#as both a moment of asserting working class masculinity

Text

actually. SO many conflicting thoughts about the role effy’s gimmick and gimmicks like it play in the professional wrestling landscape. wrestling absorbs other artforms -- it’s mma but its also clown but it’s also soap opera and sometimes it can be burlesque. so by incorporating sexuality it’s swapping out one symbolic physical language for another. but also effy as the exaggerated portrait of homoeroticism provides a foil that reaffirms the heterosexuality of his opponents whether they go along with him or not. like the story of that mox match was the story of a masochist slowly seducing an angry macho straight man in a bar bathroom. Turning Mox into rough trade using beats taken directly from bdsm (the fishnets in the mouth, the cigarette being stubbed out on effy’s skin) while mox sells effy’s affection like it’s hardcore ultraviolence. but also mox can’t win (to win is to escape, in wrestling--the logic of the story doesn’t change until the match ends, so you are trapped in a world shaped by your opponent until the bell rings) until he kisses Effy first. he has to reciprocate, he has to initiate, he has to engage with effy’s language and mean it, he has to leave the world of masculine violence and be there in that bar bathroom in order to follow the narrative to the end.

#but also jesus god the cigarette#as both a moment of asserting working class masculinity#and power#and a punctuation of a sexually charged escalating sequence#like. the symbolic language here.#how much of this is on purpose?#is mox filling that specific archetype intentionally?#does he know what story he's telling?#also there is something that is just so much#about how effy uses physical affection as part of his symbolic wrestling language#in the same way that orange cassidy uses gesture#mox didn't sell the cheek kisses as kisses he sold them as strikes#i wish i'd done more media studies classes so i could have the language to talk about this!!#wrasslin#this is completely incomprehensible 2:30 am rambling but#there is#so much to unpack

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dr. Holligay Tries Things That Aren't Running: Group Power

So after the immense blow of the slings and arrows of outrageous inability to read yesterday, one might think that I would give up. But no! One week of failure is not a month, and so I pouted for an evening and then got up off my ass this morning to get back into the fray. There are still three more weeks, and while I am less than enthusiastic about losing five stamps worth of work, I'm not going to throw away the whole "getting an overpriced kitchen item" endeavor.

So yesterday, I took the new bingo card and worked out what my schedule would have to look like in order to get a solid bingo by Saturday, starting on Tuesday.

We find ourselves at Group Power.

Group Power reminds me a very important thing, which is that I hate taking group classes. This is not a "I'm antisocial and don't like people" thing, I am a very gregarious person who often enjoys a group activity, but working out is one of those moments where I figure it's between me and the power of my own will and not whatever a late-30s wine mom in ass-sculpting leggings is doing next to me* is doing.

Group Power asks the questions: What if we were doing lifting, which Holligay hates, but what if were doing it all together to a specified beat?

So I want you to picture me standing behind a step, the stack ones like in step aerobics. Now, I've gathered the things I seem to think we'll need for the class like a little robin feathering her nest: My bar, a few plates, a mat.

Then strides in the teacher. It's my boot camp teacher! Fantastic. Jessie--for that's what we'll call her--waves at me, tells me how happy she is I'm here, she's always wanted me to try this class, and then walks into the back and grabs two small plates, tossing them next to my bar.

With a big smile. 'You can lift heavier than that."

IF YOU SAY SO. I'm too weak to argue. I am Group Powerless. I deserve every bad thing that is about to happen to me, and, it is. I add the plates to my bar.

So the great thing about this is, every rep is shouted out. This is a gym class that people imagine in their heads when they think gym class. We are midway through upper body when I realize my bar is overloaded. It is too heavy for how fast I am doing these reps. I am suffering. But I can't stop. I can't stop, because I am weak, and I am in the middle of class, and in order to lower your weight, you have to stop and take the plates off your bar, loudly admitting to the entire class that you, personally and individually, are too weak for the weight you picked.

Because I am stupid, I would rather die than tell this entire class that my bar is too heavy. And I may get the chance, as I head into another overhead press. Is this mild assertion of my masculinity worth possible injury? "It is if you're not a pussy," says the Marlboro man in my head. Overhead press for two, now singles, go!

The whole class is like this! And the worst part is, when she does finally tell the class to lighten their bar, I have the mechanical intelligence, apparently, of a pine cone, and can't quickly get the plates moved off and on my bar. I am sweating over this while they are already starting the reps, and somehow both no one is looking at me and I feel the EYE OF SAURON DIRECTLY UPON ME, and I hold both in equal hands.

AND LIFT! AND SQUAT. TWO MORE!

Jessie comes up to me at the end, as I'm struggling like a tenacious field mouse to get the plates off the bar.

"DId you have fun?!"

I look up at her through my sweaty bangs.

"I'm going for a run."

*Holligay, you're a late 30s wine mom. Excuse you I am a whiskey mom and that means I look like the dyke trash I am when I work out. That Britney the wine mom in leggings can outlift me is both hurtful and irrelevant to the topic at hand.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Re: the Kristen Stewart Rolling Stone shoot

It's giving JD Samson. I guess even the gays can have a lil Y2K revival.

(I haven't even read the article. I am purely responding to the images before I go to work LOL.)

The #tag comments begging/joking about Kristen going on T, in her response to her own longing for "a little mustache, a happy trail" are very understandable. You all want to push her gender fuckery from fantasy into reality, from metaphor into the concrete, into what Saketopouou calls "the more and more" of gender OVERWHELM and of course that is HOT!!!

But even before Bella starts microdosing testosterone (or maybe she's already started, more power to her!), let us just pause, and fully appreciate this image in this moment. What if we take KStew at her word? What if this photshoot truly is "the gayest thing ever," in the grand tradition of Deep Lez aesthetics and a certain flavor of lesbian gender (which could never be TERFy because it is so clearly distinct from cis women's genders, is a creative response to different kinds of pain points, both fucking with and getting fucked over).

It reminds me of this passage, quoted in Sexuality Beyond Consent:

"I was female-assigned at birth," writes the queer theorist Kathryn Bond Stockton. "Though [my own sense was that] I was a boy… mistaken for a girl. And though I was, to my mind, the ultimate straight man seeking normally feminine women, I turned out a "lesbian," against my will-though in accord with my desires. As for my girlfriend she grew up, to her mind, normally feminine, as a rural Mormon raised in rural Utah. In her twenties, after her male fiancé died, after she didn't go on a mission, after she walked across the US for nuclear disarmament, she met lesbians and wished she could be one, so cool did they seem to her. But, she figured, she wasn't a lesbian. Long story short: I didn't want the sign ["lesbian"] but was pierced by it; she quite wanted it but didn't think she'd gain it. We have [both] been dildoed by th[at] sign. We've been pleasured by it, as it's come inside us-I've had to try to take it like a man. (2015)

Close up on Kristen Stewart on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. She's rubbing her clit underneath a jock strap. Read Sarah Tomasin Fonseca's essay in "It Came From the Closet" for a little foray into the erotics of jacking off into stolen male underwear. A truly young and otherwise disempowered dyke might steal underwear from a male relative, now we can buy what we like at the store, but the relationality is always there. Although the jock might get the most attention, Kristen is also wearing a pointelle thong in pure white cotton from Cou Cou Intimates, a brand which profits from Millennials sexualizing our girlhoods. They advertise to me on Instagram and I get skin shivers at the ability to choose, buy back and own the thong versions of underpants we wore even before men in AIM chatrooms asked us our bra sizes (when we were 11). And Kristen is wearing this delicate piece of panty in the men's locker room.

Part of the power of dyke sociality and sexuality is exclusivity. A "woman's" right to refusal can mean prioritizing other dykes, and asserting the irrelevance of straight men. And yet, in the realm of the sexual unconscious, we all know about each other. We all must deal with each other. In the words of Avgi Saketopoulou, we are all acting ON each other.

Much as the fetish clothing in the gay male leather scene comes from the uniforms of the armed forces, police, and working class, before it is transformed and inducted into delightful and perverted hiérarchies, Kristen plays with sartorial signals which might have their base in other genders, but which she uses to construct a gorgeous dyke existence.

The juxtaposition with men, not just with masculine trappings or locations, which are more easily taken over, was unsettling for me! I was scared for her! The image of her on the floor, mouth open: She's On Our Backs! But she's not, she's on the cover of Rolling Stone, the largest subscriber base is probably white Gen X men. Kristen on the floor lies in both the power and powerlessness in non-normative dyke sexuality. She's wearing an outfit that might make more sense in a leathermen bar -- decadent black leather vest, exposing jock strap -- in front of an objectified Black man. Who is he, and who is he to her? (Who is he to the dudes who subscribe to Rolling Stone?) He is jacked, with sweat (or more likely oil) artfully dripping down his washboard abs to the visible bulge in his gym shorts. A leather bar is a place to find danger, but this man is not at the leather bar. Together, they are in the men's locker room, a dangerous place for a queer or a woman. However, they seem disinterested in each other and Kristen is not afraid. She's skinny and milky (a weakling in many genders) and sitting like a neurodivergent queer, doing "hysterical clowning" with her knees up and posture hunched in front of a mirror in the men's locker room, next to a faceless white man with perfect posture and impossibly large biceps, and she also doesn't look afraid.

Her bangs have been cut with blunt scissors, messed up and sweaty. Nothing says queer like deliberately fucked up at home haircut. Finger in mouth, which reads submissive in straighter settings, but in queer orality, its giving top (if not dom) energy.

OK gotta go to work now, just wanted to blast off some associations before work!!!

#kristen stewart#rolling stone#dyke#jock strap#little girl underwear#avgi saketopoulou#kathryn bond stockton

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vicious impotence

A moment is inseparable from the ways in which it is discussed and understood. When people are aware of their inability to affect the material conditions of the moment itself, they become vicious in asserting the primacy of their interpretation of it. Well-compensated and facing neither encumbrance nor threat of censure, they screech before large crowds, bemoaning the fact that no one has listened to them. If only their interpretation had been accepted and agreed upon before the moment had happened, then it never would have happened, or it would have happened differently. They assure their audience that worse moments are still to come and that these, too, will be due to their perspective having received insufficient attention. The more they are listened to, the more they feel themselves ignored. Their inefficacy is proof of the urgency of their methods.

Classification becomes the order of the day. Beneath that--never spoken too loudly, as enunciation leaves one’s beliefs open to clear examination--there lies a churning river of conspiratorial mysticism. This happened because the people who did it are this way, and no one should pay any mind to how being that way made them do those awful things--it just did. When those people are around, these things will happen. They always will. Presence is action and action is presence, which is why we face such a vital imperative to identify presence whenever an action has taken place.

And so within hours of a few hundred psychotic dimwits breaking into the Capitol building, managing to kill a cop and several of their own in the process, our bleak commentariot had published hundreds of articles classifying the type of people who were involved. The raid was a coup, first and foremost, regardless of the fact that at no point was there any risk of the United States government being toppled. It was a coup because it was caused by whiteness, racism, masculinity, a lack of trans-positivity, gamergate, ableism, too few powerful women, too many bad ideas, too much free speech, too many jokes, not enough solemnity, not enough people listening to the things writers had said in the past and were saying now. Whatever you wanted to cause it had caused it, and it all came back to the presence of bad people who, by their nature, cause bad things.

Of course, I am as hapless and internet-deranged as everyone else, and so I made my own classifications. Surveying the crowd, I see a fair representation of the Trump base: racist internet perverts; young libertarian men who read 3 books a year and consider themselves intellectuals; 40-something blonde women who have been ejected from multiple Styx concerts; senior citizens who demand the TV in the Pep Boys waiting area be switched from Family Feud to Fox News because it’s been 25 minutes since they last tuned in and they need to make sure Obama still wants to kill them. The gang was all there, reveling in the strange power of their impotence, moving for the sake of movement, existing for the sake of existence. They had been told, and they believed, that their mere presence affects outcomes. They figured that all they needed to do was break in to where they think power unfolds and just stand around and then, by osmosis, power would be what they wanted it to be.

Like the liberals who despise and define them, the Trump people had confused moments with materiality. Those liberals share the same confusion, and they rushed to insert themselves and their perspectives into the moment. Yes, they said, these people actually did almost destroy Democracy. They had gotten into the building where elemental power is generated. Their particles brushed off into the magic power rays. Such an incursion cannot be allowed to happen again. These people must no longer be allowed to conceptually exist.

The moment trumps the materiality, as we can only influence the former. We are content to let these people wallow about in their homes until they OD or shoot themselves or their lungs melt--that’s their material demise, deserved and unimportant. But in the meantime we must erase their ability to influence the creation of moments. Their bodies can stay, for a while. Their mediated selves must be destroyed.

What are the implications here? To ask an obvious question: how can the Democrats continue to blame the dispossessed working class for their own immiseration if they can no longer tell these people to learn to code, since learning to code necessarily entails enmeshing oneself into the massive electronic surveillance and control mechanism we're now declaring off-limits to anyone whose beliefs fall an inch to the left or the right of the Democrat narrative du jour? And what are the implications for everyone else? Ours is a flimsy society built upon layers and layers of obvious contradictions, sure, but what will things look like when those contradictions are enforced with the viciousness of our carceral state, even as they shift as rapidly as social media demands our perceptions to change?

When I said “Democrat narrative du jour,” I mean DU JOUR. As in, it changes by the day, and one day's narrative will very often directly contradict that of the previous day. This is how all cops are bastards and we should abolish all policing but also we need to give police more resources and leverage to brutalize the people who we don't like. This is how gender is both a meaningless social construct and an innate facet of one's being that is so inimical to their identity it should determine whether or not they receive access to basic social decency. This is why empowered women are every bit as tough and competent as their male counterparts and also they are delicate waifs who should never be exposed to scrutiny or criticism. This is how downplaying race amounts to a racist facade of "colorblindness" and also acknowledging race is a hateful act of dehumanization. This is how a cop can find himself getting beaten to death by a crowd bedecked in Blue Lives Matter regalia.

You can't simply adhere to the rules, because there are no rules to follow. In order to avoid censure, one must stay connected.

So what will become of the digitally dispossessed? If we achieve Democrat Utopia and nothing changes materially but the internet is restricted so only those who adhere to officially sanctioned narratives are allowed to attempt to make sense of anything, where does that leave the masses who were shunted away? Is this going to make them less disaffected? Less volatile? What are you idiots hoping to achieve, here?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Willow Run | Ch. 2

Summary: On a horse ranch in Texas, life is far simpler than on the streets of Bakubah, but Syverson has a bad habit of taking in strays of all kinds, no matter what demons may be after them.

Pairing: Captain Syverson x OFC

Word Count: 3.3K

Warnings: Nothing in this chapter.

A/N: You guys!!!! Thank you so much for all the love you’ve shown on this fic! It means a lot and I appreciate each and every one of y’all!

CHAPTER 1 |

_______________________________________________

Message me if you’d like to be added/removed from the tag list!

@fumbling-fanfics @skiesfallithurts@pinkpenguin7@madmedusa178 @crushed-pink-petals @fangoria@bluestarego@caffeinated-writer @my–own–personal–paradise@tastingmellow @honeychicana @lua-latina @angelicapriscilla @swiftyhowlz @schreiberpablo @pinkwatchblueshoes @kirasmomsstuff @prettypascal @blacklotus-of-the-black-kingdom @nardahsb @playbucky @veryfastspeedz @queen-of-the-kastle @freyahelps @cajunpeach @godlikeentity @captainsamwlsn @nakusaych9@katerka88 @katerka88 @kirasmomsstuff@melaninmimii@alienor-romanova @downtowndk @redhairedmoiraandtheliferuiners @safiras @agniavateira @henryfanfics101 @fatefuldestinies @iloveyouyen @justaboringadult @xxxxxerrorxxxxx @readings-of-a-cavill-lover @alyxkbrl @bloodyinspiredfuck @peakygroupie @stxphmxlls @trippedmetaldetector @radaofrivia @speakerforthedead0-blog @oddsnendsfanfics @shadyskit @snowbellexx @leilabeaux @cavillunraveled @kmhappybunny

Wolf did the trick, and though it took her an extra moment to be convinced, Sasha allowed Syverson to carry her inside, the house blessedly cool thanks to an HVAC system that had been retrofitted a few years prior.

Once inside, Syverson set her onto one of the high chairs that took up one side of the kitchen counter. Like most everything else in the house, the kitchen was bright, airy and spacious. Curiously, the appliances seemed to come straight from the past; the sink, the fridge, even the oven all dated back to at least the fifties in appearance though they had all been fitted with new technology.

"Bathroom's just down at the end of the hall if you need it. Lemme just wash my hands and I'll fix somethin' up real quick," he explained, pointing down the hall before moving to the old farmhouse sink to start washing up.

As he prepped, the sound of two sets of paws grew louder and louder, nails clicking on the hardwood flooring. A quick glance over his shoulder and Syverson's smile grew tenfold, although he quickly took action, blocking the path of the two puppies who were eager not only for scraps, but to find out who the new human was.

"You're not afraid of dogs, are you? I completely forgot, I'm so sorry," he stammered, Syverson starting to herd them back towards his office which was just a few steps away from the kitchen. One of them was clearly the boss as he pushed right past Syverson with an upturned nose, trotted over to Sasha, sat down and grunted as though asking her who she was. Syverson chuckled, a little embarrassed as he turned his attention to the little mastiff, picking him up easily before tucking him into his chest.

"Don't mind the grunting. He does that when he wants something from someone."

The other dog, a hearty little guy, followed his buddy's example and sat down next to Sasha’s feet, looking up at her with curiosity.

"This is Hudson, and that down there, is Goliath," he introduced, each dog making a noise as his name was called. "They're strays. Up on all their shots though. Perks of knowing a vet."

Syverson set the puppy down just as a third set of paws clipped along the ground, the sound much heartier than either of the two pups. Although curious about the newcomer, the older dog simply sniffed at Sasha’s general direction before sitting down in her dog bed by the back door of the kitchen. With age came wisdom, and the four year old German Shepard knew full well her owner never went a morning meal without giving her at least a piece of bacon.

“And this beautiful lil’ lady is Aika. She’s been with me since...For a long time,” he asserted, catching himself before divulging information he wasn’t sure Sasha was ready to hear yet. Given her injuries, he wouldn’t have been surprised if she believed the stereotype of military men being prone to violence. Keeping it to himself was his best option at the moment.

“They’re all so cute!” Sasha smiled, her eyes still bright, every moment that passed leaving her feeling more and more relaxed around Syverson, something she didn’t even notice as she watched the puppies frolic around Aika, who paid them no heed and let them bounce all over her and her very comfy-looking bed.

After making sure the puppies wouldn’t get into any mischief while he cooked, Syverson washed his hands again, drying off before extending a hand to Sasha.

“I never did get your name,” he smiled sheepishly.

“Oh, right. It’s Sasha. Sasha Bettencourt. How ‘bout you?”

“Kyle Syverson. You can just call me Sy, though. Everyone does.” Shaking hands with Sasha, he couldn’t help but let his smile get a little bigger, mirroring the one he was getting from the young woman.

“Sy, can I use your bathroom?” Sasha asked once they’d let go of each other's hands, her own expression slightly embarrassed since she knew just how dirty she was. Given what the house looked like both inside and out, she couldn’t imagine the bathroom being anything less than spotless.

“Of course!” Syverson said, moving around the counter in a hurry, ready to steady her as she got down off the chair. “You alright to make it there on your own?” He asked, the concern returning to his expression as he waited to see if she’d drop like she had outside. “Take your time,” he told her gently, the words spoken not only as a warning not to walk quickly, but as a reminder that she no longer needed to rush now that she was safe and out of the sun.

Testing her legs, Sasha found them working well enough and with a nod, she ambled her way down, relieved to have her body functioning at least somewhat close to normal again. Finding the door easily enough, Sasha closed and locked it behind her, taking a moment just to breathe. Looking at her reflection in the mirror, she was surprised Syverson had let her anywhere near his property, let alone inside his house. Gruesome was putting it mildly.

The bathroom was charming and just as beautifully-appointed as the rest of the house. Sasha wondered, not for the first time, if Syverson had a wife who’d done all the decorating. For a man who was so, well, masculine, the house screamed of a woman’s touch. She reminded herself to ask him after she got out.

Though she was only planning on washing her face, Sasha took one look at the sunflower-sized shower head that sat on top of the clawfoot tub and was taking off her dirty clothes without a second thought.

Syverson heard the shower going and couldn’t help but smile; he'd have done the exact same thing. Shaking his head, he began preparing breakfast for two; something he hadn’t done in a long time.

Soon enough, Sy was operating at full steam. Eggs in a skillet, hash browns frying and sausages turning a delicious golden brown. He managed everything with the ease of someone who'd taken classes at the very least and as he worked, he sang an unrecognizable tune, the soft smile never leaving his face. It was easy for anyone to see that the man was at peace in his own home, and that he wasn't the type to sit idly for any length of time.

As the cool water poured over her still-overheated skin, Sasha couldn’t help but sigh in utter contentment, finding her muscles truly loosening and the panic in her veins dissipating for the first time all day. She’d unknowingly walked to a haven, and while she still felt guilty for putting Sy out, especially since he was out there cooking her breakfast, Sasha vowed not to be so hurried to leave if he didn’t want her to.

There was one stark problem that Sasha only realized once she got out of the shower; she had no clean clothes to wear. Feeling stupid for her lack of foresight, she begrudgingly put her dirty clothes back on after quickly shaking them off in the tub, hoping to get at least some of the dust off. Though she felt a million times better, memories of the road still clung to her, leaving Sasha pensive and quiet as she left the bathroom.

“Feelin’ better, mama?” Sy asked with a wry smile, his back still to her as he began to plate breakfast, giving both plates a generous helping of eggs, sausage, hashbrowns and pancakes. Though Sy was known to eat like a horse, he never worried about his portions, knowing he’d work it all off down at the stables.

“I’m sorry. I just...I was so dirty.” Sasha stammered, looking as though she’d stolen something out of the house, even though she’d done nothing of the sort.

Turning, he gave her a bright smile which quickly turned into an impressed look at the visible difference. She was beautiful, even with all the cuts and bruises that marred her otherwise-smooth skin.

"It-It's no problem. Should've told me, I would've grabbed you some clothes to wear while I threw yours in the wash," he answered after coming back to his senses, Syverson shaking his head as though he'd been startled out of a dream.

A closer inspection of her clothes showed that the washer wouldn't do much good. Tattered and dirty as they were, she was better off throwing them out. Syverson knew it probably wouldn't happen though, as girls were attached to their clothing like guys were attached to their cars. Still, he would broach the topic again after they'd eaten.

"Here we go. One Syverson special, on the bar," he grinned at her as he slid her plate in front of her seat at the kitchen counter, Sy setting his own plate down next to hers. Grabbing his coffee, a glass of orange juice for her, and a bottle of his favorite hot sauce, Sy made sure the salt, pepper, syrup, and napkins were all within reach before taking his seat.

“Go on, dig in,” He urged, pointing at Sasha’s plate with his chin, Syverson wondering when the last time she ate was. She was thin, almost alarmingly so, and aside from her swollen belly, there wasn’t nearly enough meat on her bones to be carrying another human. If she stayed, Syverson knew he’d see to it personally that she ate her three squares a day, and that she got as many nutrients as she needed to grow the little one inside her.

Tentatively, Sasha took a bite of the pancake first, hers slathered in syrup the same way Sy’s were, something she thought endearing. Her eyes rolled back and she practically swooned as the familiar taste hit her tongue, Sasha melting a little in her seat.

“This is really good,” she managed to say after swallowing, her face showing nothing but awe that Sy had made it all himself. Where she came from, men were never in the kitchen unless they were getting a beer. It shocked her, to say the least.

“Thank you, again, for all of this. I don’t...I don’t have any way of repaying you,” Sasha murmured after another bite, looking up at Sy with regret. She had to do something in return for all his generosity, she just didn’t know what she’d be able to manage, given she’d left her home with just the shirt on her back.

“There’s no need, honest. I’m not doing this ‘cause I’m lookin’ for something in return. I’m doing it ‘cause it’s the right thing to do. Couldn’t just leave ya to burn to death out there. What kinda animal would I be if I did that? Nah, no repayment necessary, mama. Just...don’t go walkin’ into the middle ‘a nowhere without water and cover again. That’s all I ask,” Syverson replied, biting his tongue to keep from saying what he actually wanted to say, knowing that doing so would spook her. Asking a near-stranger to stay as long as she needed and not worry about lifting a finger while doing so usually didn’t go over well in most circles.

They ate in silence for a bit, Sasha taking in the house and occasionally slipping a bit of food to one of the dogs, making sure Sy wasn’t looking while she did so.

“Your home is beautiful. Looks like it’s straight out of a magazine,” she mused, blushing slightly when she realized how silly she must’ve sounded.

"Thank you. It belonged to my parents, but they've decided to live the high life down in Florida now. Boating, fishing, tanning, the usual retirement stuff. They visit every now and then, but they've got their own little house not far from here, so the place is all mine," he replied with a big smile, Syverson not even realizing that he was divulging so much information in one answer. Despite years of military training on how to keep mum about personal and secure information, at home, Syverson was an open book who wore his heart on his sleeve.

“As for it lookin’ like it’s out of a magazine...Well, that’s ‘cause it’s been in a few. Couple ‘a years back, some hoity toity types came and shot the place. It ended up in a few rags. Mom’s got ‘em all stashed away somewhere.”

Feeling brave when her comment wasn’t met with ridicule, Sasha remembered her question from earlier, a smirk crossing her face as she spoke.

“I find it really hard to believe it’s just you here.”

Sy laughed heartily at the idea of there being someone else on the ranch. Sure he occasionally had help (aside from his two stable hands), especially during foaling season, but that usually just consisted of his friends coming down for a few days.

"It's just me, the dogs, and the horses. I’ve got some guys that help with the stables, but they don’t live here," he assured her, shaking his head in amusement before taking another bite.

“It’s just….Well, it’s so clean and decorated so nice,” Sasha said the words without thinking, instantly looking down and away, fully expecting that she’d offended him by assuming he couldn’t look after himself.

“The place has a woman’s touch ‘cause my mom decorated it and I couldn’t be bothered to change it. As for the cleaning, well, I don’t like livin’ in filth any more than anyone else, so I clean a bit everyday and by the end of the week, everything’s spick and span. It becomes a routine after a while.” Sy chuckled, answering the underlying question of why it didn’t look like every bachelor pad ever.

Sasha grinned, blushing as she nodded her understanding. “I figured you had a wife, but mom works too.”

“Yeah, don’t got one of those.” Syverson shook his head, eyebrows going up comically as he finished his last bite.

“What? You have something against the institution of marriage?” Sasha laughed.

“First off, calling it an ‘institution’ makes it sound like a loony bin. Secondly, I have nothing against it. All the women I’ve dated have seemed to hate the idea though, hence no ring.” He explained with a shrug, giving her a wink as he stood and loaded his plate into the dishwasher before leaning against the other side of the counter, waiting for Sasha to finish her own meal.

“I’m gonna go get Wolf, as promised. Stay here where it’s nice and cool, and I’ll come grab ya when I’m back.” Sy explained once she was done, taking her plate and swapping it for a glass of water, the liquid cool enough to make the glass sweat near-instantly. Sasha nodded, the excitement returning to her eyes at the prospect of meeting the horse.

Slipping on his boots, Sy stopped and gave Aika a piece of sausage before giving her the command to stay. Though his eldest dog usually followed him everywhere, he wanted her to look after Sasha while he was gone, if only for his own peace of mind.

Sy took the ATV down to the stables and made quick work of tacking up Wolf, speaking to the horse in gentle, hushed tones the whole time.

“There’s someone I want you to meet, bud. You gotta be gentle, ‘cause she’s hurt pretty bad, okay?” He said once he’d given the straps one last check, smiling up at his Friesian and giving him a good pat to the shoulders. Climbing on, gave the stable a quick check before riding out, going an easy pace until he crested the hill.

Sasha knew she should have waited inside, but curiosity got the better of her and she wandered out, wanting to see Syverson come up from the stables. She wasn’t disappointed at what she saw. With his red plaid shirt, fitted jeans, boots, and baseball cap, he was every inch the modern cowboy and Sasha couldn’t stop the butterflies that filled her stomach even if she’d wanted to.

Sy saw her the moment he got to the top of the hill and with a shake of his head and a beaming smile, he signaled Wolf to gallop, knowing he had plenty of time to slow down before he hit the house. There was no feeling like riding a horse at full speed, and never once did Sy think he’d grow tired of the exhilaration it brought; it was better than any rollercoaster and no one could tell him different.

“Didn’t I tell you to stay inside, mama?” He called as he came within earshot, Sy slowing Wolf with ease and grace, the two coming to a full stop a few steps from the porch.

Blushing but smiling ear-to-ear, Sasha nodded, knowing she’d been caught.

“I couldn’t help it. I wanted to see y’all two coming down the hill.” She admitted, taking slow, tentative steps towards the massive horse and his equally big rider.

“Like you would a dog. Palm up, let ‘im give you a sniff,” Sy instructed gently, patting Wolf’s neck as he watched Sasha approach.

“Hi, Wolf. You’re a very handsome boy,” Sasha smiled, extending her hand and giggling softly when Wolf sniffed at it with enthusiasm. After a moment, Wolf nuzzled first at Sasha’s face and then at her belly, seeming to know that the new person Sy had been talking about was carrying another person with her.

Sy’s smile was sappy as he watched the interaction, knowing for certain that if his favorite horse liked Sasha, then she was good people. Horses never had a reason to feign affection, and they were smart enough to only offer it when the person was right. By Wolf’s account, Sasha was second only to Sy himself.

“He likes you,” Sy murmured, adjusting one of Wolf’s long braids, letting Sasha take her time.

“Feeling’s mutual, isn’t it, Wolf?” Sasha beamed, nodding her head in time with Wolf, laughing happily when the horse let his head slump onto her shoulder.

“Alright, that’s enough there, mister. Layin’ it on a lil’ thick,” Sy joked, patting his neck, his eyes never once leaving Sasha’s smile; he wouldn’t admit to being smitten just yet, but her having Wolf’s approval didn’t hurt matters in the slightest.

“I gotta get the rest of the bunch turned out to pasture. I’ll be back around one for lunch, but until then, why don’t you head on in and have a rest? There’s clean clothes in the laundry room if you wanna change into something a lil’ more comfortable. Pretty sure there’s some basketball shorts in there with a drawstring so they don’t fall off ya,” Sy gave her a wink, “and if you wanna take a dip, the pool’s good to go, though I don’t got a bathin’ suit for ya, unfortunately.”

As he spoke, he turned on a pair of walkie-talkies, Syverson bending down to hand Sasha one. “Keep this close, and just press the button to talk. I’ve got mine on my belt, so I’ll hear ya no matter what. Just lay back and relax. You’re good here, for however long you need.”

By the time he was finished speaking, Sasha had tears of gratitude in her eyes, and giving Wolf a final scratch to his nose, she nodded, managing to give her rescuer a big smile.

“Thank you. So much,” she whispered, not trusting her voice to get louder. Sy nodded, his eyes gentle and understanding. A moment of silent connection passed between them before Sy clicked his teeth and tugged at the rein, turning Wolf with ease.

“No walkin’ out in the sun, mama. I mean it!” Sy called over his shoulder with a wide grin, waving as he nudged Wolf back into a full gallop, the pair making it up the hill in no time at all before disappearing over the horizon, leaving Sasha with a warmth that spread throughout every fiber of her being, a feeling she hadn’t experienced in years.

#henry cavill#syverson x ofc#captain syverson#captain syverson fic#fic#deathonyourtongueoriginals#willow run

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consider: The effeminists

Effeminist—(historical) A member of a male homosexual movement opposing prejudices against effeminate behaviour. —Wikipedia

The next quote is from Jeanne Cordova’s When We Were Outlaws. She was a major figure in the lesbian feminist movement and created the most prominent lesbian newspaper of the time, The Lesbian Tide. This part of her autobiography is set when the lesbians employeed at the gay center (who created some of the first health care programs for women alcoholics, btw) are shoved out of power. Most of the gay male employees at the GCSC were fine with what was clearly manipulative and misogynistic bullshit that would disempower an entire neighborhood of poor, lower-class women. However, one group of men stood by the lesbians:

“In recent weeks a handful of the gay male employees [at the Gay Community Services Center] had begun to support us, calling themselves “effeminists,” a term used by radical left wing of the gay movement. Effeminists glorified in the name “gay faeries” and understood that the straight world mocked them because they as (f-slur) identified with women. They championed feminist principles like lesbian equality in the gay movement. They were usually feminine, rather than butch gay men, and they became our natural allies.” (Cordova 97-98)

The Effeminists’ 1973 Manifesto is below, transcribed from this archive:

The Effeminist Manifesto (1973)

Steven Dansky, John Knoebel, Kenneth Pitchford

We, the undersigned Effeminists of Double-F hereby invite all like-minded men to join with us in making our declaration of independence from Gay Liberation and all other Male-Ideologies by unalterably asserting our stand of revolutionary commitment to the following Thirteen Principles that form the quintessential substance of our politics:

On the oppression of women.

1. SEXISM. All women are oppressed by all men, including ourselves. This systematic oppression is called sexism.

2. MALE SUPREMACY. Sexism itself is the product of male supremacy, which produces all other forms of oppression that patriarchal societies exhibit: racism, classism, ageism, economic exploitation, ecological imbalance.

3. GYNARCHISM. Only that revolution which strikes at the root of all oppression can end any and all of its forms. That is why we are gynarchists; that is, we are among those who believe that women will seize power from the patriarchy and, thereby, totally change life on this planet as we know it.

4. WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP. Exactly how women will go about seizing power is no business of ours, being men. But as effeminate men oppressed by masculinist standards, we ourselves have a stake in the destruction of the patriarchy, and thus we must struggle with the dilemma of being partisans – as effeminists – of a revolution opposed to us – as men. To conceal our partisanship and remain inactive for fear of women’s leadership or to tamper with questions which women will decide would be no less despicable. Therefore, we have a duty to take sides, to struggle to change ourselves, to act.

On the oppression of effeminate men.

5. MASCULINISM. Faggots and all effeminate men are oppressed by the patriarchy’s systematic enforcement of masculinist standards, whether these standards are expressed as physical, mental, emotional, or sexual stereotypes of what is desirable in a man.

6. EFFEMINISM. Our purpose is to urge all such men as ourselves (whether celibate, homosexual, or heterosexual) to become traitors to the class of men by uniting in a movement of Revolutionary Effeminism so that collectively we can struggle to change ourselves from non-masculinists into anti-masculinists and begin attacking those aspects of the patriarchal system that most directly oppress us.

7. PREVIOUS MALE-IDEOLOGIES. Three previous attempts by men to create a politics of fighting oppression have failed because of their incomplete analysis: the Male Left, Male Liberation, and Gay Liberation. These and other formations, such as sexual libertarianism and the counter-culture, are all tactics for preserving power in men’s hands by pretending to struggle for change. We specifically reject a hands by pretending to struggle for change. We specifically reject a carry-over from one or more of these earlier ideologies – the damaging combination of ultra-egalitarianism, anti-leadership, anti-technology, and downward mobility. All are based on a politics of guilt and a hypocritical attitude towards power which prevents us from developing skills urgently needed in our struggle and which confuses the competence needed for revolutionary work with the careerism of those who seek personal accommodation within the patriarchal system.

8. COLLABORATORS AND CAMP FOLLOWERS. Even we effeminate men are given an option by the patriarchy: to become collaborators in the task of keeping women in their place. Faggots, especially, are offered a subculture by the patriarchy which is designed to keep us oppressed and also increase the oppression of women. This subculture includes a combination of anti-women mimicry and self-mockery known as camp which, to its trivializing effect, would deny us any chance of awakening to our own suffering, the expression of which can be recognized as revolutionary sanity by the oppressed.

9.SADO-MASCULINITY: ROLE PLAYING AND OBJECTIFICATION. The Male Principle, as exhibited in the last ten thousand years, is chiefly characterized by an appetite for objectification, role-playing, and sadism. First, the masculine preference for thinking as opposed to feeling encourages men to regard other people as things, and to use them accordingly. Second, inflicting pain upon people and animals has come to be deemed a mark of manhood, thereby explaining the well-known proclivity for rape and torture. Finally, a lust for power-dominance is rewarded in the playing out of that ultimate role, The Man, whose rapacity is amply displayed in witch-hunts, lynchings, pogroms, and episodes of genocide, not to mention the day-to-day (often life-long) subservience that he exacts from those closest to him.

Masculine bias, thus, appears in our behavior whenever we act out the following categories, regardless of which element in each pair we are most drawn to at any moment: subject/object; dominant/submissive; master/slave; butch/femme. All of these false dichotomies are inherently sexist, since they express the desire to be masculine or to possess the masculine in someone else. The racism of white faggots often reveals the same set of polarities, regardless of whether they choose to act out the dominant or submissive role with black or third-world men. In all cases, only by rejecting the very terms of these categories can we become effeminists. This means explicitly rejecting, as well, the objectification of people based on such things as age; body; build; color; size or shape of facial features, eyes, hair, genitals; ethnicity or race; physical and mental handicap; life-style; sex. We must therefore strive to detect and expose every embodiment of The Male Principle, no matter how and where it may be enshrined and glorified, including those arenas of faggot objectification (baths, bars, docks, parks) where power-dominance, as it operates in the selecting of roles and objects, is known as “cruising.”

10. MASOCH-EONISM. Among those aspects of our oppression which The Man has foisted upon us, two male heterosexual perversions, in particular, are popularly thought of as being “acceptable” behavior for effeminate men: eonism (that is, male transvestitism) and masochism. Just as sadism and masculinism, by merging into one identity, tend to become indistinguishable one from the other, so masochism and eonism are born of an identical impulse to mock subservience in men, as a way to project intense anti-women feelings and also to pressure women into conformity by providing those degrading stereotypes most appealing to the sado-masculinist. Certainly, sado-masoch-eonism is in all its forms the very anti-thesis of effeminism. Both the masochist and the eonist are particularly an insult to women since they overtly parody female oppression and pose as object lessons in servility.

11. LIFE-STYLE: APPEARANCE AND REALITY. We must learn to discover and value The Female Principle in men as something inherent, beyond roles or superficial decoration, and thus beyond definition by any one particular life-style (such as the recent androgeny fad, transsexuality, or other purely personal solutions). Therefore, we do not automatically support or condemn faggots or effeminists who live alone, who live together in couples, who live together in all-male collectives, who live with women, or who live in any other way – since all these modes of living in and of themselves can be sexist but also can conceivably come to function as bases for anti-sexist struggle. Even as we learn to affirm in ourselves the cooperative impulse and to admire in each other what is tender and gentle, what is aesthetic, considerate, affectionate, lyrical, sweet, we should not confuse our own time with that post-revolutionary world when our effeminist natures will be free to express themselves openly without fear or punishment or danger of oppressing others. Above all, we must remember that it is not merely a change of appearance that we seek, but a change in reality.

12. TACTICS. We mean to support, defend and promote effeminism in all men everywhere by any means except those inherently male supremacist or those in conflict with the goals of feminists intent on seizing power. We hope to find militant ways for fighting our oppression that will meet these requirements. Obviously, we do not seek the legalization of faggotry, quotas, or civil-rights for faggots or other measures designed to reform the patriarchy. Practically, we see three phases of activity: naming our enemies to start with, next confronting them, and ultimately divesting them of their power. This means both the Cock Rocker and the Drag Rocker among counter-cultist heroes, both the Radical Therapist and the Faggot-Torturer among effemiphobic psychiatrists, both the creators of beefcake pornography and of eonistic travesties. It also means all branches of the patriarchy that institutionalize the persecution of faggots (schools, church, army, prison, asylum, old-age home).

But whatever the immediate target, we would be wise to prepare for all forms of sabotage and rebellion which women might ask of us, since it is not as pacifists that we can expect to serve in the emerging world-wide anti-gender revolution. We must also constantly ask ourselves and each other for a greater measure of risk and commitment than we may have dreamt was possible yesterday. Above all, our joining in this struggle must discover in us a new respect for women, a new ability to love each other as effeminists, both of which have previously been denied us by our misogyny and effemiphobia, so that our bonding until now has been the traditional male solidarity that is always inimical to the interests of women and pernicious of our own sense of effeminist self-hood.

13. DRUDGERY AND CHILDCARE: RE-DEFINING GENDER. Our first and most important step, however, must be to take upon ourselves at least our own share of the day-to-day life-sustaining drudgery that is usually consigned to women alone. To be useful in this way can release women to do other work of their choosing and can also begin to re-define gender for the next generation. Of paramount concern here, we ask to be included in the time-consuming work of raising and caring for children, as a duty, right and privilege.

Attested to this twenty-seventh day of Teves and first day of January, in the year of our falthering Judeo-Christian Patriarchy, 5733 and 1973, by Steven Dansky, John Knoebel, and Kenneth Pitchford.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think I'm talking about confidence, I'm not too sure.

I was fifteen when I first saw Great Teacher Onizuka. My friend had lent me the DVD set (as you did when it was 2008) and I was about to spend the day watching it, feigning some illness to get out of school for the day. I needed some time alone, to process everything that had been going on around me.

For context, my parents were in the middle of a divorce. My mum, the most amazing person in the world to me, was not having a good time and I was not at all possessed with the skills to help her cope. Processing the concept of divorce, while trying to mediate the two adults going through it, wasn’t something I could handle. I didn’t know what I was doing. I needed a whole day away from friends and away from parents. While everyone was at their day job, I could think about everything and nothing, uninterrupted.

My attempt at getting out of school worked, however it came with a caveat. Mum had decided she’d take the day off with me. Feeling defeated but still stubborn, I insisted that if she was going to stay home too that we were watching GTO. I really had no idea what I was getting myself into.

GTO begins with our protagonist, Eikuchi Onizuka, squatting down by a payphone, trying to stare up the skirts of some high school girls coming down the nearby escalator. That’s a bold open. Two delinquents notice this and attempt to then extort him for cash. He promptly beats them up, forcing them to use all the money they have to buy him some food from the nearby convenience store. This scene establishes a few things straight off the bat: Onizuka is, first and foremost, a pervert and he’s physically strong but not to the point of unfairly asserting dominance over others. Onizuka dreams of being a teacher of all things. He wants to be the teacher he never had, being there for students outside the classroom as well as in. The series showcases Onizuka using his ex-biker gang leader skills and sheer determination to change the attitude of the antagonist students in his class. Each week he solves the reason behind their resistance toward him and they join his team until eventually he really is the Great Teacher, Onizuka.

The first delinquent problem Onizuka solves is that of Mizuki Nanako. Her parents aren’t divorced but they’re not exactly doing well. Ever since her father’s company started doing well and they moved into a mansion, she feels as though her parents just aren’t seeing eye to eye anymore. She blames it on a simple wall separating her parents’ private rooms. Before it got put up, her parents would talk and laugh together, sharing in their joys but also their defeats. Then before she knew it, they put a wall up and stopped sharing anything at all.

So, Onizuka arrives at her house. He’s got a bandana tied around his head, his abs gleaming as he’s smoking a cigarette. More importantly, he’s holding a sledgehammer, ready to demolish that wall. With her parents yelling at him threatening to call the police, Onizuka ascends the staircase and begins to take down that wall. Every powerful swing, shaking the wall and cracking the foundation.

(What a man what a man what a man what a might good man)

It felt cruel watching this scene with my mum. Here we were, two people still trying to process a big life event, opting to spend the day away from the problem. Here Onizuka was, just smashing through the problem with nothing but conviction, stupidity and sheer confidence. I couldn’t quite conceptualise the thought just yet but I think I envied that confidence. I wanted to be able to take a sledgehammer to this invisible problem and fix it. I didn’t know what an actual sledgehammer would solve nor was I even able to figure out what my situational sledgehammer would be, I just knew I wanted to be more like that. I wanted that confidence; I just didn’t know what it was yet.

Confidence. A complete assuredness in your actions. You may not have any idea of the outcome of said actions but you’re certain in the choice you made taking them. Maybe that’s just one definition. I struggle to this day with how to define confidence, I’ve been confident at different times in my life for different reasons. Mainly it’s been something I’ve found as I’ve gotten older though.

I struggled a lot with it when I was younger. I’d struggle to find it and when I did there was someone there trying to take it from me almost immediately. Pink polos were gay, skinny jeans were gay, being interested in anything outside the norm was gay as well. I wasn’t bullied by any means but there was always somebody around to tell you what they thought. I’d fold under that kind of pressure. I remember when I was 10 and we were in music class, I sang a little too loud and the popular girls behind me started pointing and laughing, clipping me before I got too sure of myself.

I got older and I thought I’d found confidence through weight training, but it was just arrogance. I genuinely thought I was better than other people in my creative writing class because I picked heavy things up and put them down. Of course, this had a drawback, whenever I’d meet someone bigger than me, I’d feel pathetic, jealous and inferior. I thought I’d rid myself of this arrogance when I started studying Japanese. My initial study was diligent and excessive. I’d have two Japanese classes a week and spend the rest of my time after work revising. Looking back now it was necessarily efficient studying, but in terms of time put in the hours were there. I believed I was working hard, which led to this arrogance in my abilities. An arrogance that was swiftly cut down whenever I met somebody better than me.

So, I always arrived at this juncture where I’d learn a new skill or hobby and wonder how to be confident in myself without comparing myself to others. I didn’t quite know how to praise myself for doing well at the gym or learning something new in Japanese without immediately comparing myself to others. It meant that I’d occasionally have these emotional highs when I achieved something only to be brought down to earth when I saw that somebody could do it better. I didn’t know how to make my achievements my own. The confidence I had was too fickle, it didn’t come from within and it often led to feeling superior to others based off of a single quantifier.

I was still uncomfortable with myself. I wanted outside validation which led to comparison, boasting and arrogance. I didn’t realise that I couldn’t get any of that from anyone else, it all had to come from within.

It’s taken me 14 years, but Onizuka finally made sense to me. I was watching the incredibly famous (in Japan) live action version of GTO one night, which turned into a nostalgia trip as all the episodes were almost identical to their anime equivalent. As I was watching I was wondering why I still hold this fictional character in such high regard, of all the powerful charismatic anime protagonists I watched in my teenage years, why does Onizuka persevere?

It’s because he’s kind of a dork.

(Get you a man that can do both)

Along with the confidence and strength that being a protagonist in a medium geared towards young boys affords you, Onizuka also has some very human flaws and vulnerabilities. The intense scenes like surprise renovating Nanako’s house or rescuing a whole bunch of kids from a gang are always juxtaposed with him being absolutely wayward in so many other aspects of life. He lives at the school because he can’t afford rent, he’s 26 and never had a girlfriend and his only friends are his students. We are always shown that his confidence isn’t intrinsically linked to how well his life is going, it’s just his feeling and determination in the moment. For all that bravado we see, we’re also shown the more human, relatable aspects. He’s amazing, brave and confident, but at the same time he’s still vulnerable and human.

Yet here’s the thing, I thought confidence meant a lack of vulnerability. I thought one couldn’t be both confident and vulnerable. This isn’t some segue into Boys Don’t Cry or a delve into masculinity. I didn’t believe that vulnerability wasn’t masculine, I just thought that vulnerability meant you had a long way to go before you were allowed to be confident.

(These lines go from bravado to insecurity in an instant, but I still think Tyler is confident as fuck)

I show what I feel to be the pretty vulnerable content on this blog. I write about my doubts and insecurities, the events that shaped me and the times in my life where I really felt at my lowest. I document the struggle I find myself in now, trying to carve something for myself and come to terms with the changes that keep happening around me. I don’t think anybody reading this would have an image of me as an outgoing, confident person. There’s rays of positivity sprinkled in occasionally but it’s generally content that I struggle to tell people in person.

Before starting this blog, I would have imagined that if I wanted to become this confident idealised version of myself, I’d need to erase any form of vulnerability. Delete the Instagram posts with moody lyrics, delete the couple shots and stop caring. I’d need to kill part of myself to become someone different. I couldn’t consciously accept that they were two signs of the same coin, even if I knew it in the back of my mind. The more I’ve been writing the better I’ve been feeling. These fears and insecurities being out in the open don’t make me any weaker, they actually feel like progress. My weaknesses will exist regardless of whether or not I tell people about them, my insecurities won’t disappear overnight. I’ll never be someone I’m not. What I can do is take these things that used to terrify me and put them out in the open. In my last piece I waxed on about making my words my own, by verbalising and bringing these thoughts into the open I feel like they become my own. They’re not completely stripped of power but they don’t hold the same sway over me that they once did.

So that leaves me with confidence. I can air my vulnerabilities and doubts but then where does my confidence come from? How do I then stop it from becoming arrogance?

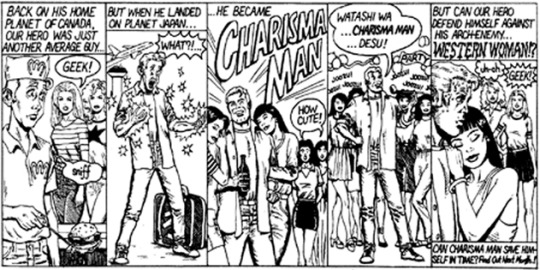

Let me tell you about Charisma Man.

You know how when Superman goes back to Krypton he’s just a regular person, but on Earth he’s basically a God? Charisma Man is a joke (turned comic) about how Western Men often believe themselves to be Superman on Earth when they move to Japan. Why? You’re basically bombarded with compliments from the get-go. You get told your Japanese is amazing (when it’s not), that you’re so tall (when you’re short back home) and that you’re such a handsome man (when all experiences up until now have led you to believe the opposite). Thus, you create a kind of false confidence for yourself. Or do the people around you do it for you? You yourself haven’t changed but the people around you have, and they’re whispering sweet nothings in your ear.

(Honestly didn't know it was a comic, initially heard of it on a subreddit making fun of other expats in Japan)

Hell, maybe I am good looking? I studied Japanese for a year back home, maybe I am just really good at it? Maybe those people around me back home were just obnoxiously tall and mean. Maybe I am the shit. You begin to formulate this new identity for yourself. You are Charisma Man now. You’ll be making heaps of money, have girls on standby and be loved by everybody in no time.

Except that never happens.

The reality of Charisma Man isn’t so bright. You’re probably an English teacher living somewhere far away from the big city. Your apartment is probably small and old and your salary is half as much as you were making back home. Despite being told about how good your Japanese is, you still can’t turn on the TV and watch a program. You still can’t go to the bank and open an account with your bilingual Japanese friend. You’re still single and you’re probably getting fatter off convenience store fried chicken, if anything.

It’s fake confidence with no merit, built on nothing. You haven’t put yourself out there or done anything to earn that confidence so it always feels foreign to you. There isn’t some feat you perform or some hurdle you cross to get that kind of confidence. You’re not smashing walls with your sledgehammer or confronting your fears and growing. You just get fed compliments until your confidence balloon bursts.

I felt like I was Charisma Man for a hot minute. Separated from everyone I knew, out drinking every night, being complimented left right and centre. I kept trying and failing to keep my feet on the ground. Back then I thought it was new-found confidence, but I wasn’t really coming out of my shell; I was just being obnoxious. After long the facade faded and I realised I was the exact same Elliot I was back in Australia, just with less money and a nicer haircut.

I began to think about my experience. Why was I so confident? Why did it dissipate so quickly? Why was I not the only one that experienced this little phenomenon?

I came to the conclusion that confidence can come from many places. It can come from other people, but then it’s reliant on the praise of others. It’s shallow, fickle and bound to dissipate sooner rather than later. You’re constantly reliant on the praise of others to affirm who you are as a person, you can fool people into giving you praise but that goes away before you know it as well.

It’s a big enough of a struggle to understand yourself, it’s near impossible to understand strangers. Relying on such an unstable form of validation is essentially just inviting mental trauma in the long run.

On the other hand, confidence can also come from within.

After I distanced myself from all that charisma, I began to realise that I felt my best and my most confident when I actually put the work in. I started properly studying, eating well, and writing down my thoughts. It didn’t matter as much if people didn’t say anything, because I went to bed every night knowing that I put in enough work. Nobody said anything about the change, but I felt like I was becoming my own biggest supporter.

It’s both rewarding and daunting when you switch dopamine suppliers. I used past tense in those last few sentences because that particular fountain hasn’t been flowing so well lately. The flip side of not letting other people’s compliments fuel you anymore is that when you’re not doing right by yourself, that confidence tend to dry up pretty quickly.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Punk’d History, Vol. VIII: This Machine [blank] Fascists

Photo by Richard Young

It has the appearance of a worrisome pattern: any number of punk rock’s founding figures embraced the symbolics of Nazi Germany. Ron Asheton, an original and indispensable member of the Stooges, played a number of gigs wearing a red swastika armband, and liked to sport Iron Cross medals and a Luftwaffe-style leather jacket. Sid Vicious loved his bright scarlet, swastika-emblazoned tee shirt, and Siouxsie Sioux, during her tenure as the It-Girl of the Bromley Contingent, mixed her breast-baring, black leather bondage gear with a bunch of “Nazi chic.” And how many early Ramones songs (inevitably penned by Dee Dee) referenced Nazi gear, concepts and geography? “Blitzkrieg Bop,” “Today Your Love, Tomorrow the World,” “Commando,” “It’s a Long Way Back to Germany,” “All’s Quiet on the Eastern Front,” and so on—for sure, more than a few.

youtube

“Appearance” is the key term. Poor Sid lacked the sobriety and smarts to have much of a grasp of fascism as an ideology. Siouxsie was just taking the piss, and gleefully pissing off the mid-1970s British general public, for much of whom World War II was still a living memory. Asheton and Dee Dee? Both were sons of hyper-masculine military men. Asheton’s father was a collector of WWII artefacts, and the guitarist shared his father’s fascination. When the Stooges adopted an ethos and aesthetic hostile to the late-1960s prevailing Flower Power rock’n’roll subculture, the Nazi accoutrement seemed to him fitting signs of the band’s anger and alienation. Dee Dee hated his father, an abusive Army officer who married a German woman. Dee Dee spent some of his youth in post-war West Germany, in which Nazi symbols were highly charged with anxiety and vituperation. Casual veneration of Nazis was a convenient way to reject the triumphal ennobling of the Good War, and of the military men associated with its traditions. And (as Sid, Siouxsie and Asheton also noticed) it really bothered the squares.

None of that makes the superficial use of the swastika or phrases like “Nazi schatzi” any less offensive — it simply underscores that in the cases noted above, the offense was the thing. The politics weren’t even an afterthought, because the political itself had been dismissed as corrupt, boring or simply the native territory of the very people the punks were striking out against. If that’s where the relation between punk and fascism ceased, there wouldn’t be much more to write about.

youtube

The post-punk moment in England provided opportunities to rethink and restrategize the nascent détournement of Siouxsie’s fashionable provocations. Genesis P-Orridge and the rest of Throbbing Gristle were a brainy bunch, and their play with fascist signifiers was a good deal more complex. The band’s logo and their occasional appearance in gun-metal grey uniforms clearly alluded to Nazism, with its attendant, keen interests in occult symbols and High Modernist representational languages. TG’s visual gestures were also of a piece with an early band slogan: “Industrial music for industrial people.” Clearly “industrial people” can be read as a highly ironized coupling: the oppressed workers marching through the bowels of Metropolis were a sort of industrial people, reduced to the functionality of pure human capital. TG seemed to impose the same analysis on the middle-managers of Britain’s post-industrial economy, and their uncritical complicity in capital’s cruelties. But it’s also possible to argue that industrial people are industrious people; like TG, industrial people (middle managers, MPs) can get a lot of stuff done. They can produce things. They can make the trains run on time. And what sorts of cargo might those trains be carrying? What variety of conveyance delivered the naked “little Jewish girl” of “Zyklon B Zombies” to her fate?

To be clear: I don’t mean at all to suggest that TG was a fascist band. Like their punky contemporaries, TG traded in fascist iconography in a spirit of transgressive outrage, expressing their hot indignation with equally heated symbols. And other British post-punk acts flirted with fascist themes and images, ranging from ambiguous dalliance (Joy Division’s overt references to Yehiel De-Nur’s House of Dolls and to Rudolph Hess; and just what was the inspiration for Death in June’s band name?) to more assertive satire (see Current 93’s appealingly bonkers Swastikas for Noddy [LAYLAH Antirecords, 1988]). But a more problematic populist undercurrent in British punk persisted through the late 1970s. The dissolution of Sham 69—due in large part to the National Front’s attempts to appropriate the band’s working-class anger as a form of white pride—opened the way for a clutch of clueless, cynical or outright racist Oi! bands to attempt to impose themselves as the face of blue-collar English punk. And literally so: the Strength through Oi! compilation LP (Decca Records, 1981) featured notorious British Movement activist Nicky Crane on its cover. It didn’t help that the record’s title seemed to allude to the Nazis’ “Strength through Joy [Kraft durch Freude]” propaganda initiative.

Of course, it’s unfair to tar all Oi! bands with an indiscriminate brush. A few bands whose songs were opportunistically stuck onto Strength through Oi! by the dullards at Decca Records — Cock Sparrer and the excellent Infa Riot — tended leftward in their politics, and were anything but racists. But for a lot of the disaffected kids sucking down pints of Bass and singing in the Shed at Stamford Bridge, it wasn’t much of a leap from the punk pathetique of the Toy Dolls to Skrewdriver’s poisonous palaver.

In the States, a similarly complicated story can be recovered:

youtube

In numerous ways, hardcore intensified punk’s confrontational qualities, musically and aesthetically. The New York hardcore scene made a fetish of its inherent violence, which complemented the music’s sharpened impact. So it’s hard to know precisely what to make of the photo on the cover of Victim in Pain (Rat Cage Records, 1984). If inflicting violence was an essential element of belonging in the NYHC scene, with whom to identify: the Nazi with the pistol, or the abject Ukrainian Jewish man, on his knees and about to tumble into the mass grave?

Agnostic Front seemed to provide a measure of clarity on the record, which included the song “Fascist Attitudes.” The lyric uses “fascist” as a condemnatory term. But the behaviors the song engages as evidence of fascism are intra-scene acts of violence: “Why should you go around bashing one another? […] / Learning how to respect each other is a must / So why start a war of anger, danger among us?” That’s a rhetoric familiar to anyone who participated in early-1980s hardcore; calls for scene unity were ubiquitous, and the theme is obsessively addressed on Victim in Pain. But the signs of inclusivity most visibly celebrated on the NYHC records and show flyers of the period were a skinhead’s white, shaven pate; black leather, steel-toe boots; and heavily muscled biceps. Those signifiers clearly link to the awful cover image of Strength through Oi! The forms of identity recognized and concretized in the songs’ first-person inclusive pronouns have a clear referent.

Agnostic Front wasn’t the only NYHC band to refer to and engage World War Two-period fascism. Queens natives Dave Rubenstein and Paul Bakija met at Forest Hills High School—the same school at which John Cummings (Johnny) befriended Thomas Erdelyi (Tommy), laying the groundwork for the formation of the Ramones. Rubenstein and Bakija also took stage names (Dave Insurgent and Paul Cripple) and formed Reagan Youth. But unlike the Ramones, there was nothing tentative or ambivalent about Reagan Youth’s politics. Rubenstein’s parents, after all, were Holocaust survivors. The band’s name riffed on “Hitler Youth,” but specifically did so to draw associations between Reagan and Hitler, between American conservatism’s 1980s resurgence and the Nazi’s hateful, genocidal agenda. Songs like “New Aryans” and “I Hate Hate” accommodated no uncertainties.

Still, it’s interesting that Victim in Pain and Reagan Youth’s Youth Anthems for the New Order (R Radical Records, 1984) were released only months apart, by bands in the same scene, sometimes sharing bills at CBGBs’ famous matinees of the period. And while Reagan Youth toured with Dead Kennedys, it’s Agnostic Front’s “Fascist Attitudes” that’s closer in content to the most famous punk rock putdown of Nazis.

youtube

It’s odd what comes back around: Martin Hannett, whom Biafra playfully chides at the track’s very beginning, produced much of Joy Division’s music, moving the band away from its brittle early sound to the fulsome atmospheres of the Factory records, and to a wider listenership. “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” similarly addresses a formerly obscure, tight scene opening to a greater array of participants, some of whom were attracted solely to hardcore’s reputation for violence. Like “Fascist Attitudes,” the Dead Kennedys’ song itemizes fighting at shows as its chief complaint, and as a principal marker for “Nazi” behavior. Biafra’s lyric eventually gets around to somewhat more focused ideological critique: “You still think swastikas look cool / The real Nazis run your schools / They’re coaches, businessmen, and cops / In a real fourth Reich, you’ll be the first to go.” The kiss-off to punk’s vapid romance of the swastika (it “looks cool”) complements the speculative treatment of a “real fourth Reich.” Both operate at the level of abstraction. The casual, superficial relation to the symbol’s aesthetic assumes a sort of safety from the real, material consequences of its application. And the emergence of a fascist political regime is dangled as a possible future event. That speculative futurity undoes the “real” in “real Nazis.” The threat is ultimately a metaphorical construct. The Nazis are metaphorical “Nazis.”

Still, it’s the song’s chorus that resonates most powerfully. So much so that the song has found its way into other artworks.

youtube

Jeremy Saulnier’s Green Room (2015) is frequently identified as a horror film on streaming services. We could split hairs over that genre marker. The film gets quite graphically bloody, but there’s no psychotic slasher killer, no supernatural force at work. And cinematically, the film is a lot more interested in anxiety and dramatic tension than it is in inspiring revulsion or disgust. It terrifies, more than it horrifies. What’s especially compelling about the film (aside from Imogen Poots’ excellent performance, and Patrick Stewart’s menacing turn as charismatic fascist Darcy Banks) is its interest in embedding the viewer in a social context in which the Nazis are a lot less metaphorical, a lot more real. In Green Room, the kids in the punk band the Ain’t Rights are warned about the club they have agreed to play: “It’s mostly boots and braces down there.” And they understand the terms. What they can’t quite imagine is a room — a scene, a political Real — in which fascism is dominant. Their recognition of the stakes of the Real comes too late. The violence is already in motion. In that world, the Dead Kennedys song provides a nice slogan, but symbolic action alone is entirely inadequate.

OK, sure, Green Room is a fiction. Its violence is necessarily aestheticized, distorted and hyperbolized. But perhaps the film’s most urgent source of horror can be located in its plausible connections to the social realities of our material, contemporary conjuncture. You don’t have to dig very deep into the Web to find thousands of records made by white nationalist and neo-fascist-allied bands, many, many of which deploy stylistic chops identified with punk rock and hardcore. You can listen. You can buy. (And yeah, I’m not going to link to any of that miserable shit, because fuck them. If you do your own digging to see what’s what, be careful. It’s scary and upsetting in there.) It feels endless. And the virulent sentiments expressed on those records are echoed in institutional politics in the US and elsewhere: Steve King (and now Marjorie Taylor Greene, effectively angling for her seat in Congress), Nigel Farage, Alternative für Deutschland, elected leadership in Poland and Hungary. Explicit white supremacist music also has somewhat more carefully coded counterparts in much more visible media (the nightly monologuing on Fox News) and in very well-positioned, prominent policy makers (Stephen Miller, who’s on the record touting “great replacement” theory and is a big fan of The Camp of the Saints). It’s a complex, ideologically coherent network, working industriously to impose and install its hateful vision as the dominant political Real.

Sometimes it feels as if no progress at all has been made. Maybe we’re moving toward the reactionaries. Contrast Skokie in the late 1970s with Charlottesville in 2017. And now if the Neo-Nazis have licenses for their long guns, they can strut through American streets wearing them in the name of “law and order.” It’s even more disturbing that a subculture that wants to clothe itself in “revolution” and “radicalism” is so tightly in league with institutional politics. Say what you will about Siouxsie’s Nazi-fashion antics, no one suspected that her prancing echoed political activity, policy-making or messaging in Westminster.

So what’s a punk to do? It’s certain that a vigorously free society needs to preserve spaces in which unpopular speech can be uttered and exchanged. Punk should pride itself on defending those spaces. But speech that operates in conjunction with an ascendant political power and ideological agenda doesn’t need defense or energetic attempts to preserve its right to existence. In October of 2020, that speech (in this case, speeches being written by Miller, texts by folks who have spent time in Tucker Carlson’s writer’s room and songs by white supremacist hardcore bands) has become synonymous with political right itself.