#16th c. France

Text

Collection of drawings accompanied by texts, known as Recueil Robertet, 1490-1520 France;

The Duchess of Bar

Women from Lombardy and Venice

Women from Naples and Florence

Women from Germany and France

Green and Yellow; White and Blue

#late 15th century#early 16th century#renaissance#manuscript#illuminated manuscript#illustrated manuscript#16th century#15th century#mdp16th c.#mdp15th c.#France#15th c. France#16th c. France#italy#costume illustration#illustration#15th c. italy#16th c. Italy#costume book#German Style#Germany#15th c. Germany#16th c. Germany#horseback#riding

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pirate-themed PNGs, part 2.

(1. Bag of jewels, 2. Shipwreck treasure, 3. Bronze siren from 16th c. France, 4. Green glass bottle, 5. Skull & goblet (?), 6. Bloody hand (?), 7. Goblet from 1632, 8. Sea urchin, 9. Ship pendant)

#request#png#pngs#transparent#sticker#stickers#collage#imageboard#artboard#moodboard#polyvore#pirate

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

job on the dungheap, tormented by four demons

illustration from a book of hours, france (rouen), late 15th or early 16th c.

source: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Buchanan e. 3, fol. 55r

#15th century#16th century#book of hours#job#job on the dungheap#book of job#demons#illuminated manuscript

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

The oldest known cello in the world is "The King" made by Italian instrument maker Andrea Amati (c. 1505 - 26 December 1577) around mid-16th century AD in Cremona, Italy.

It was part of a set of 38 stringed instruments made for the court of King Charles IV of France.

#King Charles IV of France#Andrea Amati#The King#cello#violin#stringed instruments#luthier#16th century#1500s

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's #YearOfHours is Lewis E 112, an early 16th c. Book of Hours written in France. It has a liturgical calendar for Lyon. It is generously illuminated, with twelve full-page miniatures, eighteen smaller miniatures, and illuminated initials.

🔗:

#medieval#renaissance#book of hours#year of hours#france#lyon#illuminated#illustrated#illuminated manuscript#book history#art history#rare books

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

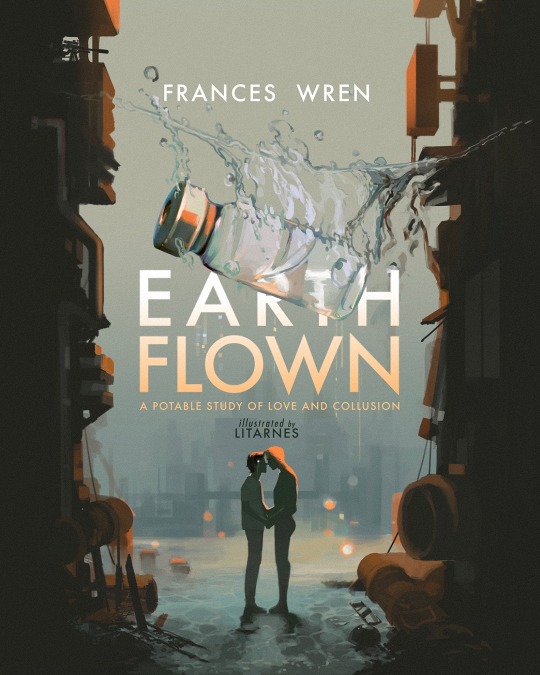

✨Earthflown by Frances Wren

(releases on April 16th)

When Ethan saves the life of a firestarter, it's nothing unusual. He's the only healer on call at the hospital – and that gunshot wound isn't going to regenerate itself. But his patient turns out to be Corinna Arden, heiress to a pharmaceutical empire controlling Britain's water supply. Her twin, Javier, is a man who (a) starts sending Ethan flowers at work, (b) seems terrified of a secret, and (c) has the cheekbones and earnestness to make up for both.

Ethan indulges in (what he thinks will be) a brief, harmless romance – but is swept up in a deadly collusion over Project Earthflown: the largest reconstruction tender since London clawed its way out of the rising sea.

Determined to follow the money, Ollie is a journalist who finds a corpse at the end of a too-convenient tip. The fate of water - and who profits - might depend on the perennial question: Has Ethan lost his mind, or is he just an idiot?

--

Earthflown is a love story that tries – and fails – to leave the water crisis behind. Set in near-future, post-flood London, the novel takes a grounded approach to fantasy archetypes, where futuristic medicine meets a bit of magic. The Indigo exclusive edition with exclusive bonus scenes is available for preorder now !

You can already add the Book to your "want to read" shelf on goodreads or storygraph as well as browsing through it's very own website at earthflown.com

#Earthflown#Frances Wren#Litarnes#queer scifi#upcoming queer books#found family#hurt/comfort#climate fiction#asexual representation#own voices novel

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the most ridiculously uselessly ornamented weapon/armor you have seen?

I'm actually going to give a bit of an out-of-universe answer for this one, because some historical armors are too crazy not to share! A few of my favourites:

In European ts important to distinguish "combat armor", which tended to be simple and to the point with "parade armor", which is not. Tournament armor, specialized for Hastilude events like jousting, was somewhere in the middle, with special reinforced areas. Here's a good example of how ridiculous it gets, with the 16th C. armor of King Henri II of France:

Spree killer King Erik XIV of Sweden shows that its not just Henri

Personally, I am fond of the masterwork "Greenwich Armor". In addition to its insane level of detail, its also blue. In a process called "Bluing" the steel is precisely oxidized to "dye" the armor a certain colour! So next time someone calls out your OC for heaving bright blue or red armor, these actually have some striking historical precedent!

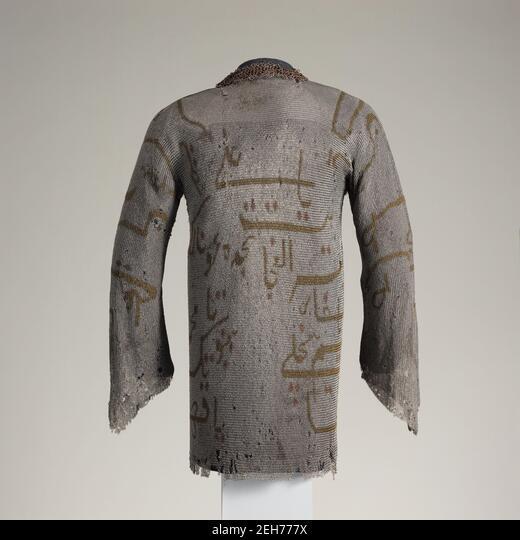

I think the all-time winners though, are Iranian chain mail shirts. They often had intricate religious lettering on the rings, seen here using different metals...

While this one EVERY LINK is inscribed with a name of Allah or a short prayer!

And of course, no tour of insanely elaborate armor would be complete without checking in on our good friend and historical maniac Henry VIII of England, with his deranged "knight"mare fueled "Horned Helmet".

The historical armors of the world are pretty crazy, and the above are just a small selection of European and Near-Eastern varieties, not even touching on some of the equally insane armors from elsewhere, from the Japanese Kabuto (Ridiculously detailed and odd samurai helmets) to Chinese Paper Armor (Looks like a cosplay made out of post-it notes and office supplies) and the gorram amazing Kiribati Puffer Fish Armor, which looks like something out of a Flash Gordon comic. It is amazing and I wish more people would use it in their designs!

So, a little bit of a cop-out for not providing an Alvez specific answer, but unusual armor is a fascinating topic that far outshines anything I could come up with.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

An exhaustive timeline of the Patron-Minette and their appearances in Les Misérables

Have you ever wanted to know the movements and actions of every single Patron-Minette character (including all affiliates?), throughout the narrative of Les Misérables and beyond? Well, this is the post for you!

This information is either collected from scenes that we as readers witness directly in Les Misérables, or pieced together (as best as I have been able to piece things together) from indirect snippets that Hugo gives us about these characters in passing. I haven’t listed the chapters where this information is located, but if you are curious feel free to message me and I can provide information!

P.S: There are many other wonderful Les Misérables timelines out there, which I urge you to check out! Please note that this timeline only contains information relating to the Patron-Minette, and that whilst Thénardier is featured multiple times in this timeline, he is not actually officially associated with the gang as an affiliate, but is rather a standalone crook that just happens to engage with the group in multiple scenes.

c.1793-1797;

Gueulemer likely born at some point in this period. In 1832 he is described as having ‘a mass of crow’s feet, though not yet forty years old’, and in 1815 he is working as a porter— so must have been an adult, or at least close to adulthood, in that year. Taken together, this information suggests that Gueulemer was probably born around within these years.

1811;

At La Force, Brujon’s father, who is also called Brujon, is locked up. He carves ‘BRUJON, 1811’ into the courtyard wall in the “Lion’s Den” at La Force.

[SPECULATIVE] Brujon is born. I suggest this only because of the line, ‘the Brujon or 1811 was the father of the Brujon of 1832’, which I feel implies Brujon must have been born around this time. Brujon is also described in 1832 as a ‘lad’, so must have been fairly young. If he was born in 1811, he would be 21 in 1832, which seems to align with the ‘lad’ description too.

c.1813-1814;

Montparnasse is born.

1815;

Gueulemer works as a porter in Avignon.

August 2nd

Gueulemer likely involved in the assassination of Marshal Brune.

Sometime before November, 1823;

Boulatruelle had been arrested and imprisoned for a crime we are not privy to, and likely was locked up on the Orion ship (since it is implied he recognised Valjean later in the novel).

He is released from prison and tries to find work in Montfermeil, but is unsuccessful. The only job he can get is for the administration, who hire him as a reduced-rate road mender. He is treated as an outcast by the people of Montfermeil.

1823;

‘Several days’ after November 16th

In Montfermeil, Boulatruelle continues his work as a road mender, but leaves his post early constantly to creep about in the forest. Thénardier, who still owned the inn at this time, gets Boulatruelle drunk in order to get him to reveal what he does in the forest. Boulatruelle reveals that he is trying to look for and dig up some treasure that he had seen an ex-convict whom he recognised (aka Valjean) hide in the woods. He is unsuccessful in finding this treasure.

Sometime before 1830;

Babet works a variety of jobs, including as a clown at Bobinos, and showing ‘freaks’ at fairs. During this time, he owns a booth with an advertisement that reads ‘Babet, dental artist, member of the academies, conducts physical experiments on metals and metalloids, extracts teeth, tackles stumps abandoned by his colleagues. Price: one tooth, one franc, fifty centimes; two teeth, two francs; three teeth, two francs, fifty. Take advantage of this opportunity.’

Babet gets married. He has children (it is not disclosed how many, but from the plural usage of ‘children’ rather than ‘a child’, we can assume he has more than one). The family travel together in his ‘booth-on-wheels’.

Babet’s wife and children disappear one day: ‘he had lost them the way you lose your hankie’. Soon after he decides to go and “tackle” Paris.

1830;

Patron-Minette begin ‘ruling’ the dregs of Paris.

Sometime between 1830-1832;

When out together one time, Courfeyrac points out Panchaud to Marius, seemingly aware of his reputation as a ‘dangerous night rambler’.

Montparnasse likely begins murdering people in this period as, by 1832, he already has ‘several corpses to his name’.

[SPECULATIVE] In this period Brujon had ‘done over’ a police station, out of sheer bravado. This information is revealed in a passing comment in the rue Plumet scene, which would mean that Brujon’s feat would have occured before June 1832, and, with Brujon being a fairly young ‘lad’, I am assuming that he would have only managed this feat in the last couple of years, after the Patron-Minette had begun to ‘rule’ the dregs of Paris.

1832;

We know that in 1832 the Patron-Minette has four heads, Babet, Gueulemer, Claquesous, and Montparnasse. We also know they have a vast network of associates - we learn 18 of their names; Panchaud*, Brujon*, Boulatruelle*, Laveuve, Homère Hugu, Mardisoir, Dépêche, Fauntleroy, Glorieux*, Barrecarrosse*, Lesplanade-du-Sud, Poussagrive, Carmagnolet, Kruideniers*, Mangedentelle, Les-pieds-en-l’air, and Demi-Liard*. [the affiliates who have an asterisk next to their name appear in the novel. The others sadly do not appear in any scenes].

February 2nd, evening

Brujon and Demi-Liard watch a melodrama at the Gaîté Theatre.

February 3rd, in the day

Thénardier converses with Panchaud near the rue de la Barrière-des-Gobelins, likely informing him of his plans for the Gorbeau ambush that evening. Marius sees them (and recognises Panchaud).

Later in the day, Brujon and Demi-Liard meet on the rue du Petit-Banquier, and Brujon convinces Demi-Liard to partake in the Gorbeau ambush that evening.

February 3rd, 6pm; the Gorbeau ambush

Babet, Claquesous and Gueulemer are present at the ambush.

Panchaud, Demi-Liard, Brujon, and Boulatruelle are present at the ambush.

Montparnasse is not present at the ambush. He shows up but stops on the boulevard outside the building to talk to Éponine, before they go off and ‘play Némorin’ together instead of help out on the job.

When Javert interrupts the ambush, all of the Patron-Minette characters present are arrested and taken to La Force. Azelma, Mme Thénardier, and Thénardier are also arrested. Thénardier is also sent to La Force along with the Patron-Minette, Mme Thénardier is sent to Saint Lazare, Azelma is sent to Les Madelonettes.

Night of February 3rd / morning of February 4th

Claquesous is ‘lost’ and manages to escape from the police’s clutches whilst being transported to La Force. He is free.

Éponine is found and ‘nabbed’, being sent to Les Madelonettes alongside her sister.

The Patron-Minette characters are all put into solitary at La Force.

Mid-February

Brujon released from solitary confinement and into Charlemagne yard, with the police hoping that he might reveal something whilst chatting. He spends his days in the yard staring at the canteen’s price list and complaining of being ill, shivering and trying to get sent to the infirmary. Secretly, he is plotting an escape.

The other arrested Patron-Minette characters remain in solitary.

‘Towards the end of February’

All captured Patron-Minette members remain in prison.

Brujon sends out notes to three previously unmentioned Patron-Minette associates, Kruideniers, Glorieux, and Barrecarosse [confirmed by the line ‘these men were somehow affiliated with the Patron-Minette gang], who patrol the areas of the Panthéon, the Val-de-Grâce’ and the barrière de la Grenelle respectively. These men are arrested by the police, who suspect that Brujon is planning a scheme from prison.

Brujon writes his note to Babet, informing him of rue Plumet. He is caught and sent to solitary for a month, but the note still gets to Babet.

Babet, using his mistress (locked up at La Salpêtrière) is able to transfer this note to Magnon, who delivers the note to Éponine as soon as she is released from Les Madelonettes.

Azelma and Éponine released from Les Madelonettes.

‘A few days later’; c. end of February / early March 1832

Éponine delivers a biscuit, meaning that there is nothing worth doing at rue Plumet, to Magnon, who transfers it to Babet’s mistress, who transfers it back to Babet.

‘Less than a week after that’; c. early March 1832

Babet and Brujon bump into each other, as one heads into the ‘preliminary’ and the other returns from it. Babet informs Brujon that there is nothing worthwhile at rue Plumet and the scheme is aborted.

March

Brujon is still spending his time in the correctional chamber, after being caught writing his note, and distributing notes outside of prison. Whilst there, he plans his escape, and makes a rope.

After being released from the correctional chamber, he is transported to the New Building. Here he finds Gueulemer and a nail.

One evening in early April

Beyond the Salpêtrière - in the Austerlitz area, Montparnasse follows Valjean with a rose in his mouth. He tries to attack the old man but is overpowered, and instead treated to a long lecture. Valjean hands Montparnasse his purse. Gavroche, who witnessed the whole thing whilst hiding in some shrubbery, then steals it from Montparnasse’s pocket and leaves it for Mabeuf.

The following day

Babet escapes prison in the morning, as he was being transported from La Force to La Conciergerie.

Gavroche bumps into Montparnasse at the corner of rue des Ballets, near La Force. Montparnasse tells Gavroche that he is off to find Babet and informs him that Babet has escaped (it is not clear how Montparnasse found out this information, or if he had seen Babet earlier that day, but regardless he still is aware of what happened). Montparnasse puts two quill pieces wrapped in cotton up his nose, disguising himself and making his voice sound different. He also carries his cane that contains a concealed knife within.

In the early hours of the next morning, ‘towards one o’clock’

Babet and Montparnasse meet up and prowl around La Force, waiting on Gueulemer and Brujon to escape. It is a windy, rainy night.

Brujon and Gueulemer get up in the middle of the night and start using the nail that Brujon had found before to break the chimney which their beds stood against. They scale the chimney, force the iron grating apart, and end up on the roof. They secure the rope that Brujon made to the iron railing and descent down the eighty foot drop down to the bathhouse, and exit onto the street, and regroup with Babet and Montparnasse. Brujon pulls the rope down, some of it tears and is left on the roof. This escape only takes 45 minutes.

Thénardier sees Brujon and Gueulemer escape on the roof from his cell.

One hour later, at around two o’clock

Thénardier drugs the conscript watching his cell with stupefying wine and steals his bayonet. He makes his way up to the roof (no further detail about how he made it onto the roof is given)

The remnants of Brujon’s rope left on the rood are far too short for Thénardier to use to escape. He is stranded there until 4am.

Two hours later, at four o’clock

The police are alerted of Thénardier’s escape. Babet, Montparnasse, Gueulemer, and Brujon congregate beneath the roof that Thénardier has been stuck above for the last couple of hours, arguing about whether they should leave him, or wait a little longer. They spot him once he throws down the remainder of the rope left on the roof at their feet. Montparnasse tells Brujon to tie the rope together again and throw it up, that way Thénardier can climb down. However, Thénardier is too cold to move. They determine they need a ‘nipper’. Montparnasse runs towards the Bastille.

‘Seven or eight minutes later’

Montparnasse returns with Gavroche, who helps Thénardier escape. Gavroche recognises him as his father, but Thénardier does not recognise Gavroche as his son, not even when Babet pulls him aside and informs him that the boy who saved him was his son.

June 3rd, in the morning

Brujon sees some sparrows fighting.

June 3rd, in the evening

Brujon encounters a woman arguing.

June 3rd, 1 hour after nightfall; rue Plumet attack

Babet, Gueulemer, Claquesous, Brujon, Montparnasse, (and Thénardier) show up to rue Plumet, carrying an array of various horrible weapons. Gueulemer is specified to be carrying a pair of fanchons. They encounter Éponine, who had not seen her father in four months.

Montparnasse and Éponine exchange awkwardly flirtatious dialogue, and she does not address him as Monsieur. She grabs his hand and he warns her that she’ll cut herself on his knife.

After failing to convince them that rue Plumet is a biscuit, Éponine leans against the gate and threatens to scream, before making her powerful (and devastatingly tragic) speech.

Babet reasons that there is something the matter with Éponine, and remains keen on doing the job. Montparnasse threatens her with a knife. Brujon however, who is described as a bit of an ‘oracle’, reveals that he is against entering the house now. He is superstitious, and recollects the fighting birds and woman he saw earlier in the day as a sign that the job was bad.

The gang resolves to clear out. As they leave, Montparnasse declares that he would have slit Éponine’s throat, if they would have wanted him to. Babet responds with ‘not me, I don’t touch women’.

June 5th, at night, but before ten o’clock

Le Cabuc**, a mysterious stranger, is at the barricades and drinking. He decides to try and get into one of the large houses along rue Saint-Denis, banging at the door. When he is denied entry, he shoots the porter. He is executed by Enjolras, and his body tossed into rue Mondétour.

**Early June, a short while after the barricades fell

In the morgue, Le Cabuc’s body is searched and a police agent’s card is found on his person. Victor Hugo (practically) confirms that Le Cabuc was Claquesous.

A special report on this subject is written for the Prefect of Police. Hugo claims that in 1848 he held this exact report.

‘Some little time’ after June 7th

Boulatruelle is released from prison, as there is not enough evidence to charge him for the Gorbeau ambush, since he was so drunk. He goes back to the road between Gagny and Lagny, where he used to work as a road mender before. His alcoholism becomes worse.

Soon after; ‘one morning, shortly before daybreak’

Boulatruelle spots a man walking in Montfermeil’s forests. He tries to follow him, but keeps losing sight. He eventually stumbles upon the location of the treasure he had so long dreamed of finding. But, the hole had been dug up, and it was empty.

c.1833;

Panchaud and Demi-Liard are sentenced to ten years in the galleys for their crimes during the Gorbeau ambush.

1835;

Patron-Minette stop ‘ruling’ the dregs of Paris. It is not clear whether that means the group disbanded or if they had simply become too weak and slipped from their position of power.

1843;

Panchaud makes a famous prison escape at La Force [unclear if the escape is successful]. We are informed that this escape happened in broad daylight, and involved thirty prisoners.

As Panchaud makes his escape, he writes his name above the culvert at the entrance to the sewer.

c.1848;

Panchaud has become a ‘celebrity crook’, and is spoken of as a legend by prisoners in La Force. (Hugo writes in 1862 that ‘he had a real following towards the close of the last reign’, which I believe is making reference to the reign of Louis Philippe - as the Second Republic did not have a king, but rather Presidents... but, I could most certainly be wrong!)

#patron minette#patron-minette#patron minette affiliates#babet#gueulemer#claquesous#montparnasse#brujon#panchaud#demi-liard#boulatruelle#glorieux#barrecarosse#kruideniers#les miserables#les mis#meta#timeline

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

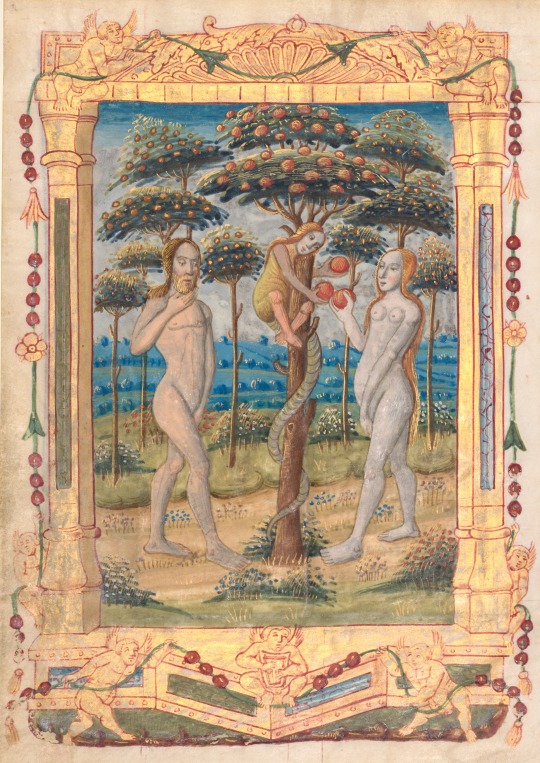

Leaf from a Book of Hours: Adam and Eve and the Fall of Man (Prefatory Miniature to the Office of the Virgin) (recto)

c. 1510

France, Rouen, 16th century

188 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hope this works : https://i.pinimg.com/564x/40/e6/eb/40e6eb52d24dee59e597ca00f46bcddd.jpg

Original ask:People keep saying this is Frances Brandon, but looking at the fashion and the features of the sitter, I feel it's Katherine of Aragon instead. What are your thoughts?

(we didnt have the photo originally, but now i can finally answer this).

-My first observation regarding this painting is that it cannot be Francis Brandon, because she was born in 1517. This is 1500s or 1510s fashion of Netherlands. No way she could be depicted in fashion which is from before she was even born!

On wikipedia it is labelled Portrait of Agniete van den Rijne, atributed to Joos van Cleve, located in Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede, in Netherlands. And as being painted in 1st half of 16th century.

On webpage of the museum, it is labelled as Unknown woman in c.1515. I suspect it could be bit earlier(split gown, large hanging chains)-my guess would be late 1500s, max early 1510s. But my chronology of netherlandish fashion was based upon court fashion. And neckline this low is consistent with some parts of Habsburg Netherlands, but not the court. So I could be bit off. But either way-1500s or 1510s imo. Not Francis Brandon. She wasnt even born when this was in fashion.

As for Catherine of Aragon.

Not that she couldnt wear netherlandish fashion(Sittow's portrait)-but a)when she did wear it, it was same fashion as in court.

b) what cut photos deliberately left out, is that this painting has its original frame...which includes coat of arms.

And experts believe this coat of arms to be original.

They havent been able to identify it nor of the man matching the woman. But clearly not Catherine's coat of arms.

Also the focus here is on grapes-its fruit, its leaves and vines.

It is symbol of fertility and prosperity, as well as having several more meanings in christianity, but as far as i know never asociated with Catherine of Aragon specifically. And there is literally nothing to suggest it is her.

I agree that there is resemblence, but there is issue. The artist was skilled. So why upon closer inspection the nose looks so differently than hers?

Catherine's nose tip seemed to be pointing more up and it was not as large. With some people-for example Margaret of Austria, size of nose changes as they age(due to health issues). However Catherine even in mid 1520s, still has narrow nose with tip basically same as in her youth.

Angle might play part a bit...but imo it is simply different nose.

The resemblence alone cannot drive identification. Not only do we not have single major clue pointing towards Catherine, we have major clue against her(coat of arms). Also Henry was likely painted by the artist when he met Francis I at Calais-with Anne Boleyn. The artist was asociated a lot with Francis, but never proven to travel to England or to take comissions from English royal court...aside that one meeting.

I am sorry, it is not Catherine of Aragon.

I am as upset as you guys that we don't have any surviving portrait of her from 1510s, and that many portraits we only know from not so great copies.

To find more lost originals, looking through art of artists which painted relatives of the person is indeed very good strategy. It pays off in many cases. Unfortuntely not in case of Joos van Cleve.

But it might be good idea to look up painters employed by Charles V and by Francis I in 1520-because Catherine met both that year.

Henry and Charles even had joined portraits made back then.

So there is indeed potential that some portrait of Catherine was created and it might have went with visitor. And it could have been another joined portrait because Charles didnt visit alone but with Germaine of Foix.

Problem is, the most likely thing for Catherine to wear in any portrait as Queen of England is gable hood- headwear unique to England. For her portraits to not be noticed, they would either have to be overpainted/altered, misidentified, misdated or even all three.

Another option is that upon meeting Charles that she wore spanish fashion. If she got painted in that, she wouldnt be that likely to be recognized.

Or maybe we need to broaden our idea of what Catherine wore.

So my dears, the hunt is still on.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marguerite de Valois by Francois Clouet, 1572

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lecture Notes MON 16th OCT

Masterlist

BUY ME A COFFEE

Doing Art History: Drawing/Works on paper.

Oeuvre: the artworld of that time. The body of work by a painter, composer, or author.

Drawing was and has always been the first step into becoming an artist, it is the most fundamental and important aspect of any artistic study or development. To know your fundamentals, the figure, perspective, and weight/shading. Historically this is the first step any artist took, before developing into their preferred medium.

Observe these drawings/sketches and paintings; consider the materials, their effect and product.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Vicomtesse Othenin d'Haussonville, nee Louise Albertine de Broglie, study, ca. 1845, graphite, with white heightening, on paper, France, Musée de Carpentras.

Colourism – (not to be confused with the discrimination based on skin colour) Specifically in painting, it is a style of painting characterised by the use of intense colour, which becomes the dominant feature of the resultant work of art, mostly influential in the French impressionism movement of the 19th century.

Also: a person who uses colour in s particular way, draws attention to the colour use.

HILAIRE-GERMAIN-EDGAR DEGAS, WOMAN STANDING IN A BATHTUB C. 1890–92, charcoal with stumping on beige wove paper, 43.2 x 29.5 cm, Sterling and Francine Clark Institute

Edgar Degas

After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, c. 1890-95

Pastel on wove paper laid on millboard. 103.5 x 98.5 cm. The National Gallery, London. Bought, 1959. Photo: © The National Gallery, London

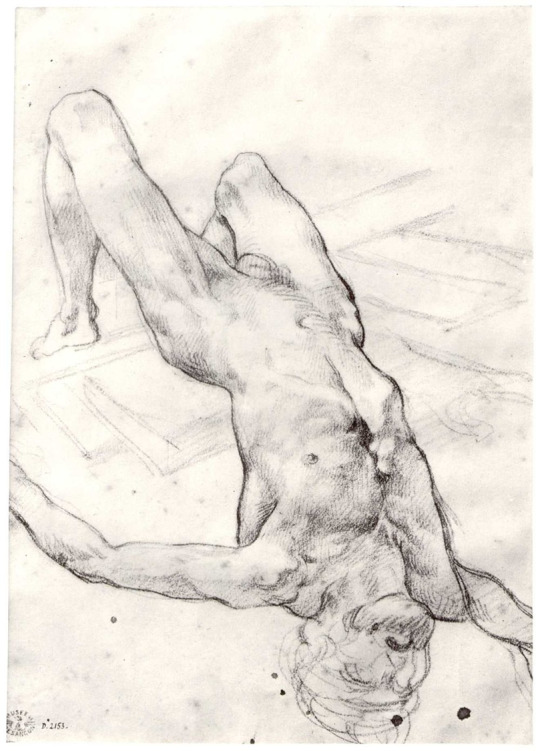

Théodore Géricault, Study for the Raft of Medusa, 1818, charcoal on paper, Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Observe the contour line (the darker outline line), surrounding the body. Note the twist and strain of the muscles and exaggeration of line and pose to create drama on the paper. Also note the materials used. Charcoal: a material that possesses a short life on paper without additives to preserve it. Something that smudges easily. Perhaps to quickly capture the body and idea and shading.

The Male nude – which surprisingly are the most common nude that exists in the western world. And this is because the basic fundaments were learnt from drawing casts, from the ancient world, or drawing from other works of art. Sketching development and a skill development, meant drawing bodies and getting to access to more complex forms to keep learning.

The RA is doing an exhibition on Impressionist on paper, which from the photos of artworks in this post, I recommend going to and seeing and judging for yourself, the use of materials and their effects.

On Degas and pastels: you can over saturate paper with pastels, muddying the colour. Critics of Degas spoke out, how his portrayal of bodies appear bruised. Degas was less interested in accuracy, more into the exploration of light on the body, the illumination, and the space it inhabits.

Genres of painting: Landscape, Portrait, Still life, Genre, Historical, Allegorical:

Allegorical paintings covered mythos. These were most prominent and popular when the state collected paintings, rather than when commissions came into prominence, and private ownership of painting rose.

Impasto: when paint stands off from the canvas. An Italian word for “mixture,” used to describe a painting technique wherein paint is thickly laid on a surface, so that brushstrokes or palette knife marks are visible. A pastose surface is one that is thickly painted.

19th century: paints in tubes begin to make an appearance.

Plain air: painting outside, open air painting. A common impressionist's expression.

Claude Monet

Cliffs at Etretat: The Needle Rock and Porte d’Aval, Pastel on wove paper, c. 1885. 39 x 23 cm. National Galleries of Scotland. Accepted in lieu of Inheritance Tax by H M Government from the estate of Miss Valerie Middleton and allocated to the Scottish National Gallery, 2016

Drawings always have a subjective idea of being ‘finished’ surrounding them. A rising problem surrounding the impressionist artists was critics perceptions of the artworks seeming unfinished, which could decrease a value of an artwork.

Berthe Morisot, At the Beach in Nice, 1882, pencil and watercolour, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum.

Note the signing of this particular artwork, in the bottom left corner. A tendency that arose after an artist died and their work became more famous or popular, their families would sign the work in their name.

Moreover, looking at this artwork it may surprise some to know that watercolour is considered a less prestigious material to use. As opposed to oil painting, which carries a greater prestige due to its difficulty to use and master. Leaving less room for imperfections. As a snide response to the impressionist movement, critics suggested that these artist under this movement, stick to and use watercolour.

Consider critics opinions of materials and how that translates to accessibility and intension.

Watercolour is actual a far more accessible material than oil painting and can give you a great finish, especially for artists that were painting on open air and their surroundings live.

#art#artwork#writing#essay#paintings#art tag#art hitory#art exhibition#art show#art gallery#lecture#essay writing#writers#creative writing#writeblr#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#education#learn#teaching#learning#students#educators#artists#artists on tumblr#drawings#illustration#art style#history#histoire

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

mermaids attacking a ship

in a manuscript of "la fleur de vertu", illuminated by the master of françois de rohan, france, early 16th c.

source: Paris, BnF, Français 1877, fol. 35r

#16th century#mermaids#hybrids#Le Maître de François de Rohan#la fleur de vertu#Fiore di virtù#sirens

316 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been down a rabbit hole wondering about medieval jewelry (and if I can reproduce it despite having no metalworking skills, to which the answer is mostly no) lately & I figured I would share the fruits of my museum collection searches for other medievalists/hobbyists/reenactors/nerds.

Jewelry of the 13th Century Anglo/Francosphere

TL;DR

Metals: 🟨 gold(tone)

Stones: mostly 🔵 cabochon, rarely 💠 simple cut, some carved 🗿 intaglio or cameo

Stone Colors: warm blues, emerald green, purples, burgundies, reds

Materials: enamel, 💎 gemstones (garnet, Ceylon sapphire, ruby/spinel, emerald) or glass paste imitations, ⚪ semi-precious stones (pearl, lapis, jasper, carnelian, coral, turquoise, porphyry)

Settings: bezel (oval and rectangular); ⚜️ intricate metalwork; more visible and textured metal than modern jewelry; more mixtures of stones and colors than modern tastes

Motifs: ◯ round, ✤ quatrefoil, ✙ cross, ✸ star (even numbers of points), ♣ trefoil, ❦ floral, 🐉 animals, 𝕬 inscription

Formats: brooches, ornamented clothing, rings, pendants, circlets, cuffs (rare)

A detailed look:

Some forms of jewelry that were very popular in the Roman Empire and are again today were just not the thing in the middle European Middle Ages. (Earrings, for example, seem to have barely existed. This is partially at least because ears were covered--by coifs and caps, hair, and (for women) braids or the chin strap and fillet/wimple/gorget.) In fact, a lot of the places we would put jewelry against our skin today were covered.

This left some other options:

Jewelry on Clothing

Medallions

Okay, these aren’t jewelry, strictly speaking, but they’re metalwork ornaments associated with a person.

Enamel Mitre Medallions

OA 3437 and OA 3438

Before 1291, Ile de France

Louvre, Paris

photos (c) Musée du Louvre / Stéphane Maréchalle 2015

Cloisonné and plique enamel over gold and copper, with decorative motifs of trefoils, quatrefoil, and stars in a palette of dark blue and green with accents that may once have been ruby red.

Appliqué Medallion

# MRR 256

13th c., Limoge

Louvre, Paris

photo (c) Musée du Louvre 2014

Gilded copper (though most gold is worn off) with quatrefoil champlevé enamel in emerald green, lapis blue, and white or off-white.

Brooches

Perhaps the most prevalent medieval jewelry item in the Anglo & French regions. These were worn at the shoulder for men and breast for women, often anchoring a cloak, or to close the collar. As the ornate fermail and double-ring brooch suggest, these ran the gamut from practical to incredibly decorative and ornate.

Garnet & Silver Gilt Animal Ring Brooch; Green and Blue Glass and Gilt Ring Brooch

Left, # 2003,0703.1

13th century; found in Suffolk, England

British Museum, London

photo (c) The Trustees of the British Museum

Right, # M.28-1929

13th c., England

V&A, London

photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Cabochon garnets or carbuncles in the gilded silver brooch (L), perhaps once paired with smaller stones in the eyes of metalwork animals that bite the pin bracket. The right brooch, also silver gilt, sports two glass paste emerald and sapphire "gems" in cabochon. It was probably a lover's token; it reads (in Lombardic-lettered French) IOSV ICI ATI VCI or "jo su[i] ici a t[o]i v[o]ici" which I might translate as "I am here with/belonging to you, look!"

Ruby & Sapphire Ring Brooch; Sapphire, Garnet, and Pearl Fermail

Left, # 6808-1860

1275-1300, England

V&A, London

photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Right, # OA6287

1250-1300, France

Louvre, Paris

photo (c) Musée du Louvre

Blogs often claim that stones were only polished en cabochon until the 16th century, and that medieval jewelers couldn't cut gemstones. But this 13th-century gold ring brooch (left) pairs table-cut purple rubies with collet-set cabochon sapphires, and may evidence early medieval gem-cutting or reuse of Roman cut stones. The silver gilt fermail, right, includes pearl beads, garnets and sapphires both cut and cabbed, and one glass paste cabochon. Both are intricately textured, with punchwork (L) and floral metalwork, probably cast and then attached (R).

Double Ring Brooch with Sapphire and Glass "Emeralds"

# M.26-1993

13th c., England

V&A, London

photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This gold double brooch is so small they think it was for a woman or child. Central sapphire cab is flanked by glass paste "emeralds" in bezel settings and metalwork featuring two animal heads.

Jewelry on the Body

Rings

Many are probably familiar with the signet ring, used for pressing into sealing wax, which could be intaglio-carved gemstone or metals. There were also a number of decorative and/or talismanic gemstone rings.

LtR:

#M.7-1929 | #M.180-1975 | #OA 11265

1250-1300, England | 1250-1300, Engl/France | 13th c., Engl/France

V&A, London | V&A, London | Louvre, France

photos L&C © Victoria and Albert Museum, London | R (c) Musée du Louvre

Sapphire in gold is the name of the game when it comes to rings in the thirteenth century; even the purple stones on the left are purple sapphires. (Sapphires were said to aid chastity, purity, and the effectiveness of prayer.) For larger stones, the bezel often has claws added (L); the central ring is an example of a full claw setting that modern viewers might find surprisingly tall. Naturalistic flourishes are added (C & R); these might be pre-cast then attached to the base (R).

Pendants

We equate pendants with necklaces, but their medieval applications also included wear as badges, from headpieces, and on horse decorations.

Left, bloodstone jasper cameo in silver setting

# MRR 218

1100-1300, France?

Louvre, Paris

photo (c) Musée du Louvre / Jean Blot 1984

Right, champlevé enamel, gilt copper, and paste "emerald" (harness) pendant

# 1976.169

13th c., France

Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

photo CC0 Open Access

Statue Jewelry

From here, we get into the really ridiculous stuff; the previous categories could be relatively everyday (as much as ornamentation reserved exclusively for the wealthy can be an everyday thing) but the following examples are astonishing displays not necessarily for wear.

"La Couronne" de Vierge et l'Enfant d'ivoire de la Sainte-Chapelle

# OA 57 B

1250-1300, France

Louvre, Paris

photo (c) Musée de Louvre

This was not even a crown for a person, but rather for a painted ivory statue of the Virgin Mary, holding her infant son. (Though circlets, even set with stones, were sometimes worn as part of women's head dress.) It's incredibly ornate gold, set with pearls, garnets and rubies, sapphires, and turquoise (?) en cabochon.

Anneau de Saint-Denis

# MS 85 BIS

1200-1215, France

Louvre, Paris

photos (c) Musée du Louvre / Daniel Arnaudet 1990

This astonishing piece, which is ring-sized but now displayed as a cuff on an ivory hand, is made of gold and displays every possible gemstone appearance characteristic of the period. The front piece has a central sapphire and is surrounded by quartz with red backing (mimicking ruby/garnet), amethysts, pearls, and sapphires, some set on yellow backing (mimicking turquoise?). Most are en cabochon on this face, but two are faceted and two intaglio. Were this not enough, the three other 'faces' of the ring are set with gems as well, two cameos (probably sapphire and garnet?) and one amethyst intaglio set in ornate gold filigree.

#medieval#jewelry making#lapidary#history of fashion#historical jewelry#1200s#reenactment#England#France#enamel jewelry#ring brooch#fermail#intaglio#cameo#gemstones#infodumping#now time to go to the bead store#material history#you would think this is for my research or academically relevant but it's not I just couldn't stop looking at shiny things help#photos not mine#photos for educational purposes and not for commercial reproduction#louvre#v&a museum#british museum#cleveland museum of art

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

CPom on Polina Edmunds's podcast - pt 1

Christina's mom was a skating coach when she was little - put her in skates at age 3, loved it right away. Anthony's parents didn't want him to skate originally, Polina's mom convinced them, said he was like a wind up toy as soon as his feet hit the ice and loved it. Both moved to Michigan separately at 13, then teamed up shortly after

Christina started ice dance at 6 or 7 - loved the dresses. jumping wasn't her thing. Anthony drawn to the storytelling. Anthony's parents coached him with his previous partner til he moved to Igor - at 12/13 he wasn't listening to his parents any more, so they thought going to a more professional environment would be good for him and sent him alone to Michigan

Teamed in 2014, been almost 10 years - Christina: everything just clicks, can't imagine skating with anyone else. Anthony- both left home early, relied on each other through ups and downs. A lot of history - can't imagine doing this with anyone else.

Careers in ice dance are long [compared to singles]- C: you have to consistently deliver good programs and stay in shape for so long. people at the top make it look easy, but it's a lot of work. [we] take it one year at a time. A: this is our 6th season in seniors, we're still pretty new compared to teams who are in their 12th, 14th, 16th seasons. continuing to grow and work on ourselves. longevity is key. make sure we're not injured.

Switching from Igor to Scott:

C: many reasons why we decided it was best to leave - wanted a new approach to skating, new maturity, needed new people to bring a different energy. we've never looked back and thought maybe we should have stayed. we're really really happy with where we are now. it's such a healthy training environment and so positive all the time, and it really inspires us to bring the best versions of ourselves to the rink every day. feels very authentic and where we're supposed to be

A: because like you said Polina, we spent most of our 10 years with Igor, the transition was pretty hard on us. and only now 2 years with Scott, I'm looking back like this was the best decision we ever made.

The energy he and Madison and Adrian bring is amazing. It's unbelievable the amount of passion they have for the sport. What they create together is beautiful, and also being part of IAM and having the coaches in Montreal helping us out. and we had the great opportunity to choreograph with Marie-France for our Summertime program - having all that together this is the best decision we've ever made.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

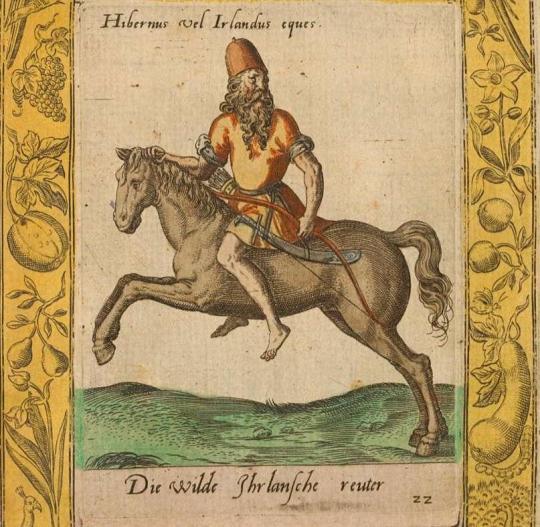

Questionable Images of Irish Horsemen

As a follow-up to my post about the problematic nature of costume books, I want discuss some of the other portrayals of the Irish that show up in them.

'A "wild" Irish rider' from Illustrations de Diversarum gentium armatura equestris by Abraham de Bruyn published c. 1578. Several copies of this book exist including one in the Bibliothèque nationale de France and one in the Wellcome Collection.

Looking at this image, I think that Abraham de Bruyn either never actually saw an Irish rider and based this off description alone, or he was intentionally mocking the Irish. There are 2 glaring issues with this portrayal which, when taken together, convince me of this.

The first issue: the Irish man is riding bareback and bridleless. He is the only rider in de Bruyn's book of equestrians shown without some kind of tack. The 16th century Irish rode with saddles and bridles. Multiple primary sources confirm this. John Derrick, even though his book was anti-Irish propaganda, still showed the Irish using saddles and bridles:

The taking of the Earl of Ormond in anno 1600 also shows Irish horses with saddles:

The text next to the horses says, "More horses unbrideled feedinge [sic]," which implies that Irish horses wore bridles when not feeding. English writers Edmund Spenser and Luke Gernon, who lived in Ireland in the late 16th and early 17th centuries respectively, both explicitly described how the Irish saddle and style of riding differed from the English.

My second issue with de Bruyn's illustration: the Irish rider is grasping the horse's left ear in his right hand while the horse is galloping. There is a partial explanation for this bizarre position. An account from an anonymous traveler who visited Ireland c1579 mentions that the Irish mounted by seizing the left ear of the horse (Maxwell 1923), but de Bruyn's rider is shown riding a galloping horse. Even if the Irish were grasping the horse's left ear in their right hand to mount, I cannot imagine that they continued doing so while riding. It would be problematic for several reasons. Horses bob their heads up and down while they are running. (If you have never ridden a horse, this video gives a decent idea what that looks like.) This bobbing would make it difficult and tiring for the rider to keep hold of the horse's ear while they are running. Furthermore, grasping the horse's opposite ear while riding would require leaning forward over the horse's neck while simultaneously leaning slightly sideways. This would incredibly awkward and probably throw off the rider's balance. (It has been 20 years since I took horseback riding lessons, but I do remember that balance is important.) Finally, horses like to move their ears around, and I think they would fight this.

However, in spite of its mistimed portrayal, the fact that de Bruyn seems to have been aware of this specific detail of Irish horsemanship, but either didn't know about or chose not to include Irish tack suggests that he was either working with incomplete information or deliberately making a mockery of the Irish. Neither of these options makes me inclined to trust this image as a depiction of Irish clothing.

Irish soldier (left) and Scottish soldier (right) from Sacri Romani Imperii Ornatus. Item Germanorum, diversarumque gentium peculiares vestitus. vol. 1 by Caspar Rutz published 1588

Caspar Rutz' book Sacri Romani Imperii Ornatus includes a very similar-looking Irish soldier. From the publication dates, I initially assumed that Rutz' soldier was based on de Bruyn's rider. With one small exception, their outfits are basically identical.

Both the rider and the soldier wear a knee-length tunic with long fitted sleeves, belted at the waist. The tunic flares out significantly at the bottom, suggesting that it has triangular gores or godets in the lower part. The tunic is a soft, unstructured garment, a clear contrast to the shaped doublet of Rutz' Scottish soldier. Doublets from this period could be heavily stiffened and shaped with interlining (Arnold 1985). The tunic is probably made of linen or light-weight wool.

The shorter length and long tight-fitting sleeves make this tunic significantly different from the typical 16th c. léine. The 16th c. léine was an ankle-length garment that could be belted up to waist length and had voluminous hanging sleeves that stopped several inches above the wrist. The tunic in Rutz' and de Bruyn's prints does look like one in Albrecht Dürer's 1521 painting of 2 gallowglass, so it may be something that the Irish wore for combat.

A typical 16th c léine (left) and Dürer's gallowglass (right)

The men in both Rutz' and de Bruyn's illustrations are wearing sugarloaf hats embellished with feathers. The sugarloaf hat was a continental fashion rather than an Irish one. Several extant examples of imported 16th-17th c. hats have been found in Ireland though (Dunlevy 1989), so some Irish people were wearing foreign styles during this period.

Both the soldier and the rider are bare-legged. The Irish riding barelegged is another detail mentioned in the c1579 anonymous traveler's account (Maxwell 1923).

Both outfits include a simple knee-length cloak which fastens at the throat, but these cloaks have a significant difference in cut. The neckline of the cloak on de Bruyn's rider has a collar with straight or concave edges and a square corner. These square-cut collars are found on English and continental cloaks in this period (Arnold 1985). The neckline of the cloak on Rutz' soldier, on the other hand, has a turnback with a convex edge and no visible corners. This is a feature of an Irish brat rather than an English cloak.

de Bruyn's rider in an English cloak vs Rutz' soldier possibly wearing an Irish brat

This subtle but culturally significant difference makes me believe Rutz' illustration is not a copy of de Bruyn's, though they may have both been copied from the same source image. de Bruyn likely either didn't know or didn't care about the difference between a cloak and a brat.

Another German book, Stammbuch des Hans Lorenz von Trautskirchen und des Hans Jörg von Elrichshausen unter Verwendung von Bruyn, Abraham de: Diversarum gentium armatura equestris, published between 1575-1615 states in its title that it uses de Bruyn's illustrations of riders. Its version of the Irish rider is slightly different though.

This version leaves off the hat decoration and the cloak completely but keeps the unrealistic ear-grasping position of the rider. The position in the image is only possible because of the unrealistic proportions of the horse. Even on a small horse like a Shetland pony, this actually wouldn't work. Grasping the horse's ear would require the rider leaning forward or at least straightening out their arm.

Rider on a Shetland pony. Note the distance between the rider's hands and the pony's ears.

Finally, there is a painting of an Irish man in Kostüme und Sittenbilder des 16. Jahrhunderts aus West- und Osteuropa, Orient, der Neuen Welt und Afrika, published c.1575-1600 which might be based off of these.

I am not sure why he appears to have just one hanging sleeve or why his triús appear to be rolled up at the ankles. The images in this book appear to be poor-quality copies of other books. I discussed the Irish woman in this book in my previous post.

Biblography:

Arnold, Janet (1985). Patterns of Fashion 3. Macmillan, London.

Derrick, John (1581). The Image of Irelande. London.

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Gernon, Luke (1620). A Discourse of Ireland.

Maxwell, Constantia (1923). Irish History from Contemporary Sources (1509-l610). Unwin Brothers LTD, London.

McClintock, H. F. (1943). Old Irish and Highland Dress. Dundalgan Press, Dundalk.

Wilde Irishe (2020). Horseboys: Irish Lackeys, Irish Footmanship.

#art#irish dress#irish history#dress history#16th century#historical fashion#historical men's fashion#gaelic ireland#irish mantle#headwear#bratanna

18 notes

·

View notes