Text

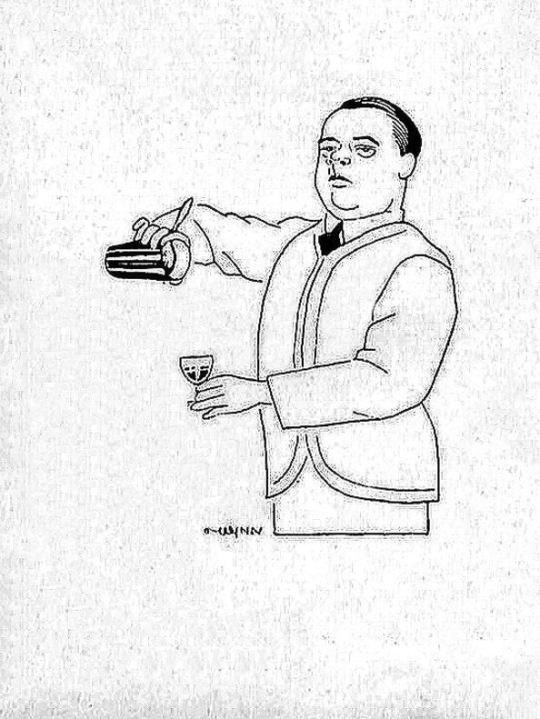

MONROE OWSLEY: No Good

An early 1930s fan magazine letter about Monroe Owsley reads like this: “He’s a slimy toad, a no-good rat up to trouble—and you feel he’s like that off-camera too!” The jury is likely permanently out on any off-camera sliminess, but Owsley was the center of many sordid rumors before his premature death in 1937 at age 36, when he supposedly had a heart attack after an automobile accident.

It was said around Hollywood that he was beset by drink, drugs, and gambling and that he had gay leanings and acted on them, though MGM starlet Anita Page said near the end of her life that he was in love with her in the mid-1930s. He was intensely in love with a lot of people, it seems, and furtive, and maybe a little wicked.

Whatever the cause of his messy private life, Owsley was a memorably odious man in Pre-Code cinema, and Bette Davis, who sparred with him in Ex-Lady (1933), called him “marvelously corrupt” in her memoirs. With his high forehead and large ears, his long nose and narrow eyes, and his tendency to bear down on others to shout and sneer, Owsley is as resolutely unappealing as anyone has ever been in movies.

Owsley was born in Atlanta, Georgia, and his mother was an actress, Gertrude Owsley. He took acting classes as a teenager and started appearing on Broadway in the 1920s before his film debut in The First Kiss (1928), where he was “the other suitor” to Fay Wray. Owsley got typecast after playing the part of the alcoholic brother Ned in the first film version of Philip Barry’s play Holiday (1930). In the better-known 1938 remake of Holiday starring Katharine Hepburn, Ned is played by Lew Ayres as dissolute but still very beautiful and poetic, whereas Owsley is a sour, nasty character barely able to contain his disgust with himself and his life. “We don’t need any saints in this family,” he tells his sister Julia (Mary Astor) when she is talking up her fiancé Johnny Case (Robert Ames). He has a real flair for ratty maliciousness here, for vitriol, and for heavy self-pity.

Owsley was a weak and caddish boyfriend and then husband to Barbara Stanwyck in Ten Cents a Dance (1931), confirming everything Stanwyck seemed to know about men whenever she looked them over. He throws a really pitiful little punch when trying to defend Stanwyck at her dime-a-dance job, so that she has to step in and give the guy who’s bothering them a real smack herself.

Owsley reveals his rodent-like little smile for the first time in Ten Cents a Dance, flashing his small teeth in a way to set your own teeth on edge. A gambler and a sponger, a snob and a complainer and a thief, he torments Stanwyck with his meanness and lack of quality until she finally shouts at him, “I don’t love you! I don’t even think enough of you now to hate you!” and then, “You’re not a man….you’re not even a good sample.”

Owsley pursued Claudette Colbert in his first scenes in Honor Among Lovers (1931), and he couldn’t stop his face from sending weird, resentful signals. Colbert marries him, and wouldn’t you know, it turns out he’s a worthless no-good cad, a drunk, a skirt-chaser, and a thief, nearly making Fredric March’s sexual harasser boss to Colbert look somewhat better if only by comparison.

“You haven’t even got sense enough to stay sober!” Colbert cries as their troubles mount in Honor Among Lovers, which makes Owsley get maudlin; he is particularly gross in his movies when he descends to contrite boyhood and expects his women to mother him. He winds up shooting March and snivels that he didn’t mean to do it right afterward, and then he tries to pin the blame on Colbert. A real winner!

In Indiscreet (1931), Owsley wore a mustache, as if he needed to look even more villainous. Gloria Swanson breaks up with him in the first scene because of his philandering, and so naturally he takes up with her sister, and this is supposed to be a comedy, so Owsley plays in a more comic key here, but not by much. “You’re not bad,” Swanson finally tells him. “You’re just not very bright.” Owsley was a drunken playboy pursuing a blond Joan Crawford in This Modern Age (1931), a Robert Montgomery role that he makes as unattractive as possible.

In the Clara Bow vehicle Call Her Savage (1932), Owsley was Larry Crosby, “one of the worst characters in Chicago.” He knocks girlfriend Thelma Todd down after breaking up with her, but she tells him, “You’ll come back…I understand your little…peculiarities.” Does she mean S&M? Homosexual proclivities? “I doubt there’s any sin in the calendar I haven’t been guilty of,” he tells Bow, who responds to his creepiness with peppy non-sequiturs. He spends their wedding night out on the town and abandons Bow, tossing some money at her. She visits him down in New Orleans, where he seems to be suffering from syphilis, and he physically attacks her, trying to strangle her, before she hits him over the head with a small wooden stepstool.

Owsley wore a mustache again to blackmail Kay Francis in The Keyhole (1933), and then he pursued Davis in Ex-Lady, where she told him, “Don’t be so persistent…it’s annoying,” and then, “Man… I’m souring on the lot of you!” Resentful of her boyfriend (Gene Raymond) seeing another women, Davis briefly succumbs to Owsley’s advances, flinging herself down on the floor to be kissed by him while drums beat from a bandstand nearby, a sure signal of a self-destructive impulse.

“Ya look pretty good to me,” Mae West tells Owsley in Goin’ to Town (1935), and this shows the great Mae’s imagination and generosity, for Owsley here is a sweaty, drunken, suicidal gambler with lines under his eyes set to marry her for her money (he will provide his family name). He was right at home with all the drinking in James Whale’s Remember Last Night? (1935), but the Production Code had by then put a cramp in his caddish style.

Owsley wound up making a movie with Martha Raye called Hideaway Girl (1936) and a last film at Republic Pictures, a musical called The Hit Parade (1937), before his death, which was a bit mysterious and had people in town talking. “Where does everybody finish?” Owsley asks Ann Harding in Holiday. “You die…And that’s all right, too.”

by Dan Callahan

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Racial Justice Vs. The Israel Lobby: When Being Pro-Palestine Becomes the New Normal

There is an unmistakable shift in American politics regarding Palestine and Israel, a change that is inspired by the way in which many Americans, especially the youth, view the Palestinian struggle and the Israeli occupation. While this shift is yet to translate into tangibly diminishing Israel’s stronghold over the US Congress, it promises to be of great consequence in the coming years.

Recent events at the US House of Representatives clearly demonstrate this unprecedented reality. On September 21, Democratic lawmakers successfully rejected a caveat that proposes to give Israel $1 billion in military funding as part of a broader spending bill, after objections from several progressive Congress members. The money was specifically destined to fund the purchase of new batteries and interceptors for Israel’s Iron Dome missile defense system.

Two days later, the funding of the Iron Dome was reintroduced and, this time, it has successfully, and overwhelmingly, passed with a vote of 420 to 9, despite passionate pleas by Palestinian-American Representative, Rashida Tlaib.

In the second vote, only eight Democrats opposed the measure. The ninth opposing vote was cast by a member of the Republican party, Thomas Massie of Kentucky.

Though she was one of the voices that blocked the funding measure on September 21, Democratic Representative, Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, switched her vote at the very last minute to “present”, creating confusion and generating anger among her supporters.

As for Massie, his defiance of the Republican consensus generated him the title of “Antisemite of the Week” by a notorious pro-Israel organization called ‘Stop Antisemitism’.

Despite the outcome of the tussle, the fact that such an episode has even taken place in Congress was a historic event requiring much reflection. It means that speaking out against the Israeli occupation of Palestine is no longer taboo among elected US politicians.

Once upon a time, speaking out against Israel in Congress generated a massive and well-organized backlash from the pro-Israeli lobby, especially the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), that, in the past, ended promising political careers, even those of veteran politicians. A combination of media smear tactics, support of rivals and outright threats often sealed the fate of the few dissenting Congress members.

While AIPAC and its sister organizations continue to follow the same old tactic, the overall strategy is hardly as effective as it once was. Members of the Squad, young Representatives who often speak out against Israel and in support of Palestine, were introduced to the 2019 Congress. With a few exceptions, they remained largely consistent in their position in support of Palestinian rights and, despite intense efforts by the Israeli lobby, they were all reelected in 2020. The historic lesson here is that being critical of Israel in the US Congress is no longer a guarantor of a decisive electoral defeat; on the contrary, in some instances, it is quite the opposite.

The fact that 420 members of the House voted to provide Israel with additional funds - to be added to the annual funds of $3.8 billion - reflects the same unfortunate reality of old, that, thanks to the relentless biased corporate media coverage, most American constituencies continue to support Israel.

However, the loosening grip of the lobby over the US Congress offers unique opportunities for the pro-Palestinian constituencies to finally place pressure on their Representatives, demanding accountability and balance. These opportunities are not only created by new, youthful voices in America’s democratic institutions, but by the rapidly shifting public opinion, as well.

For decades, the vast majority of Americans supported Israel. The reasons behind this support varied, depending on the political framing as communicated by US officials and media. Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, for example, Tel Aviv was viewed as a stalwart ally of Washington against Communism. In later years, new narratives were fabricated to maintain Israel’s positive image in the eyes of ordinary Americans. The US so-called ‘war on terror’, declared in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks, for example, positioned Israel as an American ally against ‘Islamic extremism’, painting resisting Palestinians as ‘terrorists’, thus giving the Israeli occupation of Palestine a moral facade.

However, new factors have destabilized this paradigm. One is the fact that support for Israel has become a divisive issue in the US’ increasingly tumultuous and combative politics, where most Republicans support Israel and most Democrats don’t.

Moreover, as racial justice has grown to become one of the most defining and emotive subjects in American politics, many Americans began seeing the Palestinian struggle against the Israeli occupation from the prism of millions of Americans’ own fight for racial equality. The fact that the social media hashtag #PalestinianLivesMatter continues to trend daily alongside the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter speaks of a success story where communal solidarity and intersectionality have prevailed over selfish politics, where only money matters.

Millions of young Americans now see the struggle in Palestine as integral to the anti-racist fight in America; no amount of pro-Israeli lobbying in Congress can possibly shift this unmistakable trend. There are plenty of numbers that attest to these claims. One of many examples is the University of Maryland’s public opinion poll in July, which showed that more than half of polled Americans disapproved of President Joe Biden’s handling of the Israeli war on Gaza in May 2021, believing that he could have done more to stop the Israeli aggression.

Of course, courageous US politicians dared to speak out against Israel in the past. However, there is a marked difference between previous generations and the current one. In American politics today, there are politicians who are elected because of their strong stance for Palestine and, by deviating from their election promises, they risk the ire of the growing pro-Palestine constituency throughout the country. This changing reality is finally making it possible to nurture and sustain pro-Palestinian presence in US Congress.

In other words, speaking out for Palestine in America is no longer a charitable and rare occurrence. As the future will surely reveal, it is the “politically correct” thing to do.

by Ramzy Baroud

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mars

George Ellery Hale, The Planet Mars, 60-inch Reflector, Mount Wilson, 1909

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Babs

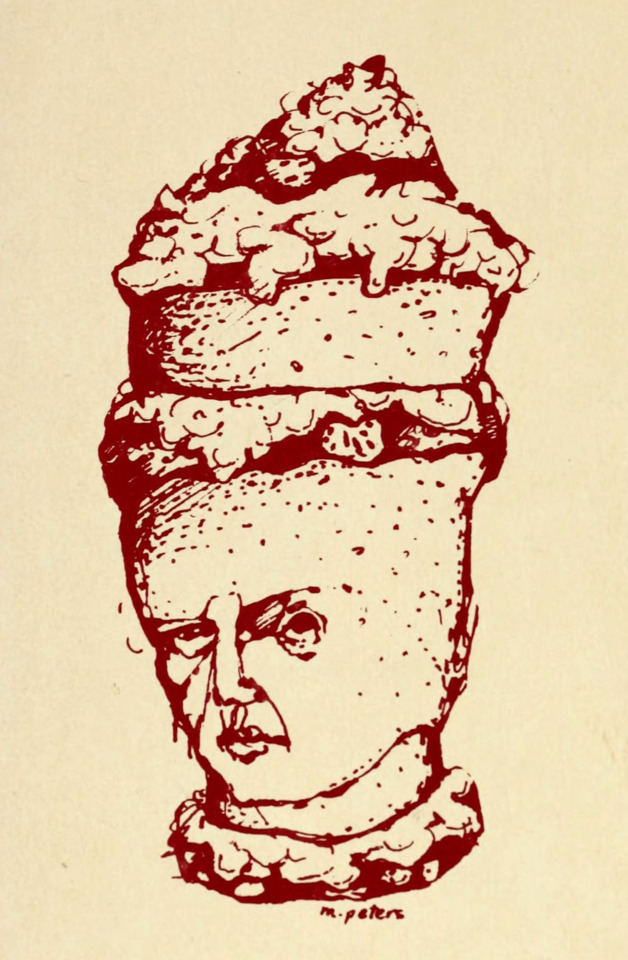

By the Sixties new waves were crashing everywhere. The frisson of La Nouvelle Vague should be understood in a tempest of plurality that shook Hollywood, whose producers, trained in the relative stasis of studio-system majesty, were being tossed willy-nilly on the backs of Italian, British and German breakers. And, emerging from this unpredicted deluge of international currents, spawning endlessly exploitive countercurrents, came Barbara Steele, a castaway or, as she herself puts it, “an unwilling immigrant” in the heart of Hollywood-land where she unhappily resides today. More than six decades have passed since she played an avenging witch in Black Sunday, but no matter how stubbornly Steele refuses to claim her title as Italy’s reigning Scream Queen, the aura of dry ice and stage blood lingers in the cinematic unconscious, trailing her in gory wreaths. She remains a prisoner of her proudest memory, Fellini’s Otto e Mezzo, compared to which her genre horror films — The Long Hair of Death, An Angel for Satan, Terror Creatures from Beyond the Grave — essentially amount to the gothic flop house of cinema history. Or so the self-tormenting diva chooses to believe. The Italians would dragoon her immaculately virgin-white screen image, from England’s ashen shores to their own sun-kissed and suggestive peninsula.

From whence Barbara Steele’s stolen likeness, now the ultimate (cosmic) femme fatale, would commence irradiating Southern peasants with previously unknown iconographic power. Steele, in other words, weaponized what Mario Bava and Riccardo Freda had bestowed upon her as the greatest, and most acquisitive, directors of Italian genre horror: that exalted say-so reserved for goddesses. Black Sunday will never be classified as “New Wave”, nor will Georges Franju's Eyes Without a Face. Nor will any category of filmmaking moored to genre (whether it be horror, science-fiction or le cinéma fantastique) gain admittance to the brick-and-mortar Canon, whose location and visiting hours remain the jealously guarded secrets of custodial film critters. And while I don’t begrudge Cahiers du Cinéma its fun concocting nomenclature, I do prefer celebrating the 1960s for its intrinsically unnamable dissonance.

Making her Italian screen debut in Black Sunday in August 1960, Barbara Steele glowered into Mario Bava’s lens, and at that pivotal moment in cinema’s manic history something shone forth so ancient that even the most devout heretic experienced inchoate shivers of remorse. The mod summertime of the new decade was arrested, plunged backward, whereupon a strange, atavistic transformation occurred: the audience, pious enough to register shock at the intended effects, was nevertheless unprepared to confront the triumph of alchemy and necromancy over mere sackcloth and ashes. Shamefaced in the dark like Catholic schoolchildren remembering all they had been taught, the audience stared back at Steele’s eyes — a pair of druid’s eggs, bestowing true and everlasting illumination, as opposed to religion’s metaphorical kind — and shuddered inwardly at things no mere mortal could comprehend.

by Daniel Riccuito

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Putzi

In Hitler’s inner circle of thugs, lunatics, imbeciles and perverts, Ernst Franz Sedgwick Hanfstaengl stood out as an oddity among the oddballs. Where they tended to be snarlingly parochial bumpkins, he was a cosmopolitan man – a Harvard man – with an international set of high-placed friends and associates that included not only Adolf Hitler but Franklin Roosevelt. It wasn’t that he didn’t look the part of the Aryan goon. He stood a mountainous six foot four, with broad shoulders, a barrel chest, huge hands, and a boulder of a head with a lantern jaw and lidded eyes designed for the threatening glower. But he was a big man who only wanted to be liked, aggressively ingratiating as a golden retriever. He was universally known by his childhood nickname, Putzi.

Putzi was born into a prosperous and cultured home in Munich in 1887. His German father was well-known dealer in fine art reproductions, with galleries in London and on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. His mother was an American of fine New England pedigree, with a Civil War general in her family tree. They sent him to Harvard in 1905. In 1911, at 24, he moved to Manhattan to run Galerie Hanfstaengl at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 45th Street. Yet his first love was music. He was an accomplished pianist if a sometimes overenthusiastic one who, it was said, occasionally banged the keys so hard with his sledgehammer hands that he broke strings. Many mornings before opening the gallery he could be found at the Harvard Club around the corner, playing the piano there. That was where he met another grad, state senator Franklin Roosevelt, who breakfasted at the club. Putzi was an assiduous cultivator of the celebrated and influential; he’d later write that “the famous names who visited me” at his gallery “were legion,” including “Pierpont Morgan, Toscanini, Henry Ford, Caruso, [the aviator Alberto] Santos-Dumont, Charlie Chaplin, Paderewski, and a daughter of President Wilson.” He also made friends with the artists and writers in Greenwich Village, including an affair with Djuna Barnes.

The coming of the Great War made life very difficult for him in New York, as it did for many German-Americans. The Justice Department investigated him; his Harvard Club fellows turned cold; the gallery’s windows were smashed more than once; and then, toward the end of the war, the government seized the gallery as “enemy property” and auctioned it off for a pittance.

In 1921 he returned to Munich with his wife and infant son. The following year, a Harvard classmate at the American embassy asked Putzi to go hear a political speech and give his impression. The speaker was Adolf Hitler, and Putzi was definitely impressed. He immediately ingratiated himself with Hitler, becoming his constant companion, his court minstrel and court jester. He saw his role as introducing some culture and refinement to Hitler and his loutish crew. He played Wagner and Liszt to soothe Hitler’s nerves, and tried to get him to grow out his moustache, which Putzi called his “snot-catcher.” He provided Hitler an entrée to upper-crust Germans and their money, and personally footed the bill for expanding the Nazi newspaper Völkischer Beobachter from a thin weekly to a thriving daily.

On November 8, 1923 he was inside Munich’s Bürgerbräu Keller when Hitler launched his failed putsch. Escaping the chaos of the next day, Hitler fled to Putzi’s country home some 40 miles south of the city. The American journalist Dorothy Thompson, who knew Putzi, showed up, pursuing a rumor that Hitler was hiding out there, but the police had gotten there first. “HITLER SEIZED NEAR MUNICH,” the front page of the November 13 New YorkTimes reported. “Found in Home of E. F. Hanfstaengl, Ex-New York Art Dealer.” [November 13, 1923]

Putzi maintained loose ties with the Nazis during their low ebb in the 1920s; then, when Hitler’s fortunes seemed to be reviving in 1931, Putzi re-hitched his wagon, joining the party – a commitment he’d resisted until then – and convincing Hitler to let him be his foreign press spokesman. He certainly had the international press contacts, from Thompson to Quentin Reynolds to William Randolph Hearst, though Thompson would dismiss him as “an immense, high-strung, incoherent clown,” and Reynolds sneered, “You had to know Putzi to really dislike him.”

One evening in 1935 another Harvard man, the New York writer Varian Fry, stepped out of his hotel in Berlin to witness “a band of some 200 Nazis, clad in civilian clothing but many of them wearing Storm Troop boots and trousers,” surge along the fashionable Kurfürstendamm, attacking anyone they thought was Jewish. They yanked people out of cars and cafes to beat and kick them senseless. They smashed the windows of Jewish shops and restaurants, as they sang the “Horst Wessel” song and chanted anti-Semitic slogans. Fry saw one young man “whose eyes became filled with blood so that he could not see where he was running,” and the Jewish proprietor of an ice cream shop badly beaten as his shop was wrecked. Fry returned to his hotel room, telephoned his report to a wire service, and the next day it was in the Times and other newspapers.

The Völkischer Beobachter, unsurprisingly, blamed Jews for inciting what it described as the spontaneous disturbance Fry witnessed, supposedly outraging good Germans by hissing at an anti-Semitic Swedish film in a Kurfürstendamm theater. To Fry, the riot “gave every evidence of careful planning” and was clearly led by storm troopers. The morning after, he went to Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda for some answers, and was ushered into Putzi Hanfstaengl’s office. At first Putzi went into boola-boola overdrive, one Harvard man to another, but when Fry resisted, Putzi deflated. Apparently he was finding his job of explaining the Nazis to the world rather daunting and frustrating. He was remarkably, even recklessly candid with Fry. He confessed that it was most likely storm troopers who had hissed at the Swedish film as a pretext for the rioting. More amazing still, he told Fry that two factions in the Nazi Party leadership were arguing over how to deal with Germany’s Jews. The moderates, in which he counted himself, maintained that the answer was to segregate or send them all away, perhaps to Madagascar. The radicals, who he said included Hitler and Goebbels, preferred exterminating them. Fry reported this conversation to the Times as well, seven years before the Nazi hierarchy formally adopted the Final Solution.

Putzi grew increasingly uncomfortable with making excuses for Hitler over the next couple of years. By 1937, Hitler and his inner circle harbored doubts about his loyalty. Fearing that Hitler planned to liquidate him, Putzi fled Germany for England, where he was hoping to be embraced as a political exile. Instead, the British interned him as an enemy national.

In 1942, Roosevelt took pity on him. He arranged with the British to have him transferred from a POW camp in Canada, which was reducing Putzi to a miserable sliver of his jolly old self, to a house outside Washington. There, under house arrest and constant guard, Putzi was kept busy writing voluminous psychological profiles of Hitler and other Nazi leaders for possible use by American intelligence and propaganda services. For a while his guard was his own son, Sergeant Egon Hanfstaengl, who had also fled Germany, come to America, and enlisted in the U.S. Army.

After the war Putzi was allowed to return to Germany, where he submitted to the humiliating process of being “de-Nazified.” He spent the rest of his life trying to convince anyone who’d pay attention that he’d been a “victim of Nazi political persecution,” even asking for cash reparations from the German government. In 1974 he made the news again when he was allowed to return to Harvard for his 65th class reunion. He died the following year.

by John Strausbaugh

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trauma-Toons

A shortish documentary called Cartoon College, directed by Josh Melrod and Tara Wray, celebrating the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont, left me thinking about a bunch related or semi-related things. The (unaccredited) Center offers a two-year course leading to a Master of Fine Arts in cartooning.

First of all, is such a curriculum necessary? In the applied-arts sense, probably not really, but as a supportive place for artists doing something that, the film proclaims, society at best ignores, or at worst sneers at, it shines. Kids and adults – including a man in his late 60s – act as though they are finally being allowed to crawl out from under the carpet.

Which by the end made me uneasy. The presumably self-selecting group projects a stereotype of cartoonists as universally depressed dweebs with godawful childhoods – salvaged suicides or serial killers in waiting. Somehow, I can’t believe this is a broadly accurate cross-section of those involved in an admittedly wacky profession.

Which then led me to recall how much the newspaper comics meant to me growing up, and to a lot of kids of that era. And it wasn’t just kids reading the “funnies”; consider the sophistication and orientation of “Winnie Winkle,” “Brenda Star,” “Rex Morgan” – these were works written with an adult audience first and foremost in mind.

They were the static YouTube of the time, and their hold on me has never relaxed. Will Eisner and his seven-page Sunday adventure "The Spirit" were the highlight of my week. In the ‘70s, Eisner’s boundary-breaking foray into the “graphic novel” made my liver quiver.

Try reading bio-bits by and about Eisner and his studio (which produced Jules Feiffer and Wally Wood among many others), and you don’t come away with the idea that the comics artists of the '40s and '50s worried much about making a living, what their work “meant” or whether it reflected their traumatic youth – even though many of them went totally unrecognized. Carl Barks, who drew the iconic Scrooge McDuck comic books, was not identified as their author until after he retired, all original credit going to Walt Disney, whose talent was business and hype, not drawing.

I’ve always taken cartoonists seriously, in a way that, I think, Eisner did. They aren’t little laugh generators snickering off to the side, but unleashers of big guffaws at what society is and does, as were Rowlandson and the political cartoonists of the 19th century. But somehow, along about “Superman,” we began to separate “serious” words from “frivolous” pictures in published art – a highbrow-lowbrow division and a reversal of the Renaissance, when painting and drawing ruled as the ultimate expressions of what the artistic mind could produce.

The aspiring artists at the Center for Cartoon Studies see cartooning as a particularly personal form of expression, neither social commentary nor kiddie trifles, but the key to the release of their inner demons (or at least their under-the-bed monsters). Yet they fear, one and all, that they will forever be viewed as warped outsiders.

I don’t think that’s anywhere near true in the wider world. But then, we’re very confused these days in how we approach art: We don’t know how to look at it, don’t have any definition of what art is. We don’t need academic definitions, certainly, but we do need social definitions. These were assumed in past ages but are now fluctuating and scattered.

Science fiction author J.G. Ballard foresaw this social-aesthetic removal in his Vermillion Sands stories, where art of the future becomes something we cannot keep hold of. In the half-mad art conclave of Vermillion Sands, statues whisper meaningless phrases and poetry floats on the breeze, not because it’s all ephemeral, but because no one can pin down what it might or should proclaim.

Graphic novels and higher comic book prices, better digital graphics programs and Art Spiegelman’s Maus have together given comics a more upscale image while removing them from their common ground. That holds largely true of most public art. Is this a wonderful thing – art set free from relevance, to be whatever we say (or fail to say) it is? Or have we sliced it off from life, made it an "other,“ a separate thing to worship like modern religion (or laugh at, given your inclination), to appreciate without underlying humanity?

by Derek Davis

3 notes

·

View notes