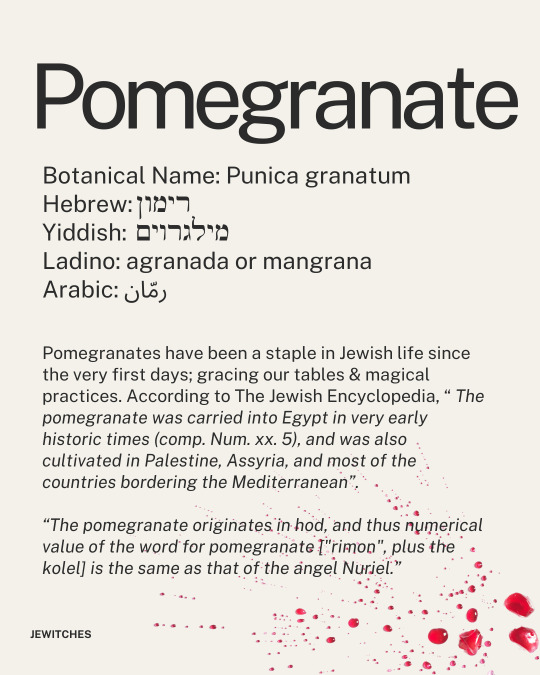

Oh, beloved pomegranate, how wondrous you are 🌿

We are quickly approaching pomegranate season in our part of the world; perfectly coinciding with the New Year which is approaching just as quickly.

Do you plan on ladening your Rosh Hashanah table with pomegranates? If you’re not Jewish, what is your cultural connection to the delightful pom? Share with us in the comments!

Side note: can you believe that there isn’t a pomegranate emoji? We need to do something about that!

This post doesn’t focus too much herbalism, but if you are interested in learning about pomegranates in that regard [particularly SWANA & Jewish connections], @rowanandsage offers that education over on Herbaria—And they currently have a discount for 20% off your first month with “RIMON”!* You can find it on rowanandsage.com

*We are not affiliated with Herbaria, nor is this an affiliate code! Just sharing the resource.

#jewish#jewitches#judaism#jumblr#jewitch#jewish magic#witchcraft#magic#witchblr#pomegranate#pomegranates

825 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bell Flower (Campanula Hortensis) 1750 by Georg Wolfgang Knorr (German, 1705–1761).

Hand-coloured etching and engraving.

Plate 162 from Thesaurus rei Herbariae Hortensisque Universalis.

Image and text information courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the seventh floor at Kherson State University, Oleksandr Khodosovtsev and Ivan Moisienko had a clear view of the enemy. It was a cool December morning, and the Russian troops that had occupied the Ukrainian city of Kherson since the earliest days of Moscow’s full-scale invasion had recently retreated east across the Dnipro River. Mushroom clouds hung over the horizon as they gazed through the rattling floor-to-ceiling windows of the botany department. The explosions, they thought, were likely coming from the tanks less than 5 kilometers away from where they stood.

That morning, the pair—both professors of botany—had arrived on the train from Kyiv and made their way through the partially ruined streets of Kherson to reach the university. The city was still being shelled, and to access their laboratory meant scaling a spiraling stairwell lined with stained-glass windows looking out over the Dnipro River, towards the enemy.

Their mission was to rescue a piece of history: the Kherson herbarium, an irreplaceable collection of more than 32,000 plants, lichen, mosses, and fungi, amassed over a century by generations of scientists, some from thousand-kilometer-long treks across remote areas of Ukraine. “This is something like a piece of art,” says 52-year-old Moisienko. “It’s priceless.”

Herbaria like the one in Kherson, a port city in the south of Ukraine, are about more than just taxonomy. They serve a vital role in the study of species extinction, invasive pests, and climate change. Though it's by no means the world’s largest—the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris has 9,500,000 specimens—Kherson’s herbarium is, Moisienko says, valuable because of its unique contribution to the field. Rare species found only in Ukraine, some of which are at risk of extinction, are documented on its shelves.

When Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine on February 24, 2022, they threatened not only the thousands of dried, pressed, and preserved specimens stored at the university, but the land where those samples had been collected. In the more than 17 months since Vladimir Putin declared his “special military operation” in Ukraine, millions of acres of land—about 30 percent of the country’s protected areas—have been maimed by indiscriminate bombing, burning, and military maneuvers. Russian troops have scorched tens of thousands of hectares of forests and put more than 800 plants at risk of extinction, including 20 rare species that have mostly vanished from elsewhere, according to the non-profit Ukraine Nature Conservation Group (UNCG).

The Ukrainian government estimates that a third of the country’s land has been contaminated by mines or other unexploded ordnance. Large swathes of the countryside could remain inaccessible for decades to come. That means it could be a long time before scientists like Khodosovtsev and Moisienko can go back out to collect samples.

The pair weighed up these considerations last fall, as they contemplated returning to the hollowed-out city of Kherson. Russian forces had been pushed out of the city in November but continued to bombard it. Between May and November, at least 236 civilians were killed by shelling, according to regional officials. Regardless, Khodosovtsev and Moisienko decided to go in.

“There is no need to risk anyone's life to save some equipment or a building,” Moisienko says, noting with passing remorse how he’d been pained to leave behind one of his prized microscopes. “For this collection, when it's gone, it's gone. There is no way to get it back.”

As the pair began mapping out the evacuation, they determined that in order to mitigate risk on the ground they needed to limit both the number of people and time spent inside the besieged city. There would never be more than three team members—Khodosovtsev, Moisienko and one of their two colleagues—on a trip, and each venture would last no more than 72 hours. The power grid went down regularly, and there was a citywide curfew of 4 pm, meaning they had hard deadlines to get in and out of their lab. And there was bureaucracy. “During the wartime, even to get around the country, you need to have some substantiation, like documents,” said Khodosovtsev, 51.

That got even more complicated when, on their first trek back to the university that December, they discovered that Russian troops had taken up residence in four of the rooms storing part of the plant collection.

Besides the deep sense of violation the botanists felt, this also posed a procedural problem. The “sitters”—a common expression for enemy soldiers who have occupied a Ukrainian building—had changed the locks on all but one of the doors, and the spaces now needed to be documented; a mandatory procedure typically carried out by the local police. Thankfully, their logistics team pulled some strings and got the process expedited. In just a few weeks, the locks had been changed again, and the rooms had been photographed for the official records.

In video footage capturing that first, largely fruitless trip, Khodosovtsev can be seen celebrating the return of one of the 24 more valuable boxes with a kind of enthusiasm typically reserved for the football pitch. “Collemopsidium kostikovii is saved!” he cheers as he raises his fist over his head. “To the sound of explosions!” he adds, as the rumble of mortars interrupts his brief moment of self-congratulation.

Limited resources, another knock-on effect from the ongoing conflict, also threatened to upend the men’s carefully laid plans. While Moisienko drove around to dozens of Kyiv’s home hardware stores in search of plastic boxes to transport the collection’s vascular plants, Khodosovtsev returned to Kherson equipped with little more than a headlamp strapped across his brow and a backpack filled with the same household tools you might use to move apartments.

On this second trip, the magnitude of the task became clear to Khodosovtsev. He had 700 boxes to evacuate. On his first incursion, it had taken him 15 minutes—and way too much tape—to wrap, stack, and rope together half a dozen boxes of samples. At this rate, the botanist said, he’d be blowing past the three days earmarked for this section of the herbarium. Never one to be discouraged, the scientist settled into familiar territory and began doing what he does best: calculating.

“Just two wraps of sticky tape and one roll of rope,” he said, beaming as he reveled in how he’d managed to shave his box-stacking time to just “three and a half minutes.”

This kind of methodical precision proved to be a helpful distraction from the realities of what was going on just beyond the paned glass. A mere 24 hours before Moisienko returned for his third and final trip on January 2, he learned the building where he planned to scoop up the last portion of the herbarium was hit by shelling. Instead of this news derailing his mission, it only seemed to harden him. “We are focused on [the herbarium] so much that you just ignore everything, all these shellings that [are] going on around you,” he said.

Even so, as he worked methodically, packing plant after plant, he started to contemplate how the glass windows of the lab could become deadly projectiles if a shell went off nearby; and how far it was down to the ground floor. At eight stories tall, the academic building sticks out. “The chance the Russians would hit the university building [was] really high,” he says.

He tried to treat the nearby rumbling as white noise, though one day, a shell landed just outside the window as he was packing a sample.

By January 4, Moisienko had finished loading up the last boxes of the collection into the back of a truck. It traveled west for nearly two days, covering approximately 1,000 kilometers, before reaching Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University in Ivano-Frankivsk in Western Ukraine, the institution that has served as a university in exile for the staff and students of Kherson State University for more than a year.

It’s a kind of safety. But, as Moisienko points out, only as safe as anything or anyone can ever be in a country where missiles fall out of the sky on a near daily basis. “Nowhere in the country is 100 percent safe,” he says.

On January 11, Kherson State University was once again struck by shelling, this time only blocks away from where Moisienko had been working less than a week earlier. “That building remains [in] danger, and it's still dangerous to be in Kherson as it’s shelled still now on a daily basis,” Moisienko says. “We've done the right thing.”

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Absolutely frothing at the mouth about the Duke herbarium. To move all 800,000 specimens in 3 years would mean shipping 730 A Day ON ICE at a specific temp! and that’s assuming you can find herbaria that can take a significant amount of samples! You have to have special paperwork between each herbarium just to send duplicates never mind rare or extinct plants or the specimens an entire species is based on

There are about 3,000 herbaria GLOBALLY. Every herbarium IN THE WORLD would have to take 266+ specimens. We aren’t talking little pieces of paper it’s thick archival cardstock you have to carry with both arms for the plants

That’s several shelves. For lichens and moss that will include rocks, for fungi they have cardboard boxes for each.

When I was just repackaging mosses I’d be lucky if I got 30 documented sorted transferred and put away in 3-4 hrs.

Some of their collections are over a hundred years old I would hate to TOUCH one of those let alone ship it

Screaming crying throwing chairs etc

31 notes

·

View notes