#not even like. turkish culture. MAINSTREAM CULTURE!!

Text

As someone with a large danish and turkish family the cultural differences that come with visiting them insane. Do not flame me but my god. I do not prefer visits from turkish family. It is so formal for no reason. I am expected to serve them and take their annual “girl youve gotten fat. What are those tattoos” breakdown. 0 support for my interests. 0 things in common. Danish family b so chill. Granted i dont like a part of the family for being druglords but for the most part theyre so chill. Minding their own business. Offer u a drink and maybe a blunt. Real.

#i dont even consider myself turkish atp and it does make me semi sad#but im sooooo disconnected from the culture#not even like. turkish culture. MAINSTREAM CULTURE!!#I watched medcezir for the first time IN MY LIFE last year 😭😭😭#i do not know who Ahmet Kaya is.#I HAVE. NO IDEA. how ive lived here for 20 years and cant name 3 popular songs.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Jordan Hoffman

In Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer, the decision of Cillian Murphy's J. Robert Oppenheimer to make the leap from theoretical physics to practical applications is a personal one. "It's not your people they're herding into camps," he says to Josh Hartnett's Ernest Lawrence. "It's mine."

Oppenheimer's Jewish background (and that of many of the brilliant people portrayed in the film, like Albert Einstein, Edward Teller, Isidor Isaac Rabi, Richard Feynman, Leo Szilard and others) is a key component in their determination to prevent the Nazis from being first to create an atomic bomb. You would not know this, however, if you saw the movie in Arabic.

As reported in The National, an English-language news outlet based in the United Arab Emirates, the Lebanon-based company that translated the film for the region has dodged the specific word for Jews and, instead, has opted to use word ghurabaa that translates as stranger or foreigner.

Egyptian film director Yousry Nasrallah criticized the decision, saying "The Arabic translation of the dialogue was strikingly poor. There is nothing to justify or explain the translation of Jew to ghareeb or ghurabaa. It is a shame."

An unnamed representative for the film told The National that this is not atypical for Middle Eastern censor boards. "There are topics we usually don't tackle, and that is one of them. We cannot use the word 'Jew', the direct translation in Arabic, otherwise it may be edited, or they ask us to remove it."

They continued, "In order to avoid that, so people can enjoy the movie without having so many cuts, we would just change the translation a little bit. This has been an ongoing workflow for the past 15 or 20 years." (In 2013, though a large section of the Brad Pitt action film World War Z was set in Israel, Turkish translations changed all references to simply "The Middle East.")

There are several moments in the film in which the impact is blunted by this censorship. Oppenheimer's foe, Lewis Strauss (played by Robert Downey Jr.), is also Jewish, and mentions it in the film — but then is particular about the Americanized way his name ought to be pronounced. When Oppenheimer meets Rabi, who is first to voice ethical concerns about the creation of the bomb, he refers to himself and Oppenheimer as "a couple of New York Jews," marking themselves as distinct from mainstream American culture. The National reports that the translation reads as "inhabitants of New York."

Oppenheimer has seen tremendous box office success both domestically and internationally, with a cumulative gross of $650 million — a remarkable achievement for a historical drama. Last week it became the highest-grossing World War II film of all time, has extended its 70mm IMAX run in several markets, and even surpassed Star Wars: The Force Awakens as the biggest earner at Hollywood's Chinese Theatre.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

For many cultures across the centuries, common foods such as tea leaves and cheese have been used to predict the future. Ovomancy, or fortune-telling via eggs, is still practiced in the Caribbean and certain parts of Latin America. Photograph By Betty Bossi/Picture Press/Redux

Onions 🧅 🧅, Cheese 🧀🧀, Eggs 🥚🥚 —This Isn’t A Shopping List. It’s Fortune-Telling.

Kitchen divination has a long, cross-cultural history. In some places, the art never went away; in others, it’s making a comeback through social platforms.

— By Suchi Rurda | January 11, 2024

Predicting the future hasn’t always been synonymous with tarot cards and crystal balls. Centuries before astrology apps and dial-in psychics existed, people who wanted a glimpse into the future worked with what they had—food.

Loose leaf tea and Turkish coffee grounds (tasseography), onions (cromniomancy), eggs (ovomancy), and even cheese (tyromancy) have all been essential ingredients used in kitchen divination. But over time, these rituals faded from the mainstream. However, a recent resurgence in Pagan practices—crystals and tarot cards, astrology, and herbal magic—has brought this branch of fortune telling from the back of the pantry to the top of your TikTok feed.

Diana Espirito Santo, associate professor of social anthropology at Pontificia Universidad Católica in Chile, says that this growing appetite for spirituality shows that food-related divination practices were never really off the table.

“More modern and liberal ritual specialists can do divination practices in absentia. I would imagine that food-based forms of divination are easier to handle and have a wider scope for interpretation,” she says. “This makes them extremely attractive to a virtual audience, who can imagine how the divination result applies to them in creative ways.”

Here’s what you need to know about food divination and destinations where you can sample it.

What is Food Divination?

California native Amber Corvidae, a retired chef and practicing witch who lives in Brisbane, Australia, says food divination in the West most likely stemmed from the witch hunts and accusations of witchcraft beginning in the early 15th century. This includes tea scrying, which in 1700s England was often documented as an excuse to have tea with friends, “when in reality, those friends were either witches themselves or seeking spiritual counsel from witches,” says Corvidae.

In Zeytinköy, a Roma area in Antalya, Turkey, a fortune teller reads tea leaves. Photograph By Julian Röder/Ostkreuz/Redux

A photo from the 1900s shows brothers Carlo and Ermanno Coretti having their coffee grounds read by their mother in Trieste, Italy. Photograph By Archivio Gbb/Redux

However, in other parts of the world, people commonly relied on the “magic” of natural chemical reactions in foods such as eggs, cabbages, and nuts to understand their destiny. The Scottish practice of “pulling the kale” was a popular way to predict the qualities of one’s future spouse in the 1700s. The size and shape of the stalks indicated your would-be beloved’s physique, while its taste determined their temperament.

Ovomancy, one of the oldest recorded forms of food divination, is still practiced in the Caribbean and certain parts of Latin America to predict marriage, childbirth, and death. For example, on Good Friday, traditionalists would drop raw egg whites into a glass of warm water and examine the shapes they made, from a ship (future travel) to a coffin (impending death). David J. Kim, a professor of anthropology at Purchase College in New York State, says it’s “staggering how many people go to see shamans and fortune tellers in South Korea and the amount of capital it generates.”

Kim, who studies Korean shamanic practices, adds that rice divination is often used to commune with spirits. A shaman reaches into a golden bowl of uncooked rice, grabs a pinch, and counts the grains. An even number of grains means “yes” or indicates the presence of a spirit, while an uneven number means “no” or the lack of spirits.

A shaman uses a bowl of rice during a divination ritual in Yangju, 21 miles north of Seoul, South Korea. Despite living in one of the world’s most technologically advanced countries, many Koreans still consult shamans for medical reasons, divination, or personal advice. Photograph By Ed Jones/AFP/Getty Images

In Oaxaca, Mexico, maize diviners place a kernel of corn representing the seeker on a embroidered tortilla napkin. The fortune teller then tosses 12 (or more) kernels onto the table one at a time to search for an answer in the revealed pattern. Araceli Rojas, an archaeologist and professor at the University of Warsaw, spent time with the Ayöök people in 2007 and initially encountered only two maize diviners. But a recent visit revealed a new generation of practitioners intent on keeping these ancient fortune-telling methods alive.

Jennifer Billock, the Chicago-based creator of the Kitchen Witch newsletter, has been experimenting with—and writing about—the ancient craft of tyromancy. Divining the future with cheese was first mentioned in the writings of second-century-B.C. Greek historian and diviner Artemidorits the Dream-Interpreter. Followers of this cheesy magic use the patterns of fermentation, number of holes, and the shape of the cheese to answer specific questions. (You can pair this with a session of wine divination, known as oenomancy.) Billock says blue cheese works best, but she’s divined with everything from Colby Jack to a Kraft single.

In the Middle Ages, fortune tellers would use cheese to tell the future. They based their findings on factors such as the shape of the cheese, the number of holes it had, and which way mold grew on it. Photograph By Rebecca Hale, National Geographic

Where to Experience Food Divination

Travelers can book an in-person tyromancy session with Billock in Chicago. She teaches divination either one-on-one or at group workshops at cheese shops, wine bars, or tea houses.

In Istanbul, Turkey, you’ll find a smattering of cafés offering coffee ground readings in English along Ayhan Işık Sokak, a side street off the famous İstiklal Avenue in the Taksim neighborhood. Or get a free reading from AI-driven app Faladdin, where you simply upload a photo of the sediments at the bottom of your cup of Turkish or French press java. (Your daily latte or flat white isn’t going to cut it.)

In Santa María del Tule, a small town just a few miles west of Oaxaca City, Venus Rodriguez practices and teaches the ancient art of maize reading for anyone interested. But if you can’t swing a trip to Mexico, Rodriguez also offers online divination sessions. Find more info on her Instagram.

Women read each others’ future in their coffee cups at a street café in Istanbul. Photograph By Jerry Lampen/Reuters/Redux

Find tea leaf readers at the 94-year-old Bottom of the Cup tearoom in New Orleans, Louisiana, or book a 90- or 120-minute session of tea reading therapy at Dublin Wellbeing Centre in Dublin, Ireland.

Take an online course on Udemy to learn how to read a coconut or kola nut, a practice from the West African Yoruba religion, which dates back nearly 8,000 years.

1 note

·

View note

Note

What are the most popular beauty tricks among Egyptians?❤

First off I love your blog, sending love from Cairo <3

A lot of modern day Egyptian beauty secrets are inspired by the ancient Egyptians. It's really interesting to see how these practices have been preserved through generations and have survived migration and colonisation.

Salon culture

Visiting Salons regularly is very big here. There is an abundance of salons EVERYWHERE and the prices are very reasonable. Many will choose to get their hair done weekly. Getting manis and pedis is also a popular choice. Regular facials are also increasing in demand.

I would recommend the movie 'Caramel' to those who want to learn more about the salon culture in the MENA region, it's incredibly accurate.

Kohl

The ancient Egyptians used to apply kohl for purification purposes and to protect themselves from any evil. My grandmother applies kohl daily, she makes it at home, for purification purposes. Most girls nowadays will apply it to make their eyes look more intense. It's definitely my favorite step of my makeup routine, it makes such a nice difference. I'll probably have to make a whole post on kohl, how to make it, how to use it and the history behind.

Lemon water rinse

My grandmother always told me to soak my hair in lemon water. personally I like to use it as a rinse (and mix it with ACV). It makes your hair very shiny and is good if you have hard water.

Henna

Henna! what a fun topic. My grandmother and my mom use henna on their hair, it is a natural hair dye and it also strengthens the hair and is good for it. I do a henna mask every 3 months, the color doesn't really show up since I have black hair but I do it for it's benefits. When I visited the new museum and got to see the mummies of Egyptian royalty they ALL had their hair dyed with henna.

Henna designs are also very popular especially around special occasions or religious holidays. Henna was first used for it's cooling properties but now it's more of a fashion statement. I absolutely love going to salons and getting a henna design on my hands.

Some people also like to apply henna to their nails, you end up with this reddish orange, I am personally not a fan of it. It does strengthen your nails though.

Olive oil, Argon oil and Castor oil

Pure, natural oils are very popular here but especially the 3 mentioned above. Castor oil is sourced from Egyptian farms, it is commonly used to grow hair and is also used on the lashes and brows. Olive oil is, most commonly, from Palestine, it is used very heavily in cooking due to it's health benefits, it is also used as a hair oil or as a body moisturizer. We get our argon oil from Morocco, it is commonly used for the hair and in face masks.

Sugaring

The first method of hair removal I was introduced to was sugaring. To make the paste all you need is sugar, honey and lemon, it's all natural. It was first used by the ancient Egyptians and now by modern day Egyptians, It's less painful than waxing and exfoliates the body and removes dead skin cells. It's definitely one of my favorite methods of hair removal.

Rose water

There are many uses for rosewater. It is also occasionally used for cooking. Rose water can be used as a moisturizer or as a facial spray. Rose water is also used for soothing after hair removal. It is also a common ingredient in masks. It's a wonderful ingredient and it's on pretty much every Egyptian's dresser.

Moroccan Hammam and Ghassoul

While technically a Moroccan practice it's very common all over North Africa and the Middle East. I have a moroccan relative who gets a Moroccan hammam once a week, sometimes even more. I have memories of my mom getting at home Moroccan hammam services weekly.

Moroccan hammas consist of sitting in a steam room and you are given some ghassoul, it is a type of soap made of clay from mountains in Morocco, you are also given some exfoliating gloves.

First, you exfoliate your body, then you wash your hair, the ghassoul clay can applied all over your body, face and hair as a masks. Occasionally henna is used on the hair. Massages with Argon oil afterwards are very common as well.

Musk and jasmine

These are two of the most popular scents in Egypt, among men and women. They are usually applied in the form of a fragrance oil.

Nivea cream

Nivea is surprisingly popular in Egypt. It is used daily all over the body for moisturization.

Glycerin

Hyaluronic acids hotter sister. It's been inside every Egyptian house I have ever been in. It's usually the same red tub.

Hammam cream and Hammam zeit

Hammam cream and hammam zeit are used to nourish the hair before washing it. Hammam zeit is done on the scalp, it is done by applying an oil, usually from the ones mentioned above, on your scalp. Hammam cream is used for the rest of the hair shaft, you apply a hair mask to the ends of your hair. Both are done simultaneously. You then will cover your hair with a shower cap/ plastic bag and wash it after a few hours.

Avoiding sun exposure

Due to colorism and modesty people tend to avoid the sun like the plague. Pale skin is definitely the beauty standard so many avoid tanning, that coupled with the fact that many people's bodies are covered from head to toe means barely any skin is exposed to the sun. On the plus side, skin cancer rates are quite low.

Embracing your curls

This is quite new but I have noticed more and more Egyptians embracing their curls, it was only a couple years ago when people would get their hair chemically straightened because that was the trend so it's nice to see people not fighting against their curls and damaging their hair.

Honey

I was always told as a child to take one spoon of honey per day for it's health benefits. It's also used as a moisturizer and in masks and occasionally in baths. It is said that Cleopatra used to soak in a bath full of milk and honey for it's exfoliating and moisturizing purposes.

Frankincense and Myrrh

They are most commonly soaked in water and drank daily. they have endless health benefits and they are incredibly good for your skin and hair as well. They are also common ingredients in masks. Occasionally, they will be used as part of bukhoors to purify the house.

Aloevera gel

Aloevera is used to soothe sunburns and is blended and applied to the hair shaft. Many people rub a slice of aloevera on their face daily.

Cornflower + rosewater mask

This is a mask that my cousin used to make ALL the time. It's really simple, just a blend of cornflour and rosewater, it smells HEAVENLY and makes your skin super soft.

Makeup trends

A winged liner and red lip combo is something that I have been noticing is getting more and more popular.

Hair trends

Straight short blonde hair and a wavy Balayage are common looks, and of course embracing your curls is increasing in popularity.

Fashion trends

Modest fashion is mostly inspired by Turkish fashion, other than that many of the mainstream fashion trends are veryy popular here. The whole boho chic/ hippie look can be seen all over Sinai especially in Dahab. Not everyone dresses modestly, although it does seem like it. It's always nice seeing the fashion scene in Cairo and Egypt evolving.

Diet + Physical activity

I'll keep this one short. Lots of fresh fruit, very little processed food and overall nutritious food. Swimming and tennis are some of the most popular sports here.

570 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Search for Noah's Ark

Many ancient cultures had accounts of a hero surviving a divine flood by building a giant boat, but the story of Noah (Genesis 6-9) stands out, since it is included in the canon of the Abrahamic religions. For centuries, it was not unusual for Jewish, Christian, and Muslim writers to report that Noah's Ark was still sitting on the mountain where it came to rest at the end of the story. But it wasn't until the 20th century that a documented expedition went to look for it.

[Above: A man stands between Mount Ararat, where explorers typically look for Noah's Ark, and a sign for Noah's Ark National Park, the official location of the ship according to the Turkish government.]

The Bible says Noah's Ark landed in "the mountains of Ararat," without any clear indication where that would be. A 4th century Latin edition translated "Ararat" as "Armenia," popularizing that association in Western Christianity. The Armenians themselves used Greek or Syriac bibles, so they only learned of the Ararat-Armenia connection centuries later, from visiting crusaders. Thereafter, the sacred Armenian mountain Masis has been known as "Mount Ararat." Since the 1920s, the mountain has been a part of Turkey, which calls it Ağrı Dağı ("mountain of pain").

After the first confirmed ascent of Mount Ararat in 1829, it became more plausible that someone might go up there and look for Noah's Ark. But the idea wasn't taken seriously until the 1940s, when an article circulated about a Russian pilot spotting a giant wooden boat on Ararat during World War I. Supposedly, the czar ordered a thorough exploration of the structure, but then those no-good godless commies took over and suppressed the findings. The story was ultimately discredited, but not before it stoked the imaginations of American Christians that were eager to prove that the Bible was literally true.

Fascinated by the Russia story, realtor Eryl Cummings and his wife Violet devoted the rest of their lives to tracking down stories about Ark sightings. These tales typically involved American soldiers who said someone showed them a photo of the Ark during World War II, or old Armenian immigrants who supposedly visited the Ark as children. "Ark fever" heated up, though, when a sighting was reported from Turkey. In 1948, Eryl was invited to lead an Ararat expedition planned by retired missionary Aaron J. Smith. Cummings declined, however, and Smith ultimately led the trip himself the following year.

The 1949 expedition is instructive, because it sets the tone for all subsequent attempts to visit Ararat in search of the Ark. Upon arrival, Smith was beset with bureaucratic delays. Permits needed to be paid for, and local authorities rejected clearances that had been granted at the federal level. Reading between the lines, its clear to me that Ark-seekers would pay anything to achieve their dreams, and corrupt Turkish officials took full advantage of that. The team quickly depleted their funds, and didn't get to the mountain until the end of the climbing season.

It's also telling that there hasn't been a lot written about Smith's mission, not even by the Ark hunters who followed in his footsteps. It's much easier to find stories about the Fernand Navarra controversy in the '50s and '60s, or people who couldn't even prove they'd been to the mountain. And it's Eryl Cummings, not Aaron J. Smith, who came to be seen as the father of the movement. There's a simple reason for that: Smith put in the work, but he didn't find anything. Cummings, on the other hand, accumulated all of the tantalizing stories of people who might have found something, which could become a useful lead for the next expedition.

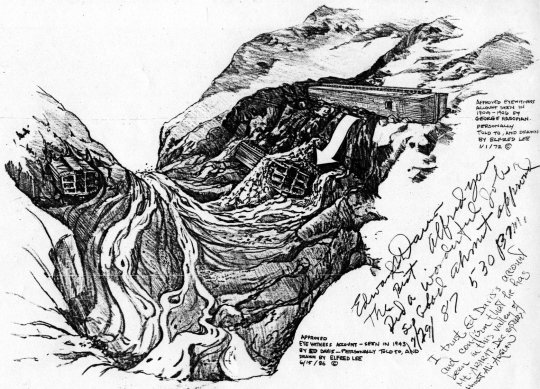

[Above: Reconciling descriptions from two purported eyewitnesses, Elfred Lee illustrates the collapse of Noah's Ark into Ahora Gorge. The gorge was formed in 1840 by a powerful earthquake, which happens to precede the earliest alleged sightings in modern times. Violet Cummings suggested that the quake was divinely ordained to reveal the Ark and usher in the Apocalypse.]

The 1970s saw a wave of books about the search, most of which derived their information from the work of Mr. and Mrs. Cummings. Violet and other writers cast the quest in an apocalyptic light, suggesting that God had hidden the Ark all this time only to reveal it as a sign that the End Times were imminent. The implication was that Noah's Ark could not be discovered until the appointed hour but, paradoxically, Judgement Day will be stalled unless believers find the ship as soon as possible.

"Arkeology" arguably peaked in the 1980s, when astronaut Jim Irwin took up the search. By that point Turkey was wary of letting amateur climbers wander around so close to their border with Iran and the Soviet Union. But the eighth person to walk on the Moon was able to open some doors and, more crucially, cut through some red tape. However, Irwin still had to deal with the punishing conditions of Mount Ararat itself. His adventures there are best remembered for the injuries he sustained, and the heart issues that made it increasingly unwise for him to return year after year.

Jim Irwin no doubt inspired a new generation of Ark-seekers, but by the late 1990s the community was bitterly divided about where to look. For thousands of years, legends suggested that the ship was in plain sight for anyone who dared to climb up and find it. But fifty years of aerial reconnaissance, satellite photography, and boots on the ground had proven otherwise. Debate intensified about whether Ararat was even the right mountain, and about the validity of other possible sites, forcing people to re-evaluate the established lore surrounding the quest. So you end up with one "arkeologist" attacking the reasoning of another, often with logic that could be extended to dismiss the entire search.

[Above: In 2010 Noah's Ark Ministries International released photos like this one, purportedly taken inside a massive wooden structure on Mount Ararat. NAMI refused to reveal the location for independent verification, citing security concerns. Within days of the announcement, former associates of NAMI came forward accusing them of staging the whole thing.]

That background of in-fighting put a damper on a 2010 press event claiming that a Hong Kong evangelical group had found the Ark on Ararat. You'd think video footage of this discovery would delight Ark hunters. On the contrary, many were as skeptical as mainstream scientists. The feuding over which Ark theories were right or wrong had left them wary, because if some flaky story captured the public imagination, it might discredit the entire movement. Which is ironic, considering that the movement wouldn't exist at all if not for an urban legend about a Russian cover-up.

At a glance, it may seem like "Ark fever" is part and parcel with religious fundamentalism, or maybe just a specific flavor of Christian anti-intellectualism. However, even some influential creationists have debunked the search for Noah's Ark. There's no scriptural basis for assuming that God arranged for the Ark to remain intact until modern times, or that it was meant to be rediscovered, or that locating it would have any bearing on the end of the world. The entire rationale for the search is that dozens of unconfirmed reports can't all be wrong, which isn't a solid foundation for an archaeology project.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Cinematic Outcoming.

From Istanbul to Chicago, and C.R.A.Z.Y. to Spirited Away, Letterboxd member, writer and film programmer Emre Eminoğlu explores the films that drove his gay awakening.

“I see it as my duty to never shut up about how representation matters.” —Emre Eminoğlu

I was one of the luckiest ones, yet I had no idea how lucky I was. Growing up in Istanbul, Turkey, a predominantly patriarchal, conservative and homophobic society, my luck was being born into an open-minded, secular and loving family.

In this bubble, I was isolated from the struggles of the majority of my people. I was not bullied at school by my peers, I was not forced into being someone else by my family. Yet I still had that voice in my head. As soon as I realized something could be different with me, I became my own bully and forcefully adopted a fictional persona: ‘exceptionally normal’.

Coming out was hard, but coming out to myself was harder. Although I was perfectly aware of my sexual identity, I could not come to terms with the possibility of being ‘abnormal’. Cue cinema. Watching films was a way of escape for high-school Emre—it still is—and it was inevitable that I would come across some LGBTQ+ films. I was not consciously in search of a ‘truth’ about myself but I started seeing my reflection in them, as they slowly disarmed the bully I involuntarily created.

Twenty years later, now, as a 34-year-old gay man professionally writing on cinema and television, I see it as my duty to never shut up about how representation matters. Streaming LGBTQ+ shows on various platforms, seeing widely released, mainstream LGBTQ+ films, listening to the music of openly LGBTQ+ stars, and hearing words of wisdom like “If you can’t love yourself, how in the hell you gonna love somebody else?”, I am confident that the personal, inner bully that I created twenty years ago would not survive a week in today’s world.

‘C.R.A.Z.Y.’ (2005)

Jean-Marc Vallée’s C.R.A.Z.Y. (2005) was definitely not the first LGBTQ+ film I ever watched, but it was an invaluable juncture in my life. It was a hot summer in Istanbul, freshman year of college was over. One of my best friends, who had been accompanying me through most of my cinematic discoveries, told me about a French-Canadian film with this guy on the film poster with David Bowie makeup on his face. We headed to an independent theater in Kadıköy to see it.

Zachary Beaulieu was different. As the lone gay son in a family of five boys, he too was forcefully adopting a fictional persona, and his way of escape was music. He was constantly worried about how to be worthy of his parents’ love, how to realize their ideals of him, and how his difference and truth contradicted all of that. Zac’s 1960s basically mirrored my story in the 2000s. I perfectly muted the life-changing enlightenment I was going through and did not vocalize my inner screams.

In two hours, C.R.A.Z.Y. helped me realize my true self and admit my sexual identity after all those years. It was a personal threshold I had been longing to cross… but there was still a lot to go through.

‘Les Amours Imaginaires’ (Heartbeats, 2010)

Liking someone, falling for someone, being loved, dating someone, sex, refusals, misinterpretations, heartbreaks, break-ups, bad sex. On the other side of the closet, I was being introduced to new, sometimes euphoric, sometimes gut-wrenching experiences. But coming out to my friends was still a challenge. I was feeling so lonely keeping all these wonderful and horrible experiences in my chest.

But I was not alone: LGBTQ+ films were my life’s understudy. The same heartbreaks, worries, and disappointments I was going through were right there on the silver screen. I took note as two best friends, Francis and Marie, fall for the same guy and navigate their friendship in Xavier Dolan’s Les Amours Imaginaires (Heartbeats, 2010). I studied how a popular student, Jarle, falls for the new guy in school, but cannot risk his reputation to be with him in Stian Kristiansen’s Mannen som Elsket Yngve (The Man Who Loved Yngve, 2008) and I watched as close friends Tobi and Achim become lovers, until one’s need to keep everything secret threatens to destroy the relationship in Marco Kreuzpaintner’s Sommersturm (Summer Storm, 2004).

Things were not always accessible via online platforms and the internet, so film festivals were often the only chance to see the latest independent and queer films. Two of the biggest film festivals in Istanbul, thankfully, had LGBTQ+-focused sections; !f’s Gökkuşağı (Rainbow) and Istanbul Film Festival’s Nerdesin aşkım? (Where are you, my love?) felt like home.

‘Tomboy’ (2011)

Being the lone avid cinephile among my friends, I was used to seeing half of my festival picks alone. Even before coming out to myself, my hopes for a romantic relationship included, among other things, having a festival partner. When I, fortunately, found the one, I was delighted to have also found the perfect festival partner. Shortly after our first month together, the first film we saw at a film festival was Céline Sciamma’s Tomboy (2011).

Although I was a 24 year old cis man, I was more than able to empathize with the title character, a ten-year-old trans boy. With his family unaware of his true identity, Mickaël experiences the liberation of a fresh start when ‘mistaken’ for a boy after they move to a new neighborhood—finally able to introduce himself as Mickaël, not Laure.

Changing my career path, a new job in the creative industry, and a stable relationship had similar effects on me. I was still not completely out to my parents, or some of my friends, schoolmates, and acquaintances from my past, but I was freed of the obligation to explain anything to my new friends or colleagues. I would proudly introduce them to my boyfriend, or simply correct people by saying I was attracted to men during a conversation. The perfect festival partner turned out to be a perfect partner as well—over the past ten years, he has helped me grow and be proud of myself.

‘Weekend’ (2011)

We moved in together in the fifth year of our relationship. Right above our bed hangs a poster of Andrew Haigh’s Weekend (2011). At the time we saw it, it was just another film that we watched together and liked—no significance, no symbolism. It is the story of two young men, Russell and Glen, who are fascinated by the connection they find between each other, and are surprised how their one-night-stand evolved into the perfect weekend. When Glen reveals that he will be leaving for another country the very next day, it only makes their connection stronger, and their time together more precious. Being a timid and socially anxious person, none of my romantic relationships or my friendships had formed this organically. Even my first date with my partner was a disaster. We built what we have now over time, slowly and patiently. I did not believe in ‘weekends’.

And yet, one summer night, we met a guy on Grindr, as we occasionally did. What we thought was just another one night stand was in fact a transformative experience for us both. Intense conversation, a triple connection, the drinks we enjoyed instead of hurrying to bed, and the passionate sex turned that casual one-night-stand into a magical reality for us. We realized that we still had feelings and instincts to discover in ourselves and in each other. Over a week-long, unexpected, unpredictable polyamorous fling, we learned to act as one instead of two—only to find out that he was leaving for another country the very next week. This was our ‘weekend’.

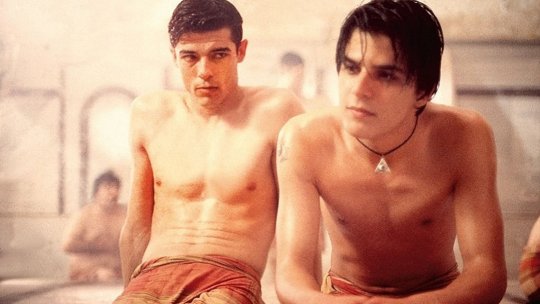

‘Hamam’ (Steam: The Turkish Bath, 1997)

Thinking how LGBTQ+ films of other cultures and languages had played a significant role in some precious, threshold-crossing moments of my life, it was alienating not being able to feel embraced and represented openly in Turkish cinema. There were certainly multiple Turkish LGBTQ+ films or characters, but they were in films addressing more urgent issues—right to live, violence against LGBTQ+ individuals, honor murders, trans murders—rather than the nuanced experience of queer love.

Although I discovered it years after it was released, Italian-Turkish director Ferzan Özpetek’s Hamam (Steam: The Turkish Bath, 1997) was a mind-blowing experience for me. The relationship, and the sexual tension, between Francesco, the Italian heir to a building with a Turkish bath in it, and Mehmet, the young son of the family managing the compound, felt much closer to my story and my cultural, familial identity.

Aşk, Büyü vs. (Love, Spells and All That, 2019)

Today, I am glad to see more and more filmmakers finding the courage to maintain the LGBTQ+ narrative in Turkish cinema, despite the oppressive, intolerant and exclusionary policies. Some are telling the youthful, urban stories I was longing for at the time: In Leyla Yılmaz’s Bilmemek (Not Knowing, 2019), Umut, a high-school athlete from a middle-class family in Istanbul, is bullied by his so-called modern and open-minded teammates after not replying to a query about whether he is gay or not. In Ümit Ünal’s Aşk, Büyü vs. (Love, Spells and All That, 2019), Eren and Reyhan, two adult women reunite in the magical atmosphere of The Princes’ Islands on the Istanbul coast, decades after they were forcefully separated by their parents.

The story of me coming out to myself all started with an urge to escape reality through cinema, and on the way, I found films that gave meaning to my muddled existence. When I saw Levan Akin’s And Then We Danced (2019), I smiled as I noticed the Spirited Away poster in Merab’s room; this minor detail another reminder that I was not alone. Merab, a gay dancer who is part of a very traditional and conservative Georgian dance company, was dealing with similar challenges in his life. He was trying to discover his true identity in a society that does not celebrate being different. He was too, finding an escape in cinema.

Coming out was hard. It still is. A recent Instagram post by the 27-year-old actor Connor Jessup, who came out as gay two years ago, reminded me coming out is not a single moment, but a never-ending process, a ‘becoming’. He writes, “When I first came out, a friend wrote to me and said, ‘Now you can really start coming out.’ Start? I thought. I just did it. But he was right. […] I’m going to keep trying. I’m going to keep looking.”

I keep trying, and looking. Learning about myself, my identity, my relationship. And LGBTQ+ films keep helping and inspiring me, just as they did in my journey to accept myself and become the person I am today. This is the power of cinema; unconsciously, you see your past, actuality and possibilities through the stories filmmakers tell. And I am so grateful to these filmmakers.

Related content

The Ten Greatest Turkish Films of All Time, according to the Turkish Film Critics’ Association

Emre’s Favorite LGBTQ+ Films: a personal top 50

Queer Films in Turkish Cinema—a list by Atakan

The Top 100 Turkish Movies of the 21st Century: Emre’s personal favorites

#letterboxd#pride#pride 2021#lgbtqia cinema#lgbt film#turkish cinema#turkish film#queer cinema#coming out#jean marc vallée

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

C/O Berlin Magazine | It’s a space for everyone, and everyone can come in — Thoughts for the future

“I cringe when I hear words like ‘diversity’ and ‘inclusion.” To quote the civil rights activist, philosopher, and writer Angela Davis, “diversity” and “inclusion” are terms that you, dear reader, might have also stumbled across in recent months, whether you wanted to or not. Inspired by global Black Lives Matter protests, mainstream media, corporations, and other institutions finally realized – in some cases as it seems overnight – that racism is also an intractable problem in Germany. Unfortunately, we need more than just hollow words and empty promises to solve this problem. You might be thinking to yourself: “But didn’t people take to the streets or write opinion pieces in newspapers to protest structural racism? And didn’t major institutions promise to offer diversity and inclusion workshops in discussion after discussion on television?” Perhaps, but don’t be fooled. Instead of critically questioning the role that white decision-makers play in perpetuating systemic racism, “society” was blamed. Over and over again, Black* people were asked to answer if they had really experienced racism through scrutiny of their real-life stories, while predominantly white “experts” were invited onto talk shows to discuss the so-called “racism debate”. Profound, structural changes are still lacking, at least as of the time this text goes to print.

Presence equals power. This brings us to the current moment where you are reading these words about British photographer Nadine Ijewere’s solo show at C/O Berlin. Nadine Ijewere is the first Black woman to be given a space that has previously been occupied almost exclusively by white men. As such, this exhibition is significant not only for Black photographers, but for everyone more used to being treated as the object than the artist or curator in spaces like this where many people don’t feel welcome or simply don’t exist. As trivial as it may sound, visibility comes from being able to hang pictures on a wall—or write these lines.

Joy as an act of resistance. Nadine Ijewere belongs to a generation of artists and creatives who have realized that there are more options than simply following the traditional path. Knowing that society has long since changed—even if many gatekeepers in fashion, art, and the media still cling to the status quo—this DIY generation is creating its own platforms to elevate their own role models with an army of loyal followers. In their work, representatives of this generation create worlds that rarely center Eurocentric beauty norms. The same goes for this young British artist, whose work shows people in all their beauty and uniqueness. Her photographs regularly appear on the pages of British, American and Italian Vogue, i-D, or Garage, and she has collaborated with brands such as Nina Ricci and Stella McCartney. Ijewere proves that beauty is multifaceted and that fashion is fun and for everyone.

More than a seat at the table. When artists like Ijewere make it to the top, it’s not because of nepotism, tokenism, or diversity as a trend, but despite all the obstacles that have been put in their way. And instead of assimilating after being accepted by the old guard, they continue to write their own rules. In Ijewere’s case, this means not only working with diverse models and teams, but also passing her knowledge on as a mentor to keep the proverbial door open. She’s less driven by the desire to stand out from the mainstream than she is to give back by inspiring younger generations, who are able to see themselves in magazines. “Within the time I have, I’ll use every opportunity I get and every space I can get into to expand the horizon of others.”

Representation matters. Celebrating Black people and people of color in a traditionally white space was also the goal of “Visibility is key – #RepresentationMatters,” a watershed moment for the German lifestyle magazine industry when it launched on vogue.de in spring 2019. The goal was to take first steps toward a forward-thinking future where inclusion and diversity would no longer be mere buzzwords, but lived practices. Part of that effort meant ensuring representation in front of as well as behind the camera. The results weren’t perfect and they might not have led to social change, but we proved that there isn’t a lack of creative talent among Black and Brown people in Germany. If anything, we proved that these talents are often denied the space to develop their full potential.

Ideas for the future. As you see, dear reader, it takes teamwork to bring about long-term change, and for the first time the doors are open a bit. Nadine Ijewere's exhibition shows this, as does being able to write these very words in the C/O Berlin Newspaper. In the statements below, we asked German and international artists and creatives to envision a future where representation and inclusion are lived practices instead of rare exceptions. The results are ideas for a future that is reachable—as long as we all keep working towards it every day. Together.

Nadine Ijewere, artist

Art is about art. It’s not about you personally. That’s why artists need to be seen as artists. We all get stereotyped and put into the same box—but we have our own identity. We are put into the same space just because we are Black, but we are all very different people.

Edward Enninful, OBE, Editor-in-Chief of British Vogue

Nadine is one of the leading fashion photographers of her generation. She’s not only inherently British in her work, she’s also Black British. She really understands the complex mix of culture, fashion, beauty, and the inner working of a woman, so when you see her images, it’s never just a photograph. There’s also a story and a narrative behind it.

Benjamin Alexander Huseby & Serhat Işık, designers for the label GmbH

Our work has always been about wanting to show our community and culture to tell our stories as authentically as we can. It was never about “diversity”, but about being seen. We want to create a world where not only exceptional Black and Brown talents no longer have to be truly exceptional to get recognition for their work, a world where we no longer are the only non-white person in the room because we built the motherfucking house ourselves.

Mohamed Amjahid, freelance journalist and author, whose book Der weiße Fleck will be published by Piper Verlag on March 1, 2021.

It's time that Black women become bosses. Gay Arabs should get to call the shots. Refugees belong on the executive boards of big corporations. Children of so-called “guest workers” should move into management positions too. People with disabilities should not just have a say, they should make the decisions. Vulnerable groups deserve to put their talents and ideas to work in the service of the whole society. Not every person of color is automatically a good leader by virtue of their background, but all-white, cis-male executive boards are certainly incapable of making decisions that are right for everyone. That’s why we need more representation at the very top, where the decisions are made.

Melisa Karakuş, founder of renk., the first German-Turkish magazine

For a better future, I demand that we educate our children to be anti-racist and to resist when others or when they themselves are subjected to racism. I demand that discrimination is understood through the lens of intersectionality and solidarity! I demand that even those who are not affected by racism stand up against it! This fight is not one that we as Black people and people of color fight alone—for a better future, we all have to work together.

Tarik Tesfu, host of shows including the NDR talk show deep und deutlich

When I look in the mirror, I see someone who grew up in the Ruhr region and loves currywurst with French fries as much as Whitney Houston. I see a person who has his pros and cons and who is so much more than his skin color. I see a subject. But the German media and cultural system seem to see it differently because far too often, Black people are degraded and made into objects for the reproduction of racist bullshit. I'm tired of explaining racism to Annette and Thomas because I really have better things to do (for example, my job). So get out of my light and let me shine.

Ronan Mckenzie, photographer

The future of our industry needs to be one with more consideration for those that are within it. One that isn’t shrouded in burnout and the stresses of late payments, and one that doesn’t make anyone question whether they have been booked for the quality of their work or to be tokenized for the color of their skin. The future of our industry needs to go beyond the performative Instagram posts and mean-nothing awards, to truly sharing resources and lifting up one another. Our industry needs to put its money where its mouth is when words like “support”, “community” or “diversity” slip out, instead of using buzzwords that create an illusion of championing us. How there can be so much money in this industry yet so many struggle to keep up with their rent, feed themselves, or just rest without worrying about money is truly a travesty. If this industry is to survive then we who make it what it is need to be able to thrive.

Ferda Ataman, journalist and chair of Neue deutsche Medienmacher*innen

A recent survey of the country's most important editors-in-chief revealed that many of them think diversity is good, but they don't want to do anything about it. This is based on the assumption that everyone good will succeed. Unfortunately, that’s not true. It’s not just a person’s qualifications that are decisive, but other criteria as well, such as similarity and habit (“XY fits in with us”). It's high time that all of us—everywhere—demand a serious commitment to openness and diversity. Something is seriously wrong in pure white spaces that can’t be explained by people’s professional qualifications alone. Or to put it differently: a good diversity strategy always has an anti-racist effect.

Nana Addison, founder of CURL CON and CURL Agency

Being sustainable and inclusive means thinking about all skin tones, all hair textures, and all body shapes—in the beauty industry, in marketing communications, as well as in the media landscape. These three industries work hand in hand in shaping people’s perceptions of themselves and others. It’s important to take responsibility and be proactive and progressive to ensure inclusivity.

Dogukan Nesanir, stylist

The current system is not designed to help minorities. By giving advantages to certain people and groups, it automatically deprives others of the chance to attain certain positions in the first place. That's why I don't even ask myself the question "What if?" anymore. My work is not about advancing a fake worldview, but about highlighting all the real in the good and the bad. I strongly believe that if some powerful gatekeepers gave in, if representation and diversity happened behind the scenes and we had the chance to show what the world REALLY looks like, we wouldn't be having these discussions at all. I don't just want an invitation to the table, I want to own the table and change things.

Arpana Aischa Berndt & Raquel Dukpa, editors of the catalog I See You – Thoughts on the Film “Futur drei”

In the German film and television industry, production teams and casting directors are increasingly looking for a “diverse” cast. Casting calls are almost exclusively formulated by white people who profit from telling stories of people of color and Black people by using them, but without changing their own structures in the process. Application requirements and selection processes in film schools even shut out marginalized people by denying them the opportunities that come with being in these institutions. People of color and migrants as well as Black, indigenous, Jewish, queer, and disabled people can all tell stories, too. Production companies need to understand that expertise doesn’t necessarily come with a film degree.

Vanessa Vu & Minh Thu Tran, hosts of the podcast Rice and Shine

It may be convenient to ignore entire groups, but we are and have been so much more for a very long time. We contribute to culture by making films or plays and bring new perspectives to science, politics, and journalism. We’re Olympic athletes, curators, artists, singers, dancers, and inventors. We dazzle and shine despite not always being seen. Because we have each other and we’ve created opportunities to do the things we love. We’ve created platforms for each other and built communities. Slowly but surely we are finally getting applause and recognition for the fact that we exist. That's nice. But what we really need is not just the opportunity to exist, but the opportunity to continue to grow and to stop basing our work primarily on self-exploitation. We need security, reliability, and money. That's the hard currency of recognition. That would mean being truly seen.

*Black is a political self-designation and is capitalized to indicate that being Black is about connectedness due to shared experiences of racism.

Written by: Alexandra Bondi de Antoni & Kemi Fatoba

C/O Berlin Magazine April 2021

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Cancel culture” is nothing new, so why are we acting like it is? Those in power have written their own version of history as they’d like it to be remembered for ages. That “winners write history” is simply another way of saying that selective erasure (or canceling) of inconvenient truths is built into the fabric of documenting history.

What’s new is that now we’re looking backward to “uncancel” some of the important stories not widely shared about groups of people who have more power today than they’ve had in the past to record their truths for a broader audience.

An exemple is how has been washed, cleaned and packed up, the figure of Christopher Columbus in history books and mainstream european culture.

Some facts that you must know about Christopher Columbus:

- Christopher Columbus didn't discover America as a continent, and wasn't aslo the first European to visit American coasts: half a millennium before Columbus “discovered” America, Viking's feet may have been the first European ones to ever have touched North American soil. The expedition’s leader was Leif Eriksson (variations of his last name include Erickson, Ericson, Erikson, Ericsson and Eiriksson), son of Erik the Red, who founded the first European settlement of Greenland after being expelled from Iceland around A.D. 985 for killing a neighbor. (Erik the Red’s father, himself, had been banished from Norway for committing manslaughter.)

But Christopher Columbus was remarkably the first who came with the intention of a great military conquer.

- He didn't discover that the Earth is spherical: this knowledge was still accepted in the Middle Age and by the Christian doctrine.

Knowledge of the sphericity of the Earth survived into the medieval corpus of knowledge by direct transmission of the texts of Greek antiquity (Aristotle), and via authors such as Isidore of Seville and Beda Venerabilis.

Though the earliest written mention of a spherical Earth comes from ancient Greek sources, there is no account of how the sphericity of the Earth was discovered.

A recent study of medieval concepts of the sphericity of the Earth noted that since the eighth century, no cosmographer worthy of note has called into question the sphericity of the Earth.

Some examples are the papers of Pope Silvester II, who was awer of the knowledge of ancient greek philosophers and also of the researches of Muslim mathematicians. Also Saint Hildegard portrayed the Earth as a sphere in her Liber Divinorum Operum; Giovanni Sarabosco, an Italian astronomist wrote a paper (Tractatus de Spahaera) based on the knowledge of Ptolemy about the sphericity of the Earth; Honorius of Autun, a theologist very popular also in lay community,in his Elucidarium, a survey of Christian beliefs wrote about the sphericity of the Earth. His works was translated frequently into other languages.

Another proof that this knowledge was diffused also in the low folk and not only among the intellectuals of the Church, can be found in some of Berthold von Regensburg homelies in which he explained that the earth is spherical.

A practical demonstration of Earth's sphericity was achieved by Ferdinand Magellan and Juan Sebastián Elcano's expedition's circumnavigation (1519-1522).

- Christopher Columbus was the first European to have the idea to enslave native Americans and force them to work in colonizer's encomiendas. According to Cuneo, Columbus ordered 1,500 men and women seized, letting 400 go and condemning 500 to be sent to Spain, and another 600 to be enslaved by Spanish men remaining on the island. About 200 of the 500 sent to Spain died on the voyage, and were thrown by the Spanish into the Atlantic. (Bergreen, 196-197)

Those left behind were forced to search for gold in mines and work on plantations. Within 60 years after Columbus landed, only a few hundred of what may have been 250,000 Taino were left on their island.

- If you think that Christopher Columbus was loved and admired by people of his age, you are wrong: he gave land to the settlers and permitted the enslavement of the Taino people to work it. Complaints for his violence against Caribs and Taino Indians, but mostly for his cruelty against Spanish settler, trickled back to Spain, and eventually the monarchs sent a commissioner to investigate. Shocked by conditions at the colony, the commissioner arrested Columbus and his brothers and sent them back to Spain for trial. The brothers were released by the king and queen, but Columbus was removed from his position as governor of Hispaniola.

- Christopher Columbus was the fist European to commit a genocide: 56 years after Columbus's first voyage, only 500 out of 300,000 Indians remained on Hispaniola.

Population figures from 500 years ago are necessarily imprecise, but Bergreen estimates that there were about 300,000 inhabitants of Hispaniola in 1492. Between 1494 and 1496, 100,000 died, half due to mass suicide. In 1508, the population was down to 60,000. By 1548, it was estimated to be only 500.

Some important facts about slavery, Catholic Church and the famous Monarchs of Spain, Isabel of Castile and her husband Ferdinand of Aragon:

In 1492, Kingdom of Castile and Aragon had a disperate need of money: King Ferdinand and his wife Qeen Isabel used a lot of money in their wars against Portogual and their Conquer of the Emirate of Granada, that was an indipendente Muslim state at the age. They were deeply in debt, also with jews pawloaner, who at the age, were the only allowed to borrow money (Christian doctrine, by the way, didn't allow it), so they wrote the infamous Alhambra Decree with witch all jews were forced to left Spain and their properties passed in the Monarchs' hands.

I red some people associated the Dum Diversas with Columbus, but it has nothing to concern with "discovery" of the "new world": Dum Diversas is a papal bull issued on 18 June 1452 by Pope Nicholas V. It authorized Afonso V of Portugal to conquer Saracens and pagans and consign them to "perpetual servitude". It was referred to the muslim population of North Africa and also to the Turkish territories in Europe.

By the way, the Catholic Chruch condamed slavery in various occasion: in 1537 pope Paul III condemned "unjust" enslavement of non-Christians in Sublimus Dei. In 1686 the Holy Office limited the bull by decreeing that Africans enslaved by unjust wars should be freed. Eugene IV and Paul III did not hesitate to condemn the forced servitude of Blacks and Indians, in Sicut Dudum (1435) and in Sublimis Deus (1537). Their teaching was continued by Gregory XIV in 1591 and by Urban VIII in 1639. Except those formal condemn of slavery, the Church keep an ambiguous sentiment: the condamn was absolute, but most of the government of their age were built on slavery and keep allow their people to profit on slavery, for the reason that "indigenous" people were not Christians, they didn't have a soul, so they were like animals. The Holy See was unable to stop the trade, despite their good intentions.

The pontifical teaching was continued by the response of the Holy Office on March 20, 1686, under Innocent XI, and by the encyclical of Benedict XIV, Immensa Pastorum, on December 20, 1741. This work was followed by the efforts of Pius VII at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to have the victors over Napoleon outlaw slavery. The 1839 Constitution In Supremo by Gregory XVI continued the antislavery teaching of his predecessors, and was in the same manner not accepted by many of those bishops, priests and laity for whom it was written.

#us history#american history#history#christopher columbus#columbus day#indigenous peoples day#indigenous peoples of the americas#indigenous people's day: bay area led the change#indigenous people&039;s day#kingdom of spain#colonial history#colonialism#vavuskapakage#cancel culture#slavery#genocide#crimes against humanity#leif erickson day#leif erikson

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Looking to the Future of LGBTQ+ Identities in Eastern Europe and the Slavic Diaspora

Broadcast Jan. 9, 2021 - 58:12

SPEAKERS

Rebekah Robinson, Gala Mukomolova, Damir Imamović, Mateusz Świetlicki

[Into Music]

Rebekah Robinson: Hello, and welcome to the West Meeting Room. On today's episode, hosted by me, Rebekah, one of the producers here, you'll hear part of a conversation that I moderated titled, Looking to the Future of LGBTQ Identities in Eastern Europe and the Slavic Diaspora, which took place on Zoom on Monday, November 2, 2020, and organised by the Slavic Languages and Literatures Department here at the University of Toronto. I sat down with writer and poet Gala Mukomolova, Dr. Mateusz Świetlicki, and musician, Damir Imamović, to discuss the role of culture and activism in the community as they look toward the future. I would like to thank professors, Dragana Obradovic, Zdenko Mandušić, and Angieszka Jezyk, for putting together this conversation and inviting me to moderate. The bios for these accomplished speakers will be available in this episode’s show notes.

Rebekah: I've been really looking forward to this conversation over the past few weeks. And so, I'm hoping in order to get started, that each of you could briefly tell us about the context in which you're coming from, and the work that you do. And if the cultural context from which you're coming from influences your work in any sort of way. I know, we've mentioned that a little bit during your bios. I'd like to get into it a little bit more. And let's start with Gala on this one.

Gala Mukomolova: Okay, sure. Um, well, I am primarily a writer, and that's what I do. I write a lot of astrology things.

[chuckles]

And that is, I mean, I feel it's interesting already, just to think about like musicians and philosophers and rebels, and literature scholars as a point of conversation around world events. I think that I came to astrology writing sort of by circumstance. And I've mostly tried my best because it's very commercial and I work for a major syndicate to subtly or unsubtly move large masses that would otherwise be un-politicized by my like weekly astrology writings. And all my writing work that's more creative or personal, like the essays or the poems that I write, are very influenced by my upbringing, and I guess, just where I'm at, right. So I was raised, but, I mean, I was born in Moscow. My family's Jewish. We had to immigrate to Brooklyn, around the wave time that everybody else did. 1992 / 1993, I was raised very much in, in a kind of, like, understanding of difference as marker, right. So it's like the idea that who we are is always in relation to who we are not, or history. And I think that what I'm interested in, actually, in this discussion is, is learning more about people who are in place. Like I think I come from, my writing comes from being displaced. And, yeah, I don't know, I feel like there's so much, I mean, it's just who we are always influences what we make, right? I think that I also am very invested in a queer post-Soviet perspective, and that's really particular because I, I have an okay relationship with my family now, but I was disowned for many years and didn't speak to them. And the idea of being like, queer, or lesbian was antithetical to being Russian, to being Jewish -- Russian Jewish, because we're like, Well, you know, like, when you're, when you're a Jewish person from Moscow, but like, my family doesn't identify as Russian. They identify as Jewish. So it's like a particular thing to say, but, um, I think understanding the amount of disavowal that happens amongst like, how people come to define themselves. Like, with my family, being like, “Well, you know, if you're choosing this aspect of yourself, then you're not one of us, right?” But the “one of us” mentality has to come from a fear that you need to keep being like, non-Western. I'm just, like, kind of like creating this idea of devotion to the to the national idea. I don't know. So, which doesn't claim you, right, the national idea which doesn't claim you. So like, Russian people for so long, did not really claim Jewish people as one of their own. And yet, like to be clear, like Jewish Russia is to create a disavowal from the country that you come from, which we actually disavow to begin with.

Rebekah: Thank you so much, Gala, I think that's, I like the idea of, you know, or I find the ideas fascinating about being displaced within, like these different communities. You know, and I know you mentioned your work with astrology. And I'm hoping that you can about how these sort of intersections and ideas maybe even play into like contributing to your writing these astrological pieces. And as well as just know who we are is in relation to who we are not. Like, that's especially prevalent in today's politics throughout Eastern Europe and throughout the world, really. You know, everyone's trying to juxtapose themselves. And there's this fear of othering. So, I hope we can touch on that in this conversation as well. Let's move over to Damir, if you could introduce us, tell us a little bit about the work that you do. And if you find that your cultural context is influencing your work as well.

Damir Imamović: Thanks Rebekah. No, yeah, of course. I was born in 1978, during the time of Socialist Yugoslavia. And probably, mostly the kids at that time, end of 80s, I was what 10, 11, 12 when the war, when the dissolution of Yugoslavia started that I, 14, 13 and a half, something like that. So I somehow feel that most of us who are coming from that geographical area , we we carry this mark and this, most of our interests of that generation, or are of those generations are still colored by this, you know, traumatic event that happened in Yugoslavia. In the beginning, I started playing music during the war when Sarajevo was under the siege. I was in a shelter. And us kids, we were bored basically, so I had to do something. You know, you can't go out you can't do much. And some days, you cannot even go to your apartment upstairs. And I picked up a guitar and started learning songs. And, but actually, and of course, traditional music was always big around me in my family of traditional musicians. But I also, my first songs that I fell in love with were, you know, rock and roll, jazz. It was 90s. So, the whole Nirvana. But somehow in Bosnia, in Sarajevo, especially this sevdah traditional music, which was strongly rooted in Slavic oral culture, but also had a strong Turkish Ottoman Empire influence was always around, you know. So I just, I woke up as a 20 something year old and realized that I know all these songs. You know, in the day, I even use them not only as songs, I speak in that way sometimes. You know, they're some little pieces of those songs, some parts of it, I use it in everyday speech and it's so much a part of me. And then I realized only actually several years back that I was always interested, because this trauma really formed me. And my primary school class completely dissipated when the war started, you know, and suddenly, we became strangers. And that's why even today, I'm still probably quite close, closer to my friends from primary school, because I was in seventh grade when we started, then with later on high school, friends and university friends and other people. And I realized that without me knowing that all of my themes I was really interested in, you know, like, after high school, we have this system where we write at, like, a final paper in high school. Some kind of a diploma or something. And, of course, the University the same. And just when I look back, I realized that all of these things were actually connected to the same topic. And it is, how is it possible that people become strangers to one another, you know, when I, I never had the problem, intellectual or artistic with people being, you know, foreigners, people being unknown to one another. And you discover something that you don't know, but this very feeling that due to some act of politics, history, whatever, you become stranger. You become this foreign person, you know, and of course, coming out is a big part of that. Because it's, you know, the situation when you have some friends, you have family, and after coming out, and that's what a lot of LGBTQ people know, you suddenly become somebody else and you're still the same fucking person. But there's this estrangement, or whatever the word is in English, that happens, you know. So a lot of what I do is is kind of colored by that. Even without me knowing that I - That's actually one thing I'm rediscovering about what I do. But I have, you know, I always had diverse interests. I always loved literature, history, philosophy. Music was just a part of it. And after studying philosophy in Sarajevo, I had my ideas of pursuing a career as a philosopher means mostly sitting at one place and thinking, anyway. But I was lucky enough that I, just by chance, I was offered a gig as a musician, and I did it. And it was a big success. And I just felt that that's what I love doing, you know. And of course, later on, after that, I realized that I don't have to give up on my intellectual interest, you know. But I can still write, I can still, you know, research stuff and, and I realized that you have to, if you have an opportunity, you have to take over this place in mainstream society and speak with a different voice from there. You know, it's not, because mostly, I mean, the whole of Balkans, meaning former Yugoslavia, plus other countries in Eastern Europe, is actually today a place people are mostly forced to leave if they want to live their dreams, you know. And I remember this, this first Pride parade in Sarajevo last year at which I played. There was one moment when I literally wanted to cry. And that was when I saw all these guys and girls, queer couples of all kinds who are from Sarajevo, usually, both of them, you know, from a couple they were both from Sarajevo, but they've been living in, I don't know, all over the world for 15 plus years. And then they came back for that particular date was such a strong message, you know? So that's just for starters.

Rebekah: Absolutely. Thank you so much. I feel like you brought a lot of food for thought. e\Especially, I like the concept of how even within a specific region, you know, you become a stranger to one another through force of trauma, but also how that can also impact how LGBT people are also impacted as well. Especially when coming out from to their families or to their society, to their communities, on how you can even be ostracized and a kind of stranger in that way too. So, I hope we can explore that idea of being considered other and this estrangement that you mentioned later on in our conversation. How about you Mateusz?.

Mateusz Świetlicki: That's a difficult question. First of all, I want to say that I absolutely love my job. I love everything about it. It gives me satisfaction for a number of reasons. But before I say few things about these reasons, let me answer the question. Because your question was about, you know, the personal experience. I think that we cannot escape our personal experience at all. In order to, you know, succeed. You need to combine your personal experience. You need to stay, you know, truthful to your own self and your heritage and your identity. And, I was born in Poland. I lived in Poland when I was a child. I also lived in Germany. I also live in Louisiana, Shreveport, Louisiana. And I decided to stay in Poland. I decided to stay here because I do have hope. And I think that sharing my experience, sharing all of the things that I know. Sharing my you know, vision of the world, can actually help my students. And I absolutely do use my experience when it comes to my writing. When it comes to my teaching. When it comes to my writing, I have a degree in Slavic studies and Ukrainian studies and in American Studies. And I published a few things about Ukrainian literature, about Polish literature, about American literature. I try to write some things about gender, about men studies, about masculinity studies about queer things. I tried to find some queer themes in Ukrainian literature, but I always, I've always been interested in children's literature and YA literature and popular culture. I find this trash culture to be extremely inspiring. Now I'm working on a project on North American children's literature. By North American, I mean both American and Canadian. But, I'm writing about literature books written by Ukrainian and Polish authors. I mean, second, third, fourth generation Ukrainian / Polish authors. So books written in English, but books about the experience of being Polish, the experience of being Canadian, the experience of being Polish Canadian. The experience of being Ukrainian Canadian, experience of being Ukrainian, in Canada, and so on. So I think I'm trying to somehow combine my expertise. Like, I think this is the perfect topic for me, because I'm using everything of my knowledge. So I can use my Slavic studies, background, and my English studies, American Studies, background. And every single time when I want to write about, let's say, memory. When I want to write about something else, I always end up thinking about queerness, I always end up thinking about the ways in which sexuality or gender are, you know, constructed in the literature or film. And I think it is connected to my identity, you know. This topic, I cannot escape this topic, you know. I absolutely cannot escape this gender theme, and it's difficult to do that in Poland. And when it comes to the last few years, when you hear your president saying that LGBT is not people, LGBT is ideology. When you hear politicians saying that we have to make sure that gender ideology and the so called LGBTQ ideology doesn't destroy our children. And there's always the child to use as this political, you know, tool. It's, on the one hand, it's challenging to write about such topics. But on the other hand, I find it so fascinating and stimulating, intellectually stimulating. And I think that we should resist. And this leads me to what I said at the beginning of my little speech. My students, teaching is fascinating, really, and inspiring. And my students are absolutely brilliant. I am so privileged to be teaching a number of really intelligent, clever young people who are sick and tired of this situation. Who grew up in Poland, with the internet around them, who grew up traveling, you know, going on vacation to various different places. And there are queer individuals who want to live in Poland, and who want to, and who are proud or openly gay, or lesbian or transgender, and they don't care. And they don't want to move to America or to Canada or to Germany. They want to stay here and they want to make a change. And what I hear my students tell me that my classes made them want to fight. I'm shocked because I always think that my classes are ideologically neutral. So I always think that I'm not really that political in class. But it turns out that while I'm not trying to be political, I am political. So yesterday, my wonderful graduate student told me that during one of like, random classes, like ethics of academic work, stuff like that - I taught them about the phenomenon of angry white men in America, like Trump supporters. And someone, and I didn't remember that, I just used some basic examples of books, and I, and I asked them to come up with a list of Works Cited. And then she told me that because of this little class, the entire group, read that book. And that's why I find my job to be really, my profession to be really inspiring, because I can teach. I can write and my students really inspire me. So I, every single class influences my writing.

Rebekah: We'll tease that out, for sure. I really enjoyed this idea of Polish people who want to remain in Poland because that's like their home, you know. And just trying to make it a place. I think that's going to be one of the ending questions, you know, what are their hopes for the future? How can people you know, move to this place where they can build a society and build an area where they can be completely themselves. And so I want to hold on to that idea and bring that up a little bit later. Thank you. Gala, I wanted to go back a little bit to talk about your astrology workings. And I want to see how might your traditional Slavic values, maybe that you have been surrounded with ongoing in your life, how you maybe incorporate them a little bit into your writing astrology? Or how even being part of a diaspora community, how that might influence your work when writing about astrology?