#godfather auteur

Text

The Two Auteurs in a nutshell

Auteur: If you see me talking to myself, go away! I’m self-employed and we’re having a staff meeting!

#doctor who#doctor who expanded universe#dweu#faction paradox#arcbeatle press#godfather auteur#auteur#incorrect quotes#book of the snowstorm#book of the snowstorm spoilers

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Garyshots's Godfather Lieutenants's physical appearance idea from the forums.

#faction paradox#house paradox#book of the war#garyshorts#doctor who#granfather paradox#godfather lieutenants#auteur#bbc doctor who#dr who#whoniverse

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay no for real this whole idea of Goncharov is very funny but get your fuckin’ timeline right, okay.

Martin Scorsese had made exactly two movies by 1973, he didn’t have the cachet to make a big budget or even mid budget crime movie about the Naples mafia. Certainly not the greatest mafia movie ever made! Further, he hadn’t yet developed his filmmaking style, let alone his fascination with the criminal underworld, and The Godfather had just come out the year before, so there wasn’t even time to get used to the romantic portrayal of gangsters that Scorsese’s films would act as revisionist responses to! The conversation had barely even started yet!

And then there’s the actors: Robert De Niro was a working actor then, not a huge star — he’d been in a few movies by then, including three from noted trash sommelier Brian De Palma and one from even more noted trash auteur Roger Corman — and he actually worked with Scorsese and Keitel that same year in Mean Streets! He got some acclaim for that performance but it wasn’t like, Godfather level, y’know? Not in terms of fame or notice at least. And Pacino? Pacino’s first major role was The Godfather the previous year! That was his third film ever! He did Serpico in ‘73! He hadn’t even done Dog Day Afternoon yet! And he didn’t work with Scorsese until The Irishman, which came out in 2019!

Really, y’all, what you’re imagining, the movie you’re all spinning out of thin air here, probably came out in like, 1983, not ‘73. Probably in place of Scarface or something (which for my money would be an improvement). You’ve got De Niro post-Deer Hunter and Taxi Driver, he’s worked with Scorsese before, you’ve had two excellent Godfather films to build a mythology of the romantic gangster around for Scorsese to play with. You’ve got Pacino after shit like Serpico and Cruising, he’s in his prime. You’re still pre-Goodfellas for Scorsese, so he hasn’t gone sicko mode yet, but he’s done great movies that got noticed and he’d be able to pick up a budget and a production company to go to Naples. He’s worked with big studios, he’s got some clout. Now is the time for Goncharov!

But nooo, all this happened before you were born so it’s all vague and nebulous “before-times.” What’s the difference between 1973 and 1983? Who cares? Well I do! And now you know! History matters okay!! Learn ya history!!!

#goncharov#the new hit tumblr meme that actually hits me where I live#sorry mr. keitel that I did not dig into your career more#always left out of the conversation in favor of the big names#next time I have the opportunity I’ll watch reservoir dogs sir

756 notes

·

View notes

Text

Father of Goncharov: "Pietro" JWHJ0715

Though the Anglophone world owes a debt of gratitude to Martin Scorsese for presenting Goncharov outside of Italy, in truth he cannot be considered more than its godfather. Too often the work of Matteo JWHJ0715 has been overlooked, including by this author. But less discussed still is the profound influence on Goncharov of Matteo JWHJ0715's father, P1229L "Pietro" JWHJ0715, who Matteo himself called "the father of Goncharov".

Little is known of P1229L JWHJ0715's early life except, crucially, that he immigrated to Italy from a place that would later be part of the Soviet Union, in search of a better life. He began going by Pietro very soon after immigrating; Italians found his birth name difficult to pronounce, and their cars didn't have enough room for so many characters on their license plates.

Pietro JWHJ0715 worked a series of odd jobs in Naples. The circumstances under which he met his future wife, Mattea Catalano, are not well known, though it is certain her family disapproved of the match, and sidelined Mattea until well after her son found acclaim in the film industry.

The common story of Pietro himself entering the film industry after seeing a young Matteo's fascination with Sunday matinees is most likely a romantic fabrication. When Matteo was still quite young, Pietro JWHJ0715 had already become the first license plate to work in the Italian film industry.

Though no photographs of Pietro survived an infamous JWHJ0715 family house fire, he probably looked like this Italian license plate of the time:

Matteo JWHJ0715 has spoken at length about the profound influences of his family on the making of Goncharov, and we know Pietro was extremely proud of his son's achievements, both as an individual and on behalf of all license plates in Italy--long before the auteur Italian license plate became almost a stereotype in film history.

Sadly, Pietro JWHJ0715 did not live to see Goncharov's tremendous commercial success. But several months before dying of rust complications, he enjoyed a private screening with Matteo and some of the crew, and is said to have been moved to tears.

At the 1973 Cannes Film Festival, Matteo JWHJ0715 gave a moving tribute to his late father, lauding him as "a father to me, and in truth a father to Goncharov as well". Pietro is also memorialized in a prestigious film scholarship for Italian students, a scenic boulevard in Naples, and, interestingly enough, a vanity license plate in New Jersey, which also honors that state's Italian heritage.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Book of the Snowstorm – Readthrough/Review Part 4

Framing Story (Scene 9-11)

Still fun, nice linking of the Ties that Bind and Buggy Little Holiday as part of Coloth’s quest and separate from the bibliomancy of Martisa and Callum. Still suspicious of the cloaked figure. Also confirms the Toymaker from Abstract Tales and the Celestial Toymaker’s names are connected which is fun.

The Ties that Bind

Nice short little piece, not familiar with the setting but found the mismatch of real modern culture and fictional future culture fascinating. Violet and Mimi seem sweet too. Not very long but it also didn’t really need to be to accomplish what it was trying to accomplish.

A Buggy Little Holiday

Notably, this is one of James Wylder’s contributions to the anthology. Fun piece, Cleo was awkward in an endearing way and Havoc was trying really hard to act all serious and that dynamic was fun. Simple plot but it works, though I’m curious what exactly Cleo and Tophie are looking for.

Two Auteurs

And following on with this we have the editor and writer of the framing narration. Aristide Twain.

Oooh boy is this a monster.

Ok, start from the top.

Nightmare Before Christmas imagery in Seventeenth Auteur’s world, at least that’s how I read it.

The Celestial Toymaker is a Time Lord, at least according to this story. One that Auteur knew too. In addition to namedropping The Monk from the Bloodletters as ‘Mortimus’ and a ton of Auteur lore.

So, rundown from what I could tell.

Twelfth Auteur -> Goddess of Gendar

Thirteenth Auteur -> Various, including Noel/Santa, Astrolabus and others

Fourteenth Auteur -> Godfather Auteur

Fifteenth Auteur -> The Remembered Auteur

Sixteenth Auteur -> The Retconned Auteur

Seventeenth Auteur -> The Monochrome Auteur, the one devoured by the Bookwyrm

The Goddess bifurcated in the story, becoming like the Fourteenth Doctor… I think. Noel/Santa also appeared on the planet as a Thirteenth Auteur, only both Twelve and Thirteen agreed to never become Auteur, and also Seventeen excising Twelve from his past and denying the existence of Noel/Thirteen.

It’s all a bit confusing but in a fun way, also like the Goddess poking fun at Monochrome for all the self inserts and retconning he’s tried to do.

Loved the use of the mindbending match though, between Forgotten Lives 3 and Two Auteurs I've been loving how mindbending's being depicted in recent releases

Gonna have to ask a lot of questions about what exactly happened in this story, but needless to say I greatly enjoyed it.

#dweu#doctor who eu#doctor who#thebookofthesnowstorm#the book of the snowstorm#arcbeatle press#coloth#doctor who expanded universe#faction paradox#well#faction paradox adjacent#starlight endeavours#starlight ranger#auteur#goddess of gendar

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think it is final time for me to be cliche and announce my Spidervers OC.

Mother Spider. The Spider person of Earth 5556 (also know as the Doctor Who Universe) (I would like to stress Loves are definitely Marvel Canon not Just Doctor Who Canon as they have been mentioned in a source as recently as 2019)

I wrote a Spiderverse introduction to them

My name was PetradvoraParkerrallonder I was Bitten by a Radioactive Enemy Rep and for the past 50 years I have been the Eleven-Day-Empires one and only Mother Spider. In my time I have seen the destruction on the Plant Leth and watch the fall of Utterlost, I have done battle against the agents of the Great Houses and gazed into the eyes of the Celestis. My past is so messed up due to my own temporal alterations to it.

As well as a Book of the War entry for him

Spider, Mother | Faction Paradox Participant

Loomed in the Homeworld exactly 200 years before the war in Heaven as a full grown adult under the name of PetradvoraParkerrallonder, they claim to have gone out Drinking with the Grandfather Paradox this is almost definitely a lie to make a very dull boring life as a member of the House ceremonial Guard seem more Interesting. They claim to have been present during the First Battle on Dronid at the day the war started and whilst fighting they where bitten by a radioactive Enemy Rep. this is also probably a lie however it does explain their strange relationship to causality and their ability to subtly shift elements of their simply by believing it to be true. However they gained this ability they also gained more vulgar abilities such as the ability to climb up war and enhanced strength neither particularly impressive powers. Soon after they where recruited by the infamous Faction Paradox member Godfather Auteur and soon after completing their stint as a Little Sibling they gained the rank of Mother due to being of Homeworld Stock and took the name Spider in reference to their abilities and their choice a Shadow Weapon (a kind of pro tactical weapon which creates a web like strand allowing them to swing from wall to wall). Whilst in the Faction they have claimed to be present at both Leth and Utterlost this are probably also lies, as are their claims to have defended the Eleven Day Empire from costumed agents of the Great Houses. They are a consummate lie and despite calming knowledge of a Multiverse which can effect the universe of the Houses they have shown no evidence of it, any and everything they say should be treated with suspicion.

#doctor who#faction paradox#dweu#doctor who eu#across the spiderverse#spiderverse oc#the book of the war

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOR THE LAST TIME! MARTIN SCORSESE DID NOT DIRECT GONCHAROV!

I wrote all of this on a reblog of a great post by @mortalityplays that explains how Twitter’s broken copyright protection system is finally letting the world appreciate the up-til-recently lost film “Goncharov,” but it was a reblog, so I don’t think enough people are seeing this. And honestly, it’s just like tumblr to go hog wild on a media property without knowing even a scintilla of the actual history of it.

I know that Martin Scorsese is getting a lot of love for tumblr’s favorite new rediscovered film, but (and I can't believe I have to fucking go all filmbro on this, but I fell down a hyper-fixation rabbit hole on this a while back) what's pissing me off about all of this, is that everyone, including op, keeps giving Martin Scorsese credit as the director, when the title card clearly shows "Martin Scorsese Presents" (I think it's the snippet in the 3rd tweet, maybe the 4th) which means that Martin Scorsese was the DISTRIBUTOR.

Like. Ok, so Scorsese graduates film school roughly the same time as George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, Brian DePalma, and the rest of the Movie Brats, coming up with Steven Spielberg etc, launching the American auteur era of film, but smack in the middle of research for Mean Streets, Scorsese encounters this film by the mononymic Italian director, Matteo (JWHJ0715 was his member id number in Italy's version of the Director's Guild of America - pretty sure they stopped requiring directors include their guild number in the credits after Fellini refused for like 20 years and they just gave up trying to fine him. This is also what inspired Lucas to cow the DGA into submission on the credits at the end thing for Star Wars).

And Scorsese is just fucking blown away. Like, it's everything he's wanted to do since he went into film school. The symbolism, the interpersonal intrigue, the conflicting loyalties between love, honor and duty, the family you are born into vs. the mafia family that finds, accepts and trains you, the constant ethical tension between doing what's right for your morality and what's right for YOUR family vs. what's right For the Family.

I mean. Jesus, look at Goodfellas if you want to see how Scorsese tries to touch on SOME OF THAT when he finally feels like he knows enough to even attempt to approach Matteo's mastery.

Of course, that's not even touching on the Cold War intrigue about the Russian mob operating outside of Soviet Russia and the whole KGB subplot aspect of it all.

Anyway, so back to 1972. Scorsese is just absolutely blown away. The Godfather has just come out and America is mafia mad! Scorsese has had some modest hits. He thinks that Mean Streets is gonna be his big break, and he sees this movie. Not only does he dump his original lead actor to cast Robert Deniro because of it, he decides that he's gonna use the connections he's been making to get this film in front of American movie goers, to help finance the films he wants to make.

So he just, he just fuckin COLD CALLS Dominico Procacci and says "I know people and I can get this movie seen over here" and Procacci takes the meeting... Like, the balls on Martin!

But Procacci doesn't tell him that the real Russian mafia is already sniffing around. Anyway, Scorsese gets the distribution rights for the US and starts getting prints made and ready to distribute to prop up the mob-movie-fever so he can ride it when Mean Streets hits later in the year.

Like, the film was already in cans and at the theater, when the Russian mob knocks on Marty's door and have a very convincing conversation with him.

Next thing you know, all of the prints are back at the warehouse where, reportedly, the fucking Russian mob counts each and every single one. Then they toss the fucking master on the pile (I don't know where they got that, does anyone have that story??) and set it all alight, while Marty watches his future go up in flames.

But then they just fucking walk away and Martin Scorsese, with britches full, goes back to his car and doesn't even see the bag of cash in the backseat until the next day. Business concluded.

Gotta give Old Ivan credit. Just like Matteo depicted - they keep their fucking word. Martin Scorsese decided to stick to the Italian and Irish mobs in his movies from then on, and leave the god damned Ruskies alone.

Of course, none of them knew about the test prints back at the warehouse of the company that was hired to make the copies for American distribution. I could be wrong, but isn't the leading theory about the provenance of the Twitter copy that someone probably found one of those test prints in some corporate asset auction or something?

Anyway, sorry for the ramble. I just hate seeing Matteo getting left out of the fucking conversation, especially now that arguably his greatest work is finally getting attention.

Scorsese has been basically fanfic AU-ing "Goncharov" his whole fucking career and now he's gonna get actually credit for the original? Not on my fucking watch, thank you.

#goncharov#martin scorsese#matteo#matteo jwhj 0715#robert deniro#unreality#russian mob#mafia#naples#Dominico Procacci#long post#goncharov meme

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

Clari!! I’m also a film fan + mafia/noir fan and I would love to receive some mafia (or perhaps other genre) film recs from u! I watched goodfellas and true romance after u mentioned them n I really loved them <3 so preferably smth similar vibes!

I hope you are having an amazing day & drink lotsa water! You’re amazing c:

oooh anon!!! omg two of my absolute fave films <333 okayokayokay let’s chat film under the cut!!

okay, so you’ve probably already seen them, but i have to mention the godfather part one and the godfather part two just in case!!! we also can’t talk about gangster films without mentioning the holy trinity from the thirties: the public enemy (1931), little caeser (1931), and scarface (1932). other gangster film recommendations:

casino (1995) (ROBERT DE NIROOOOO oh my god he’s so Daddy in this i’m drooling just thinking about it)

scarface (1983)

the departed (2006)

touch of evil (1958)

i also highly suggest watching the sopranos, which has absolutely incredible writing and quite literally changed television and writing for television. it’s definitely a commitment since it’s quite long, but it’s a must-watch if you’re into gangster media, especially mafia.

marty (scorsese) is a true auteur in the sense that he literally makes the same film over and over and over again—which is to say, his films all contain a specific set of elements that he uses in slightly different ways to tell slightly different stories, so if you enjoyed goodfellas and you watch casino + the departed and like those, too, then it might be worth it to check out some of his other films. i absolutely love the wolf of wall street, and while it isn’t exactly ‘gangster’/mafia it does obv encompass elements of organized crime (and drugs!!!!! and extremely flawed characters!!).

in terms of vibes when it comes to true romance, i’d suggest checking out literally any of tarantino’s other films but reservoir dogs and pulp fiction in particular, since they 1. contain/center around organized crime in some way and 2. were written around the time he wrote true romance, so the writing + characters are very similar in terms of style. there’s also natural born killers, which isn’t great but it was also written by tarantino around this time as well and contains similar elements, too. other films that may peak ur interest:

wild at heart (1990)

kiss kiss bang bang (2005)

bonnie and clyde (1967)

gun crazy (1950)

breathless (à bout de souffle) (1960)

i hope these help anon bb and i hope you find some more films that u love!! happy watching <3

#i love love love *almost* all of these films#also if ur a fan of my bmb then u will loooove mia + vincent in pulp fiction#my sibling is obsessed with the sopranos they've watched it SEVERAL times#which is like;;;;; so many hours of their life LMAO but anyway#pls enjoy these!!!!#and have a fabulous tuesday <3#inky.bb#clari gets mail

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

(LONG POST) Being a piece from the New Yorker, this essay takes several paragraphs before it finally gets around to the main point. #refrigeratormagnet

David Zaslav, Hollywood Antihero

The C.E.O. of a conglomerate that includes Warner Bros. studios, CNN, and HBO takes on an entertainment business in turmoil.

By Clare Malone, August 23, 2023

In 1941, a couple from New York bought an undeveloped parcel of land in Beverly Hills for fourteen thousand dollars from the writer Dorothy Parker, the most fearsome wit at the Algonquin Round Table. James Pendleton, an interior designer and art dealer of Regency and Baroque pieces, and his wife, Mary Frances, who went by Dodo, craved a particular vision of California living. They imagined a landscape of eucalyptus trees and rose gardens, with a pool house suitable for high-life entertaining—a Xanadu escape from their place in Manhattan. The Pendletons enlisted the architect John Elgin Woolf, who designed homes for Cary Grant, Lillian Gish, Barbara Stanwyck, and Errol Flynn, to create a one-level house—Dodo had a bad hip—in a coolly sumptuous style that would come to be known as Hollywood Regency.

In 1967, Pendleton sold the house to Robert Evans, who, as the head of Paramount Pictures, went on to oversee a string of era-defining films: “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Love Story,” “The Godfather,” “Serpico,” “Chinatown.” Evans led a life worthy of a film auteur’s attention—glamorous, accomplished, and more than a little sleazy. When he bought the house, which he called Woodland, he had been married twice; he would marry five more times. He became almost as well known as a host as he had been as a producer, throwing bacchanalian parties and entertaining such stars as Dustin Hoffman, Jack Nicholson, and Roman Polanski. In the nineteen-eighties, an addiction to cocaine and an association with a tawdry murder case helped bring his career, and the parties, to an end.

Evans died in 2019, at the age of eighty-nine. Three months later, a media executive named David Zaslav bought Woodland for sixteen million dollars. Though Zaslav was one of a select group of people who could afford this Hollywood palace, he was not part of the town’s aristocracy. Zaslav was then the C.E.O. of Discovery, Inc., the cable corporation whose channels included HGTV, TLC, Animal Planet, Food Network, and the Oprah Winfrey Network. At the time, his greatest claim to fame was the size of his paycheck. In 2014, he was the country’s most highly paid executive, with compensation of a hundred and fifty-six million dollars, mostly in stocks and options. Zaslav, whose teeth gleam a startling white and whose wardrobe skews toward Wall Street leisurewear—logoed golf shirts and zip vests—had a reputation as a shrewd dealmaker, adept at brokering acquisitions. Discovery was something of an entertainment-industry backwater, known for a portfolio of low-cost, lowbrow, highly profitable programs, of the kind you don’t tell co-workers you watch: “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo,” “Wives with Knives,” “Naked and Afraid.” Zaslav, a lifelong New Yorker, had never been involved in managing a Hollywood studio, but he seemed to like the idea of the town. “David has always been on the outside looking in on the content world,” a former Discovery executive told me. “He’s always wanted to be a player in Hollywood.”

In May, 2021, a year and a half after Zaslav purchased Woodland, he was announced as the C.E.O. of a new media company, Warner Bros. Discovery—a vast conglomerate that melded Discovery’s holdings with those of WarnerMedia, which encompassed HBO, Warner Bros.’s film and television studios, CNN, and a suite of cable channels including TNT, TBS, and Turner Classic Movies. Zaslav, the sixty-one-year-old head of a middle-market cable company, had suddenly achieved a cultural reach beyond what the likes of Robert Evans could ever have imagined. “Whoa—the minnow swallows the whale,” the former Discovery executive recalled thinking.

Under Zaslav, W.B.D. adopted a new slogan, “the stuff that dreams are made of”—an evocation of Hollywood glory borrowed from “The Maltese Falcon,” a hit for Warner Bros. in 1941. But Zaslav joined the movie business at a bracingly inglorious moment. The advent of streaming video has demolished old business models. The unions that represent the industry’s actors and writers are carrying out a bitter and prolonged strike. And the company that Zaslav has ended up leading is an ungainly entity, stuck with colossal debts.

Zaslav has said that he is focussed on the long term—a sensible position, since he’s made a pretty rough first impression. As soon as he took over W.B.D., he began slashing costs and laying off hundreds of workers. Last August, he scrapped a Scooby-Doo movie and a ninety-million-dollar Batgirl project, both nearly complete, and wrote them off for tax purposes. (W.B.D. justified the decision as “a strategic shift.”) On the picket line, actors and writers point not just at his compensation package—valued at two hundred and forty-six million dollars in 2021, the year he brokered the W.B.D. deal and extended his contract—but also at his seeming interest in playing mogul while the entertainment business implodes.

For many, Zaslav is something of an antihero, at the center of the town’s story for all the wrong reasons. Those in what one insider half-jokingly calls “the Hollywood deep state” seem unsure that he is up to the task of building a new entertainment-industry power under difficult circumstances. Even Zaslav’s supporters describe him as an outsider feeling his way along. “Notwithstanding David’s long and distinguished media career, he is a relative newcomer to the motion-picture environment,” said Alan Horn, a former president and C.O.O. of Warner Bros. and chairman of Walt Disney Studios, who has been hired as an adviser to Zaslav. “That generated a lot of scrutiny, and it can take a while to be accepted.”

The deal that created W.B.D. was, like many mergers, a marriage of convenience. A.T. & T. had bought Time Warner in 2018, as part of an attempt to expand into the entertainment industry. This was a radical departure from A.T. & T.’s traditional business, but the company was eager enough to open new markets that it was willing to pursue an eighty-five-billion-dollar acquisition and to fight off an antitrust suit from the Department of Justice. Three years later, it was equally eager to get out.

John Malone, Zaslav’s longtime patron, is widely considered a principal architect of the deal. A former cable magnate who was a powerful owner of Discovery, Malone is eighty-two years old, worth around nine billion dollars, and seen as one of the most formidable minds in business. The W.B.D. transaction, a Reverse Morris Trust, is a hallmark of his dealmaking: a complex maneuver in which a company spins off a subsidiary to its shareholders, then immediately sells it to another company, which forms a new entity in which the shareholders have majority control. A.T. & T. shareholders retained seventy-one per cent of the stock in W.B.D.; this exchange, executed by high-priced bankers and lawyers, prevented them from incurring capital-gains tax. Malone owns less than one per cent of the stock, but sits on the board and remains enormously influential. (Advance, the parent company of Condé Nast and The New Yorker, is one of the largest shareholders in W.B.D., with around eight per cent of the stock.)

Discovery didn’t really have the money to make the acquisition outright. A former media executive characterized it as a leveraged debt buyout, which is “unusual in the media business, because the media business is so volatile.” But the deal left the new company with substantial handicaps: Discovery, which was already carrying fifteen billion dollars of debt, went further in debt as it made a huge payment to A.T. & T. Thus, W.B.D. was born more than fifty-six billion dollars in the red. In order to keep his company intact, Zaslav would have to use its cash flow to pay down that debt. The former media executive told me, “The key is, in the next two to three years, can David pay off enough debt that he emerges with a viable business?”

The media industry is a seascape of big fish prowling for slightly smaller fish to eat. W.B.D.’s creation was Discovery’s bid to “scale up,” combining assets to compete with such streaming entities as Netflix and Amazon’s Prime Video, which have spent a decade enticing customers to cancel their cable subscriptions. The truism is that only the largest firms will survive in the post-cable world of streaming, which demands endless content. Traditional media companies have launched their own streaming services, but it’s been difficult for them to make scores of new movies and series while their once-reliable cash flows dwindle. Expensive cable subscriptions are quickly becoming obsolete. Advertising, too, has been lost to Big Tech, as Facebook and Google Ads have come to dominate the market.

Zaslav likes to tout W.B.D.’s vast library: “Harry Potter,” “The Lord of the Rings,” “Superman,” “Batman,” “Friends,” “Game of Thrones.” (He tends not to dwell on “Dr. Pimple Popper,” a reality series about a celebrity dermatologist.) His company, he boasts, is purely focussed on content, not distracted by selling phones or cloud storage or bulk toilet paper. But anyone who runs an enterprise like CNN or HBO knows that the days of easy money from cable fees have ended. CNN made a billion dollars in profit in 2016, and is expecting to make more than eight hundred million dollars this year—a good business, but a shrinking one. The future of entertainment might have been aptly described by Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, in 2016. “When we win a Golden Globe,” he said, “it helps us sell more shoes.”

Someone who has worked with Zaslav for years described his career as a series of cannily seized opportunities. Born in Brooklyn, he spent most of his childhood in suburban Rockland County, where his father was an attorney and his mother taught at a Jewish day school. Zaslav was a talented tennis player; Althea Gibson, the first Black athlete to win a Grand Slam, was his private coach. After graduating from Binghamton University and Boston University School of Law, he went to work for the New York firm of LeBoeuf, Lamb, Leiby & MacRae, where he endeared himself to partners by joining them for matches. “I wasn’t a good lawyer,” he later told Time. “But I was a good tennis player.” (Zaslav declined to speak on the record for this story.)

In 1986, the firm hired Richard Berman, a former general counsel of Warner Cable, who brought along MTV and Discovery as clients. Zaslav was quickly drawn to the work. “It wasn’t the law that I was passionate about,” he later said. “It was the cable business and the idea of building a business.” A few years later, Zaslav recalled in an interview in 2017, he happened upon a story in the trade publication Multichannel News, which said that Bob Wright, the C.E.O. of NBC, wanted to get into cable. Zaslav wrote Wright a letter saying that he wanted to be part of the project. Soon after, he was hired as a junior lawyer for what would become CNBC.

Zaslav has told the story of the letter many times, though recently it got a bit of a punch-up. In the version he delivered in a speech this spring, the article appeared not in Multichannel News but in the Hollywood Reporter, and the letter went not to Wright but to Jack Welch—the C.E.O. of NBC’s parent company and perhaps the greatest corporate celebrity of his time.

When Zaslav started at CNBC, “there were a few layers between him and Jack Welch,” a person who worked there at the time told me. The startup network operated out of Fort Lee, New Jersey, far from NBC’s Art Deco headquarters at 30 Rockefeller Plaza. Eventually, Zaslav began overseeing the negotiations with regional cable companies over how much each would pay to carry CNBC. “David was a transactional guy,” the former NBC co-worker told me. “He went from deal to deal.” But Zaslav was ambitious. His deals often seemed timed to close on the night before a big meeting, and he would show up bedraggled but radiating victory.

“David always attached himself to a higher-up boss,” a colleague from his NBC years told me. A former NBC insider said, “He was very good at managing up. He knows how to get somebody to buy into him.” Many cable-company executives of the era didn’t see themselves as media moguls; they were engineers and scrappy businessmen who had built the infrastructure to bring cable TV into millions of households. Among the most powerful of them was Malone, who ran Tele-Communications Inc., based in Colorado, which at the time was the country’s largest cable company. Malone—a soft-spoken, snowy-haired man with a permanently amused smile—is the controlling shareholder of Formula 1’s parent company and one of the largest private landowners in the United States. “I have earned so much money that money doesn’t interest me,” he told Der Spiegel, in 2001. “Now it is only the love of the game that drives me.”

In a 2017 interview, Zaslav told a story of staying at the office late one night to wait for a call from Malone. When Bob Wright arrived the next morning and found him still there, Zaslav explained why he hadn’t left his post: “You said I should wait for John Malone to call, so I did.” Wright, he said, “got Jack [Welch] on the phone and goes, ‘This guy stayed all night. Can you believe this guy?’ Years later, Bob said to me, ‘That was it. We said, you’re our guy.’ ”

Zaslav considers Welch and Malone his fundamental influences. Welch was known for ferocious cost-cutting and constant attention to the bottom line—which often came with mass layoffs. Malone has a near-fetish for tax avoidance and is a master of strategizing complex transactions. “Jack was analytics and costs and ‘figure out how to manage people out and get the best people in,’ ” Zaslav said on a podcast last year. Malone “is really about long-term strategic thinking and driving toward free cash flow,” he went on. “Somehow, I think the conflation of those two is my brain.”

Welch encouraged a hard-driving corporate culture, which Zaslav strove to embody. Compact and thrumming with energy, Zaslav has a distinct New York accent, and speaks in long narratives that always resolve in a salesman-like pitch. His two primary interests, people who know him well say, are business and his family. Zaslav met his wife, Pam, in high school, and they worked together as lifeguards at a summer camp. They now have three adult children, one of whom is a producer at CNN. Zaslav’s Instagram is filled with pictures of him golfing with his sons and eating at an Italian joint with his mother, who is ninety and lives in New Jersey. “What we love most about David is how he loves his wife Pam and their beautiful family,” Chip and Joanna Gaines, the stars of HGTV’s “Fixer Upper,” wrote not long ago.

Zaslav’s gift for cultivating allies helped him advance, but it also forced him to take sides in a messy corporate conflict. In 1993, Roger Ailes, a Republican political consultant with roots in television production, came to CNBC to help boost ratings. He promoted Zaslav, who was then thirty-three, to head the affiliates division, negotiating deals with various cable companies. But Ailes was in a bitter power struggle with Tom Rogers, the head of the cable division, and he saw Zaslav as loyal to Rogers. According to Gabriel Sherman’s 2014 book, “The Loudest Voice in the Room,” he enlisted comrades to keep an eye on Zaslav and exhorted them, “Let’s kill the S.O.B.” In a meeting, Ailes allegedly called Zaslav “a little fucking Jew prick.”

The conflict took a toll on Zaslav. Sherman writes that an executive saw him “almost visibly shaking in an empty office.” In a memo from the time, Zaslav described a pervasive sense of fear: “I view Ailes as a very, very dangerous man. I take his threats to do physical harm to me very, very seriously. . . . I feel endangered both at work and at home.” Ailes was investigated and ultimately left CNBC, in 1996.

Zaslav and Rogers had outlasted their rival, but the episode had unexpected consequences. Ailes’s separation agreement stipulated that he could not work for such competitors as CNN and Bloomberg, but it said nothing about Rupert Murdoch’s company, News Corporation. Just weeks after leaving CNBC, Ailes held a press conference with Murdoch to announce that he would be the new leader of Fox News.

By 2004, Zaslav was the head of cable distribution and syndication for NBC Universal, a role that was distant from any programming decisions. He had attached himself to yet another boss, an executive named Randy Falco, who ran the business side of the division and was a candidate to take over the company. But Jeff Zucker, the former executive producer of the “Today” show, prevailed, and, according to the former NBC colleague, it was clear to Zaslav that he would never make C.E.O. of NBC. Though he and Zucker maintained a decades-long friendship, people who know them say that it was always tinged with competitive tension. “David kind of always coveted what Jeff was doing,” a person with knowledge of their relationship said. “He became C.E.O. of the company, and he was in charge of all the content and all the movies.”

Zaslav seemed determined to find his way into a similar position. In 2005, he joined the board of the National Cable and Telecommunications Association, whose members included John Hendricks, the founder and chairman of Discovery, and Robert Miron, the chairman and C.E.O. of Advance/Newhouse Communications, which, like Malone, was an owner of Discovery. “Suddenly he got in the room with the guys who built the industry from the ground up,” one person who knew Zaslav at NBC said. “They were long-term thinkers and planners, and serious businesspeople.” Zaslav was eager to develop relationships with them. “He wasn’t particularly strong in terms of assessing and analyzing financial information,” a former cable executive said, of Zaslav. But he was “extremely good at creating bonds with key deal decision-makers.”

One well-informed industry source told me that Malone came to appreciate Zaslav’s energy and skill as an operator—someone who could execute complicated strategies on the ground. The media executive Barry Diller, who has known Malone for decades, told me, “John Malone has had a great facility for finding people that he thought were competent and giving them an enormous opportunity that would not have been available, almost at first blush.” In the summer of 2006, Zaslav began talks to take over Discovery. He was officially installed early the next year, with approval from Hendricks and Malone.

As C.E.O., Zaslav had a difficult remit: take the channel public, shake up its culture, and grow internationally. “At NBC, he was on an easy street with good compensation, not having to work very hard—he could delegate—and, all of a sudden, he had to work his ass off to turn around a group of channels that were underperforming,” the former cable executive said.

Zaslav laid off many of the company’s executives and a quarter of its staff. “There were some real turkey businesses there,” Malone said at the time. “David had to take them out behind the barn and shoot them.” Zaslav needed underlings who would help change the company. “People were coming in at nine, nine-thirty, heading out at six,” he told Time. He wanted those people gone. While some of his top executives are women, Zaslav is “swayed easily by a certain kind of person who talks a certain kind of way, and they all tend to be white men,” one former Discovery employee told me. “Very confident, big swagger. Having a bad reputation can actually be a good thing in his eyes, because it means you’re tough.” Being too nice could earn you a reproach.

Discovery had become known for earnest, carefully made educational and nature programming: Werner Herzog’s “Grizzly Man” documentary, the “Globe Trekker” travel series. Zaslav was more interested in taking advantage of the ongoing boom in reality TV. In 2007, “Jon & Kate Plus 8” premièred on TLC, opening a fruitful niche for Discovery, which then launched “17 Kids and Counting.” Zaslav showed demotic taste, and an instinct for gimmicks and provocations; in 2010, he green-lighted Sarah Palin’s reality show. “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo,” about a child-beauty-pageant contestant from Georgia, was followed by “Wives with Knives,” “Sex Sent Me to the E.R.,” “Naked and Afraid,” and “My Big Fat Fabulous Life.” In what seemed like a bid for more respectable life-style content, Zaslav courted Oprah Winfrey, and together they launched OWN in 2011. Television was then in what became known as its second golden age: “The Sopranos,” “The Wire,” “Mad Men.” Zaslav made a point of not competing in that realm. “It’s like a kids’ soccer game—everyone saw something that worked and started chasing the ball,” he told Time. “It’s way too expensive.” Much of his programming was economical, lucrative, and relatively uncomplicated to produce. “Discovery’s model was completely different than the Hollywood content model,” the former Discovery executive told me. “It was very low-cost content that was made completely on a nonunion basis, owned one hundred per cent by Discovery.”

Malone based Zaslav’s pay mainly on the company’s performance, supplying much of it in the form of equity and stock options that vested over time. Discovery went public in 2008, and S.E.C. filings show that the following year Zaslav’s compensation was $11.7 million. A year later, it had jumped to $42.6 million. In 2014, Zaslav’s pay package was valued at $156.1 million, even as the stock fell by a quarter. “David is clearly a genius,” the former colleague from NBC said. “He’s taken probably about a billion dollars of stockholder money off the table since he started working for Malone personally.” (It’s closer to seven hundred and fifty million dollars. Still, a lot.)

Media-C.E.O. salaries have continued to grow, as the transformation of the industry requires more mergers and acquisitions, and riskier bets on unpredictable markets. But Zaslav was an outlier; even though Discovery’s stock value increased substantially in his time there, he was still the head of a mid-tier media company who in some years made more than Disney’s Bob Iger. In 2022, a firm advising institutional investors recommended that the company’s shareholders decline to reëlect three board members because of their “poor stewardship” around compensation.

For years, Zaslav lived in a tony village in Westchester County. Then, in 2010, he bought Conan O’Brien’s duplex apartment in the Majestic, an Art Deco co-op on Central Park West, for twenty-five million dollars. One person who has known Zaslav for years described the purchase as an act of self-assertion: “There’s a new player in town.” Still, a former Discovery insider who visited the Manhattan apartment said that the décor was almost shockingly modest. There were posters on the walls, and TVs playing programs from Discovery and CNBC—effectively an extension of his office.

Two years later, Zaslav spent another twenty-five million dollars on an oceanfront mansion in East Hampton, where he began hosting a “Shark Week”-themed Labor Day party. His guest lists started to appear on Page Six: Les Moonves, Harvey Weinstein, Donna Karan, Martha Stewart, Jamie Dimon, Ryan Seacrest, Colin Powell. Even Roger Ailes was spotted at a Winter Wonderland party in 2014. These days, Zaslav goes to Taylor Swift shows with Kevin Costner and John McEnroe, and sits courtside at Lakers games with Michael B. Jordan and Bill Maher. Joy Behar, a co-host of “The View,” recently accompanied him to a Bruce Springsteen concert. “He’s very social,” she said. “He’s very alpha—he has a big personality.”

Zaslav enjoys this kind of socializing but sees it as an extension of his work, the media executive Kenneth Lerer, who is a close friend of his, said. Lerer thinks that, without a high-profile job, Zaslav’s natural milieu would be a back-yard barbecue. Zaslav is often seen out in New York—at Barney Greengrass for breakfast, at Le Bilboquet or Porter House for lunch, and at the Polo Bar for drinks. But he tends not to linger. “He would have one course, a glass of wine, no dessert—because, by nine o’clock, David’s out,” the former Discovery insider said.

Zaslav rises at 4:45 A.M. to read the news, and then, when he’s in New York, walks a few miles through the city while making calls. One person sent me a photograph taken of Zaslav hustling up Madison Avenue, in jeans, a sports coat over a zip vest, and dark glasses, talking animatedly on his phone. Zaslav can call underlings as early as 6 A.M., New York time; the conversations often last no more than a minute or two, and sometimes end so abruptly that he doesn’t bother saying goodbye. “Everyone wakes up and they got e-mails from me,” Zaslav once told CNBC. “Part of my job is to push everybody forward.” He can be similarly bluff in meetings. One associate told me that he tends to deliver long monologues and ask questions without seeming intent on hearing the answer. Another associate read the phenomenon differently: “He can be multitasking and you think he’s not paying attention, but he is.”

Some colleagues called Zaslav a short-term thinker, who moves restlessly from idea to idea. His proponents see it differently. “Of all the C.E.O.s I’ve worked with over forty years, he’s probably the most hands-on,” Lerer said. “He gets an idea and he just forces it until there’s a decision.” In that process, others note, he doesn’t always keep his temper in check. “He could be very warm and very nurturing, and then turn on a dime,” the Discovery insider said. “I saw him lash out when people bullshitted, pretending to know what they didn’t know.” An incident in 2008 became a subject of company gossip. When Leonardo DiCaprio, who was an executive producer on a Discovery series, didn’t show up to a première, Zaslav and one of the other producers had what an attendee called a “spirited conversation”—a screaming match. One of Zaslav’s sayings, according to a former employee, was “It’s not show friends. It’s show business.”

During Zaslav’s tenure at Discovery, the industry was undergoing a radical transformation. In 2013, Netflix had launched its first major original streaming series, “House of Cards,” and since then it had poured billions into original movies and TV series. Netflix didn’t much concern itself with profits; its strategy was to dominate the streaming sector first, in the hope that it would eventually generate huge gains. This made some media observers nervous. “One day soon, the finance gods, they’re gonna wake up and say to everybody, ‘Where’s the money?’ ” one former executive told me. Another industry insider said that “an irrational stock market” gave Netflix the incentive to overspend. “And that tipped the scales in the market and caused peak TV and then too much TV,” they said. But Wall Street valued Netflix more as a tech firm than as a media company, and its stock price continued to rise.

Though traditional media companies knew that they needed to adapt for an all-streaming future, their investors weren’t ready to take too many resources away from cable, which was still a reliable, if dwindling, source of cash. “We couldn’t turn ourselves into Netflix because the lion’s share of our network and even studio revenues came from the cable bundle,” the former Time Warner C.E.O. Jeff Bewkes told James Andrew Miller for his 2021 book, “Tinderbox.” Like many others in the industry, John Malone thought that the only way to compete with Netflix was to join forces against it. “You have to aggregate either through coöperation or consolidation,” he said. In 2018, Discovery made its first major effort at that sort of expansion, purchasing Scripps, which owned HGTV, Food Network, and Travel Channel.

A.T. & T. saw the acquisition of Time Warner as a way to expand into a new but complementary field; the idea was that customers could stream A.T. & T.-owned content over A.T. & T. networks on an A.T. & T. platform. That deal is now viewed as a disastrous culture clash, between the Dallas-based telecom giant and the “creatives” who made up the teams at HBO, CNN, and elsewhere. The Times reported that in one early meeting, John Stankey, the C.E.O. of WarnerMedia, outlined for his new executives the protocols for communicating with him: no calls on Saturday, no PowerPoints, and as few meetings as possible. (A spokesperson for A.T. & T. disputed this characterization.)

In February, 2021, as A.T. & T. grappled with the media industry’s rapid changes, Zaslav sent a message to Stankey. “I have an idea,” he wrote, adding a couple of golfer emojis and a smiley face with sunglasses.

The two men talked for a couple of hours, and later met at a Greenwich Village town house to discuss a potential transaction. Finally, they brought in advisers and bankers to settle the details of what Zaslav’s team took to calling Project Home Run. The deal officially closed on April 8, 2022. Two weeks later, in what is now referred to as the Great Netflix Correction, the company reported a drop in subscribers for the first time since 2011; it lost roughly fifty billion dollars in value virtually overnight, and Wall Street abruptly abandoned its enthusiasm for companies that spend huge sums on content. Malone and Zaslav had closed their deal just in time.

As the merger took shape, Zaslav went on a Hollywood listening tour. Bryan Lourd and Ari Emanuel, the co-chair of the talent agency C.A.A. and the C.E.O. of the sports-and-entertainment firm Endeavor, respectively, hosted dinners with writers, actors, and executives. The deep state—the managers and agents who make the industry function—remained relatively receptive to him, hoping that he could undo the damage of A.T. & T.’s ownership. Zaslav was solicitous of the old guard. “We talked a lot about the eighties, nineties, and two-thousands, about how the business started to really change geometrically,” Michael Ovitz, the co-founder of C.A.A., told me. “He wanted a foundation, he wanted roots.” Ovitz offered Zaslav some advice: move to L.A. “When people try to run these creative businesses from the East Coast, it was very difficult to do,” he said. “You don’t get the intrinsic feeling.” Zaslav moved to L.A.

He settled into a new office, in a leafy corner of the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank—a recessed space where he works at Jack Warner’s old desk. A curving conservatory window opens on trees and a manicured garden. By the window is a sitting area where Zaslav receives guests. There, directly behind his chair, is a picture of him with Malone.

In Hollywood, Zaslav quickly adopted local habits. His Woodland house was under renovation, so he took an apartment at the Beverly Hills Hotel and spent a lot of time at its Polo Lounge. But he did not necessarily acquire the “intrinsic feeling” that Ovitz hoped he would. A well-informed source told me that Zaslav’s team fumbled through easy interactions; at one meeting, they asked painfully basic questions about residuals—long-term payments for reruns, DVD sales, and other repeat airings. Before the merger had even closed, Vanity Fair ran a lengthy piece on Zaslav, and Variety declared him “Hollywood’s New Tycoon.” The presumption that an out-of-towner was going to swoop in and fix everything rankled. There were snobbish dissections of his wardrobe and enthusiastic manner—though people were happy to attend parties in his honor and to take his money.

At the time, Jeff Zucker, Zaslav’s former boss at NBC, was running CNN. Zucker was popular with on-air talent, and the network had secured high ratings with aggressive coverage of Donald Trump’s Administration. Much of Hollywood was similarly resistant to his Presidency. But Malone, a libertarian who had contributed two hundred and fifty thousand dollars to Trump’s Inauguration, chafed at CNN’s critical tone. During an interview in November, 2021, Malone said, “I would like to see CNN evolve back to the kind of journalism that it started with, and actually have journalists—which would be unique and refreshing.” Zaslav, too, began to talk about the need for CNN to tack to the center. Two months before the deal was finalized, Zucker was forced to resign, for having an undisclosed relationship with another executive.

Zaslav did not interview any internal candidates for the new C.E.O. Instead, he quickly appointed Chris Licht, a longtime producer who had launched “Morning Joe” on MSNBC and run Stephen Colbert’s late-night show. In June, a long profile in The Atlantic portrayed Licht as a feckless and distant leader, whose ham-fisted decision-making led to such embarrassments as a televised town hall with Trump, in which the host struggled to manage the former President’s ad-hominem attacks as a sympathetic crowd cheered him on. Zaslav was portrayed as an intrusive micromanager, trying to move the network toward an ill-defined political center. According to The Atlantic, CNN employees thought that “Licht was playing for an audience of one. It didn’t matter what they thought, or what other journalists thought, or even what viewers thought. What mattered was what David Zaslav thought.” Zaslav fired Licht days after the article’s publication. He is still searching for a replacement.

A CNN insider described the network’s prospects as the merger went through: the cable business was dying, but CNN had a devoted enough following that, with time and investment, it might be able to reinvent itself. Staffers saw CNN+ as their best hope; even though its programming was somewhat limited, it might help accustom viewers to streaming news from CNN. But Zaslav killed CNN+ after just a month. Now the future of CNN itself is uncertain. Though W.B.D. vehemently denies that it is for sale, many in the newsroom speculate that it would be a prime asset to sell if Zaslav’s debt-payment plan doesn’t go as quickly as Wall Street demands. Guessing at potential CNN buyers has become a media parlor game. Comcast, the corporate parent of NBC News, is seen as a likely potential partner for W.B.D., but CNN might not survive such a deal intact. If W.B.D. and Comcast merged, they might want to offload one of their news networks. “David Zaslav will be remembered as the guy who squandered the opportunity to take the world’s best-known news brand and transition it into a digital future,” the CNN insider said. “Instead, he took the massive yearly profits that CNN has, and used it to pay down debt for this bizarre, complex, convoluted, debt-driven merger.”

But CNN is only a small part of W.B.D.’s business, and of Zaslav’s mandate. “Whenever I talk to David, the first word out of my mouth is, ‘Manage your cash,’ ” Malone said on CNBC last November. Cash generation, he added, “will ultimately be the metric that David’s success or failure will be judged on.” In fact, bonuses for W.B.D.’s top executives this year are officially tied to the company’s cash flow, along with debt reduction. “If you’re an investor, you love David Zaslav,” the former Discovery insider said. “He is a great businessman. If you put a number out, he’s going to make that number.” But, the insider added, “he’s a tractor who will run you down to get to that.”

This spring, Zaslav gave a commencement address at Boston University, where he attended law school. Wearing a red academic robe and sunglasses, he spoke dutifully of the five things he’d learned along the way. “Some people will be looking for a fight,” he warned graduates. “But don’t be the one they find it with.” Outside, the Writers Guild had assembled a picket line. A small plane circled overhead, trailing a banner that read “David Zaslav—Pay Your Writers.”

On Twitter, a writer named Annie Stamell poked at the new C.E.O.: “All we want is 2 Zaslav salaries for 11,500 WGA members, is that really so much to ask?” Two days later, Zaslav and the former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter hosted a party together at the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc, near Cannes, to celebrate a century of Warner films. The two were photographed in near-identical blue button-down shirts and cream-colored jackets, amid bottles of Dom Pérignon. Zaslav told a reporter for New York magazine that the party was for “our best friends, and our real friends, you know, no assholes.”

Zaslav was not alone in failing to project empathy. This July, as executives gathered for the annual media conference in Sun Valley, Idaho, Bob Iger spoke in an interview about Disney’s initiative to control costs by “spending less on what we make, and making less.” This was a terrifying prospect for the creative class, but Iger dismissed the striking writers and actors: “There’s a level of expectation that they have that is just not realistic, and they are adding to a set of challenges that this business is already facing that is quite frankly very disruptive and dangerous.” Disney had recently renewed Iger’s contract through 2026, at a rate of thirty-one million dollars per year. Fran Drescher, the sharp-tongued president of SAG-AFTRA, likened him and his fellow-C.E.O.s to “land barons of a medieval time.”

For writers and actors, streaming has meant a steep drop in residual payments, which once sustained them during career dry spells or made them rich if they created a hit. SAG-AFTRA has said that it wants its members to receive two per cent of the revenue that shows generate from streaming platforms, and wage increases to keep pace with inflation. The studios had put forth a proposal they claimed would offer the union a billion dollars in increased wages and residuals. But, as the Hollywood labor writer Jonathan Handel noted, that works out “to just $30 million per year per company”—roughly a single year’s pay for Iger or Zaslav.

Twenty months after Zaslav was declared “Hollywood’s New Tycoon,” it feels as if the town has turned against him. “He’s feeling the backlash,” as the former media executive put it. He has no choice about servicing his company’s debt. But, the executive went on, “human nature would say the other objective is to prove that you are the mogul. Five years from now, you want to be remembered as someone who helped rebuild the movie business.”

Warner Bros. studios are struggling, despite the billion-dollar success of “Barbie.” Zaslav likes to declare that the company has thirty-five to forty per cent of the world’s most valuable intellectual property—it just needs to take advantage of it. For more than a decade, Marvel’s superhero franchises have dominated the industry, while Warner’s equivalent, DC Studios, has struggled to keep up. Zaslav and his team hope to recruit the director Christopher Nolan, who made a string of successful movies before leaving Warner during A.T. & T.’s ownership. But some in the industry fear that Zaslav’s involvement in the movie business is distracting. Kenneth Lerer conceded that the hands-on instinct he sees as one of Zaslav’s strengths “does have some negatives with the Hollywood establishment, because you go to him, complain to him—he always jumps in. If David would jump in less, I think that’d be helpful to him.” A recent Variety feature on Warner Bros.’s new co-chairs, Michael De Luca and Pamela Abdy, noted that Zaslav showed up at the interview and snapped a “photo of his film chiefs being interviewed, like a doting dad at an amusement park.”

The studio and the strikes are only one problem Zaslav and other executives must solve. Media C.E.O.s know that the loss of cable earnings can’t be replaced by the streaming model that Netflix and Amazon helped establish. Seventy per cent of W.B.D.’s revenue is tied up in its cable channels, while its television and movie studios account for roughly thirty per cent. Even as Zaslav works to establish himself in Hollywood, the vast majority of his cable assets are based in New York and Atlanta. He needs to squeeze them for cash while managing their demise. (A spokesperson for W.B.D. said that Zaslav wanted to devote time to his Hollywood businesses during the first year but now lives between New York and L.A.)

One of his biggest looming deals has to do with renewing TNT’s right to carry N.B.A. games. Live sports are a primary reason that consumers keep their expensive cable subscriptions, and so networks risk losing customers if they lose the contract. “It’s like heroin,” Malone once said. “You’ve gotta keep buying and buying it.” Disney and W.B.D. currently own the N.B.A. rights, but it’s likely that a streamer that wants in on the sports market will join the bidding, driving up the price. “David’s not going to want to say he lost the N.B.A.,” one close observer of the deal said. “He’s paying $1.2 billion per year right now. He will pay more than $1.2 billion to keep the N.B.A., with possibly fewer games.”

Zaslav and his team have blamed some of their difficulties on the condition of WarnerMedia. At an investor conference, Zaslav complained that some of the company’s assets had turned out to be “unexpectedly worse than we thought” before the deal closed. The former Discovery employee told me, “We knew the debt would be bad. When the number came out, we were stunned and scared.” W.B.D. went so far as to investigate whether A.T. & T. inflated the projections that underpinned WarnerMedia's value. Last summer, A.T. & T. paid W.B.D. $1.2 billion. (The spokesperson for the company said that this payment reflects a standard post-close adjustment.)

Whatever the cause, W.B.D.’s first year was rocky. Zaslav’s plan to cut costs began almost immediately and brought a stream of bitter reactions. Among other things, the company started removing little-watched shows from HBO Max, including the cult hit “Westworld.” “We don’t think anybody is subscribing because of this,” Zaslav said, of the removed programming, in November, 2022. “We can sell it nonexclusively to somebody else.” Writers, showrunners, and actors complained of a disorganized process of informing them about the future of their shows. “People who you would normally talk to have been fired, moved, or quit, so no one has any idea how to get the information they need right now,” the showrunner and animator Owen Dennis wrote on Substack. “Never cheer for a corporate merger, they help about 100 people and hurt thousands.”

Though jobs were slashed across the company, one of the biggest controversies came from Zaslav’s decision to cut the budget at Turner Classic Movies, laying off several senior executives in the process. According to the Hollywood Reporter, Bryan Lourd and Steven Spielberg warned ahead of time that the cuts would attract outrage; the film industry cherishes its own history, and particularly the history of its greatest hits. Zaslav apparently complained that outsiders were telling him how to run his business.

After the cuts were announced, Spielberg, Martin Scorsese, and Paul Thomas Anderson joined a Zoom meeting with Zaslav to plead the network’s case. Zaslav offered a concession, moving the oversight of TCM from the cable division to Warner Bros., run by the Hollywood veterans De Luca and Abdy. One TCM executive got his job back, too. The directors, seemingly pacified, released a statement: “We have each spent time talking to David, separately and together, and it’s clear that TCM and classic cinema are very important to him.”

Some saw the incident as a demonstration of Zaslav’s impetuous decision-making. Others argued that, even though Zaslav craved acceptance in Hollywood, he knew that his mandate was to save money. On the ledger, W.B.D. seems to be making progress. This year, it launched a new streaming service, Max, which mixes premium HBO content with some of Discovery’s more down-market shows. Max allows subscribers to pay less in exchange for agreeing to view ads—a model that Netflix adopted last year—and increased streaming ad revenue by a quarter in its first few months, even as subscribership dipped. W.B.D.’s latest quarterly report says that it lost three million dollars on streaming, compared with a loss of five hundred and fifty-eight million dollars in the same period last year. Though Hollywood is in crisis, W.B.D. has found a benefit to the strikes: you spend less money when you aren’t making anything. Gunnar Wiedenfels, the C.F.O., announced in August, “Should the strikes run through the end of the year, I would expect several hundred million dollars of upside to our free cash flow.” Since W.B.D. was formed, Zaslav has paid down nearly nine billion dollars in debt. Some $47.8 billion remains.

Those sympathetic to Zaslav’s project of “rationalizing” the economics of streaming think that the anger at him is unfair. “We are all little boats navigating uncharted waters,” Alan Horn, the former Warner Bros. C.O.O., said. “The issues we’re having right now in the middle of a strike are exacerbated by the fact that no one quite knows exactly how to get to a ‘new normal.’ ” By this argument, Zaslav is being blamed for an agonizing but inevitable period of adjustment. “He said, ‘Look, this company needs restructuring so that it may be as healthy as possible in the long term. That requires some short-term actions that are painful,’ ” Horn said.

Barry Diller, who spent “a great deal of the nineteen-seventies and nineteen-eighties” at Robert Evans’s Woodland estate as the C.E.O. of Paramount Pictures, has known Zaslav since his NBC years. He’s optimistic about Zaslav’s project, if not entirely clear on what the future holds. “W.B.D. will make it through. I do believe that,” Diller said. “What comes out on the other end is, frankly, up to the gods.”

The actors and writers on the picket line are less sanguine. Even as they protest, they need Zaslav and his peers to help Hollywood make sense again: to calibrate a streaming system so they can make both art and money, if in a more modest way than they used to. But Zaslav has enough to do solving the problems of his own company.

Collage illustration of David Zaslav

Illustration by Nicholas Konrad / The New Yorker; Source photograph by Steve Mack / Everett / Alamy

#twd#david zaslav#warner bros#hollywood#corporate media#global corporate monoculture#reality television ruins everything#pay your writers#studio

1 note

·

View note

Note

But even on their own scripts they work with others like Jim Jarmusch or Lars von Trier who btw also go back working with the same women on different projects in different departments like art direction, casting, set design, etc. Just because he sees himself as an auteur doesn't mean he has to do everything himself. // many directors write their scripts alone. And I think he sees himself as a 70 auteur 😂 anyone interested in film history would know that historically, back in Old Hollywood and even silent era women had better positions as both stars and behind the scenes creatives. After the collapse of the studio system in 60s, the “New Hollywood” directors came in the 70s and if you look at the movies of that era it was mostly men. Not just the crew but also movies about women for women weren’t being made like back in 1930s anymore, when women were the majority of filmgoers and actresses ruled the box office. 70s was all about men in movies, most famously The Godfather. Sorry for the filmbro rant lol. Again Alex and his boys being in love with the 70s rather than another decade shows how much they love the patriarchy

Oh, I'm sorry I didn't know I had to only reference the 70s. I'm living more in the present which affects me more so I named more recent directors. My bad.

And people wonder why I dislike the 70s so much.

0 notes

Text

Un jour, une chanson : Faites de la musique ! James Brown " The Godfather of Soul "- Sex machine !

James Brown est un chanteur, auteur-compositeur, producteur et acteur américain né le 3 mai 1933 en Caroline du Sud et décédé le 25 décembre 2006 en Géorgie. Il est considéré comme l’un des précurseurs de la musique soul, du funk et du rap. Sa carrière musicale a commencé dans les années 1950 avec le groupe de gospel les Famous Flames. Il a ensuite poursuivi une carrière solo et a publié de…

youtube

View On WordPress

#Un jour - une chanson : Faites de la musique ! James Brown " The Godfather of Soul "- Sex machine !#Youtube

0 notes

Photo

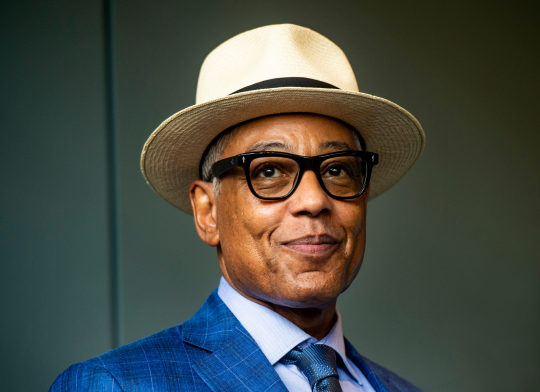

Giancarlo Esposito is teaming up with legendary director Francis Ford Coppola

Francis Ford Coppola is such an interesting director to be a fan of. In the 70s, fresh off the success of the Godfather, Godfather 2, and Apocalypse Now, Coppola was one of the greatest auteurs of his era. — Read the rest

https://boingboing.net/2023/01/28/giancarlo-esposito-is-teaming-up-with-legendary-director-francis-ford-coppola.html

0 notes

Text

David Cronenberg: Blame ‘Political Correctness’ for the Lack of Movie Sex

David Cronenberg: Blame ‘Political Correctness’ for the Lack of Movie Sex

Nicolas Guerin/Getty

David Cronenberg is the godfather of body horror, a subgenre he pioneered in the ‘70s with such boundary-pushing indies as Shivers, Rabid and The Brood, and then introduced to the mainstream in the ‘80s and ‘90s with the likes of Scanners, The Fly, Dead Ringers and the Cannes Film Festival-hailed Crash. In those and other works, the 79-year-old Canadian auteur explored the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Rassilon's Visionary, Last Mapper of Gallifrey?

I wonder if The Visionary from The End of Time was a Mapper, or some Pythian/Karn equivalent. Obviously the Sisterhood of Karn is already far more mystical than orthodox Gallifreyan society and her alias isn't reeeaaallly a timekeeping pun like we are told most Mappers went with, but there are still some things which make me ponder it.

Most obviously there's the fact that she spends 90% of her time scribbling and scrawling prophecies in Circular Gallifreyan that are treated with the utmost seriousness by Rassilon & his cronies, which naturally reminds me of the most famous Mapper in the wider Whoniverse, Auteur (if we believe his story, of course)

And while that is mostly an Auteur "thing" specifically it's perfectly possible other Mappers would keep a penchant for using their language of temporal cartography quite...obsessively, as the Visionary does.

The Visionary also seems to be a few silly collars short of a High Council; we are told that when all the Mappers were plugged into the ancient Gallifreyan Matrix to download their memories and "map" out the new chronology of the Anchored universe, they were first haphazardly drugged with hallucinogens from across the universe in what can only be described as the Time Lord equivalent of MKUltra. It is said explicitly that this process broke the minds of every Mapper to undergo it (aka every Mapper)

The Visionary also has very interesting tattoos, which one could read as similar to the tattooed star chart that adorned the mad Time Lord and (retroactively implied) Mapper Astrolabus, who was eventually skinned for having done so and, well we're not quite sure what happened to him...

A minor point of note is also that the Visionary was specifically welcomed onto Rassilon's Council; something interesting if we assume her to be a Mapper, a member of the Sisterhood of Karn or even both, due to the history Rassilon has with...well basically everything in Gallifreyan history to be frank with you.

But regardless, Mappers were one of the first generations of loomed Time Lords after the Anchoring of the Thread, created on Rassilon's orders to observe and "map" the new spacetime continuum of the rational universe. If anyone would know that a Mapper, maddened or not, would be useful to him on his council during the Last Great Time War, it's Rassilon.

(As an aside, the depiction of the Anchoring of the Thread in Doctor Who: Flux and its additions does make me ponder if Mappers were in fact a Division project specifically, but that's a theory for another day)

Heh...

Heh...

Heh...

#faction paradox#fan theory#doctor who#headcanon#eighth doctor adventures#nuwho#rassilon#Sisterhood of Karn#Mapper#Godfather Auteur#Auteur

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"The other is a disheveled wraith, frumpled violet robes, and tattered remnants of House regalia. His mask is his own skull, the shadow that serves as his skin peeled back just enough to show the red-stained bone. His eyes, wide and shrivelled, look like golf balls."

A small personal project I worked on in my spare time (And to bolster my design portfolio). Godfather Auteur, who features in A Bloody and Public Domain (Book of the Enemy) & Going Once, Going Twice (Book of the Peace), both by @rassilon-imprimatur . My two biggest influences for the design came from the Skeksis (Mostly the Chamberlain) and a rather abstract self portrait by Paul McCartney (Hence his lopsided jaw).

Also the Circular writing on his collar is meant to read "Astrolabus, One of the First to Map History, and the Pyhagoran writing on his sleeves translates to "Godfather Auteur, Author of the Spiral Politic".

[VISUAL DESCRIPTION: A character sheet featuring a skeletal hunched-over figure clad in ragged dull robes. Dark shadow spills out the eye sockets and nose hole to form lips set in a wide smug grin. In his hand is a small feathered quill. Alongside the figure are two sketches showing the figure, one with a irritable frown and another with a raised brow in thoughtfulness.]

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1: Godfather Auteur

Written as part of the October Art prompt thingy @liria10 put together. Set post-Family Matters.

In her dreams, she sees him. Though, perhaps those dreams would be better classified as nightmares. He’s a horrible sight to behold - no skin, only bone, muscle, and hair. She tries to focus on just the bones, and not the muscles, hair, and organs, held together by veins tied in knots. The bones are the least horrifying part.

In her dreams nightmares, he doesn’t do anything. He just sits there, fading in and out of her mind, like fog that comes and goes. She knows nothing of him, nor does he permit her to know anything about him. She often awakes with a start in a cold sweat and can’t get back to sleep.

She wishes she knew who he was, and why he’s in her dreams.

He doesn’t appear every night, but enough nights for exhaustion to seep into her bones. Tonight is one of those nights.

As usual, Verity awakes in a cold sweat, groans softly to herself, runs her hands over her face and gets up, knowing there’ll be no going back to sleep tonight. She runs herself a hot shower to wash the sweat off, and then wanders out of her room towards the kitchen, figuring that, if she can’t sleep, she may as well have breakfast.

She knows the Doctor doesn’t sleep as often as the rest of them - something about her alien biology or whatever - but she had been under the impression that the Doctor would be napping at this hour. Or, at the very least, doing a calming, relaxing activity. Granted, cooking can be considered relaxing by some, but what Verity walks in on is...not relaxing.

There are bowls and open containers everywhere, a mess of ingredients on the counter, plates of failed attempts and the persistent beep! beep! beep! of a fire alarm that no one has bothered to turn off. And, in the middle of this mess, is the Doctor, tongue stuck out in concentration as she measures what looks like sherry - though Verity can’t be sure at this point - into a bowl.

“I, uh, er, Doctor?” Verity asks. The Doctor looks up and beams.

“Verity! Come to help, have you?” She suddenly frowns, looking around for a clock, which appears most conveniently on the wall in a sort of fond exasperation. “Wait. It’s 3am. I thought humans were supposed to be asleep at 3am.”

“They...are,” Verity says hesitantly, before quickly changing the subject. “What are you making?”

The Doctor sighs. “I’m attempting to make fried bread, but it’s not working very well. I think I may have jumbled my recipes.” Verity frowns at the blackened lumps. They don’t look like any bread she’s seen. “What about you, what are you doing up?”

It’s Verity’s turn to sigh. “Couldn’t sleep.”

“Is it the fire alarm?” the Doctor asks, concerned. “I thought the old girl would have kept the noise in here.”

Verity shakes her head. “No, it’s not the alarm.” She hesitates. “It was just a bad dream, that’s all.”

The Doctor puts down her spoon and pulls out two chairs for the both of them to sit on and face each other. “I’m not the best at the whole emotions thing, but I can listen well. Well, decently. Okay, a little bit. Well, I at least try to listen.” Verity giggles a little. “Especially when it’s something important.”

“It’s not,” Verity sighs, touched by the Doctor’s offer. “It’s just a bad dream. Happens to all of us.”

“But not as often as it’s happening to you.”

Verity startles, looking at the Doctor where she had previously avoided doing so. How had she known? Did the TARDIS monitor their dreams? She hoped not, that would be an invasion of privacy, and she doesn’t think the Doctor is one to do something like that. She’s proven herself trustworthy thus far.

She considers denying it, insisting that this is a one-time occurrence, but looking at the Doctor’s earnest and patient face reminds her of just how tired she is. Her shoulders sag and she hangs her head.

“No,” she agrees. “Not as often.”

“What’s up?” the Doctor coaxes. “What’s bothering you?”

Verity sighs again and explains the contents of her nightmares to the Doctor, including describing the man she sees. The Doctor sits silently and listens, nodding slowly, her expression darkening when Verity describes the man.

“Ah,” the Doctor says when Verity’s finished talking.

“‘Ah’?”

“Ah,” the Doctor repeats. “I think I may know who’s showing up in your dreams.”

“Who?”

“His name was Auteur. Godfather Auteur if we’re going to use titles, which he always insisted on. Skinless Gallifreyan, member of the Faction Paradox. Had this weird thing for being the author of fate or something - my memory’s a little fuzzy on the details. But, long story short, even the Faction didn’t want him and so they imprisoned him.”

“The Faction? Wasn’t that the thing...well, you know, was a part of?”

It’s been several weeks, but she still can’t bring herself to say his name. The Doctor nods.

“The same. I reckon that’s why Auteur has been showing up in your dreams. Some wibbly wobbly Faction-y Waction-y thingamajig that’s going on in your head as sort of an aftereffect from injecting yourself with a bit of Faction blood.”

“‘Faction-y Waction-y’?” Verity repeats, amused. The Doctor nods seriously, though there’s a slight twinkle in her eye.