#the legend of croquemitaine

Text

Charlemagne's Vision (L'Épine's The Legend of Croquemitaine) by Gustave Doré

#charlemagne#art#gustave doré#legend of croquemitaine#chivalry#knights#knight#franks#frankish#history#medieval#middle ages#france#roland#the legend of croquemitaine#mitaine#ernest l'épine#ernest l'epine#the days of chivalry#crusade#crusades#chivalric romance#carolingian#germanic#europe#european#christianity#christian#emperor#christendom

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

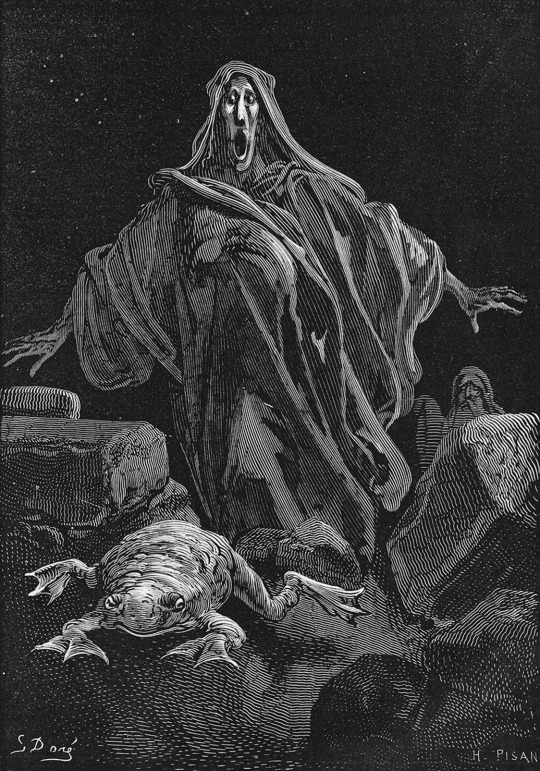

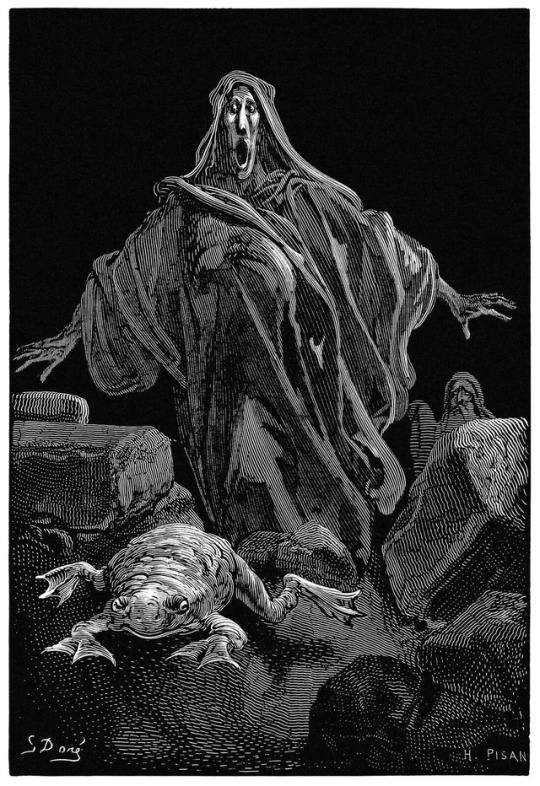

Gustave Doré - The Shriek of Timidity

illustration for Quatrelles' 'The days of chivalry, or, the legend of Croquemitaine', 1866.

#gustave doré#the shriek of timidity#quatrelles#the days of chivalry or the legend of croquemitaine#symbolist art#art#engraving#illustration

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently spoke of Pierre Dubois and evoked the confused and convoluted enigma that are his world-famous Encyclopedias - beautifully illustrated, a masterpiece of fae art, a Renaissance of the fair folk, a deep mine and fabulous treasure of folkloric, literary, mythological references... But also a very convoluted, invented, reinvented, unfaithful-yet-faithful work that freely uses the poetic license and the "storyteller license" to recreate a fairy world that sometimes has little to do with actual folkloric material. And that's because, as I said and as too many people seem to forget, Pierre Dubois is a storyteller and a writer before anything.

Today I want to briefly evoke his purely literary work, not his encyclopedias, or his books about ghosts or trolls, or his manual of elficology, or his anthologies of collected fairytales. His purely literary work - but still deeply inspired by folklore and fairytales. More precisely a short story collection of his called "Comptines assassines" (Murderous nursery rhymes):

This book is actually a sequel to a previous short story collection called "Contes de crime" (Crime fairytales ; a pun on "Grimm fairytales" because in French "Grimm" and "crime" sound similar). Both collections are based on the same key concept: take a fairytale, a nursery rhyme, a fairy-legend, and twist it into a dark short story - sometimes a crime, sometimes a horror novel, sometimes simply disturbing reality.

For example, in Comptines assassines, Dubois tackles twice the topic of "Let's follow the crimes and mad mind of a fairytale-inspired serial killer". Once in his "Puss in Boots" short story, where the titular cat becomes a fairytale-obsessed serial killer of the Interwar era deeply involved with the motif of the Great War mutilees ; and another in his "Bluebeard" short story, making the Bluebeard character a current day serial killer mixed with the Halewyn legend (and it is left unclear if he isn't the ACTUAL Halewyn) who picks of prostitutes and places them in the Bluebeard scenario pretending a "bizarre, excentric role-play game" when in fact he just wants them to end up like Bluebeard's victims... And there's also some really weird and bizarre stories, such as his "Croquemitaine" story (the French bogeyman), which is a Sherlock Holmes story about the titular detective ending up on the trace of a child-killer who somehow returned as a monstrous ghost thanks to a medium's ill-organized seance - and Arthur Conan Doyle actually meets Sherlock... Its typical Dubois bizarreness.

The reason I wanted to speak of this collection specifically is because, as a collection of short story, it truly allows to present the best and the worst of Dubois as an author, since some of his short stories are truly brilliant, and others sadly badly done. I say sadly because Dubois always has good and interesting ideas, and he always cleverly plays of tropes and motifs and archetypes... But the executon is very often lacking.

And this precise collection has two story that are perfect opposites. "The old woman who lived in a shoe" and "The Musicians of the town of Bremen".

"The old woman who lived in a shoe" is the longest short story of this collection, so long it is basically a novela. And the basic idea is very efficient: in an old-but-not-too-distant England, various people of the high society with apparently no relationship to each other are brutally murdered. Here's the twist however: they are murdered by nursery rhymes characters, or by "Alice in Wonderland" ones. And the police, soon driven mad by this insane investigation, ends up calling forth a "fairy detective" expert in supernatural cases (who was involved in a previous story in "Contes de crime"). This is a strong and solid basis, and it works for the most part. Take each of the murders - because the investigation is for a first part pushed on the background, onto quick recaps summaries and "what happened" aftermaths, the better to highlight the dead end and mad frustration of the investigators. The murders are all very interestingly set - each victim is fleshed out in one given scene, each one evokes various archetypes, stereotypes or just "types" of the English society and the English literature, and then the encounters with the nursery-folks are all set in a brilliantly disturbing "fantastique" way, always simple and short but very efficient. The whole thing is told with a distinct British humor, sometimes slight, sometimes very heavy, and Dubois shows here his immense love and great passion for everything British (he always keeps in his bibliographies a section for all the English books of literature or folklore he read).

But here's the problem: this thing is... too much. Too long, too flowery, too flowing, too extensive, too bloated. That's one of Dubois' main vices and one of his greatest writing flaws - he doesn't know when to stop. He writes too much, he extends everything, he describes all with so much detail. We can at least forgive him for the series of murders opening the novel because each one, with such an exorbitant and extensive style, manage to present us a full, lively, complex portrait of each character and scenes, that is always brilliantly cut short by the childishly simple and yet completely reality-breaking supernatural of the murders. We can forgive that - but when the "fairytale detective" gets on the case... By Jove it is all too much. If this had been a novel, I think it would have worked much better - there would have been time to breathe, space for the sentences to flow right, but here everything is so crammed it boils and erupts like a volcano. And while the conclusion is interesting in theory, I do think its handling was... between muddled and dubious. Not to give too much spoilers, but Dubois wanted clearly to mix together the motif of "The old woman in the shoe had many children - and these children were nursery rhymes folks" ; the idea of "The fairies are pissed off humanity are destroying their land and take revenge" ; and an exploration of Lewis Carroll's life and how his Alice work haunts England today. But the result is... let's say it is a difficult result and touchy subject, as Dubois tries to explain Carroll's obsession with little girls by the involvment of a fairy in his life, and the whole handling of this is... Well it needs some careful reading and contextual considerations, because I couldn't tell if Dubois was actually making a big blunder by handling badly the topic, or if he actually did something that could work in some very bizarre way. And I will not insist on how Dubois, in his famous habit of mixing everything, insisted on mixing together the Alice books and the nursery rhymes of England as a whole into one and same world, making it so that for someone who hasn't read Carroll they could believe you'd find in Alice books Mother Goose or Old King Cole...

So yes that's the bad - but what about the great? The great is "The musicians of the town of Bremen" and I am really sad this story wasn't translated in English for me to share with you (or maybe it was?). To give you the simple but brilliant effect of this story I will recap it, but to avoid spoilers if you want to read it I'll put it under a cut.

Contrary to what the title says, the story isn't a rewrite of "The musicians of Bremen" but actually a "mix fairytales together" tale, and Dubois shows here his immense love, passion and knowledge of fairytales in one clever and poetic story - in an effort that reminds me of his Elficology Manual.

Say hello to George Boutonnet, a 20th century man with a frankly... Not happy life. Despite being an adult with a job, he stll is under the control of his old and tyrannical mother who, for example, insists on him having regular dinners with her to which he should never be late and always bring the same food. His mother's bad influence had already started as a kid, when she forced him to listen entirely and repeatedly to "L'Enfant et les Sortilèges" (Ravel's The Child and the Spells) - which deeply traumatized him, especially the scene when the child is punished by living furniture and wild animals and can only scream "Mommy!". He spent a childhood stuck between doing all his homework correctly under the stern eye of his mother, and brief moments of carefully looking at her precous books of fairytales - but these fairytales did not allow him any escapism either, because it was the Gustave Doré's illustrations, that scared him (he preferred Félix Lorioux as a child), and all the stories of Perrault, Grimm, madame d'Aulnoy and the countess of Ségur left him even more depressed - while all those virtuous girls and brave boys and couragous knights defeated the ragons and won eternal love, he couldn't escape his harsh and stern life... And so he grew up to become a middle-class office worker, always careful, prudent and meek, tyrannized by his bosses and his mother, living alone without any romantic potential, and having an extremely strict and precise schedule where every daily activity is timed precisely.

Except one day, when his alarm clock doesn't work, he wakes up too late, and this results in him going into a frenzy panic as he tries to stich up his schedule - because today is the day he is supposed to arrive on time to eat with his mother, and bring her cake. In his chaos and panic, after finally getting the cake and crossing with his car the wood that separates his home from his mother's, he needs to stop in the forest to pee. And... this turns out to be a revelation for him, because all his life, he kept crossing in his car the wood without ever actually stepping his foot in it. His mother never took him to the woods, too "wild and dangerous" - she didn't even taught him how to recognize flower species. So when he finds himself there, surrounded by unknown flowers, bizarre insects, and all those forest scents he never felt before, he can't help it, he walks around, he explores, feeling like a kid again. And as he walks around he sees... Little Red Riding Hood. Or rather a girl dressed exactly like her. Amused, he has a talk with him where he reveals he knows everything about her - much to the girl's amazement, and when she asks him how he knows her identity, he claims to be a wizard, which the girl immediately believes. And when he keeps joking (because he believes it is all a joke) about the wolf - this time Little Red is confused as there's no wolves in this forest, and she flees the man thinking he is one of those bizarre and nasty adults that like to mess up with kids' head.

Boutonnet, confused, ends up walking down the path Little Red Riding Hood came from... And discovers a fairytale village. THE fairytale village - with castles and beautiful landscapes and cute little houses and superb towers... Boutonnet thinks it's some amusement park, some local fair - but when he meets Gepetto in his workshop who is sculpting what will become Pinocchio (in fact it is Boutonnet himself who suggests the name Pinocchio), he starts realizing... Maybe something else is up. He tries to evoke Pinocchio's future misfortunes and misadventures, but Gepetto wants to hear nothing of those weird stories - claiming Boutonnet is just like "all those other folks from behind the hill", always coming in whith disastrous warnings when the truth is, nothing bad ever happens here. What truly convinces Boutonnet's however is when Gepetto summons Puss in Boots, who promptly asks the man to become his master, and when the latter agrees the cat literaly changes by magic his 20th century clothes into a fairytale-prince outfit.

Thus convinced he is truly in the world of fairytales, Boutonnet becomes the subject of a tour with Puss in Boots as a guide, to find himself a wife among the numerous princesses, queens and fairies of the area - and he gets to enjoy a wonderful, colorful world of talking flowers and singing frogs directly out of Lorioux's drawings, seeing the Goat with her seven kids, and Polichinelle, and the baron of Münchhausen, and fairies, and Hans my Hedgehog, and Riquet with the Tuft, and the seven dwarfs, and Tom Thumb... This is where Dubois' narrative style works the best, as his over-flowering, extensive listing and complex scene descriptions fit perfectly this "wonderful panorama of fairytales" we are supposed to see - and it is an abundance of fairytales and nursery rhymes references, and tons of puns based on popular culture, and fascinating description of fairy castles, and an abundance of baked goods, candies and cakes that Boutonnet gets to stuff himself with... And Boutonnet is in Heaven because it is everything his life is not - magic everywhere, everybody looking at him with respect and kindness, as much sugary treats as he can eat, cool clothes. An especially important part is that his name (which can translate as "Small-Button" and was a source of mockery when he was a child) is here fully accepted as a typical fairytale name.

Boutonnet is also very impressed by the beauty of the fairytale princesses - notably, after one breathtaking sight of Cinderella, he gets to encounter Snow White herself, described in such passionate, positive, romantic terms you feel like you have the perfect fairytale and mythical princess in front of you. Snow White is indeed the "fiancee" Puss in Boots wants to have Boutonnet fall in love with - and it works as they go for a promenade into the fairy woods and the wonderful village, and Snow White's kindness and beauty and gentleness and purity touches Boutonnet right into his heart... Even better (or worse depending on how you see it) - Boutonnet realizes that this fairytale village is stuck into the perfect moment, into the apex of happiness. Snow-White doesn't know what Boutonnet is talking about when he talks of her wicked step-mother, Little Red Riding Hood is going into the woods with no idea of what a wood is, when Puss in Boots is asked about cemeteries he is horrified as nobody dies in this valley... He is happy at finding a world of ultimate happiness and perfection, but he is slightly worried about how things might unfold if the stories haven't truly happened yet...

Snow White invites Boutonnet to the village's grand feast at the castle - where music will be given by the titular Bremen musicians, and after this invitation (and before Puss in Boots prepares for him a new outfit), Boutonnet has a brief moment of lucidity in the euphoria. He realizes that it is all mad, that such a place cannot exist, that if he returns to the real-world his mother will be mad at him and he'll be taken for a crazy person - but this is also mixed with a deep sorrow within himself, as he is told nobody ages, nobody dies, everything is happy in the fairytale valley... The sorrow that, as it turns out there was a place where wishes came true and dream became reality, there was a wonderful place of chilhood love and eternal youth, but he got denied this place, people tricked him into believing it wasn't real and forced him into living a horrid life...

As dusk starts forming at the horizon, Boutonnet considers leaving the valley and returning to his car and fleeing the forest - but the forest now smells quite unpleasant, of damp humidity, and rotting wood, and all sort of other unpleasant smells of "reality", and he ultimately get smooth-talked again by Puss in Boots into joining the grand festivities of the night. And what grand festivities! A huge banquet with mouth-watering dishes one after another ; and a whole array of old, aristocratic dances for the ball ; and music, so much music ; and Boutonnet sits right next to Snow White and gets to enjoy a soft, discreet, blooming romance between the meal and the dances, surrounding by fantastical beauties and fabulous riches...

... But as the night advances, the guests starts looking a bit less happy, a bit more shameful, things get more quiet. Boutonnet looks around and upon seeing so much beauty can't help but ask: Where are the others? The villains, the wicked ones, with their iron teeth and blue beards and hooked noses and warts and crooked chins... He notices there is some horrible sounds seemingly coming from the palace's door - but Snow White pretends it is "Just the wind" as the Bremen musicians try to cover it up with their music... And yet it is not wind, Boutonnet hears it growing louder and louder. It is scratches, screeches, screams and howls, the sounds of beasts and madmen. Boutonnet asks for explanations, and Snow White ends up sadly telling him the truth (and Boutonnet for the first time feels her hands are as cold as snow):

Once upon a time, a long time ago, fairytales were as Boutonnet heard of them. Snow White feared that every item was poisoned, Little Red Riding Hood didn't care cross the woods because of the wolf, princesses and sheperdess kept being killed by dragons, while brave heroes a la Jack and the Little Tailor kept killing giants, trolls and other gargoyles - and overall it was a constant battle of mutilated limbs, beheaded corpses, spells thrown left and right and constant pyres to burn people. It became so bad that the two side, the heroes and the antagonists, the goods and the villains, gathered one day to sign a peace treaty because they were so exhausted of living a "life of fairytale"... And the pact was such: the good folks and the heroes could live in the valley by day peacefully, while the villains and monsters ruled over it by night. This is why today Hansel and Gretel can eat gingerbread houses without fear, and why the three little pigs build their home in whatever material they like, and why Little Red Riding Hood visits her grandma every day...

But outside? What Boutonnet is hearing at the door of the castle? Its the wild hunt of the villains: Snow White's wicked stepmother is there, and so is the Big Bad Wolf, and Baba Yaga, and the Bogeyman, and the Ogre and the Ogress, and Frau Trude, and all the others: the dragons, the witches, the wicked dwarves, the ghouls, the trolls, the cyclops, Père Fouettar and so many monsters...

Boutonnet, puzzled wonders: But... If they are all outside, unable to attack or touch the good folks and the heroes... How do they survive? What do they eat? What do they kill, harass, maim and scare? Do they turn onto each other?

And Snow-White, sorrowfully but still so charming and beautiful, confesses to him: Alas, my beloved... They feed of strangers.

And the fairytale "good folk", to preserve their peace, throw Boutonnet outside of the castle, into the claws of the monsters and witches and ogres, and he only has time to scream one thing - the same word the little child screamed in "The Child and the Spells" - Mommy!

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

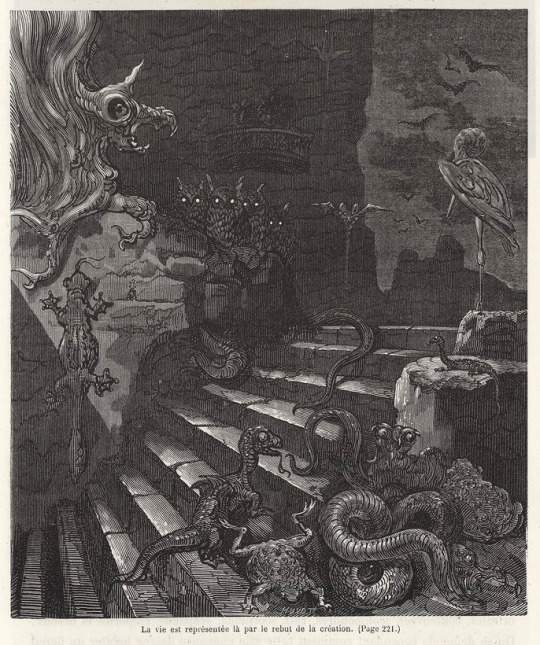

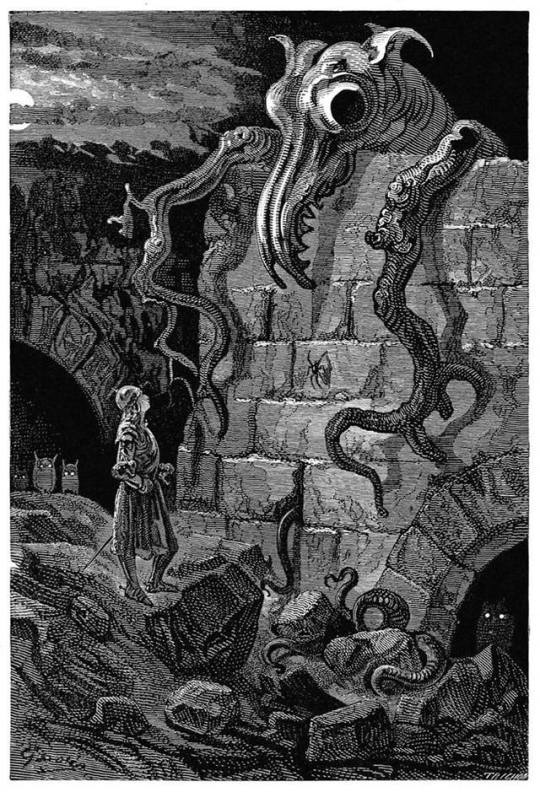

“Life is represented here by the worst of creation”.

Illustration by Gustave Dore for “La Legende de Croquemitaine”.

#Gustave Doré#La Légende de Croque-Mitaine#dragons#liz and the blue bird#toads#octopuses#owls#all sorts of critters#the absolute worst#happy halloween

182 notes

·

View notes

Photo

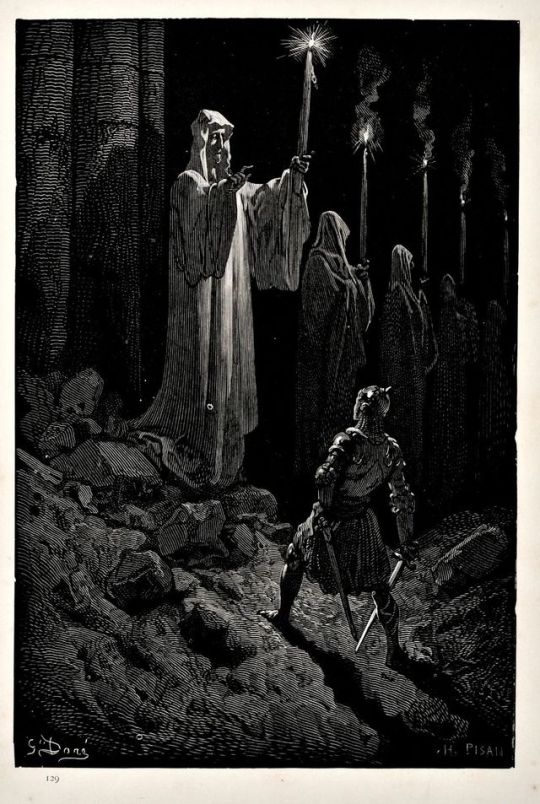

Gustave Doré’s illustrations for The Days of Chivalry: The Legend of Croquemitaine, by Ernest L’Epine.

#Gustave Doré#The Days of Chivalry: The Legend of Croquemitaine#Ernest L’Epine#vintage illustration#horror#black and white

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Physical description

Fairyland lustre jar and lid. Jar has bulbous body, with small neck and close fitting lid. The decoration is inspired by the illustrations of 'The Legend of Croquemitaine' by Gustave Doré, with woods, ghosts, fairies and goblins.

Place of Origin

Etruria (made)

Date

1916-1932 (made)

Artist/maker

Makeig-Jones, Daisy, born 1881 - died 1945 (designer)

Josiah Wedgwood and Sons (manufacturers)

Historical context note

Daisy Makeig-Jones's fascination with fairies, following such illustrators as Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac and the Danish artist, Kay Nielsen, proved very popular in the 1920s. Wedgwood have always produced a huge range of styles to capture different market tastes. The cosy drawing room and nursery atmosphere of the decoration of these works, and the monumental forms, contrast sharply with the modernist works being produced at Wedgwood's in the same period.

Targeting the luxury end of the market with these pieces, they represent one of Wedgwood's most extraordinary technical achievements in the ceramic industry. The richly coloured ornament of Fairyland Lustre was extremely popular throughout the 1920s as expensive collector's pieces. But by the 1930s the appeal of lustre was waning and the collapse of the American market had a noticable effect on the demand for ornamental wares. Fairyland was gradually phased out in the 1930s as Keith Murray and Norman Wilson were taken up. Fairyland was considered too expensive and old-fashioned.

[Susan McCormack, 'British Design at Home', p.113]

Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gustave Doré (1832–1883), The Fortress Of Fear, Illustration from 'The Days of Chivalry or the Legend of Croquemitaine' by Ernest Manuel l'Épine (1826–1893), translated by Tom Hood. Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1866.

177 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gustave Doré illustration for the 1866 book, The Days of Chivalry or the Legend of Croquemitaine.

How I love the no-holds barred horror factor of those old illustrations.

#illustration#gustave doré#1860s#19th century#chivalry#monsters#creatures#horror#tentacles#knight#fantasy

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

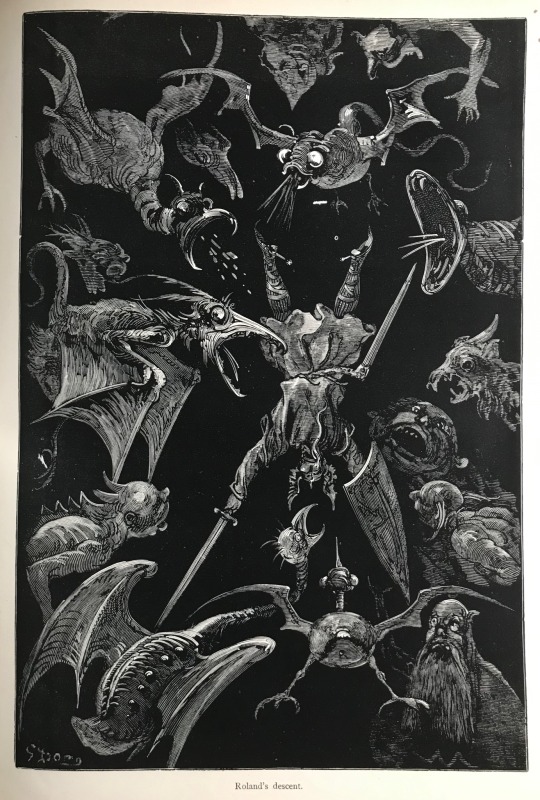

Roland's Descent (L'Épine's The Legend of Croquemitaine) by Gustave Doré

“The earth shook & gaped at Roland’s feet. He felt himself launched into space .. He heard around him the flapping of wings; it was a troop of afreets & djins.”

#roland#art#gustave doré#chivalry#chivalric romance#knight#knights#medieval#middle ages#franks#frankish#france#the legend of croquemitaine#history#paladin#mythology#ernest l'épine#ernest l'epine#french#germanic#europe#european#mythical creatures#monsters#afreets#jinn#djinn

113 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Shriek of Timidity. Gustave Doré illustration for “The days of chivalry, or the legend of Croquemitaine” (1866).

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gustave Doré illustration for the 1866 book, The Days of Chivalry or the Legend of Croquemitaine

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

~ Gustave Doré (1832–1883), Roland Rides Into Space, Illustration from 'The Days of Chivalry or the Legend of Croquemitaine' by Ernest Manuel l'Épine (1826–1893), translated by Tom Hood. Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1866. #Space #roland #cometsovcupid https://ift.tt/2NDfU0X

0 notes

Photo

Gustave Doré (1832–1883), The Gnarled Monster, Illustration from 'The Days of Chivalry or the Legend of Croquemitaine' by Ernest Manuel l'Épine (1826–1893), translated by Tom Hood. Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1866

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gustave Doré (1832–1883), Roland In Mahomet's Paradise, Illustration from 'The Days of Chivalry or the Legend of Croquemitaine' by Ernest Manuel l'Épine (1826–1893), translated by Tom Hood. Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1866.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gustave Doré (1832–1883), Roland's Descent, Illustration from 'The Days of Chivalry or the Legend of Croquemitaine' by Ernest Manuel l'Épine (1826–1893), translated by Tom Hood. Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1866.

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Shriek of Timidity.

Gustave Doré illustration for The days of chivalry, or the legend of Croquemitaine (1866).

#illustration#gustave doré#1860s#19th century#chivalry#monsters#ghosts#frogs#creatures#horror#fantasy#scream

276 notes

·

View notes