#willow basketry

Text

my partner's granddad (his mom's dad) used to weave baskets for personal use and my mom-in-law still uses some of them, including this one which was completely destroyed at the top. cannot describe how honoured i was to be asked if i could restore it. also cannot describe the feeling of working on this - being able to use everything i know to take care of this heirloom and make it functional again - using my hands today where his hands once were to create something that would be used for decades to come- time is a spiral etc

#honestly don't think i've ever been prouder of any other basket ive made#basketry#willow basketry#2022#apart from the familial significance it was cool as fuck to be able to pool everything i know about basketry to make this both#as true to the original as possible but also actually tough and functional too#there will be a video about this on christmas :-)#also really cool that this man was actually a pretty good basket maker#like i spend a lot of time with this basket and she's a sturdy one

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Text

Modern farmers and landowners, however, are prejudiced against scrub because it is considered unproductive. As a result it has been almost entirely eradicated from Britain. Scrubland is almost ubiquitously described as wasteland. It was not always so. In medieval times, scrub species were highly valued, and scrub was anything but a dirty name. The iron-rod stems of blackthorn were used for walking sticks and its fruit – sloes – for medicines and flavouring wine and gin. Brambles, like elder, produce edible berries that were also useful for dyes. Hawthorn makes good walking sticks, as well as tool handles, and was used for stock-proofing, and produces hawberries for preserves and sauces. Hazel was for hurdles, thatching spars, basketry, furniture and charcoal; willow for charcoal-making and basketry, cricket bats and medicine. Charcoal from alder and dogwood made gunpowder. Broom, of course, made excellent brooms. Juniper was for smoking meats and making pencils, its berries for distilling oil, and flavouring game and gin. Spindle was for skewers, toothpicks and baskets. Wych elm made bows, furniture and threshing floors. Birch provided cotton reels and bobbins, firewood, brooms and roofing thatch; its bark was for waterproofing and tanning. Birch wine, fermented from sap, was used as medicine and young birch leaves were a diuretic. From the dog rose came rosehips – which we now know are exceptionally high in vitamin C – for syrups, sauces and jellies. Gorse – known as ‘furze’ in Sussex – was fodder for animals and fuel for kilns and ovens. A buffer of thorny scrub was often encouraged around woodland to prevent the ingress of grazing animals. Place names like Thorndon, Thornden, Thornbury, Haslemere, Hazeldon, Spindleton, Hathern (hawthorn), Hatherdene, Brambleton, Barnham Broom, Broomhill, Broompark, pepper the map of Britain. Our own field names at Knepp recall the days when scrub was an asset – Benton’s Gorse, Broomers Corner, Broom Field, High Reeds, Cooper Reeds, Faggot Stack Plat, Bramble Field, Rushett’s, Rushall Field, Little Thornhill, Great Thornhill, Stub Mead, Barcover Furzefield, Swallows Furzefield, Coates’ Furzefield, Greenstreet Furzefield, Constable’s Furze, Pollardshill Furze, Old Furze Field, Furzefield Plat, Great Furzefield and lots of Little Furzefields.

Isabella Tree, Wilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

So on dendryte's suggestion, I read a paper called "Feed your friends: do plant exudates shape the root microbiome?", and it is awesome and filled with ideas that were new to me, and all in all was very exciting. Like, I didn't even know about/remember border cells, and they apparently do a whole lot! I'm back from work now, so now I'm going to share the Questions I have, and am going to spend the weekend looking for sources on:

1. As crop rotation was developed for a tilled, monoculture system as a way to address the disease issues that pop up in such a system, is crop rotation actually beneficial in a no-till, truly polyculture setting where care is taken to support mycorrhizae?

As we know know that plants alter the population of bacteria in the soil, and that these population compositions differ between plant species, is it possible that there might be some benefits to planting the same crop in the same location if you're not disrupting microbe populations through tilling?

2. Since we know that applications of nitrogen can cause plants to kick out their symbiotic fungal partners, increasing their vulnerability to pathogenic fungi & drought, might it be better to place fertilizer outside of the root zone so as to force the plant to use the mycelium to get at it?

How far can mycorrhizal networks transport mineral nutrients? Are they capable of transporting all the mineral nutrients plants need? In other words, can I make a compost pile in the middle of the garden and be lazy and depend on the fungal network to distribute the goods?

3. How deep can fungal hyphe go? In other words, in areas with shallow wells, and thus fairly shallow water tables, can we encourage mycorrhizae enough to be able to depend on them for irrigation?

4. For folks on city water, does the chlorine effect plants' microbiome both above and below ground?

5. When do plants start producing exudates? If you had soil from around actively growing plants of the same species you're sowing, could the bacteria and fungi play a role in early seedling vigor & health?

6. Has anyone directly compared the micronutrient profiles of the same crop grown in organic but tilled settings against those grown in no-till, mycorrhizae-friendly settings?

7. Since we know that larger molecules, such as sugar, can be transported across fungal networks between different species (Suzanne Simard is where I first food this info) , have we checked for other compounds created by plants? Say, compounds used by plants to protect against insect herbivory?

8. Since we know blueberries use ericoid mycorrhizae rather than endo- or ectomycorrhizae (which are the two types used by most plants), but gaultheria (salal & winter green) use both ericoid & ectomycorrhizae, and alder uses both endo & ectomycorrhizae (and fix nitrogen too!), and clover use endomycorrhizae, might blueberries be more productive if there's a nearby hedge of salal/wintergreen, alder, and clover? Willows and aspens also both use endo & ecto, so they could be included, and the trees could also be coppiced for firewood or basketry supplies.

I'm going to spend some time this weekend reading research papers. If anyone happens to know any that address these (or related questions), please send them my way!

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Julia Kane. April 27, 2023. On an overcast Saturday in March, Serina Fast Horse stands in a ring of freshly planted, 12-foot-tall willow cuttings. Soft white buds are just beginning to emerge from their gray stems.

Easing the tips of the willows toward the center of the circle, Fast Horse holds them in place while another volunteer ties them together with twine.

Fast Horse and about three dozen others have gathered at Shwakuk Wetland, five acres of land situated between a residential neighborhood and a freight warehouse in north Portland, just south of Columbia Edgewater Country Club.

In time, the trees they plant and gently shape will grow into a willow dome—a living structure people can gather around for ceremonies, educational programs or just to enjoy the space.

Shwakuk, which is pronounced “show-kayk” and means little frog in Chinook Wawa, is a unique site co-managed by the local Indigenous community and Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services.

When the city acquired the land in 2016, it was a pumpkin patch.

Since then, the team responsible for stewarding it has worked to restore the wetland. Now it’s used to to cultivate first foods, medicines and basketry plants.

It’s also reconnecting area residents with the land.

Fast Horse, who is Lakota and Blackfeet, serves as a community liaison on the Shwakuk project, bridging the gap between the local Indigenous community and city employees.

Since getting involved with the project, the 28-year-old Portlander has also gone on to found Kimímela Consulting. Her goal is to bring the Indigenous community into environmental decision-making processes at the city and state level.

“When we’re able to come together and uplift Indigenous knowledge—and learn from each other, too, because there are things from western science and ecology that are important for restoration—we can change these systems to be more regenerative,” says Fast Horse.

“Indigenizing” not “de-colonizing”

For Fast Horse, the choice to use the word Indigenize rather than decolonize is intentional.

“When we say Indigenize, it’s centering the Indigenous perspective and being forward-thinking instead of centering colonization and that experience,” she says.

In restoration work, the Indigenous perspective hasn’t often been taken into consideration.

“Our program has always used native plants, but the selection wasn’t necessarily based on the Indigenous communities’ needs or desires,” says Toby Query, a natural resource ecologist with Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services. “It was more about what would survive and what would fulfill our agency’s goals as far as shading the water, wildlife habitat and structure, and so forth.”

At Shawkuk, the Indigenous community put together a list of desired plants, which included first foods, medicines and plants used for traditional crafts.

That list has guided Query and the rest of the team involved in day-to-day restoration work at the site.

So far, they’ve had success at growing tule, a sedge used in basketry and canoe-making, along with yarrow, a medicinal plant, and camas, a plant with an edible, bulb-like root. They’ve also planted yampah, a wild carrot.

Instead of spraying herbicide, the restoration team uses vinyl from old billboards to block the sun and kill invasive grasses. Sometimes, they’ll braid invasive grasses around native plants, like yellow dock, horsetail and cattail, so that they stay low to the ground and do not choke out other plants.

“It takes a lot of effort to do it,” says Query, who has spent many hours braiding reed canarygrass alongside workers from Wisdom of the Elders, an Indigenous-led group. “While we were doing it we were enjoying conversation, and it was kind of a healing process.”

Query has implemented many techniques he’s learned from the Indigenous community at the 20 or so sites he stewards across the city.

“It’s really informed what I plant, and how I take care of plants,” he says.

Tending parties, wild tea

Healing is a critical element of Indigenizing restoration work.

In fact, says Fast Horse, “my deepest wish for this work is to bring folks together and to heal our relationships to each other and to the earth.”

At Shwakuk, she’s brought people together by helping organize “tending parties” that attract members of the local Indigenous community, students from Portland State University, city employees and others.

The groups learn about a site, spend a few hours helping with a restoration project and gather for lunch.

Oftentimes, Judy BlueHorse Skelton, an assistant professor at Portland State University who has helped lead the Shwakuk restoration, will make tea for everyone.

She makes the tea using a sprig of Doug fir gathered onsite, and sometimes rosehips, Oregon grape and western redcedar.

“We’re taught that to sip tea together is to become a relative, or to form a relationship,” says BlueHorse Skelton, who is Nez Perce and Cherokee. “It’s also deepening our intimate relationship with the plant world. It’s a big part of Indigenous traditional ecological and cultural knowledge, and it’s embedded in the work that we’re all doing.”

Intern to owner

Restoring Shwakuk was pivotal for Fast Horse, who first got involved with the project as an intern with Environmental Services.

“I was able to be an internal advocate to make sure what the community was saying was being upheld in a really meaningful way,” says Fast Horse. “I would be in these internal meetings, and so that perspective got woven throughout the process.”

In those meetings, the impact that she could have as a community liaison became clear.

From Query’s point of view: “To have somebody that has an Indigenous perspective, but is also willing to be part of the agency side of things, and to be able to walk between those two cultures has been really important.”

Fast Horse began giving presentations about lessons learned from Shwakuk and found that other city agencies and organizations wanted Indigenous input on their projects, too.

Portland has recently become more proactive about reaching out to the Indigenous community. The city hired its first full-time tribal relations director, Laura John, in 2017—a move BlueHorse Skelton says has been “immensely transformative.”

Two years ago, Fast Horse founded her own company, Kimímela Consulting, based in Milwaukie, Ore. She’s continued to act as a liaison between the Indigenous community and various agencies and organizations.

Most of her work has to do with land restoration, but she’s also working with Portland State University to rename a street. The campus’ Native American Student and Community Center is currently located on a street named after President Andrew Jackson, known for enforcing the genocidal Indian Removal Act of 1830.

“She’s been providing a voice and venue for the Indigenous community, including students and folks across all agencies, to get involved—including just the average community member who may not have a voice,” says BlueHorse Skelton.

A reconnected future

According to BlueHorse Skelton, the work that Fast Horse is doing to ensure the Indigenous community is part of decision-making processes is critical.

“When cities look, today, at how to heal, how to begin to restore, how to protect what’s left,” says BlueHorse Skelton, “we have to be part of it.”

She sees Fast Horse as the first of a new, emerging generation of Indigenous leaders in the region.

“As some of us become elders, who carries that work forward?” BlueHorse Skelton asks. “That’s Serina.”

“A lot of times people put us in the past, and that’s a huge misconception,” says Fast Horse. “We’ve always been adaptable people. We’re not trying to revert back to anything, we’re going into the future.

“We’re all interconnected in this physical and spiritual plane. With Indigenous knowledge, we can reconnect to that and live in a way that is more in line with natural systems that are regenerative and life-giving.”

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

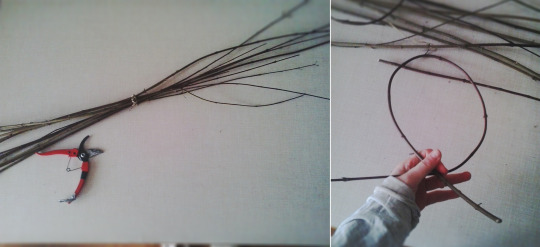

How to make natural wreaths for decoration!

It's easy, doesn't take long, and you don't need that much skill! I didn't actively try to learn this, but picked it up accidentally while learning basketry; the core of the thing is, that you need to go and harvest something bendy in nature. And then you need to wrap that bendy thing around itself until it makes a round circle and you're done. You could do it with trial and error alone.

The bendy thing can be a young fruit tree branch, some ivy vines, blackberry brambles (you can take off the thorns if you run it thru some old denim!), willow branches, young peach branches, some bush branches, a lot of things work! You can check if the thing is bendy enough by bending it in circle, like in the picture below!

If you can do this with a branch, it can make a wreath. If it snaps, not bendy enough! I'm using some red branches that I don't know the name of, but they're bendy enough. Here's how you start:

At the start you’re supposed to feel dejected and confused: the branch wrapped around itself is not making a hoop (unless you’re trying to make a really small one! Then you can manage to make a circle even with just one). There’s always some point being pulled by the thicker edge of the branch, making it wonky. But not to worry!

As you keep adding branches, you keep adding strength and tension. Only thingy you might want to watch out for, is to make sure you’re turning all of the branches the same way, but that’s only to make it prettier! Even if it’s going in all directions, it will still end up being a decent wreath.

When you’ve decided it’s thick enough, you can tuck in all of the edges between the branches, so they won’t be visible, and for the ones that are thick and can’t be neatly tucked in, you cut them off! And there you have a cool wreath base! Now time to decorate it:

Mine is a fall wreath! I picked up the most beautiful leaves outside, and putting them up on a wreath makes people not be upset that you just dragged in bunch of foliage inside. I used a corn husk cord to tie them up to the hoop, so it would be all natural materials.

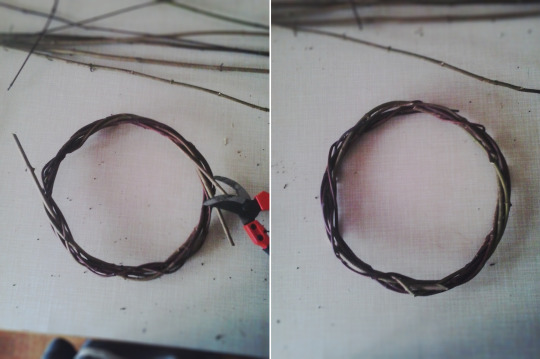

Now lets make one out of ivy:

Ivy is easier because it’s very bendy and pliable, and it’s not creating so much tension. You basically don’t have to do anything but keep wrapping it around itself:

I left one some leaves there for the end decoration, I thought it would look cool! But in the end I only kept the tiniest leaves, because I thought they were the cutest:

Here you can see me tucking in the end of the vine, so it would be held tightly inside and invisible from the outside. We have a little hoop!

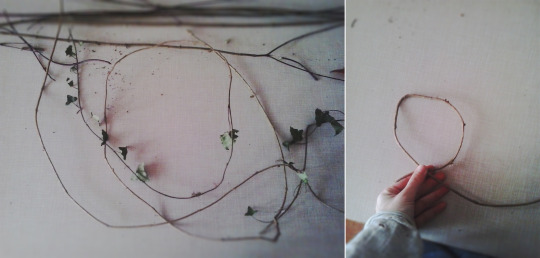

And to decorate it, I found a bunch of white sage outside, I thought it was super pretty and durable as a decoration, it will stay the same color even after it dries! I tied it up with a cord made out of dandelion stems, and then added two more ivy leaves, and a rosehip to make it festive. I didn’t think about it while doing it, but sage, ivy, and rosehip, are all powerful medicinal plants, so this might actually be a herbalist’s wreath.

Here’s two more wreaths I made using the exact same technique, just with a bit more materials:

The first one is red branches + ivy, the second one ivy + a cord I made out of corn husk, wrapped around the entire hoop. And here’s the two we just made, in better lightning:

If you keep adding more material in, you can make those thick wreaths that you can decorate with pine branches and add candles in, for horizontal use. Have fun!

#wreaths#diy#tutorial#natural decoration#winter wreath#winter solstice#holiday decorations#winter decoration#fall wreath#natural diy

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

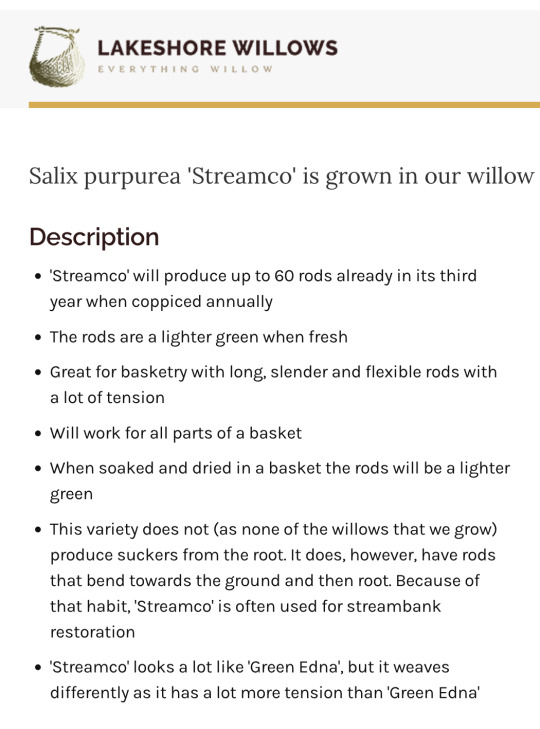

Willow

It’s time for us northern hemisphere folks to start thinking about spring planting, whether it’s imminent or still three months off. Aside from my curly willow, which is an ornamental cultivar that I want just for prettiness, I’m hoping to start some cuttings of the Streamco willow on a streambank that needs support. I tried this a year or two ago, but a small flood in the spring took my cuttings away before they could get firmly established.

This is a photo of one of the clumps we planted years ago in a spot where flooding can be an issue. Streamco willow is a dense, upright shrub instead of a tree. Those clumps are roughly 5 yards/meters high. I tried to look up the latin name and found this interesting site advertising the virtues of Streamco for basketry (@woodelf68 it’s like they heard you!).

https://www.lakeshorewillows.com/site/salix-purpurea-streamco

Side note: I love that there are people out there who know different cultivars (Green Edna!) by the unique characteristics they have for basketry.

#willow#salix#basket weaving#planting season#spring#tree planting#erosion#stream bank#environment#solarpunk

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cut down a sapling for more spindle wood (its in an area where the landscaper who does all the apartments around here will absolutely cut it down, so it was only a matter of time), but am finding it almost impossible to work with. Maybe it needs to dry for a little bit, idk shit abt woodworking.

But also, was walking to the one open store after work to get cigarettes last night and noticed what i'm 99% sure is a willow tree ! Which is super exciting, need to look into the best time to cut and store some for basketry. Always wanted to work with willow, just havent seen any in a spot i could get it.

#spent like an hour getting the sapling up. was like chiseling away at the roots bc my saw is for fine work and kept getting clogged#am very tired. have work in 25 minutes and meant to make food but. oh god. so tired.#and lots of pain

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

365 Days of Writing Prompts: Day 7

Adjective: Hushed

Noun: Willow

Defintions for those who need/want them:

Hushed: having a calm and still silence; (of a voice or conversation) quiet and serious

Willow: a tree or shrub of temperate climates that typically has narrow leaves, bears catkins, and grows near water, and its pliant branches yield osiers for basketry, and its wood has various uses; a machine with revolving spikes used for cleaning cotton, wool, or other fibers

#yay ive done a whole week of these#im honestly proud of myself and looking forward to keeping this up as long as i can#thanks for reading#writing#writer#creative writing#writing prompt#writeblr#trying to be a writeblr at least

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

vessels 🕯️

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Environmental Impact of Pyrolysium

The ancient Greeks were the first to use pyrolysis to dispose of the bodies of dead people. It is the process of burning a body and using it as biochar for a variety of uses. However, in many places today, the term is more commonly used to refer to the disposal of human remains. Although this process is not terribly efficient, it can save the environment from a large number of negative consequences.

The use of Pyrolysium as a biodegradable coffin is increasing. It can be environmentally friendly, using tree-sparing cardboard boxes and soft winding sheets to bury the dead. The ashes are then buried or scattered at sea. Some parts of China even allow pyrolysis for donor programs, making this a more environmentally-friendly option. Regardless of the environmental impact, pyrolysis is the greenest option for those who don't wish to be buried.

Biodegradable coffins can be made from wood or cardboard. They can be made out of soft winding sheets or papier-mache. They are both environmentally friendly and can be recycled easily. Some people, however, do not wish to make use of biodegradable coffins. They prefer cremation because it requires the least amount of energy. Additionally, cremation is a more sustainable option. Some universities have donor programs where the ashes of those who passed away do not want to remain in the cemetery.

Cremation is a greener option. It involves placing the dead body into a steel tank and burning it. The process produces bone fragments that can be placed in urns. The liquid is then drained down the drain. This greener option is now popular in several states. It is a much more environmentally-friendly choice than traditional burial and is used in some university organ donor programs. The practice is considered to be "green" and is increasingly popular.

The toxicity of Pyrolysium is a major cause for concern. The chemical is found in soil and water, and is considered to be highly flammable. This is why it is essential to prevent pollution. If you're concerned about the safety of the environment, a high level of pyrolysis is a big concern. The risk is too great to ignore. The dangers of contaminated sewage are far greater than any other types of contamination.

It is possible to get rid of Pyrolysium by cremation. This is a greener alternative to cremation and uses the ashes to bury the dead. This process also uses less energy than traditional cremation, and the ashes can be recycled. In addition to this, it's eco-friendly. The process is also more environmentally friendly than other methods, which makes it an attractive option for funeral homes.

Cremation is a controversial procedure. It involves burning the body to produce biodegradable bone fragments. It is an environmentally friendly method of burial, but it is still not an eco-friendly option. Some areas, such as Beijing, ban cremation, causing smog, are also illegal. This is a very common procedure, but it can be costly. Besides, it's not environmentally friendly. Some cities have banned the process.

Cremation involves the burning of the dead body and leaving the ashes in an urn. It uses a large amount of natural gas, sulfur, and carbon dioxide. It is environmentally friendly compared to most funeral methods. It is also more sustainable than cremation. It is the preferred method in many parts of the world. In China, it is the only method used for organ donation. It is used at hospitals and funeral services.

Cremation is an environmentally responsible method for the disposal of human remains. The body is burned into bone fragments and the ashes are then scattered around the country. The process is a green alternative and does not involve hazardous chemicals. The body is cremated using a biodegradable coffin and willow basketry. This is an ecological option as the body does not need to be dumped. In addition, it is environmentally friendly as well.

Cremation is the most ecological and eco-friendly option. Instead of burying a body, it can be burned and the ashes are subsequently scattered. In fact, this method is also environmentally friendly compared to other methods. It also requires minimal effort on the part of the family and is more sustainable than most. In China, the cremation process is done in a laboratory. This method is known for being environmentally friendly.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Basketry - 2323 Designs

23:23 Designs is associated with various clusters of Basketry Pan India.

The Natural Fibers we work with 12 natural fibers in various techniques o basketry and weaving , These are

Bamboo, Sabai Grass, Banana Fiber, Kauna Grass, Rattan, Willow Wicker, Moonj, Sital Pati, Water Hyacinth, Madur, Screw Pine , Palm Leaf and much more….Interestingly we also support Artisan groups using basketry techniques in Paper and Recycled Plastics. Contact us at [email protected] for Corporate and Customized Orders.

These handcrafted home decor items can create a cozy & sustainable corner in your homes. Each piece is an antique showpiece for home decor.

Basketry, art and craft of making interwoven & Interlaced objects, usually containers, from flexible vegetable fibres, such as twigs, grasses, osiers, bamboo, and rushes, or from plastic or other synthetic materials. The containers made by this method are called baskets, and can be designed with decorative motifs of any other art form – geometrics or organic forms.

MATERIALS

Materials are chosen with a view toward achieving certain aesthetic goals; conversely, these aesthetic goals are limited by the materials available to the basket maker. The effects most commonly sought in a finished product are delicacy and regularity of the threads; a smooth, glossy surface or a dull, rough surface; and colour, whether natural or dyed. Striking effects can be achieved from the contrast between threads that are light and dark, broad and narrow, dull and shiny—contrasts that complement either the regularity or the decorative motifs obtained by the intricate work of plaiting.

Coiled construction

The distinctive feature of this type of basketry is its foundation, which is made up of a single element, or standard, that is wound in a continuous spiral around itself. The coils are kept in place by the thread, the work being done stitch by stitch and coil by coil. Variations within this type are defined by the method of sewing, as well as by the nature of the coil, which largely determines the type of stitch.

To know more:

https://2323designs.in/blogs/craft/basketry

0 notes

Text

"With stagnant or slow-flowing fresh or brackish water, planting reeds on the waterline can protect riverbanks. However, this approach doesn’t work with saltwater, nor does it prevent damage from large waves. At least 400 years ago, the Dutch came up with a solution: the fascine mattress. A fascine mattress consists of thousands of fine twigs, mainly from willow trees. These are woven together into a sturdy mat dropped at the bottom of a canal, estuary, or river. A fascine mattress can lay partly on the river-bank or dyke."

[...]

It’s not clear when exactly the Dutch started using fascine mattresses. The oldest image is a 1676 painting by Matthias Withoos, which illustrates the repair of a dyke. However, there are references to brushwood constructions in hydraulic engineering already in the sixteenth century. Many fascine mattresses remain functional today, centuries after their construction. Willow wood becomes rock-hard underwater and almost doesn’t deteriorate. Research in the late 1960s showed that most fascine mattresses submerged for more than 100 years — some dating from the early 1820s — remained intact.

"We don’t know how many fascine mattresses are still performing their duties at the bottom of the Dutch waters, but they are basically everywhere. Most data is available from the period following World War II when the Dutch used the technology on a large scale. In 1953, catastrophic flooding hit the Netherlands. That led to the Delta Works, a series of ambitious construction works to protect the land from the sea.

content://com.android.chrome.FileProvider/images/screenshot/16568411089121304492680.png

Image: Fascine mattresses in the biesbosch, 1968. Public Domain.

Fascine mattresses were an essential part of this plan. For example, between 1960 and 1966, the Dutch added 200,000 m2 of fascine mattresses in the Wadden area (a group of islands in the north). Between 1954 and 1967, during works on the rivers throughout the country, they sank 1,200,000 m2 fascine mattresses to the bottom.

Making a fascine mattress was a craft that mainly involved knotting and braiding. In tidal areas, the Dutch braided fascine mattresses on mudflats that were dry at low tide. This meant that the work had to happen quickly. When the high tide came in again, the structure started floating – and it had to be sturdy enough not to drift apart. Finishing the fascine mattress could happen during the next low tide or even while the structure was floating.

The craftsmen started weaving brushwood into bundles or strips called fascines (“wiepen” in Dutch). Fascines were up to 50m long, had a diameter of about 30-50 cm, and were tied together with thin twigs. The fascines served to build a lower framework, which formed the basis of the entire structure. The bundles were superimposed crosswise about a meter apart and secured with rope and a pole at the crossings.

On top of this framework came a 30-40 cm “filling” of two layers of brushwood across each other. In between these came a reed layer, which made the fascine mattress sand proof. Next, an upper framework of fascines was built, identical to the lower framework, on top of the “filling”. The men then lashed the whole thing to the posts. It took about six men to build 100m2 fascine mattress."

This entire article is super fascinating, didn't copy the rest-- worth clicking the link at the top of this post.

#weaving#copice#gardening#gardenibg tag because i mught use this in a garden lol#sea works#anyway im literally surrounded by these and i had no idea#basketry

0 notes

Photo

Twill twined water bottle

Willow shoots

Unknown Northern Paiute artisan, Great Basin region, late 19th century

To help support the preservation of our collection click here.

#pacific grove#monterey#museum#collection#basketry#northern paiute#great basin#twill#twined#water bottle#willow shoots

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Willow by Jenny Crisp

Traditional Craft for Modern Living

This comprehensive well explained and beautifully illustrated book tells of the willow (salix) used for weaving. There are directions for items to make and examples of items I would love to own. I almost envy the author her three decades of creating wonderful items that people no doubt enjoy and cherish.

I have done basket weaving as a child but this is much different from what we did. I learned about willow and the techniques used to create and would like to someday try weaving with willow should I have the chance. I also have to say I thought about this as a potentially lost skill that with this book one could be able to create useful items should an apocalypse occur ;)

Thank you to NetGalley and Quarto Publishing-Jaqui Small for the ARC – This is my honest review.

4-5 Stars

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/38743290-willow

BLURB

As natural materials such as wood, leather, rattan and cork continue to be used in the home, handmade woven objects, from bread baskets and trays to stools and screens, are fast becoming the must-have accessories of the contemporary interior. Master basket maker and willow grower, Jenny Crisp, teaches you some of the key weaving techniques to make 20 simple willow projects without the need of complicated tools. Jenny’s approach is innovative and moves forward beyond the old patterns and boundaries, to allow the reader to make work that is fresh and for contemporary use.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

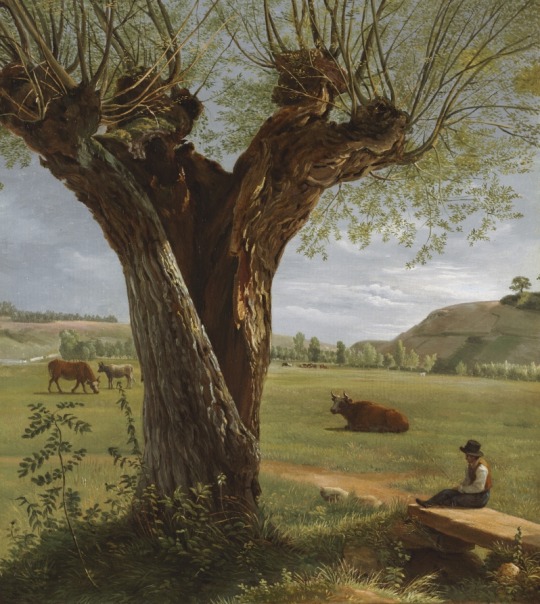

Pollard Willow, Pierre Jean Boquet , after 1804, Cleveland Museum of Art: Modern European Painting and Sculpture

Little is known about Boquet's life, and his artistic origins remain obscure. His style and technique suggest that he received formal training, but where and with whom is unclear. An inscription on a painting attributed to Boquet implies that he spent time in Rome, where he would have seen works by 17th-century French artists such as Claude Lorrain. This may explain the gentle, bucolic atmosphere and the warm, golden light in Pollard Willow, characteristics of which recall the paintings of Lorrain and his contemporaries. The severe pruning or pollarding of trees, especially willows, was a common practice before the Industrial Revolution (about 1750-1850). The procedure allowed the tree to produce large numbers of shoots, which were used in basketry, fence construction and as fodder for farm animals.

Size: Unframed: 29.6 x 26.8 cm (11 5/8 x 10 9/16 in.)

Medium: oil on paper, mounted on canvas

https://clevelandart.org/art/1980.237

40 notes

·

View notes