#student nonviolent coordinating committee (sncc)

Text

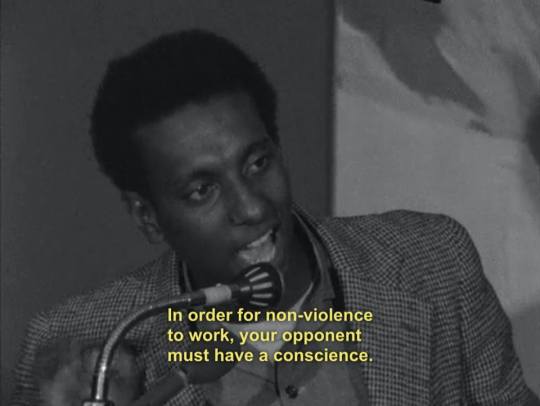

[ID: Two black and white photos of Kwame Ture/Stokely Carmichael, a young Black man, saying into a microphone with a sardonic expression, "In order for non-violence to work, your opponent must have a conscience. The United States has none, has none." End ID.]

#Kwame Ture#Stokely Carmichael#Pacifism#anti colonialism#antifashism#antifascism#antifashist#antifascist#got tired of seeing the inaccessible version knowing there's doznes of IDs buried in the comments#described images#accessible photos#Black Panthers#Black Power#Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee#SNCC#non-violence#peace#united states#politics#ferguson#From the river to the sea Palestine will be free#free Palestine#free gaza#Gaza#Palestine#BLM#Black Lives Matter#Landback

905 notes

·

View notes

Photo

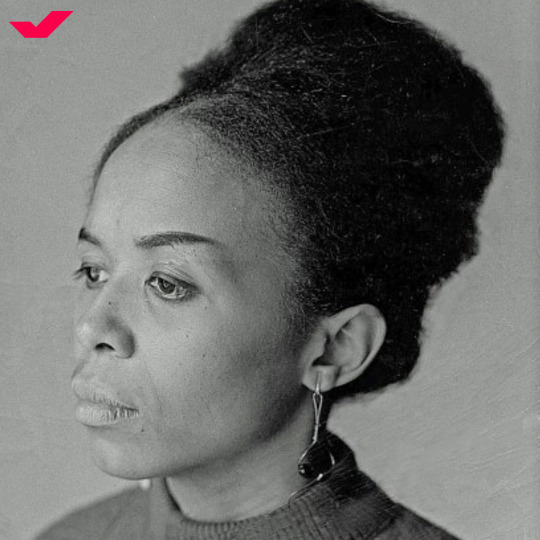

We are saddened to hear about the passing of Dorie Ann Ladner, lifelong voting rights activist. 🕊️🗳️

Ms. Ladner participated in every major civil rights protest of the 1960s, including the March on Washington and the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. She was a key organizer in her home state of Mississippi, with contributions to the NAACP and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In June 1964, she launched a volunteer campaign called “Mississippi Freedom Summer,” with a goal of registering as many Black voters as possible.

We remember and honor Dorie through the words of her sister and fellow activist, Joyce Ladner: as someone who “fought tenaciously for the underdog and the dispossessed,” and “left a profound legacy of service.”

#dorie ladner#dorie ann ladner#voting rights#civil rights#women's history month#mississippi#naacp#sncc#student nonviolent coordinating committee#black voters#black voter#activist#1960s

328 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gloria Richardson, May 6, 1922 / 2023

(image: Gloria Richardson (center) with Stanley Branche (left), Riggs Robinson (right) and other demonstrators during a 1963 march in Cambridge, MD. Photo: © Leonard McCombe/The Life Picture Collection/Getty Images)

#photography#gloria richardson#birthday anniversary#stanley branche#riggs robinson#cambridge non violent action committee#student nonviolent coordinating committee#sncc#naacp#national association for the advancement of colored people#leonard mccombe#life magazine#1920s#1960s#2020s

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ella josephine baker#ella baker#civil rights activist#human rights advocate#grassroots organizing#leadership philosophy#mentorship#student nonviolent coordinating committee (sncc)#w. e. b. du bois#thurgood marshall#a. philip randolph#martin luther king jr.#diane nash#stokely carmichael#bob moses#radical democracy#social justice#racial equality#gender equality#civil rights movement

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

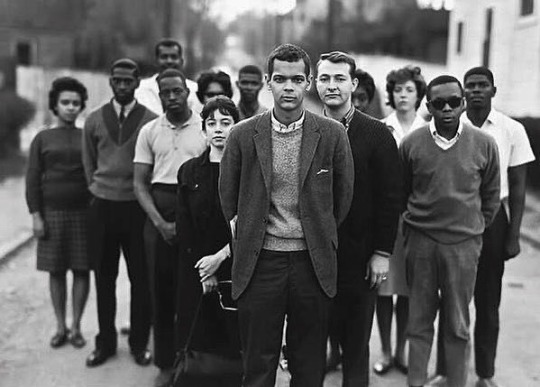

Danny Lyon Sit-in by Members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at a Segregated Restaurant, Atlanta 1963

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today We Honor Julian Bond

Julian Bond was an activist in the civil rights, economic justice, and peace movements since his college years.

In 1960, Bond helped found the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and earlier that year, he helped create the Atlanta University student civil rights organization, which directed several years of nonviolent protests and won integration of Atlanta’s movie theaters, lunch counters, and parks.

Bond served 20 years in the Georgia House and Georgia Senate, drafting more than 60 bills that became law. He was president of the Atlanta branch of the NAACP for 11 years and in 1998, was elected chair of the NAACP national board and served for 11 terms until stepping down in 2010.

CARTER™️ Magazine carter-mag.com #wherehistoryandhiphopmeet #historyandhiphop365 #carter #cartermagazine #blackhistorymonth #blackhistory #history #julianbond #staywoke

#carter magazine#carter#historyandhiphop365#wherehistoryandhiphopmeet#history#cartermagazine#today in history#staywoke#blackhistory#blackhistorymonth#julian bond

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

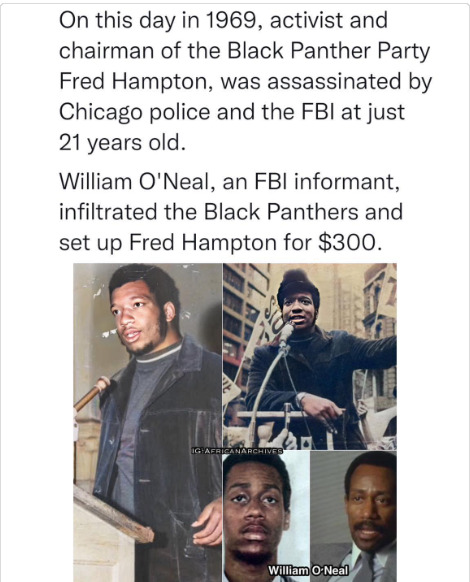

In Illinois, where Fred Hampton was born, the police constantly harassed black people. Access to social goods too was made difficult, if not curtailed, in the areas with heavy black populations.

The party, a creation of Huey Newton and fellow student Bobby Seale, insisted on black nationalist response to racial discrimination. The party’s Illinois chapter was opened in 1967 and Hampton joined in 1968, aged just 20.

when Stokely Carmichael’s Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) split from the Panthers in 1969, Hampton headed the Illinois chapter of the Panthers.

Then a petty criminal, O’Neal was coerced by the FBI into helping them silence Hampton and the Black Panther Party. And he did just that when he infiltrated the party and provided the FBI with a floor plan of the Chicago apartment where Hampton was assassinated in 1969.

His journey to becoming an FBI informant began in 1966 when he was tracked by FBI Agent Roy Martin Mitchell after stealing a car and driving it across state lines to Michigan.

He was told that he would forget about the stolen car charge if he infiltrate the Panthers for the FBI.

The Panther Party had then become infamous for brandishing guns, challenging the authority of police officers, and embracing violence as a necessary by-product of revolution.

O’Neal agreed to infiltrate the party and when he got accepted, he served as the group’s chief of security.

Reports said he even became in charge of security for Hampton and had keys to Panther headquarters and safe houses.

He eventually provided the floor plan of Hampton’s west-side apartment that was used to plan the raid that killed Hampton and his fellow Panther, Mark Clark.

Fred Hampton, was executed in his sleep by race soldiers, sleeping next to his pregnant wife, Akua Njeri.

O’Neal hardly spoke of his undercover years but in a 1984 interview with the Tribune, one of his last public interviews, he mentioned that he “thrived” on his work with law enforcement though in the end, he realized he had been ”just a pawn in a very big game.”

Source: African Archives

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

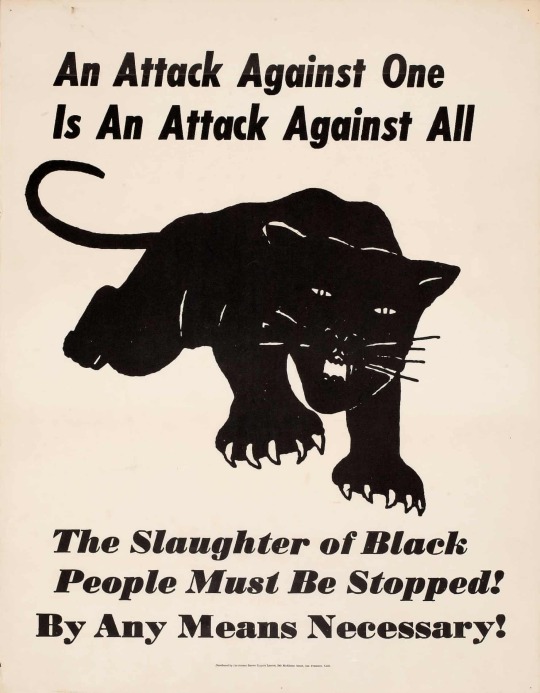

Power to the people: the branding of the Black Panther party

An Attack Against One Is an Attack Against All, 1968 Designer Unknown

The history of the logo can be traced back to designer Ruth Howard, a member of the Atlanta branch of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee where she learned how visuals could galvanize a community. In 1966, SNCC organizers in Lowndes county approached her to create the symbol. Howard originally designed a dove to express power and autonomy but it wasn’t well received. She eventually based it on the school mascot of Clark College, a local HBCU. Dorothy Zeller, a white Jewish woman, added whiskers and the black color

Photograph: The Merrill C Berman Collection

#the merrill c berman collection#black panther party#an attack against one is an attack against all#poster#activism#history#student nonviolent coordinating committee#lowndes county#georgia#ruth howard#designer#dorothy zeller#clark college

82 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 8 June 1961, a group of Freedom Riders were arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, including Kwame Ture, Gwendolyn Greene and Joan Mulholland (pictured, l-r). Freedom Riders fought government non-enforcement of the ban on segregation in public transport in the US South by riding in multiracial groups. They faced intense violence from local police and white supremacists, including the Ku Klux Klan, until eventually winning in December that year. Ture (born Stokely Carmichael) became a central organiser in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later the Black Panther Party. He was targeted by the FBI's COINTELPRO operation, and "bad jacketed" – falsely painted as a CIA agent and expelled from the SNCC. Greene (who later changed her name to Britt) had also been arrested in 1960 for refusing to leave the segregated Glen Echo Amusement Park in Maryland. With others, she confronted counter-protesters from the American Nazi Party and continued picketing until the end of summer. The park then agreed to abolish segregation before reopening the following year. Mulholland, then aged 19, had participated in numerous civil rights sit ins, for which she was disowned by her family. In 1963, she was travelling with four other activists in Mississippi when their car was attacked by the KKK, who had orders to kill them, but they managed to escape. Mulholland remains active to this day. Image from the excellent @ZinnEducationProject More information, sources and map: https://stories.workingclasshistory.com/article/10819/freedom-riders-arrested https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=640538474786038&set=a.602588028581083&type=3

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Dion J. Pierre

Harvard University denounced an antisemitic image depicting a Jew lynching an African American and an Arab which was posted on social media by an anti-Zionist faculty group.

“The university is aware of social media posts today containing deeply offensive antisemitic tropes and messages from organizations whose membership includes Harvard affiliates,” the university said, speaking from its Instagram account. “Such despicable messages have no place in the Harvard community. We condemn these posts in the strongest possible terms.”

Harvard Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine (FSJP), a group which describes itself as a “collective” committed to falsely accusing Israel of genocide and dispossession — terms one finds on the fringes of the extreme right — initiated this latest controversy. The image it shared shows a left-hand tattooed with a Star of David containing a dollar sign at its center dangling a Black man and an Arab man from a noose. In its posterior, an arm belonging to an unknown person of color wields a machete that says, “Liberation Movement.”

“African people have a profound understanding of apartheid and occupation,” says a graphic in which the image appears. “The historical roots of solidarity between Black liberation movements and Palestinian liberation began in the late 1960s. This period was marked by a heightened awareness among Black organizations in the United States.”

It continued, “The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [SNCC] linked Zionism to an imperial project while the Black Panther Party aligned itself with the Palestinian resistance, framing both struggles as part of a unified front against racism, Zionism, and imperialism.”

On Monday, Harvard Faculty and Staff for Justice in Palestine — whose 112 founding members include professors Walter Johnson, Jennifer Brody, Diane Moore, Charlie Prodger, Leslie Fernandez, Khameer Kidia, and Duncan Kennedy — apologized for sharing the image and suggested that it was unaware of its own social media activity.

“It has come to our attention that a post featuring antiquated cartoons which used offensive antisemitic tropes was linked to our account,” the group said. “We removed the content as soon as it came to our attention. We apologize for the hurt that these images have caused and do not condone them in any way.”

Two other student groups have apologized for sharing the image, according to The Harvard Crimson. In a joint statement, the Harvard Undergraduate Palestine Solidarity Committee and the African and American Resistance Organization said “our mutual goals for liberation will always include the Jewish community — and we regret inadvertently including an image that played upon antisemitic tropes.”

The past four months have been described by critics of Harvard as a low-point in the history of the school, America’s oldest and, arguably, most prestigious institution of higher education. Since the October 7 massacre by Hamas, Harvard has been accused of fostering a culture of racial grievance and antisemitism, while important donors have suspended funding for programs. Its first Black president, Claudine Gay, resigned in disgrace last month after being outed as a serial plagiarist. Her tenure was the shortest in the school’s history.

As scenes of Hamas terrorists abducting children and desecrating dead bodies circulated worldwide, 31 student groups at Harvard, led by the Palestine Solidarity Committee (PSC) issued a statement blaming Israel for the attack and accusing the Jewish state of operating an “open air prison” in Gaza, despite that the Israeli military withdrew from the territory in 2005. In the weeks that followed, anti-Zionists stormed the campus screaming “from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” and “globalize the intifada,” terrorizing Jewish students and preventing some from attending class.

In November, a mob of anti-Zionists — including Ibrahim Bharmal, editor of the prestigious Harvard Law Review — followed, surrounded, and intimidated a Jewish student. “Shame! Shame! Shame! Shame!” the crush of people screamed in a call-and-response chant into the ears of the student who —as seen in the footage — was forced to duck and dash the crowd to free himself from the cluster of bodies that encircled him.

The university is currently being investigated by the US House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce. It was recently subpoenaed by the body after weeks of allegedly obstructing the inquiry.

#harvard#harvard university#hamas#gaza#palestine solidarity committee#antisemitic image#antisemitism

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day, remembering James Baldwin

Happy Heavenly Birthday to the profound, brilliant author and activist Mr. James Arthur Baldwin!

James Arthur Baldwin was a novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic.

Baldwin's essays, such as the collection Notes of a Native Son (1955), explore palpable yet unspoken intricacies of racial, sexual, and class distinctions in Western societies, most notably in mid-20th-century America, and their inevitable if unnameable tensions.

Some Baldwin essays are book-length, for instance The Fire Next Time (1963), No Name in the Street (1972), and The Devil Finds Work (1976).

His novels and plays fictionalize fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures thwarting the equitable integration of not only blacks, but also gay men—depicting as well some internalized impediments to such individuals' quest for acceptance—namely in his second novel, Giovanni's Room (1956), written well before gay equality was widely espoused in America.

Baldwin's best-known novel is his first, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953).

SOCIAL & POLITICAL ACTIVISM:

He wrote about the movement, Baldwin aligned himself with the ideals of the Congress of Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee(SNCC). In 1963 he conducted a lecture tour of the South for CORE, traveling to locations like Durham and Greensboro, North Carolina and New Orleans, Louisiana. During the tour, he lectured to students, white liberals, and anyone else listening about his racial ideology, an ideological position between the "muscular approach" of Malcolm X and the nonviolent program of Martin Luther King Jr..

By the Spring of 1963, Baldwin had become so much a spokesman for the Civil Rights Movement that for its May 17 issue on the turmoil in Birmingham, Alabama, Time magazine put James Baldwin on the cover. "There is not another writer," said Time, "who expresses with such poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in North and South."

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Despite its public portrayal of itself, the ADL isn’t a civil rights group in any meaningful sense, but rather, a veiled pro-Israel lobbying organization that uses superficial language of inclusiveness and anti-racism to defend Israel from criticism from the left. The ADL already assists large social media platforms in determining what is and isn’t hate speech, and by teaming up with the #StopHateForProfit effort, the group will likely have even more say in determining what content is worthy of publication. The problem is that the ADL has made it clear on a number of occasions that it considers the entire basis of the peaceful Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement — embraced by virtually all of Palestinian civil society — to be hate speech, specifically any claim that denies Israel’s “existence as a Jewish state” (e.g. its claim to ethnonational supremacy over non-Jews living in Palestine). The ADL’s website clearly states, “Anti-Israel activity crosses the line to anti-Semitism” with any statement that “Israel is denied the right to exist as a Jewish state,” and that “the founding goals of the BDS movement and many of the strategies used by BDS campaigns are anti-Semitic.”

Put another way, if Palestinians don’t co-sign their own ethnic cleansing by agreeing with the radical premise that the land of their birth, or where their families are from, is axiomatically meant for Jews, they are, according to the ADL, engaging in racist speech. So too will non-Palestinian allies of Palestine be painted as racists: Recently, the ADL’s deputy national director took to the New York Times to accuse Peter Beinart, who was once among the most prominent liberal Zionist writers in the United States, of anti-Semitism for announcing that he now supports one state based on equal rights.

The use of anti-hate-speech laws and regulations to snuff out calls for equal rights in Palestine is not theoretical — it’s common practice already in France, which has used such laws to effectively make the BDS movement illegal. While these are laws, not social media rules of conduct, the principle is the same: Any speech that calls into question Israel’s right to exist as a ethno-supremacist state is de facto anti-Semitic.

In 2017, the ADL accused the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), a grassroots Black Lives Matter organization founded in 2014, of anti-Semitism, a form of hate speech, because M4BL’s platform read, in part, “The U.S. justifies and advances the global war on terror via its alliance with Israel and is complicit in the genocide taking place against the Palestinian people.” It follows that if the M4BL were to post this statement on social media, it’s likely the ADL would view it as hate speech and demand Facebook take it down. If the ADL views the foundational documents of the M4BL as including hate speech, how can the ADL possibly assert itself as a moral authority in this moment? Has the ADL’s position changed since 2017, or does the ADL still to this day consider the M4BL’s platform anti-Semitic?

The ADL smearing Black activists who oppose Israel isn’t new. In the 1960s, the ADL harshly criticized the Black-led Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Black Panthers for their criticisms of Israel, equating these “negro extremists” with the KKK and American Nazi Party. The ADL also worked with the Israeli government in the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s to spy on Arab groups, as well as leftwing anti-South African apartheid activists. As Pulitzer Prize-winning author Glenn Frankel noted in Foreign Policy magazine in 2010, “The Anti-Defamation League participated in a blatant propaganda campaign against Nelson Mandela and the ANC in the mid 1980s and employed an alleged ‘fact-finder’ named Roy Bullock to spy on the anti-apartheid campaign in the United States — a service he was simultaneously performing for the South African government. The ADL defended the white regime’s purported constitutional reforms while denouncing the ANC as ‘totalitarian anti-humane, anti-democratic, anti-Israel, and anti-American.’”

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

MOGAI BHM- Day 14!

happy BHM! today i’m going to be talking about the Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s!

Origins of the Black Power Movement-

[Image ID: A photograph of a clipping of a flyer on faded, worn parchment paper. At the very top, in small print, the flyer reads “What can you do about the tear gas raid?”

In large, bold, underlined hand printing, the flyer reads:

“1) Black Out for Black Power, 2) Work Stop for Black Power, 3) Register to Vote for Black Power”.

Below this in smaller text, it reads “our tax dollars helped to buy that tear-gas. Don’t buy anything downtown. If you work for the white man, don’t go to work Friday. Hit them where it hurts. We’ve gone too far to turn back now”. End ID.]

The Black Power movement grew out of tensions from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Earlier on in the Civil Rights Movement, there was more consensus and collaboration between many different Black organizations- the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the NAACP- they all worked relatively smoothly together.

However, in the later 1960s, sentiments among younger activists from the SNCC began to shift. Students became increasingly disillusioned with the principal of nonviolence. Many students from the SNCC began to develop more radical viewpoints. It was all based in the idea that Black people should not have to make themselves palatable to the whites of America just to get their own human rights. Black freedom matters infinitely more than white comfort and understanding, and many Black activists began to adopt that mindset later on in the 60s.

During the 1960s Freedom Rides, interstate bus rides to challenge interstate travel segregation, many of these sentiments started to come to light, because many of the participants were students from the SNCC, and they became very angry with Martin Luther King Jr., who publicly supported the rides but did not participate. This was one distinct instance of where activists from the SNCC began to diverge from the mindsets of other civil rights groups.

Black power grew out of a growing realization that Blackness was something to be fiercely proud of- in many cases, Black people were forced to sacrifice their racial pride for the concept of colorblindness to prove to racist white people that they deserved to be treated with respect- but it only enforced the idea that Black people had to try to be like white people, had to abandon their Blackness, in order to be respected- a reclamation of the Blackness was the foundation for the growing Black Power movement.

As far of the roots of the term ‘Black Power’ itself, it was first known to be used by Black writer Richard Wright in his 1954 book ‘Black Power’. The principles of Black self-determination also gave rise to the use of the term Black Power in protests, slogans, and rally cries throughout the Civil Rights Movement- notably, the SNCC used the rally cry ‘we want Black Power’!

The Black Power Movement-

[Image ID: A black-and-white photograph of five Black women, all with afros, raising their firsts into the air and shouting. End ID.]

The Black Power movement, having grown out of increased dissatisfaction with the assimilationist politics of some of the Civil Right Movement, was based on the desire for Black self-determination- so its key ‘tenets’ focused on Black control of their own economic, political, and social systems so that they could decide their own futures instead of leaving that up to the racist powers that be.

Black Power’s emphasis on Black pride meant that many proponents of the movement began to focus on fully embracing the aspects of their Black identity that they had been hiding before- this included a huge rise in many Black people embracing and growing their natural hair, Black language and art thriving, and Black pride becoming a core part of one’s identity.

In 1966, ‘Black Power’ was more ‘officially’ claimed by calling for ‘Black Power’ instead of Black assimilation, by Stokely Carmichael, the then leader of the SNCC. The next year, in 1967, Black experts and scholars held what was called the Black Power Forum in Greensboro, North Carolina. Over the course of three days, these experts held a panel where they discussed the concept of Black Power and Black political self determination, the illegitimacy of the concept of ‘reverse racism’, and other key topics becoming prevalent within Black Power spheres.

Black theology played a huge part in the Black Power movement- it was largely a new form of Black Christian theology, but Christianity was not the only religion to factor into the Black Power movement. Black Power was frequently expressed through sermons at Black Church services, speeches by Black Power theologians, and other forms of Black Power expressed through religious freedom. Gatherings at Churches, seminars at conferences, speeches at events- they all became key places where thousands of Black people, many of them students, would gather to celebrate their common Black identity. As expressed in the opening remarks of Reverend Robert Hamill, “The American N*gro has changed his name from “Negro” to “black” and changed his cry from “freedom” to “power”.”

A huge part of the Black Power movement focused on Black literature, Black art, and Black music- many Black artists emerged as visionaries for what Black Power could look like- they turned the concepts of Black Power into powerful visual experiences. An example of these works of art is The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, an exhibition of Black female art created by artist Betye Saar in 1972, which have become integral to Black female power over the past 5 decades. During the Black Power movement, visual art, and the literature it inspired, focused on portraying the Black identity in a light of glory and beauty, turning racist sentiments into sentiments of racial pride.

Black art during this time was sparked by a sentiment that echoed Harlem Renaissance ideals and art, and in 1965, poet Amiri Baraka founded the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem to encourage the development of Black art through visual art, theater, literature, drama, and music, which sparked the Black Arts Movement that included such visionaries as Audre Lord, James Baldwin, and Maya Angelou.

The principles of the Black Power movement were hugely inspired by Malcolm X- a Black revolutionary who believed in militant Black nationalism and Black self-determination. He, along with key groups of the Black Power movement like the Black Panther Party, the Nation of Islam, and Women in Black Power, as well as key figures of Black Power like Angela Davis, Shirley Chisholm, and Amiri Baraka, will all be discussed in future posts.

Summary-

The Black Power movement emerged from growing sentiments that Black freedom and integration wasn’t enough- nonviolence wasn’t the answer, Black power was, meaning Black political, social, cultural, and economic self determination

Black Power was articulated and called for by SNCC chair Stokely Carmichael, who was inspired by works of Malcolm X

Black Power was expressed through sermons, conferences, academic forums, and growing movements like the Black Arts Movement and the growth of groups like the Black Panther Party

Black Power was and is about Black pride, Black beauty, and the right of all people to have determination over their lives and their futures, in a racial and cultural context

tagging @metalheadsforblacklivesmatter @intersexfairy @cistematicchaos

Sources-

https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power

https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-black-power-movement/sources/382

https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/carmichael-stokely

https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-black-power-movement/sources/384

https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/the-black-power-movement

https://www.getty.edu/news/art-and-the-black-power-movement/

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Three Killed, Fifty Injured in South Carolina Shootings: Black Students Are Victims of Trigger Happy White Cops, Liberation News Service, LNS 39, Washington D.C., February 9, 1968 [Cleveland L. Sellers, Jr. Papers, 1934-2003, Lowcountry Digital Library, Charleston, SC. © Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC]

(plus: Feb. 8, 1968: Orangeburg Massacre, Zinn Education Project, Washington, D.C.)

#typewriting#orangeburg massacre#samuel hammond jr.#delano middleton#henry smith#liberation news service#cathy archibold#student nonviolent coordinating committee#sncc#cleveland l. sellers jr. papers#lowcountry digital library#avery research center#zinn education project#1960s

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

They marched for desegregation — then they disappeared for 45 days : NPR

This photo of the group known as the Leesburg Stockade Stolen Girls was taken by Danny Lyons, a former SNCC photographer. It helped confirm the girls' location to their parents and civil rights activists. Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos hide caption

In the early 1960s, civil rights protests were picking up speed across the country. Sometimes, protest marches included children as young as 12 years old.

Usually, children who were arrested at protests were bailed out by activist groups, or eventually released to their parents. But on July 19, 1963, during a march to desegregate a theater in Americus, Ga., a group of Black girls was arrested — and for the rest of the summer, their parents had no idea where they were.

One of those girls was Lulu Westbrook-Griffin.

"We were gung-ho young people who want to change the system," Westbrook-Griffin told Radio Diaries.

Westbrook-Griffin was 12 years old at the time. Her older brother, nineteen-year-old James Westbrook, was a field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. With SNCC, Westbrook organized a march to desegregate the Martin Theatre, the only theater in Americus.

At least 40 people attended. But as the marchers approached the theater, local police demanded that they disperse, and began beating them with clubs and setting dogs on them.

"Some of us were taken by our feet and arms and thrown in a paddy wagon, and I was one of them," Westbrook-Griffin recalled.

Westbroook-Griffin's brother escaped arrest. "I told Mom that night: 'They drove her off in a paddy wagon and I have no idea where they went,'" James Westbrook said.

Along with at least 13 other girls, Westbrook-Griffin was transported to a single cell of the Leesburg Stockade — an abandoned, Civil-War-era building more than 20 miles away from Americus.

For the next 45 days, the girls would be subject to squalid living conditions. The stockade lacked running water, plumbing and beds. As the weeks passed, conditions only deteriorated.

"We were putting our waste in the shower drain because the toilet was overflowing," Westbrook-Griffin recalled.

Back in Americus, SNCC activists and parents were focused on locating the missing girls.

"Americus is a small town where everybody knew everybody," James Westbrook said. "It was a network of parents trying to find out, day by day, where their children were."

Throughout July and August, SNCC activists went from jail to jail in search of the missing girls. At one of SNCC's mass meetings, someone mentioned a rumor that the girls were being held in the old Leesburg Stockade.

Danny Lyon was a photographer for SNCC at the time. "James Foreman, who was executive secretary, said to go down and check it out," Lyon told Radio Diaries.

Lyon drove to the Leesburg Stockade after dark. There, he took clandestine pictures of the girls and their living conditions through bars of the building.

Lyon's photos confirmed the girls' location to parents and activists, providing leverage as they fought with authorities for the girls' return. Finally, on Sept. 1 – 45 days after they were taken – the police released the girls to their parents. Danny Lyon's photos appeared in Jet magazine in late September and in a special issue of SNCC's The Student Voice newspaper in 1964.

Westbrook-Griffin and the other girls were never formally charged after the march. They also weren't given a reason for why they were held in the stockade so long.

"Was it to break me? Was it to make me fearful? Was it to teach me a lesson?" Westbrook-Griffin says. She wonders to this day why the girls were kidnapped. "But when you look back at it now, you realize it pretty much was a badge of honor rather than a badge of disgrace. We were part of something that matters."

Lulu Westbook-Griffin and the other girls in the Leesburg Stockade were never formally charged. And local law enforcement never explained why they were held in the stockade for so long.

The stockade is still standing. In 2019, the state of Georgia put a historical marker on the site, acknowledging the incident. It reads, "Because their families were not initially told their location and the girls never faced formal charges, they became known as the Leesburg Stockade Stolen Girls."

#They marched for desegregation — then they disappeared for 45 days#stockade stolen girls of leesburg#leesburg georgia#georgia#white supremacy#right to vote#civil rights movement#kidnapped Black girls#leesburg stockage#sclc#sncc

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danny Lyon Bob Dylan, Cortland Cox, Pete Seeger and James Forman Sitting Outside the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Office, Greenwood, Mississippi 1963

68 notes

·

View notes