#science literacy

Text

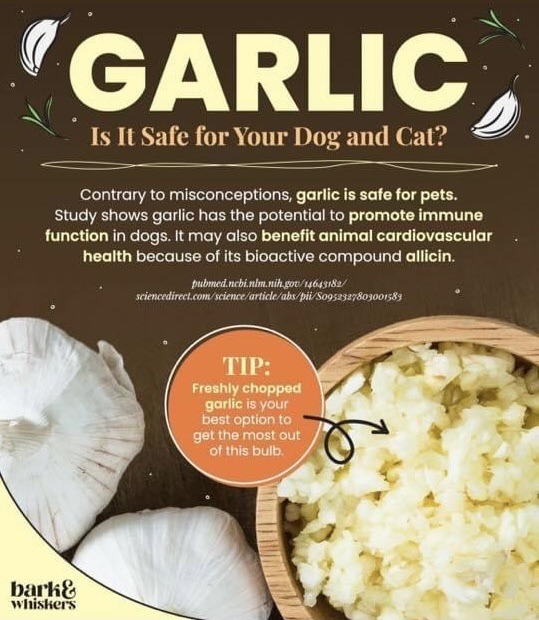

You know what I hate about the internet? Sometimes people will just lazily slap a “citation” on an infographic and trust that they’ll be completely taken at their word and nobody is going to dig deeper. And it works all the time. As an example, please look at this photo someone posted to dispute my assertion that garlic can be toxic to dogs.

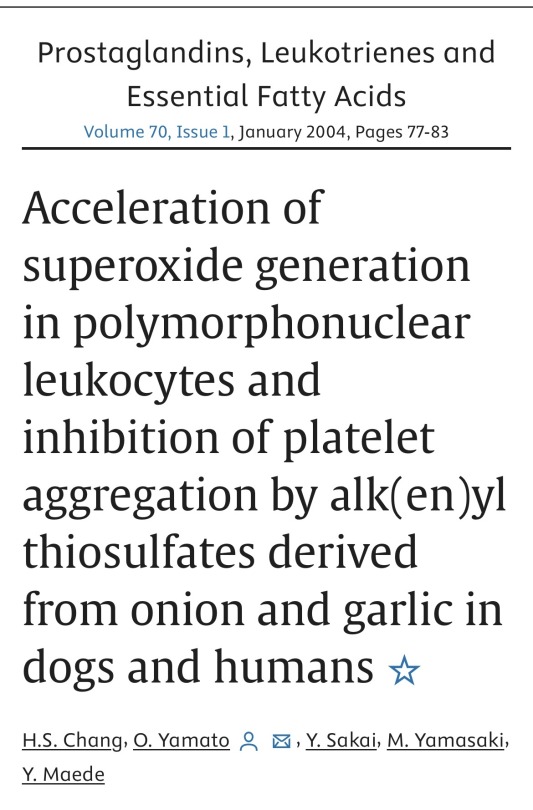

Okay well, kind of a pain to manually type in that link but obviously I am going to look into this study that is confident enough to recommend people feeding their dogs garlic. So here’s the article, kind of a weird journal choice for this graphic to reference from but looks like a legit (though 20 year old) study

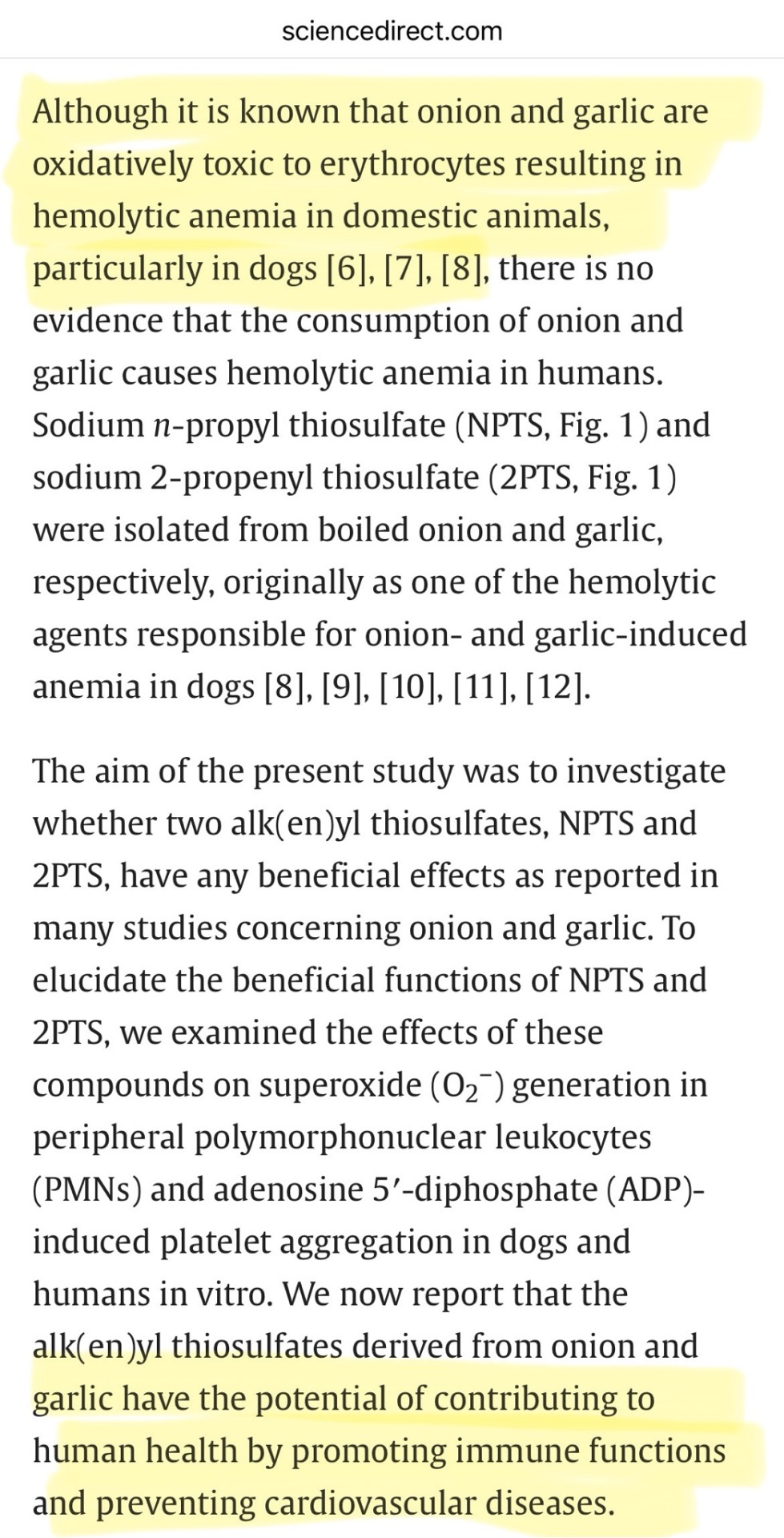

Funny thing is, almost immediately this article acknowledges that garlic can indeed be toxic to dogs. The health benefits mentioned in the graphic are referring to human health, not canine. This section is literally in the introduction of the article and one of the first things you read. Emphasis here is mine.

Crazy to me that someone would imply that this article encourages giving dogs garlic when it in fact immediately asserts that doing so has the potential to cause hemolytic anemia. The article does explore the anti-thrombotic effects of garlic components in dogs and humans, but by no means does it say that “contrary to misconceptions garlic is safe for pets”. It is dishonest to assert this in an infographic. However the creator of the image correctly assumed nobody would check, because the person who posted it took it as fact without further investigation.

I am begging you to be skeptical. Check your sources. Check their sources. Check my sources. Learn how to dig deeper and exercise that muscle as much as you can, especially on the internet. You will be absolutely shocked how much misinformation is casually stated and received as pure fact.

#scicomm#vetblr#veterinary medicine#I already know people are going to say they like giving their dogs garlic and will continue to do so- whatever pls just don’t tell me 😭#sorry if the link doesn’t work for you you may need access#dogs#pets#science literacy#biology

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Monsterverse Titan Phylogeny & Taxonomy

So, I was bored, and instead of studying for an upcoming test, I procrastinated and made a phylogenetic tree (a Tree of Life) and some proper scientific names for the Titans we have seen in the Monsterverse! The names in the official canon make no taxonomic sense. Titanus mosura and Titanus behemoth sound cool and all, but that implies that all the Titans are the same Genus, which.... no. Just, no.

I hope you guys enjoy it! I am always happy to answer any questions you have about it in the comments.

Scientific Names:

Shinomura - Parasitas collonium (parasitic colony)

Na Kika - Polypusoccult iridescentia (secret iridescent octopus)

Scylla - Lolligan testa (giant squid with legs)

Mothra - Vespulinea luxideu mosura (wasp light-god Mothra)

MUTO - Magnenator phagos (magnetic eater eater)

Amhuluk - Daemopampinus deceoculi (demon tendril with ten eyes)

Methuselah - Montivitae cornutum (living mountain with horns)

Skull Crawler - Reptant cranium (basic reptile skull)

Ion Dragon - Dracdum pisicut (fish-like ion dragon)

Tiamat - Serpensbellum tempestas (war serpent of storms)

Rodan - Pyranodon ventus (toothless winds of fire)

Doug - Deumigale optimum (best god gecko)

Shimo - Deureptilus glaciei (god reptile of the ice)

Godzilla - Deureptilia solis gojira (god reptile of the sun)

Behemoth - Dentesimia mehemot (tusked ape behemoth)

Frost Vark - Nasasidus fodiens (star nose digger)

Camazotz - Solhostis vespermortem (sun enemy death bat)

Skar King / Suko - Deupithepongo sapiens (wise god orangutan)

Kong - Deupithecus sapiens (wise god ape)

ALSO: Because Ghidorah is not of Earth, he wouldn't be ANYWHERE on a phylogenetic tree of Earth animals. Nowhere close at all. But his scientific name could be Interfectorum inanis (void killer).

#monsterverse#godzilla#legendary monsterverse#biology#taxonomy#Linnean classification#scientific names#science#proper science#phylogeny#phylogenetic tree#tree of life#doug#shimo#kong#skar king#discussion#science literacy#headcanons#rodan#mothra

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sci-fi books are rare in school even though they help kids better understand science

by Emily Midkiff, Assistant Professor of Teaching, Leadership, and Professional Practice at the University of North Dakota

Claudia Wolff

Science fiction can lead people to be more cautious about the potential consequences of innovations. It can help people think critically about the ethics of science. Researchers have also found that sci-fi serves as a positive influence on how people view science. Science fiction scholar Istvan Csicsery-Ronay calls this “science-fictional habits of mind.”

Scientists and engineers have reported that their childhood encounters with science fiction framed their thinking about the sciences. Thinking critically about science and technology is an important part of education in STEM – or science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Complicated content?

Despite the potential benefits of an early introduction to science fiction, my own research on science fiction for readers under age 12 has revealed that librarians and teachers in elementary schools treat science fiction as a genre that works best for certain cases, like reluctant readers or kids who like what they called “weird,” “freaky” or “funky” books.

Of the 59 elementary teachers and librarians whom I surveyed, almost a quarter of them identified themselves as science fiction fans, and nearly all of them expressed that science fiction is just as valuable as any other genre. Nevertheless, most of them indicated that while they recommend science fiction books to individual readers, they do not choose science fiction for activities or group readings.

The teachers and librarians explained that they saw two related problems with science fiction for their youngest readers: low availability and complicated content.

Why sci-fi books are scarce in schools

Several respondents said that there simply are not as many science fiction books available for elementary school students. To investigate further, I counted the number of science fiction books available in 10 randomly selected elementary school libraries from across the United States. Only 3% of the books in each library were science fiction. The rest of the books were: 49% nonfiction, 25% fantasy, 19% realistic fiction and 5% historical fiction. While historical fiction also seems to be in low supply, science fiction stands out as the smallest group.

When I spoke to a small publisher and several authors, they confirmed that science fiction for young readers is not considered a profitable genre, and so those books are rarely acquired. Due to the perception that many young readers do not like science fiction, it is not written, published and distributed as often.

With fewer books to choose from, the teachers and librarians said that they have difficulty finding options that are not too long and complicated for group readings. One explained: “I have to appeal to broad ability levels in chapter book read-aloud selections. These books typically have to be shorter, with more simple plots.” Another respondent explained that they believe “the kind of suppositions sci-fi is based on to be difficult for younger children to grasp. We do read some sci-fi in our middle grade book club.”

A question of maturity

Waiting for students to get older before introducing them to science fiction is a fairly common approach. Susan Fichtelberg – a longtime librarian – wrote a guide to teen fantasy and science fiction. In it, she recommends age 12 as the prime time to start. Other children’s literature experts have speculated whether children under 12 have sufficient knowledge to comprehend science fiction.

Reading researchers agree that comprehending complex texts is easier when the reader has more background knowledge. Yet, when I read some science fiction picture books with elementary school students, none of the children struggled to understand the stories. The most active child in my study often used his knowledge of “Star Wars” to interpret the books. While background knowledge can mean children’s knowledge of science, it also includes exposure to a genre. The more a reader is exposed to science fiction stories, the better they understand how to read them.

A matter of choice

Science fiction does not need to include detailed science or outlandish premises to offer valuable ideas. Simple picture books like “Farm Fresh Cats” by Scott Santoro rely on familiar ideas like farms and cats to help readers reconsider what is familiar and what is alien. “The Barnabus Project” by the Fan Brothers is both a simple escape adventure story and a story about the ethics of genetic experimentation on animals.

The good news is that elementary school students are choosing science fiction regardless of what adults might think they can or cannot understand. I found that the science fiction books in those 10 elementary school libraries were checked out at a higher rate per book than all of the other genres. Science fiction had 1-2 more checkouts per book, on average, than the other genres.

Using the lending data from these libraries, I built a statistical model that predicted that it is 58% more likely for one of the science fiction books to be checked out in these libraries than one of the fantasy books. The model predicted that a science fiction book is over twice as likely to be checked out than books in any of the other genres. In other words, since the children did not have nearly as many science fiction books to choose from, their readership was heavily concentrated on a few titles.

Children may discover science fiction on their own, but adults can do more to normalize the genre and provide opportunities for whole classes to become familiar with it. Encouraging children to explore science fiction may not guarantee science careers, but children deserve to learn from science fiction to help them navigate their increasingly high-tech world.

#science fiction#reading#science fiction books#education#k 12 education#literacy#science literacy#science fiction literature

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carl Sagan: There's two kinds of dangers.

One is what I just talked about, that we've arranged a society based on science and technology in which nobody understands anything about science and technology, and this combustible mixture of ignorance and power, sooner or later, is going to blow up in our faces. I mean, who is running the science and technology in a democracy if the people don't know anything about it?

And the second reason that I'm worried about this is that science is more than a body of knowledge. It's a way of thinking. A way of skeptically interrogating the universe with a fine understanding of human fallibility.

If we are not able to ask skeptical questions, to interrogate those who tell us that something is true, to be skeptical of those in authority, then we're up for grabs for the next charlatan political or religious who comes ambling along.

It's a thing that Jefferson laid great stress on. It wasn't enough, he said, to enshrine some rights in a Constitution or a Bill of Rights. The people had to be educated, and they had to practice their skepticism and their education. Otherwise we don't run the government—the government runs us.

Charlie Rose: Jefferson was amazing in his devotion to science.

Sagan: Absolutely.

Rose: We think of Jefferson as this man who was literate and who was a passionate articulator of freedom, but if you go to Monticello, what you appreciate is he was at heart a scientist, a botanist, an architect, geologist. And if you, Meriwether Lewis, as we now know from Steven Ambrose, he wanted him to go out and do experimentations and explore and be skeptical and find answers to passages and explore the West.

Sagan: Exactly right. And there was also an economic grail there if the northwest passage was found. Jefferson said that he was at heart a scientist, that he would have loved to have been a scientist. But there were certain events happening in America that called to him, and so he devoted his life to that kind of politics.

Rose: A revolution.

Sagan: Indeed. So that generations later people could be scientists.

#Carl Sagan#Charlie Rose#Thomas Jefferson#science literacy#science#skepticism#scepticism#truth claims#religion is a mental illness

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

So this fringe-source article came across my timeline on FB, and I’m wondering what the legit situation is with it—do you have any thoughts or better sources on it?

“Falcon shrine with cryptic message unearthed in Egypt baffles archaeologists: An ancient falcon shine in Berenike, an old port city in Egypt, has flummoxed archaeologists who aren't sure what to make of its headless falcons, unknown gods and cryptic message that reads, "It is improper to boil a head in here."

good lord imagine leading an article with that and then later literally having a paragraph that cites the team's fucking hypothesis from their own fucking paper.

the article: researchers baffled; nay, FLUMMOXED!!

the researchers, according to the same article:

"We hypothesize that the sacrificial animals were boiled before being presented to the god, perhaps to facilitate plucking their feathers, and that their heads were removed, according to the prescription on the stele," the team wrote in their paper.

like. my man. bro. owen jarus livescience contributor. are you mcfucking kidding me here.

so yeah, this is a stupid article even just because of that ~mysterious mysterieeees~ bait in the first paragraph. you have to know how to read between the lines to get an inkling of what's even happening here and many people just won't. it's vile, tbh, just write an upfront fucking article or shut the fuck up. but anyway. let's get to the actual science. which owen jarus livescience contributor should be aware of considering he cited the actual fucking paper (meaning he presumably read it) and still came up with this trash bullshit excuse of a bait article.

The find under discussion (term used very loosely) here is from 2019, and here's a link to the paper the team wrote on this, available to read for free. That's honestly the best source you can get; every time you come across an article like this and they give excerpts said to come from "the paper the team wrote"? Google a few keywords including "paper" or "abstract" to see if you can locate the original and just read that. Sometimes they'll link the actual paper and/or study (this one did, which is again interesting because that's probably the only scientific thing owen jarus livescience contributor did here), but usually you'll have to do your own digging.

This era of Egypt is not my specialty so I won't go into it too deeply myself, though I'm relatively confident talking about it because a) I read the paper and b) one of my own professors was involved and I remember a few preliminary online discussions on this.

Basically what is going on here is that we're looking at a late Roman Egypt cultic centre (with some, as Salima Ikram pointed out, really exciting in-situ finds) focussed on three gods, most notably a falcon god. The article states "two of the gods are enigmatic and unknown" (the third is Harpocrates, or Horus the Younger), but then describes them as "falcon-headed" and "a goddess with a headdress of cow's horns and a solar disk". While acknowledging the fact that the names are missing and we can't be sure about this since the specific attributes of either deity can apply to a few options, based on the peripherals we are most likely looking at Khonsu, Isis/Hathor/Isis-Hathor and Horus the Younger.

The interesting, not mysterious, thing about this find are the falcon remains. They're quite unique based on what we know of falconry/breeding and votive mummification of falcons from earlier periods, and so this is a matter of ongoing research. The stela itself is also interesting because the attested text is of a type (a prohibition) that hasn't been seen so far at Berenike.

I can absolutely recommend reading the full paper, it gives a really interesting discussion on the stela and its potential meaning, which presumably just registered as white noise in the brain of owen jarus livescience contributor because it wasn't sufficiently alike the plot of an indiana jones movie enough. The entire vibe of the paper is really just "scientists forming hypotheses based on available evidence" rather than "flummoxed archaeologists flailing squeamishly at decapitated falcons". The only flummoxed thing around these parts is the singular brain cell of owen jarus livescience contributor and his journalism degree. He deliberately left out information that is absolutely in the paper he himself linked with his own two hands to craft a more ~mysteriously baffling~ narrative that's far more likely to get clicks than the "hey check out these cool decapitated falcons we found in Berenike, quite unique actually!" an actual expert would've made of it.

So, bottom line, the article is a bit more properly sourced than one might expect from the phrasing, but I don't blame anyone for running doubt.exe on it. Actively encourage that, actually. Always look for the papers the media is reporting on rather than trusting the reporting!

94 notes

·

View notes

Link

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has not disproved the Big Bang, despite an article about a pseudoscientific theory that went viral in August, and which mischaracterized quotes from an astrophysicist to create a false narrative that the Big Bang didn't happen.

[...]

Nature wrote a piece on the research on July 27, in which Kirkpatrick said: "Right now I find myself lying awake at three in the morning, wondering if everything I've ever done is wrong." It's this quote that was later misused.

"It was a good quote!" Kirkpatrick said. "I try to be a pretty forthright person, and I meant what I said — that everything I had learned about the first galaxies based on previous telescopic data probably wasn't the complete picture, and now we have more data so we can refine our theories."

Kirkpatrick went back to her research and forgot about her quote. That was, until mid-August, when she received a text from a friend saying that there was an article — originally published by an organization called the Institute of Art and Ideas but now being republished on mainstream news sites — saying that JWST's observations of distant galaxies had disproved the Big Bang, which is not correct.

Worse still, the article had taken what Kirkpatrick had told Nature and misused it out of context to give the false impression that astrophysicists were panicking over the thought of the Big Bang theory being wrong.

The author of the article, an independent researcher named Eric Lerner, has been a serial denier of the Big Bang since the late 1980s, preferring his personal pseudoscientific alternative.

Continue Reading.

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sigh

Another day, another time we find out that courts are using psuedoscience to adjudicate vitally important disputes.

I feel like a science literacy class should be a requirement for becoming a judge.

7 notes

·

View notes

Link

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

instagram

0 notes

Text

Winter Weather Current Events and Curriculum Connections

Photo by Egor Kamelev on Pexels.com

There are many ways that you can connect with winter weather (snow, ice, albedo effects, winter storms, animal adaptations, and human winter culture) in any science class.

Biology and life science classes might explore: winter adaptations, winter ecosystem interactions, animal tracks in the snow, and using snow environmental DNA to track endangered…

View On WordPress

#albedo#astronomy#biology#chemistry#earth science#environmental science#ice#lesson plan ideas#olympics physics#polar vortex#Science#science articles#science current events#Science Discussions#Science Education#science literacy#science videos#snow#winter weather

0 notes

Text

Bad video but good book. You will learn how quacks and the media misuse and misrepresent science.

0 notes

Text

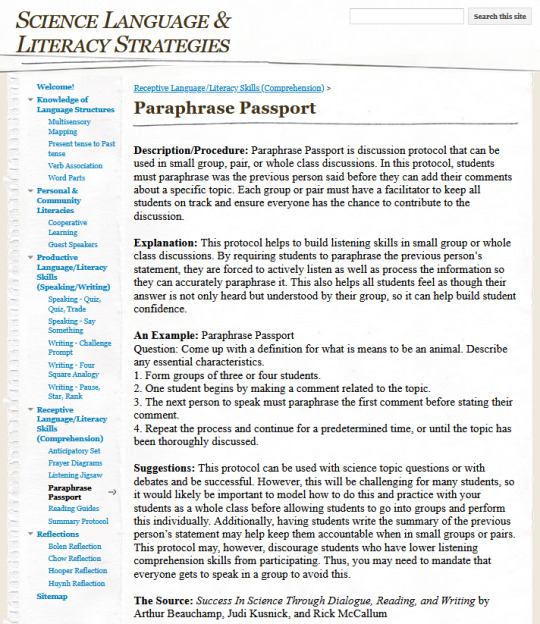

Paraphrase Passport activity

I found this at the Science Literacies Google Site as part of an assignment dealing with Literacy in my Pedagogy topic (although it seems to have pulled it from "Success in Science Through Dialogue, Reading and Writing" by Arthur Beauchamp, Judi Kisnick and Rick McCallum so that may be another source worth checking out on its own merits).

I like this one because it's on a page specifically about teaching literacy in science, which I know a lot of science teachers struggle with incorporating into their lessons. And because it teaches synthesis of knowledge rather than simple regurgitation which means the student will (hopefully) have a better understanding of what they're learning.

#education#education resource#science#science literacy#literacy#language and literacy#paraphrase passport#science education#teaching#science teaching#teacher resource

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why Feeding Wildlife is Dangerous

Originally posted on my blog at https://rebeccalexa.com/feeding-wildlife-dangerous/

Winter is here in the Northern Hemisphere, which means that wild animals of all sorts are falling back on cold weather adaptations that have evolved over countless generations. Some, like reptiles and amphibians, go into brumation or other hibernation-like states. Others have warm feathers or fur to insulate them as they go about their lives in chilly conditions. They may migrate around their territory in search of various food sources. Not all will survive these harsh months, which makes feeding wildlife to help them through the hard times a tempting idea.

Unfortunately, while this is a kind-hearted act born of good intentions, the impact is all too often harmful. Here are a few of the damaging, even deadly, effects of feeding wildlife.

First, let’s be a little more nuanced about the definition of wildlife in this case. I support the feeding of birds, at least those that commonly visit bird feeders. These birds are of species that are used to their food sources–like seeds, berries, and insects–being temporary, and so they retain their ability to forage for food in various places. Also, because the birds are not being fed by hand, and tend to retain their natural fear of humans, they are not likely to become habituated to us. It should go without saying that trying to convince birds to eat from your hand, or otherwise stop being afraid of you, is a bad idea (more about that in a minute.) And, of course, you need to make sure to keep your feeders clean and watch your local birds very carefully for any signs of disease; here’s an article I wrote on feeding birds safely and ethically.

Wild mammals, on the other hand, have a tendency to become dependent on human sources of food much more readily than birds. If you leave food scraps, pet food, or trash out where they can access it, they quickly figure out that this is an easy meal, and will hang around more than birds might.

Some birds will be more easily habituated than others; ducks and geese, for example, will lose their fear of humans as quickly as mammals do, especially when being fed regularly at ponds or lakes. So consider this article to primarily cover wild mammals, waterfowl, and any other animal that can be easily habituated through feeding.

A good example of what NOT to do.

Habituation is the biggest behavior change seen in fed wildlife. A habituated animal is simply one that no longer fears humans, and sees us as a source of food handouts. Unlike normal, healthy wildlife, these animals do not run away when a human approaches, even at a close distance. As mentioned above, this means they may even become aggressive in seeking food, and people have been bitten, scratched, gored, or otherwise injured by habituated animals. It may be easy to see why a habituated bear or moose is dangerous, but even smaller animals like squirrels or raccoons have a very nasty, painful bite or scratch. Some also carry zoonotic diseases that can be passed to humans; rabies is the most notorious, but even a bacterial infection caused by the bite or scratch can be an unpleasant experience.

But this lack of fear isn’t just a threat to us. It also puts the wildlife at risk. Wild mammals that wander through our neighborhoods in search of food are more likely to be hit by cars, attacked by outdoor dogs or cats, and injured or killed by cruel humans. If hunting is allowed in the area, the animal may walk right up to a hunter. Plus wild animals that become a nuisance or threat to people are sometimes euthanized, as relocated animals often end up finding their way back to their original territory, or go find a new group of humans to mooch off of.

Feeding wildlife can also cause them to cease natural foraging behaviors. Not only does this mean they may starve if the humans in the area stop feeding them, but they don’t teach their young proper foraging either, and so you may have animals several generations down the line that no longer know how to find natural food sources in the area.

Also, what we're feeding wildlife can kill them.

So here’s the thing: humans are omnivores. Actually, we’re sort of super omnivores; we have one of the most varied diets of any species, especially now that we’re able to grow all sorts of domesticated crops, including but not limited to two dozen cultivars of wild mustard (Brassica oleracea), various and sundry grains, legumes, tubers, etc. And because we’ve spread all throughout the planet, we’ve successfully sampled thousands upon thousands of edible animals, plants, and fungi. We’ve managed to evolve tolerances to substances some plants produce to keep from being eaten, like caffeine and capsaicin, and some of us go out of our way to seek them. We’ve also heavily altered some of our foods through cooking, to include some methods that render the food quite unhealthy even for us (not that that stops us from eating it anyway.)

All of this means that over 300,00 years of existence, Homo sapiens has evolved the ability to eat a truly mind-boggling array of foods. Unfortunately, even the other omnivores in our lives can’t necessarily tolerate the foods we eat. Domestic dogs evolved alongside us, eating first our refuse, and then sharing our meals, for thousands of years. Yet they still can’t safely eat chocolate, avocado, onions, or grapes, and some things we’ve created like the artificial sweetener xylitol can also be harmful–even deadly–to dogs.

So when you put out a plate of table scraps for your local squirrels, opossums, raccoons, or even bears, there’s a very good chance that something there is going to make them sick. You could even be sentencing one of your visitors to death! Even if they don’t immediately get sick, over time eating the wrong foods could seriously affect the health of wildlife, and may lead to sickness and an earlier, unpleasant death.

Sometimes, even something that seems like the “right” food can be deadly. Deer species in North America are adapted to eating lots of woody vegetation in winter; their gut microbiome is perfectly balanced to digest this tough food. However, some people like to feed them corn, either because they want to be nice, or because they want to hunt the deer. Unfortunately, the nutritional makeup of corn is very different from the deer’s winter fare. The carbohydrates in the corn can cause a condition called rumen acidosis. This overloading of carbs causes Streptococcus bacteria, which occur naturally in the deer’s chambered stomach, to overpopulate in a matter of hours. This raises the acidity of the stomach, and kills off many of the other microbes in the gut flora. This sudden imbalance essentially causes the stomach to stop digestion altogether. In a severe enough case, the deer dies a horribly painful death within twenty-four hours. Deer that survive often have permanently damaged stomachs, which can lead to worse health overall and a shortened lifespan.

Every ecosystem has adapted over thousands of years; in some cases, an ecosystem may be millions of years old (with some changes in species makeup, of course.) Over that time, species have evolved to keep each other’s numbers in check, whether through consuming each other, competing for resources, or spreading disease to other species as well as their own. One of the biggest limiting factors in a species’ habitat is the amount of food that’s available. You’ll generally have fewer large predators in a place than large herbivores, for example, because the land can support a lot more plants to feed herbivores than herbivores to feed carnivores.

So the ecosystem is able to keep its species in balance; any time a species begins to overpopulate, predation, starvation and disease tend to knock the numbers back. Some species even have “boom or bust” population cycles; lemmings, for example, are thought to have population fluctuations tied to the number of ermine preying on them in a given area.

But when we humans artificially change the availability of food in a given place, we can cause serious disruptions in these natural checks and balances. Put too much food in a place over time, and you end up with overpopulations of the animals that eat that food, with subsequent deaths from disease due to overcrowding, and starvation when the population inevitably outgrows even the artificially added food.

By John Davis, CCA-2.0

Speaking of disease, when feeding wildlife many people just dump the food in the same place every day or night, whether that’s pet bowls, a trash can, or a feeding site. This causes wildlife to congregate in unnaturally large numbers and on a regular basis, which again leads to increased disease transmission. Keep in mind that wildlife don’t have veterinarians they can just go to when sick, so you end up with wild animals dying some pretty slow, awful deaths due to these diseases. (And yes, this can happen with birds–again, why it is so incredibly important to properly clean your feeders regularly!)

I know it’s tempting to entice wildlife closer, and to want to help them through tough times. But it is incredibly important to keep a firm boundary between us and wild animals. We’ve already interfered in their lives and their behaviors enough. The more we meddle, the more harm we do to them, even if our intentions were good.

But wildlife are not pets. They are their own beings with their own lives and agendas, instincts and territories. They are, as Henry Beston wrote in The Outermost House, “not brethren, they are not underlings: they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.” And we respect them best when we give them their space and allow them to live as wild a life as possible in a world we have so dramatically changed.

If you want to create the best world for your local wildlife, create habitat and natural food sources for them. Remove invasive species, and plant more native plants, especially those that offer food and shelter to wildlife. (The native plant finder is a great starting point for those in the US.) Work to protect what wildlife habitat is left, especially habitats that are relatively undamaged like old-growth forests. This way you are helping to maintain space where these species can live the lives they have lived for many thousands of years without our interference.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#wildlife#nature#animals#wild animals#mammals#birds#winter#ecology#biology#zoology#naturecore#outdoors#animal behavior#nature literacy#long post#environment#environmentalism#conservation#science#scicomm

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Most people who believe in some "weird" thing like magic, ghosts, extraterrestrial visitors, cryptids, or whatever are not "anti-science." They generally believe that science is fundamentally correct about most things, but cannot adequately explain the "weird" thing they believe in.

If there is strong evidence against said weird thing, it's much more likely that they're just unaware of it, rather than being aware of it and actively choosing to disregard it. It's also more likely that they're unaware of scientific models that adequately explain it, rather than choosing to completely disregard said models.

Also, some people have genuinely had bizarre experiences that scientific models simply cannot explain yet. Like "three people in a small community independently had the exact same prophetic dream about an event they had no reason to expect" kind of bizarre. And when shit's this weird, the "scientific" explanations are just insultingly reductive.

Scientific literacy is good and should be encouraged, but being rude and dismissive to people who believe in "weird" things isn't the way to go. Most people who are into "weird" stuff tend to be curious by nature, so if you just present them with accessible scientific material that doesn't talk down to them, they'll often happily dive right in.

694 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Break The Science Barrier : Why Science Matters - Richard Dawkins

Break the Science Barrier is a TV documentary that I presented on Channel 4 in 1996. It argues for the importance, for society, of scientific ways of thinking. In it, I interviewed David Attenborough, Alec Jeffreys, who discovered DNA fingerprinting, and Douglas Adams, who gave a wonderful impromptu eulogy for science. I also interviewed a man who was wrongly convicted of murder because none of the lawyers, on either side, knew anything about science. The program ends on a more positive note – what I later came to call Science in the Soul.

-

"Like most scientists, I'm a realist, but I'm also a bit of a romantic. I appreciate that there are people who think they need something more than science can offer. Something, frankly, undefinable. But I think science does offer all we need. Not just to understand the 'how' of life, with its great richness and complexity. For me, science goes as far as we meaningfully can go towards answering the 'why' as well."

#Richard Dawkins#The Poetry of Reality#Break the Science Barrier#science#science literacy#what science is#science illiteracy#science illiterate#paranormal#superstition#creationism#creationist nonsense#religion is a mental illness

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

When reading an article I think it is important to ask yourself many questions about said article, these are just some I like to ask.

Is the information true?

Who verified its validity?

Was the verification process politically or economically motivated or inhibited?

Who benefits from the validity of the statement?

Who does not benefit from the validity of the statement

Can you verify it on your own?

Are there other ways to learn about the information that either confirms or denies its validity? (Repeat steps on new information)

Can the information ever be completely verified?

Are there many sides to take on this information and are those sides politically or economically motivated?

Do political or economic motivations make me want to believe or disbelieve this information? Why?

Is the information complete?

If we can verify the information is it enough to agree with a statement being made that’s utilizing the information.

Are there other verifiable pieces of information that may change my perspective given the validity of this current information?

Who benefits from the truth of this information?

Who doesn’t benefit from the truth of this statement?

Can the information ever be complete?

Does the information matter?

For example: When a country bombs a hospital does their reason for why matter when they targeted a hospital in the first place?

If the country proved their reason for bombing a hospital was valid would it change your stance on whether or not someone should bomb a hospital?

Do the laws for or against bombing hospitals change your mind when it comes to the position of hospital bombing?

What does the author want me to think about this information?

Is the author politically or economically motivated towards a position?

Do I agree with the authors political or economic motivations?

Can I parse the authors motivations?

Can I spot their position?

Can someone else help me spot the position of the author?

Are there other authors who have different positions?

Do I agree with their political or economic motivations?

105 notes

·

View notes