#3e concept

Text

#renault#renault r5#r5#turbo#r5 turbo#3e concept#concept car#history#historic#new car#new cars#fast car#ev#electric cars#cars#car

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

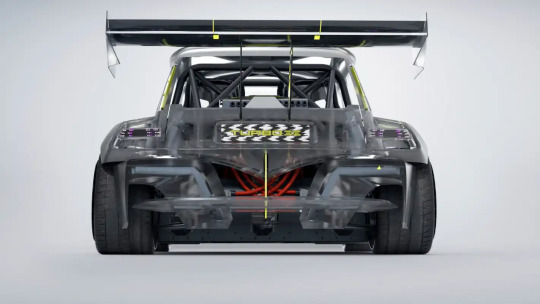

Renault R5 Turbo 3E, 2022. The drift-loving restomod 100% electric concept has been named ‘Best Retro EV’ at the Top Gear Electric Awards 2023

#Renault#Renault R5 Turbo 3E#restomod#concept#EV#electric car#design study#prototype#Top Gear Electric Awards

277 notes

·

View notes

Text

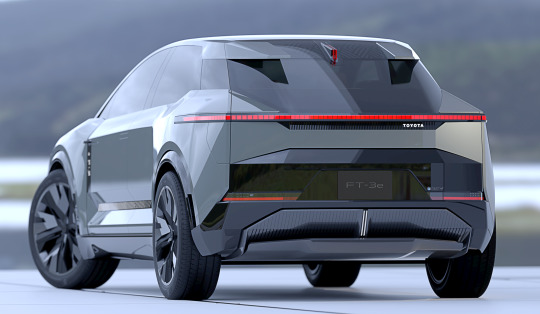

Toyota präsentiert Technik- und Designstudie FT-3e Concept

Mit dem FT-3e Concept erforscht Toyota die Design- und Technologiemöglichkeiten der nächsten Generation batterieelektrischer Fahrzeuge.

Basiert auf einer neuen Architektur für Elektroautos

Auf geringes Gewicht und hohe Aerodynamik ausgelegt

Digitale Anzeigen auf den Außenflächen

Hinweis: Es handelt sich um ein Konzeptfahrzeug, das noch nicht homologiert und noch nicht bestellbar ist.

Mit dem…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

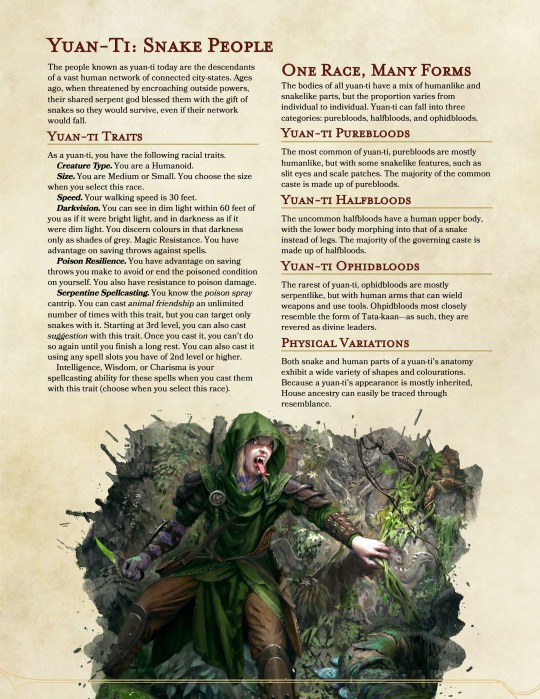

The Yuan-ti as a broad concept is full of interesting potential. However, Wizards of the Coast’s approach to the concept is heavily steeped in racism against Indigenous peoples of what is today considered Latin America—especially in particular, the Maya. The goal of this rewrite is to retain the Mayan coding while being more respectful of the real life people inspiration is drawn from.

An important note: While I am an Indigenous person myself, I am not specifically Mayan; I’m Mi’kmaw. As such, if there is any Mayan person reading this who has critique of my work, please feel free to express it, as I would greatly appreciate this.

My source of canon lore is the 5E books, Volo’s Guide to Monsters and Monsters of the Multiverse. I also took a little bit from the fanmade Forgotten Realms wiki, which as far as I’m able to judge, mostly consists of 3E lore.

[DOWNLOAD PDF]

130 notes

·

View notes

Note

I come to you on my hands and knees (relevant to the topic right lol) begging for any and all info on Bane, Banites and how it all ties in with Gortash. I love you in advance. <3

Bane and His Cult

Alright, so after twelve and a half hours of research I still don’t fully feel like I have enough, but at a certain point I just need to get this out there, and if there is anything you – or anyone else – would like to see explored in more detail, please feel free to ask!

Note: I love getting asks like this! There is such a vast quantity of Realmslore that having some sort of specific focus for my deep-dives is a huge help, and knowing the topic is of interest to others is a huge motivator. I also greatly enjoy getting to put my training as a historian to work, as there is so much to interpret and archive alike.

As ever, these writeups will align with current 5e lore, and draw from 3.5e for additional supporting information. On rarer occasions – and always noted – I will reference 1e and 2e, but with the caveats that there is much more in those editions that is tonally dissonant with the modern conception of the Forgotten Realms, and thus generally less applicable.

We’ll begin with one of the most recent conclusive descriptions of Bane, from the 5e Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide, an overview of the current world-state of, well, the Sword Coast:

Bane has a simple ethos: the strong have not just the right but the duty to to rule over the weak. A tyrant who is able to seize power must do so, for not only does the tyrant benefit, but so do those under the tyrant’s rule. When a ruler succumbs to decadence, corruption, or decrepitude, a stronger and more suitable ruler will rise.

Bane is vilified in many legends. Throughout history, those who favor him have committed dark deeds in his name, but most people don’t worship Bane out of malice. Bane represents ambition and control, and those who have the former but lack the latter pray to him to give them strength. It is said that Bane favors those who exhibit drive and courage, and that he aids those who seek to become conquerors, carving kingdoms from the wilderness, and bringing order to the lawless.¹

This gives us the briefest summation of what draws people to the Cult of Bane: the desire for power and control, often deriving from a sense that they lack exactly those two things. Bane is the quintessential deity of lawful evil, which – if you’ve read any of my previous posts on the sociology of the Nine Hells – bears a striking similarity to Baator itself, the realm of lawful evil, and the place where Enver Gortash spent at least a portion of his formative years.

The majority of the following excerpts derive from 3e, which went into far more detail on the specificities of the Faerûnian gods, including their dogmas, holy days, et cetera. One important point to note, however: any discussions of Bane’s scope of power are no longer accurate, as the time period in reference is about one hundred and twenty years before Baldur’s Gate 3 is set, at a time when Bane had just returned to life – and godhood – as nothing less than a greater god. By comparison, during Baldur’s Gate 3, he is a quasi-deity, having abandoned most of his previous godly power in exchange for the ability to directly meddle with Faerûn – forbidden to the gods by the overgod Ao – and gambling that he would be able to regain his lost power and prestige in so doing.²

The dogma of Bane – that is, the core tenets and philosophies that his followers seek to emulate – is as follows:

Serve no one but Bane. Fear him always and make others fear him even more than you do. The Black Hand always strikes down those that stand against it in the end. Defy Bane and die — or in death find loyalty to him, for he shall compel it. Submit to the word of Bane as uttered by his ranking clergy, since true power can only be gained through service to him. Spread the dark fear of Bane. It is the doom of those who do not follow him to let power slip through their hands. Those who cross the Black Hand meet their dooms earlier and more harshly than those who worship other deities.³

Even were there nothing else to go off of, this would tell us a great deal about the group dynamics of any followers of Bane, whether established church or fragmented cult. Just as in the Hells, hierarchy is everything to proponents of lawful evil. Any cult of Bane would have a strict order to its power structure, and there would be limited – practically nonexistent – tolerance for any questioning or insubordination of that order. To the minds of Banites, such is simply the natural and superior ordering of the world. These interactions are detailed below:

Within the church, the church hierarchy resolves internal disputes through cold and decisive thoughts, not rash and uncontrolled behavior. Bane’s clerics and worshipers try to assume positions of power in every realm so that they can turn the world over to Bane. They work subtly and patiently to divide the forces of their enemies and elevate themselves and the church’s allies over all others, although they do not fear swift and decisive violent action to help achieve their aims.³

The manner of tyranny that Bane holds to is similarly calculated – he is not interested in mere shows of force, but rather in insidious plots that twist and make use of existing rule of law to legitimize tyranny wherever possible. A social tide operated ostensibly within the laws of the land is far more troublesome to fight back against than a simple army.⁴

As far as specific ritual and day-to-day workings of the cult, some can be evidenced here, in broad strokes:

Bane’s clerics pray for spells at midnight. They have no calendar-based holidays, and rituals are held whenever a senior cleric declares it time. Rites of Bane consist of drumming, chanting, doomful singing, and the sacrifice of intelligent beings, who are humiliated, tortured, and made to show fear before their death by flogging, slashing, or crushing.³

In this sense, rituals seem most likely to be used as a display of power and a test of subservience, leaving lower-ranked members of the cult at the whims of their superiors, expected – as noted previously – to attend to their commands with the same alacrity they would use were Bane himself to speak. The rites themselves are designed to reinforce and glorify the primary aspects of their god’s domain: the tyranny of forcing submission and pain from the weak.

Faiths & Pantheons, published a year after the Campaign Setting supplement, provides a similar description of the rituals of the cult of Bane, along with some intriguing and flavorful additions (noted in bold for ease of comparison):

Their religion recognizes no official holidays, though servants give thanks to the Black Hand before and after major battles or before a particularly important act of subterfuge. Senior clerics often declare holy days at a moment's notice, usually claiming to act upon divine inspiration granted to them in dreams. Rites include drumming, chanting, and the sacrifice of intelligent beings, usually upon an altar of black basalt or obsidian.”⁴

As, in the “present day” of Baldur’s Gate 3, Bane has lost much of his foothold on power and his Faith’s old domains, the specifics of architecture of Banite keeps are no longer quite so relevant. However, in times past, when his Faith worked far more openly and held much greater power, the philosophy of Bane was expressed through the architecture of his churches and strongholds:

Tall, sharp-cornered stone structures featuring towers adorned with large spikes and thin windows, most Banite churches suggest the architecture of fortified keeps or small castles. Thin interior passageways lead from an austere foyer to barrackslike common chambers for the lay clergy, each sparsely decorated with tapestries depicting the symbols of Bane or inscribed with embroidered passages from important religious texts.⁴

The social capital of a Faith – a broad term used to encapsulate all followers of a single deity – is often heavily intertwined with the power of its god, a mutualistic relationship that runs in both directions. More social weight behind the Faith means its god’s name and will is conveyed to more people, some or many of whom might apportion some worship or act in alignment with that god and empower them by so doing. More power for the god means more divine actions that can bolster their own image and the reach of their clergy. At its height in the late 1300s, the Faith of Bane was one of the most prominent and powerful, with comparable might to that of a small kingdom.⁵

Something that is important to bear in mind in a setting such as the Forgotten Realms, not only polytheistic, but an environment where the gods being worshiped are demonstrably existent, is that the followers of evil gods are not likely to be obtrusive with the less savory aspects of their dogma. Not only would that, in the majority of cases, do more harm than good to their deity’s long term goals, in the words of Elminster:

A dead foe is just that: dead, and soon to be replaced by another. An influenced foe, on the other hand, is well on the way to becoming an ally, increasing the sway of the deity.⁶

All of this aligns with what we see of the Cult of Bane and its operation in Baldur’s Gate 3. While it does not have the same sway and might behind it as it did a hundred years before, through manipulation of law and carefully applied pressure – of whatever form most likely to yield the desired results, be it threats, bribery, blackmail, or use of hostages – Gortash has enacted a steel web of delicate, ensnaring tyranny across the entire city.

We can even find present-day expressions of the interactions of the cult members, and find that they hold true to what their forebears experienced, further proof of the consistency of lawful evil. A personal note found on the body of a dead Banite guard at the Steel Watch Foundry calls the Black Gauntlet in charge of the Foundry Lab, Hahns Rives, a “disgrace to the Tyrant Lord”, and notes the writer’s intent to “compile a list of Rives’ shortcomings for the Overseers.”⁷ These shortcomings include:

1. Rives failed to reprimand Polandulus for making jokes about Lord Gortash!

2. Rives missed the morning mass to Bane - twice!

3. Rives didn't punish Gondian Ofran when she missed her gyronetics quota merely because she'd lost a finger that day in the punch press.⁷

We can see evidenced here the constant scheming for position and recognition consistent with this manner of lawful evil hierarchy. Both devils and Banites orient their day-to-day lives around how to prove themselves to their superiors, while also undercutting them at any chance they have to prove their own superiority, with hopes of being raised above them.

This is only reinforced further by another text found within the Steel Watch Foundry, Bane’s Book of Admonitions. Its text is not written out for us, but described as such:

A book of adages and precepts for Banites, providing the basic tenets of worship of the Lord of Tyranny, with suggested prayers for common situations. The heart of the book is Bane's Twelve Admonitions, a dozen rules for proper Banite conduct, with punishments specified for failure to comply. The book opens easily to a page with two of Bane's most popular admonitions, number six, the Reprimand for Leniency, and number seven, the Rebuke for False Compassion.⁸

The most likely scenario is that this book was used by the “Overseers” referenced by the anonymous Banite writing of Rives above. The exact position of the Overseers is not made clear, but from context and knowledge of Banite hierarchy, we can infer that they inhabit a place in the hierarchy above both the guard and Rives himself, and that their role is to ensure all those below them uphold the tenets of Bane at all times, never losing sight of his will.

In that context, it makes sense that they would both have a book of specific punishments for specific infractions – rule of law, after all – and that, given the attempted report on Rives, punishments (“admonitions”) for the crimes of leniency and false compassion – and all compassion is false when your conception of the world does not allow for its existence – would be those most referenced. It would be incredibly important to the unity of the cult, as well as to Gortash’s plans, to harshly punish any observed leniency or break from Bane’s law among members of the cult.

Not only would failure to control the situation at the Foundry potentially spell failure for the schemes of Bane’s Chosen, any unpunished step out of line by members of the cult would be seen as tempting others to do the same, a trickle of dissent quickly becoming a flood. Better to ensure that all adherents live in merited fear of the consequence of failure.

After all, it is said of Bane himself: “He has no tolerance of failure and seldom thinks twice about submitting even a loyal servant to rigorous tortures to ensure complete obedience to his demanding, regimented doctrine.”⁴

And, in an appropriately lawful hierarchy, the same rule must apply from the bottom, to the top.

¹ Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide. 2014. p. 26.

² Descent into Avernus. 2019. p. 231

³ Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting 3E. 2001. pp. 237-8

⁴ Faiths & Pantheons. 2002. pp. 15-16.

⁵ Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting 3E. 2001. p. 93

⁶ Ed Greenwood Presents: Elminster’s Guide to the Forgotten Realms. 2012. pp. 135-6.

⁷ Rives’ Failures as a Banite. Baldur’s Gate 3. In-Game Text.

⁸ Bane’s Book of Admonitions. Baldur’s Gate 3. In-Game Text.

#voidling speaks#asked and answered#realmslore#meta#my meta#bg3 meta#bg3#bg3 gortash#bg3 bane#enver gortash#bane#baldur's gate 3#forgotten realms#cult of bane#d&d 5e#d&d 3.5

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Children of the Night: The Created (1999) is one of the very last Ravenloft books, so late in the line’s life that it barely even has the logo on the cover. By this time, Wizards of the Coast was essentially shutting down TSR in preparation for the new 3E era. You can feel a lot of that 3E energy in this book. I mentioned on Monday that, to me, 3E excelled at finding ways to combine old concepts in new and exciting ways. That is very much on display here.

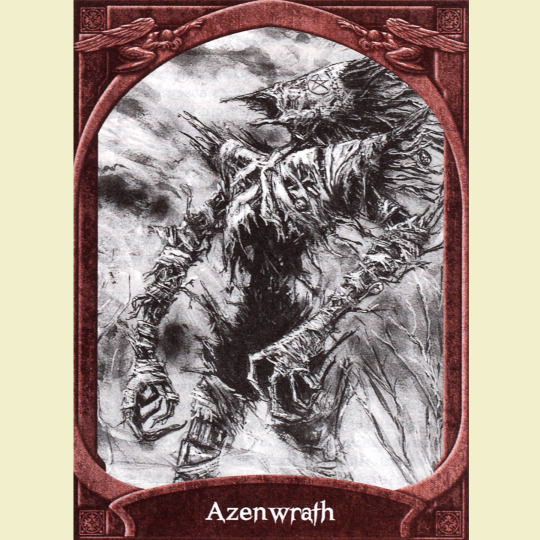

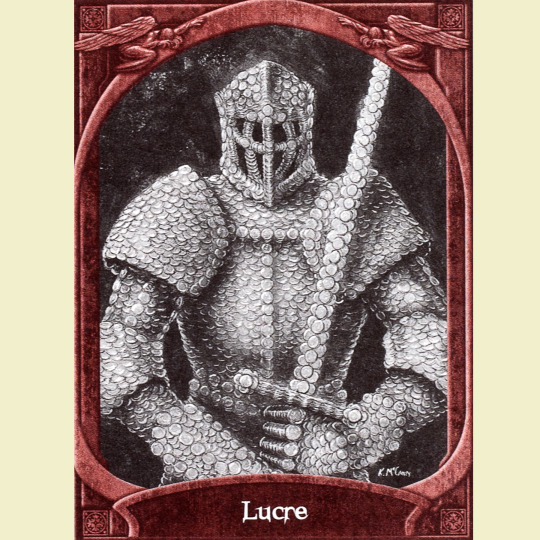

Here we have a clockwork man, a creepy wax work golem that recalls Vincent Price’s House of Wax (literally: that’s the name of the golem’s wax museum), a stained glass golem with personality, a golem made out of coins and more. My favorite is actually the cover golem, Azenwrath, a spell-rune construct made of sticks, paper and arcane symbols. It was once an evil treant that was killed, felled and turned into a number of wood-based products that retained fragments of its original personality and, gradually, came back together and reformed, not into a treant, but an insane eidolon forever searching for more pieces of itself. The adventure connected to it is very good, a nice bit of atmosphere whose solution nicely subverts D&D standards. The Lockwood cover is prettttty great. I like Kevin McCann’s work here as well — he seems to have developed quite a bit in the year since Werebeasts.

#roleplaying game#tabletop rpg#dungeons & dragons#rpg#d&d#ttrpg#Ravenloft#Children of the Night#Created

110 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's the relationship between CMWGE, Nobilis, and Glitch? The bits of understanding I think I've picked up so far are that they're all (diceless?) ttrpgs and are in vaguely the same setting but at least one's setting is an AU of another one's? They sound really cool, but really confusing, but really cool despite and/or because of the really confusing, and continuing to just pick up the random bits that tumbl my way is Not Enough. Help?

Okay!

Let's talk a bit about publishing for background

In 1999, Jenna Moran (formerly R. Sean Borgstrom) published the first edition of Nobilis through Pharos Press, resulting in what is often called the "Little Pink Book". This was a small run, and it proved successful/interesting enough to get picked up by Hogshead Publishing in 2002, resulting in the second edition of Nobilis, which is often called the "Great White Book". This is the one a lot of people think about when they think "Nobilis", and really put it on the map in the tabletop gamer consciousness. In 2011, the third edition of Nobilis was released through EOS Press. There was a lot of drama involving the publishers and distributors for the last two editions but that's not relevant to your question. Also, a fourth edition is in the works.

Chuubo's Marvelous Wish-Granting Engine (CMWGE) was released in 2015 after a successful kickstarter, initially through EOS Press and then through Jenna's own efforts and the support of a generous benefactor due to her separating from EOS for some of the aforementioned publisher drama. Its technically a multimedia project that also has two associated novels, The Fable of the Swan (2012) and The Night-Bird's Feather (2022).

Finally, Glitch: A Story of the Not was self published in 2022 after another successful kickstarter. This is the most recent of her games within the collective game line, sometimes referred to as "gluubilis" or "the Ash Tree Engine".

Why'd you tell me all that?

So you'd have context for this.

Mechanically, each of these games represents a development on the preceeding works; every later game iterates and develops on the previous games and concepts. This looks something like this

1e/2e Nobilis > 3e Nobilis > CMWGE > Glitch/4e

in terms of major mechanical divisions and advancements.

All the systems are diceless and there's a lot we could say here, but probably the biggest single innovation would be the introduction of Arcs and Quests starting in CMWGE, providing a strong narrative xp framework for all the future games to engage with and be built around.

In terms of the setting, all the games except CMWGE take place on the Ash-Tree Earth in which the universe is a big tree in a cup of fire that's presently at war with the forces of the Void. Nobilis explores play as the Nobilis, individuals empowered by the rulers of Creation to defend it against the Excrucians, the representatives of the Void. Glitch flips this around and has you play as one of those Void beings who used to fight in the war, but is now abstaining from it for any number of reasons.

CMWGE takes place in a world that was drowned in a sort of ontological uncertainty called the Outside. It's set in a possible future where the war of Nobilis and Glitch doesn't reach a conclusive end, but rather the world was cast into an interregnum during which any number of things are possible and also you can have slice of life adventures and shit. None of that background is actually necessary to know to play CMWGE, but I think it's enriching and also it'll help explain some of the various otherwise insane things we the players and fans will say about it. Again, though, nothing actually like. Holds you to that if you wanna do something of your own. CMWGE is notable for being the most customizable of these systems by far.

What's next?

A couple recommendations!

First, I'd recommend reading some of these games! Glitch and Nobilis 3e are imo the most accessible of the game books + they're ones still in use, but CMWGE is also absolutely worth checking out; just be aware that it's handing you a toolbox, so there's a lot more big chunks of mechanics to work through. Honestly, don't be afraid to skip around these books and look at whatever catches your interest. They're very rewarding reads! If you want to read fiction, The Fable of the Swan and The Night-Bird's Feather are both also really good starting points.

Next, talk with people about them! The scene is kinda scattered, but you can still find people on tumblr, Twitter, and cohost at the very least who're talking about this stuff. There's also an official discord and an older fan discord (you can ask me for an invite to that one) where people are pretty active.

Also, just, try playing the games! A lot of the apparent complications are a lot easier to parse and understand when you actually see them in play, and they're fun games.

Finally, don't be afraid to keep asking questions! Given the chance, a lot of us won't shut up about these games, myself included.

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

In which I sound off for much too long about PF2 (and why I like it better than D&D 5E)

So, let me begin with a disclaimer here. I don’t hate 5E and I deeply despise edition warring. I like 5E, I enjoy playing it, and more, I think it’s an incredibly well-designed game, given what its design mandates were. This probably goes without saying but I wanted it on the record. While I will be comparing PF2 to D&D 5E in what follows and I’ve pretty much already spoiled the ending by the post title (that is, PF2 is going to come out ahead in these comparisons most of the time), I don’t want there to be any misunderstanding about my position or intention. My opinions do not constitute an attack on anybody. For that matter, things I might list as weaknesses in 5E or strengths of PF2 might be the exact opposite for other people, depending on what they want from their RPG experience.

As I said before, 5E is an exceedingly well-designed game that does an exceptional job of meeting its design goals. It just so happens that those design goals aren’t quite to my taste.

# A Brief History of the d20 RPG Universe #

I’m going to indulge myself in a little history for a second; some of it might even be relevant later, but for the most part, I just want to cover a little ground about how we got here. By the time the late ‘90s rolled around TSR and its flagship product, Dungeons and Dragons, were in trouble. D&D was well over two decades old by that point and showing its age. New ideas about what RPGs could and even should be had taken over the industry; TSR had finally lost its spot as best-selling RPG publisher to comparative upstart White Wolf and their World of Darkness games; the company even declared bankruptcy in 1997. Times were grim.

That, however, was when another comparative newcomer, Wizards of the Coast, popped up and bought TSR outright. Flush with MtG and Pokemon cash, they were excited to try to revitalize the D&D brand and began development on a new edition of D&D: third edition, releasing in August 2000.

Third edition was an almost literal revolution in D&D’s design, throwing a lot of “sacred cows” out and streamlining everywhere: getting rid of THAC0 and standardizing three kinds of base attack bonus progressions instead; cutting down to three, much more intuitive kinds of saving throws and standardizing them into two kinds of progression; integrating skills and feats into the core rules; creating the concept of prestige classes and expanding the core class selection. And of course, just making it so rolls were standardized as well, using a d20 for basically everything and making it so higher numbers are basically always better.

At the same time, WotC also developed the concept of the Open Gaming License (OGL), based on Open Source coding philosophies. The idea was that the core rules elements of the game could be offered with a free, open license to allow third-parties develop more content for the game than WotC would have the resources to do on their own. That would encourage more sales of the base game and other materials WotC released as well, creating a virtuous cycle of development and growing the industry for everyone.

Well, long story short (too late!), it worked like fucking gangbusters. 3E was explosive. It sold beyond anyone’s expectations, and the OGL fostered a massive cottage industry of third-party developers throwing out adventures, rules material, and even entire new game lines on the backs of the d20 system. A couple years later, 3.5 edition released, updating and streamlining further, and it was even more of a success than 3rd ed was.

At this point, we need turn for a moment to a small magazine publishing company called Paizo Publishing, staffed almost exclusively by former WotC writers and developers who had formed their own company to publish Dungeon and Dragon, the two officially-licensed monthly magazines (remember those?) for D&D. Dungeon focused on rules content, deep dives into new sourcebooks, etc., while Dragon was basically a monthly adventure drop. Both sold well and Paizo was a reasonably profitable company. Everything seemed to be going swimmingly.

Except. In 1999, WotC themselves were bought by board game heavyweight Hasbro, who wanted all that sweet, sweet Magic: the Gathering and Pokemon money. D&D was a tiny part of WotC at the time and the brand was moribund, so Hasbro’s execs hadn’t really cared if the weirdos in the RPG division wanted to mess around with Open Source licensing. It wasn’t like D&D was actually making money anyway… until it was. A lot of money. And suddenly Hasbro saw “their” money walking out the door to other publishers. So in 2007, WotC announced D&D 4th Ed, and unlike 3rd, it would not be released under an open license. Instead, it would be released under a much more restrictive, much more isolationist Gaming System License, which, among other things, prevented any licensee from publishing under the OGL and the GSL at the same time. They also canceled the licenses for Dungeon and Dragon, leaving Paizo Publishing without anything to, well, publish.

At first, Paizo opted to just pivot to adventure publishing under the OGL. Dungeon Magazine had found great success with a series of adventures over several issues that took PCs from 1st all the way to 20th level, something they were calling “Adventure Paths,” so Paizo said, “Well, we can just start publishing those! We’re good at it, the market’s there, it will be great!” And then, roughly four months after Paizo debuted its “Pathfinder Adventure Paths” line, WotC announced 4th Ed and the switch to the GSL. Paizo suddenly had a problem.

4th Ed wasn’t as big a change from 3rd Ed as 3rd Ed had been from AD&D, but it was still a major change, and a lot of 3rd Ed fans were decidedly unimpressed. Paizo’s own developers weren’t too keen on it either. So they made a fateful decision: they were going to use the OGL to essentially rewrite and update D&D 3.5 into an RPG line they owned: the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. It was unprecedented. It was a huge freaking gamble. And it paid off more than anybody ever expected. Within two years Paizo was the second-largest RPG publisher in the industry, only behind WotC itself, and for one quarter late in 4E’s life, even managed to outsell D&D, however briefly. Ten years of gangbuster sales and rules releases followed, including 6 different monster books and something over 30 base classes when it was all said and done. It was good stuff and I played it loyally the whole time.

Eventually, though, time moves on and things have to change. The first thing that changed was 4E was replaced by D&D 5E in 2014, which was deliberately designed to walk back many of the changes in 4E that were so poorly received, keep a few of the better ones that weren’t, and in general make the game much more accessible to new players. It was a phenomenal success, buoyed by a resurgence of D&D in pop culture generally (Stranger Things and Critical Role both having large parts to play), and its dominance in the RPG arena hasn’t been meaningfully challenged since. It also returned to the use of the OGL, and a second boom of third-party publishers appeared and thrived for most of a decade.

The second thing was that PF1 was, itself, showing its age. RPGs have a pretty typical life cycle of editions and Pathfinder was reaching the end of one. It wasn’t much of a surprise, then, when, in 2018, Paizo announced Pathfinder 2nd Ed, which released in 2019 and will serve as the focus of the remainder of this post (yes, it’s taken me 1300 words to actually start doing the thing the post is supposed to be about, sue me).

There’s a coda to all of this in the form of the OGL debacle but I don’t intend to rehash any of it here - it was just like six months ago, come on - beyond what it specifically means for the future of PF2. That will come back up at the very end.

# Pathfinder 2E Basics #

So what, exactly, makes PF2 different from what has come before? There are, in my opinion, four fundamental answers to that question.

First: Unified math and proficiency progression. This piece is likely the part most familiar to 5E players, because 5E proficiency and PF2 proficiency both serve the same purpose, which is to tighten up the math of the game and make it so broken accumulations of bonuses aren’t really a thing. In contrast to 5E’s very limited proficiency, though, which just runs from +2 to +6 over the entire 20 levels of the game, Pathfinder’s scales from +0 to +28. Proficiency isn’t a binary yes/no, the way it is in 5E. PF2’s proficiency comes in five varieties: Untrained, Trained, Expert, Master, and Legendary. Your proficiency bonus is either +0 (Untrained) or your level + 2(Trained), +4 (Expert), +6 (Master) or +8 (Legendary). So if you were level five and Expert at something, your proficiency bonus would be level (5) plus Expert bonus (4) = +9.

Proficiency applies to everything in PF2, really - even more than 5E, if you can believe it, because it also goes into your Armor Class calculation. You can be Untrained, Trained, Expert, Master, or Legendary in various types of armor (or unarmored defense, especially relevant for many casters and monks), and your AC is calculated by your proficiency bonus + your Dex modifier + the armor’s own AC bonus, so AC scales just as attack rolls do. Once you get a handle on PF2 proficiency, you’ve grasped 95% of how any game statistic is calculated, including attacks, saves, skill checks, and AC.

Second: Three-Action Economy. Previous editions of D&D, including 5E, have used a “tiered” action system in combat, like 5E’s division between actions, moves, and bonus actions. PF2 has largely done away with that. At the start of your turn, you get three actions and a reaction, period (barring haste or slow or similar temporary effects). It takes one action to do one basic thing. “Attack” is an action. “Move your speed” is an action. “Ready a weapon” is an action. Searching for a hidden enemy is an action. Taking a guarded step is an action. Etc. The point being, you can do any of those as often as you have the actions for them. You can move three times, attack three times, move twice and attack once, whatever. Yes, this does mean you can attack three times in one turn at 1st level if you really want to (though there are reasons why you might not want to).

Some special abilities and most spells take more than one action to accomplish, so it’s not completely one-to-one, but it’s extremely easy to grasp and quite flexible at the same time. It’s probably my favorite of the innovations PF2 brought to the table.

Third: Deep Character Customization. So here’s where I am going to legitimately complain just a bit about 5E. I struggle with how little mechanical control I, as a player, have over how my character advances in 5E.

Consider an example. It’s common in a lot of 5E games to begin play at 3rd level, since you have a subclass by then, as well as a decent amount of hit points and access to 2nd level spells if you’re a caster. Let’s say you’re playing a fighter in a campaign that begins at 3rd level and is expected to run to 11th. That’s 8+ levels of play, a decent-length campaign by just about anyone’s standards. During that entire stretch of play, which would be a year or more depending on how often your group meets, your fighter will make exactly two (2) meaningful mechanical choices as part of their level-up process: the two points at 4th and 8th levels where you can boost a couple stats or get a feat. That’s it. Everything else is on rails, decided for you the moment you picked your subclass.

Contrast that with PF2. In that same level range, you would get to select: 4 class feats, 4 skill feats, two ancestry feats, two general feats, and four skill increases. At every level, a PF2 player gets to choose at least two things, in addition to whatever automatic bonuses they get from their class. These allow me to tailor my build quite tightly to whatever my idea for my character is and give me cool new things to play with every time I level up. This is true across character classes, casters and martials alike.

PF2 also handles multiclassing and the space that used to be occupied by prestige classes with its “pile o’ feats” approach. You can spend class feats from class A to get some features of class B, but it’s impossible for a multiclass build to just “steal” everything that makes a single class cool. A wizard/fighter will never be as good a fighter as a regular fighter is, and a fighter/wizard will never be the wizard’s match with magic.

Fourth: Four Degrees of Success. 5E applies its nat 20, nat 1, critical hits, etc. rules in a very haphazard fashion. PF2 standardizes this as well, in a way that makes your actual skill with whatever you’re doing matter for how well you do it. Any check in PF2 can produce one of four results: a critical success, a regular success, a regular failure, or a critical failure. In order to get a critical success on a roll, you have to exceed your target DC by 10 or more; in order to get a critical failure, you have to roll 10 or more less than the DC. Where do nat 20s and nat 1s come in? They respectively increase or decrease the level of success you rolled by one step. In practice, it works out a lot like you’re used to with a 5E game, but, for instance, if you have a +30 modifier and are rolling against a DC 18, rolling a nat 1 nets you a total of 31, exceeding the DC by more than 10 and earning you a critical success, which is then reduced to just a normal success by the fact of it being a nat 1. Conversely, rolling against a DC 40 with a +9 modifier can never succeed, because even a nat 20 only earns a 29, more than 10 below the DC and normally a crit failure, only increased to a regular failure by the nat 20.

Now, not every roll will make use of critical successes and critical failures. Attack rolls, for instance, don’t make any inherent distinction between failure and critical failure. (Though there are special abilities that do - try not to critically fail a melee attack against a swashbuckler. The results may be painful.) Skill rolls, however, often do, as do many spells with saving throws. Most spells that allow saves are only completely resisted if the target rolls a critical success. Even on a regular success, there is usually some effect, even on non-damaging rolls. That means that casters very rarely waste their turn on spells that get resisted and accomplish nothing at all. It also doubles the effect of any mechanical bonuses or penalties to a roll, because now there are two spots on a die per +1 or -1 that affect the outcome; a +1 might not only convert a failure to a success but might also convert a success to a crit success, or a crit fail to a regular fail.

# What About Everything Else? #

There is a lot more to it, of course. As a GM I find PF2 incredibly easy to run, even at the highest levels of game play, as compared to other d20 systems. The challenge level calculations work, meaning you can have a solo boss without having to resort to special boss monster rules to provide good challenges. I find the shift from “races” to “ancestries” much less problematic. PF2 has rules for how to handle non-combat time in the dungeon in ways that standardize common rules problems like “Well, you didn’t say you were looking for traps!” Everything using one proficiency calculation lets the game do weird things like having skill checks that target saves, or saves that target skill-based DCs. Inter-class balance, with some very specific exceptions, is beautifully tailored. Perception, always the uber-skill, isn’t a skill at all anymore: everyone is at least Trained in it, and every class reaches at least Expert in it by early double-digit levels. Opportunity Attacks (PF2 still uses the 3rd Ed “Attack of Opportunity” - but will soon be switching over to "Reactive Strike") isn’t an inherent ability of every character and monster, encouraging mobility during combats, and skill actions in combat can lower ACs, saves, attacks, and more, so there are more things to do for more kinds of characters. And so on.

Experiencing all of that is easiest just by playing the game, of course, but suffice it to say PF2 has a lot of QoL improvements for players and GMs alike in addition to the bigger, core-level mechanical differences.

# The OGL Thing #

Last thing, then. In the wake of the OGL shit in January, Paizo announced that it would no longer be releasing Pathfinder material under the OGL, opting instead to work with an intellectual property law firm to develop the Open RPG Creative (ORC) License that would do what the OGL could no longer be trusted to do: remain perpetually free and untouchable for anyone who wanted to publish under it. The ORC isn’t limited specifically to Paizo or to Pathfinder 2E or even to d20 games; any company can release any ruleset under it and allow third-party companies to develop and publish content for it.

Shifting away from the OGL, though, required making some changes to scrub out legacy material. A lot of the basic work was done when they shifted to 2E, but there are still a lot of concepts, terminologies, and potentially infringing ideas seeded throughout the system. These had to go.

Since this meant having to rewrite a lot of their core rules anyway, Paizo opted to not fight destiny and announced “Pathfinder 2nd Edition Remastered” in April. This is a kind of “2.25” edition, with a lot of small changes around the edges and a couple of larger ones to incorporate what they’ve learned since the game first launched four years ago. A couple classes are getting major updates, a ton of spells are either getting renamed or swapped out for non-OGL equivalents, and a couple big things: no more alignment and no more schools of magic.

The first book of the Remaster, Player Core 1, comes out in November, along with the GM Core. Next spring will see Monster Core and next summer will give us Player Core 2. That will complete the Remaster books; everything else is, according to Paizo, going to be compatible enough it won’t need but a few minor tweaks that can be handled via errata. So if you’re thinking about getting into PF2, I’d give serious thought to waiting until November at least, and maybe next summer if you want the whole Remastered package.

And that’s it. That’s my essay on PF2 and what I think makes it cool. The floor is open for questions and I am both very grateful and deeply apologetic to anyone who made it this far.

#RPGs#roleplaying games#d20#d20 history#pathfinder#pathfinder 2e#pf2#pf2e#dungeons and dragons#D&D#d&d 5e

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

D&D 3e introduced the concept of "templates" which allowed you to modify existing creatures and characters by basically slapping some extra abilities and features in it.

A very common use of these templates was to represent creatures that were partly supernatural. If you needed the stats for a creature whose parents were a dragon and an ogre you'd just slap the half-dragon template on an ogre.

The templates themselves already had implications about who could produce offspring with whom in D&D, yet once the Book of Erotic Fantasy came out featuring a full-page fertility table everyone acted all shocked.

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ulder Ravengard

have you met Ulder and gone dude why are you so mean to your son? do you want to write some fun angst for Wyll? well then do I have some meta for you.

This is a summary of the events of Murder in Baldur's Gate, the adventure that introduced Ulder + a lot of other plot points for BG3, plus some bits from his later appearances in Baldur's Gate: Descent into Avernus and Rise of Tiamat. MiBG isn't widely run, but this is heavy spoilers, so reader beware!

Murder in Baldur's Gate is an adventure very few people have heard of and also one of the most critical to the plot of BG3 (aside from Descent into Avernus which it was introduced as a direct companion/sequel to). It was part of the D&D Next playtest for 5e, and was written so that it could be played in 3e, 4e, or with the playtest rules, and is thus a really weird but fun adventure to run.

The core concept is this: Grand Duke Abdel Adrian (AKA Gorion's Ward AKA Charname from BG1/BG2) is attacked by the last remaining Bhaalspawn. One of them kills the other, and the survivor is turned into the Slayer, who the party is introduced helping to take down. What no one knows is that this also led directly to the resurrection of Bhaal, who proceeds to lurk in the shadows, manipulating events.

The main structure of the module is that there are three characters vying to take control of the city in the upheaval - Duke Torlin Silvershield who wants to consolidate power for the patriars and himself, Rilsa Rael of the Guild who's trying to start a populist uprising, and Ulder Ravengard, who's vying for the open Duke spot and trying to get the Flaming Fist more control over the city.

They're also all three touched by Bhaal, slowly driven over the deep end to drive the city into chaos. There are 10 stages, each with a mission from one of the three. If things go off as written (either because the party, working for that antagonist, did as they were told, or if they failed to intervene) they gain a rank of 'Bhaal's Favor' - with the winner ascending as the Chosen of Bhaal and wreaking havoc on the city.

Who is Ulder Ravengard at the start?

"Ravengard is not a zealot or a fascist - not yet, anyway."

Blaze Ulder Ravengard is the fourth son of a lower city smith, who is intensely loyal to the Flaming Fist, believing them to be the backbone of the city. He's repeatedly described as being disciplined, focused, and utilitarion. He has "no interest in domestic matters" and his soldiers respect rather than love him.

However, unlike most of the Fist, his goals are for the good of the city. He "seethes over the eagerness of ill-doers to control others, steal the fruits of honest folk's labor, and otherwise misuse hardworking people" - what manifests mainly in a crusade against the Guild, but he's no fan of the patriars and their corruption either.

Specifically, he plans to "wage war" against the Guild - and is aware that "wars aren't won without casualties or collateral damage" - pointing out his blind spot that "he excuses all actions taken for the public good while simultaneously deploring identical deeds that others carry out for less altruistic reasons"

Ulder's main flaw is that he thinks the ends justify the means, and that he's willing to do anything to protect the "honest" citizens of the city against crime. He's fine with intense methods if they produce results. That is to say, he's a cop.

To be honest my whole meta on Ulder really can be summed down with "ACAB" but we'll keep going anyways.

Murder in Baldur's Gate

It's Uktar 1482, at the Founder's Day celebration, and Grand Duke Abdel Adriain is dead. Ulder was his right hand, and was there for the death - but unarmed, because the Flaming Fist don't have authority in the Upper City, only the City Watch, who due to poor planning were too far away to do anything to help.

Ulder is the only one of the three antagonists to meet with the players openly, and invites them to Wyrm Crossing where he offers temporary membership in the Flaming Fist. His plan is to regain order, investigate the death (he thinks the Guild is behind it) and put himself up as Adrian's replacement.

Most of the module occurs in "stages" where each antagonist has their own plan going, which the party can either help or hinder.

Ravengard shuts down two gambling dens run by the Guild in the lower city, boarding them up and bringing the owners in for questioning.

Ravengard sends extra Flaming Fist to patrol the docks to check on workers from the Outer City he believe to be behind recent vandalism and tax robberies - they proceed to enact some police brutality.

Several statues (including the Beloved Ranger) are vandalized by a group of patriar youths. Whoever the party turns them over to gains a rank of Bhaal's Favor

Ravengard begins campaigning for Duke. Traditionally, the spot has ties to the Lower City and the Flaming Fist, but the Parliament of Peers wants a patriar instead - Wyllyck Caldwell. Ravengard blackmails Caldwell to get him to step away.

Ravengard convinces the Harbormaster to raise tariffs on luxury items (in response to the stage 2 sumptuary laws Silvershield enacts)

The Court of the Fist is set up - an illegal military tribunal where the Flaming Fist begin capturing suspected Guild members and sympathizers,

Ravengard closes down the Baldur's Mouth under suspicion the Guild is using it to communicate.

Rioting in the city breaks out, the Flaming Fist cracks down violently if the players don't intervene

Ravengard declares martial law. Not complying with the Flaming Fist is grounds for execution.

Ravengard sets up public executions. Over a hundred are killed within the first hour.

It Ends With Blood: if Ulder Ravengard is the Chosen of Bhaal, he reigns death on the city from above using the trebuchets in the Seatower of Balduran.

Event 10 occurs for the top two of Bhaal's favor, and Event 11 for the chosen - which is canonically Silvershield. So, we know events one through nine were at least ordered, even if circumvented - martial law is the only one that can't be averted.

Given that he ends up "winning" (becoming Grand Duke) I think the executions probably didn't happen (and instead Rilsa Rael staged her prison break) but it doesn't actually break canon.

Rise of Tiamat & Descent into Avernus

Sometime around or shortly before 1485, Ulder is named Grand Duke. 1485 is the year Wyll is banished for his pact with Mizora - which means he was only the Duke's son for maximum a few years.

In 1489, Ulder represents the city on the council to deal with the threat of Tiamat, where his traits are:

Ideals: Responsibility, glory ("I am trusted with protecting thousands of lives, and I will not betray that trust no matter what my personal desires.")

Interaction Traits: Honest

Pledged Resources: Flaming Fist warriors and expert advisers to train conscript troops

In Descent to Avernus, he's described as having been elected "backed by idealistic commoners and enemies of the other established dukes" and that his concerns are the "stability and prosperity" of the city. He's the "voice of reason and common sense" but not egalitarianism.

The central tenet of DIA is that Ulder Ravengard is an honorable man, and without him to keep the Flaming Fist in line, they exercise their power cruelly (guided along by Vanthampur as she tries to consolidate power)

In Elturel, Ulder has taken charge of the city's defense. You meet him as he has tried to recover a relic and been caught by a psychic attack from Baphomet, that is mostly grounds for him to give a lore drop.

Okay, that's a lot of information. Summary please?

Ulder Ravengard is a cop.

He's not a bad cop. He's not interested in power, wealth, or fame. He wants what's best for the city...and he believes that the Flaming Fist, with the right motivation and guidance are it.

But, like, he's still a cop. He's inflexible, and doesn't see much nuance in situations. He's Lawful Neutral, in a genuine sense, he believes in the righteousness of Order, and can't see the nuances or the downsides.

If he's a righteous man, why hasn't he put work into reforming the very corrupt Flaming Fist? Because Good Cops don't fix anything, and I don't think he actually has a problem with most of it. Sure, the punishment is extreme, but you were committing a crime - Mercy is a virtue for a judge to hold, but it isn't a right. He's more concerned with the corruption vis a vis bribes from patriars and the Guild than the police brutality angle.

He's a good man to have running your army. He's a good man to marshal your defenses as your city goes plummeting to hell. Grand Duke of Baldur's Gate? The only thing he has going for him is that everyone else is just as bad.

Of course he exiled Wyll - if you're not guilty, you have nothing to hide. There was nothing more damning than not being able to speak (which Mizora knew; she is, in fact, good at her job). Ulder's views of patriar corruption (and status as being from the lower city) also has him uniquely positioned to be very harsh - he can't be the person who lets his son's crimes slide, not and clamp down on the patriars doing the same thing.

But once he had the context, he accepted him immediately - the ends justify the means. Ulder Ravengard is a man who would make a deal with a devil to save his city...so long as he knows the price.

(now, on the 'leaving 17yo Wyll in charge...look, this gets complicated, but the only way it works is if he's put in charge of the Flaming Fist, not as 'heir to the Duke' mostly because Ravengard doesn't trust most of the Fist to not be corrupt. Even then, I think it's likely to be a bit more of Wyll's POV (I have to step up!) and less an official chain of command, but he could easily have been an official member).

There are definitely places with Wyll that you can see how he has and hasn't taken his father's ideology. He's got some naive views (Baldur's Gate, welcoming refugees??) that suit someone who was taught the theory but never actually practiced politics, but he definitely has a leaning towards some of Ulder's views about law and order and ends and means.

And as for Grand Duke Wyll Ravengard, well....

...let's just say, with the right people pushing buttons, I could see him going down the 'declare martial law' route too.

#ulder ravengard#wyll ravengard#wyll bg3#bg3 spoilers#bg3 meta#bg3#baldur's gate 3#baldur's gate 3 spoilers#baldur's gate 3 meta

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

2022 Renault R5 Turbo 3E concept

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

#renault#renault r5#r5#turbo#r5 turbo#3e concept#concept car#history#historic#new car#new cars#fast car#ev#electric cars#cars#car

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

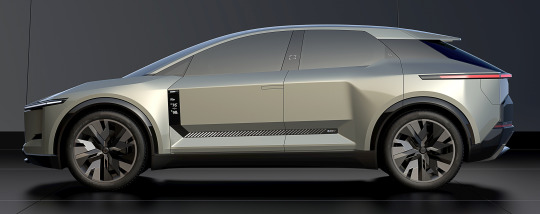

Toyota FT-3e Concept, 2023. A prototype for a next generation BEV that was presented at this year's Japan Mobility Show. Digital displays running from the lower side body to the upper door provide information, including battery charge, onboard temperature, and interior air quality when the driver approaches the car.

#Toyota#Toyota FT-3e#concept#design study#prototype#BEV#electric car#futuristic#Japan Mobility Show#2023#hatchback

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Retrospective: D&D 3e class feature advancement and design

Of the editions of D&D that I've played, I think Third Edition is my favorite. It's imbalanced, sure, but part of what differentiates D&D from videogames is that there's a DM on hand to say "let's change that". Much of the general success of 3rd was probably due to the Open Gaming License that you may recall a recent fuss about, and two specific impacts of the OGL were 1) explosion of fan content to add on and change stuff, 2) fanmade polish of the System Reference Document (SRD), such as this hyperlinked and crosslinked version where just about everything is accessible in one click. Much less searching for rules!

I also personally liked it for the unusual way it tried hard to put player characters and monsters in the same mechanical framework using the same scale, unlike far too many games, video or tabletop, where the PC has 138 HP but does 9999 damage. (This was to some extent present in earlier editions, but 2e's Monstrous Manual fails to give a creature's Strength score, only specifying its damage directly.) D&D in general was unusually fair and honest about letting you loot Lord Mega-Evil's Mega-Sword instead of doing "2% drop chance" shenanigans. 3e went a step further to making the bugbear playable out of the box, if you wanted to play a bugbear. Bugbears were now real creatures in a sense, not simply bags of HP you popped for XP.

If you're waiting for me to get to the subject announced in the title, just keep waiting, this is a twenty year old game and I'm a grognard with a pet topic. ;-)

4th edition decided to strip much of this stuff back out again, and I detested it. 4e was super weird. 5e tentatively tried to be the simplified best bits of 1e and 3e (IMO) which is nice for the newbies, but I feel its class system still leaves much to be desired. The whole notion of "classes" in a RPG is a bit of a necessary evil. It doesn't exist in-universe, it's an abstraction because doing full pointbuy is more tiresome for players and far easier to accidentally break the system by neglecting one stat or pushing another too high. At the same time, you don't want to lock characters into a progression at level 1, so designers tend to re-invent various class options and class choices that veer back towards pointbuy, and multiclassing...

Bluntly: The "favored class" rules and multiclassing xp penalties in 3rd were failures. The hypothesis was that it would discourage "5 levels of this, 1 of this, remaining levels of this" cherry-picking and encourage keeping 2-3 classes balanced, with an exception for the favored class. What it actually encouraged was "5 levels of this, 1 level of this prestige class, remaining levels of this prestige class" because prestige classes (PrCs) were exempt. Removing that exemption would have had worse second-order effects because prestige classes had different numbers of levels and conditional advancement permission! A deeper overhaul was needed, but didn't appear. My groups usually ended up ignoring multiclassing xp penalties. Worthless rule, no content, no value. Especially the bit where it's possible to get stuck at -100% XP if you made deliberately bad choices, that's nonsense.

What was also a failure, but less so, and produced the content I want to ramble about today, is how the class system incentivized multiclassing in very different ways for different classes. I'm going to gloss over questions of obscure splatbook availability and optimization level here; if you know enough to have an opinion on them you probably don't need to be reading this.

-

Fighter: Multiclass out or prestige class ASAP. This because Fighters have no class features that scale specifically with Fighter level - feats, BAB and HP can be gotten anywhere, and stack cleanly from different classes. Fighter 4 / Barb 1 / PrestigeClassA 5 / PrestigeClassB 10 is an example outcome of starting from "Fighter" and keeping the concept without being bound to the classname.

Sorcerer: Prestige out, but only to +1 caster level classes. Sorcerers have 1 scaling class feature, "spellcasting", which is advanced as a whole by several prestige classes. Something like Sorc10 / Loremaster 10 is cool, gets you 20th level casting, and more class features.

Druid: Stay pure. Druids have multiple scaling class features, and very few prestige classes advance other than spellcasting.

(I reiterate: this is what the class system incentivized. Not what you 'should' play.)

-

This difference was not a matter of party role, but of class feature wording.

Broadly speaking, there's two kinds of class features in 3rd Edition: those that provide a static ability at a fixed level (for example, Paladins become immune to fear at 3rd level) and those that have a progression scaling with each level (for example, Paladins can Smite Evil to add their level to the damage done).

Fighters got almost entirely static abilities, and those with diminishing returns. Spellcasting was almost entirely scaling.

Paladins were closer to the Druid end of the scale due to Smite Evil and Lay on Hands saying "paladin level" (not caster level, nor character level) when calculating what to scale with. A few prestige classes explicitly advanced these features, but there was no standard framework for advancing them the way the Thaumaturgist prestige class had "+1 level of existing spellcasting class" for any of druids, clerics, wizards or sorcerers.

Theoretically, the Thaumaturgist or Mystic Theurge prestige classes also worked for other spellcasting classes such as Paladin, but this was mostly worthless because paladins were tertiary casters who got slower per-level spellcasting progression. +1 level of spellcasting had lower value for paladins or bards than it did for clerics or wizards. This was aggravated by partial progression classes such as Eldritch Knight, which provided less spellcasting advancement - measured in terms of fewer levels. They got community shorthand like 9/10 or 7/10 casting progression.

An intuitive-seeming fix haunted me for years: PrCs that give partial advancement to full casters should give full advancement to partial casters. Perhaps even more than one-for-one when advancing tertiary casters. But it was hard to spell out in rules.

Instead, WotC printed special case ugly hack PrCs like the Sublime Chord, which was blatantly "The Bard Prestige Class For Bards" that gave faster-than-bard spellcasting progression up to 9th level bard spells. (In the core game, wizards get up to 9th level spells, but bards stop at 6th level.) It worked by specifying in detail a new separate spellcasting progression meant to be used at each level from 11 to 20, after using the regular bard progression from level 1 to 10.

Ironically, this special case could then fit back into the standard framework: take 10 Bard levels, take 1 Sublime Chord prestige level, now Sublime Chord has its own spellcasting progression so it can be advanced by other prestige classes such as Loremaster or Thaumaturgist. Sublime Chord was a prestige class that bards took mostly for the spellcasting, and then they didn't need to stay in that class for the spellcasting, because spellcasting was a standard class feature that could be advanced in other ways.

What a mess.

-

Still, I gotta give Wizards credit for being willing to fuck around and try new stuff to get out of this mess they'd made.

During 3rd edition, some of their later pile-ons to this mess were the Truenaming magic system that worked based on a skill check instead of levels (this was swiftly exploited because Make Single Number Go Up is easy for nerds with a wide variety of options), the Shadowcasting magic system that got to retroactively convert the class levels of a wizard who multiclassed into shadowcaster (I never saw this used in practice), and the Initiating not-a-magic system in the Tome of Battle:

Instead of caster levels you had initiator levels, and instead of casting a spell you initiate a martial maneuver, and the maneuver involved swinging your sword around so expertly that it shot fireballs or healed your friends or added an extra 8d8 damage or froze the enemy's lifeblood with the Five-Shadow Creeping Ice Enervation Strike. It also let you resist poison or block mind control by concentrating really hard on how you are a mall ninja One with the Blade.

(image: a Blade Magic user who has convinced the DM that hitting people with your bare hands counts as a 'blade' if you call it Knife-Hand Strike.)

It was actually pretty good, once you got past the flowery names, the weeaboo aesthetic shift, the increased complexity, the dissociated mechanics, and the fact that Wizards printed three initiator subsystem classes that were different enough to be annoying. Now that I'm done damning it with faint praise: you calculate multiclass initiator level by taking your main initiator class's class level and adding half the levels in other classes, whether or not they are initiator classes. A Swordsage 6/Fighter 6 character counts as Swordsage 9 for purposes of the Swordsage's primary class feature: initiator level and martial maneuvers.

This sort of worked to encourage a moderate amount of multiclassing on occasion by reducing the cost, but not really, because of nonlinear scaling. The low-level Swordsage abilities are on the order of "Fighter but with 1d6+1 fire damage".

The high-level Swordsage abilities are like "Enemy has to make a Fortitude save or die. On a successful save, enemy still takes 20d6 extra damage on top of your regular damage" and "Quasi-timestop: you get 10 opportunities in a row to pick up a nearby enemy and throw him. Your choice whether you want to throw 10 guys off a cliff, or bounce 1 guy against the wall until he dies."

This class feature progression was cribbed from the core spellcasting system for Sorcerers and Druids, see above for the multiclass incentives on those.

-

I don't have a general solution. Here is my sketch of a fix to the spellcasting part, also usable with the cribbed-from-spellcasting class features like initiator progression:

Build a spellcasting progression separately from a class. Each progression goes up to 9th level spells at character level 20, or the system equivalent. The "Wizard" class then gets a class feature which says something like "+1 spellcasting progression at each level". The "Bard" class gets a class feature which says something like "+0.75 spellcasting progression at each level". The Paladin class get a class feature which says something like "+0.4 spellcasting progression at each level". Round up or down with minima to taste.

This replicates the effect of the 3e progression where the Wizard got up to 9th level spells, the Bard got 6th and the Paladin stopped at merely 4th.

But by separating the spellcasting progression, all these base classes get the same amount of benefit from a Prestige Class which provides +X spellcasting progression per level (X probably 0.5-1). In regular 3e, spellcasting progression classes were worth far more to the wizard than to the paladin, because the paladin got 1/20th of a step towards 4th level spells and the wizard got 1/20th of a step towards 9th level spells.

This eliminates the weird special case that is the Sublime Chord, also eliminates certain other kinds of dumb cheese around Ur-Priest, creates space for semi-focused casting prestige classes that provide 0.9 spellcasting that's an improvement for bards but a slowdown for wizards, and makes it easier for Fighter-adjacent and Rogue-adjacent classes and prestige classes like Assassin to dabble in a little bit of spellcasting at a controlled rate. In weird design space, it allows backloading on a class that goes from +0.5 to +1.5 over the course of several levels to "catch up".

A downside is that this "fractional casting" is more granular, more bookkeeping, and closer to pointbuy, but it's a small step and D&D 3.5 was already including the similar Fractional BAB/Saves in optional rules. Maybe someone can be inspired by this to make something easier.

-

Now I would like to say that D&D Third Edition has come and gone and will probably never be repeated, having been supplanted by two later editions twenty years on, especially 3.5e with all its baroque customization, but that would be a lie because not only did it spawn a great many clones, Pathfinder is out there being a big name 3.5e clone with just enough tweaks to not be a copyright infringement. (Also: just enough tweaks to not quite be backwards compatible.) So I feel I should try to give helpful advice for design of class-based RPG systems, rather than just this historical overview so far. Here's my big suggestion:

Figure out how a class offers value, and why I should keep taking it.

The D&D 3e Fighter fails this test. You should multiclass out. Full BAB, d10 HD, crappy skills, Fortitude save (more chassis than feature) are available elsewhere. Feats (the only real feature) have diminishing returns.

The Pathfinder Fighter still fails this test - it's been given tiny value buffs like the scaling effect of Weapon Training: for every 4 levels get +1 to damage with a weapon group. Meanwhile the wizards are still off getting caster levels that give +1d6 spell damage every single level, and it's easy to get 1 damage every 4 levels from other sources.

Also, the Pathfinder Fighter has been given a Bravery feature: +1 on saves against fear for every 4 levels. Meanwhile the Paladin is still getting outright fear immunity at level 3.

The converse of this suggestion is asking yourself in design: Which of a class's valuable features can I get elsewhere?

For the Fighter it's "all of them", for the Sorcerer it's "all of them, but fewer places" and for the Druid it's complicated but "one-third" is a first approximation.

Extra corollary: "...and if getting those features elsewhere, what am I giving up or getting on the side?"

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

Top 5 denizens of the Hells (from any setting)

Okay, besides me fawning over Raphael on @archcambion, I felt I should talk about my top five favorite loves of the Hells.

Thank you so much, @dujour13, for letting me info dump!

5. Glasya, the Archdevil of Malbolge (D&D)

The only child of Asmodeus, Glasya has always been in the side lines of D&D since it's inception, a bit of a minor player with she severing as a consort for an edition or two for Mammon. In late 2e and in 3.Xe, Glasya became such a political issue for Asmodeus, he bumped her to Archdevil to give her more work and to use in political maneuvering. Glasya still is the most chaotic of the Archdevils, focusing on her criminal empire within the Hells, and befriending her peer Fierna in a manner that suggest they were best friends.

4. Enecura, the Queen of Dis (PF)

The concept of Enecura bit me while learning more about the Archdevils in Pathfinder. This moral woman stole immorality from one of the most powerful gods in Pathfinder, got sent to hell, managed to thrive in this setting, and either fell in love or manipulated another demi-deity to fall in love with her. Not only does this woman have ovaries of steel, she and Dispater are a Hades and Persephone romance in disguise without any problematic tropes.

3. Dispater, Lord of Dis (PF)

I liked Dispater when I first read about him in D&D, but became less impressed with 5e lore of making him paranoid and yet easily manipulated. It wasn't so much the sexuality it suggested for Dispater as is making a feared Archdevil a little weak - though most Archdevils in D&D have more obvious flaws. When reading about PF, I liked this depiction of Dispater even more. I could see the bones of D&D's Dispater in the character, built into a logical way with unique details. A fast friend of Asmodeus, loyal and focused on law and order, he willingly fell with his wife to follow his leader. And during that fall, something happened to his wife. And no one knows what. Regardless, it brought out genuine puppy dog eyes from a design that is particularly kinky. His story with his son, the trouble second marriage, and the third marriage is also quite intresting. He might not have the 40 years of backstory as his counterpart, but what he has is amazing.

2. Mephistopheles, Lord of Cania (D&D and PF)

Mephistopheles is the one that got me really interested in DnD planar lore, leading me to Planescape Torment. When I was younger, my first DnD interest began with BG1 and it grew from there with BG2 and then Neverwinter Nights. Mephistopheles was an NPC Villain that caught my attention quicker than the game's intended villain and got me to reading more about him and his comrades. A Starcream with delusions of grandeur that he could almost back up, Mephistopheles was my favorite for a long time with a DnD campaign that brought his attention to me again. It was also around the time I was playing Pathfinder CRPGs, but I didn't get poking into that until he showed up, again, in WotR. Of course, Pathfinder Mephistopheles is very different from DnD Mephistopheles. The incarnation of Hell itself with a deeply loyalty to anyone that advances Hell cause, Mephistopheles beloved by Asmodeus, and Mephistopheles is very much his right hand person. He also has a gorgeous design that does take nods from his 3e depiction.

And oddly, a blend of both depictions with a unique twist of UST make Mephistopheles even more fun.

Asmodeus, Lord of Nessus, God of Indulgence (D&D)

Although I find myself favoring the Pathfinder takes of the Archdevils, this doesn't hold true to Asmodeus. Pathfinder Asmodeus is great, but the only advantage he might have over his D&D counterpart was always being a god, and yet he lacks the same prestige as D&D Asmodeus for that role. D&D Asmodeus has been apart of the brand since it's inception as the ruler of Hell through all the five editions, with the 2nd edition only using bare descriptions to indicate who he was when you couldn't use devils or demons in D&D. He has several origin stories inspired from Christianity and Zoroastrianism and he's gone through several crises, always rising on the top. I think that's why I love him a bit more than his counterpart. Asmodeus has scraped and crawled from being a devil to becoming a greater Deity if only due to 4e deciding it was about fucking time he become one. He's earned this status, you've seen how he's earned it, and while how they cement his godhood in Forgotten Realms is super dumb, he should be a God - he who is more crafty and chaotic than anyone realizes.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!

I'm so glad i found your blog, your deep dives are making my brain tingle in the best of ways! It's so difficult to really find all the info your curious about with the many different editions and histories of everything so you are an absolute lifesaver for understanding all these intruiging lore aspects.

I've been very curious about Asmodeus for a while now but am kinda struggling finding out more about him, I know he's very strong and apparently a large snake?? But I was wondering if you at some point feel the motivation to if you could tell me some about him, he seems so interesting to me and I just wanna know more about who and what he is.

Again, you are so awesome and I vow to devour all your writing!

Asmodeus: An Origin

Thank you so much for the kind words - and for your patience as I worked on this one. If there's any question you had about him that feels like it's not wholly answered here, feel free to let me know! There's still a lot that I was not able to include.

As ever, these writeups will align with current 5e lore, and draw from 3.5e for additional supporting information. On rarer occasions – and always noted – I will reference 1e and 2e, but with the caveats that there is much more in those editions that is tonally dissonant with the modern conception of the Forgotten Realms, and thus generally less applicable.

You would be hard-pressed to find a more succinct introduction to Asmodeus himself than in the following passage, from 3e’s Book of Vile Darkness:

Asmodeus the Archfiend, the overlord of all the dukes of hell, commands all devilkind and reigns as the undisputed master of the Nine Hells. Even the deities that call that plane home pay Asmodeus a great deal of respect.¹

As to his current position, 5e’s Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide features Asmodeus among the list of gods, naming him the “god of indulgence”, and crediting to him the domains of knowledge and trickery. His symbol is “three inverted triangles arranged in a long triangle”, as seen in the image below.²

While his active circle of worshippers remains small, he is one of the gods habitually turned to by those in need, particularly those who have done something to earn them the displeasure of another god:

After transgressing against a god in some way, a person prays to Asmodeus for something to provide respite during the long wait. Asmodeus is known to grant people what they wish, and thus people pray for all the delights and distractions they desire most from life. Those who transgress in great ways often ask Asmodeus to hide their sins from the gods, and priests say that he will do so, but with a price after death.³

Asmodeus is particularly appealing to those who fear what awaits them after death, or have arrived to find the reality does not match their hopes. For these souls, even the hazards of Baator might be preferable to long centuries of solitary wandering on the Fugue Plane.

All souls wait on the Fugue Plane for a deity's pleasure, which determines where a soul will spend the rest of eternity. Those who lived their lives most in keeping with a deity's outlook are taken first. Others, who have transgressed in the eyes of their favored god or have not followed any particular ethos, might wait centuries before Kelemvor judges where they go. People who fear such a fate can pray to Asmodeus, his priests say, and in return a devil will grant a waiting soul some comfort.³

The worship of Asmodeus attracts staunch individualists, who desire a future unaligned with the domain of any of the other gods, and are willing to choose self-determination in any form that might approach them.

The faithful of Asmodeus acknowledge that devils offer their worshipers a path that's not for everyone — just as eternally basking in the light of Lathander or endlessly swinging a hammer in the mines of Moradin might not be for everyone. Those who serve Asmodeus in life hope to be summoned out of the moaning masses of the Fugue Plane after death. They yearn for the chance to master their own fates, with all of eternity to achieve their goals.³

Asmodeus achieved his current official status of godhood during the Spellplague, which lasted from 1385 to 1395 DR. After this, for reasons he has unsurprisingly chosen not to reveal, he performed a ritual to alter the metaphysical categorization of all existing tieflings, giving them features that highlighted this connection.

Due to this shift, tieflings are often perceived with wariness by those who believe that Asmodeus is able to exert control over these newly-determined “descendants” of his. While this is an unwarranted suspicion, as tieflings are no more bound to his will than any other individual of another race, the mistrust remains unfortunately pervasive.⁴

The true origins of Asmodeus, particularly from 3rd Edition on, are kept rather ambiguous, seemingly quite by design. This is both for Watsonian reasons – that a supreme being of evil such as Asmodeus would not carelessly leave information about his origins (and, potentially, weaknesses) floating around – as well as Doylist: it is a more elegant solution than eternal retcons, and leaves it up to the individual scholar or DM which explanation they ascribe the most veracity to.⁵

On the charge of Asmodeus’s true form being a giant serpent, we have Chris Pramas to thank for that bit of lore, stated in 2e’s 1999 Guide to Hell, but rarely mentioned - and not in any definitive manner - from 3e onward.⁶ 3e’s Manual of the Planes, published in 2001, does reference this account, but as a whispered and shadowy theory about the Archdevil Supreme, rather than objective truth.

Brutally repressed rumors suggest that there is more to Asmodeus than he admits. The story goes that the true form of Asmodeus actually resides in the deepest rift of Nessus called the Serpent’s Coil. The shape seen by all the other devils of the Nine Hells in the fortress of Malsheem is actually a highly advanced use of the project image spell or an avatar of some sort.

...

From where fell Asmodeus? Was he once a greater deity cast down from Elysium or Celestia, or is he older yet, as the rumor hints? Perhaps he represents some fundamental entity whose mere existence pulls the multiverse into its current configuration. Nobody who tells the story of Asmodeus’s “true” form lives more than 24 hours after repeating it aloud. But dusty scrolls in hard-to-reach libraries (such as Demogorgon’s citadel in the Abyss) yet record this knowledge. Unless it is pure fancy, of course.⁷

One can see from the framing of the above excerpt that there is no attempt made at certainty. Perhaps it is mere conjecture, or perhaps a secret, hidden truth that few may know. It is impossible to say for certain.

Another story of Asmodeus’s possible origin is found in 3e’s Fiendish Codex II. This text, again, does not frame the information given as universal truth, but rather takes pains to emphasize its ambiguity.