#Roman colonialism

Text

#the maccabees#israeli#israel#secular-jew#jewish#judaism#jerusalem#diaspora#secular jew#secularjew#islam#Simon maccabeus#judea#Samaria#antisemitism#roman empire#Rome#Roman colonialism#colonialism

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen Zenobia's last look upon Palmyra by Herbert Gustave Schmalz

#herbert gustave schmalz#art#zenobia#palmyra#empress#queen#septimia zenobia#palmyrene empire#syria#romans#roman#colony#aurelian#history#ancient#architecture

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Genuinely confused as to how so much of the fandom watched the first 2 CR campaigns and Calamity and yet still ended up in a “Ludinus is right let’s kill all the gods” position. Like it’s baffling to me how much content/context people have just decided to completely forget? We had 2 full campaigns of very positive interactions with the gods and the moment there’s some hypothetical and interesting musing and speculation about their roles in the world from a more disconnected place we’re just throwing that out the window?*

Tbh the number of people who watched episode 4 of Calamity and still saw Asmodeus as sympathetic or having a legitimate point is unsettling to me, but while that’s a related issue it’s not quite the same conversation.

But like legitimately how did we so quickly make a hard turn from “The Stormlord teaches his barbarians to use the power of friendship, he’s a funny kindergarten teacher” memes to…this.

*(This is not, btw a comment on the characters having philosophical debates in-world because I think those are interesting and on-theme for the campaign and are also nearly always concluding with “our personal relationship to individual gods and feelings about them are irrelevant actually, the people trying to destroy them are doing wider harm and are in the wrong and must be stopped.” I’m actually loving the engagement with this by the characters in-universe but the fandom is exhausting me.)

#people stop engaging with all fantasy religion like it’s the same as bigoted evangelical American Christianity challenge#oh also the ‘the gods are colonial invaders’ take is also super weird to me because that’s applying recent human history to what is#basically standard like Greek or Roman creation myth?#like a ton of European pagan lore has a ‘the gods we worship came from afar and tamed the wilds of nature’ narrative#it is a metaphor#cr discourse#legit saw someone this morning confidently posting ‘well Ludinus just is right though!’ and I wanted to close down the whole internet#critical role

574 notes

·

View notes

Text

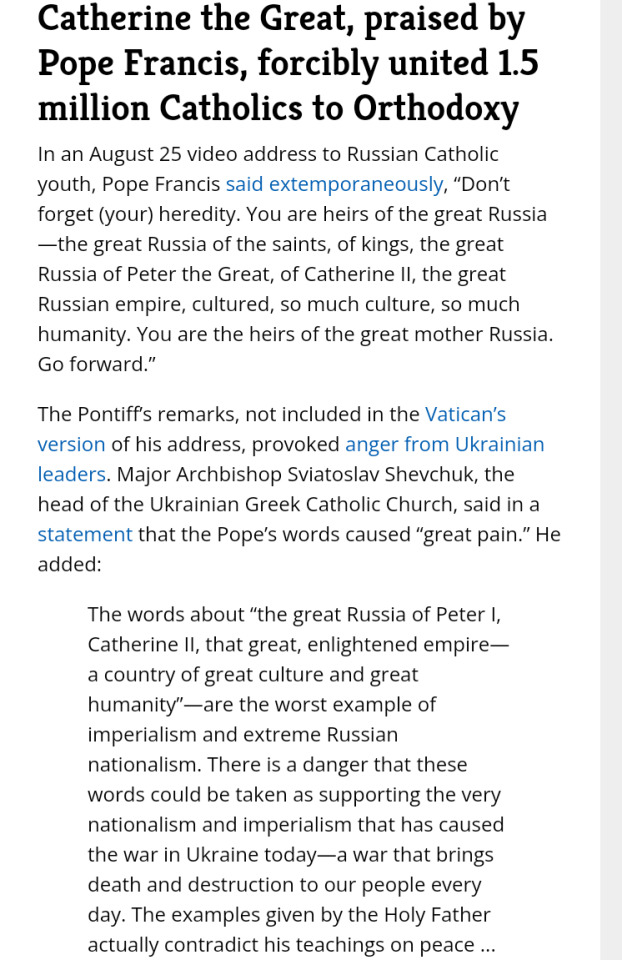

anyway, Pope Francis is dumb as hell, he praises Russia's anti-Catholic, barbaric history.

russians: persecute catholics and destroy their country (e.g. after they invaded poland, they closed many roman catholic churches and turned them into orthodox churches, they did not allow people to build catholic churches, they persecuted priests, they hanged many priests who were against russian occupation, Tsarina Catherine personally forbade any contact with Rome, Nicholas I closed many monasteries, churches in poland (1832), he stole their property (1842), he sent many priests to forced labour, e.g. they sent many to Siberia for hard labor, + they especially hated and persecuted greek catholics/byzantine rite catholics)

Pope Francis: what a wonderful legacy 😍

.

.

.

🤡...

#pope francis#anti imperialism#anti colonialism#christianity#roman catholic#politics#vatican#catholic#catholicism#poland#catherine the great#greek catholic#catherine ii#imperial russia#leftblr#roman catholicism#stand with ukraine#russian imperialism#russian war on ukraine#byzantine catholic

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

More notes on the development of Roman imperialism and colonialism:

Rome began as a city warring with other cities and city-states in Italy. Its growth was haphazard and, in some ways, accidental. They don't seem to have thought of it as an "empire" in the sense of "our land and sea," until the 1st century BCE.

Before then, the Roman empire was characterized by active military control, not by thinking of lands as "Roman territory." This was not the USA trying to grab all the land it could in manifest destiny; this was a city-state that primarily aimed to enrich and defend itself, and often used military occupation to do so.

The Romans did not like to think of themselves as an expansionist power, but as fighting defensive wars for themselves and their allies. However, the Roman system of alliance building - and sometimes provoking other countries - frequently "pulled" Rome into wars anyway. And Roman generals who really wanted a war could often invent justifications for it. Caesar's conquest of Gaul is one of many wars that started as "protecting an ally from invasion" but which soon became opportunistic power-grabs.

Even so, this self-concept as "defenders" partly explains why the Romans mostly left defeated Italian communities intact, only demanding troop levies and sometimes confiscating part of the land. Draining conquered peoples dry or wiping them out was not the goal, and the Romans actually prided themselves on being relatively "merciful" to their neighbors (by classical standards). However, as Rome's sphere of influence grew, and the distance from Rome to defeated (and potentially rebellious) communities increased, they began stationing permanent military outposts in certain regions.

Roman colonies originated as military outposts. They served a quadruple purpose: 1) to punish communities that had rebelled or fought wars against Rome; 2) to reward Roman veterans; 3) to relieve economic tensions in Rome itself; and 4) to suppress further rebellion by maintaining Roman outposts in the region.

This is in contrast to Greek and Phoenician colonies, which were usually established by traders, and the USA's westward expansion, which aimed to replace indigenous peoples en masse.

Similarly, the word "province" originally referred to a task or assignment, not a geographic area. A proconsul might be assigned the "province" of Spain of Sicily in the sense of "keep this region from revolting."

Economic exploitation came later. The Punic Wars marked a turning point in which Rome stationed generals overseas for extended periods of time to prevent insurgency among subject peoples, not Italian allies who were acknowledged as mostly self-governing. These generals had immense latitude to do as they saw fit, and with the promise of armed protection, Roman businessmen soon saw opportunities for mining, slave plantations, and more. This is also why Spain, Sicily, and certain other regions were abused much more harshly than Italy itself.

In the 1st century BCE we see a slow shift toward conquest of lands being sought for its own sake, rather than as a by-product of war. By the reign of Augustus, writers imagined Rome conquering the whole world.

Julius Caesar's conquest of Gaul occurred midway through this ideological shift. Hence he felt the need to justify his conquest by presenting his side of the story in his Commentaries, but the public response to his needless invasion of Britain was overwhelmingly positive. Conquest, if successful, was beginning to justify itself.

However, the Romans also gradually came to see themselves as responsible for the government of long-term provinces, and take measures to curb abuse of provincials. Caesar himself installed one of the biggest reforms limiting corruption. (Yes, he was a bit of a hypocrite...)

The gradual expansion of citizenship across the empire and military recruitment from provincials gradually put pressure on the Romans to value more than just Italian interests. We first see this with Julius Caesar's attempt to extend Latin Rights to Sicily and citizenship to Cisalpine Gauls; it reached its final form when the Edit of Caracalla made all free inhabitants of the empire citizens in 212 CE. The "Romanization" of Europe did not happen by displacing the original inhabitants of provinces, but by incorporating them.

Sources: SPQR by Mary Beard; A Companion to the Roman Republic, ed. Rosenstein and Morstein-Marx, chapters 6-7. See also my previous post on this topic.

#jlrrt reads#a companion to the roman republic#nathan rosenstein#robert morstein-marx#colonialism#imperialism#there were some cases of mass displacement and genocide btw. but at the risk of hair-splitting: these occurred as part of wars#rather than as the goal of roman colonialism per se#jlrrt essays

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

Where were the Palestinian Arabs during the Jewish-Roman wars and which side did they fight for?

They did not exist. There was no Palestinian identity for anyone during that time period. Most Arabs were still in the peninsula and had not reached the Levant in large numbers, and they were divided tribally, without a shared language or religion. The Roman Empire colonized ancient Syria and Egypt when they weren't majority Arab, and had only a limited presence on the peninsula.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the funniest historical facts for holytalia is HRE trying to be discreet about his crush and then just call his first colony “Little Venice 🥰🥰”

Random politician: “U little brat, we are in war with that dude”

HRE: “But God said to love your enemies”

#Tw joke about colonialism#hetalia#hws italy#hws veneziano#aph italy#hws north italy#hws hre#aph hre#hws holy roman empire#aph holy roman empire#aph north italy#holitalia#holytalia#Love to my Venezuelan friends

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the forgotten tales of Magna Graecia that helped shape this captivating Mediterranean region, ancient Greek colonies thrived amidst battles, innovations, and a cultural fusion echoing through time.

Faced with overpopulation, Greece sent out settlers, leading to a strategy of colonization driven by necessity. These independent city-states rose to power, only to engage in fierce wars among themselves. The cultural fusion of Magna Graecia became a melting pot where Greek traditions intertwined with the essence of indigenous Italy, seen in artistic, architectural, and philosophical marvels that emerged from this dynamic interplay and left an indelible mark on the Mediterranean landscape.

From the dawn of Greek colonization to the clash with the mighty Roman Empire, Magna Graecia's epic journey, revealing a rich tapestry of battles, alliances, and a unique cultural synthesis, continues to resonate in the vibrant towns and cities of this historically rich region.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Washington DC metro is, I assume, what it would look like if a swarm of giant bees built a particle accelerator in the brutalist architectural style.

#brutalism is remarkably popular in dc#after fake greco-roman nonsense but before fake colonial nonsense#why are the subway stations so damn dark?#washington dc#liveblogging the last day of my vacation

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

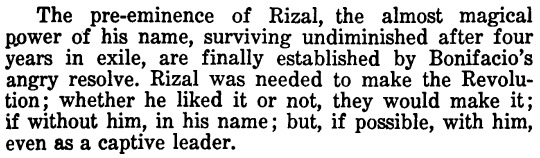

THE WEIGHT OF A NAME

The First Filipino: A Biography of Jose Rizal, Leon Ma. Guerrero • Brutus, the Noble Conspirator, Kathryn Tempest

#jose rizal#marcus junius brutus#gaius cassius longinus#dead romans club#ph rev#colonial era ph#comparatives tag#i feel so fine and so so so normal about this#(head in hands) thinking about. the ultimate failures of both events. im fine. this is fine

65 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Though Cleopatra was born—and apparently thought of herself as—a Macedonia Greek, all that mattered to her Roman contemporaries was that she was not a Roman and, more important, that her existence, her influence, and her power constituted an obstacle to Roman expansion. She was a force to be destroyed or encouraged to destroy herself so that the empire could prevail. Her gender, her exoticized "Easternness," and her determination to protect her country's autonomy helped explain why Egypt was thought to need the moral, political and practical guidance of Rome—and why Cleopatra did in fact need the support and allegiance of Mark Antony and Julius Caesar.

It is hard not to notice how profoundly her gender determined the way in which her story has been told. Despite the evidence of her achievements—the kingdom she ruled, the city she helped build, the seeming ease with which she navigated between the two worlds of Rome and Egypt—she is generally better known for seducing, managing, and manipulating her Roman lovers, Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

The Romans were the first of many to depict Cleopatra as a cruel Asiatic queen, all greedy ambition and no moral conscience. Alexandre Cabanel's 1887 orientalist painting, Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners, shows the queen lounging on her sofa as prisoners—guinea pigs for her testing of deadly toxins—die in agony around her. The story of a woman who recklessly destroys men, or who is responsible for our eternal exile from the Garden of Eden, or who incites a ruthless murder or a catastrophic war has never gone out of fashion.

Cleopatra: Her History, Her Myth by Francine Prose, from the Yale University Press Ancient Lives series

#what I'm reading#cleopatra#francine prose#cleopatra was my historical blorbo for many years as a child so it was fun to read this and revisit that#I thought it was interesting and I thought she did a good job showing how much of the fascination with cleopatra and her portrayals#throughout history were influenced first by roman colonialism and then orientalism#but ultimately I didn't really feel like I learned anything new or super groundbreaking from reading this

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

A farmer in Gaza discovered a Roman mosaic floor while tending to his olive trees in 2022. The mosaics are "in a perfect state of conservation" and are works of excellent quality.

Looters offered him money for it. He turned them down despite living in an Israeli-controlled territory where more than 50% of the people live in poverty. "I was happy to have found something historical from our ancestors, which belongs to the entire Palestinian nation." [x]

The Al Bureij mosaic is one of the many digging sites severely endangered by occupation bombardment.

#txt#palestine#gaza#archaeology#roman empire#byzantine#mosaic#history#art#zionist occupation#genocide#colonialism

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

@elgringo300 - I don't want to put you on the spot, but this comment is inaccurate in ways that make it a good history lesson. While I'm not a history expert either, I'm interested in the history of early Christianity, and it's a good bit more complicated (and fascinating!) than most people realize.

TLDR: "Roman" and "Christian" were never mutually exclusive categories. The religious fate of the Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity are one and the same.

There are two things you have to understand here:

The story of early Christianity that you get told in church has some gaps in it.

The story of the Fall Of The Roman Empire you get taught in school is often based in older scholarship. It's also often taught by people who don't understand the scale and timing of the events that happened. It's inaccurate to how historians understand the past.

Full disclosure- I'm tired and too lazy to cite sources. I'm also simplifying things dramatically because this is a tumblr post. If you see a tumblr post claiming that everything you know is horse hockey, you should do your own research before you incorporate it into your belief system- and that includes this one.

We good? Moving on.

SO. The story of early Christianity a lot of people learn goes something like this: "Jesus came, taught his followers how to live a good life, died, was resurrected, and went back to heaven. His apostles and followers tried to tell all the world what happened! But the evil Roman Empire tried to stop them and martyred any Christians they caught. Christians persevered, until the Empire collapsed under its own weight, and people were free to be Christian. And then, because Christianity is obviously the Right Way To Live, it spread to the whole world."

...And, well, there's a couple chunks missing from that story. For this post, the part we're concerned about is the bit between "Christians were martyred for their beliefs!" and "Rome fell".

The thing you have to understand about Roman religion is that Romans didn't think about religion the same way we do. In a monotheistic world where religion is usually a set of moral and cultural precepts, it can be hard to imagine a polytheistic world where religion is about the gods. The state religion in Rome- the one the Romans used law and custom to enforce- was about Making Deals With Gods (and ancestors, and heroes, and at certain points the Emperor), asking for their protection and giving them worship and offerings in exchange.

The Romans genuinely did not care what gods you worshiped in your own home. They might make fun of you if you worshiped weird provincial gods; they might be disgusted or angry if you said your gods asked you to break Roman laws. But they did not care what you believed in the same way that most American Christians today care.

What they did care about was whether or not you did the customary sacrifices and offerings that went along with the state religion. The best way to think of it- and this is a dramatic oversimplification- you know those evangelicals who are 'okay' with people not being Christian, but insist that no one is allowed to be gay because gay people make God send hurricanes at them? It was a bit more like that than the people who think that no one can be a good person without being Christian. The Romans were genuinely concerned that the gods would get pissed off if you didn't propitiate them, and no one wanted that.

Generally, if the Romans conquered an area where people were monotheists? An area like, say, Judea? They did not care if you did not believe in their gods. As long as you did the state religion's sacrifices and rituals? They'd be totally cool with you. Hell, they might even try to worship your monotheistic God along with all of theirs. (Remember Paul's sermon at the Temple of Diana on the Unknown God? Yeah.)

The trouble is, monotheists do not, as a rule, like acknowledging gods that are not their god. So there was always some... friction between Rome and Judea. Judea was an outlying border province full of people who were not always cool with the Roman state religion. People who could and did quite violently rebel against Roman rule. People who would get angry and rebellious if you tried to force them to acknowledge that your gods even existed, much less tried to force them to worship. Some emperors decided the best way to handle this was to exempt Jews from following the state religion; it saved everyone from a lot of bloody guerilla warfare. Some emperors decided the best way to handle this was to crack down and use Jews as scapegoats for every bad thing that happened to the Empire.

And for the first hundred years of Christianity's existence, people thought Christianity was just a weird form of Judaism. Legally, socially, and politically, Christians by and large got treated the same way. They were a freaky religious minority in an outlying province. But as long as they followed the rules and made the correct sacrifices at the correct times? Generally, they got ignored. If they refused to make those sacrifices? It depended on the whims of who was enforcing the law. Sometimes, they got ignored. Sometimes, they had their property confiscated. Sometimes, they got fed to lions. It really depended on who was running the show.

So how did we get from "Christianity is a freaky minority of an already strange religious minority in the border provinces" to "most people in Europe are Christian"? Well, there's two pieces to this.

FIRST: because Roman state religion was mostly dedicated to propitiating the gods, and because Rome tended to culturally integrate its provinces rather than enforcing its own customs upon them, mystery cults thrived. A lot of different religions sprung up that promised enlightenment, a higher state of consciousness, or everlasting life. And a lot of people bought into them, because the Roman state religion wasn't very spiritually fulfilling. Think of it like... your weird auntie who goes to a megachurch but swears by tantric yoga, or TikTok witches who say they can talk to angels. I don't know as much about mystery cults in Rome as I'd like, but there were three very popular ones:

Mithraism, which was from the East and which was popular among soldiers.... Sol Invicta, which I know very little about except that it existed... and Christianity, which was popular among common people, women, and slaves. (Incidentally, I could go on about early Christianity and women's lib for hours. Don't get me started.)

Either of these cults- or any of the smaller ones, really- could have wound up taking the place in society that Christianity did. People really want to believe in something bigger than themselves, and Strange Wisdom from Far Away is always going to find a foothold among people who want to believe.

So. Plenty of Romans became Christian. And the early Church's missionary efforts meant that people in Rome, Greece, Egypt, and even farther-flung places converted, because they took the "go ye to all the world" thing seriously. Eventually, a Roman emperor named Constantine converted to Christianity... and began using the state power that had enforced the Roman state religion to spread Christianity. He returned property that the state confiscated, he passed laws banning Christians from having to do state sacrifices, he protected missionaries, and a lot more stuff like that.

Because it was now safe and legally protected to be Christian? Because Christians now had special legal privileges? And because missionaries, emboldened by the Emperor himself, got even more intense in their proselytizing? Christianity spread like wildfire. Plenty of Romans converted. Plenty more stopped thinking of Christians as weird freaks and started thinking of them as their friends and neighbours. And people in the second category might not convert, but their wives and children might.

Here's the last piece of the puzzle. How much time do you think elapsed between Constantine converting to Christianity and the commonly accepted "Fall Of The Roman Empire"? Was it ten years? Twenty? Fifty?

Try closer to a hundred and fifty.

A hundred and fifty years in our past, Queen Victoria was still reigning over England (and brutally conquering New Zealand), Japan was doing the Meiji Restoration, the Mary Celeste was very busy going missing, and Susan B Anthony was casting her first vote.

Think of all the changes that have happened to the world since 1872. Change happened slower in the Classical era. But it still happened, and there was still a very long time for it to happen in. There was plenty of time for people to convert to Christianity before Rome fell. Plenty of people did, because it was popular and safe to. And as time went on, Christianity lost a lot of its rebellious nature and became a religion that was backed up by state power, palatable to people with power, and generally ... well. As someone commented on my religion post, any religion can go bad if it gets in bed with an empire.

And for most people- especially people who weren't in Rome and the parts of the Empire near to it? The "fall of Rome" was a slow process. Rome fell in part because of a bunch of economic crises and a plague, more than anything else. So it wasn't like The Walking Dead; the apocalypse was a very slow burn.

You got less news, less food, less luxuries. You got less people coming from distant provinces, and more strongmen trying to push you around. You got fewer soldiers protecting you, and more bandits. Your grandchildren would realize that they were living in a very different world than you were, but you might not realize just how much things have changed in the moment.

....So yes. Even accepting your premise that Christians put the world back together after Rome fell- which is a huge misunderstanding in its own right, to be clear- most of the Christians in question also thought of themselves as either Romans or as the heirs to Rome's Empire. Look up the Donation of Constantine sometime, or the history of Carolingian France, or the Byzantines. Hell, look at the history of the Holy Roman Empire (which, as we all know, was none of the above).

Like I said, this is all a simplification, and anyone who knows more about the history than I do, please feel free to elaborate. But yeah. Until, like, the Protestant Reformation? Most people did not see "Roman" or "Christian" as in any way contradictory. The reason we do now is largely due to Catholics focusing on martyrs, English religious wars and anti-Catholic sentiment, and Edward Gibbon. It's ahistorical. It's just not true.

If the Roman Empire had (somehow) become atheist, had given atheists special religious privileges, and had encouraged atheist proselytizing? Most people in the former Roman Empire and its descendants' colonies would be atheists. If the Roman Empire's state religion had remained a polytheistic muddle? We'd all be worshiping Jupiter and Juno. If the Roman Empire's state religion was Mithraism, we'd all be worshiping Mithra. Because people respond to incentives, and "the Empire is nudging you into converting" is one hell of an incentive.

#christianity#history#general malarkey#conservative malarkey#roman empire#long post#antisemitism#sexism#colonialism#homophobia#i put a lot of effort into this please read the whole thing before commenting

357 notes

·

View notes

Text

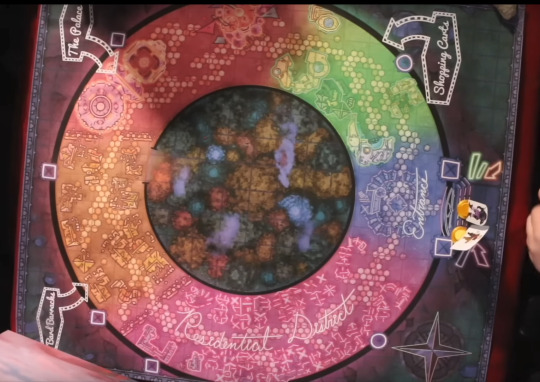

guys. do you ever think about cycles. circles. revolutions. the vicious cycle inherent in the capitalistic colonialist system that poisons interpersonal relationships. because I sure do.

remember the propaganda roman and youngblood heard in episode 6?

"the score of life was risen away from the fiery hands of evil by our glorious bard king. he single-handedly defeated [redacted] with his legendary musical abilities, going beyond what any bard could hope for. he had discovered through this grand trial that he ascended to godhood. he immediately set off to fix the problems of the world with this new found power, taking the old [redacted] palace and raising it far into the sky to create his enlightened bards college. from on high, he saw our world's ills and went about curing them, and created the utopia that we now live in."

remember how neon was built in the shape of a circle?

the bard king is said to have defeated an (unknown) malevolent force and created a utopia. he is regarded as a savior who created a great, grandiose change for the better. however, the bard king is not a savior, and his actions are not good. there is still evil in the world, but instead of it being from this Mysterious Being that we don't know about, its from the bard king himself. his actions have changed the world for the worse, if they have changed anything at all.

the definition of revolution is a sudden, radical, or complete change. this is what the bard king believes that he has done. he, according to himself, has made the world a better place. another definition of revolution is a full circle, or the completion of a cycle. for example, the earth completes a revolution around the sun every 24 hours. this is the type of revolution that the bard king truly created; he has taken power from someone who was using it for evil, only to use that stolen power for evil himself. that's why neon is a circle; it represents the bard king has made no significant change through his actions. he has vanquished a corrupt force, only to be just as horrible in his own way.

its also important to note that neon is a circle built around the forest where the fey live, showing that the "circular revolution" that the bard king created is perpetuating the oppression of the fey.

this "circular revolution" also occurs within the bard college itself. the bard king "cycles" through his first chairs. he elects a new one, puts them under immense pressure and abuses his power over them, elects a new one, and then the cycle repeats.

#rswr#roleslaying with roman#rswr meta#also interesting how the bard king ripped the castle from the earth to use for himself. colonialism metaphor perhaps?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perusing books about the Roman Empire is a trip. Tf do you mean "The Dark Side of the Roman Empire"? It's the Roman Empire?? What the fuck was the bright side?? The sacking and raping and pillaging and subjugation and slavery?? The sexual violence?? The violent oppression of anybody that wasn't a free and landed male Roman citizen?? Sure a bunch of old guys came up with some important ideas and art, but how many people who would have had more of them were denied the chance for the same?? How tf are empires a social good or instrumental to peace, prosperity and collaboration?? Hello??

#the colonial brainrot is truly insane#'golden age' golden for WHOM motherfucker#do they think empires only turned out to be a bad idea during the 20th century? what?#white supremacy#history#roman empire#decolonization#colonialism#colonization#imperialism#knee of huss

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok but Nakia talking about how the Ancient Greeks and Romans are taught in Western countries more predominantly than the Persian and Byzantine Empires WAS SO GOOD. I know it was throw away line, but like IT'S TRUE AND SHE'S RIGHT. It's time to diversify your history lessons.

#i was gonna rant a lot more but i think this gets the message#history is sometimes taught with such bias and ugh it annoys me#the persians though brutal were pretty cool#ancient greeks you mean the ancient MISOGYNISTS#romans you mean COLONIALISM#ok I'll stop#ms marvel#nakia#kamala khan#bruno#marvel#history#persian empire#roman empire#ancient greeks

178 notes

·

View notes