#russian invasion of ukraine (2022)

Text

youtube

#russian invasion of ukraine#russian invasion of ukraine map#russian invasion of ukraine every day#russian invasion of ukraine news#russian invasion of ukraine day 1#russian invasion of ukraine kings and generals#russian invasion of ukraine balkan mapping#russian invasion of ukraine 2022#russian invasion of ukraine countryballs#russian invasion of ukraine timelapse#russian invasion of ukraine map every day#russian invasion of ukraine animation#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Much of the public discussion of Ukraine reveals a tendency to patronize that country and others that escaped Russian rule. As Toomas Ilves, a former president of Estonia, acidly observed, “When I was at university in the mid-1970s, no one referred to Germany as ‘the former Third Reich.’ And yet today, more than 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, we keep on being referred to as ‘former Soviet bloc countries.’” Tropes about Ukrainian corruption abound, not without reason—but one may also legitimately ask why so many members of Congress enter the House or Senate with modest means and leave as multimillionaires, or why the children of U.S. presidents make fortunes off foreign countries, or, for that matter, why building in New York City is so infernally expensive.

The latest, richest example of Western condescension came in a report by German military intelligence that complains that although the Ukrainians are good students in their training courses, they are not following Western doctrine and, worse, are promoting officers on the basis of combat experience rather than theoretical knowledge. Similar, if less cutting, views have leaked out of the Pentagon.

Criticism by the German military of any country’s combat performance may be taken with a grain of salt. After all, the Bundeswehr has not seen serious combat in nearly eight decades. In Afghanistan, Germany was notorious for having considerably fewer than 10 percent of its thousands of in-country troops outside the wire of its forward operating bases at any time. One might further observe that when, long ago, the German army did fight wars, it, too, tended to promote experienced and successful combat leaders, as wartime armies usually do.

American complaints about the pace of Ukraine’s counteroffensive and its failure to achieve rapid breakthroughs are similarly misplaced. The Ukrainians indeed received a diverse array of tanks and armored vehicles, but they have far less mine-clearing equipment than they need. They tried doing it our way—attempting to pierce dense Russian defenses and break out into open territory—and paid a price. After 10 days they decided to take a different approach, more careful and incremental, and better suited to their own capabilities (particularly their precision long-range weapons) and the challenge they faced. That is, by historical standards, fast adaptation. By contrast, the United States Army took a good four years to develop an operational approach to counterinsurgency in Iraq that yielded success in defeating the remnants of the Baathist regime and al-Qaeda-oriented terrorists.

A besetting sin of big militaries, particularly America’s, is to think that their way is either the best way or the only way. As a result of this assumption, the United States builds inferior, mirror-image militaries in smaller allies facing insurgency or external threat. These forces tend to fail because they are unsuited to their environment or simply lack the resources that the U.S. military possesses in plenty. The Vietnamese and, later, the Afghan armies are good examples of this tendency—and Washington’s postwar bad-mouthing of its slaughtered clients, rather than critical self-examination of what it set them up for, is reprehensible.

The Ukrainians are now fighting a slow, patient war in which they are dismantling Russian artillery, ammunition depots, and command posts without weapons such as American ATACMS and German Taurus missiles that would make this sensible approach faster and more effective. They know far more about fighting Russians than anyone in any Western military knows, and they are experiencing a combat environment that no Western military has encountered since World War II. Modesty, never an American strong suit, is in order.

— Western Diplomats Need to Stop Whining About Ukraine

#eliot a. cohen#current events#politics#ukrainian politics#american politics#warfare#strategy#tactics#diplomacy#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#war in afghanistan#vietnam war#ukraine#usa#toomas hendrik ilves

477 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIME's 2022 Heroes l Person of the Year

Only in the darkness can you see the stars. —Martin Luther King Jr.

#time magazine#december#2022#human rights#women rights#women life freedom#iran#iranian women#ukraine#russia#war#russian invasion#volodymyr zelensky#masha amini#timepoy

971 notes

·

View notes

Text

On war’s second anniversary, Ukraine’s scientific community mourns lost colleagues

As an expert on river ecosystems with the Institute of Hydrobiology, Shevtsova in the 1970s and ’80s traveled frequently for fieldwork to diverse locales including Poland, Iraq, and Libya—a rare privilege for a Soviet scientist. “She was a tiny woman, but always elegant. She was nicknamed ‘Hummingbird,’” Natalia Shevtsova says. At 75, long past the customary retirement age, Lyudmila Shevtsova joined the ecology faculty at National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Up until the end, “she was still quite intellectually engaged with students and other faculty members. And so friendly—always smiling,” says ecologist Viktor Karamushka, who chairs the university’s Department of Environmental Studies.

Lyudmila Shevtsova wanted her granddaughters, like their mother, to follow in her footsteps and study hydrobiology. They demurred. “I told her I had another vision for my life,” says Daryna Gulei. But when Gulei, 28, phoned her grandmother on 27 December 2023 to say she would defend her Ph.D. in architecture the next day at Kyiv National University of Construction and Architecture, “She was so happy! She read my dissertation twice, gave me some questions.” Gulei shared the good news of her successful defense the last time they spoke.

On 2 January, Gulei and her husband sped across Kyiv to the apartment building after her mother called to say they’d been hit. Dawn was breaking over a melee of firefighters, paramedics, and shaken residents. “I felt my grandmother close by,” Gulei says, and just then a paramedic emerged from the building carrying Lyudmila Shevtsova. Her body was riddled with shrapnel, and she had lost a lot of blood, but she was still breathing.

Natalia says her mother was fading fast and could not speak. “But it was clear she understood I was alive. I hope that gave her some comfort,” Natalia says. “Then my dear mother turned her head away, and died.”

#current events#science#academia#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#ukraine#russia#liudmyla shevtsova#volodymyr kozlovskyy#igor galkin

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine that someone—perhaps a man from Florida, or maybe even a governor of Florida—criticized American support for Ukraine. Imagine that this person dismissed the war between Russia and Ukraine as a purely local matter, of no broader significance. Imagine that this person even told a far-right television personality that “while the U.S. has many vital national interests ... becoming further entangled in a territorial dispute between Ukraine and Russia is not one of them.” How would a Ukrainian respond? More to the point, how would the leader of Ukraine respond?

As it happens, an opportunity to ask that hypothetical question recently availed itself. The chair of the board of directors of The Atlantic, Laurene Powell Jobs; The Atlantic’s editor in chief, Jeffrey Goldberg; and I interviewed President Volodymyr Zelensky several days ago in the presidential palace in Kyiv. In the course of an hour-long conversation, Goldberg asked Zelensky what he would say to someone, perhaps a governor of Florida, who wonders why Americans should help Ukraine.

Zelensky, answering in English, told us that he would respond pragmatically. He didn’t want to appeal to the hearts of Americans, in other words, but to their heads. Were Americans to cut off Ukraine from ammunition and weapons, after all, there would be clear consequences in the real world, first for Ukraine’s neighbors but then for others:

If we will not have enough weapons, that means we will be weak. If we will be weak, they will occupy us. If they occupy us, they will be on the borders of Moldova and they will occupy Moldova. When they have occupied Moldova, they will [travel through] Belarus and they will occupy Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. That’s three Baltic countries which are members of NATO. They will occupy them. Of course, [the Balts] are brave people, and they will fight. But they are small. And they don’t have nuclear weapons. So they will be attacked by Russians because that is the policy of Russia, to take back all the countries which have been previously part of the Soviet Union.

And after that, if there were still no further response? Then, he explained, the struggle would continue:

When they will occupy NATO countries, and also be on the borders of Poland and maybe fight with Poland, the question is: Will you send all your soldiers with weapons, all your pilots, all your ships? Will you send tanks and armored vehicles with your young people? Will you do it? Because if you will not do it, you will have no NATO.

At that point, he said, Americans will face a different choice: not politicians deciding whether “to give weapons or not to give weapons” to Ukrainians, but instead, “fathers and mothers” deciding whether to send their children to fight to keep a large part of the planet, filled with America’s allies and most important trading partners, from Russian occupation.

But there would be other consequences too. One of the most horrifying weapons that Russia has used against Ukraine is the Iranian-manufactured Shahed drone, which has no purpose other than to kill civilians. After these drones are used to subdue Ukraine, Zelensky asked, how long would it be before they are used against Israel? If Russia can attack a smaller neighbor with impunity, regimes such as Iran’s are sure to take note. So then the question arises again: “When they will try to occupy Israel, will the United States help Israel? That is the question. Very pragmatic.”

Finally, Zelensky posed a third question. During the war, Ukraine has been attacked by rockets, cruise missiles, ballistic missiles—“not hundreds, but thousands”:

So what will you do when Russia will use rockets to attack your allies, to [attack] civilian people? And what will you do when Russia, after that, if they do not see [opposition] from big countries like the United States? What will you do if they will use rockets on your territory?

And this was his answer: Help us fight them here, help us defeat them here, and you won’t have to fight them anywhere else. Help us preserve some kind of open, normal society, using our soldiers and not your soldiers. That will help you preserve your open, normal society, and that of others too. Help Ukraine fight Russia now so that no one else has to fight Russia later, and so that harder and more painful choices don’t have to be made down the line.

“It’s about nature. It’s about life,” he said. “That’s it.”

#current events#warfare#politics#russian politics#american politics#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#ukraine#usa#volodymyr zelenskyy#ron desantis#nato

245 notes

·

View notes

Video

All Along The Watchtower

Brothers in arms on an observation post watching for the enemy.

#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#2022 russia-ukraine news#ukraine#russia#brothers in arms#cat#caturday#cats on tumblr#friends#friends forever#friends for life#all along the watchtower#war#world at war#peace#peace for all#peace for ukraine

482 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey tankies, and assorted num nuts you think this is ok?

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

War In Ukraine

#hard times#war time#war photography#war 2022 2023#war 2022#ukraine#ukrainians#save ukraine#pray for ukraine#pray for ukrainian armed forces#pray for ukrainian soldiers#pray for ukrainians#stand with ukraine#war in ukraine#russia invaded ukraine#russian invasion on ukraine#war#stop war#war is hard#faces#emotions#ukrainians on tumblr#ukraine under attack#укр тумбочка#unbreakable ukrainians

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

#україна#ukraine#war in ukraine#russian invasion of ukraine#ukrainian genocide#russo ukrainian war#food shortage 2022#food shortages

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wanna see how Lviv looks like during wartime blackout? I got you covered! Photos taken on the day Kherson city was liberated, so many ppl were celebrating outside with lots of street music and singing!

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

tchaikovsky didn't even live in the russian federation lmao the russian empire was a whole different state. can't believe tchaikovsky came back from the dead to support an invasion that happened over a century after his death done by a state that didn't even exist when he was alive. shame on him

#if you were boycotting tchaikovsky for the imperialism of the russian empire that would make more sense tho im not sure what the point of#culturally boycotting a dead empire that's already fallen is#doesnt have anything to do with the 2022 invasion of ukraine though lol

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once again Zaporizhia is under missile attacks. In the video, a direct hit of a missile on a residential building

russia does this on purpose.

There's no mistake. Their servicemen enter coordinates of residential areas in Ukrainian cities an hit them to make more people flee, to create uncertainty and sow terror.

russians support these actions en masse.

russia is terrorist state.

#stand with ukraine#war in ukraine#ukraine war#ukraine 2022#ukraine#russia terrorist state#russian crimes#russian invasion#fuck putin

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the terrible winter of 1932–33, brigades of Communist Party activists went house to house in the Ukrainian countryside, looking for food. The brigades were from Moscow, Kyiv, and Kharkiv, as well as villages down the road. They dug up gardens, broke open walls, and used long rods to poke up chimneys, searching for hidden grain. They watched for smoke coming from chimneys, because that might mean a family had hidden flour and was baking bread. They led away farm animals and confiscated tomato seedlings. After they left, Ukrainian peasants, deprived of food, ate rats, frogs, and boiled grass. They gnawed on tree bark and leather. Many resorted to cannibalism to stay alive. Some 4 million died of starvation.

At the time, the activists felt no guilt. Soviet propaganda had repeatedly told them that supposedly wealthy peasants, whom they called kulaks, were saboteurs and enemies—rich, stubborn landowners who were preventing the Soviet proletariat from achieving the utopia that its leaders had promised. The kulaks should be swept away, crushed like parasites or flies. Their food should be given to the workers in the cities, who deserved it more than they did. Years later, the Ukrainian-born Soviet defector Viktor Kravchenko wrote about what it was like to be part of one of those brigades. “To spare yourself mental agony you veil unpleasant truths from view by half-closing your eyes—and your mind,” he explained. “You make panicky excuses and shrug off knowledge with words like exaggeration and hysteria.”

He also described how political jargon and euphemisms helped camouflage the reality of what they were doing. His team spoke of the “peasant front” and the “kulak menace,” “village socialism” and “class resistance,” to avoid giving humanity to the people whose food they were stealing. Lev Kopelev, another Soviet writer who as a young man had served in an activist brigade in the countryside (later he spent years in the Gulag), had very similar reflections. He too had found that clichés and ideological language helped him hide what he was doing, even from himself:

I persuaded myself, explained to myself. I mustn’t give in to debilitating pity. We were realizing historical necessity. We were performing our revolutionary duty. We were obtaining grain for the socialist fatherland. For the five-year plan.

There was no need to feel sympathy for the peasants. They did not deserve to exist. Their rural riches would soon be the property of all.

But the kulaks were not rich; they were starving. The countryside was not wealthy; it was a wasteland. This is how Kravchenko described it in his memoirs, written many years later:

Large quantities of implements and machinery, which had once been cared for like so many jewels by their private owners, now lay scattered under the open skies, dirty, rusting and out of repair. Emaciated cows and horses, crusted with manure, wandered through the yard. Chickens, geese and ducks were digging in flocks in the unthreshed grain.

That reality, a reality he had seen with his own eyes, was strong enough to remain in his memory. But at the time he experienced it, he was able to convince himself of the opposite. Vasily Grossman, another Soviet writer, gives these words to a character in his novel Everything Flows:

I’m no longer under a spell, I can see now that the kulaks were human beings. But why was my heart so frozen at the time? When such terrible things were being done, when such suffering was going on all around me? And the truth is that I truly didn’t think of them as human beings. “They’re not human beings, they’re kulak trash”—that’s what I heard again and again, that’s what everyone kept repeating.

— Ukraine and the Words That Lead to Mass Murder

#anne applebaum#ukraine and the words that lead to mass murder#current events#history#politics#russian politics#sociology#psychology#communism#warfare#totalitarianism#propaganda#holodomor#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#ukraine#viktor kravchenko#lev kopelev#vasily grossman#kulaks

263 notes

·

View notes

Text

it’s been a year.

it’s been a year since the worst day of my life.

February 24, 2022

a year of pain, death and darkness.

fuck you russia.

#russian invasion of ukraine (2022)#fuck putin#fuck russian fascism#fuck all the russian supporters#russia is a terrorist state#❤️🇺🇦#anz speaks

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

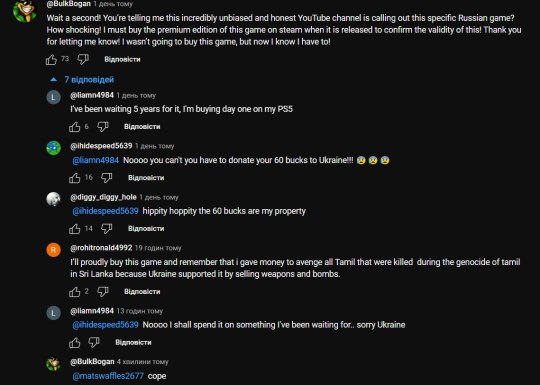

Atomic Heart

Tumor of the gaming industry

If something annoys you, don't associate yourself with it, just ignore it. In this case, I cannot do so. Criticism should extend to all works and be objective. Therefore, here is my objective criticism of a game that I have not played and do not intend to play, but about which I have seen, heard and read enough to give an evaluative judgment. I allow myself this also because I have lived next to a terrorist country all my life, I have a direct idea of its population and its manipulation of historical facts. And that's why I have something to say about this game.

I will not talk about the fact that art is not outside of politics. Whoever wanted it realized it. Whoever wants to remain blind will remain so forever. Let's talk about a spherical artwork in a vacuum. Each work is created with a purpose: to entertain you, to let you live some experience or emotions, or maybe the author shares their own experience, illuminates their own experiences and even traumas. It follows that each work has a certain meaning. I'm not talking exclusively about games, but about the field of art in general. Games can be a bit more complicated, because in addition to AAA with deep plot/content/lore, we also have simpler games designed to have a good time. But this does not mean that there are no "high matters" in them.

Most of the reviews and feedback on the game that I come across focus on the gameplay and its mechanics, how pleasant or fun it is to play the game. I know that people play for different reasons and that everyone has a preference for what is most important to them in the game. But if for you the whole essence, the whole meaning of the work is lost because you are only interested in running and shooting, then you are no different from people who do not understand games and even hate them, considering them to be children's toys and a waste of time. Because this is exactly what you are doing - playing and wasting your time without trying to evaluate the game from other sides. This is most of the reviews on Atomic Heart:

"The game looks fun, I'm buying". In my diploma, I did not claim that games are art. I was just trying to prove on the basis of what a video game can be considered an art form. However, the closing paragraph of my paper suggests that it will be a long time before people realize this. One of the reasons for this is a prejudiced attitude towards games as something a priori frivolous. And such individuals contribute to this without their own knowledge. In the Atomic Heart promo videos, there are no significant hints about the plot or its essence, the story or the issues are not revealed in any way. Game promos are dynamic videos that dazzle with their brightness and absurdity and, of course, captivate the depraved Western player with the totalitarian aesthetics of the soviet union. Such components of the visual part make it close to a propaganda poster: a screaming slogan, clear and understandable symbolism, a carefully hidden propaganda direction, a call to action (in this case, murder). The purpose of the game is not to give you an experience, not to evoke certain emotions or to reflect the trauma of an entire generation of people destroyed by the cannibalistic regime of the soviet union. The goal of the game is to capture your imagination, as a shiny speck captures the mind of a child, to play on your emotions and idea of what the soviet union is.

Do you want to know what the Soviet Union is? Please, I will do it for you for free, not for 40 bucks, which the game costs:

Victims of hunger on the streets of Kharkiv - the capital of the USSR, 1933. Photo author - Alexander Vinerberger

On April 17, 1938, the most prominent representatives of the Crimean Tatar nation —writers, historians, public figures, artists, teachers—were shot. By order from Moscow, on May 18, 1944, NKVD soldiers herded almost the entire Crimean Tatar population into railway cars and sent them to Uzbekistan. Sourse

Crimean Tatars during repeated eviction from Crimea in the 1960s

One of the first pictures of the destroyed reactor of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in 1986. Photo by V. Repik from the archive of the Ukrinform website

russian attack on the Dnipro on 14.01, 2023. That's how you do it, right?

What, doesn't sound like a rosy future? Ask the Uyghurs in China if they have a bright future. Ask the people of North Korea if they feel happy in their utopia. Ask the national minorities of russia what it's like to be a raw appendage of the empire.

In the game, you play as a KGB agent. Do you know what the State Security Committee of the USSR is, as a representative of which you play? This is a state body whose task was to destroy the "enemies" of the regime, that is, all citizens who fell under the definition of a state traitor. In order to become a traitor of the USSR, you need to do a little. For example, all you have to do is write a poem in your own language, in which you would express your love for your own land. Or organize a literary evening (undercover, of course) dedicated to the artists of your country. It sounds like something far away. But try to imagine how your favorite singer is stuffed into a black car, driven to an unknown destination, and then beaten to the point of kidney failure, while the YouTuber whose video you watched 5 minutes ago is shot dead in a nearby cell. It sounds like I'm exaggerating. But in Ukraine, we have a separate concept of Shooted Revival or Red Renaissance (Executed Renaissance). It was a whole generation of young artists, destroyed by the Soviet authorities for their pro-Ukrainian position. Actually, they did not resist the authorities and did not express any protests. They only created in the vein of national art, which the USSR considered a threat to its security and regime. KGB agents were executioners whose job was to destroy these people morally and physically. If the USSR appears as such an utopia in the game, why does such a state body as the KGB still exist in it?

The Krushelnytskys are a family of Ukrainian intellectuals, whose representatives have gained recognition in the fields of literature, medicine, painting, economics, music, social and political activities, etc. In 1934-37, most of the family members in the photo were repressed and executed.

I recently started playing Return to Castle Wolfenstein. I can't imagine that instead of a Polish-Jewish character resisting the Third Reich, I would play as an SS Oberführer. Let's just imagine such a game: Nazi Germany won the Second World War, red flags with swastikas are growing everywhere instead of national flags, and on the horizon you can see the chimneys of furnaces where traitors who disagree with the regime are burning. You have to play as a concentration camp warden, and investigate a strange case of malfunctions in one of the gas chambers in the research center. On your way, you encounter humanoid robots and all kinds of monsters, designed by the best engineers of the Reich. Everyone loves the aesthetics of Nazi Germany with its black uniforms and neo-Roman architecture. But I'm not sure that I would even have the morale to watch the trailer of such a game. The given example seems so banal and idiotic even to me. But Atomic Heart is a 1 in 1 story, which does not cause any dissonance for a huge number of people. And for some people even on the contrary, it seems fun, exciting and aesthetically appealing.

What is the point of this game? It only once again highlights how well Soviet propaganda worked, because people in the post-soviet space (especially in russia) still feel longing for the Age of Terror, scarcity, hunger and total control. I understand why young people my age and younger see nothing wrong with such a game and its narratives. Because they do not know what a totalitarian regime is. There are no stories in their families about grandparents who ate their children to survive. There are no memories of tortured relatives for a poem. They don't know what it's like to stand in line for an hour for a piece of bread, when the streets are littered with bloated bodies, or shot for stealing three ears of corn for their own children. They have healthy family members who have never suffered from radiation sickness. They have no relatives, deported to the most distant, coldest corners of the world, doomed to a slave existence for generations.

Atomic Heart's raison d'être is a mockery of human dignity, memory and common sense. This game is a cancer of the gaming industry, which proves that all gamers are unscrupulous moral bastards, willing to give their money to terrorists for a nice shiny wrapper. And if you play this game, I'm not saying you're stupid. I'm not telling you what games you should play. Your moral choice is just your moral choice. And if you are comfortable with being brainwashed and having flowing blood of my compatriots on your hands, that is your right. But don't be sorry when russia comes to you with a nuclear bomb that you sponsored.

Yeah, buddy. Keep it up

#gaming#games#videogames#video games#video game review#atomic heart#genocide#russian invasion of ukraine (2022)#ukraine war#russian war crimes#russia is a terrorist state#ussr history#soviet union#jensen ackles#my articles

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wagner Group mercenaries marched 800 kilometers across Russia, shot down planes and helicopters, took over a regional military command, provoked a panic in Moscow—troops dug trenches, the mayor told everyone to stay home—and then stood down. Yet in a way, the strangest aspect of Saturday’s aborted coup was the reaction of the people of Rostov-on-Don, including the city’s military leaders, to the soldiers who arrived and declared themselves to be their new rulers.

The Wagner mercenaries showed up in the city early Saturday morning. They met no resistance. Nobody shot at them. One photograph, published by The New York Times, shows them walking at a leisurely pace across a street, one of their tanks in the background, holding yellow coffee cups.

Yevgeny Prigozhin, Wagner’s violent ex-con leader, posted videos of himself chatting with the local commanders in the courtyard of the headquarters of Russia’s Southern Military District. Nobody seemed to mind his being there.

Outside, street sweepers continued their work. Early in the morning, a few people came to gawk, but not many. After Russian President Vladimir Putin gave a panicked speech on television, comparing the situation to 1917 and evoking the ghost of civil war, one man pushing a bicycle was filmed berating the Wagnerites and telling them to go home. The troops laughed him off. But later in the day, more people showed up, and the atmosphere grew warmer.

People shook their hands, brought them food, took selfies. “People are bringing pirozhki, apples, chips. Everything there in the store has been bought to give to the soldiers,” one woman said on camera. In the evening, after Prigozhin had decided to stand down and go home (wherever home turns out to be), he drove away in an SUV with crowds filming him on their cellphones and cheering him on, as if he were a celebrity leaving a movie premiere or a gallery opening. Some chanted “Wagner! Wagner!” as the troops emerged into the street. This was the most remarkable aspect of the whole day: Nobody seemed to mind, particularly, that a brutal new warlord had arrived to replace the existing regime—not the security services, not the army, and not the general public. On the contrary, many seemed sorry to see him go.

The response is hard to understand without reckoning with the power of apathy, a much undervalued political tool. Democratic politicians spend a lot of time thinking about how to engage people and persuade them to vote. But a certain kind of autocrat, of whom Putin is the outstanding example, seeks to convince people of the opposite: not to participate, not to care, and not to follow politics at all. The propaganda used in Putin’s Russia has been designed in part for this purpose. The constant provision of absurd, conflicting explanations and ridiculous lies—the famous “firehose of falsehoods”— encourages many people to believe that there is no truth at all. The result is widespread cynicism. If you don’t know what’s true, after all, then there isn’t anything you can do about it. Protest is pointless. Engagement is useless.

But the side effect of apathy was on display yesterday as well. For if no one cares about anything, that means they don’t care about their supreme leader, his ideology, or his war. Russians haven’t flocked to sign up to fight in Ukraine. They haven’t rallied around the troops in Ukraine or held emotive ceremonies marking either their successes or their deaths. Of course they haven’t organized to oppose the war, but they haven’t organized to support it either.

Because they are afraid, or because they don’t know of any alternative, or because they think it’s what they are supposed to say, they tell pollsters that they support Putin. And yet, nobody tried to stop the Wagner group in Rostov-on-Don, and hardly anybody blocked the Wagner convoy on its way to Moscow. The security services melted away, made no move and no comment. The military dug some trenches around Moscow and sent some helicopters; somebody appears to have sent bulldozers to dig up the highways, but that was all we could see. Who will respond if a more serious challenge to Putin ever emerges? Certainly the military will think twice: Perhaps a dozen Russian servicemen, mostly pilots, died at the hands of the Wagner mutineers, more than died during the failed coup of 1991. Nobody seems particularly bothered about them.

One day after this aborted coup, it is too early to speculate about Prigozhin’s true motives, about what he was really given in exchange for standing down, about where Putin really spent the day on Saturday—some say St. Petersburg, some say a dacha in Novgorod—or about anything else, really. But the flimsiness of this regime’s ideology and the softness of its support have been suddenly laid bare. Expect more repression as Putin tries to stay in charge, more chaos, or both.

#current events#politics#russian politics#psychology#sociology#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#russia#yevgeny prigozhin#vladimir putin#wagner group

162 notes

·

View notes