#freyja alf

Text

exagarrated tav expressions (shes like laois from dunmesh, but not expressive)

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to worship Freyr

(Introduction & symbols included!)

A bit of history: who is Freyr?

Yngvi-Freyr, son of Njördr, brother of Freyja, is one of the very few Vanir Gods mentioned in the eddas. The Vanir, as some of you may already know, are benevolent Gods associated with natural phenomena. Freyr lives in Álfheim, world of the elves, where it is speculated he occupies a place of great importance (like king or some kind of leader). This comes from the fact that old Scandinavian peoples considered him protector of all leaders. He was often called “king of kings”. In fact, the name “Freyr” quite literally means “Lord”. One of his most popular stories involves his wife-to-be Gerð, whom he was set on seducing. The giantess accepted to grant him her hand, should he give up his most treasured possession: his sword. Freyr thus discarded the weapon for good and could marry the woman he yearned for, though he would die in Ragnarök due to his lack of a sword.

He is primarily a god of fertility, his statue believed to bring prosperity to whoever venerates it. He was often called upon to make the land fertile and the crops plentiful. By extension, he is widely associated with harvests and rains, as well as wealth, prosperity and success. He is also a symbol of peace and is very often compared to sunlight, as he is described as having a very warm and kind personality. He is said to be friendly and peaceful in temperament, very comforting to his devotees. His mercy and kindness are, according to most, unconditional. Though I’m diving into UPG’s and I’ll leave that part up to you guys.

Cool fun fact: in ancient norse culture, weapons were strictly forbidden inside Freyr’s temples and on his sacred grounds. In fact, shedding blood in his presence was considered disrespectful and caused him great displeasure.

Symbols

The boar, a gift he’d earned thanks to Lopt and a bunch dwarves who crafted this uncommon steed.

Crops and agriculture.

Boats! His own is called Skíðblaðnir and is the mightiest of the Gods’ ships, for it was said to sail without winds and could be folded up to fit in Freyr’s pocket.

Antlers/horns, due to various similarities with the celtic God Cernunnos. He is also said to utilize an elk’s horn as a weapon instead of his own sword during Ragnarök.

Sunrises, daybreak and welcome rains (according to Snorri).

The color gold, for his ship and boar are said to bear it.

Gender non-conformity! And I’m very serious with that one: according to historical accounts, more “effeminate” men, Morris dancers, would apparently hold devotional dances for him, decorated with bells and bearing phallic staves in hopes of waking the earth up during spring.

Phallic symbols! Yup, you all knew that one was coming. This representation of fertility is indeed as old as times.

Kennings: God of the World, Alf King, Boar King, King of Kings, Giver of Riches, Gentle Lord of Mirth, Lord of Plenty, Bold Rider and Liberator. The last two are references to one of Týr’s lines in the Lokasenna (stanza 37), in which he describes Freyr as “the best of all the bold riders in the courts of the Æsir [who] makes no girl cry nor any man’s wife and loses each man from captivity.”

How to worship him?

• Devotional dances (obviously). Really any type of dance which you want to dedicate to him. Songs work very well too!

• Cooking or baking, to make use of the many gifts of harvest.

• Venerating him during solstices and equinoxes, since he’s a prominent symbol of the turning seasons.

• Making art of him: pre-christian Scandinavia was very keen on keeping statues/representations of him in the home to ensure its prosperity.

• Shop locally! Encourage farms and businesses in your area.

• Common offerings: bread, flowers, food in general, coins, beer, phallic symbols, art of him, the rune ingwaz (maybe carved on wood or drawn), depictions of boars/horses/stags, candles to represent sunlight, anything golden, poems, etc… His devotees like to offer these at dawn, a lot of the time.

Art by Donn P. Crane, Richard Pace, and Emil Doepler

#i always dive too deep in the history part dont i#freyr#norse gods#norse polytheism#worship#deities#deity work#mythology#norse paganism#paganism#polytheism

277 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Do you have any gender neutral names inspired by Norse mythology or that sounds Norse?

Alf

Meaning: elf

Origin: Old Norse

Related names: Alfr

Alvis

Meaning: all wise

Origin: Old Norse

Ask

Meaning: ash tree

Origin: Old Norse

Atli

Meaning: little father

Origin: Gothic

Baldr

Meaning: hero, lord, prince

Origin: Old Norse

Alternate spelling: Balder

Bragi

Meaning: poetry

Origin: Old Norse

Brokkr

Meaning: badger

Origin: Old Norse

Eir

Meaning: mercy

Origin: Old Norse

Elli

Meaning: old age

Origin: Old Norse

Embla

Meaning: elm

Origin: Old Norse

Erna

Meaning: brisk, vigorous, hale

Origin: Old Norse

Fenrir

Meaning: marsh, fen

Origin: Old Norse

Freya

Meaning: lady

Origin: Old Norse

Alternate spelling: Frea, Freyja

Freyr

Meaning: lord

Origin: Old Norse

Frigg

Meaning: beloved

Origin: Old Norse

Gandalf

Meaning: wand elf

Origin: Old Norse

Gerd

Meaning: enclosure

Origin: Old Norse

Gróa

Meaning: to grow

Origin: Old Norse

Gudrun

Meaning: god's secret lore

Origin: Old Norse

Gunner

Meaning: war + warrior

Origin: Old Norse

Heidrun

Meaning: bright secret

Origin: Old Norse

Heimdall

Meaning: home, house + glowing, shining

Origin: Old Norse

Hel

Meaning: to conceal, to cover

Origin: Old Norse

Hildingr

Meaning: chief, warrior

Origin: Old Norse

Hoder

Meaning: battle

Origin: Old Norse

Hulda

Meaning: hiding, secrecy

Origin: Old Norse

Idun

Meaning: to love again

Origin: Old Norse

Alternate speling: Idunn

Jörmungandr

Meaning: large monster

Origin: Old Norse

Kára

Meaning: curly, curved

Origin: Old Norse

Loki

Meaning: knot, lock

Origin: Germanic

Related names: Loke

Magni

Meaning: mighty, strong

Origin: Old Norse

Nanna

Meaning: daring, brave

Origin: Old Norse

Njord

Meaning: strong, vigorous

Origin: Indo-European

Odin

Meaning: inspiration, rage, frenzy

Origin: Germanic

Related names: Wodan, Wotan, Wuotan

Orvar

Meaning: arrow

Origin: Old Norse

Sif

Meaning: bride, kinswoman

Origin: Old Norse

Alternate spelling: Siv

Saga

Meaning: seeing one

Origin: Old Norse

Sindri

Meaning: sparkle

Origin: Old Norse

Skadi

Meaning: damage, harm

Origin: Old Norse

Thor

Meaning: thunder

Origin: Old Norse

Trym

Meaning: noise, uproar

Origin: Old Norse

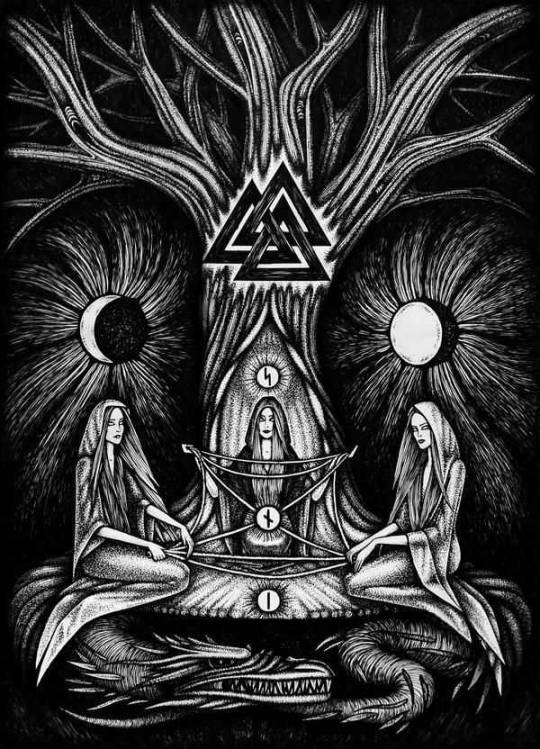

Urd

Meaning: fate

Origin: Old Norse

Vanadís

Meaning: goddess of the Vanir

Origin: Old Norse

Verdandi

Meaning: becoming, happening

Origin: Old Norse

Vidar

Meaning: wide warrior

Origin: Old Norse

#writeblr#names#character names#oc names#oc ideas#name ideas#name suggestions#writers on tumblr#mystery guest#norse mythology

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guide to Norse Gods and Goddesses

Aesir

The collective name for the principal race of Norse gods; they who lived in Asgard, and with the All-Father Odin, ruled the lives of mortal men, the other was the Vanir.

The Aesir gods under the leadership of Odin, included:

Balder (god of beauty)

Bragi (god of eloquence)

Forseti (god of mediation)

Freyr (god of fertility, who originally was from the Vanir)

Heimdall (guardian of the bridge)

Hod (the blind god)

Loki (the trickster of the gods)

Njord (the sea god, and another ex-Vanir)

Thor (god of thunder)

Tyr (god of war)

Vili (brother to Odin)

Ve (brother to Odin)

Vidar (Odin’s son)

The goddesses included:

Freya (the fertility goddess)

Frigga (Odin’s wife)

Sif (Thor’s wife)

Idun (keeper of the apples of youth)

Vanir

In Norse mythology, the Vanir are originally a group of wild nature and fertility gods and goddesses, the sworn enemies of the warrior gods of the Aesir. They were the bringers of health, youth, fertility, luck and wealth, and masters of magic. The Vanir live in Vanaheim. The Aesir and the Vanir had been at war for a long time when they decided to make peace. To ensure this peace they traded hostages: the Vanir sent their most renowned gods, the wealthy Njord and his children Freya and Freyr. In exchange the Aesir sent Honir, a big, handsome man who they claimed was suited to rule. He was accompanied by Mimir, the wisest man of the Aesir and in return the Vanir sent their wisest man Kvasir. Honir however, was not as smart as the Aesir claimed he was and it Mimir who gave him advice. The Vanir grew suspicious of the answers Honir gave when Mimir was not around. Eventually they figured out that they had been cheated and they cut Mimir’s head off and sent it back to the Aesir. Fortunately, this betrayal did not lead to another war and all the gods of the Vanir were subsequently integrated with the Aesir. There is not much known about the Vanir of the time before the assimilation.

Valkyries

Valkyries, in Scandinavian mythology, are the warrior maidens who attended Odin, ruler of the gods. The Valkyries rode through the air in brilliant armor, directed battles, distributed death lots among the warriors, and conducted the souls of slain heroes to Valhalla, the great hall of Odin. Their leader was Brunhilde.

Brunhilde

Brunhilde (Brynhildr, Brunhilda, Brunhilde, Brünhild) was a female warrior, one of the Valkyries, and in some versions the daughter of the principal god Odin. She defies Odin and is punished by imprisonment within a ring of fire until a brave hero falls in love and rescues her. Siegfied (Sigurðr, Sigurd) breaks the spell, falls in love with her and gives her the ring, Andvarinaut. Siegfied is tricked and accused of infidelity. Eventually Brunhilde kills herself when she learns that Sigurd had betrayed her with another woman (Gudrun), not knowing he had been bewitched into doing so by Grimhild.

Gullveig

Gullveig (“gold branch”) is the sorceress and seer who had a great love and lust for gold. She talked of nothing else when she visited the Aesir. They listened with loathing and eventually thought the world would be better off without her so they hurled her into the fire. She was burned to death but stepped from the flames unscathed. Three times she was burned, and three times she was reborn. When the Vanir learned about how the Aesir had treated Gullveig they became incensed with anger. They swore vengeance and began to prepare for war. The Aesir heard about this and moved against the Vanir. This was the first war in the world. For a long time, the battle raged to and fro, with neither side gaining much ground. Eventually the gods became weary of war and began to talk of peace. Both sides swore to live side by side in peace. Gullveig is also known under the name of Heid (“gleaming one”). She is probably the goddess Freya, who also has a great love of gold in the various myths.

The Norse Gods & Goddesses

Aegir

Aegir is the god of the sea in Norse mythology. He was both worshipped and feared by sailors, for they believed that Aegir would occasionally appear on the surface to take ships, men and cargo alike, with him to his hall at the bottom of the ocean. Sacrifices were made to appease him, particularly prisoners before setting sail. His wife is the sea goddess Ran with whom he has nine daughters (the billow maidens), who wore white robes and veils. His two faithful servants are Eldir and Fimafeng. The latter was killed by the treacherous god Loki during a banquet the gods held at Aegir’s undersea hall near the island of Hler (or Hlesey). Aegir was known for the lavish entertainment he gave to the other gods.

Baldr

Balder, son of Odin and Frigga, the god of Love and Light, is sacrificed at Midsummer by the dart of the mistletoe and is reborn at Jul (Yule). Supposedly his return will not occur until after the onslaught of the Ragnarok, which I see as a cleansing and enlightenment more than wanton, purposeless destruction. Balder’s blind brother Hodur was his slayer, whose hand was guided by the crafty Loki. He is married to the goddess of Joy, Nanna. Balder’s dreams are the beginning of the end. He dreams of his own death and shows Loki the truly evil god that he is which shows the ultimate limitations and mortality of the gods. The gods capture and punish Loki, but they cannot rescue Balder from Hel and the beautiful, passive god who embodies the qualities of mercy and love is lost to them. This is the beginning of the end, the first step towards Ragnarok begins.

There is nothing but good to be told of him. He is the best of them, and everyone sings his praises. He is so fair of face and bright that a splendor radiates from him, and there is a flower so white that it is likened to Balder’s brow; it is the whitest of all flowers. From that you can tell how beautiful his body is, and how bright his hair. He is the wisest of gods, and the sweetest-spoken, and the most merciful, but it is a characteristic of his that once he has pronounced a judgement it can never be altered. – Snorri Sturluson

Bragi

The god of eloquence and poetry, and the patron of skalds (poets) in Norse mythology. He is regarded as a son of Odin and Frigga. Runes were carved on his tongue and he inspired poetry in humans by letting them drink from the mead of poetry. Bragi is married to Idun, the goddess of eternal youth. Oaths were sworn over the Bragarfull (“Cup of Bragi”), and drinks were taken from it in honor of a dead king. Before a king ascended the throne, he drank from such a cup.

Note: Originally, Bragi did not belong the pantheon of gods. He was a poet from the 9th century, Bragi Boddason. Poets from later centuries made him a god.

Forseti

Forseti in Norse mythology, Forseti is the god of justice. He is the son of the god Balder and his mother is Nanna. He rules in the beautiful palace Glitnir with its pillars of red gold and its roof with inlaid silver, which serves as a court of justice and where all legal disputes are settled. See Myth 12 The Lay of Grimnir. Although Forseti is one of the twelve leading gods, he is not featured significantly in any of the surviving myths. He can be compared with the Teutonic god Forseti, who was worshipped on Helgoland a small Island in the North Sea.

Freya

Freya was one of the most sensual and passionate goddesses in Norse mythology. She was associated with much of the same qualities as Frigg: love, fertility and beauty. She was the sister of Freyr. Freyja (modern forms of the name include Freya, Freja, Freyia, Frøya, and Freia) is the goddess of Love and Beauty but is also a warrior goddess and one of great wisdom and magick. She and her twin brother Freyr are of a different “race” of gods known as the Vanir. Many of the tribes venerated her higher than the Aesir, calling her “the Frowe” or “The Lady.” She is known as Queen of the Valkyries, choosers of those slain in battle to bear them to Valhalla (the Norse heaven). She, therefore, is a psychopomp like Odhinn and it is said that she gets the “first pick” of the battle slain. She wears the sacred necklace Brisingamen, which she paid for by spending the night with the dwarves who wrought it from the bowels of the earth. The cat is her sacred symbol. There seems to be some confusion between herself and Frigga, Odin’s wife, as they share similar functions; but Frigga seems to be strictly of the Aesir, while Freyja is of the Vanir race. The day Friday (Frejyasdaeg) was named for her (some claim it was for Frigga).

Freyr

Freyr was the god of fertility and one of the most respected gods for the Vanir clan. Freyr was a symbol of prosperity and pleasant weather conditions. He was frequently portrayed with a large phallus. Freyr is Freyja’s twin brother. He is the horned God of fertility and has some similarities to the Celtic Cernunnos or Herne, although he is NOT the same being. He is known as King of the Alfs (elves). Both the Swedish and the English are said to be descendants of his. The Boar is his sacred symbol, which is both associated with war and with fertility. His golden boar, “Gullenbursti”, is supposed to represent the daybreak. He is also considered to be the God of Success, and is wedded to Gerda, the Jotun, for whom he had to yield up his mighty sword. At Ragnarok, he is said to fight with the horn of an elk (much more suited to his nature rather than a sword.)

Frigg

Odin’s wife, Frigg, was a paragon of beauty, love, fertility and fate. She was the mighty queen of Asgard, a venerable Norse goddess, who was gifted with the power of divination, and yet, was surrounded by an air of secrecy. She was the only goddess allowed to sit next to her husband. Frigg was a very protective mother, so she took an oath from the elements, beasts, weapons and poisons, that they would not injure her brilliant and loving son, Baldr. Her trust was betrayed by Loki, a most deceitful god. She spins the sacred Distaff of life, and is said to know the future, although she will not speak of it. Some believe that Friday was named for her instead of Freya, and there is considerable confusion as to “who does what” among the two. The Norns (Urd, Verdande, and Skuld), are the Norse equivalent of the Greek Fates. It is they who determine the oorlogs (destinies) of the Gods and of Man, and who maintain the World Tree, Yggdrasil.

Gefion

Gefion (“giver”) is an old-Scandinavian vegetation and fertility goddess, especially connected with the plough. She was considered the patron of virgins and the bringer of good luck and prosperity. Every girl who dies a virgin will become Her servant. She is married to King Skjold or Scyld a son of Odin, and lived in Leire, Denmark, where she had a sanctuary. The Swedish kings are supposed to be her descendants. It is traditionally claimed that Gefion created the island of Zealand (“Sjaelland” in Danish) by ploughing the soil out of the central Swedish region with the help of her sons (four Swedish oxen), creating the great Swedish lakes in the process. In Copenhagen, Denmark, there is a large fountain showing Her in the process of ploughing. Gefion could be another form of Frigga who is also known under that name.

Heimdall

Heimdall, known as the ‘shiniest’ of all gods due to him having the ‘whitest skin’, was a son of Odin who sat atop the Bifrost (the rainbow bridge that connects Asgard, the world of the Æsir tribe of gods, with Midgard, the world of humanity) and remained forever on alert; guarding Asgard against attack.

In the Lay of Thrym, it is Heimdall’s idea to Dress up Thor as a woman, in order to trick Thrym, the king of the frost giants, into thinking it was Freyja. The ploy works and Thor recovers his stolen hammer Mjollnir. Heimdall was associated with the sea and was the son of nine maidens (9 waves??). In Myth 5 – The Song of Rig he calls himself Rig and travels across the land visiting several households, speaking honeyed words, winning over the woman of the household and creating the three races of men. His acute senses make him an ideal watchman for the gods. His hall is Himinbjorg (Cliffs of Heaven) which stands near the rainbow Bifrost. He owns the horn Gjall which can be heard throughout the nine worlds.

He needs less sleep than a bird and can see a hundred leagues in front of him as well by night as by day. He can hear the grass growing on the earth and the wool on sheep, and everything that makes more noise – Snorri Sturluson

Hel

Hel was the goddess of the dead and the afterlife was Hel (Holle, Hulda), and was portrayed by the Vikings as being half-dead, half alive herself. The Vikings viewed her with considerable trepidation. The Dutch, Gallic, and German barbarians viewed her with some beneficence, more of a gentler form of death and transformation. She is seen by them as Mother Holle; a being of pure Nature, being helpful in times of need, but vengeful upon those who cross her or transgress natural law.

Höðr

(Old Norse: Hǫðr [ˈhɔðr] (listen); often anglicized as Hod, Hoder, or Hodur) is a blind god and a son of Odin and Frigg in Norse mythology. Tricked and guided by Loki, he shot the mistletoe arrow which was to slay the otherwise invulnerable Baldr.

Idun

Idun ("She Who Renews") is the Norse Goddess of youth Who grows the magic apples of immortality that keep the Gods young. Her husband Bragi is God of poetry. Loki, the God of mischief and fire, was once responsible for arranging Her abduction by the giant Thajazi. Without Her apples, the Gods soon began to age, and threatened Loki until He agreed to rescue Her, which He accomplished by borrowing Frejya's falcon robe and fleeing with Idun who He had changed to a nut. Alternate spellings: Idunn, Iduna, Idhunna

Kvasir

Kvasir is referred to as the “wisest of the gods” in The Binding of Loki. It is he who comes up with the plan to fish Loki out of the water using the net he fashioned from Loki’s own design. It is not entirely clear whether Kvasir is a god. In the Mead of Poetry, he is “created” from the spittle of the gods.

Loki

Loki was a mischievous god who could shape-shift and can take up animalistic forms. He conceived a scheme to cause the death of Baldr. Upon learning that mistletoe was the only thing that could hurt Baldr, he placed a branch into the hands of the blind god, Hodr, and tricked him into throwing it at Baldr, killing him. Loki, the Trickster, challenges the structure and order of the Gods which is necessary in bringing about needed change. In the Prose Edda Snorri Sturluson writes that Loki: is handsome and fair of face but has an evil disposition and is very changeable of mood. He excelled all men in the art of cunning, and he always cheats. He was continually involving the Aesir in great difficulties and he often helped them out again by guile. Neither an Aesir or a Vanir, he is the son of two giants and yet the foster-brother of Odin. Loki embodies the ambiguous and darkening relationship between the gods and the giants. He is dynamic and unpredictable and because of that he is both the catalyst in many of the myths and the most fascinating character in the entire mythology. Without the exciting, unstable, flawed figure Loki, there would be no change in the fixed order of things, no quickening pulse, and no Ragnarok. He is responsible for a wager with a giant which puts Freyja into peril (Myth 3) but by changing both shape and sex (characteristics he has in common with Odin) he bails her out. In Myth 10 he shears Sif’s hair which is more mischievous than evil, but he makes amends in the end. In Myth 8 his deceit leads to the loss of the golden apples of youth… but he retrieves them again. He helps the Gods and gets them out of predicaments, but spawns the worst monsters ever seen on the face of the Earth: Fenrir, Jormungand, the Midgard Wyrm. His other children include the goddess Hel (Hella, Holle), and Sleipnir, Odin’s 8-legged horse. It is now generally accepted that he is not a late invention of the Norse poets, but an ancient figure descended from a common Indo-European prototype and as such, Loki’s origins are particularly complex. He has been compared to several European and other mythological figures, most notably the Trickster of Native American mythology. As the myths play out, the playful Loki gives way to a cruel predator, hostile to the gods. He not only guides the mistletoe dart that kills Balder but stands in his way on his return from Hel (the citadel of Niflheim). His accusations against the gods at Aegir’s feast (Myth 30) are vicious. He is an agent of destruction causing earthquakes. And when he breaks loose at Ragnarok, Loki reveals his true colors; he is no less evil than his three appalling children, the serpent Jormungand, the wolf Fenrir and the half-dead, half-alive Hel (Myth 7), and he leads the giants and monsters into battle against the gods and heroes.

Mani

Máni (Old Norse "moon"[1]) is the personification of the moon in Norse mythology. Máni, personified, is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson. Both sources state that he is the brother of the personified sun, Sól, and the son of Mundilfari, while the Prose Edda adds that he is followed by the children Hjúki and Bil through the heavens. As a proper noun, Máni appears throughout Old Norse literature. Scholars have proposed theories about Máni's potential connection to the Northern European notion of the Man in the Moon, and a potentially otherwise unattested story regarding Máni through skaldic kennings.

Njord

Njord is the God of the wind and fertility as well as the sea and merchants at sea and therefore was invoked before setting out to sea on hunting and fishing expeditions. He is also known to have the ability to calm the waters as well as fire. Njord, one of the Vanir gods, was first married to his sister Nerthus and had two children with her, Frey and Freyja. His second wife was Skadi (Skade), a Giantess. When Skadi’s father was killed by the Aesir she was granted three “acts” of reparation one of which was to let her choose a husband from among the gods. She could pick her new husband, but the choice had to be made by looking only at the feet. She picked Njord by mistake, assuming his feet belonged to Balder. Njord and Skadi could not agree on where to live. She didn’t like his home Noatun at the Sea, and he didn’t like hers Trymheim, in the mountain with large woods and wolves, so they lived the first half of the year in Noatun and the other half in Trymheim. Njord is said to be a future survivor of Ragnarök in stanza 39 of the poetic Edda:

“In Vanaheim the wise Powers made him and gave him as hostage to the gods; at the doom of men he will come back home among the wise Vanir.”

Odin

The supreme deity of Norse mythology and the greatest among the Norse gods was Odin, the Allfather of the Æsir. He was the awe-inspiring ruler of Asgard, and most revered immortal, who was on an unrelenting quest for knowledge with his two ravens, two wolves and the Valkyries. He is the god of war and, being delightfully paradoxical, the god of poetry and magic. He is famous for sacrificing one of his eyes in order to be able to see the cosmos more clearly and his thirst for wisdom saw him hang from the World Tree, Yggdrasil, for nine days and nine nights until he was blessed with the knowledge of the runic alphabet. His unyielding nature granted him the opportunity to unlock numerous mysteries of the universe. Odin or, depending upon the dialect Woden or Wotan, was the Father of all the Gods and men. Odin is pictured either wearing a winged helm or a floppy hat, and a blue-grey cloak. He can travel to any realm within the 9 Nordic worlds. His two ravens, Huginn and Munin (Thought and Memory) fly over the world daily and return to tell him everything that has happened in Midgard. He is a God of magick, wisdom, wit, and learning. In later times, he was associated with war and bloodshed from the Viking perspective, although in earlier times, no such association was present. If anything, the wars fought by Odin exist strictly upon the Mental plane of awareness; appropriate for that of such a mentally polarized God. He is both the shaper of Wyrd and the bender of Oorlog; again, a task only possible through the power of Mental thought and impress. It is he who sacrifices an eye at the well of Mimir to gain inner wisdom, and later hangs himself upon the World Tree Yggdrasil to gain the knowledge and power of the Runes. All his actions are related to knowledge, wisdom, and the dissemination of ideas and concepts to help Mankind. Odin can make the dead speak in order to question the wisest amongst them. His hall in Asgard is Valaskjalf (“shelf of the slain”) where his throne Hlidskjalf is located. From this throne he observes all that happens in the nine worlds. He also resides in Valhalla, where the slain warriors are taken. Odin’s attributes are the spear Gungnir, which never misses its target, the ring Draupnir, from which every ninth night eight new rings appear, and his eight-footed steed Sleipnir. He is accompanied by the wolves Freki and Geri, to whom he gives his food for he himself consumes nothing but wine. Odin has only one eye, which blazes like the sun. His other eye he traded for a drink from the Well of Wisdom and gained immense knowledge. On the day of the final battle, Odin will be killed by the wolf Fenrir. Just as a point of curiosity: in no other pantheon is the head Deity also the God of Thought and Logic. It’s interesting to note that the Norse people set such a great importance upon logic. The day Wednesday (Wodensdaeg) is named for him.

Sif

Sif is the Norse Goddess of the grain Who is a prophetess, and the beautiful golden-haired wife of Thor. Thor is the thunder God and frequent companion of Loki, as He makes the perfect patsy, being not too bright. Sif is of the elder race of Gods or Aesir. She is a swan-maiden, like the Valkyries, and can take that form. By Her first marriage to the Giant Orvandil, Sif had a son named Ullr ("the Magnificent"), Who is a God of winter and skiing. By Her second husband Thor, She had a daughter, Thrudr ("Might"), a Goddess of storm and clouds and one of the Valkyries, and two sons, Magni ("Might") and Modi ("Anger" or "The Brave"), who are destined to survive Ragnarok and inherit Mjollnir from Thor (though some say the Giantess Jarnsaxa "Iron Sword" is their mother). Sif is famous for Her very long, very golden hair. One night, Loki, who just couldn't resist a little chaos and mischief, snuck into Her chamber and chopped it all off. A sobbing and horrified Sif went straight to Her husband, Who in His rage started breaking Loki's bones, one by one, until finally He swore to make the situation right. So, Loki went to the dwarves and persuaded them to make not only a new head of magic hair for Sif from pure gold, but also a magical ship and a spear. But Loki could not resist pushing His luck, and made a wager with two other dwarves, Brokk and Sindi, daring them to make better treasures. Loki was so sure of the outcome that He had let His own head be the prize. Underestimating the dwarves' skills (or the depth of their hatred for Him), He suddenly realized with a shock that Brokk and Sindi were winning! In desperation He changed Himself into a horsefly, biting and pestering the dwarves while they worked. Despite this they managed to produce several treasures, the most famous of which was Mjollnir, Thor's Hammer. The Gods were then called to arbitrate and declared Brokk and Sindi the winners. Loki promptly disappeared. When He was tracked down, He was again given to the dwarf brothers, but this time Loki agreed, yes, they had a right to His head, but the wager had said nothing about His neck. Frustrated with this "logic," the dwarves had to content themselves with sewing His lips shut. The new head of golden hair was given to Sif, where it magically grew from Her head just as if it were natural. Her golden hair is said to represent the wheat of summer that is shorn at harvest-time.

Skadi

Skadi is the Goddess of Winter and of the Hunt. She is married to Njord, the gloomy Sea God, noted for his beautiful bare feet (which is how Skadi came to choose him for her mate.) Supposedly the bare foot is an ancient Norse symbol of fertility. The marriage wasn’t too happy, though, because she really wanted Balder for her husband. She is the goddess of Justice, Vengeance, and Righteous Anger, and is the deity who delivers the sentence upon Loki to be bound underground with a serpent dripping poison upon his face in payment for his crimes. Skadi’s character is represented in two of Hans Christian Anderson’s tales: “The Snow Queen” and “The Ice Princess.”

Sol/ Sunna

Sól is the Norse Goddess of the Sun, also known as Sunna, though some hold that Sól is the mother and Sunna Her daughter. In Norse mythology, the Sun is female while the Moon is male. When the world was created from the body of the dead giant Ymir by the triad of Odin, Vili, and Ve, the Sun, Moon and Stars were made from the gathered sparks that shot forth from Muspellsheim, the Land of Fire. Sol ("Mistress Sun"), drives the chariot of the Sun across the sky every day. Pulled by the horses Allsvinn ("Very Fast") and Arvak ("Early Rising"), the Sun-chariot is pursued by the wolf Skoll. It is said that sometimes he comes so close that he can take a bite out of the Sun, causing an eclipse. Sol's father is Mundilfari, and She is the sister of Måni, the Moon-god, and the wife of Glaur or Glen ("Shine"). As Sunna, she is a healer. At Ragnarok, the foretold "Twilight of the Gods" or end of the world, it is believed the Sun will finally be swallowed by Skoll. When the world is destroyed, a new world shall be born, a world of peace and love, and the Sun's bright daughter shall outshine Her mother.

Thor

Thor was Odin’s most widely known son. He was the protector of humanity and the powerful god of thunder who wielded a hammer named Mjöllnir. Among the Norse gods, he was known for his bravery, strength, healing powers and righteousness. Tyr is the ancient god of War and the Lawgiver of the gods. The bravest of the gods, it is Tyr who makes the binding of Fenrir possible by sacrificing his right hand. Thor, also known as the Thunderer, was a son of Fjorgyn (Jord) and Odin by some, but among many tribes Thor supplanted Odin as the favorite god. He is the protector of all Midgard, and he wields the mighty hammer Mjollnir. Thor is strength personified. His battle chariot is drawn by two goats, and his hammer Mjollnir causes the lightning that flashes across the sky. Of all the deities, Thor is the most “barbarian” of the lot; rugged, powerful, and lives by his own rules, although he is faithful to the rest of the Aesir. The day Thursday (Thorsdaeg) is sacred to him.

Tyr

Tyr also seems to be a god of justice. His name is derived from Tiw or Tiwaz an Tacticus and other Roman writers have equated this character to Mars, the receiver of human sacrifice. His day is Tuesday. Tyr was the son of Odin though he is made out to be the son of the giant Ymir. Like Odin, he has many characteristics of the earlier Germanic gods of battle. Parallels in other mythologies along with archaeological discoveries relating to a one-handed god, suggest that this character is very old and was known in Northern Europe somewhere between one and two thousand years before Snorri Sturluson included it in his Prose Edda. Similarities can be found in the one-handed Naudu in Irish mythology and in Mitra, just god of the day, of Indian mythology.

Ve

Ve is one of ancient Scandinavian gods and, together with Odin and Vili, the son of the primordial pair of giants Bor and Bestla. The three brothers created heaven and earth from the slain body of the primeval being Ymir and built the twelve realms. They also created Ask and Embla, the first pair of humans.

Vili

In Scandinavian myth, one of the primordial gods, brother of Odin and Ve. The three of them were responsible for the creation of the cosmos, as well as the first humans.

Vidar

Vidar was another son of the supreme god and Grid (a giantess), and his powers were matched only by that of Thor.

Vali

He was born a fully-grown man. Little is known about Vali, except that he is a son of Odin and his giant mistress Rind. When Balder was killed unintentionally by his twin brother Hod, Vali was born to avenge his death.

“In the west Rind will give birth to Vali. Merely one night old he will avenge the son of Odin.

He will not wash his hands, nor will he comb his hair until Balder’s murderer burns at the stake.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Kindness

Ivar x Reader

Part 1 here!

Warnings: abuse, angst

Taglist: @steadypiepsychicflower @cbouvier23 @holydream@fireismysaftey @funmadnessandbadassvikings @attorneyl @lotusgirl16

You knew what would happen if you returned home. It happened whenever you were late coming home from chores, or whenever you entertained the idea of running away. Inevitably you would slink back to your parents house knowing you were worthless and would find no luck outside of Kattegat. You were nothing until your parents married you off. Owned by them until you were owned by a husband.

But you did not return home that night. Ivar wouldn't let you.

You knew trouble was brewing when you were invited to breakfast. Sitting at the table surrounded by Ivar's family, the Queen included, and their servants was unnerving. You did not feel the desire to be waited on by thralls. But you were too afraid to speak up. The Ragnarsson's hospitality may not last long.

"My son tells me you were y/n Alfsdottir," the queen spoke up. You shrunk in your seat. Ivar's hand stopped you from disappearing completely.

"Well, is she right or not?" Ivar muttered. It was suppose to be encouraging.

"Y-yes...my queen, I am," you replied meekly. Aslaug swallowed her mead, staring you down inquisitively. You couldn't tell what she was thinking or looking for.

"Your father has been gone almost the whole harvest. It is almost winter...is your mother expected to be alone until spring?"

"My father is a merchant trader. He is often gone for a very long time. My mother and I manage without him." Your hands start to sweat. You feel the eyes of all the sons of Ragnar shifting between you and the queen. Ivar's hand has disappeared from your back; you've become wobbly even in a chair.

"This mother of yours...Ingrod. She does not manage without her husband well it seems," Aslaug quipped. "She beats you like a common slave. And you do nothing to stop her."

You swallowed with a terrified look in your eye. It is normally taboo to speak so bluntly of family affairs. "I...I pray to Freyja often...it helps."

"Mother." The queen's eyes dart away from pressing into yours to look at her youngest son. Ivar was fuming in his seat, glaring full force at Aslaug's suddenly innocent expression.

"Enough."

She knew what he meant. She would keep talking, but would have to keep her subtles to herself. Her eyes shift back to you friendly as ever. It made you queasy how easily she could flip the switch.

"Well y/n, I'm happy my son has welcomed you here...but if your mother should come collect you, I cannot stop her."

Head hung in defeat, you decided trying to eat would make you sick. You weren't hungry at all anymore...the fear and anxiety welling up inside you over going "home" held your throat tight.

"She's right," Ivar muttered, ducking slightly to catch your eyes from your withered posture. "You are a free woman. You should leave if your family is this cruel to you."

"I have nowhere to go," you whispered. Ivar sat back and thought about this to himself. Why was he putting so much effort into such a person? A sad, abused young woman who he'd just met...he'd watched you before when you stole, being a little sneak, hiding in the shadows. You had potential. He could see it...maybe you were just his redemption project to feel better about himself.

"Not everyone is going to hurt you anymore."

You glanced at him as he ate and acted as if he hadn't just spoken so softly. But you heard him clear as day, and wondered what exactly he meant...

The doors of the Great Hall were suddenly filling with people. Aslaug stood from her table to see what the commotion was; her guard was on alert and ready. This was an unwelcomed or unsummoned crowd. Leading her small mob of nosy gossips was Ingrod...your mother.

“My lady queen!” Ingrod addressed Aslaug with a bow. Aslaug did not flinch or change her icy look. “I’ve heard from peers you found my missing daughter. I am so sorry she has burdened you. I’ve come to collect her.”

“She has not burdened us,” Aslaug said flatly. “But what she has told me has burdened me greatly.”

With wide eyes you look over at your mother; her eyes turned red in your mind. She was gnashing her teeth thinking what to say next, and imagining how to punish you for embarrassing her like this.

“She is a notorious liar my queen. She will say anything for pity,” Ingrod snapped. “She is trouble whenever my husband is away. Giving her time to any man who comes to our door, stealing my things-”

Your mother goes on about the kind of daughter you are while tears well up in your eyes. Nobody but Ivar notices that while your mother rants, she inches closer and closer to your side of the table. By the time she’s reduced your character to vermin she reaches out one of her clawed hands to snatch you by the wrist; Ivar’s dinner knife comes down clean into the table between you two.

“Ivar!” Aslaug chirped.

“Do not touch her. Ever,” Ivar growled. Ingrod’s kindly face twisted into something bitter and vicious.

“I can touch her all I want, Prince Ivar the Boneless. I birthed that little beast sitting next to you, and she belongs to me.”

“Y/n is a free-”

“Ivar,” the queen addressed more seriously. Ivar let his hand off the dinner knife embedded in the table and wrapped an arm around your shivering shoulders. “Ingrod, when is your husband Alf to return?”

“My husband?” your mother barked. She tried to soften her voice to no avail when addressing the queen. “He is returning in a week or so. He’s a trading man and travels much of the time, and leaves the care of our daughter to me.”

“Care...” Ivar snorted. Aslaug shot him a look and he was quiet again.

“Well, when he returns, I’d like to speak to you both,” Aslaug said. Ingrod’s expression zeroed in on you.

“About?”

“That is to be discussed,” Aslaug said. “For now...y/n is to return with you. She is your daughter.”

“Good.”

Your mother’s expression hadn’t softened; the room felt ice cold in tension. The queen felt disrespected, and your mother...she couldn’t wait to have you home.

“If your daughter is property to you, what price should I pay?” Ivar said casually. The room started getting warmer; you were lightheaded. Ingrod looked bewildered at such a question.

“She is a free woman my prince. But if you want her for a slave...” your mother chirped sweetly. It made you want to gag; Ivar kept a hand over your shoulders and slid his free one into your lap, eyeing your mother’s bitter expression.

“No. I want her as a wife. So, how much?”

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter XVIII

The Frowe (Freyja)

The Frowe is probably the best-known and most beloved of the goddesses today. As mistress of magic and goddess of sexual love, she kindles the imagination and sparks the heart. Whereas that other great goddess, Frija, is wholesome and safe, the Frowe is sweet, wild, and dangerous. Though Fro Ing is her twin brother and their mights mirror each others', the two of them show that might forth in very different ways.

Her name, Freyja or the Frowe, is a title meaning "Lady". Though she has many other names in the Old Norse sources, it is not known which of them (if any) was her true name. In Scandinavia, the title was associated so strongly with the goddess that it, like her brother's title "Freyr", was dropped wholly from ordinary human use and preserved only as a name; but in Germany, where she either was not known or was known by a different name, the cognate word "Frau" has continued in human use to the modern day. To the Scandinavians, however, there was apparently one "Lady", and one "Lord", whose titles could be used by no one else (it was only towards the end of the Viking Age that the word "húsfreyja", "house-Freyja", came into use for the lady of the house; this may have stemmed from skaldic kennings, in which a woman might for instance be called "Freyja-of-necklaces", or, since the form húsfrú also appears, have been borrowed from the corresponding German title). These titles clearly show the love and respect which our forebears felt towards the Frowe and her twin. In modern times, it has often been suggested that our "Lady" and "Lord" are the original pair whose memories survived in Northern European folklore to be called upon as the Wiccan Lady and Lord today. This fits well with much of what we know of the Frowe and Fro: as well as being sister and brother, they are also lovers, as is spoken of in Lokasenna. The possibility of a likeness between Freyr and the Horned One is also mentioned in the chapter on "Fro Ing".

The main difference between the Frowe and the Wiccan Lady is that the Frowe is not motherly in any way. Because she is the best-known Germanic goddess, folk have often thought of her as possibly being a Germanic reflection of the Mother-goddess archetype. Unlike Frija, however, we never see her giving fruitfulness to folk, nor does she appear in a motherly way to either deities or humans. Only once does she appear as a patron of childbirth: in Oddrúnargratar, the childbirth-blessing calls on "kind wights, Frigg and Freyja and many gods". However, this poem is generally thought to be among the youngest of Eddic lays; Hollander actually suggests that the invocation to "Frigg and Freyja" is a deliberate archaism put in to give the poem a heathen flavour (The Poetic Edda, p. 279). Although Snorri tells us that the Frowe has two daughters, both their names (Hnoss and Gersimi) are ordinary words for "treasure". In fact, they are mentioned only twice in skaldic poetry, where actual treasures are called "Freyja's daughter". If it is not the case (as it may well be), that these references simply speak of the belief that gold comes from the Frowe's weeping and treasure is therefore "her daughter", these maidens may be understood as embodiments of her might as a goddess of wealth; one might perhaps ask the Frowe for "the love of her daughters".

To the Norse, Freyja was a goddess of riches, whose tears fell to the earth as gold and whose most common appearance in skaldic poetry is in kennings for "gold". Although many of the god/esses are givers of wealth, she seems to be first among them. Here we see one of the ways in which the Frowe and Fro Ing work differently: the riches he gives are those of the fruitful fields and beasts, while those she gives are the worked gold - we might say now that Fro Ing is the god to call on to bring the harvest of long-term investments about well and to look after real estate deals, while the Frowe is the goddess to ask about cash-flow.

The Frowe is probably best-known, however, as a goddess of love and sexuality. The etin-maid Hyndla says to Freyja "(You) ran, ever-longing, after Óðr, you let many creep beneath your fore-skirt - atheling-friend, you leap about at night like Heiðrún among the goats" (Hyndluljóð 47). Loki says that she has slept with "all gods and alfs in the hall" (Lokasenna 30), which seems to be true. Unlike Frija and Wodan, to who their chosen humans are children or foster-children, the Frowe's heroes are her lovers; the Eddic poem Hyndluljóð gives us a very clear description of her beloved Óttarr, whom she has changed into a boar which she rides to the rock-hall of the giantess Hyndla. This sort of "nightmare-riding" is typical for witches throughout the Germanic world. Unlike the men of later folk-tales, however, Óttarr is not only apparently willing to be ridden, but gets some good from the faring - the account of his lineage, which he must use to win his inheritance. Still, the Frowe's love is as dangerous as it is wildly exciting: Hyndla says that Freyja is riding Óttarr on his "slain-faring" (í valsinni), and since the etin-woman sees clearly otherwise, we may suspect that the goddess' lover was not long-lived.

The story of Óttarr, who built a harrow for Freyja and reddened it with blood until the holy fires (or the heat of Freyja's might) had turned the stones to glass, also suggests that the Frowe was not only worshipped by women, but had her own given godmen. Like the gyðja who was Freyr's wife in Gunnars þáttr helmings, these men may well have been seen as the Frowe's husbands or lovers. Some of the mysterious deaths of Yngling kings, such as that of Agni, who was strangled with a necklace by his wife, or Aðils, who, touched by a witch's magic, fell off his horse at the dísablót (goddesses' blessing - see "Idises"), also suggest the possibility that these Ing-descended kings died as holy gifts to Freyja.

Snorri tells us that Freyja is particularly fond of love songs (mannsöngr), of a type we know to have been outlawed in Iceland even before the conversion; and the pages of heathen publications are often brightened by love-songs written for Freyja. Such a song of your own is a fitting gift for her: one copy might be written out in runes and burned for her while you read the other aloud to her.

It is strongly suspected that the Frowe's sexual character led to the suppression of much of her lore by christianity. however, some pieces did survive, though in a diluted and moralizing form. The best-known of these is the tale (from Sörla þáttr in Flateyjarbók) of how she saw four dwarves forging a necklace (the Brísingamen) and traded four nights of her love for it. Alice Karlsdóttir reads the tale thus:

The story is usually told to demonstrate Freyja's 'immorality' or bawdy humour. This always seemed rather unfair to me. After all, when writers discuss Odin and how he slept with Gunnlod on three nights in order to win the mead of poetry, they praise his efforts at winning wisdom, but when Freyja, a goddess, does pretty much the same thing, they say, "What a shameless hussy!"

Freyja's necklace is not, of course, just a pretty piece of vanity, but rather a powerful symbol of the goddess' powers of fertility and life. Giants are continually trying to win or steal Freyja for themselves, not just because she's a good lay, but because her powers contain the essence of the life force itself and sustain the well-bring of Asgard and the rest of the worlds. the story of how Freyja got the Brisingamen is a story of her quest for wisdom and power, every bit as much as Odin's adventures are...

One of Freyja's powers seems to be a mastery of material manifestation, the infusing of the physical world with the spiritual. Freyja not only masters the senses, she revels in them and shows that physical existence itself is a wondrous thing. I always sort of imagined that the dwarves didn't create the necklace until after Freyja slept with them, that their intercourse was necessary to inspire the dwarves to be able to make the Brisingamen in the first place. Freyja, on the other hand, discovers the powers of the material world and how to control and shape them.

The goddess' necklace or girdle is an emblem that goes back to the Stone Age, when slender amulets of schist, given human form only by the careful carving of necklaces, were carried about (Gløb, Bog People p. 159). As mentioned in "The Stone Age", amber necklaces of a size only a goddess could have worn were being given to bogs at the same time. The Bronze Age kneeling goddess-figurine who drives a small ship with a snake leashed beside it wears only a necklace and a string-skirt; the same is true of the little female acrobat/dancer from the same period. The huge Swedish gold collars of the Migration Age (discussed in the historical chapter), were clearly also holy, and by this period it is quite possible that they could have been given specifically to the Frowe, although god-figures with collars carved on their necks have also been found. The necklace is the sign of the world's ring; Freyja's winning of the Brisingamen is one of the strongest reasons to think of her as an earth-goddess like her mother Nerthus, and therefore, though there is nothing in the Norse sources to suggest it, perhaps also being one of the goddesses who makes the world fruitful. It is certainly the sign of her power. We do not know what it actually looked like: the name "Brísingamen" can either be read as "the necklace (or girdle) made by the fiery ones (Brísings, presumably the name of the dwarves)" or as "the fiery necklace (or girdle)". We know that gold is called fire in kennings, so that the Brísingamen is likeliest to have been made of gold, though it is often pictured in modern times as being amber or at least set with amber. In Úlfr Uggason's poem Húsdrápa, the Brísingamen is called hafnýra, "harbour-kidney", a kenning which may also hint that amber was a part of the necklace, since amber was normally gathered along the seashore. The workings of the four dwarves might hint at a four-ringed collar, or a four-stranded necklace - especially since, seen on a level plain, the cosmos also has four concentric rings (the Ases' Garth, the Middle-Garth, the sea around the Middle-Garth, and the Out-Garth - see "Worlds"). The Frowe's necklace would then be the embodiment of her might through all the realms. A small Swedish pendant from Östergotland (late Viking Age) is often thought to represent Freyja: it shows a remarkably large-breasted woman wearing a four-layered necklace and seated inside a ring.

As the bearer of fiery life-might, the Frowe is greatly needed by the other god/esses; etins often seek her in marriage, as was done by the builder of Ase-Garth's walls and the giant Þrymr, who stole Þórr's Hammer to use it as a bargaining point in getting her.

The Frowe is first thought to have come among the Ases as the witch Gullveigr ("Gold-Intoxication"), whose fate started the war between the Ases and the Wans: "when Gullveigr was studded with spears and burned in Hár's hall; thrice burned, thrice born, often, not seldom, but yet she lives" (Völuspá 21). Here we see what is clearly a Frowe-initiation similar to that of Wodan's hanging on the tree: while he is hanged and stabbed, she is stabbed and burnt, each of them slain by the means which is holiest. Just as Wodan won the runes, the Frowe came forth with the full lore of her own seiðr: "Heiðr hight she, when she came to houses, spae-wise völva, she knew magic; she worked seiðr as she knew how to, worked seiðr, playing with soul - she was ever beloved to wicked women" (Völuspá 22). The name "Heiðr" means either "the Glorious/Bright One" or "the Heath-Dweller": we can see her wandering freely through heath and house, glowing with the seething fires of her threefold burning and rebirth. Heiðr is seen in modern times as the "older woman" aspect of Freyja, with the fiery might of her gold and sex sublimated into the wisdom and magical might of the witch. The stone we associate with her now is jet, and the colours are black and white interwoven so that they look gray from a little way off. Eiríks saga ins rauða mentions that the seeress was fed a meal of the hearts of several sorts of animals; as Heiðr is the great völva (even as Wodan is Fimbulþulr, the great thule), it is thought today that hearts are the meat which is holiest to Heiðr.

Snorri also tells us in Ynglinga saga that Freyja taught the art of seiðr to the Ases; Thorsson sees this as an exchange whereby Freyja learned the runes from Óðinn and he learned seiðr from her. In any case, the situation is, again, comparable: as Wodan teaches the craft of the runes after his initiation, so Freyja teaches the skill of seiðr after hers - not only to the Ases, but, as Völuspá suggests, to humans as well.

The Frowe is married to a god called Óðr - the noun from which the adjectival "Óðinn" is derived. The folklore of the Wild Hunt suggests that "Wod" was an older form of the name *Woðanaz; de Vries also compares the Óðr-Óðinn to the other surviving pair of noun-adjective forms, Ullr-Ullinn ("Contributions to the Study of Othin"). There is little doubt that Óðr and Óðinn were the same god, although this identity seems to have been forgotten by the end of the Viking Age; it is probably very old. The wedding between Óðr and Freyja is, at the least, a very open one: the way in which the Frowe is sought as a bride by etins suggests that she is thought to be effectively single. Sörla þáttr describes her as Óðinn's mistress, rather than his wife. The two of them clearly work together - they mirror one another in many ways and share many of the same realms - and both being quite sexual deities, it would be surprising if their relationship was not shown forth as a sexual one. However, the Frowe seems to be too independent to tie herself to any single male for long; though she wandered weeping after Óðr when he left her, there is no doubt that sexual faithfulness was never part of the arrangement.

The Frowe is also a battle-goddess: one of the names of her hall is Folkvangr ("Army-Plain"), and there "Freyja rules the choices of seats in the hall: she chooses half the slain every day, and Óðinn has half". It is not sure whether by "choosing the slain", the Grímnismál speaker meant this in the usual sense (as when used for the walkurjas, Wodan, and Hella) of choosing who among the living warriors shall be slain in that battle, or whether it means that the Frowe gets her choice of those among the fallen who she wants for her hall. In either case, she is certainly a goddess of death and specifically the battle-dead: the men she wants are clearly the best of heroes. What she does with them is never told to us, whether they fight beside the einherjar at Ragnarök or stay with Freyja, who may survive the battle (in Ynglinga s. ch. 8, Snorri tells us that "Freyja then kept up the blessings, for she alone lived after the gods", though since he has euhemerized them all and given them very different deaths from those they meet at Ragnarök, this may not be a reliable indicator). As seen in the tale of Gullveigr, she is also a cause of strife as well: wealth and women were two of the most common causes for fighting among the Germanic folks. The two chief social roles of women in the Icelandic sagas were as frith-weaver and strife-stirrer: Frija embodies the first, the Frowe the second. Here, the Frowe and Fro Ing complement each other rather than working in the same way: the Eddic poem Grottasöngr shows how the two, strife and frith, need each other. When Fróði harnesses the etin-maids Fenja and Menja to turn a magical mill, they grind out gold and frith and happiness; but instead of letting them rest, he tries to keep them working without pausing longer than it takes to sing a lay. Then the scales tip too far: the women become angered and grind out battle and Fróði's death, and the balance is evened again. The Frowe stirs up Fro Ing's frith; Fro Ing stills her strife; thus challenge and rest are balanced out.

According to Snorri, the Frowe's hall is also called Sessrumnir, "Roomy-Seated" - which it would need to be as a hall of the dead. As is not hard to imagine, the sexes seem to mix freely in the Frowe's realm, warriors and young women alike: when Egill Skalla-Grímsson's daughter Þórgerðr tells of her intention to starve herself beside her grieving father, she says that she will take no food until she sups with Freyja.

Like her brother, the Frowe has the swine as a holy animal, and rides on a gold-bristled boar (hers is called Hildisvín, "Battle-Swine") which was made by dwarves. The Yule boar is holy to her, as to him. One of the Frowe's own by-names is Sýr, "Sow", which suggests not only her fruitfulness and sexuality, but her more frightening side: the swine is, after all, a carrion-eater, and sows are proverbially known for eating their own piglets at times.

Like Frija, the Frowe travels through the worlds by putting on a falcon-hide and faring forth in that shape. Though none of the myths show her actually using it - we only know of it because she lends it to Loki - the falcon seems to be the womanly match to the manly eagle (a shape taken by Wodan and, quite often, by etins). This shows her swift-faring through the worlds; the falcon is clearly a holy bird of hers, in her most active shape when she is not only fiery, but ærial. Some of the birds of prey which appear so often in Germanic art may be falcons rather than eagles, but our forebears' art was so stylized that there is no way to tell which is which; only the hooked beaks distinguish birds of prey in general.

The Frowe is also well-known to have a wain which is drawn by two cats. Every so often the question of what sort of cats these were, or whether they were actually felines and not some other creature, comes up. Grimm mentions that the Old Norse word fres "means both he-cat and bear, it has lately been contended, not without reason, that köttum may have been subsituted for fressum, and a brace of bears have been really meant for the goddess" (Teutonic Mythology, II, p. 669). It has also been suggested several times that the image of Freyja in her cat-drawn wain was borrowed from the southern Cybele, whose chariot was drawn by lions. There is also a special connection between seiðr and cats: the seeress in Eiríks saga ins rauða is described as wearing catskin gloves, which has spurred many people to hope that the Old Norse word köttr, "cat", did not really mean cat. Alternate suggestions have included bears (gib-cats), hares, and various sorts of ermine- and weasel-type creatures. However, wild felines such as the lynx have been native to Scandinavia at least since the earliest human settlements, and the first skeletal evidence of house-cats dates from the earlier part of the Iron Age (Scandinavian Saga, 131). Further, the burial goods of "Queen Asa" (the Oseberg queen) include elaborately carved vehicles (generally thought to be for cultic processions) on which cat-images are carved. In one case, the sledge-posts are unquestionably cat-heads; the end panel of the wagon shows a repeated picture of a cat who is apparently fighting or dancing with a snake, while either shielding her eyes with one paw or just revealing them (perhaps to awe the snake by her gaze?). These cats are probably house-cats or small European wildcats, as they do not have the tufted ears of the lynx. A little amber cat-figurine was also found lately in the archaeological excavations at the late Viking-Age site on Birka. All of this, particularly the cat-head posts from Oseberg, suggest very strongly that there is every reason to think that the belief is native rather than foreign, that Freyja's cats are indeed house-cats - and so were the seeress' gloves. No names for these cats have survived in any sources, but in her book Brisingamen (which is highly recommended to all Ásatrúar, especially those interested in Freyja), Diana Paxson suggests the names "Trégull" ("Tree-Gold", or amber) and "Býgull" ("Bee-Gold", or honey) for them. Some will be amused, and others appalled, to note that certain less-reliable books on Norse heathenism are already solemnly reporting these fictional names as part of authentic Teutonic tradition...

The Frowe herself was known by other names in Scandinavia: Snorri gives us the names Hörn (which is etymologically tied to "flax"), Sýr ("sow"), Gefn ("giver"), and Mardöll ("Sea-Brightness" - another name which may refer to amber, or else to gold, which is often called "fire of the sea"). These names are likeliest to have been local titles for either the Frowe or other goddesses who were so like her that it made no difference.

The Frowe's stone is amber, a connection which may go back to early days. Amber is especially beloved by Northern folk; it is "the gold of the North". In our forebears' time, necklaces of amber were probably a status symbol as much as anything; and even today at Teutonic rites, one can often see women (and occasionally men) hung with as many strands of amber as they are able to buy. Other stones which the name "Brísingamen" and the Frowe's flame-being suggest are fire agates and fire opals; gold is clearly her metal, if you can get it.

The elder-tree (whose very name means "fire") is especially close to her; yarrow and dill, as traditional "witches' herbs" also belong to her. Her flower is the rose, especially the Northern European wild rose or "dog-rose". One Northern German church is supposed to have been built at "Freyja's spring"; when the church was rebuilt after the last World War, the roots of the dog-rose which had grown beside it were shown to be over a thousand years old. The legend of "Freyja's spring" may have been a romantic product of the eighteenth or nineteenth century, but the flower itself surely shows her being, being both the sweetest and the thorniest of blooms.

The Frowe is especially a goddess of women who do as they will and love as they will without worrying about social constraints or anything else. More than any other goddess, she shows the right of women to rule over their own bodies, to love - or not love - as they choose. Indeed, according to Þrymskviða, it was easier for the Ases to get Þórr to put on women's clothing and go into Etin-Home as a bride than for them to make Freyja wed against her will!

The necklace is the sign which is traditionally that of the Frowe's might, though there is no one picture of it that stands as "her symbol". In A Book of Troth, Thorsson suggests that "Freya's Heart (the basic heart-shape) is the sign of the blessings of the goddess Freya, and is the symbol of those given to her mysteries" (p. 112). This is extrapolated from the reading of this symbol as showing the female genitals and/or buttocks: as the stylized picture of womanly sexuality, the heart (with or without the phallic arrow piercing it), is clearly fitting to the Frowe.

It is thought in modern times that the Frowe likes sweet drinks, especially berry liqueurs and German wines of the Auslese, Beerenauslese, and Trockenbeerenauslese class. One liqueur in particular, Danziger Goldwasser (which has actual flakes of high-karat gold foil in it), is felt to be especially fitting to her.

Contributors

Stephan Grundy, "Frigg and Freyja"

Alice Karlsdóttir, from "Freyja's Necklace", Mountain Thunder #10, pp. 21-22.

Diana Paxson (esp. Heiðr and cat-names)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Sunday gets its name from the Norse and Germanic goddess Sol or Sunna! Also see Baldr Odin's son." "The Sun"s name was Sól Alf (Alf being the true name for Elf), the Alfr are our male ancestors. This means the sun, a goddess is alight with all our souls!" -Skydin "The Goddess Frigg is sharing through me. I am grateful. What's so special about the Free?! What has to you the most meaning Friends or Family? How about Home?! And offspring? All these gifts come to us Free?! Thank Frigg (/Freeg/) and Freyja!" . . . . . #spiritual #runecalendar #astralprojection #psychic #luciddreams #magick #runes #clairvoyance #freyja #stonehenge #crystals #wicca #sungoddess #chakra #pleiades #mothergoddess #faerie #paganism #heathen #spells #ancientegypt #healing #mythology #reiki #Norse #clairvoyance #goddess #shamanism #celtic #reincarnation #astrology (at New York, New York) https://www.instagram.com/p/CMJJAu9HOMZ/?igshid=3oir33zhcmes

#spiritual#runecalendar#astralprojection#psychic#luciddreams#magick#runes#clairvoyance#freyja#stonehenge#crystals#wicca#sungoddess#chakra#pleiades#mothergoddess#faerie#paganism#heathen#spells#ancientegypt#healing#mythology#reiki#norse#goddess#shamanism#celtic#reincarnation#astrology

0 notes

Note

Can you tell us about freyja's sexual escapades the internet is hiding them from me.

HELL FUCKIN YEAH I CAN listen up about the Lady of Love, Lust, Fertility, War, and Magic

In the Lokisenna (basically the gods are having a party, Loki crashes it and gets trashed, and proceeds to rap battle insult every god/goddess) Loki claims Freja has slept with literally every god (exact words were ‘all of the Aesir and alfs within this hall’, so that probably includes the goddesses too) and a few giants. Freyja’s reaction is basically “Yeah, and??” and Njord, Freyja’s father, chips in with “So?”

(This is the same saga where he points out that Odin has spent time living as a sorceress, practices women’s magic, and implies that Odin’s been the bottom in a few dude/dude sexytimes, to which Odin basically says “Yeah, and???”)

To win the necklace Brisingamen, the most beautiful and splendid necklace in creation, the traded the three dwarves who forged it three nights with her (one night each). (Some modern writers say she traded them three kisses, but nah, she banged the shit out of those guys)

Basically Frejya banged her way through the entire Norse pantheon in between taking the souls of the half of the battlefield slain not claimed by Odin, and while we don’t have specifics save for her liason with the goldsmith dwarves, she goddamn well enjoyed every moment of it.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Destin, Orlög, Le grand Ase

Selon certains érudits le Grand Ase serait à positionner bien plus haut que toute chose. Il serait même supérieur à tous les Dieux et Déesses. Même eux ne lui échappent pas. Non, rien ni personne n'échappe au Destin.

Selon Régis Boyer :

" Quels que soient les textes envisagés, antiques inscriptions runiques, récits d’historiens latins, fragments de poèmes immémoriaux, Eddas, sagas de tous genres – fussent-elles rédigées à l’ère chrétienne scandinave –, formules juridiques, vestiges magiques, partout, toujours s’impose l’originale figure du Destin. Il était au commencement dans l’ébauche des monstres primitifs nés du contact entre chaud et froid, il sera à la fin, à la Consommation du Destin des Puissances (Ragnarök), sans doute préférable à la version Crépuscule des Puissances (Ragnarokkr), et c’est lui qui fera surgir, parmi les prairies toujours vertes du monde régénéré, les merveilleuses tables d’or – un jeu de hasard, sans doute – que les dieux suprêmes, « renés », prisent plus que la bière miellée ou la chair inépuisable du sanglier de la Valhöll. Toute étude de la religion germanique et scandinave qui négligerait ce trait pour se confiner à une description de mythes, à une nomenclature de divinités ou de héros, se condamnerait, par là même, à passer à côté de l’essentiel, c’est-à-dire du sacré : car le sacré chez les anciens Germains, c’est le Destin, le sens du Destin, les innombrables figurations que prend le Destin. Tacite le notait déjà : « Les auspices et les sorts n’ont pas d’observateurs plus attentifs. »

D’un bout à l’autre du domaine germanique résonne la trompette fatidique de Heimdallr qui annonce la fin des temps : nul ne saurait se soustraire aux arrêts des Nornes. Les dieux eux-mêmes sont soumis à leurs lois. Tout est écrit d’avance.

Comme au festin de Balthazar, tout a été compté, pesé, divisé. « Un jour, il faut mourir » : on se prend à imaginer quel trappiste austère a bien pu concevoir, avant le temps, cet univers fatidique dont l’issue, indubitable, est, au mieux, l’éternelle bataille dans le palais aux tuiles d’or dont, un jour, Surtr embrasera les voûtes, au pire les séjours glacés de la hideuse Hel, mi-noire, mi-bleue. Odinn, le maître de la sagesse et de la science ésotérique, le père des runes et de la poésie, sait qu’il périra, et de quelle façon ; Baldr a fait des rêves prémonitoires, Thôrr n’ignore pas que le venin du grand serpent de Midgardr le détruira. Urdr, la Norne qui veille auprès de la source de tout savoir où le grand arbre cosmique, Yggdrasill, plonge ses racines, domine le monde des dieux et des hommes. Dans le ciel du champ de bataille volent les valkyries fatales, messagères d’Odinn venues prendre leurs proies que guettent les corbeaux de mauvais augure; en mer, Rân a tendu ses filets où se prendront les marins feigir : voués à la mort par le sort; ici, on ne rêve pas, on est visité en rêve, à l’accusatif (mik dreymdi), et si l’on a vu le cheval funeste à robe grise, couleur de mort, on ne survivra pas. L’âme (hugr), qui est la forme interne (hamr) concédée à chaque homme par le Destin, s’est manifestée plusieurs fois à celui qu’elle habite, sous forme de fylgja, de hamingja, de spamadr ou de draumkona : dès lors, il connaît que le terme est proche. Demain, il sera tout soudain paralysé, en pleine action, par les lacs de la guerre (herfjöturr) ; un étrange sommeil, irrépressible, le clouera sur place, il aura de sinistres visions de sang sur le pain qu’il mange, ou de tête livide articulant d’obscures vaticinations. C’en est fait de lui. A chaque page des textes gnomiques, mythologiques ou héroïques des Germains fait étrangement écho le dernier vers du dialogue de Jésus et de Marie, dans la Passion de Jehan Michel : Accomplir faut les Écritures. Les affreuses filandières qui tissent sur un métier fait d’ossements, un fer de lance pour navette, les entrailles des hommes tendues par des têtes de morts, arrachent brutalement leur horrible toile. Ici finit l’histoire.

Le dieu suprême

Voilà pourquoi l’on peut disputer pour savoir quel est le dieu suprême, si c’est Odinn, le parvenu d’origine asiatique, Thôrr, bonne brute roussâtre plus prompt de la massue que de la cervelle, ou le couple sensuel Freyr-Freyja, ou cet Alfôdur énigmatique : le dieu suprême porte mille noms et cette richesse lexicale devrait nous avertir. Il s’appelle audhna, tima, lukka, skôp, happ, goefa, gifla, forlôg, orlog : sort, destin. Devant lui, les Ases, les Vanes et les Alfes s’inclinent, créations poétiques avant tout, quand bien même elles remonteraient à d’authentiques traditions guerrières, juridiques ou agraires indo-européennes, quand bien même elles auraient récupéré en passant d’absconses réminiscences chamanistes transmises par les Sames avant qu’ils n’eussent été chassés de la péninsule scandinave par les Germains. Rien n’est plus impur que la religion nordique dans l’état où nous la connaissons : en strates successives, le temps y a déposé les apports de civilisations nombreuses, à jamais enfouies dans la mémoire, et ce sont des clercs chrétiens qui ont consigné la plupart des textes dont nous disposons. Mais les gravures rupestres du Bohuslàn, les conjurations de Merseburg et l’Edda de Snorri sont d’accord sur un point : plus haut que les dieux et les mythes, plus fort que le temps et la mort à laquelle il préside, se dresse le Destin. Nulle part cette obsession n’éclate mieux que dans le complexe Edda héroïque-Vôlsunga Saga-Nibelungenlied : il ne s’y trouve pas un seul personnage important qui ne connaisse d’avance son lot, tout a été annoncé dans le détail, tout se réalisera dans le détail. Si l’on s’en tenait à une vue plate des choses, toute la religion des Germains apparaîtrait d’une absurdité énorme, écrasante. Les dieux et les hommes ? Des fourmis qui s’en vont stupidement vers un terme inexorable qu’ils connaissent parfaitement, dont ils savent par coeur le chemin d’accès et les errements. A quoi bon vivre ? Un franc nihilisme ne vaudrait-il pas mieux ?

Une fureur de vivre

Or c’est ici la merveille : tout l’univers germanique répond violemment non. Une fureur de vivre habite les êtres que nous allons découvrir. L’esprit de la lutte (vighugr) est sur eux. La lâcheté est infâme, le suicide, inconnu, le scepticisme, méprisable. Le thème aux variantes sans nombre du Bjarkamdl hante cette littérature : il faut quitter la vie, voici la voix d’Odinn, voici les valkyries qui m’appellent à mon destin, réveillez-vous, réveillez-vous, valeureux compagnons d’armes, luttons !

Pourquoi ? C’est que le Destin est sacré. Il n’est pas de plus haute valeur. Et si l’on ne peut donner sa vie pour le sacré, vaut-il la peine de vivre ? Ou, plus exactement, si la vie peut être si passionnante, n’est-ce pas parce qu’elle est ce champ clos qui nous a été donné pour y faire chanter, éclater le sacré ?

Car le Destin s’incarne, le sacré se dépose en chaque homme. Nous accédons ici à la caractéristique la plus originale, la plus étonnamment moderne du paganisme germanique : l’homme ne subit pas son sort, il n’assiste pas à son destin en spectateur intéressé mais étranger, il lui est donné de l’accepter et de l’accomplir — de le prendre en charge, à son compte.

Valeur nouménale individuelle du Destin

On a longtemps cru que les Scandinaves, dans les siècles qui précédèrent la conversion au christianisme — VIIIe et IXe siècles —, avaient atteint une sorte d’irréligion, de scepticisme ou d’indifférence qui serait allée à l’encontre de ce qui vient d’être dit d’eux. Cela tenait à une phrase qui se rencontre souvent dans les textes :Hann blôtadi ekki, hann tradi à sinn eiginn màtt ok megin (« Il ne sacrifiait pas aux dieux, il croyait en sa propre force et capacité de chance »). Il y avait là, semblait-il, une attitude fort inhabituelle au Moyen Age où l’on avait voulu voir un trait exceptionnel, digne de peuplades que les « philosophes » du XVIIIe siècle français considéraient comme les régénératrices de l’Occident. Les recherches récentes de savants suédois, Folke Strôm et Henrik Ljungberg en particulier, ont établi qu’une telle interprétation ne reposait sur rien. Et comme nous sommes ici au coeur du problème, il vaut la peine de s’y arrêter.

Les divinités du Destin