#Archaeological Museum of Piraeus

Text

Close-up: Piraeus Artemis B, early 3rd century BC.

Archaeological Museum of Piraeus, Greece

📷 E. Koronaios

#dark academia#light academia#classical#academia aesthetic#escapism#academia#books and libraries#classic literature#books#architecture#Piraeus Artemis B#sculpture#statue#bronze#3rd century#bc#Archaeological Museum of Piraeus#greece#royal core#cottage core#academics#antiquity#art#aesthetics#mood#vibe#tumblr

800 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today’s Flickr photo with the most hits: this statue of Athena in the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus. It was taken in 2007 when the archaeological museum was closed for renovation but when I rocked up at the door to gaze at the Piraeus Bronzes (ignorant and excited), staff took pity upon me and let in me to snatch a few photos. Such kindness.

0 notes

Text

wish the piraeus archaeological museum had a public catalog but hey everyone check out this c. 420-410 funerary stele from salamis with a tragic actor staring at his mask

#new mental image for the mask of apollo even though the dates arent right#the eternally open mouth of the mask facing the eternally closed mouth of the actor!#context is that i went looking for 5th century depictions of tragic masks to see if they had chins (they did)#bodycostume#mine

196 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Parthenon marbles this, the Parthenon marbles that...

I don´t know how known the extent of Greek antiquity looting by West Europeans is to most people or most have a limited image painting the British Museum or Lord Elgin as the sole / main villain.

Here we have the Piraeus Lion (Italian: Leone del Pireo) , one of the four lions decorating the Venetian arsenal in Italy. The prominence of the 3 meter tall lion statue in the port is such that it is also known as Porto Leone ("Lion Port").

We are eternally thankful for the massive courtesy of calling the statue the Piraeus Lion, indicating its origin from Piraeus, the port city of Athens. The statue was sculpted around 360 BC and remained a famous landmark of Piraeus, Athens until 1687.

In 1687, it was looted by Venetian naval commander Francesco Morosini, the man also notoriously responsible for the bombardment of the Parthenon during the wars of the Venetians with the Ottoman Turks, therefore in fact the most irreversible destruction it suffered in its 2,500 year long history. Somehow they were fighting the Turks but it was the Greeks paying for it.

Is it totally and universally acknowledged that Morosini illegally looted this sculpture among so many others? Yes. Does the Piraeus Lion still sit casually in the Venetian port in 2024 as if Venice has a shortage of artefacts to decorate itself with? Also yes. Meanwhile, the Greeks have to limit themselves to a replica in the Piraeus Archaeological Museum.

The Horses of Saint Mark in Venice are also Greek artefacts, this time looted from Constantinople during the crusades, although their original display was in Chios island. Another thing little known is how many ancient and medieval Greek artefacts were looted from the Eastern Roman / Byzantine Empire because people tend to focus on classical antiquities looted in the 19th century.

[Fun fact: The Piraeus Lion has runic inscriptions carved by Swedes in the 11th century. These were either Viking explorers or Varangian mercenaries of the Byzantine Empire.]

#greece#europe#greek culture#ancient greece#western appropriation#crusades#antiquity looting#ancient greek statues#piraeus lion#venice

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

Funerary Statue of a Dog, Pentelic marble, Piraeus (Athens, Greece), c. 375-350 BCE

currently in the collection of the National Archaeological Museum (Athens, Greece), accession no. 3574

this statue is often interpreted as the faithful guardian of the deceased human entombed below him

#archaeology#art#classical archaeology#isaac.jpg#greek#hellenistic#piraeus#funerary archaeology#funerary art#animal figures

544 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Piraeus Athena is a bronze statue dated to the fourth century BCE. It currently resides in the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus.

The statue is an over-life sized representation of Athena, with a height of 2.35 meters (approximately 8 feet).

356 notes

·

View notes

Text

you got your known Minoans and your unknown Minoans (part two)

(reposted, with edits, from Twitter)

(part one on Tumblr)

So, in Part One of this, I talked about the “Minoan” Boston Goddess statue and how she’s probably a forgery, and a little bit about how explicit Victorian archaeologists were that they wanted Minoan civilization to be a European civilization that was just as old and sophisticated as civilizations from Asia and the Near East.

Anyway, the Boston Goddess, Greek Gibson girl, delicate but dapper pre-Danaan dame...

She has no provenience. (I learned a thing: provenance is art, provenience is archaeology.) That is, she is without archaeological context. We don't know where she was found.

All those ecstatic articles about her are pretty cagey about where she actually came from. Caskey carefully says, allowing passive voice to do a lot of work, "according to information believed to be reliable, it came from Crete," and everyone else seems to have just run with that.

His successor as curator, Cornelius C. Vermuele III, who sounds like a walking Stiff Upper Lip, claims that the statue arrived via "a Greek-speaking Boston lady returning from the American School of Classical Studies in Athens," (natch, because she wouldn't have been the sort of lady to just vacation there).

Anyway, this Greek-speaking but safely Bostonian lady happened to befriend some Cretan immigrants in steerage--so enlightened--and they showed her the Boston Goddess--in fragments at the time--in a tin and she was like, HUP HUP MY DEAR SWARTHY FOLK YOU MUST TAKE THIS TO THE MFA.

And of course that was how it found its way into its proper home in a Boston museum--which of course purchased it for a "fair price"--and not with Greeks traveling in steerage.

No one at the museum could name this beneficient Boston lady who guided the figurine there, of course.

So then, another museum employee, Cyrus Aston Rollins Sanborn, who sounds like a walking handlebar moustache, tells the same story except now it's a male archaeologist befriending a lone Greek man in steerage. Everyone agrees on the "steerage" part, though, so that's something. Her fragments were maybe in a cigar box, maybe in a cigarette tin (the museum still has some fragments too small to be used in the restoration in a comely soap box), but I digress.

There weren't any ships sailing from Piraeus to Boston during the specified period, but it would be low-brow of us to concern ourself with things like facts about where one of the most important archaeological discoveries about the CRADLE OF EUROPEAN CIVILIZATION came from.

Anyway, I promised you I'd bag on Arthur Evans so let's do that:

Arthur Evans went to Crete looking or evidence of prehistoric European writing systems because he couldn't stand the fact that Middle Easterners invented our alphabet. (No, I mean, Mysteries of the Snake Goddess literally says: “he was hoping to prove early Europeans were no less literate than ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians.”)

Speaking of Crete, it was having a bit of a day back around the turn of the last century.

Until 1898, the Ottoman Empire ruled it

Until 1913, it was a protectorate of the Great Powers

After 1913, it was part of the Hellenic Republic of Greece

But they all agreed on one thing: STOP LOOTING THE PLACE AND CARTING OFF ALL ITS STUFF.

So unless something was a "duplicate" or insignificant, you had to turn it over to the authorities. But Arthur Evans was a Britisher, by golly, and wasn't going to be told what he could and couldn't do while hunting proof that Europe had always been just as sophisticated as Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

He'd already robbed tombs at Trier, skulls from Dubrovnik, and antiquities from Psychro, Trapeza, and Karphi. He knew that the archaeological importance of objects is deeply linked to their context, but considered rules about unauthorized digging "frivolous.” And he felt bad for collectors, rich people being stymied by all those rules--so, well, those rules would just have to be broken, even if that resulted in a "permanent injury to science."

In 1908, a Cretan customs agent caught him smuggling stuff he'd looted out of Crete. Rather than give it back, he tossed the package into the harbor.

He also got the customs agent fired.

In Part Three: this fine upstanding gentleman excavates the palace at Knossos, misplaced cats, fantasy worldbuilding, and Isadora Duncan being insufferable.

#archaeology#minoans#arthur evans#crete#white supremacist archaeology#snake goddess#art forgery#sketchy museum curators#mysterious greeks bearing gifts#mysterious bostonians bearing grifts#minoan

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's #NationalBirdDay so I want to talk about birds in mythology. There are many stories from ancient Greece about mythological birds and half-bird creatures.

Birds of Ares

The Birds of Ares (Ornithes Areioi in ancient Greek) were a flock of arrow-feathered birds which the god had set to guard his sacred shrine on the Black Sea island of Dia, also called Ares' Island. It had been built by the Amazons, his daughters. The birds were encountered by the Argonauts in their quest for the Golden Fleece. The heroes raised their shields as a defence against the birds' deadly volleys of arrows and with a clash of shield and spear scared them away.

The Birds of Ares were sometimes identified with the Stymphalian Birds driven off by Herakles (see below).

Griffins

The Griphoi or Griffins is a hybrid creature with the head and wings of an eagle and the body of a lion. They guard a treasure of gold by the border to Hyperborea. Griffins were popular decorations in ancient Greek art, for example the helm of the statue of Athena Piraeus:

Source: Athens, Archaeological Museum of Piraeus © 2014. Photo: Ilya Shurygin.

Harpies

The Harpyiai or Harpies were depicted as winged women, sometimes with ugly faces, or with the lower bodies of birds. They were the spirits of sudden, dangerous gusts of wind and were sent by the gods to snatch up people and things from the dark earth. A missing person was said to have been snatched by the Harpies.

Hippalektryon

The Hippalektryon, literally "horse-cock" or "horse-rooster" (hippos = horse, alektryôn = cock) is a hybrid creature with the head and sometimes forelegs of a horse and the wings, tail and back-legs of a male chicken. @sigeel drew them most beautifully, tended to by Demeter and Persephone.

Phoenix

This bird is still well-known today through the saying "rising like a Phoenix from the ashes". It was said to resemble an eagle, with feathers partly red and partly golden. The Phoenix flies from Arabia to the Temple of the Sun (Ra) in Heliopolis in Egypt every 500 years to bury its father encased in myrrh. And there only is a father because the Phoenix begets itself.

The tale of the Phoenix actually rising from its own ashes is related in a 4th century CE Roman text called "The Phoenix":

...the pyre conceives the new life; Nature takes care that the deathless bird perish not, and calls upon the sun, mindful of his promise, to restore its immortal glory to the world.

Straightway the life spirit surges through his scattered limbs; the renovated blood floods his veins. The ashes show signs of life; they begin to move though there is none to move them, and feathers clothe the mass of cinders. He who was but now the sire comes forth from the pyre the son and successor; between life and life lay but that brief space wherein the pyre burned.

His first delight is to consecrate his father's spirit by the banks of the Nile and to carry to the land of Aegyptus (Egypt) the burned mass from which he was born.

Sirens

The Seirenes or Sirens were depicted as birds with either the heads or entire upper bodies of women. They are well-known from the Odyssey for their enchanting song.

Lovely Terpsichore, one of the Muses, had borne them [the Sirens] to Akheloos, and at one time they had been handmaids to Demeter's gallant Daughter [Persephone], before she was married, and sung to her in chorus. But now, half human and half bird in form, they spent their time watching for ships from a height that overlooked their excellent harbour; and many a traveller, reduced by them to skin and bones, had forfeited the happiness of reaching home.

Apollonios Rhodios, Argonautika 4.892

The shape of the Sirens, a bird with a woman's head, was popular as a vessel for perfumes and cosmetics.

Stymphalian Birds

The Stymphalian Birds were a flock of man-eating birds of prey which lived around Lake Stymphalis in Arkadia on the Peloponnese. Herakles had to deal with them for the sixth of his twelve labours:

Herakles was stumped by the problem of driving the birds out of the woods, but Athena got some bronze noise-makers from Hephaistos and gave them to him, and by shaking these from a mountain adjacent to the lake frightened the birds. Not enduring the racket, they flew up in fear, and in this manner Herakles reached them with his arrows.

Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 2.92

The Stymphalian Birds were sometimes identified with the arrow-shooting Birds of Ares that were encountered by the Argonauts (see above).

According to Pausanias' Description of Greece there was also an old sanctuary of Stymphalian Artemis in Stymphalos and near the roof of her temple the Stymphalian birds had been carved.

Which is your favourite birb story from mythology?

#National Bird Day#mythology#Greek mythology#bird#birds#Demeter#Persephone#Harpies#Sirens#Phoenix#Ares#Helios#Ra#Artemis#Herakles#Heracles#Athena#Athene#Athene art#Greek mythology info

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unknown

_

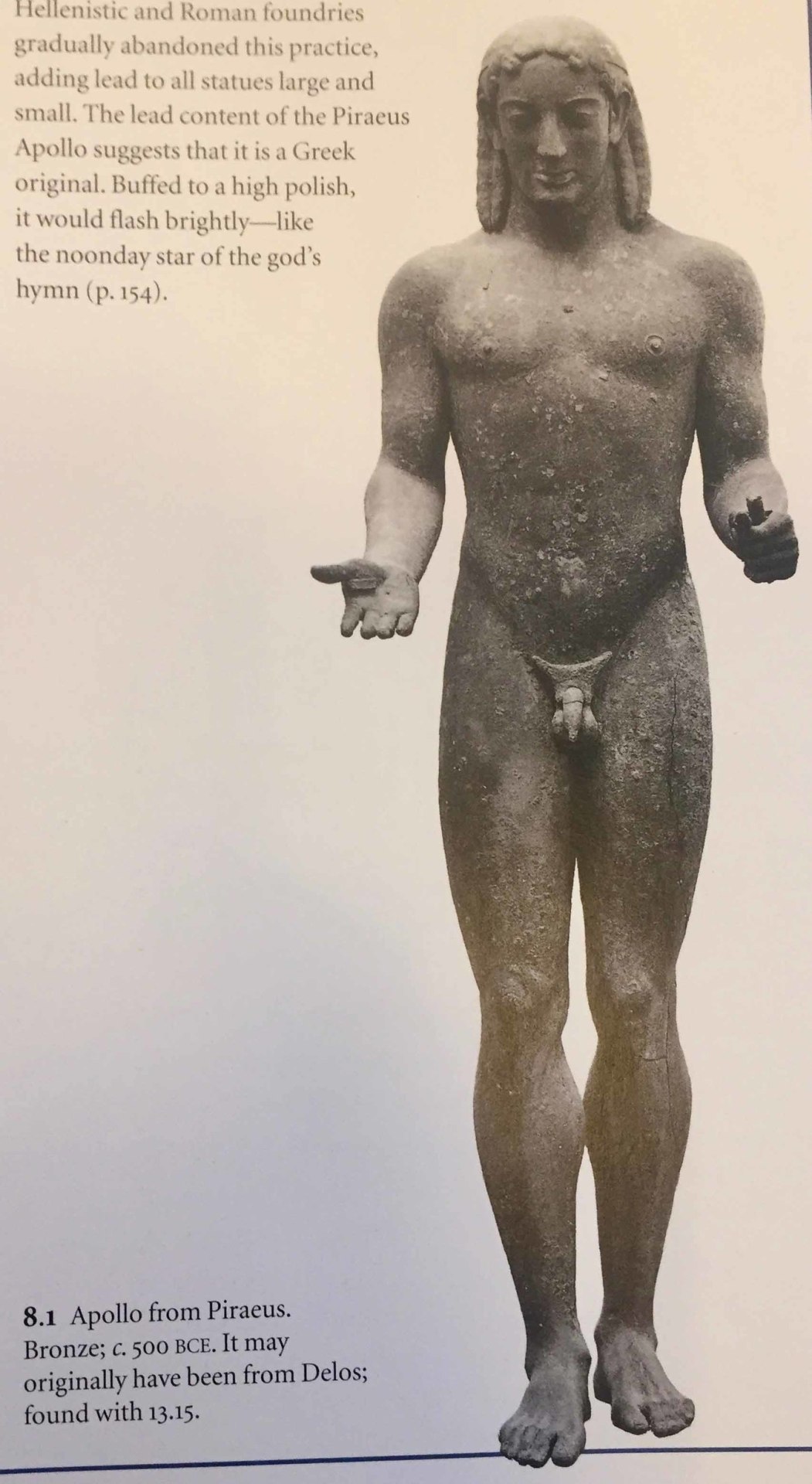

The Piraeus Apollo, 1.91 m cast High-Archaic style bronze, 6th c. BC (ca. 530–520 BC). Among the last of the kouroi, was excavated at Piraeus in 1959 in a votive pit together with the Piraeus Athena and two statues of Artemis. The figure shows increased plasticity and breaks away from Archaic tradition and is considered as product of a workshop of north-east Peloponnese, where bronze-working flourished during the second half of the 6th c. BC. Archaeological Museum of Piraeus, Athens.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piraeus_Apollo

https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/artifact?name=Piraeus+Apollo&object=Sculpture

http://odysseus.culture.gr/h/4/eh430.jsp?obj_id=4547

https://annemarie-harrison.com/en/a-few-greek-bronze-statues/

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

visited three museums in one day (archaeological museum of nafplio, bus to athens, metro to national archaeological museum, metro to akropolis museum, metro to piraeus).

how? i go through museums fast and i was only at the national archaeology museum in athens for pretty much four areas (mycenaean, neolithic-early bronze age, kykladic, antiquities of thera) even though a docent tried to convince me to go back and look through the rooms i just walked through when i asked her where the thera room was. i know where my interests like and they are all before 1200bce (okay i'll allow up to 1177, you're lucky eric cline).

had a discussion with one of the docents and another museum attendee about that diadem which i have been very curious about the actual construction thereof since i've learned of those tumulus/urnfield culture pointy gold hats and wondered if there were any similarities, especially in terms of calendrical significance and, especially, the construction. having now seen it in person, i am considering whether or not they may have been separate pieces, with the gold rays/spikes forming a pointed hat atop the head, and the diadem itself meant to be worn across the head.

the diadem itself is easy, it has two holes at the back pieces to be tied together, but the rays/spikes are thicker at the bottom, almost like the gold has been folded under itself and there's a little bit that would have formed almost a shelf, or wrapped around the base of something like leather (it's very hard to see even in person at the museum and i contorted myself into some interesting positions to try and see), forming a bit of a lip that would then fold beneath the lip of the leather base.

so:

hmm.

unfortunately all the relevant information seems to be in german from a first perusal. :/

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today’s Flickr photo with the most hits: the Battle of Greeks and Amazons - bas relief in the Archaeological Museum of Piraeus.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Greek ball player balancing the ball. Part of a marble grave stele, found in Piraeus, 400-375 BC. Item (NAMA) 873 of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

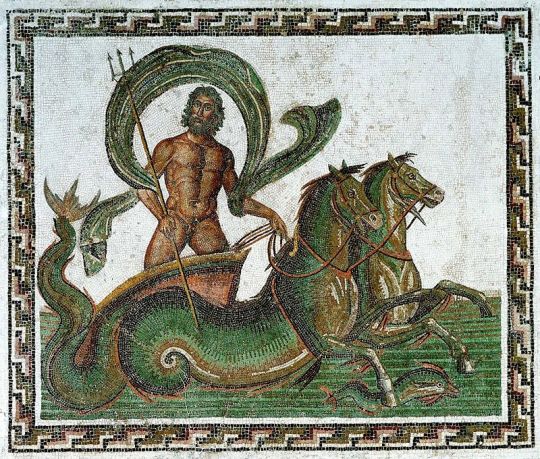

Neptune driving his chariot

Wild boar; Floor mosaic of the entrance to the House of Vesbinus (Casa del Cinghiale II). Date: A.D. 50—79. Photographer: Ilya Shurygin.

A Roman mosaic from Piraeus depicting Medusa, using opus tessellatum, 2nd century AD

Epiphany of Dionysus mosaic, from the Villa of Dionysus (2nd century AD)

Judgment of Paris, marble, limestone and glass tesserae, 115–150 AD

From Pompeii, Casa di Orfeo National Archaeological Museum, Naples

A Roman mosaic on a wall in the House of Neptune and Amphitrite, Herculaneum, Italy, 1st century AD

Mosaic from the impluvium of the House of Gometric Mosaics, Pompeii Roman, 1st century AD

0 notes

Note

Athens is the Top city to have ancient ruins. However are there other cities that have same important cites?

Numerous cities have archaeological sites, in fact it's the norm rather than the exception, however the ones in Athens are indeed the most concentrated / impressive / preserved ones.

In general, the following rules of thumb usually apply:

Most cities are excessively built on top of ancient settlements. As a result all of them have archaeological museums full of findings. In larger cities more of such sites have been rescued and are often monuments seen in various spots. In smaller provincial cities / towns, archaeological research was scarce in the past and as a result the ancient settlements remain underground. Research in these areas has started relatively recently and archaeologists have to also fight civilians who consciously hide the discovery of ancient sites and build on top of them in fear that they will lose their properties. It’s a big problem. However, lately we learn more and more in the news about new archaeological sites found constantly under unassuming towns and under towns which were previously believed to not have an ancient past. Unfortunately, we shouldn’t expect findings as majestic as in Athens because a) Athens was Athens, and b) the excessive ignorant construction on top of the ruins has of course taken its toll.

Several cities are not built exactly on top but in close distance to significant archaeological sites. Some of them are 5 - 20 minutes by car from the city. Often these types of sites are more important than ones found bruised exactly under the modern settlements. Technically Athens is a similar case, except it expanded so much that it eventually incorporated all the monuments within its city plan.

When sites are found but the ruins are deemed too destroyed to be worthy of opening up the space for the entire site, simply all individual findings and relics are taken and placed to a local archaeological museum and construction is resumed on top. Again this is the most common occurrence. Greece has 54 prefecture capitals and towns and a few more towns of considerable size. The archaeological museums are 205. This means that even random small villages have their archaeological museums and others are located close to archaeological sites into the nothingness.

So below I give as examples Athens and the next five largest cities, to show how it works more or less, because the case is a little different for each of them. Btw I am only mentioning monuments up to Roman era - nothing from Byzantine era and onward:

Athens (including many surrounding cities of Attica such as Piraeus, Eleusis and Megara full of monuments)

Thessaloniki (most of the ancient city is being excavated right now below the subway but it has already many large sites and monuments of Roman palaces, baths, arches etc)

Patras (ancient city, stadium, aqueduct, odeon inside the city and a Mycenaean acropolis and large Mycenaean cemetery just a little outside the city)

Heraklion (all ruins are in a museum, however the Minoan palace of Knossos and the maze are only 5km outside and there are several ancient settlements found in the respective prefecture)

Larisa (several ruins including two ancient theaters, the more impressive one of the two being exactly downtown)

Volos (minor ruins like ruined walls inside the city but several sites, theaters, beehive tombs and two of the oldest and most significant neolithic settlements of Europe in a short distance, a few minutes with the car)

#greece#Ancient Greece#ancient ruins#archaeological sites#travel guide#travel#tourist guide#anon#ask

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Little Stroll to the Archaeological Museum - Piraeus, Greece

Today we decided to walk from our apartment at Palaio Faliro to the Archaeological Museum in Piraeus - you can see the city of Piraeus in the distance in the picture above. We walked along the coastline, navigating our way through the various marinas until we reached a dead-end.

One of the marinas we had to go around on our way to Piraeus.

One of the side streets we ended up on, as we zigged and zagged our way through the town of Piraeus. We finally found our way to the main street and stopped for lunch at a little street cafe. We had a delicious lunch - Doug had a curry pasta salad and I had a sandwich with tomatoes, mozzarella, pesto, and rocket (new word for me - basically, arugula). I had my first Greek beer, Alfa, which was tasty. After lunch, we found our way to the museum. We didn’t have much time to browse, as our walk over ended up being almost 10 miles! But we were impressed with what we were able to see.

Remains from an urn found at the archaeological site.

Bronze statue of Artemis, mid-4th century BC. The condition of the statue is unbelievable, as well as the magnificence of the artistry.

One of the panels found in the remains of a shipwreck off the coast of Piraeus - they were being shipped from Piraeus to Italy (I think).

This statue was floor-to-ceiling in a room, it was massive. I believe this was a grave marker from Kallithea.

Portion of the Hadrian statue.

The museum closed at 5:00 and we were worn out from our long walk, so we decided to take the tram back to our apartment. It took us a bit to find our way to the tram station, but we did manage to successfully find it. Luckily, we had figured out Doug’s e-sim card by this time and we were able to use his phone to find the station. When we got back to the area near our apartment, we went to the wine shop we saw yesterday to purchase a bottle of wine for the evening. The owner of the wine store was delightful, patient, and passionate in educating us about Greek wines. We bought a cabernet sauvignon and agiorgitiko blend - it was lovely. Yamas!

0 notes

Text

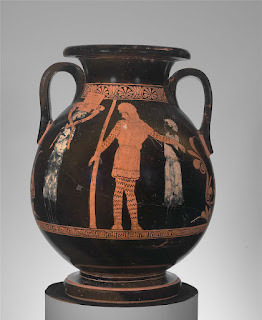

A young Black American Classicist talks about the depiction of Africans in ancient Greek pottery (and explains why Herodotus is his favorite ancient Greek)

“ Constructing the African: A Panoply Interview with Najee Olya.

We’re delighted to have the chance to speak to Najee Olya, a PhD student at the University of Virginia, USA, working on the dissertation, Constructing the African in Ancient Greek Vase-Painting: Images, Meanings and Contexts. Before beginning doctoral study, Najee earned a B.A. in Anthropology and Classical Civilization at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an M.A. in Classics at the University of Arizona. In the field, he has participated in archaeological excavations in Italy at Etruscan Populonia at Poggio del Molino, and since 2018 at Mt. Lykaion in Arcadia, Greece. Najee is currently a William Sanders Scarborough Fellow at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, researching vases in Greek collections and their archaeological contexts. The next academic year will see him take up a post as the Bothmer Fellow in the Department of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. In this interview, Najee offers insight into his research on Africans in ancient Greek pottery…

1) What contexts do you think ancient Greeks and ancient Africans are encountering each other in?

I think that the primary context would be in Egypt. Given that there are Greeks in Egypt in the Archaic period as mercenaries and at Naukratis, it must be there that Greeks are encountering not only Egyptians but people from elsewhere in Africa, especially from south of Egypt itself—what the Greeks generally referred to as Aithiopia (not to be confused with the modern state). I also suspect that major hubs of maritime trade would have been the sorts of places where Greeks encountered people from Africa, at various ports and emporia – trading posts - around the Aegean and the wider Mediterranean. Conversely, I’m inclined to think that direct contacts on the Greek mainland were somewhat limited. That said, in a major city like Athens, for example, the interest in Africans among potters and vase-painters seems to indicate at least some kind of familiarity with what Africans looked like that doesn’t appear to come from just seeing artistic depictions. Moreover, there were almost certainly foreigners and people of foreign descent working in the Kerameikos in Athens, so it's impossible to rule out that at least one or two may have been from Africa. There’s also Athens’s port at Piraeus, which saw a lot of traffic from a variety of traders and merchants.

Above, a janiform cup (ie. two heads back-to-back like the god, Janus), showing an African and a European, Attic c.500-450BCE, The Art Museum, Princeton University: 33.45.

2) Who are the Africans depicted in Greek pottery – what trends are there?

There are three categories, as far as I can tell, into which the Africans depicted in Greek pottery can be grouped. Two of these are fairly straightforward mythological episodes and scenes of daily life. The third is more difficult, and consists of imagery that doesn’t fit neatly into either of the two other categories.

In terms of the mythological episodes, the main figures from Africa are Memnon and Andromeda. The pair are both said to be royalty from Aithiopia in the mythological tradition. Memnon was king of Aithiopia and an ally to Troy in the Trojan War, where he led a huge army from Aithiopia before eventually being killed by the hero Achilles. Andromeda was an Aithiopian princess who was offered up as a sacrifice to appease the ketos serpent, a sea monster sent by Poseidon to ravage the coasts of Aithiopia after Andromeda’s mother Cassieopeia had boasted that she (Cassieopeia) was more beautiful than the Nereids. Andromeda was rescued by Perseus, and the two married. In vase painting, Neither Memnon nor Andromeda are shown as African themselves, but there are instances in the iconography where Memnon is shown preparing to depart for Troy attended by African warriors.

In the Andromeda scenes, she is shown being bound between stakes for the ketos monster, sometimes in Persian dress. There are Africans on a number of the Andromeda vases. There are some mythological traditions which associate Memnon and Andromeda with the Near East, so this might explain why they are not depicted as African themselves.

Above, Andromeda with African attendants, Attic pelike c.475-425BCE, Boston Museum of Art, 63.2663.

Next, there are depictions of the hero Herakles in Egypt and Libya. In Egypt, he encounters the pharaoh Busiris, who wants to sacrifice the hero to end a drought. On pottery Herakles is shown routing Busiris and his priests, who are always depicted as African men. In Libya, Herakles is accosted by the earth giant Antaios, who waylays strangers, forces them to wrestle, and then adorns the temple of Poseidon with their bones after he has killed them. Herakles defeats Antaios by lifting him from the ground as they wrestle and cutting him off from the Earth, from which he derived his strength. On pottery, physical contrast is shown between the two as they wrestle—Antaios has a long unkempt beard and hair, similar to Egyptian depictions of Libyans.

Above, Heracles fights Busiris, Attic pelike c.500-450BCE, Athens, National Museum: CC1175.

As for images from daily life, we have African stable-hands, warriors, and some attendants at the grave. These figures can generally be identified by their very curly hair and prominent noses. The last set of objects includes things like plastic vases, which show either full African figures or African faces alone or paired with women, satyrs, Herakles, and Dionysos. Finally, there are alabastra, a shape that rather circuitously made its way to Greece from Egypt, used for perfumed oil which depict African warriors.

Above, An African groom cares for a horse, Attic kylix c.490, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989.281.71.

3) Some Africans seem to be represented rather beautifully; other depictions feel a bit… off. What’s the balance between realism, idealism, and hostile caricature in ancient Greek depictions of Africans?

On the whole, I would say that most of the depictions are not hostile caricature. I can think of one example, a lekythos in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, which shows what seems to be an African woman being tortured by satyrs. There is also at least one image of a figure who may be African shown wearing shackles and is unambiguously an enslaved person. I do not think, however, that it is possible to definitively call either instance caricature.

Plastic vessels made in the form of African youths being attacked by crocodiles have sometime been interpreted as cruel, mocking images, but one can just as easily say that these show interest in the river Nile and awareness of its dangerous fauna. Aside from these examples, however, I think that many of the images are either ambiguous or benign. It is difficult to know what the representations were meant to convey to ancient Greek users. When it comes to realism, the images are realistic to a degree, but as with all ancient Greek art, it is superficial and illusory. Especially when it comes to pottery, I think that one has to remember that the medium and its convention limit just how true-to-life the representations can be. The end result is something of a pastiche of reality and imagination—the vase-painter selects the subject matter and then executes it in his own way, but the final product will always be constrained by things like the limited colour palette and the curving surface of the vase.

Above, an African youth attacked by a crocodile, Attic rhyton, c.350BCE, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge GR.58.1865.

4) Overall, what does pottery add to our understanding of ancient Greek ideas about Africans and Africa?

First and foremost, I think it reminds us that ancient Greece was part of an interconnected ancient Mediterranean. Also, that “ancient Greece” spanned three continents, with settlements and poleis not just in Europe but also in North Africa and Western Asia. Pottery tells us that ancient Greeks were interested in depicting foreign people such as Africans, and while it is difficult to interpret all of the different representations, it is clear that potters and vase-painters found Africans an intriguing subject, and that the purchasers of Athenian vases did too. The representations, in a general way, seem to indicate that Athenians were thinking about North Africa in particular, especially Libya and Egypt, where there were permanent Greek settlements. What they specifically thought about Africans is harder to determine from the pottery itself, but it does not seem to be the case that Africans were viewed any differently than other foreigners. Certainly, there was a general chauvinism toward non-Greeks, but Africans do not appear to have been singled out more than other groups, such as Persians or Scythians.

Above, An African in trousers, Attic alabastron, c.500-450, The J. Paul Getty Museum: 71.AE.202.

5) What would you like to see improved in terms of using pottery to increase general understanding of Black people within ancient Greek culture?

One thing that could use some improvement is the terminology used to describe the artifacts, which is often simultaneously both outdated and anachronistic. In scholarship this is due in part to the rather small corpus dealing with Africans on Greek pottery, much of which is several decades old now. Also, you will often see in museums or on museum websites descriptions that assume the depictions of Africans on vases are slaves, without any explanation, or descriptions that make use of discredited race-essentialist anthropology to discuss their physical characteristics.

I think that it’s extremely important to rethink how Greek vases with depictions of Africans are presented in museums, as those are the spaces where the wider public is most likely to encounter the artifacts. Some museums are already making efforts to rethink their use of language for the objects, such as the J. Paul Getty Museum and the North Carolina Museum of Art. I was recently asked by a curator at the latter to write a new label for an Athenian black-figure vase in their collection which has a depiction of Memnon and one of his African warriors. Hopefully the number of museums revamping their descriptions will increase going forward.

Above, King Memon with African attendants, Attic amphora by Exekias, c.575-525, British Museum, B209, previously 1849,0518.10.

6) Perhaps you could tell us a bit about your Fellowships – what they are, how they work?

I’ve been fortunate enough to have been awarded several fellowships that allowed me to study in Greece — from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA) and the American Philosophical Society (APS). I started out at the American School in 2017 with a scholarship for the Summer Session, which is a six-week course involving travel around Greece to archaeological sites and museums. I came back to the ASCSA two years later in 2019 with a fellowship to participate in the Regular Program, which is an academic year spent in Athens, travelling around Greece more than the Summer Session. Now, I’m wrapping up my third stay at the American School with a fellowship as an Associate Member. This time, I’m focused entirely on working on my dissertation and taking the opportunity to revisit artifacts in museums relevant to my research, in addition to obtaining special permission to photograph many of the vases outside of their displays.

I received a Lewis and Clark Grant from the APS in 2019, which allowed me to do field research in Greece. I travelled to archaeological sites that are documented as having had material from Egypt excavated there, created an archive of photographs, and got a better sense of the sites and their topography from first-hand observation. Finally, in September 2022 I’ll be at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for a year as the Bothmer Fellow in the Department of Greek and Roman Art. The fellowship will allow me to complete my dissertation and to access a number of the vases included in it, as well as the Met’s libraries. It’s worth keeping your eyes open to see what opportunities and funding are available.

7) Who’s your favourite ancient Greek?

It might be an obvious answer, but I will say Herodotus. I first read the Histories almost fifteen years ago as a Classics undergraduate, first in translation in a course taught wonderfully by Nanno Marinatos, and then in ancient Greek language courses. I think that it must be Herodotus’s interest in different cultures and his efforts to understand and make them legible for his readers that resonated with me, especially as someone who had already studied a bit of anthropology and archaeology before I came to Classics. As much as I enjoyed Herodotus years ago, I had pretty much left him behind until I selected my dissertation topic at the end of the first year working on the PhD. Since then, I’ve been revisiting him, as he famously writes about both Egypt and Aithiopia. I still read the Histories with a sense of wonder, but now I appreciate the complexity and sophistication of the work even more. Herodotus is one of the people from antiquity that I’d love to have a chat with if time travel were possible!

Many thanks to Najee for sharing his expertise!”

Source: http://panoplyclassicsandanimation.blogspot.com/2022/06/constructing-african-panoply-interview.html

Panoply is the blog of historian of ancient Greece Dr. Sonja Nevin and of animator Steve Simons.

1 note

·

View note