#textile waste

Text

2024 will be the year of thrifting cute clothes and abandoning fast fashion

#we really need to move past mindless consumerism#🎐.txt#fashion#thrifting#new years#new years resolution#2024#important#coquette#hell is a teenage girl#it girl#solarpunk#solarpink#<-new term for cute girly solarpunk shit fuck you#textile waste#hopepunk

226 notes

·

View notes

Text

organizing shampoo bars

Organizing my shampoo and conditioner bars along with my sanitary pads.

I used a cardboard box, covered with leftover cloth that I sewed by hand.

I am far from perfect zero waste, couldn't adapt to menstrual cups or O.B. or menstrual panties.

However, not being perfect doesn't stop me from trying the best I can in all the rest.

#Reduce the waste#zero waste#zerowaste#sustainability#recycling#recycle#reduce reuse recycle#ecofriendly#earthfriendly#reuse#creative reuse#cardboard box#cardboard cutouts#textile design#textile crafts#textile waste#shampoo and conditioner#shampoo bars#Conditioner bars#Organizing#Organization#Eco cosmetics#eco friendly

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whoever on here said that work pants aren’t even made to last no more; you are 10^100% right. I just discovered that I have a 2+ inch big hole on my pants along with another parallel to it bc my thighs are mighty. I am able to fix damn near everything cloth related but

my work pants getting holes when they are under a year old is

unacceptable.

#recycled words#planned obsolescence#clothing repair#dumpster stories#reduce reuse recycle#clothing waste#textile waste#work pants#enshittification

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

upcycled old fabric face masks into a blouse. i’ve not seen this kind of neckline before, have you? what i did was to sew all the fabric rectangles together, then estimate where i would cut out the boat neck neckline, made some staying stitches vertically to fix the pleats of the masks, then cut out the neckline, so the pleats would be retained across the entire horizontal span.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is... patchwork, right?

I still have a LOT of fabric scraps from the sewing class back in 2022 (the blue ones!). Back in November '23, I finally purchased Olfa Rotary Cutter and I feel that now my job has become easier. It gives me a push to do something with the fabric scraps I have accumulated in 2023. So far, I've cut the scraps into 5-cm wide strips (with various lengths), 10 x 10 cm, and 5 x 5 cm. I still have a long way to go, there are still 3-4 boxes of fabric scraps left—GOSH.

My plan for 2024 is to use as many scraps as I could, turn them into jackets or bags, and probably to stop buying more fabrics 🥲

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fashion designer Sawayanagi Naoshi uses only all-natural materials to make clothing that can be safely decomposed by microorganisms in the soil. His partner Hirota Takuya, who studied agriculture helped develop the ideal soil. Their brand is also unique because clothing is rented, not sold, ensuring it's returned when the wearer is done with it. Seeing clothes from beginning to end as they return to the earth is the heart of the pair's astonishing endeavor to reshape the fashion business.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unsold clothing may no longer be destroyed in Europe

More than 100,000 tons of discarded clothing ends up in a desert in Chile

Europe is putting a stop to the throw-away culture through a ban on destruction[1] and a digital product passport with information about shelf life and repairability. No more mass destruction of clothing and other unsold merchandise.[2]

Every second in Europe, a full garbage truck of clothing is burned or dumped[3]. And every year, an estimated 11 to 32 million unsold and returned garments are destroyed. Europe has been wanting to reduce this gigantic waste for some time. The European Member States and the European Parliament reached an agreement to this end on Monday evening 4-12: Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation[4]. The aim of the 'eco design law' is to make many products more repairable, reusable and recyclable. A product passport and a ban on destruction of unused goods are the key measures.

1. What is a digital product passport?

Consumers are already somewhat familiar with this: the energy label on refrigerators and washing machines gives an indication of their sustainability. That label (or product passport) has had an enormous impact on making those appliances more energy efficient.

The European Parliament and the EU member states now have an agreement to roll out the digital passport more widely and to deepen its content. First of all, almost all products on the European market will have to have such a passport: from car tires and steel to washing tablets and cosmetics to clothing or smartphones. The only exceptions are food, medicine, cars and weapon systems, for which there are separate regulations.

In addition to any energy consumption, the passport also contains information about the origin, composition, repair and disassembly options of the product. This should also make it easier to repair and recycle them. “People can know at a glance which product is the most durable or easiest to repair,” said MEP Sara Matthieu (Green), who was rapporteur in the negotiations.

2. What does the ban on destruction mean?

Initially, the ban applies to textiles. Globally, 92 million tons of textile waste are produced annually. A large portion of these are returned or unsold goods. In two years' time, they may no longer be destroyed, but must be reused or recycled. This ban will eventually be extended to electronics and electrical appliances. Massive quantities of these are also destroyed every year, especially cheaper items that are not sold or have been returned to the manufacturer.

The new rule goes hand in hand with stricter requirements for composition, repairability and disassembly of goods. The details will be worked out product by product by the European administration, but some guiding principles are a ban on adhesives, the absence of toxic substances, the obligation to have spare parts available and, above all, to offer them at an affordable price. The passport should eventually lead to a 'repair score', comparable to the energy label.

Matthieu (Green) expects a huge impact on the consumer market. 'Instead of offering disposable products for mass consumption, companies will offer many more services through robust devices. So to speak, you will no longer buy a washing machine, but an number of wash cycles.'

3. How comprehensive are the measures?

That depends on the control. The product passport is also an important instrument for this. Europe is counting on the famous 'Brussels effect': foreign producers will have to adapt their products if they want to maintain access to the gigantic European consumer market. Although the European consumer organisation BEUC[5] warns against loopholes. The organisation mainly sees a risk that international online platforms such as Amazon or Alibaba will circumvent the new law.

4. Is this agreement now final?

It has already rounded the most important cape. The agreement was finalised in the so-called trialogue negotiations between the European Parliament, the European Council and the Commission. Now it must be approved by Parliament and the Member States, but that counts as a formality.

Source

Lieven Sioen, Onverkochte kledij mag niet meer vernietigd worden in Europa, in: De Standaard, 6-12-2023, https://www.standaard.be/cnt/dmf20231205_96579697#:~:text=In%20eerste%20instantie%20is%20het,ze%20hergebruikt%20of%20gerecycleerd%20worden.

[1] Deal on new EU rules to make sustainable products the norm; https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20231204IPR15634/deal-on-new-eu-rules-to-make-sustainable-products-the-norm

[2] Read also: https://www.tumblr.com/earaercircular/722179599996534784/towards-a-circular-and-more-sustainable-fashion?source=share

[3] Read also: https://www.tumblr.com/earaercircular/723895455727157248/new-report-clothes-are-mercilessly-downcycled-or?source=share & https://www.tumblr.com/earaercircular/720260226679488512/hms-answer-about-the-dumped-clothes-article?source=share

[4] The proposal for a new Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR), published on 30 March 2022, is the cornerstone of the Commission’s approach to more environmentally sustainable and circular products. The proposal builds on the existing Ecodesign Directive, which currently only covers energy-related products. https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/standards-tools-and-labels/products-labelling-rules-and-requirements/sustainable-products/ecodesign-sustainable-products-regulation_en

[5] The European Consumer Organisation (BEUC, from the French name Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs, "European Bureau of Consumers' Unions") is an umbrella consumers' group, founded in 1962. Based in Brussels, Belgium, it brings together 45 European consumer organisations from 32 countries (EU, EEA and applicant countries). BEUC represents its members and defends the interests of consumers in the decision process of the Institutions of the European Union, acting as the "consumer voice in Europe". BEUC does not deal with consumers’ complaints as it is the role of its national member organisations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

EU consumers discard about 5.8 million tonnes of textiles annually – around 11 kg per person – of which about two-thirds consist of synthetic fibres, according to the briefing. “In Europe, about one-third of textile waste is collected separately, and a large part is exported.” Africa and Asia are therefore the largest destinations of these toxic fibres. Simply put: by exporting European used clothes and textiles waste, their impacts necessarily fall on the shoulders of Africans and Asians.

Baher Kamal, ‘Europe Sells to Africa and Asia 90% of Its Used Clothes, Textiles Waste’, Inter Press Service

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a peak at some of the things you can find in my posh closet.

I'm working hard to keep wearable fashion out of the landfill!

0 notes

Text

The Truth About Zero Waste Fashion: What you need to know?

View On WordPress

#conscious brands#environmental impact#fashion industry sustainability#innovative techniques#repurposing clothing#sustainable fashion#textile waste

0 notes

Text

I always thought of the thrift store as a comforting place. Somewhere I could reliably and conscientiously take unwanted clothing to be resold and re-worn, or as the fashion industry has recently rebranded it, re-loved. In the process, charities do great things with the profits from reselling them: supporting troops. Saving pets. Curing cancer. But, like many of us, I never knew the full story.

Amid the explosion in online shopping and TikTok trends for fast-fashion hauls, thrift stores—and thrifting apps—have exploded in the last few years. In fact, in small towns like mine, brick and mortar stores have stopped being primarily a place to buy goods, but more often a place to dispose of them. According to one British study, we only wear 44 percent of the clothing we own. And when we need more room, how better to dispose of our old clothes than donate them to charity?

Unfortunately, it’s never that simple. Consider: only between 10 and 30 percent of second-hand donations to charity shops are actually resold in store. The rest disappears into a machine you don’t see: a vast sorting apparatus in which donated goods are graded and then resold on to commercial partners, often for export to the Global South.

The problem is that, with the onslaught of fast fashion, these donations are too often now another means of trash disposal—and the system can’t cope. Consider: around 62 million tons of clothing is manufactured worldwide every year, amounting to somewhere between 80 and 150 billion garments to clothe 8 billion people.

We rarely see the networks of people involved in processing, reselling, and eventually reusing the things we donate—vast networks that encircle the globe like a ball of yarn, conveying our unwanted things to people in places like Afghanistan or Togo or Bangladesh. Like anything we put in the bin, they are sent “away.” In this case not thrown, but given.

I wanted to follow that yarn—tracing the movement of donations through the textile traders who ship them off, and then charting the surprising places those clothes end up. Which is how, on a spring day last year, I ended up on a flight to West Africa.

Saturday in Accra, the capital of Ghana. Market day. Shoppers pack the streets of the central shopping district, the roads clogged with stalls and street hawkers. When you’re looking for second-hand clothes in Accra, there is only one destination: Kantamanto, the largest second-hand clothes market in Ghana, and perhaps in West Africa. Every week, 15 million garments move through Kantamanto, where an estimated 30,000 traders are crammed into just seven claustrophobic acres. The majority arrives, via container ship, having been donated to charities in Europe and North America. From here, the clothes will spread across Ghana and across borders, into Côte D’Ivoire, Togo, Niger, Benin and beyond.

The second-hand trade in Ghana and across West Africa exploded in the 1980s and ’90s as Western charities flooded Africa with clothing, intended both as fundraising and aid. When second-hand textiles first arrived in Ghana, the local population had no experience of such wastefulness. In fact, they assumed the owners of the clothes must have died, leading to the Akan phrase still marked on one of the entrances to Kantamanto: Obroni wawu, or “dead white man’s clothes.” (In Tanzania, second-hand clothing is similarly sometimes called kafa ulaya, or "dead Europeans" clothes’.) But the donations, however well intended, have done as much harm as good. Unable to compete with the flood of cheap goods into Africa, local textile manufacturing sectors collapsed. Between 1975 and 2000, the number of people working in the textile trade in Ghana fell by 75 per cent. Businesses simply couldn’t compete on price with a product people were throwing away.

I’m here to meet Yayra Agbofah and Kwamena Dadzie Boison, the co-founders of The Revival, a Ghanaian fashion brand that specializes in upcycling second-hand clothing. Yayra, The Revival’s creative director, is a towering, elegant man with a penchant for wide-brimmed hats and wider-legged trousers. Kwamena, the slighter and the quieter of the two, with a neat beard and a taste in rings, is the brand’s head of design. Together, they are two of the most stylish men I’ve ever met, today both dressed head to toe in black, Yayra in one of The Revival’s T-shirts which reads: ghana upcycling department.

Yayra has been shopping at Kantamanto since he was a teen. “Growing up I wanted to look fashionable, but I am not from a rich family that could afford the kind of clothes that I wanted,” he explains. “So I started to trade or redesign stuff that I got from my brother and my siblings. Then my brother introduced me to Kantamanto, and I fell in love with the second-hand market.”

Yayra Agbofah, left, and Kwamena Dadzie Boison of The Revival, a Ghanaian fashion brand that specializes in upcycling second-hand clothing.

A few years ago, Yayra started to hear traders in Kantamanto complaining about the declining quality of clothing shipments. He also saw it himself. “I used to collect vintage,” Yayra explains. Once upon a time, you could find gems among the endless reams of GAP hoodies and Next jeans: Alexander McQueen, Vivienne Westwood. Luxury fashion houses habitually slash unsold items, known as deadstock, so that it has no resale value. But sometimes uncut stock would find its way into the bales, providing an irregular supply of designer clothing to Accra’s eager fashion scene. In the last few years, however, the rising popularity of thrifting and resale apps has ensured that the highest-end clothing (and its resale value) is increasingly staying in the Global North, while fast fashion has unleashed a wave of ever-lower-quality clothing on Kantamanto.

The market runs to a timetable. On Mondays and Thursdays, containers arrive fresh from the port of Tema laden with new bales. The importers and textile dealers then sell the bales on to the traders. “The prices range from about $75 to about $500, based on where it’s coming from, and also the grade,” Yayra says. British bales command the highest price; this is partly due to better sorting, and the increased chance of finding unworn deadstock, which sells at a markup. "What comes in from America and Canada, you have a lot more waste." The bales are sold by garment type – men’s shoes, women’s tops – but the specific contents are a mystery, so after buying each bale, the traders will go through, valuing each item.

“It’s a game of luck,” Yayra says – one that more and more traders are losing. When the sellers can’t make their money back, many get into debt. Over time, as the quality has fallen, some have found themselves in a debt spiral, unable to get out.

Saturday is the busiest day of the week. It’s today that most traders open their bales for new shoppers, who can arrive before daylight in search of the best bargains. We, however, arrive mid-afternoon, hoping that the traders might have more time to talk now the crowd has thinned. The market itself is a maze of narrow lanes, held up by simple wooden struts and a tin roof. But its simplicity hides an entire self-contained neighborhood. Beyond the stalls, there are seamstresses; cobblers; dyers, who with a quick soak can restore a fading T-shirt or pair of jeans; a whole crew of men wielding flat irons (cast iron irons, heated over hot coals) to spruce up clothes. After hours, there are barbers and food sellers and secret bars playing uptempo beats, which throng with life when work is done. We wind our way down aisles filled with racks of clothes: Asos, Dorothy Perkins, Zara, some still with their charity shop labels on. The stalls themselves are tiny. The floor and gutters are carpeted with clothing.

Young women pass with clothing bales balanced on their head. They are kayayei (literally translated, “she who carries the burden”), porters employed by the sellers to move bales around the market. The kayayei, often illiterate teenage immigrants, are paid almost nothing; many live in the informal settlement of Old Fadama, a short walk from the market.

The majority of sellers in Kantamanto are women, and so Yayra and Kwamena respectfully call them "Auntie". We stop by the stall of Janet Oforiwaa, who has been working in Kantamanto for thirty years, since she was a girl working on her mother’s stall. She sells winter clothes: parkas, coats, tweed jackets. These might seem unlikely sellers in the heat of Accra, but have their own audience: fishermen, travelers and people in neighboring Burkina Faso, where the desert nights can be as cold as the days are hot.

Yayra and Kwamena have been shopping at Kantamanto for so long that they seem to know everyone. Traders holler in delight as they arrive, offering warm greetings and hugs.

Later, after showing me the market, Yayra and Kwamena invite me down to the headquarters of their own operation, the nonprofit upcycling business that they run. The Revival’s design studio, which is attached to Yayra’s house in a quiet Accra suburb. Like them, the place is perfectly styled: buffed wood floors, music playing, the room decorated with vintage sewing machines and photographs cut from fashion magazines. The studio is a treasure trove of thrift trash. Bales of clothing are piled all around: boxy suits, swathes of stonewash denim, a box full of men’s hats. On one rack Yayra has set up a little museum of uniforms: a police coat, Iraq war camo, US Navy jackets. A jacket from the US Army’s 307th Signal Battalion still displays both its insignia, Optime Merenti, “to the best deserving.” “We have big bags of these things, with names still on them,” Yayra says.

Every piece of used clothing tells a story of distance and time. An old leather American football helmet. A Pittsburgh Steelers jacket. A baseball cap from Mount Robson, ‘Highest peak in the Canadian Rockies.’ A whole rack of thick leather motorbike jackets, unusable in Ghana’s tropical climate. The Revival attempts to turn some of these unusable or unsellable items into stylish, desirable objects. ‘Our idea is: it’s here already, we cannot send it back, we don’t have the power. So we might as well just turn it to something functional here,’ Yayra says. The Revival works with the skilled craftspeople within Kantamanto – the seamstresses, tailors, dyers and cobblers – to help extend the lifespan of items that would otherwise be thrown away. Yayra takes out a bright red down jacket that they have resewn into a backpack. It’s an ingenious piece of design, both sustainable and surprisingly trendy. "Now we can use it, and it won’t end up in a landfill," he says.

The Revival is currently a non-profit, and each collection is small-scale and handmade. It sells its designs in pop-up shops in and around Accra. At the moment, the operation is tiny, and can account for only a fraction of the goods arriving in Kantamanto. “We realized that there’s so much waste, and that there is not enough demand for it,” he says.

Their response has been to find people who face clothing shortages, and to find ways to help them with waste. For example, in Ghana more than 80,000 fruit pickers suffer cuts and bruises while harvesting fruit crops without adequate safety equipment. ‘We have about 80,000 pineapple farmers in Ghana. And there is pineapple farming all over Africa and the Caribbean,’ he says. ‘Subsistence farmers don’t have the capital to buy protective clothing, it’s too expensive.’ So in 2020, The Revival developed a line of agricultural protective gear from discarded denim imports, which the brand has donated to farmers around Ghana. Yayra shows me a set of overalls which have been stitched to protect arms and limbs; the fabric itself is screen printed with a pop-art pineapple design. "We’re looking at producing uniforms for oil and sanitation workers," Yayra says. "And we’re looking at using the leather to make jackets for commercial bikers here, because a lot of them don’t wear protective clothing."

Oliver Franklin-Wallis, right, reporting in Ghana.

Of course, the Revival can only save so much. According to research by the OR Foundation, as much as 40 per cent of the clothing arriving at Kantamanto immediately becomes waste. At the end of the day private garbage collectors, known as bola boys, will pass through the aisles pulling carts, taking away unsold items. But collection itself costs money, and so some traders don’t bother, instead leaving waste to accumulate in the aisle and the gutters. The waste is stunning.

Several times a week, the city’s collection trucks pick up countless tonnes of leftover textiles dumped in the aisles and gutters around Kantamanto. Previously, the waste was hauled to an engineered landfill in Kpone, outside the city. But the massive influx of textile waste in recent years created impossible conditions within the landfill, Solomon explains. “The textile waste soaks up water, mixing with the dirt and the silt, and binding them together like concrete,” he says. As a result, the landfill’s compactor crews were having to make three times as many passes to crush the waste down. The consequences have been stark. At Kpone, “the void space that should take thirty to forty years to fill, was full in less than three years.”

The new municipal dumpsite is more than an hour’s drive from the city, and run by a private operator that is unwelcoming to outsiders. Old Fadama’s dumpsite, is a 30 ft mound of garbage on the edge of a lagoon. We decide to climb to the top. Yayra covers his face with a handkerchief; I pull my coronavirus mask over my face to help with the merciless stench. The rubbish crackles and gives way beneath my feet as we climb. Polystyrene chunks, plastic bags, whole chunks of an old LG television, smashed eggs being picked at by flies – and underneath it all, ribbons and ribbons of clothing. Yayra and I comb through the trash, picking out labels: Zara jeans, Adidas sandals, a blazer by Polo University Club, a now-defunct Ralph Lauren brand. “Some days you come and see fresh piles of clothes,” Yayra says.

We wade to the summit, trying not to fall. From there, we can look out on Old Fadama. At the top of the mound a herd of gaunt and sickly-looking cattle are grazing on the garbage. Longhorns. One has a tattered clothing sack tangled in her horn. She looks at me, the bag flapping in the breeze like a white flag.

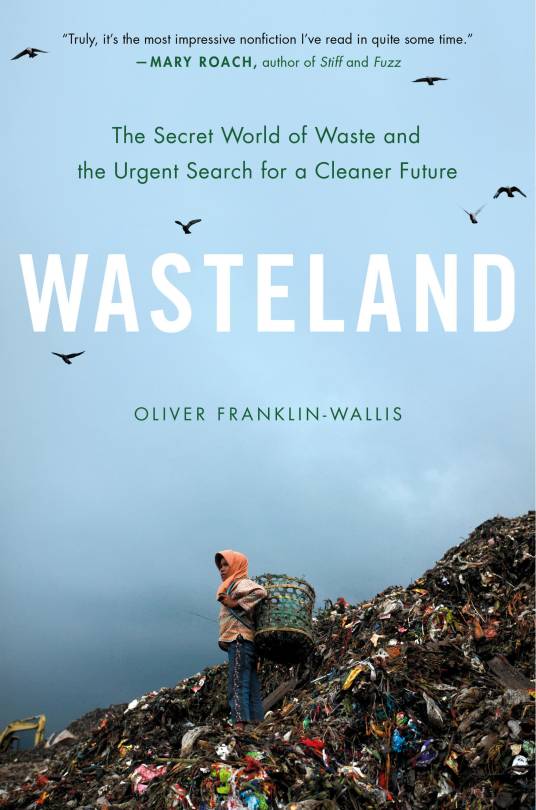

This is an adapted extract from WASTELAND: The Secret World of Waste and the Urgent Search for a Cleaner Future by Oliver Franklin-Wallis

0 notes

Text

Repair regrets? “I wish I could have saved ____ with the right tool(s) or skills.”

I miss my old boots, the ones I found in the dumpster. They were so comfortable and were reasonably water proof for how much they cost- around $45 and from Walmart. They are those cheap kinds that you get when all of the others are out of your range at that moment, the kind that will really start to break down after a year of constant use. Those boots were my #1 choice for everything every single day.

I miss them and I wish there could have been more that I could have done within reason to save them or make them last longer.

Maybe it’s stupid sounding, but sometimes I look back at all of the objects I’ve been given and have owned that I could have put a little more effort into reusing or mending. I’m in my early 20s and still have a lot of skills to learn for later in my life to make sure I don’t generate too much waste.

I happen to think a lot about the hands of the people who’ve crafted my clothes and accessories. I know about the inhumane conditions people are forced to work in and, as a result of the poor pay from that labor, have to live in horrible housing units with (or without) the bare essentials to keep them alive for another day just to labor again. I don’t want to treat their blood sweat and tears like a joke, I don’t want to forget about the treatment these humans have to go through every day to try to feed their families and themselves. Like it or not, every single thing we wear comes from another human who’s being used as a slave for damn near free labor by a big company.

My friends are sewing needles, thread, spare cloth from clothes I no longer wear, stores when I need them, stuffing/filling, E600, patience and creativity. We have created and healed a lot of things that would have been tossed otherwise. There are still regrets about the things we couldn’t work together to save and I think it’s very valid to have those feelings. We as humans have a responsibility to help keep trash and chemical pollution away from where they shouldn’t be.

#recycled words#dumpster diving#reduce reuse recycle#zero waste#freeganism#clothing#clothing waste#zero waste living#low waste#fabric waste#textile waste#plastic waste#waste not want not

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does one upcycle a pile of dirty laundry into a stunning work of modern art?

Laundry day can be a tedious task for many of us, but did you know that your dirty laundry can be upcycled into a stunning work of modern art? With a little creativity and effort, you can transform your mundane laundry pile into something unique and beautiful.

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#aesthetics#art techniques#artistic expression#artistic vision#creativity#dirty laundry#DIY#eco-friendly#environmentalism#home decor#modern art#repurpose#reuse#sustainability#textile art#textile design#textile recycling#textile waste#upcycling

0 notes

Text

How can we reduce Textile Waste

There are many ways to combat textiles waste and reduce the impact on the environment, like use cotton that is still good but not as soft as before. This will help to reduce textile waste. Try on your clothes before you buy them to see if the fabric is perfect or not. This will help to reduce textile waste too. Know more about Textile waste by Recycling fibers.

0 notes

Text

The Swedish pulp producer Renewcell has just opened the world's first commercial-scale, textile-to-textile chemical recycling pulp mill, after spending 10 years developing the technology.

While mechanical textiles-to-textiles recycling, which involves the manual shredding of clothes and pulling them apart into their fibres, has existed for centuries, Renewcell is the first commercial mill to use chemical recycling, allowing it to increase quality and scale production. With ambitions to recycle the equivalent of more than 1.4 billion T-shirts every year by 2030, the new plant marks the beginning of a significant shift in the fashion industry's ability to recycle used clothing at scale.

"The linear model of fashion consumption is not sustainable," says Renewcell chief executive Patrik Lundström. "We can't deplete Earth's natural resources by pumping oil to make polyester, cut down trees to make viscose or grow cotton, and then use these fibres just once in a linear value chain ending in oceans, landfills or incinerators. We need to make fashion circular." This means limiting fashion waste and pollution while also keeping garments in use and reuse for as long as possible by developing collection schemes or technologies to turn textiles into new raw materials.

Each year, more than 100 billion items of clothing are produced globally, according to some estimates, with 65% of these ending up in landfill within 12 months. Landfill sites release equal parts carbon dioxide and methane – the latter greenhouse gas being 28 times more potent than the former over a 100-year period. The fashion industry is estimated to be responsible for 8-10% of global carbon emissions, according to the UN.

Just 1% of recycled clothes are turned back into new garments. While charity shops, textiles banks and retailer "take-back" schemes help to keep those donated clothes in wearable condition in circulation, the capabilities of recycling clothes at end-of-life are currently limited. Many high street stores with take-back schemes, including Levi Strauss and H&M, operate a three-pronged system: resell (for example, to charity shops), re-use (convert into other products, such as cleaning cloths or mops) or recycle (into carpet underlay, insulation material or mattress filling – clothing is not listed as an option).

Much of the technical difficulty in recycling worn-out clothes back into new clothing comes down to their composition. The majority of clothes in our wardrobes are made from a blend of textiles, with polyester the most widely produced fibre, accounting for a 54% share of total global fibre production, according to the global non-profit Textile Exchange. Cotton is second, with a market share of approximately 22%. The reason for polyester's prevalence is the low cost of fossil-based synthetic fibres, making them a popular choice for fast fashion brands, which prioritise price above all else – polyester costs half as much per kg as cotton. While the plastics industry has been able to break down pure polyester (PET) for decades, the blended nature of textiles has made it challenging to recycle one fibre, without degrading the other. (Read more about why clothes are so hard to recycle.)

By using 100% textile waste – mainly old T-shirts and jeans – as its feedstock, the Renewcell mill makes a biodegradable cellulose pulp they call Circulose. The textiles are first shredded and have buttons, zips and colouring removed. They then undergo both mechanical and chemical processing that helps to gently separate the tightly tangled cotton fibres from each other. What remains is pure cellulose.

6 notes

·

View notes