#the battle of germantown

Text

Went to the Peter Wentz’s farm today, which was Washington’s HQ before and after the Battle of Germantown! Washington actually paid back the invoices given to him by the Wentz family, which is very kind of him considering he and his army of twenty somethings ate their food and slept in their house for several days. More importantly yada yada battles cool yeah there were POLKA DOTS. POLKA DOTS EVERYWHERE. The original wall even shows that the polka dots are historically accurate and were original to the house. They also have sheep and cows and it’s very scenic. Visit if you can!

#POLKA DOTS#I love it. I love it!#historical houses in PA are just so fun#historic homes#historic preservation#american revolution#the battle of germantown#the philadelphia campaign#amanda speaks#pennsylvania history#your local pennsylvanian here

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The misfortune which ensued": The defeat at Germantown [Part 1]

Saverio Xavier della Gatta, an eighteenth-century Neopolitan painter, painted this scene of the Battle of Germantown in 1782, possibly for a British officer. Courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution.

This was originally written in October 2016 when I was a research fellow at the Maryland State Archives. It has been reprinted from Academia.edu and my History Hermann WordPress blog.

On the morning of October 4, 1777, Continental troops encountered British forces, led by Lord William Howe, encamped at Germantown, Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia’s outskirts. George Washington believed that he had surprise on his side. [1] He had ordered his multiple divisions to march twenty miles from their camp at Perkeomen, with some of the soldiers having neither food or blankets. [2] Washington thought that if the British were defeated he could retake the Continental capital of Philadelphia and reverse his disaster at Brandywine.

Among the men who marched with Washington were 210 Marylanders, including many veterans of the Maryland 400. [3] The seven Maryland regiments, commanded by General John Sullivan, were at the lead of the Continental attack. After marching most of the night, like the rest of the Continental Army, they arrived at Chestnut Hill, three miles from Mount Airy, and encountered a British picket. [4] Later, Sullivan’s division advanced and fought British light infantry in a 15-20 minute clash in an orchard. [5] The Marylanders progressed on the road to Germantown, pushing down fences as they moved forward during this “very foggy morning.” [6] As Enoch Anderson of the Delaware Regiment described it, the scene became bloody in the thick fog:

“Bullets began to fly on both sides,–some were killed,–some wounded, but the order was to advance. We advanced in the line of the division,—the firing on both sides increased,—and what with the thickness of the air and the firing of guns, we could see but a little way before us.” [7]

As the battle moved forward, many Continentals fought at the house of Benjamin Chew, also called Cliveden. The Marylanders advanced upon a small breastwork in Germantown, leading to an intense fight with many lying dead, and they later captured British artillery. [8] Later on, Sullivan ordered the Marylanders, within 400 or 500 yards of the stone house, to retreat since this obstacle had stopped their advance. [9] In response to the hundred or so British troops who came out of the house and a British advance from Lord Charles Cornwallis‘s reinforcements, some Marylanders fired a volley in response. After a British officer was killed, they did not pursue Sullivan’s men. When the smoke cleared, Colonel John Hoskins Stone and General Uriah Forest were wounded while two Marylanders were missing. [10]

Regiments from New Jersey, Connecticut, North Carolina, Virginia, and Pennsylvania also fought in the battle.��Like the Marylanders, these Continentals were initially successful in pushing back the British. [11] They were even successful against the Hessian Jägerkorps who had soundly defeated them at the Battle of Brandywine, 24 days earlier. [12] As George Washington recounted, the Continental troops were part of his plan to flank the British, advancing at sunrise, but that they

“retreated a considerable distance, having previously thrown a party into Mr Chews House, who were in a situation not to be easily forced, and had it in their power from the Windows to give us no small annoyance, and in a great measure to obstruct our advance…The Morning was extremely foggy, which prevented our improving the advantages we gained so well, as we should otherwise have done. This circumstance…obliged us to act with more caution and less expedition than we could have wished, and gave the Enemy time to recover from the effects of our first impression…It also occasioned them [the Continentals] to mistake One another for the Enemy, which, I believe, more than any thing else contributed to the misfortune which ensued.” [13]

Clearly, the successes of these Continentals were reversed because they attempted to take the well-defended stone house, which was “shot to pieces” in the intense fighting and friendly fire. Some, such as Connecticut Lieutenant James Morris III recalled that in the “memorable battle of Germantown,” the Continental Army’s victory “in the outsetting seemed to perch on our standards.” [14] He also wrote that the day’s success turned against them due to, in his view, the “misconduct” of General Adam Stephen and “undisciplined” soldiers scattering.

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#the battle of germantown#revolutionary war#american revolution#british victory#muskets#military history#us history

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello ! How many times was Laurens injured during the war ?

Five confirmed times;

Battle of Brandywine — Laurens suffered an ankle injury due to a musketball.

Battle of Germantown — Laurens had been shot through the “fleshy Part” of his right and dominant shoulder earlier in the battle. So, he had continued to fight with his aide riband wrapped around his arm and his sword in his left and non-dominant hand. He also received “a Blow in his Side from a spent Ball,” that was a minor injury that only caused swelling.

Battle of Monmouth — Laurens suffered a bruised right shoulder from a musketball.

Battle of Coosawhatchie — Another shot in the right shoulder.

Battle of Combahee — It isn't known specifically where Laurens was shot, it is only confirmed to have been fatal, and he seems to have died almost immediately. If so, he was likely shot in the heart, head, or neck.

#amrev#american history#american revolution#historical john laurens#john laurens#history#battle of brandywine#battle of germantown#battle of monmouth#battle of coosawhatchie#battle of combahee#sincerely anonymous#queries#cicero's history lessons

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Laurens (WIA)

John Laurens a second before being shot in the shoulder.. Germantown!

#amrev#john laurens#18th century#lams#historical hamilton#germantown#battle#american revolutionary war#historical john laurens#stasia draws

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

basic white girl fall? no, more like philadelphia campaign of 1777 autumn.

#commentary with chlo#american revolution#amrev#american history#george washington#philadelphia#battle of brandywine#battle of germantown

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

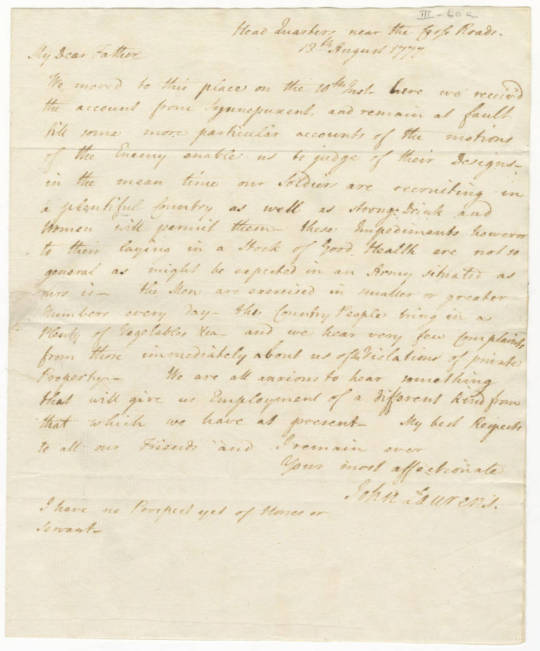

I present two letters, both written by John Laurens in 1777. You should notice that the handwriting in the letters does not match. So what's the difference? Laurens wrote the left letter with his left hand, and he wrote the right letter with his right hand.

The left letter is a letter from John Laurens to Henry Laurens dated October 15, 1777. John Laurens wrote this letter with his left hand as he had been wounded in the right shoulder during the Battle of Germantown on October 4, 1777. He had even used his uniform sash as a sling for his right arm:

If James can purchase a broad Green Ribband to serve as the Ensign of my Office, and will keep an account of what he lays out for me in this way I shall be obliged to him_ My old Sash rather disfigur’d by the heavy Rain which half drown’d us on our march to the Yellow Springs, (and which by the bye spoilt me a waistcoat and breeches of white Cloth and my uniform Coat, clouding them with the dye wash’d out of my hat) served me as a Sling in our retreat from German Town, and was render’d unfit for farther Service_

- John Laurens to Henry Laurens, in a letter dated November 6, 1777

On October 10, 1777, Henry Laurens wrote the following to his son John:

Your favour of the 7th. reached me yesterday Morning at the opening of Congress & as it contained some things new it afforded satisfaction to more than one_ a witty Gentleman from a southern Latitude doubted its having been writ with your left hand & undertook to prove it was dextrously executed_

While the letter pictured above is not the letter Henry was referring to here, we can presume that John was continuing to write with his left hand when he wrote the pictured letter about a week later.

The right letter is a letter from John Laurens to Henry Laurens dated August 13, 1777. This serves as a representation of John Laurens's normal handwriting, which is smoother, has a right slant, and has more spacing between lines.

I've previously discussed John Laurens's handedness, and some have speculated that he was a secret lefty (i.e., he was perhaps naturally left-handed but was trained to use his right hand due to negative perceptions of left-handedness during the time period). It's interesting to see what his handwriting actually looked like with his left hand. While his left-handed writing is not as smooth as his right-handed writing, there still seems to be some dexterity to it.

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Valley Forge

Valley Forge was the winter encampment of the Continental Army from 19 December 1777 until 18 June 1778, during one of the most difficult winters of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Despite being undersupplied, underfed, and plagued with disease, the Continental Army underwent significant training and reorganization at Valley Forge, emerging as a much more disciplined and effective fighting force.

The Philadelphia Campaign

On 19 December 1777, the exhausted and starving soldiers of the Continental Army staggered into Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, a location about 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Philadelphia at the confluence of the Valley Creek and the Schuylkill River. It had been a long and difficult campaign. Four months earlier, they had raced down from New Jersey to defend the US capital of Philadelphia from the British army, only to be outflanked and defeated at the Battle of Brandywine (11 September). Following their victory, the British captured Philadelphia, which the Second Continental Congress had only just evacuated. The Continental Army regrouped and, on 4 October, retaliated with a surprise attack on a British garrison at the Battle of Germantown. Although the assault initially got off to a good start, a thick fog caused cohesion between American military units to break down, and the attack quickly lost momentum. When the British counterattacked, the undertrained Continental soldiers broke and fled. For the next two months, the two armies nervously maneuvered around one another. Although several bloody skirmishes were fought, neither side was eager to provoke another major battle.

Gradually, the temperatures dropped, and the bitter December winds signaled that it was time to suspend the campaign and enter winter quarters. The British army moved into Philadelphia, where the officers settled into the abandoned homes of the city's Patriot leaders and spent the winter attending lavish dinners, dancing at elegant balls, and courting Loyalist women. The Continental Army, meanwhile, marched to Valley Forge. The spot had been carefully chosen by the American commander-in-chief, General George Washington, for several reasons. First, its proximity to Philadelphia would allow the Americans to keep a close eye on the British army; attempts by the British to raid the surrounding Pennsylvanian countryside or to march for the town of York, the temporary seat of the Continental Congress, could quickly be challenged. Second, an encampment at Valley Forge would be easy to defend. The camp itself was to be situated on a large plateau surrounded by a series of hills and dense forests, creating a sort of natural fortress. Lastly, the location was beneficial because it was close to a supply of fresh water from the Valley Creek and Schuylkill River, and the abundance of nearby trees could easily be cut down for fuel or to build shelters.

Over 11,000 Continental soldiers filed into Valley Forge on that December day, accompanied by 500 women and children. They were certainly a disheveled lot. The many marches and countermarches they had needed to perform in the last several months had worn down their footwear; now, an estimated one out of every three Continental soldiers went entirely without shoes. Additionally, many soldiers lacked adequate coats to protect against the elements, particularly the incessant rain that had been falling all autumn. Many men owned only one shirt, while others did not even have a single shirt at all. It is unsurprising then that many of these exposed soldiers were already ill when they arrived at Valley Forge; out of the 11,000 men that arrived, only 8,200 were fit for duty.

The situation was made worse by a dangerous lack of food. At the beginning of the Valley Forge encampment, the army's commissary only had 25 barrels of flour, a small supply of salt pork, and no other stores of meat or fish. A lack of sufficient food and clothing was fairly typical of the army's supply department, which had often performed below expectations since its founding in 1775, but the chaos of the recent campaign had only made things worse. In its hurried evacuation from Philadelphia, Congress had failed to ensure the army's supply chain would remain unbroken, thereby contributing to the bareness of the army's food and clothing stores. Thus, it was clear from the start that the coming winter would be a challenging one.

Continue reading...

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death of John Laurens: A Summarized Account of August 26th and 27th, 1782

Sources and links to said sources will be listed at the end of this post in Chicago format. This post is purely for educational purposes and is not meant to be used in any research, citations, or criticism of other works or individuals. Please refer back to the list of sources if you intend to use this material in a similar fashion.

What happened on the evening of August 26th, 1782, and the morning following? This was the eve of the death of John Laurens and the events that would occur on the morning on the 27th would go on to be recognized as incomplete, like a puzzle missing some pieces. However, after some recent diving into the topic and looking into letters from Nathanael Greene, Mordecai Gist, and others describing Laurens’ “gallant fall”, I will be presenting a summary and compilation of this information to paint an unfortunate night in an incomplete fashion. There are still things that remain unclear to me, but this may provide some clarity on those who are unaware of what happened.

To set the scene, Tar Bluff, the Combahee Ferry, and the Combahee River in South Carolina is a mix of two sets of scenery in the present day. Nearer to the river and the flatter land, it is thick marshland and difficult to travel through. This is why the ferry was so necessary and useful and likely why the British commandeered it. The drier land higher than the marsh was primarily deciduous and coniferous trees that covered muddy and sandy ground with leaves and pine needles. Today, the area is very dense and overgrown along the riverbanks due to the nature of the region and its climate. It is uncertain what the weather at the time of this engagement might have been, but by referring back to lunar calendars, it is deductible that the night of the 26th-27th was a waning gibbous; the moon would be mostly full but not entirely so and would continue to cast less light in the coming days. Furthermore, it is important to mention that the location that is mentioned that Laurens had been staying and later buried at was roughly thirty-seven miles from where the engagement against the Regulars occurred. Gist mentioned that the main encampment he had made was twelve miles north of Chehaw Neck and roughly fifty miles away from Greene's main headquarters outside of Charleston.

The British were commanded by Major William Brereton and reportedly one-hundred and forty men strong consisting of the British 64th Regiment and volunteers from the British 17th Regiment. The 64th Regiment had been in other engagements where Laurens was present also, including the battles of Brandywine and Germantown as well as the much later and much more influential Siege of Charleston in 1780. This was not the end of the 64th engaging against Laurens as they were reportedly at the Siege of Yorktown and surrendered with the body of men under General Cornwallis’s command.

On the days leading up to the 27th, Gist remarked that an enemy fleet of British regulars had taken the command of the Combahee Ferry and both sides had been locked in a stalemate regarding the waters due to the circumstances: the Patriots could not engage the enemy due to the ships in the river, and the Regulars could not get their supplies north and across the Combahee because the Patriots were patrolling the area. Gist, with a combined might of over three-hundred men consisting of the 3rd and 4th Virginia Regiments under the command of Colonel Baylor, the Delaware Regiment, one-hundred infantry of the line commanded by Major Beale, the entirety of the command under Lt. Col. John Laurens, and all of which was under the command of General Gist.

It’s important to mention before continuing that despite much research into the matter of Laurens’ illness on the evening and morning of the 26th and 27th, myself and other partners in researching [the esteemed @pr0fess0r-b1tch] could not find a reputable source mentioning directly that John Laurens was ill. Gregory D. Massey does not explicitly mention a source in his book, but instead says,

“From his sickbed, Laurens learned of Gist’s orders. He forwarded the latest news to headquarters and added a query…”

Other sources we found mentioned that many of the northern regiments and men were falling ill, even some doctors themselves, but there is not a primary source that lists that Laurens was sick or bedridden aside from Massey and the sources that pull from his accounts including the Wikipedia of Laurens and the American Battlefield Trust. Because of this oversight, I am choosing to redact the concept of Laurens’ illness until otherwise proven by a primary source whether it be a letter or other statements.

Laurens was given the command of the men under Gist by General Greene and despite not being well-liked by the men who were formerly under Light Horse Harry Lee’s command, it was theoretically remedied by the intermediary of Major Beale. On the night of the 26th, Brigadier General Mordecai Gist recounted in a letter to Major General Nathanael Greene that “Lt. Col. Laurens arrived in the intermediate time, that solicited the direction and command at that post”, the post being that Gist had ordered an earthworks to be constructed at Chehaw Neck to “annoy their shipping on their return”. In the evening that Laurens took command and oversight, Gist sent fifty men to be under his command with some Matrosses and a Howitzer. Laurens, in command of these men, were stationed on the northern bank of the river.

The commanding officer of the British, Major Brereton, evidently received information of this movement of the Howitzer to the earthworks within the day that such a motion was ordered. The quick intelligence may allude to an inside source that the British had or a matter of good reconnaissance, but Major Brereton left in the ships at two in the morning and “dropped silently down the river”, according to General Gist. These movements went undiscovered until four in the morning when patrols noticed and alerted the extended body led by Laurens. It is stated that the troops were then “put into motion to prevent their landing”. Gist then mentions that before he could arrive and defend the efforts, the British had successfully landed and engaged Laurens directly. The men scattered when Laurens fell, but Gist regathered them within the quarter mile, following which the enemy forces reboarded the boats and left.

According to a Delaware Captain, William McKennan, under Laurens’ command, Laurens was “anxious to attack the enemy” before the main body and Gist’s reinforcements arrived. McKennan says,

“being in his native state, and at the head of troops…were sufficient to enable him to gain a laurel for his brow…but wanted to do all himself, and have all the honor.”

After Laurens had been injured in three other battles, Brandywine, Germantown, and Coosawatchie, and having his pride wounded at losses most notably the loss of Charleston in 1780, it would be understandable that he would be so willing to return to the fight for his nation after being detached and moved frequently in the later years of the war. McKennan’s account states in the same paragraph that Laurens was killed in the first volley of the attack by Brereton’s men. Some sources say that Laurens was upon a horse when he fell and was mortally wounded, but others suggest that he may have merely been standing in the enemy fire. All appear to agree that Laurens was one of the first victims of the enemy volleys. Whether he died upon the first impact is unknown, but his body was abandoned until Gist could regroup the men and return to the site to gather an understanding of who was killed and wounded in the action.

Following the death of a notable officer, statesman, and diplomat, many men would come to regard Laurens as an incredibly accomplished and noteworthy young man and officer. Greene writes in an August 29th letter to General Washington,

“Colo. Laurens’s fall is glorious, but his fate is much to be lamented. Your Excellency has lost a valuable Aid de Camp, the Army a brave Officer, and the public a worthy and patriotic Citizen.”

In “The Delaware Regiment in the Revolution” where McKennan’s recollection of events can be found, it states,

“In the fall and death of Colonel John La[urens], the army lost one of its brightest ornaments, his country one of its most devoted patriots, his native State one of its most amiable and honored sons, and the Delaware detachment a father, brother, and friend.”

Gist’s letter to Greene on the day of the 27th says that “that brave and gallant officer fell, much regretted and lamented.” Alexander Hamilton, a fellow aide, close friend, and alleged lover, remarks in a letter to General Greene on October the 12th, 1782, over a month since Laurens’ passing,

“I feel the deepest affliction at the news we have just received of the loss of our dear and inestimable friend Laurens. His career of virtue is at an end. How strangely are human affairs conducted, that so many excellent qualities could not ensure a more happy fate? The world will feel the loss of a man who has left few like him behind, and America of a citizen whose heart realized that patriotism of which others only talk. I feel the loss of a friend I truly and most tenderly loved, and one of a very small number.”

As for how his own father, Henry Laurens, reacted to the news, a pair of letters and brief segments from them may very well put it into perspective of how not only close friends, but a good number of men felt about the death of Laurens. On November 6th, 1782 from John Adams to Henry Laurens:

“I know not how to mention, the melancholly Intelligence by this Vessell, which affects you so tenderly.— I feel for you, more than I can or ought to express.— Our Country has lost its most promising Character, in a manner however, that was worthy of her Cause.— I can Say nothing more to you, but that you have much greater Reason to Say in this Case, as a Duke of ormond said of an Earl of Ossory. ‘I would not exchange my son for any living Son in the World.’”

In a return letter to Adams from Henry Laurens dated November 12th, 1782:

“My Country enjoins & condescends to desire, I must therefore, also at all hazards to myself obey & comply. Diffident as I am of my own Abilities, I shall as speedily as possible proceed & join my Colleagues. For the rest, the Wound is deep, but I apply to myself the consolation which I administered to the Father, of the Brave Colonel Parker. ‘Thank God I had a Son who dared to die in defence of his Country.’”

~~~

I would like to send a huge thank you to @butoridesvirescens for instigating this rabbit hole that we went down and @pr0fess0r-b1tch for being my research partner and assisting in transcriptions. I appreciate the work done by both of them.

Sources

“Combahee River .” Combahee River Battle Facts and Summary . Accessed February 20, 2024. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/combahee-river.

“From Alexander Hamilton to Major General Nathanael Greene, [12 October 1782],” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0090. [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 3, 1782–1786, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1962, pp. 183–184.]

“To George Washington from Nathanael Greene, 29 August 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-09304.

“From John Adams to Henry Laurens, 6 November 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-14-02-0013. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 14, October 1782–May 1783, ed. Gregg L. Lint, C. James Taylor, Hobson Woodward, Margaret A. Hogan, Mary T. Claffey, Sara B. Sikes, and Judith S. Graham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008, pp. 25–26.]

“To John Adams from Henry Laurens, 12 November 1782,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-14-02-0029. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 14, October 1782–May 1783, ed. Gregg L. Lint, C. James Taylor, Hobson Woodward, Margaret A. Hogan, Mary T. Claffey, Sara B. Sikes, and Judith S. Graham. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008, pp. 56–57.]

Bennett, C. P., and Wm. Hemphill Jones. “The Delaware Regiment in the Revolution.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 9, no. 4 (1886): 451–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20084730.

Cook, Hugh (1970). The North Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's). Famous Regiments. London: Leo Cooper.

George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Mordecai Gist to Nathanael Greene, with Copy; with Letter from William D. Beall on Casualties. 1782. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw431868/.

Johnson, William. 1822. Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Vol. II: 339.

Massey, Gregory D. 2015. John Laurens and the American Revolution. Columbia: University Of South Carolina Press. Pages 225-227.��

#john laurens#mordecai gist#nathanael greene#amrev#compilation#research#self researched#history#sources#american revolution#the fall of john laurens#august 27#william mckennan#gregory d. massey#alexander hamilton#john adams#henry laurens#“The Delaware Regiment in the Revolution” 1886#founders online#library of congress#summarized accounts

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's Achilles for the episode titles

Thanks for the ask! I had a feeling this one would be asked first haha.

Episode 9 of this hypothetical season would cover from August through October of 1777. The episode would center around John Laurens’ introduction into the plot and begin the subplot of he and Alexander’s relationship which would continue to develop through the rest of the season. This episode would feature among other things the battles of Brandywine and Germantown (both of which Laurens and Hamilton participated in—Laurens notably receiving an ankle injury in the former battle, and famously received another injury to the shoulder while trying to burn down the entrance to a house the British had holed themselves up in to attack from during the latter), that time Hamilton was pronounced dead in the Schuylkill River while on a mission to destroy supplies, and the fall of Philadelphia (the home of the Continental Congress) to the British. Chronologically, the episode would conclude with the aftermath of the Battle of Germantown (October 4th). What this aftermath looks like, I can’t say, as I haven’t gotten around to writing that section of TAI: Volume I yet, but I’m excited to get to writing those chapters. And I’d love to see them on screen someday.

#thanks for the ask!#the american icarus#TAI#alexander hamilton#john laurens#amrev#tv shows#writers on tumblr#amwriting#historical fiction

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grumblethorpe

Had a lovely day visiting the generational home of the Wisters, a Philadelphia family of merchants and Quakers. This was their summer residence in Germantown, built by John Wister in 1744, which stayed in the family for nearly two centuries. Originally known as "John Wister's Big House," it came to be known as Grumblethorpe in the 18th century.

My primary interest in the Wisters surrounds Sarah "Sally" Wister who wrote a journal in 1777-1778 during which many important events of the American Revolution took place - the battle of Germantown, the siege and reduction of the forts below Philadelphia, the surrender of Burgoyne, the maneuvers at Whitemarsh, the march to Valley Forge and winter encampment there, etc etc.

Sally's family fled their home on Market Street (in Philadelphia proper) for the Foulke Mansion in North Wales, where Sally wrote her journal. Meanwhile, the Germantown residence became a headquarters for British Brigadier-General James Agnew, who was shot during the Battle of Germantown. He was taken back to the Wister house and bled to death in the parlor. Apparently his blood stains are still visible in the wooden floor (pictured above - I think it's more likely whatever the servants used to scrub it clean).

Also pictured is the original silhouette of Sally Wister, the face of the main house, and the Wister library. Because the house remained in the family for so long, passing through relatively few hands over the centuries, much of the property retains its original artifacts.

This is a very peaceful place nearly untouched by time. I highly, highly recommend visiting Grumblethorpe for anyone near Philadelphia with an interest in the American Revolution.

#this is so disorganized#i'll add more later#I love the wisters#especially sally#sarah!!!#american revolution#germantown#philadelphia#colonial america

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Going to write a book about the Philadelphia Campaign and title it “Eating from One Plate in the Polka Dot Room: the story of Washington’s rise and fall after the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown”

#amanda speaks#I’ve had this in my drafts for months#happy Germantown day to me#the philadelphia campaign#the battle of germantown

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The misfortune which ensued": The defeat at Germantown [Part 3]

Continued from Part 2

This was originally written in October 2016 when I was a research fellow at the Maryland State Archives. It has been reprinted from Academia.edu and my History Hermann WordPress blog.

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] “To George Washington from Brigadier General Anthony Wayne, 23 April 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; The Annual Register, 135. The Annual Register says that British patrols found the Continentals by 3:00 in the morning, so their attack was no surprise.

[2] Mark Andrew Tacyn, “’To the End:’ The First Maryland Regiment and the American Revolution” (PhD diss., University of Maryland College Park, 1999), 143-144; Pension of James Morris, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land-Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 1771, pension number W. 2035. Courtesy of Fold3.com; James Morris, Memoirs of James Morris of South Farms in Litchfield (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933), 18; Pension of Jacob Armstrong, Revolutionary War Pensions, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, pension number S.22090, roll 0075. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Stanley Weintraub, Iron Tears: America’s Battle for Freedom, Britain’s Quagmire: 1775-1783 (New York: Free Press, 2005), 116-117; Andrew O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Command During the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire (London: One World Publications, 2013), 109; “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” Maryland Historical Magazine June 1908. Vol. 3, no.2, 110; John Dwight Kilbourne, A Short History of the Maryland Line in the Continental Army (Baltimore: Society of Cincinnati of Maryland, 1992), 14; “From George Washington to Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, 25 September 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Pension of James Morris, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land-Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 1771, pension number W. 2035. Courtesy of Fold3.com; James Morris, Memoirs of James Morris of South Farms in Litchfield (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1933), 18; “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 18 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016. The reference to no food or blanket specifically refers to James Morris of Connecticut. Washington’s headquarters was on Pennibecker’s Mill on the Skippack Road from September 26-29 and October 4 to October 8th, 1777. The Continental Army had camped at Chester throughout late September, but Morris says they camped near the Leni River. However, a river of this name does not exist, so he may have meant a branch off the Schuykill River or maybe the Delaware River, since the Leni-Lenape indigenous group lived on the river.

[3] “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 18 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Page, 11 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Major General William Heath, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; C.H. Lesser, The Sinews of Independence, Monthly Strength Reports of the Continental Army (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 80.

[4] Tacyn, 4, 115, 144; Enoch Anderson, Personal Recollections of Captain Enoch Anderson: Eyewitness Accounts of the American Revolution (New York: New York Times & Arno Press, 1971), 44; “From George Washington to Major General William Heath, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[5] Tacyn, 145.

[6] Anderson, 45.

[7] Anderson, 45.

[8] Anderson, 45.

[9] Tacyn, 145-146; Anderson, 45; “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110-111.

[10] Tacyn, 15, 209-210, 289, 291; Pension of James Morris, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty Land-Warrant Application Files, National Archives, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 1408, pension number W. 11929. Courtesy of Fold3.com. Thomas Carvin and James Reynolds were said to be missing after the battle. Reportedly, a Marylander named Elisha Jarvis was ordered by William Smallwood to guard the baggage train at the Battle of Germantown.

[11] Thomas Thorleifur Sobol, “William Maxwell, New Jersey’s Hard Fighting General,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 15, 2016. Accessed October 3, 2016; “From George Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., 7 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[12] David Ross, The Hessian Jagerkorps in New York and Pennsylvania, 1776-1777, Journal of the American Revolution, May 14, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2016.

[13] “From George Washington to John Hancock, 5 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[14] Pension of James Morris; Morris, 18-19.

[15] Don N. Hagist, “Who killed General Agnew? Not Hans Boyer,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 17, 2016. Accessed October 3, 2016; Don N. Hagist, “Martin Hurley’s Last Charge,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 14, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2016; John Rees, “War as Waiter: Soldier Servants,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 28, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2016; Thomas Verenna, “20 Terrifying Revolutionary War Soldier Experiences,” Journal of the American Revolution, April 24, 2015. Accessed October 3, 2016; Thomas Verenna, “Explaining Pennsylvania’s Militia,” Journal of the American Revolution, June 17, 2014. Accessed October 3, 2016; “General Orders, 11 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016. Richard St. George and Martin Hurley of the British army were wounded and James Agnew, a British general, was killed.

[16] Pension of Jacob Armstrong; The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1777 (4th Edition, London: J. Dosley, 1794), 129-130; Sir George Otto Trevelyan, The American Revolution: Saratoga and Brandywine, Valley Forge, England and France at War, Vol. 4 (London: Longmans Greens Co., 1920), 275; O’Shaughnessy, 110; “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110-111; Kilbourne, 17, 19; “From George Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., 7 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[17] “From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[18] “From George Washington to Major General William Heath, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Page, 11 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 18 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Hancock, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[19] “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 18 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[20] “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 111; Anderson, 45-46.

[21] “From George Washington to John Hancock, 5 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., 7 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Hancock, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Major General William Heath, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Page, 11 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 18 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016. In his letters he said that Grant was wounded while Nash (died after the battle from wounds) and Agnew were killed.

[22] Pension of James Morris; Morris, 19.

[23] “General Orders, 5 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Annual Register, 136.

[24] “From George Washington to John Hancock, 5 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Major John Clark, Jr., 6 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., 7 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Hancock, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Major General Israel Putnam, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Major General William Heath, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[25] “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 18 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Major John Clark, Jr., 6 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, Sr., 7 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Hancock, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Major General Israel Putnam, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, 9 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Page, 11 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Captain Henry Lee, Jr., 15 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Augustine Washington, 18 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; Annual Register, 137. One letter says fifty British were killed and another says fifty-seven. The British Annual Register confirms that Nash was killed.

[26] Annual Register, 136-137.

[27] Pension of James Morris; Morris, 19.

[28] Pension of James Morris; Morris, 19-25; “To George Washington from Pelatiah Webster, 19 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Thomas McKean, 8 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016,

[29] Pension of James Morris, Morris, 23-29, 31; “To George Washington from Captain Henry Lee, Jr., 9 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Lieutenant Colonel Persifor Frazer, 9 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Pelatiah Webster, 19 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016. He also said that he was then shipped to Philadelphia where he served a prisoner on Long Island as a farm laborer until May 1781.

[30] “To John Adams from Joseph Ward, 9 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[31] “The Committee for Foreign Affairs to the American Commissioners, 6[–9] October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To Benjamin Franklin from the Massachusetts Board of War, 24 October 1777: résumé,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[32] “To George Washington from Major General John Sullivan, 25 November 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “Major General John Sullivan’s Opinion, 29 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[33] “To John Adams from Benjamin Rush, 13 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “General Orders, 19 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Major General Nathanael Greene, 24 November 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “General Orders, 22 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Captain Edward Vail, 22 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “General Orders, 13 June 1778,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from William Gordon, 25 February 1778,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Major General Adam Stephen, 9 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[34] Trevelyan, 249; O’Shaughnessy, 111; Christopher Hibbert, George III: A Personal History (New York: Basic Books, 1998), 154-155; “From John Adams to James Lovell, 26 July 1778,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[35] Annual Register, 137-141.

[36] Anderson, 53; Tacyn, 146; Thomas Thorleifur Sobol, “William Maxwell, New Jersey’s Hard Fighting General,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 15, 2016. Accessed October 3, 2016; “Journal of Captain William Beatty 1776-1781,” 110; Kilbourne, 14; “From George Washington to George Clinton, 15 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to Major General Israel Putnam, 15 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Major John Clark, Jr., 27 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Brigadier General Henry Knox, 26 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “To George Washington from Major John Clark, Jr., 6 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016; “From George Washington to John Hancock, 7 October 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives, last modified July 12, 2016.

[37] Journal and Correspondence of the Council of Maryland, April 1, 1778 through October 26, 1779 Archives of Maryland Online Vol. 21, 118; Kilbourne, 21-22, 24-27, 29-30, 31, 33; Tacyn, 241. Some argue that in the battle of Eutaw Springs parts of the battle of Germantown were repeated.

#battle of germantown#revolutionary war#american revolution#british victory#military history#us history#notes

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ahem- in honor of the anniversary for the battle of Germantown;

John Laurens was not trying to burn down a fucking stone building, he was trying to burn down the wooden door.

#Yes he was a himbo but not a moron#I hate that the Hamilton fandom spread this dumb ass myth around while taking away all the necessary context#amrev#american history#american revolution#john laurens#historical john laurens#Germantown#battle of Germantown#history#rambles

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two of Us

A brief intro: this was what I sort of consider my first washette writing expect it's just detailed notes about how I wanted each chapter to go

Fandom/Tags: Hamilton, George Washington/Lafayette, draft, historically accurate

Chapter one- the dinner party! Laf is a brand new (honorary) major general and meets George! Later that night, George invites him to live with him and become a part of his military family

Chapter two- Lafayette gets very excited and is dressed and packed to the nines. Then he shows up and everything’s a shit show but Laf is like, it’s cool. I came here to learn not to teach. And George is like ❤️.

Chapter three- Army meeting thing next day. Looks like Howe is just going to attack Charleston- not Philadelphia. Next day- oh shit. He’s headed this way! Prepare for battle!!

Chapter four- Brandywine. Here we go. George, please let me fight. George (not thinking or in the mood to argue) yeah ok sure, wait. Too late. Lafayette goes in and is pretty awesome. Meets up with George and he’s like, your leg! Laf like, pffffh. I’m fine. Shit. And George is like: we’re getting that dressed immediately! A few days later he’s transported upriver but before that, he and George have a nice chat. Right before George shows up, he’s writing to Adrienne. Then after talk George writes report to Hancock

Chapter five- Laf has been moved to Bethlehem. Germantown happens and it’s bad. He wants to go and fight but George sends a letter urging him to wait. Laf writes a bunch of letters to France like, support America!!! Yay Saratoga! Laf gets very excited and writes to George like: for the love of God let me fight. Then when he doesn’t hear anything, he gets up and goes even though he can’t wear a boot to Whitemarsh where he is. Friends with Greene.

Chapter six- Valley Forge. Also dead Henrietta. He has a gut(cot??) to himself. People want George gone cause valley forge sucks. Established board of war. Good gay sweet flirts. Comfort.

Chapter seven- the gang is pissed at congress. (Oh my god, Alex. They would be so GOOD for each other. Greene’s over here like: that’s what I said!) they have long talk everyday! Still trying to hurt Washington, they appoint Laf for an expedition they know will fail and will give him the same rank as George. Gil is pissed and like, George! Look at this shit!! Anyway, he arranges some stuff, heads up to Canada and there’s literally nothing! He is super pissed and writes to Henry Laurens and then to George. George writes back a message of consolation. Laf just wants to be with him and vice versa and valley forge has realllllly gone to shit now.

Chapter eight- it’s from George perspective at valley forge!! Half the men are dead. He’s worried about Gil and just needs him in general. Need more details for George chapter but will end with letter from Gil saying he’s coming back and all is well again! Yay!

Chapter nine- Greene and Steubem have saved the day! Gil gets to meet Martha! Stuff is more organized and George has appointed Laf head of foreign affairs, which he does very well with. He’s helping George with a lot of training and clothing his own calvary. Also he’s being a sweetheart. May 1st, George gets a letter that he reads out loud to Gil. The treaty of France has been signed! Gil gets so excited that he kisses George and he’s crying! But he kinda brushes it off. Everyone is celebrating and super excited at valley forge. THEN Gil finds out Henrietta is dead. And he has to go out and pretend he’s happy but that night he talks to George and he comforts him and they cuddle.

Chapter ten- woes vs woahs

So, war is over and yay and stuff! But for some reason Laf is sad and upset and emotional

And he’s confused cause he should be happy

He also doesn’t realize that George has been spending more time with him than usual and that all the extra time with George has been breaking his heart even more (and George is feeling the same but instead he wishes to spend all his time with Gil)

Then there’s a nice party with an orchestra you know

And Laf just wants to leave because he’s had enough of this talk

And the whole night George has wanted to be with him but so many people have been bombarding him with questions and comments, and he can’t be rude, but he can’t hardly take two steps without having to talk to someone but he just wants to get to Gil because he sees how upset he is from across the room!

Then George eventually makes it over and is like, “I can tell something’s wrong, what happened?”

And Gil’s like, “Is it that obvious?”

And George kinda half-heartedly jokes (aw. Look at him trying to joke for Gil’s sake) like, “I don’t think so, I think I just know you pretty well.”

And Gil’s just kinda looking at him, smiling, and wishing that he could be alone with him for hours and just lay in bed next to him talking until the sun rose but instead what he says is something like:

“Oh please, don’t worry for my sake. It’s nothing. You need to enjoy this wonderful occasion and forget all about silly old me.” because HE’S CONFUSED (And doesn’t think he can handle George being so kind and sweet to him at this moment as it is making his heart ache more than it ever has before)

And George is like: “Nonsense! I will worry about you all I want because I care about you and you mean so much to me and your happiness brings me joy.”

And then he puts his hand on his neck and like, in his curly hair and Gil really loves the gesture (it’s not unusual, it’s the first thing he does when comforting Laf) but then his heart starts beating like crazy and he’s shaking a little and he has to pull away because his head was spinning and that whole thing felt embarrassing in public (because George was over here looking into his eyes and he just couldn’t take it at that momentXD) and he’s just looking at the ground

George is kinda confused because Laf’s never done that before and Laf feels a little guilty about it but he’s still kinda shook up and George is like, “I’m sorry Gilbert, it wasn’t my intention to make you uncomfortable.”

And George is kinda at a loss for words as he realizes that Gil seriously upset

And Gilbert, feeling guilty and emotional says something like, “I’m sorry but I just need you to leave me alone right now, please leave.”

And you know, Gil doesn’t really want George to leave, he just wants his overwhelming feelings to be quiet and let him go and thinks that temporarily removing George will accomplish that

And George, knowing Laf very well, knows that he hates being alone when he is distraught like this and is confused at the request, wishing to stay and comfort him (and enjoy every last second they had together before his heart was ripped in half) so he tries to assert his place and says that he will stay with him no matter what

But Laf just kinda snaps at George for a moment telling him to, “Leave me be!” While fighting back tears (Because why does he have to be so perfect and know exactly what he needs?? He can’t stand his kindness because he’s trying to forget him and not kiss him with the force of a thousand waterfallsXDXD)

(oh. That’s why this is making me so sad. That makes a lot of sense.)

And George fucking KNOWS that Gil, deep down wants him to stay (why is he crying?!? Don’t cry!!! Omg I love you so much!!!! Oh my god. I love him. That makes a lot of sense.) but he can’t be cruel when Laf has asked him to leave twice now even though it breaks his heart

So he simply takes a deep breath and slowly walks away

Laf is half-inclined to run after him, kiss him and confess everything and to apologize for his behavior but (luckily) George was lost in the crowd before he could

Now Laf really wanted to go back to his quarters and pretend that none of this happened. Pretend he didn’t finally make sense of the storm in him. Pretend he didn’t want to start singing on the rooftop that he was in love because that love was futile and impossible to pursue, especially when they were almost out of time.

So he left, and moped in his room

He’s awake (and balling) for hours and obviously can’t sleep because he has so much on his mind but then he hears a knock on his door that scares him half to death and then hears a familiar, “Lafayette, can I come in?”

Just for a second Laf doesn’t say anything but then George says, “I heard you Gilbert I know you’re awake *sigh* just please let me in.”

Lafayette says a little “ok” and George lets himself in

After his wallowing all night he was actually very very happy to see George and his presence was just the one he needed after an extremely emotionally exhausting night, and a small part is begging him to leave but Laf is a little weaker and listening to his (ridiculously in love) heart over his brain

George stands there awkwardly at the door and begins to speak but is then interrupted by Laf patting the bed next to him and George immediately obliges, unable to keep himself from Gilbert and as he sits down Gil wraps George up in a big hug and he hugs back very intensely with all the gd emotions they have to give

Gil can hear George sniffle and feels tears on his shoulder (Gil would be crying, but like, he’s been doing that all night and is so tired)

After a moment (and after George stops crying) Laf is like, “George. I’m so so sorry about tonight.”

And George is immediately like, “You think that’s what I’m upset about? I’ve been so worried about you all night, you weren’t acting like yourself at all. I’m not mad in the slightest, I’m worried about you.”

They part, but not very far and they’re holding hands

Gil says: “I’m okay now. Or at least better than before.” (after a moment). “Thank you. For coming here in the middle of the night, to comfort me, to check on me. You didn’t have to. But thank you.

And George’s heart is just melting as he’s like, “You may not understand Gilbert, but I simply had to come see you. I believe I didn’t have a choice in the matter, andI would so much more for you, with no thanks if it meant I could make you happy and be by your side.” And he kisses Gil’s knuckles and Laf is practically having a heart attack with how much he loves this man and George is trying his goddamn hardest not to kiss him

George: “Lafayette, there is something that I need to tell you before this night is over. Something that’s been gnawing away at me for such a long time now *deep breath*”

Gil is sitting still, stopped breathing, waiting to hear the words he had been dreaming of (that sounds cheesy)

George suddenly pulls Gilbert in for a big hug (cause he’s kinda scared to see the look on his face when he says what he needs to say) and with a quiet voice, proclaims his love for Gilbert

And Gil, although at first thrown off by the hug, hugs him back with a big smile on his face and small tears falling from his eyes and he says: “George, I love you too. I love you too!”

Then they’re both happy crying and giggling and hugging the daylights out of each other until they’ve just kind of exhausted themselves and part

And with their faces so close together, hearts on their chest, tears in their eyes, George places his hand on Gil’s cheek, completely taken aback by his beauty, and they finally kiss! And it’s great. And they pretty much just make out and chill and chat til the sun comes up (but only kissing because like, that whole night was stressful and they’re both tired, leave them alone.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By the way, if you want a great way to demonstrate the Constitution isn’t infallible, here’s one for you:

When it was signed—in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—Alexander Hamilton, who as we all know thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda was from next-door-neighbor New York, put down the names of the states each signatory was representing.

Alexander Hamilton, who lived his whole adult life only 82 miles from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; who was signing the Constitution in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; who fought in the battles of Brandytown and Germantown in Pennsylvania; who was George Washington’s second in command and had to know the entire area and its movements like the back of his hand—

—wrote down that Benjamin Franklin was from “Pensylvania.”

THEY COULDN’T EVEN GET THE SPELLING OF THE STATES RIGHT AND WE BELIEVE THEY KNEW HOW TO RUN A COUNTRY?!

Anyway, if you want even more of this nonsense, it’s here. The Constitution is FULL of errors. Forget “not covering everything,” it couldn’t even cover itself.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 Days of La Fayette – Day 16: François-Louis Teissèdre de Fleury

Today’s aide-de-camp is François-Louis Teissèdre de Fleury, Marquis de Fleury and son of François Teisseydre de Fleury. He was born in 1749 and first served in the French army as a volunteer from 1768 onwards. In 1772 he was made sous-aide-major in the Rouergue Regiment.

While La Fayette and his group of fellow travelers are certainly among the most famous foreign personal in the continental army, their idea was by no means novel. There were several groups of Frenchman that tried one way or another to join the War in America (and for one reason or another). Fleury was part of such a group - and he was one of the, comparatively speaking, few successful ones.

He was made a Captain of Enginers by the Continental Congress on May 22, 1777 and was awarded 50 Dollar for his travelling expenses. William Heath wrote to George Washington on April 26, 1777:

The Three appear to be Officers of Abilities—They inform me that Mr Dean promised them that their Expences should be born to Philadelphia &c.—I must confess I scarcely know what to do with them, & wish Direction, I have advanced to Col. Conway, as advance pay 150 Dollars to enable him to proceed to Philadelphia—And to Capt. Lewis Fleury 50 Dollars—The latter is engaged as a Capt. Engineer.

“To George Washington from Major General William Heath, 26 April 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 9, 28 March 1777 – 10 June 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 277–280.] (12/16/2022)

He was initially assigned to a corps of rifleman but soon got promoted and re-assigned after he fought with distinction at the Battle of Brandywine, where his horse was shot from under him. A Boston newspaper wrote on December 4, 1777:

The Chevalier du Plessis, who is one of General Knox’s Family, had three Balls thro’ his Hat. Young Fleuri’s Horse was killed under him. He shew’d so much Bravery, and was so useful in rallying the Troops, that the Congress have made him a Present of another.

“Extract from a Boston Newspaper, [after 4 December 1777],” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 25, October 1, 1777, through February 28, 1778, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986, pp. 244–245.] (12/16/2022)

Fleury also participated in the Battle of Germantown, where, in classical La Fayette-fashion, he was wounded in the leg. The General Orders from October 3, 1777 read as follows:

Lewis Fleury Esqr. is appointed Brigade Major to The Count Pulaski, Brigadier General of the Light Dragoons, and is to be respected as such.

“General Orders, 3 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 372–375.] (12/16/2022)

Fleury was ordered to defend Fort Mifflin on November 4, 1777, where he would be engaged in the attack on Fort Mifflin on November 15 of the same year. Fleury was again wounded but even more important, he kept a very detailed journal and his entries from October 15-19 were often cited to illustrate the events surrounding the attack.

Concerning his wounds (and his personal value) Colonel Samuel Smith wrote to George Washington on November 16, 1777:

Major Fleury is hurt but not very much. he is a Treasure that ought not to be lost.

To George Washington from Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, 16 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 281–282.] (12/16/2022)

La Fayette became aware of Fleury’s brave conduct and wrote to Henry Laurens on November 18, 1777:

You heard as soon almost as myself of all the interesting niews on the Delaware. The gallant defense of our forts deserves praisespraise and her daughter emulation arethe necessary attendants of an army. I am told that Major Fleury and Captain du Plessis have done theyr duty. It is a pleasant enjoyement for my mind, when some frenchmen behave a la francoise, and I can assure you that everyone who in the defense of our noble cause will show himself worthy of his country shall be mentionned in the most high terms to the king, ministry, and my friends of France when I’l be back in my natal air.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 151-153.

George Washington had recommended Fleury and as a result of this recommendation, Fleury was commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel on November 26. La Fayette was very much in Fleury’s favour, and he wrote again to Henry Laurens on November 29, 1777:

The bearer of my letter is Mr. de Fleury who was in Fort Miflin, and as he is reccommanded by his excellency I have nothing more to say but that I am very sensible of his good conduct. (…) Mr. de Fleury receives just now the commission of lieutenant colonel, I think he wo’nt go to day to Congress, and I send this letter by one other occasion (…)

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 160-161.

Fleury was also recommended by Colonel Henry Leonard Philip, Baron d’Arendt, the commander of Fort Mifflin. Arendt wrote to Alexander Hamilton on October 26, 1777:

Col. Smith who is well acquainted with this place, its defence, and my Intentions respecting them, will make every necessary arrangement in my absence to maintain harmony between himself and Colo. [John] Green—I must do him the justice to say that he is a good Officer and I wish America a great many of the same cast. I must render the same justice likewise to Maj. Fleury who is very brave and active.

Notes of “To George Washington from Brigadier General David Forman, 26 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 13–16.] (12/16/2022)

George Washington also had something to say about this quarrel between his soldiers. He wrote to James Mitchell Varnum on November 4, 1777:

I thank you for your endeavours to restore confidence between the Comodore & Smith—I find something of the same kind existing between Smith and Monsr Fleury, who I consider as a very valuable Officer. How strange it is that Men, engaged in the same Important Service, should be eternally bickering, instead of giving mutual aid. Officers cannot act upon proper principles who suffer trifles to interpose to create distrust, & jealousy (…)

“From George Washington to Brigadier General James Mitchell Varnum, 4 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 128–129.] (12/16/2022)

I do not praise you often, but in this case I will – well said, Sir!

There was no division in the army at the present that Fleury could assume command of and he was therefor appointed sub-inspector under the Baron von Steuben. The General Orders from April 27, 1778 read:

Lieutt Coll Fleury is to act as Sub-Inspector and will attend the Baron Stuben ’till Circumstances shall admit of assigning him a Division of the Army—Each Sub-Inspector is to be attended daily by an Orderly-Serjeant drawn by turns from the Brigades of his own Inspection that the necessary orders may be communicated without delay.

“General Orders, 27 April 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 14, 1 March 1778 – 30 April 1778, ed. David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2004, pp. 657–658.] (12/126/2022)

La Fayette, in the meantime, was lobbying for Fleury and other French officers – apparently to a degree or in a way that he later was unwilling to admit. The following passage was removed by the Marquis from a letter to George Washington from January 20, 1778:

I am told that Mullens is to be lieutenant colonel, if it is so, as that the same commission was done for Mssrs. de Fleury and du Plessis who are on every respect so much out of the line of Mullens who being by his birth of the lowest rank, and not so long ago a private soldier, I hope that those gentlemen are to be at least brigadier generals.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 238-239.

It was around this time that preparations for the Canadian expedition were made – an expedition under La Fayette’s command that never came into fruition and probably was never really intended to do so. It was here that Fleury was appointed aide-de-camp to La Fayette. Horatio Gates wrote to our Marquis on January 24, 1778:

Congress having thought proper and in compliance with the wishes of this Board, from a Conviction of your Ardent Desire to signalize yourself in the Service of these States, to appoint you to the Command of an Expedition meditated against Montreal it is the Wish of the Board that you would immediately repair to Albany, taking with you Lt. Colo. de Fleury, and such other gallant French officers as you think will be serviceable in an Enterprise in that Quarter. (…)

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 249-250.

La Fayette in his turn wrote to Henry Laurens on February 4 and on February 7, 1778 respectively to inform him of the proceedings. He also used the opportunity to get a word for Fleury in and to gossip a bit about the same.

There is Lieutenant Colonel Fleury who not only out of my esteem and affection for him but even by a particular reccommandation of the board of war is destinated to follow me to Canada. I schould have desired of Congress every thing or employement which I could have believed more convenient to his wishes, had I not expected to see him before-you know he was upon my list. He desires to be at the head of an independent troop with the rank of Colonel. I do’nt know which will be the intentions of Congress but every thing which can please Mr. de Fleury not only as a frenchman but as a good officer, and as being Mr. de Fleury will be very agreable to me. (…) I have showed to Colonel Fleury the first lines of my letter, in order to let him know my giving willingly the reccommandation he asks for you. You know that gentleman's merit and that Duplessis and himself were made lieutenant colonels as reward of fine actions.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 279-280.

You have seen Mr. de Fleury. I fancy entre nous that he will not be satisfied in so high pretensions. He is very unhappy that Mr. Duer is no more in Congress because he is his intimate friend and confident-that will perhaps surprise you.’ Mr. de Fleury is entre nous a fine officer but rather too ambitious. When I say such things I beg you to burn the letters.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 282-283.

Henry Laurens replied on February 7, 1778 and his wording at the end especially is quite interesting given La Fayette’s previous letter.

I had the honour this Morning of receiving your Commands by the hands of Lt. Colo. Fleury. This Gentleman notwithstanding the aid of some able advocates in Congress has failed in his pursuit of a Colonel's Commission. You will wonder less, when you learn that the preceeding day I had strove very arduously as second to a warm recommendation from a favorite General, Gates, on behalf of Monsr. Failly, for the same Rank, without effect. The arguments adduced by Gentlemen who have opposed these measures, are strong & obvious. “We are reforming & reducing the Number of Officers in our Army, let us wait the event, & see how our own Native Officers are to be disposed of”-& besides, there is a plan in embrio for abolishing the Class of Colonel in our Army, while the Enemy have none of that Rank in the Field. Some difficulty attended obtaining leave for Monsr. Fleury to follow Your Excellency, Congress were at first of opinion he might be more usefully employed against the shipping in Delaware & formed a Resolve very flattering & tempting to induce him-but his perseverence in petitioning to be sent to Canada, prevailed. Monsr. Fleury strongly hopes Your Excellency will encourage him to raise & give him the Command of a distinct Corps of Canadians. I am persuaded you will adopt all such measures as shall promise advantage to the Service & there is no ground to doubt of your doing every reasonable & proper thing for the gratification & honour of [a] Gentleman of whom Your Excellency speaks & writes so favorably.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 284-285.

With the failure of the expedition, Fleury once again longed for an independent command and La Fayette wrote to Charles Lee in June of 1778:

One of the best young french officers in America Mr. de Fleury wishes much to be annexed to the Rifle Corps and is desired by Clel. Morgan.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 62-64.

In the end, Fleury was given command of a light infantry battalion on June 15, 1779. The General Orders for that day read as follows:

The sixteen companies of Light-Infantry drafted from the three divisions on this ground are to be divided into four battalions and commanded by the following officers;

4. companies from the Virginia line by Major Posey.

4—ditto from the Pennsylvania line by Lt Colo. Hay.

4—ditto two from each of the aforesaid lines by Lieutenant Colonel Fleury.

“General Orders, 15 June 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives,[Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 21, 1 June–31 July 1779, ed. William M. Ferraro. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012, p. 176.] (12/16/2022)

He led his battalion into the attack of Stony Point on July 16, 1779. His conduct was, by all accounts, heroic and George Washington wrote on September 30, 1779:

Colo. Fleury who I expect will have the honour of presenting this lettr. to you, and who acted an important & honourable part in the event, will give you the particulars of the assault & reduction at Stony Point (…) He led one of the columns – struck the colours of the garrison with his own hands – and in all respects behaved with intrepidity & intelligence which marks his conduct upon all occasions.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 313-319.

His actions were indeed so gallant that Congress awarded him a silver medal on July 26, 1779. This is indeed quite remarkable since he was the only foreign officer thus honoured. No other foreign officer, not even La Fayette, received such a silver medal during the Revolutionary War.

Fleury obtained a leave of absence from Congress in September of 1779 and left America on November 16. La Fayette was at this time in France as well and was eager to receive a first-hand account from Fleury with respect to political as well as to military matters. Although still in possession of his American commission, Fleury re-entered the French army and was made a Major of the Saintonge Regiment in March of 1780 (this might interest you @acrossthewavesoftime.) A few months later, in July of 1780, he joined General Rochambeau’s expeditionary force. Fleury was one of the French soldiers at the Battle of Yorktown. He left America for good in January of 1783 and sailed from Boston to France. It was only at this point, that he resigned his American commission. In France, he joined the Pondichéry Regiment and was named its Colonel. He was elevated to a maréshal de camp in 1791 and fought in the battle of Mons on April 28-30, 1792. During the retreat, he was wounded for the third time. While his previous injuries were all relative mild, this one appears to have been rather serious. He resigned from the army not long after.

Not much is known about Fleury’s later life, and I have seen drastically different accounts of the time of his death. While some editors of (La Fayette’s) letters/papers have put the date of his death around 1814, it is far more likely that he died in 1799. Fleury never married and there are no known children of his.

François Louis Teisseydre, Marquis de Fleury’s legacy is the De Fleury Medal that is granted to outstanding members of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

#24 days of la fayette#la fayette's aide-de-camps#marquis de lafayette#french history#la fayette#american history#american revolution#french revolution#letter#history#francois louis teisseydre#marquis de fleury#1777#1778#1772#1779#1780#1783#battle of yorktown#stony point#fort mifflin#henry laurens#george washington#battle of brandywine#battle of germantown#1799#1791#1792#1814#founders online

17 notes

·

View notes