Text

Boys in Pink

When people comment on images of 'cross dressed' little boys on social media and say with anger 'why are you letting him wear girls clothes?'...sorry, but did I miss something?

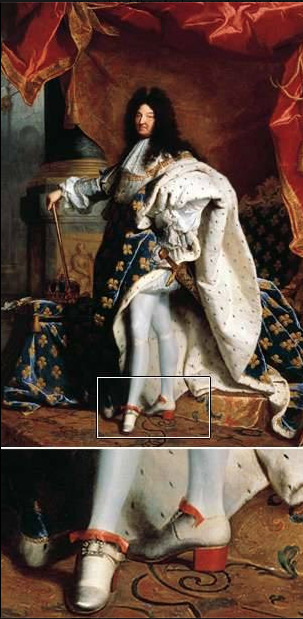

As I understood it - men were the ones who invented heels to horse ride and also to be taller and more imposing in the Kings courts... Men are the ones who introduced them to main stream fashion.

Kilts and Greek attire predates us girls wearing skirts for the first time in the 60's, so you boys started 'skirts' before we ever did.

Girls adopted these things from guys!

...Such backward behaviour stopping boys wear what they want. Meanwhile girls in jeans, bowler hats, army boots, teeth grills, short back and sides, tattoos, whatever we want - and - no one bats an eyelid. Stop fucking up your boys with your homophobic sexist nonsense. They're literally killing themselves because of this false concept of 'being a man'.

It's suicide awareness month, and if you didn't know - guys struggle to be open about their feelings and so do it much more than women. Why? - because #boysdontcry - ask the veterans everyone's doing press ups for right now.

Kids don't have many issues - sexism, racism, gender confusion, etc etc until grown ups push it on them. Grown ups are their issues.

Dressing up as spider man doesn't make you a insect mutant. Dressing up as a girl doesn't make you have a sex change. It's learning empathy and exploring your identity.

To stop a boy doing that is just a direct insult to women and femininity. Something they're fatally lacking. Celebrating boys clothes on girls, is a direct compliment to masculinity. Letting boys look after baby dolls is even better! - funnily enough babies love attentive fathers. This makes for a happier marriage.

Stop being such a fun sponge and enjoy people's differences. See the benefits of having both qualities in your emotional repertoire. Skirts over trousers don't compromise any religions. There's no excuses. Muslim dudes and choir singers wear dresses all day long FFS! Get a grip.

[Originally a Facebook comment on a thread 3rd September]

#thisgirlcal#gender#judithbutler#sexism#suicide#parenting#homophobia#masculinity#manup#beaman#gendertrouble#skirts#crossdressing#children#childhood#gender dysphoria#gender dysmorphia#crossdresser#lgbt#lgbtq

0 notes

Text

Links on Seed Patenting and Food Sovereignty

http://levine.sscnet.ucla.edu/papers/intellectual.pdf

http://www.globaljustice.org.uk/what-food-sovereignty

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/02/201224152439941847.html

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/PGR/SoW1/SoWshortE.pdf

http://no-patents-on-seeds.org/

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/02/201224152439941847.html

https://www.geneticliteracyproject.org/2014/04/22/patents-and-gmos-should-biotech-companies-turn-innovations-over-to-public-cost-free/

http://levine.sscnet.ucla.edu/papers/intellectual.pdf

https://aeon.co/opinions/save-the-soil-to-save-the-earth-before-we-have-to-leave-it

https://aeon.co/essays/is-sustainability-sold-at-supermarkets-or-farmers-markets

http://www.fao.org/about/en/

http://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/insight/economic-cost-food-monopolies

https://www.jstor.org/stable/25123894

http://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/categories/management-category/case-studies/

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/02/201224152439941847.html

Navdanya with Greenpeace http://www.navdanya.org/campaigns/biopiracy

http://www.asyousow.org/

http://bettercotton.org/resources/research/

http://bettercotton.org/resources/

http://bettercotton.org/about-bci/bci-reports/

http://www.worldwildlife.org/industries/sustainable-agriculture

http://www.worldwildlife.org/industries/cotton

http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/files/csr-sme/tips-tricks-csr-sme-advisors_en.pdf

http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/PGR/SoW1/SoWshortE.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Value_of_Earthhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Value_of_life

http://m.nbr.co.nz/article/Moxie-Sessions-way-sooty-orca-why-business-needs-move-beyond-bumper-sticker-csr#bmb=1

http://corostrandberg.com/

http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/258977.pdf?acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true

http://www.jstor.org/stable/258977?seq=7

www.csreurope.org

www.accountability.org

www.bsr.org

www.bitc.org.uk

www.corpwatch.com

www.societyandbusiness.gov.uk

www.csrwatch.com

www.csrwire.com

www.ethicalcorp.com

www.sricomapss.org

www.socialfunds.com

http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sustainable-business/files/csr-sme/tips-tricks-csr-sme-advisors_en.pdf

0 notes

Text

Images & Strategic Corporate Marketing Planning

0 notes

Text

The Long Green Revolution

The Journal of Peasant Studies, 2013 Vol. 40, No. 1, 1–63, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.719224 The Long Green Revolution Raj Patel ...Agricultural Knowledge Initiative. This initiative will invest US $100 million to encourage exchanges between American and Indian scientists..P1 We might look further back and see Enclosure as the original depeasantization (Araghi 1995), and the originary moment of the creation of capitalist value (Wood 2000, though see also Allen 1999). P3 **For this task, McMichael and Friedmann’s idea of ‘food regimes’ is useful. A food regime itself is a ‘rule-governed structure of production and consumption of food on a world scale’ (Friedmann 1993, 30). P3 One needn’t be a card-carrying Althusserian – and many are not (Goodman and Watts 1994) – to find questions of legitimacy, institutions and ideology important. P3 Green Revolution because it so clearly relied on institutions to corral and maintain a cocktail of coercion and consent within the dominant hegemonic bloc (Gramsci 1971). P3 Friedmann suggests, one of the things that is now known among international development policy elites is that subsidized exports are foolish. P4 In pushing for a ‘second Green Revolution’, the first Green Revolution needs to be sold as a success. P4 How can the phenomena of ‘population’, with its specific effects and problems, be taken into account in a system concerned about respect for legal subjects and individual free enterprise? In the name of what and according to what rules can it be managed? (Foucault and Senellart 2008, 317) p4 2. What was the Green Revolution? P5 - digression It is not a violet Red Revolution like that of the Soviets, nor is it a White Revolution like that of the Shah of Iran. I call it the Green Revolution. (Gaud 1968) p5 - anti communist Greg Page, the Chairman and CEO of the food, agriculture and financial services giant Cargill, recently observed that ‘we live in a time where the world is the furthest it has ever been from caloric famine. . . the number of calories that the world’s farmers are producing per inhabitant of the world are at all time record levels’ (BBC 2011). P6 **But to wonder why Mexico was chosen for the Rockefeller Foundation’s generosity is to begin to unravel the standard narrative a little, and to peel back the social construction of the ills that the Green Revolution was intended to remedy. P7 Division of Natural Sciences at the Rockefeller Foundation Carl Sauer, a geographer at the University of California at Berkeley, made repeated calls to the Rockefeller Foundation to desist : A good aggressive bunch of American agronomists and plant breeders could ruin the native resources for good and all by pushing their American commercial stocks. . . And Mexican agriculture cannot be pointed toward standardization on a few commercial types without upsetting native economy and culture hopelessly. P8 ** (>_<) ...Norman Borlaug ‘realized that Mexico’s traditional wheat-growing highland areas could not produce enough wheat to make the country self-sufficient in wheat production’. (Dubin and Brennan 2009, 21). For the majority of Mexicans, however, corn was a far more important crop. Nearly ten times more land was planted with corn in 1950 (4,781,759 hectares) than wheat (555,756 hectares) (Direccio ́ n General de Estadı ́ stica 1955). But wheat tended to be grown by commercial farmers with models and resources more comparable to their US counterparts than corn production. P9 Green Counter-Revolutionaries who swiftly earned themselves the label ‘peasant conservative’ - p10 Foundation was sensitized to the concern – voiced most often, though not exclusively, by John D Rockefeller III during his tenure on the Foundation’s board from 1946 to 1956 – that impoverished and hungry people might be more amenable to communism. P11 ‘Where hunger goes, Communism follows’ (Rieff 2011) p11 US Agricultural Trade and Development Assistance Act (PL 480) in 1954 - p11 ... it was the kind of knowledge that benefitted commercial rather than subsistence farmers, and because the Foundation had been informed by both the experience and ‘success’ of its US-land-grant-inspired techniques in Mexico... P12 Yet, as Paddock notes of the period 1967–70, Indian production of barley, tobacco, jute, chickpeas, tea and cotton all increased by 20–30% without the benefit of Green Revolution investment, and without similar self-congratulatory narratives of surplus and bounty (Paddock 1970). P13 ** International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) ...what do markets require? To answer this, Polanyi offers the best guide to the myths of self-regulating markets... P15 **In the Philippines as elsewhere, policies that favoured market-led approaches to food production required state support. In order to fight communist uprising and peasant insurgency through a healthy economy, the state need to be intimately involved to administer two of the Green Revolution’s most potent tools: subsidies and violence. p16 ...the Green Revolution would not have succeeded without subsidies. P16 Paddock, quoting a 1963 speech by the US Department of Agriculture’s Director of Economics Don Paarlberg,5 points to a sentiment widely acknowledged: ** This is the inescapable fact that a price artificially held above the competitive level will stimulate production, retard consumption and create a surplus. . . . It is the product of human institutions, not simply a consequence of rapid, technological advance. It may or may not be accompanied by a scientific revolution. We could create a surplus of diamonds or uranium or of avocadoes or rutabagas simply by setting the price above where the market would have it and foregoing [sic] cost production control. A surplus is not so much a result of technology as it is a result of intervention in the market. (Paddock 1970, 898) p16 Indira Gandhi’s son, Sanjay, took it upon himself to address concerns about insurgent urban populations and population growth directly, by managing a program of slum clearance and forced sterilization, the latter justified in the name of the national interest (Blair 1980, 259, Henry 1976). P17 A central contention has been that the Green Revolution at best overlooked the rural poor, and at worst exacerbated their plight. P18 ** "India’s Green Revolution provides a clue to this aspect of differentiation. The promise was that its biochemical package of improve inputs was ‘scale neutral’, meaning that it could be adopted, with benefit, on any size of farm – unlike mechanization, for instance, which requires minimum economies of scale. However, ‘scale neutral’ – an attribute of a given technology – is not the same as ‘resource neutral’, a social attribute connected with the question ‘who owns what?’ and that requires asking about differentiation and its effects." (Bernstein 2010a, 105) p19 ...a persistent ‘yield gap’, a gulf between conditions that might be achieved with access to capital and high quality land, and that observed in the real world of poorer farmers (Licker et al. 2010). P19 ‘The scientists have responded to their critics...there has been a change in the research strategy of plant breeding: more emphasis is now placed on the search for ‘‘peasant-biased’’ technical change’ (Griffin and Boyce 2011, 10). P 21 Freebairn finds that : Over 80% of the sample of published studies . . . concluded that greater inequality resulted. Notwithstanding this preponderance of evidence, the overwhelming conviction of operating agencies, from local to international, has been that the improved technologies offer the best solution to the problems of agricultural and rural development and growth. Indeed, a significant number of scholars join in this very positive view of the impact the new technology has on agricultural and rural regions. (Freebairn 1995, 277) - p24 Markets are not natural (Polanyi 1944) - p26 ...Hart’s work on the Muda Agricultural Development Authority. She studies the application of mechanization to harvesting and transplanting tasks traditionally been carried out by women. P27 The International Assessment on Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development points to the importance of such knowledge in the creation of sustainable food systems (IAASTD 2008) p28 Claims for the merits of the Green Revolution abide by a narrow definition of agricultural productivity in which concerns for sustainability are largely absent. P29 - also see whole page for summary of downfalls overlooked by 'Green Revolution' ... by 1989, Mexico had become one the largest food-deficit countries in the developing world, having to import 40% of its grain requirements (Barkin 1990). P31 McNamara announced that in its next five-year lending period from 1974 to 1978, the World Bank would increase its agricultural lending activity from USD 3.1 billion to 4.4 billion, 70% of which would contain a ‘component’ for the smallholder. This ‘small green revolution’ aimed to propel the smallholder sector to the forefront of the Green Revolution, to serve as a direct rebuttal of critical claims that the Green Revolution only served larger, commercial farming units. P32 Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research p33 Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) p36 As Ghosh has observed, the financialization of food deepened with the passing in 2000 of the ‘Commodity Futures Modernization Act [which] effectively deregulated commodity trading in the United States, by exempting over-the-counter (OTC) commodity trading (outside of regulated exchanges) from CFTC oversight’ (Ghosh 2010). P36 The dismantling of international marketing agreements, such as the International Coffee Agreement in 1989, preceded the full liberalization and subsequent financialization of a range of commodities under the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (Newman 2009). The World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Agriculture cemented neoliberal doctrines in agriculture, even if in the Global North these doctrines sat uneasily with ongoing transfers to agribusiness. P36 ** Rajiv Shah, the current administrator of USAID: We are never going to end hunger in Africa without private investment. There are things that only companies can do, like building silos for storage and developing seeds and fertilizers. (Strom 2012). This is an almost wholesale reversal of the views about the role of the state argued above by Willam Gaud, Shah’s predecessor p36 Multilateral Agreement on Investment Further reading : Gordon Conway’s 'A Doubly Green Revolution' Bill Gates "The next Green Revolution must be guided by small- holder farmers, adapted to local circumstances, and sustainable for the economy and the environment." P38 Note the absence of history, the misremembering of the Rockefeller Founda- tion’s initial interest in Mexico and the erasure of the Foundation’s anti-communist, pro-US-state thinking in the original Green Revolution. P38 organizations to represent farmers’ interests. Such organizations exist worldwide, such as the International Federation of Agricultural Producers (IFAP) and La Via Campesina, and have for decades... p39 **World Bank’s 2008 World Development Report on Agriculture for development ...the Rockefeller Foundation was in a position, in 2006, to partner with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The offspring of this philanthropic encounter was The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa... P39 But a central problem, the project team reports, was that ‘the majority of farmers in the project locations viewed agriculture as a way of life and not a business. One of the main objectives of the Association is therefore to reorient the farmers to business. P41 Citizens’ Network for Foreign Affairs (CNFA), a pro-market NGO with extensive experience in bringing markets to the former Soviet Union p41 ...GRAIN (whose data provided the data for subsequent World Bank analyses) has detailed land grabs p44 **Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can it Yield Sustainable and Equitable Benefits? (Deininger et al. 2010) The authors do their best to bend the data to the report’s subtitle. P44 As Behrman and colleagues note, throughout the process of acquisition, gender inequities in bargaining power, access to information, public goods and resources can leave women worse off from the moment the land beneath their feet is sold p44 In sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia, women are vital contributors to farm work, and typically in charge of selecting food for, and feeding their families. Yet compared to their male counterparts, women farmers are less productive and unable to reach their full potential. Yields on women’s plots are typically 20 percent to 40 percent less than men’s, putting rural families and communities at risk of not having enough nutritious food to eat or any extra to sell at the market. (Gates Foundation 2011, 3) p45 -- "patriarchy, and its consequences for rural women and girls’ lives, might be put forth, but instead the foundation offers this: The reason for this gender gap is that women have less access to improved seeds and other inputs, training, and markets. This gap has real consequences: households are less productive, new approaches and technologies that could increase the amount of food they grow are less likely to be adopted by women, and children in poor household are undernourished. (Gates Foundation 2011, 3) Few analysts of gender would vouchsafe that gender gaps are caused by a lack of access to improved seeds. Differential access to agricultural inputs are a symptom of an inequality in power that keeps more women hungry than men, women poorer than men, with differential access to land (Agarwal 1994) and education (Klasen 2002), shouldering the triple burden (Moser 1989), and so forth (Behrman et al. 2012). Yet here it appears that by fixing a single symptom, one might address a cause. It’s wishful thinking of course" p46 -- ... one of the consequences of the technics of the New Green Revolution has to normalize a policy approach based on deficits in blood chemistry, rather than inequalities in power. P47 While over 850 million people suffer from chronic hunger, two billion people suffer from malnutrition, with around six million of the 10 million deaths of children under five in developing countries related to micro- nutrient deficiency (Frison 2008). P47 Traditional micro-nutrient rich crops such as pulses, vegetables and fruits have been substituted for cereal grains which have a much lower nutritional value. P47 In south India, this decline in the production of pulses has been accompanied by an increase in iron-deficiency anemia in pre-menopausal women (Welch and Graham 2000). P47 It is, however, possible to reject the Manichean logic of ‘disaster or capitalist sustainability’ by looking at the evidence. P48 Badgley et al. conduct a modelling exercise demonstrating that ‘organic methods could produce enough food on a global per capita basis to sustain the current human population, and potentially an even larger population, without increasing the agricultural land base’ (Badgley et al. 2006, 86). Very recently, Seufert et al. P49 though the yield difference varies: they find no statistically significant difference between organic and conventional fruit and oilseeds, and 26% and 33% less for organic cereals and vegetables respectively. They also find that the longer a farm has been organic, the better it performs.P 5? Climate change has already been deployed as an alibi for the spread of the New Green Revolution. The Gates Foundation sees adaptation – not mitigation or remediation – as the only response to climate change, in particular through the spread of drought-tolerant monoculture (Gates Foundation 2011). P51 Absent an analysis of class and power, demands for food sovereignty can conceal no less than calls for ‘pro-poor’ agriculture. The difference, of course, is that food sovereignty is precisely an invitation to analyse the power that accompanies the food system’s technologies (Patel 2009). P51 END

0 notes

Text

Financialization and its Consequences: the OECD Experience

FINANCE RESEARCH VOL. 1, NO. 1, JANUARY 2012 35 Jacob Assa, New School for Social Research Freeman (2010) documents “the huge costs to the real economy of the finance- induced ‘Great Recession’, p35 Palley (2007) points out, “judging by the increase in rentier income shares, financialization appears to have infected all industrialized economies”. This claim is supported by Power, Epstein and Abrena (2003) as well as Jayadev and Epstein (2007) for OECD countries. P35 Epstein (2001) finds financialization to be “associated with substantial economic costs: increased income inequality; increased shares of GDP going to owners of financial assets, who tend to be among the very rich in most countries”. P35 "...unequivocal trend towards the disassociation of the financial sector from the productive sphere of the economy and the concomitant expansion of financial rents”. P35 - quoting Yeldan There are many definitions of financialization. Epstein (2001) defines it as “the increasing importance of financial markets, financial motives, financial institutions, and financial elites in the operation of the economy and its governing institutions, both at the national and international level” (quoted in Palley 2007). Krippner (2005) defines financialization “as a pattern of accumulation in which profits accrue primarily through financial channels rather than through trade and commodity production”. Stockhammer (2004) defines it as “the increased activity of non-financial businesses on financial markets”. Associated with this variety of definitions is a plethora of indicators used to measure the extent of financialization. Kedrosky and Stangler (2011) measure it using the size of the financial sector as a percentage of GDP. Stockhammer (2004) uses interest and dividend income (‘rentiers’ income’) of non- financial businesses as a proxy for financialization. Freeman (2010) looks at the financial sector’s share of profits, the ratio of financial-sector profits to the wages and salaries of all private-sector workers, and the ratio of financial assets divided by GDP. Krippner (2005) uses portfolio income of non- financial firms and profits of financial vs. non-financial firms. P36 **Finance in the national accounts is defined as the sum of financial intermediation, real estate, renting and business activities (FIRE for short). P36 In 1970 only two OECD members – France and Mexico – had more than a fifth of value added coming from finance (20.6% and 23.2% respectively). By 2008, fully 28 of the 34 members of the organization had finance shares exceeding 20%, and 15 countries had shares of over 25%. P36 ... other measure of financialization, employment in finance as a percentage of total employment, tells a similar story. P36 In the earliest years for which data are available (1970 through 1994), no OECD countries had 10% or more of their working force employed in finance. P36 In relative terms financialization has gone even further, with 10 countries doubling their employment in finance to total employment ratio, five countries tripling it, and seven going much farther (Korea, Luxembourg and Spain saw their ratios increase nine-fold, Italy six-fold, Japan five-fold, and Poland and Finland four-fold). P36 GINI coefficients Table 2 shows the fixed-effects regression results where the dependent variable is inequality before taxes and transfers. The relationship between finance as a share of value added and inequality is strong and positive, with a coefficient of 0.57 in column 1 (significant at the 1% level). Controlling for per capita income yields a similarly strong parameter, 0.49 (column 2). The share of finance in employment is also significant and bigger (at 0.73 without and 0.81 with a control for per capita income in columns 3 and 4 respectively), and the regressions explain even more than those with the value added indicator (as shown by the higher R2 scores). It seems that the financialization is strongly correlated with higher inequality. Each percentage increase in the share of finance in total value added is associated with up to 0.57% more inequality, while each percentage increase in the share of finance in total employment is associated with up to 0.81% more inequality. P37 **use stats!** Financialization is then clearly correlated with slower GDP growth. Each percentage increase in the share of finance in total value added is associated with up to 0.12% slower growth, while each percentage increase in the share of finance in total employment is associated with up to 0.2% slower growth. P38 CONCLUSION The empirical evidence analyzed in this paper confirms all four hypotheses presented in section II. First, financialization has definitely taken place on a large scale in all countries of the OECD, whether measured by the increase in the share of value-added coming from the financial sector or in employment in that sector as a percentage of total employment. Second, and more importantly, this strengthening of finance vis-à-vis the rest of the economy did not come without a price. The empirical evidence clearly confirms the relationships discussed in the literature on financialization, and in particular its negative effects on equality, growth and employment. Each percentage increase in financialization is associated with between 0.49% and 0.81% more inequality (depending on which indicator of financialization is used). A similar increase in financialization is related to a 0.2% slower growth of GDP, and between 0.12% and 0.74% higher unemployment. Some blame the process of financialization for the recent economic and financial crises. Whether or not it served as one of the key factors leading up to the meltdown, financialization over the past four decades certainly seems to have negatively impacted the real economy in the developed countries of the OECD by increasing inequality, slowing down economic growth, and contributing to unemployment. It appears that, when financial machinations supersede productive enterprise, to use Krippner’s language, the overall economy suffers. P38

0 notes

Text

CEREAL SECRETS The world's largest grain traders and global agriculture

August 2012 MS. SOPHIA MURPHY INDEPENDENT CONSULTANT AND SENIOR ADVISOR AT THE INSTITUTE FOR AGRICULTURE AND TRADE POLICY DR. DAVID BURCH HONORARY PROFESSOR SOCIOLOGY, THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND DR. JENNIFER CLAPP PROFESSOR, ENVIRONMENT AND RESOURCE STUDIES AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, UNIVERSITY OF WATERLOO Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus ADM is publicly listed and Bunge is also a fully public company. Dreyfus and Cargill remain essentially family-owned businesses. P5 The ABCDs do not operate in a vacuum. They are shapers of the world they inhabit, but they are also shaped by it. New realities, particularly the rise of new economic powers, including China, Brazil, and India, as well as the re-emergence of Russia and some of the former Soviet republics as agricultural powerhouses, are reshaping the global economy. P5 The new emerging powers are not as wedded to open trade, deregulated markets, and deregulated capital flows as are the governments they now challenge (the United States and the European Union, in particular). One effect of this change in the balance of power has been to make the likelihood of a meaningful outcome to the Doha negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) improbable. These changes and their implications are only just becoming apparent. P5 **intergovernmental agency report to the G20 and the High Level Panel of Experts’ report on food price volatility. p6 However, a growing number of analyses link at least some of the food price volatility of recent years to increased investment in these markets. The Bank for International Settlements, for example, has noted that financialization affects commodity prices, especially in the short term; a conclusion that several UN reports have also recently come to recognize.2 The correlation between prices of commodities and commodity assets under management is examined in Part 2. P6 **A note on language ‘Financialization’ has entered the policy insiders’ lexicon as an overarching term to refer to the increasingly important role that investors play in the food system. Traditionally the food system involved producers (farmers) and a series of commercial interlocutors, who traded, processed, distributed, and sold food. Today, banks and other investors, as well as dedicated investment funds established as subsidiaries of the ABCDs themselves, have invested billions of dollars in food commodities with no interest in taking possession of any physical commodity. Their behaviour is intimately linked to what is happening in the physical trade of food, of course, but it also affects that trade by affecting prices and behaviour. This is what is meant by the financialization of commodity markets. A second dimension of financialization is also considered in this report: that of production itself. In this case, the term refers to the increasing involvement of investment funds of different kinds in buying or leasing land and producing agricultural commodities. P6 Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus, collectively known and referred to in this paper as the ABCD companies – in the modern agri-food system. P7 That restructuring ties into the rapid growth of the biofuels sector, large-scale acquisitions of land in developing countries by foreign investors, and the financialization of agricultural commodity markets with the rapid growth of commodity trading by investors who have no interest in acquiring or selling actual commodities. P7 Not all grain is traded: in fact, most production never crosses a border. For example, only about 18 per cent of world wheat production and 10 per cent4 of maize production is traded globally. P7 ...major shifts that are taking place in world production and trade in food, in turn a consequence of the redistribution of power along the agri-food supply chain with the emergence of global retailers such as Wal-Mart... P7 Food processors, too, are constantly in motion – Unilever and Nestlé are two continuing giants in this group, but many other firms have been swallowed up or merged into new entities... P8 Wal-Mart is today the largest firm on the planet, judged by the Fortune 500. In contrast, the only new firm in the top five commodity traders since the mid-19th century is ADM, which was founded in 1902 but which only became a global player in the 1970s. The one other change occurred in 2002, when one of the big five, the Swiss-based André, went bankrupt. Bunge is now just six years from its 200th year of continual operation. P8 **What distinguishes the ABCD firms from their rivals? First, it is their sheer scale and breadth. The ABCDs share a very significant presence in a range of basic commodities, including corn, maize, wheat, oilseeds (such as soy and cottonseed), and palm oil (see Appendix 3). In 2003, for example, the ABCD firms controlled 73 per cent of the global grain trade.11 More than that, they are highly diversified and integrated both vertically and horizontally; for example, Cargill, ADM, and Bunge not only account for more than 60 per cent of total financing of soy production in Brazil,12 but they also provide the seed, fertilizer, and agrochemicals to the growers, and subsequently buy the soy and store it in their own facilities. The big traders also transport commodities in their own rail cars and ships – for example, Cargill Ocean Transportation,13 Louis Dreyfus Armateurs, and the barges operated by Bunge along inland waterways in the USA. P9 ADM is a world leader in the origination and transportation of grains and oilseeds. Our strategy here is to extend our origination footprint as we have in Canada and Eastern Europe, and to grow our destination opportunities in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. P10 (source: ADM website) website of Cargill’s subsidiary AgHorizons says: Professionally trained customer focus teams work one-on-one with their producer customers, building long-term relationships – striving to understand their farming businesses and providing distinctive solutions, matched to their unique needs.’ P11 **The ABCDs buy grain from the elevators and then process a large share of it. Their subsidiaries then consume much of the processed grain, as feed for livestock or as feedstock for biofuels. Vertical integration means that there is little room for price discovery;30 the commodities become an internal operating cost and are not sold on the open market. ...The barriers to entry are a function of asymmetrical information – the established firms have a worldwide information system that is sans pareil. P11 **The price of grain on world markets is certainly important to them, but they can profit regardless of whether prices are rising or falling – what is important to them is to maintain the high volume of trade. p11 **the companies also have a significant advantage in their access to information. This makes volatility important: they know better than most what supply and demand are likely to be, and they make big investments every year in financial markets,32 using this knowledge to full effect. Volatile prices are good for knowledgeable speculators. p12 **These commodities – including palm oil, soybeans, wheat, and maize – are unspecialized and generic, and can easily be substituted for one another. p12 In many cases, it is almost impossible to know for sure the size of the commodity stocks these firms hold – much of that information is a tightly held secret.33 p12 ?? Source Cargill’s acquisition of Continental Grain and ADM’s acquisition of A.C. Toepfer. In addition, recent purchases by Cargill include Cargill Australia’s purchase in 2010 of the grains business of the newly privatized Australian Wheat Board (AWB), and the $300m acquisition of 85 per cent of Sorini Agro (Indonesia) in 2010. Sorini Agro is the world’s second largest producer of sorbitol, a sugar alcohol used as an artificial sweetener. P12 The finance and risk management divisions of the ABCD traders are huge and absolutely central to their businesses (see the further analysis in Part 2, and also Appendix 4). P13 In 2003 Cargill established Black River Asset Management, a hedge fund with some $5bn in assets. In 2010, Black River established two private equity funds, each worth around $300–400m, to invest in global food and farmland assets, with a focus on aquaculture in Latin America. P14 ... placing former staff in key decision-making roles in government (the ‘revolving door’), and hiring former government officials to lobby on their behalf. The companies spend a lot of time and money on influencing public and political debate on trade, production, and investment regulations at the domestic and international levels. They are circumspect about this influence, but are strategic in their aims. P14 ...each of the ABCD companies is an active participant in the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). P14 Soybean oil costs roughly twice as much to produce as palm oil and so processors have to exploit significant economies of scale to remain competitive. P16 **Amazon ‘Soy Moratorium’ Wilmar Group, a Singapore-based conglomerate that owns more than 235,000 hectares of palm oil operations in Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as fertilizer and shipping interests. P17 Louis Dreyfus is the only one of the four big commodity traders to have any significant involvement in the rice trade. P18 Cargill supplies companies such as Kraft, Nestlé, Unilever, and General Mills – and, in some cases, finds itself in competition with the food processing companies. Both Cargill and ADM do, however, manufacture a range of chocolate products, under the brand names of Peters (Cargill) and Ambrosia (ADM). ...Cargill’s extensive poultry operations supply retail outlets throughout Europe and North America. Cargill companies supply all the eggs used by McDonalds in the USA,53 and Cargill recently established poultry operations in Russia to supply McDonalds fast food outlets there (these had previously been supplied by its French subsidiary). P18 ...In 2009, Louis Dreyfus joined up with a major Brazilian sugar company, Santelisa Vale, to create LDC-SEV, the second largest renewable energy company in the world. P19 **Ethanol ** "12 per cent of global maize use in 2007 was devoted to ethanol production (in addition to the 60 per cent used for animal feed). ...and in 2010 close to 40 per cent of the US maize crop went to ethanol plants. P19 ***The history of the traders is imposing, in some cases extending over 150 years. The companies have successfully grown and evolved to create enormous fortunes and to wield very significant power – economic, political, and social – in the world’s food systems. But nothing lasts forever. The ABCD commodity traders are not immune to challenges. Here is a short list of the most pressing, which are areas for further research. First, the traders’ imperative to grow and keep on growing (Cargill likes to boast that it doubles in size every seven years) carries inherent risks and difficulties. Finding new and creative ways to attract new capital is a constant challenge. Second, the retail sector has transformed itself, and with it many aspects of the food system. Although the supermarkets’ direct engagement with farmers and production has focused on fresh produce, where the traders are not present, the challenges posed by supermarkets to some of their big customers, especially food processors, cannot go unnoticed by the traders themselves. For example, Nestlé has started to move back down the supply chain in its chocolate operations, creating competition for the historically dominant traders, including Cargill. Third, the technologies of globalization, particularly information technologies, are eroding some of the advantages cornered by the global traders. Global networks have become cheap, quick, and accessible to many more people than was the case even ten years ago. Fourth, global food markets have undergone a series of profound and possibly game-changing shocks in the past few years. The food crisis, the financial crisis, and the mounting evidence of how climate change is already disrupting food systems have all undermined confidence in global trade as a reliable mechanism for the delivery of food security. The agenda of trade liberalization that the ABCDs have invested significant energy in securing is in question in many developing countries, and in some richer countries as well. The companies are well placed to influence the newly emerging powers of the global economy, especially Brazil and also China and Russia to some extent. But they face new and important challenges to the free market ethos that has allowed them to consolidate so much power over the past 20 years." ** p20 Cargill made record profits in 2008 (nearly $4bn) as food prices shot up rapidly. The company openly acknowledges that it profits from its unique base of information. Its profits in 2008 were not due to rising commodity prices alone, but rather to its ability to predict price changes in a period of volatility. Cargill was among the first to bet on falling wheat prices in the second part of the year, based on harvest information, which enabled it to clean up in futures markets. P25 **" Financialization can be defined as the ‘...increasing importance of financial markets, financial motives, financial institutions, and financial elites in the operation of the economy and its governing institutions, both at the national and international levels’.91 Financialization – a clumsy and unhelpfully obscure word – has now entered the policy insiders’ lexicon as an overarching term for the increasingly important role that financial investors play in agri-food systems. Financialization is a factor in both the commodity futures markets (dealt with in this section) and in agricultural production itself (dealt with in the next section)" p26 Traders have used insider knowledge to manage their investments and to hedge their risks since their firms were first established over 150 years ago. ...Yet something important has changed. The connections between finance and food markets have become more intense and intricate in recent decades as a result of financial deregulation (explored in more detail below). We are only just beginning to understand the full extent of the complexity involved. Historically, banks were prohibited from the hedging activities permitted to commercial grain companies. Deregulation relaxed the rules, in the 1980s allowing financial actors, including banks and investment brokers, to sell to investors products known as derivatives93 based on food and agricultural commodities. As deregulation unfolded in a series of regulatory and legislative changes during the 1990s, these new products grew more complex. Today, financial products are often bundled with other non-food commodities, and the amounts of these derivatives that are traded on markets have grown significantly in recent years. These developments have linked the worlds of food and finance in new ways: food has become ‘financialized’. ...The way that the futures markets are set up in effect means that ‘insider trading’ is legal for these firms’ activities in the commodity futures and agricultural derivatives markets. The Wall Street Journal reported in 2009, ‘In contrast to stocks, commodities trading is the only major US market where companies are allowed to act on inside information to manage risks others might not know about. In fact, that is how futures markets were designed.’94 And the Financial Times notes, ‘Physical traders are often the first to know when crops are falling short or energy cargoes are interrupted, giving them an edge over others.’95 What the regulations say they cannot do, however, is to deliberately manipulate prices. This is forbidden for market actors, including the grain trading firms. P27 **FUTURES v HEDGING** **Questions have also been raised about whether these firms are manipulating markets for their own gain. Bunge Global Markets was found in 2009 to be in contravention of the Commodities Exchange Act by the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). Twice in March 2009 Bunge traders placed buy and sell orders for soybeans in the pre-opening trading session, which they then cancelled before the market session opened. The CFTC found that the traders had no intention of executing those orders (something that the traders openly acknowledged), but instead were deliberately seeking information about support for specific price levels. Their activity influenced the Globex (electronic trading platform) Indicative Opening Price (IOP), which is an opening price broadcast to Chicago Mercantile Exchange market feed data and all CME Globex users. The CFTC noted, ‘If successful, they would have obtained information that was unavailable to other traders. Because the traders had no intention of allowing the orders to be executed, placing the orders caused prices to be reported that were not true and bona fide...’ and as such were in violation of parts of the Commodity Exchange Act.100 The CFTC ruling was released in 2011, and Bunge was fined $550,000 for this violation and ordered to ‘cease and desist’ from violating those parts of the Act. P30 The US Commodity Exchange Act of 1936 empowered US federal regulators (now known as the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, or CFTC) to establish ‘position limits’ on ‘non-commercial’ traders who are not bona fide hedgers. Non-commercial traders are those who do not trade the actual commodity, such as speculators and banks. P30 Banks also began to request and were granted ‘no action letters’ from the CFTC. These letters provided regulatory relief by stating that the regulatory body would not recommend enforcement action against the requesting entity for failure to comply with specific CFTC rules or regulations p30 The Commodity Futures Modernization Act (CFMA) was passed in the USA in 2000, legislation that exempted OTC derivatives trade from CFTC oversight. The OTC commodity derivatives trade, including CIFs, was not subject to any position limits under this regulation, nor any reporting requirements. The Act also allowed purely speculative trading in OTC derivatives. In other words, investments in these products were not required to be hedges against a pre- existing risk for either party. In effect, the CFMA codified what the no action letters had already established, limiting the oversight of the CFTC and opening the possibility of a much higher volume of speculative trading in commodity markets. P31 "Trader firms already saw themselves as commercial actors, but in some cases they asked for exemptions from rules as well. In 2006, for example, Cargill requested exemptions from regulation from the CFTC for future sales of OTC agricultural derivative products to external customers by a new financial division of the firm. Cargill wanted to be sure that its subsidiary would be exempt from regulation if it became a separate agricultural trade options merchant. The CFTC granted ‘no action’ relief to Cargill for its soon-to-be-established subsidiary to act as an ATOM (agricultural trade options merchant – for which the rules state that the firm must be a producer, processor, or commercial user, etc.): ‘Clearly, as used in the agricultural trade options regulations, the phrase, “producer, processor or commercial use of, or a merchant handling” a commodity was intended to apply more broadly than to just first handlers of commodities. The division believes that the Applicant, as a wholly-owned subsidiary of a grain merchant such as Cargill, is an appropriate candidate for inclusion within that broader application of the “producer, processor...” category.’105 The US regulatory context was important, as it applies to the most important agricultural commodity markets in the world, primarily the Chicago Mercantile Exchange Group, which includes the Chicago Board of Trade, the world’s oldest and largest futures and options market. p31" **Dodd-Frank Bill 6100/0304 Conclusion of ABCD's : Historically, speculation and hedging in agricultural commodity markets were distinct activities. Financial investors were typically speculators; commercial operators in the grain business were hedgers. Changes to legislation and regulation have blurred the boundaries. Commodity prices are increasingly influenced by factors that have nothing to do with physical reserves. While debates have raged in recent years as to whether financial speculation in agricultural commodity markets is a leading driver of food price volatility, there is a growing consensus that there is at least a short-term impact on food prices as a result of increased financial speculation on those markets. While there is no evidence that the deregulation of commodity markets has helped the commercial sector to improve performance,124 there is a real risk that the activity is affecting prices in real markets, and therefore hurting some of the world’s most vulnerable populations. Deregulation of financial markets has created new, more complicated investment tools and products. The ABCD traders have capitalized on these developments, as have other financial institutions. These agricultural commodity derivatives have in some cases merged agricultural commodity and non-agricultural commodity assets, linking food commodities in important ways to other commodities within financial markets. The ABCD traders are facilitating the speculation of others by offering agricultural commodity tools to third party investors via their financial services divisions.. The scale of money involved in commodity trades has grown exponentially in a very short time. Experts disagree about the importance and effects of this activity, much of which is speculative, although many commentators (both outsiders and insiders) suggest that there is cause for alarm.125 The level of commodity price volatility is not unprecedented, but its significance is, because of the rapid increase in developing countries’ dependence on international markets to meet demand for food staples. This argues for caution and a need to put the onus on the ABCDs (and other financial actors) to prove that there is no harm from their activities. This raises some important challenges to the tendency of many donors to push developing countries into using financial tools, including reliance on commodity futures markets, to manage volatility. Physical food reserves and increased local production for local markets might offer stability that financial tools cannot in the current environment. ABCD firms have been very active in lobbying to influence financial regulatory reforms in both the USA and the EU. They are specifically seeking to retain their exemptions from regulations that would place limits on their levels of investment in commodity futures markets. At the same time, they are in favour of stricter regulation for banks that are carrying out similar activities. P36 Agriculture has historically been seen as a risky venture that generated low returns. This has changed in recent years, and the food system has come to be seen as a sector that will guarantee long- term growth. The reasons for this are several: The decreasing per capita availability of land; An anticipated increase in commodity prices over the long term due to finite resources and a still-growing (and increasingly rich) global population; The shift towards meat-based diets; The creation of markets in farm-related carbon credits and water rights; The increasing levels of investment by land-poor and food-deficient countries; The increasing value of farmland. P37 ** El Tejar, the world’s largest farm company. El Tejar’s majority shareholders are the London-based hedge fund Altima Partners, with 40 per cent of the equity, and the private equity company Capital Group, with 13 per cent. P38 ** In terms of its involvement in biofuels, Noble is a significant processor of oilseeds and owns palm plantations, sugar farms, and other agricultural assets. P43 Archer Daniels Midland : ADM has been involved in intense lobbying of US politicians for subsidies and incentives for ethanol production. ...It seems clear from this that ADM is not only the largest ethanol producer in the world’s largest ethanol market, but that it is also seeking a major position in the world’s second largest market. P44 ...Black River Asset Management, Cargill’s investment management firm. P45 Renewable Energy Group (REG) of Iowa. REG is a major biodiesel production company with numerous biodiesel production plants in operation throughout the USA. P46 ...continued reliance upon fossil fuels (which industrial biofuels perpetuate) ...debate around the issue of food versus fuel p47 ...the nature of the demand for biofuels (steady amounts of feedstock, 365 days a year) and the purchasing power of the customers involved have changed the relative bargaining power of various consumers against the interests of poor people (with weak purchasing power and relatively elastic demand because of price sensitivities) and in favour of the rich (who drive cars and are worried about fuel emissions). P47 Cargill is among the companies that have been identified as having contributed to the destruction of forests in the production of soybean and other commodities. ... According to Greenpeace International, with the completion of this facility, land prices for the production of soybeans soared and the rate of deforestation accelerated. ... In 2006, however, following sustained pressure from Greenpeace, Cargill196 and other soy processors adopted a ‘Soy Moratorium’. P47 ... ‘mega-farmers’ such as El Tejar, the world’s largest farm operator. P48 Financialization : "Somehow the very term ‘financialization’, hard to understand and hard to explain, captures something of how remote the world of high commodity finance is from the reality of the vast majority of those who earn their living from agriculture, particularly those in the developing world." P48 The reviews of foreign investment in land continue to be overwhelmingly negative, summed up at recent academic conferences201 and in the press.202 There is some potential for positive outcomes, but little seems to be realized. P49 UNCTAD and UNAC " At the multilateral level, this trend towards increased private sector activity and away from state control was encouraged and reinforced by the Uruguay Round Agreements. TRIPS, for example, transformed multinational capital’s interest – and possible profits – in the seed sector, while the abolition of variable levies and quantitative import restrictions made the exporters’ business more predictable. The conditionalities imposed by structural adjustment policies and successor World Bank and IMF lending policies, as well as donor conditions on official development assistance (ODA), also underlay the policy shift. The international donor community encouraged developing countries to focus on exports, which for many meant agricultural commodity exports. Less discussed, but a necessary corollary of this policy under the Uruguay Round framework, was increased reliance on imports as well. The Uruguay Round agreement bound all but least developed countries (LDCs) to reduce their tariffs, and even LDCs were required to bind their tariffs to prevent any increase in the future. The growth in trade, both in imports and exports, created new opportunities for the ABCDs to expand." P50 **In 2000, developing countries shifted as a group from being net food exporters to net food importers. p50 the 1996 Farm Bill in the USA and the 1992 McSharry reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in the EU) reflected a strong promotion of the idea that what was good for the ABCDs was good for world agriculture. P51 " The companies that attracted the most attention at this point (in the early 2000s) were the retailers – Wal-Mart, Carrefour, Ahold, and Tesco. The dramatic expansion and consolidation in the retailing of food was at the forefront of a transformation not just in where consumers bought food, but also what kind of food they bought. The shift brought globalized food systems into many developing countries, where, until then, global commodity markets and local food markets had co-existed, albeit uneasily, in largely separate realms." P51 John Ruggie A second change is the move away from spot prices at different stages of the value chain to vertical integration with contracted producers. This plays directly into the interests of larger consolidated firms such as the ABCDs because it makes competition difficult for any smaller firm that specializes in one part of the value chain. It also reduces price discovery (see Part 1) and makes it harder to control the potential abuse of practices such as transfer pricing (see section below on transfer pricing). Open price discovery is a fundamental pre-condition for open markets. The third change is a move away from local sourcing to using national, regional, and global networks. p51 **Among the UN agencies, UNEP, UNCTAD, FAO, IFAD, IFPRI, and others have looked at the problems, as did the 2008 World Development Report (WDR) on agriculture. P52 ** effect on women** The systematic discrimination against girls and women in education, access to credit, access to extension services, and access to employment (especially at equal wages) all work against women’s ability to take advantage of new opportunities. P52 Another dynamic effect is to change diets, a process that is termed ‘the nutrition transition’ in much of the literature. As countries industrialize, a significant share of the population moves away from traditional diets to eat more meat, more fats and sugars, and more processed foods, in general. P52 The literature that documents the changes in food systems allows some tentative conclusions to be drawn on the role and implications for the ABCD companies, but little deals explicitly, or even extensively, with the ABCDs. P52 Genetically engineered : The ABCDs have lobbied hard, and quite openly, against any attempt to segregate GE from non-GE crops, insisting that they cannot afford the special handling required. P54 Transfer Pricing : There are many definitions of transfer pricing. The simplest is ‘the price at which one unit of a firm sells goods or services to another unit of the same firm’. P54 Article 9 of the OECD Model Tax Convention states: ‘[Where] conditions are made or imposed between the two [associated] enterprises in their commercial or financial relations which differ from those which would be made between independent enterprises, then any profits which would, but for those conditions, have accrued to one of the enterprises, but, by reason of those conditions, have not so accrued, may be included in the profits of that enterprise and taxed accordingly.’ P54 Ricardo Echegaray : ‘“Until 2007 ... Bunge paid about $100m in corporate income tax in Argentina a year. Then it decided to set up an office in the tax-free zone of Uruguay’s [capital] Montevideo. From that date, it suddenly declared no gains in Argentina. We cross-checked with Uruguay and we found they had not exported anything from Montevideo and had almost no staff there.” [...] Echegaray ... said he had evidence that all four companies had submitted false declarations of sales and routed profits through tax havens or their headquarters in contravention of Argentinean tax law. In addition, he said, they had declared excessive costs in Argentina to reduce taxable profits there. He also accused them of using phantom companies, on occasion, to buy grain’.232 p55 ...developing countries today account for 47 per cent of all imports and more than half of all exports. The ABCDs have positioned themselves already for this change and are important players in Brazil, China, India, and other emerging economies. P56 ** ...are we running out of the natural resources we need to grow enough food? Is industrial agriculture too wasteful and too polluting, or is it the only way to ensure an adequate food supply? Can global markets ensure food security, or must local food production dominate? Smallholders grow most of the world’s food – how can they be given more political voice in deciding food-related policies? And, reappearing for the first time since the 1970s in a more mainstream way: do global grain traders (and the multinationals they work with, from Monsanto and Syngenta to Wal-Mart and Carrefour) have too much power? P56 While volatile prices come with good profits for the traders, they have also brought governments’ attention back to agriculture, in some cases dramatically, as higher prices have led to riots in the streets of more than 30 countries. P56 ... food aid caught up in regulations that made it more or less impossible for anyone but a US-based multinational to supply the contracts). P56 ...countries such as Saudi Arabia stocking food rather than relying on the world market for supplies as and when they need them, poorer countries understandably feel pressured to build reserves of their own too. P56 ** High Level Panel of Experts (HLPE)** Google **World Food Programme (WFP) ...it is clear that the 2007–08 crisis severely tested governments’ confidence in world markets. This was particularly true among the most vulnerable countries, but also among some of the middle-income and rich importers, who seem to have decided that they cannot rely on commercial sales when need arises, and instead are banking food (and future food through land lease deals). P57 ** International Food and Agricultural Trade Policy Council (IPC) - look into ** International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD) - look into ...there is a need to manage demand given the planet’s finite resource base. The notion of managing demand is alien to free-market economics – price should be left to manage demand, rising when supply falls short so as to cut off demand. But there are obvious limits to this logic in relation to food: governments have an obligation to ensure access to food based on need, not demand. P58 The logic of trader thinking and argument is too seldom challenged, but food security is too precious to be left to the private sector. In making this argument, NGOs can help reclaim a larger place for the public interest in the complex world of financialized commodity production and trade. P58

0 notes

Text

Proposed title: Financialization of Agribusiness: Responsibility and Sustainability in Transnational Corporations.

Dissertation Proposal Form 2015/16

Department of Management

Student Name: Kieghley H Allen

Programme: Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability

Details of Research

2. Introduction:

“…Farming was discovered primarily to satisfy one’s own hunger and was not meant to serve the markets.”

Vijay Jardhari,

Save the Seeds movement, Garhwal India

Culture derives from the Latin cultura meaning ‘to cultivate’. The nurture and dedication that we must bestow on a harvest to allow it to fully flourish, is akin to the nurture and dedication it takes for the eudaemonia of a society. Just as a culture grows better without tyranny, so crops must be nurtured and protected from the tyranny of price (Clarke & Clegg, 2000: 25). Financialization of agriculture is the current manifestation of many transnational corporations preoccupation with price. Costas Lapavistsas of SOAS defines financialization as ‘Profiting Without Producing’ (2013). This has caused a detached and systematic approach to what was previously integrated and responsive agronomics. The degrees of separation between consumers and farmers have been increasing. Not only by miles of geography, but also by the quantity of mediators between farm and fork (Cragg & McNamara, 2014). The supply chain includes financers, landowners, farmers, labourers, biotech companies, patenting companies, insurance services, wholesalers, food processors, supermarkets and fast food chains. Each link is a financial opportunity open to exploitation, and an increase in the links allows an increase in the dispersion of responsibility (Fama, E and Jensen, M, 1983). The purpose of Corporate Responsibility and Sustainability is to protect stakeholders (including the environment and other species) while maintaining profit to shareholders (Freidman). The CSR of agribusiness is unique, as unlike many other industries, every single human on the planet is a stakeholder (Jones&Nisbet, 2011 : 2). We all must eat.

The commodification of human necessities will always be a controversial subject. Indeed, land grabbing is an on-going issue, which frequently involves transnational corporations. Conversely, the case of Hardin’s tragedy of the commons presents a sound argument for formulaic and corporate approaches to agriculture. While land grabbing is a pejorative term, some researchers such as McMichael condone ‘land grabbing’ as part of logical agri-economic plan (Russi, 2013:91). Due to such quagmires, the need for ecological stewardship has never been so essential (Russi, 2013:101).

This paper seeks to explore the divergence of commodification of food from a simple resolution to the lack of coincidence of wants, to the present manifestation of `financialization’. In 2006, the Organisation of American States wrote that nowhere else in the public domain did there exist literature which correlated ‘sustainable agriculture, CSR & the private sector of financial services’. In the ten years since, though there has been an increased interest and generation of

such papers, there is much left to be said and researched. Particularly, as this multidisciplinary subject matter is always changing. This paper seeks to further explore, evaluate and where possible, unify the aims of CSR with regard to financers, supermarkets, consumers and farmers. An aspect which I also hope to contribute to this subject area is that of the consumer perspective. The consumer comprehension and engagement with food is still underrepresented in much of the relevant literature. As drivers of change, the consumer is a significant variable regarding the emergence of financialization.

3. Preliminary literature review

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business–to use it resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud”

- Milton Friedman

As the dissertation will straddle at least three subject areas; CSR, Economics and Agriculture, I will attempt to maintain approximately 50% economics (financialization), 25% CSR and 25% Agriculture. The paper will be weighted to Economics due to the subject’s encyclopaedic properties, which is often inclusive of the latter topics. Furthermore, ‘Economics’ comes from the ancient Greek ‘rules of the house’ – so this will allow for structure, and serve as a central point of reference to return back to.

International Political Economics frequently refers to standard economical stages which ‘developing’ countries must pass through. This is the assumed method of meeting the position of their developed core piers. Agriculture has therefore experienced encouragement to participate in technical and biological modernization in many areas. This modernization has been widely welcomed by both the farming and finance sector. However, the contrasting Dependency Theory argues that a delay in development of the global south is not due to the extent in which the periphery has yet to assimilate with the global economy core, but rather the way it is has been assimilated. “Corporations have come to play a key role in the setting of rules and regulations that govern the global agrifood system” (Clapp & Fuchs 2009:285) As per the dependency theory, developing agribusiness has in some areas been coerced into following leading producers against its better judgement. In some instances farmers have actually been paid to produce less food (Roberts,2008:27). This has caused instances of mal-correlations between finance and agriculture. As finance handles theoretical and man-made commodities on trading floors, agriculture handles physical and natural elements in the field. Understandably the synthesis between these two very different sectors is imperfect.

As both Hayek and Russi (2013:52) outlined, a detrimental consequence of such profiteering is that pseudo-signals are, and have been, sent from the financial sector, which in turn causes incorrect stimulation to farmers and food manufacturers. These false incentives contribute to detrimental consequences, for instance the 2008 food crisis. Disincentives have also occurred in the form of food ‘dumping’ in the global south to protect global north profit levels (Russi, 2013 : 84).

Before financialization has any effect on the purchase of commodities, it first influences the research and development of biotechnology. A professor of biology Nina Fendoroff was quoted in the Guardian Newspaper in 2011 outlining that “...environmentally benign crop protection strategies are used almost exclusively for the mega-crops that are profitable for biotech companies”. If human hunger, sustainability and responsibility to domestic farmers were the primary motive, then as head of FAO Louise Fresco outlined, biotechnology would be supporting the “five most important crops in semi-arid tropics – sorghum, millet, pigeon pea, chickpea and

groundnut” (2003). However it is the profitable ‘cash crops’, which have attracted the investment – corn, canola, cotton and soybeans. Agri-biotech companies also seek to pacify concerns regarding financialization and nutrition loss in the food supply chain by ‘repairing’ manufactured food with fortification and spray on flavour (Roberts 2008 : 45,46).

Externalities are frequently omitted from the price a customer pays. Though the produce sold at farmers markets may seem higher than supermarket prices, the accumulative purchases of ‘bad’ products can in real terms cost society more. Conversely, one cannot assume that the term organic is interchangeable with the word sustainable. Organic farming techniques can be more damaging to the environment than standard farming (Roberts 2008: 252-57), a reality which is not commonly known. These aspects provide further reasons to enlighten consumers and offer them a more transparent supply chain. Without consumers, there is no profit, and so less incentive for financialization.

4. Main Four Research Points:

i. How aware are consumers about the consequences of financialization within the food supply chain?

- Patenting of seeds - terminator seeds

- Monocultures and soil degradation

- An increase in the use of fossil fuel pesticides

- Human drug resistance due to antibiotics used in industrial cattle farming

- GMO’s fed to cattle, which are then consumed by people in the UK

- Run-off and pesticides into rivers, effecting biodiversity – bees.

- Substitutionsim

- Bonded labour

ii. What are transnational corporations/supermarkets doing to help farmers ensure sustainability? (CSR)

- Cover crops for monocultures

- Reduction of drone pesticides

- Enabling Fair-trade prices / Living wage for domestic farmers

- Ceasing the cancellation of orders at harvest point

- Seed banking

- DNA Barcoding

- Ending bonded labour – chain transparency

- Community Supported Agriculture

iii. How are financiers helping / hindering Farmers, and what is their code of ethics / social contract?

- Precision agriculture

- Contango

- Reduction of land grabbing

- Financial derivatives

- Clarity on ‘fair trade’ agreements.

- Involvement with GATT’s, TRIPS and WTO agreements.

iiii. What can farmers do to prevent further exploitation?

- Whose interests are being served by the implementation of precision livestock farming?

- NATI

- Agrarian Policies

5. Proposed research method(s):

I intend to use a combination of both broad quantitative research and narrow qualitative research. As both are imperfect methods of exploration it is hoped that a combination of the two will allow a more authentic representation of the topic. All methods will be preceded with a pilot study.

Interviews: Sample of financiers, corporations, farmers and consumers. With consumers I would like to interview people both at prominent supermarkets, general shops and also independent farmers markets. I will study the interviews and omit any words with dual meaning from consideration to reduce misinterpretation. Applying dialectical phenomenology whereby “the researcher…analyzes the data by reducing the information to significant statements or quotes and combines the statements into themes... an overall essence of the experience” (Creswell, 2007, p. 60)

Online Surveys: A large qualitative (categorical) random survey with one or two descriptive questions to explore the general knowledge of a public cross section. Simple, limited Q’s. The anonymity allows for honesty. Questions will be balanced and not suggest any preferential answer.

Existing data / Archival Research: Public service departments have a wide source of data online, which may be used in conjunction with SPSS to illustrate any patterns and illuminate any gaps. This is in line with Karl Poppers - falsification and reproducibility which is not so efficiently possible with interview research interpretations.

6. Ethical issues:

Having watched many food supply chain documentaries featuring interviews, it is evident this topic is very emotive for most people. Farmers are often afraid to express their opinion regarding negotiations and frequently feel overwhelmed by their circumstances. Consumers are intentionally bamboozled by advertising and ‘super food’ propaganda. Those in the finance sector find themselves restricted by confidentiality agreements. All involved may discover information that influences their lifestyle choices, indirectly causing participants to wish to follow wider questioning and potentially sense anger when they discover things they feel they were mislead about. Therefore suitable provisions must be made. For instance a list of books, contacts and websites where participants may find further information should they need.

I must be conscious of the dual role problem and maintain objectivity using pre-prepared and approved questions. It is also contentious to interview those who may feel obliged to participate due to social dynamics, for instance junior colleagues. An existing relationship may also be counterproductive as individuals are often people pleasers, and so being aware of my chosen degree, may wish to appeal to particular ideologies. This would compromise their happiness, and so ethics, of participants and also compromise authentic results.

7. Timetable/plan for the research - available on request.

8. References:

Aguinis, H & Glavas, A (March 1, 2012). What We Know and Don't Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. GB: Journal of Management.

Clapp, J & Fuchs, D (2009). Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance. . Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Cragg, T and McNamara, T . (June 02 2014). “Known Unknowns” in Global Supply Chains”. Available: http://www.scmr.com/article/known_unknowns_in_global_supply_chains. Last accessed 5th Feb 2016.

Creswell, J. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. p60

F.A.Hayek ( 15 May 2009). The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fama, E and Jensen, M. Separation of Ownership and Control. The Journal of Law & Economics, Vol. 26, No. 2, Corporations and Private Property: A Conference Sponsored by the Hoover Institution (Jun., 1983), pp. 301-325

John Ganzi (2006). Sustainable Agriculture, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) & The Private Sector of the Financial Services Industry. USA: Organization of American States,

Jones, B & Nisbet, P (2011) Shareholder value versus stakeholder values: CSR and financialization in global food firms Socioecon Rev (2011) 9 (2): 287-314 first published online January 24, 2011 p2, 3, (LME v CME CSR) (p301 re: labour ...believes not enough focus on labour force CSR)

Lapavitsas, C. (5 Nov. 2013). Profiting without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All. UK: Verso Books.

Luigi Russi (27 March 2013). Hungry Capital: The Financalization of Food. UK: Zero Books.p91,93

Miller, H. (2011). How we Engineered the Food Crisis. The Guardian. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cifamerica/2011/mar/20/food-farming Accessed 5th Feb 2016

Roberts, P. (2008). The End of Food: The Coming Crisis in the World Food Industry. Great Britain: Bloomsbury. P23

Thomas, C. (Editor) - Clarke & Clegg, Gladwin et al (12 Aug 2004).Theories of Corporate Governance : The Philosophical Foundations of Corporate Governance. UK: Taylor & Francis Ltd. p25.

#proposal#financialization#agriculture#economics#business#politics#agribusiness#foodsupply#worldhunger#stuffedandthestarved

0 notes

Text

Crib Notes : Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE YALE UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER 14-15, 2013 - Financializa on, Distance and Global Food Polics, Jennifer Clapp

a) increased the number of the number and type of actors involved in global agrifood commodity chains and b) abstracted food from its physical form into highly complex agricultural commodity derivatives. P1

... distancing associated with financialization means that the role that financial actors play in fuelling those problems is not always transparent. This lack of transparency about which actors are involved in driving these trends creates space for competing narratives—often advanced by the financial actors themselves—that point to other explanations for negative social and environmental outcomes. P2

** Financialization is widely seen to be a response to the exhaustion of the Fordist economic growth model. p3

financial speculation on agricultural commodity futures markets as one of the contributing causes of those price trends (Clapp 2009; Mittal 2009; Ghosh 2010). P3

several scholars have sought to explain the rise of financialization in the food sector as part of the broader trend toward a finance-led capitalism within the corporate food regime (Burch and Lawrence 2009; McMichael 2012). P3

Princen shows that distance in global commodity chains can occur along several dimensions, including geography (physical distance), culture (knowledge about the conditions of production), bargaining power (ability to drive decisions) and agency (the number of middlepersons in a commodity chain) (Princen 2002). Kneen notes that technological change also expands distance by separating raw food from the final product (Kneen 1995). P4

Environmental problems can then be easily displaced and consumers are left largely unaware of the full ecological and social consequences of their own consumption (Princen 1997; 2001; 2002, p.108-115; Dauvergne 1997; 2008). P5

...the costs typically falling disproportionately on the world’s poor (Dauvergne 2008, p.10). P5

lack of clarity creates opportunities for competing narratives, or discourses, to emerge that seek to explain the negative outcomes in ways that portray financial actors as providers of solutions rather than sources of problems. P6

The link between financial investors and agricultural commodity trade has existed for centuries (Bryan and Rafferty 2006). Futures exchanges for agricultural commodities were established in London, for example, in the 18th century. P6