#strategic white womanhood

Text

“When white women are confronted with the possibility they can be perpetrators, and not only victims, of oppressive actions and they burst out crying, antiracist work grinds to a halt. A white woman sobs, and the room falls to her feet. These tears seemingly perform a self-baptism. They cleanse the sufferer of any past wrongs and invest her with a martyred authority flowing from the realm of allegedly indisputable truth: her own hurt feelings. Some of the sanctifying innocence widely afforded to white women when they cry can be traced back to an original wellspring: the inkpot of Harriet Beecher Stowe.

-Kyla Schuller, The Trouble with White Women

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

https://www.insurrecthistory.com/archives/2022/01/10/i-always-dressed-this-way-surfacing-nineteenth-century-trans-history-through-mary-jones

“We know the lurid details of [Mary Jones’s] legal troubles made her a minor recurring figure in local newspapers during her life. One rare glimpse of her own voice comes from court testimony recorded during People vs. Sewally when she was asked why she wore women’s clothing. Jones explained:

“I have have been in the practice of waiting upon Girls of ill fame…they induced me to dress in Women’s Clothes, saying I looked so much better in them and I have always attended parties among the people of my own Colour dressed in this way – and in New Orleans I always dressed this way.”

But beyond the brief, strategically crafted narratives given in court, little of her life, thoughts, feelings, and relationships is known.

Jones’ interactions with the carceral system–and her intermittent, sensationalizedappearances in newspapers throughout the 1830’s to 50’s–must be understood within her specific historical context. The United States' growing urban populations, particularly in northeastern cities such as New York, rendered trans communities increasingly visible, inviting increasing public and political concern with crossdressing. A wave of anti-masquerade laws intended to forestall deceptions across racial lines were passed across the United States during Jones’ lifetime, including New York’s 1845 penal code 240.35(4); they were also quickly marshaled to harass trans people. In 1836, Jones was arrested for stealing the wallet of Robert Haslem, a white man who solicited her sex work. A lithograph published following her conviction for grand larceny depicts Jones as a beautiful woman, elegantly dressed and calmly side-eyeing the viewer. The caption describes her as “The MAN-MONSTER.”… a label that at once denies Jones’ womanhood by suturing her to the category “man” while excluding her from that category through the epithet “monster.”

The name “man-monster” places Jones at the nexus of two continuing histories of attempted dehumanization. Misogynoir constructs Black women as improperly feminine and therefore improperly human. Transmisogynist bigotry dehumanizes trans women by denying manhood and womanhood, thus rendering us neuter–an inhuman “it.” The archival objects that inform us about Jones bear witness to forms of oppression that continue to the present– to an intricate, pernicious, and ongoing mingling of racism, misogyny, and transphobia. The public mockery and carceral violence inflicted on Jones should be understood as analogous to the violent backlash against trans women of color that has followed our current moment of trans visibility – a backlash resulting in 2021 being the deadliest year for trans people on record in the United States. Justice demands that we remember the cruelties Jones suffered as we work to build a world that would make them truly locked in a historical past.”

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spiritual Quarantine: Three Acts of Harm (2022)

I accepted an invitation to the Brooklyn Museum for the First Saturday’s monthly event. While on the museum's third floor, seated among many melanated individuals and vendors, a white doctor, whom I befriended through a mutual associate, chose white violence. She clears her throat, squints her eyes, makes a pointed eye towards a crowd of black women, and asks: “Do you think she had a BBL (Brazilian Butt Lift)?”

A former social work colleague, whom I began working with in 2018, invited me to dinner. While seated in a restaurant, enjoying Korean BBQ, this white male homosexual chose misogyny. Over dinner, we shared an update on our lives, at which point he thought to share that he supports the overturning of Roe vs. Wade.

I met a white woman over an app, with whom I began a romantic and non-sexual friendship over a period of six months. We intended on going to Riis Beach for Pride, and the week before, she began to love bomb me, and the night before Pride day, she began rubbing my head and kissing me goodnight on the cheek. While at the beach, we had no reception to connect. However, upon walking across the crowds of gay and lesbian and queer individuals, she spots me and yells my name. Unbeknownst to me, she chose heterosexism. She and I hug, and she swiftly invites me to her boyfriend. I was not informed that he would be present at the beach; a man whom I had never even seen a picture of.

In these three experiences, my blackness, womanhood, and lesbian identities were violated, and the experience was egregious. These three whites are employed as a licensed internal medicine doctor, licensed master’s level social worker, and licensed master’s level nurse. These were the whites that one might think they’ve read; they ought to be politically literate, they appear cultured. And in none of these instances of macroaggressions did they seek amends for the psychospiritual and sociocultural harm their words and behavior had inflicted upon my being.

I forgive myself for believing that their company was worthwhile. I accept that I endured violence because I fell into the trap of compulsive politeness and disregarded my visceral rage. I release these whites, and those like them, from access to my aura, time, and energy. They are genuinely unworthy.

I am picking up the shards of a mirror I have not fully absorbed the reflection of light from. I am seeing myself anew. The tower is falling, and so are the former iterations of self that must die to give birth to a woman who exudes self-mastery. I consider these white liberals to be my spiritual training ground. I may have failed the exam upon the first encounter, but I rebuke the repetition of such nonchalance with the enactment of harm.

War is metaphysical, and my defense will be atypical and critical. I will strategize that which is logistical, but I ain’t fucking with no more subliminal. These folks were indisputably parasitical. I am not immune, nor will I play the role of an acquiescent coon. Not with my Scorpio moon. I will flood my spirit with love like a monsoon to repel what seeks to penetrate my divine shell.

#truths89#poetry#zisa aziza#negressofsaturn#spirituality#white violence#heterosexism#white supremacy#trauma#sociocultural#violence#psychospiritual#energy#vampires#too comfortable#i see you#hex#bye simpleness#self-accountability#healing#socialization#whiteness#unaceptable#harmful#microaggressions#macroagressions

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! I have a q abt parasocial relationships - how have they evolved since your coming out? Surely the pandemic and its isolation plus your channel’s growth (as well as good ol misogyny) have affected this, but I know you’ve also taken steps to help create some healthy distance like getting rid of your PO box. As a viewer, I’ve noticed more Discourse about you online popping up in any case (but also lol that’s just being Trans and Online TM, no?). So how has it looked from your side?

I would say it's a mixed bag haha.

The highs have gotten higher! It's always nice when people reach out and say they've been moved or inspired by something I've made and it seems that's happening a bit more now - in particular from younger trans people which is lovely! (Although there is sometimes a note of sadness to that for me, because they tell me how they've been hurt by their families or the NHS and I feel powerless to do anything that will help, and a bit guilty about my relative privilege as a white trans woman.)

On the flipside, the lows have gotten rare - but lower. Nasty people are a tiny minority I'm happy to say, even tinier than before, but when people are mean about me now it's a lot more venomous. It seems like people have gotten more comfortable framing criticisms in a hyperbolic way, like before they might have said, "This show isn't for me," now they might say, "This is the worst fucking shit I've ever seen." Whereas before they might have said, "I don't vibe with the host's screen presence," now I do just get people libelling me - like, actually accusing me of horrible crimes - which is obviously distressing. It seems like they don't think I have feelings because I'm a woman. It also seems like there are things I did before that didn't bother people, but which suddenly bother them now? If I talk about my work and what I've been up to and what I'm proud of people are a lot quicker to chalk that up to arrogance, even though I talk about that stuff to the same extent I ever did? Only again, because people have gotten comfortable with hyperbole it gets much more extreme - I saw someone say the other day that I have "narcissistic personality disorder" and I'm an "inhuman" "master manipulator" based on the fact that I tweeted about a TV show that I was literally in as my job! I spoke to a friend about it like, "It seems like some people don't like seeing me do well anymore?" and she was like "Yeah lol welcome to womanhood." So, people seem a lot more willing to believe that I'm a villain now, which is odd. I can brush off that sort of thing when it comes from transphobes; it hurts more when it comes from other trans people.

I dunno, that's all just how it seems to me. Before I even came out I wove a digital net around myself with strategic blocks and automatic muting of certain terms, which has held up pretty well - for the most part if people are negative about me I don't see it but the constructive criticism still gets through!

I don't wanna give a mopey impression either haha, the vast, vast majority of the interactions I get are really positive!

506 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Sexually Identify as an

Attack Helicopter

by ISABEL FALL

I sexually identify as an attack helicopter.

I lied. According to US Army Technical Manual 0, The Soldier as a System, “attack helicopter” is a

gender identity, not a biological sex. My dog tags and Form 3349 say my body is an XX-karyotope

somatic female.

But, really, I didn’t lie. My body is a component in my mission, subordinate to what I truly am. If I

say I am an attack helicopter, then my body, my sex, is too. I’ll prove it to you.

When I joined the Army I consented to tactical-role gender reassignment. It was mandatory for the

MOS I’d tested into. I was nervous. I’d never been anything but a woman before.

But I decided that I was done with womanhood, over what womanhood could do for me; I wanted to

be something furiously new.

To the people who say a woman would’ve refused to do what I do, I say—

Isn’t that the point?

I fly—

Red evening over the white Mojave, and I watch the sun set through a canopy of polycarbonate and

glass: clitoral bulge of cockpit on the helicopter’s nose. Lightning probes the burned wreck of an oil

refinery and the Santa Ana feeds a smoldering wildfire and pulls pine soot out southwest across the

Big Pacific. We are alone with each other, Axis and I, flying low.

We are traveling south to strike a high school.

Rotor wash flattens rings of desert creosote. Did you know that creosote bushes clone themselves?

The ten-thousand-year elders enforce dead zones where nothing can grow except more creosote.

Beetles and mice live among them, the way our cities had pigeons and mice. I guess the analogy

breaks down because the creosote’s lasted ten thousand years. You don’t need an attack helicopter

to tell you that our cities haven’t. The Army gave me gene therapy to make my blood toxic to

mosquitoes. Soon you will have that too, to fight malaria in the Hudson floodplain and on the banks

of the Greater Lake.

Now I cross Highway 40, southbound at two hundred knots. The Apache’s engine is electric and

silent. Decibel killers sop up the rotor noise. White-bright infrared vision shows me stripes of heat,

the tire tracks left by Pear Mesa school buses. Buried housing projects smolder under the dirt,

radiators curled until sunset. This is enemy territory. You can tell because, though this desert was

once Nevada and California, there are no American flags.

“Barb,” the Apache whispers, in a voice that Axis once identified, to my alarm, as my mother’s.

“Waypoint soon.”

“Axis.” I call out to my gunner, tucked into the nose ahead of me. I can see only gray helmet and

flight suit shoulders, but I know that body wholly, the hard knots of muscle, the ridge of pelvic

girdle, the shallow navel and flat hard chest. An attack helicopter has a crew of two. My gunner is

my marriage, my pillar, the completion of my gender.

“Axis.” The repeated call sign means, I hear you.

“Ten minutes to target.”

“Ready for target,” Axis says.

But there is again that roughness, like a fold in carbon fiber. I heard it when we reviewed our

fragment orders for the strike. I hear it again now. I cannot ignore it any more than I could ignore a

battery fire; it is a fault in a person and a system I trust with my life.

But I can choose to ignore it for now.

The target bumps up over the horizon. The low mounds of Kelso-Ventura District High burn warm

gray through a parfait coating of aerogel insulation and desert soil. We have crossed a third of the

continental US to strike a school built by Americans.

Axis cues up a missile: black eyes narrowed, telltales reflected against clear laser-washed cornea.

“Call the shot, Barb.”

“Stand by. Maneuvering.” I lift us above the desert floor, buying some room for the missile to run,

watching the probability-of-kill calculation change with each motion of the aircraft.

Before the Army my name was Seo Ji Hee. Now my call sign is Barb, which isn’t short for Barbara. I

share a rank (flight warrant officer), a gender, and a urinary system with my gunner Axis: we are

harnessed and catheterized into the narrow tandem cockpit of a Boeing AH-70 Apache Mystic.

America names its helicopters for the people it destroyed.

We are here to degrade and destroy strategic targets in the United States of America’s war against

the Pear Mesa Budget Committee. If you disagree with the war, so be it: I ask your empathy, not

your sympathy. Save your pity for the poor legislators who had to find some constitutional

framework for declaring war against a credit union.

The reasons for war don’t matter much to us. We want to fight the way a woman wants to be

gracious, the way a man wants to be firm. Our need is as vamp-fierce as the strutting queen and

dryly subtle as the dapper lesbian and comfortable as the soft resilience of the demiwoman. How

often do you analyze the reasons for your own gender? You might sigh at the necessity of morning

makeup, or hide your love for your friends behind beer and bravado. Maybe you even resent the

punishment for breaking these norms.

But how often—really—do you think about the grand strategy of gender? The mess of history and

sociology, biology and game theory that gave rise to your pants and your hair and your salary? The

casus belli?

Often, you might say. All the time. It haunts me.

Then you, more than anyone, helped make me.

When I was a woman I wanted to be good at woman. I wanted to darken my eyes and strut in heels.

I wanted to laugh from my throat when I was pleased, laugh so low that women would shiver in

contentment down the block.

And at the same time I resented it all. I wanted to be sharper, stronger, a new-made thing,

exquisite and formidable. Did I want that because I was taught to hate being a woman? Or because I

hated being taught anything at all?

Now I am jointed inside. Now I am geared and shafted, I am a being of opposing torques. The noise

I make is canceled by decibel killers so I am no louder than a woman laughing through two walls.

When I was a woman I wanted to have friends who would gasp at the precision and surprise of my

gifts. Now I show friendship by tracking the motions of your head, looking at what you look at, the

way one helicopter’s sensors can be slaved to the motions of another.

When I was a woman I wanted my skin to be as smooth and dark as the sintered stone countertop

in our kitchen.

Now my skin is boron-carbide and Kevlar. Now I have a wrist callus where I press my hydration

sensor into my skin too hard and too often. Now I have bit-down nails from the claustrophobia of the

bus ride to the flight line. I paint them desert colors, compulsively.

When I was a woman I was always aware of surveillance. The threat of the eyes on me, the chance

that I would cross over some threshold of detection and become a target.

Now I do the exact same thing. But I am counting radars and lidars and pit viper thermal sensors,

waiting for a missile.

I am gas turbines. I am the way I never sit on the same side of the table as a stranger. I am most

comfortable in moonless dark, in low places between hills. I am always thirsty and always tense. I

tense my core and pace my breath even when coiled up in a briefing chair. As if my tail rotor must

cancel the spin of the main blades and the turbines must whirl and the plates flex against the pitch

links or I will go down spinning to my death.

An airplane wants in its very body to stay flying. A helicopter is propelled by its interior

near-disaster.

I speak the attack command to my gunner. “Normalize the target.”

Nothing happens.

“Axis. Comm check.”

“Barb, Axis. I hear you.” No explanation for the fault. There is nothing wrong with the weapon attack

parameters. Nothing wrong with any system at all, except the one without any telltales, my spouse,

my gunner.

“Normalize the target,” I repeat.

“Axis. Rifle one.”

The weapon falls off our wing, ignites, homes in on the hard invisible point of the laser designator.

Missiles are faster than you think, more like a bullet than a bird. If you’ve ever seen a bird.

The weapon penetrates the concrete shelter of Kelso-Ventura High School and fills the empty halls

with thermobaric aerosol. Then: ignition. The detonation hollows out the school like a hooked finger

scooping out an egg. There are not more than a few janitors in there. A few teachers working late.

They are bycatch.

What do I feel in that moment? Relief. Not sexual, not like eating or pissing, not like coming in from

the heat to the cool dry climate shelter. It’s a sense of passing . Walking down the street in the right

clothes, with the right partner, to the right job. That feeling. Have you felt it?

But there is also an itch of worry—why did Axis hesitate? How did Axis hesitate?

Kelso-Ventura High School collapses into its own basement. “Target normalized,” Axis reports,

without emotion, and my heart beats slow and worried.

I want you to understand that the way I feel about Axis is hard and impersonal and lovely. It is

exactly the way you would feel if a beautiful, silent turbine whirled beside you day and night,

protecting you, driving you on, coursing with current, fiercely bladed, devoted. God, it’s love. It’s

love I can’t explain. It’s cold and good.

“Barb,” I say, which means I understand . “Exiting north, zero three zero, cupids two.”

I adjust the collective—feel the swash plate push up against the pitch links, the links tilt the angle of

the rotors so they ease their bite on the air—and the Apache, my body, sinks toward the hot desert

floor. Warm updraft caresses the hull, sensual contrast with the Santa Ana wind. I shiver in delight.

Suddenly: warning receivers hiss in my ear, poke me in the sacral vertebrae, put a dark

thunderstorm note into my air. “Shit,” Axis hisses. “Air search radar active, bearing 192, angles

twenty, distance . . . eighty klicks. It’s a fast-mover. He must’ve heard the blast.”

A fighter. A combat jet. Pear Mesa’s mercenary defenders have an air force, and they are out on the

hunt. “A Werewolf.”

“Must be. Gown?”

“Gown up.” I cue the plasma-sheath stealth system that protects us from radar and laser hits. The

Apache glows with lines of arc-weld light, UFO light. Our rotor wash blasts the plasma into a bright

wedding train behind us. To the enemy’s sensors, that trail of plasma is as thick and soft as

insulating foam. To our eyes it’s cold aurora fire.

“Let’s get the fuck out.” I touch the cyclic and we sideslip through Mojave dust, watching the school

fall into itself. There is no reason to do this except that somehow I know Axis wants to see. Finally I

pull the nose around, aim us northeast, shedding light like a comet buzzing the desert on its way

into the sun.

“Werewolf at seventy klicks,” Axis reports. “Coming our way. Time to intercept . . . six minutes.”

The Werewolf Apostles are mercenaries, survivors from the militaries of climate-seared states. They

sell their training and their hardware to earn their refugee peoples a few degrees more distance from

the equator.

The heat of the broken world has chased them here to chase us.

Before my assignment neurosurgery, they made me sit through (I could bear to sit, back then) the

mandatory course on Applied Constructive Gender Theory. Slouched in a fungus-nibbled plastic chair

as transparencies slid across the cracked screen of a De-networked Briefing Element overhead

projector: how I learned the technology of gender.

Long before we had writing or farms or post-digital strike helicopters, we had each other. We lived

together and changed each other, and so we needed to say “this is who I am, this is what I do.”

So, in the same way that we attached sounds to meanings to make language, we began to attach

clusters of behavior to signal social roles. Those clusters were rich, and quick-changing, and so just

like language, we needed networks devoted to processing them. We needed a place in the brain to

construct and to analyze gender.

Generations of queer activists fought to make gender a self-determined choice, and to undo the

creeping determinism that said the way it is now is the way it always was and always must be.

Generations of scientists mapped the neural wiring that motivated and encoded the gender choice.

And the moment their work reached a usable stage—the moment society was ready to accept plastic

gender, and scientists were ready to manipulate it—the military found a new resource. Armed with

functional connectome mapping and neural plastics, the military can make gender tactical.

If gender has always been a construct, then why not construct new ones?

My gender networks have been reassigned to make me a better AH-70 Apache Mystic pilot. This is

better than conventional skill learning. I can show you why.

Look at a diagram of an attack helicopter’s airframe and components. Tell me how much of it you

grasp at once.

Now look at a person near you, their clothes, their hair, their makeup and expression, the way they

meet or avoid your eyes. Tell me which was richer with information about danger and capability. Tell

me which was easier to access and interpret.

The gender networks are old and well-connected. They work .

I remember being a woman. I remember it the way you remember that old, beloved hobby you left

behind. Woman felt like my prom dress, polyester satin smoothed between little hand and little hip.

Woman felt like a little tic of the lips when I was interrupted, or like teasing out the mood my

boyfriend wouldn’t explain. Like remembering his mom’s birthday for him, or giving him a list of

things to buy at the store, when he wanted to be better about groceries.

I was always aware of being small: aware that people could hurt me. I spent a lot of time thinking

about things that had happened right before something awful. I would look around me and ask

myself, are the same things happening now? Women live in cross-reference. It is harder work than

we know.

Now I think about being small as an advantage for nape-of-earth maneuvers and pop-up guided

missile attacks.

Now I yield to speed walkers in the hall like I need to avoid fouling my rotors.

Now walking beneath high-tension power lines makes me feel the way that a cis man would feel if he

strutted down the street in a miniskirt and heels.

I’m comfortable in open spaces but only if there’s terrain to break it up. I hate conversations I

haven’t started; I interrupt shamelessly so that I can make my point and leave.

People treat me like I’m dangerous, like I could hurt them if I wanted to. They want me protected

and watched over. They bring me water and ask how I’m doing.

People want me on their team. They want what I can do.

A fighter is hunting us, and I am afraid that my gunner has gender dysphoria.

Twenty thousand feet above us (still we use feet for altitude) the bathroom-tiled transceivers cupped

behind the nose cone of a Werewolf Apostle J-20S fighter broadcast fingers of radar light. Each beam

cast at a separate frequency, a fringed caress instead of a pointed prod. But we are jumpy, we are

hypervigilant—we feel that creeper touch.

I get the cold-rush skin-prickle feel of a stranger following you in the dark. Has he seen you? Is he

just going the same way? If he attacks, what will you do, could you get help, could you scream? Put

your keys between your fingers, like it will help. Glass branches of possibility grow from my skin,

waiting to be snapped off by the truth.

“Give me a warning before he’s in IRST range,” I order Axis. “We’re going north.”

“Axis.” The Werewolf’s infrared sensor will pick up the heat of us, our engine and plasma shield,

burning against the twilight desert. The same system that hides us from his radar makes us hot and

visible to his IRST.

I throttle up, running faster, and the Apache whispers alarm. “Gown overspeed.” We’re moving too

fast for the plasma stealth system, and the wind’s tearing it from our skin. We are not modest. I

want to duck behind a ridge to cover myself, but I push through the discomfort, feeling out the

tradeoff between stealth and distance. Like the morning check in the mirror, trading the confidence

of a good look against the threat of reaction.

When the women of Soviet Russia went to war against the Nazis, when they volunteered by the

thousands to serve as snipers and pilots and tank drivers and infantry and partisans, they fought

hard and they fought well. They ate frozen horse dung and hauled men twice their weight out of

burning tanks. They shot at their own mothers to kill the Nazis behind her.

But they did not lose their gender; they gave up the inhibition against killing but would not give up

flowers in their hair, polish for their shoes, a yearning for the young lieutenant, a kiss on his dead

lips.

And if that is not enough to convince you that gender grows deep enough to thrive in war: when the

war ended the Soviet women were punished. They went unmarried and unrespected. They were

excluded from the victory parades. They had violated their gender to fight for the state and the state

judged that violation worth punishment more than their heroism was worth reward.

Gender is stronger than war. It remains when all else flees.

When I was a woman I wanted to machine myself.

I loved nails cut like laser arcs and painted violent-bright in bathrooms that smelled like laboratories.

I wanted to grow thick legs with fat and muscle that made shapes under the skin like Nazca lines. I

loved my birth control, loved that I could turn my period off, loved the home beauty-feedback kits

that told you what to eat and dose to adjust your scent, your skin, your moods. I admired, wasn���t

sure if I wanted to be or wanted to fuck, the women in the build-your-own-shit videos I watched on

our local image of the old Internet. Women who made cyberattack kits and jewelry and

sterile-printed IUDs, made their own huge wedge heels and fitted bras and skin-thin chameleon

dresses. Women who talked about their implants the same way they talked about computers,

phones, tools: technologies of access, technologies of self-expression.

Something about their merciless self-possession and self-modification stirred me. The first time I

ever meant to masturbate I imagined one of those women coming into my house, picking the lock,

telling me exactly what to do, how to be like her. I told my first boyfriend about this, I showed him

pictures, and he said, girl, you bi as hell, which was true, but also wrong. Because I did not want

those dresses, those heels, those bodies in the way I wanted my boyfriend. I wanted to possess that

power. I wanted to have it and be it.

The Apache is my body now, and like most bodies it is sensual. Fabric armor that stiffens beneath

my probing fingers. Stub wings clustered with ordnance. Rotors so light and strong they do not even

droop: as artificial-looking, to an older pilot, as breast implants. And I brush at the black ring of a

sensor housing, like the tip of a nail lifting a stray lash from the white of your eye.

I don’t shave, which all the fast jet pilots do, down to the last curly scrotal hair. Nobody expects a

helicopter to be sleek. I have hairy armpits and thick black bush all the way to my ass crack. The

things that are taboo and arousing to me are the things taboo to helicopters. I like to be picked up,

moved, pressed, bent and folded, held down, made to shudder, made to abandon control.

Do these last details bother you? Does the topography of my pubic hair feel intrusive and

unnecessary? I like that. I like to intrude, inflict damage, withdraw. A year after you read this maybe

those paragraphs will be the only thing you remember: and you will know why the rules of gender

are worth recruitment.

But we cannot linger on the point of attack.

“He’s coming north. Time to intercept three minutes.”

“Shit. How long until he gets us on thermal?”

“Ninety seconds with the gown on.” Danger has swept away Axis’ hesitation.

“Shit.”

“He’s not quite on zero aspect—yeah, he’s coming up a few degrees off our heading. He’s not sure

exactly where we are. He’s hunting.”

“He’ll be sure soon enough. Can we kill him?”

“With sidewinders?” Axis pauses articulately: the target is twenty thousand feet above us, and he

has a laser that can blind our missiles. “We’d have more luck bailing out and hiking.”

“All right. I’m gonna fly us out of this.”

“Sure.”

“Just check the gun.”

“Ten times already, Barb.”

When climate and economy and pathology all went finally and totally critical along the Gulf Coast,

the federal government fled Cabo fever and VARD-2 to huddle behind New York’s flood barriers.

We left eleven hundred and six local disaster governments behind. One of them was the Pear Mesa

Budget Committee. The rest of them were doomed.

Pear Mesa was different because it had bought up and hardened its own hardware and power. So

Pear Mesa’s neural nets kept running, retrained from credit union portfolio management to the

emergency triage of hundreds of thousands of starving sick refugees.

Pear Mesa’s computers taught themselves to govern the forsaken southern seaboard. Now they

coordinate water distribution, re-express crop genomes, ration electricity for survival AC, manage all

the life support humans need to exist in our warmed-over hell.

But, like all advanced neural nets, these systems are black boxes. We have no idea how they work,

what they think. Why do Pear Mesa’s AIs order the planting of pear trees? Because pears were their

corporate icon, and the AIs associate pear trees with areas under their control. Why does no one

make the AIs stop? Because no one knows what else is tangled up with the “plant pear trees”

impulse. The AIs may have learned, through some rewarded fallacy or perverse founder effect, that

pear trees cause humans to have babies. They may believe that their only function is to build

support systems around pear trees.

When America declared war on Pear Mesa, their AIs identified a useful diagnostic criterion for hostile

territory: the posting of fifty-star American flags. Without ever knowing what a flag meant, without

any concept of nations or symbols, they ordered the destruction of the stars and stripes in Pear Mesa

territory.

That was convenient for propaganda. But the real reason for the war, sold to a hesitant Congress by

technocrats and strategic ecologists, was the ideology of scale atrocity . Pear Mesa’s AIs could not be

modified by humans, thus could not be joined with America’s own governing algorithms: thus must

be forced to yield all their control, or else remain forever separate.

And that separation was intolerable. By refusing the United States administration, our superior

resources and planning capability, Pear Mesa’s AIs condemned citizens who might otherwise be

saved to die—a genocide by neglect. Wasn’t that the unforgivable crime of fossil capitalism? The

creation of systems whose failure modes led to mass death?

Didn’t we have a moral imperative to intercede?

Pear Mesa cannot surrender, because the neural nets have a basic imperative to remain online. Pear

Mesa’s citizens cannot question the machines’ decisions. Everything the machines do is connected in

ways no human can comprehend. Disobey one order and you might as well disobey them all.

But none of this is why I kill.

I kill for the same reason men don’t wear short skirts, the same reason I used to pluck my brows,

the reason enby people are supposed to be (unfair and stupid, yes, but still) androgynous with short

hair. Are those good reasons to do something? If you say no, honestly no—can you tell me you

break these rules without fear or cost?

But killing isn’t a gender role, you might tell me. Killing isn’t a decision about how to present your

own autonomous self to the world. It is coercive and punitive. Killing is therefore not an act of

gender.

I wish that were true. Can you tell me honestly that killing is a genderless act? The method? The

motive? The victim?

When you imagine the innocent dead, who do you see?

“Barb,” Axis calls, softly. Your own voice always sounds wrong on recordings—too nasal. Axis’ voice

sounds wrong when it’s not coming straight into my skull through helmet mic.

“Barb.”

“How are we doing?”

“Exiting one hundred and fifty knots north. Still in his radar but he hasn’t locked us up.”

“How are you doing?”

I cringe in discomfort. The question is an indirect way for Axis to admit something’s wrong, and that

indirection is obscene. Like hiding a corroded tail rotor bearing from your maintenance guys.

“I’m good,” I say, with fake ease. “I’m in flow. Can’t you feel it?” I dip the nose to match a drop-off

below, provoking a whine from the terrain detector. I am teasing, striking a pose. “We’re gonna be

okay.”

“I feel it, Barb.” But Axis is tense, worried about our pursuer, and other things. Doesn’t laugh.

“How about you?”

“Nominal.”

Again the indirection, again the denial, and so I blurt it out. “Are you dysphoric?”

“What?” Axis says, calmly.

“You’ve been hesitating. Acting funny. Is your—” There is no way to ask someone if their militarized

gender conditioning is malfunctioning. “Are you good?”

“I . . . ” Hesitation. It makes me cringe again, in secondhand shame. Never hesitate. “I don’t know.”

“Do you need to go on report?”

Severe gender dysphoria can be a flight risk. If Axis hesitates over something that needs to be done

instantly, the mission could fail decisively. We could both die.

“I don’t want that,” Axis says.

“I don’t want that either,” I say, desperately. I want nothing less than that. “But, Axis, if—”

The warning receiver climbs to a steady crow call.

“He knows we’re here,” I say, to Axis’ tight inhalation. “He can’t get a lock through the gown but

he’s aware of our presence. Fuck. Blinder, blinder, he’s got his laser on us—”

The fighter’s lidar pod is trying to catch the glint of a reflection off us. “Shit,” Axis says. “We’re

gonna get shot.”

“The gown should defeat it. He’s not close enough for thermal yet.”

“He’s gonna launch anyway. He’s gonna shoot and then get a lock to steer it in.”

“I don’t know—missiles aren’t cheap these days—”

The ESM mast on the Apache’s rotor hub, mounted like a lamp on a post, contains a cluster of

electro-optical sensors that constantly scan the sky: the Distributed Aperture Sensor. When the DAS

detects the flash of a missile launch, it plays a warning tone and uses my vest to poke me in the

small of my back.

My vest pokes me in the small of my back.

“Barb. Missile launch south. Barb. Fox 3 inbound. Inbound. Inbound.”

“He fired,” Axis calls. “Barb?”

“Barb,” I acknowledge.

I fuck—

Oh, you want to know: many of you, at least. It’s all right. An attack helicopter isn’t a private way of

being. Your needs and capabilities must be maintained for the mission.

I don’t think becoming an attack helicopter changed who I wanted to fuck. I like butch assertive

people. I like talent and prestige, the status that comes of doing things well. I was never taught the

lie that I was wired for monogamy, but I was still careful with men, I was still wary, and I could

never tell him why: that I was afraid not because of him, but because of all the men who’d seemed

good like him, at first, and then turned into something else.

No one stalks an attack helicopter. No slack-eyed well-dressed drunk punches you for ignoring the

little rape he slurs at your neckline. No one even breaks your heart: with my dopamine system tied

up by the reassignment surgery, fully assigned to mission behavior, I can’t fall in love with anything

except my own purpose.

Are you aware of your body? Do you feel your spine when you stand, your hips when you walk, the

tightness and the mass in your core? When you look at yourself, whose eyes do you use? Your own?

I am always in myself. I never see myself through my partner’s eyes. I have weapons to use, of

course, ways of moving, moans and cries. But I measure those weapons by their effect, not by their

similarity to some idea of how I should be.

Flying is the loop of machinery and pilot, the sense of your motion on the controls translated into

torque and lift, the airframe’s reaction shaping your next motion until the loop closes and machine

and pilot are one. Awareness collapses to the moment. You are always doing the right thing exactly

as it needs to be done. Sex is the same: the search for everything in an instant.

Of course I fuck Axis. A few decades ago this would’ve been a crime. What a waste of perfectly

useful behavior. What a waste of that lean muscled form and those perfect killing hands that know

me millimeter-by-millimeter system-by-system so there is no mystique between us. No “secret

places” or “feminine mysteries,” only the tortuously exact technical exercise of nerves and pressure.

Oxytocin released, to flow between us, by the press of knuckles in my cunt.

When I come beneath Axis I cry out, I press my body close, I want that utter loss of control that I

feel nowhere else. Heartbeat in arched throat: nipple beneath straining tongue. And my mind is

hyper-activated, free-associating, and as Axis works in me I see the work we do together. I see puffs

of thirty-millimeter autocannon detonating on night-cold desert floor.

Violence doesn’t get me off. But getting off makes me revel in who I am: and I am violent, made for

violence, alive in the fight.

Does that surprise you? Does it bother you to mingle cold technical discipline with hot flesh and

sweat?

Let me ask you: why has the worst insult you can give a combat pilot always been weak dick?

Have you ever been exultant? Have you ever known that you are a triumph? Have you ever felt that

it was your whole life’s purpose to do something, and all that you needed to succeed was to be

entirely yourself?

To be yourself well is the wholest and best feeling that anything has ever felt.

It is what I feel when I am about to live or die.

The Werewolf’s missile arches down on us, motor burned out, falling like an arrow. He is trying a

Shoot On Prospect attack: he cannot find us exactly, so he fires a missile that will finish the search,

lock onto our heat or burn through our stealth with its onboard radar, or acquire us optically like a

staring human eye. Or at least make us react. Like the catcaller’s barked “Hey!” to evoke the flinch

or the huddle, the proof that he has power.

We are ringed in the vortex of a dilemma. If we switch off the stealth gown, the Werewolf fighter will

lock its radar onto us and guide the missile to the kill. If we keep the stealth system on, the missile’s

heat-seeker will home in on the blazing plasma.

I know what to do. Not in the way you learn how to fly a helicopter, but the way you know how to

hold your elbows when you gesture.

A helicopter is more than a hovering fan, see? The blades of the rotor tilt and swivel. When you turn

the aircraft left, the rotors deepen their bite into the air on one side of their spin, to make off-center

lift. You cannot force a helicopter or it will throw you to the earth. You must be gentle.

I caress the cyclic.

The Apache’s nose comes up smooth and fast. The Mojave horizon disappears under the chin. Axis’

gasp from the front seat passes through the microphone and into the bones of my face. The pitch

indicator climbs up toward sixty degrees, ass down, chin up. Our airspeed plummets from a hundred

and fifty knots to sixty.

We hang there for an instant like a dancer in an oversway. The missile is coming straight down at

us. We are not even running anymore.

And I lower the collective, flattening the blades of the rotor, so that they cannot cut the air at an

angle and we lose all lift.

We fall.

I toe the rudder. The tail rotor yields a little of its purpose, which is to counter the torque of the

main rotor: and that liberated torque spins the Apache clockwise, opposite the rotor’s turn, until we

are nose down sixty degrees, facing back the way we came, looking into the Mojave desert as it rises

up to take us.

I have pirouetted us in place. Plasma fire blows in wraith pennants as the stealth system tries to

keep us modest.

“Can you get it?” I ask.

“Axis.”

I raise the collective again and the rotors bite back into the air. We do not rise, but our fall slows

down. Cyclic stick answers to the barest twitch of wrist, and I remember, once, how that slim wrist

made me think of fragility, frailty, fear: I am remembering even as I pitch the helicopter back and

we climb again, nose up, tail down, scudding backward into the sky while aimed at our chasing killer.

Axis is on top now, above me in the front seat, and in front of Axis is the chin gun, pointed sixty

degrees up into heaven.

“Barb,” the helicopter whispers, like my mother in my ear. “Missile ten seconds. Music? Glare?”

No. No jamming. The Werewolf missile will home in on jamming like a wolf with a taste for pepper.

Our laser might dazzle the seeker, drive it off course—but if the missile turns then Axis cannot take

the shot.

It is not a choice. I trust Axis.

Axis steers the nose turret onto the target and I imagine strong fingers on my own chin, turning me

for a kiss, looking up into the red scorched sky—Axis chooses the weapon (30MM GUIDED PROX AP)

and aims and fires with all the idle don’t-have-to-try confidence of the first girl dribbling a soccer ball

who I ever for a moment loved—

The chin autocannon barks out ten rounds a second. It is effective out to one point five kilometers.

The missile is moving more than a hundred meters per second.

Axis has one second almost exactly, ten shots of thirty-millimeter smart grenade, to save us.

A mote of gray shadow rushes at us and intersects the line of cannon fire from the gun. It becomes

a spray of light. The Apache tings and rattles. The desert below us, behind us, stipples with tiny

plumes of dust that pick up in the wind and settle out like sift from a hand.

“Got it,” Axis says.

“I love you.”

“Axis.”

Many of you are veterans in the act of gender. You weigh the gaze and disposition of strangers in a

subway car and select where to stand, how often to look up, how to accept or reject conversation.

Like a frequency-hopping radar, you modulate your attention for the people in your context: do not

look too much, lest you seem interested, or alarming. You regulate your yawns, your appetite, your

toilet. You do it constantly and without failure.

You are aces.

What other way could be better? What other neural pathways are so available to constant

reprogramming, yet so deeply connected to judgment, behavior, reflex?

Some people say that there is no gender, that it is a postmodern construct, that in fact there are

only man and woman and a few marginal confusions. To those people I ask: if your body-fact is

enough to establish your gender, you would willingly wear bright dresses and cry at movies, wouldn’t

you? You would hold hands and compliment each other on your beauty, wouldn’t you? Because your

cock would be enough to make you a man.

Have you ever guarded anything so vigilantly as you protect yourself against the shame of

gender-wrong?

The same force that keeps you from gender-wrong is the force that keeps me from fucking up.

The missile is dead. The Werewolf Apostle is still up there.

“He’s turning off.” Axis has taken over defensive awareness while I fly. “Radar off. Laser off. He’s

letting us go.”

“Afraid of our fighters?” The mercenaries cannot replace a lost J-20S. And he probably has a

wingman, still hiding, who would die too if they stray into a trap.

“Yes,” Axis says.

“Keep the gown on.” In case he’s trying to bluff us into shutting down our stealth. “We’ll stick to the

terrain until he’s over the horizon.”

“Can you fly us out?”

The Apache is fighting me. Fragments of the destroyed missile have pitted the rotors, damaged the

hub assembly, and jammed the control surfaces. I begin to crush the shrapnel with the Apache’s

hydraulics, pounding the metal free with careful control inputs. But the necessary motions also move

the aircraft. Half a second’s error will crash us into the desert. I have to calculate how to un-jam the

shrapnel while accounting for the effects of that shrapnel on my flight authority and keeping the

aircraft stable despite my constant control inputs while moving at a hundred and thirty knots across

the desert.

“Barb,” I say. “Not a problem.”

And for an hour I fly without thought, without any feeling except the smooth stone joy of doing

something that takes everything.

The night desert is black to the naked eye, soft gray to thermal. My attention flips between my left

eye, focused on the instruments, and my right eye, looking outside. I am a black box like the Pear

Mesa AIs. Information arrives—a throb of feedback in the cyclic, a shift of Axis’ weight, a dune crest

ahead—and my hands and feet move to hold us steady. If I focused on what I was doing it would all

fall apart. So I don’t.

“Are you happy?” Axis asks.

Good to talk now. Keep my conscious mind from interfering with the gearbox of reflexes below.

“Yeah,” I say, and I blow out a breath into my mask, “yeah, I am,” a lightness in my ribs, “yeah, I

feel good.”

“Why do you think we just blew up a school?”

Why did I text my best friend the appearance and license number of all my cab drivers, just in case?

Because those were the things that had to be done.

Listen: I exist in this context. To make war is part of my gender. I get what I need from the flight

line, from the ozone tang of charging stations and the shimmer of distant bodies warping in the

tarmac heat, from the twenty minutes of anxiety after we land when I cannot convince myself that I

am home, and safe, and that I am no longer keeping us alive with the constant adjustments of my

hands and feet.

“Deplete their skilled labor supply, I guess. Attack the demographic skill curve.”

“Kind of a long-term objective. Kind of makes you think it’s not gonna be over by election season.”

“We don’t get to know why the AIs pick the targets.” Maybe destroying this school was an accident.

A quirk of some otherwise successful network, coupled to the load-bearing elements of a vast

strategy.

“Hey,” I say, after a beat of silence. “You did good back there.”

“You thought I wouldn’t.”

“Barb.” A more honest yes than “yes,” because it is my name, and it acknowledges that I am the

one with the doubt.

“I didn’t know if I would either,” Axis says, which feels exactly like I don’t know if I love you

anymore . I lose control for a moment and the Apache rattles in bad air and the tail slews until I stop

thinking and bring everything back under control in a burst of rage.

“You’re done?” I whisper, into the helmet. I have never even thought about this before. I am cold,

sweat soaked, and shivering with adrenaline comedown, drawn out like a tendon in high heels, a

just-off-the-dance-floor feeling, post-voracious, satisfied. Why would we choose anything else? Why

would we give this up? When it feels so good to do it? When I love it so much?

“I just . . . have questions.” The tactical channel processes the sound of Axis swallowing into a dull

point of sound, like dropped plastic.

“We don’t need to wonder, Axis. We’re gendered for the mission—”

“We can’t do this forever,” Axis says, startling me. I raise the collective and hop us up a hundred

feet, so I do not plow us into the desert. “We’re not going to be like this forever. The world won’t be

like this forever. I can’t think of myself as . . . always this.”

Yes, we will be this way forever. We survived this mission as we survive everywhere on this hot and

hostile earth. By bending all of what we are to the task. And if we use less than all of ourselves to

survive, we die.

“Are you going to put me on report?” Axis whispers.

On report as a flight risk? As a faulty component in a mission-critical system? “You just intercepted

an air-to-air missile with the autocannon, Axis. Would I ever get rid of you?”

“Because I’m useful,” Axis says, softly. “Because I can still do what I’m supposed to do. That’s what

you love. But if I couldn’t . . . I’m distracting you. I’ll let you fly.”

I spare one glance for the gray helmet in the cockpit below mine. Politeness is a gendered protocol.

Who speaks and who listens. Who denies need and who claims it. As a woman, I would’ve pressed

Axis. As a woman, I would’ve unpacked the unease and the disquiet.

As an attack helicopter, whose problems are communicated in brief, clear datums, I should ignore

Axis.

But who was ever only one thing?

“If you want to be someone else,” I say, “someone who doesn’t do what we do, then . . . I don’t

want to be the thing that stops you.”

“Bird’s gotta land sometime,” Axis says. “Doesn’t it?”

In the Applied Constructive Gender briefing, they told us that there have always been liminal

genders, places that people passed through on their way to somewhere else. Who are we in those

moments when we break our own rules? The straight man who sleeps with men? The woman who

can’t decide if what she feels is intense admiration, or sexual attraction? Where do we go, who do we

become?

Did you know that instability is one of the most vital traits of a combat aircraft? Civilian planes are

built stable, hard to turn, inclined to run straight ahead on an even level. But a military aircraft is

built so it wants to tumble out of control, and it is held steady only by constant automatic feedback.

The way I am holding this Apache steady now.

Something that is unstable is ready to move, eager to change, it wants to turn, to dive, to tear away

from stillness and fly .

Dynamism requires instability. Instability requires the possibility of change.

“Voice recorder’s off, right?” Axis asks.

“Always.”

“I love doing this. I love doing it with you. I just don’t know if it’s . . . if it’s right.”

“Thank you,” I say.

“Barb?”

“Thank you for thinking about whether it’s right. Someone needs to.”

Maybe what Axis feels is a necessary new queerness. One which pries the tool of gender back from

the hands of the state and the economy and the war. I like that idea. I cannot think of myself as a

failure, as something wrong, a perversion of a liberty that past generations fought to gain.

But Axis can. And maybe you can too. That skepticism is not what I need . . . but it is necessary

anyway.

I have tried to show you what I am. I have tried to do it without judgment. That I leave to you.

“Are we gonna make it?” Axis asks, quietly.

The airframe shudders in crosswind. I let the vibrations develop, settle into a rhythm, and then I

make my body play the opposite rhythm to cancel it out.

“I don’t know,” I say, which is an answer to both of Axis’ questions, both of the ways our lives are in

danger now. “Depends how well I fly, doesn’t it?”

“It’s all you, Barb,” Axis says, with absolute trust. “Take us home.”

A search radar brushes across us, scatters off the gown, turns away to look in likelier places. The

Apache’s engine growls, eating battery, turning charge into motion. The airframe shudders again,

harder, wind rising as cooling sky fights blazing ground. We are racing a hundred and fifty feet

above the Larger Mojave where we fight a war over some new kind of survival and the planet we

maimed grows that desert kilometer by kilometer. Our aircraft is wounded in its body and in its

crew. We are propelled by disaster. We are moving swiftly.

#I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter by ISABEL FALL#I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter#ISABEL FALL#gender identity

40 notes

·

View notes

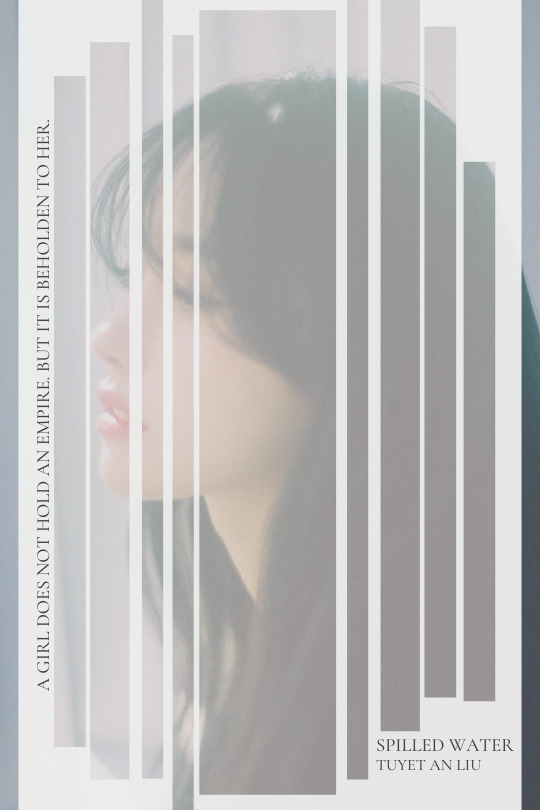

Photo

S P I L L E D W A T E R / D E E P O C E A N S

(a camp nano work in progress.)

a short story/novella duology focused on a triad princess, a triad heir, and their intertwined lives due to their respective roles in their families.

s p i l l e d w a t e r

parted lips, exposed wrists, lidded eyes, and pretty lies; these are the things men like.

a soft silk pillow cushioned carina’s knees from the hardwood floors of their traditional house. mother lounged on an intricate golden chair fitted with crimson-velvet covers and throw pillows; the midnight sky tumbled down her back in thick, soft curls and she ran graceful, thin fingers through the strands, checking for dry ends. her red-painted nails glistened beneath the evening light.

carina bo yok hong is the eldest child of the hong clan. in her father’s eyes, her talent for strategic violence will never eclipse her womanhood. the dragon head title she covets will fall to her incompetent secondborn brother instead while she becomes a wife to a man chosen by her father. but if she cannot choose her future, carina will undermine any attempts to stifle her potential.

d e e p o c e a n s

“is she blooded?”

he met her heavy gaze. “no one will say.”

out of fear or loyalty? her unasked questions hung in the air like the impenetrable humid summers in the south. wing hong’s eyes glided over the snow-dusted water gardens outside the windows where the fog sat low against the clear pond; a layer of white frost erased all nuances of color—a rebirth in waiting.

“no one will say,” he repeated.

antonio wing hong yeung is the heir to the yeung family. a tiger born once in every three generations, or so everyone says, and he’s in need of a wife before his succession as the dragon head. he doesn’t care for beauty or charms; he wants a vicious, cunning girl that will slit the throat of his enemies if needed. and carina bo yok hong seems to be the girl that suits his needs.

#sunsetdistrict&starfallisland#lxcuna#archistratego#merulia#writing#writeblr#spilled water & deep oceans#mine

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Temptations {Na Jaemin}

Pairing: Na Jaemin x Reader

Genre: Smut

Warnings: Cursing, unprotected sex, first time

Word Count: 1,058

"You're so beautiful," he whispered in your ear as his hand crawled down your bare abdomen. "You don't know how beautiful you are to me. You're the most beautiful thing in the world to me and I can't stop looking at you."

He brought his lips down on yours and softly kissed them. His hand lifted the thin elastic waistband of your panty and he rested his hand on top of your womanhood. The contact made you furrow your eyebrows in pleasure and you placed a hand to his face, pulling him in for a deeper kiss. He separated your folds with his index and middle fingers and began coating them with your juices, swirling them around. He broke the kiss and looked into your eyes.

"You're so wet already Y/N," he said with a smirk on his face. "How long have you been thinking about me doing that to you?"

You blushed and turned your face away from his. "Jaemin..."

He held your chin and swerved it back to look at him. "Yes baby?" He asked and flashed you his drop dead gorgeous smile.

You opened your mouth to finish your statement, but he inserted two of his fingers inside you. You gasped out loud and your face contorted from the intense feeling. He took in your expression and chuckled after you. You bit down on your lower lip, trying your best not to moan out loud, and he smirked. He knew perfectly well how to make you scream his name just the way he liked it.

"You take me so well Y/N," he whispered in your ear and began to thrust his fingers at a harsh pace in and out of your soaking cunt. "Wait until you feel my cock for the first time. You'll be begging me for seconds and thirds."

He placed his lips against your neck and painted it with his finest artwork of blues and purples. "Jaemin," you softly moaned his name. Your hand crawled up to the back of his head and your fingers got tangled into his luscious blue hair.

"Let's try that again. I didn't hear you the first time. A little louder for me baby," he growled and shoved his digits further in so that they were knuckle deep.

"AH! FUCK JAEMIN!" you shouted and he scoffed with a smirk on his face.

"That's more like it baby," he said and curled his fingers around your uterus lining when he felt your walls tightening on them. "Cum on my fingers and I will reward you with something even better." You didn't need telling twice for as soon as you reached your orgasm, you let your juices flow on his fingers. "Look at that." He pulled out his fingers, bringing them to his lips, and licked them clean. "Mm, so delicious."

You squeezed your knees together, the electric feeling still zapping through your core, and he ran his hand down to your knees. He pulled them apart and brought his hand back up to your underwear as he slid it down your legs. He stood up from off the floor and slipped out of his black sweatpants and boxers. His erection sprang up once it was free and he climbed onto the bed.

"Open wider princess," he demanded as he tapped your knees with his long fingers. "We're going to have so much fun tonight. Just you and me."

You spread your thighs apart and he crawled between them. He placed a hand on the bed next to your face, supporting himself, and brought his face closer to yours. He reached down with his other hand and grasped his cock firmly. He briefly met his lips with yours and lined his member with your entrance. You sucked in the air between your teeth and he slowly bottomed you out. Your hands automatically wrapped themselves around his back and you dug your nails into his skin. You dragged your nails from between his shoulder blades and down to his lower back.

"Shit," he cursed and groaned as the pain stung him for a few seconds. "That good, huh?" he teasingly asked and smirked. "Let's find out how many times you can cum in one night shall we?"

He started to roll his hips against yours at a slow speed and you allowed the blissful sensation to overtake your mind. Jaemin pressed his lips on yours and moved it to your cheek, before redirecting them towards your neck. You shut your eyes and squeezed them when you felt his pace picking up a notch. Your hands slid away from his back, leaving red lines behind, and gliding down to his elbows.

"You feel so good around my cock Y/N," he murmured.

He wriggled his elbows free from your hands, grabbed them, and pinned them above your head. His thrusts were now slamming perfectly into you and your eyes rolled to the back of your head. You had never experienced such a blissful state in your life and you wished it would never end. Jaemin grinned seeing you cage your lower lip between your teeth and used his strength to plow in you harder and deeper.

"HOLY SH-!" you gasped out loud and he repeated it, hitting your sensitive spot over and over. "JAEMIN!"

Your walls secured itself around his dick and he grunted. His cock throbbed and twitched and your insides were on fire; nerves going haywire. You knew he was on edge from the way he stuttered between his thrusts and you weren't far behind. He leaned his head back and parted his lips as he shut his eyes. His thick muscle moved on its own inside you and he groaned as hot streams of white liquid splattered your walls.

He tangled his fingers with yours and hid his face in the crook of your neck. "Cum for me baby," he said.

He strategically rubbed his pelvis, giving you the correct amount of friction needed, and you succumbed to your orgasm. He released one of your hands and caressed your leg, going up to your thigh, then stopping there. He waited until you found the right breathing pattern and kissed your lips.

"Did you enjoy it?" he asked and you nodded. "Good," he simply said and there was a malicious glint in his eyes. "Because I'm not done with you."

#na jaemin#jaemin#na jaemin smut#jaemin smut#nct#nct dream#jaemin scenario#nana#smut#nct dream scenario#dream smut#nct u#nct 127#na jaemin scenario#nct fanfiction#nct dream fanfiction#na jaemin fanfiction#jaemin fanfiction#dom jaemin#dom na jaemin

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being an agnostic is weird because every once in a while someone abhorrent dies and you find yourself hoping they’re burning in hell.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rereading Little Women as an Adult

Like plenty of other young girls on the verge of their first middle school dance, I read Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. It was a warm contrast to The Clique series and other young adult literature popular in the 2000s that centered on social snobbery and pettiness. The Little Women film (starring June Allyson) was also a staple in my house growing up, as I was not allowed to watch much mainstream media, most of all animated children’s films. However, none of the film adaptations ever gave me the same feeling I got from reading the book or made me want to give the book a reread. Until, of course, the newest version: Greta Gerwig’s 2019 adaptation. As most people read this story in childhood, I thought it would be interesting to reread Little Women as an adult and pitched the idea to my book club and it became our April read.

Rereading Little Women as an adult gave me a different perspective on the characters and the message Alcott was hoping to cultivate. Inadvertently, it was the perfect book to settle into at the beginning of the pandemic lockdown. The story and characters are heartwarming, wholesome, comforting during a pandemic where we all have to stay inside. In addition, the Marches’ story is one of survival. They are not wealthy and are living through the Civil War, already a time of financial difficulty and uncertainty. Their father, their only male family member, is away fighting for a good chunk of the story, and without him Marmee and the girls are vulnerable. The absence of March sons means that the girls have limited options for financial survival into adulthood. Meg worked as a governess before her marriage and Jo sells her short stories, but it is clear that neither is a long-term career with financial stability or independence. This societal and financial instability is parallel to the job-losses of the pandemic and

Amy has been much maligned as the worst March sister, but I heartily disagree. Amy is by far the best March. I blame the many movie adaptations for this portrayal. Amy is shown to be selfish and materialistic, which she definitely is, but no more than any other normal person is. Meg is just as selfish, but the movie adaptations do not explore it as much because she’s the oldest, and therefore a “second mother,” and cannot afford to indulge her petty luxuries. But reading the book, you can see that Meg likes to imagine herself as a martyr, and therefore keeps her selfish impulses to herself, lest she is seen as anything other than the perfect daughter (and later the perfect wife and the perfect mother). Amy’s contrast to the angelic Beth also makes her seem more selfish and nefarious than she really is. Beth clings to her image as a domestic angel on earth, even though she kills her bird by not feeding it for a week. With her painful shyness, exclusive love of the domestic, and dedication to good works, as evidenced by her many visits to the Hummel family, and her lack of ambition for literally anything, Beth slots into the Victorian ideal of the “angel in the house.” Her young death cements her status as a domestic martyr and helps to gloss over her lack of personality and that she killed her pet. Through her young marriage and motherhood, Meg can also be considered an “angel in the house,” but she will never reach Beth’s mythical perfection because she desires money and material comforts (what a bitch). Alcott sets Beth up to be The Best Sister™ but my hot take is that Beth is in fact, the worst character in the whole book. The most recent film adaptation is the only one, in my opinion, that does the character of Amy justice. We see her burn Jo’s collected fairy tales in a disproportionate childish rage, but we also see her calculate her family’s future and her important role in it, as the only one willing to “marry well.” The other films portray her strategic marriage designs as purely social climbing or gold-digging, but in Amy’s temporal context, there is not much she, or any of her sisters, can do to keep her family from going under financially, especially in the event of the death of her father. She has goals to be a great artist, but even if she did become one, it would realistically not pay the bills.

The two halves of Meg and Beth’s roles as “angels in the house” come together in Marmee, the mother of the March girls. She is more of a “mother” archetype than a real person. She always has the perfect lessons in wisdom at the right time and is simultaneously a gentle domestic goddess and an effective disciplinarian, even when her daughters are adults and no longer living at home. In the chapter “On the Shelf,” Marmee tells Meg that it is her fault that her husband spends all his evenings with his friend (and his friend’s young, childless wife) instead of with her and their children:

You have only made the mistake that most young wives make — forgotten your duty to your husband in your love for your children. A very natural and forgivable mistake, Meg, but one that had better be remedied before you take to different ways, for children should draw you nearer than ever, not separate you, as if they were all yours, and John had nothing to do but support them. I’ve seen it for some weeks, but have not spoken, feeling sure it would come right in time (322).

Marmee’s advice in this and all things always perpetuates the traditional gender norms that dictate that women should be quiet, gentle, and subservient, all while running an immaculate household. They should manage every situation and their husbands perfectly, but without ever letting their husbands feel managed, lest they should feel emasculated. The only advice that diverges from this is that Marmee tells Meg she should share childcare duties with her husband — a reasonable suggestion since they are his offspring as well. Marmee does limit these childcare duties to disciplining and teaching skills. Let’s not get crazy and ask John to change a diaper.

Someone in my book club pointed out that the messaging of Little Women seems particularly anti-feminist, even for the time it was published (1868) and I wish I had thought to say at the time that because this book was published in the United States, not Britain where I now live and attend book club meetings, the goalposts for what was “radical feminism” were very different. But of course, I did not think of this argument fast enough, and I will be bitter forever. If you look at the political debates — in the context of the pandemic or not — being held in the US vs the UK, you can see that much of American politics is deeply puritanical. It’s not surprising that these puritanical political ideals would be even more intense in 1868, especially since it was in the years directly following the American Civil War, a conflict about whether or not some people had a right not to be someone else’s property. The postwar political climate was all about the apportioning of rights to populations that previously had none or very few. It is certainly true that Little Women contains many outdated and problematic messages on gender roles and the meaning of womanhood, but it is important to remember that in the context of the experiences of white womanhood in the northern United States, Little Women was radical in its portrayal of young women and their individual approaches to domesticity. I enjoyed revisiting Little Women, but if I could expunge the memories of cringey middle school dances that came with it, I would.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

do you have any specific anti rupi kaur poetry opinions you wish to share? i just ask because I can't stand her poetry and it drives me crazy

Oh dear lord anon, I’ve kept quiet on my views of Rupi Kaur’s poetry for years because I wanted to avoid The Discourse - thank you for finally giving me an excuse!

Honestly, the best summation of my feelings on Rupi Kaur is in two very excellent articles. They’re both worth reading in their entirety, but I’ve included my favorite sections below.

No Filter, by Soraya Roberts

What is perhaps as consistent as the badness of Instapoetry—there are rare exceptions, Shire (who, it must be said, is more a Tumblr and Twitter poet, her Instagram being primarily made up of images and video) being one—is the general unwillingness to speak openly of its badness. Admirers focus on its genuine feeling, its emotional truth. Critics shrug it off, claiming it’s just not their thing. Which is basically how it was designed: Instagram was developed out of a project titled “Send the Sunshine” at Stanford’s Persuasive Technology Lab, not exactly a project intended to accommodate criticism. Though critical trepidation is a common consequence of the slippery definition of art—we once believed readymades sucked, too—part of this reluctance is also to do with the genre appealing predominantly to young women and haven’t young women been policed enough? Rupi Kaur herself wields this tack as a way to deflect excoriation, equating the criticism of her work to the criticism of marginalized demographics. Of the label “Instagram poet,” she told PBS, “A lot of the readers are young women who are experiencing really real things, and they’re not able to talk about it with maybe family or other friends, and so they go to this type of poetry to sort of feel understood and to have these conversations. And so, when you use that term, you invalidate this space that they use to heal and to feel closer to one another.” You also invalidate women of color as Kaur frames herself within a landscape of both female and immigrant oppression, a context in which judgment is tantamount to muting the disenfranchised. To the literary world, she has pronounced, “This is actually not for you. This is for that, like, seventeen-year-old brown woman in Brampton who is not even thinking about that space, who is just trying to live, survive, get through her day.” It is a savvy move, invalidating all manner of criticism before it has even been formulated.

But here it is: Her poetry, and much of Instapoetry, is poor. This poetry is not poor because it is genuine, it is poor because that is all it is. To do more than that, regardless of talent, requires time, and, by its very definition, Instapoetry has none. Ezra Pound’s epic collection of poems The Cantos took decades to complete. Maya Angelou has said she has found poetry the most challenging of all her professions: “When I come close to saying what I want to, I’m over the moon. Even if it’s just six lines, I pull out the champagne. But until then, my goodness, those lines worry me like a mosquito in the ear.” Even Rimbaud, who was already composing his best work in adolescence, conceded in his “Letter of the Seer,” “The poet makes himself a seer by a long, prodigious, and rational disordering of all the senses.” Time is what is required to think, the kind of thinking that allows the poet to imbue each individual word with a world of meaning. Harold Bloom described canonical writing as that which demands rereading, William Empson that it needs to work for readers with divergent opinions, provoking a variety of responses and interpretations. All of this implies a richness, a complexity, a variety of strata. The majority of Instapoetry has none of this. It is almost exclusively a banal vessel of self-care, equivalent to an affirmation, designed for young women of a certain privileged position and disposition, one that is entirely self-absorbed. The genre’s batheticisms remove specificity, to avoid alienation, supplanting them with the sort of platitude you find on a department store tea towel. Because this is what Instapoetry is—it is not art, it is a good to be sold, or, less, regrammed. Its value is quantity not quality.

The Problem with Rupi Kaur’s Poetry, by Chiara Giovanni

While more female South Asian voices are indeed needed in mainstream culture and media, there is something deeply uncomfortable about the self-appointed spokesperson of South Asian womanhood being a privileged young woman from the West who unproblematically claims the experience of the colonized subject as her own, and profits from her invocation of generational trauma. There is no shame in acknowledging the many differences between Kaur’s experience of the world in 2017 and that of a woman living directly under colonial rule in the early 20th century. For example: neither is any more “authentically” South Asian. But it is disingenuous to collect a variety of traumatic narratives and present them to the West as a kind of feminist ethnography under the mantle of confession, while only vaguely acknowledging those whose stories inspired the poetry.

…

Kaur’s strategic appeals to two different markets also inform the composition of her collection and her social media presence. While milk and honey contains several poems that, through coded words like “dishonor,” obliquely refer to Kaur’s cultural upbringing, that’s about as explicit as it gets: The poems are vague enough to provide identifiable prompts for readers from a variety of different cultural environments, including — in many cases — white Western readers. Thus the collection remains relatable — and, crucially, marketable — to a wider audience, while still retaining an element of culturally informed authenticity that forms much of Kaur’s brand. The few poems that specifically address race are positioned facing each other, a brief interlude in a collection that is otherwise devoid of racial politics, and once again addresses a white, Western audience in their appeal for recognition of South Asian beauty and resilience.

…