#1750s france

Text

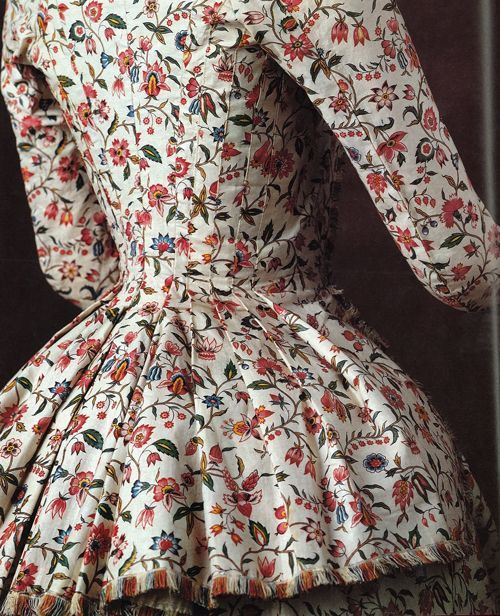

Beige Floral Silk Robe à la Française, 1750-1775, French.

Met Museum.

#met museum#silk#extant garments#womenswear#dress#france#french#18th century#beige#floral#robe à la française#1750#1750s france#1750s#1760s#1770s#1760s france#1770s france#ancien régime#1750s dress#1760s dress#1770s dress#1750s extant garment#1760s extant garment#1770s extant garment

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robe à la française

1750s; Altered 1780s & Late 19th Century

France & England

The ensemble was probably made as a sack and petticoat in the 1750s. In the 1780s, the sack was updated in style. A waist seam was probably added, the skirts reconfigured, and sleeve ruffles removed. The half-stomachers were added at this time and the bodice fronts relined. The back lacing was reconfigured and more eyelets worked.

The ensemble was altered for fancy dress in the late 19th century. Hooks and eyes were added to the bodice stomacher fronts and machine-lace ruffles to the sleeves. The petticoat may have been unpicked at this point.

The petticoat was gathered onto a cotton band after acquisition for Museum display. (V&A)

Victoria & Albert Museum (Accession Number: CIRC.157-1920)

#robe a la francaise#fancy dress#fashion history#historical fashion#1750s#1780s#19th century#georgian#victorian#france#england#v and a#v and a museum#popular

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

• Stays.

Date: ca. 1750

Place of origin: France

Medium: Silk damask, printed linen lining, whalebone, silk tape, and kid leather.

#fashion history#history of fashion#fashion#18th century fashion#historical#historical fashion#stays#france#french#ca. 1750

586 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robe à la française, c. 1740-55; France

#robe a la francaise#mdpcostume#costume#ensemble#France#18th c. France#18th c. costume#1740s#1750s#mid 18th century

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Repos, by Jean-François Gilles Colson (1759).

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seal with an ivory miniature, France, c. 1750

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

#lyney and lynette#genshin lyney#genshin lynette#genshin impact#magic sibs a la 1750s France#I know I am not completely accurate and if the fashion history police come for me#shh#it’s not that serious#I thought it would be fun to give them some 18th c courtly fashion designs since Fontaine is arguably France-adjacent#AND because of their little heart and star#artificial stick on beauty marks like this were super popular in court fashion in 18th c France! they were known as mouches#the style of pleated trim on both of their outfits is also very reminiscent of a lot of historical gown trims#this was a fun little exercise and then I decided to color it?#honestly pretty pleased with the end result#teleport warning draws

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis XV fashions

Upper left: 1754 Madame Henriette playing the Gamba by Jean-Marc Nattier (Versailles). From Wikimedia 1363X1960 @72 649kj. Posthumous portrait.

Upper right: 1760s (early, possibly) Count Giacomo Durazzo and Ernestine Aloisia Ungnad von Weissenwolff by Martin van Meytens the Younger (Metropolitan Museum of Art). From their Web site 1558X1874 @150 1.2Mj.

Lower left: 1766 Lady by Jean François Colson (location ?). From tumblr.com/blog/view/jeannepompadour/99117938025 775X944 @72 163kj.

Lower right: 1772 Russian Lady by Grigory Serdyukov (location ?). From costumecocktail.com/2015/12/08/lady-in-white-cap-1772/ 863X1134 @96 336kj.

#Rococo fashion#Louis XV fashion#1750s fashion#Madame Henriette#Henriette de France#Jean-Marc Nattier#Nattier#straight hair#hair flowers#scoop neckline#lace bertha#ruffled sleeves#three-quarter length full sleeves#bow#Sévigné bodice ornament#stomacher#V waistline#over-skirt#1760s fashion#van Meytens the Younger#lace modesty piece#bows#collar#three-quarter length close sleeves#under-sleeves#lace cuffs#wrap#1766 fashion#Jean François Colson#curled hair

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beige Silk Shoes, 1750-1770, French.

Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris.

#beige#silk#shoes#1750s shoes#1750s#1760s#1760s shoes#1750s france#1760s france#reign: louis xv#France#French#mad paris#musée des arts décoratifs paris#1750s extant garment#1760s extant garment

38 notes

·

View notes

Video

185 - Alfa Roméo 1750 GTAm de 1968 by Laurent Quérité

Via Flickr:

Tour Auto 2023 Pilote : Timm MEINRENKEN Copilote : Fynn SCHRODER Col de la Madeleine D19 Vaucluse France IMG_3530

#Canon EF 300mm f/4L IS USM#CanonFrance#Canonphotography#Canon EOS 5D Mark II#Voiture#Automobile#Cars#carlovers#carphotography#historic car#Classic Car#Peter Auto#Tour auto 2023#Col de la Madeleine#Vaucluse#France#Laurent Quérité#Alfa Roméo#Alfa Roméo 1750#flickr

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dress (Left) & Robe Volante (Right)

c.1750 & 1700-1735

Italy & France

Late in the reign of Louis XIV, loose-flowing gowns with pleats gathered at the back neckband were worn as undress wear by daring ladies who liked the ease and comfort of this garment. The famous actress Madame Dancourt popularized these gowns by wearing one in Terence’s Andria, after which such gowns were often called andriennes. As the style developed the gathers were formalized by being drawn into one or more flat pleats, and a dome-shaped hoop or pannier was worn to extend the material around the wearer. When a lady moved, air was trapped under the hoops and she appeared to be floating; thus the name robe volante. This type of dress is often erroneously called a "Watteau sack," despite the fact that Antoine Watteau had little to do with the creation or dissemination of the fashion. According to the Mercure de France, by 1729 robes volantes were "universellement en règne, on ne voit presque plus d’autres habits" (universally in vogue, one hardly ever sees any other kind of dress).

The MET (Accession Number: 26.56.47a–g) (Accession Number: C.I.50.40.9)

#dress#fashion history#historical fashion#1700s#1750s#robe volante#18th century#green#silk#floral#flower print#france#italy#ancien regime#the met

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

Woman's Dress and Petticoat (Robe à la française)

France, textile circa 1750, constructed circa 1760

Linen plain weave with wool embroidery

Dress: center back length: 60 in. (152.4 cm)

Petticoat: center front length: 34 1/2 in. (86.96 cm)

LACMA

#Robe à la française#robe a la francaise#18th century#1750s#1760s#dress#gown#fashion#clothing#vintage#France#historical

0 notes

Photo

#broken eggs#Abbé Louis Gougenot#Abbé de Chézal-Benoît#rome#paris#metropolitan museum of art#france#europe#oil painting#oil on canvas#oil#painting#art#eggs#1756#1700s#1750s

1 note

·

View note

Text

Box, made in France, c.1750

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

How did cotton win over linen anyway?

In short, colonialism, slavery and the industrial revolution. In length:

Cotton doesn't grow in Europe so before the Modern Era, cotton was rare and used in small quantities for specific purposes (lining doublets for example). The thing with cotton is, that's it can be printed with dye very easily. The colors are bright and they don't fade easily. With wool and silk fabrics, which were the more traditional fabrics for outer wear in Europe (silk for upper classes of course), patterns usually needed to be embroidered or woven to the cloth to last, which was very expensive. Wool is extremely hard to print to anything detailed that would stay even with modern technology. Silk can be printed easily today with screen printing, but before late 18th century the technique wasn't known in western world (it was invented in China a millenium ago) and the available methods didn't yeld good results.

So when in the late 17th century European trading companies were establishing trading posts in India, a huge producer of cotton fabrics, suddenly cotton was much more available in Europe. Indian calico cotton, which was sturdy and cheap and was painted or printed with colorful and intricate floral patters, chintz, especially caught on and became very fashionable. The popular Orientalism of the time also contributed to it becoming fasionable, chintz was seen as "exotic" and therefore appealing.

Here's a typical calico jacket from late 18th century. The ones in European markets often had white background, but red background was also fairly common.

The problem with this was that this was not great for the business of the European fabric producers, especially silk producers in France and wool producers in England, who before were dominating the European textile market and didn't like that they now had competition. So European countries imposed trade restrictions for Indian cotton, England banning cotton almost fully in 1721. Since the introduction of Indian cottons, there had been attempts to recreate it in Europe with little success. They didn't have nearly advanced enough fabric printing and cotton weaving techniques to match the level of Indian calico. Cotton trade with India didn't end though. The European trading companies would export Indian cottons to West African market to fund the trans-Atlantic slave trade that was growing quickly. European cottons were also imported to Africa. At first they didn't have great demand as they were so lacking compared to Indian cotton, but by the mid 1700s quality of English cotton had improved enough to be competitive.

Inventions in industrial textile machinery, specifically spinning jenny in 1780s and water frame in 1770s, would finally give England the advantages they needed to conquer the cotton market. These inventions allowed producing very cheap but good quality cotton and fabric printing, which would finally produce decent imitations of Indian calico in large quantities. Around the same time in mid 1700s, The East Indian Company had taken over Bengal and soon following most of the Indian sub-continent, effectively putting it under British colonial rule (but with a corporate rule dystopian twist). So when industrialized English cotton took over the market, The East India Company would suppress Indian textile industry to utilize Indian raw cotton production for English textile industry and then import cotton textiles back to India. In 1750s India's exports were mainly fine cotton and silk, but during the next century Indian export would become mostly raw materials. They effectively de-industrialized India to industrialize England further.

India, most notably Bengal area, had been an international textile hub for millennia, producing the finest cottons and silks with extremely advance techniques. Loosing cotton textile industry devastated Indian local economies and eradicated many traditional textile craft skills. Perhaps the most glaring example is that of Dhaka muslin. Named after the city in Bengal it was produced in, it was extremely fine and thin cotton requiring very complicated and time consuming spinning process, painstakingly meticulous hand-weaving process and a very specific breed of cotton. It was basically transparent as seen depicted in this Mughal painting from early 17th century.

It was used by e.g. the ancient Greeks, Mughal emperors and, while the methods and it's production was systematically being destroyed by the British to squash competition, it became super fashionable in Europe. It was extremely expensive, even more so than silk, which is probably why it became so popular among the rich. In 1780s Marie Antoinette famously and scandalously wore chemise a la reine made from multiple layers of Dhaka muslin. In 1790s, when the empire silhouette took over, it became even more popular, continuing to the very early 1800s, till Dhaka muslin production fully collapsed and the knowledge and skill to produce it were lost. But earlier this year, after years lasting research to revive the Dhaka muslin funded by Bangladeshi government, they actually recreated it after finding the right right cotton plant and gathering spinners and weavers skilled in traditional craft to train with it. (It's super cool and I'm making a whole post about it (it has been in the making for months now) so I won't extend this post more.)

Marie Antoinette in the famous painting with wearing Dhaka muslin in 1783, and empress Joséphine Bonaparte in 1801 also wearing Dhaka muslin.

While the trans-Atlantic slave trade was partly funded by the cotton trade and industrial English cotton, the slave trade would also be used to bolster the emerging English cotton industry by forcing African slaves to work in the cotton plantations of Southern US. This produced even more (and cheaper (again slave labor)) raw material, which allowed the quick upward scaling of the cotton factories in Britain. Cotton was what really kicked off the industrial revolution, and it started in England, because they colonized their biggest competitor India and therefore were able to take hold of the whole cotton market and fund rapid industrialization.

Eventually the availability of cotton, increase in ready-made clothing and the luxurious reputation of cotton lead to cotton underwear replacing linen underwear (and eventually sheets) (the far superior option for the reasons I talked about here) in early Victorian Era. Before Victorian era underwear was very practical, just simple rectangles and triangles sewn together. It was just meant to protect the outer clothing and the skin, and it wasn't seen anyway, so why put the relatively scarce resources into making it pretty? Well, by the mid 1800s England was basically fully industrialized and resource were not scarce anymore. Middle class was increasing during the Victorian Era and, after the hard won battles of the workers movement, the conditions of workers was improving a bit. That combined with decrease in prices of clothing, most people were able to partake in fashion. This of course led to the upper classes finding new ways to separate themselves from lower classes. One of these things was getting fancy underwear. Fine cotton kept the fancy reputation it had gained first as an exotic new commodity in late 17th century and then in Regency Era as the extremely expensive fabric of queens and empresses. Cotton also is softer than linen, and therefore was seen as more luxurious against skin. So cotton shifts became the fancier shifts. At the same time cotton drawers were becoming common additional underwear for women.

It wouldn't stay as an upper class thing, because as said cotton was cheap and available. Ready-made clothing also helped spread the fancier cotton underwear, as then you could buy fairly cheaply pretty underwear and you didn't even have to put extra effort into it's decoration. At the same time cotton industry was massive and powerful and very much eager to promote cotton underwear as it would make a very steady and long lasting demand for cotton.

In conclusion, cotton has a dark and bloody history and it didn't become the standard underwear fabric for very good reasons.

Here's couple of excellent sources regarding the history of cotton industry:

The European Response to Indian Cottons, Prasannan Parthasarathi

INDIAN COTTON MILLS AND THE BRITISH ECONOMIC POLICY, 1854-1894, Rajib Lochan Sahoo

#i have fixed the wording in the beginning so it doesn't sound like i'm saying cotton in general dyed better than wool or silk#answers#fashion history#historical fashion#history#textile history#dress history#historical clothing#indian history#colonial history#indian textiles#cotton#slavery

2K notes

·

View notes