#Richard Rhodes

Text

Why Robert Oppenheimer's Atomic Bomb Still Haunts Us

— By Richard Rhodes | Published May 15, 2013

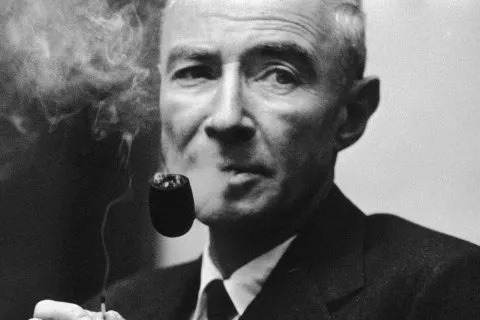

Oppenheimer spearheaded the creation of the atom bomb. René Burri/Magnum

Robert Oppenheimer oversaw the design and construction of the first atomic bombs. The American theoretical physicist wasn't the only one involved—more than 130,000 people contributed their skills to the World War II Manhattan Project, from construction workers to explosives experts to Soviet spies—but his name survives uniquely in popular memory as the names of the other participants fade. British philosopher Ray Monk's lengthy new biography of the man is only the most recent of several to appear, and Oppenheimer wins significant assessment in every history of the Manhattan Project, including my own. Why this one man should have come to stand for the whole huge business, then, is the essential question any biographer must answer.

It's not as if the bomb program were bereft of men of distinction. Gen. Leslie Groves built the Pentagon and thousands of other U.S. military installations before leading the entire Manhattan Project to success in record time. Hans Bethe discovered the sequence of thermonuclear reactions that fire the stars. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi invented the nuclear reactor. John von Neumann conceived the stored-program digital computer. Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam co-invented the hydrogen bomb. Luis Alvarez devised a whole new technology for detonating explosives to make the Fat Man bomb work, and later, with his son, Walter, proved that an Earth-impacting asteroid killed off the dinosaurs. The list goes on. What was so special about Oppenheimer?

He was brilliant, rich, handsome, charismatic. Women adored him. As a young professor at Berkeley and Caltech in the 1930s, he broke the European monopoly on theoretical physics, contributing significantly to making America a physics powerhouse that continues to win a freight of Nobel Prizes. Despite never having directed any organization before, he led the Los Alamos bomb laboratory with such skill that even his worst enemy, Edward Teller, told me once that Oppenheimer was the best lab director he'd ever known. After the war he led the group of scientists who guided American nuclear policy, the General Advisory Committee to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He finished out his life as director of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he welcomed young scientists and scholars into that traditionally aloof club.

August 9, 1945: Nagasaki is hit by an atom bomb. Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum/EPA

Those were exceptional achievements, but they don't by themselves explain his unique place in nuclear history. For that, add in the dark side. His brilliance came with a casual cruelty, born certainly of insecurity, which lashed out with invective against anyone who said anything he considered stupid; even the brilliant Bethe wasn't exempt. His relationships with the significant women in his life were destructive: his first deep love, Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley professor, was a suicide; his wife, Kitty, a lifelong alcoholic. His daughter committed suicide; his son continues to live an isolated life.

His Choices or Mistakes, Combined with his Penchant for Humiliating Lesser Men, Eventually Destroyed Him.

Oppenheimer's achievements as a theoretical physicist never reached the level his brilliance seemed to promise; the reason, his student and later Nobel laureate Julian Schwinger judged, was that he "very much insisted on displaying that he was on top of everything"—a polite way of saying Oppenheimer was glib. The physicist Isidor Rabi, a Nobel laureate colleague whom Oppenheimer deeply respected, thought he attributed too much mystery to the workings of nature. Monk notes his curiously uncritical respect for the received wisdom of his field.

Monk's discussion of Oppenheimer's work in physics is one of his book's great contributions to the saga, an area of the man's life that previous biographies have neglected. In the late 1920s Oppenheimer first worked out the physics of what came to be called black holes, those collapsing giant stars that pull even light in behind them as they shrink to solar-system or even planetary size. Some have speculated Oppenheimer might have won a Nobel for that work had he lived to see the first black hole identified in 1971.

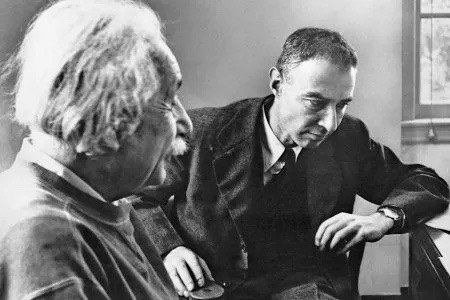

Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein, circa the 1940s. Corbis

Oppenheimer's patriotism should have been evident to even the most obtuse government critic. He gave up his beloved physics, after all, not to mention any vestige of personal privacy, to help make his country invulnerable with atomic bombs. Yet he risked his work and reputation by dabbling in left-wing and communist politics before the war and lying to security officers during the war about a solicitation to espionage he received. His choices or mistakes, combined with his penchant for humiliating lesser men, eventually destroyed him.

One of those lesser men, a vicious piece of work named Lewis Strauss, a former shoe salesman turned Wall Street financier and physicist manqué, was the vehicle of Oppenheimer's destruction. When President Eisenhower appointed Strauss to the chairmanship of the AEC in the summer of 1953, Strauss pieced together a case against Oppenheimer. He was still splenetic from an extended Oppenheimer drubbing delivered during a congressional hearing all the way back in 1948, and he believed the physicist was a Soviet spy.

Strauss proceeded to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance, effectively shutting him out of government. Oppenheimer could have accepted his fate and returned to an academic life filled with honors; he was due to be dropped as an AEC consultant anyway. He chose instead to fight the charges. Strauss found a brutal prosecuting attorney to question the scientist, bugged his communications with his attorney, and stalled giving the attorney the clearances he needed to vet the charges. The transcript of the hearing In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is one of the great, dark documents of the early atomic age, almost Shakespearean in its craven parade of hostile witnesses through the government star chamber, with the victim himself, catatonic with shame, sunken on a couch incessantly smoking the cigarettes that would kill him with throat cancer at 63 in 1967.

Rabi was one of the few witnesses who stood up for his friend, finally challenging the hearing board in exasperation, "We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it [because of Oppenheimer's work], and what more do you want, mermaids?" What Strauss and others, particularly Edward Teller, wanted was Oppenheimer's head on a platter, and they got it. The public humiliation, which he called "my train wreck," destroyed him. Those who knew him best have told me sadly that he was never the same again.

For Monk as for Rabi, Oppenheimer's central problem was his hollow core, his false sense of self, which Rabi with characteristic wit framed as an inability to decide whether he wanted to be president of the Knights of Columbus or B'nai B'rith. The German Jews who were Oppenheimer's 19th-century forebears had worked hard at assimilation—that is, at denying their religious heritage. Oppenheimer's parents submerged that heritage further in New York's ethical-culture movement that salvaged the humanism of Judaism while scrapping the supernatural overburden. Oppenheimer, actor that he was, could fit himself to almost any role, but turned either abject or imperious when threatened. He was a great lab director at Los Alamos because of his intelligence—"He was much smarter than the rest of us," Bethe told me—because of his broad knowledge and culture; because of his psychological insight into the complicated personalities of the gifted men assembled there to work on the bomb; most of all because he decided to play that role, as a patriotic citizen, and played it superbly.

Monk is a levelheaded and congenial guide to Oppenheimer's life, his biography certainly the best that has yet come along. But he devotes far too many pages to Oppenheimer's Depression-era flirtation with communism, a dead letter long ago and one that speaks more of a rich esthete's awakening to the suffering in the world than to Oppenheimer's political convictions. He doesn't always get the science right. Most of the errors are trivial, but a few are important to the story.

Their Fundamental Objection Was to Giving up Production of Real Weapons so That Teller Could Pursue His Pipe Dream, a Dead-end Hydrogen Bomb Design.

A fundamental reason Oppenheimer opposed a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb in response to the first Soviet atomic-bomb test in 1949 was the requirement of Edward Teller's "Super" design for large amounts of a rare isotope of hydrogen, tritium. Tritium is bred by irradiating lithium in a nuclear reactor, but the slugs of lithium take up space that would otherwise be devoted to breeding plutonium. To make tritium for a hydrogen bomb that the U.S. did not know how to build would have required sacrificing most of the U.S. production of plutonium for devastating atomic bombs the U.S. did know how to build. To Oppenheimer and the other scientists on the GAC, such an irresponsible substitution as an answer to the Soviet bomb made no strategic sense. It's true that the hydrogen bomb with its potentially unlimited scale of destruction made no military sense to them either—and was morally repugnant to some of them as well. But their fundamental objection, which Monk overlooks, was to giving up production of real weapons so that Teller could pursue his pipe dream, a dead-end hydrogen bomb design that never worked.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967)

More egregious is Monk's notion that the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, Oppenheimer's mentor during the war on the international implications of the new technology, pushed for the bomb's use on Japan to make its terror manifest. He did not. He pushed, to the contrary, for the Allies, the Soviet Union included, to discuss the implications of the bomb prior to its use and to devise a framework for controlling it. Bohr foresaw that the bomb would stalemate major war, as it has, but correctly feared that U.S. secrecy about its development would lead to a U.S.-Soviet arms race. He conferred with both Roosevelt and Churchill about presenting the fact of the bomb to the Russians as a common danger to the world, like a new epidemic disease, that needed to be quarantined by common agreement. Churchill vehemently disagreed, and Roosevelt was old and ill. The moment passed. The arms race followed, as Bohr foresaw, and with diminished force, among pariah states like Iran and North Korea, continues to this day.

Monk's Oppenheimer is a less appealing figure than the Oppenheimer of previous biographies, perhaps because, as an Englishman, Monk is less susceptible to Oppenheimer's rhetorical gifts and more candid about calling out his evasions. He pulls together most of what several generations of Oppenheimer scholars have found and offers new revelations as well. Yet there's a faint whiff of condescension in his portrait, and the real Oppenheimer, the man whom so many loved and admired, still somehow escapes him. He misses the deep alignment of Robert Oppenheimer's life with Greek tragedy, the charismatic hubris that was his glory but also the flaw that brought him low. But maybe I'm expecting too much: maybe only a large work of fiction could assemble that critical mass.

#Robert Oppenheimer#Atomic Bomb#Richard Rhodes#World War II#Manhattan Project#Ray Monk#Gen. Leslie Groves#Pentagon#Hydrogen Bomb#Edward Teller | Stanislaw Ulam#Nobel Prize#Princeton University#Albert Einstein#President Eisenhower#Lewis Strauss#Hydrogen | Tritium | Plutonium#Roosevelt | Churchill#US — Soviet Union

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Just saw the Oppenheimer film and hungry for more?...

American Prometheus, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin. “The film is about Oppenheimer, not the project and afterwards. If you want to go deeper, I recommend you read the book the movie was based on and think more broadly about the impact of the Manhattan Project.”

“The Oppenheimer Issue” of Los Alamos National Laboratory’s National Security Science magazine has lots of great stories about Oppenheimer and the laboratory.

Plutonium 1943–1945, by Los Alamos Historical Society....

The Day After Trinity, “an Academy Award-winning documentary, which can be viewed for free on the Criterion app, is an excellent first-hand account with interviews of key scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, who knew Oppenheimer closely. This 1981 documentary is a very good complement to the movie, Oppenheimer. Some of the interesting figures interviewed extensively are Robert Oppenheimer’s brother, Frank; the Nobel laureate Hans Bethe; and Freeman Dyson, who were all part of the Manhattan Project. Their recollections of that important period and the underlying debates are invaluable oral histories for researchers and the general public.”...

Hiroshima “This short book, by John Hersey, is based on what was initially a lengthy article in the New Yorker and was published a couple of years after the atomic bombing. It gave Americans their first description of the actual effects of dropping the bomb. This helps make up for what many critics have felt was an omission in the movie.”

The Making of the Atomic Bomb, by Richard Rhodes, “is the definitive book account of the Manhattan Project and the science and engineering behind the bomb.”

The Winning Weapon, by Gregg Herken, “is a historian’s review of how the U.S. approached the questions of arms control and a possible arms race in the years right after World War II.”

The Advisors: Oppenheimer, Teller, and the Superbomb, by Herbert York, “is a good account of the dispute between Oppenheimer and Teller over whether to build the H-bomb, which became a key factor in the hearing that led to Oppenheimer losing his security clearance.”...

Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World, by Lesley M.M. Blume, “is a good companion book of John Hersey’s Hiroshima and was published on the 75th anniversary of the bombing.”

“If you want to add some perspectives from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I would definitely recommend the Hiroshima Memorial Museum Online and the recently developed online No More Hiroshima and Nagasaki Museum.”

“The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Oppenheimer Collection has many good articles with various perspectives.”...'

#Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#American Prometheus#Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed it to the World#Lesley M.M. Blume#The Advisors: Oppenheimer Teller and the Superbomb#Herbert York#The Winning Weapon#Gregg Herken#The Day After Trinity#Hiroshima#Richard Rhodes#Hans Bethe#Freeman Dyson#Frank Oppenheimer#Los Alamos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

PLUS, ZIZZ!, GENJI and the Bomb: The Monthly Gravette #20

As always, a shout-out to Ben and Nate of Words About Books; you may find their own blog here.

I realize it’s been a while since the last “Monthly” Gravette post. No excuses, only reasons – and this time around, the reason (besides external pressures) is that from April to early July I was struggling with a certain book: Joseph McElroy’s Plus. Now, Plus isn’t a long book – at 215 pages, it’s…

View On WordPress

#Book Reviews#Books#cw grooming#Edward G. Seidensticker#Joseph McElroy#Len Lye#Murasaki Shikibu#Plus#Richard Rhodes#Roger Horrocks#The Making of the Atomic Bomb#The Monthly Gravette#The Tale of Genji#Zizz!

0 notes

Text

#The Making of the Atomic Bomb: 25th Anniversary Edition#Richard Rhodes#Holter Graham#books#nonfiction

1 note

·

View note

Text

YOU'VE ALWAYS BEEN MY DREAM // CHIRON AND KEVIN

Moonlight (2016) dir. Barry Jenkins // Moonlight (2016) dir. Barry Jenkins // Warsan Shire "Souvenir," Our Men Do Not Belong to Us // Anne Sexton A Self-Portrait in Letters // Olivia Gatwood "The Lover as a Cult," Life of the Party // Moonlight (2016) dir. Barry Jenkins // Anne Sexton "The Papa and Mama Dance," Complete Poems of Anne Sexton // Moonlight (2016) dir. Barry Jenkins // Terry Pratchett Good Omens // Richard Siken Crush // Louise Glück Departure // Moonlight (2016) dir. Barry Jenkins // Margaret Atwood The Door

#watched moonlight yesterday#i hope they live happily and grow old together#moonlight#moonlight movie#barry jenkins#on self#on love#on falling in love#web weave#web weaving#warsan shire#anne sexton#olivia gatwood#terry pratchett#richard siken#margaret atwood#poetry#words#writing#text#poem#spilled poetry#spilled ink#spilled thoughts#spilled emotions#trevante rhodes#andre holland#dark academia poetry#dark academia#dark academia quote

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

MULHOLLAND DRIVE (2001)

directed by David Lynch

#mulholland drive#mulholland dr#david lynch#naomi watts#diane selwyn#betty#laura harring#rita#camilla rhodes#richard green#rebekah del rio#bonnie aarons#film#filmedit#movie#movieedit#gifset#2000s#2001

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

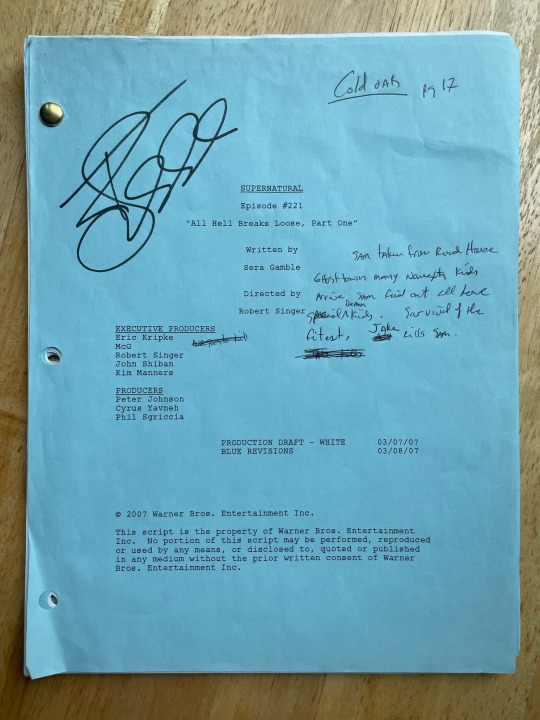

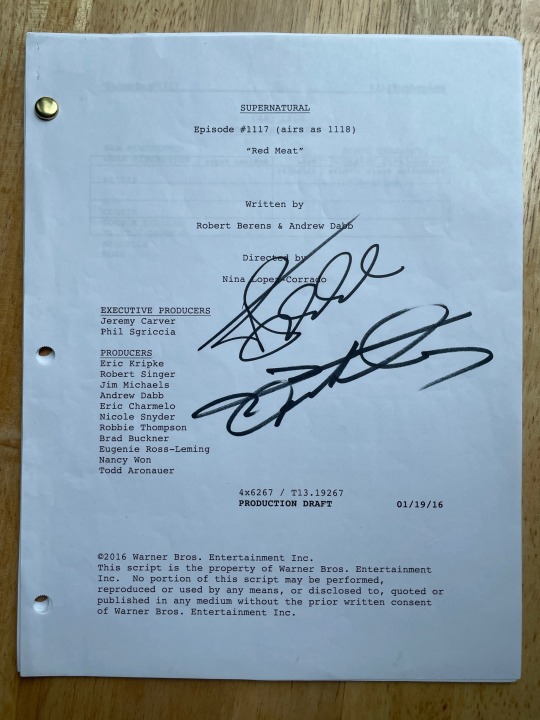

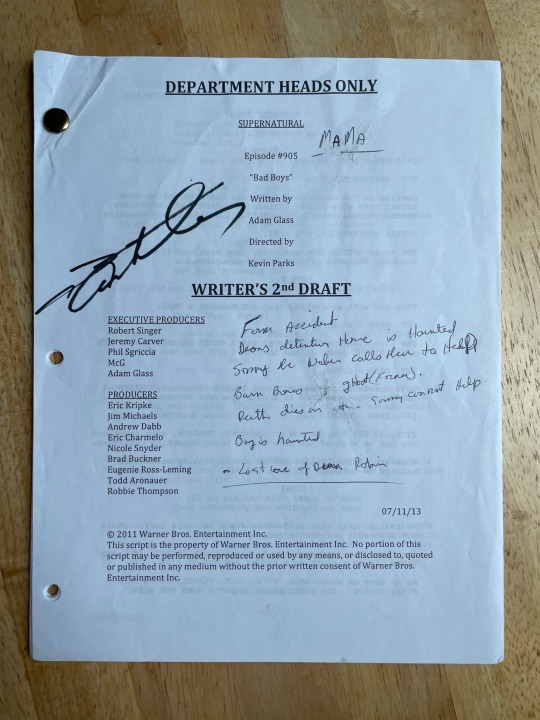

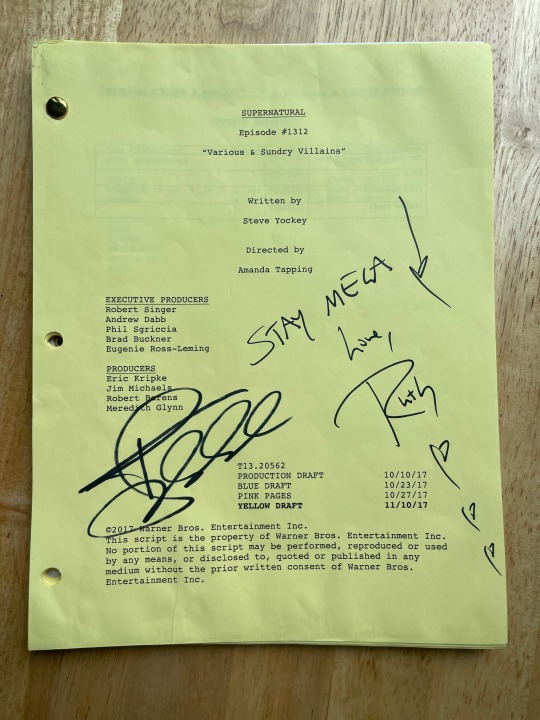

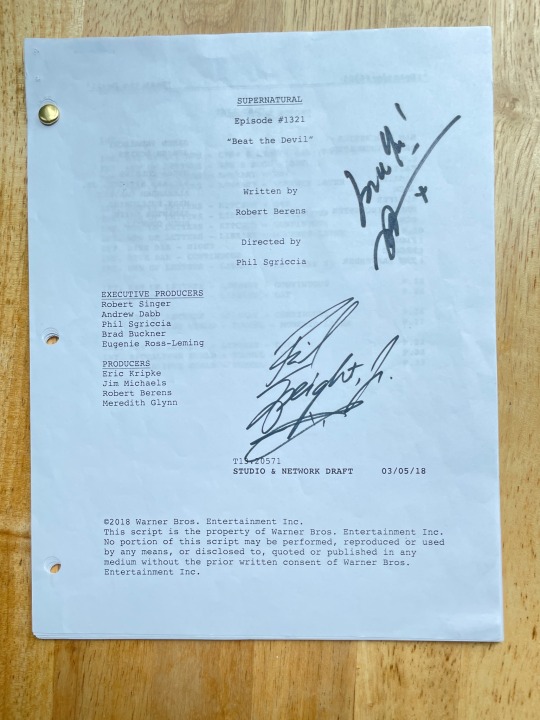

Because of the Site Formerly Known as Twitter, we moved up the start date 🙃

SPNScriptHunt's Script Raffle for World Central Kitchen

World Central Kitchen is a global organization providing food relief. They've assisted in war zones, in refugee camps, in areas devastated by hurricanes, in areas that are devastated by economic conditions and areas that are devastated due to emotional loss.

For every $10 you donate to World Central Kitchen, you will be entered in a raffle to win one of up to 30 Supernatural scripts autographed by cast members at conventions in the United States, Canada, the UK, and Italy: the more we raise the more prizes we'll add!

The scripts shown here are just a few of the ones we're offering, the complete list and all the details (with preview images) is on our fundraiser page:

https://donate.wck.org/spnscripthunt1117

Raffle closes on Saturday, August. 26 at 11:59pm (Eastern Time). Winners will be drawn by a random number generator and contacted by Tuesday, August 28, 2023. We require an email address to contact winners so if you donated anonymously but would like to enter the raffle, please email your receipt to spnscripthuntgiving @ gmail before the drawing date. Winners will have 72 hours to respond, and will be required to provide their physical mailing address and to cover the cost of shipping (currently $10 for priority mail insured inside the US, international rates to be determined as necessary).

PLEASE NOTE: IF YOU ARE UNDER 18 YEARS OF AGE AND WISH TO DONATE, PLEASE ENSURE YOU HAVE PRIOR AUTHORIZATION FROM CREDIT/ACCOUNT HOLDER.

#admin: lets-steal-an-archive#supernatural#world central kitchen#jensen ackles#jared padalecki#misha collins#richard speight jr#ruth connell#mark sheppard#alexander calvert#samantha smith#kim rhodes#dj qualls#and more

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

creationentertainment: Photo ops are so much fun at our conventions!

Here’s a peek at some fun ops during The Road So Far… The Road Ahead tour!

We hope to see you at one of the tour stops next year! Locations, details, and tickets are available at CreationEnt.com!

#j2#jared padalecki#jensen ackles#mark sheppard#keegan allen#jake abel#mitch pileggi#misha collins#jojo fleites#drake rodger#meg donnelly#briana buckmaster#rob benedict#billy moran#stephen norton#michael borja#kim rhodes#richard speight jr#cons

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tony: Oh Platypus come on, y’know I don’t sleep with guys on the first date!

Rhodey: Tiberius Stone, Reed Richards, Stephen Strange…

Tony: [at the looks Steve and Bucky shoot him] Anymore!!

#original: friends#robert downey jr#don cheadle#chris evans#sebastian stan#tony stark#steve rogers#bucky barnes#james rhodey rhodes#stephen strange#reed richards#stuckony#winteriron#stony#the avengers#non avengers quotes#quoting the avengers

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

Petition to remake all disney movies but with the supernatural cast

#supernatural#spn#osric chau#jensen ackles#jared padalecki#mark pellegrino#mark sheppard#jim beaver#ruth connell#jeffrey dean morgan#brianna buckmaster#kim rhodes#misha collins#jake abel#richard speight jr#alexander calvert#samantha smith#felicia day#rob benedict#dj qualls#rachel miner#timothy omundson#curtis armstrong#sebastian roche#chad lindberg#julian richings#kathryn newton#genevieve padalecki#daneel ackles

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Moviegoers who watch the closing credits of Oppenheimer may notice a familiar name. Writer and director Christopher Nolan's three-hour biopic about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist who led the Manhattan Project during World War II to develop the atomic bomb, ends with a thank-you to retired U.S. senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont.

Unrelated to Leahy's appearances in Nolan's Batman trilogy, this cinematic shout-out is about righting a decades-old injustice. Vermont's longest-serving U.S. senator played a critical role in clearing Oppenheimer's name 55 years after his death. And longtime Leahy staffer Tim Rieser deserves his own screen credit for the role he played in that process.

The Norwich native worked for Leahy for 37 years, mostly as his senior foreign policy aide on the Senate Appropriations Committee. Rieser's political savvy and deep relationships in Washington, D.C., earned him a level of influence rarely achieved by Capitol Hill staffers. In one of his final acts before Leahy retired in January, Rieser helped right a grievous wrong that ended Oppenheimer's career — one that, as viewers of Oppenheimer now know, was based on a lie.

In June 1954, at the height of the Red Scare, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission voted to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance. The decision was influenced by Oppenheimer's past association with communists and justified with the baseless allegation that he was a Soviet spy.

In actuality, Oppenheimer's fall from grace was a political hit job motivated by his opposition to U.S. development of the hydrogen bomb. Denying the physicist access to nuclear secrets effectively ended his government career and left a stain on his reputation that endured long after his death in 1967.

Nolan's blockbuster movie, which is based on the 2006 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Martin J. Sherwin and Kai Bird, chronicles much of that previously untold story. But viewers may leave the theater thinking that Oppenheimer was never vindicated.

In fact, Rieser, 71, spent years working with Sherwin and Bird to do just that. His motivation wasn't just to remove a black mark from the history of one of the most important scientists of the 20th century. As he explained to Seven Days, Rieser also wanted to affirm the ongoing importance of protecting scientists who express their political views from becoming targets of government retribution.

The cause was personal for the former Vermont public defender, who lives in Arlington, Va., but still owns, with his siblings, their family home in Norwich. Rieser's parents, Leonard and Rosemary Rieser, worked on the Manhattan Project, knew Oppenheimer and had tremendous respect for him.

"It was probably the most memorable year of their lives," Rieser said of his parents' stint in Los Alamos, N.M. "My father, my mother and everybody else there just revered Oppenheimer. He was larger than life for people their age."

Leonard Rieser was 21 in 1943 when he graduated with a physics degree from the University of Chicago, site of the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. The following year, he got married, enlisted in the U.S. Army and, because of his knowledge of nuclear physics, was sent to Los Alamos.

The Riesers knew little about where they were going or what they'd do there. For more than a year, they couldn't disclose their whereabouts to family and friends or reveal their activities. While Rieser's mother ran the Los Alamos nursery school, his father worked alongside such scientists as Niels Bohr, Enrico Fermi and Hans Bethe.

The Trinity test, the first-ever detonation of an atomic bomb, occurred on July 16, 1945, which was also the Riesers' first wedding anniversary. Leonard witnessed the blast from less than 20 miles away, face down in the sand.

After the war, Leonard took a teaching job at Dartmouth College, where he later became chair of the physics department, then dean of faculty and provost. When president Lyndon Johnson gave Oppenheimer the prestigious Enrico Fermi Award in 1963, Leonard invited the physicist to speak at Dartmouth and even hosted him at their home.

Tim Rieser, who was only 5 at the time, doesn't remember meeting Oppenheimer, but he grew up hearing stories about the Manhattan Project and still has his father's correspondence with the physicist.

He cannot recall his parents discussing Oppenheimer's blacklisting. "I can only assume ... that they must have been appalled," he said.

So were others in the scientific community. Shortly after the 1954 ruling, 500 scientists signed a letter urging the Atomic Energy Commission to reverse its decision. But it would fall to the next generation to take up that cause.

Bird related in his July 7 New Yorker article "Oppenheimer, Nullified and Vindicated" how Sherwin spent 25 years researching the Oppenheimer case before Bird joined him on the project in 2000. In 2010, with the Pulitzer under their belt, the two authors tried unsuccessfully to convince president Barack Obama's administration to reinstate Oppenheimer's security clearance.

Others made similar attempts. In 2011, senator Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.) sent a 20-page memo urging Oppenheimer's vindication to secretary of energy Steven Chu, who was a scientist and cowinner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1997. Chu never acted on that memo, and Bingaman retired from the Senate in 2013.

Next, Sherwin and Bird approached Rieser, whom Bird had known for years. Their interest in the Vermont aide had nothing to do with his personal connection to Oppenheimer, of which neither was aware. (Coincidentally, Leonard Rieser had once hired Sherwin to teach at Dartmouth.)

The biographers' interest in Rieser was a political strategy: A seasoned Capitol Hill staffer, he worked for one of the most powerful Democrats in the Senate and had access to high-ranking officials in the Obama administration.

Rieser said it wasn't until he read American Prometheus that he grasped the scope of the miscarriage of justice done in 1954.

"Until then, I didn't know what had happened to Oppenheimer," he said. "I don't think many people did."

Uniquely Qualified

It's hard to imagine anyone else on Capitol Hill who could have brought to the task of clearing Oppenheimer the combination of political clout, governmental savvy, personal motivation and professional autonomy that Rieser did. Because Rieser had worked for Leahy since 1985, the senator knew his parents. After Leonard Rieser died and the Montshire Museum of Science in Norwich renamed part of the museum in his honor, Leahy attended the dedication ceremony. And because the senator shared Rieser's view that Oppenheimer had been railroaded, he gave Rieser broad discretion on the project.

Rieser had earned a reputation as someone who knew how to get things done in Washington. He helped draft Leahy's 1992 signature legislation banning the sale of land mines. He was also an architect of the so-called Leahy Law, which outlawed the export of U.S. arms to countries that violate human rights with impunity — an effort that made Rieser the target of a character assassination campaign by Guatemala's then-president, Otto Pérez Molina. In her book Sweet Relief: The Marla Ruzicka Story, author Jennifer Abrahamson described Rieser as "the conscience of the Senate."

Rieser was known for his dogged persistence. In the New Yorker piece, Bird described him as "relentless."

After Alan Gross, a U.S. government contractor, was jailed in Cuba in 2009 and accused of spying, Rieser spent years using back-channel diplomacy to secure his release, making multiple trips to Havana and enlisting the help of Pope Francis. The effort succeeded in 2014. According to the New York Times, once the deal was finalized and Obama called Leahy to thank him, the Vermont senator told the president, "I could not have done it without Tim Rieser."

Rieser brought that same determination to the Oppenheimer cause. In the summer of 2016, he penned a letter from Leahy, cosigned by Sens. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) and Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), asking Obama to reinstate Oppenheimer's security clearance. That letter landed on the desk of secretary of energy Ernest Moniz.

"He's a nuclear physicist," Rieser said, "so we thought, If there's anyone who would want to clear Oppenheimer's name, you would think it would be him."

But reversing a 1954 decision on the security clearance of a scientist who died in 1967 was more nettlesome than it looked at first. However corrupt and flawed that process had been, Rieser said, Oppenheimer had lied to a federal investigator.

At issue, he explained, was the so-called "Chevalier incident." Haakon Chevalier was a professor of French literature at the University Of California, Berkeley who met Oppenheimer in 1937. The two became friends, and, in 1943, Chevalier and his wife dined at the Oppenheimers' home.

That evening, Chevalier mentioned to Oppenheimer that the U.S. government wasn't sharing its nuclear secrets with the Soviets, who were U.S. allies at the time. When Chevalier told Oppenheimer that he knew of someone who could get that information to the Russians through back channels, Oppenheimer called the idea treasonous and ended the discussion.

Oppenheimer later disclosed that conversation to general Leslie Groves, the U.S. Army officer who oversaw the Manhattan Project, but he didn't reveal Chevalier's identity. When a federal investigator interrogated him about it, Oppenheimer concocted a fake story to protect his friend.

Why would such historical details matter decades after the fact?

"Moniz was afraid of creating a standard for Oppenheimer that was different from those seeking a security clearance today," explained Rieser, who has a security clearance himself. Though he vehemently disagreed with the Department of Energy's legal argument, Rieser understood why Moniz wouldn't want to set a precedent of giving preferential treatment to someone based merely on their public stature.

As a concession, Moniz renamed a DOE fellowship in honor of Oppenheimer, which wasn't at all what Bird, Sherwin and Rieser had sought. In the meantime, Donald Trump was elected president, at which point Bird and Sherwin essentially gave up the fight.

But not Rieser. He made little progress during the Trump years, which often had a skeptical, if not antagonistic, relationship with science and scientists.

"Generally, when I try to solve a problem, I do everything I can until I finally feel like I've exhausted everything I can possibly do," he said. "I also felt it was so outrageous what had been done to Oppenheimer. It was pure vindictiveness and politics."

Carrying the Day

To make his case, Rieser had to show the government why the Oppenheimer decision still matters — a quest with personal resonance. After the war, Rieser's father, like Oppenheimer, was conflicted about the way the atomic bomb had been used. Having visited Hiroshima, he devoted much of the rest of his life to advocating for strict controls on nuclear energy and nuclear weapons. Also like Oppenheimer, he once chaired the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a nonprofit organization devoted to controlling nuclear weapons and other new technologies that can negatively affect humanity. Rieser was incensed that the government could exact retribution against scientists merely for expressing controversial or unpopular views.

"So when [Joe] Biden got elected," Rieser said, "I decided we should try again."

In June 2021, Rieser wrote a second letter to the DOE, signed by Leahy and the same three Democratic senators. When two months passed with no reply, he called "this guy I knew" at the department.

Ali Nouri had worked in the Senate for about a decade and had once sold Rieser a Ping-Pong table through Craigslist. After leaving the Hill, Nouri went to work for the Federation of American Scientists before Biden tapped him to be assistant secretary of congressional relations at the DOE.

Nouri replied to Rieser a few days later.

"'I think you're going to get the same answer,'" Rieser recalled Nouri telling him. "So I said, 'Then don't answer it. I'm going to write a different letter.'"

The underlying problem, Rieser explained, lay in the nature of the request. He couldn't ask the DOE simply to reinstate Oppenheimer's security clearance, because that would require a new hearing, one that was fair, impartial and, obviously, impossible, given that Oppenheimer is dead. Instead, Rieser decided to ask the department to "nullify" the 1954 decision.

Beginning in August 2021, Rieser drafted a third letter to Biden's secretary of energy, Jennifer Granholm. This one not only detailed the injustices and illegalities of the 1954 proceedings but also highlighted why the decision should be nullified. It read, in part:

Government scientists, whether renowned like Oppenheimer or a technician laboring in obscurity, including those who risk their careers to warn of safety concerns or to express unpopular opinions on matters of national security, need to know that they can do so freely and that their cases will be fairly reviewed based on facts, not personal animus or politics.

After more than a year of working on the letter, Rieser and Leahy got 42 other senators to sign it, including four Republicans: Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), James Inhofe (R-Okla.) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Ala).

Even with such bipartisan backing, Rieser said, he feared that the endorsement of 43 senators might not be enough to "carry the day." So he asked Thomas Mason, director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, to pen a letter in support. Mason did so and got all seven surviving former directors of the Los Alamos lab to sign it, too.

Next, Rieser contacted the heads of the Idaho National Laboratory, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, American Physical Society and Federation of American Scientists. Though Sherwin had died of lung cancer in 2021, Rieser asked Bird and Richard Rhodes, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Making of the Atomic Bomb, to pen similar letters to the energy secretary. It didn't hurt that Nolan's Oppenheimer was scheduled for release the following year.

"What I've learned over the years in Congress," Rieser explained, "is, if you're going to take on a difficult problem, you have to use every ounce of energy you can muster and stick with it no matter how long it takes."

In late August 2022, Rieser compiled all the supporting materials into a binder, then bicycled down to the DOE headquarters and hand-delivered it to Nouri to present to Granholm.

"And then I waited," he said.

On December 16, 2022, Granholm issued a five-page order vacating the Atomic Energy Commission's 1954 decision against Oppenheimer. She wrote:

When Dr. Oppenheimer died in 1967, Senator J. William Fulbright took to the Senate floor and said "Let us remember not only what his special genius did for us; let us also remember what we did to him." Today we remember how the United States government treated a man who served it with the highest distinction. We remember that political motives have no proper place in matters of personnel security. And we remember that living up to our ideals requires unerring attention to the fair and consistent application of our laws.

"It had everything that I could have hoped for," Rieser said. "Granholm felt, as senator Leahy and I did, that this is as relevant today as it was 70 years ago."

Even after Oppenheimer's vindication, Rieser felt that his work wasn't done. Knowing that millions of people would see Oppenheimer, he suggested to Nolan, whom he knew through Bird and Leahy's Batman cameos, that he include an epilogue to that effect; he even suggested the wording.

Ultimately, Nolan didn't include it. While Rieser has no hard feelings about not getting thanked in the movie himself — Senate staffers are accustomed to letting their bosses take credit for their work — he wishes that viewers of the film knew the final outcome. As he put it, "It's important that people know there is another chapter, and an important one, albeit many, many years later."

Rieser, who now works as a senior adviser to Sen. Peter Welch (D-Vt.) hasn't remained entirely in the shadows. In addition to being featured in last month's New Yorker piece, he will be in two forthcoming documentaries about Oppenheimer's life.

For one, Rieser was interviewed in the late physicist's New Mexico house. While sitting in Oppenheimer's living room, he remembers thinking, "If only my parents could have been here! None of us could ever have imagined that I would be doing such a thing. It's amazing how life does come full circle."'

#Tim Rieser#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#The Manhattan Project#Atomic Energy Commission#American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer#Kai Bird#Martin J. Sherwin#Los Alamos#Haakon Chevalier#Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists#President Obama#Jennifer Granholm#Richard Rhodes#The Making of the Atomic Bomb

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tbh I would sell my soul for another season of Kings Of Con

#rob benedict#richard speight jr#Kim Rhodes#kings of con#jensen ackles#jared paladecki#misha collins#Matt cohen#season 2#this show is amazing#Osric Chau#Kurt Fuller#Sebastian Roché#gil mckinney#Kings of con: podcast

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

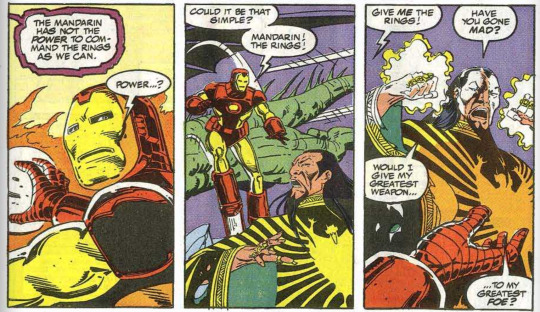

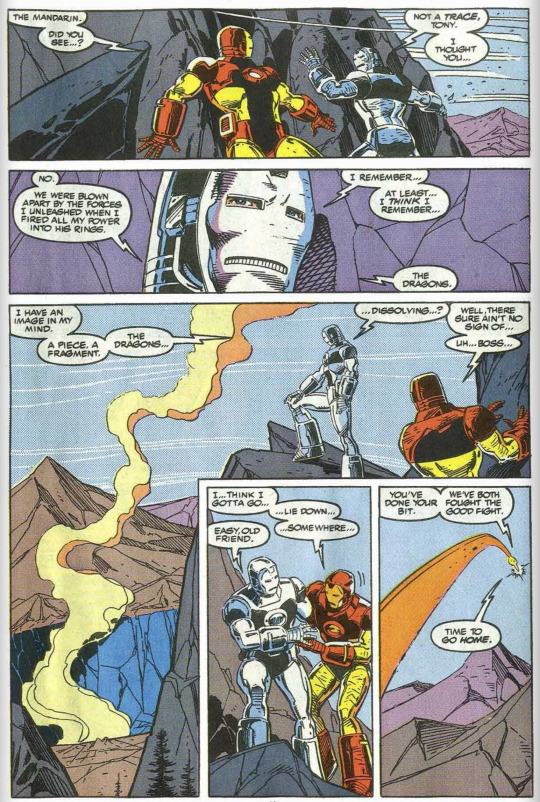

Tony realizes that the main problem is, that when serving as a battery, a Human can only do so much... and so he overcharges the rings with his suit to cause a massive explosion large enough to be picked up by a ton of people back on the East Coast.... and in the end we learn the black dissolved all of the Makluans, but no one knows what happened to the Mandarin...

#Marvel#Iron Man#Tony Stark ~ Iron Man#James Rhodes#Reed Richards ~ Mr. Fantastic#Ben Grimm ~ Thing#Peter Parker ~ Spider Man#Mary Jane Watson#Eric Masterson ~ Thor#Ted Sallis ~ Man Thing#Mandarin

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

green son or purple daughter

11 notes

·

View notes