#Haakon Chevalier

Text

Frantz Fanon, (1964), Letter to the Resident Minister (1956), in Toward the African Revolution. Political Essays, Translated from the French by Haakon Chevalier (1967), Grove Press, New York, NY, 1988, pp. 52-54 (pdf here)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Popular responses to Christopher Nolan’s latest cinematic offering, Oppenheimer, have generally been positive, with the film generating unexpected commercial success given its length and subject matter. However, audience opinion has been polarized regarding the film’s political implications, bifurcating in accordance with the lines along which people have interpreted its ideological content. Some have read Oppenheimer as an indictment of its titular character, typically praising the film for not shying away from the physicist’s personal shortcomings (like his arrogance or infidelity) or attempting to justify them.

For them, the film also shows Robert’s complicity in the most devastating war crime ever committed by foregrounding such details as his justification for continuing the Manhattan Project post-Hitler’s suicide and his refusal to sign Leo Szilard’s petition against dropping the bombs on Japan. Another strand of popular discourse, however, has gone the other way and accused Nolan of whitewashing the image of J. Robert Oppenheimer by de-emphasizing the horrific outcomes of his actions (such as by keeping the harrowing images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki offscreen) and portraying him as skeptical when it comes to atomic weaponry by glossing over his moral culpability in making them possible.

For this latter camp, the film’s decision to utilize Oppenheimer’s victimization at the hands of the Gray board as a framing device to bookend the narrative meant a shift in perspective from ‘Oppenheimer as perpetrator’ to ‘Oppenheimer as victim.’ For still others, the film has seemed to be a balancing act between these two contradictory tendencies, with the criticism and the sympathy canceling each other out to varying effect: for some, a fair representation of a complicated historical figure, while for others, a politically-toothless blockbuster looking to cover all bases.

Despite the differences between these positions, the common axis around which they revolve concerns a moral assessment of Oppenheimer as an individual, both as a man sustaining frayed personal relationships and as the physicist who made nuclear warfare possible. The film gets read merely as an exploration of Oppenheimer’s guilt, with opinions differing as to the success or failure of the depiction. The questions implicitly posed by such discourse tend to be of the following type: How are we to think of Oppenheimer and his legacy more than eight decades after the inception of the Manhattan Project? How should history judge this complicated figure, and what lessons could we draw regarding brilliant (but flawed) individuals occupying positions of power during times of global crisis?

Such considerations, while valuable, nevertheless seem too restricted to the level of the individual and inevitably miss the most crucial point to be derived from Oppenheimer, one underscored by its closing scene involving an ominous exchange between Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) and Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. “When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world,” says Robert, recalling a previous meeting between them.

Einstein confirms that he remembers the meeting well, and then Oppenheimer’s spine-chilling follow-up comes: “I believe we did.” The film ends with a montage of nuclear warheads launched, eventually engulfing the planet and triggering atmospheric ignition, cross-cutting with grief-stricken close-ups of Cillian Murphy’s face. Of course, Oppenheimer doesn’t refer here to having started an actual nuclear reaction and set fire to the atmosphere, which was the genuine worry at hand during his prior meeting with Einstein. Instead, he draws a revealing parallel between nuclear weapons and the scientific-military-industrial complex that facilitates them by analogizing the chain reaction that characterizes them both–forever threatening to spiral out of control with catastrophic consequences.

In these final images of the film, the fear and grief writ large on Oppenheimer’s face thus have little to do with either atmospheric ignition or even the specific dangers posed by nuclear weaponry. They reflect, instead, his confrontation with a final revelation – one that comes perhaps too late in his own life. It’s an acknowledgment of the tragic course taken by scientific reason in general (“the culmination of three centuries of physics,” as his colleague Isidor Rabi put it), which seems to lead inevitably to a paradox through its weaponization. The grand institution of science and technology, long heralded as the flagbearer of enlightenment rationality and progress, seems to produce scenarios that violently contradict its own utopian ambitions with the existential threats it generates.

The more pertinent questions raised by the film then become the following: How come “three centuries of physics” ultimately lead to a paradoxical scenario where its progress becomes the foundation for an existential threat, despite peerless geniuses like Oppenheimer and Einstein being fully cognizant of such dangers? And what does this indicate regarding our pursuit of technological progress itself, usually widely accepted as an unquestioned universal good? This essay shall probe such questions through a reading of Oppenheimer, which aims to bring forth and examine these fundamental contradictions (mirrored by the film’s contradictory characterization of Oppenheimer himself) and thus interpret the film as an alarming representation of the tragedy afflicting the very heart of our project of scientific-technological modernity.

The Tragic Subject of Oppenheimer

As the film opens with Oppenheimer reading his statement to the members of the Gray board security hearing, the first introduction we get to this character is through a flashback to his days spent at Cambridge, where he attempts to poison his tutor Patrick Blackett (James D’Arcy) with a cyanide-laced apple after being antagonized for his subpar laboratory work. This early instance of a young Robert responding under duress and lacking control over a situation almost instinctively with the urge to kill seems to foreshadow his eventual historical legacy–as the man fated to spearhead the single most violent act of death and destruction in human memory.

It’s tempting to read this sign as indicative of the ‘tragic flaw’ within Oppenheimer, which, despite his best intentions, sets him down a dark, winding path and ultimately becomes his undoing. But, as we shall see, such attempts to locate the roots of tragedy within Oppenheimer, arising from his personal attributes, would be to misrecognize how the tragic element manifests across the film’s narrative.

As per the classic Aristotelian theory of tragedy, hamartia (most commonly translated as ‘tragic flaw’) is responsible for the series of events affecting a movement from a state of felicity to disaster for the tragic hero, bringing about their downfall. Traditionally, hamartia has been understood to be some inherent character defect that gets in the way of the (otherwise virtuous) hero’s attempts to retain control over their fate and, as such, the possibility of depicting the downfall of a wholly virtuous (or villainous) character, as tragedy, was ruled out.

Later critics like Jules Brody have contested this interpretation of hamartia and insisted that it be understood as a morally neutral term, indicating a chance accident. It’s deemed an unforced error that leads the hero to ‘miss the mark’ (literal translation of the verb hamartanein). Like an archer inadvertently missing their mark, not due to lack of trying or inherent moral deficiency, tragedy manifests as a contingency that unalterably sets the course towards downfall. As opposed to the classical notion, this interpretation of hamartia emphasizes its externality and autonomy relative to the character: tragedy, in this vein, is that which strikes not because one is inherently flawed (for then their downfall is merely the comeuppance they already deserved) but due to something that lies radically outside the bounds of one’s will.

However, neither of these two interpretations of hamartia fits the tragedy of Oppenheimer, for they oscillate between locating it either entirely within the character or entirely without them while positing the character’s actions as the site where the tragic element takes root. To take the classic example of Oedipus Rex, where Oedipus fails to recognize his father Laius at the crossroads and kills him, the tragic error is attributed either to Oedipus’ hasty behavior because of his hubris (as per the classical notion) or to sheer bad fortune. But in both cases, it’s something that Oedipus (and Oedipus alone) does that actualizes the tragedy.

In both cases, Oedipus’ actions evince regret in him, and if he could’ve gone back in time and done things differently, it’s clear that he would’ve avoided slaying the man he meets at the crossroads. This isn’t true, however, for Oppenheimer. As the character of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) reminds us, Robert never once admitted to having regrets over Hiroshima and that “if he could do it all over, he would do it all the same.” Admittedly, the latter claim isn’t a factual observation but something that Strauss rhetorically puts forth to make his case against Robert. Still, it does lead one to wonder: What precisely could Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer have done differently, had he the chance to turn the clock back, so as to effect any different outcome?

He certainly couldn’t have stopped the nuclear race from ever starting, for that becomes inevitable the moment the atom is split by scientists in Nazi Germany and, a year later, World War II breaks out. Perhaps he could’ve more strongly opposed the decision to bomb Japan. Yet this argument misses the fact that the hindsight with which we now assert that the Japanese surrender wasn’t due to the bombs but rather the USSR’s entry into the war on 9th August 1945, was not something that was prophetically available to Oppenheimer who, like his fellow scientists, could only act based on information fed to him by the US military. Further, it is known that Generals Eisenhower and MacArthur, and even Truman’s chief of staff Leahy, went on record to condemn the atomic bombs as “either militarily unnecessary, morally reprehensible, or both,” and yet Truman went ahead anyway.

It’s fair to say that a “humble physicist” like Oppenheimer, especially with his personal “questionable associations,” could have done little to sway Truman. This isn’t to absolve Oppenheimer of all personal responsibility or claim that he always acted ideally. But it is to assert that the question of the violent trajectory taken by scientific rationality–culminating in nuclear weaponry but certainly not restricted to the bombings in Japan–cannot simply be reduced to the individual decisions taken (or not) by Oppenheimer (and other scientists like him), regardless of whether these decisions were motivated by inherent tragic flaws or brought about by chance circumstances.

We thus note how the existing notions of hamartia are ill-equipped to adequately account for the tragedy of Oppenheimer and preclude the possibility of deriving a politicized critique: the classical notion attributes all responsibility to the individual afflicted by the tragic flaw. In contrast, the latter notion leaves it all to accident. What’s necessary here is a way of configuring hamartia that situates it neither entirely within a character nor without them. Instead, it accounts for the dialectical relationship between inner subjectivity (acting upon outer reality) and external structures (determining and constraining the subject from within).

After all, the ‘tragic flaw’ manifests as most tragic precisely when it appears to be located within, leading us to proclaim the character as inherently flawed, even as its ultimate genesis lies elsewhere. Hamartia, in this case, must thus be located as being extimate to the character – deriving from the Lacanian concept of “extimacy,” a portmanteau of the two mutually contradictory words “external” and “intimacy.” Extimacy refers to a dissolution of the usual demarcation between interior and exterior and thus reframes the question of hamartia – no longer understood as some moral deficiency but rather as a mode of subjectivity volitionally adopted by the character as their own, but which nevertheless is founded in the external structure that produces the subject.

To view the ‘tragic flaw’ in the narrative as extimate to Oppenheimer is to insist that it operates through him, even as its origins remain radically outside him. As shall be discussed in the next section, this shows up in the film as Robert’s significant psychical investment in Enlightenment-era rationality–as embodied in the ideals of scientific progressivism and bureaucratic due diligence–a structure of which he is a product through and through. As the film unfolds, this structure unravels for Oppenheimer to reveal at its heart a gnawing irrationality, manifesting through his often contradictory behavior as well as the rising sense of a loss of control (which Einstein also brings up in the final scene) and the tragic realization of his own helplessness in the face of it all.

Enlightenment and its Discontents

Regardless of the wide variety of opinions out there regarding Oppenheimer, there seems to be a near-universal agreement in describing him as a deeply contradictory character, something that Nolan’s film also evokes in numerous ways. Edward Teller’s (Benny Safdie) testimony of Robert’s actions as “confused and complicated” may not have been entirely fictional, and we see how the Gray board leverages the apparent contradictions in Oppenheimer’s behavior (like his shifting position with respect to the H-bomb) to persecute him.

Additionally, Robert often behaves in ways that undermine his personal position, like admitting to prosecutor Roger Robb (Jason Clarke) that the communist Haakon Chevalier (Jefferson Hall) is still his friend. We also see him arguing more than once that the scientists’ role as creators of the bomb does not give them any greater right to dictate whether it’s used, even as we see him doing precisely the same while convincing his colleagues of the need to unleash the bomb despite Nazism no longer being a threat.

Oppenheimer’s contradictions can only be fathomed if we first recognize that he’s a Kantian liberal subject through and through, implicitly following the rational framework elaborated by Immanuel Kant in his seminal essay “What is Enlightenment?”. The path to Enlightenment, Kant wrote, lay in maintaining a clear separation between private and public uses of reason and in having a state form that freely allowed the maximization of both. Put simply, the difference is as follows: private use of reason refers to executing one’s assigned duties in the specific role (teacher/scientist/lawyer/banker, etc.) one occupies within civil society, whereas public reason refers to performing one’s greater duty towards society as a whole, i.e., by speaking out and protesting, according to one’s convictions, against that which threatens the so-called “common good.”

With the one hand, you oil the wheel that turns (for that is your job), and with the other, you mend the spokes that are broken –this seems to be the model of Enlightenment rationality that also governs Oppenheimer. “Argue as much as you like and about whatever you like, but obey!” wrote Kant, his blueprint acting as an injunction to people to speak out against the status quo as and when necessary, but not at the cost of neglecting their duties (for without the latter, society itself would break down).

One clearly sees this tension between ‘arguing’ and ‘obeying’ play out in the film through (among other things) Oppenheimer’s engagement with the communists, neither officially joining them nor entirely giving up on their cause. Oppenheimer is quick to ‘argue’ alongside his fellow members of the F.A.E.C.T when it comes to showing solidarity with “farm laborers and dock workers” and insisting that “academics have rights too.”

He is also quick to ‘obey’ when Lawrence (Josh Hartnett) convinces him of the need to tone down his political activity so that he can do his duty, showing the ability to be “pragmatic.” It’s fascinating to see how Robert goes out of his way to inform the authorities about Eltenton (Guy Burnet) because it’s his duty as a law-abiding citizen to report espionage attempts. Yet, he also resists the persistent Colonel Pash (Casey Affleck) to keep Chevalier’s name concealed, spinning lies that would return to hurt him later.

In fact, Robert’s lifelong commitment to ‘arguing,’ i.e., not letting the exigencies of private ends trammel over public reason, is precisely what separates him from Lewis Strauss, whose perspective is taken up in the parallelly-running storyline shot in black and white. While Strauss has spent his whole life climbing the social ladder by greasing the right palms and pleasing the right people, Oppenheimer, in contrast, was (in)famous for speaking his mind (almost to the extent of seeming arrogant) and standing up for causes he believed in, regardless of potential political backlash.

It’s telling that when the senate aide (Alden Ehrenreich) was pushing the question of who targeted Oppenheimer and why, Strauss mentions that “Robert didn’t take care not to upset the power brokers in Washington” (which undoubtedly Strauss always took care to), before recounting the tale of his humiliation in the case of exporting isotopes to Norway. Oppenheimer’s real ‘crime,’ for which Strauss takes it upon himself to punish him, lay in this insistence on always keeping private and public reason separate and for not backing down on his stance against further nuclear armament or paying enough importance to influential individuals to bow to them. His folly, perhaps, lay in thinking that the state structure was rational enough to tolerate the same.

Underlying this two-pronged mode of rationality that Oppenheimer embodied is the assumption that the exercise of reason can act as it’s own corrective, i.e., the threat of rationality leading us into error and excess is countered by rationality itself, in recognizing such dangers and undertaking appropriately rational countermeasures. Yet this would be to presume a state form that also functions rationally, where private and public uses of reason can be kept separate, which is only possible in an age of globalization under the aegis of something akin to “world government” as Lewis Strauss puts it in the film, which Oppenheimer imagines functioning through “the United Nations as Roosevelt intended.”

However, nearly two centuries after Kant, the world in which Oppenheimer finds himself is ruled by division and strife, where the imagined separation between private and public usage of reason often collapses – such as when it becomes the very duty of scientists to help fashion weapons of mass destruction, which contradicts their greater responsibility as rational agents to society at large. The Kantian model presupposes a state form that allows for both obedience and argument and thus leads to contradiction in situations where argument itself amounts to disobedience, like when Oppenheimer’s continued opposition to the H-bomb project is framed as a betrayal of his patriotic duties.

Nolan’s film shows us how nation-states’ fractured and warring imaginaries constantly undermine the promises of Enlightenment rationality – promises of scientific progress and peaceful prosperity – both on micro and macro scales. One of the dominant antagonisms staged throughout the film is between the US military’s policy of compartmentalization and the values of transparency and open communication that are key to the institution of science. “All minds have to see the whole task to contribute efficiently,” as Oppenheimer tells General Groves (Matt Damon), which really applies not just to the scientists working at Los Alamos but also to humankind in general, engaged in the Enlightenment project of reaping the benefits of scientific progress while protecting against its dangers. All humanity, setting aside mutual differences, must together see to dangers that threaten us on a planetary scale, whether nuclear bombs or the worry of climate change.

The essence of compartmentalization, which lies in damming the tendency of knowledge and information to circulate freely, shows itself to be irrational insofar as it seeks only to further private interests (in Oppenheimer’s case, that of the US military) at the cost of public ones. As Oppenheimer discovers, to his great horror, his hopes of international cooperation preventing the nuclear race from spiraling out of control seem utterly fanciful given the utmost hostility between the two world superpowers. The contradiction is made explicit with great force in the scene where Oppenheimer meets President Truman (Gary Oldman). He assures the President that the Soviets, too, have abundant resources to build a nuclear arsenal, hoping his reasoning sufficiently convinces the President to shut down Los Alamos and enter arms talks with the USSR.

In response, Truman’s Secretary of State James Byrnes (Pat Skipper) takes Robert’s observation to conclude the exact opposite, arguing that the USSR’s nuclear potential means that they have to “build up Los Alamos, not shut it down,” which shows how incompatible Oppenheimer’s rationality is within such a fundamentally irrational state. At this moment, Robert realizes the error he has been led to with his investment in Kantian rationality, its inherent contradictions growing steadily apparent, as he remarks to the President, “I feel like I have blood on my hands.” It’s one thing to imagine this blood to be representative of the deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, massacres which (as previously discussed) Oppenheimer wasn’t entirely responsible for and nor could have prevented singlehandedly.

But insofar as the line follows Byrnes’ conclusion, the blood on Oppenheimer’s hands should indicate something far ominous: that is, his involvement within the institution of science and technology – itself a part of the greater Enlightenment project of modernity – leading to a scenario where he has given humankind “the power to destroy themselves,” as Neils Bohr (Kenneth Branagh) puts it. The idea of Enlightenment, a word referring to the state of being illuminated, of the production of light to cast out darkness, thus attains perversion in the spectacle of the atomic explosion–popularly held to be “brighter than a thousand suns”– which paradoxically for Oppenheimer back then also necessarily represented the zenith of scientific progress that he had helped reach.

Technology as Revelation

That the zenith of scientific progress should appear as an act of bringing to light in Oppenheimer perhaps hints at something of the essence of this act of putting science into use, of “taking theory and turning it into a practical weapons system,” as Robert tells Groves. For the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, the essence of technology lay in revelation–understood as the movement from a state of concealment to unconcealment. “Technology is a mode of revealing,” wrote Heidegger in his essay “The Question Concerning Technology,” referring to how science apprehends the natural world to bring forth what would have eluded us otherwise.

We need only think of some of the earliest examples of human technology to get the point across: the harnessing of fire, for example, reveals the nutritional value concealed within plants and animals to be used as sustenance, while the plow that turns the earth reveals the fertility of the soil that’s otherwise inaccessible. It was crucial for Heidegger that we do not fall into the usual trap of imagining technology as something neutral in itself, as merely instrumental means to ends, its purpose defined entirely by how humans use it. To imagine technologies as disparate as the windmill and the atomic bomb as mere instruments at the mercy of humans, while not technically incorrect, reduces them to a false equivalency that obscures their vastly differing essences.

More importantly, it obscures their telos, i.e., their ultimate (intended) purpose, which must also be held responsible for their creation in the first place, for no one imagines that the telos driving the manufacture of windmills and atomic bombs to be anything similar. Thus, for Heidegger, it’s important that we apprehend technology’s essence as ‘revelation’ so that we may better appreciate how the technologies we use constrain (and are constrained by) the realities they bring forth. Revelation in this manner, for Heidegger, thus involves a “bringing-forth,” i.e., something is brought forth from obscurity and into sight. The windmill, for example, can tap into currents of air and bring forth the same as electrical currents, which can then be harnessed as electricity.

The idea of technology as a mode of revealing is acknowledged most directly in Oppenheimer during the scene where Secretary of War Henry Stimson (James Remar) discusses dropping the bomb on Japanese cities, and Robert describes it as “a terrible revelation of divine power.” That the bomb’s power is defined as divine (god-like and thus not of the world of humans) is, of course, no mere coincidence, and harks back to the now-infamous line from the Bhagavad Gita quoted by Oppenheimer, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” typically misunderstood to imply Robert’s identification with the figure of death, given his role in pioneering the atomic bomb.

In the Gita, however, it is told to Arjuna by Krishna, the latter taking on the form of Vishnu’s multi-armed self and thus refers to a moment of identification between death and divinity. Death appears to Arjuna in the form of Vishnu (and to Oppenheimer in the form of the atomic explosion) as something terribly divine, something so otherworldly that he, a mere mortal, cannot possibly hope to comprehend or control it. Later, following the Hiroshima bombing, we hear Truman on the radio describe the bomb as “a harnessing of the basic powers of the universe.” Read together, the technology of the atomic bomb can thus be described as a harnessing of the basic powers of the universe so as to effect a revelation of divine power.

The paradox becomes apparent: what’s harnessed is that which belongs to the fundaments of this world, even as what’s revealed feels like something otherworldly (transcending the limits of the human) – as if to imply the presence of the otherworldly (albeit concealed) within the very building blocks of our reality. Once again, we have here a relation of “extimacy,” in that technology takes the base matter of our world (its natural resources and the physical laws governing them) and contrives it to reveal something that appears external to us insofar as it threatens to exterminate the world.

It is this trait of modern technology, as seen most visibly in atomic bombs but certainly not limited to them, to ultimately objectify its subjects (i.e., human beings), becoming external and even opposed to them concerns Heidegger. He characterizes the logic governing modern tech as a “challenging-forth,” a “setting-upon,” that separates it from older technology where the revelation involved was merely a “bringing-forth.” He contrasts the windmill, which simply taps into air currents already flowing, with the modern activity of coal mining: “. . . a tract of land is challenged in the hauling out of coal and ore.

The earth now reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit”. The difference between the windmill’s “bringing-forth” and the coal miner’s “challenging-forth” is that the former resembles receiving gifts from Mother Nature doled out generously. At the same time, the latter is active exploitation of nature, motivated by the single capitalist logic of “maximum yield at minimum expense.”

Revelation as “challenging-forth” thus affects a pretty different kind of unconcealment that Heidegger describes: “Everywhere everything is ordered to stand by, to be immediately on hand, indeed to stand there just so that it may be on call for a further ordering. Whatever is ordered about in this way has its own standing. We call it the standing-reserve”. The phrase derives from the idea of standing armies forming the military reserve forces. It refers to a peculiar ordering of natural elements wherein they stand by, at hand, and ready for use instead of being freely scattered within the world in their natural forms.

Oppenheimer neatly illustrates the idea through the recurring imagery of spherical glass bowls being gradually filled with marbles, representing increasing quantities of refined uranium and plutonium, standing by, ready to be used as fissile material. This process represents how science and technology reveal the contents of our world as mere means, as things to be used to achieve our desired ends, and not as ends in themselves. The logic of technology subjects humans to a view of the natural world as something that exists only for the purpose of being harnessed for profit, overriding the idea of its existence in its own right.

The problem with this logic of turning nature into the “standing-reserve” is, of course, that eventually, it extends to humans themselves – humans who, as part of the same natural world, are also made part of the “standing-reserve” of science and technology. “The current talk about human resources, about the supply of patients for a clinic, gives evidence of this,” writes Heidegger. It is to effect a depreciation in the value assigned to humanity itself. It marks that moment wherein technological revelation starts appearing as something external to humanity – external insofar as technology now seems turned against humans themselves and thus out of their control. Indeed, that is how the “terrible revelation of divine power” must have appeared to the hundreds of thousands massacred at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, who became mere fodder for imperialist war games and who tellingly don’t appear in Oppenheimer except in the form of mere statistics.

Modern technology, thus, as a form of revealing that “challenges-forth” and turns nature into the “standing-reserve”, contains within itself a paradox: As humans keep utilizing scientific knowledge to exploit the natural world for profit and using the profit to further its technologies to better exploit nature (not unlike a chain reaction), eventually the logic of natural exploitation – now magnified manifold – threatens to engulf humankind itself.

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of Oppenheimer is the realization that this existential threat is not well appreciated until it gets displayed in some form, as when Robert justifies continuing the Manhattan Project despite Hitler’s death, claiming this would encourage deterrence. By insisting that “they won’t fear it until they understand it, and they won’t understand it until they’ve used it,” Oppenheimer directly invokes the logic of revelation–for if technology is a mode of revealing, as Heidegger insists, it seems like the culmination of technological progress must consist in the revelation of its own catastrophic potential, so that we may learn to curb the same before it’s too late.

Oppenheimer beyond Oppenheimer

In an interview about the film, Oppenheimer’s co-producer Emma Thomas describes it as a “cautionary tale,” hoping it leaves viewers with more troubling questions than straightforward answers. But it’s hard to see how Oppenheimer can function as a cautionary tale as long as the discourse around it centers on an assessment of Oppenheimer himself and the story of his moral culpability and guilt. Understandably, popular opinion has fixated upon the depiction of the individual more so than anything else, given that Oppenheimer has been marketed as a biopic. Additionally, the buzz around Nolan’s decision to write his screenplay in the first person so as to tell the story from Oppenheimer’s subjective perspective undoubtedly contributed to prejudice regarding the film’s ambitions, shifting the focus to the man himself rather than the story unfolding around him.

But what this decision does for the film is actually quite the opposite, i.e., by locking the viewer onto Oppenheimer’s perspective, the film eschews a moral judgment of Oppenheimer himself (for that requires us to view him objectively). It encourages a questioning of the structures that made this tragedy possible. In watching the film, the audience is made to feel like “we’re on this ride with Oppenheimer” (as Nolan put it), and this formal identification with the protagonist dissuades attempts to make it all about him, as has primarily been the case with previous attempts at telling the story of the atomic bomb. The idea isn’t dissimilar to the proverbial walking of a mile in someone else’s shoes, which indicates a movement away from making that person the sole object of one’s critique.

It is here that popular discourse around the film, centering on a moral judgment of Oppenheimer and his guilt, falls short: the more significant point alluded to by the film’s closing moments isn’t about whether Oppenheimer was the devil for having commandeered the Manhattan Project to success or a saint for advocating arms control. It certainly isn’t about the role of individual responsibility in overseeing projects of seismic importance (as if a different set of personnel could’ve ensured a different historical outcome). It’s easy enough to investigate some tragic event and have the buck stop with some individual figure to arrive at some scapegoat upon whom responsibility is pinned in order to be relieved of the labor necessary to interrogate systemic factors that keep reproducing such tragedies.

To the extent that Oppenheimer portrays its titular character as flawed, it’s also careful to show us that Robert himself was acutely aware of his flaws and felt remorseful. And as his friend Chevalier notes: “Selfish and awful people don’t know they are selfish and awful.” But it’s precisely by presenting this sympathetic portrayal of the man Oppenheimer that the film encourages a more careful reading of his position within the scientific-bureaucratic apparatus, one that transcends individual specificities, suggesting a sense of fatality with which the events of the movie are tainted and imploring us to derive a critique of this apparatus itself.

Of course, the film is about Oppenheimer’s life and work and depicts the same in detail, but this focus on the man himself is not an end in itself but merely the means to get beyond the man and explore what made, drove and ultimately tormented him. Paradoxical as it may sound, given the film’s text, the title of Oppenheimer may be less of a reference to the famous physicist himself and more of an indication of the historical subject position that was once occupied by Robert but now endures despite him.

In numerous interviews, Nolan has mentioned how scientists working in AI often refer to the current AI explosion as their ‘Oppenheimer moment.’ In revisiting and rethinking the story of the nuclear bomb, perhaps it’s time that we stopped obsessing over what Oppenheimer could or should have done differently and instead broach the question of how such ‘Oppenheimer moments’ arise in the first place and how to tackle them. How come new developments in science and technology often strike us with fear and alarm when we should be rejoicing in the potential benefits they could bring us all? How come when news of developments in computerization, automation, and AI technologies hit the stands, the popular reaction is often one of dismay, stemming from fears of losing livelihoods rather than one of celebration?

“Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man; for this, he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity,” the movie’s opening frames inform us. Going by the film’s narrative, it’s easy to imagine that this refers to Oppenheimer’s persecution by the Gray Board under the animus of Lewis Strauss. But Prometheus was punished by the gods from whom he stole fire, not by men. Neither was Prometheus punished for regretting and having hopes of going back on his act, which happens in the case of Oppenheimer and the bomb. So, the ‘torture’ referred to in the quote has nothing to do with the tarring and feathering Oppenheimer undergoes throughout the film, culminating in him losing his security clearance for trying to minimize the fallout from his invention.

Instead, the idea of ‘stealing fire from gods’ in Oppenheimer’s case refers instead to the laws of physics and their harnessing by the institution of science and technology, which gives men such terribly divine powers as the atomic bomb. Being tortured for eternity, then, in this case, means living with the horror and fear that our technological progress can, at any moment, become our undoing. “Chances are near zero,” as we are told repeatedly, but that doesn’t stop Fermi from taking side bets on atmospheric ignition. It is this element of non-zero chance, this uncertainty that paradoxically (re)appears at the end of a long process of scientific inquiry and development based on values of certitude, that strikes as most tragic – that the hallowed project of gaining control over the natural world for human benefit has led to a real possibility of loss of control and human extinction.

In the film, Einstein astutely notes this to be a trait characterizing the “new physics” when Robert first comes to him with Teller’s troubling calculations, observing how they are “lost in your (i.e., Oppenheimer’s) quantum world of probabilities, and needing certainty.” But of course, it isn’t as if quantum mechanics itself introduces uncertainties into our world so as to destabilize it; rather, quantum mechanics – itself the culmination of “three centuries of physics”– only reveals the uncertainties that have long inhered in the world and in the scientific project itself, but which so far have remained concealed. Small wonder then that Bohr’s character insists that what they have is not just a new weapon but a new world.

Thus, rather than deriving a critique of Oppenheimer himself, a man long dead and gone, a far more fascinating and important discussion to be had from Nolan’s Oppenheimer would be regarding the ‘criticality’ of scientific reason itself. The notion of criticality, as used in the film, refers to that stage during which a nuclear chain reaction becomes self-sustaining, beyond which it becomes ‘supercritical’ and proceeds towards explosion. The institution of science in today’s world is similarly self-sustaining insofar as its narrative of technological progress requires no additional justification, insofar as even our response to science’s dangers usually tends to be more science.

Like a chain reaction, scientific progress feeds capital, which in turn feeds science and so on – a juggernaut advancing so autonomously as to almost be insulated against external criticism and the possibility of applying brakes. And carrying with it, all the time, the risk of ‘supercriticality’ – from CO2 emissions causing global warming to developments in AI causing job losses or worse, and so on. It’s precisely this tragic course of events, from rationality and control to irrationality and loss of control, irreducible to the individual and instead requiring deeper systemic interrogation of the fundamental assumptions underlying technological modernity, that Oppenheimer allegorizes in its tale of the atomic bomb and the man who fathered it.

The film lays bare the irrationality at the heart of the Enlightenment project of scientific progress and the paradoxes it leads to, mirrored by the paradoxes of the quantum world and manifesting in Oppenheimer’s contradictory subjectivity and the final tragic realization that despite his crucial role in the making of the bomb there was perhaps very little he alone could have done to change the course of history, a history that through his participation he also helps actualize.'

#Oppeneimer#AI#Emma Thomas#Albert Einstein#Christopher Nolan#The Manhattan Project#Leo Szilard#Cillian Murphy#Tom Conti#Institute for Advanced Study#Princeton#Isidor Rabi#Gray Board#Patrick Blackett#James D'Arcy#Lewis Strauss#Robert Downey Jr.#Edward Teller#Benny Safdie#Haakon Chevalier#Jefferson Hall#Roger Robb#Jason Clarke#Ernest Lawrence#Josh Hartnett#Boris Pash#Casey Affleck#George Eltenton#Guy Burnet#Alden Ehrenreich

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

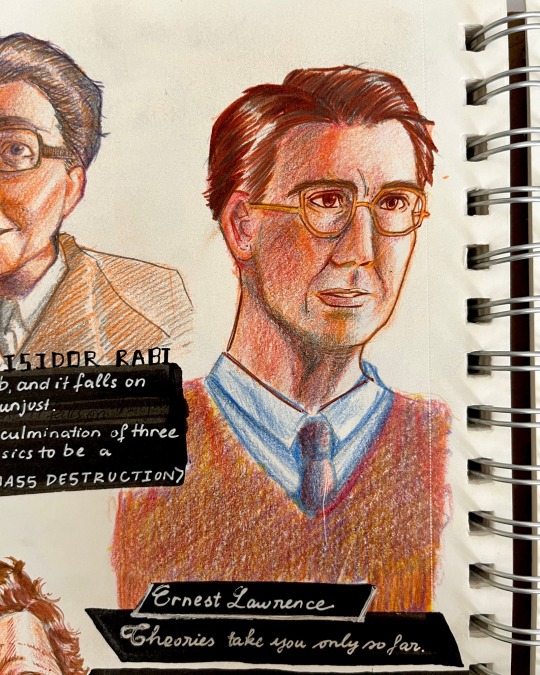

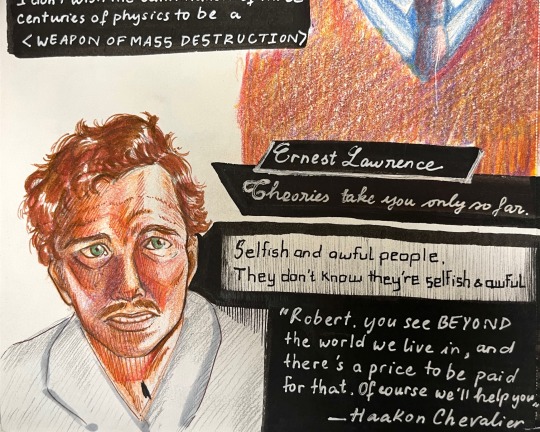

Daily warm-ups but make it Oppenheimer characters ✨Day 2✨

You’ll get two types of friend in your life:

a pragmatic friend whom you share a love-hate relationship with

‘Theories take you only so far’

— Ernest Lawrence

played by Josh Hartnett

Oppenheimer: But why would they care what I do?

Lawrence: Because you’re not just self-important. You’re actually important.

and an empathetic one without whom you’d probably die in a ditch somewhere.

Oppenheimer: We are awful people. Selfish and awful people.

Chevalier: Selfish and awful people, they don’t know they’re selfish and awful.

Robert, you see BEYOND the world we live in, and there is a price to be paid for that. Of course we will help you.

— Haakon Chevalier

played by Jefferson Hall

IMDb really should update their quotes for Chevalier bc both of these are so definitive in Oppie’s character growth.

#daily sketch#sketch#scribbles#morning warm ups#Oppenheimer#ernest lawrence#haakon chevalier#there’s so many good quotes in this movie wtf#josh hartnett#jefferson hall

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

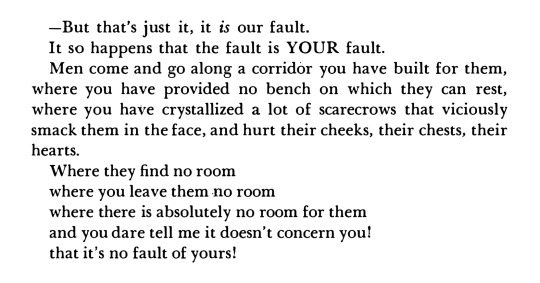

from "toward the african revolution," frantz fanon (trans. haakon chevalier) 🤍

1 note

·

View note

Text

Their two wives were present, and the talk mainly concerned family and mutual friends.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quote#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#haakon chevalier#barbara lansburgh#katherine puening#j robert oppenheimer#small talk#family#mutual friends

1 note

·

View note

Text

Chemical Reactions (P. 5)

Pairing: Cillian Murphy as J Robert Oppenheimer x Student Reader

Warning: Mild Smut, Age-Gap, Infidelity

Words: 2,406

Note: The fic is spoiler free and my own fantasy and imagination. It is not historically and scientifically accurate.

Previous Parts: 1; 2; 3; 4

It was six o’clock on Sunday evening and, just as discussed with your professor a few days ago when he startled you inside the chemistry lab, you were waiting for him to arrive at the Chevalier residence.

Haakon Chevalier and his wife were away for the weekend and you did not expect them to return until tomorrow which is why you believed the timing for your mentoring session to be just perfect. Unlike usual, you made an effort tonight, just in case your professor wanted to stay and explore more than just quantum physics and the collapse of stars and supernovas, which was something that was of particular interest to you when it came to your thesis. You wanted to expand on J Robert Oppenheimer’s very own theory and this was exactly why he became your mentor.

Yet, you wanted him to be more than just that as, at least to you, J Robert Oppenheimer was the most handsome man you had ever seen with his dark hair and his blue eyes, full lips and sharp cheekbones. J Robert Oppenheimer was mature and incredibly intelligent and it was his intellect that turned you on the most. He was smarter than anyone else you had ever met before and you felt as though he understood your intellectual needs and desires just perfectly.

Thus, you stiffened in your chair just by thinking of him and his impending arrival at the Chevalier residence. A mix of dread and desire washed over you and, eventually, you stood up and smoothed down your dress and walked to the bathroom.

You flipped on the light and looked in the mirror before fingering your hair. Your eyes were big and dark, dark lashes curled up with a subtle shimmer painted across your eyelids, matching the simple black dress you were wearing.

It made you look older and more mature and you hoped that Dr Oppenheimer would appreciate it, seeing that you looked elegant but not inappropriately suggestive.

When you were done looking yourself over, you walked downstairs again like a nervous chicken, carrying a few physics books in your hands which you knew you would need in order to discuss your very own theory with him.

You knew that you had to be prepared and prepared you were when, finally, you heard a knock on the door.

“Dr Oppenheimer, please come in” you said after, without wearing any shoes or stockings, you tippy toed towards the door.

“I can see that you have already prepared your paperwork, so we shall get started right away, yes?” Dr Oppenheimer asked, skipping any kind of small talk and cutting straight to the point.

“Yes, perhaps we should, although I was going to offer you a drink first as, no doubt, you had a rather busy and demanding week” you suggested while looking at him and his deep blue eyes which, so seemingly, followed you as you walked across the room barefooted.

“I suppose I could have one drink” Dr Oppenheimer said, falling into your gaze for a short moment, before you forced yourself to look away. You tried hard to take him all in as he took off his hat and suit jacket, but you simply could not. It was way too difficult for you to do so without blushing.

“Wine or gin?” you then asked, although you already knew the answer and had the gin bottle opened before he could respond.

“Gin, please” he confirmed before he dropped his books on to the coffee table as well and sat down on one of the rather soft and comfortable armchairs.

“Alright, gin it is” you said while pouring two glasses and later carrying them over towards where he was sitting before throwing one of the larger pillows onto the rug beneath your feet and kneeling on top of it.

“Should I join you down there?” Dr Oppenheimer then asked with amusement, seeing that you chose to sit on a pillow on the floor rather than on the large sofa behind you.

“If you like. It’s just a silly habit of mine” you pointed out as you opened one of the books that you had placed on top of the large coffee table earlier that night.

“Alright. I suppose the comfort of upholstery is highly overrated” Dr Oppenheimer responded sarcastically before slipping off his shoes, throwing another pillow onto the floor and joining you by sitting down right by your side.

“It sure is, professor” you chuckled before showing him the sheets that you had prepared and, just as you gave him your workbook, your hands touched briefly, resulting yet in another tingle on your skin.

"Well, let's figure out where you are at and what we need to work on” Dr Oppenheimer told you while taking a pen from the stash of pens you had left on the table and reading through your calculations which, in his mind, appeared to be incomplete.

“Miss Y/LN, you seem to have omitted a few steps in your calculations” he then pointed out and, when you looked at your papers again, you realised that he was right. An entire sheet was missing and you did not know where you had put it.

“I am so sorry. I did write it all out but I must have left some of my notes at the lab last night when I was working with the reactor” you admitted with great embarrassment, causing Dr Oppenheimer to furrow his eyebrows and make a somewhat terrible suggestion.

“Can you replicate your calculations?” he asked and, by this point, panic had sat in.

“From memory?” you asked and when Dr Oppenheimer nodded, you nodded as well, telling him that you would try.

Unfortunatly for you though, as soon as you put pen to paper, you were lost. You were so completely lost that, by that time, you had forgotten that Dr Oppenheimer was even sitting there watching you and then you jumped when he touched the small of your back and told you to stop what you were doing.

"I'm sorry, I didn't mean to startle you..." he said while pointing at the problem you were facing and, just as he did, you locked eyes and you could not look away. It was as though he was peering into your soul, searching out your deepest secrets and desires. His pupils expanded as his iris contracted. The colours shifted through a spectrum of greys and blues and you were absolutely lost in his eyes.

“I can show you my calculations upstairs, in my bedroom. I did them before starting the experiment. The experiment confirmed some of my theory and the calculations I did earlier this week, except for formula three. Formula three changed and I can replicate this change. Come. I will show you” you then said suddenly and a little too abruptly after snapping out of your trance and your words startled Dr Oppenheimer as well.

"You want me to come upstairs, to your bedroom?” he asked somewhat surprised while furrowing his eyebrows again and you nodded.

“Yes. Come on” you said while noticing that his eyes were wandering to your breasts as you stood up and, just as they did, his chest flexed, either involuntarily or on purpose.

“Mhhm” Dr Oppenheimer then simply said, clearing his throat before standing up and following you upstairs, to your bedroom.

***

Seconds later, you reached your bedroom and when Dr Oppenheimer saw the large chalk board across from your bed, he was rather surprised.

In fact, he was surprised by the entirety of your bedroom which consisted of a small bed, three overfilled bookshelves, a small closet, and an oversized chalkboard, containing calculations on dark matter.

“This is one hell of a chalkboard” Dr Oppenheimer thus teased and you could not help but break out in laughter, seeing how awkward this was, standing in your bedroom with your professor.

“I only just realised how inappropriate it was for me to ask you to come to my bedroom. I am so sorry” you acknowledged while he stood there, totally engulfed by his own thoughts of stars exploding.

“Uh huh” he simply murmured while taking in what you are suggesting just as you amended formula three, replicating what you saw during your experiments in the lab.

“What you are suggesting is not the collapse of a star. It is the explosion of a star. There would have to be an ejection of most of its mass which is something that has to be visible” Dr Oppenheimer then said with his velvet smooth voice as he looked you right in the eyes.

“Yes, it would be visible, from space, but not necessarily from here. It depends entirely on the location of the star” you responded with some nervousness in your voice which is when Robert shifted closer towards you and you could feel the heat from his body beside you.

It was purely intoxicating and, if you were to lean in right now, you would have been able to kiss him. But, you only let that thought simmer for a moment before pushing it away, afraid to make the move which you wanted him to make so desperately.

“This hypothesis would change how we think about nuclear transformation” Robert eventually said and your cheeks became flushed as you tried to deflect on his statement, but your brain did not think so you blurted out a slightly whispered "maybe"..

“Maybe?” Robert chuckled. His smile grew big and his eyes began to search you, causing you to gulp.

“You should be more confident with your answer Miss Y/LN” Robert then said before leaning in slightly and bringing his hands up to gently touch your face.

“You are smart and intelligent. Your calculations seem to be correct and logical and your conclusions are impressive. Now you just have to prove your theory” Robert told you with a sense of affection and awe in his voice, to which you simply nodded again, unable to form words under the attraction that you were feeling towards this god-like man right now.

“You impressed me Y/N” Robert then pointed out, for the first time using your first name, as he moved one of his fingers to your lips, tracing an outline of them.

You gasped in response to his gentle touch while your body was vibrating for him. Your heart felt like it was beating out of your chest and you could hear the whooshing of blood as your body radiated from his touch.

“May I kiss you?” he then asked somewhat reluctantly himself as he leaned his face towards yours until his lips were almost touching your lips.

“Yes, please do” you gasped as you stopped breathing before, suddenly, you felt the anticipation of a teenage girl waiting for her crush to kiss her at a school dance.

Following your approval, Robert closed the gap between you, touching his lips to yours. He was slow at first, but then you become enveloped with passion and your hands reached for his hair and your tongue pushed through the barrier of his lips and reached its destination.

Your tongues became encompassed with a passionate dance and you moaned against his lips while slowly, but surely, losing control. Robert’s hands began to move from your face down to your arms, moving lower and lower until they were resting on your thighs as you were still locked in this passionate dance of mouths, only ever pausing to breathe.

Robert was a sensational kisser and just as he circled his tongue around yours his hands started moving up your thighs again slightly. Your body responded by begging them to move faster and then, all so suddenly, an unfamiliar heat began to form in your lower regions.

With that, you started to move a little and your hands became bolder and bolder as you continued to envelop each other mouths. You ran yours hands down Robert’s chest, teasing the fabric of his shirt before, finally, your hands moved lower as your fingers caught the edge of where his shirt met his belt.

You then started undoing one button after another, moving upwards one by one, praying that he would not resist and, sure enough, resistance was the last thing on Robert’s mind right now.

Eventually, while still kissing each other, you completed your task and his heat poured out as soon as the white fabric dropped to the floor, revealing his slim but incredible physique. You then began to touch him, running your hands down his chest and through the small patch of hair on his chest before feeling the taut muscle under your fingers.

As you were touching Robert gently, he moaned against your lips while, all at the same time, his fingers moved up until they were resting at the back of your dress, which is where Robert found the very top of your zipper.

As he slowly unzipped your dress, you began to moan louder, almost begging for him to touch you which is when slipped his fingers beneath the fabric and you gently pushed your garment down until your dress was caught by the outline of your hips.

This when you opened your eyes, breaking your kiss momentarily.

“I should let you know that I have not done this before” you stammered huskily against his lips as his hands caressed the skin now exposed on your back.

“What do you mean?” Robert asked as he held you close, never letting go of his embrace.

“I have not slept with anyone yet. Not with a man anyway. It just never eventuated” you admitted, causing Robert to clear his throat and withdraw.

“Then perhaps we should stop this right here. I am not the man for you” he pointed out and you reached for his hands, holding them in yours before bringing them back to your half-naked body.

“Why?” you asked huskily, wanting to continue you where you had left of.

“Because I will not be able to give you what you want” Robert determined but you shook your head and sighed.

“I haven’t told you what I want, so do you just presume to know?” you asked while rolling your eyes.

“I am married and I am not going to leave my wife” Robert said before withdrawing again and, for a brief moment, you stepped away from him and leaned back against the chalkboard with yet another sigh escaping your lips.

To be continued…

Please comment and engage. I love getting comments and predictions pretty please!

Tag List

@fastfan

@elenavampire21

@dolllol2405

@allie131313

@cilliansangel

@coldbastille

@kpopgirlbtssvt

@cdej6

@kathrinemelissa

@landlockedmermaid77

@crazymar15

@damedomino

@lauren-raines-x

@miss-bunny19

@skinny-bitch-juice

@odorinana

@cloudofdisney

@weepingstudentfishhorse

@allexiiisss

@geminiwolves

@letsstarsfalling

@ysmmsy

@chlorrox

@tommyshelbypb

@chocolatehalo

@music-lover911

@desperate-and-broken

@mysticaldeanvoidhorse

@peaky-cillian

@lelestrangerandunusualdeetz

@december16-1991

@captivatedbycillianmurphy

@romanogersendgame

@randomfangirl2718

@missymurphy1985

@peakyscillian

@lilymurphy03

@deefigs

@theflamecrystal

@livinginfantaxy

@rosey1981

@hanster1998

@fairypitou

@zozeebo

@kasaikawa

@littleweirdoalien

@sad-huffle-nerd

@theflamecrystal

@0ghostwriter0

@stylescanbeatmyback

@1-800-peakyblinders

@datewithgianni

@momoneymolife

@mcntsee

@janelongxox

@basiclassy

@being-worthy

@chaotic-bean-of-smolness

@margoo0

@vhscillian

@crazymar15

@im-constantly-fangirling

@namelesslosers

@littlewhiterose

@ttzamara

@cilleveryone

@peaky-cillian

@severewobblerlightdragon

@dolllol2405

@pkab

@babaohhhriley

@littleweirdoalien

@alreadybroken-ts

@masteroperator

@stevie75

@shabzy96

@rainbow12346

@obsessedwithfandomsx

@geeksareunique

@laysalespoir

@paigem00

@lkarls

@vamp-army

@luckystarme

@myjumper

@gxorg

@eline-1806

@goldenharrysworld

@cristinagronk16

@stylesofloki

@faatxma

@slut-for-matt-murdock

@tpwkstiles

@myjumper

@cloudofdisney

@look-at-the-soul

@smellyzcat

@kittycatcait219

@theliterarybeldam

@being-worthy

@layazul

@lyn07

@kagilmore

@50svibes

@mainstreetlilly

@ourthatgirlabby

@bitchwhytho

@takethee

@registerednursejackie

@sofi128

@mrkdvidal1989

@minxsblog

@heidimoreton

@laylasbunbunny

@laylasbunbunny

@queenshelby

@camilleholland89

@forgottenpeakywriter

@vintagecherryt

@indierockgirrl

@mrkdvidal1989

@bluesongbird

@dudde-44

@gasolinesavages

@kissforvoid

@bluebird592

@1eugenia1isabella1

@esposadomdp

@lulunalua23

@lovelace42

@bookklover23

@iwantmyredvelvetcupcake

@moonmaiden1996

@marlenamallowan

@cyphah (cannot tag)

@majesticcmey

@cleverzonkwombatsludge

@throughgoeshamilton

@alessioayla

@elenavampire21

@justforfiction

@cilliansangel

@alannielaraye

@satellitelh

@pandoramyst

@duckybird101

@snixx2088

@kylianswag

@alessioayla

@pono-pura-vida

@iraisbored69

@howling-wolf97

@aesthetic0cherryblossom

@weirdo-rules

@lovemissyhoneybee

@dazaiscum

@esposadomd

@etherealkistar

@ur--mommy

@throughgoeshamilton

@celverzonkwombatsludge

@cyphah

@atomicsouldcollecto

@heidimoreton

@nela-cutie

@futurecorps3

@delishen

@nosebleeds-247

@thirteenis-myluckynumber

@gills-lounge

@hjmalmed

@lost-fantasy

@tiredkitten

@sidechrisporn

@smallsoulunknown

@charqing-qing

@hopefulinlove

@aporiasposts

@shycrybaby

@me-and-your-husband

@hjmalmed

@lacontroller1991

@galxydefender

@aporiasposts

@multifans-things

@galxydefender

@hunnibearrr

@saint-ackerman

@raineeace

@lunyyx

@gentlemonsterjennie1

@littlewolfiieposts

@ihavealotoffandomssorry

@tn22220-blog

#cillian murphy#cillian murphy fanfic#cillian murphy fanfiction#cillian murphy smut#cillian murphy x reader#cillian murphy imagine#Oppenheimer#oppenheimer x reader#j robert oppenheimer#j robert oppenheimer x reader#oppenheimer x you#j robert oppenheimer x you#oppenheimer x y/n#robert oppenheimer#cillian murphy x you#cillian murphy x y/n

849 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Among colonized peoples there seems to exist a kind of illuminating and sacred communication as a result of which each liberated territory is for a certain time promoted to the rank of 'guide territory.' The independence of a new territory, the liberation of the new peoples are felt by the other oppressed countries as an invitation, an encouragement, and a promise. Every setback of colonial domination in America or in Asia strengthens the national will of the African peoples. It is in the national struggle against the oppressor that colonized peoples have discovered, concretely, the solidarity of the colonialist bloc and the necessary interdependence of the liberation movements."

Frantz Fanon, “The Algerian War and Man's Liberation,” for Algerian revolutionary newspaper El Moudjahid (1958), trans. Haakon Chevalier in Toward the African Revolution

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exoticism [...] allows no cultural confrontation. There is on the one hand a culture in which qualities of dynamism, of growth, of depth can be recognized. As against this, we find characteristics, curiosities, things, never a structure.

[...] Exploitation, tortures, raids, racism, collective liquidations, rational oppression take turns at different levels in order literally to make of the native an object in the hands of the occupying nation.

— Franz Fanon, "Racism and Culture" in Toward the African Revolution, trans. Haakon Chevalier

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Real connecting thread between Barbie and Oppenheimer isn't existential crises or the released date.

It's Connor Swindells and Jefferson Hall

Jefferson Hall, who plays Haakon Chevalier in Oppenheimer, was Mr. Robert Martin in ITV's 2009 adaptation of Jane Austen's Emma

Connor Swindells plays Aaron Dinkens in Barbie, and he also played Mr. Robert Martin in Autmn de Wilde's 2019 adaptation of Emma.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Regarding the bomb, Oppie wrote Chevalier, "The thing had to be done, Haakon. It had to be brought to an open public fruition at a time when all over the world men craved peace as never before, were committed as never before both to technology as a way of life, and thought, and to the idea that no man is an island."

But he was by no means comfortable with this defense. "Circumstances are heavy with misgiving and far far more difficult than they should be had we powered to remake the world to be as we think it."

"Oppenheimer had long since decided to resign his job as scientific director. By the end of August he knew that Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia University were offering him jobs, but his instinct was to return to California.

"'I have a sense of belonging there which I will probably not get over,' he wrote his friend James Conant, Harvard's president. His old friends at Caltech...were encouraging him to come full time to Pasadena. Incredibly, a formal offer from Caltech was delayed when its president Robert Millikan raised objections.

"'Oppenheimer,' he wrote Tolman, 'was not a good teacher. His original contributions to theoretical physics were probably behind him. And perhaps Caltech had enough Jews on its faculty.' But Tolman and others persuaded Millikan to change his mind, and an offer was extended to Oppenheimer on August 31st."

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Le dimissioni di uno psichiatra' (Frantz Fanon, Lettera al Ministro Residente, governatore generale d'Algeria, 1956) [Frantz Fanon, (1964), Letter to the Resident Minister (1956), in Toward the African Revolution. Political Essays, Translated from the French by Haakon Chevalier (1967), Grove Press, New York, NY, 1988, pp. 52-54 (pdf here)]; in Morire di classe. La condizione manicomiale, (1969), Edited by Franco Basaglia and Franca Basaglia Ongaro, Photographs by Carla Cerati and Gianni Berengo Gardin, «Serie politica» 10, Einaudi, Torino, 1976

#graphic design#psychiatry#anti psychiatry#book#frantz fanon#franco basaglia#franca basaglia ongaro#carla cerati#gianni berengo gardin#serie politica#einaudi#museo nacional centro de arte reina sofía#1950s#1960s#1970s#1980s

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The one thing you need to know about Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is that it moves incredibly fast and covers a lot of ground. For most of its three-hour runtime, the atomic bomb epic can feel as if you’re reading a dense biography about J. Robert Oppenheimer at three times the normal speed. With so many scientist characters orbiting Oppenheimer at light speed, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little lost at times.

To help watch “Oppenheimer” with a bit more clarity, it’s important to know the movie takes place during three time periods. One timeline is set in 1954 as the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) holds a security hearing to investigate whether or not Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) is a Soviet spy. The hearing prompts the film to flash back to the events of Oppenheimer’s life, from his university days to his role in creating the atomic bomb. These portions of the film, shot in color, make up the bulk of “Oppenheimer’s” three-hour runtime.

A third storyline is shot in black and white and takes place in 1959 as Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), the former chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, is seeking to become U.S. Secretary of Commerce under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Strauss finds himself at the center of his own U.S. Senate confirmation hearing, which threatens to expose his involvement in the events of the 1954 timeline.

“Oppenheimer” creates its own kind of fission by constantly jumping between these time periods, as characters and events twist depending on the perspective. Whether you want to go into “Oppenheimer” with a bit more knowledge or you’ve just seen it and are wondering who everybody was (it can be hard to keep track given the film’s relentless pace), below is your guide to the film’s cast and the real historical figures they play.

Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer

Cillian Murphy stars as theoretical physicist J Robert Oppenheimer, known as the “father of the atomic bomb.” Oppenheimer was named the director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. It’s here where Oppenheimer and his team developed the first atomic bomb for World War II. The bomb was detonated on July 16, 1945 in what is referred to as the Trinity test, with Oppenheimer present during the demonstration.

For Murphy, “Oppenheimer” marks his first time leading a Nolan movie in over 20 years. The two worked together on five previous features: Three Batman films, “Inception” and “Dunkirk.” Murphy revealed last year that in prepping to play Oppenheimer he skipped over all the mechanics of what makes an atom bomb and instead focused on the man himself.

“[I prepped by doing] an awful lot of reading,” Murphy recently told The Guardian. “I’m interested in the man and what [inventing the atomic bomb] does to the individual. The mechanics of it, that’s not really for me — I don’t have the intellectual capability to understand them, but these contradictory characters are fascinating.”

Emily Blunt as Katherine "Kitty" Oppenheimer

Emily Blunt stars as Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer, who married J Robert Oppenheimer in 1940. Born in Germany, Kitty was a botanist and biologist whose early life was associated with the Communist party after she became the common-law wife of party member Joseph Dallet Jr. She met Oppenheimer in 1939 at the California Institute of Technology, where he was a part time physics teacher and she was assisting physicist Charles Lauritsen. They began an affair while she was still married to medical doctor Richard Stewart Harrison. Kitty left Harrison and married Oppenheimer in November 1940 after she became pregnant with their first child, Peter. The couple moved to Los Alamos in March 1943 so that Oppenheimer could work full time on his Manhattan Project duties. They had their second child there. The isolation of living in Los Alamos contributed to Kitty’s alcoholism.

Matt Damon as Leslie Groves

Matt Damon plays Leslie Groves, who was the director of the Manhattan Project. The group’s mission was to develop the first atomic bomb during World War II. Groves had previously overseen the construction of the Pentagon while serving as an officer in the United States Army Corps of Engineers. As director of the Manhattan Project, Groves approved Los Alamos, New Mexico as one of several testing sites for the development of the atomic bomb. He personally recruited Oppenheimer to lead the charge at Los Alamos, a divisive choice at the time as Oppenheimer lacked a Nobel Prize and administrative leadership experience. Groves was on site for the detonation of the first atomic bomb on July 16, 1945.

Robert Downey Jr. as Lewis Strauss

Robert Downey Jr. plays Lewis Strauss, who served two terms on the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). Strauss was the organization’s chairman during his second term. He became an enemy of Oppenheimer’s due to the AEC’s controversial hearings in April 1954 that led to Oppenheimer’s security clearance being revoked. The hearings came as a result of Strauss becoming convinced that Oppenheimer was a Soviet spy. Strauss became convinced of the fact after Oppenheimer’s claim that the Soviets were four years behind the U.S. in nuclear weapons development got challenged. Strauss eventually asked FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to run surveillance on Oppenheimer, and the organization ran a wiretapping of Oppenheimer’s phones. Illegally-obtained conversations Oppenheimer had over the phone with lawyers and more were used by Strauss to stack the hearing’s odds against Oppenheimer.

Florence Pugh as Jean Tatlock

Florence Pugh stars as Jean Tatlock, who had a relationship with Oppenheimer before and during his marriage to Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer. The two met at the University of California, Berkeley, where Tatlock was a graduate student and Oppenheimer was a physics professor. Tatlock was a member of the American Communist Party. The film shows the two first meeting at a members gathering that Oppenheimer is brought to by his brother, Frank, who also had ties to the American Community Party. Tatlock’s relationship with Oppenheimer was cited during Lewis Strauss’ AEC hearing because of her Communist ties. Tatlock died by suicide at the age of 29 after struggling with clinical depression.

Josh Hartnett as Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Lawrence, played by Josh Hartnett, was a nuclear physicist from Canton, South Dakota who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron, a particle accelerator that was the first cyclical machine of its kind. When audiences first meet Lawrence in the film, he’s in the process of building that machine at the University of California, Berkeley. It’s here where Lawrence and Oppenheimer became close friends. Lawrence is credited with recommending to Leslie Groves that Oppenheimer be named the director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos research site. Lawrence went on to assist the Manhattan project with uranium-isotope separation.

Casey Affleck as Boris Pash

Boris Pash, played by “Manchester by the Sea” Oscar winner Casey Affleck, was a military intelligence officer in the United States Army. During World War II, Pash was tasked with investigating potential Soviet spy activity within the University of California, Berkley’s radiation laboratory. Oppenheimer was included among those interrogated by Pash, who determined that Oppenheimer was not a Soviet spy but may be connected with the Communist party given his previous relationships (see Jean Tatlock above). Pash suggested Oppenheimer be accompanied by counter-intelligence agents while on site in Los Alamos.

Rami Malek as David Hill

David L. Hill was an associate experimental physicist at the University of Chicago’s Met Lab during the Manhattan Project. Acording to the Atomic Heritage Foundation: “On December 2, 1942, he was one of the 49 scientists who witnessed the world’s first nuclear reactor to go critical.” Hill was also one of 70 scientists and workers to sign the Szilard Petition, a document written by Leo Szilard petitioning President Truman to avoid dropping the atomic bombs on Japan. In the film, Hill pops up in the 1959 timeline to disrupt Lewis Strauss’ bid for U.S. Secretary of Commerce by revealing the devious tactics Strauss used during the AEC hearing that stripped Oppenheimer of his security clearance.

Kenneth Branagh as Niels Bohr

Niels Bohr, played by Christopher Nolan regular Kenneth Branagh, was a physicist from Copenhagen, Denmark who won the Nobel Peace Prize in Physics in 1922 for his work on quantum theory and atomic structure. He is famous for developing the Bohr model of the atom. Whereas the U.S. had the Manhattan Project to develop nuclear weapons, Britain had the Tube Alloys. Bohr was a member of this group and made several visits to the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos site during the atomic bomb’s design process. He helped Oppenheimer with work on modulated neutron initiators. In the film, Bohr is one of Oppenheimer’s physicist heroes and he attends one of Bohr’s lectures in college.

Benny Safdie as Edward Teller

“Uncut Gems” and “Good Times” co-director Benny Safdie stars as Edward Teller, a theoretical physicist from Budapest who is known as the “father of the hydrogen bomb.” He was included in Oppenheimer’s 1942 summer planning seminar for the Manhattan Project at the University of California, Berkeley, and he moved to the Manahattan Project’s Los Alamos site in 1943 and joined the Theoretical Division, which was overseen by Hans Bethe (played by Gustaf Skarsgård in the movie). As part of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer tasked Teller with researching uranium hydride and the mathematics behind a nuclear weapon implosion. He was one of the few scientists on location to watch the detonation of the first atomic bomb during the Trinity test.

Gary Oldman as President Truman

Harry S. Truman, the 33rd president of the United States, is played in “Oppenheimer” by Oscar winner Gary Oldman, whom Nolan worked with on the “Dark Knight” trilogy. The Manhattan Project started in 1942 under Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency. Truman served as his vice president and was notoriously not told about the Manhattan Project until he became president himself. As president, Truman authorized the first and only use of nuclear weapons in war against Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. The bombs were dropped on August 6 and August 9, 1945. In the film, Truman assures Oppenheimer that the world will only see the president as a villain of history for dropping the bombs and not their maker himself.

David Krumholtz as Isidor Isaac Rabi

“Harold & Kumar” and “The Santa Clause” actor David Krumholtz stars as Isidor Isaac Rabi, an American physicist who won the 1944 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance. His work on radar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Radiation Laboratory led him to be a consultant on the Manhattan Project. Rabi was called to testify at the AEC security hearing in 1954 and strongly defended Oppenheimer. In the film, Rabi is heard passionately telling the AEC board that Oppenheimer loved and defended his country through his actions in the Manhattan Project.

Matthew Modine as Vannevar Bush

“Stranger Things” star Matthew Modine reunites with Christopher Nolan after “The Dark Knight Rises” to play Vannevar Bush in “Oppenheimer.” Bush was an American engineer who headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development during World War II. He helped sell the U.S. government on creating the Manhattan Project. Later during World War II, he joined the Interim Committee that advised president Harry S. Truman on nuclear weapons. Bush was present at the Trinity test and watched the detonation of the first atomic bomb.

David Dastmalchian as William L. Borden

Nolan regular David Dastmalchian plays William L. Borden, who served as the executive director of the United States Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy from 1949 to 1953. He is best known for writing a letter to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover that accused Oppenheimer of being a Soviet spy, which then led to the Atomic Energy Commission’s security hearing in 1954. The film positions Borden as a puppet of Lewis Strauss, as Strauss wanted to keep his hands dry in Oppenheimer’s public downfall. Borden went on to testify against Oppenheimer during the hearings.

Michael Angarano as Robert Serber

Michael Angarano stars as Robert Serber, an American physicist who contributed to the Manhattan Project. He previously had worked for Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley and the California Institute of Technology before he was recruited to join the Manhattan Project in 1941. Serber was also involved with a section of the Manhattan Project known as Project Alberta, which aided in the delivery of nuclear weapons during the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Jack Quaid as Richard Feynman

“The Boys” star Jack Quaid plays Richard Feynman, a theoretical physicist from New York City who shared the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics with Julian Schwinger and Shin’ichirō Tomonaga for work on quantum physics. Feynman joined the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos operation and was made group leader of Hans Bethe’s Theoretical Division, where he developed the Bethe–Feynman formula for calculating the yield of a fission bomb.

Josh Peck as Kenneth Bainbridge