#pierre aronnax

Text

obsessed with this specific subset of classic novels

#honorable mention: bilbo baggins#litblr#memes#dracula#dracula daily#20000 leagues under the sea#the great gatsby#jonathan harker#pierre aronnax#nick carraway

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

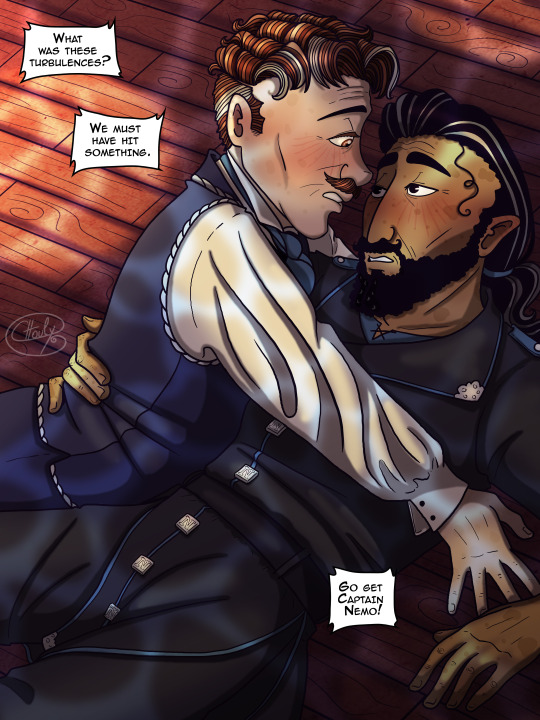

Had to draw this little meet-cute

#voyage of the nautilus#20000 leagues under the sea#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#pierre aronnax#captain nemo#ned land#conseil#fish art#jules verne

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I say I want to meet my future spouse the "old fashioned way" what I mean is: I wish to be in a shipwreck caused by the creature (presumably some unnaturally large narwal) I have been searching for, only to discover that it is in fact the most incredible submarine(!!) and then get saved from the icy waters by it enigmatic captain with whom I fall desperately in love despite knowing it can never be for I am their captive in all but name.

#i have normal desires#is this meet cute too much to ask for?#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#20000 leagues under the sea#tkluts#20kluts#20k leagues#20k leagues under the sea#aronnemo#pierre aronnax#nemonax#nemonnax#captain nemo#aronnax/nemo

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

just a few memes I created, heheh, I hope you find them funny :))

#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#pierre aronnax#captain nemo#20000 leagues under the sea#jules verne#classic literature#french literature#classic lit#ned land#conseil#memes#twenty thousand leagues under the sea memes#tkluts

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

They are soooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo. And I mean it.

#2kluts#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#20 000 leagues under the sea#Captain Nemo#pierre aronnax#nemo/aronnax#cant believe Jules Verne just wrote the library scene from beauty and the beast like seven times in a row.#they're in love#and it's making Ned sick#bananart

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got an illustrated version of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea!

(If you hear mysterious pterodactyl noises, do not be alarmed.)

Some thoughts:

They did Aronnax quite nicely!

Nemo looks pretty good, but more Russian than Indian

Ned is very pretty and has, for some reason, a hoop earring, and is almost never seen with his striped shirt

Conseil looks absolutely nothing like Conseil

The scenery and fish illustrations are top-notch

Does anyone want to see?

#tkluts#20000 leagues under the sea#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#jules verne#captain nemo#pierre aronnax#conseil#ned land#FISHIES

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dead Men and the Sea

In which our good friend Jonathan Harker finds himself aboard the Nautilus and Captain Nemo finds himself dealing with a passenger far less amenable to his mandatory hospitality.*

A sizable ‘what-if?’ scenario based loosely on the premise of The League of Extraordinary Gentlefolk comic-in-progress, a glorious public domain mega crossover and antidote to Alan Moore’s unpleasant take on the idea. Shout out to @mayhemchicken-artblog for all the amazing work that’s already gone into putting this giant thing together.

(Warning: Contains spoilers for the end of Dracula and Twenty-Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.)

((*This is a big one. Grab a snack, get a drink, don’t make any plans.))

Captain Nemo was a man shocked by very little. Life had inflicted too much in its wonders and horrors for anything more rousing than surprise to enter his heart. There was no dearth of awe, renewed afresh with every waking witness to the sea’s bounty. Nor was there ever a shortage of loathing, likewise revived with the crossing of those villains that dry land so readily supplied; that miserable few who stained life upon the continents so that all the land was sullied with their gluttony and bile.

But here? Here, there was freedom. Always there were miracles that swam and grew and kept the soul alive.

All this, and what had been his mission. A task at once as artic-cold and roiling hot as the vents at the ocean floor in its design. All this had owned the scope of his interest. But no shock. Not until the Englishman came.

That he was English was the first strike against him, naturally.

That he had been brought down into the Nautilus after slaughtering a man atop the vessel, such that he had sent a severed head tumbling down into the open hatch, was the second.

That he had needed to be netted and tackled by a horde of the Captain’s crew, capped by an ultimate unpleasant use of electrocution, lest he succeed in tossing the initial few into the water like ragdolls, was a third; if an impressive third. It had taken a veritable swarm to turn the struggle. Even then, the shock administered by the pole, which was intended to knock him unconscious outright, had merely left him stunned and slurring. Two men were needed to pry the blade from his hand.

The latter was a quite handsome kukri that now lay on the table before Captain Nemo. Alongside the head.

Its hair might have been blond once upon a time. Now it was white as foam, as if bleached and salted by endless swimming. Yet it was not as white as the Englishman’s wild mop. Nor were the dead eyes more unsettling than the burning gaze his men had described.

It was with some fair amount of relief that his comrades deposited the fellow in the windowless chamber. He had been coming around too quickly for any of their liking. Not a minute after the door was bolted on the cell, it started trembling. A nigh imperceptible tremble, for the Nautilus was as hardy within as without. But still. The door had resonated just enough to hint to its witnesses that the man within was knocking hard enough to make it ring like an angry bell on his side.

This, when the Englishman was apparently a whipcord in his build. A whipcord who had juggled men twice his size with the ease of a killer whale sporting with a seal.

Interesting, interesting. Bordering on shocking.

But the Englishman’s spectacle was outweighed by the head.

That awful, impossible head.

The somewhat greenish crewman, Ridder by name, who had seen the Englishman’s kukri slice the head free and therefore had the ghastly luck of catching the wretched prize, was sitting across from him. Captain Nemo was not so prideful to pretend he did not feel every bit of the gawping awe and disgust at what was on the table. Though if the crewman spoke the truth���likewise for those few pallid witnesses who admitted to seeing the same phenomenon—then the head was even worse a thing than it already appeared. Impossible or no. The impossibility being this:

The head belonged to a corpse far too old to have come from a living combatant. Here was flesh turned to sponge. A sagging, stinking, bloated grey mess clinging to the skull. Small crabs had been picked loose from the sea-bleached locks. Barnacles had crusted behind both ears. One of the crewmen had gagged when the eyelids were pulled back, only to reveal there was but one eye. The other socket had birthed a sea slug. And yet, according to Ridder and his company, it was only the second most astounding reality of the head.

Poor Ridder, who had delivered the head red-handed, the blood of the kill painting his shaking fingers, who was still fitfully scrubbing at his washed palms, swore to his captain and to his God as if they shared the same body:

“It was not like that when I caught it, Captain. The little creatures upon him, those may have been there, for they were small enough details to lose in the moment. But I will swear on my life, on yours, on my family still cased in their land-girt graves. The head was alive when I caught it. Not merely ruddy, though it was that too. The head moved. It snapped its teeth at me! It even…”

“What, my friend?”

“It bit me. Bit me with sharp teeth that are now as vanished as its hale appearance. It had teeth like one of the anglers, set where our canines should be. But between one moment and the next, the head stopped its biting and bleeding and became…” He gestured cautiously at the doughy horror of the head. “Even my bite, such as it was, is gone. It was only a scratch, and I would not have known it nipped me but for my spying it. But it was there, on my wrist, and now it is gone.”

“I see,” Captain Nemo nodded. “And the body?”

“There were some opportunists in the sea,” one of the others murmured. “We could not see what took it for the flurry of the water, but once the corpse fell off to the side, it did not resurface. Nor was there any sign of it when we examined the Nautilus’ sides. Whatever snatched it was hungry and quick. The Englishman…” He bit down his words. Captain Nemo regarded him with the full weight of his eyes.

“Yes?”

“When we were bringing him down, after the shock from the pole, he kept trying to speak. I think he was saying, ‘Is this your home? Is this your home? Make no invitations. Welcome none.’ I cannot be sure.”

Captain Nemo nodded.

“Shall we draw lots to see who dares to follow me to his room?”

There were no lots, but many volunteers. Once again, there was no surprise, but a great warmth at the gesture. A feeling dented somewhat by their unpleasant cargo. They found a suitable pail for the purpose. One with a lid.

The Englishman was pressed up against the furthest wall of the chamber when they arrived. He’d taken one of the chairs along with him. A clear counter-deterrent should the electric pole make a return. Which it had, for one of the stouter men kept it at the ready. But not at the front of their entourage. That spot belonged to the Captain and his diminished guest.

Having a clear view of the Englishman confirmed some of the men’s description, if not all of it. Yes, here was the snowy hair, the trim build, and even some small unsettling glimmer to the eyes. But the last was easily attributed to his current status. Still sodden, bereft of his weapon, he looked precisely like the skittish and bewildered captive he ought to have been. Nostalgia almost fooled the Captain into seeing a hint of Aronnax in his mien. Something of a man who belonged in a library or sat behind a busy desk.

And yet the kukri was still drowsing back in his stateroom and there was a head in a pail that quite soured the image of a frightened scholar. To say nothing of the assorted bruises and bandaged cuts seven men now wore with this young man’s signature on them. Was he young?

Much of him seemed so, but for those eyes. An eternity seemed stamped in their gaze. He recognized it from his own mirror.

“Hello,” the Englishman tried. He had the timbre of a youth, at least. “My apologies for the misunderstanding up top. I can only guess what you may be thinking.”

“Guess no more. What I think is that you have much to explain. Starting with this.” Captain Nemo deposited the hideous head upon the table. It made a horrid squelch as it landed. The Englishman regarded it coolly. “My men tell me it looked a fair bit different before you relieved the previous owner of it.”

“Indeed. He appeared quite healthy. They always do after they’ve drunk. Some will go red as ticks if they take enough.” Saying so, his eyes snapped suddenly to Ridder. The crewman stiffened in his position behind the Captain’s shoulder. “Your bite. Did it vanish?” Ridder looked away, hands freezing mid-fidget.

“It did,” Captain Nemo answered. “I’m told it disappeared in the same instant this,” he pointed to the head, “ceased to be a rosy horror of champing fangs, and became the ghastly lump it is now.” At this, the Englishman appeared to relax an inch. “None of which appears to surprise you.”

“That?” He nodded to the head. “No. This?” He drummed his knuckles against the wall. “Somewhat. I had not realized such technological leaps were in play today. I have friends who would swoon to even conceive of it.” The Englishman shrugged. “But reckoning with the reality of one impossibility makes all other oddities following it easier to accept. I can tell you have somewhat reconciled with that uncanny souvenir’s nature already.”

“Somewhat,” Captain Nemo echoed. Perhaps a little sharply. “Who is it I address?”

“Jonathan Harker, sir. Might you be the captain of this vessel?”

“Captain Nemo,” he allowed. He did so sitting at the table. “Stand or sit as you please, Mr. Harker. My men are present only as insurance that you will not give them a second dose of what they claim was a more than decent fight.” A cloud seemed to pass over Harker’s face at that.

“I’m certain there are muscles in my back still twitching from electrocution that would be happy to debate them.”

“I said more than decent, Mr. Harker. Not more than fair. They came upon you and a combatant tromping around on our roof, you the only one armed. You proceeded to decapitate the other man—,” he held up his hand before Harker could interject, “—or what passed as a man. Understandably, we were disturbed. Our group rushed to the scene. We reacted to you, you reacted to us, and Ridder and his company reacted to the head. Between this confusion of violence and the uncanny, of course we gathered you down here for answers.

“My fellows were met with a surprise in you as, just as unbelievably as your opponent revealed his bizarre nature, you revealed yours. There is too much proof in my men’s injury to doubt their story; one of a mad Englishman swatting some of our strongest fellows down like children and slaughtering man-shaped monsters over our heads. But for caution, numbers, and quickness on their end, I don’t doubt they could have lost some dear pieces in the scuffle.

“Had you not been so smothered and shocked, we could never have gotten you below, and so would not have been able to submerge. Not without leaving you to drown in the cold. Brutish as the manner was, we collected you as we did for safety’s sake. A safety I suspect is now doubly endangered. If not by mortal man,” he glanced again at the reeking head, “then by abominations even worse than him.”

Harker stepped forward. Still gripping the chair.

“You suspect rightly. And so I must repeat a question that went unanswered before. Do you all consider this vessel your home? If so, there is hope. For these things cannot cross the threshold, or hatch, or window, or any other entry, if it is a domicile they are denied invitation to. Give them that welcome even once and the way is open to them forever. I cannot picture a more promising banquet to such demons than this marvel we stand in. There is nowhere to run down here.”

“The Nautilus is our home, Mr. Harker. No man here would deny it. Nor are such fiends as the kind you describe welcome to ruin it. Yet it would help a great deal if we knew what enemy it is you speak of.”

“By the look of your crew, I’d wager a good portion already suspect the truth.” This Harker said from the opposite end of the table, finally sitting. His gaze leapt cautiously between Captain Nemo and his company. “It is a vampire, Captain. One of an entire ship’s crew that was preyed upon by a far older monster and thrown to the sea last year. The Demeter’s sailors.” Again, that strange burning came into his eyes. “And they have been quite busy.”

Jonathan Harker spoke of the Demeter and its unthinkable passenger. Of the dead men who were tossed in the depths and left unable to die. Only to thirst, there in the dark, using the sand as their resting place, the passing ships as their cattle. New ghost stories had cropped up where they fed; tales of passengers and sailors vanishing overnight. A ship is not a home to most, after all. No invitation required. Likewise for the shores of port towns. Their docks, taverns, inns. All were easy targets.

The one kindness, he said, was that the Demeter’s men were not callous enough to consign any others to their unique hell.

“They died at sea and their grave dirt is the sand of the ocean floor. It is where they must always rest. Even a beach is not refuge enough. So they are careful enough to murder their victims outright when at sea. Those on land have been less fortunate. My companions and I have curbed three ports’ outbreaks thus far, but we cannot keep such a pace indefinitely. So we turned to maritime hunting, the better to cull the source. A far more troublesome setting than the Carpathians where we undid their maker. The ocean is too vast a hiding place.”

“Just vast enough,” the Captain countered. “If you speak the truth, I can see the danger. How many of these vampires of the Demeter do you estimate are left?”

“Under a dozen. But even one can mean death and worse for a legion. You and your lot especially would be a boon to their kind, Captain.”

“For the sake of the Nautilus.”

“Yes. With you and yours as part of their colony, that would make them your masters. Even against your will, you would grant them this vessel as their own territory. It would make for a more than enviable change of real estate.”

“So it would. But the Nautilus is as barred from undead thieves as living ones, Mr. Harker. On this, I swear my life.”

“I am glad to hear it. I’ll be gladder still not to burden your Nautilus with my unwelcome company. No, you do not have to pretend otherwise. For all the effort put into wrangling me, I was not brought aboard with any real desire for a collected stray. I can give you the coordinates to the port my friends would most likely meet me at. It would behoove all of us to exchange information and aid. I’ve no doubt that you will encounter more of the Demeter’s men in the near future. Perhaps even en route to shore…” He trailed off as Captain Nemo sighed.

“Mr. Harker, I’m afraid that will not be possible.”

“What won’t?”

“The shore. Land. There’s no such destination ahead of us here.”

“I don’t follow. Why can we not approach land?”

“The short answer, is that land and all the monsters God allows, be they men or not, dwell there. I and my crew have quit ourselves of them for good. Such is the gift and price of our freedom in the ocean. The nature of our lives down here is a treasured secret—,”

“Which I would keep, whether it was your concern or not.” Fatigue flickered at the borders of Harker’s face. A certain echo of bitterness been and gone. “Do you think me and mine have dared to run our mouths about these bogeymen in an era of modern sense and science when there was no witness to corroborate? We’d all be sharing the same sanitorium if we tried. We are all of us practiced in the keeping of outlandish confidences, Captain. If you’ll forgive me, the nature of this whole place seems like the sort of thing only possible in fairy tales and adventure books. No one would believe it even if I ran babbling to the newspapers.”

At this, Captain Nemo could not withhold a smile. It was a mirthless one, a thing of memory, but it went unstopped.

“Ah, but I have made the newspapers already, Mr. Harker. In a sense. Though I was a mere sea monster then. Who knows if they have guessed a little closer in the meantime? I cannot say, for I have not touched fresh newsprint in years. But all that is besides the point. The point being this.” The Captain bowed forward until he had to rest his elbows on the table, his eyes like obsidian chips. “As much secrecy as can be maintained, will be maintained. Enforced, rather. In curtest terms, Mr. Harker, we cannot risk you breathing a word of our existence to others. Not even trusted fellow vampire hunters. Not even wife or companions.”

Harker stared at him.

Though he tensed, there was no quaver as he said, “If that’s the case, this has been the most confusing leadup to a murder I’ve had to sit through, Captain, and I have endured some odd ones.”

“If we wished you dead, you would already have drowned. Or else been left to become a shared drink by your devils of the Demeter. No, we have no intention of killing you. But I’m afraid you too must accustom yourself to calling the Nautilus home. Permanently.”

A strange thing happened then. Captain Nemo would think on it later as something very near to an optical effect as he had seen with those octopi who shudder into new hues and textures as a matter of disguise. In the case of Jonathan Harker, he could not say whether he was pulling a guise on or shrugging it off. Whichever it was, the Jonathan Harker across the table abruptly became the Jonathan Harker the men had met atop the Nautilus. The Captain watched the change happen; he dared to say he even felt it. A tangible shift in Harker’s presence that went from the air of a man to the chthonic weight of a Thing that was, if not a vampire, then a sure cousin.

Harker did not move. Harker did not blink. Harker barely seemed to breathe. For a moment, then two, then three, he only regarded the Captain with the same alien consideration used by those most vicious carnivores of the depths as they pondered the merits of rending potential prey to so much gristle. Habit tried to make the Captain paint this as the mere duplicity to be expected of an Englishman; cordial only until they found they would not have their way, and then all was bloodlust and destruction.

But no. That was not it.

Jonathan Harker was not irate, not aghast. Not shocked. That much had clearly been blasted from him as cleanly as it had been in the Nautilus’ crew. No. Captain Nemo found he was being pierced with the glare of a man who recognizes an old enemy.

“Captain. Am I to understand that there is no convincing you otherwise in your course? Even if I were to ask that you surface and leave me to an island? Spit me up beside a ship?”

“There is no chance of it, Mr. Harker.”

“And it is not a matter of insurance against the vampires? There is still a chance you could use that as a way to convince me. I might even believe you.” A smile of raw bitterness cut its way across the young man’s face. It hung there like a rictus. “I should like to believe that a while before I must accept I’ve found myself in this particular corner of Hell again.”

“To that I take offense. The Nautilus is a sanctuary—,”

“I have been forcibly detained in sanctuaries before, Captain. For my health at first. Had it not been for my wife’s intervention, I’ve no doubt I would have been caged there indefinitely—because I raved the truth at them about the last place I was held prisoner. A place far more dreadful than even that,” he pointed to the head, “poor soul’s unholy remains. A land of nightmare. While I wish for death no more than the average man, that place taught me fears of life unending that I never thought possible. Worse, a life bound eternally to that place. Away from the one I love most in this world. Forever.

“I have no intention of playing that out again, Captain Nemo. For, with due respect to you and yours, I have more concerns in the world than playing tattletale about your hideaway.”

The Captain met his stare and did not break it.

“If that is the case, then I ask that you content yourself with the threat of your vampires as reason enough to cease opening the hatches. Whatever grimmer notions you have in mind, wait until the monsters are slain to give them vent. Until then, I think all would appreciate cordiality over another round of violence. At the very least, I assume you would appreciate better lodgings than this. There is a stateroom at your disposal. Likewise for my library and sundry other corners of the Nautilus you may feel free to explore, with but few exceptions.”

“How gracious a host you are, Captain. But I can save you the time. I’ve heard your speech before.” Under his breath, “All we’re missing is the Weird Sisters and the wolves.” Back to his ordinary pitch, strained through a grin like a sickle, “Before we engage in this mutual game of denial, might I impose on you to borrow pen and paper? My journal is sadly waterlogged and useless for notes. In the event that even this chat is foreplay before you decide to kill me, I should like to leave behind some instructions should the Demeter’s men make their play at breaking in.”

“There is stationery in your room, if you will accompany us.”

“Of course.” The words left him with the same tone as if the Captain had announced he was being led to the gallows. It was a tone that, despite its lack of fire, made him think of Ned Land. Albeit a Ned Land honed down to an unearthly edge by the whetting of an unimaginable history. Perhaps selfishly, the Captain hoped he might dislodge that fuller tale from Harker in time. Mad, maddening, or otherwise. But for now, he was custodian to the Englishman—as unhappy a prospect as a blissful spinster aunt finding herself the caretaker of her sibling’s abandoned offspring—and one with all the manner of a barracuda waiting for a hand to come too near his mouth.

Still, he went to the room placidly. A fact no doubt aided by the combination of his company and the fact that the Captain had slipped loose the panels that hid the depths from the exterior rooms before coming to meet him. Through numerous doors, Harker could see glimpse after glimpse of proof-positive for his lack of options. There was naught but the ocean in all its benighted shadows on all sides. The young man had mentioned wolves; but wolves could be outrun, outmatched. Not so for these submerged leagues. Even if he took it into his head to carve his way through the crew, and even if he succeeded, he would drown or suffocate from lack of understanding how the Nautilus operated.

His only way out, as he would no doubt assume, was by patience, by persuasion, or sheer luck.

An assumption that was faulty to begin with, as it suggested Captain Nemo or his crewmen were susceptible to any of the above.

The only exception being the matter of the Maelstrom. But that was a feat not to be repeated. Aronnax’s face flickered briefly behind his eyes at the recollection. Him, Conseil, even the incorrigible Ned Land. They had made it out, at least. He had seen to it. Despite this, he had thought of charging up onto that rescuing shore to snatch them from their discoverers. To fall upon the professor, at the very least, that blessed-damned new offshoot of his heart, and drag him back into the surf like some dread sea dragon refusing to forsake its treasure.

But there had been more important things to draw his will. The injured, the Nautilus’ immediate repairs, the threat of a gawping coast. No. He had had no choice but to let them go. To hope they would not lay their secret bare to the dry world and have it believed. To hope they were alright.

None of which was the case with the curious Mr. Harker.

Even knowing this, guilt turned over in his throat. He gulped it back down as Harker took in the stateroom. Again, there was that strange, almost accusatory tinge of recognition in how the Englishman looked over the room’s trappings.

I have been here before, said every step and glance. I know this, I know that, I know them. Yes, I have had this nightmare before.

Captain Nemo pointed him toward the desk, its notepaper and the assortment of untouched journals. He sat at once and began to write with his back to them all.

“We are not your,” enemies he almost said. History nettled his tongue against it. “We are not your keepers without reason, Mr. Harker. It is no surprise you find our manner churlish. I expect we must seem like a party of lunatic wardens to your eye. But we have suffered much, all in our own ways, under monsters born of men. If you knew—,”

“Is there garlic aboard?”

“What?”

“Garlic. The bulbs or the blossoms. Do you have any here?”

“None. All of what is onboard is harvested from flora and fauna of the sea. We have quit ourselves of all things hailing from dry land—,”

“What of bread? Bibles? Holy scripture of any faith, really. It covers more possibilities. We ran into one who hated the Star of David, another who fled from an amulet of Thor’s hammer. How are you on spears and stakes?”

Captain Nemo answered the volley for the next few minutes. A quarter of an hour passed in which Harker filled out three sheets of guidelines in proofing the Nautilus against vampiric intrusion. He seemed especially unsettled at the mention of the air vents.

“They can become mist, Captain, and I cannot say whether those apparatuses would count as traditional thresholds. See that you mark them as best you can with sacred icons in the metal. Is anyone onboard a priest? A holy man of any kind?”

“None.”

“Then this is the whole of any preparation that can be done, at least to my knowledge.” He handed the Captain his little stack at arm’s length. “At least beyond praying en masse that some greater creature of the deep comes along and puts them out of all our miseries. As for me, I will busy myself hoping they do not reach my wife and friends and take them unawares. They are all practiced hands, but you never know when a chance mistake will catch a body off-guard. Tackling an undead anathema off a ship to keep it from your companions and lopping its head off on what you mistook for an islet, only to find yourself mobbed, electrocuted, abducted, and imprisoned on the whims of the islet’s inhabitants…these things happen. Strange, but true.”

“Mr. Harker—,”

“I am very tired, Captain. I would like to sleep and see if you all disappear in the interim.” He did not wait for a response, but shucked his still-damp layers down to his underthings. Harker laid them over the desk chair, presumably to dry, then helped himself to the bed. Once covered, he planted his back to the wall and shut his eyes. The Captain could not decide whether he saw more of a child’s sulk or a condemned man’s stolid despair in the act. Either way, that impression of routine stained him.

He has been here before.

“Wake me if they make a move,” Harker told his pillow. “If they are sighted, avoid looking them in the eye. Their gaze paralyzes.”

With that, Captain Nemo and his men felt themselves dismissed. On the other side of the door, shut but not locked, the Captain took four of the group aside.

“Keep watch in shifts. Both for your sake and his.”

“You suspect he is of the Quebecois’ temperament?”

“I suspect he is worse off than that.”

Time proved him right.

In hindsight, the appearance of the vampires would prove as brief as a heartbeat and as endless as a held breath. Too much, too quick, too horrid for comprehension of all that came so near to their throats.

“I commend you for not racing away from the danger outright,” Harker had said in a hollow tone, eyeing the wretched mock-humans scurrying along the glass while the crewmen’s senses curdled as one in revulsion. “You could have abandoned this lot for an ocean on the other side of the world.”

“While I have left the countries above the surface to their own sins, I take great offense at menaces in the water. These are invaders, thieves, slavers and pestilence in one. My oceans shall not suffer their like. Worse, if they own the potential for immortality you suggest, who is to say we would not be surprised by them another night when we are all withered and unaware? No. They must be dealt with now. Though I admit I am surprised at their resilience in the face of our outer defenses.”

Which was to say, the moray’s defense—the electrified field that they had turned up to a lethal voltage. Even without full contact, it was more than enough to fry creatures in the surrounding water. The first jolt had sent the rest of the sea swimming and skittering away in panic. Yet the Demeter’s men merely shuddered back to cognizance. Irate, but no worse for the charge. Undeath fortified them well.

“I take it the Nautilus is not outfitted for such small-scale opponents?”

“It is not.”

“Then the only alternative is meeting them face to face. I have no delusions that last night’s one-on-one bout will not be repeated. They will converge wherever you go, so long as you allow them, be it above or below the surface. If you return the kukri to me, I shall do what I can against as many as I can. As yet, this place is still not my home, but a pretty fishbowl. Even if they turned me, I could not provide the loophole of invitation.”

“Do not leap so quickly to martyrdom, Mr. Harker. There is another option. You suggested as much in your notes.”

“How is that?”

“It is as you say, we must meet them face to face.” The Captain presented a smile no less grim than the Englishman’s. “Though not as combatants.”

Daybreak sent the vampires drifting drowsily away. Down, down, down. Away to their sand to sleep like the dead they should have been. A sleep that was, if Harker spoke true, as implacable as a coma.

It was and he had.

Shelled in their suits, breathing bottled air, armed with blade and harpoon, electric rifle and holy symbols, they marched on the living graveyard. The undead had dug graves for themselves here, lining them with stones and seaweed in sad pantomime of a coffin. Already waterlogged, they barred themselves against buoyancy by pinning themselves under slabs of scavenged driftwood weighted by stone and coral. In sleep, they were a sight of pitiful melancholy. It seemed almost as evil a thing to slay them as it was to let them carry on. Almost.

The work was efficient and endless at once. Viscous blood spurted from chests. Voiceless howls foamed up from the cavernous mouths, spewing bubbles and ichor. Necks split and heads loosed. One after the other after the other. Done.

Harker stood over them longest, even at the brink of his air thinning. He almost needed dragging back to the Nautilus. Once the suit was peeled and the helmet was pried free, Captain Nemo saw the young man’s eyes had aged another lifetime.

“The job is done. So. Is this when the denial ends? Am I a temporary aide or a prisoner for life, Captain?”

“…You are my passenger.”

Harker had looked at him. At the men who still outnumbered him and outweighed his surreal strength so many times over. At his kukri, already confiscated and sheathed. He nodded.

“I thought so.” Harker inhaled. His exhale was a single word, “Mina.” Then, with a flash of steel, a bowie knife appeared from some hidden scabbard in his trousers. The blade leapt for Harker’s throat. Captain Nemo was the first man to tackle him, but not the last. For their efforts they were cursed, beaten, slashed, and cursed again. Between curses, Captain Nemo managed to twist the knife out of the young man’s hand while someone else got a syringe into him—it sunk neatly into the very place the knife had wished to carve open. Jonathan Harker slept.

He was taken to bed bound.

Captain Nemo went to bed sick.

More time. More time. More time.

In the course of it, Captain Nemo looked back again on his period with Aronnax and his companions. Good Pierre, thrilled Pierre, so ready to trust, to allow for all the little edges of monstrosity his captor had cultivated, repainting them merely as passions, as eccentricities to filigree some hero of invention and intellect, and most preposterously, a good man. Him. A good man.

Yes, he had been that for a time. Before, in his tempest fury of the Nautilus’ mission, he had trampled that vision before the scientist’s eyes. Both their hearts with it. Yet there had been some grace before and after that. Pockets and sprawls of joy at the ocean’s wild glory.

Pure luck. A lottery won in terms of castaways. If only for how it burnished the Captain’s view of himself in the mirror to a high, flattering shine. He had not been oblivious to it then. But he had not needed to dwell on it. Unlike now.

Now, when Jonathan Harker proved day by day, week by week, month by month, to be a far bleaker looking glass. In his tears, in his silences, in his ever-lengthening stints without seeing to the mere mechanics of eating. Even those few occasions where he was given leave to come up to open air, to walk the Nautilus’ hull or set his feet on the sand of some remote island, he was never fooled into mistaking these allowances for more than what they were.

Never a way out. Never a chance at signaling civilization, let alone reaching it under his own power.

“My thanks for the walk,” he once croaked upon return from the sand. “I’m doubly grateful you’ve not seen fit to weave a lead and collar out of seaweed as extra insurance. Perhaps you should have a bowl of kibble to shake next to the hatch. I shall surely come running then.”

The Nautilus’ best fare seemed as good as kibble in the Englishman’s estimate for all he swallowed of it. Such that his already haggard countenance, now made worse by the denial of a shaving razor for some time, was bordering on malnutrition. His cheeks were shelves behind his stubble—

“A blade and no mirror. Now a mirror and no blade. Ha.”

—his eyes bloodshot coals in their sockets. It was not until the day Captain Nemo was alerted that Harker appeared to be missing that the full brunt of the young man’s state was laid bare.

They had not been to shore. Harker had not made his habitual visit topside when the Nautilus rose to refill its gasp of sea air. So far as anyone had known, he had gone straight back to his room. But when a pair of men had gone to attempt goading him into swallowing a third of a dinner, the young man was gone. A brisk hunt was made of the cabins, of the library, of every corridor and corner. Nowhere.

At least, nowhere plausible.

It was a second search of the library that bore fruit. A fruit shaped like a journal. The Captain spotted it on the floor near the bookshelves, fallen open at the midpoint. Lines of a half-familiar cipher filled half the pages. A form of English shorthand.

“That was not here when we last checked,” he heard behind him.

“It was. He just hadn’t let go yet.” So saying, Captain Nemo guided their party’s gaze up to the top of the bookcase. There, a small niche existed between ceiling and the black rosewood. From this crevice dangled a single limp hand. “Mr. Harker.” No answer. “Harker!” No answer still. “…Jonathan?” Not even a twitch of the fingers. “The ladder,” he felt himself murmur. Possibly. His senses had closed down on a sudden nauseous cold twisting in his bowels.

“What—?”

“Get the ladder.”

For the rolling ladder that most would use to scale the shelves to their full height was nowhere near that hand, but at the case’s furthest end. Before any man could act, the Captain had snatched the ladder, rushed it to the spot, and was up like a shot before anyone else could touch the rungs. Atop the bookcase, he found Jonathan Harker folded into the gap between wood and copper.

Dead.

“No.”

He was.

“No.”

He hauled Harker out of his cramped position in the shadows and into the electric light. This brought even less assurance. There was a sunken quality to the already-greyed pallor. Under the young man’s shirt was a belt cinched tight around his concave middle. Cracked lips fell open on a dry mouth.

But that mouth breathed. Thinly, thinly. But it did.

Not dead.

Yet.

“Help me with him,” he called down. “One of you, tell the kitchen to make up something thin. He’s been starving himself.”

Bed, broth, and book ensued.

The former two to Harker. The book the Captain turned over in his hands. There were guides he might consult to decipher the shorthand in full. Temptation nagged at him over it and the entries preceding the last of the pages. Yet he did not find himself so low a hypocrite as to deny Harker his privacy when his own secrets remained buried.

Still, he had enough rough memory to serve him for the final entry in the volume. It was the page it had been open to when he first scooped it up.

‘Not again. I will not do this again. How tidy God is. How cyclic. I live my life in these same ruts of death and worse than death.

‘The Captain thinks I cannot tell his disdain. It lives under his pity, but it is there. As I once snapped out at the whole of a people by dint of the Count’s choice in lackeys, our homeland and its glutted Empire clearly stamps me as a dog in his eyes. Do I have room to blame him for his bile when I spewed the same over idiot assumptions of old? Can I, when whatever he inflicts or has inflicted, I might have earned my own seat in Judgement for my role as a pawn? As a man willing to become a monster when God’s avenues all turned her innocent life toward Hell?

‘I do not, I cannot. Yet they mean to kill me slowly here. I am to live to death among their waves and fancies and furies and bitter mercies. I will become an old man buried alone in their seabed cemetery. No. That I cannot allow either. Yet all the weapons are robbed from me. A knotted sheet might do it quick or it might fumble me. And who knows? As with the wolves and the Brides, there might yet be hope. Given time. I cannot see it yet. I may never see it, though I desire a last gasp in which to try.

‘They mean to kill me slowly. I will die slowly. Though not as an old man.

‘Mina, Mina, it seems I have been stolen from you at last. The castle could not keep me away, nor the sanitorium’s soft and healing cage. But this magic whale has swallowed me whole and swam me away and I cannot escape its belly. Do I pray to God or Poseidon to let it put me ashore when it’s over? I do not know.

‘I love you.

‘Mina, Mina, Mina, Mina, M

There it ended. The ink sputtered and scratched the page where he had lost consciousness.

Captain Nemo closed the book and looked down at the drawn shape under its covers. But for his breath, he might have been a corpse. They had studied his teeth, of course. No fangs. His eyes were only red where they should be white. Yet there he lay, a cadaver, wan and cool. And breathing.

“Shall we pretend you are still asleep? Or might we talk?”

“…There’s nothing worth saying.” The eyes cracked open. Though they rolled to face Captain Nemo, there was nothing in them that suggested they were looking at rather than through him. “I think I can hear him laughing down in Hell. Where vampirism missed the mark, you and your fellows have taken up the cause. You will not let me live. You will not let me die. You will not let me leave as a man or a corpse.”

“Who is laughing, Harker?”

“It does not matter to you. What’s the point in saying?”

“If it does not matter, what’s the point in secrets? I will even trade. My story for yours. We leave it to each other to decide if they are lies. That is one of the freedoms I have come to appreciate of late. One I wish quite bitterly,” Aronnax’s shock-slack face flashed again, eyes huge with understanding, with horror, with the shrapnel of disappointment, “quite bitterly, that I had exercised before. There is no one to impress, no reason to hide what we are and what we have been. Judge and jury exists only within these walls. Often only within our skulls. In short, if you believe all is lost—what do you have to lose?”

Harker looked through him another moment. If his gaze burned at all, it was a mere pair of embers. They slid away from Captain Nemo and turned up to the ceiling. As if they might see through all the way to the sky. The Captain thought he might be left in another drought of conversation, but—

“Do you still have those cigars?”

“Those and an admirable liquor cabinet.” For one so constantly in a state of bereavement, Harker had surprised him by indulging more frugally than a monk in the sensory vices on hand. Scraps and water were the sum of his chosen diet. To judge by the added notches to the cinched belt, he had been taking even less than that. All this considered, “You can sample both so long as I see you eat something heavier than soup first.”

“I’m not hungry.” At the same moment, his stomach let out a traitorous growl. He made a pained face. “You took the belt.”

“I took the belt. Eat.”

Harker nibbled. And spoke.

And spoke.

And spoke.

He had not even escaped Transylvania before Captain Nemo lit their cigars. His first drink came after the night of October 3rd, the hour of his greatest grief and rage, of his wife’s greatest injustice and horror, the hour some integral human self died to birth the living reaper that followed. His second drink came after the kukri blade’s sweep and slice through the bloodthirsty voivode’s throat. His third drink was a toast to the people who had come together for their common cause. To others they had met since; comrades in oddity, siblings in the supernatural. And, weakly, to whatever Powers That Be who had taken his private vow to heart and spared himself and his dear Mina so grim a payoff for their pains.

His cheeks had collected wet streaks more than once. Rolling and vanishing into the wilderness of stubble.

“Well?”

“Well,” Captain Nemo echoed, emptying his crystal. “Now I owe you mine.”

Captain Nemo spoke.

And spoke.

And spoke.

Of kingdoms and conquerors, of colonists and killings. A life stolen from him by dint of so many lives around it being destroyed. He spoke of a Prince who fought the British chokehold and lost all that mattered for his efforts. That man had died in soul with his family to create a Captain. The man steering a sea monster who preyed upon the Empire that had razed his world and others’. That Empire being one evil among innumerable devils that men made of themselves over gold, power, and petty whims. The paradise that the world could have been was left a flaming cesspit by these tyrants’ design. He would neither join nor suffer them. The only escape apart from the grave was the sea and the refuge of the Nautilus, cradled in depths unspoiled by men.

His face did not escape its own damp tracks by the end.

“What a poor pair we make,” Harker murmured after a time. “Two dead men mourning themselves.” On the heels of that, “I am sorry for all you’ve lost.”

“And I you.” Harker shook his head at him.

“My world still exists. Whatever else you intend for me here, I can dream that they are all still alright up there. Your world was devoured outright.”

“True. But there are more things to lose than things you can touch. They are no less precious for it. For my part,” a storm threatened at the back of his throat, roiled under his tongue, “I wish you had been able to skin your Dracula rather than release him with a mere stab and cut. It was far too kind an ending for such a villain.”

“Agreed. Yet it was all we could do.” Harker sighed at his empty glass but would not take another refill. “What happens now? I can’t imagine you and your lot devoting your full time to playing nanny as a guarantee I’m not endangering myself or others. It would be a hard time getting anyone to draw straws.”

“You are half right. Truth be told, there are precious few of them who have forgotten your introduction. Even your choice of hiding place speaks to a less than heartening choice of ward, even among brave men.”

“How do you mean?”

“Harker, you are two-thirds dead. Even so, you scaled a bookcase without disturbing a single volume and perched yourself in a spot that the best assassins would struggle with. I would have assumed you’d used the ladder, but you could not have reached it to shove it away in that position. What?”

The ghost of a healthy pallor came and went in the young man’s cheeks.

“I admit I was…somewhat hazy when I reached the library. I was looking for a place I couldn’t be looked in on. The ladder didn’t even occur to me. So, the shelves.” His shoulders twitched in a shrug. “A far easier climb than castles and cliff faces.”

“As I’m certain a horde of mere mortal opponents is an easier obstacle than hoisting a full box of earth with a grown man inside as though it were a crate of fruit. A feat managed after your pilgrimage up the river and across the snow. Whatever you are, Jonathan Harker, it is a far more extraordinary thing than the victim made of you at the start of your journey. You shall not be a victim now. Least of all to yourself in such a dismal way. Certainly not so soon.”

“I don’t follow.”

“You will. So I hope.” The Captain bowed until his elbows rested on his knees, his jaw on woven fingers. “You are a man who locks hard upon his oaths, Jonathan Harker. You do not shy from a promise made to yourself or another, and so you are meticulous with them. I do not doubt that you are truly decided upon not living out a long life, or unlife, on anyone’s terms but your own. You gambled yourself on the cliff and the wolves rather than stay as a plaything of that vampiric sorority. You would take Hell and its eternity with your wife or die trying to shield her rather than dare raise a hand to her in any shape. And here, in what you doubtless see as an asylum run by the madmen, you decided to whittle your life down by starving increments, the better to test hope and, if hope did not pay off, see yourself out of my hospitality.

“To that end, I would make a request of you. You say you endured two months imprisoned with the Count. The sum of your time from your first visit to Transylvania to your last was half a year. Already you have put up with two months in the Nautilus. I ask now that you be my passenger for the space of the next four months as well. If at the end of this period, you find yourself unable to stomach a life among us indefinitely, you have my own oath that you shall not be hindered should you wish to…exit.”

Harker mulled this a short time. It was as the Captain put it:

“There is nothing to lose.”

“And everything to gain. You have neglected yourself, mind and body, when you were once a walking inferno. Purpose has gone out of you like a candle and left you to molder in your own discontent. You must not ruin yourself before the deadline arrives. Make yourself well again. Do not cast your eyes down at every offering to the imagination.”

“Supposing I did as you say, might I ask you for something in turn?”

“What is that?”

“I want to shave this off.” Harker ground his knuckles unhappily against the thick growth on his cheek. “Keep watch if you must, but I quite hate this. I will even settle for hot wax if you do not trust me with a razor.”

Captain Nemo grazed his own cheek, thinking.

“We can avoid the wax. As to the razor, if only for the fact of your health—or lack thereof—might I meet you halfway?”

“How’s that?”

Some minutes, some lather, and more than a few wary onlookers later found Captain Nemo playing barber. Another phantom flitted behind his eyes as he did so. The shade of a small boy, smearing his own cheeks with foam, holding still as his father ‘shaved’ him smooth with the brush of his thumb. A flicker that was there and gone, brief and wretched as a needle to the heart. But he held steady along Harker’s jaw.

“For a young man,” he hummed, “your beard grows like men twice your age wish theirs could.”

“They can keep it,” Harker got out carefully as the razor cleared another streak. “Even if it were not for how the idea of a beard was soured for me in the castle, I would still shun stubble. I need no more help in looking a decade older than my age.”

“It is a curious thing. You look like a boy fresh from his classes in some moments. In others you look, if not old, ageless. As if you had seen a century and the most time could do was pale your hair and put shadows in your eyes. There.”

He handed Harker the glass to inspect himself. Clean-shaven, he really did lose a decade. Relief also lifted some gloom from his eyes.

“Gray would laugh at me. I do take more solace in my reflection than he does.”

“A reflection and no change in your teeth.”

“So you did check? Good.” He set the glass aside. “Though it is absurd after all this time to still fear such a belated change. Dracula is gone and, should I die, I would not return as one of his creatures. Yet I remain at a loss as to whose creature I am instead. I don’t suppose there are any nautical myths to do with my condition?”

“None but the lore of natural beasts mistaken for monsters. Some truer to their malicious tall tales than others. If it counts for anything, supposing you have graduated to something other than humanity, you are still no monster for all that.”

“No?”

“No. A monster, especially one prepared for self-destruction, would have tried to turn upon us with killing intent long before preying on himself. A last bloody lashing out for its own sake. If you are no longer a man, you are no such fiend either.”

A wan smile clawed its way into the young man’s face.

“I like to hope so. Too many strangers have been made friends since Dracula’s destruction and they have dissolved all the footing I once had in such estimates. Your demons of the Empire are part of a far broader cloth of evil men in the world, few with any touch of the supernatural to them. By the same token, I have encountered living horrors and marvels whose humanity puts saints to shame. Still more have baffled me to the point that their absurdity lives wholly apart from the spectrum of good and evil and falls purely into the alien.

“Surreal as they are, I have grown glad to know them. A pity—,” I will not see them again seemed to hover almost visibly on his tongue, so clear the Captain swore he could read the words. Harker swallowed. “A pity you shall not meet them. Many would squeal at all you have accomplished with your Nautilus.” He made a small noise that was nearly a laugh. “Poor Jack would faint on his phonograph. But just as many of my fellows would shock you in turn.”

Captain Nemo shook his head.

“Few things shock me in this world, Harker, above or below the sea. I have seen too much. You and your vampires are the sole exceptions. I cannot be convinced otherwise.”

The Captain pretended disinterest as he said so, his gaze drifting off. It was a paltry lure, really. Barely baited. Still, the opening was taken for what it was. Harker was looking at him. Whatever burned there burned low—but with something keener than hate or misery. It was that particular gleam owned by those who know they possess a wealth of knowledge that the other side of a conversation is not prepared for. Captain Nemo knew it from his own mirror.

“You say you have seen too much to be shocked,” Harker echoed. “Would the unseen serve instead? Because one of my more recent acquaintances is a man who is wholly invisible.”

“…I cannot tell if you’re joking.”

Harker grinned.

With time, Harker managed the expression more often. This he often did while dropping fantastical hints at the characters he had found himself in league with on land.

Lords and scholars and doctors, oh my. Geniuses and those who outsmarted them. Scientists who made experiments of themselves to outlandishly transformative results. A handsome young rake made forever young as the toll of his life’s years and vices poured into a double on canvas. A nascent psychic; that was, the adored Mina Harker. Among others. Often with extraordinary adversaries to match. Apparently, there was at least one villain among this group’s foes that was a book.

“A book?”

“A book of a play.”

“Ah.”

“The first act is benign enough. That is the bait of it.”

“Of course.”

“Results vary between afflictions of irreversible insanity, death, and/or translocation from Earth to a distant dimension of an unthinkable cosmos, wherein the King in Yellow reigns over dim Carcosa and its subjects for all time. We also think it has ties to a certain type of Yellow wallpaper. It offers likewise unpleasant results for its victims, but only after considerable exposure.”

“I see. Would you rather confront this book and wallpaper or that island of otherworldly Willows in the Danube that you and your lord friend encountered?”

“An unfair comparison. Truly, I would rather risk either of them rather than revisit that stony limbo in Wales and its,” he pulled a face, “unique locals under the earth.”

“More undead?”

“Oh, no. Very much alive. And old. And possessing far more anatomy than anything that near to a human shape ought to have.”

“How so?”

“You know how the eye of a snail works? Picture that. As a limb. In a torso.”

“I would rather not picture that, if I can avoid it.”

“No more than I wanted to receive a distinctly uninvited wrestling match from one. Hence my preference for the book, the wallpaper, and the Willows.”

“Any more…positive encounters?”

“Hmm. Have I told you about Miss Pleasance and her disappearing cat?”

“Was that not Griffin’s pet?”

“A different animal. This one comes and goes as he pleases. And he talks.”

More days, more weeks, more stories that oscillated across the full scope of phantasmagoria, from fantasy to terror, sometimes overlapping with both. All the while, Harker regained himself, as per their agreement. He ate, he worked his body and mind. Once he retrieved a page of the pipe organ’s sheet music from where it had fallen and slid under a sizable curio case. Before he could tell Harker he could simply fetch a copy, the young man had his hands under the base. He hefted it without upsetting a single item in its array, toed the sheet free, and gently set the case back in place with all the effort of a man moving a barstool.

During all this, he had not paused or even strained in his talk of, ‘The Case of Two Clarimondes.’ One Clarimonde a Parisian vampire, the other a German spider woman. The former had, by dint of her being far removed from Dracula’s brood and instrumental in breaking her namesake’s psychic possession of one Dr. Jack Seward, become their first official ally among the undead.

“Now we just need to shake hands with a lycanthrope and a poltergeist. Art says we may even have a Barghest staking out the grounds. …Captain?”

Harker had been holding out the sheet music for him to take for a full minute. Captain Nemo had not yet gotten around to realizing this.

“By any chance, have you taken to writing these events down? They would make for a fine series in themselves.”

“A series with a very limited audience,” Harker murmured, so low the Captain doubted he was meant to catch it. His voice rose to add, “The lost journal contained some of it, but aside from that, many of us have taken to recording consistent diaries. Mina transcribes it all to save everyone the pains of deciphering handwriting and phonograph marathons.” A cloud passed over Harker’s face as he said so. One that brought rain to the edge of his lashes. But before it could go further, he leapt ahead with, “Do you not record yours?”

“I—,” heat nettled in the Captain’s throat, “I had a companion once, who was an adamant journal keeper. He played biographer to many scenes, albeit incompletely from his perspective. For myself, I have put together a succinct record of the Nautilus’ history and purpose. Sealed and prepared for delivery unto the ocean for whoever might discover it, should my vessel see its demise at last. But put more broadly,” he took the sheet music gingerly, “no, I do not keep to an ongoing habit of such writing. All the eyes aboard our home have grown accustomed to what we do and encounter. The incredible has become commonplace. Trials of the waters, the beauty within and the beasts above it, all are as ordinary to us as the constant clamor held in a newspaper.”

“I find that hard to believe, all things considered. You are in love with the ocean as surely as any man loved his darling. You cannot have run out of awe for it, or words to frame as much.”

“No. There are not words enough in any language to encapsulate that. But my romance with the water is not the issue. Any man not living in worship of himself and his accomplishments will lose all poetry when forced to describe the former.”

At that, Harker summoned a tone so arid it might have dried the Atlantic to say, “How lucky then, that so many frauds exist in the world who are happy to write about their adventures to fill the void left by the honest and humble. Really, Captain, you can’t say this sealed memoir of yours will be no more than historic bullets and a manifesto alone?”

“For prudence’s sake, I do say so. Were I to make some novel of the entire scope of the Nautilus’ undertakings from its inception to the present, it would overfill the container and leave any reader with the impression I was some careless author who tossed his manuscript overboard.”

“It will be a loss if you do not make the attempt.” He smiled. A thing that had outgrown bitterness or guile and was simply a tired curve. “I have three months to burn before I die. Perhaps I can play secretary to the next great enterprise. We’ll see if my pen meets the task and convinces you to follow suit. You mentioned you once came across what might be Atlantis? That should provide some inspiration—,”

“Three and a half.”

“Sorry?”

Captain Nemo choked on hellfire and Antarctic ice as he met the young man’s gaze. Such a tired stare. A familiar one.

He has been here before. Counting the days.

“Not three months,” the Captain heard himself say. “Three and a half.”

“Is it? It’s rather hard for me to keep track of the days. I’m fairly certain I began my stay here in early May, but I fear I’ve quite lost the track of dates in all this. It certainly feels like a month since I left the sickbed.”

“The starvation bed. Have you taken lunch today yet? Or breakfast?”

“…You’re certain it’s not already dinner—?”

“Harker. Do not sabotage yourself.”

“Honestly, it only slipped my mind.”

“Then we must ensure it will not slip again.”

They began taking their meals together. It only took a few days’ worth of being caught nudging his food around before he gave in to clearing the plate.

“The vegetables too?”

“Yes. No cigar or liquor until you finish your seaweed.”

In the same vein, whenever a lull presented itself between sleep, steering, and searching, Captain Nemo found himself shadowing the young man. It was no reproduction of the period with Aronnax, even with all the sights and experiences he sought to lay out before Harker. It was the difference of engaging a capering dolphin with play versus trying to prod a morose goldfish back to life by shaking it in its bowl.

Worse, a goldfish that seemed as insistent on convincing the Captain the days were rushing by as adamantly as the Captain tried to insist they were crawling. Between the two of their perspectives, they grudgingly had to settle on the true passage of time or risk cries of deception from both sides. Earned or otherwise.

“It’s as much for your sake as my own,” Harker commented, perched up in a corner between wall and ceiling. A half-hearted attempt to avoid the dining table. An attempt that was nearly successful, in that no one could scuttle up to retrieve him. The Captain had simply brought the plates over on an end table, as well as a chair for himself, then proceeded to spear the fillets on driftwood skewers. These he flung at Harker with a marksman’s hand. Harker’s only defense was to eat the artillery. He gnawed them with a sulk; as much for the ruined plan as for the fact that he couldn’t deny the quality of the cooking.

Down below, the Captain set down his cutlery to ask, “How is a man planning his suicide to my benefit, exactly?”

The Maelstrom roared in his memory’s ear. His next bite sunk deep enough to bring blood to his tongue. Harker ate and shrugged.

“Leaving aside the simple fact that you shall not have to play chaperone any longer?” He cleared his skewer and turned it in his fingers. “There will be no chance left for my own superstition to become fact.”

“What superstition is that?”

“My increasingly well-founded belief that my mere presence might result in some fresh affliction of the bizarre falling on me and anyone in my radius. I have a not insignificant history with such things.”

“…You believe yourself to be bad luck?”

“Strange luck, let’s say. Which often skews towards the bad.”

“Your entire group appears guilty on that front, Harker. Do not hoard credit.” Harker only frowned over his skewer. “Consider where you are. Do you truly think that between the Nautilus and those sunken vampires, there is anything so impressive left in the ocean that your mere presence could lure to us? If there were, I can’t guess why it’s taken so long.”

“I cannot say. Only, it has seemed my lot to exit one uncanny situation only because I’ve tripped into another. I did not tell you the tale of my misadventure in Munich with its village of undead rushing at me in a hailstorm. Nor have I told you what ghosts and demons harried my escape through the forest as I fled the castle. I never committed those to paper and only Mina knows the whole of it. That stint in my life was narrowed down to the problem of Dracula, and throwing a series of disconnected jaunts through bogeyman territories wholly unrelated to the Count was neither important nor called for at the time. Yet they did happen. All in succession. All as I was trying to leave behind something stranger.”

“Perhaps it was merely that country.”

“Van Helsing tried to paint it as such. But I’m unsure. Mina did not escape her brush with Dracula unchanged. Whatever effects the supernatural might have on those who come through them, I think I must be thoroughly saturated. With all that has happened in the wake of triumphing over the brute in the snow, and, yes, with where I find myself now—I can’t help thinking my blundering into the abnormal is unavoidable. All of that being said, however much I would rather be dead than caged for life, I would gladly accept the next leap into the unearthly unknown to live or die by the experience: provided I did not have so many people to risk as collateral to the inevitable.”

“Inevitable, he says.” The Captain began loading up another skewer. “Just as you think your death is inevitable at the end of the four months. You thought it inevitable in your darkest hour in Transylvania. I thought it inevitable for myself, once too. Back when I had made a monster of myself and knew it.”

Know it.

“Such a grief stole over me, such a madness, that I tried to steer the Nautilus into its destruction. I, a thankless tyrant, who was prepared to end all and take my crewmen, who were my family, and my dearest companion, who was more…and my crewmen did not move to stop me, so complete was their loyalty and love, just as it remains today. I did not reckon this in full until it was nearly too late.”

It was too late, for some. For dear Pierre and his friends.

Is that how you want to remember it? Would it make this latest madness more sensible if you ignored your first and last visit to the shore? It was your hands that laid him on the sand. Yours and your men’s. Was it the madness of guilt? Or did guilt finally break through your insanity? Your selfishness? You, avenger at sea, judge and jury, who would throw the embers of redemption into the surf to cage another captive, to hoard a human being as though he were an animal to break, a replacement to fill the hollow in your breast that has calcified since the slaughter. All this, when you could simply tell him—

The last fillet was pierced with more force than it deserved.

“Self-destruction is never just self-destruction. No more than destruction of another affects only the destroyed. Like your monsters and mysteries on land, to go through any of them is to cause a ripple. A stain. Whatever you wish to call collateral. When faced by the ravenous wolves at the Count’s door, you knew at once that you would be committing a mistake to throw yourself to them when there was still the hope of another day. Hope that something better would happen.”

“It didn’t. I had to climb away—,” Harker said even as he clambered down from his corner, “—and pray against gravity and wolves just the same.”

“And lo! You did not plummet, you were not eaten. You lived to hunt the bastard down for his evils against you and those you love. You triumphed beyond measure, simply because you chose not to quit yourself. If you expect the inexplicable to come knocking—something more inexplicable even than you and I as we are now—who is to say it will not be the thing that makes living worth the wait?”

“Would that not entail some great force coming out of the depths to rattle me out of your grasp like the last mint in the tin?”

“Perhaps. Perhaps not.”

Say it, say it, just say it, you fool, you jailor, you grasping guilty lonesome old b—

“Yours is not a conventional life, Jonathan Harker. Yes, the inexplicable seems stamped upon it—but as you say, it has given you good along with the ill. Let yourself live long enough to give it the chance for the former.”

It was at this moment that Ridder came half-running into the room. His face wore the same look as the night he’d cradled the gruesome head of the Demeter sailor. He spoke briskly into the Captain’s ear. He repeated it when asked. And a third time.

“If I may guess,” Harker hummed, turning his new skewer in hand, “I’ll say that’s the Nautilus tongue for, ‘Something inexplicable is at the door.’ Am I close?”

“Eat your fish.”

The inexplicable was not quite at their door. It was floating under the moonlight, pulled parallel with a far more explicable sight. Evidently some manner of private ship, petite and well-made. It found itself abutted by what was, in a very literal sense, a ghost ship. Albeit with some sturdier revenants to judge by the apparent struggle the less grotesque vessel was having with their opponents. Such was the scene, unless everyone’s eyes deceived them through the spyglass, Captain Nemo included.

“You see, Harker? It’s not just you. Anyone can trip and fall into the unearthly.”

“I haven’t seen, actually. I’ve not had a turn with the glass.” Harker took it in hand and squinted through. “If they are ghosts, they’re far more tangible than the ordinary specter. Too fleshy. The people aboard the other ship are doing lethal damage, but—oh.” All the blood dropped out of the young man’s face. “Oh, God.”

“What? Harker, what is it?”

“It’s the Lucille.” His voice shook. “It’s—no.” The young man jerked his head away from the glass and whirled on the Captain in the same motion. Panic and wrath warred in his face, ultimately producing only a perfect rendering of urgency. “Captain, we need to go there now. We need to help them!”

Uneasy looks floated among them all.

Help meant ‘intercede.’ Help meant ‘show yourself.’ Help meant ‘aid an English ship.’

Not a warship. A boatful of unlucky tourists or coddled aristocrats, perhaps, but not a warship. Such a vessel would be a disgrace to any military, armed as the passengers may be. And do you not have some recompense to pay yourself, O avenger?

Before he could summon an answer for himself or his crewmen, Harker had him by the lapels. Grief and rage, terror and prayer twisted his countenance into a stricken mask. His eyes burned anew and might very well have steamed for the frenzied tears balanced in them.

“Now, Nemo! Please, God, we have to help them! The Lucille is Art’s boat! I saw him and the others on board and Mina is with them!” The crewmen tried warily to pry him off; Captain Nemo held them back with a look. Harker noticed none of this. Only quaked, trembling the Captain with him. “Please, please, it is dark even with the moon. They will not know you for anything but another inhuman oddity joining the fray. You could be a sea monster, or another ghost crew, some myth or legend or whatever else! They will not know you! They would never think to tell anyone of the Nautilus as anything but another detail in a ghost story, your secret would be safe!”

Yes, your secret, Captain Nemo. Brave Nemo, avenging Nemo, hiding Nemo. He knows what matters most here. Keeping secrets is always important to the plotting old monsters who lock him in their dungeon of choice.

“If it’s down to me—down to—,” the lump of his Adam’s apple jerked and choked the words short. “I will alter our arrangement. Save them. Save Mina! And I will stay and I will live here, if that’s what you want. Or better, if these enemies are more impervious in their death than the Demeter’s men, I can at least die keeping them from her. Not a suicide, you see? It would be alright, a death with purpose! And I will never be able to breathe a word of you! Anything, anything it takes, anything you say, just—please, we can’t let them die while we huddle here and watch. Please.” Wet tracks poured down both cheeks. “Please don’t let her die.”

Hindsight would teach those aboard the Lucille that this particular moon, on this particular date, at these particular coordinates, was the site of a most terrible shipwreck. There had been mutiny and bloodshed and an accursed treasure chest involved, as might be expected. What had not been expected was the reappearance of that ship and the irate crew members still out for blood to spill and bounty they could never spend. In their defense, extraordinary as their small league was, they had come out on these waters once again in search of another impossible occupant of the sea.

“It was invisible in the dark one moment, alight another, dark again,” Mina Harker had insisted through hoarse tears. “Jonathan must have clambered on it without realizing, just looking for some footing. The vampire followed him. They were just shadows. I saw him slice the thing’s head off—and the head fell away into some strange hollow. There was no splash for it as there was for the body. Between one moment and the next, there were a dozen human shadows rushing out of the black, swarming him. I heard him scream…” The rest of her words were lost under a hot coal that had grown in her throat. Irene gripped her free hand while Mina’s other ground against the miserable rictus of her lips, as if her wedding band might dam the grief.

“There was a flash of something. A spark,” Quincey had finished. Quietly. “Like they stuck him with a handful of lightning. The moon didn’t give away much, but it showed the lot of them dragging him down into some solid dark in the middle of the water. He was still moving. Just stunned. Then they were all gone. No rock, no reef, no islet to be found.”

Hyde made some ill-advised joke about, ‘Jonathan Harker, the reigning champion among abducted damsels’ that made even Gray throw a sidelong look. Jekyll was given his spot back in short order.

Months had been poured out in research and physical searching of the area and what possible entities might have absconded with the young man. Many a legend was unearthed concerning underwater kingdoms of old. Even a few unwholesome and unsane dwellers of the deep that appeared through cracks in reality according to their implacable eldritch whims, but such deities were accordingly quite busy with their own affairs and would be more likely to accidentally pulverize a man into screaming jelly with one misplaced tentacle than to meticulously incapacitate and capture one with a personal humanoid legion.

It was, to the surprise of few, Van Helsing who ultimately found some dots to connect. Rather, the dots connected themselves after hearing of the plight in question, and then came rushing to meet with them. Professor Pierre Aronnax, an old acquaintance and woeful audience to many an—often purposefully—incorrect speech to do with ‘facts’ concerning marine life that had given the poor Frenchman grey streaks before he’d even reached forty years.

“Ah, I see you travel alone for the first time in a good while, my friend. Did you leave good Conseil behind on your leave of absence?”

“Not precisely. Conseil has found himself other work since our, ah, excursion. Mr. Ned Land has taken him on as a partner of sorts. If only because I feel the two have begun a conversation that neither consents to give to the other as ‘having the last word,’ and so they have become quite inseparable as a result. But let us not dwell on that. Tell me of this disappearance into the water. Every detail you can spare.”

Details spared included written, typed, and spoken variants. All of which served to tint Aronnax in hues of chalk and cherry by turns.

“I suspect I may know the culprits. Culprit, rather, if it is the same powerful character whose people are as much an extension of himself as anything else.”

“Who?” That was Mina Harker, though her voice sounded less like herself and more like the steel slide of a guillotine. “Professor, who?”

Aronnax had added a seasick green to the white and red of his pallor. His gaze hopped about the room, wondering at the motley nature of its company. They even had a mummy in their menagerie to judge by the bandaged fellow in the chair beside him. The latter had said not a word and his dark lenses had seemed to observe first him, then Mrs. Harker, as if watching for a cue.

“It is a fantastical guess, for the man and his men have transformed themselves and their lives into the fantastical. There is every chance you will not believe me. And, though the man has committed great errors in his grief and vengeance, I would be as ashamed to reveal him to the world as I would be to see yet another wild rarity in nature ripped up from its home and kept in a cell to gawk at. His existence might be believed, it might be taken as fresh nonsense puffed up for the newsprint. God above, they might make a stage play of him. But whatever the initial thought, I know in my heart that the world would set after him like bloodhounds and do all in their power to drag him up, to rob him of his home and invention, and do worse than any revenge you would put him to.”

“How is that?” Another grind of mourner’s steel.

“Because all you know him for is stealing your husband into the sea. Were the world to know him, they would take him alive and he would spend the rest of his life, however long or short, being tortured for the secrets to his genius in the machine that he has made a haven. He would not even have the sanctuary of his mind that a common prisoner is allowed, for whatever government got their hands on him would spend the days trying to pry that treasure loose. Just as surely as they would set to replicating his work with the—,” none could tell if he wore more regret or longing in his face, “—the Nautilus.