#assfish

Text

If you had any important plans, do not click this.

#new hyperfixation#ASSFISH#turtles all the way down#neurodiversity#adhd#neurodivergence#adhd memes#adhd brain#adhd mood#fun distractions#oh gods it's been hours now

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sorry about your boyfriend. I heard the scientists that found him named him assfish. To be fair they’re right he is in the genus acanthonus.

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

bony eared assfish

0 notes

Note

Acanthonus armatus

fish 135 - bony-eared assfish/a. armatus

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

#clearing out phone#clearing out camera roll#scientist#bony eared assfish#fish memes#fish#screenshotted memes#youtube screenshots#not mine

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily fish fact #269

Bony-eared assfish!

These fish live in very deep in the ocean and therefore have a soft, flabby body! The bony-eared part of their name comes from the spines they have on their gills, and the assfish part comes from its scientific name Acanthonus armatus! See, Acanthos is Ancient Greek for "prickly" and onus can mean "hake" or "donkey"... hence "ass".

#fish#fishfact#fish facts#fishblr#biology#marine biology#zoology#deep sea fish#deep sea life#deep sea creatures#deep sea#marine life#marine animals#sea life#sea creatures#bony eared assfish#bony-eared assfish

314 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Smartest and Dumbest Fish

Nothing to see here, just a marine biology warm up.

Manta Ray intelligence is simply astounding.

The Bony Eared Assfish has got to be the most unfortunate fish in the entire world.

#manta ray#bony eared assfish#meme#shitpost#marine biology#my art#nazrigart#fish#ocean life#sea life#marine

392 notes

·

View notes

Text

" ...... Why would you ever wish to cut back upon the fried crickets?"

#Glory and Gore || IC#The rumor mill || Dash Commentary#Bony eared Assfish || Crack#(( for dubious canonosity-#(( but meanwhile miri's just sitting here Confused#(( what do you mean by this. why.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rise of the Bucket Queen

On the last voyage I did, back in 2017, we were trawling in the tropics, and we were trying to hit four shallow water sites a day. We would get extraordinarily large catches, and processing those was a correspondingly extraordinarily intense task.

Once the trawl comes up and is emptied into the mega-bins on deck, the contents of those mega-bins are loaded into the gigantic sorting tray in the sheltered science area.

In a chaotic blur of motion, all the scientists involved in sorting swoop down upon the sorting tray, and it is fucking on.

Because those catches were so large, there wasn't enough room in our lab to sort the material even roughly. And, due to berth allocations, I was the only person on that shift sorting the mobile invertebrates (anything without a spine that can move), at least for the first two weeks (we had a minor staff changeover at that point, and I got my beautiful assistant Frank, who was a total legend).

Everyone pitched in where they could, but my own task could turn into a bottleneck.

The best thing to do was to have a row of 20L buckets, filled partway with seawater, and to do a rough sort in the sheltered science out on the back deck. The fish guys and any other scientists who weren't needed on some other task would pass me critters as they found them, or just set aside a small pile of invertebrates in pails that I would come around and collect, and I'd sort those into the buckets.

When a bucket was full, I'd carry it into the lab, and bring out a new bucket. We learned valuable lessons along the way (or I sure as hell did). Here are some:

The Law of Leaky Crinoids.

I love my feather stars, they are beautiful and fascinating animals, and they're my taxonomic specialty. However: some of them do have weird pigment, and when they're stressed, they leak dye into the surrounding water, which means that the water in the bucket is red, purple, yellow, or even a very dark opaque purple. Other critters in the same bucket can be stained by that pigment, which means we can't get live colour notes. Plus: it fouls the water.

Everyone figured out pretty quickly which crinoids bore Perilous Pigments, and those all went into the same bucket, labelled "leaky crinoids."

The Law of Sea Cucumber Guts.

Sea cucumbers ("cukes", "holos" aka holothurians) are also fascinating animals. They're in the phylum Echinodermata, the same phylum as sea urchins (echinoids), starfish (asteroids - yes, really), brittle stars (ophiuroids) and my beloved feather stars (crinoids! bless.). Unlike those animals, sea cucumbers tend to be soft bodied and squishy (that's a technical term).

While all those animals exhibit some degree of regeneration (re-growing lost arms, etc.), the cukes take it to extremes: when stressed, many species literally eviscerate themselves. They break in half and eject their guts, apparently a very effective strategy for distracting predators! It doesn't work on marine biologists, though. It just fouls the water in the bucket. So if we see a cuke and think "oh no, that's one of the species that sheds its innards", they get put in a special quarantine bucket.

The Perils of the Pearlfish.

As a bonus, some of these delightful mush-burgers host an unusual and genuinely bizarre houseguest: the pearlfish. Also known informally as "assfish", the pearlfish lives its life in the rectum of the sea cucumber, only emerging at night to forage, and then returning through the anus.

You can read that paragraph again if you're having trouble with that. And on this last voyage, in 2017, one of the fish guys (ichthyologists) was interested in these parasite-host relationships, and asked me to retrieve any escaping assfish from the bucket. Since the most common host species is one of those self-gutting species, the poor little assfish is safely snoozing in its comfortable tubular home when the cuke breaks in half and is now shocked and horrified to find itself in a bucket.

Now, a fish that swims in and out of an anus on a regular basis is going to be rather well lubricated. They basically look like a black sperm (typically about the length of my hand, sometimes smaller), and a whip-like tail that propels them around the bucket with great speed.

This meant that I could be seen playing the weirdest fishing game imaginable, scooping my heavily-gloved hands into a 20L bucket full of seawater and vivisected sea cucumber guts trying to catch an oversized greased sperm.

This looked exactly as ridiculous as it sounds.

The Law of Cuke Snot.

Still on the holos, some of these increasingly troublesome animals have a peculiar defense mechanism: they produce snot. I'm not talking about the kind of snot you honk into your hanky when you're in the last stretch of a nasty cold. This stuff is like mucousy glue. It sets. Peeling it off every other specimen in the bucket is a time. And yes, this definitely fouls the water.

Snotty cucumbers also end up being quarantined in their own bucket.

One crab, two crab, BIG CRAB, small crab.

I loved that the fish guys were doing such an excellent job of helping sort out the invertebrates that got mixed in with the fish catch, but now and again I would have to call out politely, "HELLO PLEASE DO NOT THROW THE SMALL CRABS INTO THE SAME BUCKET AS THE BIG SWIMMER CRAB," because I looked into the bucket with the swimmer crab to see a bunch of drifting legs and chelae (crab claws), and the swimmer crab himself holding half a small crab in its own gigantic chelae and happily pulling off small pieces of meat with its mouthparts.

If you want a very fat, happy swimmer crab, that's fine, but if what you want is an accurate assessment of the crustacean diversity and abundance, it's sub-optimal.

Those are some of my favourite lessons and the ones I remember best, and we mostly got very large catches. We had one titanic catch which had tonnes of sponge all over the back deck (literally tonnes, I'm not joking, our Sponge Sorceress had to weigh them).

On this voyage, we will mostly be sampling much deeper sites overall, which - as I said in my previous post - means we will probably get more downtime (due to how long it takes to winch the trawl down and winch it back up again), and does mean we tend to get smaller catches. The truly mammoth samples come from areas where there is plenty of sunlight still able to reach the bottom. Corals need sunlight. Algae needs sunlight (we don't usually get much algae).

Odds are good that I won't need the same array of buckets that I had last time, but there is at least one pretty shallow site, and I would rather be over-prepared than under-prepared.

As such: I am once again leaning into my role as Bucket Queen.

BEHOLD.

It could be overkill, for sure. Still, if it's a small catch, we can use the labelled buckets for the rough sorting regardless. I'll just keep them in the dirty wet lab, in that case, and we'll bring the invertebrate catch into the lab using nelly bins and sort it there, out of the heat.

As for the lab itself: yes, it is called the Dirty Wet Lab; the next lab is the Clean Wet Lab; and the one after that is the Clean Dry Lab. Each is used for a different set of tasks. My work is entirely in the Dirty Wet Lab, which does tend to get quite humid.

This picture shows the space where I will probably be doing most of my work. That mesh rack suspended from the ceiling is designed to keep power boards and cables dry and out of the way. One of the WA Museum scientists brought those clipping hooks that we're using to hang up gloves above our stations, and I swear to fucking god, that is genius.

I found a brace that I could hang my hard hat from, and as you can see I've also flipped my high viz vest and long-sleeved jacket over it, high enough that it won't fall off, low enough that I can grab it easily (that also goes for the really thick gloves).

Throughout the lab, that rack also has boxes of nitrile gloves facing downwards, so you can just reach up and grab one at a time. We're also considering putting the rolls of barcodes up there, with one end poking out, so that we can just grab another barcode like we're taking a number at the supermarket deli.

The other reason it's good to put things up there is that, well, boats move. Yesterday, as we were putting the finishing touches on the lab, the vessel came about into a wave (I presume), and we all looked up to see two large nelly bins of equipment sliding down the lab.

(they didn't go far, I promise, and they were pushed back and then secured in short order.)

Brief note here, in case anyone is unaware: research vessels of this size are generally 24 hour vessels. There are no days off at sea, because these ships are incredibly expensive to run. They require a significant complement of crew, and to get the most bang for the science buck (and look: the science buck is always, always limited), all the scientists have to be ready to go.

Shifts for most scientists run 2 til 2. I'm on the 2am to 2pm shift. We've had a significant transit period, we've done a deep camera tow, and we should be putting out our first trawl later today. The shifts have obviously been very slow as we all try to sort out our sleep patterns and set up the labs, but when we get stuck into it, it's going to be intense four weeks of 12 hour shifts, with no days off.

But it's an adventure - it's stimulating, challenging, and interesting. When you're covered in itchy fish secretions, achey from being on your feet all day, muscles screaming fatigue as you manage handover to your opposite number on the next shift, that's the knowledge that gets you through: the knowledge of the adventure, the excitement of discovery, all the wonderful questions and hypotheses that pop into your mind as you sort through the material, and the support and gestalt enthusiasm of your colleagues.

That's what gets you through.

Well, that, and the hot shower you get to have when you get back to your cabin.

#RVInvestigator#Gascoyne2022#marine biology#laboratory setup#biodiversity survey#sea cucumber snot#the assfish is the gift that keeps on giving#some animals leak#big crabs eat small crabs

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

playing around with the barbie poster ai ft. various animals

#sea creatures#animals#barbie#shrimp#nudibranch#bony eared assfish#birds#thresher shark#caterpillar#south philippine dwarf kingfisher

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

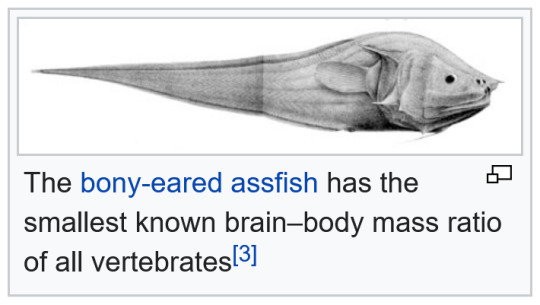

The bony-eared assfish may have the smallest brain-to-body weight ratio of all vertebrates.

Like many other creatures that dwell in the depths of the sea, assfish are soft and flabby with a light skeleton.

Come on, fish naming scientists, what did this little thing ever do to you?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

dudelin

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

found my spirit animal btw

#bony-eared assfish#fish#dann why they named shit like this#funny named fish lmao#shitpost#hhhduehdheudujedd#just like me fr#my#spirit animal

10 notes

·

View notes