#asian american literature

Text

#short stories#short story#hungry daughters of starving mothers#alyssa wong#21st century literature#english language literature#american literature#asian american literature#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls#ask to tag#tw food#tw gross food#tw eating

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

to the guanacos at the syracuse zoo, chen chen (from “when i grow up, i want to be a list of further possibilities”)

#chen chen#love poems#classic literature#literature#poets on tumblr#poems and words#dark academia quotes#dark academia#asian literature#asian american literature#from the shelf#bookblr#writeblr#prose#light academia#quotes#lit#light academia quotes#love poem

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am writing this because they told me to never start a sentence with because. But I wasn't trying to make a sentence--I was trying to break free. Because freedom, I am told, is nothing but the distance between the hunter and its prey.

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous

#Ocean Vuong#because#freedom#Vietnamese literature#Asian American literature#LGBTQ author#LGBTQ literature#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Never understood the absolute depth that can be meant by the phrase 'quietly devastating' til now. Forgive me as I quickly internalise the delicious, beautiful self-removal of skin and flesh that is reading Ocean Vuong's 'On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous'

#on earth we're briefly gorgeous#ocean vuong#asian american literature#american literature#english student

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait study of Maxine Hong Kingston (from March this year, I think?)

#portrait#digital painting#study#asian american#asian american literature#writer#maxine hong kingston#art#chuanmingong

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

reading: the fortunes of jaded women by carolyn huynh

#bookblr#Asian American literature#Vietnamese American literature#book of the month#tbrbooks#book aesthetic#desk setup#motivation#bipoc writers#studyblr

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gender's Role in M. Butterfly

Gender is a social construct, a malleable idea that is influenced by society. Carolyn M. Mazure from Yale School of Medicine states gender as “self-representation influenced by social, cultural, and personal experience.”[1] Many people want to insist there is only the binary of male and female, man and woman, masculine and feminine. However, gender is more nuanced than a monolithic binary. A person’s gender is a personal matter based on how they perceive themselves: man, woman, nonbinary, genderqueer, gender fluid, agender, or transgender. Regardless of how a person identifies, the world can perceive that person differently, as is the case for Song Liling in David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly.

For those of you who have never read M. Butterfly, it is a play about Rene Gallimard, a cisgender white man, recounting his time with Song Liling – a Chinese, non-cisgendered opera singer who presents as a woman and a man. Gallimard is a married French man living in Beijing in the 1960s who becomes enamored with Liling after hearing them sing “Un Bel Di” from Madama Butterfly. Gallimard is so taken with the story of Lieutenant Pinkerton and Cio-Cio-San that he imposes the characterization of Cio-Cio-San onto Liling, calling them “Butterfly” for most of the play. Dressed as a woman in traditional Chinese female clothing, Liling lets Gallimard continue to believe they are a woman as they spy on Gallimard for the Chinese government. By the end, Gallimard cannot accept Song and their male body, so their story ends in tragedy.

While the fact that Gallimard is white and Liling is Chinese is important, M. Butterfly would be a different story without Liling’s gender influencing the story. Gallimard first sees Liling dressed as a feminine, graceful opera singer, and it is dressed as such that Gallimard assumes Liling to be a woman with female anatomy. Liling goes to great lengths to maintain their feminine appearance and persona as they spy on Gallimard, dressing as a woman when not performing and buying a child to claim him as Gallimard’s and Liling’s son. Yet, in act three, scene one, Liling dresses as man to match his sex during their and Gallimard’s espionage trial in Paris. Then, in act two, he takes of his clothes to prove to Gallimard that Liling was always a man, regardless of how Liling presented their gender to Gallimard. Yet Gallimard refuses to accept song as anything but a woman – his Butterfly. If Liling had been a woman all along, Gallimard would have rejected Liling for being a woman who dared to use, manipulate, and spy on him, calling into question Gallimard’s masculinity and his sense of power and authority. Since Liling does not have female anatomy, Gallimard focuses on his former lover’s body not matching their womanly presentation and, therefore, Gallimard’s delusion of Liling being his Butterfly.

As important and influential as Liling’s gender is to the play’s plot, their gender also plays a significant role with the play’s audience. Although transgender people can be found in literature throughout history, the quantity of the gender identity’s representation is low. As such, many readers view Liling as transgender due to Liling’s preference to dress as a woman more often than necessary. In act two, scene four, Liling’s handler, Comrade Chin, calls out Liling for this preference, “…You’re wearing a dress. And every time I come here, you’re wearing a dress.”[2] Liling does not outright call himself a woman, though. In act three, scene two, during his physical reveal to Gallimard, Liling undresses for Gallimard in an attempt to convince him that Liling, regardless of clothing and anatomy, is still Gallimard’s Butterfly. Liling calls their time in the kimono and wig a part they played. They strip completely, revealing their male body, and then they have Gallimard touch their skin while they cover his eyes to remind his that the skin Gallimard is touching is the same skin he touched when Liling dressed as a woman. While Gallimard does accept Liling’s male body, he refuses to accept that his Butterfly is male. Liling insisting Gallimard accept their male body does not negate the opinion of reader’s that Liling is a transgender woman. The play contains enough evidence to support that opinion. Yet the play also contains enough support for another opinion on Liling’s gender: Liling is a cisgender male and a drag queen. Even though Liling dresses as a woman for acts one and two, using she/her pronouns anytime they are dressed thusly, Liling spends act three dressed as a man and uses he/him pronouns. A drag queen makes sense because they have their male identity for their everyday lives, and then they have their female persona when they perform, and Liling is a performer, an opera singer. With both transgender people and drag queens being negatively portrayed in the media and targeted in numerous bills in the United States, both readings of Liling’s character are valid and important because both interpretations show there is more to gender than man and woman, masculine and feminine.

In her essay, “We’re All Someone’s Freak,” Gwendolyn Ann Smith – a transgender woman, writer, and activist – discusses people’s need to put others in nice, neat boxes, to make others be an either/or: man or woman, normal or freak. Smith writes, “We just want to identify the ‘real’ freaks, so we can feel closer to normal. In reality, not a single one of us is so magically normative as to claim the right to separate out the freaks from everyone else. We are all freaks to someone.”[3] Like transgender people and drag queens are “freaks” in today’s society, Liling – whether transgender or a drag queen – was Gallimard’s freak. Gallimard could not put Liling in the nice, neat “woman” box, could not accept that he fell in love with a male body in woman’s clothing. Liling being Gallimard’s freak prevented the latter from accepting the former as they are, leaving Liling alone and Gallimard lost to his fantasy of his Butterfly.

The takeaway from this is that M. Butterfly would not be the lasting, influential story that it is without the role of Song Liling’s gender. Liling having a male body while dressing in women’s clothing shaped their relationship with Gallimard, played a significant role in their ability to spy on Gallimard, and lead to the tragic ending of Liling’s and Gallimard’s relationship. Transgender or drag queen, Liling was Gallimard’s freak, and Liling being who they were will continue to be valid and important in a reality where gender is a social construct.

[1] Mazure, Carolyn M. “What Do We Mean by Sex and Gender?” Yale School of Medicine, Yale School of Medicine, 19 Sept. 2021, medicine.yale.edu/news-article/what-do-we-mean-by-sex-and-gender/.

[2] Hwang, David Henry. M. Butterfly. Penguin Books, 1989, pp. 46.

[3] Smith, Gwendolyn Ann. “We’re All Someone’s Freak.” The Norton Reader: An Anthology of

Nonfiction, edited by Melissa A. Goldthwaite et al., 15th ed., W. W. Norton, 2020, pp.

145-47.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 13 of Productivity✨11/28/22

Finally back to being productive after Thanksgiving break! Today I prepared the next 3 lecture guides for my Art History class and did my discussion for my Asian-American literature class. I also visited my sister for dinner and got to see her cute kitties! Also, I got the grade back for my summary essay and I got 100% ☺️ Only a few more weeks of the quarter to go!

📖 Footnote to Youth- José Garcia Villa

🎵Love & Hate- the BREED

#studyblr#studyspo#study#study aesthetic#aesthetic#dark acamedia#university#art#art history#coffee and books#college girl#college student#premed#productivity#asian american literature#college#uni#lofibeats#books#reading#cats#cute cats

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sour Hearts, by Jenny Zhang, and orange spice tea. This book is a bruiser.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

That is the way it is with a wound. The wound begins to close in on itself, to protect what is hurting so much. And once it is closed, you no longer see what is underneath, what started the pain.

— Amy Tan, The Joy Luck Club

#Amy Tan#The Joy Luck Club#譚恩美#books#book quotes#quotes#literature#literary quotes#asian american literature#prose

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

two Kannada original poems in translation by AK Ramanujan

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Honeycrisp" by Piya Patel is available to read here

#short stories#short story#honeycrisp#piya patel#indian american literature#asian american literature#american literature#21st century literature#english language literature#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls#links to text

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

a story, li-young lee

#li young lee#poetry#spilled ink#godhood#girlhood is godhood#asian literature#asian american literature#literature#quotes#web weaving

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I could do girlhood again, I'd ask

to be scarier. Less whimpering--more pyromaniac

urges, more flirting with kerosene.

Sally Wen Mao, Drop-kick Aria

#Sally Wen Mao#Drop-kick Aria#Mad Honey Symposium#childhood#girlhood#pyromaniac#kerosene#poetry#poetry quotes#Asian American literature#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

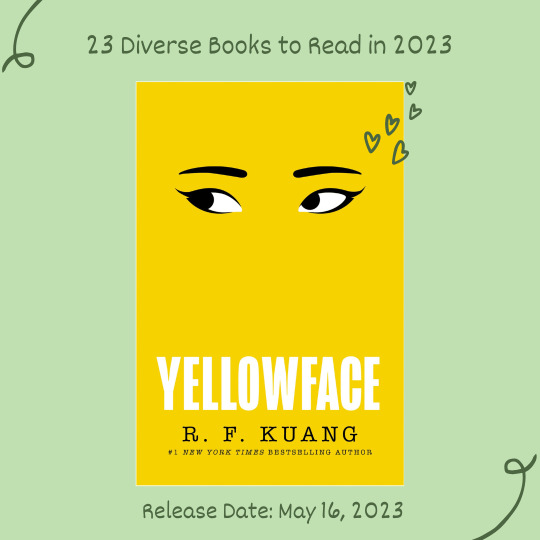

Diverse-Reads’ 23 Diverse Books to Read in 2023

Yellowface by R.F. Kuang / Pub date: May 16, 2023

Summary: Authors June Hayward and Athena Liu were supposed to be twin rising stars: same year at Yale, same debut year in publishing. But Athena's a cross-genre literary darling, and June didn't even get a paperback release. Nobody wants stories about basic white girls, June thinks.

So when June witnesses Athena's death in a freak accident, she acts on impulse: she steals Athena's just-finished masterpiece, an experimental novel about the unsung contributions of Chinese laborers to the British and French war efforts during World War I.

So what if June edits Athena's novel and sends it to her agent as her own work? So what if she lets her new publisher rebrand her as Juniper Song--complete with an ambiguously ethnic author photo? Doesn't this piece of history deserve to be told, whoever the teller? That's what June claims, and the New York Times bestseller list seems to agree.

But June can't get away from Athena's shadow, and emerging evidence threatens to bring June's (stolen) success down around her. As June races to protect her secret, she discovers exactly how far she will go to keep what she thinks she deserves.

With its totally immersive first-person voice, Yellowface takes on questions of diversity, racism, and cultural appropriation not only in the publishing industry but the persistent erasure of Asian-American voices and history by Western white society. R. F. Kuang's novel is timely, razor-sharp, and eminently readable.

#i'm SO excited for this book#rf kuang#diverse books#tbr#books#bookblr#book recommendation#to read#new books#new releases#booklr#asian american literature

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

By the time I was forty, the rigidity of my footbinding had moved from my golden lilies to my heart, which held on to injustices and grievances so strongly that I could no longer forgive those I loved and who loved me.

Lisa See, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan

9 notes

·

View notes