#Paris Salon Auto Show

Photo

Ferrari 375 MM “Ingrid Bergman Coupé” Speciale

In 1953-1954 Ferrari built the 375MM (Mille Miglia) to conquer the racing World Sportscar Championship. While the majority were built for competition a few (about five) were made for the street and called Speciales.Film director Roberto Rosselini had one of the best known romances with Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman who eventually became his wife. He commissioned the 1954 Pininfarina Ferrari 375MM Coupé Speciale as a gift for Bergman, hence calling it the “Bergman Coupé”, even though she never received the car. It made its first public appearance at the Paris Salon Auto Show in 1954 before being delivered to Roberto Rossellini.Whether it was a publicity stunt or an actual gesture of love (or both) the car is an amazing sight much like the beautiful actress. Regardless of how the conversations went prior to starting construction any reason was a good reason to build it and a clever story to boot. The one-off car has covered headlights that “pop up” which were very modern for 1954 and side coves that were copied on the 1956 Corvette, it also has a rear hatchback. The gold paint is appropriately called Grigio Ingrid.Rosselini was on a roll and being an avid Ferrari owner he had a Ferrari 375MM Pininfarina spyder that had suffered an accident so he sent the car to coach builder Sergio Scaglietti to make a coupé for the street. The 1954 Mercedes 300SL gullwing was a styling influence and can be seen in the cab shape and back end of Scaglietti’s design.

#Ferrari 375 MM#Mille Miglia#Roberto Rosselini#Ingrid Bergman#pininfarina#Paris Salon Auto Show#one off

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

1966 Ferrari 365 P Berlinetta Speciale 4.4 litre V12

Although Ferrari was the first to win the F1 World Championship in the 60s with a mid-engined car, Enzo Ferrari was hesitant to offer road-going versions of these racers, particularly those powered by the big V12 engines. Sergio Pininfarina did see the potential of road going Ferrari with the trademark V12 mounted behind the driver. Although Ferrari was still not convinced, prominent Ferrari clients Luigi Chinetti and Gianni Agnelli were very interested and Pininfarina set about creating a spectacular new mid-engined Ferrari for the 1966 Paris Auto Show.

Ferrari provided the underpinnings for the new car, which were derived directly from the sports 330 P2 sports cars that raced at Le Mans. While these were powered by the latest twin-cam engines, they were usually re-fitted with a slightly larger, single-cam V12 when sold to customers like Chinetti. It was this 365 P specification that was also used for the new Pininfarina project.

The nose incorporated many familiar Ferrari/Pininfarina cues like the covered headlights and the egg-crate grill. At the rear, the 365 P featured the same buttresses that were found on the 1965 Dino show car. What really set the 365 P apart was its three-seater configuration with the driver placed in the middle, slightly forward of the passengers. This was made possible due to the lack of a transmission tunnel, which gave the car a flat floor. The central driving position also added a real single seater (Formula 1) feel to the car. To get in and out of the car more easily, the driver seat swivelled to the left, away from the gearshift lever. The unusual interior was clearly visible through the enormous glass roof fitted to the car. Finished in white, and dubbed the 'Tre Posti' for obvious reasons, the spectacular new show car made its debut at the 1966 Paris Auto Salon. It was subsequently shown at several more events around the world before being sold to its first owner in the United States through Luigi Chinetti.

#ferrari 365#berlinetta#ferrari#exotic car#dream car#sportscar#supercar#hypercar#luxury car#classic car#vintage car#muscle car#muscle cars#musclecar#musclecars#classic#vintage#aesthetic#aesthetics

534 notes

·

View notes

Text

1966 Ferrari 365 P Berlinetta Speciale 4.4 litre V12

Although Ferrari was the first to win the F1 World Championship in the 60s with a mid-engined car, Enzo Ferrari was hesitant to offer road-going versions of these racers, particularly those powered by the big V12 engines. Sergio Pininfarina did see the potential of road going Ferrari with the trademark V12 mounted behind the driver. Although Ferrari was still not convinced, prominent Ferrari clients Luigi Chinetti and Gianni Agnelli were very interested and Pininfarina set about creating a spectacular new mid-engined Ferrari for the 1966 Paris Auto Show.

Ferrari provided the underpinnings for the new car, which were derived directly from the sports 330 P2 sports cars that raced at Le Mans. While these were powered by the latest twin-cam engines, they were usually re-fitted with a slightly larger, single-cam V12 when sold to customers like Chinetti. It was this 365 P specification that was also used for the new Pininfarina project.

The nose incorporated many familiar Ferrari/Pininfarina cues like the covered headlights and the egg-crate grill. At the rear, the 365 P featured the same buttresses that were found on the 1965 Dino show car. What really set the 365 P apart was its three-seater configuration with the driver placed in the middle, slightly forward of the passengers. This was made possible due to the lack of a transmission tunnel, which gave the car a flat floor. The central driving position also added a real single seater (Formula 1) feel to the car. To get in and out of the car more easily, the driver seat swivelled to the left, away from the gearshift lever. The unusual interior was clearly visible through the enormous glass roof fitted to the car. Finished in white, and dubbed the 'Tre Posti' for obvious reasons, the spectacular new show car made its debut at the 1966 Paris Auto Salon. It was subsequently shown at several more events around the world before being sold to its first owner in the United States through Luigi Chinetti.

#Ferrari 365 P Berlinetta Speciale#Ferrari 365 P Berlinetta#Ferrari 365 P#Ferrari 365#Ferrari#car#cars#Luigi Chinetti#pininfarina

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

1956 Ferrari 410 Superamerica, By Ghia.

The 1955 Paris Auto Show was the venue at which Ferrari first introduced the Chassis to the Ferrari 410 Superamerica. By this time, the company had already outsourced the development of the body. The complete car was later unveiled the same year, just 4 Months after the Paris show. It was at the Brussels Motor Show that Ferrari showcased the first sample of a complete Ferrari 410 Superamerica. The task of designing the body had been outsourced to Pinin Farina, however, coach builders Carrozzeria Ghia also developed their own version of the body. At the end of the day, Ferrari had several bodies to consider but the one presented by Ghia gave them something to think about. All the bodies were adopted but the one presented by Ghia seemed too alien. The body was outfitted with garish fins and a submarine-like profile which made it very unique. Only a few cars were made with this body design. The uniqueness of the Ghia made it more coveted than most of the other 410 Ferrari models.

The chassis was a continuation of the Ferrari history. This particular sports car was not made for racing but rather for luxury drivers. To continue with the tradition of the Ferrari 375 America, the Superamerica also donned a 2800 mm wheelbase. The car also borrowed the Lampredi long-block engine from its predecessor. The V12 engine was modified, increasing its bore by some 4mm to 88 mm while the stroke remained at 68 mm. These adjustments helped increase the capacity by a whole 400cc, to make the Superamerica a 4963 cc at 6000rpm.

The 410 Superamerica body by Ghia was designed by Mario Savonuzzi, the same mind behind the Chrysler Glida and Dart. Although Gia made a sleek body that turned out to be loved by some, Ferrari never worked with this company again due to the alien look of the Ferrari 410 Superamerica.

Given that the body was not regarded as good looking, only a few units were produced. The massive fins towering approximately a foot above the rear fender were a deal breaker. However, like it is with most sports cars, the fewer the units the more the demand in later years. A few decades down the line, driving a 410 became a dream for many. Carrozzeria in Turin, on the other hand, developed two bodies. The company was headed by Mario Boano and Gian Paolo his son. The two had just parted ways with Ghia and established a new outfit. The bodies included a coupe and a convertible coupe.

As if Carrozzeria and Ghia designers were working together, they also produced a body that was loaded with fins. Although they were not as high as those produced by Ghia, the car did not look much appealing to Ferrari. The rear fins carved dramatically outward giving it a shape of a speed boat.

The body designed by Boano seemed to get some inspiration from the 1950’s Detroit. However, it was Pinin Farina that stole the show at the 1956 Paris Salon when he unveiled a unique design.

0 notes

Photo

1956 Paris Auto Show

NEW ! GentleCar is on Instagram !

#1956#paris auto show#paris#france#voiture#salon auto#motorshow#classic car#photography#collection#carporn#autoporn

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

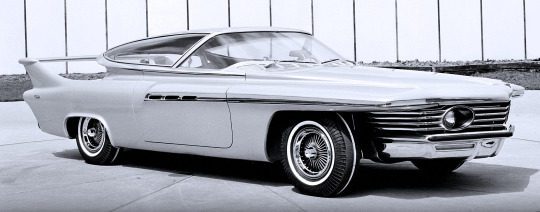

Chrysler TurboFlite Concept, 1961, by Ghia. 60 years ago this week the star of the Paris Salon de l'Automobile was Virgil Exner’s last show car for Chrysler. Powered by a gas turbine engine, the TurboFlite had it's American debut at the Chicago Auto Show in 1962

#Chrysler#Chrysler TurboFlite#concept#gas turbine#Virgil Exner#Salon de l'Automobile#1961#60th anniversary#60 years ago#Paris Motor Show#Ghia#retro futuristic

380 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Quatre autos, View from Strandvägen, Stockholm by Albert Marquet, 1938

Albert Marquet’s ”Quatre Autos” – View from Strandvägen, Stockholm

”From the east to the west, from the north to the south, Marquet portrayed the little changes of light above the hulls of the boats, the subtle play of the sky and of the sea. With incomparable self-assuredness he reduced the landscape to its essential elements”.

The French painter Albert Marquet discovered his passion for art and drawing at an early age. Contrary to his father’s wishes, Marquet moved together with his mother to Paris to further explore his artistic talent, where he enrolled at the Ècole Nationale des Arts Decoratifs and was introduced to fellow artist Henri Matisse who became a lifelong friend of his. While studying in Paris he often visited the many great museums and practised drawing by making copies of masters such as Claude Lorrain, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Outside the walls of the classroom and museums, Paris was a city bustling of life and Marquet enjoyed walking along the river portraying the city and its citizens. The young artist enjoyed painting the spectacular view from his studio in Paris, situated by the river Seine, and depicted the ever-changing appearance of his beloved city through various seasons.

Even though Paris was Marquet’s home and the city he always returned to, he found great inspiration during his many trips abroad. In 1938 Marquet visited Stockholm for two months together with his wife Marcelle. This historical city surrounded by water on every side and its stunning archipelago allowed the artist to paint his favourite subject over and over again: river, sea views, ports and ships. Immediately struck by the famous Nordic light, Marquet painted with an everlasting energy resulting in the execution of several paintings, depicting various parts of the city. The months spent in the Swedish capital offered the artist an opportunity to spend his days observing the boats which populated the sea, but also the everyday life of the people. His wife Marcelle was quoted in the catalogue for an exhibition with Albert Marquet in Lausanne in 1988: ”He found again a city made for him with water in all of its quarters and a variety of motifs. The painting included in this sale is titled “Quatre Autos” – View from Strandvägen, Stockholm and shows four cars parked next to each other by the quay. People are enjoying the fresh air while walking along the waterside; a little dog is jumping of joy to be running outside. The pink flowers in the tree resemble the colours of the cherry blossom, which can be seen in full bloom during early springtime in Stockholm. Marquet has captured the everyday life of the bustling city in the most thoughtful way and he depicted Nybroviken and Strandvägen many times before his return to Paris. Beautiful Strandvägen consists of architect-designed buildings mostly dating from the late 1800’s, situated with a spectacular view of the city.

Some of Albert Marquet’s Stockholm paintings were exhibited by Gösta Olson at Svensk-Franska Konstgalleriet in Stockholm from April to May in 1938. Legendary art dealer Gösta Olson became a close friend of Marquet’s and in his book “From Ling to Picasso”, he described their first meeting: “I ended up forming a firm friendship with Marquet since that summer of 1919. At that time he was still a bachelor, but a few years later he married Marcelle, a beautiful, moneyed French woman from Algeria. When she came into his life, his paintings suddenly became very expensive. I had the pleasure of introducing Marquet to Sweden. He was fascinated by the snow and came here to paint it.”

Albert Marquet was one of the first artists to use thick brushstrokes of unmixed colour deftly used in order to capture light effects and the contrasting shades to enhance the brightness. Together with fellow artists Maurice de Vlaminck, André Derain, Othon Friesz, Georges Rouault and Georges Braque among others he exhibited his colourful fauvist works in 1905 at the Salon d’Automne in Paris. Although Marquet painted with the fauvist painters for years, he used less bright colours and instead emphasised the less intense tones. By maintaining a strong interest in colours and form throughout his life he created vivid compositions filled with reflections of light and different shades of colour even in his later years. His friend and contemporary Marcel Sembat remarked: “No artist has the same relationship with light as Marquet. It is as if he owned it. He possesses the secret of a pure and intense light, which fills all the sky with its uniform and colorless glow. Above the mud, the stagnant waters, the glistening stones, the smoke of railroad stations, an immense sky stretches with no blue, no azure, but how luminous! Luminous as daylight itself and so transparent that a painting by Marquet gives the impression of a large window being opened onto the outside”.

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

1954 Ferrari 375 MM 'Ingrid Bergman Coupe' Speciale by Steve Corey

Via Flickr:

Wedding gift for Ingrid Bergman. Whether it was a publicity stunt or an actual gesture of love the car is an amazing sight. In 1953-1954 Ferrari built the 375MM (Mille Miglia) to conquer the racing World Sportscar Championship. While the majority (21) were built for competition, about five were made for the street and called Speciales. Film director Roberto Rosselini had one of the best known romances with Swedish actress Ingrid Bergman who eventually became his wife. He commissioned the 1954 Pininfarina Ferrari 375MM Coupé Speciale chassis #0456AM as a gift for Bergman, hence calling it the “Bergman Coupé”, even though she never received the car. It made its first public appearance at the Paris Salon Auto Show in 1954 before being delivered to Roberto Rossellini.

#pebble beach concours d'elegance#Ingrid Bergman#Roberto Rossellini#1945 Ferrari 375 MM#coupe'#Pininfarina#steve#corey#rare#cars#steve corey#photographer#automobile

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

"Love - the absolute circle of trustfulness - that's the secret of it all. I love the birds, the snakes, the society person, the academic, and the baby - all creatures of the universe are alike, and they will never harm you unless you fear them." -Charles Kellogg, 1915 Charles Dennison Kellogg was unlike any performer in the history of the American stage. He developed a few key obsessions - the forest, love, vibration, fire - into an irresistibly charismatic package and then sold that package in the form of himself through an uncanny use of the press, a vigorous appetite for travel, and a need to be the center of attention through a serpentine five-decade career as a pontificator and showman. In the early decades of the twentieth century, he amused and astounded heiresses and industrialists, yogis and artists, scientists and, most of all, the plain folk of most states in the union with demonstrations of his vision of a wholesome and interconnected world of all living things. His memory has largely faded, but he left behind a memoir, riddled with gaps and touched with hokum, many photographs, hundreds of press notices and reviews in newspapers, over an hour of sound recordings, at least one fragment of film, and a legacy of naturalism and invention that has entered into the lore of his native California. Kellogg was born October 2, 1868, the fourth of five children to Henry Kellogg (b. 1822 in New London, Connecticut) and Mary E. Carlisle (b. 1845 in Jefferson, New York) in the Sierra Nevada mountains of northern California’s Plumas County in a settlement called Spanish Ranch “nearly a hundred miles from the nearest railroad,” according to Kellogg. His father’s involvement in a nearby goldmine in the 1850s paid off, and he used his share of the profits to establish a provisions store for the area prospectors. Kellogg wrote that his mother was the only white woman in the area, and that he “lost her in infancy.” In fact, she left the family when he was about 3 years old, and his autobiography gives us an indication of the wound her abandonment left through the pains with which he purposefully wrote her out of his life’s story. (She died in Long Beach, California in 1917.) In his auto-mythology, Kellogg was as a child close to a Chinese servant named Moon and an unnamed Indian woman, who, he wrote, “taught me to fear no creature [and] taught me, too, the habit of minding my own business, letting the other fellow alone - bird, bear, snake, Indian and other humans. […] My earliest recollection is sitting with the Indians about their campfires or watching the Chinamen boil their rice between stones.” The impressions of the sounds and feelings of the wilderness in early childhood embedded themselves deeply in young Charles. He recalled it as a period of immense freedom, a world with “no doctors, missionaries, telephone, telegraph, schools, saloons, poorhouse, jail or gamblers; no police for there was no disorder. There were birds, grizzly bears, deer, wolves, foxes, skunks, badgers, mountain lions, wild cats, snakes, and all the smaller wood folk.” It was also here that before the age of six, he witnessed a wedding for the first time and learned about death and funeral rites among the Chinese. In this powerful paradise of vivid experiences, he was “lonely, but not unhappy,” spending his days “always preoccupied with birds and insects, listening to them and talking to them in their own languages.” It was between the ages of four and six that he began to experiment with his ability to imitate birds, forcing air through this nose with his mouth closed. He claimed throughout his adult life that this remarkable ability came down to an anatomical formation in his larynx similar to that of a songbird. This claim, repeated thousands of times, often backed up with the validation of unnamed doctors, was, of course, utter nonsense, but it is not clear whether he believed it, on some level, himself. It was many years after Kellogg had been sent off to live with his mother’s relatives in Syracuse, New York at the age of six or seven that Charles realized that he was in possession of a remarkable skill. In Syracuse, he learned to work with tools, to build furniture and fireplaces - skills he valued and worked into his persona as a woodsman. He attended Syracuse University and sang in the choir, aware that a relative of his father’s (by marriage) Clara Louise Kellogg, had become a famous soprano. But apart from mentions of his education in the manly, manual crafts, the period from the ages of seven to twenty-two when Kellogg became a civilized, college-educated Yankee were never mentioned in Kellogg’s stories. They didn’t serve what he was selling about himself. Almost immediately after graduation, we have the first press notice of Charles Kellogg as a performer, August 1891 at Chautauqua, New York, a hotbed of aspirational “edutainment,” where he debuted his unique bird-imitation talent. Realizing that he was on to something, he gave at least a half-dozen concerts of music with bird imitation at YMCAs, churches, and meetings around Pennsylvania and New York at the beginning and end of the year and another half-dozen in California a few months later. There were more shows in California in 1893-94, then back to Pennsylvania and Massachusetts in 1896-97. All of February and March of 1898 was spent touring Pennsylvania and Ohio. January through April of 1900 was spent on the road through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Maryland, D.C., and Virginia, by which time he was claiming to have anywhere from a 9 1/2 to 12 1/2 octave vocal range. After getting married for the first time, he spent November 1900 to April 1901 touring the same states again plus Connecticut and published an article in Success magazine called “The Wickedness and Folly of Killing Birds.” In early 1902, through Horace Traubel, friend and executor of Walt Whitman, Kellogg met the naturalist John Burroughs, thirty years’ Kellogg’s senior, with whom he traveled to Jamaica during January and February. Kellogg held Burroughs (as wells as naturalist John Muir, with whom he also spent several days with at one point) in esteem and treasured the memory of their trip. Burroughs was certainly an influence on and model for Kellogg. Whether Kellogg was aware of Burrough’s fierce denunciation in a 1903 article for the Atlantic denouncing contemporary nature-writers tendencies to anthropomorphize the natural world is unclear, but it was major news among naturalists for years, ultimately drawing comment from President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1904, Kellogg and his brother bought a 45 acre plot in North Newry, Maine, where they built the Kellogg Nature Camp, a Summer vacation resort for city folk wanting to spend time in with the woods. They built cabins connected by boardwalks, a common-house with a large fireplace (a specialty of Charles’s) and powered it with a waterwheel. It is now part of a nature reserve with many of the structures they built still standing. And each year during each late Fall, Winter, and early Spring, in an ever expanding radius, Kellogg began to cover the country with shows of his knowledge of and ability to replicate bird song - Tennessee and Kentucky by 1903, Nebraska and Kansas by 1907. By that time, shows regularly lasted two hours and received glowing reviews everywhere he went. His break came at the age of 43 in 1910, by which time he had left his first wife Emily and relocated to San Francisco and had ingratiated himself within a world wealthy socialites, where he was a favorite at parties. On December 4 The Call newspaper ran a, glowing illustrated full-page article on him titled The Man Who Sings With Birds in Their Own Language, which crystalized in print the stage-show that Kellogg had been assiduously developing, year after year, for nearly two decades. "He has the uttermost faith in the power of love and kindness,” the article asserted. “’It is all love," he says. 'Anybody who goes into the woods with the spirit of love in his heart without the faintest desire for destruction or possession can make friends with the birds if he is merely tactful and patient. Birds can read the heart better than men. They know their friends and are ready to love them.' In Kellogg's mind, there is no place for fear or hatred [...] Fear creates fear. Hatred breeds hatred. Love engenders love. These are the cardinal tenants of Kellogg's creed." His count of 3,000 performances in 24 years was, like almost everything else he said, likely an exaggeration but not so far from the truth that you could discount the claim out of hand. Twenty years of stories, stage patter, and tricks caught the public imagination. Less than a month after the article appeared in San Francisco, Kellogg went to Camden, New Jersey to cut his first trial disc for Victor Records on January 24, 1911 and then another four performances on the 28th. Victor didn’t release any of them. When Kellogg went back on the road on the east coast from October to December 1911, he had a new repertoire of claims for his abilities. This is when his press notices begin to claim that his throat is abnormally formed like that of a bird’s. And that: -He’d been to Paris and Berlin and received high praise. (His sister-in-law did invite him to perform at a private salon in Paris, where he met August Rodin, but not until 1912.) -His throat had been examined at Harvard. (He had been claiming that he’d “baffled scientists” there for years, and that they’d measured his vocal range from 64 cycles a second to 49,560 cycles.) -He speaks 15 animal languages and can communicate with bears, rattlesnakes, worms (who, he said, can sing), lizards, squirrels, etc. -That a man could (theoretically) be pinned motionless to a tree with the use of sound. -And, most crucially for his career from this point forward, that he could extinguish fire with sound. In February 1912 an article making many of these claims along with his belief that “vibration will ultimately take the place of electricity as a motive force” ran in syndication across the country in advance of his having signed with the Orpheum chain of vaudeville theaters for whom he performed three shows a day (a matinee and two at night) for months across the west coast - Winnipeg, Spokane, Los Angeles, etc - from April 1912 until April of the following year and then, without his standard Summer break, for the rest of 1913 across the east coast plus Indiana, Illinois, North Carolina, and Kansas. In New York City, he gave a demonstration of divination for water for another syndicated news article. He spent 1914 touring the west coast and midwest before returning to the Philadelphia area where he remarried to Sarah “Sad’i” Fuller Burchard on January 14, 1915 in Wilmington, Delaware. One month later, he went again to Camden, New Jersey in February 1915, where over two days he recorded the first four performances that were issued on discs. He was almost 47 years old and had spent the past 25 years on the road developing his act in halls, theaters, auditoriums, clubhouses, churches, tents, homes, and high schools. Kellogg’s assessment of vaudeville does not have the ring of disreputable behavior that has often been handed down through the years: “Back stage is not such a fry cry from the forest, for on these vaudeville stages I find conditions that are congenial to my own habits of the woods - conditions I do not find elsewhere in the world. In hotels, railroads, and even private homes, tobacco and other noxious odors, and not infrequently even uncleanliness such as cuspidors, are not unusual. System, punctuality and order are seldom the rule. In the forest, in all nature, punctuality, order, and system are the very breath of life. The stars, the tides, the migration of birds, the appearance of herbs, the trees, the flowers are all on time, giving that sense of harmony felt, and rejoiced in by all. Back stage, I find pure air in perfect ventilation, no tobacco, no bad odors, scrupulous cleanliness, system, order, punctuality - in a word, the perfection of organization, bringing quiet and a reposeful atmosphere in which to work.” Kellogg’s first vaudeville tour was a 1912-13 run at the west coast Orpheum chain, run by Percy Williams who was known as the first vaudeville impresario to pay high fees to the acts he wanted. The west coast Orpheum houses were run locally and, according to Joe Lurie Jr’s Vaudeville: From the Honky-Tonks to the Palace (1953), unlike many of the rowdier and down-market vaudeville theaters, “they were all fine, clean, well-appointed theaters, running clean shows, and were a credit to their towns.” Kellogg performed at shows with as many as eight other acts on the bill. The shows in Washington opened just after Bert Williams’ run and included a spoof of the domestic morality play Everywoman titled Everywife, the blackface comedy duo McIntyre and Heath, the Fearless Ce Dora (“one continuous thrill through the seven minutes which she spends revolving at railroad speed inside [a] golden globe”), and Thomas Edison’s early, abortive attempts at talking pictures. Through 1915 and 1916 Kellogg was headlining in the eastern U.S. for both Orpheum and B.F. Keith’s circuits of vaudeville houses in the eastern U.S. and Quebec as well as Majestic Theaters in the midwest and Texas, where others on the bills included dog acts, monkey acts, the Dennis Brothers’ rotating ladder act, and various acrobats, singers, and comedians. At the end of each show was Kellogg, standing in front of a painted woodland backdrop. Second on the bill for at least one of those shows was the Three Keatons, including 20 year old Buster, who was on the verge of leaving for Hollywood. Kellogg himself appeared second on the bill in late 1916 only under Nora Bayes, arguably the most popular singer in the U.S. His proclamations to the press at the time ranged from the flatly false (that he did not believe “that wild animals die unless molested by man or that they struggle with each other, because I have never seen them do either,” that he did not know his own age, that hat he spent 9 months of the year in the wilderness and came “into civilized society only when the call of a friend proves too strong to resist”) to the simply peculiar and the nearly-true (that he had “never read a book through - print disturbs me - although I believe in the teaching of the Bible as I have heard of them from others, because I have seen the proved true in my own life,” and “I have never tasted fish, flesh, or fowl, although I am not a vegetarian,” that dogs will die from long durations of discordant sounds) to the charming, bordering on visionary (“Fear - that’s what causes all sin. Fear of money, fear of getting caught, fear of wounded vanity, fear of public opinion, all all the rest,” and “I can take the recorded songs of a thousand birds and they will be harmonious. That’s because they are in tune with nature, while man and his instruments need to be attuned.”) Kellogg was an avid photographer, claiming never to take a gun (or a compass, claiming an inborn sense of direction) into the woods, but producing photographs prolifically from 1902 onward. We know that he had performed in Rochester, New York, home of the Eastman-Kodak company, by December, 1900, around the time of the introduction of the “brownie” camera - the first cheap, popular device for making photos. It is unclear whether he might at that point met Gertrude Achilles Strong (b. May 4, 1860; d. May, 1955), a recent divorcee and the daughter of Henry A. Strong, co-founder and first president of the Kodak company, or whether they met much later in the late 1910s in Hawai’i. Regardless, their meeting and relationship was pivotal for Kellogg. His first disc for Victor certainly sold very well, likely in the tens of thousands, and he claimed that he could earn $4,000 a week (a staggering $100,000 in today’s money - and more than half of the $7,000 a week that the Orpheum paid Sarah Bernhardt, their highest-paid entertainer) performing in the 1910s, and his family was relatively wealthy. But they weren’t Gertrude Achilles Strong wealthy. Almost no one was. When she died in 1955, she left behind a fortune of over nine million dollars, making her the single richest person in the history of the state of California at the time, well into the top half of the richest 1% nationally. In 1913, Kellogg bought over 88 acres in Morgan Hill, south of San Francisco, an area he dubbed “Ever Ever Land,” where he built an inventive and “environmentally responsive” open plan cabin that he called “The Mushroom.” Around 1920, Gertrude Achilles Strong bought his land and more than 500 additional surrounding acres. She built a mansion for herself there at a cost of $276,000 (four million today) as well as a house for Kellogg and his wife and put him on her permanent payroll as property manager. He built water systems for her property and built and patented a riding fruit and nut picker for the property, while he lived comfortably with his wife Sad’i and two young live-in maids for the rest of his life. Each winter from 1915 through 1919, Kellogg toured from coast to coast, stopping in Camden, New Jersey to record a few performances for Victor Records, where he cut a total of 26 performances, six of which the company the company destroyed without having issued them. On February 15 and 16, 1916, he recorded four light classical pieces, imitating birds and following along the well-known melodies, as if a bird were singing the tunes in its down language. On the 15th, Alma Gluck, a star of the Metropolitan Opera and one of the most popular sopranos in the U.S. also recorded three of her best-selling performances. Although she did not record on the 16th, and Kellogg possibly traveled more than 100 miles north to Dalton, Pennsylvania near Scranton to visit friends on the 17th when Gluck recorded “The Bird of the Wilderness,” with words by Rabindranath Tagore, he joined her again in Victor’s studio on the 18th for two bird-themed performances on which Kellogg provided bird imitations. When the single-sided 12” disc of “Listen to the Mockingbird” was released in the Spring along with a significant marketing push by Victor, its sales exceeded expectations. When “Nightingale Song” from a mid-19th century operetta called Der Vogelhandler (The Bird Seller) by the Austrian composer Carl Zeller, was released a month or two later as a less-expensive 10,” it became one of the best-selling records of the decade. Apart from the two sides recorded with Gluck, Kellogg’s recordings are evenly divided between the bird-imitation novelties with musical accompaniment (an unenduring genre that grew in popularity both on stage and on records in the early decades of the 20th century) and segments of his stage act in which he would lecture on his relationship with the wilderness with demonstrations of bird-calls interspersed. Seven of those sides remain a fascinating glimpse of Kellogg’s performing persona. The last of them, titled “Bird Chorus,” recorded without commentary on January 14, 1919 is an extraordinary and unheralded moment in the history of sound recording. Starting in January 1915 and through all of 1916, Kellogg added a section of his stage act in which he turned on “an orchestra” of six Victrolas borrowed from local dealers in each town, and played discs of his bird-imitation and then proceeded to perform with them, simulating, as one reviewer put it, “a voice from the deep forest.” For the “Bird Chorus” disc Kellogg simplified the process to a single disc of his own performing along with a live performance, ingeniously weaving two continuous sequences of songs together to give the impression of multitudes of birds singing together. It is the first instance of overdubbing. Notably lacking from Kellogg’s discography are examples of his most spectacular and longest-lasting piece from his stage act - the “Blade of Flame.” By the beginning of 1912, Kellogg introduced a gas burner on stage which produced a four-foot blue flame inside a glass tube. Kellogg told his audience that because all of nature is connected through vibration and because of the gift he possessed of a vocal range many times that of highly trained singers and larger than that of a grand piano, he could cause the “blade of flame” to dance and ultimately to extinguish it using only his voice. It was, next to his bird-imitating, his best-known and best-loved routine. He augmented it with a demonstration of the technique of building fire by wood friction (a skill he imparted to the then-nascent Boy Scouts). Naturally, his fire performances in enclosed theaters were of some concern to local fire departments, and he made it a regular public relations stop to visit fire houses in each town during the afternoons to demonstrate the act, reassuring them of his control of fire and wowing them along with the local press. The only footage apparently extant of Kellogg is one silent minute of a newsreel outtake Kellogg giving this demonstration for a group of Boston firemen on November 5, 1926. (The film, including ten precious seconds at the end of Kellogg demonstrating his bird-imitation technique facing the camera is available online at the University of South Carolina’s Moving Image Research Collections site.) He continued to elaborate the routine, using bowed tuning forks. In the mid-20s he arranged a series of radio broadcasts intended to demonstrate his hypothesis that vibrations broadcast at sufficient amplitude could extinguish house fires. His proposal was that in the future each house could be scientifically tuned such that fire departments would need only to broadcast the appropriate frequencies to put out the fires. The seed for the idea seems to have originated with Kellogg’s exposure to Herman Helmholtz’s book On the Sensation of Tone which had already been published in two editions in America before Kellogg began making theatrical use of its central concept, that the air around us is a medium through which vibration is transmitted in waves. Kellogg was so enamored with the idea that in May and June of 1913, Kellogg added a bit to his stage act in which he explained to the audience that mental vibrations are crucial in love and marriage and that “tuning” of a silent “mental wireless” to a compatible frequency with one’s mate was central to harmonious love. Newsprint reviews of his attempts to demonstrate this with his wife were decidedly snarky. The audience didn’t get it, and it was quickly dropped from the act. Kellogg’s greatest and most enduring “hit” as a showman was neither a stage-act nor a recording. It was a vehicle made from two large pieces. The first was a Nash Quad, a four-wheel drive truck capable of hauling four tons. The second was a 22-foot section of a fallen redwood log eleven feet in diameter. He obtained the former in early Summer 1917 from the Nash Motor Company in Kenosha, Wisconsin while they were being produced for use in the First World War. Kellogg convinced the company’s namesake president of a vision of the beauty of California’s enormous redwood forests (and, very likely, the publicity benefits of Kellogg’s scheme) and took the Quad to Bull Creek Flat in Humbolt County, where with the help of several axemen from the Pacific Lumber Company they spent months sawing off a section of a fallen tree, stripping its bark, and carving out its interior into a living quarters with beds, cabinets, kitchenette, and bathroom. Mounting it on the chassis of the Quad, he polished and varnished the whole thing a copper color and installed electric lights. By November of that year, he drove the wooden cabin-on-wheels that he dubbed the Travel-Log cross-country, stopping in Kenosha for work on the radiator and “finishing touches” (including their brand name, it seems). Using his celebrity and press-savvy, he toured the machine, giving talks on the beauty of the great redwoods and the dire need for their preservation, taking a piece of the forest to the people. In the process, he introduced America to the idea of a mobile home. It now resides in the Humbolt State Park’s visitor center, reportedly only yards from where the tree from which it was hewn grew for centuries. Kellogg recorded 11 more performances for Victor during the period 1924-26. Seven of them were discarded by the company without having been released. The remaining four were re-recordings of his first two records using the new invention of microphones. While he continued to perform, his schedule gradually slowed as he shifted his first to attention to Gertrude Achilles Strong’s property and then to a fascination with Fiji, where he first traveled in the Spring of 1925 from Hawai’i. Fixated on the idea of wooden lali slit-drums and their use in communication over distances, Kellogg arrived alone and presented himself as a naturalist to the Chief of the Native Department on the island of Suva, who showed him a the instrument and for him to visit to the island of Baqa to witness fire-walking (after Kellogg had given a demonstration of the “blade of flame” routine, having thoughtfully packed the gear needed for it, and gave a performance of “Narcissus” as a bird-imitator) in the company of a British medical doctor. Kellogg was suitably impressed and incorporated discussion of both lali drumming and fire-walking as further evidence of his central theme of the need for vibratory attunement in his subsequent performances through the 1920s and 30s. In 1929, Kellogg survived a near-fatal car crash immediately before he self-published The Nature Singer: His Book, a profusely photo-illustrated collection of impressions drawn from his life and career and a document of his own self-invention, which went through at least two printings (all of them signed; the first 1000 are numbered), wrapped in the attractive but exceedingly brittle birch parchment that he used as stationary and for press notices. That year, he also patented an automobile ignition that started with whistling. He continued to criss-cross the country, giving talks based on his experiences in nature combined with pleas for conservation. There was talk of a movie that never manifested. In 1940, he and Sad’i adopted a 9 year old girl named Shannon who had been born in Honolulu. (She subsequently married a Charles Newton, nine years her senior, in 1961, divorcing him in 1967, and died in 2007.) When in 1946 Paramahansa Yogananda published his Autobiography of a Yogi, describing his encounters with spiritual teachers and his travel in India and U.S., he briefly recounted in a footnote having seen Charles Kellogg do the “blade of flame” bit in Boston in the ‘20s. And that’s who Kellogg has been for the past century - a remarkable and unlikely figure at the intersection of science and art and showmanship and the spiritual. Charles Kellogg’s health declined through the 1940s before died of a heart attack on September 3, 1949 at the age of 80.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1929 Duesenberg J-184 Murphy Convertible Coupe

GILMORE CAR MUSEUM

Hickory Corners, Michigan

DUESENBERG: Celebrating an American Classic

The Gilmore Museum has put together a special exhibit featuring eighteen Classic American automobiles; Duesenberg.

Commemorating the 90th anniversary of one the Gilmore’s most famous cars, the 1929 Duesenberg J-111 is joined by other fabulous examples from around the country for an impressive display of power and beauty.

This display of these unique automobiles is featured in the Heritage Center Main Gallery.

1929 Duesenberg J-184 Murphy Convertible Coupe

Body by Murphy Co. – Pasadena, CA

A DUESENBERG TIME CAPSULE

Though it may be on its fifth owner, this 1929 Duesenberg Convertible still maintains its original chassis, engine, transmission, body and interior. It has been verified by the ACD Club. The car began its life representing its manufacturer at the Paris and London Auto Salons in 1929 and spent the following two years in the private collection of notable art collector Sir Geoffrey Duveen of London. Other notable owners include Walter Pratt, a wealthy politician and paper mill owner from New York and Roy Park who helped originate Parks Communication and the Duncan Hines Packaged Foods Company.

In recent years, this Duesenberg has returned to its origins as a show car. It has won awards at many different shows, including The Fédération International des Véhicules Anciens for “Most original Car” at Ault Park Concours d’Elegance in Cincinnati.

Information provided by the Gilmore Car Museum.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Screenshot bingo continues.

If anything, TI – and that is mainly Richard Armitage as Claude Monet – is a pleasure to look at. Just a cursory glance at my screenshot loot of episode 2 shows that there were smiles and gorgeous galore. But well, it’s not all beauty and joy in the show, and there were things that I felt irked by, too.

Quick summary

Part 2 of the mini series begins after the Franco-Prussian war with Monet and his family returning from London. He reconnects with the scene in Paris and continues to paint – without much success as the salon is still dominated by the Marquis de Chennevières who ridicules the Impressionists’ work. After focusing on Monet and his friendship with Renoir and Bazille, as well as Manet’s groundbreaking work on painting in part 1, this episode still has Monet as the main protagonist but also looks at Edgar Degas. With his eyesight deteriorating and money running scarce after his father’s death, Degas struggles as a painter. Despite producing beautiful work, his treatment of his fragile models is rude and neglectful.

The early worm paints the sunrise. Screenshot

Monet finds himself transfixed by light and colour. The painting that eventually is responsible for the moniker “impressionism”, is a study of the sunrise that he paints in a rush one morning, racing outside to capture the sunlight in all its glory. Similarly, he sets his canvas up in a train station because he wants to paint the whirling steam. What a pioneer! As the salon won’t display the impressionists’ paintings, the group decides to put on their own show, which is to take place in a photographer’s studio. “One passing fad helping another” as the Marquis says… little does he know…

. Renoir, Monet and Degas are on board; Manet declines any participation. Despite great hopes, the exhibition is not a success, neither with critics nor with public.

Consoling Alice Hochedé… well, who wouldn’t want to be consoled by him… Screenshot

At this point, Monet and his wife are living in poverty. Money from Monet’s patron Ernest Hochedé is not forthcoming either. When Monet goes to visit his patron’s home, he meets Hochedé’s wife Alice and the series makes it clear that she will have much influence on Monet later. Meanwhile, Camille’s health deteriorates. She has always been a favourite model for Monet, and even in death he remains transfixed by the play of light on her features. The fortunes of Monet’s patron Hochedé have changes, too, and Alice and her children have moved in with Monet – which leads Degas, jealous of Monet and Renoir finally being represented in the salon with their paintings, puts a hoax article in the newspaper declaring Monet dead, and claiming he has a relationship with Alice Hochedé. Monet confronts Degas – and the impressionist movement seems to splinter…

Some thoughts on part 2

We get another episode opening with Monet on a train. Maybe it has worked out cheaper that way, but whenever I see steam trains and the name Richard Armitage on the credits, I immediately think of NS. And I always wonder whether these things are coincidences or whether some clever scriptwriter has copped on that repeating the earlier crowd pleaser is something that would appeal to the fans? Well, probably not – we are far too small a group to be recognised. But it is funny, nonetheless. And it begs the question what RA thinks about these things? Does he have the same associations? Does he ever suspect he is being used as a babe magnet?

Granted, the more I watch of TI, the more I get used to the straggly hair and the goaty beard. And suddenly Richard looks gorgeous… Especially his blue eyes stood out to me in this episode, where I particularly noticed the intense shade of blue in a number of scenes.

#gallery-0-7 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-7 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-7 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-7 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

I have to admit that I am not that interested in the other painters, and that is all down to RA. I want to see Monet’s story, not Degas or Manet. Renoir is acceptable – because he is close friends with Monet and therefore likely to feature in scenes… Mind you, I thought Degas’ story is really interesting because of the connection to the ballet. How the young dancers were taken advantage of by rich men who pretend to be patrons but really only just want to get into the dancers’ knickers… Dirty business…

In contrast, Monet is clean and beautiful art. “The sun was my muse”, he explains, and that whole sequence (around 15:00) of Monet getting up early to paint at sunrise basically is the whole mini-series in one scene. He explains what is so compelling about the impressionists: For the first time, an art movement focuses on light and how it is seen depending on time of day, angle, etc. , hence Monet’s excitement and rush to paint the sunrise. Paintings are not static as such, but they now depict movement – such as the rising sun, or the whirling steam in a train station. And like its distant cousin photography, impressionism for the first time elevates ordinary people, scenes and objects to subject matters, often painting from unusual angles and communicating not just superficial beauty to the spectator, but transporting an atmosphere or emotion. This is a mini lecture on what impressionism is and how it differs from what came before.

Monet worshipping the sun… reminds me of Ricky Deeming calling upon the goddess… Screenshot

That is all very interesting but what is compelling in the series remains the smile, the joy, the happiness, the energy of Monet. Always positive, always hopeful, always a doer. He doesn’t fret when he is poor and unrecognised; when he makes the sale – he spends the money on bread and cheese. And he organises a counter-exhibition to the salon when the art dealer stops buying the impressionists’ art.

As has been remarked on several times in the comments to last week’s re-watch post, the show is very good at putting the famous Monet paintings into context – or visualising them on the screen. And again, this is a wonderful lesson for all art-interested people, seeing what Monet must have seen when he was dabbing the canvas and created his masterpieces.

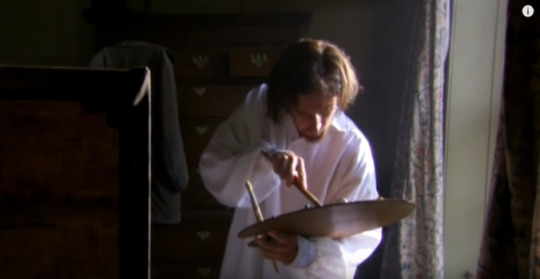

Talking of dabbing the canvas – another point of discussion last week was a quote by TI‘s art consultant Leo Stevenson who paid Richard the greatest compliment. Thank you to Lilianschild for digging up the quote.

Some actors, like Richard Armitage, actually took to painting extremely well and painted in a really convincing manner. Others were nervous of doing any real painting and so I sometimes stood in for them in their costumes for the close-ups of ‘their’ hands painting or drawing. .”

I had a little look, and while of course it is inconclusive how much he actually painted himself, there is something about the way RA holds the paint brush. Even though he has really large hands and therefore the brush looks very delicate, it appears as if he has the lightest touch. He holds the paint brush properly and dabs lightly at the canvas. Method man is certainly convincing… Clearly some prime porn for fans with a hand fetish, as the extremities are beautifully accentuated by frilly shirt cuffs and wide puffy sleeves.

Delicate fingers…

What still irks me, is the framing action with old Monet in Giverny. And here is another reason why I don’t like those interludes: I can’t quite reconcile the happy, cheerful, positive young Monet with the old, negative codger from 1920. Old Monet seems to be scolding the journalist for every single question, always correcting him, always defending himself, always the one who knows, always raising his voice, always arguing. Never calm, quiet, benign and wise with age. He’s really not very sympathetic at all. The Four Yorkshiremen by Monty Python come to mind…

While I very much enjoyed all the shiny happy Monet of episode 2, I was also glad to see him expand his scope to some more dramatic emotions. The death of Camille is a truly touching scene – the contrast of the painter, concentrating on shapes, light and composition, seeing beauty in death, presumably, and thus immortalising his dead wife once again on canvas – and then, immediately afterwards the bereaved husband who has just realised the enormity of his loss and helplessly cries. “Jesus, he’s devastating when he cries.” is what I noted down. It reminded me why and how I fell for Armitage the actor, i.e. when he played Lucas North in the final scene of season 9 on the roof and… He needs more roles like that!

Emoting something else than anger

Luckily for us, the episode did not end on a sad note. Instead we see the beginnings of the relationship with Alice Hoschedé, and that is quite beautiful, though. Possibly because it starts out without love, but a bit of a confrontation. The scene in the garden where Monet consoles Alice because she tells him her husband can’t pay him… the soft touch of his hand on her hair. She cries on his shoulder. Yes, that demands three screenshots for illustration #UncompromisingFangirlMode

#gallery-0-8 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-8 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-8 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-8 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Sure, there is the fangirl fluff again. Coupled with puppy eyes and *boom* there go my pants. But when it comes to the man who doesn’t just have a pigeon hole but a whole dovecote for poker-faced, emotionally hardened spy types, this would really be quite a departure.

So, all in all an hour happily spent watching young Monet. At the end of the episode, the tides are finally turning. Monet gets a painting into the salon. He cuts his hair. And he gets quite angry. I leave you with a derp that isn’t meant to make fun of RA – but just to make you laugh. How unrecognisable he is in that screenshot. Thank cod!

The Impressionists part 3 to follow next week? Hopefully I will get it in – I will be travelling home to Germany on Tuesday, staying one week with my mum.

Feel free to comment below – or to write your own review on your own blog. If you do, don’t forget to link to it in my comments!

Re-Watching The Impressionists [part 2]- Impressed Screenshot bingo continues. If anything, TI - and that is mainly Richard Armitage as Claude Monet - is a pleasure to look at.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

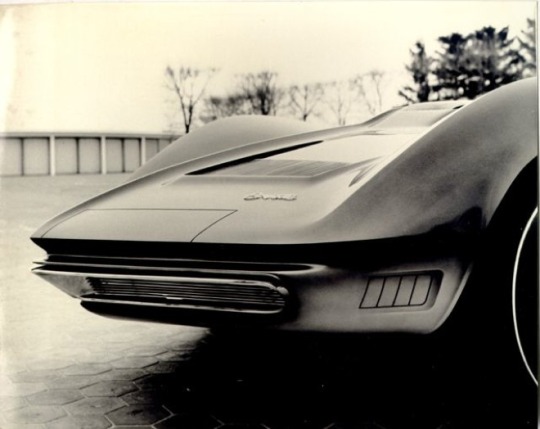

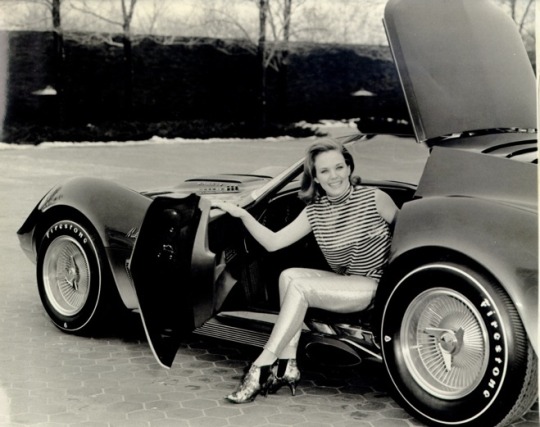

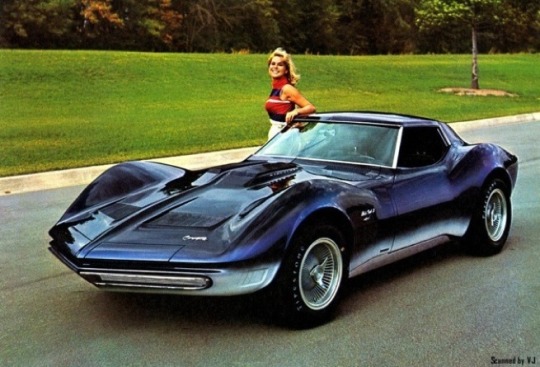

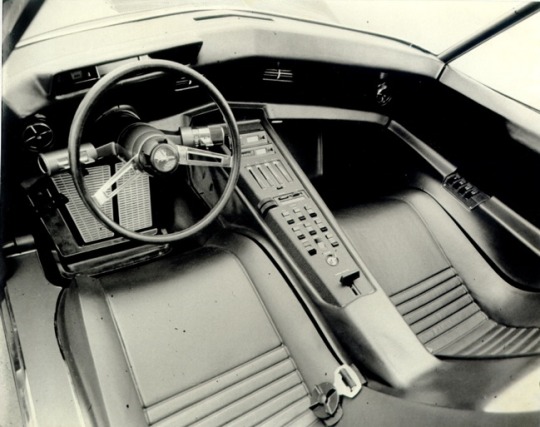

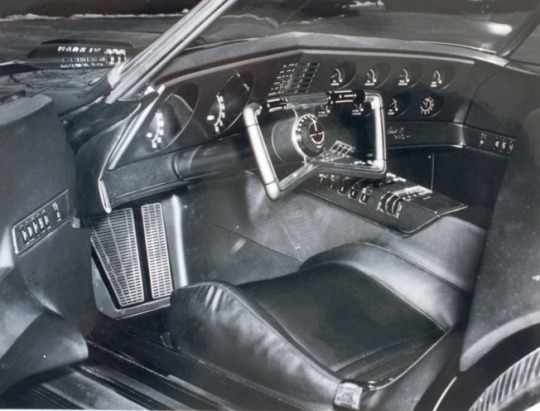

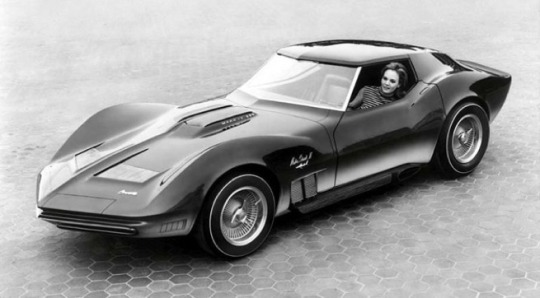

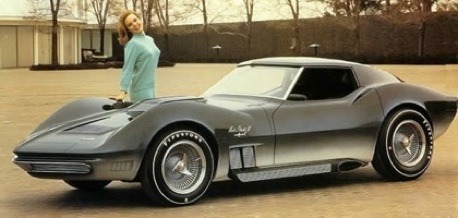

1965 Mako Shark II XP-830

The Mako Shark II show car made it's first public appearance at the New York International Auto Show in April, 1965. It's lines were the culmination of two beasts of the oceans, the Manta Ray and the Great White Shark. It was timeless. This one was truly a Bill Mitchell inspired car with the narrow waist or coke-bottle shape and pronounced fenders. Bill and Zora didn't agree on the design at first. But this was in the era when design came first and engineering then got to work within the major parameters we set.

There is always some confusion about the Mako Shark II based on different photos. There were, in fact, two primary versions of the Mako Shark II and then the Manta Ray version. So three basic versions with quite a few re-paints and minor changes over the years!

The first Mako Shark II, as shown at the New York show in January 1965, was a non-running model with the outside side pipes rising up into the front fenders. It also sported some interesting, futuristic details, such as a squared-off steering wheel.

The interior of the Mako Shark I got a lot of criticism, particularly the steering wheel which was a small rectangular piece with controls for turn signals and transmission built-in. By the Paris show this was changed to a more conventional wheel with the main controls moved to stalks o the steering column. Most of the 'informational" gauges were placed on the passenger side of the instrument pod, while the drivers side instrument panel had only the tach and speedometer. In addition to the gauges, there was also a system of warning lights for all major fluid levels and another series of lights to warn of open doors and the like.

The second Mako Shark II, first shown at the Paris Auto Salon in October of the same year, was a running model with more conventional rear-exiting exhaust system (left). The exposed ends of the exhaust were quite highly styled in a boxed and finned arrangement much like Larry Shinoda had done for the SS Racer.

It also had a retractable rear spoiler, and a square section bumper that could be extended for added protection.

There were other interior features which may yet come to pass as standard features. In Mako Shark I and II, the seats were fixed and the accelerator/brake pedals moved on a one-piece control board. Adjustable pedals have since been used on race cars and show cars; they may yet find their way to street cars as a way of increasing the "fit" for a wider range of driver sizes, especially as we come closer to acceptance of drive-by-wire features.

The Mako Shark II was powered by a 427 Mark IV engine, which became available on production Corvette models. The paint scheme continued the Shark I tradition, with blue/gray on top and silver/white on the bottom (along the rocker panels).

The were several core design elements which were common to both the non-running and running models, of course. The basic design included the chopped roof, hinged roof panel which raised to permit easier entry, the sharp-edged fender lines, highly styled front clip, hood bulge and upswept tail.

There were lots of other gadgets thrown on the car as repeats from Mako I, including the prism-type periscope rearview mirror, the pop-up brake flaps, James Bond retractable bumpers, and the louvered rear window treatment. When the car was converted to Manta Ray in 1969 the louvered window concept was dropped in favour of the more conventional sugar-scoop arrangement.

Initial high speed tests revealed that the car was unstable at high speeds. The nose was too low, the front fenders were too high and obstructed the drivers visibility. Rear visibility was next to nothing and the overall 'lift' of the car at speed was unacceptable. So much work needed to be done that there just wasn't enough time for a 1967 introduction for the new body style. 1968 would be the year that we would all see the newest Corvette. The front and rear fenders were more proportional, visibility was good, lift was minimal with the standard front air dam, and of course, the legendary 427 big block engine was available in 5 different versions.

In 1969 the running version of the Mako Shark II was converted to the Manta Ray.

(The information and pictures in this post comes from the blog of Mario van Ginneken and Remarkable Corvettes. Here is the link to their great work: https://www.corvettes.nl)

#Mako Shark II XP-830#mako shark#corvette#chevy#chevrolet#classiccars#car show#original concept#concept car#sports cars#bill mitchell#Zora#Zora Arkus-Duntov

189 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Automobile Club de France/5me Salon. 1902. Privat Livemont.

39 1/8 x 51 1/8 in./99.3 x 130 cm

Personifying the 5th Paris Auto Show is a regal-looking Art Nouveau goddess, proudly sitting at the helm of the latest open-air automobile. According to the side panel, bicycles, boats, and hot air balloons were also on view.

Available at auction June 26. Learn More>>

#art nouveau#belle epoque#decorative art#home decor#typography#typographic design#graphic design#lithography#lithograph#print#art print#original print#flowers#floral decorations#strong woman#powerful woman#woman driving#goddess#automobile#vintage automobile#grand palais#l'automobile club#crown#cycles#france#automobile club de france#vintage cars#driving#blonde#greek goddess

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

Y a-t-il du nouveau à l’horizon ?

27 mai 2020

Bon! Nous voici à, quoi?, la onzième semaine de confinement? Avec l’arrivée du beau temps, on sent toute une fébrilité chez les Québécois. Beaucoup de gens s’attendent à ce que la situation post COVID-19 soit le retour à ce que nous avons connu l’été dernier.

Je ne suis pas un devin mais je ne suis pas sûr qu’il y ait une amélioration avant septembre prochain (selon le Daily Mail, l’Angleterre serait alors revenu à la normalité). Et même là, la COVID-19 effectuera-t-elle un spectaculaire retour comme tant d’experts nous le prédisent? Je n’aime autant pas y penser !

D’autre part, je n’en reviens pas encore des réactions que j’ai vues suite à la publication de mes derniers blogues (ce qui est ironique, c’est que la plupart, voire même presque tous, me sont parvenus via Facebook ou encore mon adresse personnelle). Je crois avoir touché une corde sensible chez plusieurs lecteurs qui avaient déjà adopté certains hobbys (ou qui y sont revenus) et passe-temps reliés à l’automobile.

Merci à tous ceux qui m’ont transmis leur opinion ou leur goût concernant les films reliés à l’auto. Mais, curieusement, c’est surtout le dernier blogue, celui sur les miniatures, qui a connu une grande popularité. Parmi les multiples correspondances que j’ai reçues, j’aimerais souligner celle d’Yves Perreault, collectionneur de Laval qui m’a remercié de lui remonter le moral. Il était surtout inspiré par la photo du petit Midget (en miniature) qui lui rappelait un véhicule identique mais en grandeur réelle! Voilà un véhicule que j’aurais aimé conduire, ne serait-ce que quelques tours, sur une piste ovale courte. Non pas à haute vitesse mais suffisamment pour me donner le véritable «feeling» des autos de cette époque (1950 à 1960).

Autre collaboration à souligner, celle de Claude Rodrique qui possède un petit musée personnel (que l’on peut visiter suivant une réservation : https://youtu.be/d707eoE74Og) et qui a pris le temps de nous envoyer des photos d’une pelle mécanique qu’il est à reproduire en bois à l’échelle 1/25e!

Parmi nos lecteurs, il y a eu Claude Rodrigue, un passionné de mécanique à la retraite qui est un collectionneur averti de pièces mécaniques de construction et même de miniatures. Il nous a transmis cette photo d’une des excavatrices de son musée qu’il est à reproduire en bois à l’échelle 1/25e! Mais où diable trouve-t-il le temps de tout faire, lui qui est aussi très actif dans la société participant dans des œuvres de charité ? (Photo Claude Rodrigue)

Enfin, parmi tant d’autres, il y a eu les bons mots de Daniel Lynch du plus important groupe de maquettistes du Québec qui a bien aimé, lui aussi, le Midget. On s’aperçoit donc que le monde de l’auto s’ennuie des activités gravitant autour de ce sujet incluant des autos miniatures jusqu’aux véritables bolides de grandeur nature.

D’autre part, en voulez-vous un autre coup dur? Les organisateurs du Salon de l’auto de New York ont déclaré forfait pour 2020 et annulent maintenant leur date du mois d’août. Cet important salon aurait-dû avoir eu lieu quelques jours avant Pâques mais il a dû être déplacé à cause de la pandémie. On en avait annoncé une reprise au mois d’août…mais celle-ci vient d’être annulée vu que l’édifice qui lui servait de salle d’exposition, le Jacob Javits Convention Center, est devenu un hôpital et tout indique qu’il ne sera pas libéré à cette date.

Ce qui a été retardé…

Cette dernière annonce fait suite à celle de l’annonce de l’annulation du Super show extérieur qui aurait dû avoir lieu en juin à Detroit! En fait, nous avons été chanceux à Montréal d’avoir eu «notre» salon international avec ses nombreuses grands nouveautés. Même les Salons de Chicago et Toronto n’ont pas été à sa hauteur. Et depuis ce temps, plus de salons ! Selon mes calculs, on ne reverra pas de beaux salons de l’auto avant novembre prochain (ah oui! J’oubliais! Même le salon de Paris du mois de septembre est annulé!) à Los Angeles…Si salon il y a !

En feuilletant certaines publications spécialisées qui me parviennent (dont Automotive News), j’ai «rassemblé» les nouveaux véhicules qui auraient dû être dévoilés à ces évènements (excluant les Toyota Venza et Sienna qui ont été dévoilés par internet la semaine dernière et qui étaient mises en vedette dans ce blogue).

Évidemment, je dois encore une fois répéter le dévoilement repoussé du VUS Ford Bronco (et de son petit frère, le Bonco Sport) en plus de la possibilité du lancement du petit pick-up présumément appelé Maverick (ce qui relancerait la possibilité du retour du petit pick-up Chevrolet Montana commercialisé en Afrique du Sud jusqu’à tout récemment ou même le retour de la marque Dakota chez FCA (RAM)). Mais il y aurait dû aussi y avoir une annonce du VUM Tucson complètement redessiné (et l’on anticipe une version Kia Sportage) qui aurait dû être vu au Salon de Detroit version juin 2020. Certains journalistes américains auraient aussi vu une version N-Line de la nouvelle Sonata (que l’on verra probablement sur le marché en automne). Ah oui! Il y aurait eu la nouvelle Elantra redessinée ressemblant à la Sonata et la possibilité du pick-up Santa Cruz de la marque…

L’arrivée de mini pick-up Maverick de Ford incitera-t-il GM à relancer son Chevrolet Montana autrefois vendu en Afrique du Sud? (Photo GM)

On attend toujours le dévoilement du pick-up Santa Cruz de Hyundai qui, selon toutes probabilités, aurait un châssis rigide en échelle… (Photo du prototype Hyundai)

Pour en revenir à Ford, les recherchistes d’Automotive News n’ont pu tirer les vers du nez des représentants de Ford mais ils supposent qu’il y aurait eu quelques voitures électriques ou autonomes à démontrer en prototype. Incidemment, des Lincoln sur base de Rivian électriques sont, pour le moment, mis sur la glace.

La plus grande déception pourrait nous venir de General Motors qui a déjà annoncé une vingtaine de véhicules électriques pour 2023. Certains ont été dévoilés en privé à des medias en mars dernier mais, depuis ce temps, c’est «silence radio». On se doute qu’il y aurait eu quelques Cadillac au travers tout cela.

Cadillac aurait dû dévoiler son VUM électrique Lyriq en avril dernier…fort possiblement au Salon de New York. (Photo GM)

«L’autre» grand de Detroit, FCA, attendait le salon de Detroit en juin pour nous dévoiler, on s’en doute, de nouvelles Jeep dont la Grand Cherokee redessinée (dont il a déjà été question dans ce blogue), la supposée Wagoneer, la Grand Wagoneer et une autre Jeep à trois rangées de sièges. Évidemment, il y aurait eu des versions personnalisées des pick-up Ram dont la TRX qui serait la concurrence du Ford Raptor et la possibilité d’un pick-up intermédiaire Dakota tel que mentionné plus haut.

Le Ram TRX s’en vient-il ? (photo FCA)

Une autre grande présentation aurait été le dévoilement de la onzième génération de Honda Civic sous ses diverses formes. Mais, comme on connait ce constructeur japonais, rien n’a coulé à cet effet et il faudra attendre un évènement quelconque pour voir ces nouvelles Civic tout comme un tout nouveau Acura MDX qui est grandement dû pour un redesign d’importance et ce, malgré sa grande popularité.

Verrons-nous une version de production de ce prototype d’Acura ? (Photo Honda)

Il ne faut surtout pas ignorer Nissan qui est à se réorganiser en Amérique du Nord. Et le géant japonais devra d’abord le faire en nous présentant la nouvelle version de son très populaire VUM Rogue et celle du pick-up intermédiaire Frontier. D’autres importantes nouvelles devraient nous parvenir de Nissan au cours des prochains mois.

L’étude de style Sentinel serait-elle une prévision du nouveau Frontier à venir? (Photo Nissan)

Et si les Chinois nous envahissaient avec des pick-up?

On entend plus ou moins parler de l’industrie automobile chinoise sauf pour ses acquisitions qu’elle fait dans d’autres pays. On a bien vu de petites autos et des VUS intermédiaires à certains Salons (comme celui de Detroit l’année dernière) et certains camions commerciaux, surtout les autobus électriques BYD (Build Your Dream). Mais, jusqu’ici, les constructeurs chinois n’avaient pas encore montré beaucoup d’intérêt pour les pick-up très luxueux comme ceux que nous avons en Amérique. Sauf…

Sauf qu’en octobre dernier, le grand constructeur Great Wall (Great Wall , Grande Muraille pour vous, est un nom très populaire pour une foule de produits en Chine…j’y ai même bu du vin Great Wall à Shanghai,un «cabernetsauvignon»… écrit en un seul mot) a dévoilé au salon de Shanghai un grand pick-up élégant que l’on connaît sous le nom de P. (Pao en Chine) disponible en trois variantes, utilitaire, véhicule hors-route et…voiture de luxe.

Le Great Wall P. pourrait-il réussir sur le marché nord-américain? (Photo Great Wall)

Affichant une ligne qui nous semble familière (je vous laisse deviner), le P. serait plutôt de dimensions intermédiaires, comme le nouveau Ford Ranger ou le Chevrolet Colorado. Mais ce qui est plus fascinant, c’est que son constructeur croit que son usine où est assemblée la camionnette est capable de répondre à une commercialisation «mondiale» de ce produit livrable avec diverses configurations mécaniques incluant un moteur à quatre cylindres turbocompressé et une boîte de vitesses automatique à huit rapports et même la possibilité d’un moteur électrique.

Déjà vendu en Chine où il connaît une grande popularité, croyez-vous qu’il attirerait votre attention au point où vous en achèteriez un? (En passant, Ford vend des F-150 Raptor et Chevrolet des Silverado et Colorado en Chine mais, ces véhicules y sont considérés des objets de luxe donc sujets à de fortes taxes).

Donc, tout est à revoir en cette période de «déconfinement» plus ou moins organisée. Bonne nouvelle, cependant, les constructeurs ayant pignon sur rue au Canada ont commencé à remettre leurs «voitures de presse» sur route ce qui veut dire qu’éventuellement, je reviendrai à la formule habituelle de mon blogue avec des impressions de conduite. Mais cela ne se fera pas avant deux semaines, sinon plus. On recommencera alors à parler de bagnoles! Ouf!

0 notes

Photo

🇫🇷 Citroën DS Cabriolet Usine. En 1958, Henri Chapron présente un cabriolet sur base de DS lors du salon de l'automobile de Paris. Le succès est au rendez-vous. Les demandes se multiplient, et plusieurs autres DS cabriolet voient le jour, en séries très limitées. Témoin de l'engouement autour de cette auto, Citroën décide d'introduire cette variante dans sa gamme et confie la production à Henri Chapron. Le modèle usine sera présenté au salon d'octobre 1960. 🇬🇧 Citroën DS Cabriolet Usine. In 1958, a DS-based cabriolet was presented by Henri Chapron at the Paris Motor Show. The success of the car and the growth of the demand for the DS Cabriolet led to the production of several other models, in very limited series. Witnessing the craze for this car, Citroën decided to introduce this variant into its range and entrusted production to Henri Chapron. The factory model was presented at the October 1960 show. 📷 @TomAluni ➡️ Follow @CarrosserieLecoq & #CarrosserieLecoq #LecoqParis #ClassicCars #HenriChapron #Chapron #ChapronCars #Citroen #CitroenDS #DS #DSCabriolet #CitroenDSCabriolet #CitroenDSConvertible #ConvertibleDS #FrenchCars #VintageCars #LuxuryCars #AutomotiveHistory #DriveVintage #DriveClassic #Petrolicious #NostalGear (à Lecoq Paris) https://www.instagram.com/p/CAdc4ERFCRw/?igshid=tlo20pwurky9

#carrosserielecoq#lecoqparis#classiccars#henrichapron#chapron#chaproncars#citroen#citroends#ds#dscabriolet#citroendscabriolet#citroendsconvertible#convertibleds#frenchcars#vintagecars#luxurycars#automotivehistory#drivevintage#driveclassic#petrolicious#nostalgear

0 notes

Text

Their Car Beat Hitler’s Racers, but Who Owns It Now?