#christian apocalypticism

Text

I was raised in the People of Destiny cult (later renamed, and more well-known as, Sovereign Grace Ministries, now Sovereign Grace Churches).

The valorization of martyrdom and The End Times was so ubiquitous it was ambient noise. We stood in the church lobby theorizing about who the antichrist would be, we argued about whether Jesus would rapture us all before, after, or during the Tribulation Period where Satan would be given free reign over the earth. There was a strong Christian Zionist fixation on Israel as the final battleground and capital of the coming Messianic Age. But the one thing we were all certain of was is that we were in the End Times, that we were not of this world and couldn’t get too attached to our lives here.

We were raised to believe our sin nature made us undeserving of life, that we deserved death and eternal conscious torture.

My parents read us the Jesus Freaks books (a series by Christian Rap group DC Talk about martyrs). I spent “devotional time” reading Fox’s Book of Martyrs. We had guest speakers from Voice of the Martyrs, their pamphlets were often stocked in our church’s information center. We grew up with our dad listening to right wing talk radio and making us listen to songs about how the Godless atheists were outlawing Christianity in America, that we could all become martyrs soon.

The group’s theology was damaging & traumatic in a lot of other ways that contributed to the suicidality I have continued to struggle with for the rest of my life. For a long time I did not believe I would live past 20. There are times when the idea of giving my death meaning by using public suicide to make a political statement has appealed to me.

So now, seeing so many social media posts glorifying the suicide of a US Airman this week, I have been furious. Reading his social media posts, I recognize so much about the way I was raised in his all-or-nothing, black-or-white mindset, the valorization of death-seeking & martyrdom, and the apocalyptic fire-and-brimstone imagery of self-immolation. The moment I saw people I followed celebrating his self-immolation, I said to myself “this feels like a cult”

So when I learned he was raised in a cult too, nothing could have made more sense to me. His political orientation may have changed, but his mindset did not—it was no less extreme or cult-like.

I’ve talked about so many of the reasons this response from the broader left scares me, including how it’s laundering that airman’s antisemitic beliefs, but I cannot think of anything that would hit me in a more personal place than this specific response to this specific situation has.

When I see the images, I think: that could have been me. That scares me, and what scares me more is that so many prominent people are overwhelmingly sending the message to people like me that there is nothing else we can do that would have a more meaningful impact than killing ourselves for the cause.

I do not believe that. I will not even entertain it. And having to see his death over and over and over again, to argue against people who are treating this like an intellectual/moral exercise or a valid debate we all have to consider has been immensely triggering and fills me with a rage I rarely feel. It’s unconscionable that we are even putting self-harm on the table, and that pushing back against that is somehow controversial.

There is hope. Our lives do have meaning. There are far more effective means of fighting injustice. And the world is a better place for having you in it. Don’t fall into believing this is a way to give life purpose.

#he was raised in a different cult than me but there is significant overlap in the Community of Jesus & People of Destiny worldviews#EDIT: I originally said the Tribulations were ‘7 1/2’ years but this was me confusing the ‘a time times & half a time’ from Daniel#with the idea of a 7 year tribulation#it’s been forever and a lifetime since I lived in that world so the exact theological details can be hazy#death cult shit#extremely traumatic content#i/p#cw suicide#religious trauma#cw trauma#antisemitism#pdi international#people of destiny cult#sgm cult#sovereign grace cult#christian cult#cult survivor#death cult#evangelical apocalypticism#exvangelical

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching neurodivergent Christians who need a lot of enrichment get more and more obsessed with conspiracy theories and the apocalypse because they recently got on a kind of puritanical kick and stopped watching normal entertainment and honestly don't have much else to think about now.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got suggested this by Youtube:

youtube

It's a pretty good debunking of all the ~Nostradamus~ crank out there. Ole Michel doesn't have the profile now that he did in the 80s and 90s(when evangelicals could still delude themselves about the end of the 20th century bringing The End Times and confirming their faux-literalism), but I still enjoyed this breakdown of how useless his "Prophecies" are, and I figured I'd share it.

#Sean Munger#Video#History#Michel de Nostradame#Debunking#Woo#Crank#Conspiracism#Conservative Christianity#Apocalypticism#informative reblogs#Youtube

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#religion#religious trauma#christianity#christian fundamentalism#fundamentalism#apocalypticism#armageddon#left behind series#article#divinum-pacis

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apocalypse

Throwback to a poem I wrote for the end of '21.

The Time has come

They are coming

The Seals have been broken

The Apocalypse is here

There's nowhere to run

You can't hide from

The One Who Sees All.

You'll face your Lord's Wrath

The pits of Hell are waiting

For those who are found guilty

Of holding dear only

Money, Power and Influence.

They shall be cast out of the Sky

And face eternal suffering

Like the Angel they follow.

Michael and Azrael shall be stood

Before the Gate and none shall pass

Whom have not received the Sign.

Some will try to fight back

But they will fail

Being no match for the Warriors Of God

Their effort will be remembered by others

To no avail

#tymianox#tymianoxpoetry#poetry#poem#originalpoetry#originalpoem#poetrycommunity#aspiringpoet#mythoughtsinwords#apocalypse#apocalypticism#end of time#end of 2022#end of the world#christian bible#christianity

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey, OP. Saw your post where you said you he'd the opinion that "it is not possible to be Christian and do magic at the same time, but that has never really stopped Christians." What do you think of the role spiritism has for catholics in Latinoamerica? The church recently beatified(?) a Venezuelan doctor (Dr. Jose Gregorio Hernandez) whose first emergence was... I don't know how else to call it other than "spirity". People would pray to him to cure people, it 'worked' at some point, and the Vatican decided to uh recognize it I guess. Now he's part of the League of Soon-To-Be-Saints, but he still gets called upon by, say, Maria Lionzists in Sorte (I don't know the English word for this, but it's believers of Maria Lionza, one of the biggest spiritual religious movements in the caribbean).

My Point is that's not really a new thing for Christianity. The closer you look at Christian history, you see that it's always been this perpetual negotiation with the concept of magic. For the Catholics, it's ultimately up to the church to decide what gets incorporated and what gets condemned.

Hell, look at the early Christians. Some of the oldest Christian rituals are basically just Roman pagan rites reinterpreted via Jewish apocalypticism. I would even argue that Christianity's ability to incorporate wacky magical/charismatic practices is one of its major strengths as a religion.

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imperium Sanctus

(...T)he phrase “Grimdark” may suggest the name of some 2000s era Goth club. It’s a recent coinage for an ongoing craze in “gritty” and dark fantasy settings, epitomised and popularised by George RR Martin, becoming the default tone for a whole range of feted fantasy offerings from Joe Abercrombie’s First Law series featuring a dark, brooding protagonist who kills a lot of people — and occasionally feels bad about it — to Mark Lawrence’s Broken Empire Trilogy featuring a dark, brooding protagonist who kills a lot of people — and occasionally feels bad about it.

Like many fantasists with a bone to pick, mister Milbank doesn't actually know when or where "grimdark" was coined. Knowing fuck all has never stopped a critic (indeed, The Critic): Milbank goes on to blame everything from Breaking Bad to The Sopranos, constructing a spurious history of dark fantasy(?) that ultimately singles out author Michael Moorcock as godfather of grimdark.

While Moorcock’s gory, British sorcery is a major influence on today’s grimdark, the inception point of the trend is in fact googleable: it’s been the tagline of gory, British science-fantasy wargame Warhammer 40,000 since its 1993 second edition.

In the grim darkness of the far future, there is only war.

Already this betrays the hopepunk's antimaterialist concerns. It doesn't matter that The Walking Dead and Boardwalk Empire are nothing alike. Taking the historicist tack, it becomes even less likely that they have a connection to 40K. But morality, as an immaterial concern, is a laser beam: it vaporizes material history. Grimdark is a specter on the pages of anything that irritates gentle sensibilities.

For the sake of avoiding googleable gaffes, Alexandra Rowland, author of books named things like A Taste Of Gold And Iron, and coiner of "hopepunk", in a follow-up essay:

There’s no such thing as winning forever. Evil cannot be vanquished, only beaten back for a day or two, and then it trickles back in, like water seeping through the cracks in a dam.

Ask it of hopepunk, then: "What's the point?"

And the answer is, of course, that the fight itself is the point.

In the noble brightness of the far future, there is only (___)?

Unlike Rowland, Milbank is a nothingpunk: The Critic is a conservative Christian rag pontificating everything from trans-exclusionary rhetoric to the dismantling of higher education. Which begs us to consider how Milbank so easily co-opts shades of Rowland's language to peddle a retvrn to Tolkien, on its face the last thing a fantasy author looking to innovate would want.

The Imperium of Man, the central setting of 40K, is an arch-conservative Great Man cult worshipping the once-Emperor of Mankind. This is the gate leading to the inner sanctum where the Emperor's corpse resides. Catholic readers may have noticed similarities to portrayals of the Archangel Michael fighting the Dragon (1400~, 1498, 1860), as narrated in Revelation 12.

Revelation is the tale of darkness enveloping the world, and the noble, virtuous men who persevere despite persecution and are eventually victorious in heavenly war(!). This is not dissimilar to J.R.R. Tolkien's "fundamentally religious and Catholic work", in which ordinary men persevere against darkness enveloping a world. Rowland and Milbank both champion Tolkien as exemplary, the former in the same breath as Jesus. Yes, of Nazareth.

The Lord Of The Rings is unmistakeably about the War of the Ring. Positing Tolkien's apocalypticism as aspirational fails to rebuff the basic conceit that war is a human constant and even a force for good. If this isn't the aim of a genre purported to concern itself with kindness and "giv[ing] a fuck about the people on the other side of the world", what is?

Aesthetics. Rowland doesn't call for a narrative movement with less conflict, but one that appropriately celebrates those that fall on the right side of conflict. Even just those that deigned to imagine, of slaying the Dragon, "probably drunk in a bar somewhere, I bet it can be done, though." (The writer's original temptation: a medal for thinking the right thing.) Millions of people die in Revelation, magnitudes more than in Game of Thrones, but the virtuous go to heaven forever. The Emperor of Mankind sits on the Golden Throne, Frodo bodily assumpted into the Undying Lands, Jesus curled up into a ball and just rolled away. All manner of things shall be well.

The transition from here to open conservatism is again in aesthetics, and thus stepwise. Having established Tolkien as the only fantasy writer he respects, Milbank derides grimdark as immature wish fulfillment. If you write fantasy at all, it ought to have a clear moral message, else you are devaluing reality by infesting Real (not in the Lacanian sense) conflict with magic missiles. But he's also established that realistic fiction with no clear hero is a faux pas. He wants Breaking Good and, like, The Walking Alive.

This is no surprise: if you were around for the Disco Elysium craze, you might remember this tweet (holy shit it's still up) calling for a game that uses Disco's systems to narrate the story of "a young witch" looking for her neighbor's cat. Take another step and this is the logical conclusion of an aesthetic that prizes upright moral posture: a world where the protagonist has to do nearly nothing to be good. The little village in the Alps and the events of Disco Elysium might be unfolding in the same world. But our little German girl with no problems doesn't have to participate in anything as unsightly as a Pinkerton massacre. Milbank disdains C.S. Lewis without knowing that what he wants is the end of Narnia, irrespective of the events that preceded it: the crowning of the king, who once was good. The Emperor protects!

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stephen Shoemaker has talked at length about the eschatological nature of early Islam in other books and articles; he makes some very interesting points in The Apocalypse of Empire (which is not just about Islam, although it discusses Islam at length in two chapters), synthesizing some points made by other scholars.

Scholarly trend to view Islam as a movement that was from the beginning pragmatic, not apocalyptic. Other scholars try to portray Muhammad as basically a national unifier/Arab empire-builder, with religion as a tool secondary to this aim. This seems to amount to not taking early Islam as it portrays itself very seriously, and indeed in some cases seems to be almost an apologetic project to try to help make early Islam more relevant to the present day.

Snouck Hurgronje(sp?) argued that early Muslims saw Muhammad's appearance itself as a sign the end of the world was at hand, and that Muhammad would not die before its arrival. He and other scholars after him saw other elements of his message as more or less accessories to his concern with the impending end of the world.

Projects of empire-building and apocalypticism are not necessarily opposed! The rest of this book furnishes examples from Byzantium, Rome, Zoroastrianism. For a contemporary example, we might look at ISIS. It was relatively common in the ancient near east to think the eschaton would be realized through imperial triumph, and that the end of history was imminent. Indeed, Muhammad's religious beliefs probably played a significant role in the dynamism and success of his nascent polity.

Later Islamic tradition like the biographies deemphasized the urgent apocalypticism (again, not unlike Christianity!). But the Quran is rife with warnings of impending judgement and destruction ("the Hour"), and incorporates Christian apocalyptic material like the parable of the rich fool from Luke. Shoemaker furnishes lots of quotes like "The matter of the Hour is as a twinkling of the eye, or nearer," and "The Lord's judgement is about to fall," etc. Astronomical events will predict the Hour's arrival; doubters will soon be proved wrong, etc.

Perspectives from the New Testament help us understand why different passages portray the urgency of the Hour differently; the historical Jesus probably preached an imminent apocalypse, but the Gospels were compiled later, so they can be more ambivalent. Likewise later Muslims, when compiling the Quran, would have to deal with the fact that the "urgent" end of the world hadn't arrived yet; though the strong eschatological perspective persisted (as it did in Christianity, too), there was an effort to try to moderate some of these embarrassing passages.

Some early hadith and other early traditions corroborate the impending eschaton, emphasizing the link between his appearance and the end of the world. "According to another tradition, Muhammad offered his followers a promise (reminiscent of Matt. 16:28, 24:34) that the Hour would arrive before some of his initial followers died. In yet another tradition, Muhammad responds to questions about the Hour’s timing by pointing to the youngest man in the crowd and declaring that 'if this young man lives, the Hour will arrive before he reaches old age.'"

Donner argues the conquests were an effort to establish an interconfessional "community of the Believers" that included Jews and Christians, requiring only belief in God and the last day. According to him, Muhammad and his earliest followers didn't even think of themselves as a separate religion; rather, their earliest community was a loose confederation of Abrahamic monotheists who shared Muhammad's apocalyptic aoutlook, and who were trying to establish a righteous kingdom in preparation for the end. Cf. the Constitution of Medina, which seems to be a very early source. It has a dramatic discontinuity with the ethnic and religious boundaries established in later Islam. Traditionally held to be a brief experiment that ended with Muhammed expelling the Jews from Medina, Donner argues that in fact Muhammad's community remained confessionally diverse for decades, including Jews and Christians into the Umayyad period. Indeed, a lot of their early successes may have been aided by their nonsectarian outlook.

Only under Abd al-Malik(!) does Islam begin to consolidate, and a new Arab ethnic identity crystallizes that distinguishes Muslims from outsiders they ruled.

In variant readings of the Quran we can glimpse a view not unlike that of the early Christians, where the Kingdom of God had its inception in Jesus's works; here, the conquests of the early followers of Muhammad are part of an the initiation of the end times. Muhammad is the "seal of the prophets" in this reading because the world is about to end.

So the picture that emerges from all this is that Muhammad was an apocalyptic preacher and reformer, very much like Jesus, who wasn't aiming to found a new religion necessarily. But he preached that the world was ending, and as part of his preaching on this subject he led the creation and rapid expansion of a new polity meant to unite the community of believers. Only once he died, and the world failed to end, and his followers had to consolidate their gains and transform them into an actual, durable state did a coherent scripture (the Quran) and a coherent religious identity (Islam) emerge, both strongly affected by the new social, cultural, and political contexts his followers found themselves in. The turning point seems to be the reign of Abd al-Malik, around fifty years after the death of Muhammad, when the oral traditions of the original community of believers are approaching their expiry date, and a new generation (and new converts) need a worldview and a political system that is relevant to their present circumstances. This is extremely comparable to the transition from early Jesus-traditions to the Gospels finally being written down in the second century, when the last people who knew Jesus directly, or who knew the Apostles directly, were dying, and the community had to transition to a form that could survive indefinitely, or else be forgotten.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

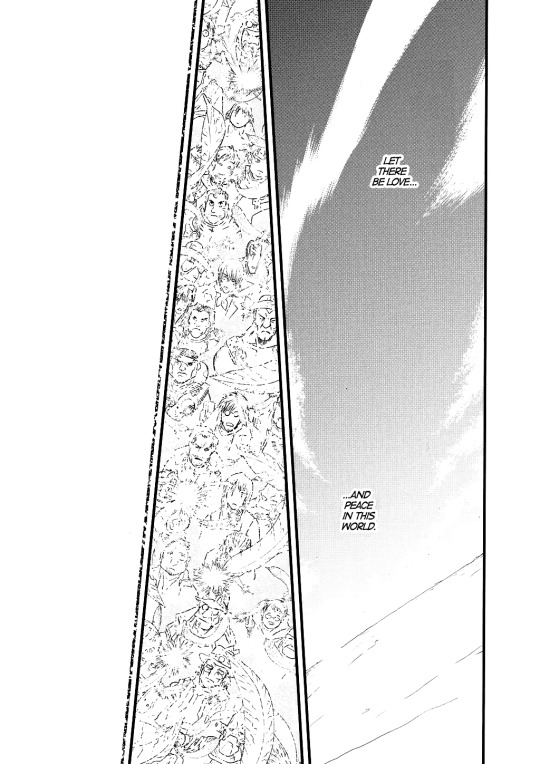

Trigun Bookclub: Some Very Long-Winded Final Thoughts (for now)

So what's my takeaway after all this discussion about the allusions to religious concepts and narratives in Trigun? What conclusions does the story draw about faith? And are there any theological ramifications to its message?

From my perspective, the belief system Trigun promotes is a broadly defined humanism that isn't bound by any religious tradition. Declarations of faith in this story are more often directed at individual people or humanity as a whole than toward a god or metaphysical concept. Trigun says that the purest and most fundamental faith is our belief in one another and in our collective capacity for good, and the specifics of any one person's faith are worth pursuing so long as it keeps them in the business of living and engaging compassionately with other sentient beings.

In Trigun's larger thesis on faith, there's also a notable emphasis on the drive for continued life and hope for a future that can be built in the present world as opposed to glorifying death in the service of grandiose ideals, especially if those ideals center on seeing the world as irredeemable and in need of destruction. And it's through this message of continued striving in the here and now that I think Trigun brings up its own point of contention against a particular theological perspective. What we have in Trigun is a firm rejection of apocalypticism.

According to the Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements, apocalypticism is the "belief in the impending or possible destruction of the world itself or physical global catastrophe, and/or the destruction or radical transformation of the existing social, political, or religious order of human society—often referred to as the apocalypse." In Christianity, this perspective is clearly seen in futurist interpretations of the book of Revelation (the Greek root word for apocalypse - apokalypsis, means revelation or unveiling). This eschatological approach treats the text as a prophetic outline of the end of the world in which God brings judgment through a series of cataclysms and then secures an everlasting paradise for the faithful.

Revelation 21:1-4 (NRSV):

(1) Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. (2) And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. (3) And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, "See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them: they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; (4) he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away."

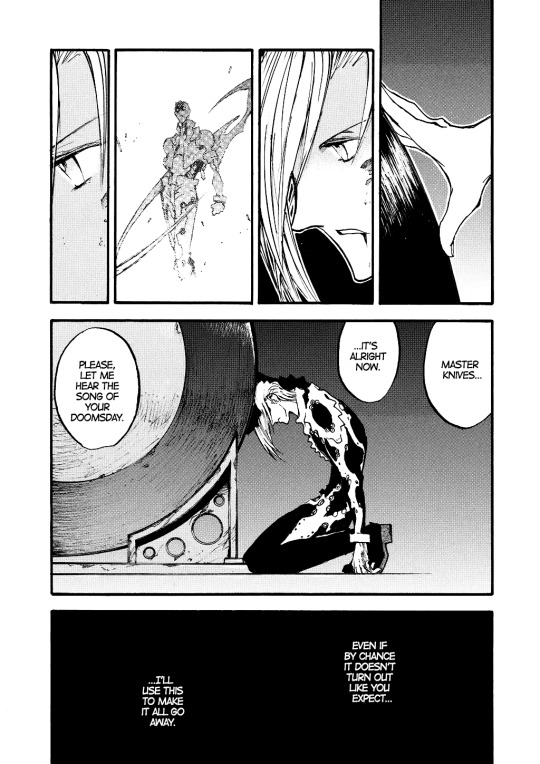

As we all know, Knives loves to position himself as a bringer of divine judgment in the same vein as the Abrahamic God.

To Knives, humans are a source of evil that have to be purged from his world; salvation for his chosen people (plants - the higher beings) can only come through mass death. The realization of Knives' apocalypse is doomsday for humankind. No surprise then that in his followers (some of whom revere him like a deity), we see the sentiments of a doomsday cult. To Legato, service to the supreme being is his sole purpose in life; if Knives commands him to die, then he'll die gladly. For Elendira, the most glorious service to the supreme being is to facilitate his vision for the end of the world, and she wants nothing more than to see it happen. And in Chapel, we see the cruelty and cynicism promoted by the apocalyptic mindset: If the end is inevitable, then all efforts to protect what we have in this world are futile, so what value is there in choosing to be merciful?

The immense harm dealt by real religious groups that hold similar beliefs to these is difficult to overstate. So long as any atrocity in the temporal world can be justified when committed in deference to what are taught to be higher spiritual principles, there are no ethical boundaries these groups won't transgress. Japanese society in recent history has, in fact, had significant experiences with violent apocalyptic fanaticism. The most well-known of these occurred on March 20, 1995, in which the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo carried out its deadly sarin gas attack in the Tokyo Metro subway system. An act of religious terrorism left many dead and thousands injured, all because some people were convinced the world was ending, and it was to their benefit and everyone else's benefit if they could make it end faster.

The doctrine of Aum Shinrikyo was a mishmash of Hindu, Buddhist, and Christian concepts, and Christian eschatological views on Armageddon were especially influential to cult leader Shoko Asahara's prophecies in the time leading up to the attack. Common threads in books of the Christian Bible with apocalyptic elements include emphasis on the corrupting nature of the present world and promises of eternal unity with God after a final war in which Christ emerges victorious against all evil. These ideas are also disconcertingly influential in mainstream American Evangelical Protestant Christianity. Even in the most nonviolent Christians who would never dream of associating with extremists, it's not hard to find an underlying cynicism and detachment with regard to living life in the present. There's the notion that the world is fundamentally broken and sinful, and believers should look forward to God's destruction and remaking of it, because perfect happiness can only come in the thereafter.

1 John 2:15-17 (NRSV):

(15) Do not love the world or the things in the world. The love of the Father is not in those who love the world, (16) for all that is in the world—the desire of the flesh, the desire of the eyes, the pride in riches—comes not from the Father but from the world. (17) And the world and its desire are passing away, but those who do the will of God abide forever.

From such a perspective, hope is primarily oriented toward some indefinite point in the future that will come to pass via the eradication of every imperfection that marks the present. What happens in the story of Trigun, however, is an overturning of the apocalyptic narrative. The climax of Trigun Maximum invokes the fantastical imagery of Revelation, creating the impression of a stage set for the definitive final battle between the embodiments of good and evil, but then the story pushes back against the narrative conventions of apocalypticism. There is no end of days, no destruction and re-creation of the world, because it was averted by radical human hope for compassionate understanding in the here and now. And there is no ultimate triumph of Good over Evil in which Satan is cast into the lake of fire. In fact, there may not even be a "Satan" in this story at all.

When Knives collects his sisters into an amalgamated body, his form and theirs take on a draconic appearance, bringing to mind the red dragon of Revelation (that is, Satan). In Knives' own mind, however, he's God pouring out his divine wrath on the humans who've sinned against him, and there are angelic elements to his design as well to reflect this. Ultimately, his form doesn't hold. Vash and his human allies manage a breakthrough in communicating with the collective body of dependent plants, and when Knives is cast to the earth (in another departure from Revelation, this doesn't occur as the outcome of heavenly forces battling against him), he faces Vash one last time as just a man - Vash's brother who's lashing out because he never processed his extreme childhood trauma. Because maybe in the end these forces of absolute good and absolute evil don't exist; maybe our willingness to imagine God and the Devil was always the product of our own messy, conflicted humanity in all its potential for good and evil.

The resolution, then, happens not through one brother killing the other, but through connection and understanding, a little push toward a kinder existence for everyone. Knives ends up having to place his trust in the very humans he hated in order to save his brother's life, and his faith is rewarded. For Vash and the rest of humanity, life goes on; it goes on in an imperfect present, but it's a present where there's plenty of joy to be found nonetheless. So the story closes out under a bright blue sky with the assurance that the song of humanity still sang. There's no looming threat of doomsday, just a path forward toward more life.

#trigunbookclub#trigun#trigun maximum#ow my brain I need a break from writing#trigun meta#Guns&God meta#religion mention#christianity mention#cults cw#terrorism cw#long post

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey!

I was raised aetheist, and I never really realised how badly Christianity could screw people up. There were some people in my extended family who were religious, but it was always just this vague distant thing that existed on the periphary. The only times I entered churches were in a touristy way, and only then because my mum dragged me into them - I've always hated churches, they have bad vibes.

Then I met my best friend who was raised in a religious family, and they described a lot of the strange, disturbing rituals they would perform in church. Around the same time, I began watching a content creator who was raised in a religious family and was going through the process of reconciling their religious upbringing with their homosexuality.

Since then, I've been really fascinated by how this religion can screw people up and make people doubt their entire being. I think a lot about how on earth this one religion - or cult - from a city thousands of years ago became so persistent and all encompassing.

I was wondering, what do you know about the real-world history of the Christian religion and Jesus? One can assume that Jesus was a real person, but what are the details? Was he a cult leader? A rebel? Both? How did he make people believe he was a prohpet? Why did he make people believe he was a prophet? I'm fascinated by the real historical events that occurred to create such a long-lived ripple effect, but I'm cautious of researching "religious history" on my own because I don't know how to avoid the many dangerous people one would be likely to come across in that feild. Do you have any knowledge to share?

-🟪

My favorite biblical historian is Dr. Bart Ehrman (link to his website). He’s a former Christian, current agnostic which I think gives him a balanced view of biblical history. He talks about what it was like to believe in the Christian story, what it was like to figure out what is real and what isn’t, and what actual biblical scholarship should look like. His books helped me disentangle the complicated stories around Jesus and develop my own sense of scholarship.

Most historians believe that Jesus was a real person who existed around the same time and place as was claimed in the Bible. We have no eye witness testimony about anything Jesus said or did. All we have are copies of copies of legends that people wrote about him decades after his death. We have no real way of knowing what Jesus thought about himself or what he claimed to be.

That being said, we can try to understand the traditions of the stories told about Jesus. I’ve heard a lot of fundamentalists claim to be going back to the “early Christian church” but there were so, so many traditions that sprang up around the story of Jesus all believing different theologies. For example, early Christian mysticism is a weird, wild rabbit hole to go down if you’re ever curious.

We can try to understand the man that Jesus was by looking at the stories told about him. These stories were based in apocalypticism under Roman rule: the belief that the end would come, but hey at least it would free people from Roman tyranny. Jesus was an apocalyptic preacher whose death caused shockwaves of grief among his followers. I do believe that he made promises about the coming kingdom and when those promises were suddenly impossible after he was killed by his government, his followers found a way to make those promises relevant again in their own minds.

I find this stuff interesting, but I really wish that this specific history didn’t affect people’s lives in the modern world. I wish it were just a weird history niche instead of a direct threat to people’s wellbeing. Being hesitant to research biblical history makes sense. There’s a lot of nonsense out there to dig through and it can be exhausting. Take care of yourself first. Biblical history is not as important as your wellbeing. But if you do enjoy researching, have at it! Find people that you respect, hold on to ideas loosely so you critically evaluate them, and be ready to take a break if you burn out.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

That's probably because Christianity started out as a cult.

During the 1st century CE, Judaism was going through a bit of a sectarian crisis. The "Temple Cult", the main religious institution centered around the temple in Jerusalem, was getting weaker. Many groups downplayed its importance or rejected it outright, especially groups outside of Judea.

A lot of these sects would be what we would call cults. Small, high control groups that isolated themselves from wider society.

One of the most popular movements among these splinter groups was called Apocalypticism. The idea that the reason the world was full of suffering is because it was ruled by evil demonic forces. But someday soon God would bring forth a savior, a Messiah, to defeat evil and establish a godly kingdom.

Another phenomena that existed at the time, this one as part of the Hellenistic world, is called Mystery Cults. The mystery cults were cults devoted to a single divine savior figure. They would perform baptisms to symbolize rebirth with their saviors, celebrate a passion in which the savior deity defeats death and evil, and eat special meals representing their covenant with the savior, often symbolically eating the savior's flesh. These mystery cults often combined elements of Hellenistic religion and another culture. Like the cult of the Persian divinity Mithras, or the Egyptian gods Isis and Osiris, all three had their own cults.

Christiniaty was essentially in the right place and time to combine elements of both Hellenistic mystery cults and Jewish apocalyptic sects to create a new religion. And many of the cultish elements of its dual origins (changing your identity for the savior, believing in the coming end of days, isolating yourself from non-believers) stayed with it for the last 2000 years.

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

my white whale is this class on christian apocalypticism that was only taught once & the professor didnt respond to my inquiry regarding the reading list probably because it was years ago. dream class.

#op#academie#when i have more time i will read the books that are mentioned online i think#im planning to read violence & the sacred in the summer i think ill add a book from this list to that

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMM9vsekf/

she was crying like this because of the eclipse. Why do so many Christians have some form of psychological breakdowns whenever shit like this happens?

This is basically what happens when your religion is all about that imminent apocalypticism. The leaders/influencers are always interpreting everything as a sign of the apocalypse. Can't really expect anyone to be mentally well under these conditions.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

How would one perhaps cast a glamourbomb?

Note: This article describes some stuff people did in the past. It’s not safe or wise to do that kind of thing nowadays, if it ever truly was. I don’t recommend engaging in these activities, but wanted to answer this anyways. The word itself made me nostalgic, but conflicted? Yeah.

Glamourbombs, at least as I know the term, aren’t spells in the traditional sense. They are (were, more like) magical performance pieces. They touch the “mundane” world with some sort of occult interjection. This was (perhaps thankfully) most common in places where the veil between “mundane” and “weird” was already thin: libraries, universities after midnight, anime conventions, places like that. While I don’t doubt people still do this today, the trend was at its peak around the turn of the century.

At the time, I was in middle school. As the Millennium (holy f**king s**t! its Y2K!) approached, the apocalypticism wasn’t just limited to the Christian kids. Those of us who weren’t Christian or just came from more secular families still saw things like hysteria about Y2K glitches and especially climate change. A lot of that was pretty scary to us, especially considering some of our more fundamentalist-minded neighbors were saying the world was going to end and “Jesus was coming back.”

It wasn’t so much that we believed them. We just knew, even as kids, that the scientists weren’t lying about the climate data. We also knew that people were acting really irrationally, whatever their reasons. This fit in well with the notion that some big change was coming. Maybe it wasn’t the Christian apocalypse, but could it be something? Plenty of adults seemed to think so, too.

Online, and in our own (burgeoning) occult spaces, we had our own spin on things. Allegedly, by glamourbombing, we were helping, in some small way, to enchant this increasingly hostile mundane world. Because, as teens and tweens growing up on White Wolf, Captain Planet and Square Enix, we clearly knew what was best for reality!

We had every right to (at least try to) impose it on the rest of the world at every chance. Right? Right?

We’d all read at least two books on witchcraft from Barnes and Noble, too.

In some scenarios of glamourbombing, the point was just to make people going about their day pause for a few seconds, think “Hmm? Cool!” and go on about their lives, hopefully in a better mood. These were usually simple things like flyers seeking a “LOST UNICORN,” a notice that you’re entering a “PIXIE-FREE ZONE,” silly things like that. You still see stuff like this today and (if it’s well-designed) it makes people smile and nothing more.

Other glamourbombs had more complexity. They (sometimes) included a bit of magical technique - an active hypersigil, for example.

When pen drives grew in popularity, they became common tools for glamourbombing, with people filling the drives with “magical” material and leaving them (usually conspicuously) somewhere, like a library.

These hypersigils might take the form of experimental music MP3s, animated loops, even actual .EXE files (supposedly). I don’t know whether anyone was bold or foolish enough to click on something like that, of course.

I was barely in my teens, and definitely still sorting things out when it came both to my personal beliefs and perspective on wider community issues like this. Even then, though, I knew not to click any weird .EXE files.

The larger problem, in case you couldn’t tell?

A lot of this straight-up ignores issues like bystander consent from a magical perspective and, y’know, the problems that can arise from leaving weird/unexpected things in public places.

Also? In case you’re not keeping track, I’m talking about the 2000s here. Early 2000s. As in directly after 9/11. Not exactly a wonderful time to be running around acting weird in public and dumping strange packages. Not a safe or wise thing to be doing. Some people got a tag on that early on and quit such shenanigans.

In the summer of 2003, I attended a summer program for “gifted” 🙄 kids where I took the course focused on Greek mythology. The motley pack of metaphysically-inclined nerds I met there thought glamourbombing was tragically cool, of course. We had all kinds of ideas about “Lost Pegasus” flyers and other Greek mythology-themed things. Thankfully nothing that would’ve been too harmful. We ended up being too shy and busy with schoolwork to actually do any of it.

Sadly, later on, there were some attempts by groups (some of which I’d call cult-like) to recruit using this kind of thing. I won’t name anything that’d put me on anyone’s radar (hopefully), but I remember reading about some of it.

One particularly unpleasant and notorious use of this technique occurred on the west coast in the late 2000s when a cult set up an “art installation” in public featuring a live rat in a maze and some other random detritus. The rat didn’t freeze to death despite cold temperatures, thankfully.

Incidents like that (which was, of course, reported as a bomb scare) probably helped to put a stop to the glamourbombing trend. After all, if you’re (supposedly) after some kind of mind-liberating mass reenchantment of reality, well, nothing could be worse than the whole bomb squad showing up, right?

As the digital age crept on, I think people started to reevaluate attention’s role as a commodity. It’s really easy to get attention if you want it, as things like the “rat in a maze” exhibit (which made the papers) show.

You can’t control what kind of attention you’ll get, though, and you can’t say for certain that what you’re doing won’t have unintended consequences for other people. With that in mind, something like glamourbombing doesn’t seem very responsible, especially right now.

I guess the concept isn’t irredeemable. As recently as 2018, I was posting on Facebook looking for someone to help me slay the green dragon that sometimes lands in the field near the Taco Bell by the highway.

Little pranks and jokes like that can brighten everyone’s mood sometimes. There’s certain contexts, though (my Facebook feed, for example) where it might be appropriate, and others where it wouldn’t.

And the full-on concept of a glamourbomb, designed to “spread magic in the mundane'' with an active sigil of some sort, etc? Hard pass. Doesn’t seem ethical to me nowadays.

And, of course, it’s generally a bad idea to do anything that might be mistaken for a bomb threat.

#witchcraft#magic#occult#chaos magic#witch#witchblr#sigil#hypersigil#glamourbomb#early 2000s#eliza.txt#new occult#postmodern#millennium#tw animal neglect#tw bomb

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

y’know it’s a little frightening how normalized apocalyptic thinking is. it is believed by almost everyone that there is going to be An End To What Is Now!!! the end is nigh!!!

whether that be the end of capitalism, the end of the world due to climate change, the end of peace as the world enters a period of even more extreme war than we have now, the rapture, so on.

apocalypticism is seen as a default belief/framework upon which so much policy, belief, behavior, etc relies.

marxism is fundamentally apocalyptic. fundamentally!!! the end (of capitalism) is coming!!

cyberpunk/solarpunk/hopepunk/whateverpunk are all absolutely apocalyptic. there will be an end!!! then something else will come. (HOW IS THIS NOT A REBRANDING OF HEAVEN/HELL ON EARTH)

it goes without saying that US-style evangelical christianity (and its exports) is apocalyptic (to the point of attempting to literally immanentize the eschaton!!! red cows in jerusalem!!!!).

judaism is apocalyptic. islam is apocalyptic. buddhism has its own apocalyptic versions, though i’m less versed on buddhist eschatology.

literally any belief that says “this current way of doing things is TEMPORARY, and then BIG CHANGE will come and everything will be DIFFERENT” is literally apocalyptic.

what the fuck????

what happened to the foundational belief that things will continue on? it was not always the case that people believed the world wouldn’t pretty much always look like this over here. i’m absolutely disinterested in arguments about “realism” or other protestantism-in-a-mask ideas that do nothing to address the fact that everyone seems to believe the world is ending.

we don’t have to believe that, you know. we can choose to not believe the world is ending. it’s not blindness, it’s not “refusing to admit the truth.” there is a difference between apocalyptic thinking and objective reality.

8 notes

·

View notes