#their history shows what they can achieve when their views are aligned and balanced

Text

thinking about how the Sumeru Archon Quest can be read as a metaphor for Alhaitham and Kaveh's relationship and their progression and going crazy

Alhaitham is present during the quest, whereas Kaveh is not, and this causes Alhaitham to question why Kaveh was not present in saving Sumeru. Relating this to their thesis, although it made many bounds for Sumeru’s understanding of ancient languages and architecture which held promise for betterment of the future, it was abandoned before completion due to their clashing of views and personal attacks of each other. Alhaitham repeatedly questioning why Kaveh was missing hints that Kaveh should have been a part of the Archon-saving plan, in that, Kaveh was missing from the betterment of Sumeru. Once again, an opportunity passed by for them uniting for a mutually agreed cause. This is due to the dissonance between them and their lack of successful communication.

In the Archon Quest, Alhaitham is present, ready for reconciliation, to work together, whereas Kaveh is missing, unaware of the chance of reconciliation. Kaveh believes that Alhaitham deliberately stirred trouble in Sumeru, rather than saving it, due to his flawed perception of Alhaitham – just as he believes that Alhaitham wants something in return for allowing Kaveh to live in his house, rather than it being an invitation for reconciliation, due to his flawed perception of Alhaitham.

This, in turn, creates a space in the narrative for the two to join together of their own accord, however, the two need to be in the same mindset for reconciliation. As established in Kaveh's Hangout and A Parade of Providence, this can be brought about by the mutual understanding that their clashes do not stem from overall differences in thinking, but their way of communication. Rather than their relationship being based on the opposition of their thinking, it should be based upon the potential that can be borne from identifying good in the balancing of viewpoints – which their thesis had achieved.

Their development as individuals ultimately lies within the other as they possess what the other lacks in order to fully complete their understanding of each other, and themselves. Alhaitham is the grounding for Kaveh’s ideals and the push for him to prioritise himself in his pursuit for happiness for “all” (as established within a parade of providence), whereas Kaveh is the breach in Alhaitham’s rationality and allows him to understand the sensibility of others around him, enabling Alhaitham to possess an enhanced version of his truth.

(Update: For more analyses like this, the essay this is taken from is now uploaded! It can be accessed here and here as as a pdf <3)

#alhaitham#kaveh#haikaveh#kavetham#haikaveh meta#i love overthinking so much#but really kaveh being missing from the archon quest but being the Main Character of a parade of providence is so poignant#the first thing alhaitham does when kaveh returns is ask and then demand to know where kaveh was and what he was doing#and kaveh is convinced that alhaitham has done something nefarious in sumeru#and then in the cutscene afterwards alhaitham asks about kaveh’s whereabouts AGAIN#like what was all that about#if not to show that alhaitham believed that kaveh should have been a part of the narrative#but they are not on the same page!!!#their history shows what they can achieve when their views are aligned and balanced#i am BEGGING we get an instance like that again

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pagan Paths: Wicca

Wicca is the big granddaddy of neopagan religions. Most people who are familiar with modern paganism are specifically familiar with Wicca, and will probably assume that you are Wiccan if you tell them you identify as pagan. Thanks to pop culture and a handful of influential authors, Wicca has become the public face of modern paganism, for better or for worse.

Wicca is also one of the most accessible pagan religions, which is why I chose to begin our exploration of individual paths here. Known for its flexibility and openness, Wicca is about as beginner-friendly as it gets. While it definitely isn’t for everyone, it can be an excellent place to begin your pagan journey if you resonate with core Wiccan beliefs.

This post is not meant to be a complete introduction to Wicca. Instead, my goal here is to give you a taste of what Wiccans believe and do, so you can decide for yourself if further research would be worth your time. In that spirit, I provide book recommendations at the end of this post.

History and Background

Wicca was founded by Gerald Gardner, a British civil servant who developed an interest in the esoteric while living and working in Asia. Gardner claimed that, after returning to England, he was initiated into a coven of witches who taught him their craft. Eventually, he would leave this coven and start his own, at which point he began the work of bringing Wicca to the general public. In 1954, Garner published his book Witchcraft Today, which would have a great impact on the formation of Wicca, as would his 1959 book The Meaning of Witchcraft.

Gardner claimed that the rituals and teachings he received from his coven were incomplete — he attempted to fill in the gaps, which resulted in the creation of Wicca. Author Thea Sabin calls Wicca “a New Old Religion,” which is a good way to think about it. When Gardner wrote the first Wiccan Book of Shadows, he combined ancient and medieval folk practices from the British Isles with ceremonial magic dating back to the Renaissance and with Victorian occultism. These influences combined to create a thoroughly modern religion.

Wicca spread to the United States in the 1960s, at which time several new and completely American traditions were born. Some of these traditions are simply variations on Wicca, while others (like Feri and Reclaiming, which we’ll discuss in future posts) became unique, full-fledged spiritual systems in their own right. In America, Wicca collided with the counter-culture movement, and several activist groups began to combine the two. Wicca has continued to evolve through the decades, and is still changing and growing today.

There are two main “types” of Wicca which take very different approaches to the same deities and core concepts.

Traditional Wicca is Wicca that looks more or less like the practices of Gerald Gardner, Doreen Valiente, Alex Sanders, and other early Wiccan pioneers. Traditional Wiccans practice in ritual groups called covens. Rituals are typically highly formal and borrow heavily from ceremonial magic. Traditional Wicca is an initiatory tradition, which means that new members must be trained and formally inducted into the coven by existing members. This means that if you are interested in Traditional Wicca, you must find a coven or a mentor to train and initiate you. However, most covens do not place any limitations on who can join and be initiated, aside from being willing to learn.

Most Traditional Wiccan covens require initiates to swear an oath of secrecy, which keeps the coven’s central practices from being revealed to outsiders. However, there are traditional Wiccans who have gone public with their practice, such as the authors Janet and Stewart Farrar.

Eclectic Wicca is a solitary, non-initiatory form of Wicca, as made popular by author Scott Cunningham in his book Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner. Eclectic Wiccans are self-initiated and may practice alone or with a coven, though coven work will likely be less central in their practice. There are very few rules in Eclectic Wicca, and Wiccans who follow this path often incorporate elements from other spiritual traditions, such as historical pagan religions or modern energy healing. Because of this, there are a wide range of practices that fall under the “Eclectic Wicca” umbrella. Really, this label refers to anyone who considers themselves Wiccan, follows the Wiccan Rede (see below), and does not belong to a Traditional Wiccan coven. The majority of people who self-identify as Wiccan fall into this group.

Core Beliefs and Values

Thea Sabin says in her book Wicca For Beginners that Wicca is a religion with a lot of theology (study and discussion of the nature of the divine) and no dogma (rules imposed by religious structures). As a religion, it offers a lot of room for independence and exploration. This can be incredibly empowering to Wiccans, but it does mean that it’s kind of hard to make a list of things all Wiccans believe or do. However, we can look at some basic concepts that show up in some form in most Wiccan practices.

Virtually all Wiccans live by the Wiccan Rede. This moral statement, originally coined by Doreen Valiente, is often summarized with the phrase, “An’ it harm none, do what ye will.”

Different Wiccans interpret the Rede in slightly different ways. Most can agree on the “harm none” part. Wiccans strive not to cause unnecessary harm or discomfort to any living thing, including themselves. Some Wiccans also interpet the word “will” to be connected to our spiritual drive, the part of us that is constantly reaching for our higher purpose. When interpreted this way, the Rede not only encourages us not to cause harm, but also to live in alignment with our own divine Will.

Wiccans experience the divine as polarity. Wiccans believe that the all-encompassing divinity splits itself (or humans split it into) smaller aspects that we can relate to. The first division of deity is into complimentary opposites: positive and negative, light and dark, life and death, etc. These forces are not antagonistic, but are two halves of a harmonious whole. In Wicca, this polarity is usually embodied by the pairing of the God and Goddess (see below).

Wiccans experience the divine as immanent in daily life. In the words of author Deborah Lipp, “the sacredness of the human being is essential to Wicca.” Wiccans see the divine present in all people and all things. The idea that sacred energy infuses everything in existence is a fundamental part of the Wiccan worldview.

Wiccans believe nature is sacred. In the Wiccan worldview, the earth is a physical manifestation of the divine, particularly the Goddess. By attuning with nature and living in harmony with its cycles, Wiccans attune themselves with the divine. This means that taking care of nature is an important spiritual task for many Wiccans.

Wiccans accept that magic is real and can be used as a ritual tool. Not all Wiccans do magic, but all Wiccans accept that magic exists. For many covens and solitary practitioners, magic is an essential part of religious ritual. For others, magic is a practice that can be used not only to connect with the gods, but also to improve our lives and achieve our goals.

Many Wiccans believe in reincarnation, and some may incorporate past life recall into their spiritual practice. Some Wiccans believe that our souls are made of cosmic energy, which is recycled into a new soul after our deaths. Others believe that our soul survives intact from one lifetime to the next. Many famous Wiccan authors have written about their past lives and how reconnecting with those lives informed their practice.

Important Deities and Spirits

The central deities of Wicca are the Goddess and the God. They are two halves of a greater whole, and are only two of countless possible manifestations of the all-encompassing divine. The God and Goddess are lovers, and all things are born from their union.

Though some Wiccan traditions place a greater emphasis on the Goddess than on the God, the balance between these two expressions of the divine plays an important role in all Wiccan practices (remember, polarity is one of the core values of this religion).

The Goddess is the Divine Mother. She is the source of all life and fertility. She gives birth to all things, yet she is also the one who receives us when we die. Although she forms a duality in her relationship with the God, she also contains the duality of life and death within herself. While the God’s nature is ever-changing, the Goddess is constant and eternal.

The Goddess is strongly associated with both the moon and the earth. As the Earth Mother, she is especially associated with fertility, abundance, and nurturing. As the Moon Goddess, she is associated with wisdom, secret knowledge, and the cycle of life and death.

Some Wiccans see the goddess as having three main aspects: the Maiden, the Mother, and the Crone. The Maiden is associated with youth, innocence, and new beginnings; she is the embodiment of both the springtime and the waxing moon. The Mother is associated with parenthood and birth (duh), abundance, and fertility; she is the embodiment of the summer (and sometimes fall) and of the full moon. The Crone is associated with death, endings, and wisdom; she is the embodiment of winter and of the waning moon. Some Wiccans believe this Triple Goddess model is an oversimplification, or complain that it is based on outdated views on womanhood, but for others it is the backbone of their practice.

Symbols that are traditionally used to represent the Goddess include a crescent moon or an image of the triple moon (a full moon situated between a waxing and a waning crescent), a cup or chalice, a cauldron, the color silver, and fresh flowers.

The God is the Goddess’s son, lover, and consort. He is equal parts wise and feral, gentle and fierce. He is associated with sex and by extension with potential (it could be said that while the Goddess rules birth, the God rules conception), as well as with the abundance of the harvest. He is the spark of life, which is shaped by the Goddess into all that is.

The God is strongly associated with animals, and he is often depicted with horns to show his association with all things wild. As the Horned God he is especially wild and fierce.

The God is also strongly associated with the sun. As a solar god he is associated with the agricultural year, from the planting and germination to the harvest. While the Goddess is constant, the God’s nature changes with the seasons.

In some Wiccan traditions, the God is associated with plant growth. He may be honored as the Green Man, a being which represents the growth of spring and summer. This vegetation deity walks the forests and fields, with vines and leaves sprouting from his body.

Symbols that are traditionally used to represent the God include phalluses and phallic objects, knives and swords, the color gold, horns and antlers, and ripened grain.

Many covens, both Traditional and Eclectic, have their own unique lore around the God and the Goddess. Usually, this lore is oathbound, meaning it cannot be shared with those outside the group.

Many Wiccans worship other deities besides the God and Goddess. These deities may come from historical pantheons, such as the Greek or Irish pantheon. A Wiccan may work with the God and Goddess with their coven or on special holy days (see below), but work with other deities that are more closely connected to their life and experiences on a daily basis. Wiccans view all deities from all religions and cultures as extensions of the same all-encompassing divine force.

Wiccan Practice

Most Wiccans use the circle as the basis for their rituals. This ritual structure forms a liminal space between the physical and spiritual worlds, and the Wiccan who created the circle can choose what beings or energies are allowed to enter it. The circle also serves the purpose of keeping the energy raised in ritual contained until the Wiccan is ready to release it. Casting a circle is fairly easy and can be done by anyone — simply walk in a clockwise circle around your ritual space, laying down an energetic barrier. Some Wiccans use the circle in every magical or spiritual working, while others only use it when honoring the gods or performing sacred rites.

While it is on one level a practical ritual tool, the circle is also a representation of the Wiccan worldview. Circles are typically cast by calling the four quarters (the four compass points of the cardinal directions), which are associated with the four classical elements: water, earth, fire, and air. Some (but not all) Wiccans also work with a fifth element, called spirit or aether. The combined presence of the elements makes the circle a microcosm of the universe.

Casting a circle requires the Wiccan to attune themselves to these elements and to honor them in a ritual setting. This is referred to as calling the quarters. When a Wiccan calls the quarters, they will move from one cardinal point to the next (usually starting with east or north), greet the spirits associated with that direction/element, and invite them to participate in the ritual. (If spirit/aether is being called, the direction it is associated with is directly up, towards the heavens.) This is done after casting the circle, but before beginning the ritual.

What happens within a Wiccan ritual varies a lot — it depends on the Wiccan, their preferences, and their goals for that ritual. However, nearly all Wiccan religious rites begin with the casting of the circle and calling of the quarters. (Some would argue that a ritual that doesn’t include these elements cannot be called Wiccan.)

When the ritual is completed, the quarters must be dismissed and the circle taken down. Wiccans typically dismiss the quarters by moving from one cardinal point to the next (often in the reverse of the order used to call the quarters), thanking the spirits of that quarter, and politely letting them know that the ritual is over. The circle is taken down (or “taken up,” as it is called in some traditions) in a similar way, with the person who cast the circle moving around it counterclockwise and removing the energetic barrier they created. This effectively ends the ritual.

There are eight main holy days in Wicca, called the sabbats. These celebrations, based on Germanic and Celtic pagan festivals, mark the turning points on the Wheel of the Year, i.e., the cycle of the seasons. By honoring the sabbats, Wiccans attune themselves with the natural rhythms of the earth and actively participate in the turning of the wheel.

The sabbats include:

Samhain (October 31): Considered by many to be the “witch’s new year,” this Celtic fire festival has historic ties to Halloween. Samhain is primarily dedicated to the dead. During this time of year, the otherworld is close at hand, and Wiccans can easily connect with their loved ones who have passed on. Wiccans might celebrate Samhain by building an ancestor altar or holding a feast with an extra plate for the dead. Samhain is the third of the three Wiccan harvest festivals, and it is a joyous occasion despite its association with death. (By the way, this sabbat’s name is pronounced “SOW-en,” not “Sam-HANE” as it appears in many movies and TV shows.)

Yule/Winter Solstice (December 21): Yule is a celebration of the return of light and life on the longest night of the year. Many Wiccans recognize Yule as the symbolic rebirth of the God, heralding the new plant and animal life soon to follow. Yule celebrations are based on Germanic traditions and have a lot in common with modern Christmas celebrations. Wiccans might celebrate Yule by decorating a Yule tree, lighting lots of candles or a Yule log, or exchanging gifts.

Imbolc (February 1): This sabbat, based on an Irish festival, is a celebration of the first stirrings of life beneath the blanket of winter. The spark of light that returned to the world at Yule is beginning to grow. Imcolc is a fire festival, and is often celebrated with the lighting of candles and lanterns. Wiccans may also perform ritual cleansings at this time of year, as purification is another theme of this festival.

Ostara/Spring Equinox (March 21): Ostara is a joyful celebration of the new life of spring, with ties to the Christian celebration of Easter. Plants are beginning to bloom, baby animals are being born, and the God is growing in power. Wiccans might celebrate Ostara by dying eggs or decorating their homes and altars with fresh flowers. In some covens, Ostara celebrations have a special focus on children, and so may be less solemn than other sabbats.

Beltane (May 1): Beltane is a fertility festival, pure and simple. Many Wiccans celebrate the sexual union of the God and Goddess, and the resulting abundance, at this sabbat. This is also one of the Celtic fire festivals, and is often celebrated with bonfires if the weather permits. The fae are said to be especially active at Beltane. Wiccans might celebrate Beltane by making and dancing around a Maypole, honoring the fae, or celebrating a night of R-rated fun with friends and lovers.

Litha/Midsummer/Summer Solstice (June 21): At the Summer Solstice, the God is at the height of his power and the Goddess is said to be pregnant with the harvest. Like Beltane, Midsummer is sometimes celebrated with bonfires and is said to be a time when the fae are especially active. Many Wiccans celebrate Litha as a solar festival, with a special focus on the God as the Sun.

Lughnasadh/Lammas (August 1): Lughnasadh (pronounced “loo-NAW-suh”) is an Irish harvest festival, named after the god Lugh. In Wicca, Lughnasadh/Lammas is a time to give thanks for the bounty of the earth. Lammas comes from “loaf mass,” and hints at this festival’s association with grain and bread. Wiccans might celebrate Lughnasadh by baking bread or by playing games or competitive sports (activities associated with Lugh).

Mabon/Fall Equinox (September 21): Mabon is the second Wiccan harvest festival, sometimes called “Wiccan Thanksgiving,” which should give you a good idea of what Mabon celebrations look like. This is a celebration of the abundance of the harvest, but tinged with the knowledge that winter is coming. Some Wiccans honor the symbolic death of the God at Mabon (others believe this takes place at Samhain or Lughnasadh). Wiccan Mabon celebrations often include a lot of food, and have a focus on giving thanks for the previous year.

Aside from the sabbats, some Wiccans also celebrate esbats, rituals honoring the full moons. Wiccan authors Janet and Stewart Farrar wrote that, while sabbats are public festivals to be celebrated with the coven, esbats are more private and personal. Because of this, esbat celebrations are typically solitary and vary a lot from one Wiccan to the next.

Further Reading

If you want to investigate Wicca further, there are a few books I recommend depending on which approach to Wicca you feel most drawn to. No matter which approach you are most attracted to, I recommend starting with Wicca For Beginners by Thea Sabin. This is an excellent introduction to Wiccan theology and practice, whether you want to practice alone or with a coven.

If you are interested in Traditional Wicca, I recommend checking out A Witches’ Bible by Janet and Stewart Farrar after you finish Sabin’s book. Full disclosure: I have a lot of issues with this book. Parts of it were written as far back as the 1970s, and it really hasn’t aged well in terms of politics or social issues. However, it is the most detailed guide to Traditional Wicca I have found, so I recommend it for that reason. Afterwards, I recommend reading Casting a Queer Circle by Thista Minai, which presents a system similar to Traditional Wicca with less emphasis on binary gender. After you learn the basics from the Farrars, Minai’s book can help you figure out how to adjust the Traditional Wiccan system to work for you.

If you are interested in Eclectic Wicca, I recommend Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner and Living Wicca by Scott Cunningham. Cunningham is the author who popularized Eclectic Wicca, and his work remains some of the best on the subject. Wicca is an introduction to solitary Eclectic Wicca, while Living Wicca is a guide for creating your own personalized Wiccan practice.

Resources:

Wicca For Beginners by Thea Sabin

Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner by Scott Cunningham

Living Wicca by Scott Cunningham

A Witches’ Bible by Janet and Stewart Farrar

The Study of Witchcraft by Deborah Lipp

#paganism 101#pagan#paganism#baby pagan#wicca#wiccan#traditional wicca#eclectic wicca#scott cunningham#thea sabin#janet and stewart farrar#witch#witchcraft#witchblr#baby witch#long post#mine#my writing#witches of tumblr

727 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katherine Weisshaar, From Opt Out to Blocked Out: The Challenges for Labor Market Re-entry after Family-Related Employment Lapses, 83 Am Sociol Rev 34 (2018)

Abstract

In today’s labor market, the majority of individuals experience a lapse in employment at some point in their careers, most commonly due to unemployment from job loss or leaving work to care for family or children. Existing scholarship has studied how unemployment affects subsequent career outcomes, but the consequences of temporarily “opting out” of work to care for family are relatively unknown. In this article, I ask: how do “opt out” parents fare when they re-enter the labor market? I argue that opting out signals a violation of ideal worker norms to employers—norms that expect employees to be highly dedicated to work—and that this signal is distinct from two other types of résumé signals: signals produced by unemployment due to job loss and the signal of motherhood or fatherhood. Using an original survey experiment and a large-scale audit study, I test the relative strength of these three résumé signals. I find that mothers and fathers who temporarily opted out of work to care for family fared significantly worse in terms of hiring prospects, relative to applicants who experienced unemployment due to job loss and compared to continuously employed mothers and fathers. I examine variation in these signals’ effects across local labor markets, and I find that within competitive markets, penalties emerged for continuously employed mothers and became even greater for opt out fathers. This research provides a causal test of the micro- and macro-level demand-side processes that disadvantage parents who leave work to care for family. This is important because when opt out applicants are prevented from re-entering the labor market, employers reinforce standards that exclude parents from full participation in work.

The decision to become a stay-at-home parent tends to be a constrained one. Today, it is rare for women and men to aspire to become stay-at-home parents; most people hold ideals of balanced work and family arrangements (Stone 2008; Williams, Manvell, and Bornstein 2006). However, balance is difficult to achieve within the modern labor market, in which employers seek candidates who can fulfill “ideal worker norms” of intense time commitment and perpetual availability for work-related tasks (Davies and Frink 2014; Kelly et al. 2010; Turco 2010). Overwork is increasingly common (Cha and Weeden 2014), as is spillover of job-related work into home life (Reid 2011; Turco 2010). These expectations for employees conflict with similarly intensive parenting standards for middle- and upper-class parents (Blair-Loy 2003; Jacobs and Gerson 2001), contributing to parents’ decisions to “opt out” of work to care for children full-time (Stone 2008).1 Opting out is a gendered process: over the past two decades, 18 to 20 percent of mothers did not work for pay in order to care for children for one or more years, compared to a peak rate of only about 1.2 percent among fathers (Flood et al. 2015). These departures from the labor force are usually temporary; for example, the median lapse in employment among mothers is about two years (Reimers and Stone 2008; Stone 2008).

Do parents face penalties when they seek to return to work after opting out? In this article, I examine how demand-side processes, in the form of employer preferences, influence hiring prospects for both mothers and fathers who have previously opted out. I argue that opting out signals to employers that potential employees prioritize family over work, and that the act of opting out violates the ideal worker expectations that are ubiquitous in modern workplaces. This violation of ideal worker norms leads to fewer job opportunities for job applicants who have opted out.

Despite fairly high rates of individuals leaving work for caretaking responsibilities, we know relatively little about the demand-side processes faced by these job-seekers after they decide to resume working (see Lovejoy and Stone 2012). Sociological research has examined historical trends in the rate of opting out (e.g., Boushey 2008); demographic characteristics of mothers who leave work (e.g., Percheski 2008); and supply-side decisions and preferences—for example, why caretakers leave work, and how they conceive of their employment decisions (Stone 2008; Williams et al. 2006). In contrast to the dearth of demand-side studies of opt out applicants, a substantial line of related research examines how another type of employment lapse—unemployment from job loss—affects job prospects (e.g., Eriksson and Rooth 2014; Nunley et al. 2017; Pedulla 2016; Winefield, Tiggemann, and Winefield 1992). Existing research also documents the “motherhood penalty” in the labor market—establishing that mothers face penalties in hiring and wages relative to fathers and childless women—but these studies typically examine mothers with continuous employment records (e.g., Budig and England 2001; Budig, Misra, and Boeckmann 2012; Correll, Benard, and Paik 2007).

What are the mechanisms through which a gap in employment leads to lower callback rates during the job application process? A theory of skill deterioration, derived from human capital theory, suggests that time out of work leads to skills becoming rusty and obsolete; employers prefer to hire applicants with continuous employment records to avoid high training costs (Mincer and Ofek 1982; Nunley et al. 2017). In contrast to skill deterioration theories, signaling theories posit that employment history signals information about the job applicant to the employer beyond skill decline; employers rely on assumptions or stereotypes based on employee characteristics or job history to make hiring decisions (Spence 1973; Stiglitz 2002). Signaling theories have been tested with respect to unemployment: a bout of unemployment “scars” the job applicant by signaling lower applicant competence, and it leads to reduced job opportunities for unemployed individuals (Eriksson and Rooth 2014; Pedulla 2016).

I propose a résumé signaling theory in which opting out for family reasons produces negative perceptions about applicants’ commitment and dedication to work. In this theory, opting out signals a violation of ideal worker norms, which is distinct from the unemployment scarring signal of perceived competence. Given that employers have rigid expectations for employees to dedicate themselves fully to work, violating these ideal worker norms by demonstrating a prioritization of family evokes a moral evaluation of applicants’ work-family choices. Potential employers thus perceive opting out as indicating lower dedication to work and, as a result, view opt out applicants as less worthy of a job.

To test that opting out signals a violation of ideal worker norms—and whether these signals are distinct from perceptions of unemployed and employed applicants—this article presents three empirical studies. In Study 1, I use an original national survey experiment of 1,000 U.S. respondents to test social-psychological perceptions of opt out, unemployed, and employed applicants—all parents. Respondents rated résumés on dimensions that align with ideal worker norm violation as well as unemployment scarring theories. The findings from Study 1 establish that opting out signals a violation of ideal worker norms: opt out applicants are perceived as less committed to work, less reliable, and less deserving of a job than are unemployed applicants. I further find that opt out fathers experience an even greater penalty on ideal worker norm violation measures compared to opt out mothers.

In Study 2, I test how these perceptions play out in the real labor market. I conducted a large-scale audit study in which 3,407 job applications were submitted to professional and managerial job openings across 50 metropolitan areas in the United States, recording callbacks for each application. The audit study tests how each type of résumé signal—unemployment scarring, ideal worker norm violation, and signals of motherhood or fatherhood—lead to differences in employers’ hiring preferences. The audit study findings show that, overall, opting out leads to fewer callbacks than does unemployment, and unemployment, in turn, produces fewer callbacks compared to the continuously employed. In the aggregate, I find no significant gender differences in the effects of employment history.

In Study 3, I exploit variation across the audit study cities to examine how these signals vary in strength as local labor market contexts vary. In labor markets in which job competition is relatively higher, there are longer job queues for each job opening. I predict that in these competitive settings, employers more readily enact preferences to distinguish between negative signals. Weaker negative signals that have less of an effect in low-competition environments will be more apparent in competitive contexts. I find that in competitive job markets, gendered signals become apparent: when there are longer job queues, the motherhood penalty emerges among employed applicants and opt out fathers fare worse than in less competitive cities.

The results of these studies collectively demonstrate that ideal worker norm violations convey stronger negative signals than does unemployment scarring. The effects of motherhood/fatherhood signals are variable across labor markets, with stronger consequences in competitive labor market contexts, and relatively muted effects in less competitive contexts.

This article contributes to scholarship in two key ways. First, I add to scholarship on family, gender, and work by testing to what extent signaling a commitment to family over work influences subsequent career opportunities. Second, scholars have long recognized the importance of both micro-level decisions on hiring processes (e.g., Correll et al. 2007) and macro-level contextual factors (e.g., Fallick 1996; Haurin and Sridhar 2003). To understand how opting out affects job prospects, this study draws on micro-level processes of résumé signals and macro-level labor market contextual variation to develop an integrated theory of signaling and queuing.

Theoretical Influences: Skill Deterioration and Résumé Signaling Processes

How do gender and labor market history influence the hiring process? Two broad theoretical perspectives propose possible mechanisms: human capital theories and signaling theories. Theories of skill deterioration suggest that applicants who have a decline in skills or human capital are less desirable employees and will be hired less frequently. Signaling theories claim that information on a résumé sends a signal to employers based on stereotypes or assumptions. In this study, I examine signals produced from three pieces of information: unemployment, opting out, and motherhood/fatherhood, each of which have the possibility to produce distinct signals for employers.

Skill Deterioration Theories

Skill deterioration theory draws on human capital theories to argue that differences in skills or abilities explain why applicants with employment lapses are less desirable than the steadily employed (Acemoglu 1995; Becker 1964). Human capital theories generally explain variations in job-related outcomes in terms of workers’ differing skills and competencies (Becker 1964). The logic behind this argument is that when individuals have gaps in employment, their skills and human capital deteriorate from lack of use and their skills may become obsolete. By hiring applicants with more recent work experience, employers avoid training costs (Becker 1964).

Skill deterioration incurred during an employment lapse is ostensibly gender neutral and invariant across the type of lapse. Human capital theories have proposed gender differences in the accumulation of skills, but there is no reason why skills, once attained, should decline at varying rates for men and women (Acemoglu 1995; Becker 1964). Skill obsolescence during a lapse should also occur similarly for unemployed and opt out individuals—the reason for a lapse ought not to matter, only the lapse’s duration. Holding constant the amount of time out of the labor force, skill deterioration theory predicts the following hypotheses:

Skill deterioration: Both unemployed and opt out applicants will fare more negatively than continuously employed applicants, but there will be no differences in the effects of opting out compared to unemployment, nor differences between mothers and fathers.

Signaling Theories

In contrast to skill deterioration theory, signaling theories predict varying negative effects for unemployment compared to opting out and for motherhood compared to fatherhood. Developed by economists who recognized an information asymmetry between job applicants and employers, signaling theories propose that résumés provide employers with various pieces of information that “signal” the quality of potential employees (Connelly et al. 2011; Spence 1973, 1981; Stiglitz 2002). Originally applied to theorize how high-quality applicants could signal their ability to potential employers, recent research has extended this theory to establish that résumé information can signal negative qualities as well (Pedulla 2016; Stiglitz 2002). Because employers have limited time and resources to devote to screening and interviewing job candidates, they use résumé information to make decisions about whether to move forward with a candidate. Employment history on a résumé can signal assumptions about the applicant’s quality, ability, and value (Spence 1981; Stiglitz 2002). Résumés can also provide information on applicant characteristics (e.g., education, gender, race, age, parental status), which lead to assumptions and biases about a job applicant based on widely held beliefs about said identity/characteristic (Ridgeway and Correll 2004).

One of the most heavily studied negative résumé signals is current unemployment. Whereas skill deterioration theory argues that unemployed candidates fare worse on the job market due to employers’ fears of reduced skill levels, studies based on signaling find that unemployment incurs penalties beyond what would be expected from skill deterioration. Unemployment scarring studies argue that employers are drawing from limited information on a job applicant, and a lapse in employment is perceived as a signal that the applicant is an inferior worker and less desirable as an employee (Kroft, Lange, and Notowidigdo 2013). Unemployment due to job loss is interpreted as a sign of an unstated negative characteristic and is said to “scar” the job applicant: employers may assume applicants lost a previous job and were unable to regain a job because they are lower-quality employees (Eriksson and Rooth 2014; Gangl 2004). This proposition has been tested empirically by using experimental designs to account for human capital (Pedulla 2016), and by assessing unemployment’s effect net of job tenure, specific skills, and lapse length (e.g., Arulampalam, Gregg, and Gregory 2001; Eriksson and Rooth 2014; Gangl 2004; Ghayad 2015; Kroft et al. 2013).

The reduced-quality signal produced by unemployment has not been operationalized consistently, and scholars tend to use it as an umbrella concept (e.g., Arulampalam et al. 2001). Employers may make any number of assumptions about quality for applicants with longer-term unemployment lapses. For example, these applicants could be perceieved as lower quality at the time of job loss—that is, there could be an unobserved negative trait that led to them becoming unemployed (Stiglitz 2002). This negative trait might be skill levels or on-the-job behavior, such as reliability or interpersonal skills (Clark, Georgellis, and Sanfey 2001). Furthermore, long-term unemployment itself could raise doubts about an employee’s quality, suggesting there is a reason that prevented the applicant from regaining a job over a number of months (Stiglitz 2002). In a recent audit study and survey experiment, Pedulla (2016) takes an important step toward theorizing how quality is perceived for unemployed applicants. Pedulla (2016) compared job applicants with one year of unemployment to applicants with other types of employment histories. This study found that overall, unemployed applicants—particularly unemployed men—received callbacks at substantially lower rates than did the continuously employed (5.9 percent compared to 10.4 percent, respectively). Pedulla theorizes that the scarring unemployment signal could operate through notions of either competence or commitment. Pedulla’s study finds that perceptions of competence mediate the lower callback rate among unemployed men, but he finds no significant effects of perceived commitment for unemployed compared to employed applicants.

How strong is the negative signal of unemployment in the context of other résumé signals? Unemployment scholars would suggest that unemployment scarring occurs largely because of assumptions made about the involuntary nature of unemployment (Kroft et al. 2013; Pedulla 2016). Applicants who have been unemployed for several months or longer not only provoke questions about why they lost their previous position, but why they have not found a new job (Arulampalam et al. 2001; Eriksson and Rooth 2014; Ghayad 2015). Opt out applicants, in contrast, could be perceived as voluntarily having a lapse in employment, and they might avoid the negative competence signals incurred by an involuntary lapse and lengthy job search. Unemployment scarring theories thus predict the following hypothesis:

Unemployment scarring: Unemployed applicants will fare worse than both opt out and employed applicants because of reduced perceived worker quality.

Alternatively, opting out may incur greater penalties than unemployment by signaling a violation of ideal worker norms, a signal that has yet to be considered in demand-side employment research. Ideal worker norms include the expectation that employees prioritize work over all other parts of their lives (Blair-Loy 2003; Davies and Frink 2014; Turco 2010). Professional and managerial jobs today demand intense time commitments, and employers expect employees to always be available (Davies and Frink 2014; Kelly et al. 2010; Rivera and Tilcsik 2016). Employees are increasingly likely to work longer hours (Cha and Weeden 2014), and technological changes have led to greater spillover of work-related tasks at home—such as checking email and responding to phone calls after leaving the office (Reid 2011; Turco 2010). Mothers and fathers alike report high levels of work-family conflict, finding it difficult to fulfill all expectations associated with work and with intensive parenting (Blair-Loy 2009; Davies and Frink 2014; Kelly et al. 2010). Opting out of work to care for children is a direct violation of these pervasive expectations for employees to prioritize work above all. By signaling their lower dedication to work, periods of opting out could undermine applicants’ efforts to re-enter the work force.

This prediction finds support in the caretaker bias literature. Studies have found that prioritizing caretaking tasks over work can result in a host of negative outcomes for employees in their workplaces. For instance, parents who use flexibility policies to try to reconcile work and family demands experience lower wages on average (Blair-Loy and Wharton 2002; Glass 2004), increased harassment (Berdahl and Moon 2013), fewer promotions (Cohen and Single 2001), and lower performance evaluations (Albiston et al. 2012). Scholars of cultural moral schemas argue that gender, work, and family (and their intersection) are areas of life rife with moral conceptions of how individuals ought to behave, and who is a worthy fulfiller of moral standards (Blair-Loy 2003, 2009; Blair-Loy and Williams 2013; Steiner 2007). Because ideal worker standards are proscriptive ideas about how employees should behave, violating these standards invokes moralistic judgments about the worth of the employee—judgments that go beyond strategic estimations of employee productivity, skill level, or availability (Blair-Loy 2009; Davies and Frink 2014; Townsend 2002).

Caretaker and flexibility bias studies focus on penalties for prioritizing family within workplace contexts, but it is reasonable to expect that such censuring would also be evident during the hiring process. Given that ideal worker norms are so pervasive in the professional and managerial occupations that are the focus of this study, I propose that violating these norms will produce large negative effects—potentially larger than the quality signal of unemployment. Ideal worker norm violation theories posit the following hypothesis:

Ideal worker violation: Opt out job applicants will experience worse job application outcomes than will unemployed and employed applicants.

Gender Heterogeneity in Signal Strength

The above theories describe hypothesized variation in signals sent by differing employment histories. Employers are also expected to respond to résumé signals of gender and parenthood. Research on the motherhood penalty in hiring has found that résumé information about motherhood produces reduced hiring chances for mothers relative to childless women and fathers (Correll et al. 2007). The motherhood penalty theory argues that motherhood is a status characteristic, that is, an identity that elicits a host of assumptions and stereotypes about an individual (Correll et al. 2007; Ridgeway and Correll 2004). Bias against mothers is rooted in perceptions of lower competence and commitment to work: mothers are viewed as more distracted, and employers assume that children’s demands will reduce mothers’ availability for work and their dedication to work-related tasks (Correll and Benard 2006; Correll et al. 2007; Ridgeway and Correll 2004). To date, the motherhood penalty literature has focused on the effect of motherhood among currently employed applicants (e.g., Correll and Benard 2006; Correll et al. 2007; Gangl and Ziefle 2009); it would yield the following prediction about motherhood as a résumé signal across other employment statuses:

Motherhood penalty: Within employed, unemployed, and opt out groups, mothers will face penalties compared to fathers.

Because the motherhood penalty involves perceptions of mothers’ lower commitment to work, and ideal worker norm violation theory also predicts lower perceived commitment for opt out applicants, opt out mothers signal lower commitment in two ways (Dumas and Sanchez-Burks 2015; Sallee 2012). This interaction suggests that the motherhood penalty will be amplified among opt out applicants:

Motherhood penalty for opting out: The motherhood penalty will be larger for opt out applicants than among unemployed or employed applicants.

An alternative prediction is that penalties for opting out are worse for fathers than for mothers. This potential “fatherhood penalty” finds support in literature on norm violation, which demonstrates that those who are most expected to hold a norm are more severely punished when they violate the norm. In an audit study of gay men, for example, Tilcsik (2011) found that the hiring penalty for gay applicants was largest when the job advertisements used highly masculine language. With respect to ideal worker norm violations, because fathers are expected to prioritize work and be breadwinners for their families (Rudman and Mescher 2013; Townsend 2002), fathers who opt out could face harsh penalties. Indeed, prior studies have found that evaluators are more willing to criticize and stigmatize parents in nontraditional positions, such as stay-at-home fathers, questioning whether they were making appropriate work/family decisions (Brescoll and Uhlmann 2005; Brescoll et al. 2012; Coltrane et al. 2013). Put another way, because fathers face greater pressure to work hard and commit to work compared to mothers, fathers who opt out could be perceived as highly uncommitted to work, because they violated more rigid ideal worker norms through their decision to leave work for family reasons (for a related discussion of men who request family leave, see Rudman and Mescher 2013). This fatherhood penalty leads to the following hypothesis:

Fatherhood penalty for opting out: Fathers who opt out will be viewed more negatively than mothers who opt out.

Because this study focuses on mothers and fathers, I can test for gender heterogeneity among parents in the effects of opting out.2

Theoretical predictions for how gender may interact with unemployment scarring are less clear. Pedulla (2016) found that unemployed men received lower callback rates than unemployed women; this gender difference was marginally significant in the audit study, but the gender gap was not reproduced in a follow-up survey experiment of mechanisms. Studies on time use document that upon unemployment, mothers increase housework and childcare time to a greater degree than do unemployed fathers (Berik and Kongar 2013). It is thus possible that employers interpret unemployment differently for mothers and fathers, and perhaps believe that mothers become more committed to family (and less committed to work) during their lapse. In this case, unemployed mothers would experience similar processes as opt out mothers. The theoretical processes concerning the gendered effects of unemployment are less clear, however, so I do not produce a priori predictions on this interaction.

The above signaling theories imply a two-step process for how signaling affects employment outcomes. First, a piece of information on the résumé triggers employers’ assumptions about the job applicant. Second, if employers think these (perceived) qualities are relevant to hiring, then in the aggregate, applicants with negative résumé signals will experience reduced callback rates when applying for jobs. The survey experiment presented in Study 1 tests the first part of the process: whether the signal itself produces different assumptions about job applicants. The audit study, presented in Studies 2 and 3, examines the second step—how employers in an actual labor market respond to each signal in their callback decisions.

Study 1: Perceptions of Applicants

Theory

In Study 1, I used an original survey experiment to test whether skill deterioration or signaling theories best predict how perceptions of opt out job applicants compare to perceptions of unemployed and employed applicants.

Skill deterioration theory proposes that perceptions of skills lost are the predominant reason why a gap in employment could produce negative outcomes. I asked survey respondents to rate applicants’ capability as a primary measure of skill level. If skill deterioration were the only process occurring and there were no additional signaling processes, this theory would predict that unemployed and opt out applicants will both experience negative capability ratings, relative to employed applicants, and capability will be the only perceived difference between intermittently employed and continuously employed applicants.

Unemployment scarring theories suggest that unemployment operates as a negative signal through perceived employee quality. The theoretical argument is that evaluators assume that applicants with a bout of unemployment are weaker employees overall—whether in their ability and skills or their day-to-day work output. Perceived quality can be operationalized in a number of ways. Capability (a measure of perceived competence) and reliability (measuring dependability and consistency in work) have been demonstrated to affect perceptions of unemployed individuals (Clark et al. 2001; Pedulla 2016). In the context of the survey experiment, the unemployment scarring theory thus predicts that unemployment will lead to reduced perceptions of capability and reliability, relative to both employed and opt out applicants.

Violating ideal worker norms by prioritizing family over work—as is the case with opt out applicants—signals reduced commitment to work and less reliability at work (Brumley 2014; Davies and Frink 2014; Dumas and Sanchez-Burks 2015; Sallee 2012). In other words, evaluators may be concerned that applicants will leave work again in the future, or that they will be less present on a daily basis—because of competing family demands—and thus will be less reliable (Fuegen et al. 2004; Rivera and Tilcsik 2016). To capture the moral assessment associated with violating ideal worker norms, respondents were asked how deserving of the job they perceived applicants to be. In contrast to opt out applicants, unemployed applicants are not predicted to be perceived as less deserving—all else being equal, unemployed applicants may garner sympathy and be thought of as more deserving of a job, because they did not voluntarily stop working and have expressed continued interest in working. Thus, if opting out corresponds to a violation of ideal worker norms, then opt out applicants should be rated as less committed, deserving, and reliable than unemployed and employed applicants.

Finally, Study 1 allows for a test of competing predictions for gender heterogeneity in the effects of opting out. On the one hand, opting out could be worse for mothers than for fathers. Because the motherhood penalty operates in part through perceived commitment (Correll et al. 2007; Fuegen et al. 2004), opt out mothers may be perceived as even less committed than working mothers. On the other hand, ideal worker norms apply more strictly to fathers (Townsend 2002), so opt out fathers who violate these norms may be penalized to a greater extent than opt out mothers. Thus, either opt out mothers or opt out fathers may be rated lower on ideal worker measures (commitment, deservingness, and reliability).

Survey Experiment Design and Methods

The survey experiment was designed to test the effects of unemployment and opting out, relative to same-gender continuously employed applicants. The experiment was fielded by YouGov to a sample of 1,000 U.S. respondents3 in January 2014. YouGov samples from a panel of approximately 1.8 million individuals in the United States and uses a matching algorithm to create a sample representative of the same population targeted by the American Community Survey (i.e., the noninstitutionalized adult population).

Survey respondents were told they were helping a large U.S. accounting firm evaluate job applicants for a midlevel accounting position, and they would be presented with applications for two of the final applicants for the position. I chose accounting because it is an occupation most Americans are familiar with, is a large and growing profession (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2016), and has been used in existing experimental studies (e.g., Pedulla 2016). All respondents viewed one continuously employed applicant and a second applicant who was either unemployed or had opted out. Within respondents, applicant gender was held constant, such that both résumés belonged to either two mothers or two fathers.

This experimental design allows for a strong causal test of the effects of opting out and unemployment. When considering two applicants who vary only on employment history, does the same decision-maker respond differently to intermittent employment compared to continuous employment? Within-subject estimates of the effect of unemployment and opting out, compared to continuous employment, allow for a test of how each type of intermittency leads to different perceptions about job applicants.

Respondents rated each fictitious applicant on several dimensions: commitment, reliability, capability, and deservingness. For example, respondents were asked: “How committed do you consider Name?” Response options ranged from 1 (not at all committed) to 7 (extremely committed).4 These measures were developed based on social psychological literature and existing findings about unemployment, motherhood, and ideal worker norms (e.g., Correll et al. 2007; Davies and Frink 2014; Pedulla 2016). Because applicant gender was held constant within respondents, the design of Study 1 tests signaling of employment history more precisely than motherhood or fatherhood signals.5 However, between-subject estimates of gender can give clues as to whether there are amplifying or muting effects of motherhood and fatherhood.

Study 1 Results: Micro-Level Perceptions

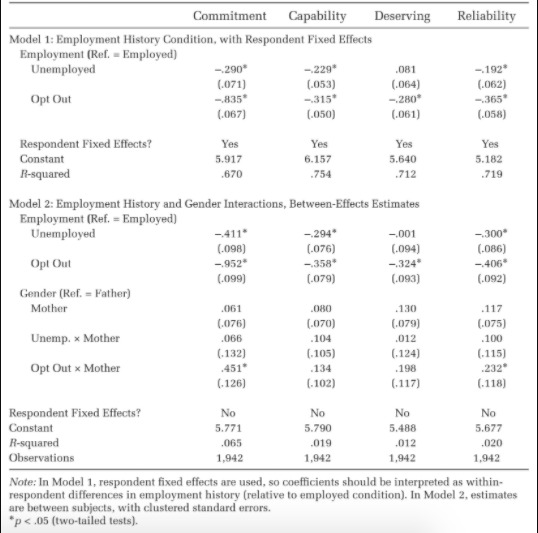

Table 1 presents findings from OLS linear regressions for each of the résumé ratings, with fixed effects for respondent. The treatment effects in these models can be interpreted as the within-respondent difference between intermittent employment (unemployed or opt out) applicant ratings, compared to a same-gender continuously employed applicant.

Table 1. OLS Regression Estimates of Experimental Condition on Résumé Rating Measures

With respect to the unemployment signaling theories, unemployed applicants were rated significantly lower than employed applicants on measures of commitment, capability, and reliability. These are all measures of quality, confirming theories of how unemployment scarring signals operate through perceived quality.

Opt out applicants were rated lower than employed applicants on measures of commitment, capability, deservingness, and reliability. Commitment and reliability directly correspond to the violation of ideal worker norm theories. Opt out applicants, but not unemployed applicants, were rated as less deserving of the job than employed applicants. This suggests that the act of opting out contributes to ideas that these applicants are less in need of a job. The deservingness penalty suggests a moral violation—individuals who work hard and are dedicated to work are perceived as deserving and worthy (Blair-Loy 2009), but opting out violates these ideals and thus these applicants are viewed as less worthy of a job.

Figure 1 displays the average predicted levels of each standardized rating measure, with 95 percent confidence intervals. Figure 1 is from the fixed-effects model (see Table 1, Model 1), with dependent variables standardized to allow for interpretation across measures. Opting out yields a predicted penalty of about .2 standard deviations from the mean across measures of capability, reliability, and deservingness (–.187, –.158, –.203, respectively). The largest penalty for opting out is produced through perceptions of commitment (–.459 standard deviation units). When testing for significance in the ratings for unemployed compared to opt out applicants, the opt out effect is significantly more negative than the unemployed effect on measures of commitment, deservingness, and reliability (p < .05). Compared to employed applicants, both the unemployed and opt out applicants incur penalties on capability ratings and are not viewed as significantly different on this measure.

Figure 1. Survey Experiment Ratings by Employment Condition. Note: Estimates are from a fixed-effects model (see Table 1, Model 1) with standardized dependent variables.

Gender Differences in Ratings

Because respondents viewed two résumés from applicants of the same gender, it is not possible analytically to use respondent fixed effects and test for main effects of mother/fatherhood in rating outcomes. In the bottom panel of Table 1, I present between-subject estimates of the effects of employment, gender, and employment × gender interactions. Standard errors are clustered by respondent.6

Overall, I find no significant gender differences in the effects of employment or unemployment. In contrast, opting out does produce some gendered effects. On measures of commitment and reliability, opting out is significantly less negative for mothers than for fathers. This finding provides support for the fatherhood penalty hypothesis for opting out, which predicted that opt out fathers will experience greater penalties for violating ideal worker norms than will opt out mothers.

Discussion of Study 1 Findings

Study 1 demonstrates three important findings. First, comparing unemployed to employed applicants, I find partial support for the unemployment scarring hypothesis: unemployed applicants were rated lower than employed applicants on capability, reliability, and commitment.7 However, opt out applicants were rated lower than unemployed applicants on perceptions of commitment, deservingness, and reliability. Because these measures correspond to ideal worker norm standards, Study 1 establishes that opting out signals a violation of ideal worker norms, and that ideal worker norm violations are stronger negative signals than is unemployment scarring, supporting the ideal worker norm violation hypothesis.

A second important finding is that both unemployed and opt out applicants incur similar penalties on perceived capability, which is a measure of perceived skill decline and competence. This finding suggests that skill deterioration is at play, and it provides partial support for the skill deterioration hypothesis: both types of lapses produce assumptions about potential skill decline. However, in contrast to a pure skill deterioration explanation, unemployed and opt out applicants are not rated lower solely based on capability; they additionally incur penalties on other dimensions.

These two findings suggest that if employers care most about skills and ability in sorting job applicants, then unemployment and opting out should have similar effects in real job application settings. If, however, employers prefer that employees uphold ideal worker norms, then opt out applicants will fare worse than unemployed applicants when attempting to gain a job. The audit study will test these processes.

The third key finding from Study 1 is that unemployment produced no gender differences in effects, but opting out was somewhat worse for fathers than for mothers. Because of the survey experiment design—in which respondents viewed two applicants of the same gender—it is possible that gender effects could emerge differently in a context with both men and women applicants. The audit study will test to what extent this fatherhood penalty among opt out applicants appears in real labor market settings.

Study 2: Audit Study Main Effects

Theory and Hypotheses

To examine how signals of unemployment scarring and ideal worker norm violation affect demand-side employer preferences in hiring, I conducted a large-scale audit study with the same six experimental conditions as used in the survey experiment. Audit studies, a type of field experiment, have been considered the “gold standard” for establishing employer preferences or discrimination in hiring (e.g., Pager, Bonikowski, and Western 2009). The audit study methodology combines the benefits of experimental research to assess causality with the benefits of observational studies that assess real-life effects outside the laboratory.8 By sending fictitious résumés and job applications in response to real job openings, experimentally manipulating particular qualities on the résumés, and recording callback rates across the experimental conditions, audit studies allow researchers to measure employer preferences in ways that are not observable in most types of survey data.

Based on the employment results from the survey experiment in Study 1, I argue that opting out signals a violation of ideal worker norms. If employers value ideal worker norms, they will view this violation as a meaningful negative signal. Opt out applicants will thus receive fewer callbacks than both unemployed and employed applicants. In Study 1, I found that unemployment signals lower quality relative to continuous employment, and unemployment scarring theories predict that unemployed applicants will receive fewer callbacks than employed applicants. In addition, I found that both unemployed and opt out applicants were rated similarly on measures of capability. If employers view capability signals as more important than ideal worker norm violation signals, then opt out and unemployed applicants should receive similar callback rates in the audit study.

The survey experiment found that opt out fathers were rated lower than opt out mothers on ideal worker norm violation measures. This suggests that in the audit study, opt out fathers will receive fewer callbacks than opt out mothers. Although I found no evidence of the motherhood penalty in the survey experiment, the experimental design was not well-suited to observe overall gender effects. It is thus possible that in a competitive environment with mixed-gender applicants (as is the case in the audit study), a motherhood penalty will emerge, either in the main effect or in amplifying the effect of opting out.

Audit Study Design

In this study, one job application was submitted to each of 3,407 job openings that were posted on a large job-listing website between August 2015 and January 2016. The job listings were sampled from 50 major metropolitan areas in the United States, allowing for a range of labor market contexts. This sample yielded about 600 jobs per experimental condition.

In the applications, experimental manipulations (gender and employment status) were signaled in two places: on the cover letter and on the résumé itself. Gender was signaled through the applicants’ names, which are common names and easily identifiable by gender. The names (Elizabeth/Joseph Anderson, Emily/Sam Harris) were pretested on Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online platform, and respondents rated names as similar in terms of gender recognition, assumptions about applicants’ race/ethnicity, and commonness.

All of the fictitious applicants are parents. To signal parenthood, the cover letters state that applicants are moving to a new city with their family, which is why they are seeking a new job. Applicant résumés also include a line stating that the applicant was a parent volunteer at the local elementary school. Opting out is signaled on the résumé by stating next to the most recent job that the applicant “left to take care of my children.” This is restated in a similar manner on the cover letter.9 Unemployed applicants’ résumés state that they were laid off due to downsizing from their most recent job.10 Résumés for both unemployed and opting out applicants state they were out of work for a period of 18 months, which holds constant the length of employment lapse across lapse type.

All applicants are college-educated and have held two jobs since college for a total of about 9.5 years of work experience. Across each employment condition (continuously employed, unemployed, and opt out), applicants have the same number of years of work experience, but the timeline shifts for those with employment lapses. For example, the unemployed applicant has experienced a contemporary bout of unemployment but has the same number of years of employment as the continuously employed applicant. This timeline implies that applicants are approximately 32 to 34 years of age, making it reasonable that they could be parents.

Job applications were sent to five types of positions, each of which requires a college degree but no additional licenses or degrees: human resources managers, marketing directors, accountants, financial analysts, and software engineers.11 Skills and language describing past work experience were tailored to the job type, but details of the cover letter and résumé were constant across condition. All the fictitious applicants had real emails, phone numbers, and addresses. The separate phone numbers for each name had a recorded voicemail with a male or female voice.

To sample across cities, I used a major job-posting website that accumulates job postings from multiple smaller websites. To determine which jobs to send applications to, I created a Python script that enabled web scraping of all relevant job openings within 25 miles of each of the 50 cities in the study. Each day that I sent out applications, I scraped all jobs that were listed since the previous application date (typically every weekday) for each city and job category. For instance, the script collected all jobs listed in each of the 50 metropolitan areas that matched search criteria for the five job types (e.g., software engineering in New York City). The information scraped included the full job description, the company, salary, job title, and application website. From this complete list of jobs, I randomly subsampled to select which job openings to send applications to. For example, in one day there might be more than 7,000 jobs posted across the five job categories and 50 cities, and I might sample 200 from this list to send applications to in that day. Because I collected information on both the sample and the full list, I was able to verify that the sampled jobs did not differ from the full population on characteristics such as salary, description key words, and length of time listed on the website. Some audit studies do not use computer-generated random samples and rely on researchers choosing relevant jobs. This yields the potential for researchers to unconsciously bias the selection process, a possibility that is untestable because data on non-selected jobs are not collected. My sampling process eliminates this possibility.

Measures and Analytic Strategies: Study 2

The dependent variable of interest is the callback rate. When employers responded to a submitted job application, responses were coded if they requested an interview with the applicant. For example: “Dear Joe, We appreciate your interest in a career with us. Congratulations on being selected for our initial screening. We think you are a strong candidate for our marketing team and would like to set up a phone interview. Please call us to discuss this opportunity further and find a time to interview.”12

For the majority of applications, no response was received. This is typical of audit studies—past studies have found about an 8 percent response rate (e.g., Pedulla 2016; Tilcsik 2011). In the overall sample, 9.45 percent received an interview request, and 8.34 percent received a formal rejection. The remaining applications received no response, which is a presumed rejection.13

Study 2 gives results from the main effects of the experimental conditions on response rates. Because of random assignment, any difference in response rates by condition can be attributed to the experimental manipulation, and simple t-tests of mean differences are adequate to test for significant differences. In addition, I conducted logistic regressions predicting a callback (0 = no callback, 1 = callback). The primary independent variable is the experimental condition (employment history and gender), and models control for job type.

Study 2 Results: Audit Study Main Effects

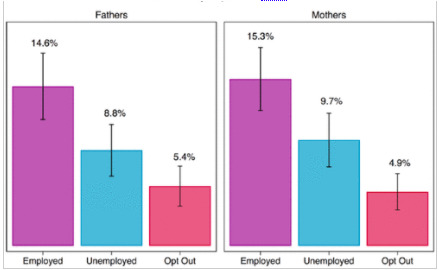

Figure 2 displays the mean callback rate by experimental condition, with 95 percent confidence intervals. The results show that employed fathers and mothers received the highest response rates. Among employed fathers, 14.6 percent received requests for interviews, compared to 15.3 percent of employed mothers; this small gender difference was not statistically significant. Relative to the continuously employed, unemployed applicants received about two-thirds as many callbacks: 8.8 percent of unemployed fathers and 9.7 percent of unemployed mothers received interview requests. Finally, opt out applicants fared the poorest in terms of callback rates. Only about 5.4 percent of opt out fathers and 4.9 percent of opt out mothers received interview requests. Relative to their unemployed counterparts, opt out applicants were about half as likely to receive an interview request (t-statistic = 4.03, p < .05).

Figure 2. Mean Response Rates by Experimental Condition in Audit Study, All Job Types Source: Audit study data, collected 2015 to 2016.

Table 2 presents logistic regressions predicting callback rate, with controls for job type. Model 1 includes the main effects of employment, and Model 2 interacts employment with gender. These results show that the employment effects are statistically significantly different, but there are no statistically significant gender differences.

Table 2. Logistic Regressions Predicting Callback from Audit Study, across Experimental Conditions

Discussion of Study 2 Results

In the audit study, unemployed applicants were penalized relative to the continuously employed, and the opt out applicants faced a greater disadvantage relative to the unemployed. With respect to the hypotheses, a pure skill deterioration explanation does not hold, because opt out applicants faced greater disadvantages than the equivalently qualified unemployed applicants. The scarring signal of unemployment is evident, but this signal is less damaging to hiring opportunities than is the violation of ideal worker norms that opt out applicants demonstrate. Within each employment condition, results are consistent by gender, with no evidence of the motherhood penalty in the main effects, and no evidence of the fatherhood opting out penalty in the main effects.14

Overall, these findings support the ideal worker norm violation hypothesis. The unemployment scarring hypothesis is partially supported, because unemployment produces a negative effect relative to continuous employment. However, in these occupational contexts, violation of ideal worker norm signals swamp quality signals of unemployment and produce greater negative results.

Why are there no observable gender differences in these effects? As I will discuss in more detail later, these résumés are relatively high quality—the employed applicants’ callback rate was higher than in several recent audit studies (including Correll and colleagues’ [2007] motherhood penalty study). Gendered assumptions of motherhood and fatherhood might be minimized by résumé quality. Or, motherhood and fatherhood might send relatively weaker signals than employment history, and as such these signals were obscured by the stronger employment history signals. If this were the case, then weaker signals would be observable only in certain conditions. I propose that variation in callbacks across local labor market context—particularly, the competitiveness of a labor market—allows for testing of signal strength. In a low competition labor market, weaker signals are not easily observable because there are fewer job applicants, and employers must prioritize ranking applicants with strong signals. In highly competitive markets, employers have more applicants to choose from, and in these contexts weaker signals can be used to rank applicants. Study 3 tests these propositions.

Study 3: Variation In Callbacks Across Local Labor Markets

Signaling could operate differently across local labor markets. Labor market scholars have proposed queueing theories to explain how hiring processes work across contexts. The queueing approach to hiring is as follows: job-seekers rank jobs by preference, and employers rank job applicants for a particular job opening (Blanchard and Diamond 1994; Fernandez and Mors 2008; Moscarini 2005; Reskin and Roos 2009). The extent to which these queues overlap determines job outcomes (callbacks and eventual hiring) (Reskin and Roos 2009). Because researchers control the job application strategy in audit studies, job-seekers’ interests are rendered irrelevant, allowing for a focus on employers’ perspectives. In queueing theories, if a certain characteristic is viewed as less desirable (e.g., motherhood), then a résumé signaling this characteristic will place the applicant further back in the queue (if all else is equal).

The queueing theory allows for a theoretical test of relative signal strength by examining to what extent the outcomes associated with résumé signals vary across labor market context. Queueing theories do not predict that a signal itself changes across context (Moscarini 2005) (e.g., opting out may produce a negative signal across all contexts), but that an applicant’s queue position as a result of the signal could change due to the size of the applicant pool. Thus, the observed effects of résumé signals can vary across labor market competitiveness, which allows for a test of relative signal strength.

The predictions of signal variation across labor markets are as follows. Local labor markets that are competitive—with relatively few job openings compared to the number of job-seekers—are associated with longer queues for any particular job (Fernandez and Mors 2008; Reskin and Roos 2009). In these competitive markets, a résumé trait that sends a relatively weak negative signal could push an applicant farther back in the queue in an absolute sense: even if their relative queue position remains constant, in competitive environments there will be more desirable applicants ranked higher in the queue (Reskin and Roos 2009). In contrast, a labor market with low competition may be more forgiving of negative signals; with shorter queues, fewer ideal applicants top the queue. Finally, signals could be invariant to labor market context; this might occur if a signal is so negative that it pushes an applicant toward the bottom of a queue no matter the context. If this is the case, there may be no observable differences in callback rates across context.15

The following hypothetical example helps illustrate the logic of this argument. Consider two signals, one weaker and one stronger. Suppose the weak signal moves an otherwise ideal candidate 10 percent lower in a ranking of job candidates, whereas the strong signal moves this ideal candidate 50 percent lower in ranking positions. In a less competitive context in which there are 10 applicants for a job, the weak signal moves a candidate from position 1 to position 2, whereas the strong signal moves the candidate down to position 6. If three applicants are called in to interview, the weak signal candidate gets a callback but the strong signal candidate does not. In a competitive context with 100 job applicants, the signals may produce the same relative effect but move candidates further down a queue in an absolute sense. Now, the weak signal with a 10 percent penalty moves the candidate from position 1 to position 11, and the candidate with a strong negative signal (50 percent) moves to position 51. When the top three applicants are offered an interview, neither candidate receives a callback. Thus, the weak signal is only observed to produce a negative effect in competitive environments, whereas the strong signal is observable across all contexts.